Abstract

Background

Mycoplasma genitalium is increasingly seen as an emerging sexually transmitted pathogen, and has been likened to Chlamydia trachomatis, but its natural history is poorly understood. The objectives of this systematic review were to determine M. genitalium incidence, persistence, concordance between sexual partners and the risk of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID).

Methods

We searched Medline, EMBASE, LILACS, IndMed and African Index Medicus from 1 January 1981 until 17 March 2018. Two independent researchers screened studies for inclusion and extracted data. We examined results in forest plots, assessed heterogeneity and conducted meta-analysis where appropriate. Risk of bias was assessed for all studies.

Results

We screened 4634 records and included 18 studies; six (4201 women) reported on incidence, five (636 women) on persistence, 10 (1346 women and men) on concordance and three (5139 women) on PID. Incidence in women in two very highly developed countries was 1.07 per 100 person-years (95% CI 0.61 to 1.53, I2 0%). Median persistence of M. genitalium was estimated from one to three months in four studies but 15 months in one study. In 10 studies measuring M. genitalium infection status in couples, 39%–50% of male or female sexual partners of infected participants also had M. genitalium detected. In prospective studies, PID incidence was higher in women with M. genitalium than those without (risk ratio 1.73, 95% CI 0.92 to 3.28, I2 0%, two studies).

Discussion

Incidence of M. genitalium in very highly developed countries is similar to that for C. trachomatis, but concordance might be lower. Taken together with other evidence about age distribution and antimicrobial resistance in the two infections, M. genitalium is not the new chlamydia. Synthesised data about prevalence, incidence and persistence of M. genitalium infection are inconsistent. These findings can be used for mathematical modelling to investigate the dynamics of M. genitalium.

Registration numbers

CRD42015020420, CRD42015020405

Keywords: mycoplasma, infectious diseases, systematic reviews, meta-analysis

Introduction

Mycoplasma genitalium is increasingly seen as an emerging sexually transmitted pathogen.1–4 M. genitalium is a cause of non-gonococcal urethritis1 and cervicitis,3 and associations with pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), other reproductive tract complications in women and adverse pregnancy outcomes have been found.3 M. genitalium has thus been called the ‘new chlamydia’.5 In a previous systematic review, we found a prevalence of M. genitalium of approximately 1% in sexually active heterosexuals in the general population, which is similar to that reported for Chlamydia trachomatis aged 16–44 years.6 In sex workers, men who have sex with men (MSM) and clinic-based populations prevalence was higher and more variable.7 The increasing availability of nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT) that detect M. genitalium has resulted in debate about the need for widespread testing of asymptomatic populations.8–10 But increased testing and treatment are likely to increase the already high proportion of antimicrobial resistant M. genitalium since resistance to macrolides often emerges during treatment.11 12

Mathematical modelling could help to understand the balance of benefits and harms that widespread testing and treatment interventions bring.9 To develop mathematical models, we need robust estimates from clinical and epidemiological studies about key variables that determine the spread of infection in a population13 and progression to complications.9 These variables include the incidence of infection; persistence of untreated infection, which can be used to estimate the duration of infectiousness;14 concordant M. genitalium status between sexual partners, which can be used to derive the transmission probability;15 16 and the probability that M. genitalium in the lower genital tract ascends to cause PID, which can result in tubal factor infertility and ectopic pregnancy.17 In the first published model of M. genitalium transmission and the impact of screening, the authors noted the uncertainty about the values used for parameters describing the natural history of infection and progression to PID.9 The objectives of this study were to systematically review the research literature to estimate the incidence of M. genitalium infection, persistence of untreated M. genitalium, concordance of M. genitalium detection and the risk of developing PID.

Methods

This systematic review is one of two linked reviews that used a single search strategy and are described in two protocols.18 19 A review of the prevalence of M. genitalium has been published.7 We report our findings according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA, online supplementary file 1).20

sextrans-2018-053823supp001.pdf (444KB, pdf)

Eligibility criteria

We included studies of M. genitalium detected by NAAT. Study populations were women and men older than 13 years in any country. Eligible study designs were as follows: for incidence of M. genitalium, cohort studies with participants who were uninfected at baseline; for persistence, cohort studies that followed people with untreated M. genitalium infection; for concordance, cross-sectional studies which enrolled couples or sexual partners of index cases, excluding studies in which the infection status of a sexual partner was based on self-report; for incidence of PID, cohort or nested case–control studies that compared women with and without M. genitalium, excluding cross-sectional studies and case–control studies in which it could not be established that M. genitalium infection preceded a diagnosis of PID.

Information sources and search strategy

We searched Medline and EMBASE databases for publications in any language from 1 January 1981 until 12 July 2016 and updated the search to 17 March 2018. We used thesaurus headings and free-text terms that combined Mycoplasma or Mycoplasma genitalium with genital tract complications (online supplementary file 2, online supplementary text S1–3). We also searched the African Index Medicus, IndMED and LILACS, using the term Mycoplasma genitalium. Records were managed using EndNote (V.X8.1; Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA).

sextrans-2018-053823supp002.pdf (679.1KB, pdf)

Study selection

Abstracts published before 1 January 1991 were excluded. Two reviewers (MC, LB) assessed study eligibility independently, using a pre-piloted screening form. We resolved differences by discussion or adjudication by a third reviewer (NL).

Data collection

Two reviewers (MC, LB, DE-G, HA) extracted data independently. Differences were resolved by discussion or adjudication. We extracted data using a standardised, piloted data extraction form in a Research Electronic Data Capture database (REDCap; Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee, USA). For each study, we extracted data about study characteristics, methods and results. For studies reporting persistence of M. genitalium only in graphs, we used Plot Digitizer software21 to record numerical data. We labelled studies with the country in which the data were collected and added consecutive numbers for studies subsequently identified from the same country. Studies reported in the linked systematic review of M. genitalium prevalence have the same study identifier (online supplementary table S1).7 We contacted authors to clarify details of study methods and results, where necessary.

Risk of bias in individual studies

For cohort or nested case–control studies, we adapted a tool published by the Cochrane Bias Methods Group.22 For cross-sectional studies, we applied a previously used checklist7 23 (online supplementary file 2, online supplementary text S4).

Summary measures

We defined incidence in cohort studies as the rate of new M. genitalium infections per 100 person-years of observation in individuals with a negative M. genitalium test, either at baseline or a negative test of cure following treatment of a prevalent infection. We defined persistence of M. genitalium infection in cohort studies as the proportion of study participants at each follow-up visit with a positive test result. We assessed concordance of M. genitalium infection status in cross-sectional studies as the proportion of sexual partners of an infected index case that had a positive test result. We assessed the development of PID in cohort studies and calculated the odds ratio (OR) or risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for PID in participants with and without M. genitalium infection at baseline.

Synthesis of results

We used Stata (V.13.1; StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA) for statistical analysis. We examined data about incidence, concordance and PID in forest plots. We stratified studies reporting incidence according to the level of development of the country in which the study was conducted, categorised as very high, high, medium and low using the United Nations Development Programme Human Development Index (HDI),24 as we found differences between countries with higher or lower human development index in our linked review of M. genitalium prevalence.7 We stratified studies reporting concordance according to study design: studies can enrol couples irrespective of infection status and test all individuals for M. genitalium (referred to as partner studies), or can enrol an index case with M. genitalium and then test their partners (referred to as index case studies). We calculated the percentage (with 95% CI) concordance separately for women and men. We assessed the percentage of study variability between studies caused by heterogeneity other than that due to chance with the I2 statistic.25 Meta-analysis was conducted when deemed appropriate using fixed or random effects models. For estimates of incidence, we estimated a summary estimate of the incidence rate per 100 person-years of follow-up (with 95% CI). For concordance, we applied the Freeman-Tukey arcsine transformation to the proportions before meta-analysis and back transformed the summary estimate and its 95% CI.

The data about persistence of M. genitalium are presented graphically (Excel:mac 2008, V.12.3.6; Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington, USA) without statistical analysis because we anticipated that the results would be too heterogeneous to combine.16 We conducted a subgroup analysis, using a test of interaction, of differences in concordance by study design.

Risk of bias across studies

We did not test for small study biases with funnel plots because of the small number of included studies.

Results

We identified 4634 records and, after exclusion of duplicates and articles published before 1991, we screened 3820 records. We included 18 studies, some of which reported on more than one review question (table 1, online supplementary file 2, figure S1, table S1). Six studies reported on incidence,5 26–30 five reported on persistence,5 26–28 31 10 reported on concordance between partners31–40 and three studies reported on development of PID.5 41 42

Table 1.

Included studies (n=18), ordered according to outcomes reported

| Study identifier | Study population | Study design | Review topics |

| Great Britain 25 | Female students aged ≤27 years; universities and further education colleges, London, Great Britain | Cohort study | Incidence, persistence, PID |

| Kenya 226 | Female sex workers aged 18–35 years; Kariobangi Nairobi City Council, Nairobi, Kenya | Cohort study | Incidence, persistence |

| Kenya 328 | Female sex workers, median age 35.3 years; municipal STI clinic Mombasa, Kenya | Cohort study | Incidence, persistence |

| Uganda 127 | Female sex workers aged 18–40 years; red light areas within southern Kampala, Uganda | Cohort study | Incidence, persistence |

| Australia 329 | Young women aged 16–25 years; primary health clinics in Melbourne, Australia | Cohort study | Incidence |

| USA/Kenya 130 | High-risk women aged 18–45 years; research clinics in Mombasa and Nairobi, Kenya and Birmingham, USA | Cohort study | Incidence |

| USA 731 | Women aged 14–17 years and their partners; urban primary healthcare centres, Indianapolis, USA | Cohort study, cross-sectional sampling of couples | Persistence, concordance |

| Great Britain 834 | Women and their partners; STI clinic, St. Mary's Hospital, London, Great Britain | Cross-sectional | Concordance |

| Great Britain 933 | Men and their partners; STI clinic, St. Mary's Hospital, London, Great Britain | Cross-sectional | Concordance |

| Peru 135 | Couples, men aged 19–60 years, women aged 18–55 years; two STI clinics, Lima, Peru | Cross-sectional | Concordance |

| USA 832 | Mexican-American and African-American women with non-viral STI aged 14–45 years and their male partners; San Antonio Metropolitan Health District STI Clinic, USA | Cross-sectional | Concordance |

| Sweden 236 | Men aged 16–67 years and their partners; Örebrö University Hospital STI clinic, Sweden | Index cases and sexual partners | Concordance |

| Sweden 537 | Women aged 14–55 years and men aged 17–67 years and their partners; STI clinic, Falun, Sweden | Index cases and sexual partners | Concordance |

| Sweden 1138 | Women aged 15–54 years and their partners; Örebrö University Hospital STI clinic, Sweden | Index cases and sexual partners | Concordance |

| Sweden 1239 | Male patients with symptomatic recurrent and/or persistent urethritis aged 20–47 years and their partners; STI clinic, Karolinska Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden | Index cases and sexual partners | Concordance |

| Australia 640 | Partners of index cases with M. genitalium, median age of female heterosexual partners 26 years; male heterosexual partners 28 years; MSM partners 29 years; Melbourne Sexual Health Centre, Australia | Index cases and sexual partners | Concordance |

| Sweden 1041 | Women after medical or surgical termination of pregnancy aged 17–40 years; gynaecological outpatient department Malmö University Hospital, Sweden | Nested case–control study | PID* |

| USA 642 | Women after treatment and cure of PID aged 14–37 years; multiple clinical sites in the USA | Cohort study | PID† |

*Post-abortion upper genital tract infection.

†Endometritis considered as confirmed PID.

MSM, men who have sex with men; PID, pelvic inflammatory disease; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Incidence

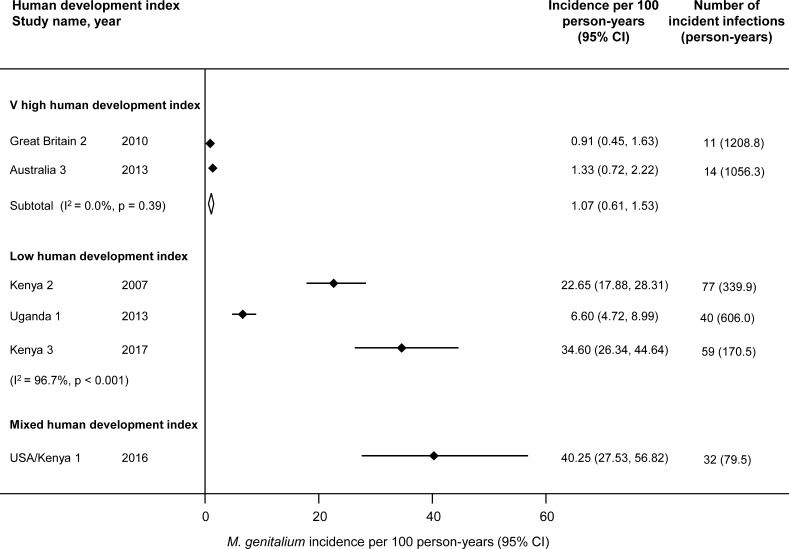

We included six studies (online supplementary table S2),5 26–30 with a total of 4201 female participants at baseline and follow-up of 3461 person-years. Two studies were conducted in countries with a very high HDI, with students (Great Britain 2)5 and with attendees of primary healthcare clinics (Australia 3).29 All three studies from countries with a low HDI were conducted with female sex workers in (Uganda 1, Kenya 2 and Kenya 3).26–28 Two of the four research clinics which enrolled participants for the USA/Kenya 1 study30 approached only female sex workers too. All women in the Uganda 1 study had a positive test for M. genitalium at baseline. Incidence was defined as a positive test result in women who had a preceding negative test result.27 All studies were at risk of bias (online supplementary table S3). All studies reported more than 20% loss to follow-up or did not report it.5 26–30 Only one (Great Britain 2) compared participants followed up until the end of the studies and participants lost to follow-up.5

Figure 1 shows that in countries with a very high HDI, the pooled estimate of incidence was 1.07 per 100 person-years (95% CI 0.61 to 1.53, 2 studies, I2 0%).5 29 The incidence rates in studies conducted among female sex workers were higher and too heterogeneous to combine (I2 96.7%).

Figure 1.

Incident M. genitalium infections per 100 person-years by human development index.24 Solid diamond and lines show the point estimate and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for each study. The diamond shows the point estimate and 95% CI of the summary estimate. The incidence estimates are plotted on a linear scale.

Persistent detection of M. genitalium

We included five studies,5 26–28 31 with a total of 636 female participants at baseline (online supplementary table S4). Three studies were conducted with female sex workers in Kenya and Uganda (Uganda 1, Kenya 2 and Kenya 3).26–28 The other two studies were conducted with adolescents enrolled from primary healthcare facilities (USA 7)31 and students from educational colleges (Great Britain 2).5 Duration of follow-up ranged from 12 weeks in USA 731 to 33 months in Kenya 2.26 Specific treatment for M. genitalium was not prescribed in any of the studies. All studies were at risk of bias in outcome assessment (online supplementary table S5). In Great Britain 2, women with a positive test result for C. trachomatis at baseline received antibiotics if they were in the intervention arm of the underlying randomised control trial but could have been treated before the 12-month follow-up.5 In all other studies, participants received either syndromic treatment or treatment for diagnosed C. trachomatis, N. gonorrhoeae and/or Trichomonas vaginalis at one-month to three-month intervals. Two studies (Great Britain 2, Kenya 2) distinguished persistent from re-infections with genotyping.5 26

Online supplementary figure S2 shows a rapid decrease in the proportion of women infected in four studies. Median persistence in the three studies of sex workers was one to three months. The Great Britain 2 study only assessed M. genitalium persistence at one subsequent time point at which 25.9% of participants were still infected after a median of 16 months.5 In USA 7, 31.3% of women remained positive at 8 weeks.31

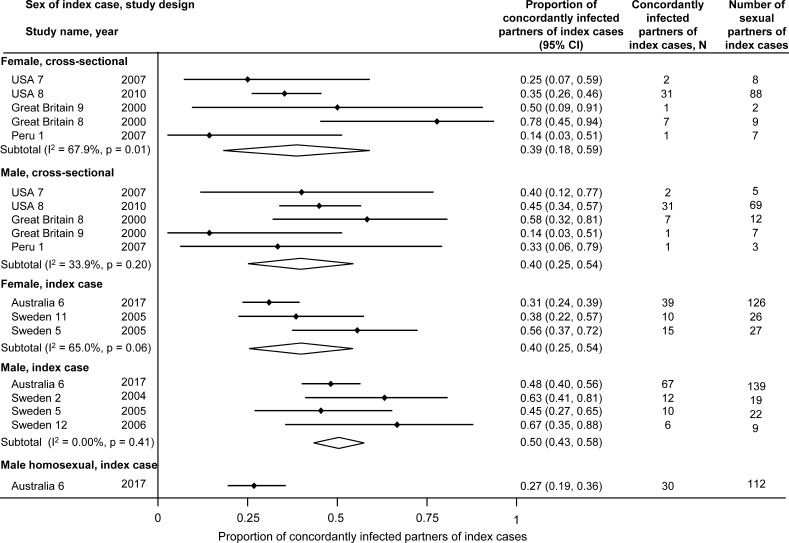

Concordance

We included 10 cross-sectional studies,31–40 all of which were conducted in healthcare facilities (online supplementary table S6). Five partner studies enrolled a total of 869 couples irrespective of infection status31–35 and five index case studies36–40 enrolled a total of 477 people with M. genitalium and 480 sexual partners. Only the Australia 6 study enrolled MSM.40 All studies were at risk of bias (online supplementary table S7).31–40 The response rate at baseline was only assessed in two studies in which it was below 70% (Great Britain 9 and Peru 1).33 35

Figure 2 shows overall concordance rates of 39%–40% among male partners of women with M. genitalium and 40%–50% in female partners of infected men, with no marked differences according to study design (online supplementary table S8). Concordance among MSM (Australia 6) was 27% (95% CI 19% to 36%).40

Figure 2.

Proportion of concordantly infected sexual partners of individuals with M. genitalium, by sex of index case and study design. Solid diamonds and lines show the point estimate and 95% confidence interval (CI) for each study. The diamond shows the point estimate and the 95% CI of the summary estimate. The proportions are plotted on a linear scale.

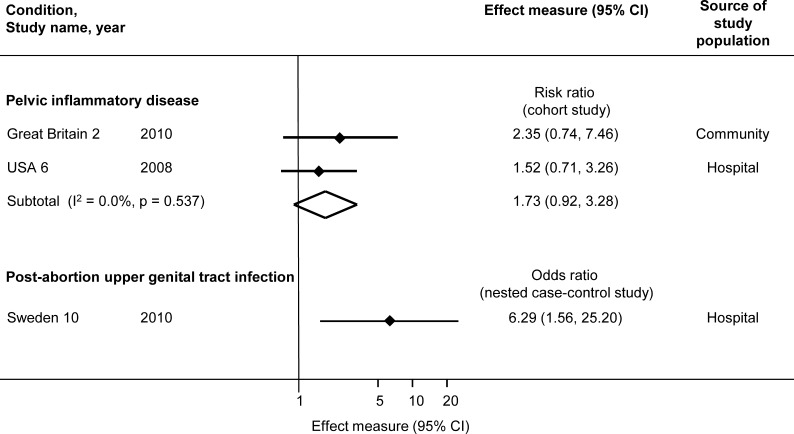

Pelvic inflammatory disease

We included three prospective studies that examined the risk for PID in M. genitalium-infected compared with non-infected participants, with a total of 5139 participants at baseline (online supplementary table S9).5 41 42 The Great Britain 2 study enrolled female students in London,5 USA 6 studied women who had taken part in a randomised controlled trial, after treatment and cure of a first episode of PID42 and Sweden 10 was a nested case–control study in women who had undergone medical or surgical termination of pregnancy.41 PID was diagnosed by endometrial biopsy in USA 6 and using clinical criteria in Great Britain 25 and Sweden 10.41 Follow-up was 6 weeks in Sweden 10,41 12 months in Great Britain 25 and 30 days in USA 6.42 All studies were at risk of bias (online supplementary table S10).5 41 42 None of the studies assessed whether factors that might be associated with progression to PID were similar between groups or compared individuals followed up with those lost to follow-up.

All studies found an association between M. genitalium and PID (figure 3). The summary RR for incident PID in the two cohort studies was 1.73 (95% CI 0.92 to 3.28, I2 0%). The OR for post-abortion upper genital tract infection was 6.29 (95% CI 1.56 to 25.20).41

Figure 3.

Risk of progression to upper genital tract infection in women with M. genitalium compared with women without M. genitalium. Solid diamonds and lines show the point estimate and 95% confidence interval (CI) for each study. The open diamond shows the point estimate and the 95% CI of the summary estimate. The effect estimates are plotted on a logarithmic scale.

Discussion

Main findings

In this systematic review, the incidence of M. genitalium was 1.07 per 100 person-years (95% CI 0.61 to 1.53, I2 0%, 2 studies) in women in very highly developed countries. Median duration of persistence of M. genitalium was one to three months in four studies but 15 months in one study. In 10 studies measuring M. genitalium infection status in heterosexual couples, proportions of concordant results were 39% to 50%. In two prospective studies, the incidence of PID was higher in women with M. genitalium than those without (RR 1.73, 95% CI 0.92 to 3.28, I2 0%).

Strengths and limitations

A strength of our systematic review is the broad search strategy that covered differing topics, which makes it unlikely that we missed important relevant articles. In addition, selection of studies and extraction of data by independent reviewers reduces the risk of errors in data extraction. We assessed the risk of bias in all included studies. The relative importance of the domains of bias affect interpretation depend on the topic. For example, when measuring the duration of persistent detection, accurate assessment of the outcome, untreated infection is important, but most studies were at high risk of bias. The main limitations of the review findings result from the small number of studies overall and between study heterogeneity.

Interpretation of the findings

Incidence and persistent detection of M. genitalium: The findings of this review do not allow an estimate of the duration of M. genitalium infectiousness. Estimates based on persistent detection in cohort studies are inconsistent (online supplementary figure S2, online supplementary table S4). Since duration of infection is related to prevalence (assessed in our linked review7) and incidence (figure 1), the findings can be compared with this alternative measure (Equation 1): duration of infection=prevalence÷incidence (1)

In this review, three studies estimated all three quantities (online supplementary table S11).5 26 28 In Great Britain 2,5 the duration of infection, both directly estimated and from Equation 1, was more than one year. In Kenya 226 and Kenya 3,28 the duration was less than one year by both methods. In Uganda 1,27 the directly estimated duration was less than one year but prevalence was higher than incidence, so Equation 1 results in an estimated duration of more than one year. In two studies that measured incidence and prevalence but not persistent detection, duration of infection could only be obtained using Equation 1, with an estimate of more than one year for Australia 329 and less than one year for USA/Kenya 130 (online supplementary table S11). In all studies, women had opportunities for treatment with antibiotics with some activity against M. genitalium at frequencies of as little as a month. The duration of persistent detection was short in all studies that offered treatment every three months or more frequently. With likely inadvertent treatment and re-infection, these cohort studies probably did not measure the persistence of untreated infection. Smieszek and White, who analysed the conflicting findings in the Great Britain 25 and Uganda 127 studies using a mathematical model, favoured a longer duration of infection similar to the Great Britain 2 study.16 The uncertainty about the duration of infectiousness of M. genitalium contrasts with C. trachomatis, for which the literature is extensive and there is broad agreement that prevalence in general populations in high-income countries is around 3%–4%,23 incidence is around 4%43 44 and average duration of infectiousness is slightly more than one year.14 45

M. genitalium concordance: The systematic review data suggest some possible differences between M. genitalium and C. trachomatis. Concordant M. genitalium status can be used to estimate the transmission probability of sexually transmitted pathogens.15 46 Cross-sectional studies of randomly sampled couples, irrespective of infection status, provide the least biased estimate.46 For this reason, we examined concordance separately in partner studies and in index case studies, but actually found similar estimates in both study designs. In cross-sectional studies, M. genitalium concordance was 39%–40%. In comparison, C. trachomatis concordance in a large cross-sectional study in the USA was 68% (95% CI 56% to 78%) for male partners and 70% (58% to 80%) for female partners.47 Findings from our systematic review of M. genitalium prevalence suggested that, while overall population prevalence of the two infections is similar, C. trachomatis positivity is concentrated in younger age groups.23

M. genitalium progression to PID: M. genitalium was associated with PID in prospective studies (RR 1.73, 95% CI 0.92 to 3.28), with CIs that were compatible with both a small reduction and a substantial increase in risk. The point estimate was slightly lower than that found by Lis et al, but their inclusion of cross-sectional studies and studies of post-abortal PID in the same meta-analysis might have overestimated the association.3 The increase in risk of PID following C. trachomatis is around 1.8 to 2.8.48 49 Using data from the Great Britain 2 study and taking into account the low population prevalence of M. genitalium, Oakeshott et al estimated that the population attributable fraction of PID due to M. genitalium was about 4%.5

Implications for research and practice

This review adds to the evidence about the biology, dynamics and natural history of M. genitalium as a sexually transmitted pathogen. Additional empirical research is needed to provide robust data about the epidemiology of M. genitalium infection in men and to determine the persistence of untreated M. genitalium in studies in which inadvertent treatment can be excluded. In the context of evidence of high levels of macrolide resistance in M. genitalium,11 12 which does not affect C. trachomatis, measures for the management and control of these infections are likely to differ. Despite earlier speculation,5 the findings of this review, our linked review of prevalence7 and evidence about antimicrobial resistance show that M. genitalium is not the new chlamydia. The estimates from this systematic review can be used in mathematical modelling studies to investigate differences between the transmission dynamics of M. genitalium and C. trachomatis and to investigate the potential benefits and harms of control interventions.

Key messages.

There is debate about the need for widespread screening for Mycoplasma genitalium, but the natural history of this emerging sexually transmitted pathogen is poorly understood.

M. genitalium incidence was 1.07 (95% CI 0.61 to 1.53) per 100 person-years in women in highly developed countries, 39%–50% of infected individuals had a heterosexual partner with M. genitalium and the risk ratio for progression to pelvic inflammatory disease was 1.73 (95% CI 0.92 to 3.28).

The duration of untreated M. genitalium infection could not be determined from this review but is probably longer than persistent detection of M. genitalium, as measured in most cohort studies, in which inadvertent treatment cannot be ruled out.

The results of this systematic review and other evidence sources show important differences in the epidemiology and dynamics of M. genitalium and Chlamydia trachomatis infection.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Myrofora Goutaki, who gave advice during the review process, Gian-Reto Lohrer, who assisted with data extraction, Dominque Cadosch, who helped with the analysis of persistence data and Anina Häfliger for administrative support.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Jane S Hocking

Contributors: Conceived and designed the review: LB, MC, NL, PS. Screened titles, abstracts and full texts: LB, MC, NL. Extracted the data: HA, LB, MC, DE-G. Analysed the data: LB, MC, FH, NL. Wrote the first draft: MC. Revised the paper before submission: HA, LB, MC, DE-G, FH, NL, PS. Approved the final version: HA, LB, MC, DE-G, FH, NL, PS.

Funding: This study received funding from the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant nos. 320030_173044 and 32003B-160320) and Swiss Programme for Research on global issues for Development (r4d): grant no. IZ07Z0_160909.

Competing interests: NL is deputy editor of Sexually Transmitted Infections.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Not applicable. We are not submitting an original research article.

References

- 1. Taylor-Robinson D, Jensen JS. Mycoplasma genitalium: from Chrysalis to multicolored butterfly. Clin Microbiol Rev 2011;24:498–514. 10.1128/CMR.00006-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sethi S, Singh G, Samanta P, et al. . Mycoplasma genitalium: an emerging sexually transmitted pathogen. Indian J Med Res 2012;136:942–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lis R, Rowhani-Rahbar A, Manhart LE. Mycoplasma genitalium infection and female reproductive tract disease: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2015;61:418–26. 10.1093/cid/civ312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bernstein K, Bowen VB, Kim CR, et al. . Re-emerging and newly recognized sexually transmitted infections: can prior experiences shed light on future identification and control? PLoS Med 2017;14:e1002474 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Oakeshott P, Aghaizu A, Hay P, et al. . Is Mycoplasma genitalium in women the "New Chlamydia?" A community-based prospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2010;51:1160–6. 10.1086/656739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sonnenberg P, Ison CA, Clifton S, et al. . Epidemiology of Mycoplasma genitalium in British men and women aged 16–44 years: evidence from the third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3). Int J Epidemiol 2015;44:1982–94. 10.1093/ije/dyv194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Baumann L, Cina M, Egli-Gany D, et al. . Prevalence of Mycoplasma genitalium in different population groups: systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Infect 2018;94:255–62. 10.1136/sextrans-2017-053384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ross JDC, Brown L, Saunders P, et al. . Mycoplasma genitalium in asymptomatic patients: implications for screening. Sex Transm Infect 2009;85:436–7. 10.1136/sti.2009.036046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Birger R, Saunders J, Estcourt C, et al. . Should we screen for the sexually-transmitted infection Mycoplasma genitalium? Evidence synthesis using a transmission-dynamic model. Sci Rep 2017;7 10.1038/s41598-017-16302-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McGowin CL, Rohde RE, Redwine G. Epidemiological and clinical rationale for screening and diagnosis of Mycoplasma genitalium infections. Clin Lab Sci 2014;27:47–52. 10.29074/ascls.27.1.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cadosch R, Garcia V, Althaus CL, et al. . De novo mutations drive the spread of macrolide resistant Mycoplasma genitalium: a mathematical modelling study. bioRxiv 2018;321216. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Horner P, Ingle SM, Garrett F, et al. . Which azithromycin regimen should be used for treating Mycoplasma genitalium? A meta-analysis. Sex Transm Infect 2018;94:14–20. 10.1136/sextrans-2016-053060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Anderson RM, May RM. Infectious diseases of humans: dynamics and control. Oxford United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Althaus CL, Heijne JCM, Roellin A, et al. . Transmission dynamics of Chlamydia trachomatis affect the impact of screening programmes. Epidemics 2010;2:123–31. 10.1016/j.epidem.2010.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Althaus CL, Heijne JCM, Low N. Towards more robust estimates of the transmissibility of Chlamydia trachomatis. Sex Transm Dis 2012;39:402–4. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318248a550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Smieszek T, White PJ. Apparently-different clearance rates from cohort studies of Mycoplasma genitalium are consistent after accounting for incidence of infection, recurrent infection, and study design. PLoS One 2016;11:e0149087 10.1371/journal.pone.0149087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Weström L, Joesoef R, Reynolds G, et al. . Pelvic inflammatory disease and fertility. A cohort study of 1,844 women with laparoscopically verified disease and 657 control women with normal laparoscopic results. Sex Transm Dis 1992;19:185–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Low N, Baumann L, Cina M, et al. . Mycoplasma genitalium infection: prognosis and transmissibility [CRD42015020405]. 2018. Available: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=20405 [Accessed 16 Jul 2018].

- 19. Low N, Cina M, Baumann B, et al. . Mycoplasma genitalium infection: prevalence, incidence and persistence [CRD42015020420]. Available: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=20420 [Accessed 16 Jul 2018].

- 20. Liberati A, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:W–94. 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Howaldt J. Plot Digitizer. Available: http://plotdigitizer.sourceforge.net/ [Accessed 19 Jun 2017].

- 22. Cochrane Collaboration Tool to assess risk of bias in cohort studies. Available: https://methods.cochrane.org/bias/sites/methods.cochrane.org.bias/files/public/uploads/Tool%20to%20Assess%20Risk%20of%20Bias%20in%20Cohort%20Studies.pdf [Accessed 20 Dec 2018].

- 23. Redmond SM, Alexander-Kisslig K, Woodhall SC, et al. . Genital Chlamydia prevalence in Europe and non-European high income countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0115753 10.1371/journal.pone.0115753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. United Nations Development Programme Human development report 2014: sustaining human progress—reducing vulnerabilities and building resilience. New York USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002;21:1539–58. 10.1002/sim.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cohen CR, Nosek M, Meier A, et al. . Mycoplasma genitalium infection and persistence in a cohort of female sex workers in Nairobi, Kenya. Sex Transm Dis 2007;34:274–9. 10.1097/01.olq.0000237860.61298.54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vandepitte J, Weiss HA, Kyakuwa N, et al. . Natural history of Mycoplasma genitalium infection in a cohort of female sex workers in Kampala, Uganda. Sex Transm Dis 2013;40:422–7. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31828bfccf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lokken EM, Balkus JE, Kiarie J, et al. . Association of recent bacterial vaginosis with acquisition of Mycoplasma genitalium. Am J Epidemiol 2017;186:194–201. 10.1093/aje/kwx043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Walker J, Fairley CK, Bradshaw CS, et al. . Mycoplasma genitalium incidence, organism load, and treatment failure in a cohort of young Australian women. Clin Infect Dis 2013;56:1094–100. 10.1093/cid/cis1210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Balkus JE, Manhart LE, Lee J, et al. . Periodic presumptive treatment for vaginal infections may reduce the incidence of sexually transmitted bacterial infections. J Infect Dis 2016;213:1932–7. 10.1093/infdis/jiw043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tosh AK, Van Der Pol B, Fortenberry JD, et al. . Mycoplasma genitalium among adolescent women and their partners. J Adolesc Health 2007;40:412–7. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Thurman AR, Musatovova O, Perdue S, et al. . Mycoplasma genitalium symptoms, concordance and treatment in high-risk sexual dyads. Int J STD AIDS 2010;21:177–83. 10.1258/ijsa.2009.008485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Keane FE, Thomas BJ, Gilroy CB, et al. . The association of Chlamydia trachomatis and Mycoplasma genitalium with non-gonococcal urethritis: observations on heterosexual men and their female partners. Int J STD AIDS 2000;11:435–9. 10.1258/0956462001916209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Keane FE, Thomas BJ, Gilroy CB, et al. . The association of Mycoplasma hominis, Ureaplasma urealyticum and Mycoplasma genitalium with bacterial vaginosis: observations on heterosexual women and their male partners. Int J STD AIDS 2000;11:356–60. 10.1258/0956462001916056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nelson A, Press N, Bautista CT, et al. . Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections and high-risk sexual behaviors in heterosexual couples attending sexually transmitted disease clinics in Peru. Sex Transm Dis 2007;34:344–61. 10.1097/01.olq.0000240341.95084.da [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Falk L, Fredlund H, Jensen JS. Symptomatic urethritis is more prevalent in men infected with Mycoplasma genitalium than with Chlamydia trachomatis. Sex Transm Infect 2004;80:289–93. 10.1136/sti.2003.006817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Anagrius C, Loré B, Jensen JS. Mycoplasma genitalium: prevalence, clinical significance, and transmission. Sex Transm Infect 2005;81:458–62. 10.1136/sti.2004.012062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Falk L, Fredlund H, Jensen JS. Signs and symptoms of urethritis and cervicitis among women with or without Mycoplasma genitalium or Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Sex Transm Infect 2005;81:73–8. 10.1136/sti.2004.010439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wikström A, Jensen JS. Mycoplasma genitalium: a common cause of persistent urethritis among men treated with doxycycline. Sex Transm Infect 2006;82:276–9. 10.1136/sti.2005.018598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Slifirski JB, Vodstrcil LA, Fairley CK, et al. . Mycoplasma genitalium infection in adults reporting sexual contact with infected partners, Australia, 2008–2016. Emerg Infect Dis 2017;23:1826–33. 10.3201/eid2311.170998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bjartling C, Osser S, Persson K. The association between Mycoplasma genitalium and pelvic inflammatory disease after termination of pregnancy. BJOG 2010;117:361–4. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02455.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Haggerty CL, Totten PA, Astete SG, et al. . Failure of cefoxitin and doxycycline to eradicate endometrial Mycoplasma genitalium and the consequence for clinical cure of pelvic inflammatory disease. Sex Transm Infect 2008;84:338–42. 10.1136/sti.2008.030486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Scott Lamontagne D, Baster K, Emmett L, et al. . Incidence and reinfection rates of genital chlamydial infection among women aged 16–24 years attending general practice, family planning and genitourinary medicine clinics in England: a prospective cohort study by the Chlamydia Recall Study Advisory Group. Sex Transm Infect 2007;83:292–303. 10.1136/sti.2006.022053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Walker J, Tabrizi SN, Fairley CK, et al. . Chlamydia trachomatis incidence and re-infection among young women—behavioural and microbiological characteristics. PLoS One 2012;7:e37778 10.1371/journal.pone.0037778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Davies B, Anderson S-J, Turner KME, et al. . How robust are the natural history parameters used in Chlamydia transmission dynamic models? A systematic review. Theor Biol Med Model 2014;11 10.1186/1742-4682-11-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Garnett GP, Bowden FJ. Epidemiology and control and curable sexually transmitted diseases: opportunities and problems. Sex Transm Dis 2000;27:588–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Quinn TC, Gaydos C, Shepherd M, et al. . Epidemiologic and microbiologic correlates of Chlamydia trachomatis infection in sexual partnerships. JAMA 1996;276:1737–42. 10.1001/jama.1996.03540210045032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Reekie J, Donovan B, Guy R, et al. . Risk of pelvic inflammatory disease in relation to Chlamydia and gonorrhea testing, repeat testing, and positivity: a population-based cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2018;66:437–43. 10.1093/cid/cix769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Davies B, Turner KME, Leung S, et al. . Comparison of the population excess fraction of Chlamydia trachomatis infection on pelvic inflammatory disease at 12-months in the presence and absence of chlamydia testing and treatment: systematic review and retrospective cohort analysis. PLoS One 2017;12:e0171551 10.1371/journal.pone.0171551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

sextrans-2018-053823supp001.pdf (444KB, pdf)

sextrans-2018-053823supp002.pdf (679.1KB, pdf)