Abstract

Chemotherapy and radiation (C,R) are more effective in wild type (WT) p53 tumors due to p53 activation. This is one rationale for developing drugs that reactivate mutant p53 to synergize with (C,R). Zinc metallochaperones (ZMCs) are a new class of mutant p53 reactivators that restore WT structure and function to zinc-deficient p53 mutants. We hypothesized that the thiosemicarbazone, ZMC1, would synergize with (C,R). Surprisingly, this was not found. We explored the mechanism of this and found the ROS activity of ZMC1 negates the signal on p53 that is generated with (C,R). We hypothesized that a zinc scaffold generating less ROS would synergize with (C,R). The ROS effect of ZMC1 is generated by its chelation of redox active copper. ZMC1 copper binding (KCu) studies reveal its affinity for copper is ~108 greater than Zn2+. We identified an alternative zinc scaffold (NTA) and synthesized derivatives to improve cell permeability. These compounds bind zinc in the same range as ZMC1 but bound copper much less avidly (106 – 107-fold lower) and induced less ROS. These compounds were synergistic with C and R by inducing p53 signaling events on mutant p53. We explored other combinations with ZMC1 based on its mechanism of action and demonstrate that ZMC1 is synergistic with MDM2 antagonists, BCL2 antagonists and molecules that deplete cellular reducing agents. We have identified an optimal Cu2+:Zn2+ binding ratio to facilitate development of ZMC’s as (C,R) sensitizers. While ZMC1 is not synergistic with (C,R), it is synergistic with a number of other targeted agents.

Keywords: Zinc metallochaperones, zinc-binding deficient p53 mutants, copper binding compounds, reactive oxygen species, mutant p53 targeted therapy

Introduction

Since the early 1990’s, we have known that in addition to its role as a potent tumor suppressor, p53 also plays a role in response to therapy in cancers treated with both cytotoxic chemotherapy and radiation. Both chemotherapy and radiation activate wild type p53 resulting in a p53 mediated cell death response that synergizes with the therapy. This is not seen in tumors that are either missense mutant or null for p53 (1,2). Thus it became known that the p53 status (wild type (WT) vs mutant) could serve as a mechanism of sensitivity and resistance to therapies. The mechanism responsible for this activity in large measure is attributed to the DNA damage response pathway signaling on p53 through activation of kinases such as ATM and ATR. These kinases induce post-translational modifications (PTMs) that stabilize the protein and augment recruitment of the transcriptional machinery and in many cases induce an apoptotic program (3). The effect of p53’s response to therapy has also served as the rationale for combining drugs that either activate WT p53 (i.e. MDM2 inhibitors, such as Nutlin) or restore WT structure/function to mutant p53 (so-called mutant reactivation) with chemotherapy and radiation to increase efficacy (4–6).

We recently discovered a new class of mutant p53 reactivators called zinc metallochaperones (ZMCs) that reactivate specific missense p53 mutants which share the common defect of impaired zinc binding (7,8). This is best exemplified by p53R175H, the most common missense mutant in cancer, where the substitution of a histidine for an arginine at codon 175 causes steric hindrance close enough in proximity to the zinc coordinating site to weaken the binding affinity for zinc approximately 1000 fold such that at physiologic concentrations of zinc, the p53R175H is in its apo zinc free state (9). ZMCs restore wild type structure and function using a novel mechanism that involves binding zinc in the extracellular space in a 2:1 molar ratio which allows the charge-neutral complex to passively diffuse through the cell membrane as a zinc ionophore, thereby raising intracellular zinc concentrations high enough to overcome the binding affinity defect in the mutant protein (7,9). With zinc bound in its native ligation site, the protein folds into its WT conformation.

ZMC’s must bind zinc with an intermediate affinity that allows them to both bind and donate zinc in the cell (10). We previously measured the Zn2+ dissociation constant for the lead compound ZMC1 (KZnZMC1) and found this value to be 20–30 nM (9). ZMC1 belongs to the thiosemicarbazone class of metal ion chelators that bind Zn2+, Fe2+, Cu2+, Co2+ and Mn2+. We have recently shown that two other thiosemicarbazones (ZMC2, ZMC3) bind zinc with similar affinity as ZMC1 (KZnZMC2 = 27 nM, KZnZMC3 = 81 nM) and also function as mutant p53 reactivators. However, not all thiosemicarbazones function as ZMCs. Another thiosemicarbazone in clinical development (Triapine, 3-AP) binds zinc too weakly to transport it from the extracellular space into the cell, and is correspondingly non-functional (KZnTriapine > 1 μM) (11).

Another key component of the ZMC1 mechanism relates to p53 PTMs. PTMs are a well-known mechanism for regulating p53 signaling (12,13). ZMCs generate intracellular ROS, through chelation of redox active metals such as Fe2+ and Cu2+. These ROS levels activate a damage response pathway that induces PTMs on the refolded p53 that enhance its function as a transcription factor and drive an apoptotic program (9). In support of this, cellular reducing agents such as N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC) or glutathione (GSH) inhibit ZMC1-induced apoptosis by quenching the ROS signal, leaving ZMC1 capable of inducing a wild type conformation change on mutant p53, but unable to transcriptionally activate an apoptotic program (due to a lack of PTMs) (9). While these ROS levels play an integral role in the mechanism of ZMC1, they also function as a source of off-target activity that can serve as a source of toxicity.

ZMC1 potently inhibits xenograft tumor growth and improves survival in murine genetically engineered cancer models with zinc-deficient TP53 mutations through a p53 mediated apoptotic mechanism while having no such effect in tumors that harbor non-zinc deficient TP53 mutations (8,14). Given this unique mechanism, we sought to determine whether the thiosemicarbazone based ZMCs (i.e. ZMC1) can synergize with cytotoxic chemotherapy or radiation. Using non-thiosemicarbazone based zinc scaffolds, we sought to determine if we could potentially separate the p53-refolding activity from the ROS generating activity by selecting an optimal copper to zinc binding ratio. These new ZMCs would still function to refold mutant p53, but by generating less ROS they might function as chemotherapy and radiation sensitizers. Lastly, we sought to use the knowledge of the ZMC mechanism to rationally select targeted agents that might synergize with ZMC therapy.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines, culture conditions and chemicals

TOV112D, H1299, Detroit 562, H460-shCTL and H460-shp53 were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS. TOV112D, H1299 and Detroit 562 were purchased from ATCC. H460-shCTL and H460-shp53 were gifts from Dr. Zhaohui Feng (15). Cell lines were authenticated by examination of morphology, genotyping by PCR and growth characteristics. The GSH, Cisplatin, Irinotecan, 5-Fluorouracil, Etoposide, Adriamycin, β-Lapachone (β-Lap), 6-Amino Nicotinamide (6-AN) and Thionicotinamide (ThioNa) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Nutlin 3a and ABT-199 were purchased from SelleckChem (Houston, TX).

Cell growth inhibition assay

Cell growth inhibition assay was performed by MTS (Promega, WI), Calcein AM assay (Trevigen, MD), Vi-CELL Trypan Blue staining (Beckman Coulter, IN) or Guava ViaCount (Millipore, MA). The procedures are described in Supplementary Information. Statistical significance of the data, obtained from three independent experiments, each with triplicates, was calculated with Student’s t-test.

Combination treatment and synergy study

EC50 values were calculated from the single compound treatment assays, measured by MTS assay or Calcein AM assay. Drugs in combination assays were dosed at ratios indicated in each experiment. The CI was assessed by the Chou-Talalay Method (16,17) for synergy determination with CalcuSyn software (Biosoft, Cambridge, United Kingdom). CI< 1 =synergy; CI=1, additive; CI>1= antagonism.

Radiation treatment

The TOV112D cells (100,000 cells/well, in 1 mL culture) were cultured in 12-well plates in duplicate. Cells reached 50 – 60% confluence on the second day when cells were treated with indicated treatments and radiation doses. Cells incubated for three days, after which cell viability was measured by Vi-CELL Cell Counter using trypan blue staining.

Immunofluorescent staining

Immunofluorescent staining was performed as described previously (14). The details are in Supplementary Information.

Gene expression (quantitative RT-PCR) and Western blot

The procedures were performed as described previously (14). RNA was extracted from the cells using RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and the gene expression level was measured by quantitative RT-PCR using TaqMan gene expression assays (Life Technologies/Applied BioSystems). The actin and p53 (DO-1) antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Phospho-p53 (S15), Phospho-p53 (S46), and p21 antibodies were from Cell Signaling. Acetylated-p53 (K120) antibody was from Millipore.

Transfection of siRNA

The control and p53 siRNA were purchased from Dharmacon. Transfection was performed using RNAiMAX (Invitrogen), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The efficiency of the knockdown was measured by Western blot.

Synthesis of ZMC1, 2,2’-((2-Ethoxy-2-oxoethyl)azanediyl)diacetic acid (NTA-MEE) and NTA-DEE

The synthesis of ZMC1 (Supplementary Fig. S1), MEE and DEE is detailed in Supplementary Information.

KZn and KCu measurements

The competition assays used to measure metal dissociation constants are detailed in Supplementary Information.

Oxidative stress detection

ROS signal was measured using CellROX Green Regent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA) following manufacturer’s protocol. The p53-null cells were used to minimize any p53 effects.

Colony formation assays

The procedure for long-term viability was performed as described previously (18) and detailed in Supplementary Information

Mouse experiments

Mice are housed and treated according to guidelines and all the mouse experiments are done with the approval of Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Rutgers University. The nude mice NCR nu/nu were purchased from Taconic (NY). Xenograft tumor assays were derived from the human tumor cell line, TOV112D (5 × 106 cells/tumor site/mouse). Tumor dimensions were measured every day and the volumes were calculated by length (L) and width (W) by using the formula: volume = L × W2 × π / 6. Tumors (8–12 per group) were allowed to grow to 50 mm3 prior to daily administration of ZMC1 at 2.5 mg/kg or Nutlin 3a at 5 mg/kg by IP administration. ABT-199 (100 mg/ml) was administrated by oral gavage daily.

Statistics

The data were analyzed by Student’s t-test with an overall significance level of p<0.05. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Results

ZMC1 in combination with cytotoxic chemotherapy or gamma radiation fails to demonstrate synergy

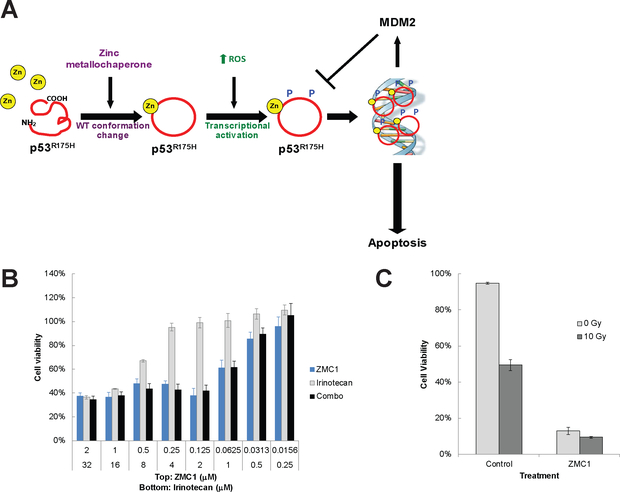

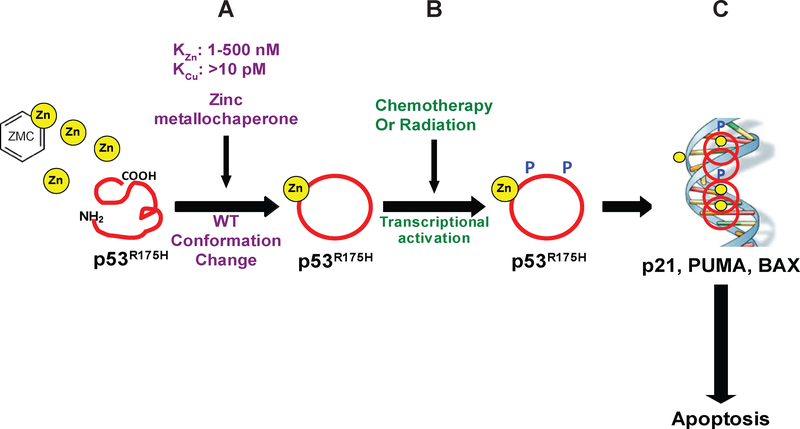

The unique two part mechanism of ZMC1 has been illustrated in which the molecule induces a WT conformation change by restoring zinc binding in the p53R175H (Fig. 1A). As a result of an increase in cellular ROS levels, this newly conformed p53 then undergoes post-translational modifications (PTMs) that enhance its WT transcriptional function and induce an apoptotic program (9).

Figure 1.

Combination treatment of ZMC1 and cytotoxic chemotherapy or radiation does not display synergy. (A) Schematic representation of the mechanisms of ZMC1 reactivationg mutant p53R175H. (B) TOV112D (p53R175H) cells were treated with Irinotecan, ZMC1, or a combination of both for 72 hours, after which cell viability was measured by MTS assay. (C) TOV112D cells were treated with γ-irradiation (10 Gy), ZMC1 (2 μM), or a combination of both for 72 hours, after which viability was measured by Vi-CELL Trypan Blue staining.

Given that both cytotoxic chemotherapy and ionizing radiation activate wild type p53, we hypothesized that both would synergize with ZMC’s. To test this, we treated the human ovarian carcinoma cells TOV112D (p53R175H) with ZMC1 combined with Cisplatin, Irinotecan, 5-Fluorouracil, Etoposide, or Adriamycin. We first measured EC50s of each compound alone and then tested the combinatorial treatments. We calculated CI values by CalcuSyn software. Surprisingly, ZMC1 was not synergistic with any of the cytotoxic chemotherapy agents (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Table S1). The combination of ZMC1 and these compounds leads to primarily additive or antagonistic effects. Indeed, when cells were treated with low doses of Adriamycin or Cisplatin concurrently with ZMC1, there was less cell death than in cells treated with ZMC1 alone (Supplementary Fig. S2A–B). Moreover, cells were not sensitized to the effects of high dose (1 μM) ZMC1 when treated with ionizing radiation (10 Gy) (Fig. 1C).

Synergy between ZMC1 and cytotoxic chemotherapy or radiation is observed when the ROS signal is quenched

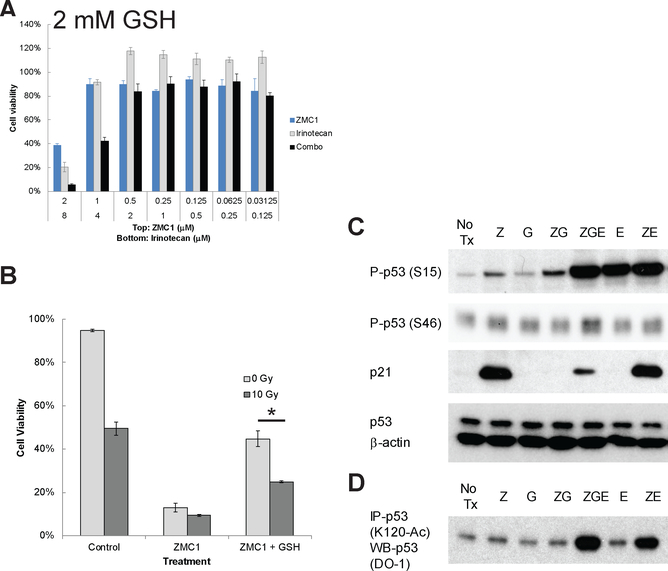

Given the role that ROS plays in the ZMC1 mechanism, we hypothesized that the explanation for the lack of synergy between ZMC1 and (C,R) could be attributed to this ROS activity. In essence, the signaling events that (C,R) would normally induce to activate p53 are already being stimulated by ZMC1. To test this, we attempted to quench the ROS signal generated by ZMC1 using GSH and then combined this with either cytotoxic chemotherapy or radiation. Indeed, when we pre-treated TOV112D cells with media containing GSH and then combined this with Cisplatin, Irinotecan or Etoposide in cell growth inhibition assays, we now observed synergy (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Table S2). Moreover, GSH pre-treatment also sensitized ZMC1 treated TOV112D cells to ionizing radiation (Fig. 2B). When we treated another p53R175H cell line (Detroit 562) with ZMC1 and irinotecan, we obtained similar results in that the treatment displayed synergy only in the presence of GSH. The CI value without GSH was 2.32 indicating antagonism, but was 0.87 in combination with 2 mM GSH indicating synergy (Supplementary Fig. S3 and Supplementary Table S3).

Figure 2.

Combination treatment of ZMC1 and cytotoxic chemotherapy or radiation in the presence of GSH displays increased synergy. (A) TOV112D cells were treated with Irinotecan, ZMC1, or a combination of both for 72 hours in the presence of 2 mM GSH, after which cell viability was measured via MTS assay. (B) TOV112D cells were treated with γ-irradiation (10 Gy), ZMC1 (2 μM), or a combination of both for 72 hours in the presence of 2 mM GSH, after which viability was measured by Vi-CELL Trypan Blue staining. * p value < 0.05. (C) Combination treatment of ZMC1 and DNA damaging reagent (Etoposide) in the presence of GSH recovers p53 transcription function as evidenced by p21 expression regulation. TOV112D cells were treated with the indicated compounds for 6 hours followed by analysis of cell lysates by Western Blot. The expression of p21 is up-regulated by ZMC1 treatment but attenuated with additional GSH. Etoposide treatment restored the p21 expression. Phospho-p53 (S15) and Phospho-p53 (S46) were also detected by Western blot after ZMC1 treatment but attenuated with additional GSH. Etoposide treatment restored the phosphorylation of the p53 protein. β-actin was used as internal control. (D) Immunoprecipitation of Acetylated p53 (K120). The p53 (K120) acetylation was up-regulated by ZMC1 treatment but attenuated with additional GSH. Concurrent Etoposide treatment increased the p53 (K120) acetylation. No Tx, no treatment; Z, ZMC1, 1 μM; G, GSH, 0.5 mM; E, Etoposide, 20 μM, ZG, ZMC1 and GSH; ZGE, ZMC1 and GSH and Etoposide; ZE, ZMC1 and Etoposide.

We have previously demonstrated that ZMC1-induced redox stress functions to induce wild type transcriptional function after the mutant p53 protein regains its wildtype-like structure through PTMs (S15, S46 phosphorylation, K120 acetylation) that typically drive a p53 mediated apoptotic program (9). This conclusion was made by showing that these PTM’s as well as the WT transcriptional activity of ZMC1 could be silenced by the co-administration of a reducing agent such as NAC (9). In light of this, we found that similar to NAC, these p53 PTMs were inhibited by GSH and consequently wild type transcriptional function (p21 expression) was as well (Fig. 2C–D). This signal on p53 could then be restored by treatment with the DNA damaging agent Etoposide in the presence of GSH (Fig. 2C–D). Note the increase in S15 and S46 phosphorylation on p53 with the addition of Etoposide to GSH with the concomitant increase in p21 expression. Also note the lack of p21 in the control with Etoposide alone (with no ZMC1) indicating that the increase in p21 by Etoposide is p53 mediated. We also tested another combination of ZMC1 with Irinotecan in the presence of GSH and observed similar results (Suppl. Fig. S4).

To further validate these PTM and p21 expression changes were p53 dependent, we performed similar experiments using the TOV112D cells in the presence of a p53 siRNA, as well as a p53 WT cell line (H460) in the presence and absence of the p53 shRNA. In the presence of the p53 siRNA, we observed none of the increases in either S15 phosphorylation or p21 levels with any of the treatments in the TOV112D cells (compare Fig. 2C vs. Supplementary. Fig. S5A). We have previously shown in H460 cells that ZMC1 does not activate WT p53 at doses in which it reactivates the p53R175H (14). This is most likely due to the large differences in levels of p53 between the mutant and WT cells. Consistent with those results, we found that ZMC1 did not increase S15 phosphorylation nor p21 levels; however, etoposide alone induced both and this was not modulated by the addition of ZMC1 or GSH (Supplementary. Fig. S5B–C). This concludes that the ROS signal generated by ZMC1 is enough to stifle synergy with cytotoxic chemotherapy or radiation and that synergy can be produced through a WT p53 mediated activation by quenching the ROS and adding an agent that is known to activate WT p53. Thus the ROS activity of ZMC1 is like a “double edged sword” in that it serves an advantage by making the molecule active as a single agent, but also serves as a disadvantage by inhibiting its ability to synergize with (C,R).

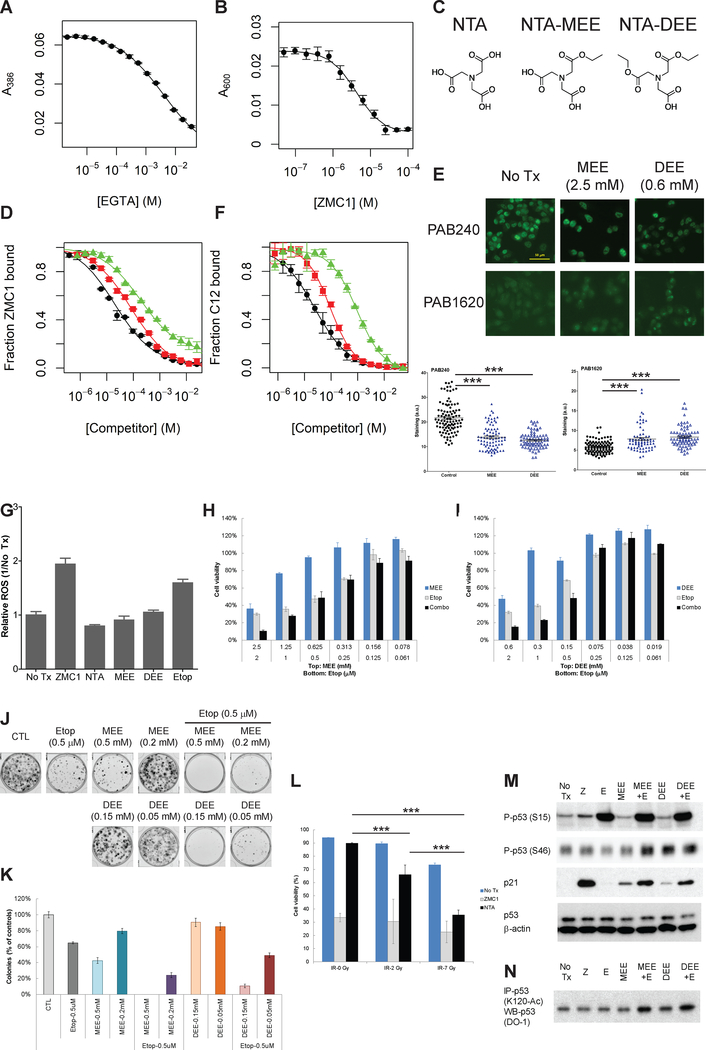

Zinc Metallochaperones with diminshed copper binding synergize with cytotoxic chemotherapy and radiation

If the ROS activity of ZMC1 serves as a disadvantage in combining it with (C,R), then it follows that identifying a ZMC that is capable of inducing a WT conformation change with a marked reduction in ROS activity might possibly synergize with (C,R). This would require an understanding of the source of ROS in ZMC1. Recently ZMC1 (NSC319726) was investigated for its picomolar potency in patient derived glioblastoma cell lines that was found to be due increased ROS activity secondary to its copper binding activity (19). Copper, like iron is a redox active transition metal, whereas zinc is not. We measured the Cu2+ dissociation constant of ZMC1 (KCuZMC1) by means of two independent assays using EGTA or the metal indicator Zincon (20) as competitors for copper binding (Fig. 3A and B, Supplementary Fig. S6). The calculated KCuZMC1 values of 7.4 × 10−17 M (EGTA competition) and 2.1 × 10−16 M (Zincon competition) reveal that ZMC1 binds Cu2+ ~108-fold more tightly than Zn2+ (KZnZMC1 = 3 × 10−9 M) (9). We hypothesized that identifying a metal-binding scaffold that bound zinc in the range of ZMC1 (to accomplish the conformation change) but bound copper much less avidly might be synergistic with cytotoxic chemotherapy and radiation. We previously demonstrated that Nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) is able to restore a WT-like conformation in mutant p53 as it binds Zn2+ with an appropriate affinity (KZnNTA = 17 nM) to function as a zinc metallochaperone (9). However, the NTA·Zn2+ complex has an overall anionic character and exhibits poor cell permeability, limiting its utility as a ZMC. In order to improve the cell permeability of NTA, we replaced the ionizable acids in NTA with non-ionizable esters and synthesized the monoethyl ester (MEE) and diethyl ester (DEE) versions of NTA to be tested in cell culture (Fig. 3C). We anticipated that each esterification step would diminish the molecule’s zinc binding affinity by occupying one of the zinc ligand sites. This indeed was evident when we determined the Zn2+ dissociation constants to be KZnNTA-MEE = 325 nM, and KZnNTA-DEE = 850 nM (Fig. 3D). While the addition of two ester groups to NTA-DEE significantly impaired zinc binding, we speculated that it might exhibit enhanced biological activity compared to NTA due to increased cellular bioavailability. Once NTA-DEE enters the cell, we reasoned that it could be sequentially hydrolyzed to NTA-MEE and then to NTA by the action of cellular esterases, which are known to act on small molecule esters (21).

Figure 3.

Combination treatment of p53-reactivating reagent (NTA-derivatives) and DNA damaging reagent (Etoposide) recovers p53 transcription. ZMC1 binds Cu2+ with KCuZMC1 values of (7.4 ± 0.31) x 10−17 M and (2.0 ± 0.37) x 10−16 M as determined by, respectively, EGTA competition assays (A) and Zincon competition assays (B). (C) Structures of NTA, NTA-MEE, and NTA-DEE. (D) NTA (black circles), NTA-MEE (red squares), and NTA-DEE (green triangles) bind to Zn2+ with KZnNTA = 17 nM (9), KZnNTA-MEE = (327 ± 36) nM, and KZnNTA-DEE = (850 ± 350) nM as determined by ZMC1 competition. (E) Immunocytochemistry fluorescent staining (IF) of the p53 protein from TOV112D cells after treatment of MEE (2.5 mM) or DEE (0.6 mM). The antibody PAB1620 recognizes WT conformation of p53. The Antibody PAB240 recognizes mutant conformation of p53. IF quantification was determined using ImageJ. *** p < 0.0001. (F) NTA (black circles), NTA-MEE (red squares), and NTA-DEE (green triangles) bind to Cu2+ with KCuNTA = 8.2 × 10−11 M (22), KCuNTA-MEE = (2.6 ± 0.98) x 10−10 M, and KCuNTA-DEE = (2.6 ± 0.92) x 10−9 M as determined by C12 competition assay. (G) Reactive oxygen species (ROS) was measured by Flow cytometry using CellRox-green reagent (Invitrogen) in H1299 (p53 null) cells after treatment with the indicated compounds. NTA and its derivatives did not induce ROS. The concentrations of the test are sublethal doses of 0.75 μM. (H) TOV112D cells were treated with MEE, Etoposide, or a combination at the indicated concentrations for 72 hours, followed by cell viability measurement by MTS assay. (I) TOV112D cells were treated with DEE, Etoposide, or a combination at the indicated concentrations for 72 hours, followed by cell viability measurement by MTS assay. (J) Long term effect of combination of Etoposide and MEE or DEE is evaluated by clonogenic assay. The cells were treated with vehicle control (CTL), Etoposide (Etop, 0.5 μM), MEE (0.5 mM or 0.2 mM), or DEE (0.15 mM or 0.05 mM) or combination. The quantification of colonies is shown in (K). The p value of Etoposide vs Etop + DEE (0.05 mM) is 0.0064. The p value of DEE (0.05 mM) vs. Etop + DEE (0.05 mM) is 0.0027. All other Etoposide vs combinations and MEE or DEE alone vs combinations have p values <0.001. (L) TOV112D cells are treated with ZMC1 (1 μM) or NTA (5mM) and 6 hours later, IR (0 Gy, 2 Gy, 7 Gy) and then incubated for 3 days. The cell viability was measured by Guava ViaCount. Cells treated with NTA are sensitized to ionizing radiation, while cells treated with ZMC1 are not. (M) Combination treatment of MEE or DEE and DNA damaging reagent (Etoposide) induces p53 transcription function as evidenced by p21 expression regulation, comparable to ZMC1 treatment. TOV112D cells were treated with the indicated compounds for 6 hours followed by analysis of cell lysates by Western Blot. The expression of p21 was up-regulated by ZMC1, MEE, DEE or combination with Etoposide. Phospho-p53 (S15) and Phospho-p53 (S46) were also detected by Western blot after ZMC1, MEE, DEE and combination treatment. β-actin was used as internal control. (N) Immunoprecipitation of Acetyl p53 (K120). The p53 (K120) acetylation was up-regulated by MEE, DEE and combination treatment. No Tx, no treatment; Z, ZMC1, 1 μM; E, Etoposide, 20 μM; MEE, 2.5 mM; DEE, 0.6 mM; MEE + E, MEE and Etoposide; DEE + E, DEE and Etoposide.

We evaluated the ability of these molecules to function as zinc ionophores and restore wild type conformation to the p53R175H by immunocytochemistry using p53 conformation specific antibodies as previously shown (9,14). Similar to NTA (5 mM) (9), NTA-MEE (2.5 mM) and NTA-DEE (0.6 mM) induced the WT-like conformation change of mutant p53R175H as evidenced by a significant reduction in fluorescence by the mutant specific antibody (PAB240) and increase in the WT specific antibody (PAB1620) (Fig. 3E). As expected, the concentrations of NTA-MEE and NTA-DEE required to produce this function were less than that of NTA, consistent with esterification improving cell permeability. However, the fact that all three compounds still required millimolar concentrations to change the p53 immunophenotype suggests that their ionophoric activity remains poor. Using a competition assay with compound C12, a novel chelator that binds Cu2+ with much lower affinity than ZMC1 and Zincon (KCuC12 = 1.3 × 10−11 M; Supplementary Fig. S7), we determined the copper dissociation constants of the NTA compounds to be KCuNTA-MEE = 2.6 × 10−10 M and KCuNTA-DEE = 2.6 × 10−9 M (Fig. 3F). KCuNTA-MEE and KCuNTA-DEE are higher than KCuNTA (8.2 × 10−11 M; (22)) by factors of 3.2 and 32, respectively, indicating that esterification of NTA weakens its interaction with Cu2+ as well as Zn2+. The most significant result is that, while the NTA compounds bind Zn2+ with affinities equal to or only moderately lower than that of ZMC1, the NTA compounds bind Cu2+ much more weakly than ZMC1 (106 – 107-fold). The net result is that the Cu2+:Zn2+ selectivity ratio is much higher for ZMC1 (108) than it is for NTA and its esters (10 – 103).

We then measured the ROS activity of these compounds using the CellROX Green fluorescent agent in p53 null cells treated with various compounds. We used p53 null cells to minimize any changes in ROS due to WT p53 activity. As might be expected from their weakened Cu2+ affinities, NTA, NTA-MEE and NTA-DEE did not induce ROS species like ZMC1 (Fig. 3G). Etoposide induced significant ROS levels similar to ZMC1.

Next, we performed combinatorial experiments with these compounds with Etoposide in TOV112D cells and indeed observed synergy (Fig. 3H–I and Supplementary Table S4). We also evaluated the synergy between MEE or DEE and Etoposide for a more durable effect using the clonogenic survival assay where cells were exposed to a lower dose of the combination of MEE/DEE plus Etoposide. Using a dose of combination that was also relatively insensitive alone, we observed a significant reduction in colonies with the combination (Fig. 3J–K). Moreover, we demonstrate that cells were sensitized to the effects of NTA but not ZMC1 when co-administered with ionizing radiation (Fig. 3L). To investigate the molecular mechanism of the action of this combination treatment, we examined p53 PTMs and p21 levels by western blot in TOV112D cells. We observed that MEE and DEE alone were capable of inducing some S15 and S46 phosphorylation and K120 acetylation (as well as increase in p21); however this was diminished in comparison to ZMC1 which is consistent with them producing less ROS than ZMC1 (Fig. 3M–N). When MEE and DEE were combined with Etoposide, these PTM’s were significantly increased as well as the levels of p21. Interestingly, Etoposide alone did induce an increase in the PTM’s we examined indicating that these PTM’s can occur on mutant p53 structure. To provide further evidence that the PTM and p21 responses are p53 dependent, we performed the same experiment in the presence of a p53 siRNA and found no such induction (Supplementary Fig. S8). These results indicate that zinc metallochaperones that are able to reactivate p53 with minimal redox activity can synergize with traditional cytotoxic chemotherapy and ionizing radiation. This represents a new class of ZMCs with the potential to be developed as mutant p53 synergizers with (C,R). Furthermore, we have identified an optimal Cu2+:Zn2+ selectivity ratio from which to screen other zinc scaffolds that have better drug-like properties.

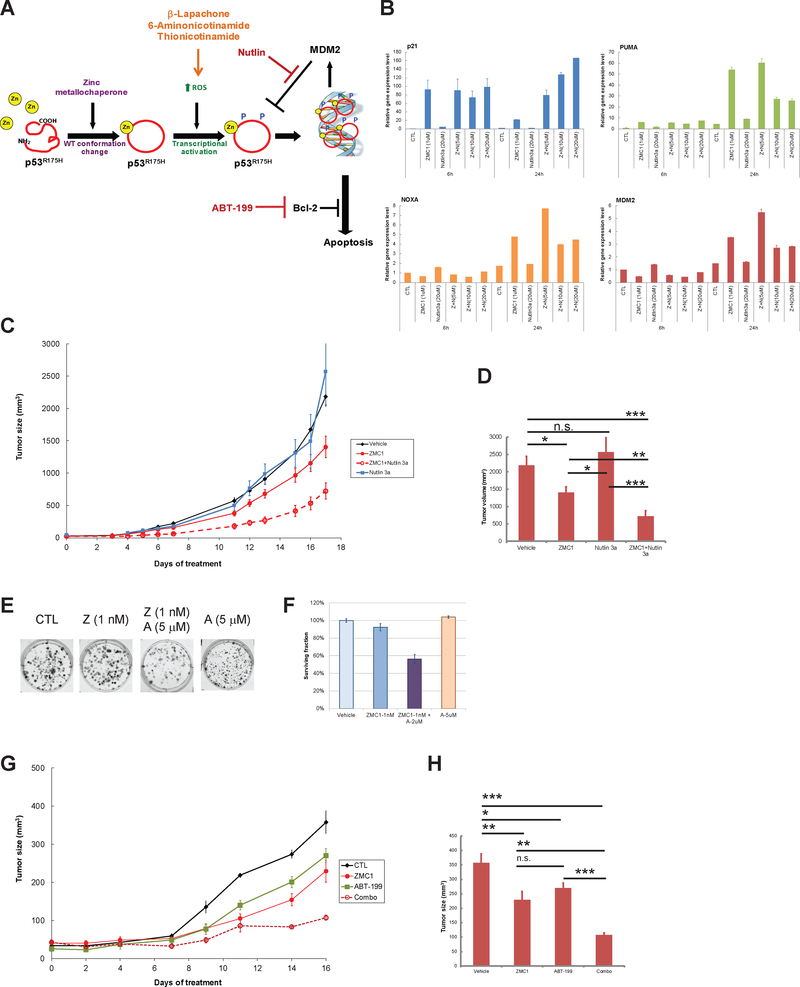

ZMC1 in Combination with Targeted Therapeutics

While we have demonstrated that ZMC1 has potent anti-cancer activity in vivo as a single agent (8,14), we sought to improve this activity through further combinatorial therapy. We took a rational approach to the selection of agents to combine with ZMC1 based upon our knowledge of its unique mechanism of action. We investigated ZMC1 with several other targeted agents that could 1) increase cellular ROS, 2) interfere with cellular anti-oxidative regulation, 3) enhance stability of the activated p53 by blocking Mdm2-p53 negative feedback regulation, or 4) enhance the apoptotic response (Fig. 4A). β-Lap cycles between its quinone (oxidized) and hydroquinone (reduced) forms, causing both the generation of ROS and a depletion of intracellular reducing agents, namely NADPH within the cell. The reductase NQO1 is the principal determinant of β-Lap cytotoxicity (23,24), and ZMC1 treatment upregulates the expression of NQO1 (9). As such, we hypothesized β-Lap could combine synergistically with ZMC1. We chose 6AN and ThioNa as rational candidates for combination with ZMC1 as they reduce the intracellular NADPH pool (25,26). ThioNa was previously shown to be synergistic in combination with chemotherapeutic drugs known to induce ROS (26). Using a cell growth inhibition assay, we observed potent synergy when cells were treated concurrently with ZMC1 and β-Lap, 6AN or ThioNa (Supplementary Fig. S9A–C). The CI values were calculated as shown in Supplementary Table S5.

Figure 4.

Combination treatment of ZMC1 and other targeted therapies displays synergy. (A) Schematic Representation of ZMC mechanism and targeted therapeutics. See text for details. (B) Combination response with ZMC1 and Nultin 3a. The TOV112D cells were treated with ZMC1 (Z, 1 μM), Nutlin 3a (N, 5, 10, or 20 μM) or combination of the two compounds. The gene expression level of the p53 target genes p21, PUMA, NOXA and MDM2 were measured by qPCR. (C). In vivo efficacy of combination of ZMC1 and Nutlin 3a was assessed using xenograft assay of TOV112D cells, as shown the tumor growth curve. The tumor volumes after 17 day treatment are shown in (D). *, p < 0.05. **, p < 0.01. ***, p < 0.001. n.s., not significant. (E) Long term effect of combination of ZMC1 and ABT-199 is evaluated by clonogenic assay. The cells were treated with vehicle control (CTL), ZMC1 (Z, 1 nM) or ABT-199 (A, 5 μM), and combinations. The quantification of colonies is shown in (F). (G) In vivo efficacy of combination of ZMC1 and ABT-199 was assessed using xenograft assay of TOV112D cells, as shown the tumor growth curve. The tumor volumes after 16 day treatment are shown in (H). *, p < 0.05. **, p < 0.01. ***, p < 0.001. n.s., not significant.

We previously reported that upon undergoing a WT conformation change in the p53R175H by ZMC1, MDM2 mediated negative autoregulation is also restored and the mutant protein levels decrease. This could be abrograted using an MDM2 antagonist (Nutlin) (14). If Nutlin could stabilize mutant protein levels, there would be more “target” for ZMC1 to act on this wild lead to greater cell kill. In cell culture, we found that the two did indeed synergize however at the higher concentrations (EC75, EC90) (Supplementary Fig. S9E and Supplementary Table S5). When we examined the effect of the combination of ZMC1 and varying concentrations of Nutlin on p53 target gene expression we observed an increase in the expression of p21, PUMA, NOXA and MDM2 that was Nutlin dose dependent in comparison to ZMC1 alone (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, the increase in gene expression was more pronounced at 24 hours as compared to 6 hours. We next evaluated the combination in an in vivo tumor growth assay to determine if this combination would produce greater efficacy than ZMC1 alone. We treated immunodeficient mice bearing TOV112D xenograft tumors with vehicle, ZMC1 alone, Nutlin alone and the combination. While ZMC1 alone administered at 5 mg/kg IP is well tolerated and typically inhibits tumor growth by 60% when administered daily in this assay, we had to lower the dose of ZMC1 to 2.5 mg/kg due to toxicity observed with the two agents. ZMC1 at this lower dose could still inhibit tumor growth albeit mildly due this dose reduction (tumor growth inhibition by 36%). As expected there was no inhibition of tumor growth with Nutlin alone while we observed significant tumor growth inhibition (67%, p = 0.0002) with the combination of ZMC1 and Nutlin (Fig. 4C–D).

We previously reported that p53 reactivation by ZMC1 resulted in cell death through a p53-regulated apoptotic pathway (14). Here we chose to test treatment of ZMC1 with ABT-199, an inhibitor of an anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 (27,28) (Fig. 4A) and also observed synergy (Supplementary Fig. S9D and Supplementary Table S5). We also evaluated the synergy between ZMC1 and ABT-199 for a more durable effect using the clonogenic assay where cells were exposed to a very low dose of ZMC1 (1 nM) which by itself caused an insignificant decrease in colonies quantified two weeks later. Using a dose of ABT-199 that was also relatively insensitive alone, we observed a significant reduction in colonies with the combination (Fig. 4E–F). We next performed Annexin-V staining to determine that the inhibition of cell growth was mediated by apoptosis. We observed an increase in the number of Annexin-V stained cells with the combination treatment of ZMC1 and ABT-199 (Supplementary Fig. S10). We further evaluated the combination in an in vivo tumor growth assay to determine if this combination would produce greater efficacy than ZMC1 alone. As described before, we treated immunodeficient mice bearing TOV112D xenograft tumors with vehicle, ZMC1 (2.5 mg/kg) alone, ABT-199 (100 mg/kg) alone and the combination. ZMC1 inhibited tumor growth by 36%, ABT-199 inhibited tumor growth by 25%, while we observed significant tumor growth inhibition (70%, p < 0.001) with the combination of ZMC1 and ABT-199 (Fig. 4G–H).

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the potential for the development of a variety of combinatorial therapeutic options to enhance the efficacy of a new class of mutant p53 reactivators called zinc metallochaperones. The impetus for this is based on the premise that the effects of cytotoxic chemotherapy and ionizing radiation are potentiated in wild type p53 tumors versus mutant ones. It follows from this that the efficacy of a small molecule that restores wild type p53 function in a mutant tumor would likely be potentiated by cytotoxic chemotherapy and/or radiation. Our data indicate that a thiosemicarbazone like ZMC1 while effective as a single agent is not synergistic with either (C,R) due to its ROS activity. This is supported by two lines of evidence: 1) synergy with cytotoxic chemotherapy and radiation can be observed when exogenous glutathione is present, indicating that quenching the ROS signal of ZMC1 can permit activation by the addition of DNA damaging agents, and 2) synergy with cytotoxic chemotherapy and radiation can be observed when using an alternative zinc scaffold that generate less ROS than ZMC1 and is still capable of generating a WT conformation change.

The findings that we observed with NTA and the NTA derivatives and their respective copper:zinc binding ratios are important because they provide a new pathway to developing an alternative subclass of ZMC’s. This putative ZMC class would be defined by their relative binding affinities for zinc and copper, illustrated in Figure 5. These new ZMCs would bind zinc in range of 1–500 nM which allows them to bind zinc tightly enough in the serum for zinc delivery but weak enough to allow them to donate zinc intracellularly to induce a mutant p53 conformation change (Fig. 5A). Their copper binding would need to be at least weaker than 10 pM which would lead to a significantly diminished ROS signal. When these compounds are combined with chemotherapy or radiation, the newly conformed mutant p53 would undergo PTMs that would activate it to then carry out a p53 mediated apoptotic program that would synergize with the (C,R) (Fig. 5B,C). Evidence for this concept has been demonstrated in a pre-clinical study using a murine breast cancer model (MMTV-neu) in which wt-p53 has been rendered inactive by low expression of HIPK2 resulting in high levels of endogenous metallothioneins that serve to “starve” p53 zinc (29,30). This model is relatively insensitive to Adriamycin. However, when supplemental zinc was administered by oral administration, the investigators observed a significant reduction in tumor volume and increase in apoptotic activity of the tumors (29).

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of the putative Zinc metallochaperones with mutant p53 reactivation and diminished copper binding. (A) The new ZMCs bind zinc in range of 1–500 nM which allows them to bind zinc tightly enough in the serum for zinc delivery but weak enough to allow them to donate zinc intracellularly to induce a mutant p53 conformation change. Their copper binding would need to be at least weaker than 10 pM which would lead to a significantly diminished ROS signal. (B) These compounds can combine with chemotherapy or radiation to promote the newly conformed mutant p53 to undergo PTMs that would activate it to then carry out a p53 mediated apoptotic program (C) that would synergize with the (C,R).

Our data reveal that the Cu2+:Zn2+ binding ratio for NTA and its derivatives is 10 – 103, compared to 108 for ZMC1. That NTA, NTA-MEE, and NTA-DEE produce significantly less ROS than ZMC1 allows us to estimate the minimum Cu2+ affinity that a metallochaperone must possess in order to generate ROS in cells. We estimate this value to be KCu ≤10−12 M. KCu values greater than this presumably render the compounds unable to compete for Cu2+ binding with endogenous sources of the metal. NTA and its derivatives are tool compounds with several shortcomings mostly pertaining to their membrane permeability that we attempted to improve through chemical modification for these proof of concept experiments. The identification of a Cu2+:Zn2+ binding ratio of 10 – 103 is a major finding of this study. This knowledge will enable us to develop a screen using fluorescent zinc sensors and use copper as a competitive binding partner with which to screen libraries of scaffolds to identify compounds with better pharmacologic properties that have this Cu2+:Zn2+ binding ratio.

Although ZMC1 failed to synergize with cytotoxic chemotherapy, we did observe potent synergy with specific targeted agents based on the understanding of the ZMC mechanism. This is particularly true with agents (e.g. 6-AN and ThioNA) that target metabolic enzymes responsible for replenishing endogenous reducing agents. We have previously shown that ZMC1 depletes cellular glutathione and NADH levels in cells (14), thus we chose 6-AN because it inhibits glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, the enzyme that initiates the pentose phosphate pathway, which is a major source of cellular NADPH. Given the robust synergy of ZMC1 with these agents it is interesting to speculate that ZMC1 may have other metabolic effects on cells that would render them susceptible to ROS mediated cell death. Recently, the Stockwell group studied the metabolomic effects of NSC319726 (ZMC1) and found that purine deoxyribonucleotides were depleted while pyrimidine deoxyribonucleosides and purine ribonucleosides were not (19). Moreover, Vousden et. al. recently found that cells that lack wild type p53 function are more susceptible to ROS mediated cell death in conditions of serine starvation (31). Serine is a major precursor for purine nucelotide biosynthesis, and so we speculate that ZMC1’s depletion of purine deoxyribonucleotides may be phenocopying the effect of serine starvation.

Our results using the combination of ZMC1 and the BCL2 inhibitor are also interesting as they suggest that perhaps ZMC1 may be functioning in a role of mitochondiral priming by upregulating proapoptotic proteins such as PUMA, BAX, or BAK which can oligermerize at the mitochondrion and lead to mitochondrial outer membrane permeablization as an explanation for the synergy with the BCL2 antagonist (32).

Our observation that ZMC1 is synergistic both in vitro and in vivo with an MDM2 inhibitor is also an important result as MDM2 inhibitors are in clinical trials now and there are far greater number of p53 mutant tumors than wild type thus mutant p53 reactivating drugs like ZMCs will greatly expand the potential pool of patients that could receive MDM2 inhibitors. Another key finding that supports further experimental use of this combination is the prolongation of expression of several p53 target genes which in turn resulted in more cell death and tumor growth inhibition after treatment.

Zinc metallochaperones represent a new pathway to reactivate mutant p53 with the potential to treat a very large number of patients. The incidence of cancers that harbor a zinc-deficient p53 mutation is approximately 75,000+ cases in the United States annually which is a conservative estimate as the number of p53 mutants with a deficiency in zinc binding is growing. Future studies that examine more carefully a range of zinc binding and de-stabilizing mutants are forthcoming. We expect these studies will reveal a significantly increased therapeutic opportunity for ZMCs by increasing the potential pool of patients whose p53 mutant tumors could be reactivated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Health (R01 CA200800, K08 CA172676), the Breast Cancer Research Foundation (D.R. Carpizo), and the National Institute of Health (F30GM113299) (A.R. Blanden). The authors thank Dr. Zhaohui Feng to provide H460-shCTL and H460-shp53 cell lines.

Abbreviation list

- C,R

Chemotherapy and radiation

- WT

Wild type

- ZMCs

Zinc metallochaperones

- PTMs

Post-translational modifications

- NAC

N-acetyl-cysteine

- GSH

Glutathione

- β-Lap

β-Lapachone

- 6-AN

6-Amino Nicotinamide

- ThioNa

Thionicotinamide

- NTA

Nitrilotriacetic acid

- MEE

Monoethyl ester

- DEE

Diethyl ester

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

Darren Carpizo, S. David Kimball, and Stewart Loh are affiliated with Z53 Therapeutics, Inc. as founder (DRC) and scientific board members (SDK, SNL) respectively. The other authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Lowe SW, Bodis S, McClatchey A, Remington L, Ruley HE, Fisher DE, et al. p53 status and the efficacy of cancer therapy in vivo. Science 1994;266(5186):807–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lowe SW, Ruley HE, Jacks T, Housman DE. p53-dependent apoptosis modulates the cytotoxicity of anticancer agents. Cell 1993;74(6):957–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lakin ND, Jackson SP. Regulation of p53 in response to DNA damage. Oncogene 1999;18(53):7644–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barbieri E, Mehta P, Chen Z, Zhang L, Slack A, Berg S, et al. MDM2 inhibition sensitizes neuroblastoma to chemotherapy-induced apoptotic cell death. Mol Cancer Ther 2006;5(9):2358–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bykov VJ, Zache N, Stridh H, Westman J, Bergman J, Selivanova G, et al. PRIMA-1(MET) synergizes with cisplatin to induce tumor cell apoptosis. Oncogene 2005;24(21):3484–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coll-Mulet L, Iglesias-Serret D, Santidrian AF, Cosialls AM, de Frias M, Castano E, et al. MDM2 antagonists activate p53 and synergize with genotoxic drugs in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells. Blood 2006;107(10):4109–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blanden AR, Yu X, Wolfe AJ, Gilleran JA, Augeri DJ, O’Dell RS, et al. Synthetic Metallochaperone ZMC1 Rescues Mutant p53 Conformation by Transporting Zinc into Cells as an Ionophore. Molecular pharmacology 2015;87(5):825–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu X, Kogan S, Chen Y, Tsang AT, Withers T, Lin H, et al. Zinc Metallochaperones Reactivate Mutant p53 Using an ON/OFF Switch Mechanism: A New Paradigm in Cancer Therapeutics. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2018;24(18):4505–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu X, Blanden AR, Narayanan S, Jayakumar L, Lubin D, Augeri D, et al. Small molecule restoration of wildtype structure and function of mutant p53 using a novel zinc-metallochaperone based mechanism. Oncotarget 2014;5(19):8879–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blanden AR, Yu X, Loh SN, Levine AJ, Carpizo DR. Reactivating mutant p53 using small molecules as zinc metallochaperones: awakening a sleeping giant in cancer. Drug Discov Today 2015;20(11):1391–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu X, Blanden A, Tsang AT, Zaman S, Liu Y, Gilleran J, et al. Thiosemicarbazones Functioning as Zinc Metallochaperones to Reactivate Mutant p53. Molecular pharmacology 2017;91(6):567–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meek DW, Anderson CW. Posttranslational modification of p53: cooperative integrators of function. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology 2009;1(6):a000950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sykes SM, Mellert HS, Holbert MA, Li K, Marmorstein R, Lane WS, et al. Acetylation of the p53 DNA-binding domain regulates apoptosis induction. Molecular cell 2006;24(6):841–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu X, Vazquez A, Levine AJ, Carpizo DR. Allele-specific p53 mutant reactivation. Cancer cell 2012;21(5):614–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang C, Lin M, Wu R, Wang X, Yang B, Levine AJ, et al. Parkin, a p53 target gene, mediates the role of p53 in glucose metabolism and the Warburg effect. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2011;108(39):16259–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chou TC. Theoretical basis, experimental design, and computerized simulation of synergism and antagonism in drug combination studies. Pharmacol Rev 2006;58(3):621–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chou TC, Talalay P. Quantitative analysis of dose-effect relationships: the combined effects of multiple drugs or enzyme inhibitors. Adv Enzyme Regul 1984;22:27–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Franken NA, Rodermond HM, Stap J, Haveman J, van Bree C. Clonogenic assay of cells in vitro. Nat Protoc 2006;1(5):2315–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shimada K, Reznik E, Stokes ME, Krishnamoorthy L, Bos PH, Song Y, et al. Copper-Binding Small Molecule Induces Oxidative Stress and Cell-Cycle Arrest in Glioblastoma-Patient-Derived Cells. Cell Chem Biol 2018;25(5):585–94 e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kocyla A, Pomorski A, Krezel A. Molar absorption coefficients and stability constants of Zincon metal complexes for determination of metal ions and bioinorganic applications. Journal of inorganic biochemistry 2017;176:53–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim KS, Kimball SD, Misra RN, Rawlins DB, Hunt JT, Xiao HY, et al. Discovery of aminothiazole inhibitors of cyclin-dependent kinase 2: synthesis, X-ray crystallographic analysis, and biological activities. Journal of medicinal chemistry 2002;45(18):3905–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith RM, Martell AE. Critical Stability Constants : Second Supplement Critical Stability Constants 6. Boston, MA: Springer US : Imprint : Springer; 1989. p 1 online resource (XVIII, 643 pages). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li LS, Bey EA, Dong Y, Meng J, Patra B, Yan J, et al. Modulating endogenous NQO1 levels identifies key regulatory mechanisms of action of beta-lapachone for pancreatic cancer therapy. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2011;17(2):275–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pink JJ, Planchon SM, Tagliarino C, Varnes ME, Siegel D, Boothman DA. NAD(P)H:Quinone oxidoreductase activity is the principal determinant of beta-lapachone cytotoxicity. The Journal of biological chemistry 2000;275(8):5416–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kohler E, Barrach H, Neubert D. Inhibition of NADP dependent oxidoreductases by the 6-aminonicotinamide analogue of NADP. FEBS Lett 1970;6(3):225–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tedeschi PM, Lin H, Gounder M, Kerrigan JE, Abali EE, Scotto K, et al. Suppression of Cytosolic NADPH Pool by Thionicotinamide Increases Oxidative Stress and Synergizes with Chemotherapy. Molecular pharmacology 2015;88(4):720–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hockenbery DM, Oltvai ZN, Yin XM, Milliman CL, Korsmeyer SJ. Bcl-2 functions in an antioxidant pathway to prevent apoptosis. Cell 1993;75(2):241–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Souers AJ, Leverson JD, Boghaert ER, Ackler SL, Catron ND, Chen J, et al. ABT-199, a potent and selective BCL-2 inhibitor, achieves antitumor activity while sparing platelets. Nature medicine 2013;19(2):202–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Margalit O, Simon AJ, Yakubov E, Puca R, Yosepovich A, Avivi C, et al. Zinc supplementation augments in vivo antitumor effect of chemotherapy by restoring p53 function. International journal of cancer 2012;131(4):E562–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Puca R, Nardinocchi L, Bossi G, Sacchi A, Rechavi G, Givol D, et al. Restoring wtp53 activity in HIPK2 depleted MCF7 cells by modulating metallothionein and zinc. Exp Cell Res 2009;315(1):67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maddocks OD, Berkers CR, Mason SM, Zheng L, Blyth K, Gottlieb E, et al. Serine starvation induces stress and p53-dependent metabolic remodelling in cancer cells. Nature 2013;493(7433):542–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ni Chonghaile T, Sarosiek KA, Vo TT, Ryan JA, Tammareddi A, Moore Vdel G, et al. Pretreatment mitochondrial priming correlates with clinical response to cytotoxic chemotherapy. Science 2011;334(6059):1129–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.