Abstract

Background:

Mammographic breast density declines during the menopause. We assessed changes in volumetric breast density across the menopausal transition and factors that influence these changes.

Methods:

Women without a history of breast cancer who had full field digital mammograms during both pre- and postmenopausal periods, at least 2 years apart, were sampled from 4 facilities within the San Francisco Mammography Registry from 2007 to 2013. Dense breast volume (DV) was assessed using Volpara™ on mammograms across the time period. Annualized change in DV from pre- to post-menopause was estimated using linear mixed models adjusted for covariates and per-woman random effects. Multiplicative interactions were evaluated between premenopausal risk factors and time to determine if these covariates modified the annualized changes.

Results:

Among the 2,586 eligible women, 1,802 had one pre-menopausal and one post-menopausal mammogram, 628 had an additional peri-menopausal mammogram, and 156 had two perimenopausal mammograms. Women experienced an annualized decrease in DV (−2.2 cm3 [95% CI −2.7, −1.7]) over the menopausal transition. Declines were greater among women with a premenopausal DV above the median (54 cm3) vs. below (DV: −3.5 cm3 vs. −1.0 cm3, p<0.0001). Other breast cancer risk factors including race, BMI, family history, alcohol and postmenopausal hormone therapy had no effect on change in DV over the menopausal transition.

Conclusions:

High premenopausal dense volume was a strong predictor of greater reductions in dense volume across the menopausal transition.

Impact:

We found that few factors other than premenopausal density influence changes in dense volume across the menopausal transition, limiting targeted prevention efforts.

Introduction

Breast density is a measure of the stromal and epithelial tissue in the breast as seen on a mammogram and is a strong risk factor for breast cancer.1–3 Breast density is strongly influenced by age, and studies suggest that many women experience a natural decline in the amount of dense breast tissue with aging.4,5 The most accelerated declines are often observed over the menopausal transition, corresponding with Pike’s hypothesis that the rate of breast tissue aging decreases over menopause, and that the magnitude of this decrease may be influenced by exposure to breast cancer risk factors.6

Previous studies of longitudinal changes in breast density have primarily used area-based breast density assessment to estimate the decline in percent density (the proportion of the total breast area comprised of dense tissue), and found an average annual decline in percent density of 0.5–2%, with the greatest reductions occurring over the menopausal transition.4,5,7–9 Fewer studies have examined changes in area-based absolute density (the amount of dense area), which is believed to be a more etiologically relevant phenotype of breast density for breast cancer risk than percent density, as it reflects the amount of tissue at risk of carcinogenesis.10 One study estimated that women undergoing menopause had a decline in dense area that was 3.39 cm2 larger than age-matched women who remained premenopausal during the same time period.4 Cross-sectional studies comparing breast density in premenopausal and postmenopausal women support this finding11, with a recent study including women from 22 countries estimating that postmenopausal women had a mean dense area that was 3.5 cm2 lower than premenopausal women.12

Not all women experience a decline in breast density with menopause, however. Current research suggests that women with higher baseline breast density have accelerated declines,5,7 and combination postmenopausal hormone users have attenuated declines or increases over time across the menopausal transition.5,7,13 However, findings on the effects of reproductive-related factors and obesity on change in density over time have been mixed across studies.4,5,7–9

Longitudinal changes in breast density are associated with breast cancer risk, and women who experience the greatest declines over time have a reduced risk of breast cancer.14,15 Therefore, identifying factors influencing change across the menopausal transition may improve targeted prevention efforts. Automated, volumetric breast density measures are increasingly used in clinical settings and can monitor changes in breast density over time;16 however, literature quantifying longitudinal change in volumetric breast density is sparse.

The objective of our study was to use volumetric breast density assessment to measure changes in breast density over the menopausal transition in healthy, cancer-free women, and identify risk factors that affect change during this time period.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

Participants were sampled from the San Francisco Mammography Registry (SFMR), a population-based mammography registry collecting demographic, risk factor, and mammographic information on women undergoing mammography in the San Francisco Bay Area. We included four SFMR facilities that obtained raw digital images from Hologic-Selenia mammography machines since 2006. Passive permission to participate in research is obtained at each mammography visit.

Participants

Eligible women had at least two full field digital mammograms between 2007 and 2013, with one premenopausal mammogram, performed prior to self-reported menopause and at least one subsequent postmenopausal mammogram. At least two years were required between the premenopausal and postmenopausal mammogram. The “menopausal transition” is defined as the time between the premenopausal and postmenopausal mammogram for each woman. Women with a personal history of breast cancer, breast implants, or mastectomy and women without cranio-caudal mammogram views were excluded. All mammograms between the premenopausal and postmenopausal mammogram (perimenopausal mammograms) were collected for the current analysis, for a total of 2,586 women and 6,112 mammograms (mean: 2.4 per woman).

Covariate Data

Demographics and risk factor data were self-reported at each mammography visit. Menopause status was determined by asking women if their menstrual periods had stopped and if they were using postmenopausal hormone therapy (HT). Women were classified as postmenopausal if they reported their periods had stopped, for any reason, or if they reported use of postmenopausal HT, regardless of their self-report of menstrual periods. All other women were considered premenopausal. Covariates collected at the time of the premenopausal mammogram included age, race/ethnicity, body mass index (BMI; continuous [kg/m2] and categories [<25kg/m2, 25–29 kg/m2, ≥30 kg/m2]), first-degree family history of breast cancer, parity, age at first birth (nulliparous, <30 years, ≥30 years), and current alcohol use (none, ≤1 drink per day, ≥2 drinks per day). Use of postmenopausal HT was collected at all mammograms subsequent to the premenopausal mammogram and was classified as unknown, no current use, and current use. Among current users, further classification by formulation (estrogen vs. estrogen & progesterone) was available. BMI was collected at each mammogram and change in BMI (kg/m2) was calculated between premenopausal and each subsequent mammogram.

Breast Density Measurement

Raw (“for processing”) mammogram image formats were collected and stored, and Volpara™ automated breast density software was run on all mammograms.

Volpara Software

Volpara™ (Version 1.5.3, Matakina Technology, New Zealand) is a fully-automated software that measures volumetric breast density on full field digital mammography (FFDM) machines. The Volpara proprietary algorithm identifies an area of the breast that is entirely fatty tissue and uses this reference point to estimate the thickness of dense tissue at each pixel in the image, not including the skin. Further detail on the Volpara algorithm is published elsewhere.17 Estimates of dense breast volume (DV) are obtained by summing the estimated dense tissue across all pixels in the breast image, and volumetric percent density (VPD) is obtained by dividing the estimated DV from the total breast volume. Breast density was assessed on cranio-caudal (CC) mammography views. For women with both CC views available on all mammograms (n=2,551), we calculated breast density on the CC view of a randomly chosen side, using the same side for each subsequent mammogram. Among women who had usable CC views from only a single side, we used the available side (n=35) for all images.

Statistical Methods

Characteristics of the study sample at the premenopausal mammogram are summarized by frequency and percentage or median and quartiles. Linear regression, adjusted for age, was used to estimate the effects of premenopausal risk factors on DV at the premenopausal mammogram. These analyses were performed on DV after log transformation and estimates and were then back-transformed to the original scale. We fit linear mixed effects models including all available mammograms across the menopausal transition to estimate the annualized change in DV from the premenopausal mammogram, accounting for correlations within women over time with woman-specific random effects. The associations between baseline and time-dependent (HT only) risk factors on annualized change in DV were assessed by fitting interactions between each risk factor and time (years) since premenopausal mammogram. Separate models were fit for each covariate interaction, and were adjusted for age, time (years), premenopausal BMI, change in BMI, and DV at the premenopausal mammogram. We found that premenopausal DV was strongly associated with annualized changes in DV and premenopausal risk factors (e.g., BMI) were strongly associated with premenopausal DV; therefore, all longitudinal mixed models were additionally adjusted for the interaction between premenopausal DV and time. Models were also fit using relative change in DV (as a percent of baseline). Supplementary analyses examined distribution of annualized changes in DV by premenopausal density and models assessing change in VPD (Supplementary Tables 1 & 2). All analyses were conducted in SAS 9.4.

Results

Characteristics of the study sample at the premenopausal mammogram are reported in Table 1. Of the 2,586 women included, 1,802 (70%) had two mammograms (premenopaual and post-menopausal mammogram only), 628 (24%) had three (additionally one perimenopausal mammogram), and 156 (6%) had four (additionally two perimenopausal mammograms). The median age of women at the premenopausal mammogram was 51 (IQR: 49–52) years. The median BMI at the premenopausal mammogram was 23.3 (IQR: 21.2–26.5) kg/m2 and the median change in BMI from premenopausal to postmenopausal mammogram was 0 (IQR: −0.5, 0.9) kg/m2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 2,586 women in the study.

| n (%) or median (IQR) | |

|---|---|

| Age at premenopausal mammogram | 51 (49, 52) |

| Time between pre- and postmenopausal mammograms (years) | 3.1 (2.5, 3.5) |

| Premenopausal BMI (kg/m2) | 23.3 (21.2, 26.5) |

| Change in BMI* (kg/m2) | 0 (−0.5, 0.9) |

| Premenopausal Dense Volume (cm3) | 54.0 (37.7, 77.8) |

| Premenopausal BMI (kg/m2) | |

| Normal (<25 kg/m2) | 1708 (66.4%) |

| Overweight (25–29 kg/m2) | 562 (21.9%) |

| Obese (>=30kg/m2) | 302 (11.7%) |

| Race (Excludes 3 unknown) | |

| Caucasian | 1451 (56.2%) |

| Asian | 861 (33.3%) |

| Other | 271 (10.5%) |

| Family History Breast Cancer | |

| No | 2093 (81.2%) |

| Yes | 484 (18.8%) |

| Parous | |

| No | 873 (33.8%) |

| Yes | 1712 (66.2%) |

| Age at First Birth | |

| Nulliparous | 873 (33.8%) |

| <30 Years | 692 (26.8%) |

| 30+ Years | 1020 (39.5%) |

| Alcohol Use | |

| None | 1278 (50.7%) |

| <= 1 drink/day | 954 (37.9%) |

| >= 2 drinks/day | 288 (11.4%) |

| Hormone Therapy at any mammogram | |

| No/Unknown | 2210 (85.5%) |

| Yes | 376 (14.5%) |

| Type of HT (Known HT-users only) | |

| Ever Estrogen Only | 262 (69.7%) |

| Ever Estrogen + Progesterone | 97 (25.8%) |

| Unknown | 17 (4.5%) |

| Number of Mammograms | |

| 2 | 1802 (69.7%) |

| 3 | 628 (24.3%) |

| 4 | 156 (6.0%) |

| Previous Biopsies | |

| 0 | 2044 (79.3%) |

| 1 | 351 (13.6%) |

| 2+ | 183 (7.1%) |

Change in BMI was calculated from premenopausal to postmenopausal mammogram.

BMI: Body Mass Index; HRT: hormone replacement therapy.

Associations between demographics and risk factors with DV at the premenopausal mammogram are shown in Table 2. Older age, parity, and younger age at first birth were associated with lower DV at the premenopausal mammogram (all p’s<0.01). Women with a first-degree family history of breast cancer had greater premenopausal DV compared with women without a family history (p<0.001), and women who reported ≥2 drinks per day of alcohol consumption had greater premenopausal DV compared to women consuming <2 drinks per day or women reporting no alcohol use (p<0.001). The greatest differences in premenopausal DV were seen comparing women with a BMI <25 kg/m2, who had a mean DV of 57.7 cm3, to women with BMI’s of 25–29 kg/m2 or >30 kg/m2, who had a mean premenopausal DV of 70.5 and 73.9 cm3, respectively (p<0.001). DV also varied by race/ethnicity, with Caucasian women having the highest mean premenopausal DV of 67.8 cm3, compared to Asian women, who had the lowest premenopausal DV of 52.0 cm3, and women of other racial/ethnic groups who had a mean of 66.2 cm3 (p<0.001).

Table 2.

Associations between demographic and risk factors and premenopausal dense volume (DV).

| N (%) | Dense Volume Mean (95% CI)* | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at premenopausal mammogram | ||

| <50 years | 776 (30.0%) | 56.7 (54.5, 58.9) |

| >=50 years | 1810 (70.0%) | 52.3 (51.0, 53.6) |

| p-value | <.001 | |

| Premenopausal BMI (kg/m2) | ||

| Normal (<25 kg/m2) | 1708 (66.4%) | 49.8 (48.6, 51.1) |

| Overweight (25–29 kg/m2) | 562 (21.9%) | 60.4 (57.7, 63.1) |

| Obese (>=30kg/m2) | 302 (11.7%) | 64.6 (60.7, 68.6) |

| p-value | <.001 | |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian | 1451 (56.2%) | 58.0 (56.4, 59.7) |

| Asian | 861 (33.3%) | 45.6 (44.0, 47.3) |

| Other | 271 (10.5%) | 58.1 (54.5, 61.9) |

| p-value | <.001 | |

| Family History Breast Cancer | ||

| No | 2093 (81.2%) | 52.5 (51.2, 53.7) |

| Yes | 484 (18.8%) | 58.7 (55.9, 61.6) |

| p-value | <.001 | |

| Parous | ||

| No | 873 (33.8%) | 59.4 (57.3, 61.6) |

| Yes | 1712 (66.2%) | 50.8 (49.5, 52.2) |

| p-value | <.001 | |

| Age at First Birth | ||

| Nulliparous | 873 (33.8%) | 59.4 (57.3, 61.6) |

| <30 Years | 692 (26.8%) | 49.0 (47.1, 51.1) |

| 30+ Years | 1020 (39.5%) | 52.1 (50.4, 53.9) |

| p-value | <.001 | |

| Alcohol Use | ||

| No | 1278 (50.7%) | 51.3 (49.8, 52.9) |

| <= 1 drink/day | 954 (37.9%) | 55.3 (53.4, 57.2) |

| >= 2 drinks/day | 288 (11.4%) | 57.8 (54.2, 61.6) |

| p-value | <.001 | |

| Previous Biopsies | ||

| 0 | 2044 (79.3%) | 51.8 (50.5, 53.0) |

| 1 | 351 (13.6%) | 59.2 (55.9, 62.6) |

| 2+ | 183 (7.1%) | 65.0 (60.0, 70.3) |

| p-value | <.001 | |

Differences in mean dense volume by covariates estimated by linear regression adjusted for age. Dense volume analyzed on log scale and back-transformed for presentation.

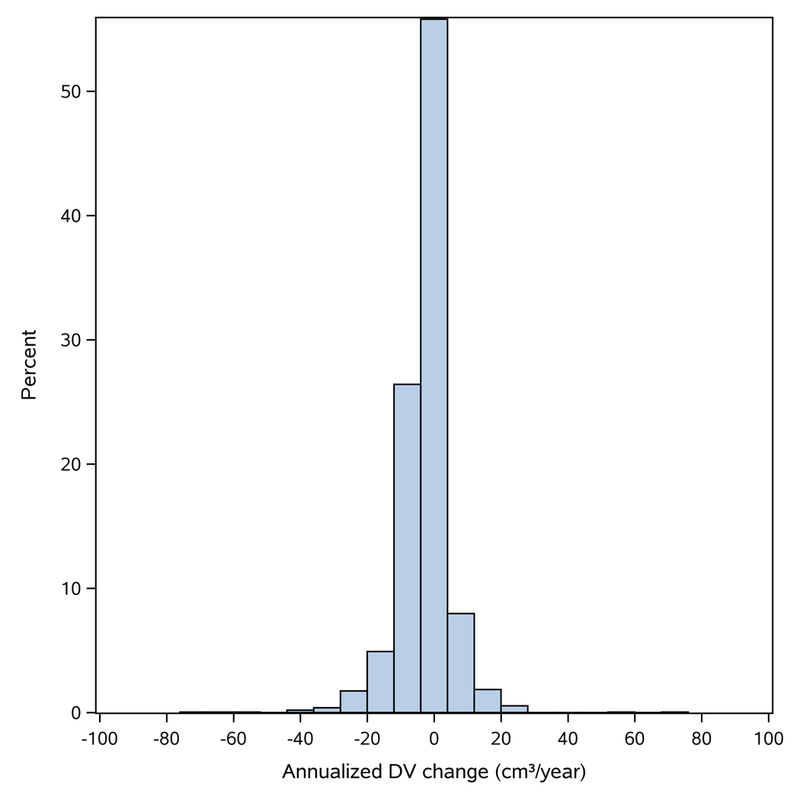

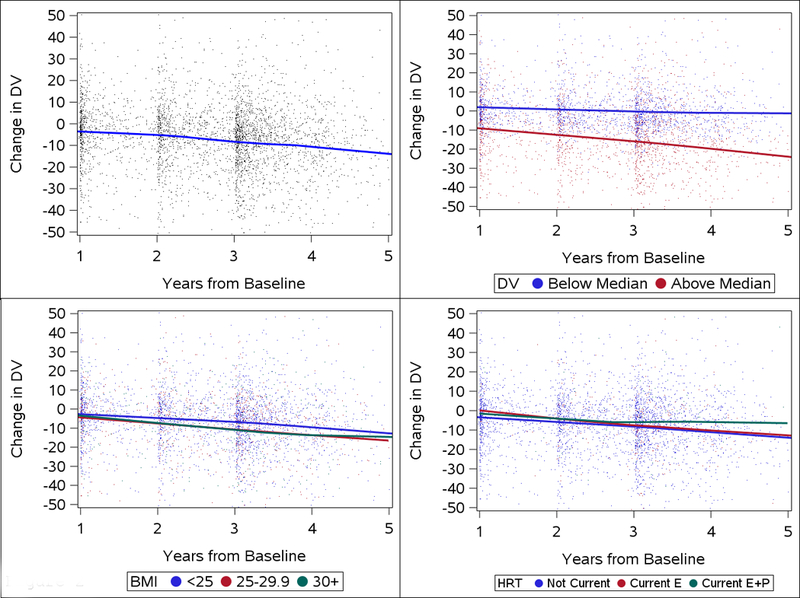

The distribution of changes in DV across the menopausal transition is displayed in Figure 1. The estimated decline in DV per year was 2.22 (95% CI: −2.74, −1.71) cm3 with a median time of 3.1 (IQR: 2.5–3.5) years from premenopausal to postmenopausal mammogram (Figure 2). The median DV at the premenopausal mammogram was 54.0 (IQR: 37.7–77.8) cm3, and women above the median DV at the premenopausal mammogram had greater declines across the menopausal transition, with average annualized declines of 3.46 (95% CI: −4.40, −2.73) cm3 compared with 0.97 (95% CI: −1.71, −0.22) in women at and below the median premenopausal DV, respectively (p-interaction<0.001). Among women with premenopausal DV above the median, 80% (1380/1732) experienced any decline and 32.9% of these women had a postmenopausal DV below the median. For women below the median DV, 58% (1022/1767) experienced any decline and 89.8% remained above the median DV at the postmenopausal mammogram (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1.

Histogram of annualized change in dense volume (DV). DV: dense volume.

Figure 2.

Annualized changes in dense volume (DV) across the menopausal transition according to premenopausal characteristics. Panel A: annualized changes in DV overall, Panel B: changes in DV according by premenopausal DV (above vs. below median DV), Panel C: changes in DV according to BMI; Panel D: changes by use of hormone replacement therapy. BMI: body mass index, HRT: hormone replacement therapy, Current E: current use of estrogen therapy, Current E+P: current use of combined estrogen & progesterone therapy.

The estimated decline in DV in overweight and obese women did not differ (−2.02, 95% CI: −2.65, −1.40 cm3 vs. −2.72, 95% CI: −3.84, −1.61 cm3) compared with normal weight women (−2.31, 95% CI: −3.84, −0.77 cm3) (p-interaction=0.56). Additionally, we found no differences in the rate of change in DV over time by race, parity, age at first birth, family history of breast cancer, or current alcohol use (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of covariates on change in dense breast volume across menopause. (N=2568 subjects with complete BMI data)

| Annualized Change in DV (95% CI)* cm3 | interaction p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Change | −2.22 (−2.74, −1.71) | NA |

| Premenopausal DV | ||

| Below median (<=54 cm3) | −0.97 (−1.71, −0.22) | <0.0001 |

| Above median (>54 cm3) | −3.46 (−4.40, −2.73) | |

| Premenopausal BMI | ||

| Normal (<25 kg/m2) | −2.31 (−3.84, −0.77) | 0.56 |

| Overweight (25–29 kg/m2) | −2.02 (−2.65, −1.40) | |

| Obese (>=30kg/m2) | −2.72 (−3.84, −1.61) | |

| Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy | ||

| Not Current | −2.14 (−2.69, −1.60) | 0.18 |

| Current | −3.58 (−5.57, −1.59) | |

| Unknown | −4.29 (−7.43, −1.15) | |

| Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy (among those known) | ||

| Not Current | −2.13 (−2.66, −1.59) | 0.64 |

| Current Estrogen | −3.16 (−5.60, −0.72) | |

| Current Estrogen + Progesterone | −3.09 (−6.68, 0.50) | |

| Family History of Breast cancer (among those known) | ||

| No family history | −2.25 (−2.83, −1.68) | 0.87 |

| Family History | −2.14 (−3.33, −0.95) | |

| Parity (among those known) | ||

| Nulliparous | −2.27 (−3.17, −1.37) | 0.88 |

| Parous | −2.18 (−2.81, −1.55) | |

| Age at First Birth (among those known) | ||

| Nulliparous | −2.27 (−3.16, −1.37) | 0.66 |

| <30 Years | −2.55 (−3.57, −1.53) | |

| 30+ Years | −1.96 (−2.76, −1.16) | |

| Race (among those known) | ||

| Caucasian | −2.42 (−3.12, −1.73) | 0.30 |

| Asian | −1.68 (−2.56, −0.80) | |

| Other | −2.91 (−4.59, −1.23) | |

| Alcohol Use (among those known) | ||

| None | −2.06 (−2.79, −1.33) | 0.12 |

| <=1/day | −2.79 (−3.63, −1.95) | |

| >=2 /day | −1.01 (−2.59, 0.57) | |

| Previous Biopsies | ||

| None | −2.16 (−2.73, −1.58) | 0.36 |

| <=1/day | −1.80 (−3.16, −0.43) | |

| >=2 /day | −3.55 (−5.60, −1.51) | |

Coefficients estimated by linear mixed models adjusted for age, BMI, log dense volume, BMI change across menopause, time from premenopausal mammogram and the interaction between dense volume and time from premenopausal mammogram.

The effect of each variable on change over time was estimated by fitting an interaction between time (years) and the premenopausal covariate of interest; p-values reflect overall interaction for each covariate.

Use of postmenopausal HT during the menopausal transition trended towards larger declines in DV per year compared with non-users, with women on HT on average having declines of 3.58 cm3 compared with 2.14 cm3 in non-users, though this difference was not significant (p=0.18). Further breakdown of HT use by formulation showed no significant differences between non-users (−2.13 cm3), estrogen-only users (−3.16 cm3), and users of estrogen & progestin combination therapy (−3.09 cm3)(p-interaction=0.64).

Results from models examining change in DV relative to baseline DV were broadly consistent with absolute change models, though the difference in change between baseline DV below compared with above the median was no longer statistically significant (p=0.22, Table 4).

Table 4.

Effect of covariates on percent change in dense breast volume across menopause. (N=2568 subjects with complete BMI data)

| Annualized % Change in DV (95% CI)* cm3 | interaction p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Change | −2.96 (−3.84, −2.08) | NA |

| Premenopausal DV | ||

| Below median (<=54 cm3) | −2.40 (−3.66, −1.15) | 0.22 |

| Above median (>54 cm3) | −3.52 (−4.77, −2.26) | |

| Premenopausal BMI | ||

| Normal (<25 kg/m2) | −1.68 (−4.30, 0.94) | 0.57 |

| Overweight (25–29 kg/m2) | −2.98 (−4.05, −1.90) | |

| Obese (>=30kg/m2) | −3.41 (−5.32, −1.49) | |

| Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy | ||

| Not Current | −3.01 (−3.95, −2.08) | 0.42 |

| Current | −4.92 (−8.28, −1.56) | |

| Unknown | −1.11 (−6.44, 4.21) | |

| Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy (among those known) | ||

| Not Current | −2.99 (−3.93, −2.06) | 0.71 |

| Current Estrogen | −4.76 (−8.92, −0.59) | |

| Current Estrogen + Progesterone | −2.43 (−8.51, 3.65) | |

| Family History of Breast cancer (among those known) | ||

| No family history | −3.03 (−4.01, −2.05) | 0.86 |

| Family History | −2.82 (−4.86, −0.78) | |

| Parity (among those known) | ||

| Nulliparous | −3.54 (−5.08, −2.01) | 0.35 |

| Parous | −2.64 (−3.72, −1.56) | |

| Age at First Birth (among those known) | ||

| Nulliparous | −3.54 (−5.08, −2.01) | 0.37 |

| <30 Years | −3.37 (−5.12, −1.62) | |

| 30+ Years | −2.20 (−3.56, −0.83) | |

| Race (among those known) | ||

| Caucasian | −3.23 (−4.42, −2.04) | 0.64 |

| Asian | −2.38 (−3.89, −0.87) | |

| Other | −3.50 (−6.37, −0.63) | |

| Alcohol Use (among those known) | ||

| None | −3.08 (−4.33, −1.84) | 0.11 |

| <=1/day | −3.58 (−5.01, −2.15) | |

| >=2 /day | −0.33 (−3.03, 2.38) | |

| Previous Biopsies | ||

| 0 | −2.86 (−3.85, −1.87) | 0.35 |

| 1 | −1.64 (−3.97, 0.70) | |

| 2+ | −6.23 (−9.73, −2.73) | |

Coefficients estimated by linear mixed models adjusted for age, BMI, log dense volume, BMI change across menopause, time from premenopausal mammogram and the interaction between dense volume and time from premenopausal mammogram.

The effect of each variable on change over time was estimated by fitting an interaction between time (years) and the premenopausal covariate of interest; p-values reflect overall interaction for each covariate.

Discussion

This longitudinal analysis of dense breast volume across the menopausal transition found a decline in DV of 2.2 cm3 per year across the menopausal transition. We found that premenopausal DV was a strong predictor of greater annualized declines in DV and that other risk factors, while strongly affecting premenopausal DV, had no significant effect on annualized changes in DV.

Our finding of a decline of 2.2 cm3 per year across the menopausal transition is broadly consistent with the annualized decline in dense breast area estimated by Boyd et al. of 6.8 cm2 in healthy women across 5 years during the menopausal transition (~1.36 cm2 per year).4 No studies, to our knowledge, have serial measures of volumetric breast density across the menopause, preventing direct comparisons of our findings. However, our own recent study found annualized declines of 0.28 cm3 in premenopausal women and 0.82 cm3 in postmenopausal women, unselected for proximity to the menopausal transition.16 The mean decline in our study is significantly greater per year during the menopausal transition, which is consistent with longitudinal research using area-based measures that suggest the greatest annualized reductions occur during the peri-menopausal years.7

Consistent with previous research using area-based density assessment, we found that higher premenopausal dense volume is a predictor of greater annualized declines in dense volume,4,5,7,8 and that race/ethnicity, family history of breast cancer, parity, age at first birth and alcohol use at the premenopausal mammogram did not significantly modify longitudinal changes.5,7,8 In analyses modeling change in dense volume as a percent change relative to premenopausal dense volume, we found similar results, though differences by initial DV were not significant. In both absolute and relative models of change, we adjusted for baseline density which is strongly affected by demographic characteristics and premenopausal risk factors, therefore it is possible that these factors have no effect on change in breast density aside from their effect on the premenopausal density. Interestingly, we found that alcohol had a strong effect on premenopausal DV, showing an increasing DV with increasing levels of alcohol use, though previous literature using area-based density has been mixed.18–20

We found no differences in reduction in DV over time by BMI. Some,5,7 but not all,8,9 longitudinal studies using area-based density assessment have found attenuated reductions over time in overweight and obese women, though all examined percent density, while we examine absolute dense volume. BMI is strongly inversely associated with area-based percent density, therefore it is possible that previous research found attenuated declines in overweight and obese women because the premenopausal breast density in these women was lower, thus allowing for relatively smaller changes over time.5 In our study, overweight and obese women had the highest premenopausal dense volume, therefore we would expect these women to experience greater reductions in dense volume over time. However, once adjusting for premenopausal dense volume, we found no additional effect of premenopausal BMI to slow declines in density. While the focus of our study was to identify premenopausal predictors of decline in DV, it is probable that changes in BMI over time are more relevant for influencing change in DV. One study using volumetric measurement found that reductions in BMI were associated with subsequent decreases in DV.21

Postmenopausal HT use is associated with increased breast density in cross-sectional studies, and has been associated with attenuated declines or increases over time and across the menopausal transition.13,22 Our findings that postmenopausal HT had no significant effect on changes in DV were unexpected, particularly the finding of no distinction between formulations of HT, which have shown important differences with respect to breast density in other studies.13,23,24 Maskarinec et al.5 reported that combined HT users had attenuated declines in area-based percent density that were 3.3% less than declines in non-users, though declines in users of estrogen-only HT were only 1.6% less than declines in non-users, per decade of follow-up. Based on previous literature, we would expect that women on HT in perimenopause or menopause would increase, maintain, or at least experience attenuated reductions in breast density relative to non-users. However the effects on breast density are likely dependent on duration of use, 13,25 which was not available in our analysis. It is possible that newer formulations of HT at lower doses have smaller effects of breast density, or that changes are less apparent when using volumetric assessment. Future research is needed to further examine this finding.

The menopausal transition is typically characterized by decreases in dense tissue, but also weight gain, which can increase both non-dense and total breast volume. For this reason, we focused our primary analysis on DV, consistent with the hypothesis that the absolute dense tissue is reflective of the number of cells at risk of carcinogenesis, thus potentially serving as a better indicator of breast cancer risk compared to percent measures which are confounded by body size.10 Furthermore, longitudinal assessment of changes in DV may be less influenced by mammography acquisition features, such as compressed breast thickness, which is known to be highly correlated with baseline factors such as BMI. Thus, this correlation may potentially bias estimates of factors that influence changes in these measures over time. We include volumetric percent density changes in a supplementary analysis, as it is frequently used in clinical and research settings, though a fuller assessment of how acquisition parameters affects changes in different phenotypes of volumetric breast density over time is warranted.

Longitudinal changes in qualitative and area-based breast density have consistently been associated with breast cancer risk, with the greatest changes in breast density corresponding to the largest differences in risk.8,9,14,25,26 Furthermore, Kerlikowske et al. demonstrated that the use of multiple longitudinal measures of breast density improved clinical risk stratification for breast cancer.27 This suggests that longitudinal trajectories of breast density may be a more relevant indicator of changes in breast cancer risk than measurement at a single timepoint. As women tend to experience accelerated changes in breast density over the menopause,4,5,7–9 these changes may be indicators of postmenopausal breast cancer risk, thus the ability to capture longitudinal trajectories across menopause may offer enhanced risk stratification in the clinical setting. However, to date, studies of change in breast density and changes in risk have used two-dimensional breast density. Given the potential for use in clinical decision-making, future research is needed to identify what magnitude of change in volumetric breast density is meaningful to reduce breast cancer risk.

A major strength of our study is the prospective collection of risk factor data and multiple mammograms in healthy women across the menopausal transition, and the use of automated volumetric breast density measurement. Our study has several important limitations, including the use of self-reported menopause status, which is subject to measurement error. Errors in self-report are unlikely to be dependent on premenopausal risk factors; however, these non-differential errors may have biased the effects of risk factors on changes in DV towards the null. Postmenopausal HT use and formulation were self-reported, and lack of duration information makes it difficult to determine if the lack of effect of DV over time is real, or if the short average duration of use or newer lower-dose formulations account for the lack of an effect of HT on changes over time.

In summary, we found that the mean change in DV over an average of three years across the menopausal transition was 2.2 cm3, and that women with higher premenopausal DV experienced the greatest declines in DV over this period. Future research is warranted to determine what magnitude of change and timing of these changes in volumetric breast density is relevant for breast cancer risk.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the women within the San Francisco Mammography Registry (SFMR) who enabled this research. This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute (R01 CA177150, P01 CA154292, R01 CA207084).

Footnotes

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Pettersson A, Graff RE, Ursin G, et al. Mammographic Density Phenotypes and Risk of Breast Cancer: A Meta-analysis. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst 2014;106(5):dju078–dju078. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCormack VA, dos Santos Silva I. Breast density and parenchymal patterns as markers of breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2006;15(6):1159–1169. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huo CW, Chew GL, Britt KL, et al. Mammographic density - A review on the current understanding of its association with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2014;144(3):479–502. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2901-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyd N, Martin L, Stone J, Little L, Minkin S, Yaffe M. A longitudinal study of the effects of menopause on mammographic features. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2002;11:1048–1053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maskarinec G, Pagano I, Lurie G, Kolonel LN. A longitudinal investigation of mammographic density: the multiethnic cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2006;15(4):732–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pike MC, Krailo MD, Henderson BE, Casagrande JT, Hoel DG. “Hormonal” risk factors, “breast tissue age” and the age-incidence of breast cancer. Nature 1983;303(5920):767–770. doi: 10.1038/303767a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kelemen L, Pankratz V, Sellers TA, et al. Age-specific trends in mammographic density: the Minnesota Breast Cancer Family Study. Am J Epidemiol 2008;167(1476–6256 (Electronic)):1027–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Busana MC, De Stavola BL, Sovio U, et al. Assessing within-woman changes in mammographic density: a comparison of fully versus semi-automated area-based approaches. Cancer Causes Control 2016;27(4):481–491. doi: 10.1007/s10552-016-0722-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lokate M, Stellato R, Veldhuis WB, Peeters PHM, van Gils CH, van de Velde CJ. Age-related changes in mammographic density and breast cancer risk. Am J Epidemiol 2013;178(1):101–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haars G, Van Noord PAH, Van Gils CH, Grobbee DE, Peeters PHM. Measurements of breast density: No ratio for a ratio. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2005;14(11 I):2634–2640. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hjerkind KV, Ellingjord-dale M, Johansson AL V, et al. Volumetric Mammographic Density, Age-Related Decline, and Breast Cancer Risk Factors in a National Breast Cancer Screening Program 2018;(11):1065–1075. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burton A, Maskarinec G, Perez-Gomez B, et al. Mammographic density and ageing: A collaborative pooled analysis of cross-sectional data from 22 countries worldwide. PLoS Med 2017;14(6):1–20. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Byrne C, Ursin G, Martin CF, et al. Mammographic Density Change With Estrogen and Progestin Therapy and Breast Cancer Risk. J Natl Cancer Inst 2017;109(9):1–7. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djx001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kerlikowske K, Ichikawa L, Miglioretti D, et al. Longitudinal measurement of clinical mammographic breast density to improve estimation of breast cancer risk. JNCI 2007;99(5):386–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Gils C, Hendriks J, Holland R, et al. Changes in mammographic breast density and concomitant changes in breast cancer risk. Eur J Cancer Prev 1999;8(6):509–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Engmann NJ, Scott C, Jensen MR, et al. Longitudinal changes in volumetric breast density with tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev Prev February 2017. http://cebp.aacrjournals.org/content/early/2017/02/01/1055-9965.EPI-16-0882.abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Volpara Solutions from Matakina Technology. Volpara Density User Manual Version 1.5.11 Wellington, New Zealand; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDonald JA, Michels KB, Cohn BA, Flom JD, Tehranifar P, Terry MB. Alcohol intake from early adulthood to midlife and mammographic density. Cancer Causes Control 2016;27(4):493–502. doi: 10.1007/s10552-016-0723-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vachon CM, Sellers TA, Janney CA, et al. Alcohol intake in adolescence and mammographic density. Int J Cancer 2005;117(5):837–841. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vachon CM, Kushi LH, Cerhan JR, Kuni CC, Sellers T a. Association of Diet and Mammographic Breast Density in the Minnesota Breast Cancer Family Cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2000;9(February):151–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hart V, Reeves KW, Sturgeon SR, et al. The effect of change in body mass index on volumetric measures of mammographic density. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2015;24(11):1724–1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greendale GA, Reboussin BA, Slone S, Wasilauskas C, Pike MC, Ursin G. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and change in mammographic density. J Natl Cancer Inst 2003;95(1):30–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McTiernan A, Martin C, Peck J, et al. Estrogen-plus-progestin use and mammographic density in postmenopausal women: Women’s Health Initiative randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005;97(1460–2105 (Electronic)):1366–1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greendale G, Reboussin B, Sie A, et al. Effects of estrogen and estrogen-progestin on mammographic parenchymal density. Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions (PEPI) Investigators. Ann Intern Med 1999;130(4):262–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cuzick J, Warwick J, Pinney E, et al. Tamoxifen-induced reduction in mammographic density and breast cancer risk reduction: a nested case-control study. JNCI 2011;103:744–752. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Work ME, Reimers LL, Quante AS, Crew KD, Whiffen A, Terry MB. Changes in mammographic density over time in breast cancer cases and women at high risk for breast cancer. Int J Cancer 2014;135(7):1740–1744. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kerlikowske K, Gard CC, Sprague BL, Tice JA, Miglioretti DL. One versus two breast density measures to predict 5- and 10-year breast cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2015;24(6):889–897. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.