Abstract

We recently demonstrated a critical role for two-pore channel type 2 (TPC2)-mediated Ca2+ release during the differentiation of slow (skeletal) muscle cells (SMC) in intact zebrafish embryos, via the introduction of a translational-blocking morpholino antisense oligonucleotide (MO). Here, we extend our study and demonstrate that knockdown of TPC2 with a non-overlapping splice-blocking MO, knockout of TPC2 (via the generation of a tpcn2dhkz1a mutant line of zebrafish using CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing), or the pharmacological inhibition of TPC2 action with bafilomycin A1 or trans-ned-19, also lead to a significant attenuation of SMC differentiation, characterized by a disruption of SMC myofibrillogenesis and gross morphological changes in the trunk musculature. When the morphants were injected with tpcn2-mRNA or were treated with IP3/BM or caffeine (agonists of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (IP3R) and ryanodine receptor (RyR), respectively), many aspects of myofibrillogenesis and myotomal patterning (and in the case of the pharmacological treatments, the Ca2+ signals generated in the SMCs), were rescued. STED super-resolution microscopy revealed a close physical relationship between clusters of RyR in the terminal cisternae of the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), and TPC2 in lysosomes, with a mean estimated separation of ~52–87 nm. Our data therefore add to the increasing body of evidence, which indicate that localized Ca2+ release via TPC2 might trigger the generation of more global Ca2+ release from the SR via Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release.

Keywords: Two-pore channel 2, Slow skeletal muscle cell differentiation, Myofibrillogenesis, Zebrafish, Morpholino oligonucleotides, CRISPR/Cas9, STED super-resolution microscopy, Ca2+ signaling

1. Introduction

There is a growing interest in the role played by two-pore channels (TPCs) and their link with nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide diphosphate (NAADP) signaling with regards to their combinatorial contribution to the Ca2+-mediated regulation of differentiation and development (Calcraft et al., 2009; Patel et al., 2010; Galione, 2011; Morgan and Galione, 2014; Parrington and Tunn, 2014; Parrington et al., 2015; Brailoiu and Brailoiu, 2016). The various roles played by the Ca2+ mobilizing messengers inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) and cyclic adenosine diphosphate ribose (cADPR), and their respective receptors in the endoplasmic/sarcoplasmic reticulum (ER/SR) membrane, are well established (Berridge, 1993; Lee, 1993; Berridge et al., 2003; Mikoshiba, 2007; Lanner et al., 2010). However, the discovery of a third Ca2+ mobilizing messenger, NAADP, which releases Ca2+ from alternative Ca2+ stores, acidic endosomes and lysosomes, via TPCs (Patel, 2004; Yamasaki et al., 2005; Lee, 2005), has resulted in new challenges to our current understanding of the complexity of Ca2+-mediated signaling pathways during differentiation and development.

TPCs are members of the superfamily of voltage-gated ion channels, and they have been reported in many cell types and in a wide range of circumstances to act as an endogenous NAADP receptor (Calcraft et al., 2009; Zong et al., 2009; Brailoiu et al., 2010; Morgan and Galione, 2014). Three isoforms of TPCs are present in most vertebrates, i.e., TPC1 to 3. TPC1 and TPC3 are suggested to localize to the endosomes and other compartments along the endo-lysosomal system; whereas TPC2 is specifically expressed in the membrane of late endosomes and lysosomes (Ruas et al., 2014). It has been suggested that in some cases TPCs are NAADP-insensitive; instead they are activated by the lipid phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate (PI(3,5)P2), and they conduct Na+ rather than Ca2+ (Wang et al., 2012; Cang et al., 2013). However, recent reports have confirmed that NAADP does indeed bind to TPCs, perhaps via accessary proteins (Lin-Moshier et al., 2012; Walseth et al., 2012a, 2012b; Morgan and Galione, 2014), and that they are able to mediate Ca2+ release from acidic organelles (Jha et al., 2014; Jentsch et al., 2015; Ruas et al., 2015; Pitt et al., 2016). An intriguing property of TPCs is that in addition to NAADP, their activity might also be mediated by other regulators, such as PI(3,5)P2, Mg2+, P38 and JNK (Jha et al., 2014). They might, therefore, represent a form of signaling hub with some additional properties and functions that are still to be identified.

It has been shown that TPCs are important mediators of differentiation and function of a variety of cell types during early development. These include neurons (Brailoiu et al., 2005, 2006), skeletal muscle cells (Aley et al., 2010; Kelu et al., 2015), smooth muscle cells (Kinnear et al., 2008; Pereira et al., 2014), cardiac muscle cells (Collins et al., 2011; Capel et al., 2015), osteoclasts (Sun et al., 2003; Notomi et al., 2012), hematopoietic cells (Orciani et al., 2008), keratinocytes (Park et al., 2015), and embryonic stem cells (Zhang et al., 2013; Hao et al., 2016). In addition, for several decades, investigators have reported the essential role played by Ca2+ signaling during the embryonic development of skeletal muscle from a number of systems (for reviews see Webb and Miller (2011), Tu et al. (2016)). These include chick (David et al., 1981); frog (Ferrari et al., 1996, 1998; Ferrari and Spitzer, 1999); mouse (Lorenzon et al., 1997; Pisaniello et al., 2003); and zebrafish (Brennan et al., 2005; Cheung et al., 2011). These studies focused on the role played by extracellular Ca2+ as well as that of the then known intracellular Ca2+ mobilizing messengers, IP3 and cADPR. More recently, however, the discovery of TPCs has led to a surge in interest of NAADP-mediated Ca2+ release from acidic vesicles, and how this integrates with the other Ca2+ mobilizing agents to initiate and mediate a variety of signaling pathways. Several recent reports from both in vivo (Kelu et al., 2015) and in vitro (Aley et al., 2010) studies have indicated that TPCs play a necessary role in the differentiation and function of skeletal muscle.

Here, we report the combined use of gene knockdown, gene knockout, and pharmacology to explore the function of TPC2 during the differentiation of non-muscle pioneer slow skeletal muscle cells during zebrafish development (Devoto et al., 1996; Du et al., 1997). Morpholino (MO) antisense oligonucleotide technology has been the main reverse genetic approach to study gene function in zebrafish for the past decade (see review by Blum et al. (2015)). MOs can work either by blocking the translation or splicing of the mature transcript and pre-mRNA, respectively, and thus are able to attenuate the expression of specific genes. Furthermore, following the recent advancement in genome-editing technologies, gene function can now be studied in vivo in the context of gene-knockout using clustered regulatory interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR)/Cas9 endonuclease. CRISPR/Cas9 is currently considered to be the most cost-effective and efficient genome-editing method, and it has been successfully applied to zebrafish for the generation of a number of loss-of-function mutants (Chang et al., 2013; Hwang et al., 2013; Jao et al., 2013; Irion et al., 2014; Varshney et al., 2015). By combining the transient-knockdown approach using MOs and the persistent-knockout approach using CRISPR/Cas9, we present in vivo evidence that TPC2-mediated Ca2+ release from lysosomes plays a key role in non-muscle pioneer slow muscle cell (SMC) differentiation, myofibrillogenesis and myotomal patterning in developing zebrafish embryos.

Specifically, here we report, via whole-mount immunohistochemistry and fluorescent-labeling, the disruption of the structure and organization of two of the main non-muscle pioneer SMC proteins (i.e., myosin heavy chain and F-actin), as well as a decrease in the number of prox1+ SMC nuclei following inhibition of TPC2 by MO-based knockdown and CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout of TPC2. Moreover, a partial rescue of the normal phenotype was obtained via the co-injection of a mutant tpcn2 mRNA that is not recognized by the translation blocking TPCN2-MO-T. Furthermore, a complementary pharmacological approach with bafilomycin A1 and trans-ned-19, which deplete the lysosome acidic Ca2+ stores and antagonize TPCs, respectively, also phenocopied the TPC2 morphants and mutants. To test the hypothesis that TPC2 triggers the release of additional Ca2+ from the ER/SR by activating IP3Rs and/or RyRs, we treated the TPC2 morphants with either IP3/BM or caffeine, and then investigated the effect on the development of the TPC2-depleted myotome by up-regulating Ca2+ release from the ER/SR. These rescue results following TPC2-knockdown suggest that the release of Ca2+ from IP3Rs has a more profound role with regards to regulating the morphology of the non-muscle pioneer SMC than does release from RyRs.

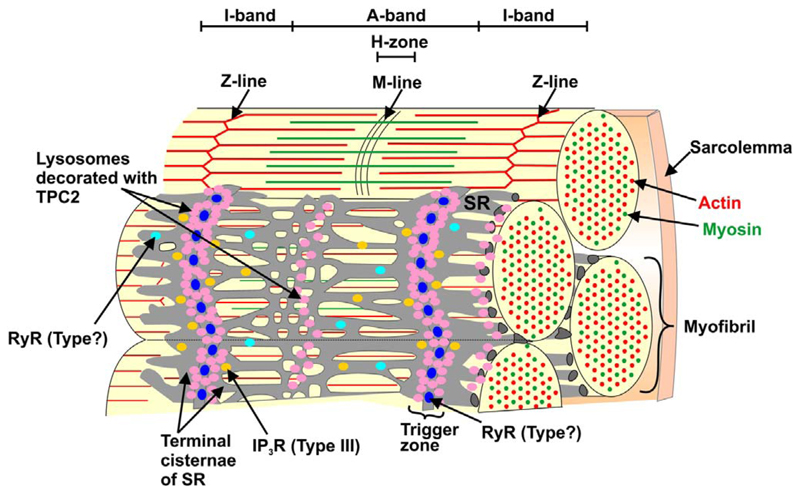

Furthermore, using dual-colour STED super-resolution microscopy, we were able to resolve and hence report the presence of ~52–87 nm ‘gaps’ between clusters of fluorescently-labeled RyRs and TPC2 in mature myofibers prepared from the trunk muscles of ~48 hpf embryos. These RyR-TPC2 clusters were located (in a striated pattern) in the terminal cisternae of the SR, adjacent to the sarcomeric I-bands. Taken together, our new data suggest that in the differentiated non-muscle pioneer SMCs of zebrafish, TPC2 in the lysosomal membrane forms an intimate relationship with RyRs in the SR membrane. It has been proposed that TPC-RyR clusters act as “trigger zones” where TPCs are stimulated to release highly localized elementary Ca2+ signals that subsequently lead to the opening of RyR in the SR/ER membrane resulting in global signals via Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR; Kinnear et al., 2004, 2008; Galione, 2011). We suggest, therefore, that Ca2+ release via TPC2 plays an essential role during excitation-contraction (EC)-coupling in mature non-muscle pioneer SMC, as well as an earlier necessary role in excitation-transcription (ET)-coupling during non-muscle pioneer SMC differentiation (Kelu et al., 2015).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Zebrafish husbandry and embryo collection

Wild-type zebrafish (Danio rerio; AB and ABTU strains), the α-actin-apoaequorin-IRES-EGFP (α-actin-aeq) transgenic line (AB background; Cheung et al., 2011), and the mutant line tpcn2dhkz1a (ABTU background) were maintained, and their fertilized eggs collected, as previously described (Webb et al., 1997; Cheung et al., 2011). The AB strain was obtained from the Zebrafish International Resource Center (University of Oregon, Eugene, OR, USA), and the ABTU strain was a generous gift from Prof. Han Wang (Soochow University, Suzhou, China). Fertilized eggs were maintained at ~28°C for most experiments, but sometimes they were kept at room temperature (i.e., ~23°C), to slow development until the desired stage was reached.

2.2. Design and injection of morpholino oligomers

All the morpholino oligomers (MOs; synthesized by Gene Tools LLC, Philomath, OR, USA) were prepared at a 1 mM stock concentration in Milli-Q water and kept at room temperature. The expression of TPC2 was attenuated using the translation-blocking MO described previously (Kelu et al., 2015; TPCN2-MO-T) as well as a splice-blocking MO (TPCN2-MO-S). As some MOs are known to induce p53 activity and thus result in non-specific apoptosis (Robu et al., 2007), TPCN2-MO-T and -MO-S were co-injected with a previously characterized p53-MO (Robu et al., 2007; Kelu et al., 2015) at a ratio of ~1:1.5. The p53-MO (injected alone) and a standard control-MO were also used as specificity controls. Thus, ~1.5 nL of the diluted TPCN2-MO-T (~2.5 ng), or ~3 nL of the TPCN2-MO-S (~5 ng), the standard control-MO (~5 ng) or p53-MO (~7.5 ng) were injected into the yolk of embryos at the 1- to 4-cell stage and subsequently carried into the blastodisc/blastoderm by ooplasmic streaming (Leung et al., 1998). Embryos were microinjected using equipment and methods described by Webb and Miller (2013). In some experiments, sub-optimal doses of TPCN2-MO-T (i.e., ~1.3 ng) and TPCN2-MO-S (i.e., ~2.5 ng), both mixed with p53-MO at a 1:1.5 ratio, were individually injected into the yolk of embryos to further validate the specificity of the TPCN2-MOs. The sequences for the TPCN2-, p53- and standard control-MOs used, are as follows:

TPCN2(ATG)-MO-T: 5’-CAGCCAGCAGCGGTTCTTCTTCCAT-3’

TPCN2(Splice)-MO-S: 5’- TGATTGTGTTTTTACCTTAATCGCA-3’

p53(ATG)-MO: 5’-GCGCCATTGCTTTGCAAGAATTG-3’

Standard control-MO: 5’-CCTCTTACCTCAGTTACAATTTATA-3’

2.3. Design, cloning and injection of the mRNA rescue construct

The tpcn2 mRNA rescue construct was designed, cloned and injected into embryos as previously described (Kelu et al., 2015).

2.4. Total RNA isolation and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from a batch of ~25 to 50 dechorionated embryos at 24 hpf using TRIzol reagent (Ambion, Invitrogen Corp.) according to the manufacturer's instructions, after which it was either kept at –80°C or directly subjected to RT-PCR. For the latter, cDNA was synthesized using the random primers and reagents provided in a High-capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA), and according to the manufacturer's instructions. Two loci of the tpcn2 gene, and one locus of the β-actin house-keeping gene, were amplified from the cDNA via PCR. The PCR amplification procedure consisted of a 2-min denaturing step at 95°C, followed by 25–30 cycles of: 1) 30-s denaturation at 95°C; 2) 30-s annealing at 60°C; and 3) 30–45-s elongation at 72°C. The amplicons were maintained at 4°C after a final 5-min extension step at 72°C, after which they were analyzed via 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. The relative band intensity on the gels was determined using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, USA).

The primers used were as follows:

-

tpcn2 RT-PCR forward primer (F): 5’-ATGGAAGAAGAACCGCTGCTG-3’

tpcn2 RT-PCR reverse primer # 1 (R1): 5’-CCCCACTGACATAAGTTGGAGT-3’

tpcn2 RT-PCR reverse primer # 2 (R2): 5’-TCGATGAATACTACTGCCTGCT-3’

tpcn2 RT-PCR reverse primer # 3 (R3): 5’-TGCTATCTCGGGAAGGGTCC-3’

β-actin RT-PCR forward primer: 5’-TGGTATTGTGATGGACTCTGG-3’

β-actin RT-PCR reverse primer: 5’-AGCACTGTGTTGGCATACAGG-3’

2.5. CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing - design of the tpcn2 guide RNA (gRNA)

A 23-base pair (bp) tpcn2 guide RNA (gRNA) target sequence that targets exon 9 of tpcn2, (i.e., which encodes part of the first homologous domain of the ion transporting six-transmembrane-segments of TPC2; Zhu et al., 2010) was chosen using CRISPRdirect (a web server for selecting rational CRISPR/Cas9 targets; http://crispr.dbcls.jp/; Naito et al., 2015). The target sequence selected was:

5’-GGACCCTTCCCGAGATAGCAAGG-3’

This was chosen because: 1) A nucleotide BLAST of the seed sequence (i.e., a 12 bp sequence located 5’ of the protospacer adjacent motif [PAM]; Jinek et al., 2012; Cong et al., 2013) indicated that there would be no potential off-targeting effects; and 2) it contains a CCCGAG restriction site (underlined in the previous sequence), which can be cleaved by the restriction enzyme, AvaI (New England Biolabs Inc.), for the evaluation of mutation efficiency.

2.6. Preparation and injection of tpcn2 gRNA and Cas9 mRNA

2.6.1. tpcn2 gRNA

The gRNA scaffold vector was kindly provided by Prof. Han Wang. The linear DNA template for in vitro transcription of tpcn2 gRNA was obtained via PCR using the following short oligonucleotides as primers:

Forward primer:5’-GATCACTAATACGACTCACTATAGGACCCTTCCCGA GATAGCAGTTTTAGAGCTAGAAA-3’

Reverse primer: 5’-AAAAGCACCGACTCGGTGCC-3’

In the forward primer, the T7 site is in bold, the 20 bp tpcn2 gRNA target sequence (excluding the PAM) is underlined, and the 5’ portion of the gRNA scaffold is in italics. The tpcn2 gRNA was synthesized via in vitro transcription using the mMESSAGE mMACHINE T7 transcription kit described previously, and purified using phenol/chloroform extraction (Westerfield, 2000).

2.6.2. Cas9 mRNA

The pT3TS plasmid vector, which contains a zebrafish codon-optimized version of Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 and an SV40 large T-antigen nuclear localization signal (nls) at both the 5’ and 3’ end (hereafter referred to as nls-zCas9-nls; Jao et al., 2013), was also obtained from Prof. Han Wang. The nls-zCas9-nls mRNA was linearized with Xbal, after which it was in vitro transcribed using a mMESSAGE mMACHINE T3 transcription kit (Ambion, Invitrogen Corp.) and then purified using phenol/chloroform extraction.

The tpcn2 gRNA and nls-zCas9-nls mRNA were diluted to ~1000 ng/μL and ~800 ng/μL, respectively, in Milli Q containing DEPC and 0.5% phenol red (to help visualize the injectate), and kept at −80°C. A mixture of the gRNA and mRNA was co-injected (to give a total volume of ~1 nL) into the blastodisc of 1-cell stage embryos using 25 ng/μL, 50 ng/μL or 100 ng/μL tpcn2 gRNA, and 150 ng/μL nls-zCas9-nls mRNA (Chang et al., 2013; Hwang et al., 2013; Jao et al., 2013; Irion et al., 2014).

2.7. Evaluation of mutation efficiency by the restriction endonuclease digestion assay

Genomic DNA was extracted from zebrafish embryos and adults using a modified “HotSHOT” method (Meeker et al., 2007). Complete embryos (n=5) were randomly selected from each cross and sacrificed at 24 hpf, whereas a small region of the caudal fin was excised from adult zebrafish after anesthetization in ~0.02% MS-222 (Nüsslein-Volhard and Dahm, 2002). The target region was then amplified via PCR using a pair of primers designed to flank this region, and using protocols described earlier. The primers used are as follows:

-

Forward primer: 5’-GAGAGGCAGGATTGACTCAACAG-3’

Reverse primer: 5’-TGTACAATATCAGACTGTGGCAGC-3’

The amplicons were purified using a PCR-M Clean Up System (Viogene BioTek Corp., Taipei, Taiwan), after which AvaI digestion was performed at 37°C for 3 h. The mutation efficiency was assessed via 2% agarose gel electrophoresis, and the DNA band intensity was quantified using ImageJ.

2.8. Genotyping of tpcn2 mutants

The tpcn2 mutants were genotyped either by Sanger sequencing or 3% agarose gel electrophoresis. Prior to sequencing, the tpcn2 target region of mutant embryos and fish was amplified via PCR as described earlier. Amplicons of the F0 embryos, which contained mosaic mutations in the tpcn2 target region, were first cloned into a pCR™4-TOPO® TA vector using a TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen Corp.), and then 10 individual clones were randomly selected after transformation and sequenced by GENEWIZ (Suzhou, China). Amplicons of subsequent generations of the tpcn2 mutant were sequenced by BGI Shenzhen (Shenzhen, China). For gel electrophoresis, amplicons of the tpcn2 mutant were obtained and then separated on 3% agarose gels, such that heterozygotes and homozygotes resulted in two bands and a smaller-sized single band, respectively, when compared with the wild-type controls.

2.9. Pharmacological treatments

Stock solutions of bafilomycin A1 (500 μM; Calbiochem, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) and trans-ned-19 (20 mM or 50 mM; Enzo Life Sciences, Inc., Farmingdale, NY, USA) were prepared as described previously (Kelu et al., 2015). Dechorionated embryos were then incubated at ~28°C with 100 nM, 500 nM, or 5 μM bafilomycin A1, or with 50 μM, 100 μM or 500 μM trans-ned-19 (both diluted in Danieau's solution) using methods described previously (Kelu et al., 2015).

The trans-ned-19 working solutions were sometimes heated to 65°C for 5 min to prevent precipitation; this occasionally happened when the drug came in contact with the aqueous Danieau's solution. After heating, trans-ned-19 was cooled to ~28°C before it was applied to the embryos.

IP3/BM (rac-myo-inositol, 1,4,5-trisphosphate hexakis(butyrloxymethyl) ester; Sinova Inc., Bethesda, MD, USA), is a membrane-permeant form of the IP3R agonist, IP3 (Li et al., 1997), and caffeine is a well-known RyR agonist (Rousseau et al., 1988). Stock solutions of IP3/BM (10 mM) and caffeine (10 mM) were prepared in DMSO and Danieau's solution, respectively, and then stored at −20°C and room temperature, respectively. Dechorionated embryos were incubated in working solutions of 100 μM IP3/BM or either 0.5 mM or 2 mM caffeine (both diluted in Danieau's solution), from ~17 hpf to ~24 hpf, at ~28°C.

In all of the pharmacological treatments, the terminal tail-bud of embryos was excised just prior to the start of the treatment (using methods described by Kelu et al., 2015), to facilitate diffusion of the drugs up the trunk and into the muscle precursor tissues of the later-stage embryos (i.e., at ~17 hpf; Liu and Westerfield, 1990). Control groups were prepared in parallel by incubating tail-bud-excised embryos for the same period of time in Danieau's solution containing 1−2.5% DMSO alone (for the bafilomycin A1, trans-ned-19 and IP3/BM treatments), or in Danieau's solution alone (for the caffeine treatment).

2.10. Whole-mount immunohistochemistry and immunocytochemistry

Embryos at 24 hpf were dechorionated, anesthetized and then fixed either overnight at 4°C or for 4–6 h at room temperature, as described by Kelu et al. (2015). The paraformaldehyde used for fixation was prewarmed to room temperature in order to minimize the risk of temperature shocking the embryos. Embryos were then labeled using well-established techniques (Cheung et al., 2011), with: 1) the F59 mouse anti-myosin heavy chain antibody (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa, USA; at a 1:10 dilution); 2) a rabbit anti-prox1 antibody (AngioBio, San Diego, CA, USA; at a 1:500 dilution); or 3) the 2137A rabbit anti-TPC2 antibody (used at 1:10; Kelu et al., 2015). The F59 and anti-prox1 primary antibodies label the SMCs and SMC nuclei, respectively (Devoto et al., 1996; Roy et al., 2001), at this stage of development. The subsequent secondary antibody incubations were conducted using the Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) antibodies (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen Corp., Thermo Fisher Scientific; used at 1:200), for 3 h at room temperature in the dark. Embryos were then incubated with Alexa Fluor 568-tagged phalloidin (Molecular Probes Inc.; used at 1:50) for 3 h at room temperature in the dark to visualize F-actin. Prior to confocal microscopy, labeled embryos were mounted either in grooves made in 1% agarose inside imaging chambers using phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Cheung et al., 2011) containing 3% methylcellulose, or under AF1 mountant (Citifluor Ltd., Leicester, UK) on microscope slides with the yolk and head excised.

For immunocytochemistry, a protocol modified from Horstick et al. (2013) was adopted to prepare primary cell cultures from the trunk musculature of zebrafish embryos. In this modified protocol, embryos were dechorionated at 48 hpf, after which they were incubated in PBS containing 2 mg/μL collagenase Type IA (Sigma-Aldrich Corp.) for 2 h at room temperature with shaking. To facilitate cell dissociation further, embryos were triturated every 30 min. The dissociated cells in suspension were then centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 min and the supernatant was discarded. Residual collagenase was removed by resuspending the pellet in PBS, followed by centrifugation (again at 1000 rpm for 5 min), and the supernatant was discarded. The cells were then resuspended in PBS before being plated onto laminin-coated glass coverslips (13 mm diameter; No. 1.5H; Paul Marienfeld GmbH & Co. KG) for 1 h (Andersen, 2001), after which they were fixed as described by Kelu et al. (2015). The fixed cells were immunolabelled using methods and antibodies, (i.e., the 2137A anti-TPC2, anti-inositol trisphosphate receptor (type III), and 34 C anti-ryanodine receptor primary antibodies, and either Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) or Atto 647N goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies), described previously (Kelu et al., 2015), and then mounted on microscope slides with ProLong Gold antifade reagent (without DAPI; Molecular Probes Inc).

2.11. In vivo reconstitution of aequorin and bioluminescence detection

An f-coelenterazine stock solution of 10 mM (NanoLight Technologies, Pinetop, AZ, USA) was prepared as described previously (Kelu et al., 2015). Active aequorin was then reconstituted in vivo, by incubating α-actin-aeq transgenic embryos (with their chorions intact) from the 4- to 64-cell stage (i.e., 1 hpf to 2 hpf) to the ~16-somite stage (i.e., ~17 hpf) with 50 μM f-coelenterazine (Kelu et al., 2015). Embryos were then washed and dechorionated, before being transferred to individual custom-designed imaging chambers (Webb and Miller, 2013; Kelu et al., 2015). The volume of each chamber was reduced to minimize the amount of bathing solution required during the embryo incubations. This was achieved by applying a thick ring of wax, consisting of a 1:1:1 ratio of beeswax, paraffin (both from Candlewhat, UK), and Vaseline (Chesebrough-Pond's Corp., Greenwich, CT, USA), to the outer, plastic-base of the chamber. Embryos were then transferred to the custom-built photomultiplier tube (PMT)-based luminescence detection systems (Science Wares, Inc., East Falmouth, MA, USA; Webb et al., 2010) for luminescence detection. Following data collection, embryos were lysed with 1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich Corp.) to “burn-out” residual aequorin (Cheung et al., 2011). Numerical data were reviewed using the PMT-IR Imager 2.1 Review software (Science Wares, Inc).

2.12. Phenotypic and motor behavior studies of zebrafish embryos using bright-field and video microscopy

The degree of tail straightening, spontaneous coiling and touch-evoked response of embryos following MO-based knockdown (without and with mRNA rescue) and CRISPR/Cas9-knockout of TPC2 were quantified via bright-field and video microscopy (see Supplementary Materials and Methods).

2.13. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) Assay

Embryos were fixed, as previously described (Kelu et al., 2015). An In situ Cell Death Detection Kit, TMR Red (Roche Applied Science) was then utilized according to the manufacturer's instructions to detect DNA fragmentation due to cell death within embryos. Some embryos were used as TUNEL positive and negative controls; in the former, embryos were treated with DNase I at 10 unit/mL for 10 min at room temperature prior to labeling procedures; whereas in the latter, the terminal transferase that catalyzes the incorporation of labeled nucleotides to the 3’ end of DNA was omitted from the labeling solution. Prior to fluorescence microscopy, labeled embryos were mounted in grooves made in 1% agarose inside imaging chambers using PBS containing 3% methylcellulose.

A rectangular region of interest (ROI) of 250 μm×125 μm was placed in the middle of the trunk (i.e., starting at the anterior end of the yolk extension) of each embryo. Quantification of the fluorescence intensity within each ROI was then performed using ImageJ.

2.14. Imaging the fluorescently-labeled embryos

Epi-fluorescence microscopy was conducted using a Nikon DS-5Mc CCD camera mounted on a Nikon AZ100 microscope with an AZ Plan Apo 1× lens as previously described (Chan et al., 2015). Red fluorescence from the TUNEL assay was acquired using 510–560 nm excitation (using a Nikon Intensilight C-HGFI Epi-fluorescence Illuminator) and BA 590 nm emission. Confocal microscopy was conducted using either a Nikon C1 laser scanning confocal system mounted on a Nikon Eclipse 90i microscope, or a Leica TCS SP5 II laser scanning confocal system mounted on a Leica DMI 6000 inverted microscope using lenses, lasers and the green and red fluorescence excitation/emission settings described previously (Cheung et al., 2011; Kelu et al., 2015; Chan et al., 2015). The confocal z-stacks of images acquired were then reconstructed using ImageJ, and various parameters of the myotome of embryos were measured manually using the same software.

2.15. Stimulated emission depletion (STED) super-resolution imaging of immunolabelled primary cultured cells

To perform dual-colour STED imaging, the immunolabelled primary cell cultures that were mounted on microscope slides were kept in a light-tight box and sent to Leica Microsystems Trading Ltd. (Shanghai, China), where the super-resolution imaging was kindly performed by the Leica technical team, using a Leica TCS SP8 STED 3X confocal laser scanning microscope system.

Using the dual-colour STED images, the areas of the I-band clusters, as well as the areas and Feret's diameters of the gaps inside the clusters were measured using ImageJ. Images were first subjected to auto-thresholding, and then the boundaries of the clusters and gaps were auto-traced, after which the measurements were conducted automatically by the software. The x,y-resolution of the 488 channel (showing the RyR-labeled clusters) was also determined with ImageJ by conducting line-scans across the brightest pixel(s) within a cluster, after which a fluorescence intensity profile was generated and then a Gaussian curve fitting was performed. The full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) of the Gaussian curve was determined from the sigma, σ, which is the standard deviation of the Gaussian functions, using the formula: (Weisstein, 2015).

2.16. Statistical analysis

Numerical data were exported to Microsoft Office Professional Plus Excel 2013 for basic descriptive statistics and graph plotting, and to Minitab 17.3.1 (Minitab Inc., State College, PA, USA) for statistical analysis using one-way ANOVA and the subsequent post hoc analysis using Tukey's Method (McDonald, 2014). P-values < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. CorelDRAW X7 (Corel Corp., Ottawa, ON, Canada) was used for figure preparation.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of MO-based knockdown and mRNA rescue of TPC2 on the development of SMCs

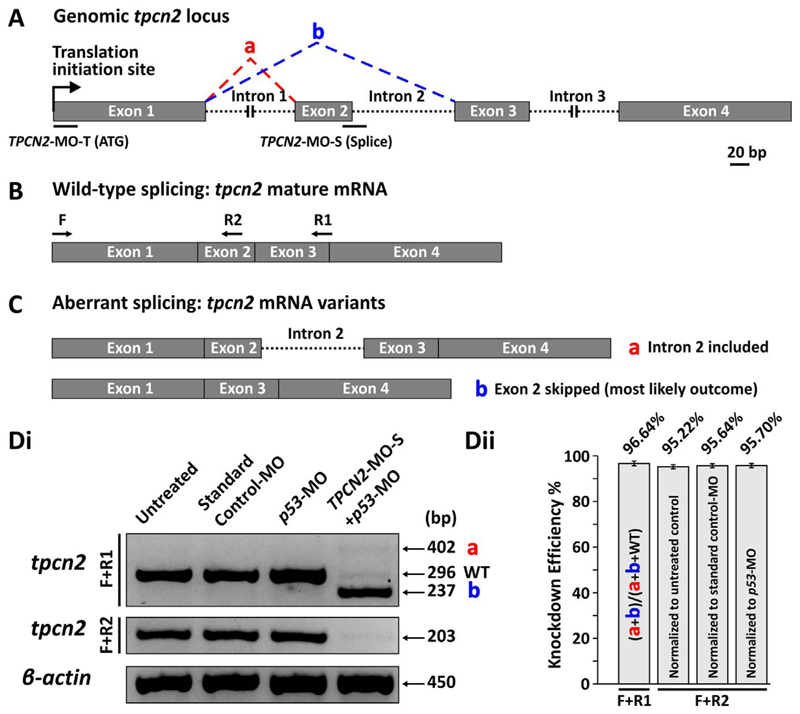

The function of TPC2 during SMC differentiation was initially investigated by knocking down TPC2 expression using antisense MO technology. We previously injected a translation blocking TPCN2-MO (TPCN2-MO-T) into a transgenic line of zebrafish that expresses apoaequorin specifically in the skeletal muscle, and demonstrated a dramatic attenuation of the normal Ca2+ signals generated by the SMCs starting at ~17.5 hpf (Kelu et al., 2015). In this new study, we designed another MO (TPCN2-MO-S), this time that targeted the tpcn2 pre-mRNA. This type of MO interferes with normal splicing, and so it commonly results in the exclusion of exon(s) in the mature mRNA thereby inhibiting the expression of the wild-type transcript (Morcos, 2007), in this case tpcn2 (Fig. 1A). To evaluate the knockdown efficacy of the TPCN2-MO-S, primers were designed to flank exons 1–3 (i.e., using the F and R1 primers described in the Materials and Methods), or exons 1–2 (i.e., using the F and R2 primers; Fig. 1B). Using the F+R1 primer set, two aberrantly spliced tpcn2 mRNA transcripts were detected via gel electrophoresis in the TPCN2-MO-S-injected embryos (Fig. 1C,1Di), whereas with the F+R2 primer set, severe downregulation in the expression of wild-type tpcn2 mRNA was observed in the morphants, suggesting the exclusion of exon 2 (Fig. 1Di). To quantify the knockdown efficiency, the band intensity after gel electrophoresis was evaluated, and showed a ~95–97% decrease in the expression of the wild-type tpcn2 transcript (n=3; Fig. 1Dii) when TPCN2-MO-S was injected at ~5 ng. As TPCN2-MO-S appears to be highly effective and efficient at knocking down TPC2, it was therefore used in parallel with TPCN2-MO-T in the subsequent experiments. Moreover, the simultaneous application of the two non-overlapping MOs (i.e., TPCN2-MO-T and TPCN2-MO-S) at doses below threshold was also performed to confirm the specificity of these MOs.

Fig. 1.

Schematics to show the design of TPCN2-MO-T and TPCN2-MO-S, and determination of the specificity of TPCN2-MO-S using RT-PCR. (A) The genomic locus of tpcn2 of zebrafish, showing exons 1–4, introns 1–3, and the target sequences for TPCN2-MO-T and TPCN2-MO-S. The red and blue dashed lines indicate two potential splicing outcomes that might result from the splice-blocking action of TPCN2-MO-S, when compared with the wild-type (WT) transcript. (B) The wild-type tpcn2 mRNA transcript (with exons 1–4 alone) showing the design of one forward (F) and two reverse (R1 and R2) primers for performing RT-PCR. (C) Two possible aberrant tpcn2 mRNA transcripts (labeled a and b), resulted from the splice-blocking action of TPCN2-MO-S (only exons 1–4 are shown). (Di) A representative 2% agarose gel electrophoresis showing the RT-PCR products after the F+R1 and F+R2 primer sets were used to amplify different portions of the tpcn2 mRNA transcript. β-actin was used as an internal control. (Dii) Bar charts to show the mean ± SEM knockdown efficiency of TPCN2-MO-S, which was evaluated from agarose gels (n=3), such as the one shown in panel Di. In A-C, all the diagrams were drawn to scale; scale bar, 20 bp.

3.2. Effect of CRISPR/Cas9 knockout of TPC2 on the development of SMCs

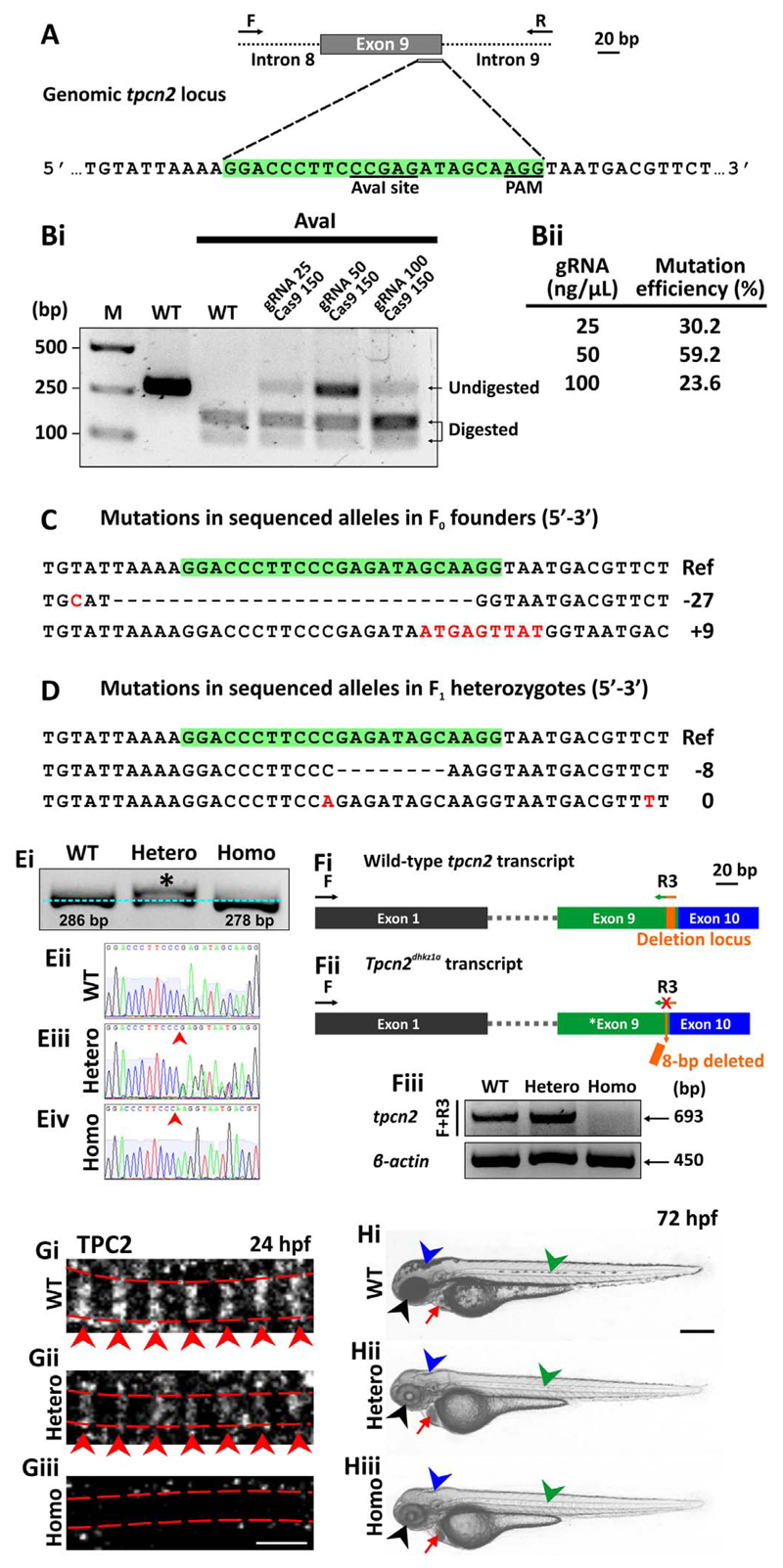

To further validate the MO-based TPC2-knockdown results, the CRISPR/Cas9 genome-editing tool was applied to knockout TPC2 in zebrafish using a tpcn2-specific gRNA (Fig. 2A,2B). The results suggested that both insertion and deletion were observed in the tpcn2 locus of the F0 embryos that were co-injected with 50 ng/μL gRNA and 150 ng/μL Cas9 mRNA (Fig. 2C). This is consistent with the mosaic pattern of mutations that have previously been reported in CRISPR/Cas9 founder fish (Hruscha et al., 2013; Varshney et al., 2015). Further outcrossing of the F0 founder fish led to the identification of two germline transmitted tpcn2 mutant alleles in the F1 progeny: one with an 8 bp-deletion and another with a two single point mutations, one silent mutation in exon 9 and the other in the intronic region outside the splice site of tpcn2 (Fig. 2D). Eventually, a tpcn2 mutant line that carried the 8 bp-deletion mutation was established (Fig. 2E-2H) and this was named tpcn2dhkz1a according to the ZFIN zebrafish nomenclature guideline (http://zfin.org). The mutation was confirmed both at the DNA level, using PCR (Fig. 2Ei) and Sanger sequencing analysis (Fig. 2 Eii-2Eiv), and at the RNA level using RT-PCR (Fig. 2F). We suggest that this 8 bp-deletion leads to a frame-shift mutation at amino acid (aa) position 228 of TPC2, which generates a premature stop codon in the protein coding region, and potentially leads to a loss of protein expression. We also confirmed the mutation at the protein level by whole-mount immunohistochemistry, and demonstrated that the characteristic TPC2 striations (see red arrowheads) observed in the SMC sarcomeres of WT embryos (Fig. 2Gi; Kelu et al., 2015) were absent in the homozygotes (Fig. 2Giii). Other defects seen in the TPC2 mutants included a loss of pigmentation and an accumulation of red blood cells in the heart (Fig. 2H). In the former, ~14% (n=237) and ~23% (n=121) of the tpcn2dhkz1 heterozygous and homozygous embryos, respectively, displayed a reduction in pigmentation, which was evident at 72 hpf (Fig. 2Hii, 2Hiii). In contrast to the normally pigmented siblings, however, embryos with reduced pigmentation never survived to adulthood.

Fig. 2.

CRISPR/Cas9-induced mutagenesis of tpcn2. (A) Design of the 23-bp tpcn2 target sequence. (Bi) Evaluation of the mutation efficiency (with/without AvaI digestion) in the F0 injected embryos as shown by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. The incomplete digestion observed might be due to the presence of a mutation within the restriction site. M is the DNA marker. (Bii) The mutation efficiency in embryos injected with different concentrations of gRNA; this was calculated by dividing the band intensity of the undigested band by the intensity of the undigested and digested bands. (C,D) Sanger sequence analysis of (C) two representative mutant alleles found in the F0 founder embryos and of (D) two separate germline transmitted mutant alleles, which were identified in two F1 heterozygous fish after the F0 founder fish were outcrossed. Ref is the reference sequence. (Ei) Representative 3% agarose gel electrophoresis showing the genotype of the tpcn2dhkz1a mutant. In the heterozygote, there are two bands; this is due to the formation of a DNA heteroduplex, comprising the WT and mutant DNA, with the latter migrating more slowly. (Eii-Eiv) This was confirmed by subsequent Sanger sequence analysis of the corresponding DNA samples. The red arrowheads indicate the location of the 8-bp deletion. (Fi) The wild-type tpcn2 mRNA transcript (showing just exons 1, 9 and 10) and the design of the forward (F) and reverse (R3) primers used for RT-PCR. The target sequence of R3 spans the deletion locus in the tpcn2dhkz1a mutant transcript (see orange rectangle in exon 9). (Fii) The tpcn2dhkz1a mutant mRNA transcript (showing just exon 1, the mutated exon 9, and exon 10), and showing the location of the 8-bp deletion (see orange arrow in exon 9). (Fiii) Representative 2% agarose gel electrophoresis showing the absence of the RT-PCR product in the tpcn2dhkz1a homozygote using the F+R3 primer set. β-actin was used as the internal control. (Gi-Giii) Representative confocal single optical sections of SMCs in (Gi) wild-type and (Gii-Giii) tpcn2dhkz1a mutant embryos at 24 hpf, after they were immunolabeled with the anti-TPC2 antibody, to show the down-regulation and disappearance of TPC2 striations, respectively. The red dashed lines indicate the SMC boundaries, which were revealed by phalloidin-labeling (data not shown); whereas the red arrowheads indicate the TPC2 banding pattern of localization. (Hi-Hiii) Representative bright-field images of: (Hi) wild-type, and (Hii-Hiii) tpcn2dhkz1a mutant embryos at 72 hpf to show the reduction in pigmentation in the eye, head, and trunk of the mutant larvae (see black, blue, and green arrowheads, respectively). An accumulation of blood cells was also seen in the heart of the mutants (see red arrows). In panels (E-H), WT, Hetero, and Homo are wild-type, heterozygotes and homozygotes, respectively. Scale bars, 3 μm in panel (G); and 250 μm in panel (H).

3.3. Muscle cell morphology following MO-mediated knockdown and CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout

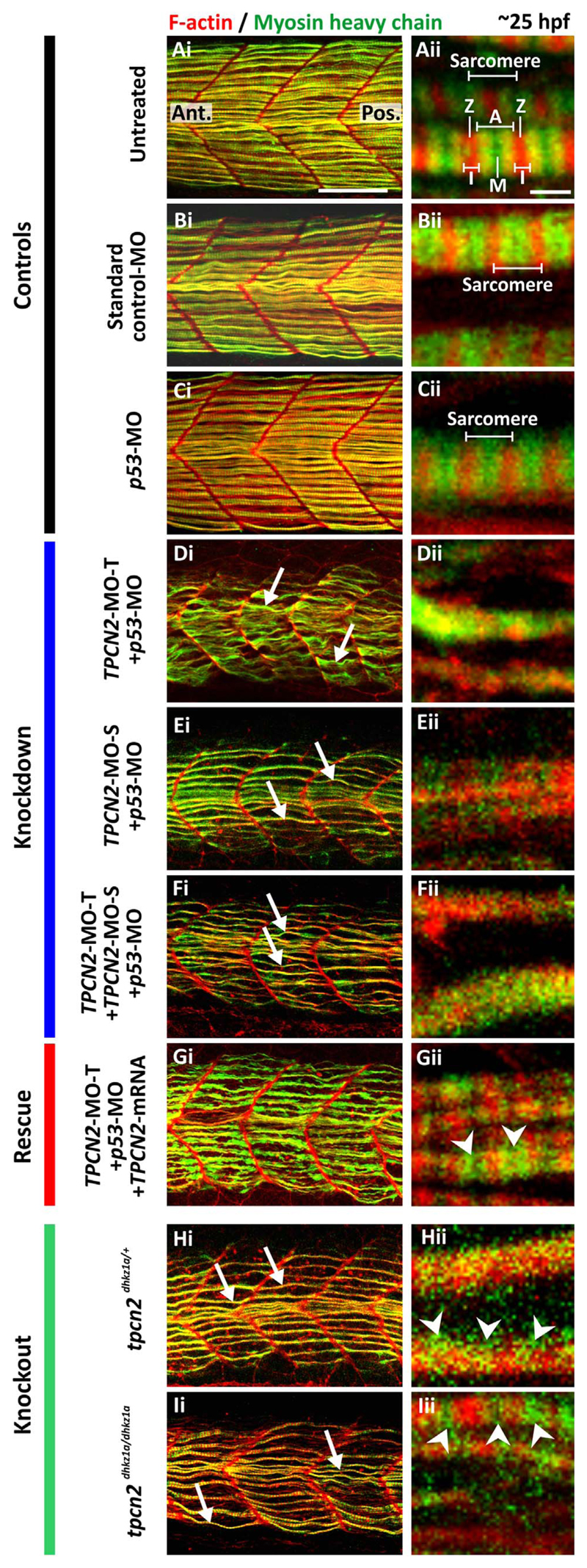

To examine the status of muscle development following TPC2-knockdown and -knockout, two major muscle proteins, F-actin and myosin heavy chain, were visualized using fluorescently-labeled phalloidin and via immunolabelling with the F59 antibody, respectively. Labeling was performed on whole-mount embryos (at 25 hpf) that were either untreated (Fig. 3A), or were injected at the 1- to 4-cell stage (~30–60 mpf) with: ~5 ng standard control-MO (Fig. 3B); ~7.5 ng p53-MO (Fig. 3C); ~2.5 ng TPCN2-MO-T+ p53-MO (Fig. 3D); ~5 ng TPCN2-MO-S + p53-MO (Fig. 3E); ~1.3 ng TPCN2-MO-T+~1.3 ng TPCN2-MO-S + p53-MO (Fig. 3F); or ~2.5 ng TPCN2-MO-T+ p53-MO+~50 pg tpcn2 mRNA (Fig. 3G). In addition, labeling was conducted on whole-mount heterozygous and homozygous tpcn2dhkz1a mutant embryos (Fig. 3H,3I). When the F-actin and myosin heavy chain images were superimposed, the morphology of the myotome and somites as well as the width and shape of the myofibers were revealed at low magnification (Fig. 3Ai-3Ii), whereas information regarding the acto-myosin banding structure of the sarcomeres was revealed at high magnification (Fig. 3Aii-3Iii).

Fig. 3.

Effect of MO-based knockdown (without and with mRNA rescue) and CRISPR/Cas9-knockout of TPC2 on the organization of the trunk musculature and the formation of the sarcomeres. Embryos were (A) untreated or (B-G) injected with: (B) ~5 ng standard control-MO; (C) ~7.5 ng p53-MO; (D) ~2.5 ng TPCN2-MO-T with p53-MO; (E) ~5 ng TPCN2-MO-S with p53-MO; (F) ~1.3 ng TPCN2-MO-T+~2.5 ng TPCN2-MO-S with p53-MO; or (G) ~2.5 ng TPCN2-MO-T with p53-MO and ~50 pg tpcn2 mRNA. In addition, representative (H) heterozygous and (I) homozygous tpcn2 mutants are shown. All embryos were fixed at ~25 hpf and dual-labeled with phalloidin and the F59 antibody, to visualize F-actin (in red) and myosin heavy chain (in green) in the trunk musculature, respectively. Panels show a series of optical sections projected as single images at (Ai-Ii) low and (Aii-Iii) higher magnification when the red and green channels are merged; overlapping regions are shown in yellow. The higher magnification images of the SMC myofibers, reveal the presence or absence of the sarcomeric banding pattern of the F-actin and myosin heavy chain. The white arrows in panels Di-Fi, Hi-Ii show examples of elongated (flexuous) SMC myofibers; ‘A’, ‘I’, ‘M’ and ‘Z’ in panel Aii indicate the A-band, I-band, M-line and Z-line of a sarcomere respectively; and the white arrowheads in panels Gii-Iii indicate the appearance of some banding but clear sarcomeres are not obvious. Ant. and Pos. in panel Ai are anterior and posterior, respectively. Scale bars, 50 μm in panels Ai-Ii; and 2 μm, in panels Aii-Iii.

After MO-based TPC2-knockdown, the fluorescent images show that U-shaped somites were formed in the anterior trunk instead of the usual chevron-shaped somites seen in the uninjected, standard control-MO and p53-MO controls (compare Fig. 3Di-3Fi with Fig. 3Ai-3Ci). In addition, the width of the myotome was reduced in the MO-injected embryos (Fig. 3Di-3Fi). Furthermore, in the controls, myofibrils were packed together into longitudinal bundles to form well-organized myofibers (Fig. 3Ai-3Ci). However, in the TPC2 morphants, the SMC myofibrils were not aligned into bundles laterally and they appeared to be less well organized (see white arrows in Fig. 3Di-3Fi). The effect of TPC2-knockdown could also be observed when visualizing the SMCs at high magnification (Fig. 3Dii-3Fii), such that the usual striated pattern of the sarcomeres was absent. This is in contrast to the normal actomyosin banding in the sarcomeres of the control embryos (Fig. 3Aii-3Cii). The co-injection of a mutant tpcn2 mRNA that is not recognized by TPCN2-MO-T (Kelu et al., 2015), resulted in some of the myotome defects being rescued; for example, the myotome width was greater, and the myofibrils were more aligned into bundles in these rescued embryos than in the MO-injected embryos (compare Fig. 3Gi with 3Di). In addition, the higher magnification images show that the banding pattern in the SMC myofibrils was somewhat restored in the TPCN2-MO-T+ tpcn2 mRNA-injected embryos (see white arrowheads in Fig. 3Gii) although distinct sarcomeres were not apparent.

Whole-mount labeling of F-actin and the myosin heavy chain was also conducted on the heterozygous and homozygous tpcn2dhkz1a mutant embryos (Fig. 3H,3I). In both cases, many of the MO-induced phenotypes were recapitulated, such that there was a decreased myotome width, the shape of the somites was affected, and the SMC myofibrils were disorganized and not aligned into bundles (see arrows in Fig. 3Hi,3Ii). The higher magnification images show that the usual sarcomeric pattern of the SMC myofibrils was also disrupted in many areas of the myotome (see arrowheads in Fig. 3Hi,3Ii).

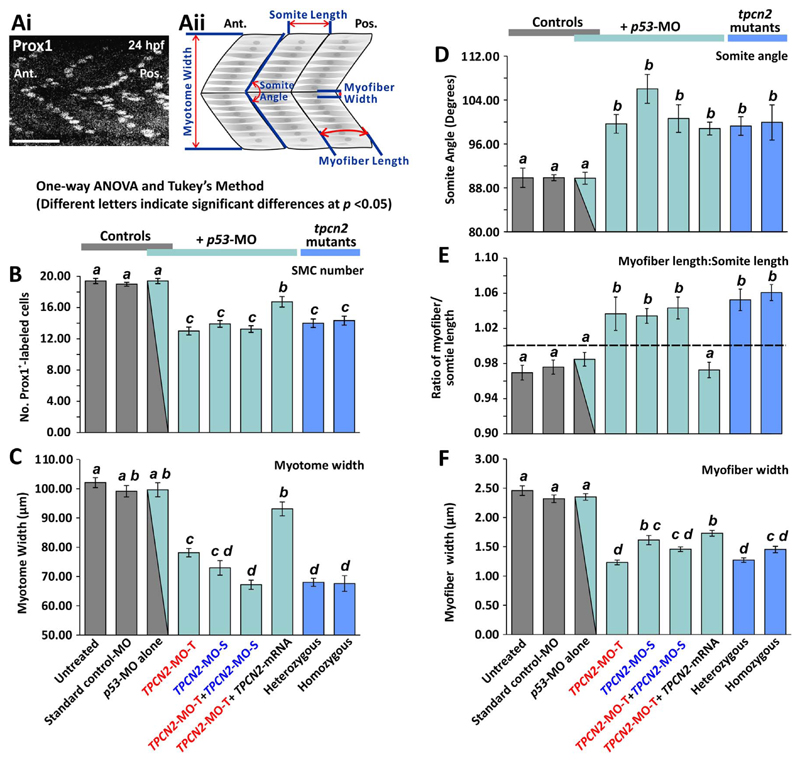

The extent of disruption in the development of the trunk musculature following MO-based TPC2-knockdown ± rescue with tpcn2 mRNA, and in the TPC2 mutants, was quantified (Fig. 4). An anti-prox1 antibody was used to label the SMC nuclei in order to help quantify the number of SMCs present in each somite block (Brennan et al., 2005; Lobbardi et al., 2011). A representative example of prox1-labeled nuclei in the SMCs of an untreated control embryo at ~24 hpf is shown in Fig. 4Ai. Measurements were made (as shown in Fig. 4Aii) using the stack of confocal images obtained after whole-mount fluorescent labeling, which were then projected as a single image. In total, five main parameters were quantified: 1) The number of SMCs (n≥12 from at least 4 embryos; Fig. 4B); 2) the myotome width (n≥12 from at least 4 embryos; Fig. 4C); 3) the somite angle (n≥12 somites from at least 4 embryos; Fig. 4D); 4) the extent of myofiber straightness, determined by calculating the myofiber length:somite length ratio (n≥72 SMCs in n≥24 somites were measured from at least 4 embryos; Fig. 4E); and 5) the myofiber width (n≥40 myofibers from at least 4 embryos; Fig. 4F).

Fig. 4.

Quantification of the effect of MO-based knockdown (without/with mRNA rescue) and CRISPR/Cas9-knockout of TPC2 on the organization of the trunk musculature and the formation of the sarcomeres. (Ai) The number of SMCs in each somite was determined via immunolabelling embryos fixed at ~24 hpf with an anti-prox1 antibody (a representative example of an untreated control is shown). Scale bar, 50 μm. (Aii) Schematic to show the various dimensions of the trunk musculature and SMC myofibers that were measured using series of optical sections projected as single images from the fluorescently-labeled embryos at ~25 hpf (for representative examples, see Fig. 3), in order to determine the level of disruption on SMC development following TPC2 knockdown or knockout. (B-F) Bar charts to show the mean ± SEM: (B) number of SMCs; (C) myotome width, and (D) somite angle, (all n≥12, from 3 somites in ≥4 embryos); (E) myofiber length: somite length ratio (these lengths were measured in n≥72 myofibers and n≥24 somites, respectively ≥4 embryos); and (F) myofiber width (n≥40, from 3 somites in ≥4 embryos). The dashed black line in panel (E) indicates a myofiber: somite length ratio of 1. Statistical analysis was carried out using one-way ANOVA and significance differences (at p < 0.05) as shown by the different letters, a-d between any pair of groups was determined using the Tukey's post hoc method. Thus, significant differences between groups were denoted by different letters whereas groups where no significant differences were observed displayed the same letter.

The parameters measured for the TPC2-knockdown/knockout groups; i.e., the TPCN2-MO-T, TPCN2-MO-S and TPCN2-MO-T+TPCN2-MO-S morphants, as well as the heterozygous and homozygous tpcn2dhkz1a mutants, were all significantly different (at p < 0.5) from those in the controls; i.e., untreated, standard control-MO, and p53-MO (see Fig. 4B-4F). In particular, two of the qualitative observations of the muscle defects observed in the TPC2 morphants and mutants were supported by the quantitative measurements (see Fig. 4D, 4E). First, the TPC2-knockdown/knockout groups showed a somite angle > 100°. This is significantly different (at p < 0.5) from the controls, which exhibited a somite angle of ~90° (see Fig. 4D). Second, the TPC2-knockdown/knockout groups exhibited a myofiber length:somite length ratio > 1 (see the dashed line in Fig. 4E), which indicates a more disorganized phenotype of the SMC myofibers in the TPC2 morphants and mutants. This is in contrast to the ratio of < 1 measured in the various control groups. In addition, both the TPCN2-MO-S alone and TPCN2-MO-T+ TPCN2-MO-S groups were able to recapitulate the disruptive effects shown in the TPCN2-MO-T alone group; they therefore help to validate the specificity of our original TPCN2-MO-T. With regards to the rescue of the TPCN2-MO-T morphants using a mutant tpcn2 mRNA, the measurements of all the parameters except the somite angle (Fig. 4D), gave mean values that were significantly different from the TPCN2-MO-T alone group (see Fig. 4B,4C,4E,4F). This suggests that the TPCN2-MO-T-induced phenotypes could be partially rescued. In the case of the myotome width (Fig. 4C) and myofiber:somite length ratio (Fig. 4E), the rescue was able to reverse the effect of the TPC2-knockdown to a level that was not significantly different from the controls. In addition, most of the phenotypes generated in the TPC2 morphants were recapitulated by the heterozygous and homozygous tpcn2dhkz1a mutant (Fig. 4B-4F); this further substantiates the specificity of the TPCN2-MOs used. Statistical testing indicated that when comparing the various control groups there were no significant differences for any of the parameters measured (denoted by the same letter - ‘a’ – above each bar on the graphs). This suggests that injecting the standard control-MO or p53-MO resulted in the normal development of the SMCs as shown in the untreated control group. On the other hand, whereas the TPC2-knockdown/knockout groups were significantly different from the controls (shown by the use of different letters – ‘b’, ‘c’ or ‘d’ - above the bars of the graphs), there was also sometimes variation observed between the groups (see Fig. 4C-4E). This might suggest that TPCN2-MO-T+ TPCN2-MO-S have a different level of efficacy (as shown by the different effective-dosages used), and it indicates the presence of variable expressivity of the tpcn2dhkz1a mutation among the heterozygote and homozygote groups. In spite of the slight differences observed in the measurements in the TPC2-knockdown/knockout groups, the data clearly suggest that TPC2 function is crucial for both SMC myofibrillogenesis and patterning of the myotome.

3.4. Effect of bafilomycin A1 and trans-ned-19 on the development of the trunk musculature

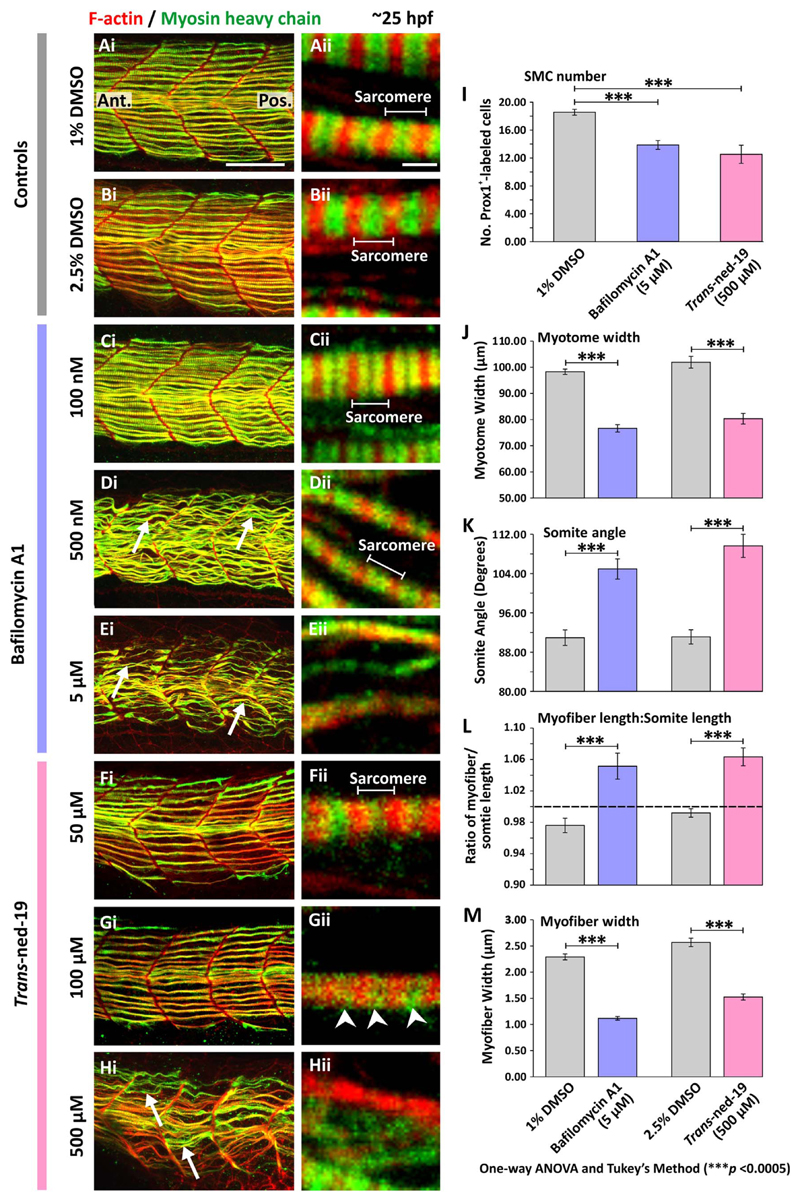

TPC2 was also inhibited both directly and indirectly using a pharmacological approach via incubation with trans-ned-19 or bafilomycin A1, respectively. Embryos were fixed at ~25 hpf and then F-actin and myosin heavy chain were labeled. The merged F-actin and myosin heavy chain images are shown in at low and higher magnification in Fig. 5Ai-5Hi and Fig. 5Aii-5Hii, respectively.

Fig. 5.

Effect of bafilomycin A1 and trans-ned-19 on the organization of the trunk musculature and the formation of the sarcomeres. At 17 hpf, embryos had the terminal portion of the tail excised and then were treated with either: (A) 1% DMSO or (B) 2.5% DMSO in Danieau's solution (controls of the bafilomycin A1 and trans-ned-19 treatment, respectively), or (C-E) bafilomycin A1 at: (C) 100 nM, (D) 500 nM, or (E) 5 μM; or (F-H) trans-ned-19 at (F) 50 μM, (G) 100 μM or (H) 500 μM. All the embryos were fixed at ~25 hpf and dual-labeled with phalloidin and the F59 antibody, to visualize F-actin (in red) and myosin heavy chain (in green) in the trunk musculature, respectively. The panels show a series of optical sections projected as single images at (Ai-Hi) low and (Aii-Hii) higher magnification when the red and green channels are merged; overlapping regions are shown in yellow. The higher magnification images of the SMC myofibers reveal the presence or absence of the sarcomeric banding pattern of the F-actin and myosin heavy chain. The white arrows in panels Di, Ei and Hi show examples of elongated SMC myofibers; and the white arrowheads in panel Gii indicate the appearance of some banding but clear sarcomeres are not obvious. Ant. and Pos. in panel Ai are anterior and posterior, respectively. Scale bars, 50 μm in panels Ai-Hi; and 2 μm, in panels Aii-Hii. (I-M) Quantification of the effect of bafilomycin A1 and trans-ned-19 on the organization of the trunk musculature and the formation of the sarcomeres. These bar charts show the mean ± SEM: (I) number of SMCs; (J) myotome width, and (K) somite angle, (all n=12 from 4 embryos); as well as the (L) myofiber length: somite length ratio (these lengths were measured in n=72 myofibers from 4 embryos); and (M) myofiber width (n=40, from 4 embryos). The dashed black line in panel (L) indicates a myofiber: somite length ratio of 1. The asterisks indicate statistically differences at p < 0.0005 (***).

Control embryos were treated with either 1% DMSO in Danieau's solution (which corresponds to the highest % of DMSO used in the bafilomycin A1 incubations; Fig. 5A) or 2.5% DMSO in Danieau's solution (corresponding to the highest % of DMSO used in the trans-ned-19 experiments; Fig. 5B). Bafilomycin A1 was used at 100 nM (Fig. 5C), 500 nM (Fig. 5D), and 5 μM (Fig. 5E); whereas trans-ned-19 was used at 50 μM (Fig. 5F), 100 μM (Fig. 5G), and 500 μM (Fig. 5H). The results suggest that bafilomycin A1 impedes the development of the SMCs in the trunk musculature in a dose-dependent manner. At 100 nM the overall chevron shape of the somites was maintained but the SMC myofibers exhibited a slightly disorganized flexuous morphology (Fig. 5Ci). However, the normal sarcomeric banding pattern was still evident (for example, compare Fig. 5Cii with the 1% DMSO treated control in Fig. 5Aii). At 500 nM, the somites had a more U-shaped morphology, and the SMC myofibers had an even more flexuous morphology (see white arrows in Fig. 5Di). In addition, the myofibrils were narrower but the normal pattern of sarcomeric banding was still apparent (Fig. 5Dii). At 5 μM, the somites had a distinctly U-shaped morphology, and the width of the entire myotome was noticeably decreased (Fig. 5Ei). In addition, the sarcomeric patterning in the myofibrils was lost at this concentration (Fig. 5Eii). Treatment with trans-ned-19 also inhibited the development of the SMCs in a dose-dependent manner, especially with regards to the sarcomeric integrity (see Fig. 5Fii-5Hii). Treatment with trans-ned-19 at 500 μM produced a similar level of muscle disruption as bafilomycin A1 at 5 μM (i.e., compare Fig. 5Hi and 5Hii with Fig. 5Ei and 5Eii). Thus, embryos developed with U-shaped somites (Fig. 5Hi); the SMC myofibers were disorganized (see arrows in Fig. 5Hi) and there was an absence of the usual striated banding pattern in the sarcomeres, when compared with the 2.5% DMSO-treated controls (compare Fig. 5Hii with 5Bii). The phenotype of the somites following treatment with bafilomycin A1 or trans-ned-19 was somewhat similar to that observed following TPC2-knockdown with TPCN2-MO-T (compare Fig. 5Ei and 5Hi with Fig. 3Di).

To quantify the effect of the bafilomycin A1 and trans-ned-19 treatments, the same set of parameters and criteria used to quantify the effect of TPC2-knockdown and knockout (Fig. 4A) were applied for the pharmacological treatment data (see Fig. 5I-5M). Embryos treated with 5 μM bafilomycin A1 or 500 μM trans-ned-19 were chosen for measurements, and on the whole, 1% and 2.5% DMSO, respectively were used as the controls. However, when the number of SMCs was quantified, 1% DMSO was used as the control for both treatments as a higher stock concentration of trans-ned-19 was prepared for these experiments. The results of the one-way ANOVA statistical analysis followed by the post hoc test (Tukey's Method) revealed that all the parameters measured in the bafilomycin A1 or trans-ned-19 treatment groups were significantly different from the respective controls at p < 0.0005 (see Fig. 5I-5M). Taken together, these data suggest a severe disruption of SMC differentiation as well as myotomal patterning of the trunk musculature after depletion of Ca2+ in the acidic organelles with bafilomycin A1 or inhibition of NAADP-mediated Ca2+ signaling with trans-ned-19.

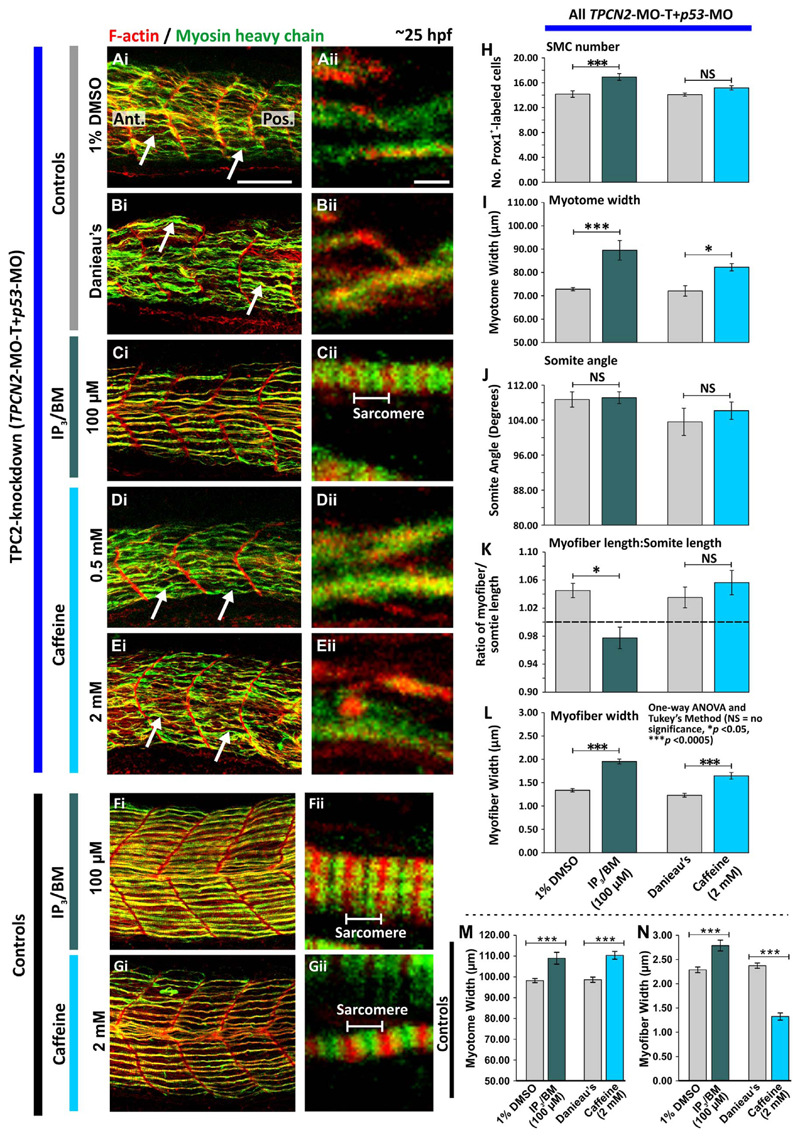

3.5. Effect of IP3/BM and caffeine on the development of the trunk musculature and muscle-generated Ca2+ signals after TPC2-knockdown

To test whether the morphological defects observed in the SMCs of the TPC2 morphants could be rescued by stimulating the IP3Rs or RyRs to release Ca2+, morphants generated via the injection of TPCN2-MO-T+ p53-MO were tail-cut and then incubated at ~17 hpf with IP3/BM (at 100 μM) or caffeine (at 0.5 mM or 2.0 mM); these are agonists of the IP3R and RyR, respectively. In addition, some tail-cut embryos were incubated with 1% DMSO in Danieau's solution or in Danieau's solution alone as controls for the IP3/BM and caffeine treatments, respectively. For comparison, some embryos were not injected with TPCN2-MO-T+ p53-MO, but they were still tail-cut and treated with 100 μM IP3/BM, 2 mM caffeine, 1% DMSO or Danieau's solution. All the embryos were then fixed at ~25 hpf and the F-actin and myosin heavy chain were labeled as described for the previous experiments (Fig. 6Ai-6Gi, 6Aii-6Gii). Similar morphological defects in the SMCs of the TPC2 morphants were observed in the embryos incubated with 1% DMSO (in Danieau's solution) or in Danieau's solution alone (compare Fig. 6Ai with Fig. 6Bi). These included U-shaped somites and disorganized and flexuous SMC myofibers (Fig. 6Ai,6Bi). Following treatment with 100 μM IP3/BM, the trunk and SMC myofibers regained a degree of organization. For example, the overall shape of the somites appeared more chevron-like, rather than U-shaped (compare Fig. 6Ci with 6Ai). In addition, there was evidence of the usual sarcomeric banding pattern, including (to a certain extent) the normal overlapping of the actin and myosin heavy chains, (Fig. 6Cii). In contrast, treatment with caffeine did not result in a robust rescue of the TPC2-knockdown phenotype in the SMCs. Following treatment with 0.5 mM or 2 mM caffeine, morphants were phenotypically similar to the Danieau's solution controls (compare Fig. 6D and 6E with 6B), such that the somites still showed a U-shaped morphology, and the SMC myofibers were disorganized and exhibited a similar flexuous morphology as the Danieau's solution controls (compare Fig. 6Di and 6Ei with 6Bi). In addition, the normal actomyosin banding pattern remained absent (compare Fig. 6Dii and 6Eii with 6Bii). Treatment with IP3/BM or caffeine in uninjected (control) embryos also induced a number of changes in the development of the myotome (Fig. 6F,6G); for example, the width of the myotome and width of the myofibers appeared to be affected (Fig. 6Fi, 6Gi), although a distinct sarcomeric banding pattern was still observed (Fig. 6Fii, 6Gii).

Fig. 6.

Effect of IP3/BM and caffeine on the organization of the trunk musculature and the formation of the sarcomeres after TPC2-knockdown. Embryos were (A-E) injected with TPCN2-MO-T and p53-MO at the 1-cell stage or (F,G) allowed to develop without MO injection. At 17 hpf, the terminal portion of the tail was excised after which embryos were treated with either: (A) 1% DMSO in Danieau's solution (control of the IP3/BM treatment); (B) Danieau's solution alone (control of the caffeine treatment), (C,F) IP3/BM at 100 μM; or (D,E,G) caffeine at (D) 0.5 mM or (E,G) 2 mM. Embryos were then fixed at ~25 hpf, and dual-labeled with phalloidin and the F59 antibody, to visualize F-actin (in red) and myosin heavy chain (in green) in the trunk musculature, respectively. The panels represent a series of optical sections projected as single images at (Ai-Gi) low and (Aii-Gii) higher magnification when the red and green channels are merged; overlapping regions are shown in yellow. The higher magnification images of the SMC myofibers reveal the presence or absence of the sarcomeric banding pattern of the F-actin and myosin heavy chain. The white arrows in panels Ai, Bi, Di and Ei, show examples of elongated SMC myofibers. Ant. and Pos. in panel Ai are anterior and posterior, respectively. Scale bars, 50 μm in panels Ai-Gi; and 2 μm, in panels Aii-Gii. (H-L) Quantification of the effect of IP3/BM and caffeine after TPC2-knockdown on the organization of the trunk musculature and the formation of the sarcomeres. These bar charts show the mean ± SEM: (H) number of SMCs; (I) myotome width, and (J) somite angle, (all n=12 from 4 embryos); as well as the (K) myofiber length: somite length ratio (these lengths were measured in n=72 myofibers from 4 embryos); and (L) myofiber width (n=40, from 4 embryos). The dashed black line in panel (K) indicates a myofiber: somite length ratio of 1. (M,N) Quantification of the effect of IP3/BM and caffeine in control embryos (without TPC2 knockdown) on (M) the myotome width (n≥9, from ≥3 embryos), and (N) myofiber width (n≥30, from ≥3 embryos). The asterisks indicate statistically differences at p < 0.05 (*) and p < 0.0005 (***).

The IP3/BM and caffeine data were quantified using the same set of parameters used previously (i.e., as shown in Fig. 4Aii; Fig. 6H-6N). The results of the one-way ANOVA statistical analysis followed by the post hoc test (Tukey's Method) revealed that all the parameters measured for the TPCN2-MO-T plus IP3/BM treatment group were significantly different from the TPCN2-MO-T plus 1% DMSO controls at p < 0.05 or p < 0.0005, except for the somite angle (Fig. 6J) where the data were not significantly different. When comparing the quantitative data from the IP3/BM treatment group (Fig. 6H,6I,6K,6L) with those in the TPCN2-MO-T plus tpcn2 mRNA group (Fig. 4B,4C,4E,4F), a somewhat similar level of rescue occurred in both cases. In contrast, when comparing the TPCN2-MO-T plus caffeine treatment group with the TPCN2-MO-T plus Danieau's controls, only the myotome width (Fig. 6I) and myofiber width (Fig. 6L) were significantly different at p < 0.05 and p < 0.0005, respectively, indicating that some aspects of the phenotype were rescued when the morphants were treated with caffeine, but the rescue phenotype was not as obvious as that observed in the IP3/BM treatment group.

Quantification of the IP3/BM and caffeine treatments in non-morphant (control) embryos (Fig. 6M,6N) indicated that when compared with the 1% DMSO- and Danieau's- treated solvent controls, 100 μM IP3/BM and 2 mM caffeine stimulated an increase in the myotome width (Fig. 6M). In addition, IP3/BM stimulated an increase in the width of myofibers, whereas caffeine stimulated a decrease in the width. These data were significantly different at p < 0.0005.

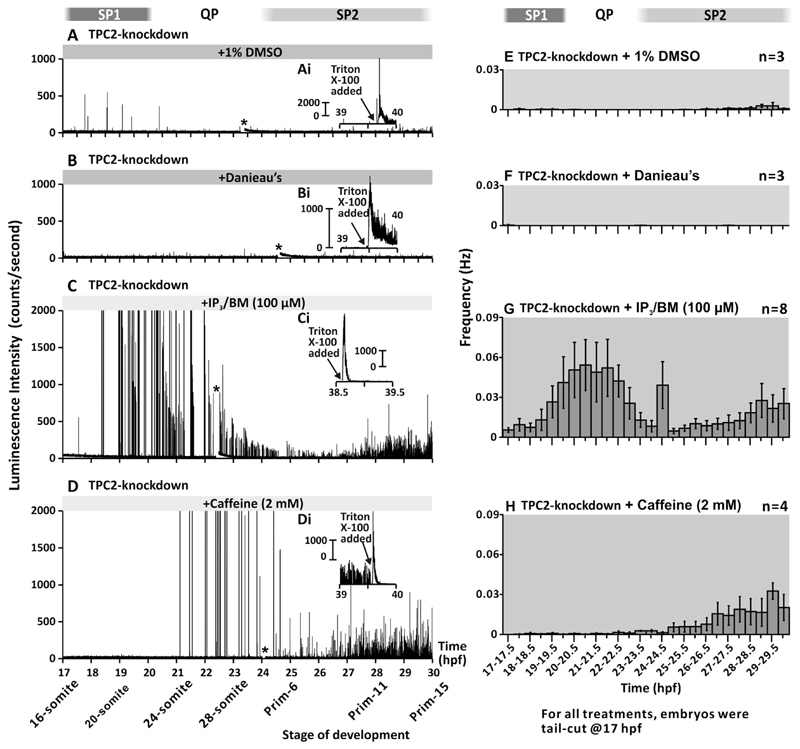

We have previously demonstrated that the MO-based knock-down of TPC2 with the TPCN2-MO-T resulted in a dramatic attenuation of the normal SMC-generated Ca2+ signals (i.e., consisting of signaling period 1, SP1; signaling period 2, SP2; and the quiet period, QP), in the trunk musculature of α-actin-aeq transgenic zebrafish embryos from 17.5 hpf to 30 hpf (Kelu et al., 2015). Here, we tested the ability of IP3/BM or caffeine to rescue the generation of the Ca2+ signals in the muscle following TPC2-knockdown (Fig. 7). Thus, transgenic embryos that had been injected with TPCN2-MO-T plus p53-MO at the 1-cell stage, were exposed to 1% DMSO in Danieau's solution (Fig. 7A,7E), Danieau's solution alone (Fig. 7B,7F), 100 μM IP3/BM (Fig. 7C,7G), or 2 mM caffeine (Fig. 7D,7H) at 17 hpf, after which the Ca2+ signals generated were measured using a photomultiplier tube (PMT). For each treatment, representative examples (Fig. 7A-7D) and the mean ± SEM frequency of n=3 to 8 experiments (Fig. 7E-7H) are shown. The results demonstrate that in the control embryos injected with TPCN2-MO-T plus p53-MO and then incubated with 1% DMSO in Danieau's solution (Fig. 7A) or Danieau's solution alone (Fig. 7B), very few Ca2+ signals were generated in the trunk musculature between 17.5 hpf to 30 hpf. Both the SP1 and SP2 Ca2+ signals were abolished in the control embryos (compare Fig. 7A,7B,7E,7F with Fig. 1Di,1I in Kelu et al., 2015). Addition of Triton X-100 at the end of experiments indicated that the lack of any luminescence signal observed was due to the Ca2+ signals being inhibited rather than from a lack of unreacted aequorin within the embryos (Fig. 7Ai,7Bi).

Fig. 7.

Effect of IP3/BM and caffeine on the trunk Ca2+ signals after TPC2-knockdown. Representative temporal profiles of the luminescence generated by α-actin-aeq transgenic embryos, which were injected with TPCN2-MO-T and p53-MO at the 1-cell stage. At 17 hpf, the terminal portion of the tail was excised, after which embryos were incubated with either: (A) 1% DMSO in Danieau's solution (control of the IP3/BM treatment); (B) Danieau's solution alone (control of the caffeine treatment), (C) IP3/BM at 100 μM; or (D) caffeine at 2 mM. The asterisks indicate times when the luminescence experiments were briefly interrupted by closing the shutter of the detector to check the developmepunctae located adjacent to thtal status and condition of the embryos. (Ai-Di) Temporal profiles of the luminescence when Triton X-100 was applied at the end of each imaging experiment. (E-H) Histograms showing the mean ± SEM frequency of the Ca2+ signals generated every 30 min in the trunk musculature from 17 hpf to 30 hpf in embryos treated as described in panels (A-D), respectively. Calcium signaling periods 1 and 2 (SP1 and SP2), and the signaling quiet period (QP; Cheung et al., 2011) are shown.

When embryos were injected with TPCN2-MO-T plus p53-MO and then incubated with IP3/BM from 17 hpf to 30 hpf, a partial rescue of the muscle-generated Ca2+ signals occurred, such that both the SP1 and SP2 Ca2+ signals showed a distinct degree of recovery when compared with the 1% DMSO controls (compare Fig. 7C,7G with Fig. 7A,7E). The addition of Triton X-100 at the end of the experiment once again indicated that there was still plenty of active aequorin remaining within the SMCs (Fig. 7Ci). In contrast, when TPC2 morphants were exposed to caffeine, there was only a partial rescue of the Ca2+ signals, with the effect being more obvious in SP2 than in SP1 (Fig. 7D,7H). Once again, exposure to Triton X-100 at the end of the experiment suggested that the SMCs contained an ample amount active aequorin to generate detectable signals (Fig. 7Di).

3.6. Gross phenotypic changes and motor behavior following MO-mediated knockdown or CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout of TPC2

In addition to investigating the effect of TPC2 knockdown or knock out on SMC myofibrillogenesis, the effect of these genetic manipulations on the gross morphology and motility of embryos was determined. With regards to the former, bright-field images were acquired of embryos at 25 hpf following TPC2 knockdown (without/with rescue), or knockout, and the level of tail straightening was quantified by measuring the angle between the heart, the anterior end of the yolk sac extension and the tip of the tail (see Supplementary Material and Fig. S1). With regards to the embryo motility, the frequency of the spontaneous coiling behavior of the freely moving embryos, i.e., without being either mounted or anaesthetized, from 16 hpf to 28 hpf was determined by video microscopy (see Supplementary Material and Fig. S2A, 2B), and the touch-evoked response was determined by gently touching embryos at 24 hpf twice on the head to elicit a reaction (see Supplementary Material and Fig. S2C).

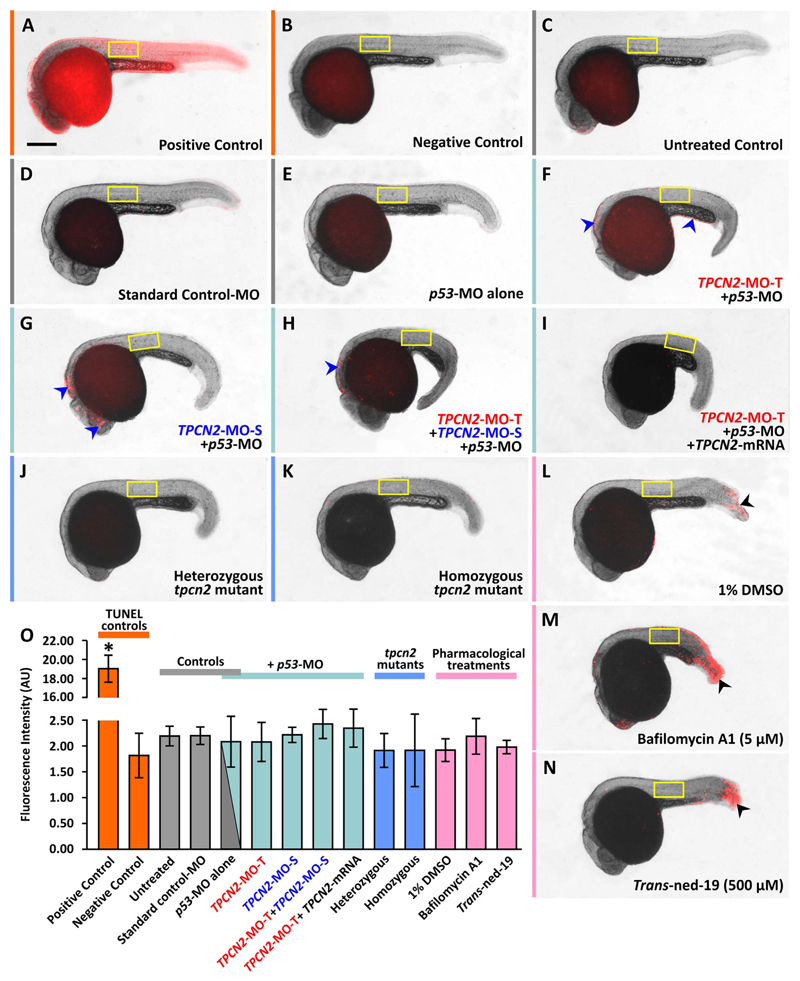

3.7. Investigation of cell deaths after TPC2-knockdown/-knockout or treatment with bafilomycin A1 or trans-ned-19

A TUNEL assay was performed to investigate whether the phenotypic changes (especially the decrease in the number of prox1+-labeled cells) observed following genetic and pharmacological inhibition of TPC2 expression might be due to the induction of cell death (Fig. 8). TUNEL positive control embryos exhibited an elevated level of fluorescence, indicating that the cleaved DNA was labeled successfully (Fig. 8A). In contrast, in the TUNEL negative control group, auto-fluorescence was observed in the yolk but not in the other parts of the embryo (Fig. 8B). In the untreated, standard control-MO and p53-MO controls, sporadic cell death events could be observed in various regions of the body such as the head, yolk extension and tip of the tail (Fig. 8C-8E). However, no cell death was observed in the trunk. Following TPC2 knockdown with TPCN2-MO-T, TPCN2-MO-S, or TPCN2-MO-T+ TPCN2-MO-S, an increase in TUNEL labeling was seen particularly in the eye and hindbrain region of the embryos but again little cell death was observed in the trunk (see Fig. 8F-8H). Embryos injected with TPCN2-MO-T+ tpcn2 mRNA (Fig. 8I) exhibited negligible levels of cell death. In addition, in the heterozygous and homozygous tpcn2dhkz1a mutants, very little cell death was observed (Fig. 8J, 8K). On the other hand, during treatment with bafilomycin A1 or trans-ned-19, a higher level of localized cell death was observed in the ‘wound’ regions following the excision of the tail bud (see black arrowheads in Fig. 8L-8N), but in the main region of the trunk, very little cell death was observed. A region of interest (ROI) was placed over the trunk of embryos and the fluorescence intensity was quantified (Fig. 8O). One-way ANOVA and the post hoc test (Tukey's Method) revealed that (as expected) significant differences (at p < 0.05) in fluorescence intensity were observed between the positive and negative control groups. However, no significant differences were observed when comparing the level of fluorescence in the negative control group with that in the various experimental controls, and when comparing the experimental controls with the other experimental groups.

Fig. 8.

Visualization and quantification of the amount of apoptosis after MO-based knockdown (without and with mRNA rescue), CRISPR/Cas9-knockout of TPC2, or following pharmacological treatment with bafilomycin A1 or trans-ned-19. Embryos were (A-C) untreated or (D-I) injected with: (D) ~5 ng standard control-MO; (E) ~7.5 ng p53-MO; (F) ~2.5 ng TPCN2-MO-T with p53-MO; (G) ~5 ng TPCN2-MO-S with p53-MO; (H) ~1.3 ng TPCN2-MO-T+~2.5 ng TPCN2-MO-S with p53-MO; or (I) ~2.5 ng TPCN2-MO-T with p53-MO and ~50 pg tpcn2 mRNA. (J,K) Representative (J) heterozygous and (K) homozygous tpcn2 mutants are also shown. In addition, wild-type embryos were treated with: (L) 1% DMSO; (M) bafilomycin A1 at 5 μM; or (N) trans-ned-19 at 500 μM. (A-N) All the embryos were then fixed at ~24 hpf, and cells undergoing apoptosis were labeled using the TUNEL assay. These are bright-field images onto which are superimposed the respective fluorescence images showing TUNEL-positive cells in red. The yellow rectangles show the size and location of the regions of interest (ROIs) used for quantification. (A,B) Representative TUNEL (A) positive and (B) negative controls. In panels (L-N), the black arrowheads indicate the elevated levels of apoptosis in the region of the trunk damaged during tail excision. (O) Bar chart to show the mean ± SEM fluorescence intensity within the ROIs (n=3). Statistical analysis was carried out using one-way ANOVA. The asterisk indicates the significance difference (at p < 0.001) between the TUNEL positive control and the other groups, as determined using the Tukey's post hoc method. No other significant differences were found among the groups. Scale bar, 25 μm.

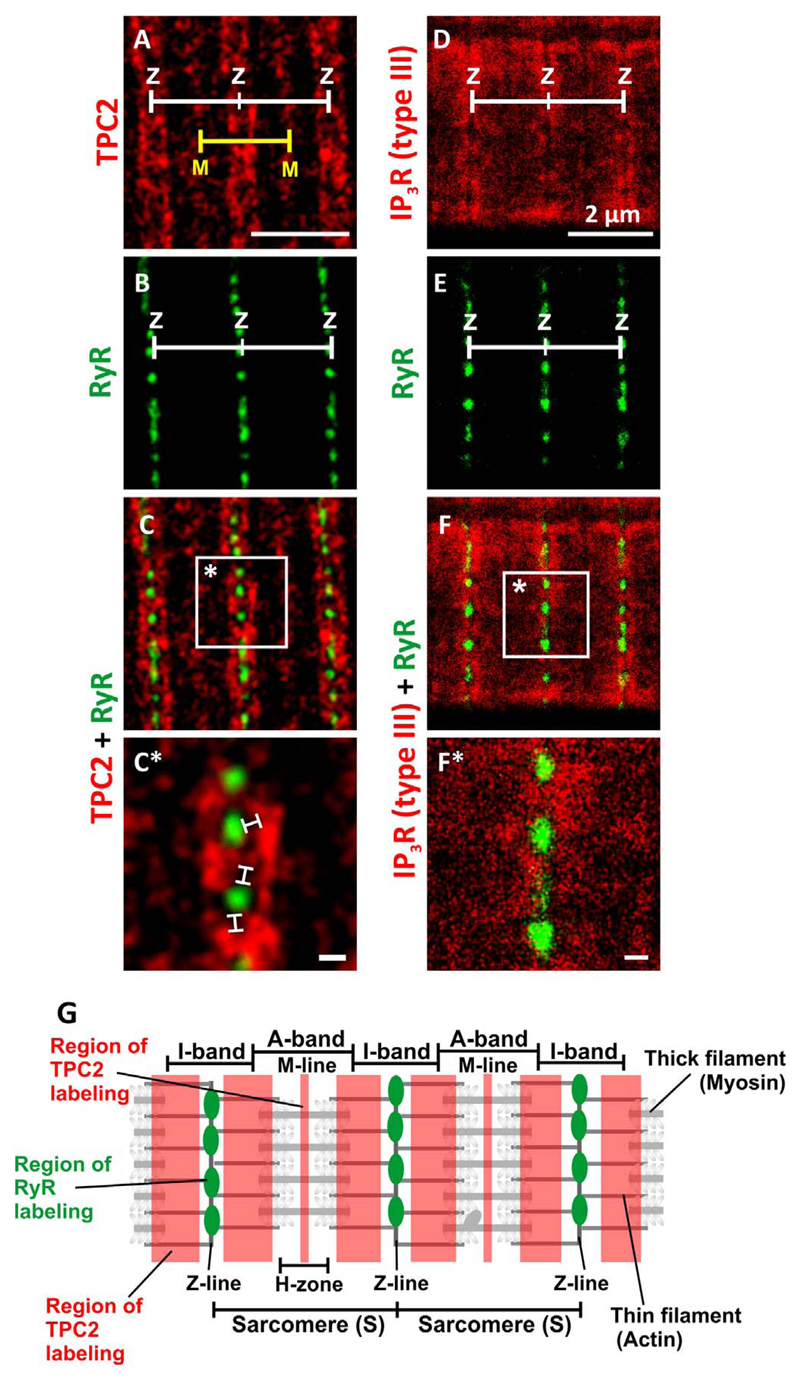

3.8. Dual-colour STED-based super-resolution microscopy of TPC2 and RyR, and of IP3R (Type III) and RyR in mature myotubes of primary cultures

The spatial relationship between RyR and TPC2 and between RyR and IP3R (Type III) in cultured myotubes (prepared from embryos at ~48 hpf), was examined using dual-immunolabelling and dual-colored stimulated emission depletion (STED) super-resolution microscopy (Fig. 9). The representative RyR/TPC2 images (Fig. 9A-9C*) show a striated pattern of TPC2 labeling adjacent to the sarcomeric I-bands. To a lesser extent, TPC2 was also localized adjacent to the H-zones (Fig. 9A,9C; see schematic, Fig. 9G). The RyR appeared as distinct punctae located adjacent to the z-line (Fig. 9B,9C). In the higher magnification image (Fig. 9C*), small TPC2 clusters appeared to be joined in a longitudinal manner to form larger TPC2 clusters, and the exclusion of TPC2 labeling in the center of the I-band region was more evident. In addition, the RyR punctae appeared to be in close apposition to but not touching the TPC2 clusters. Thus, there appeared to be distinct “nano-”gaps that separated the RyR punctae from the TPC2 clusters (Fig. 9C*).

Fig. 9.

Visualization of TPC2, IP3R (type III) and ryanodine receptors (RyR) by dual-immunolabeling and dual-colour stimulated emission depletion (STED) super resolution imaging. Representative examples of muscle cells that were dissociated from the trunk of zebrafish embryos at 48 hpf, plated onto a coverslip for 1 h and then fixed and dualimmunolabeled with either (A-C,C*) the 2137A anti-TPC2 and 34C anti-ryanodine receptor primary antibodies or (D-F,F*) the IP3R (type III) and 34C antibodies. STED images of: (A) TPC2, (B) RyR, and (C) the TPC2 and RyR images when merged, as well as (D) IP3R (type III), (E) RyR and (F) IP3R and RyR images when merged. The regions bounded by the white squares in panels C and F are shown at higher magnification in panels C* and F*. The white lines in panel C* indicate the presence of distinct gaps between the RyR and TPC2 clusters when observed via STED super-resolution imaging. Z and M indicate the Z- and M-lines of the sarcomere, respectively. Scale bars, 2 μm (A-F); and 200 nm (C*,F*). (G) Schematic illustration of two sarcomeres and the relative localization of TPC2 and RyR in the adjacent lysosomes and SR, respectively (see Fig. 10 for a 3D representation of an SMC).

To obtain an approximation of the x,y-resolution of the STED images, a number of the isolated RyR punctae were selected and subjected to analysis. Line-scan analyses were performed across the brightest pixel(s) within a single RyR puncta, and the fluorescence intensity profile obtained was then fitted into a Gaussian distribution, where the full width at half maximum (FWHM) was determined (Hein et al., 2008; Nägerl et al., 2008; Vicidomini et al., 2011). The mean ± SEM resolution for n=3 RyR punctae was calculated to be 77.78 ± 6.23 nm.

The area and dimensions of the RyR punctae/TPC2 clusters and the gaps between the two were measured using the Feret's diameter, which is defined as the perpendicular distance between parallel tangents touching opposite sides of the profile (Walton, 1948); the minimum and maximum Feret's diameter are therefore the minimum (shortest) and maximum (longest) distances, respectively, between any two points within an object after consideration of all possible orientations. All the measurements were done automatically, such that the dual-colour RyR/TPC2 STED images were first subject to thresholding, after which the boundaries of 15 lengths of RyR punctae/TPC2 clusters were auto-traced, and then in total 306 gaps within all the selected puntae/clusters were identified and auto-traced. Following this, gap dimension measurements were carried out automatically. Our calculations revealed that the minimum and maximum Feret's diameter were 52.00 ± 3.00 nm and 87.35 ± 5.23 nm, respectively.

The spatial relationship between RyR and IP3R (type III) in the cultured myotubes was also examined using dual-immunolabelling and dual-colour STED super-resolution microscopy (Fig. 9D-9F*). In these images, the RyR punctae were in close apposition to the IP3R (type III) labeling, and the distinct “gaps” observed in the RyR/TPC2 images were not apparent in the RyR and IP3R (type III) co-labeled cultures. Unfortunately, direct dual-labeling of TPC2 and IP3R (type III), was not feasible due the primary antibodies both being raised in the same host species (rabbit). Nonetheless, by combining the observations from both sets of STED images, we suggest that TPC2 (in the lysosomes) and IP3R (type III; in the SR) are localized adjacent to the sarcomeric I-bands and in the near vicinity of the RyR clusters.

4. Discussion

Here we report that both knockdown and knockout of TPC2 by MOs and CRISPR/Cas9, respectively, resulted in significant developmental defects in the myotome of zebrafish embryos. These observations were recapitulated via the use of two pharmacological inhibitors, i.e., bafilomycin A1 and trans-ned-19, which deplete Ca2+ within lysosomes, and antagonize the NAADP receptor, respectively. Our new data strongly suggest that lysosomal Ca2+ release via TPC2 is crucial for regulating the differentiation of zebrafish non-muscle pioneer SMCs during early embryonic development of the trunk musculature.

The generation of the tpcn2dhkz1a mutant using the CRISPR/Cas9 system phenocopied most, if not all, of the SMC disruption seen in the MO-generated morphants (see Fig. 3 and S1). This provides further evidence to support our original proposition that the phenotypes of the morphants are a result of the specific inhibition of TPC2 expression (Kelu et al., 2015), and not due to non-specific off-target effects, which have sometimes been reported for other MOs (Robu et al., 2007; Eisen and Smith, 2008; Gerety and Wilkinson, 2011; Kok et al., 2015). These TPC2 knockout results, together with those obtained from our TPCN2-MO-T ± TPCN2-MO-S experiments and the pharmacological inhibition of TPC2, provide strong evidence to support our proposition that Ca2+ release via TPC2 plays a crucial and required role in SMC differentiation and subsequent myofibrillogenesis. Interestingly, we observed a complex inheritance pattern of the tpcn2dhkz1a mutation in the mutant line. Since the mutant phenotypes were obvious in the heterozygotes as well as in the homozygotes, the mutant tpcn2 allele might be dominant to the wild-type allele. In addition, it was noted that the phenotypes were only observed in an average of ~78% of the mutant embryos that were examined (heterozygotes: ~76%, n=33; homozygotes: 80%, n=40), which suggests an incomplete penetrance of the mutation. Moreover, we observed a phenotypic variation among different mutant individuals, such that the patterning of the myotome and non-muscle progenitor SMC myofibrillogenesis were disrupted to different extents. This suggests that the mutation was displaying a variable level of expressivity (Jain et al., 2011), which indicates that other genetic factors might also influence the outcome of the phenotype. In particular, we could not exclude the possibility of genetic compensation induced either by tpcn2 paralogs or even non-paralogs (Rossi et al., 2015). Resolving this issue will require further characterization of the tpcn2dhkz1a mutant. Nonetheless, tpcn2 was shown to be disrupted at the level of the gene and mRNA, and TPC2 protein was also shown to be affected in the tpcn2dhkz1a mutant (Fig. 2E-2G).

The number of non-muscle pioneer SMCs generated was shown to be attenuated after interference with TPC2 function via knockdown, knockout, or drug treatments, as revealed by the significant decrease in the number of prox1+ nuclei in each somite (Figs. 4B,5I). Both types of SMCs (i.e., muscle pioneers and non-muscle pioneers) are derived from their progenitor adaxial cells located in the medial region of the segmental plate adjacent to the notochord (Devoto et al., 1996). A subset of adaxial cells are induced to become muscle pioneer SMCs via continual Hedgehog signaling from the notochord and floor plate cells (Du et al., 1997). In contrast, the remaining ~20 adaxial cells migrate through the lateral presomitic cells (destined to become fast muscle cells) to the lateral surface of the myotome where they continue to differentiate into non-muscle pioneer SMCs (Du et al., 1997). At ~10 hpf, i.e., shortly after the commencement of somitogenesis, adaxial cells begin to express various early myogenic markers (Devoto et al., 1996; Roy et al., 2001). At ~15 hpf, they then start to express slow myosin heavy chain, which is distributed randomly in the cytoplasm, and at ~17 hpf, the non-muscle pioneer SMCs begin their migration through the lateral presomitic cells to the periphery of the myotome. Approximately one hour later (i.e., ~18 hpf) prox1 expression is activated (Devoto et al., 1996; Du et al., 1997; Roy et al., 2001).