Abstract

Introduction

Pregnant women who eat a balanced diet usually practice physical activity (PA) regularly; there are many studies on PA during pregnancy and the results for the mother and baby. However, the guideline for PA during pregnancy is very general and is not quantified. The primary objective of this study is to examine the nutritional habits and levels of PA of women during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Second, it will determine the effects of these aspects on the mother and newborn baby. Its third objective is to identify the factors which influence the practice of PA during this phase.

Methods and analysis

Se trata de un estudio prospectivo de cohortes que dura 2 años, f rom de septiembre de 2018 para setiembre del 2020 La muestra será reclutado en tres Atención Primaria centros en el área de salud de Toledo (España). Las participantes serán mujeres embarazadas de 18 a 40 años. Ancianos que deben asistir a todos los controles durante el embarazo y el período posparto. La PA se cuantificará utilizando la acelerometría, mientras que los hábitos nutricionales y el ejercicio físico se evaluarán mediante cuestionarios validados. Se registrarán los síntomas del embarazo y el período posparto, junto con los parámetros bioquímicos y los datos antropométricos. Los resultados primarios se determinarán en las mujeres embarazadas: aumento de peso, incidencia de diabetes mellitus gestacional, preeclampsia e hipertensión inducida por el embarazo. Los resultados secundarios incluyen la duración del embarazo y el peso al nacer, la puntuación de Apgar (1 min / 5 min), el tipo de reanimación (I / II / III / IV) y el pH de la sangre del cordón umbilical en los recién nacidos.

Discussion

Although the beneficial effects of PA during pregnancy are known, there is a need to perform studies that quantify the amount of PA undertaken by women during pregnancy and the postpartum period. The objective of such studies is to establish science-based individualised guidelines for PA for women during this stage of their lives.

Keywords: accelerometer, neonatal outcomes, physical activity, pregnancy outcomes

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This research will offer new information about how pregnant and postpartum women, like their neonates, respond to moderate physical activity without showing adverse effects.

The study will offers new information about nutritional behaviour of pregnant women, the impact of diet on their newborn and the influence on the mother’s puerperium.

The Yana-C questionnaire has not been validated in pregnant women.

To control for the limitation mentioned above we will use a self-administered questionnaire about good adhesion to the Mediterranean diet (PREDIMED).

Introduction

When women are pregnant, they take better care of their health and are more receptive and likely to make changes that lead to a healthier lifestyle. Recommendations to increase physical activity (PA) and to eat a healthy diet therefore have a positive effect throughout pregnancy and the postpartum period on the mother as well as their newborn baby.1

The scientific literature contains relevant information on the effects of moderate and regular PA during pregnancy: mothers gain less weight and reduce the risk of pregnancy-related diabetes, pre-eclampsia and hypertension1 2; higher stress tolerance and earlier neonatal neuro-behavioural maturity.3 Among other recommendations, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (ACOG) suggests that pregnant women with no medical or obstetric complications should perform at least 30 min of moderate PA every day of the week.4 Nevertheless, the WHO admits that further research is needed into guidelines for pregnant women on the amount of PA they should undertake. The WHO currently states that the general considerations for PA in adults also apply to pregnant women, that is, at least 75 min of vigorous PA or 150 min of moderate PA per week, including the strengthening of the major muscle groups.5

On the other hand, several studies on the effects of physical exercise during pregnancy found no relevant benefits for the mother and even detected unsatisfactory results in comparison with other more sedentary mothers.6 7 All these considerations show the need for research to confirm the correct guideline for PA that leads to the greatest health benefits for mothers as well as their newborn babies.

As well as being physically active, it is also recommended that women eat a healthy diet during pregnancy and the postpartum period. During this life stage, those women who eat a healthy diet were also found to do more exercise.8 Data show that low adhesion to the Mediterranean diet may be associated with a reduction in the weight of the placenta and low neonatal weight,9 10 as well as the risk of pregnancy-associated diabetes in terms of the classification and diagnosis of diabetes,11 which indicates how important diet is during this phase of women’s lives.12 Epidemiological studies of pregnant women indicate that their weight prior to pregnancy, height, blood levels of glucose and weight gain during pregnancy are factors that influence fetal development.10

While it is important that mothers should not gain excessive weight during pregnancy, they should also return to their pre-pregnancy weight after giving birth. This is because there is an association between the risk of obesity after birth and excessive weight gain during pregnancy.13 14 On the other hand, controlling weight solely by diet after giving birth is less effective than a combination of diet and physical exercise.14 The promotion of healthy habits in terms of a combination of diet and PA during pregnancy and the postpartum period may therefore be highly beneficial for women.15 16

The main objective of this research is to examine independently the nutritional habits and the levels of PA in women during pregnancy and the postpartum period by means of validated questionnaires and accelerometers.

The secondary objectives are

(i) To calculate the relationship between the level of PA and nutritional habits during pregnancy and the postpartum period in terms of the results for mothers in: weight gain, the incidence of pregnancy-related diabetes mellitus, pre-eclampsia and pregnancy-induced hypertension and type of birth. This relationship is also examined in terms of the results for newborn babies: duration of pregnancy, weight at birth, Apgar score 1 min/5 min, type of reanimation and umbilical cord blood pH.

(ii) To identify the factors that influence the performance of PA during each stage of pregnancy and the postpartum period (using the Spanish version of the Pregnancy Symptoms Inventory (PSI) and the Edinburgh scale).

Methods/Design

A 2-year study of cohorts during pregnancy and the postpartum period in Health Area No. 1, Toledo (Spain).

A multicentre study will be undertaken in the healthcare facilities of Castilla-La Mancha Health Service (SESCAM), in the areas of primary and specialised healthcare: (i) Buenavista Health Centre; (ii) Santa Bárbara Health Centre; (iii) Yepes Health Centre; (iv) Polán Health Centre and (v) the Virgen de la Salud Hospital.

The sample will be recruited by matrons by means of non-probabilistic consecutive sampling in Primary Care facilities.

Study recruitment started on 1 September 2018 and the study is expected to last until September 2020.

Inclusion criteria

Women aged from 18 to 40 years old.

Pregnancy having lasted 14 weeks or less.

A single fetus.

Quarterly pregnancy check-ups in Primary Care facilities.

The intention of giving birth in the Virgen de la Salud Hospital.

Comprehension of spoken and written Spanish.

Exclusion criteria

Women with conditions prior to pregnancy that hinder or limit the practice of PA at the time of recruitment (one or more contraindications for PA according to the ACOG, diabetes or arterial hypertension prior to pregnancy, or more than one previous abortion).

Not signing the informed consent document.

Not understanding written and spoken Spanish.

Women who do not complete the follow-up.

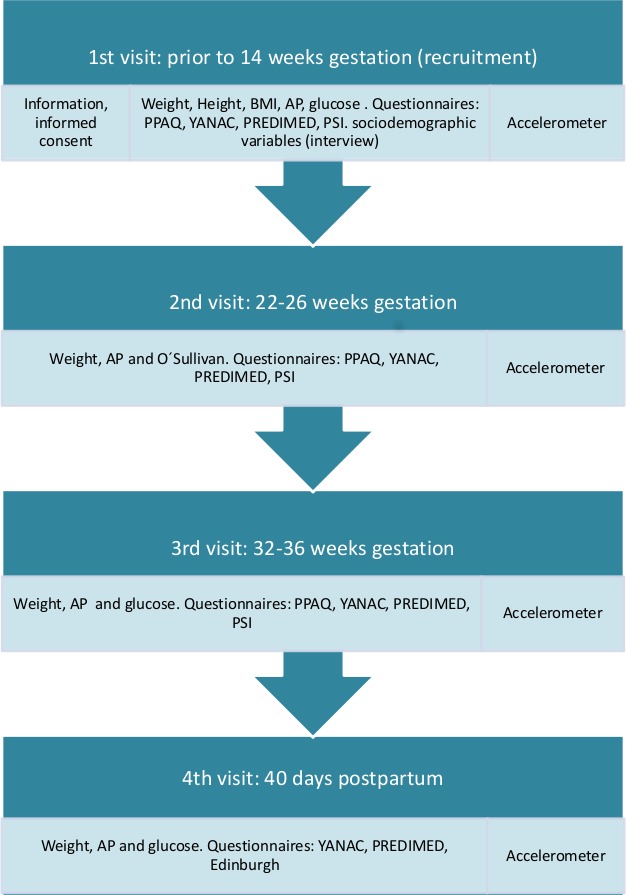

Variables (figure 1)

Figure 1.

Data gathering phases. AP, arterial blood pressure; BMI, body mass index.

Sociodemographic variables

The following data will be recorded in the first interview age (years), marital status (married, single, living with partner, others), country of origin, educational level (none, primary, secondary, technical college, university), economic resources (low, medium or high), working status (housewife, unemployed, in work).

Anthropometrics

All measurements will be taken by trained investigators to minimise inter-observer variability, using the same apparatus: scales (mechanical, with a range up to: max. 220 kg d=50 g) and a wall-mounted height gauge (range: 0–200 cm). The subjects will be measured in the first, second, third and fourth (post partum) visit in the morning for weight (without shoes and in light clothing) and height (standing upright without shoes and with the median sagittal line touching the board) will be measured in the first visit. The average of two measurements will be taken. Body mass index (BMI) will be calculated as body mass (in kilograms) divided by height2 (in metres).

Arterial blood pressure

It will be measured twice, with a 5-min interval between measurements. The first measurement will be made after at least 5-min rest. Women will be seated, in relaxing conditions, with the right arm semi-flexed at heart level. Blood pressure will be measured with an Omron M5-I monitor (Omron Healthcare UK).

Biochemical parameters

Study data will be collected by trained research staff. All blood samples will be taken from the right or left cubital fossa, after an 8–12 hour fast, between 08:00 and 10:00. We will determine glucose, insulin and O’Sullivan. In the study population women will be routinely screened for gestational diabetes at 22–26 weeks of gestation with a non-fasting oral glucose challenge test in which venous blood will be sampled 1 hour after a 50 g oral glucose load. If the 1-hour glucose result are at least 1.40 g/L, the participant will be referred to a 100 g fasting glucose 3-hour tolerance test. Normal results will be a blood glucose below 10.55 g/L at baseline, below 1.90 g/L at 1 hour, below 1.65 g/L at 2 hours and below 1.45 g/L at 3 hours.

Physical activity

PA will be measured using the Spanish version of the Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire (PPAQ).17 This self-administered questionnaire contains 32 items which measure the frequency and duration of PA during pregnancy (first, second and third visit), in terms of: being sedentary, doing household chores/care, work-related activity and sports activities.

Accelerometry will use Actigraph brand GT3X accelerometers to objectively measure PA levels during the three trimesters of pregnancy and during the postpartum period. Accelerometry has been used in several population groups, including pregnant women, to quantify PA and relate the data obtained with other factors.18 The criteria for the inclusion of data in the analysis of results will be a minimum recording of 4 days, including at least 3 weekdays and 1 weekend day, with imperceptible recording of 600 min/day.19 20 The device will be worn on an elastic strap on the wrist of the non-dominant hand during seven consecutive days and nights, except for bathing and performing activities in the water, in each one of the measurements (figure 1). The data gathering interval in this study will last for 60 s (epochs), as this has been shown to be valid for measuring PA in adults. The accelerometer will also supply information on posture, sleep latency, total sleep time, sleep efficiency, the intensity of PA, periods of activity, periods of sedentary behaviour, rhythm intervals, gross acceleration, energy consumption, MET ratios and the number of steps.21 All subjects will be verbally and in writing instructed on how to use the accelerometer. Data will be downloaded using Actilife V.6.13.3 software.

To identify the factors which influence carrying out PA the Spanish version of the PSI will be used22 during pregnancy, while the Edinburg depression scale will be used in the postpartum period.23 The PSI is a self-administered questionnaire that evaluates the frequency and degree of limitation of everyday activities arising due to different causes (not at all, a little, a lot) involving 41 intrinsic symptoms of pregnancy. The Edinburgh scale consists of 10 questions with four possible replies, of which the subjects must choose one based on how they felt over the past 7 days. Although the final score will indicate the probability of post-natal depression, it will not vary according to its severity.

Variables associated with nutritional habits

The ‘Young Adolescents’ Nutrition Assessment on Computer’ (YANA-C)24 will be used, together with the Mediterranean diet adherence questionnaire (PREDIMED)25 to gather data on the diet of pregnant and postpartum women.

YANA-C consists of listing the foods consumed in the previous 24 hours, and it is divided into breakfast, mid-morning, lunch, tea, dinner and after dinner. Energy (kcal) and macronutrient intake (percentages) will be measured by two non-consecutive 24 hours recalls (weekday and weekend day), using YANA-C software program. Percentages of Energy intake from carbohydrate, protein, fat and macronutrients (g) relative to weight (kg) will be calculated.

PREDIMED is a self-administered questionnaire containing 14 questions that are answered by a score showing low (<9 points) or good adhesion to the Mediterranean diet (>9 points).

Pregnancy data

Duration of pregnancy (weeks and days of amenorrhoea, according to the date of the last period and confirmation by ultrasound scan), medical problems during pregnancy (Yes/No) premature birth (fewer than 37 weeks’ gestational age), arterial hypertension, gestational diabetes (defined according to the criteria of the American Diabetes Association,26 fetal growth restriction and a reduction in amniotic fluid).

Birth data

Type of analgesia during birth (none, epidural, spinal), onset of birth (spontaneous/induced, reason for induction), duration of pregnancy (weeks and days), type of birth (natural, instrumental, caesarean), reasons for an instrumental or caesarean birth, episiotomy (yes/no), perineal tear (yes/no, grade I/II/III/IV), type of birth (spontaneous, manual, directed), duration of dilation (minutes), duration of expulsion (minutes).

Neonatal data

Weight (grams), sex (male/female), 1/5 min APGAR scale score, type of reanimation (I/II/III/IV), umbilical cord blood pH (arterial and venous), fetal calotte pH (if performed).

Postpartum data

Bleeding (physiological/moderate/severe), condition of perineum (haematoma/oedema/pain/haemorrhoids/suture dehiscence) and postpartum complications.

Data corresponding to pregnancy, birth, the newborn baby and in the postpartum period will be obtained from the clinical history of the mother.

Patient and public involvement

There was no patient or public involvement in the design of this protocol.

Statistical analysis

Sample size was calculated using Epidat 4.1, with an exposed/non-exposed ratio of 1. The outcome variable was gestational diabetes mellitus. A prevalence of 14% was assumed in the group of exposed (sedentary) women and a prevalence of 3%27 was assumed in the group of non-exposed women (who were active according to the current criteria of the American College of Sports Medicine-30 minutes/day of moderately intense PA every day or almost every day, accumulating at least 150 min/week). A 5% alpha error and 80% statistical power were assumed. Following these premises, it was estimated that 194 pregnant women should be included in the study. Approximately 5% should be added to these premises to account for possible non-responders (women who did not wish to take part in the study) and drop-outs.

Descriptive statistics with precision estimates will be used to report the prevalence of each parameter using a cross-sectional data. Mixed regression models will be used to examine the relationship between dependent variables and patient health, measured using one or more explanatory variables that express exposure to a risk factor and controlling for baseline values. The results will be expressed as absolute differences in changes in variables between the baseline and final measurements (95% CI).

All statistical analyses will be performed with the statistical software IBM SPSS Statistics V.24, and the level of significance will be set at p<0.05.

Discussion

The results of the study will allow better advise to pregnant women about PA and nutrition. They will also make it possible to update health education programme for this population group, leading to more benefits for mothers as well as their children.

The adherence to an exercise routine is influenced by factors such as: the habit of exercising before pregnancy, the sociocultural level, equality and the insistence by healthcare workers that pregnant women perform PA. The study by Nascimento et al showed that half of the participating women stopped doing physical activity during pregnancy.28

Therefore, it is important that healthcare professional provide information about the risks and benefits of PA, while establishing personalised guidelines adapted to the specific needs of each woman. All information supplied to future mothers must therefore be supported by scientific evidence.29 The goal is to guide future mothers towards a healthy lifestyle and change their habits. This is not only to prevent pathologies during pregnancy and in the postpartum period, but rather to ensure that their new habits last a lifetime.

The study will also record biochemical parameters which, in association with the data collected through the scales and the accelerometer, will allow to prevent the risk of non-transmissible diseases during pregnancy and in the postpartum period. Biochemical changes are closely linked to the amount of mothers’ PA, and both the quality and type of their diet during pregnancy and in the postpartum period. An example of this relationship is the use of the biochemical parameter of glucose as a gestational diabetes marker.30 Pérez-Ferre et al intervened in a group of women with gestational diabetes, by changing their dietary habits and encouraging physical exercise. They found that the risk of developing type 2 diabetes in the future decreased in the intervention group compared with the control group.11

Therefore, it is necessary to perform more extensive studies on the quantity of PA of women during pregnancy and in the postpartum period, to set guidelines based on scientific evidence. Accelerometers provide reliable and accurate data, and they may be considered a motivating factor in maternal education programme, as they make pregnant women aware of the amount of PA they perform, thereby stimulating the regular practice of PA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the healthcare facilities of Castilla-La Mancha Health Service (SESCAM), in the areas of Primary and Specialised healthcare: (i) Buenavista Health Centre; (ii) Santa Bárbara Health Centre; (iii) Yepes Health Centre; (iv) Polán Health Centre and (v) the Virgen de la Salud Hospital, that have shown their interest in participating in our study.

Footnotes

Contributors: Conceived and designed the experiments: AMM, MMDDA, MVA, SGC and NMAP; statistical and epidemiological support: JLGP, BGL, BMG, SGC and NMAP. Contributed reagents/ materials/analysis tools: AMM, MMDA, MVA, BGL and BMG. Wrote the paper: AMM, SGC and NMAP. All authors established the methods and questionnaires, provided comments on the drafts, and read and approved the final version.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This research project has been approved by the Toledo Hospital Complex (THC) Clinical Research Ethics Committee, approval number 125. It has also been approved by the Primary and Specialised Care Nursing Boards for implementation and development. Before they sign the consent document to take part in the study, all the participants will be informed verbally and in writing about the study procedure as well as its objectives. Data confidentiality will be guaranteed, and it will also be possible for participants to revoke their consent for the study at any stage of the same. Study outcomes will be disseminated at international conferences and published in peer-reviewed scientific journals.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Muktabhant B, Lawrie TA, Lumbiganon P, et al. . Diet or exercise, or both, for preventing excessive weight gain in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;6 10.1002/14651858.CD007145.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aune D, Saugstad OD, Henriksen T, et al. . Physical activity and the risk of preeclampsia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiology 2014;25:331–43. 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Clapp JF, Lopez B, Harcar-Sevcik R. Neonatal behavioral profile of the offspring of women who continued to exercise regularly throughout pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999;180:91–4. 10.1016/S0002-9378(99)70155-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Artal R, O’Toole M, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists . Exercise during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2003;46:496–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Organization WH Who guidelines Approved by the guidelines review Committee. Use Tuberc Interferon-Gamma Release Assays IGRAs Low- Middle-Income Ctries Policy Statement Geneva World Health Organ, 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vallim AL, Osis MJ, Cecatti JG, et al. . Water exercises and quality of life during pregnancy. Reprod Health 2011;8:14 10.1186/1742-4755-8-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kramer MS, McDonald SW, Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group . Aerobic exercise for women during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;40 10.1002/14651858.CD000180.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Olmedo-Requena R, Fernández JG, Prieto CA, et al. . Factors associated with a low adherence to a Mediterranean diet pattern in healthy Spanish women before pregnancy. Public Health Nutr 2014;17:648–56. 10.1017/S1368980013000657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Timmermans S, Steegers-Theunissen R, Vujkovic M, et al. . The Mediterranean diet and fetal size parameters: the generation R study 2014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10. Mesa SLR, Sosa BEP. Implicaciones del estado nutricional materno en El peso al nacer del neonato. Perspect En Nutr Humana 2011;11:179–86. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pérez-Ferre N, Del Valle L, Torrejón MJ, et al. . Diabetes mellitus and abnormal glucose tolerance development after gestational diabetes: a three-year, prospective, randomized, clinical-based, Mediterranean lifestyle interventional study with parallel groups. Clin Nutr 2015;34:579–85. 10.1016/j.clnu.2014.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Karamanos B, Thanopoulou A, Anastasiou E, et al. . Relation of the Mediterranean diet with the incidence of gestational diabetes. Eur J Clin Nutr 2014;68:8–13. 10.1038/ejcn.2013.177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Amorim AR, Rössner S, Neovius M, et al. . Does excess pregnancy weight gain constitute a major risk for increasing long-term BMI? Obesity 2007;15:1278–86. 10.1038/oby.2007.149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Adegboye ARA, Linne YM, exercise Dor. Or both, for weight reduction in women after childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gomez Cantarino S, Comas Matas M, Velasco A, et al. . Vivencias, experiências E diferenças sexuais: mulher puérpera espanhola E imigrante. Área Palma sanitária de Maiorca (Espanha). Rev Enferm Referência 2016:115–23. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Magann EF, Evans SF, Weitz B, et al. . Antepartum, intrapartum, and neonatal significance of exercise on healthy low-risk pregnant working women. Obstet Gynecol 2002;99:466–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chasan-Taber L, Schmidt MD, Roberts DE, et al. . Development and validation of a pregnancy physical activity questionnaire: corrigendum. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2011;43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Aguilar MC, Sánchez AL, Guisado RB, et al. . Accelerometer description as a method to assess physical activity in different periods of life. systematic review 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Trost SG, McIver KL, Pate RR. Conducting accelerometer-based activity assessments in field-based research. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2005;37(11 Suppl):S531–S543. 10.1249/01.mss.0000185657.86065.98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Freedson PS, Melanson E, Sirard J. Calibration of the computer science and applications, Inc. accelerometer. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 1998;30:777–81. 10.1097/00005768-199805000-00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen KY, Bassett DR. The technology of accelerometry-based activity monitors: current and future. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2005;37(11 Suppl):S490–S500. 10.1249/01.mss.0000185571.49104.82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Foxcroft KF, Callaway LK, Byrne NM, et al. . Development and validation of a pregnancy symptoms inventory. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013;13:3 10.1186/1471-2393-13-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vega-Dienstmaier JM, Mazzotti Suarez G, Campos Sanchez M. Validación de Una versión en español de la Escala de Depresión postnatal de Edimburgo. Actas Esp Psiquiatr 2002;30:106–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vereecken CA, Covents M, Matthys C, et al. . Young adolescents' nutrition assessment on computer (YANA-C). Eur J Clin Nutr 2005;59:658–67. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Martínez-González Miguel Ángel, Corella D, Salas-Salvadó J, et al. . Cohort profile: design and methods of the PREDIMED study. Int J Epidemiol 2012;41:377–85. 10.1093/ije/dyq250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. American Diabetes Association 2. classification and diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care 2017;40(Suppl 1):S11–S24. 10.2337/dc17-S005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Han S, Middleton P, Crowther CA, et al. . Exercise for pregnant women for preventing gestational diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;94 10.1002/14651858.CD009021.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nascimento SL, Surita FG, Godoy AC, et al. . Physical activity patterns and factors related to exercise during pregnancy: a cross sectional study. PLoS One 2015;10:e0128953 10.1371/journal.pone.0128953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Poyatos-León R, Sanabria-Martínez G, García-Prieto JC, et al. . A follow-up study to assess the determinants and consequences of physical activity in pregnant women of Cuenca, Spain. BMC Public Health 2016;16:437 10.1186/s12889-016-3130-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sanabria-Martínez G, García-Hermoso A, Poyatos-León R, et al. . Effectiveness of physical activity interventions on preventing gestational diabetes mellitus and excessive maternal weight gain: a meta-analysis. BJOG: Int J Obstet Gy 2015;122:1167–74. 10.1111/1471-0528.13429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.