Abstract

Introduction

Chronic neck pain is a challenging condition to treat in clinical practice and has a considerable impact on quality of life and disability. According to the theory of traditional Chinese medicine, acupoints and tender points may become sensitised when the body is in a diseased state. Stimulation of such sensitive points may lead to disease improvement and improved clinical efficacy. This study aims to evaluate the efficacy and safety of needling at sensitive acupoints in providing pain relief, improvement of cervical vertebral function and quality of life in patients with chronic neck pain.

Methods and analysis

This multicentre, randomised controlled, explanatory and parallel clinical trial will include 716 patients with chronic neck pain. Study participants will be randomly assigned in a 1:1:1:1 ratio to four treatment groups: the highly sensitive acupoints group, low/non-sensitive acupoints group, sham acupuncture group and waiting-list control group. The primary outcome will be the change in the visual analogue scale score for neck pain from baseline to 4 weeks. Secondary outcomes will be the Northwick Park Neck Pain Questionnaire and McGill pain questionnaire, 12-item Short-Form health survey, Neck Disability Index, changes in the pressure pain threshold, range of cervical motion, Self-Rating Anxiety Scale, Self-Rating Depression Scale and adverse events before treatment, post-treatment, and at 4, 8, 12, 16 and 20 weeks post-treatment. The intention-to-treat approach will be used in the statistical analysis. Group comparisons will be undertaken using χ2 tests for categorical characteristics, and analysis of variance for continuous variables to analyse whether acupuncture in the highly sensitive acupoints group achieves better treatment outcomes than in each of the other three groups.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval of this study has been granted by the local Institutional Review Board (ID: 2017 KL-038). The outcomes of the trial will be disseminated through peer-reviewed publications.

Trial registration number

ChiCTR1800016371; Pre-results.

Keywords: acupuncture, sensitised points, chronic neck pain, study protocol, pressure pain threshold

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study will be the first randomised controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of acupuncture at sensitive points in patients with chronic neck pain.

To test the efficacy of acupuncture at sensitive acupoints, the trial will include four groups (highly sensitive acupoints group, low/non-sensitive acupoints acupuncture group, sham acupuncture group and waiting-list control group), and strict quality control will be conducted, including adequate concealment of randomised group allocations.

A sham acupuncture group will be used to investigate the placebo effect of acupuncture.

A limitation of this trial is that although there are several types of point sensitisation, such as pain and heat, we will only be quantifying pain as an indicator of sensitisation.

Introduction

Chronic neck pain can be caused by dysfunction of various structures in the neck, and it can manifest as episodic pain and/or stiffness.1 2 The prevalence of neck pain in the adult general population reportedly varies from 30% to 50% worldwide.3 Furthermore, neck pain-related diseases, such as cervical spondylosis, occur in 65% of subjects working in certain occupations in China.4 Neck pain is the third most common chronic condition causing persistent pain in the USA and the fourth leading cause of disability worldwide.5 6 Chronic neck pain can lead to work absenteeism or a heavy medical burden.7 The mean annual total costs accrued by patients with neck pain in the USA are US$8512, which is 182% higher than the costs of the general population.8 Several risk factors predispose to the development of chronic neck pain, including obesity, a sedentary lifestyle, previous neck pain, cervical disc degeneration and poor general health. The current mainstay of treatment for chronic neck pain is non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, but they are associated with many adverse reactions, such as gastrointestinal, cardiac and renal toxicity.9

Although clinical trials have suggested that acupuncture can effectively relieve chronic neck pain,10 the effect of acupuncture treatment is closely related to the selection of acupoints.11 One study evaluating the effects of acupuncture on chronic neck pain showed that acupuncture at common distant acupoints is more effective than that at myofascial trigger points,12 while another study found that acupuncture at local myofascial trigger points also has a good analgesic effect.13 However, some studies have also reported that acupuncture does not relieve pain.14–16 Despite the increasing amount of randomised clinical trials (RCTs) investigating the effect of acupuncture, the quality of these RCTs needs to be improved, as many include inadequate sample sizes,17 short follow-up,18 an absence of sham acupuncture and non-treatment as control treatments,19 no objective assessment method20 or a lack of individualised treatment based on each patient’s condition.21 Consequently, the efficacy of acupuncture for chronic neck pain needs further evaluation due to the lack of objective clinical evidence.

The pressure pain threshold (PPT) is a semiobjective method used to quantify localised pain.22 23 Clinical studies have confirmed that the sensitivity (PPT) at acupoints changes when patients are in a diseased state, such as shoulder pain,24 knee osteoarthritis,25 primary dysmenorrhea26 and premenstrual syndrome.27 The degree of change in the PPT may objectively reflect the intensity of acupoint sensitisation and it may be related to the disease status.28 Clinical studies have found that performing acupuncture at sensitive points achieves a superior effect.29 30 However, these studies did not quantify the sensitivity of the points, which undermines the validity of the results. Consequently, the improvement in clinical efficacy may not have been optimised. Clinical trials have recently investigated the efficacy of acupuncture at objectively evaluated sensitive points.31 This will further reveal the relationship between objectively evaluated sensitive points and improved clinical efficacy. However, no study has yet focused on the efficacy of acupuncture at quantified sensitive points for the treatment of chronic neck pain. Therefore, we herein describe the protocol for an RCT that aims to evaluate the efficacy of acupuncture at sensitive points (acupoints or tender points) in relieving neck pain and improving cervical vertebral function and quality of life.

Methods and analysis

Objective

To assess the efficacy and safety of acupuncture at highly sensitive acupoints in relieving pain and improving the cervical vertebral function and quality of life in patients with chronic neck pain.

Trial design

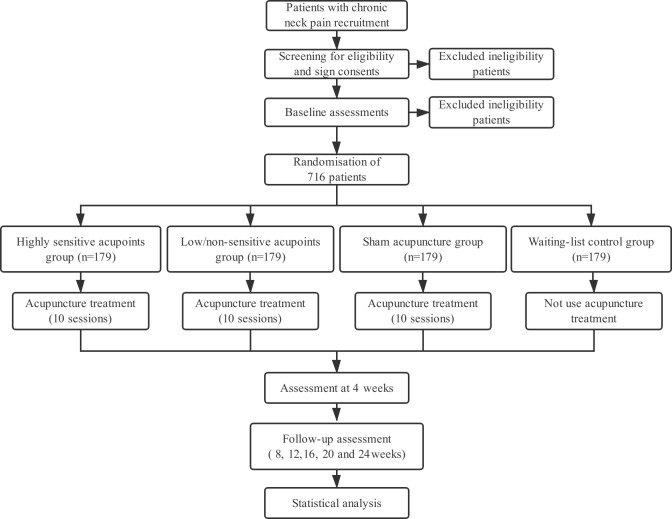

This is a prospective, multicentre RCT in which patients will be allocated to four parallel treatment groups using a 1:1:1:1 allocation ratio. The protocol was developed in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials guidelines32 and the Standards for Reporting Interventions in Clinical Trials of Acupuncture guidelines.33 The trial has been registered with ChiCTR at Current Controlled Trials. A flowchart of the trial design is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the trial design.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria will be: (1) men or women aged 18–75 years; (2) neck pain or limited cervical activity as the main complaint; (3) neck pain or discomfort visual analogue scale (VAS) score of ≥30 for at least 5 days within 1 week; (4) chronic neck pain for the last 3 months and (5) provision of written informed consent for all procedures in this trial.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with any one of the following criteria will be excluded: (1) history of neck fracture or surgery, or cervical congenital abnormality; (2) serious disease related to the heart, liver, kidney or haematopoietic system; (3) difficulty in answering the questionnaires because of cognitive impairment; (4) dermatopathy and haemorrhagic diseases; (5) those who are pregnant, breastfeeding or planning a pregnancy during the study period and (6) participation in other trials.

Recruitment strategies and randomisation

We will enrol patients from the outpatient departments of Acupuncture and Moxibustion, and Orthopaedics in four clinical centres in China: Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shaanxi University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shanxi University of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Guiyang College of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Recruitment strategies will include posting recruitment advertisements on social media (such as WeChat, which is similar to Facebook) and at community centres. Patients who consent to study participation will be examined by orthopaedists who will make a diagnosis; a research assistant (RA) will then perform a baseline evaluation. The RA will apply for the grouping randomisation after completing the PPT measurement.

Central randomisation will be performed using stratified and permuted blocks. The RAs will be registered in the randomisation centre (located in Brightech-Magnsoft Data Services Company) and will be trained to apply for randomisation through the online website. This guarantees that randomisation concealment is adequate. Patients will be randomised in blocks of varying size within each site, stratified by sex and course of disease.

Blinding

The RA will be responsible for baseline evaluation, PPT measurement and randomisation. The acupuncture treatments will be performed by acupuncturists, each held a practitioners license for more than 5 years. The efficacy of acupuncture will be evaluated by an assessor. Patients who receive acupuncture treatment will not be aware of their group assignment; however, the waiting-list control group cannot be blinded. The patients receiving acupuncture treatment during the trial period, RA who performs the baseline assessment, acupuncturists, assessors and statisticians will all be blinded.

PPT measurement

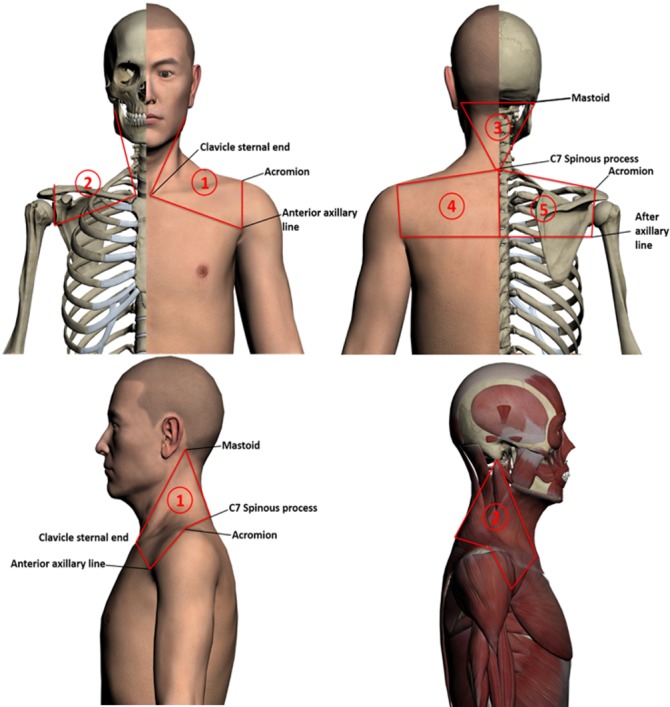

The PPT is widely used in clinical practice as a semiobjective method to quantify localised pain.22 23 Individuals with chronic neck pain have altered pain sensitivity,34–36 and so the PPT can be used to distinguish between patients with neck pain and healthy subjects.37 In accordance with the results of literature data-mining and expert consensus on the treatment of chronic neck pain, we identified 15 most frequently used acupoints (table 1) and the five regions of the body with the most frequent occurrence of pain and the greatest degree of acupoint sensitisation (figure 2). The body was divided into five regions to standardise the treatment procedures and detection areas.

Table 1.

Acupoints selected for use in the study

| Acupoints | Location |

| Jianjing (GB-21) | On the shoulder, directly above the nipple, at the midpoint of the line connecting Dazhui (DU-14) with the acromial end of clavicle |

| Jianzhongshu (SI-15) | On the back, 2 cun lateral to the lower border of the spinous process of the seventh cervical vertebra |

| Wangu (GB-12) | On the head, in the depression posterior and inferior to the mastoid process |

| Fengchi (GB-20) | On the nape, below the occipital, on a level with Fengfu (DU-16), in the depression between the upper portion of trapezius and the sternocleidomastoid |

| Tianzhu (BL-10) | On the nape, 1.3 cun lateral to the posterior hairline, in the depression of the posterior hairline lateral to the trapezius muscle |

| Dazhui (DU-14) | On the posterior median line, in the depression below the spinous process of the seventh cervical vertebra |

| Dazhu (BL-11) | On the back, 1.5 cun lateral to the lower border of the spinous process of the first thoracic vertebra |

| Jianwaishu (SI-14) | On the back, 3 cun lateral to the lower border of the spinous process of the first thoracic vertebra |

| Tianliao (SJ-15) | On the region of scapula, at the midpoint of the line connecting Jianjing (GB-21) with Quyuan (SI-13), on the superior angle of the scapula |

| Jugu (LI-16) | In the upper portion of the shoulder, in the depression between the acromial end of clavicle and the scapular spine |

| Tianzong (SI-11) | In the region of the scapula, in the depression of the centre of the subscapular fossa, on a level with the fourth thoracic vertebra |

| Shousanli (LI-10) | Flexing the elbow, on the dorsal radial side of the forearm, on the line connecting Yangxi (LI-5) with Quchi (LI-11), 2 cun below the transverse cudital crease |

| Lieque (LU-7) | On the radial margin of the forearm, 1.5 cun above the transverse crease of the wrist, between the branchioradial muscle and the long abductor muscle tendon of thumb |

| Zhongzhu (SJ-3) | On the dorsum of the hand, in the depression between the fourth and fifth metacarpal bones, proximal to the fourth metacarpalangeal joint |

| Houxi (SI-3) | On the ulna side of the palm, proximate to the fifth metacarpophalangeal joint, at the end of transverse crease of metacarpophalangeal joint, at the dorsoventral boundary |

Figure 2.

The test regions that will be used in the study. Regions 1 and 2 are each bordered by the respective ipsilateral mastoid, sternal end of the clavicle, anterior axillary line, acromion and C7 spinous process. Region 3 is the triangular region bordered by both sides of the mastoid and the C7 spinous process. Regions 4 and 5 are each bordered by the respective ipsilateral C7 spinous process, acromion and axillary line; the two regions are divided by the posterior midline.

RAs will mark the 15 acupoints on each patient. The RA will then palpate the detection area associated with each acupoint using the appropriate force (<2000 gf) and will identify the sensitive points that have pain/sourness/heaviness/fullness or nodules. RAs will use the FDIX Force Gauge (Force One FDIX, Wagner Instruments, Greenwich, CT, USA) to make 2 measurements of the PPT at each of the 15 acupoints in the 5 regions. If there is a difference between the two PPT measurements of more than 500 gf at one acupoint, the acupoint will be measured for the third time. Progressive pressure will be applied at a rate of 100 gf/s at each acupoint. The PPTs will be summed to calculate the average. The absolute value of the change in the PPT in the included patients will then be calculated, and this will be compared with that of healthy subjects collected in the early stage (online appendix table).

bmjopen-2018-026904supp001.pdf (155.8KB, pdf)

Interventions

Highlysensitive acupoints group

The acupuncturist will identify the five sensitive points/acupoints at which the absolute value of change in the PPT is the largest. Acupuncture will be performed at these five acupoints three times weekly for the first 2 weeks, and then two times weekly for the subsequent 2 weeks, giving a total of 10 sessions. Each of the five selected acupoints will be punctured using a stainless steel needle (0.25×40 mm), and the Deqi sensation (a sensation of distension or numbness, or a twitch response) will be achieved. Needle retention time will be 30 min. The PPT of the sensitive acupoints will be evaluated every 2 weeks, and the selection of acupuncture points will be adjusted as each patient’s condition changes; this will ensure the implementation of individualised treatment.

Low/non-sensitive acupoints group

The acupuncturist will identify the five sensitive acupoints with the least change in the absolute value of the PPT, and acupuncture will be performed at these five acupoints. The puncture method and needles will be the same as for the highly sensitive acupoints group.

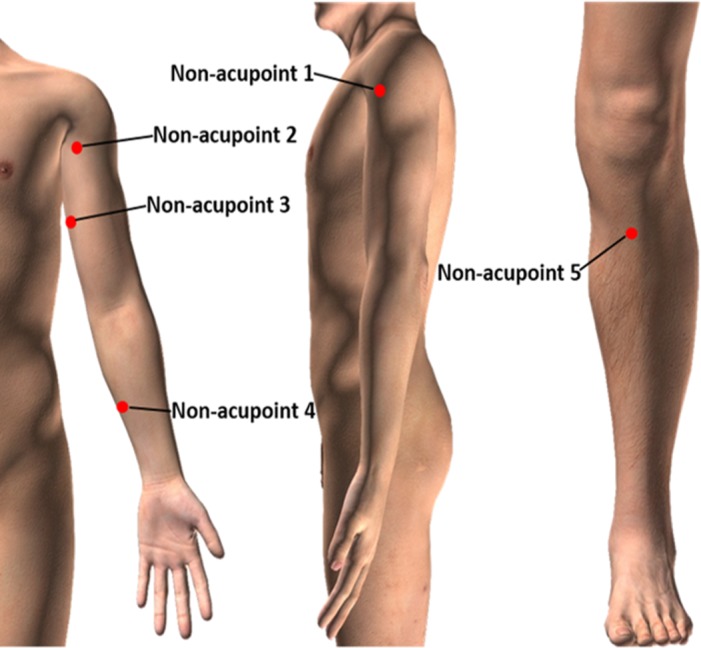

Sham acupuncture group

Acupuncture will be performed at five non-acupoints. The protocol for choosing the non-acupoints was developed in our previous clinical trial38 and another study39 (table 2 and figure 3). Shallow acupuncture will be applied at the five non-acupoints, without attempting to yield the Deqi sensation.

Table 2.

Details of the intervention in the sham acupuncture group

| Non-acupoint | Location | Manipulation |

| Non-acupoint 1 | In the middle of Binao (LI 14) and acromion | Punctured perpendicularly 0.5–1 cun |

| Non-acupoint 2 | At the medial arm on the anterior border of the insertion of the deltoid muscle at the junction of deltoid and biceps muscles | |

| Non-acupoint 3 | Half way between the tip of the elbow and axillae | |

| Non-acupoint 4 | Ulnar side, half way between the epicodylus medialis of the humerus and ulnar side of the wrist | |

| Non-acupoint 5 | Edge of the tibia 1–2 cm lateral to the Zusanli (ST36) horizontally |

Figure 3.

Locations of the five non-acupoints used in the study.

Waiting-list control group

No intervention will be performed in the waiting-list control group in the initial 24 weeks after randomisation. The participants will be informed that they are scheduled to receive 10 free acupuncture treatments at the end of the 24-week follow-up period.

If any participants experience severe neck pain during the initial 24 weeks, they will be permitted to take prescribed analgesic medications (such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) or effective analgesic medications that they are accustomed to taking, and the details will be recorded on the Case Report Form. Sustained-release or prophylactic analgesics are not allowed.

Outcome measurements

Follow-up examinations will be performed at 0, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20 and 24 weeks after randomisation in all four groups (table 3).

Table 3.

Outcome measurements at each timepoint

| Measurements | Baseline | Treatment phase | Follow-up phase | ||||||

| −4 weeks | 0 week | 2 weeks | 4 weeks | 8 weeks | 12 weeks | 16 weeks | 20 weeks | 24 weeks | |

| Measurements of pressure-pain threshold | × | × | × | ||||||

| VAS | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |

| NPQ | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||

| MPQ | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||

| SF-12 | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||

| NDI | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||

| CROM | × | × | |||||||

| SAS | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||

| SDS | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||

| Adverse events | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |

Primary outcome

The primary outcome will be the change in the VAS score for neck pain from baseline to 4 weeks. The VAS score ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating a greater degree of pain. The VAS is considered a valid method to assess pain intensity in clinical trials.40 The strengths of the VAS are its ease of use, good reliability and validity and metric measure that enables parametric testing. However, its limitation is that it is difficult for some subjects to mentally transform a subjective sensation into a mark on a straight line. Furthermore, previous research has suggested that the validity of VAS estimates performed by patients with chronic pain may be unsatisfactory.41

Secondary outcomes

Pain

We will also use the following indicators to comprehensively evaluate pain. The intensity of neck pain will be measured using the Northwick Park Neck Pain Questionnaire and the McGill Pain Questionnaire. The changes in the PPT during the treatment phase will be evaluated. The times and doses of analgesic drugs taken during the study period and the disease-related treatment performed during the follow-up period will also be recorded.

Quality of life

Quality of life will be assessed using the Chinese version of the Medical Outcome Study Short-Form 12-Item Health Survey.

Neck function

The change in neck function will be evaluated using the Neck Disability Index and the cervical range of motion. Recent research has shown that the Neck Disability Index has an excellent ability to distinguish between patients with different levels of perceived dysfunction.42

Emotional disorders

Chronic pain is often accompanied by emotional disorders.43 44 Changes in mood will be assessed using the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale and the Self-Rating Depression Scale.

Data and Safety Monitoring Board

To ensure the integrity of the RCT and protect the rights and health of the participants, we will set up a Data and Safety Monitoring Board. The Data and Safety Monitoring Board is an independent advisory group that will maintain the scientific and ethical standards of the RCT and will be responsible for data evaluation during the study period. The Data and Safety Monitoring Board will be developed in accordance with the Operational Guidelines for the Establishment and Functioning of Data and Safety Monitoring Boards of the WHO.

Safety and acupuncture-related adverse events

Acupuncture may cause several adverse events, including bleeding, haematoma, fainting, serious pain and local infection.45 Hence, we will record any acupuncture-related adverse events that occur during the treatment and follow-up phases and will also record the potential reasons for these adverse events. The number and type of adverse events in each group will be calculated. Patients will receive appropriate intervention for any adverse events that occur. Serious adverse events will be immediately reported to the primary investigator, and the affected participants will be withdrawn from the study.

Patients and public involvement

Patients and the public are not involved in the design or conduct of the study or the outcome measures, and no attempt will be made to assess the burden of the intervention on the patients themselves.

Sample size calculation

The sample size calculation was based on the superiority test. The primary outcome is the change in the VAS score from baseline to week 4. The clinical difference in the VAS score after acupuncture treatment is reported as 6.317; therefore, we conservatively estimated that there would be a VAS score change of 5 between the highly sensitive acupoints group and the low/non-sensitive acupoints group, 10 between the highly sensitive acupoints group and the sham acupuncture group and 20 between the highly sensitive acupoints group and the waiting-list control group. Considering a two-sided significance level of 5% and power of 95%, 621 participants are required with a 1:1:1:1 group allocation rate, as calculated by Fisher’s exact test in G*Power V.3.1.5. To minimise attrition bias, we assumed a dropout rate of 15%, making it necessary to include at least 716 participants in total.

Statistical analysis

The included patients will be divided into the full analysis set (FAS), per protocol set (PPS) and safety set (SS). The FAS population will consist of all participants for whom the primary outcome is evaluable. The FAS population will be used as the primary population for all efficacy analyses. The PPS population will consist of all participants who undergo the planned interventions. The SS will consist of all randomised participants who received at least one acupuncture treatment during the study period. All data will be managed by the data coordinating centre through a third party (the Brightech-Magnsoft Data Services Company).

A statistician blinded to the group allocations will conduct all analyses using the SAS V.9.4 software package (SAS Institute). First, the basic information of the four groups will be described, including patient characteristics, medical characteristics, outcome variables and adverse events. If an adjustment is needed for a baseline value that differs between groups, covariance analysis will be performed. Data will be presented as mean (SD) for continuous variables and as frequency (percentage) for categorical variables. Group comparisons will then be undertaken using χ2 tests for categorical characteristics and analysis of variance for continuous variables. The primary analyses will examine whether acupuncture performed in the highly sensitive acupoints group will achieve statistically better treatment outcomes (pain, quality of life, neck function and emotional disorders) than acupuncture in the low/non-sensitive acupoints group, sham acupuncture groupand waiting-list control group. To accommodate the correlation between repeated measures from the same participant, generalised linear models with random effects will be fitted to assess the effect of intervention on outcome variables over time, while accounting for the effects of potential confounders (eg, age, sex, analgesic medications and other treatments). We will use the last value carried forward method to impute missing data for the primary and secondary outcomes. All analyses will use two-sided tests, and a p value of <0.05 will be considered statistically significant.

Ethics and dissemination

This RCT was designed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The trial protocol is registered on the primary registry in the WHO registry network (Chinese Clinical Trial Registry). Signed consent will be obtained from each patient after they have been informed of the study procedures, possible risks and their right to withdraw from the trial.

This study will be the first multicentre RCT to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of acupuncture at sensitive points for chronic neck pain. The concept of sensitive points comes from the theory of traditional Chinese medicine, which purports a link between disease status and the condition of acupuncture points; when the body is affected by diseases, particular points become sensitive.25 The results of this study may provide further evidence for the effectiveness of acupuncture in relieving chronic neck pain.

This study has some strengths that warrant mention. In contrast with previous studies,31 this trial established a sham group to investigate the placebo effect of acupuncture. The creation of a waiting-list control group will rule out self-healing of the disease, and control for the Hawthorne effect. The waiting-list control group will receive the same acupuncture intervention after the 24-week follow-up period. This design provides participants with a guarantee that they are going to receive acupuncture treatment, overcoming the potential problem of control participants being disappointed.46 In addition, the blinding of the patients, operators, acupuncturists, assessors and statisticians will decrease potential bias.

As this will be the first study to investigate the effectiveness of acupuncture at sensitive acupoints for chronic neck pain, this RCT may have some limitations. There are several types of point sensitisation, such as pain and heat.47 48 However, in this trial, we quantified only the pain as the indicator of sensitisation, which might overlook the other forms of acupoint sensitisation. Further study is needed to confirm the improvement in clinical efficacy of acupuncture at different kinds of sensitive acupoints. If the results show that acupuncture therapy at sensitive acupoints is safe and effective in reducing chronic neck pain, this study will provide evidence to support the superior clinical efficacy of performing acupuncture at sensitive acupoints compared with low/non-sensitive acupoints.

Conclusion

This article describes the design and protocol of a study that aims to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of acupuncture for chronic neck pain. The results will reveal whether sensitive acupoints have specificity and whether acupuncture at highly sensitive acupoints is superior to acupuncture at low/non-sensitive points or sham acupuncture at non-acupoints.

Trial status

This study is currently in the recruitment phase. The first patient was enrolled in June 2018, and the study is expected to end in December 2019.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of Brightech-Magnsoft Data Services Company for their substantial contributions to the design and statistical analysis plan of this trial. We thank the staff of Chengdu CTC Tianfu Digital Technology Inc. for providing images. We acknowledge the help and contributions from the research assistants, acupuncturists, experts and investigators in each cente. We thank the patients with chronic neck pain for participating in this trial. We also thank Dr. Kelly Zammit, BVSc, from Liwen Bianji, Edanz Group China (www.liwenbianji.cn/ac), for editing the English text of a draft of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: MS, GG, JC, DC, HZ, LZ and F-rL participated in the design of the trial, creating the data analysis plan and drafting the manuscript. XM, MY, XL and JD collected the information needed for the performance of this trial in each centre. All the authors discussed, read and revised the manuscript, and gave final approval for the publication of this study protocol.

Funding: This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81590951, no. 81722050).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study protocol has been approved by the institutional review board and ethics committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (permission number: 2017 KL-038) (May 2018).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The submitted manuscript is a study protocol which includes no primary data now. Further information unaddressed can be obtained from the corresponding author by the contact methods provided in the manuscript.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Sari-Kouzel H, Cooper R. Managing pain from cervical spondylosis. Practitioner 1999;243:334–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bogduk N, Lord SM. Cervical spine disorders. Curr Opin Rheumatol 1998;10:110–5. 10.1097/00002281-199803000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hoggjohnson S, Velde GVD, Carroll LJ, et al. The burden and determinants of neck pain in the general population: results of the bone and joint decade 2000–2010 Task force on neck pain and its associated disorders. Best evidence on the burden and determinants of neck. European Spine Journal 2008;17:39–51. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang B, Duan YP, Zhang YC, et al. [Epidemiologic research on the clinical features of patients with cervical spondylosis]. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2004;29:472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Murray CJ, Atkinson C, Bhalla K, et al. The state of US health, 1990–2010: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA 2013;310:591–608. 10.1001/jama.2013.13805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hoy D, March L, Brooks P, et al. The global burden of low back pain: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:968–74. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Borghouts JA, Koes BW, Vondeling H, et al. Cost-of-illness of neck pain in The Netherlands in 1996. Pain 1999;80:629–36. 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00268-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kleinman N, Patel AA, Benson C, et al. Economic burden of back and neck pain: effect of a neuropathic component. Popul Health Manag 2014;17:224–32. 10.1089/pop.2013.0071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Berman BM, Swyers JP. Establishing a research agenda for investigating alternative medical interventions for chronic pain. Prim Care 1997;24:743–58. 10.1016/S0095-4543(05)70308-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Witt CM, Jena S, Brinkhaus B, et al. Acupuncture for patients with chronic neck pain. Pain 2006;125(1-2):98–106. 10.1016/j.pain.2006.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. White AR, Ernst E. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials of acupuncture for neck pain. Rheumatology 1999;38:143–7. 10.1093/rheumatology/38.2.143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Irnich D, Behrens N, Gleditsch JM, et al. Immediate effects of dry needling and acupuncture at distant points in chronic neck pain: results of a randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled crossover trial. Pain 2002;99(1):83–9. 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00062-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cerezo-Téllez E, Torres-Lacomba M, Fuentes-Gallardo I, et al. Effectiveness of dry needling for chronic nonspecific neck pain: a randomized, single-blinded, clinical trial. Pain 2016;157:1905–17. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Madsen MV, Gøtzsche PC, Hróbjartsson A. Acupuncture treatment for pain: systematic review of randomised clinical trials with acupuncture, placebo acupuncture, and no acupuncture groups. BMJ 2009;338:a3115–33. 10.1136/bmj.a3115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pilkington K. Evidence on acupuncture and pain: reporting on a work in progress. J Acupunct Meridian Stud 2015;8:217–9. 10.1016/j.jams.2015.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Seo SY, Lee KB, Shin JS, et al. Effectiveness of acupuncture and electroacupuncture for chronic neck pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Chin Med 2017;45:1573–95. 10.1142/S0192415X17500859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. White P, Lewith G, Prescott P, et al. Acupuncture versus placebo for the treatment of chronic mechanical neck pain: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:911 10.7326/0003-4819-141-12-200412210-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Irnich D, Behrens N, Gleditsch JM, et al. Immediate effects of dry needling and acupuncture at distant points in chronic neck pain: results of a randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled crossover trial. Pain 2002;99:83–9. 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00062-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vas J, Perea-Milla E, Méndez C, et al. Efficacy and safety of acupuncture for chronic uncomplicated neck pain: a randomised controlled study. Pain 2006;126:245–55. 10.1016/j.pain.2006.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lf H, Lin ZX, Leung AWN, et al. Efficacy of abdominal acupuncture for neck pain: a randomized controlled trial. 2017;12:e0181360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yang Y, Yan X, Deng H, et al. The efficacy of traditional acupuncture on patients with chronic neck pain: study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2017;18:312 10.1186/s13063-017-2009-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Persson AL, Brogårdh C, Sjölund BH. Tender or not tender: test-retest repeatability of pressure pain thresholds in the trapezius and deltoid muscles of healthy women. J Rehabil Med 2004;36:17–27. 10.1080/16501970310015218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fischer AA. Pressure algometry over normal muscles. Standard values, validity and reproducibility of pressure threshold. Pain 1987;30:115–26. 10.1016/0304-3959(87)90089-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yan CQ, Zhang S, Li QQ, et al. Detection of peripheral and central sensitisation at acupoints in patients with unilateral shoulder pain in Beijing: a cross-sectional matched case-control study. BMJ Open 2017;7:e014438 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Luo Y-N, Zhou Y-M, Zhong X, et al. Observation of pain-sensitive points in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a pilot study. Eur J Integr Med 2018;21:77–81. 10.1016/j.eujim.2018.06.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen S, Miao Y, Nan Y, et al. The study of dynamic characteristic of acupoints based on the primary dysmenorrhea patients with the tenderness reflection on Diji (SP 8). Evidence-Based Complementray and Alternative Medicine 2015;2015:158012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chae Y, Kim HY, Lee HJ, et al. The alteration of pain sensitivity at disease-specific acupuncture points in premenstrual syndrome. J Physiol Sci 2007;57:115–9. 10.2170/physiolsci.RP012706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tunks E, Crook J, Norman G, et al. Tender points in fibromyalgia. Pain 1988;34:11–19. 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90176-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhang CR, Xiao HH, Chen RX. Observation on curative effect of moxibusting on heat-sensitive points on pressure sores. China Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine & Pharmacy 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chen RX, Kang MF. Acupoint heat-sensitization and its clinical significance. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 2001;2006:488–9. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tang L, Jia P, Zhao L, et al. Acupuncture treatment for knee osteoarthritis with sensitive points: protocol for a multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2018;8:e023838 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010;340:c332–702. 10.1136/bmj.c332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hugh MP, Altman DG, Richard H, et al. Revised STandards for Reporting Interventions in Clinical Trials of Acupuncture (STRICTA): extending the CONSORT statement. Journal of Evidence-Based Medicine 2010;3:35–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shahidi B, Maluf KS. Adaptations in evoked pain sensitivity and conditioned pain modulation after development of chronic neck pain. Biomed Res Int 2017;2017:1–6. 10.1155/2017/8985398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nijs J, Kosek E, Van Oosterwijck J, et al. Dysfunctional endogenous analgesia during exercise in patients with chronic pain: to exercise or not to exercise? Pain Physician 2012;15(3 Suppl):ES205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Johnston V, Jull G, Darnell R, et al. Alterations in cervical muscle activity in functional and stressful tasks in female office workers with neck pain. Eur J Appl Physiol 2008;103:253–64. 10.1007/s00421-008-0696-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Olson SL, O’Connor DP, Birmingham G, et al. Tender point sensitivity, range of motion, and perceived disability in subjects with neck pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2000;30:13–20. 10.2519/jospt.2000.30.1.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhao L, Chen J, Li Y, et al. The long-term effect of acupuncture for migraine prophylaxis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:508–15. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Melchart D, Streng A, Hoppe A, et al. Acupuncture in patients with tension-type headache: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2005;331:376–82. 10.1136/bmj.38512.405440.8F [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Caraceni A, Cherny N, Fainsinger R, et al. Pain measurement tools and methods in clinical research in palliative care: recommendations of an Expert Working Group of the European Association of Palliative Care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2002;23:239–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Carlsson AM. Assessment of chronic pain. I. Aspects of the reliability and validity of the visual analogue scale. Pain 1983;16:87–101. 10.1016/0304-3959(83)90088-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Saltychev M, Mattie R, McCormick Z, et al. Psychometric properties of the neck disability index amongst patients with chronic neck pain using item response theory. Disabil Rehabil 2018;40:1–6. 10.1080/09638288.2017.1325945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Laurent B. Chronic pain: emotional and cognitive consequences]. Bulletin De Lacadémie Nationale De Médecine 2015;199(4-5):543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Maletic V, Raison CL. Neurobiology of depression, fibromyalgia and neuropathic pain. Front Biosci 2009;14:5291 10.2741/3598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ling Z, Zhang FW, Ying L, et al. Adverse events associated with acupuncture: three multicentre randomized controlled trials of 1968 cases in China. Trials 2011;12:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ainsworth HR, Torgerson DJ, Kang ’Ombe AR. Conceptual, design, and statistical complications associated with participant preference. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci 2010;628:176–88. 10.1177/0002716209351524 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ben H, Li L, Rong PJ, et al. Observation of pain-sensitive points along the Meridians in patients with gastric ulcer or gastritis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2012;2012:1–7. 10.1155/2012/130802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chen RX, Kang MF, Chen MR. [Return of Qibo: on hypothesis of sensitization state of acupoints]. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu 2011;31:134–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-026904supp001.pdf (155.8KB, pdf)