Abstract

Objectives

To determine mental health outcomes for children with a history of child protection system involvement, accounting for pre-existing adversity, and to examine variation in risk across diagnostic groupings and child protection subgroups.

Design

A longitudinal, population-based record-linkage study.

Participants

All children in Western Australia (WA) with birth records between 1990 and 2009.

Outcome measures

Mental health diagnoses, mental health contacts and any mental health event ascertained from International Classification of Diseases codes within WA’s Hospital Morbidity Data Collection and Mental Health Information System from birth until 2013.

Results

Compared with children without child protection contact, children with substantiated maltreatment had higher prevalence of mental health events (37.4% vs 5.9%) and diagnoses (20% vs 3.6%). After adjusting for background risks, all maltreatment types were associated with an almost twofold to almost threefold increased hazard for mental health events. Multivariate analysis also showed mental health events were elevated across all child protection groups, ranging from HR: 3.54 (95% CI 3.28 to 3.82) for children who had entered care to HR: 2.31 (95% CI 2.18 to 2.46) for unsubstantiated allegations. Maternal mental health, aboriginality, young maternal age and living in socially disadvantaged neighbourhoods were all associated with an increased likelihood of mental health events. The increase varied across diagnostic categories, with particularly increased risk for personality disorder, and frequent comorbidity of mental health and substance abuse disorders.

Conclusions

Young people who have been involved in the child protection system are at increased risk for mental health events and diagnoses. These findings emphasise the importance of services and supports to improve mental health outcomes in this vulnerable population. Adversities in childhood along with genetic or environmental vulnerabilities resulting from maternal mental health issues also contribute to young people’s mental health outcomes, suggesting a role for broader social supports and early intervention services in addition to targeted mental health programmes.

Keywords: child protection, mental health, abuse and neglect, linked data, population

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Linked population data allow the examination of a sensitive topic such as child maltreatment without the recruitment and sample loss challenges that affect many surveys.

The longitudinal analysis between mental health diagnoses in the hospital data allowed us to identify the level of increased risk for different mental health problems among subgroups in the child protection system.

However, data on outpatient mental health services provided by private hospitals, private psychologists/psychiatrists or managed by general practitioners were not available; therefore, this study’s estimates of prevalence of mental health events are likely to be underestimates.

There may also be some under ascertainment of maltreatment types resulting from recording of only one maltreatment type per investigation.

Introduction

It is established that children who experience child abuse and neglect are at an increased risk of poorer mental health outcomes.1 The National Scientific Council on the Developing Child states that chronic stress to which maltreated children may be exposed, in the absence of consistent and supportive relationships with adult caregivers, has negative impacts on children’s developing brain.2 Furthermore, children who experience child abuse and neglect may be exposed to complex and chronic trauma which can result in persistent psychological problems.

There are, however, many factors that increase this risk including the fact that many of these children come from families where parental mental health issues are present. Therefore, there may be genetic and adversity factors that increase the level of vulnerability to poor mental health, in addition to the trauma associated with being a victim of abuse and/or neglect. In fact, research has suggested that familial risk factors prior to child maltreatment may be a stronger risk factor for poor mental health outcomes.3 In order to appropriately support young people involved in child welfare services, a strong evidence base regarding the burden of mental health issues, the type of mental health problems and the pre-existing risk that young people are exposed to is essential to guide the provision of services to ensure improved outcomes for this group of young people. This is also essential at a time when there is a national focus in Australia on improving the outcomes of young people who have been in out-of-home care and whether out-of-home care experiences reduce the risk of poor mental health outcomes into adulthood.

The challenges in developing a strong evidence base in this area include

Long-term follow-up for children who have been involved in child protection services.

Accounting for pre-existing adversity for these children prior to their involvement in child protection services.

Accounting for type of maltreatment, and child protection interventions that may influence mental health outcomes.

Having an appropriate comparison group and large enough sample size in the cases to enable valid comparison.

Vinnerljung et al 4 used Swedish national register data to overcome some of these challenges, finding that former child welfare clients were five to eight times more likely than peers in the general population to have been hospitalised for serious psychiatric disorders in their teens and four to six times in young adulthood. Even after accounting for parental and socioeconomic factors, there was still a threefold to fourfold increased risk in adolescence and twofold to threefold in adulthood. The objective of our research was to build on these findings using an Australian population-based cohort of children and linked mental health register and child protection agency data taking into account parental mental health history, sociodemographic factors, level of child protection involvement and type of maltreatment. We could then determine mental health outcomes for children with a history of child protection system involvement, accounting for pre-existing adversity, and examine variation in risk across diagnostic groups and child protection subgroups.

Methods

Population and data sources

To determine the mental health outcomes for children involved in child protection, we conducted a population-based record-linkage study of all children born in Western Australia (WA) between 1990 and 2009 using deidentified administrative data, resulting in a study sample of 524 534 children. The health data collections used were WA’s Hospital Morbidity Data Collection (HMDC), Mental Health Information System (MHIS), Midwives Notification System, Birth Register and Mortality Register, linked via the WA Data Linkage System. The HMDC contains information on all hospital discharges (public and private hospitals) with corresponding diagnostic information using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) recorded for each episode of care for children from 1990 to June 2013 and their parents from 1970 to June 2013. ICD-8 was used from 1970 to 1978, ICD-9 from 1979 to June 1999, and ICD-10 from July 1999 to 2013. The MHIS contains information on all mental health-related public and private inpatient discharges and public outpatient contacts for children for the period 1990–June 2013 and parents 1970–2009. It identifies the date of the mental health episode as well as the primary diagnostic code using ICD codes as above. The Midwives Notification System and Birth Register were used to identify the birth cohort and contain birth information, including maternal characteristics and infant outcomes for the period 1990–2009.

Mental health diagnostic outcomes were grouped in two ways. The first was a binary indicator of any mental health-related diagnostic code (yes or no). The second was by type of mental health-related diagnosis, with seven groups (listed below) which were non-exclusive (therefore for individuals with one or more diagnoses they could be counted in more than one diagnostic group):

Organic mental disorder.

Substance-related mental and behavioural disorder.

Schizophrenia, and psychoses.

Mood (affective) disorders.

Stress-related disorders.

Personality disorders.

Disorders of psychological development or behavioural and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence.

Mental health-related events included hospital contacts or discharges that were mental health related but did not include a specific mental health diagnosis (for example, self-harm injuries or counselling for mental health-related issues). Any mental health event was an inclusive grouping that combined records of mental health contacts/discharges and diagnoses. Each of these groups was included to capture all mental health-related events including those did not reach the threshold of diagnosis.

The Department of Communities child protection records provided data on children’s entire history of maltreatment allegations from birth onwards. Allegations consist of reports made to Communities regarding alleged child abuse and neglect. An allegation is substantiated by Communities; when following investigation, there is reasonable cause to believe the child has been, is being, or is likely to be abused or neglected or otherwise harmed. Following a substantiated allegation, a child could be removed from their family and placed in out-of-home care.

The child protection data were grouped in several ways. The first was grouping all children based on whether they had any substantiated maltreatment allegations versus no substantiated maltreatment. The second was four levels of child protection contact (no allegations, allegations, substantiated allegations, out-of-home care) where children were included in each level that they had contact and therefore they could be counted more than once across levels (ie, non-exclusive categories). This grouping is used in figure 1 to provide overall prevalence aligned with common child protection categories. The third was four mutually exclusive categories based on the highest level of child protection involvement used for regression modelling of risk associated with each situation:

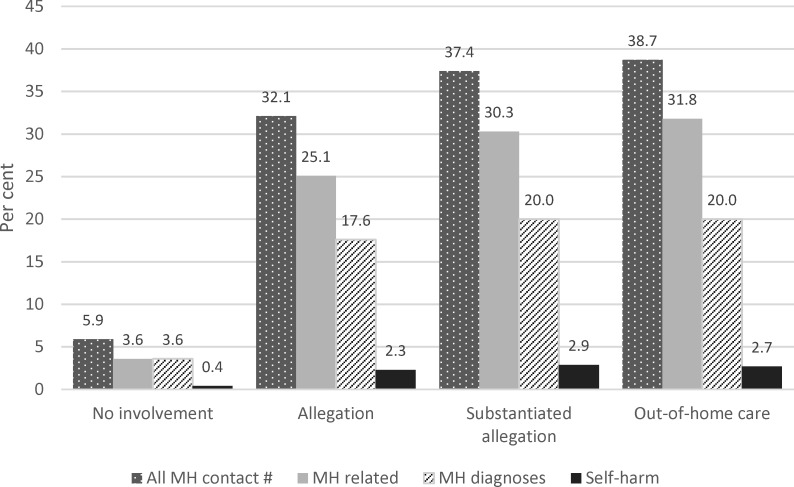

Figure 1.

Percentage of children born in Western Australia between 1990 and 2009 with mental health (MH)-related contacts at any time, by level of child protection involvement. * * Includes MH diagnoses, self-harm and MH-related codes. # Child protection categories were not exclusive and therefore children can be counted more than once across levels of child protection involvement.

No allegations (no allegations have been reported).

Unsubstantiated allegations (an allegation was reported to Communities but following an investigation the allegation was not substantiated.

Substantiated maltreatment allegation (following an investigation the allegation was substantiated).

Out-of-home care (child removed from the home and placed in out-of-home care following a substantiated maltreatment allegation).

The child’s gender, aboriginality, birth weight and gestational age were obtained from Birth Registrations and the Midwives Notification System, along with parents’ marital status and age at the time of birth. Neighbourhood-level socioeconomic status was determined by the Index of Relative Social Disadvantage from the Australian Bureau of Statistics using the Birth and Midwives data.5 Five levels of disadvantage were assigned to census collection districts (approximately 200 households) ranging from 1 (most disadvantaged) to 5 (least disadvantaged). Parents’ hospital contacts for mental health, substance-related issues and assault-related injuries were ascertained from Hospital Morbidity Data and the MHIS.

Patient and public involvement

The children and parents included in the study population were not directly involved in the development of the research questions, study design or the outcome measures. However, our consumer and community reference group provided guidance on our research and findings from this study will be disseminated through this group and the government agencies involved in the study.

Statistical analysis

In addition to descriptive analysis, multivariable Cox regression was used to estimate adjusted and unadjusted HR and 95% CI for the time in months from birth to a mental health contact or diagnosis, with covariates including level of child protection involvement, demographics and family factors. Follow-up time was calculated from birth to first mental health-related event. Children without a mental health-related event or who died before June 2013 were censored. Secondary analyses assessed the associations between level of child protection involvement and different types of mental health outcomes, and between maltreatment type and mental health outcomes. All ICD diagnosis and external codes were checked when ascertaining all the diagnostic outcomes. Only the first occurring mental health outcome was used in each time to event analysis. Due to the large study sample, listwise deletion was used to handle missing values in the regression models. Results in which the 95% CI’s did not include the null value of 1 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were conducted in SAS V.9.3.

Results

Of the 524 534 children in the data, 37 343 (7.1%) had any type of mental health-related event, and 4.3% had a mental health diagnosis. In total, 37.4% of children with substantiated maltreatment had any mental health-related event, compared with 5.9% of children with no child protection contact (figure 1). Likewise, 20% of children with substantiated maltreatment had a mental health diagnosis, compared with 3.6% of children without child protection contact. The percentages of children who had entered out-of-home care and who had any mental health event (38.7%) or a mental health diagnosis (20%) were like those of children with a maltreatment substantiation who did not enter out-of-home care. Children with both mental health events and maltreatment substantiations were more common among families with risk factors, such as living in very disadvantaged neighbourhoods, very young maternal age (<20 years) and parents who were single at the child’s birth (table 1), compared with families without these risk factors.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population by substantiation status and mental health-related contact

| Substantiated allegation, n (col %) | No substantiated allegation, n (col %) | |||||||||||||

| Characteristics | Total, n (col %) | Total | Mental health-related contact | No mental health-related contact | Total | Mental health-related contact | No mental health-related contact | |||||||

| Total | 524 534 | 100 | 11 560 | 100 | 4322 | 100 | 7238 | 100 | 512 974 | 100 | 33 021 | 100 | 479 953 | 100 |

| Gender | ||||||||||||||

| Female | 268 651 | 51.2 | 5472 | 47.3 | 2056 | 47.6 | 3416 | 47.2 | 263 179 | 51.3 | 17 681 | 53.5 | 245 498 | 51.2 |

| Male | 255 831 | 48.8 | 6088 | 52.7 | 2266 | 52.4 | 3822 | 52.8 | 249 743 | 48.7 | 15 332 | 46.4 | 234 411 | 48.8 |

| Missing | 52 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 52 | 0.0 | 8 | 0.0 | 44 | 0.0 |

| Aboriginality | ||||||||||||||

| Non-aboriginal | 492 740 | 93.9 | 7771 | 67.2 | 2563 | 59.3 | 5208 | 72.0 | 484 969 | 94.5 | 27 642 | 83.7 | 457 327 | 95.3 |

| Aboriginal | 31 612 | 6.0 | 3779 | 32.7 | 1754 | 40.6 | 2025 | 28.0 | 27 833 | 5.4 | 5361 | 16.2 | 22 472 | 4.7 |

| Missing | 182 | 0.0 | 10 | 0.1 | 5 | 0.1 | 5 | 0.1 | 172 | 0.0 | 18 | 0.1 | 154 | 0.0 |

| Socioeconomic status | ||||||||||||||

| 1 (Most dis-adv) | 120 565 | 23.0 | 5811 | 50.3 | 2410 | 55.8 | 3401 | 47.0 | 114 754 | 22.4 | 11 761 | 35.6 | 102 993 | 21.5 |

| 2 | 120 126 | 22.9 | 2749 | 23.8 | 920 | 21.3 | 1829 | 25.3 | 117 377 | 22.9 | 7749 | 23.5 | 109 628 | 22.8 |

| 3 | 99 811 | 19.0 | 1550 | 13.4 | 509 | 11.8 | 1041 | 14.4 | 98 261 | 19.2 | 5535 | 16.8 | 92 726 | 19.3 |

| 4 | 94 009 | 17.9 | 923 | 8.0 | 308 | 7.1 | 615 | 8.5 | 93 086 | 18.1 | 4386 | 13.3 | 88 700 | 18.5 |

| 5 (least dis-adv) | 87 330 | 16.6 | 445 | 3.8 | 146 | 3.4 | 299 | 4.1 | 86 885 | 16.9 | 3404 | 10.3 | 83 481 | 17.4 |

| Missing | 2693 | 0.5 | 82 | 0.7 | 29 | 0.7 | 53 | 0.7 | 2611 | 0.5 | 186 | 0.6 | 2425 | 0.5 |

| Parental marital status at birth | ||||||||||||||

| Single | 51 697 | 9.9 | 4000 | 34.6 | 1645 | 38.1 | 2355 | 32.5 | 47 697 | 9.3 | 6119 | 18.5 | 41 578 | 8.7 |

| Married/defacto | 470 751 | 89.7 | 7436 | 64.3 | 2642 | 61.1 | 4794 | 66.2 | 463 315 | 90.3 | 26 797 | 81.2 | 436 518 | 91.0 |

| Missing | 2086 | 0.4 | 124 | 1.1 | 35 | 0.8 | 89 | 1.2 | 1962 | 0.4 | 105 | 0.3 | 1857 | 0.4 |

| Maternal age at birth | ||||||||||||||

| <20 years | 30 019 | 5.7 | 2406 | 20.8 | 1007 | 23.3 | 1399 | 19.3 | 27 613 | 5.4 | 3830 | 11.6 | 23 783 | 5.0 |

| 20–29 years | 252 817 | 48.2 | 6638 | 57.4 | 2482 | 57.4 | 4156 | 57.4 | 246 179 | 48.0 | 18 201 | 55.1 | 227 978 | 47.5 |

| >29 years | 241 642 | 46.1 | 2516 | 21.8 | 833 | 19.3 | 1683 | 23.3 | 239 126 | 46.6 | 10 981 | 33.3 | 228 145 | 47.5 |

| Missing | 56 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 56 | 0.0 | 9 | 0.0 | 47 | 0.0 |

| Paternal age at birth | ||||||||||||||

| <20 years | 9522 | 1.8 | 687 | 5.9 | 245 | 5.7 | 442 | 6.1 | 8835 | 1.7 | 1006 | 3.0 | 7829 | 1.6 |

| 20–29 years | 175 262 | 33.4 | 4649 | 40.2 | 1633 | 37.8 | 3016 | 41.7 | 170 613 | 33.3 | 13 109 | 39.7 | 157 504 | 32.8 |

| >29 years | 314 549 | 60.0 | 3257 | 28.2 | 1072 | 24.8 | 2185 | 30.2 | 311 292 | 60.7 | 14 916 | 45.2 | 296 376 | 61.8 |

| Missing | 25 201 | 4.8 | 2967 | 25.7 | 1372 | 31.7 | 1595 | 22.0 | 22 234 | 4.3 | 3990 | 12.1 | 18 244 | 3.8 |

| Maternal mental health contact | ||||||||||||||

| No | 437 578 | 83.4 | 5407 | 46.8 | 1823 | 42.2 | 3584 | 49.5 | 432 171 | 84.2 | 22 517 | 68.2 | 409 654 | 85.4 |

| Yes | 86 956 | 16.6 | 6153 | 53.2 | 2499 | 57.8 | 3654 | 50.5 | 80 803 | 15.8 | 10 504 | 31.8 | 70 299 | 14.6 |

| Maternal substance contact | ||||||||||||||

| No | 483 384 | 92.2 | 5804 | 50.2 | 1890 | 43.7 | 3914 | 54.1 | 477 580 | 93.1 | 26 602 | 80.6 | 450 978 | 94.0 |

| Yes | 41 150 | 7.8 | 5756 | 49.8 | 2432 | 56.3 | 3324 | 45.9 | 35 394 | 6.9 | 6419 | 19.4 | 28 975 | 6.0 |

| Paternal mental health contact | ||||||||||||||

| No | 477 845 | 91.1 | 8804 | 76.2 | 3306 | 76.5 | 5498 | 76.0 | 469 041 | 91.4 | 27 868 | 84.4 | 441 173 | 91.9 |

| Yes | 46 689 | 8.9 | 2756 | 23.8 | 1016 | 23.5 | 1740 | 24.0 | 43 933 | 8.6 | 5153 | 15.6 | 38 780 | 8.1 |

| Paternal substance contact | ||||||||||||||

| No | 481 103 | 91.7 | 8189 | 70.8 | 3035 | 70.2 | 5154 | 71.2 | 472 914 | 92.2 | 27 925 | 84.6 | 444 989 | 92.7 |

| Yes | 43 431 | 8.3 | 3371 | 29.2 | 1287 | 30.0 | 2084 | 28.8 | 40 060 | 7.8 | 5096 | 15.4 | 34 964 | 7.3 |

Percentages for some variables sum to less than 100% because of missing data.

The HRs from Cox regression analysis, which accounts for time to child’s first mental health event, increased with level of child protection contact (table 2). Univariate results showed that compared with children not involved with child protection, children who had ever entered care had the highest HR for mental health-related events (contacts) (HR: 10.90, 95% CI 10.36 to 11.47), followed by other children with substantiated maltreatment (HR: 6.36, 95% CI 6.01 to 6.73) then children with unsubstantiated maltreatment allegations (HR: 4.46, 95% CI 4.25 to 4.68). After adjusting for background risk factors, the increased hazards were partially attenuated, but remained elevated for all child protection groups, ranging from HR: 3.54 (95% CI 3.28 to 3.82) for children who had entered care to HR: 2.31 (95% CI 2.18 to 2.46) for children with unsubstantiated allegations. For mental health diagnoses, the increased unadjusted hazard ranged from 3.41 (95% CI 3.23 to 3.59) for children with unsubstantiated allegations to 5.86 (95% CI 5.53 to 6.20) for children who entered care. In the multivariate analysis, HRs were partially attenuated but still showed around a twofold increase, ranging from HR: 2.18 (95% CI 2.05 to 2.32) for unsubstantiated allegations to HR: 2.65 (95% CI 2.45 to 2.87) for those who entered care.

Table 2.

Risk of mental health (MH)-related events and diagnoses when exposed to different levels of child protection involvement

| Any MH event | MH-related event | MH diagnosis | ||||

| Characteristics | Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate |

| HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI)* | HR (95% CI)* | HR (95% CI)* | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI)* | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 0.93 (0.91 to 0.95) | 0.92 (0.90 to 0.94) | 1.10 (1.08 to 1.13) | 1.11 (1.08 to 1.15) | 0.86 (0.84 to 0.88) | 0.84 (0.82 to 0.87) |

| Male | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Aboriginality | ||||||

| Non-aboriginal | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Aboriginal | 4.20 (4.08 to 4.33) | 1.65 (1.58 to 1.73) | 6.26 (6.05 to 6.48) | 2.21 (2.10 to 2.32) | 2.03 (1.94 to 2.12) | 0.95 (0.89 to 1.01) |

| Socioeconomic status (SES) | ||||||

| 1 (Most dis-adv) | 2.63 (2.53 to 2.73) | 1.38 (1.32 to 1.44) | 3.26 (3.10 to 3.42) | 1.46 (1.38 to 1.55) | 1.96 (1.87 to 2.06) | 1.24 (1.17 to 1.30) |

| 2 | 1.62 (1.56 to 1.69) | 1.20 (1.15 to 1.25) | 1.74 (1.65 to 1.83) | 1.22 (1.16 to 1.29) | 1.51 (1.44 to 1.59) | 1.17 (1.11 to 1.23) |

| 3 | 1.37 (1.31 to 1.43) | 1.13 (1.08 to 1.18) | 1.40 (1.32 to 1.48) | 1.12 (1.06 to 1.19) | 1.30 (1.23 to 1.37) | 1.11 (1.05 to 1.17) |

| 4 | 1.21 (1.15 to 1.26) | 1.09 (1.04 to 1.14) | 1.23 (1.16 to 1.30) | 1.09 (1.03 to 1.16) | 1.18 (1.12 to 1.25) | 1.07 (1.01 to 1.13) |

| 5 (least dis-adv) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Parental marital status at birth | ||||||

| Single | 2.48 (2.42 to 2.55) | 1.16 (1.11 to 1.20) | 2.80 (2.71 to 2.89) | 1.16 (1.11 to 1.22) | 2.12 (2.05 to 2.20) | 1.15 (1.10 to 1.21) |

| Married/defacto | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Maternal age at birth | ||||||

| <20 years | 3.14 (3.03 to 3.25) | 1.24 (1.18 to 1.31) | 3.87 (3.71 to 4.03) | 1.28 (1.19 to 1.37) | 2.39 (2.28 to 2.50) | 1.18 (1.10 to 1.26) |

| 20–29 years | 1.44 (1.40 to 1.47) | 1.06 (1.03 to 1.09) | 1.53 (1.49 to 1.58) | 1.06 (1.02 to 1.11) | 1.33 (1.29 to 1.36) | 1.05 (1.01 to 1.09) |

| >29 years | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Paternal age at birth | ||||||

| <20 years | 2.69 (2.54 to 2.86) | 0.97 (0.89 to 1.04) | 3.38 (3.15 to 3.62) | 0.98 (0.89 to 1.08) | 2.04 (1.89 to 2.22) | 0.95 (0.86 to 1.05) |

| 20–29 years | 1.47 (1.44 to 1.51) | 1.08 (1.05 to 1.12) | 1.56 (1.52 to 1.61) | 1.08 (1.04 to 1.12) | 1.38 (1.34 to 1.42) | 1.08 (1.05 to 1.12) |

| >29 years | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Maternal MH contact | ||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 2.86 (2.80 to 2.94) | 1.89 (1.84 to 1.95) | 2.84 (2.75 to 2.93) | 1.69 (1.62 to 1.75) | 3.00 (2.91 to 3.09) | 2.15 (2.08 to 2.23) |

| Maternal substance contact | ||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 3.74 (3.64 to 3.85) | 1.42 (1.36 to 1.47) | 4.58 (4.43 to 4.74) | 1.55 (1.48 to 1.62) | 2.85 (2.75 to 2.95) | 1.27 (1.21 to 1.33) |

| Paternal MH contact | ||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 2.00 (1.94 to 2.06) | 1.42 (1.37 to 1.47) | 1.97 (1.90 to 2.04) | 1.35 (1.29 to 1.41) | 2.14 (2.06 to 2.22) | 1.56 (1.49 to 1.63) |

| Paternal substance contact | ||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 2.24 (2.17 to 2.30) | 1.30 (1.25 to 1.35) | 2.51 (2.42 to 2.60) | 1.39 (1.33 to 1.45) | 1.98 (1.91 to 2.06) | 1.20 (1.14 to 1.26) |

| Child protection involvement | ||||||

| No involvement | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Unsubstantiated allegation | 3.98 (3.82 to 4.15) | 2.24 (2.13 to 2.36) | 4.46 (4.25 to 4.68) | 2.31 (2.18 to 2.46) | 3.41 (3.23 to 3.59) | 2.18 (2.05 to 2.32) |

| Substantiated allegation | 5.34 (5.09 to 5.61) | 2.71 (2.55 to 2.89) | 6.36 (6.01 to 6.73) | 2.84 (2.63 to 3.05) | 4.28 (4.02 to 4.55) | 2.69 (2.49 to 2.90) |

| Substantiated allegation and entered out-of-home care |

8.45 (8.07 to 8.85) | 3.03 (2.83 to 3.24) | 10.90 (10.36 to 11.47) | 3.54 (3.28 to 3.82) | 5.86 (5.53 to 6.20) | 2.65 (2.45 to 2.87) |

*All other covariates included (aboriginality, gender, SES, parent marital status at birth, maternal age at birth, paternal age at birth, maternal MH contact, maternal substance-related contact, paternal MH contact, paternal substance-related contact).

In addition to maltreatment, all background risk factors were associated with increased risk of mental health events and/or diagnosis. Most notably, compared with non-aboriginal young people, aboriginal young people had a higher risk of mental health-related events (HR: 6.26, 95% CI 6.05 to 6.48) unadjusted, although this was partially attenuated in the multivariate analysis (HR: 2.21, 95% CI 2.10 to 2.32). For mental health diagnosis, however, the increased risk for aboriginal young people was fully attenuated in the multivariate model. Young maternal age and living in the most socially disadvantaged neighbourhoods were both also associated with more than a threefold unadjusted increased risk for a mental health-related event (HR: 3.87, 95% CI 3.71 to 4.03) and HR: 3.26 (95% CI 3.10 to 3.42), respectively, and around a twofold increased risk for a mental health diagnosis.

Maternal mental health hospital contacts had one of the highest HRs for young people’s likelihood of a mental health diagnosis (HR: 3.00, 95% CI 2.91 to 3.09) unadjusted, which was partially attenuated in the multivariate analysis but still associated with a doubled HR (HR: 2.15, 95% CI 2.08 to 2.23). Maternal substance abuse hospital contacts were associated with a similar increased risk for a mental health diagnosis (HR: 2.85, 95% CI 2.75 to 2.95), however after adjusting for other risk factors was reduced to HR: 1.27 (95% CI 1.21 to 1.33).

Further analysis examined the risk of different types of mental health diagnoses associated with child protection histories (table 3). Compared with individuals without a maltreatment substantiation, an increased risk was found across all MH diagnostic categories, with adjusted HRs in the twofold–threefold increased range. The risk for those with any substantiated maltreatment of having a personality disorder diagnosis was particularly high, at HR: 6.83 (95% CI 5.81 to 8.04) unadjusted and HR: 3.64 (95% CI 2.94 to 4.52) adjusted, compared with those without substantiated maltreatment. For the subgroup with a substantiation and out-of-home care placement, the increased likelihood of being diagnosed with a personality disorder was even higher at HR: 12.63 (95% CI 10.26 to 15.55) unadjusted and still showed a large increase in risk after adjusting for other risk factors HR: 6.82 (95% CI 5.12 to 9.08).

Table 3.

Risk of mental health (MH) diagnosis types for children by level of child protection involvement

| Characteristic | Organic mental disorder | Substance-related mental and behavioural disorder | Schizophrenia and psychoses | Mood (affective) disorder | ||||

| Univariate OR (95% CI) |

Multivariate OR (95% CI)* |

Univariate OR (95% CI) | Multivariate OR (95% CI)* |

Univariate OR (95% CI) |

Multivariate OR (95% CI)* |

Univariate OR (95% CI) |

Multivariate OR (95% CI)* |

|

| Child protection involvement† | ||||||||

| No involvement | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Unsubstantiated allegation | 2.12 (1.54 to 2.92) | 1.61 (1.09 to 2.38) | 4.09 (3.74 to 4.47) | 2.05 (1.83 to 2.31) | 3.18 (2.42 to 4.18) | 1.93 (1.37 to 2.72) | 3.48 (3.15 to 3.85) | 2.29 (2.02 to 2.58) |

| Substantiated allegation | 2.61 (1.76 to 3.88) | 2.35 (1.50 to 3.68) | 4.71 (4.21 to 5.27) | 2.29 (1.98 to 2.65) | 4.59 (3.41 to 6.18) | 2.82 (1.94 to 4.10) | 4.40 (3.90 to 4.96) | 2.81 (2.43 to 3.25) |

| Substantiated allegation and entered out-of-home care | 5.80 (4.12 to 8.17) | 4.25 (2.64 to 6.83) | 8.98 (7.98 to 10.11) | 2.87 (2.43 to 3.38) | 8.40 (6.17 to 11.42) | 3.03 (1.93 to 4.75) | 5.09 (4.40 to 5.89) | 2.43 (2.01 to 2.94) |

| Substantiated allegation† | ||||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 3.69 (2.83 to 4.82) | 2.85 (2.03 to 4.01) | 5.50 (5.05 to 5.99 | 2.16 (1.92 to 2.42) | 5.43 (4.34 to 6.78) | 2.56 (1.87 to 3.50) | 4.23 (3.85 to 4.66) | 2.28 (2.01 to 2.58) |

| Characteristic | Stress-related disorder | Personality disorder | Disorders of childhood and psychological development | |||

| Univariate OR (95% CI) |

Multivariate OR (95% CI)* |

Univariate OR (95% CI) |

Multivariate OR (95% CI)* |

Univariate OR (95% CI) |

Multivariate OR (95% CI)* |

|

| Child protection involvement† | ||||||

| No involvement | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Unsubstantiated allegation | 3.99 (3.73 to 4.26) | 2.62 (2.41 to 2.84) | 4.44 (3.66 to 5.39) | 3.07 (2.43 to 3.87) | 4.00 (3.74 to 4.28) | 2.82 (2.59 to 3.06) |

| Substantiated allegation | 5.04 (4.65 to 5.46) | 3.29 (2.98 to 3.62) | 5.22 (4.14 to 6.59) | 3.40 (2.56 to 4.50) | 4.14 (3.78 to 4.54) | 2.95 (2.64 to 3.29) |

| Substantiated allegation and entered out-of-home care | 7.46 (6.84 to 8.14) | 3.52 (3.14 to 3.96) | 12.63 (10.26 to 15.55) | 6.82 (5.12 to 9.08) | 7.16 (6.57 to 7.80) | 3.72 (3.30 to 4.19) |

| Substantiated allegation† | ||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 5.35 (5.04 to 5.68) | 2.77 (2.56 to 3.01) | 6.83 (5.81 to 8.04) | 3.64 (2.94 to 4.52) | 4.84 (4.53 to 5.16) | 2.64 (2.42 to 2.87) |

*All other covariates included (aboriginality, gender, socioeconomic status, parent marital status at birth, maternal age at birth, paternal age at birth, maternal MH contact, maternal substance-related contact, paternal MH contact, paternal substance-related contact).

†Separate Cox regression models, second model compares all children with substantiated allegations (including those who entered out-of-home care) to all children without substantiated allegations (including no contact or only unsubstantiated allegations).

Comorbidity of substance-related disorders with other mental and behavioural disorders is common, and table 4 shows the increased risk of mood and stress disorders, respectively, with and without comorbid substance-related disorders. The increased risk of comorbid disorders among those with a history of substantiated maltreatment is even higher than the increased risk for a single diagnosis. For stress-related disorders, the increased risk for a single diagnosis for young people who have any maltreatment substantiation is HR: 4.82 (95% CI 4.50 to 5.15) unadjusted compared with HR: 7.90 (95% CI 6.90 to 9.04) unadjusted for comorbid stress and substance-related diagnoses. Young people who have a substantiation and have entered care appear particularly vulnerable to this type of comorbidity, with an unadjusted HR: 14.06 (95% CI 11.81 to 16.75) for comorbid stress and substance-related diagnoses compared with around sixfold increased likelihood of either disorder. Even after adjusting for other risk factors, young people who had been in care had a fourfold increased likelihood of comorbid stress and substance-related diagnoses (HR: 4.61, 95% CI 3.57 to 5.94). Young people who had been in care were also at elevated risk for mood and substance-related disorders (HR: 8.80, 95% CI 6.86 to 11.29) unadjusted and HR: 3.03 (95% CI 2.14 to 4.31) adjusted compared with those with no child protection involvement.

Table 4.

Risk of comorbid mood and substance-related mental and behavioural disorders for children by level of child protection involvement

| Characteristic | Mood (affective) disorder* | Substance-related mental and behavioural disorder† | Mood and substance-related mental and behavioural disorder | |||

| Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | |

| HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI)‡ | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI)‡ | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI)‡ | |

| Child protection involvement§ | ||||||

| No Involvement | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Unsubstantiated allegation | 3.18 (2.83 to 3.57) | 2.21 (1.92 to 2.54) | 3.92 (3.55 to 4.34) | 1.92 (1.68 to 2.19) | 4.54 (3.75 to 5.51) | 2.52 (1.97 to 3.22) |

| Substantiated allegation | 3.81 (3.31 to 4.40) | 2.56 (2.16 to 3.03) | 4.23 (3.71 to 4.82) | 1.95 (1.64 to 2.31) | 6.45 (5.17 to 8.04) | 3.60 (2.73 to 4.73) |

| Substantiated allegation and entered out-of-home care | 4.05 (3.38 to 4.86) | 2.20 (1.75 to 2.77) | 8.59 (7.54 to 9.77) | 2.71 (2.26 to 3.26) | 8.80 (6.86 to 11.29) | 3.03 (2.14 to 4.31) |

| Substantiated allegation§ | ||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 3.59 (3.20 to 4.03) | 2.10 (1.82 to 2.43) | 5.13 (4.66 to 5.65) | 1.96 (1.71 to 2.23) | 6.39 (5.38 to 7.58) | 2.78 (2.19 to 3.53) |

| Characteristic | Stress-related disorders* | Substance-related mental and behavioural disorder† | Stress and substance-related mental and behavioural disorder | |||

| Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | |

| HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI)‡ | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI)‡ | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI)‡ | |

| Child protection involvement§ | ||||||

| No involvement | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Unsubstantiated allegation | 3.75 (3.49 to 4.03) | 2.61 (2.39 to 2.84) | 3.62 (3.25 to 4.03) | 1.83 (1.59 to 2.11) | 5.14 (4.40 to 6.00) | 2.54 (2.07 to 3.12) |

| Substantiated allegation | 4.72 (4.32 to 5.16) | 3.23 (2.90 to 3.59) | 3.98 (3.46 to 4.57) | 1.86 (1.56 to 2.23) | 6.48 (5.36 to 7.83) | 3.34 (2.62 to 4.27) |

| Substantiated allegation and entered out-of-home care | 6.29 (5.70 to 6.94) | 3.24 (2.85 to 3.69) | 6.35 (5.43 to 7.41) | 1.97 (1.60 to 2.44) | 14.06 (11.81 to 16.75) | 4.61 (3.57 to 5.94) |

| Substantiated allegation§ | ||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 4.82 (4.50 to 5.15) | 2.67 (2.44 to 2.91) | 4.35 (3.91 to 4.84) | 1.68 (1.45 to 1.94) | 7.90 (6.90 to 9.04) | 3.12 (2.57 to 3.78) |

*Excludes comorbid substance-related mental and behavioural disorders.

†Excludes mood (affective) disorders.

‡All other covariates included (aboriginality, gender, socioeconomic status, parent marital status at birth, maternal age at birth, paternal age at birth, maternal mental health (MH) contact, maternal substance-related contact, paternal MH contact, paternal substance-related contact).

§Separate Cox regression models, second model compares all children with substantiated allegations (including those who entered out-of-home care) to all children without substantiated allegations (including no contact or only unsubstantiated allegations).

All maltreatment types were associated with elevated risk, with similar levels of increased risk across maltreatment types. In the univariate analysis, each of the maltreatment types was associated with an increased risk for a mental health-related event (ranging from HR 5.45 (95% CI 5.23 to 5.69) for sexual abuse to HR 7.60 (95% CI 7.27 to 7.94) for neglect. In the multivariate analysis, increased risk of a mental health-related event ranged from HR 2.04 (95% CI 1.86 to 2.24) for emotional abuse to HR 2.58 (95% CI 2.44 to 2.73) for sexual abuse (online supplementary table S1).

bmjopen-2019-029675supp001.pdf (42.9KB, pdf)

To assess the possibility that children placed in out-of-home care may be receiving services earlier and more routinely because of entry into care, we examined time to mental health contact following the first substantiation. The average time from first substantiation to any mental health event was similar at 64 months for all children and 66.5 months for those who entered out-of-home care. As the data only provided the dates service use occurred, we cannot be certain whether maltreatment occurred before mental health symptoms developed. Three quarters (73%) of young people with both mental health contact and maltreatment substantiations had the first recorded maltreatment occur prior to the first recorded mental health contact.

Discussion

Only 3.6% of children without child protection contact in WA had a mental health diagnosis, compared with 20% of children with substantiated maltreatment. This significantly increased risk for mental health diagnoses and events is consistent with other studies looking at child welfare or maltreated populations3 4 and shows the need to support the mental health of children and young people with a history of maltreatment. We found that increased risk for mental health events and diagnosis was common across children with different maltreatment histories, levels of child protection and across different types of mental health diagnosis; however, there were marked differences in risk.

Children with a mental health-related contact were more likely than other children to also have parents with a history of mental health contacts. This may reflect both genetic and environmental factors.6 7 Parenting capacity can be affected by mental illness, with previous research showing that maternal mental illness is associated with increased risk of child maltreatment.8 After controlling for sociodemographic factors and child protection involvement, maternal mental health contacts were still associated with around a twofold increased risk of mental health events and diagnoses among young people. This represented one of the factors associated with the highest increased risk among our many risk factors.

Both mental health events and maltreatment substantiations were more common in disadvantaged neighbourhoods, teenage mothers and parents who were single at the child’s birth. This is consistent with previous research3 and highlights the way social determinants and adverse outcomes tend to cluster together creating problems that are complex to resolve at an individual or societal level. It also highlights the importance of accounting for multiple risk factors when examining the relationship between maltreatment and mental health outcomes.

Aboriginal young people had a higher risk only for mental health events, but not for diagnoses, within the multivariate models. Possible explanations could be not reaching the threshold of diagnoses, concerns about the cultural appropriateness of diagnoses or lack of psychiatric services in rural and remote areas therefore not getting a diagnosis.

Despite controlling for background adversity and parental mental health hospital contacts, we found that maltreated children were at significantly increased risk of mental health outcomes and diagnoses. Our study is congruent with previous research showing an increased risk of mental health problems and service use in child protection/maltreated samples; however, we found the association held across many diagnostic groups such as schizophrenia, which has had mixed results in previous studies (eg, in smaller population study by Spataro et al,9 the relative risk for schizophrenia associated with child maltreatment did not reach significance, whereas Vinnerljung et al 4 found elevated rates of psychosis (which includes schizophrenia) among their out-of-home care groups that were comparable to our findings for maltreated children although somewhat lower than for our out-of-home care group).

The greatest increased risk was for personality disorder, with a 7-fold increased likelihood among children with any maltreatment, and 12-fold increased likelihood among maltreated children who entered care (prior to adjusting for other risk factors). The increase was still sizeable after controlling for background risk. Personality disorder was not included in previous large-scale studies such as Vinnerljung et al,4 with many studies focussing on common and easy to measure disorders such as depression and anxiety. Smaller prior studies have found personality disorders to be more common among people who had experienced child maltreatment,9–11 but have tended to be limited to specific disorders (borderline personality disorder11 and antisocial personality disorder10) or maltreatments types (sexual abuse9 11) and results have not always been consistent in multivariate models.10 The present study suggests young people who have been maltreated may be particularly susceptible to developing personality disorders. Trauma and disrupted attachments as often occur for abused or neglected children are widely believed to contribute to the development of personality disorders.12–14 To date, the treatment of personality disorders has only been modestly successful, reducing symptoms such as self-harm, but often social, vocational and quality-of-life impairments remain, and a long-term approach is recommended.15

While not significantly different across all comparisons, we found higher likelihood of mental health events and diagnoses among young people with higher levels of child protection contact. We are not aware of any studies examining mental health outcomes across all four child protection groups (no child protection contact, only unsubstantiated allegations, substantiated allegations and substantiated allegations with placement in out-of-home care). Vinnerljung et al 4 compared child welfare clients that remained at home and those placed in out-of-home care with the general population, with both child welfare groups showing similarly elevated rates for various mental health outcomes. Among a younger cohort, Hussey et al found that outcomes were equally poor for children with unsubstantiated maltreatment as substantiated maltreatment.16 Our results showed a general tendency for higher mental health risks associated with higher levels of child protection involvement, however were congruent with the finding that children with maltreatment allegations were at an increased risk for mental health diagnoses. Mental health support needs to be made available for children and young people with maltreatment allegations, regardless of whether their case is substantiated and if they enter out-of-home care. This should be used in conjunction with services to parents to improve child safety and family functioning to prevent children from developing mental health issues.

Our study also included all four maltreatment types (neglect, physical, sexual and emotional abuse), and found an increased risk of mental health events across all maltreatment types. This differs slightly from Fergusson’s study that showed much more consistent results for sexual abuse than physical abuse after adjusting for other risk factors.3 Our study also found similar mental health outcomes for children who had been neglected, physically or emotionally abused, which have not received the same level of research attention. Sexual abuse is often singled out as a risk factor for poor mental health outcomes. Our results showed that while young people who had been sexually abused had the highest HR for mental health diagnoses, all maltreatment types had an elevated risk. However, only one alleged maltreatment type was supplied in the data per investigation, so children experiencing multiple maltreatment types cannot be identified in this study. Regardless of the abuse type identified in the child protection database, all children with substantiated maltreatment should be provided with access to mental health services as required.

A limitation of our study is that it only captures public outpatient and public and private hospital inpatient mental health events: data on outpatient mental health services provided by private hospitals, private psychologists/psychiatrists or managed by general practitioners (family doctors) were not available. As a result, mental health service use is better captured for more severe mental health problems where inpatient admissions occur. Although this may be a potential source of bias in our model estimates, these groups are likely to represent the heaviest users of government mental health services, and those most in need. A further issue in using service data to examine mental health outcomes is that accessing services for mental health is both an indicator of an adverse outcome (mental health issues) and a positive indicator that some service needs are being met. It also constitutes a measure of services provided or the service burden associated with subgroups of the population. Diagnoses are a somewhat better indicator of mental health status, but rates may still be affected by different levels of service use—underascertainment of mental health disorders may be present for any or groups within the study if an individual does not access mental health services. Other limitations include uncertainty around the true start date of an individual’s mental health symptoms or maltreatment, so it is possible that in some cases the order of events differs from that suggested by their recorded service use.

Despite these limitations, the study had many strengths and provided significant new information regarding the mental health of children in contact with the child protection. Linked population data allow the examination of sensitive topics without the recruitment and sample loss challenges that affect many surveys. The study included a population cohort of children, with data from birth to young adulthood, and accounting for parents’ mental health and a range of background adversities. The data enabled our study to build on previous research by detailed examination of the increased risk of mental health problems among subgroups within the child protection system, including those with different levels of child protection involvement, and different maltreatment types, and identifying the level of increased risk for different mental health diagnoses.

Our findings highlight a failure in the responsiveness of the child protection system as a whole to assist children with mental health issues, especially as evidenced by an average time of 5 years between a child’s first maltreatment substantiation and access to a service. We acknowledge though that children may be involved in child protection at a young age and therefore mental health issues may take time to appear. However, we would argue that given the trauma and adverse social circumstances these children experience, mental service provision should be addressed and seen as a priority, and this may be an opportunity to provide earlier interventions for better outcomes.

Previous research showing high levels of mental health service needs among the child protection population is supported by the results of this study. An increased risk was found across all subgroups, regardless of what type of maltreatment the child’s record showed, and whether maltreatment was substantiated, although children with higher levels of child protection involvement were also at greater risk for mental health events and diagnoses. The strongly increased risk for personality disorders, and comorbid substance and mental health disorders highlights a need for targeted plans to reduce or treat these challenging mental health issues that can severely impact on young people’s well-being and ability to adjust to independent adult life.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the partnership of the Western Australian Government Departments of Health, Communities, Education, and Justice which provided data for this project. They thank the Data Linkage Branch of the Department of Health for linking the data.

Footnotes

Contributors: MJM drafted the paper, interpreted findings and revised the paper. SAS cleaned and analysed the data, contributed to the draft and revised the paper. MO conceptualised the paper, developed the statistical plan, contributed to the draft and revised the paper. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: MOD was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Early Career Fellowship (1012439). This research was also supported by an Australian Research Council Linkage Project Grant (LP100200507) and an Australian Research Council Discovery Grant (DP110100967).

Disclaimer: The views expressed are not necessarily those of the Government Departments that have provided data for this project and any omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Western Australian Department of Health Human Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available. Third party restrictions are in place for legal and ethical reasons. The data used in this paper are owned by our respective Government Departments and therefore would require permissions by these departments for others to access.

References

- 1. Kaplan SJ, Pelcovitz D, Labruna V. Child and adolescent abuse and neglect research: a review of the past 10 years. Part I: physical and emotional abuse and neglect. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999;38:1214–22. 10.1097/00004583-199910000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. National Scientific Council on the Developing Child Cambridge MCotDC, Harvard University. The science of neglect: the persistent absence of responsive care disrupts the developing brain: working paper 12. Cambridge: MA Center on the Developing Child, Harvard University, (2012).Cambridge, MA Center on the Developing Child, Harvard University, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. Exposure to childhood sexual and physical abuse and adjustment in early adulthood. Child Abuse Negl 2008;32:607–19. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vinnerljung B, Hjern A, Lindblad F. Suicide attempts and severe psychiatric morbidity among former child welfare clients--a national cohort study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2006;47:723–33. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01530.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Australian Bureau of Statistics Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA) - Technical Paper. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kendler KS, Walters EE, Neale MC, et al. The structure of the genetic and environmental risk factors for six major psychiatric disorders in women. phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, bulimia, major depression, and alcoholism. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995;52:374–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Etain B, Henry C, Bellivier F, et al. Beyond genetics: childhood affective trauma in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 2008;10:867–76. 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2008.00635.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. O'Donnell M, Maclean MJ, Sims S, et al. Maternal mental health and risk of child protection involvement: mental health diagnoses associated with increased risk. J Epidemiol Community Health 2015;69:1175–83. 10.1136/jech-2014-205240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Spataro J, Mullen PE, Burgess PM, et al. Impact of child sexual abuse on mental health: prospective study in males and females. Br J Psychiatry 2018;184:416–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Horwitz AV, Widom CS, McLaughlin J, et al. The impact of childhood abuse and neglect on adult mental health: a prospective study. J Health Soc Behav 2001;42:184–201. 10.2307/3090177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hillberg T, Hamilton-Giachritsis C, Dixon L. Review of meta-analyses on the association between child sexual abuse and adult mental health difficulties: a systematic approach. Trauma Violence Abuse 2011;12:38–49. 10.1177/1524838010386812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Paris J. Childhood Adversities and Personality Disorders : Livesley WJ, Larstone R, Handbook of personality disorders: theory, research and treatment. 2nd edn New York: The Guildford Press, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fonagy P, Luyten P. Attachment, Mentalising and the Self : Livesley WJ, Larstone R, Handbook of personality disorders: theory, research and treatment. 2nd edn New York: The Guildford Press, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Infurna MR, Brunner R, Holz B, et al. The specific role of childhood abuse, parental bonding, and family functioning in female adolescents with borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord 2016;30:177–92. 10.1521/pedi_2015_29_186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bateman AW, Gunderson J, Mulder R. Treatment of personality disorder. The Lancet 2015;385:735–43. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61394-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hussey JM, Marshall JM, English DJ, et al. Defining maltreatment according to substantiation: distinction without a difference? Child Abuse Negl 2005;29:479–92. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-029675supp001.pdf (42.9KB, pdf)