Abstract

The objective of this study was to assess the reliability of individual risk predictions based on routinely collected data considering the heterogeneity between clinical sites in data and populations. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk prediction with QRISK3 was used as exemplar. The study included 3.6 million patients in 392 sites from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink. Cox models with QRISK3 predictors and a frailty (random effect) term for each site were used to incorporate unmeasured site variability. There was considerable variation in data recording between general practices (missingness of body mass index ranged from 18.7% to 60.1%). Incidence rates varied considerably between practices (from 0.4 to 1.3 CVD events per 100 patient-years). Individual CVD risk predictions with the random effect model were inconsistent with the QRISK3 predictions. For patients with QRISK3 predicted risk of 10%, the 95% range of predicted risks were between 7.2% and 13.7% with the random effects model. Random variability only explained a small part of this. The random effects model was equivalent to QRISK3 for discrimination and calibration. Risk prediction models based on routinely collected health data perform well for populations but with great uncertainty for individuals. Clinicians and patients need to understand this uncertainty.

Subject terms: Epidemiology, Epidemiology

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) was the primary cause of death in USA, Europe and China in 20171. Multiple studies have suggested that the identification of patients with high CVD risk is important in its prevention2–5. Risk prediction models are often used to predict CVD risk for individual patients5. Examples are the Framingham risk score (FRS) and QRISK which provide risks of developing CVD in the next 10 years. Information is used on risk factors such as age, gender, body mass index (BMI), ethnicity, smoking history and disease histories6,7. FRS models have good performance in the USA population, but the risk predictions may be problematic when applied to cohorts that are hugely different from the cohort used for model development8. In the UK, treatment guidelines for the primary prevention of CVD recommend the use of QRISK2 (second version) to identify patients with high CVD risk9.

QRISK is based on routinely collected data from general practices in the UK7. Conventional approaches were used to measure discrimination and calibration in the overall population7. However, there can be substantial variation between general practices in the style of coding clinical information (coding style) and completeness of data recording10. Different coding dictionaries are also currently being used in UK primary care as the EHR systems either use Read version 2 or CTV3 codes11. The patient case-mix (referring to a variation in risk factors for disease) may also vary between practices. This variability in the underlying data sources is currently not routinely considered in the development of risk prediction models, but it could potentially lead to heterogeneity in the prediction model’s performance12. The objective of this study was to assess the level of generalisability of risk prediction models that are based on routinely collected data from EHRs, and to measure the effects of practice heterogeneity on the individual predictions of risk. The QRISK3 prediction model (for the 10 year risk of CVD) was used as an exemplar.

Methods

Data source

This study used data from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) which is a database with anonymised EHRs from 674 GP practices in the UK. The database includes 4.4 million (6.9% of the UK population) patients and is broadly representative of the UK general population in terms of age, gender and ethnicity13. CPRD includes patient records of demographics, symptoms, tests, diagnoses, therapies, health-related behaviours and referrals to secondary care. Data from over half of the practices have been linked using unique patient identifiers to other datasets from secondary care, disease-specific cohorts and mortality records13. This study was restricted to 392 general practices that have been linked to Hospital Episode Statistics (HES), Office for National Statistics (ONS) and Townsend scores7. Over 1,700 publications have used CPRD data14. Previously, CPRD data has been used to externally validate QRISK215.

QRISK prediction models

QRISK is a statistical model which is being used to predict a patient’s risk over 10 years of developing CVD (including coronary heart disease, stroke or transient ischaemic attack). The second version (QRISK2) was derived in 2008 using data from 355 practices in the QResearch database16, and validated using data from 364 practices from the THIN database17. QRISK3 is the latest version published in 2017, which includes more clinical variables, such as migraine and chronic kidney disease, than QRISK27. The QRISK3 predicted risks were calculated using the open access algorithm18. Calculations were successfully verified to be the same as predictions by the online calculator. This was done for simulated different patient groups in which each risk factor was changed sequentially covering the changes of all QRISK3 risk factors.

Study population

The study population in this study was similar to that used for the development cohort for QRISK37. Patients were included if they were aged between 25 and 84 years, had no CVD history or prescribing of statins prior to the index date. The follow-up of patients in CPRD cohort started one year after start of data collection, patient’s registration date, date of reaching age 25 years, or January 1 1998 (whatever came last) and it ended at the end of data collection, a patient leaving the practice, date patient’s death or the CVD outcome (whatever came first). Patients were censored by the earliest date among the first statin prescription, transfer or the end of follow-up19. The index date (as the start date for evaluating CVD and the baseline date for assessing a patient’s history) was chosen randomly from the period of follow-up. The random index date19 was preferred, because it gets a better spread of calendar time and age, and captures the time-relevant practice variability (e.g., change of recording and second trend of CVD incidence rate). This study considered the same risk factors as in QRISK37.

Statistical analysis

The QRISK3 predicted risks were estimated for each patient and were also averaged within each practice. Averaged predicted risks were compared to the observed risks at year 10 which were based on Kaplan Meier life tables. The observed risks were extrapolated for the 13.5% of practices with less than 10 years of follow-up. It was assumed that the life tables of these practices followed the pattern of the overall population life table. We calculated each year’s CVD relative risk (RR) by dividing the current year’s CVD proportion by the next year’s CVD proportion. The extrapolation was verified using practices with 10 years follow-up. Specifically, we randomly remove records to make these practices have less than 10 years follow-up and then compared the extrapolated risk to the observed risk. We found no evidence20 that the extrapolated risks were statistically significant to the actual observed risks.

A Cox model with a frailty (random effect) term for each practice was fitted to assess the effects of practice heterogeneity21. Patient survival time (time until censoring or CVD) was the outcome (dependent variable) and the linear predictor from the QRISK3 model was included as an offset. Each patient’s linear predictor was calculated using the patient’s risk factors and corresponding QRISK3 coefficients. Each practice’s random effects on individual risk prediction and the standard deviation of all practices’ random effects were extracted from the frailty model. Patient QRISK3 predictions and their corresponding practice random effects were combined to calculate a random effects model predicted risk. These were compared with the QRISK3 predicted risks. The distribution of the differences between the QRISK3 and the random effects model’s predicted risks were plotted.

Limited practice size or duration of follow-up could contribute to the unknown variability between risks predicted by QRISK3 and the random effects model. In order to measure this random error, we simulated data under a null hypothesis of no practice level variability and estimated the distribution of the practice level random effects, and compared this with the distribution of the practice level random effects observed in the CPRD data (i.e. a permutation test). Specifically, simulations were conducted using 2,000 datasets of the same size and follow-up as the CPRD data. The CVD outcomes were simulated by assigning a random probability from a uniform distribution (0, 1) to each patient. The random effects model was then fitted to these simulated data in order to quantify the random variability. The comparison between effects of unknown random variability and effects of practice level variability on individual patients was plotted using one million patients (50% male and 50% female) who had a QRISK3 predicted risk of 10%.

We used classical model performance measurements to compare QRISK3 with the random effects model. The data from each practice were randomly divided into two (70% and 30%) stratified by gender. The first part was used to develop the random effects model and the second part to test and calculate model performance measurements including the C-statistic22, brier score23,24 and net benefit25. These measurements were calculated using QRISK3 predictions, predictions of random effects model, patient follow-up time and patient status at the time of censoring. Empirical confidence intervals were calculated using 1,000 bootstrap samples.

Missing values for ethnicity, BMI, Townsend score, systolic blood pressure (SBP), standard deviation of SBP, cholesterol, High-Density Lipoprotein (HDL) and smoking status (only these have missing values) were imputed using Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method with monotone style26. The QRISK3 and random effects risks were then averaged based on ten imputations. We calculated random effects of CPRD practices and random effects separately for females and males consistent with QRISK3 development. The random effects of practices were calculated independently by both SAS and R with almost identical results. The random effects model used procedures from SAS 9.4 and “coxme” package for the R 3.4.2. The analyses of the datasets, missing value imputation, extrapolation validation and life tables were produced by SAS. R was used to model the data. The protocol for this work was approved by the independent scientific advisory committee for Clinical Practice Research Datalink research (protocol No 17_125RMn2). We confirm that all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Results

Table 1 shows the patient characteristics and level of data recording across the 392 general practices. The mean age of patients varied between practices (5% percentile was 40.0 years and 95% percentile was 49.8 years). Presence of CVD risk factors also varied between practices. The 5–95% range between practices was 1.9 to 16.4 for recorded history of severe mental illness. The level of data completeness also varied substantially between practices. Ethnicity was not recorded for 19.6% of patients in the 5th percentile of practices compared to 93.9% in the 95% percentiles. Life table analysis are shown in eTable 1 in the Supplement.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the general practices included in the study and the distribution of data recording.

| Mean (SD) | Distribution of characteristics across practices: Percentiles | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 95th | ||

| General characteristics of practices | ||||||

| Total number of CVD events over 10 years in each practice | 266.4 (176.5) | 17.0 | 129.5 | 251.5 | 376.5 | 581.0 |

| Average age of patients in each practice | 44.9 (3.0) | 40.0 | 42.9 | 45.0 | 46.7 | 49.8 |

| % female patients | 51.2 (2.1) | 47.5 | 50.1 | 51.2 | 52.4 | 54.5 |

| Total number of patients in each practice | 9262.3 (5072.9) | 2305.0 | 5292.5 | 8792.5 | 12180.0 | 17616.0 |

| CVD risk factors | ||||||

| % patients with alcohol abuse | 1.4 (1.2) | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 3.0 |

| % patients with anxiety | 13.8 (5.3) | 6.5 | 10.0 | 13.1 | 16.9 | 23.4 |

| % patients with HIV | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| % patients with left ventricular hypertrophy | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| % patients with atrial fibrillation | 0.7 (0.3) | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 1.3 |

| % patients on atypical antipsychotic medication | 0.4 (0.2) | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.9 |

| % patients with Chronic kidney disease (stage 3, 4 or 5) | 1.0 (0.9) | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 2.1 |

| % patients on regular steroid tablets | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| % patients with erectile dysfunction | 1.5 (0.6) | 0.7 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 2.4 |

| % patients with angina or heart attack in a 1st degree relative <60 | 3.6 (3.0) | 0.7 | 1.8 | 2.9 | 4.4 | 8.7 |

| % patients on blood pressure treatment | 6.8 (1.9) | 3.8 | 5.6 | 6.7 | 8.2 | 9.9 |

| % patients with migraines | 6.4 (2.1) | 3.2 | 4.8 | 6.4 | 7.8 | 9.6 |

| % patients with rheumatoid arthritis | 0.6 (0.2) | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 1.0 |

| % patients with severe mental illness (this includes schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and moderate/severe depression) | 7.8 (4.5) | 1.9 | 4.2 | 7.2 | 10.8 | 16.4 |

| % patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus | 0.1 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| SBP | ||||||

| Average SBP within practice | 126.8 (2.8) | 122.3 | 125.1 | 126.8 | 128.8 | 131.0 |

| % patients with missing SBP | 25.5 (7.3) | 13.9 | 20.7 | 25.3 | 30.0 | 38.5 |

| Average SBP standard deviation within practice | 9.9 (0.7) | 8.9 | 9.5 | 9.9 | 10.3 | 11.0 |

| % patients with missing SBP standard deviation | 52.7 (7.7) | 39.0 | 48.3 | 53.1 | 57.3 | 64.7 |

| BMI | ||||||

| Average BMI when recorded | 26.4 (0.7) | 25.0 | 25.9 | 26.4 | 26.9 | 27.5 |

| % patients with missing BMI | 39.2 (11.8) | 18.7 | 31.2 | 39.1 | 46.6 | 60.1 |

| Cholesterol/HDL ratio | ||||||

| Average Cholesterol/HDL ratio | 4.0 (0.2) | 3.6 | 3.8 | 4.0 | 4.1 | 4.4 |

| % patients with missing Cholesterol/HDL ratio | 64.4 (10.0) | 48.2 | 57.6 | 63.9 | 70.4 | 81.6 |

| Smoking | ||||||

| % patients who never smoked | 47.8 (7.6) | 36.0 | 43.3 | 47.9 | 52.7 | 59.4 |

| % ex-smokers | 22.3 (5.2) | 13.8 | 19.0 | 22.5 | 25.5 | 30.9 |

| % current-smokers | 29.8 (7.0) | 19.9 | 25.1 | 29.2 | 33.8 | 42.7 |

| % patients with missing smoking status | 24.2 (8.6) | 10.3 | 18.6 | 23.8 | 29.5 | 39.4 |

| Diabetes | ||||||

| % patients with type 1 diabetes | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| % patients with type 2 diabetes | 1.3 (0.4) | 0.6 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 2.0 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| % other Asian patients | 1.9 (3.2) | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 1.9 | 7.6 |

| % Bangladeshi patients | 0.4 (1.3) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 1.4 |

| % Black patients | 3.5 (5.9) | 0.1 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 3.4 | 15.3 |

| % Chinese patients | 0.7 (0.7) | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 2.0 |

| % Indian patients | 2.7 (5.3) | 0.0 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 2.9 | 10.6 |

| % patients with other ethnicity | 2.9 (3.0) | 0.3 | 0.9 | 2.0 | 3.6 | 9.1 |

| % Pakistani patients | 1.2 (3.6) | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 4.7 |

| % White patients | 86.7 (15.5) | 48.2 | 83.4 | 92.3 | 96.8 | 98.8 |

| % patients with missing ethnicity | 58.5 (23.7) | 19.6 | 38.5 | 62.5 | 77.5 | 93.9 |

| Townsend score (Socioeconomic Status) | ||||||

| % patients with Townsend score 1 (the least deprived) | 20.3 (19.2) | 0.1 | 4.1 | 14.7 | 31.1 | 59.7 |

| % patients with Townsend score 2 (less deprived) | 21.3 (16.4) | 0.6 | 8.8 | 18.6 | 30.3 | 51.8 |

| % patients with Townsend score 3 (deprived) | 21.2 (13.1) | 2.4 | 12.1 | 18.5 | 29.4 | 44.8 |

| % patients with Townsend score 4 (more deprived) | 21.1 (15.5) | 0.3 | 8.6 | 19.9 | 29.5 | 52.9 |

| % patients with Townsend score 5 (the most deprived) | 16.1 (21.8) | 0.0 | 0.4 | 7.6 | 22.3 | 66.3 |

| % patients with Townsend score missing | 0.1 (0.6) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

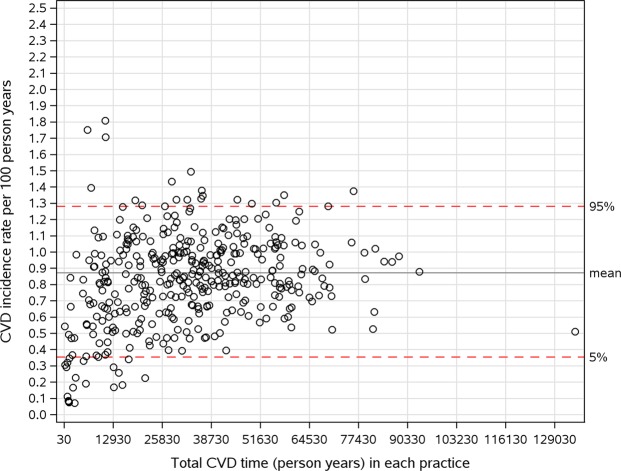

Figure 1 shows the variation of CVD incidence rate among practices by plotting CVD incidence rate per 100 person years against the total follow-up time. A large amount of variation of CVD incidence rate were found between practices.

Figure 1.

Variation of CVD incidence rate (per 100 person years) across practice.

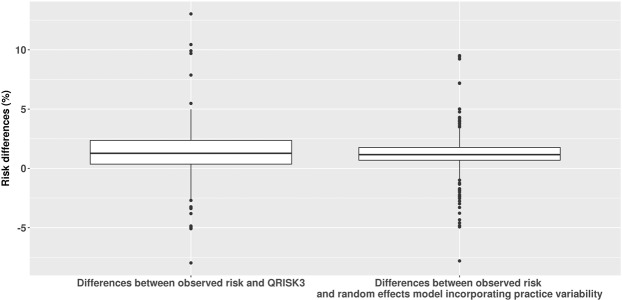

Figure 2 shows that the random effects model has less variation of differences between observed and predicted risk on practice level than QRISK3.

Figure 2.

Comparison of differences between observed and QRISK3 (random effects) mode.

Random effects model’s Brier score (0.067 (95% CI: 0.0667, 0.0682)) was close to QRISK3’s brier score (0.067 (95% CI: 0.0666, 0.0680)). The difference of Brier score between random effects model and QRISK3 was 0.002 (95% CI: 0.00008, 0.0023). Random effects model’s C-statistic (0.852 (95% CI: 0.850, 0.854)) was also close to QRISK3’s C-statistic (0.850 (95% CI: 0.848, 0.852)). The difference of C-statistic between the two models was 0.0017 (95% CI: 0.0015, 0.0020). The net benefit analysis25 shows that both of models could predict three true CVD events without adding a false negative CVD events in every 100 patients with a given threshold of 10% (visualised in eFigure 2 in the Supplement). Standard deviation of random effects of CPRD practice between females (0.174) and males (0.177) were close to each other.

Table 2 shows the inconsistencies between the risks predicted for the same group of individual patients by QRISK3 and the random effects model (visualised in eFigure 1 in the Supplement). Patients with a predicted QRISK3 risk between 9.5~10.5% were found to have a much larger range of risks in the random effects model (between about 7.6~13.3%). Table 2 also shows the level of reclassification to below or above the treatment risk threshold of 10% when using the random effect model instead of the QRISK3 predicted risk. It was found that 19.7% patients with QRISK3 predicted risk between 8.5~9.5% had a risk above the treatment threshold when using the random effects model. For patients with QRISK3 predicted score between 10.5~11.5%, 24.4% of patients were reclassified to below the treatment threshold when using the different model.

Table 2.

Inconsistencies between individual CVD risks as predicted by QRISK3 or by random effects model that incorporated practice variability.

| QRISK3 predicted CVD risk(over 10 years) | Predicted risk according to random effects model incorporating practice variability | Total number of patients | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentile | % below/above treatment threshold of 10 year CVD risk (10%) | |||||||

| 2.5th~97.5th | 5th | 25th | 75th | 95th | ≤10 | >10 | ||

| <6.5 | 0.1~6.0 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 2.6 | 5.4 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 2561602 |

| 6.5~7.5 | 5.3~9.4 | 5.5 | 6.3 | 7.6 | 8.9 | 99.0 | 1.0 | 96981 |

| 7.5~8.5 | 6.0~10.7 | 6.3 | 7.2 | 8.7 | 10.2 | 94.0 | 6.0 | 82768 |

| 8.5~9.5 | 6.8~12.0 | 7.1 | 8.2 | 9.7 | 11.4 | 80.3 | 19.7 | 72098 |

| 9.5~10.5 | 7.6~13.3 | 7.9 | 9.1 | 10.8 | 12.6 | 54.0 | 46.0 | 64477 |

| 10.5~11.5 | 8.4~14.6 | 8.8 | 10.0 | 11.9 | 13.9 | 24.4 | 75.6 | 56550 |

| 11.5~12.5 | 9.2~15.8 | 9.6 | 11.0 | 13.0 | 15.1 | 9.1 | 90.9 | 50278 |

| 12.5~13.5 | 10.0~17.1 | 10.4 | 11.9 | 14.0 | 16.3 | 2.4 | 97.6 | 45126 |

| ≥13.5 | 12.7~55.4 | 13.5 | 17.8 | 34.7 | 50.2 | 0.1 | 99.9 | 600938 |

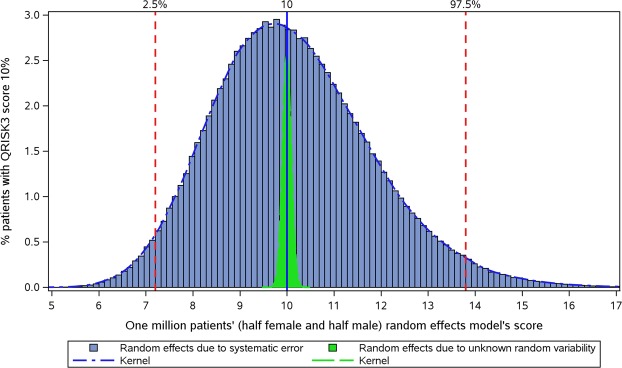

Figure 3 plots the distribution of risks predicted with the random effect model for those with a QRISK3 predicted risk of 10%. The effects of random variability (measured by simulation analysis) in the random effect model is also presented in this figure. It was found that the effect of practice variability on predicted risks for patients cannot be fully explained by random variability, as the overall distribution (blue area) with a random effects’ standard deviation of about 0.17 was much larger than the distribution due to random variability (green area) with a standard deviation for random effects of about 0.01.

Figure 3.

Distribution of predicted risks in the random effects model for patients with a QRISK3 predicted risk of 10% (using simulations in order to estimate the extent of random variability).

Discussion

Key results

This study found that incorporating practice variability in a risk prediction model substantially affected the predicted CVD risks of individual patients. The random effect model was similar to QRISK3 in terms of calibration and discrimination. Patients with a QRISK3 predicted risk of 10% had a much larger range of predicted risks after incorporating practice variability. Treatment classifications were found to be different for a substantive number of patients after considering the heterogeneity in CVD incidence between practices.

Limitation

There are several limitations of this study. Firstly, the observed risks had to be extrapolated for the practices with less than 10 years of follow-up to compare with QRISK3 (or random effects model) on practice level. The QRISK3 developers did not share the life table pattern of CVD risks over follow-up in QResearch. Although the validation showed that the result of extrapolation was not statistically significantly different from those practices with 10 years follow-up, the use of the actual changes in CVD risk over 10 years would have been preferable. Also, the definitions and classification of the risk factors could have been different from QRISK3 as the underlying EHR software systems vary between CPRD and QResearch (Vision and EMIS, respectively). However, the calibration and discrimination of QRISK3 in CPRD were consistent with those reported for QResearch, which suggest that the effects of differences in definitions was minimal.

Interpretation

Risk prediction models need to provide accurate and generalisable predictions in order to be used clinically for individual patient decision making27. Current guidelines for the development of risk prediction models do not include the evaluation of extent of heterogeneity in the underlying population (unaccounted for by the model) and its impact on the generalisability of the model. Conventional metrics in the evaluation of risk prediction models only include population level averages such as calibration and discrimination28. However, literature suggests that the risks at the population and individual levels may be determined differently29,30. An example of a tool with an acceptable average measurement but unacceptable generalisability due to heterogeneity would be a blood pressure measurement that has systematic measurement errors at different times of a day. The historic treatise by Rose emphasised that the ability to predict an average risk on a population level does not always equate to the prediction of the individuals who are going to have the event soon31. A previous study highlighted that the Framingham and QRISK2 risk prediction models showed considerable variability in predicting high CVD risk despite comparable population-level calibration and discrimination19. As Briggs emphasised, risk prediction models that provide non-extreme probabilities can never empirically be proven wrong. It was also suggested, as done in the present study, to compare the impact on predictions and decision-making with different models that are statistically comparable32. Our study found that, the predicted CVD risks for individuals were very different after incorporating previously unmeasured variability between practices and that decisions based on the QRISK3 or random effect model could be quite different.

There may be several reasons for our finding of heterogeneity between general practices unaccounted for by QRISK3. One reason may be that the data quality of EHRs varies between general practices. A study on the EHR recording of osteoporosis reported that there was variability in inter-practice data quality with clinically important codes and with multiple ways that the same clinical concept was represented33. Also, different practice computer systems have different versions of clinical coding33. Damen et al. in their recent literature review of all CVD prediction models, pointed out that consistent codes such as ICD-9 or ICD-10 should be used in models’ development and validation, as different definitions of CVD outcome lead to variation of model performance5. Another reason may be unmeasured heterogeneity in CVD risks in the populations of the different practices. There is substantive evidence that risks of disease are not uniformly distributed. A nation-wide study reported that there are severe inequalities in all-cause mortality between the North and South of England from 1965 to 200834. A study by Langford et al. reported that region accounted for four times more variation in mortality than that explained by the classification of residential neighbourhoods by household type including socioeconomic status35. In order to use a risk prediction model for individual decision making, it should be established whether or not to allow these models to miss important causal predictors. If they do, this can then lead to a substantial misclassification on an individual level.

Riley et al. have proposed a statistical way to measure heterogeneity between sites by evaluating the C-statistics across practices in funnel plots with approximate 95% confidence interval based on the observed standard error observed36. We replicated Riley’s funnel plot of QRISK2 and found similar variation of the C-statistic among practices in CPRD with QRISK3 (eFigure 4 in the Supplement). But this approach of funnel plots is limited as it does not assess the impact of heterogeneity on individual risk predictions. Random effects models are the standard approach to assess the effects of practice heterogeneity21. Our results highlight that it is not enough to only consider calibration and discrimination on the population level when assessing a prediction model’s clinical utility on individual patients. The extent of heterogeneity in risk prediction unaccounted for by the model will need to be evaluated in addition to calibration and discrimination.

Implications for Research and Practice

This study found that QRISK3 has limited generalisability and accuracy in predicting individual risks in heterogeneous settings. The predictions of CVD risks of individual patients substantially changed after incorporating practice variability which could impact the clinical decisions for many patients. In order to improve the clinical utility of these risk prediction models, the level of unexplained heterogeneity in populations, disease incidence and data quality must be assessed before implementing such models for individual clinical decision making. Given the uncertainty with risk prediction models that use routinely collected EHR data, it is questionable whether these tools should be used without additional clinical interpretation and without incorporating causal risk factors that better capture the unmeasured heterogeneity between different general practices. Recently an online calculator was launched by Public Health England which allows members of the public to estimate their heart age based on a QRISK model37. Our study indicates that these estimates could be quite different when incorporating unmeasured heterogeneity and that the level of uncertainty with these predictions is considerable.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This study is based in part on data from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink obtained under license from the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. The data is provided by patients and collected by the NHS as part of their care and support. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) is the provider of the ONS Data contained within the CPRD Data. Hospital Episode Data and the ONS Data Copyright © (2014), are re-used with the permission of The Health & Social Care Information Centre. All rights reserved. The interpretation and conclusions contained in this study are those of the authors alone. This study was funded by the China Scholarship Council. The funder’s role was to provide salary support to Yan Li. The funder did not participate in this study and did not review results; other authors are independent of the funder.

Author Contributions

Yan Li: Designed the study; conducted all statistical analysis; produced all tables and figures; wrote the main manuscript text. Matthew Sperrin: Designed the study; proposed the main statistical method; helped in interpretation of statistical results; reviewed all statistical results; reviewed and edited the main manuscript text. Miguel Belmonte: Reviewed all statistical methods and results; provided technical details of statistical methods; reviewed and edited paper. Alexander Pate: Produced the raw statistical analysis dataset; reviewed all statistical results; reviewed and edited paper. Darren M Ashcroft: Improved the major interpretation of statistical results and discussion; reviewed and edited paper; Tjeerd Pieter van Staa: Designed and supervised the study; Quality control of all aspects of the paper; wrote the main manuscript text;

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-47712-5.

References

- 1.Public Health England. Action plan for cardiovascular prevention: 2017 to 2018. Available at, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/648190/cardiovascular_disease_prevention_action_plan_2017_to_2018.pdf. (Accessed: 6th December 2017).

- 2.Piepoli MF, et al. European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur. Heart J. 2016;37:2315–2381. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cardiovascular disease prevention overview - NICE Pathways. Available at, https://pathways.nice.org.uk/pathways/cardiovascular-disease-prevention. (Accessed: 6th December 2017).

- 4.Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease Pocket Guidelines for Assessment and Management of Cardiovascular Risk. (2007).

- 5.Damen JAAG, et al. Prediction models for cardiovascular disease risk in the general population: systematic review. BMJ. 2016;353:i2416. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bitton A, Gaziano TA. The Framingham Heart Study’s impact on global risk assessment. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2010;53:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C. & Brindle, P. Development and validation of QRISK3 risk prediction algorithms to estimate future risk of cardiovascular disease: prospective cohort study. Bmj. 2017;2099:j2099. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matheny, M. et al. Systematic Review of Cardiovascular Disease Risk Assessment Tools. Systematic Review of Cardiovascular Disease Risk Assessment Tools (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), 2011). [PubMed]

- 9.NICE recommends wider use of statins for prevention of CVD | News and features | News | NICE.

- 10.Sáez C, Robles M, García-Gó Mez JM, García-Gómez JM. Stability metrics for multi-source biomedical data based on simplicial projections from probability distribution distances. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2017;26:312–336. doi: 10.1177/0962280214545122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.NHS Digital. SNOMED CT implementation in primary care - NHS Digital. Available at, https://digital.nhs.uk/services/terminology-and-classifications/snomed-ct/snomed-ct-implementation-in-primary-care. (Accessed: 1st May 2018).

- 12.Wynants L, Riley RD, Timmerman D, Van Calster B. Random-effects meta-analysis of the clinical utility of tests and prediction models. Stat. Med. 2018;37:2034–2052. doi: 10.1002/sim.7653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herrett E, et al. Data Resource Profile: Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) Int. J. Epidemiol. 2015;44:827–836. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clinical Practice Research Datalink - CPRD. Available at, https://www.cprd.com/intro.asp. (Accessed: 20th August 2017).

- 15.Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C, Brindle P. The performance of seven QPrediction risk scores in an independent external sample of patients from general practice: a validation study. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e005809. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hippisley-Cox J, et al. Predicting cardiovascular risk in England and Wales: prospective derivation and validation of QRISK2. BMJ. 2008;336:1475–82. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39609.449676.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collins GS, Altman DG. Predicting the 10 year risk of cardiovascular disease in the United Kingdom: independent and external validation of an updated version of QRISK2. BMJ. 2012;344:e4181. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e4181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.ClinRisk Ltd. QRISK®3-2017 risk calculator. 1 (2017). Available at, https://qrisk.org/three/index.php. (Accessed: 10th November 2017).

- 19.van Staa T-P, Gulliford M, Ng ES-W, Goldacre B, Smeeth L. Prediction of cardiovascular risk using Framingham, ASSIGN and QRISK2: how well do they predict individual rather than population risk? PLoS One. 2014;9:e106455. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim TK. T test as a parametric statistic. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2015;68:540–6. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2015.68.6.540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hougaard P. Frailty models for survival data. Lifetime Data Anal. 1995;1:255–73. doi: 10.1007/BF00985760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Antolini L, et al. A time-dependent discrimination index for survival data. Stat. Med. Stat. Med. 2005;24:3927–3944. doi: 10.1002/sim.2427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kronek L-P, Reddy A. Logical analysis of survival data: prognostic survival models by detecting high-degree interactions in right-censored data. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:i248–i253. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Graf, E., Schmoor, C., Sauerbrei, W. & Schumacher, M. Assessment and comparison of prognostic classification schemes for survival data. Stat. Med. 18, 2529–45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Vickers Andrew J., Elkin Elena B. Decision Curve Analysis: A Novel Method for Evaluating Prediction Models. Medical Decision Making. 2006;26(6):565–574. doi: 10.1177/0272989X06295361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schafer, J. L., Joseph L. Analysis of incomplete multivariate data. (Chapman & Hall, 1997).

- 27.Thrift, A. P. & Whiteman, D. C. Can we really predict risk of cancer? Cancer Epidemiol. 37, 349–352 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Siontis GCM, Tzoulaki I, Siontis KC, Ioannidis JPA. Comparisons of established risk prediction models for cardiovascular disease: systematic review. BMJ. 2012;3318:1–11. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e3318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Flaherty Martin, Capewell Simon. New perspectives on cardiovascular risk in individuals and in populations. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2012;66(10):855–856. doi: 10.1136/jech-2012-201409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elmore JG, Fletcher SW. The Risk of Cancer Risk Prediction: “What Is My Risk of Getting Breast Cancer?”. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1673–1675. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Somerville M. Rose’s Strategy of Preventive Medicine. J. Public Health (Bangkok). 2008;30:349–349. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdn035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.BRIGGS, W. UNCERTAINTY: the soul of modeling, probability & statistics. (SPRINGER, 2018).

- 33.de Lusignan S, et al. Problems with primary care data quality: osteoporosis as an exemplar. Inform. Prim. Care. 2004;12:147–56. doi: 10.14236/jhi.v12i3.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hacking JM, Muller S, Buchan IE. Trends in mortality from 1965 to 2008 across the English north-south divide: comparative observational study. BMJ. 2011;342:d508. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Regional variations in mortality rates in England and Wales: An analysis using multi-level modelling. Soc. Sci. Med. 42, 897–908 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Riley RD, et al. External validation of clinical prediction models using big datasets from e-health records or IPD meta-analysis: opportunities and challenges. BMJ. 2016;353:i3140. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i3140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.What’s your heart age? - NHS. Available at, https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/nhs-health-check/check-your-heart-age-tool/. (Accessed: 27th September 2018).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.