Abstract

Objective

We describe the use of an integrated knowledge translation (KT) approach in the development of the CONsolidated Standards Of Reporting Trials extension for equity (‘CONSORT-Equity 2017’), and advisory board-research team members’ (‘the team’) perceptions of the integrated KT process.

Design

This is an observational study to describe team processes and experience with a structured integrated KT approach to develop CONSORT-Equity 2017. Participant observation to describe team processes and a survey were used with the 38 team members.

Setting

Use of the CONSORT health research reporting guideline contributes to an evidence base for health systems decision-making, and CONSORT-Equity 2017 may improve reporting about health equity-relevant evidence. An integrated KT research approach engages knowledge users (those for whom the research is meant to be useful) with researchers to co-develop research evidence and is more likely to produce findings that are applied in practice or policy.

Participants

Researchers adopted an integrated KT approach and invited knowledge users to form a team.

Results

An integrated KT approach was used in the development of CONSORT-Equity 2017 and structured replicable steps. The process for co-developing the reporting guideline involved two stages: (1) establishing guiding features for co-development and (2) research actions that supported the co-development of the reporting guideline. Stage 1 consisted of four steps: finding common ground, forming an advisory board, committing to ethical guidance and clarifying theoretical research assumptions. Bound by the stage 1 guiding features of an integrated KT approach, stage 2 consisted of five steps during which studies for consensus-based reporting guidelines were conducted. Of 38 team members, 25 (67.5%) completed a survey about their perceptions of the integrated KT approach.

Conclusions

An integrated KT approach can be used to engage a team to co-develop reporting guidelines. Further study is needed to understand the use of an integrated KT approach in the development of reporting guidelines.

Keywords: health equity, reporting guidelines, consort, integrated knowledge translation, collaborative research, research co-creation

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Reporting guidelines in health research improve and contribute to a robust evidence base for health systems decision-making.

Integrated knowledge translation (KT) is an approach to research that structures the engagement of knowledge users, meaning those for whom the research is meant to ultimately be of use, with researchers to facilitate the co-development of knowledge.

An integrated KT approach was used to engage knowledge users with researchers as a team, to develop the CONsolidated Standards Of Reporting Trials extension for equity (‘CONSORT-Equity 2017’) reporting guideline.

Limitations are that the use of an integrated KT approach includes the logistics of including a range of people and the management of views.

The strengths include that the integrated KT approach allows consideration and inclusion of a range of views; an integrated KT approach can be used to engage a team to co-develop reporting guidelines.

Introduction

Reporting guidelines in health research are important, as they improve and contribute to a more robust evidence base for health systems decision-making.1 2 There is a significant amount of avoidable waste in research,3 and part of this waste can be attributed to potentially useful research findings being disregarded because of inadequate reporting, which reporting guidelines can help address. Defined as a tool for use by health researchers to structure manuscript writing, reporting guidelines consist of minimal lists of information to ensure that a manuscript can be understood by a reader, replicated by a researcher, used by a clinician to make a clinical decision and included in a systematic review.4 The use of reporting guidelines in health research may improve completeness and transparency of reported evidence from research studies. Many examples of reporting guidelines can be found at the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute’s Centre for Journalology site at http://www.ohri.ca/journalology/docs/guidelines.aspx,5 as well as the Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of Health Research (EQUATOR) network site at https://www.equator-network.org/.4

The internationally recognised CONsolidated Standards Of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement is an evidence-based guideline consisting of 25 items to encourage completeness and transparency in reporting of randomised controlled trials (‘randomized trials’). CONSORT is in the form of a checklist and flow diagram.6 The checklist focuses on reporting how the randomised trial was designed, analysed and interpreted, and the flow diagram depicts participant progress through the randomised trial processes. Extensions to the CONSORT statement have been developed for specific issues (eg, pragmatic trials, non-pharmacological therapies, and social and psychological interventions).4 No extension has yet been developed to report items to assess the effects of an intervention on health equity.7

Striving for health equity is a matter of social justice and implies that everyone can attain their health potential and that no one is disadvantaged by their social positioning or other socially determined circumstances.8 Randomised trials are a powerful design for determining the relative impact of an intervention.9 Nevertheless, for randomised trials to contribute effectively to policies that promote health equity, there remain challenges to overcome.10 For example, poor reporting of equity considerations for randomised trials can have undesired effects on health systems’ organisational practices and policies, clinical and public care. Additionally, some interventions can even aggravate and/or undermine health equity.11 Reporting guidelines are needed to support the consideration of equity in the conduct of and communication about randomised trials.

‘Knowledge users’ are those who influence, administer and/or who are active users of healthcare systems, and who for our study were identified as potential holders of expertise about or relevant to health, research and/or reporting guidelines. ‘Engagement’ is defined here as an arrangement with knowledge users in the governance of the research process to co-lead research and that leads to co-development of knowledge (beyond being a research participant).12 While the engagement of knowledge users has been identified as important for clinical guideline development,13 14 a recent review of clinical guidelines shows that there is evidence for low levels of such engagement.15 Achieving consensus among developers of health research guidelines has been identified as important,16 but there is little information on how to achieve consensus when involving interdisciplinary knowledge users that include patients and members of the public in reporting guideline development.17

‘CONSORT-Equity 2017’

Wishing to produce the highest quality reporting guideline and recognising that the uptake of the resulting reporting guideline would be critical to improving the reporting of future randomised trials,18 between 2015 and 2017, an interdisciplinary group of knowledge users and researchers came together as an advisory board-research team (‘the team’) to develop an equity extension of CONSORT, ‘CONSORT-Equity 2017’.7

Of particular concern to the team was the need to prompt careful consideration of the knowledge translation (KT) issues that might promote uptake of the final reporting guideline product (ie, the equity extension of the CONSORT guideline). ‘Knowledge translation’ is a term used to refer to processes that bridge the ‘know-do’ gap, which is defined as the gap between what is learned from research and the implementation of what is learned by knowledge users, with the aim to improve health delivery systems and health outcomes.19 Initially, know-do gaps (eg, uptake of reporting guidelines) were considered simply a problem of knowledge transfer,20 and it was thought that end users only needed to become aware of the knowledge and they would then implement it. Understandings of the causes of know-do gaps continue to evolve, and now these gaps are considered to be more of a knowledge production problem (the knowledge being produced does not meet the needs of those who should be using it). Taking this later perspective, addressing the know-do gap requires researchers to begin thinking of KT before knowledge is created.21 22 Proposed as an approach to address the issues of knowledge production and application,21 22 ‘integrated knowledge translation’ (integrated KT) is also identified as an approach that is more likely to lead to the practical application of knowledge.20 23 The engagement of knowledge users in co-developing the research means the findings are more likely to be useful, usable and used.21 22 As there are issues with the uptake of reporting guidelines,6 an integrated KT approach is appropriate for the development of reporting guidelines.

Given the presumed benefits of an integrated KT approach and the desire to maximise the quality, usefulness and use of the reporting guideline, the team decided to adopt an integrated KT approach for the development of the CONSORT- Equity 2017 reporting guideline. In the case of CONSORT-Equity 2017, potential knowledge users of the reporting guideline were identified from a broad range of disciplines. These knowledge users are involved in research-related activities and disciplines such as clinical epidemiology, economics, social science, public health, international development, KT, patients or patient organisations (‘patients’), and members of the public, and so were invited to engage in the research to develop the reporting guideline.

The objective of this paper is to describe the use of an integrated KT approach in the development of the CONSORT-Equity 2017 reporting guideline and team members’ perceptions of the integrated KT process.

Methods

We adopted an observational study design involving participant observation supplemented with a survey of team members. We produced a description of team processes and experiences with the structured integrated KT approach used to develop the CONSORT-Equity 2017 reporting guideline.7 The research stages followed in developing the reporting guideline are described in detail in a published protocol.7 Participant observation is a qualitative and interactive process that connects to human experience through immersion and participation in a particular context.24 The processes to develop CONSORT-Equity 2017 were structured by a framework that depicts integrated KT, called the Collaborative Research Framework (‘framework’).25

The framework was selected as appropriate for use as engagement of knowledge users with researchers throughout the development of CONSORT-Equity 2017 was a priority. The framework was originally developed to describe the collaborative processes of work conducted by researchers in full partnership with an Indigenous community to culturally adapt a shared decision-making tool through research processes of development, conduct and dissemination.25 The framework consists of two stages that involve knowledge users and researchers agreeing to establish the parameters of the study (forming an advisory body, agreements on the approach to ethics and theoretical assumptions in the research) and then the conduct of the study with the knowledge users and researchers in full partnership throughout all the steps of a series of studies. The framework describes structured processes of negotiation within the study partnerships. It stresses the importance of engaging knowledge users as full partners with researchers in a team.25 We describe the study processes of CONSORT-Equity 2017 in relation to the framework that depicts integrated KT.

We used the framework to guide the development of CONSORT-Equity 2017 and to organise documented observations and events that describe the development of CONSORT-Equity 2017.26 At the completion of the study, a survey was conducted with team members about their perceptions of the integrated KT approach.

A survey was developed for team members to gather their feedback on the experience with the integrated KT approach. In consultation with an integrated KT expert (IDG), an eight-question online survey consisting of two Likert questions with an option for an open-ended comment and six open-ended questions about experience with integrated KT during the CONSORT-Equity 2017 study was developed and pilot-tested. The survey questions were designed to evoke understandings of the team experiences, with the two Likert questions about the extent to which team members felt they were engaged and their satisfaction with engagement. The open-ended questions were aimed at soliciting details on the experience with integrated KT during the CONSORT-Equity 2017 study. The team members were asked to participate in a survey following the development of the CONSORT-Equity 2017 reporting guideline. There were 38 individuals invited to participate in the survey, with one declining to be invited to participate due to personal time constraints.

Following a process of informed consent, the survey was administered in July 2017 to the team members. The frequency of the responses to the two Likert questions was tabulated. To analyse participant responses to the six open-ended survey questions, a process of inductive content analysis was used, which involves segmenting responses by topics and into categories. For the analysis of these responses, each question was considered to be a topic and the responses and development of codes defined the content in each category.27 One researcher conducted the content analysis process (JJ) and was confirmed by a second reviewer (MY).

Patients and public involvement

Patients (ie, patients and members of the public) were members of the team involved in the design, conduct and reporting of the work to develop CONSORT-Equity 2017. As patients were members of the CONSORT-Equity 2017 team, patient priorities, experience and preferences informed the development of research questions, design of the study and the outcome measures that are reported in this document to describe the research processes of CONSORT-Equity 2017. Patients are also identified as coauthors or acknowledged on the work presented here. The roles and membership of the team are reported in the study protocol and final product documents.7 17 18 28 For this reason, the work that is presented here is an example of how to conduct and report on the development of reporting guidelines in ways that include patients and which reflect their priorities, experiences and preferences.29

Results

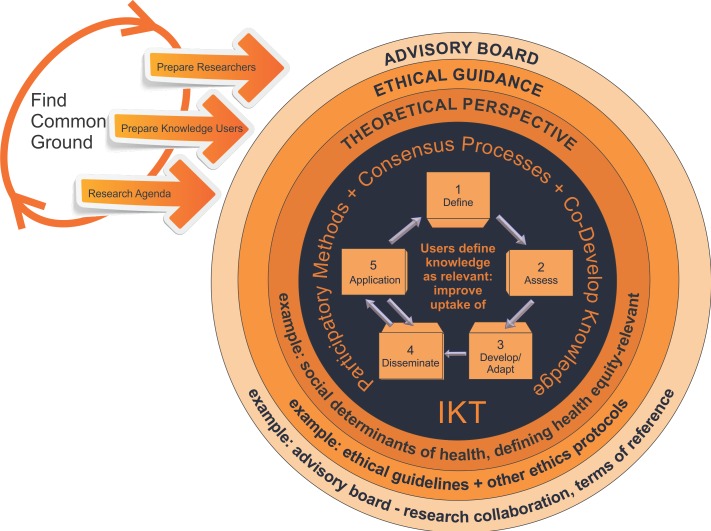

The development of CONSORT-Equity 2017 used an integrated KT approach to structure replicable steps: to conduct research in a collaborative manner that uses consensus-building methods and involves co-development of knowledge25; and to develop a reporting guideline for equity (CONSORT-Equity 2017). The process for co-developinging the reporting guideline involved two stages: (1) establishing guiding features for co-development and (2) engaging knowledge users and researchers (the team) in research actions that supported the co-development of the reporting guideline (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Integrated knowledge translation (IKT) approach for CONsolidated Standards Of Reporting Trials extension for equity (CONSORT-Equity 2017).

Stage 1: establishing guiding features for co-development

Preparation: finding common ground

Initiating a process to engage researchers with potential knowledge users in the development of CONSORT-Equity 2017 involved discussions with individuals and meetings: (1) determining if and how knowledge users’ interests and concerns align with those of researchers; (2) building relationships among knowledge users and researchers; and (3) defining the parameters of a team relationship for knowledge users and researchers to find common ground and collaborate as a team on a project to develop CONSORT-Equity 2017.25

Finding common ground was an iterative three-step process that involved the preparation of a research team. The research team consisted of researchers and knowledge users who chose to work together to produce an agreed-upon research agenda. Two research members (VAW, PT) initially recognised the interest and need to extend a reporting guideline, CONSORT, for equity. Next, these research members identified potential research team members who shared concerns about equity in health systems, and so relationships were built and a rudimentary research team was formed. The members of the growing research team defined the objectives and parameters of a reporting guideline project in a proposal that was submitted for funding. Following the success of the funding proposal, the iterative three-step process was then engaged in again by the research team to ensure inclusion of team members with a broad range of skills and expertise.

An advisory board was formed

Collaboration with knowledge users during the development of CONSORT-Equity 2017 was identified as an important feature of the study by the research team, and a decision was made to form an advisory board consisting of the intended users of the reporting guideline. There was a deliberate effort to define roles and recruit nine members to the advisory board: journal editors, trialists, bioethicists, patients, clinicians, systematic review authors, policy makers and funders. The advisory board is described in detail elsewhere.7 The need to ensure effective communication within and between the members of the advisory board and research team was identified, and two members of the research team were selected as facilitators: one with the advisory board (JJ) and the other with the research team (VAW).

The advisory board facilitator (JJ) worked with the advisory board members to define terms of reference and that included expectations (eg, meetings, types of contributions) and opportunities (eg, authorship guidelines) (table 1). The facilitators (JJ, VAW) worked to make plans and schedule events that created opportunities for the advisory board-research team (collectively referred to as ‘the team’) to function in a partnership to promote inclusion and respect for a multiplicity of views in the CONSORT-Equity 2017 study. Engagement between team members created opportunities to explore concepts related to health equity, and the results were reflected in products (eg, a tool to identify when a randomised trial is health equity-relevant18). Finally, the members of the team defined and agreed on an agenda for the study which was published in a study protocol.7

Table 1.

Terms of reference

| Role of advisory board membership |

|

| Method and frequency of communication |

|

| Description of workload |

|

| Timelines |

|

| How advice will be managed |

|

| Authorship |

|

Commitment to ethical guidance

The members of the team agreed to collaborate and engage in decisions about how to structure the development of the reporting guideline so that there was adherence to ethical guidelines. The aim was to ensure respect for and representation of a broad range of views through agreements, structured communication and consensus-building processes.18 The team agreed to adhere to Canadian ethical research guidelines during the conduct of the CONSORT-Equity study.30

Theoretical perspective clarified

The poor quality or absence of evidence about health equity is identified by policy makers as a key limitation of research.31 The team identified the lack of consensus on the use of terminology related to health equity concepts and the importance of underpinning assumptions as critical to the development of the reporting guideline. Therefore, the members of the team sought to clarify terminology and relate these understandings in publications to define the study parameters.7 18 The team reflected on the underpinning assumptions throughout the reporting guideline development process (eg, a focus on social determinants of health theory, revisiting and reflecting on meanings of health equity, and so on).

Stage 2: research actions that supported the codevelopment of the reporting guideline

Reporting guideline development process

The agreed-upon guiding features of the research approach (stage 1) were used to structure the multiphase (stage 2) CONSORT-Equity 2017 study to accomplish objectives and create products over a 2-year timeframe (table 2). Participatory methods in the form of facilitated online and inperson team meetings were used to promote consensus building among team members, and this resulted in the co-development of knowledge in the form of a reporting guideline.

Table 2.

Stages in the development of CONSORT-Equity 2017 update terms

| Stage 1: establish guiding features | Example |

| 1. Find common ground. | A process to initiate and develop a collaborative work plan that for CONSORT-Equity 2017 was an iterative three-step process to prepare a research team. |

| 2. Form an advisory board. | Defined advisory board roles, accessed networks to recruit advisory board members; terms of reference to structure relationships within and between the advisory board-research team members (‘the team’) (table 1). Set an agreed-upon agenda that eventually resulted in a published protocol.7

Consensus-building processes promoted engagement in active debate and co-development of knowledge that resulted in, for example, defining and validating when a randomised trial is health equity-relevant.18 |

| 3. Commit to ethical guidance. | The team agreed on study conduct to adhere to ethical guidelines (in Canada, the Tri-Council Policy Statement V.2)45 and that could include other research ethics protocols or requirements considered relevant by team members, such as the example of research conduct with Indigenous people.46 47 |

| 4. Clarify theoretical perspective. | CONSORT-Equity 2017 is premised on understandings of key concepts, their definitions and usage by the team: understandings of health equity and agreements among team members about underpinning assumptions: the role of social determinants of health theory, a definition of ‘health equity’, defining a health equity-relevant randomised trial and when there is a health disadvantage, and that are reflected in publications.7 18 |

| Stage 2: research actions that supported the co-development of the reporting guideline. Reporting guideline development process steps. |

The five reporting guideline development steps of stage 2 are bound by the guiding features of stage 1. |

| 1. Define. | Establish guideline need with the team: team members were engaged in a process to determine whether and how they might collaborate to develop an extension of CONSORT for equity. Following funding, further work among the team members resulted in a published protocol7 and a tool that determines when a randomised trial is health equity-relevant18 and so should use a reporting guideline for health equity. |

| 2. Assess. | Determine the state of the literature7 28 32: consultation with experts on health equity and this included the use of key informant interviews with interdisciplinary knowledge users.17 |

| 3. Develop/Adapt. | Propose and debate adaptation of the reporting guideline: identification of potential guideline knowledge users from high-income, middle-income and lower-income countries that include, for example, patients and methodologists, and who were invited to participate in an online Delphi study to identify items for the reporting guideline.28 Then, a consensus meeting (the 2016 Boston Equity Symposium which included guideline knowledge users) was held to discuss and debate evidence for inclusion in CONSORT-Equity 2017.28 |

| 4. Disseminate. | Develop and execute plan for uptake of the reporting guideline. Outcomes are reflected in the success of an invitational study meeting (the 2016 Boston Equity Symposium) and co-authored publications,17 18 28 32 33 and the CONSORT-Equity 2017 checklist elaboration and explanation.28 48 |

| 5. Apply. | A process of road-testing the reporting guideline: work is under way to further disseminate and promote the application of the CONSORT-Equity 2017 guideline. |

CONSORT-Equity 2017, CONsolidated Standards Of Reporting Trials extension for equity.

The team co-developed the CONSORT-Equity 2017 following the methodology for consensus-based reporting guideline development advanced by Moher et al 16 and with the innovation of key informant interviews.17 The following are the five steps in reporting guideline development: (1) define (establish guideline need within the team; (2) assess (state of the literature, consultation with experts on health equity); (3) develop/adapt (propose and debate adaptation of the reporting guideline); (4) disseminate (develop and execute plan for uptake of the reporting guideline); and (5) apply (process of road-testing the reporting guideline).

Extent of knowledge user engagement

The use of the integrated KT approach facilitated engagement within the team by creating structures and opportunities for all team members to offer their views for the development of CONSORT-Equity.17 28 We failed to engage with one advisory board member due to time constraints around their ability to participate, and it was not possible for every member of the team to have their views accommodated, and some members chose to remove themselves from participation either temporarily or permanently (n=2). As well, it was not possible (and indicated as not desirable by members of the team) for every team member to participate in every step of the guideline development process, although opportunities to participate were actively welcomed and sought by the facilitators. For the development of the CONSORT-Equity 2017 reporting guideline, there are publications (see table 2) that document descriptions of the particular study processes and that include identification of who and how the team members were involved.7 18 28 32 33

As collaboration and consensus-building methods were a central feature in CONSORT-Equity 2017 development, it was important to understand the experiences of those who were involved in the reporting guideline development. An eight-question online survey consisting of two Likert questions with an option for an open-ended comment and six open-ended questions about the experience with an integrated KT approach during the CONSORT-Equity 2017 study was administered to team members. Twenty-four of the 37 team members responded to the first two Likert questions on the survey (response rate of 65%) (table 3). When asked ‘Overall, how would you rate the extent to which the research team engaged you in the study? (Where 1 is not at all satisfied and 5 is totally satisfied)’, 18 of 24 (75%) surveyed respondents indicated ‘very or totally satisfied’. The following is an illustrative quote: “I had a concrete role in the process and the team was very respectful and considerate of input so it was easy to feel invested.” In response to the second Likert question ‘How satisfied are you with the level of your engagement with the research team? (Where 1 is not at all satisfied and 5 is totally satisfied)’, 21 of 24 (87.5%) respondents indicated ‘very or totally satisfied’. The following is an illustrative quote from this response: “[I would] be happy (very) if all research teams engaged all participants in the same manner.”

Table 3.

Results of two Likert questions on a team survey about experience with integrated knowledge translation approach (n=24)

| Question | Response category | Illustrative quote from open-ended comments | ||||

| Overall, how would you rate the extent to which the research team engaged you in the project? (n=24) | 1 (not at all satisfied): n=0 (0%) | 2 (somewhat satisfied): n=2 (8%) |

3 (satisfied): n=4 (16.6%) | 4 (very satisfied): n=3 (12.5%) | 5 (totally satisfied): n=15 (62.5%) | “I had a concrete role in the process and the team was very respectful and considerate of input so it was easy to feel invested.” |

| How satisfied are you with the level of your engagement with the research team? (n=24) | 1 (not at all satisfied): n=1 (4%) | 2 (somewhat satisfied): n=0 (0%) |

3 (satisfied): n=2 (8%) | 4 (very satisfied): n=3 (12.5%) | 5 (totally satisfied): n=18 (75%) | “(I would) be happy (very) if all research teams engaged all participants in the same manner.” |

In the portion of the survey that included six open-ended questions, respondents were asked to provide details about their experience with the integrated KT approach during the development of the CONSORT-Equity 2017 reporting guideline. Frequency counts of the type of responses were recorded and are reported in table 4 with illustrative quotes.

Table 4.

Results of six open-ended questions on a team survey about experience with an integrated knowledge translation approach (n=25)

| Question | Response |

| 1. What do you perceive as the benefits of an integrated KT approach to develop a reporting guideline extension of CONSORT for equity? | 1. Allows consideration and inclusion of a range of views (14/25, 56%): “Capturing a multitude of perspectives, to enhance relevance and acceptability of reporting guidelines across disciplines.” 2. Fosters engagement in study processes (6/25, 24%): “It allows participation and engagement of various stakeholders at all stages of the project for whom the guideline is relevant.” 3. Enhances guideline uptake (5/25, 20%): “Results are more likely to be adopted and applied.” |

| 2. Do you think that the team faced any challenges in the study as the result of the integrated KT approach? | 1. The logistics of including a range of people in the team (8/25, 32%): “Takes more time to work with a large and diverse crowd.” 2. Management of views (5/25, 20%): “Because of the wide range of different disciplines present, it may have been difficult to engage all participants equally across all issues.” 3. Reconciliation of within-team differences (3/25, 12%): “It is difficult to deal with perhaps conflicting and at times unclear opinions.” 4. Unaware of any team challenges (9/25, 36%): “Not that I’m aware of.” |

| 3. Did you face any challenges in the study as the result of the integrated KT approach? | 1. No personal challenges faced in the study (19/25, 76%): “I did not face any challenges. My input and participation had equal standing in the process.” 2. The personal experience of challenge related to the pace, number of consultations and/or to provide informed opinions (6/25, 24%): “It was slow at times and a bit frustrating. We achieved what we did through patience, persistence and good will of team members.” |

| 4. What do you consider to be the impact(s) of using an integrated KT approach with the study? | 1. Improves the final guideline product (11/25, 44%): “I feel that we produced a product that was relevant to all of our team members, and that they can support in their communities.” 2. Inclusion of different forms of knowledge (11/25, 44%): “It ensures that the study is better informed by the expertise, perspectives and needs of the different stakeholders.” 3. Unsure/did not notice impact of integrated KT approach (3/25, 12%): “Not sure.” |

| 5. Would you have changed anything about how the integrated KT approach was used in the study? If yes, how? | 1. Would not change the use of the integrated KT approach (8/15, 53%): “No change suggested.” 2. Greater range of participants (3/15, 20%): “I would have tried to broaden the scope of stakeholders.” 3. Narrow the stakeholder focus and seek more intense consultations, such as through inperson meetings (2/15, 13%): “Smaller reach, deeper consultation.” 4. More time (2/15, 13%): “More time is always a benefit to measure the impact.” |

| 6. Do you have any additional comments? | 1. No comment (19/25, 76%). 2. Indicated that it was a positive experience (6/25, 24%): “I would do this again.” |

CONSORT, CONsolidated Standards Of Reporting Trials; KT, knowledge translation.

When participants were asked what they perceived as the benefits of an integrated KT approach (question 1), the most common (14/25, 56%) response described integrated KT as an approach that allows multiple voices/opinions to be heard and considered. In response to being asked about whether they thought that the team faced any challenges in the study as the result of the integrated KT approach (question 2), many participants (8/25, 32%) reported that the logistics involved with including a lot of people was a challenge, but a slightly larger number (9/25, 36%) reported that they were unaware of any team challenges. When asked about whether they faced any challenges during the development of the reporting guideline as the result of the integrated KT approach (question 3), the vast majority of participants (19/25, 76%) indicated that they did not face any challenges.

Participants were asked what they considered to be the impact(s) of using an integrated KT approach with reporting guideline development (question 4), and many (11/25, 44%) indicated that an integrated KT approach improved the relevance of the final guideline product, and 11 of 25 (44%) reported that the work to develop CONSORT-Equity 2017 was better informed. When asked if they would change anything about how the integrated KT approach was used (question 5), few participants provided a response (n=15), and of those who did indicate a response, most participants (8/15, 53%) indicated that they would not have changed anything. Finally, when asked for additional comments (question 6), while most respondents (19/25, 76%) provided no comments, some (6/25, 24%) reported that the integrated KT process was a positive experience (table 4).

During the development of CONSORT-Equity 2017, team members were found to be more engaged in particular activities in relation to their knowledge, occupational roles and in relation to life events. For example, some team members were found to play a larger role when the team activities required expertise held by team members (eg, expertise about health equity, the conduct of randomised trials and so on). The development of the CONSORT-Equity 2017 reporting guideline was voluntary for most team members—and was unpaid work—and so other employment or volunteer commitments may have influenced the ability of team members to participate in meetings. As well, personal factors (eg, health issues, family events, travel plans) had impact on the participation of team members in the development of CONSORT-Equity 2017.

Discussion

A team engaged in mutually agreed-on processes to co-develop knowledge and assemble empirical evidence to develop a reporting guideline, CONSORT-Equity 2017. The team was established to function as a partnership throughout the study process to promote inclusion and respect for a range of views. A structured integrated KT approach was used to organise ongoing negotiations among team members and used replicable steps to develop a reporting guideline. The aim was to ensure that the team’s agreed-on goals were achieved: to conduct research in a collaborative manner that uses consensus-building methods and involves co-development of knowledge; and to develop a reporting guideline for equity (CONSORT-Equity 2017) as a contribution to address health systems’ equity issues.

Perceptions of the integrated KT approach and impacts on co-development of knowledge

Our study involved a 38-member interdisciplinary team from eight countries that included patients and who collaborated in the development of CONSORT-Equity 2017. Details on the team members and processes are reported in detail elsewhere.7 28 There is little evidence in the literature about the experiences of interdisciplinary teams that include journal editors, trialists, bioethicists, patients, clinicians, systematic review authors, policy makers and funders. Previous studies that investigate patient perspectives on clinical guideline development concluded that effective engagement in the development process requires planning, and the recommendations arising from that work include the use of smaller and diverse groups, with no prior relationships with other members of the team; individual and group preparation for engagement on the team; and an identified contact person for participants.34 In our study, we prepared an interdisciplinary and international team to work together in the development of a reporting guideline.

Many options exist to facilitate collaboration within research partnerships and that foster democratic approaches to knowledge development.23 35–37 An integrated KT approach was identified as appropriate for our team and its proposed development of a reporting guideline, as it focuses on the codevelopment of knowledge with practical applications.23 Furthermore, we found that during the development of the reporting guideline, an integrated KT approach supported many opportunities for team members to be fully involved in the entire research process as planned during the CONSORT-Equity 2017 protocol development.7 The integrated KT approach began with an iterative process of preparation of team members for participation in a research partnership, a feature reported in other frameworks that structure engagement of knowledge users with researchers in health research.36 38 39 The members of the team involved in the development of CONSORT-Equity 2017 were invited to participate in all phases of the reporting guideline development process, and efforts were made by facilitators to accommodate their participation.

The value of knowledge user engagement during the reporting guideline development is asserted in a substudy that was conducted with interdisciplinary key informants. This study, which engaged key informants in interviews about their views and suggestions for an extension of CONSORT for equity, was found to generate new concepts that contributed to the development of CONSORT-Equity 2017.17 We prioritised the engagement of team members throughout the development of CONSORT-Equity 2017 to improve the likelihood that CONSORT-Equity 2017 would be perceived as useful and applicable in practice. To strive for authentic (ie, ethical, equitable) engagement, deliberate efforts were made to foster relationships within a team that consisted of knowledge users and researchers.

The successful engagement of team members was possibly due to the structured integrated KT approach that fostered processes of negotiation and created opportunities for team members to choose their level of engagement. For example, there were ongoing opportunities for members of the team to engage at different stages of the CONSORT-Equity 2017 study. These opportunities were initially identified during the preparation for the development of CONSORT-Equity 2017. The iterative and prolonged focus on preparation of team members led to the development of a shared agenda for the work to develop CONSORT-Equity 2017. The finding of a focus on iterative preparation of team members is an innovation on the original framework used to guide the integrated KT approach (figure 1). The opportunity to prepare team members to engage in the CONSORT-Equity 2017 study and to work together led to opportunities to develop and make shared understandings and agreements explicit. The team facilitators built on the success of the initial engagement of team members in the reporting guideline development, and created frequent and varied opportunities for ongoing participation in the CONSORT-Equity 2017 study processes (eg, through scheduled face-to-face and/or telephone calls, maintained regular email study updates).

The experience with varied levels of engagement by team members in the CONSORT-Equity 2017 study led to consideration of the meaning of ‘engagement’ among an interdisciplinary team consisting of knowledge users and researchers. Overall, our team consisted of a committed group of team members who were involved in a collaborative effort for the duration of the work to develop CONSORT-Equity 2017. Team members met and agreed on objectives, and this in turn resulted in co-developed products. During the series of CONSORT-Equity 2017 studies, the nature and degree of engagement varied over time and according to the capacity of team members and study tasks. Team members asked to be kept informed but did not want to actively participate (eg, one-way direction of information updates on the study, such as an email with announcements); be consulted for feedback (eg, responding to an email request for information or feedback on a document); play a supportive role for others who provide governance in the CONSORT-Equity 2017 study processes (eg, providing support in a study in response to requests by team leads); and share in the governance of the study (eg, advising and/or decision-making in a co-leading role, such as in the development of CONSORT-Equity 2017 study directions or products. The different levels at which knowledge user engagement may occur has been under examination for many years, and one of the earliest instances is Arnstein’s 1969 ladder of participation and that ranges from non-participation to citizen control.40 Since then there have been many other ways of conceptualising knowledge user engagement in research.41–43

During our CONSORT-Equity 2017 study, we accomplished the engagement of team members that included knowledge users in study governance—and then exceeded this aim with knowledge user leadership. There are documented instances of varied team members taking the lead during the CONSORT-Equity 2017 study conduct and that occurred during meetings (eg, expert knowledge user leads taking initiative with and guiding sessions at the Boston Equity Symposium) and with study publications.33 The range of engagement that was observed during the CONSORT-Equity 2017 study processes demonstrates that engagement may be more changeable, nuanced and less able to be anticipated than is currently described in the literature encouraging knowledge user engagement.12 42 The use of the structured integrated KT approach allowed members of the team to determine how and in what capacity they would contribute, while also being engaged to co-develop a reporting guideline.

Limitations and strengths for use of an integrated KT approach to develop a reporting guideline

The surveyed team members identified the main limitations (challenges) of an integrated KT approach to be the logistics of including a range of interdisciplinary team members in the study and the management of team views. The team facilitators reflected on the logistics and the challenges of scheduling meetings to accommodate or align with team member commitments (outside of CONSORT-Equity 2017) and time constraints for those on the team to participate in the study. As well, there may have been impacts on the participation of team members due to the reliance on the facilitators who were based at one site and responsible for fostering regular and productive contacts, and with the use of online communications (vs face-to-face meetings). For example, communication between and within those on the team was a challenge due to the logistics of time zones, the number of people and limitations of technology. These challenges were further complicated by the need to bring team member views together in consensus to achieve CONSORT-Equity 2017 study objectives.

The surveyed team members identified the main strength of the integrated KT approach to be the consideration and inclusion of a range of views in the research process. The facilitators of the team reflected on the use of study processes structured by the integrated KT approach that, for the duration of the study, made it possible to build and/or strengthen research relationships initiated at the start of the study and across a range of team members. These research relationships were demonstrated by team member participation in publication coauthorship, attendance at regular meetings, email contacts and feedback on products.

Limitations and strengths of the study to evaluate an integrated KT approach

The limitations of the study about the use of an integrated KT approach reported in this paper include that the work to evaluate the use of an integrated KT approach (the observational study) was done with a smaller group of interdisciplinary team members and that team members already shared an interest in taking an integrated KT approach in the development of a reporting guideline (CONSORT-Equity 2017). For this reason, the findings about the integrated KT process presented here may not be relevant to other teams that consist of a different groups of team members and that have different team objectives. In addition, the methods we used are observational and not established for use with teams who are engaged in a multiple series of studies to develop an end product (in our instance, a reporting guideline). The strengths are that we used a previously developed framework25 to structure our reporting about the use of an integrated KT approach. As well, we successfully engaged an interdisciplinary team throughout the guideline development process and were able to evaluate the process.

Conclusions

A structured integrated KT approach was successfully used to engage an interdisciplinary and international team to develop a reporting guideline, CONSORT-Equity 2017. The use of an integrated KT approach fostered engagement of the team in the study processes and prompted deliberation and consensus building among team members. Further work is needed to examine and better understand the use and potential applications of an integrated KT approach to other initiatives seeking to improve research reporting guidelines.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the following individuals for their support and encouragement: Mark Petticrew, Jeremy Grimshaw, Charles Weijer, Monica Taljaard and Yukiko Asada.

Footnotes

Contributors: JJ, IDG, VAW conceived and led the design of the work described in the manuscript and were responsible for the first and final drafts of this manuscript. All authors participated in and provided substantial contributions to the analysis and interpretation during development of the work described in the manuscript. JJ led the writing of the first version of the manuscript. JJ and IDG revised the manuscript. All authors made contributions to the drafts of this manuscript (including the listed members of the CONSORT-Equity 2017 and Boston Equity Symposium) and have reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: JJ held a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Postdoctoral Fellowship for a portion of the time she was writing the paper. IDG is a recipient of a CIHR foundation grant (FDN# 143237).

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work, with the following exceptions: (1) LGC reports he works as a Senior Advisor for Health Systems Research to the Pan American Health Organization/WHO. His Organization’s Policy on Research for Health calls for the development and use of research reporting standards and improving the value and impact of research for health. His opinions and contributions to this manuscript are his own and do not necessarily reflect the decisions or policies of his employer. (2) DM reports that he is one of the ‘inventors’ of CONSORT. (3) VAW reports grants from Canadian Institutes of Health Research, grants from Ontario Early Career Researcher Award, during the conduct of the study.

Ethics approval: Participants gave informed consent before taking part in the study of the integrated KT approach used in the development of the CONSORT-Equity 2017 reporting guideline reported in this manuscript. Research ethics approval was obtained from the Bruyère Research Ethics Board (Bruyère REB Protocol #M16-15-042).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

Collaborators: Collaborating authors who are identified as a member of the CONSORT-Equity and Boston Equity Symposium participants are as follows: Rebecca Armstrong, Sarah Baird, Yvonne Boyer, Luis Gabriel Cuervo, Regina Greer-Smith, Anne Lyddiatt, Jessie McGowan, Lawrence Mbuagbaw, Tomas Pantoja, Beverly Shea, Bjarne Robberstad, Howard White and George Wells.

References

- 1. WHO Strategy on Research for Health; WHO Roles and responsibilities on health research: document WHA63.22 and Resolution. 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27. Switzerland: World Health Organization (WHO) Assembly, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pan American Health Organization, DC, 61st Session of the Regional Committee of WHO for the Americas. Policy on research for health: document CD49/10. Washington, DC: PAHO, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Glasziou P, Altman DG, Bossuyt P, et al. Reducing waste from incomplete or unusable reports of biomedical research. Lancet 2014;383:267–76. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62228-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. EQUATOR Network. The EQUATOR Network: Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of Health Research, Centre for Statistics in Medicine (CSM), NDORMS, University of Oxford. UK EQUATOR Centre; n.d. Available from: https://www.equator-network.org/.

- 5. Centre for Journalology. Using Reporting Guidelines Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. 2019. http://www.ohri.ca/journalology/docs/guidelines.aspx.

- 6. Turner L, Shamseer L, Altman DG, et al. Does use of the CONSORT Statement impact the completeness of reporting of randomised controlled trials published in medical journals? A Cochrane review. Syst Rev 2012;1:60 10.1186/2046-4053-1-60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Welch V, Jull J, Petkovic J, et al. Protocol for the development of a CONSORT-equity guideline to improve reporting of health equity in randomized trials. Implement Sci 2015;10:146 10.1186/s13012-015-0332-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Whitehead M. The concepts and principles of equity and health. Int J Health Serv 1992;22:429–45. 10.2190/986L-LHQ6-2VTE-YRRN [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, et al. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ 1996;312:71–2. 10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Marmot M, Allen J, Bell R, et al. Building of the global movement for health equity: from Santiago to Rio and beyond. Lancet 2012;379:181–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61506-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lorenc T, Petticrew M, Welch V, et al. What types of interventions generate inequalities? Evidence from systematic reviews. J Epidemiol Community Health 2013;67:190–3. 10.1136/jech-2012-201257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). Patient Engagement: What is patient engagement? Government of Canada. 2018. http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/45851.html.

- 13. Jarrett L, Patient Involvement Unit. Patient Involvement Unit (PIU). A report on a study to evaluate patient/ carer membership of the first NICE Guideline Development Groups. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE), 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Qaseem A, Forland F, Macbeth F, et al. Guidelines International Network: toward international standards for clinical practice guidelines. Ann Intern Med 2012;156:525–31. 10.7326/0003-4819-156-7-201204030-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Armstrong MJ, Bloom JA. Patient involvement in guidelines is poor five years after institute of medicine standards: review of guideline methodologies. Res Involv Engagem 2017;3:19 10.1186/s40900-017-0070-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moher D, Schulz KF, Simera I, et al. Guidance for developers of health research reporting guidelines. PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000217 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jull J, Petticrew M, Kristjansson E, et al. Engaging knowledge users in development of the CONSORT-Equity 2017 reporting guideline: a qualitative study using in-depth interviews. Res Involv Engagem 2018;4:34 10.1186/s40900-018-0118-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jull J, Whitehead M, Petticrew M, et al. When is a randomised controlled trial health equity relevant? Development and validation of a conceptual framework. BMJ Open 2017;7:e015815 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, et al. Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? J Contin Educ Health Prof 2006;26:13–24. 10.1002/chp.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). Guide to knowledge translation planning at CIHR: integrated and end-of-grant approaches 2015. http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/45321.html. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Van De Ven AH, Johnson PE. Knowledge for Theory and Practice. Acad Manage Rev 2006;31:802–21. 10.5465/amr.2006.22527385 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bowen S, Graham I. Integrated Knowledge Translation : Straus SE, Tetroe J, Graham ID, Knowledge Translation in Healthcare: moving evidence to practice. West Sussex: Wiley, 2013:14–23. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jull J, Giles A, Graham ID. Community-based participatory research and integrated knowledge translation: advancing the co-creation of knowledge. Implement Sci 2017;12:150 10.1186/s13012-017-0696-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Guest GNE, Mitchell ML. Collecting Qualitative Data: A Field Manual for Applied Research. 2013 2019/02/16. 55 City Road, London: SAGE Publications, Ltd; [75-112]. http://methods.sagepub.com/book/collecting-qualitative-data.

- 25. Jull J, Giles A, Boyer Y, et al. Development of a Collaborative Research Framework: The example of a study conducted by and with a First Nations, Inuit and Métis Women’s community and their research partners. ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies 2018;17 (3):671–86. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jull J. CONSORT-Equity Team. The value of an integrated knowledge translation approach for developing reporting guidelines: engaging knowledge users interested in equity-relevant decision making. Ontario, Toronto, Ontario: Knowledge Translation Canada Scientific Meeting Toronto, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Morse J, Field P. Nursing research: the application of qualitative approaches. London: Chapman & Hall, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Welch VA, Norheim OF, Jull J, et al. CONSORT-Equity 2017 extension and elaboration for better reporting of health equity in randomised trials. BMJ 2017;359:j5085 10.1136/bmj.j5085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Staniszewska S, Brett J, Simera I, et al. GRIPP2 reporting checklists: tools to improve reporting of patient and public involvement in research. Res Involv Engagem 2017;3:13 10.1186/s40900-017-0062-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, and Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans. 2018. http://www.pre.ethics.gc.ca/pdf/eng/tcps2/TCPS_2_FINAL_Web.pdf.

- 31. Petticrew M, Whitehead M, Macintyre SJ, et al. Evidence for public health policy on inequalities: 1: the reality according to policymakers. J Epidemiol Community Health 2004;58:811–6. 10.1136/jech.2003.015289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Petkovic J, Welch V, Jull J, et al. How is health equity reported and analyzed in randomised trials: Cochrane Systematic Review Registered Protocol. Cochrane Methodology Review Group 2017. Issue 8. Art. No.: MR000046. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mbuagbaw L, Aves T, Shea B, et al. Considerations and guidance in designing equity-relevant clinical trials. Int J Equity Health 2017;16:93 10.1186/s12939-017-0591-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Armstrong MJ, Mullins CD, Gronseth GS, et al. Recommendations for patient engagement in guideline development panels: A qualitative focus group study of guideline-naïve patients. PLoS One 2017;12:e0174329 10.1371/journal.pone.0174329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. West JF. Public health program planning logic model for community engaged type 2 diabetes management and prevention. Eval Program Plann 2014;42:43–9. 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2013.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. James S, Arniella G, Bickell NA, et al. Community ACTION boards: an innovative model for effective community-academic research partnerships. Prog Community Health Partnersh 2011;5:399–404. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. May M, Law J. CBPR as community health intervention: institutionalizing CBPR within community based organizations. Prog Community Health Partnersh 2008;2:145–55. 10.1353/cpr.0.0019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Johnson DS, Bush MT, Brandzel S, et al. The patient voice in research-evolution of a role. Res Involv Engagem 2016;2:6 10.1186/s40900-016-0020-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jinks C, Carter P, Rhodes C, et al. Patient and public involvement in primary care research - an example of ensuring its sustainability. Res Involv Engagem 2016;2:1 10.1186/s40900-016-0015-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Arnstein SR. A Ladder Of Citizen Participation. J Am Inst Plann 1969;35:216–24. 10.1080/01944366908977225 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. National Institute of Health Research. INVOLVE 2001. https://www.invo.org.uk/. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sheridan S, Schrandt S, Forsythe L, et al. panel) Advisory Panel on Patient Engagement. The PCORI Engagement Rubric: Promising Practices for Partnering in Research. Ann Fam Med 2017;15:165–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Forsythe LP, Ellis LE, Edmundson L, et al. Patient and stakeholder engagement in the PCORI pilot projects: description and lessons learned. J Gen Intern Med 2016;31:13–21. 10.1007/s11606-015-3450-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICJME). Defining the role of authors and contributors. 2018. http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/browse/roles-and-responsibilities/defining-the-role-of-authors-and-contributors.html.

- 45. Panel on Research Ethics. TCPS 2. TCPS 2 (2014)— the latest edition of Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans. http://www.pre.ethics.gc.ca/eng/policy-politique/initiatives/tcps2-eptc2/Default/.

- 46. First Nations Information Governance Centre (FNIGC). The First Nations principles of OCAP®. 2017. http://fnigc.ca/ocap.html.

- 47. Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). CIHR guidelines for Health Research Involving Aboriginal People (2007-2010). 2007. http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/29134.html.

- 48. Simera I, Moher D, Hirst A, et al. Transparent and accurate reporting increases reliability, utility, and impact of your research: reporting guidelines and the EQUATOR Network. BMC Med 2010;8:24 10.1186/1741-7015-8-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.