Abstract

Introduction

Globally, there are an estimated 370 million Indigenous people across 90 countries. Indigenous people experience worse health compared with non-Indigenous people, including higher rates of avoidable visual impairment. Countries such as Australia and Canada have service delivery models aimed at improving access to eye care for Indigenous people. We will conduct a scoping review to identify and summarise these service delivery models to improve access to eye care for Indigenous people in high-income countries.

Methods and analysis

An information specialist will conduct searches on MEDLINE, Embase and Global Health. All databases will be searched from their inception date with no language limits used. We will search the grey literature via websites of relevant government and service provider agencies. Field experts will be contacted to identify additional articles, and reference lists of relevant articles will be searched. All quantitative and qualitative study designs will be eligible if they describe a model of eye care service delivery aimed at Indigenous populations. Two reviewers will independently screen titles, abstracts and full-text articles; and complete data extraction. For each service delivery model, we will extract data on the context, inputs, outputs, Indigenous engagement and enabling health system functions. Where models were evaluated, we will extract details. We will summarise findings using descriptive statistics and thematic analysis.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval is not required, as our review will include published and publicly accessible data. This review is part of a project to improve access to eye care services for Māori in Aotearoa New Zealand. The findings will be useful to policymakers, health service managers and clinicians responsible for eye care services in New Zealand, and other high-income countries with Indigenous populations. We will publish our findings in a peer-reviewed journal and develop an accessible summary of results for website posting and stakeholder meetings.

Keywords: eye care, service delivery, indigenous peoples, healthcare access, ophthalmology, optometry

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study will be the first to provide a comprehensive overview and description of service delivery models to improve access to eye care for Indigenous people in high-income countries.

The review will be comprehensive, including published and grey literature of all study designs, without time period or language restrictions.

A potential limitation could be the small number of articles in the literature, particularly those that assess effectiveness of the service delivery models.

Introduction

Rationale

In 2009, there were an estimated 370 million Indigenous people living in 90 countries.1 Historically, many Indigenous people have borne both colonisation and assimilation polices, and today, throughout the world, Indigenous people continue to be marginalised due to contemporary colonialism and institutionalised racism. Consequently, Indigenous people tend to die younger than non-Indigenous people, and disproportionately experience poverty and poor health.2

Indigenous people face a range of barriers to accessing healthcare. These barriers include a lack of facilities in or near Indigenous communities, cultural and language differences with healthcare providers, marginalisation leading to reduced engagement with non-Indigenous services and financial barriers.3 In 2015, the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII) reiterated the need for models of care that ensure healthcare services are culturally, linguistically and geographically appropriate for Indigenous people.3 The UNFPII report also outlined the need for participation by Indigenous people in the design and implementation of health policies and programme so that all people are able to exercise their right to receive good healthcare and achieve equitable health outcomes.3

The barriers to healthcare outlined above apply to Indigenous people in need of eye care services. Surveys of blindness and visual impairment rarely report information on indigeneity—a recent systematic review identified 19 studies from 12 countries that compared visual impairment in Indigenous and non-Indigenous people (in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, USA, Brazil, Mexico, Paraguay, Ecuador, Fiji, Malaysia, Egypt and Kenya). The studies were heterogeneous in relation to participant age groups, visual acuity assessment and methodological rigour, but a common finding was that a high proportion of vision loss experienced by Indigenous people was due to avoidable causes of cataract and uncorrected refractive error.4 In Australia, researchers attribute the worse eye health among Indigenous people to their reduced access to eye care—particularly spectacles and cataract surgery—compared with the non-Indigenous population.5 6 Several studies have described service delivery models to improve access to eye services for Indigenous people,7–9 but no synthesis of these different models has yet been carried out.

The aim of this scoping review is to summarise the nature and extent of the existing literature on service delivery models to improve access to eye care for Indigenous people in high-income countries. We chose to undertake a scoping review rather than an alternative evidence synthesis approach because this topic has not previously been explored and we wished to identify and map the available evidence, which we anticipate will be heterogeneous.10–14 We chose to limit the review to high-income countries because findings from the review will inform a project to improve access to eye care services for Māori in Aotearoa New Zealand. Therefore, evidence from high-income countries will be most relevant to translate to the New Zealand health system context.

Definitions

Indigenous people are defined by the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues by the following criteria15:

Self-identification as Indigenous people by individuals and acceptance as such by their community.

Historical continuity and land occupation before invasion and colonisation.

Strong links to territories including land and water and related natural resources.

Distinct social, economic or political systems.

Distinct language, culture, religion, ceremonies and beliefs.

Tendency to form non-dominant groups of society.

Resolution to maintain and reproduce ancestral environments and systems as distinct people and communities.

Tendency to manage their own affairs separate from centralised state authorities.

For this review we will include all studies reporting findings for Indigenous populations regardless of the definition used, as long as none of the eight elements above are contradicted.

We have defined eye care service delivery models as any organised programme designed to provide or improve eye care services, ranging from non-specialised primary healthcare to tertiary ophthalmic care. Delivery models are used to ensure services can reach all people, or to establish bespoke services to overcome existing barriers to access.

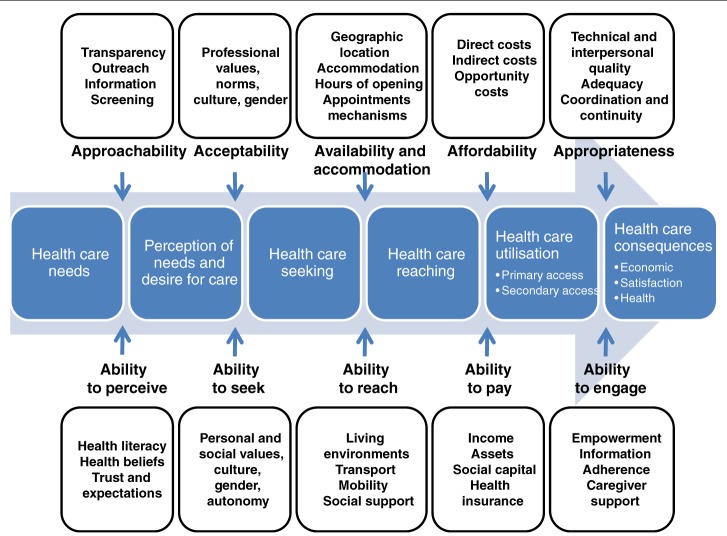

Our review will be guided by the conceptual framework of healthcare access outlined by Levesqueet al 16 (reproduced in figure 1). The authors describe access as “the opportunity to reach and obtain appropriate healthcare services in situations of perceived need for care”, and the framework emphasises the importance of considering access from the perspective of both patients (demand side) and health services (supply side). In the framework, health service access is described by five dimensions—acceptability, accessibility, availability, affordability and appropriateness. These five dimensions interact with the corresponding abilities of the population to interact with health services that is, ability to perceive, ability to seek, ability to reach, ability to pay, ability to engage.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework for access to healthcare (reproduced from Levesque et al 16).

Methods and analysis

This protocol for this scoping review is reported according to the relevant sections of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)-ScR guidelines.11

Scoping review questions

We aim to answer the following questions:

What service delivery models to improve access to eye care for Indigenous populations in high-income countries have been described in the published or grey literature?

What service delivery models to improve access to eye care for Indigenous populations in high-income countries have been evaluated in the published or grey literature?

-

For each model found in questions 1 and 2 above,

What is the context in which the model is implemented? (Eg, target population and distribution, geographic area, health practitioner availability and distribution, duration of model.)

What is the nature and extent of indigenous engagement and leadership during development and implementation? (Eg, use of a rights-based approach, level of Indigenous people decision-making and input.)

What service inputs were modified in the model? (Eg, human resources (number, cadre, frequency of service), medicines, surgeries, spectacles, facilities/location, ophthalmic equipment, language of delivery (including translation if appropriate).)

What were the enabling health system functions? (Eg, financing, governance, monitoring and evaluation, demand generation.)

What access dimensions from the Levesque access model (figure 1) were addressed? (Both demand and supply side.)

What were the service outputs? (Eg, number of consultations, number of spectacles dispensed, number of surgeries performed.)

-

In cases where the model was evaluated:

How was it evaluated?

What was the effect on access?

Eligibility criteria

This scoping review will include primary research studies describing eye care service delivery models to improve access for Indigenous people according to the definitions outlined above. The review will include qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies of all study designs. There will no time limit on publication dates and no language limitations. Studies will be limited to those taking place in high-income countries as defined by the World Bank.17 Only studies where the full text is available will be included.

Search strategy

We will search MEDLINE, Embase and Global Health using search strategies developed by Cochrane Eyes and Vision’s Information Specialist. The search strategies for all databases are included in online supplementary file 1. All databases will be searched from their inception date and no language limits will be used. We will examine reference lists of all includable articles to identify further potentially relevant reports of studies. In addition, we will search the grey literature via websites of relevant government and service provider agencies (eg, National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation). Field experts will be contacted to identify additional articles.

bmjopen-2019-029214supp001.pdf (65.9KB, pdf)

Study selection

Two reviewers (two of HB, JR, JB, LMH or AMB) will independently screen the titles and abstracts of identified studies to exclude publications that clearly do not meet the inclusion criteria. The full text article will be retrieved for review if the citation seems potentially relevant and two of these reviewers will independently assess each article against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any discrepancies between the reviewers will be resolved by discussion, and a third reviewer will be consulted if necessary. A PRISMA flow diagram will be completed to summarise the study selection process.

Data charting

A custom form will be developed in Excel for data charting. The form will be piloted on five studies by each of HB, JR, JB, LMH and AMB, and required amendments agreed by consensus. We anticipate a broad scope of included studies, so data charting will be an iterative process throughout the review and the data charting form will be amended as required. These amendments will be discussed by the reviewers and the form amended at each stage where necessary. Each included study will be charted independently by at least two reviewers. Any discrepancies between the reviewers will be resolved by discussion, and a third reviewer will be consulted if necessary.

We plan to contact study authors in the case of unclear information and will make up to three attempts by email.

Data items

The following data items will be collected during the data charting process:

Publication characteristics: title, year of publication, study design, country of origin, study setting.

-

Characteristics of service delivery model:

Context (eg, geographic area, target population and distribution, health practitioner availability and distribution, duration of model).

Indigenous engagement and leadership (eg, nature and extent of engagement during development and implementation, use of a rights-based approach, level of Indigenous people decision-making and input).

Inputs identified in the model (eg, Human resources, medicines, surgeries, spectacles, facilities/location, ophthalmic equipment, language).

If the model was evaluated, how was it evaluated and what was the effectiveness.

Data synthesis

The data will be summarised numerically using descriptive statistical methods, and qualitatively using thematic analysis. The study findings will be grouped into different types of service delivery models according to the context, inputs, health system functions and access dimensions outlined above. This will enable us to identify themes across the included studies and summarise what service delivery models have been suggested, and where evaluated, what strengths and weaknesses have been identified.

Conclusion

The aim of this review is to summarise the nature and extent of the existing literature on service delivery models to improve access to eye care for Indigenous people in high-income countries. To our knowledge, there has been no previous synthesis of this literature. This review is part of a project to improve access to eye care services for Māori in Aotearoa New Zealand. We will use the findings in a Delphi process involving Māori eye care service users, policymakers, health service managers and clinicians to identify the most promising strategies to improve access to eye care services for Māori. In subsequent research we intend on implementing and assessing the effectiveness of the prioritised strategy. Beyond New Zealand, we believe the findings of this review will be useful to policymakers, health service managers and clinicians responsible for eye care services in other countries with ndigenous populations.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval is not required, as our review will only include published and publicly accessible data.

We will publish our findings in an open-access, peer-reviewed journal and develop an accessible summary of the results for website posting and stakeholder meetings. Data generated from this review will be made available upon reasonable request.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: HB and JR drafted and revised the protocol with suggestions from JB, MH, IG, AB, LH and JE who reviewed the protocol and provided feedback on the draft. IG constructed the search. JR conceived the idea for the review. All authors read and approved the final protocol.

Funding: This work was supported by The University of Auckland Faculty Research Development Fund grant number 3716758. JR is a Commonwealth Rutherford Fellow, funded by the UK government through the Commonwealth Scholarship Commission in the UK. LMH is the Robert Leitl Research Fellow, funded by the Robert Leitl Trust, New Zealand. MH was a NZ UNESCO L’Oréal For Women In Science Fellow during the study.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Hall G, Patrinos H. Indigenous peoples, poverty and development. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anderson I, Robson B, Connolly M, et al. Indigenous and tribal peoples' health (the Lancet-Lowitja Institute global collaboration): a population study. Lancet 2016;388:131–57. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00345-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues State of the World’s Indigenous Peoples: Indigenous Peoples’ access to Health Services. The Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations, 2015. Available: https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/publications/2015/09/state-of-the-worlds-indigenous-peoples-2nd-volume-health/

- 4. Foreman J, Keel S, van Wijngaarden P, et al. Prevalence and causes of visual loss among the Indigenous peoples of the world: a systematic review. JAMA Ophthalmol 2018;136:567–80. 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2018.0597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Foreman J, Xie J, Keel S, et al. Utilization of eye health-care services in Australia: the National eye health survey. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2018;46:213–21. 10.1111/ceo.13035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kelaher M, Ferdinand A, Taylor H. Access to eye health services among Indigenous Australians: an area level analysis. BMC Ophthalmol 2012;12:51 10.1186/1471-2415-12-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Napper G, Fricke T, Anjou MD, et al. Breaking down barriers to eye care for Indigenous people: a new scheme for delivery of eye care in Victoria. Clin Exp Optom 2015;98:430–4. 10.1111/cxo.12325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Murray R, Metcalf S, Lewis P, et al. Sustaining remote-area programmes: retinal camera use by Aboriginal health workers and nurses in a Kimberley partnership. Med J Aust 2005;182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Taylor HR, Boudville AI, Anjou MD. The roadmap to close the gap for vision. Med J Aust 2012;197:613–5. 10.5694/mja12.10544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, et al. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018;18:143 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 2010;5:1–9. 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, et al. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015;13:141–6. 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. United Nations department for economic and social affairs Secretariat of the permanent on Indigenous issues. United Nations: State of the world’s indigenous peoples, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Levesque J-F, Harris MF, Russell G. Patient-Centred access to health care: conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int J Equity Health 2013;12:1 10.1186/1475-9276-12-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. The World Bank Country and lending groups [Internet]. Available: http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-classifications/country-and-lending-groups [Accessed 2 Dec 2018].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-029214supp001.pdf (65.9KB, pdf)