Abstract

Lactobacillus is a fairly diverse genus of bacteria with more than 260 species and subspecies. Many profiling methods have been developed to carry out phylogenetic analysis of this complex and diverse genus, but limitations remain since there is still a lack of comprehensive and accurate analytical method to profile this genus at species level. To overcome these limitations, a Lactobacillus-specific primer set was developed targeting a hypervariable region in the groEL gene—a single-copy gene that has undergone rapid mutation and evolution. The results showed that this methodology could accurately perform taxonomic identification of Lactobacillus down to the species level. Its detection limit was as low as 104 colony-forming units (cfu)/mL for Lactobacillus species. The assessment of detection specificity using the Lactobacillus groEL profiling method found that Lactobacillus, Pediococcus, Weissella, and Leuconostoc genus could be distinguished, but non-Lactobacillus Genus Complex could not be detected. The groEL gene sequencing and Miseq high-throughput approach were adopted to estimate the richness and diversity of Lactobacillus species in different ecosystems. The method was tested using kurut (fermented yak milk) samples and fecal samples of human, rat, and mouse. The results indicated that Lactobacillus mucosae was the predominant gut Lactobacillus species among Chinese, and L. johnsonii accounted for the majority of lactobacilli in rat and mouse gut. Meanwhile, L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus had the highest relative abundance of Lactobacillus in kurut. Thus, this groEL gene profiling method is expected to promote the application of Lactobacillus for industrial production and therapeutic purpose.

Keywords: Lactobacillus, groEL, phylogenetic analysis, species diversity, MiSeq Illumina sequencing platform

1. Introduction

Lactobacillus genus is a Gram-positive, non-spore-forming, catalase-negative, rhabditiform, facultative anaerobic or microaerophilic group of bacteria [1]. According to the fermentation products, Lactobacillus species can be segmented into homofermentative and heterofermentative lactobacilli. Due to fastidious nutritional requirement, Lactobacillus lives in nutrient-rich environment, such as fermented or spoiled foods, animal feed, plant and soil surfaces, and bodies of invertebrate and vertebrate animals [2]. Lactobacillus species are also indigenous to human digestive, urinary, and genital systems [3]. Although they usually protect human from pathogen invasion, they can be occasional opportunistic pathogens [4]. Some Lactobacillus strains are probiotic and serve as supplements for the prevention and treatment of various gastrointestinal diseases [5]. Thus, assessment of the diversity of Lactobacillus species in different ecological environment is expected to provide valuable reference to promote the application of the bacteria for industrial production and therapeutic purpose.

In taxonomic perspective, Lactobacillus is an extremely diverse genus comprising of 240 species and 29 subspecies (http://www.bacterio.net/lactobacillus.html), greatly exceeding the diversity of a typical bacterial family [6]. However, with the unreliability of biochemical identification methods, the molecular biology methods have been proved to be effective for differentiating Lactobacillus species [7]. For instance, Zheng et al. used the core and pan-genomes of 174 Lactobacillus and Pediococcus strains and separated these strains into 24 phylogenetic groups [8]. A cladogram of 452 genera [9] showed that the Lactobacillus clade includes species from six different genera (Lactobacillus, Pediococcus, Weissella, Leuconostoc, Oenococcus, and Fructobacillus), and it was proposed to name these six genera as constituting the Lactobacillus Genus Complex. 16S rRNA profiling methods have been widely used to assess microbial flora but it is also known that several closely related species cannot be correctly differentiated. A profiling method based on an internal transcribed spacer (ITS) has been proposed to identify Lactobacillus down to species level, but limitations remain because only 62 species had complete Lactobacillus ITS amplicon (LITSA) sequences, among which 18 species had an average LITSA sequence identity of above 97% compared with one other Lactobacillus species [10]. Phylogenetic inference can also be made from several genes or proteins, such as groEL, rplB, rpoB, recA, tuf, aroE, ddl, dnaE, fusA, ftsZ, glnA, gyrB, glpF, gltX, gyrB, gpd, gdh, hemN, ileS, lepA, leuS, ldhL, mutS, mutL, metRS, nrdD, pepV, pgm, polA, recG, recP, xpt, yqil, tkt, and tpi [7,11,12]. Some of these genetic markers have shown the ability to identify Lactobacillus species with the same or even better accuracy and sensitivity than 16S rRNA gene [11]. Among these molecular markers, groEL gene, which translates the synthesis of heat stress proteins was used to identify lactic acid bacteria as early as ten years ago [13,14]. Reportedly, groEL gene can achieve far better resolution than 16S rRNA gene, and topological structure of the phylogenetic tree using this gene is the same as that for the 16S rRNA gene [11]. Meanwhile, groEL gene has a high rate of evolution [15] and is single copy, commonly found in lactobacilli [16], and many lactobacilli gene sequences are available in the chaperonin sequence database (cpnDB). This facilitates the identification and quantitative analyses of this genus. In the meantime, the molecular biological identification methods when combined with the error-proof, high throughput next-generation sequencing technologies may facilitate phylogenetic analysis of microbiota, which had previously been used to analyze the Bifidobacterium genus [15,17].

This study aimed to introduce a novel profiling protocol to assess Lactobacillus species using the distinguishing marker groEL gene and the MiSeq Illumina sequencing platform. A new primer set was also designed and its robustness tested in identifying Lactobacillus species in mammalian fecal and kurut (fermented yak milk) samples.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Culture and Genome Extraction

A list of 35 Lactobacillus strains employed in this research is shown in Table S1 in the Supplementary Materials. The growth conditions of all Lactobacillus strains were based on previous literature report [18]. The following 12 non-Lactobacillus strains were also used: Streptococcus thermophiles ST2017, Escherichia coli BL21, Bacteroides ovatus ATCC8483, Bifidobacterium longum CCFM861, Bi. animalis CCFM624, Bi. breve CCFM684, Bi. adolescentis CCFM626, Leuconostoc mesenteroides NT5-1, Leuconostoc lactis DYNDL 7-2, Pediococcus acidilactici HN17-2, Pediococcus pentosaceus H27-1L, and Weissella cibaria FSDLZ2M11. S. thermophilus was grown in lactic acid medium at 42 °C; E. coli, Ba. ovatus, and all Bifidobacterium strains were cultured according to the literature [15,19,20]. Leuconostoc mesenteroides, Leuconostoc lactis, Pediococcus acidilactici, Pediococcus pentosaceus, and Weissella cibaria were grown in de Man–Rogosa–Sharpe (MRS) medium with 0.05% (wt/vol) L-cysteine hydrochloride in an anaerobic environment at 37 °C. All bacterial strains employed in the research were obtained from the Culture Collection of Food Microorganisms of Jiangnan University (Wuxi, China).

The genomes of all above bacterial strains were extracted and purified as described earlier [21].

2.2. Sample Collection and Genome Extraction

In this study, six human, six rat, and six mouse fecal samples were collected. The methods of collection, transportation, and storage of the stool samples were reported previously [15]. The bacterial genome DNA of these samples were extracted with FastDNA SPIN Kit for Feces (MP Biomedicals, Carlsbad, CA, USA) in accordance with producer’s suggestions.

Traditional fermented yak milk samples were retrieved from the herdsmen’s homes in the pasture region of Qinghai, China. The samples were collected, transported, and stored as reported previously [22]. The genomic DNA from these kurut samples was extracted using FastDNA Spin Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals, Carlsbad, CA, USA) in accordance with producer’s instruction.

All procedures followed in this research were authorized by the Ethical Committee of Jiangnan University (Wuxi, China).

2.3. Selection of Lactobacillus groEL Gene

The sequences of 73 Lactobacillus core genes based on a previous study [9] were retrieved from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) genome database and European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) database. With MEGA7.0 software, the sequences of genome were aligned using ClustalW program, and phylogenetic trees were established using maximum likelihood (ML) method with a supporting bootstrap value of 1000. The resulting gene sequences were filtered based on the results in the literature [15,23]. Accordingly, groEL gene was chosen as the marker gene for sequencing analysis of the Lactobacillus strains.

2.4. Phylogenetic Analysis

Phylogenetic trees on the basis of groEL gene and the V3–V4 region of 16S rRNA gene of Lactobacillus strains (Table S4) were constructed using MEGA7.0 software [24,25]. The ClustalW program was used for sequence alignment [26], and maximum likelihood (ML) method was used to yield phylogenetic trees with bootstrap support value of 1000.

2.5. Lactobacillus groEL-Specific Primer Design

The available groEL gene sequences of 108 species of Lactobacillus (Table S2) were downloaded from the NCBI and EMBL databases, and sequences alignment was conducted using the ClustalW program [26]. The results of the analysis were then used to guide the designing of primers using the PRIMER [27] and OLIGO [28] software. The sequences of designed degenerate primers were as follows: forward primer Lac_groEL_F, 5′-GCYGGTGCWAACCCNGTTGG-3′ and reverse primer Lac_groEL_R, 5′-AANGTNCCVCGVATCTTGTT-3′. The WebLogo pictures of primers were made using the website (http://weblogo.berkeley.edu/) [10].

Shanghai Shengong Biological Engineering Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) was responsible for the synthesis of the designed primers.

2.6. Evaluation of the Accuracy and Specificity of the Degenerate Primers

A mock Lactobacillus community was prepared using nine Lactobacillus strains (Table S3) that were cultured separately on MRS medium in an anaerobic atmosphere until they reached the late log phase. The DNA extraction methods of these strains were consistent with those reported in previous literature [15] and mixed in a ratio of 0.01 ng to 50 ng. The colony-forming units (cfu) of the Lactobacillus strains were calculated based on the groEL gene copy numbers by the means of a calculator provided by the URI Genomics & Sequencing Center (http://cels.uri.edu/gsc/cndna.html). Subsequently, PRIMER-BLAST was applied to perform specific testing by in silico PCR amplification, and NCBI non-redundant (nr) database was used as a reference database [29]. Three parallel experiments were carried out.

2.7. PCR Conditions, Quantifiable and Sequencing Measures

The extracted DNA of 35 Lactobacillus strains and 12 non-Lactobacillus strains described above were used for PCR amplification. The PCR conditions used in groEL profiling were as followed: 5 min at 95 °C, followed by 35 cycles of 30 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 58 °C, 60 s at 72 °C, and final elongation at 72 °C for 7 min. Furthermore, the DNA extracted from fecal and kurut samples were used for amplification of partial groEL gene using the primers Lac_groEL_F/Lac_groEL_R, as well as the V3–V4 region within 16S rRNA gene and primer pair 341F/806R was used on the basis of previously reported protocol [30]. Further purification and quantification of all PCR amplified products were conducted according to reported protocols [15]. The purified DNA was sequenced by 2 × 300-bp paired-end Illumina sequencing. The DNA amplicons library was made with TruSeq DNA LT Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) and sequenced by MiSeq Illumina platform with the MiSeq v3 Reagent Kit (600 cycles) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

2.8. Cross-Alignment Analysis

All available universal target (UT) sequences of groEL gene of Lactobacillus were retrieved from the chaperonin database, which contains 533 strains correspond to 129 Lactobacillus species (Table S5). With MatGAT software, cross-alignment of all sequences was conducted.

3. Results

3.1. Selection of the Lactobacillus groEL Gene

The sequences of 73 core genes based on previous studies were retrieved for the selection of marker gene for Lactobacillus genus. The results showed the following distinct types of core genes: first, core genes without highly variable region sequences and low resolution that could not be used to distinguish between Lactobacillus species; second, core genes with highly variable regions and high resolution that could distinguish between different Lactobacillus species but their ends did not contain relatively conserved sequences, which restrict the designing of primers; third, core genes with highly variable regions, high resolution to distinguish between Lactobacillus species, and relatively conserved sequences at their ends, e.g., the groEL gene, thus suitable for designing primers. Therefore, the groEL and 16S rRNA gene sequences of all Lactobacillus species that deposited in the EMBL and NCBI databases were downloaded and pairwise sequence similarity using BLAST were performed. The results revealed that the lowest and average pairwise similarity values of the groEL gene were 69.63% (L. iners and L. ingluviei) and 79.61%, respectively, whereas those of the 16S rRNA gene were 83.77% (L. thailandensis and L. iners) and 89.58% respectively. These indicate that the groEL gene evolves at a high rate that allows identification of Lactobacillus species more accurately when comparing to 16S rRNA. What’s more, discrimination of the 129 species of Lactobacillus was achieved based on the cross-alignment of groEL sequences (Table S5). As a result, the groEL gene was selected as the core gene for identification of Lactobacillus species.

3.2. Phylogenetic Analysis of the Lactobacillus groEL Gene

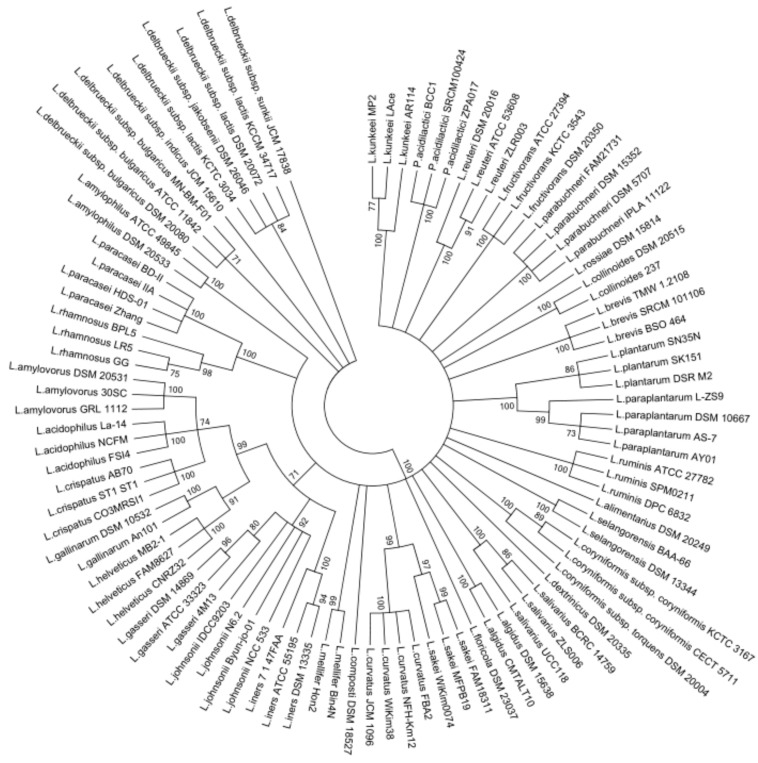

The members of Lactobacillus genus were previously separated into 24 phylogenetic groups including Pediococcus genus based on the concatenated protein sequences of single-copy core genes. In view of this, a phylogenetic tree was constructed based on the groEL gene sequences containing 97 Lactobacillus strains and Pediococcus strains of 22 phylogenetic groups, using the Maximum Likelihood method with 1000 bootstrap values (Figure 1). According to the phylogenetic tree, Lactobacillus amylovorus, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus cripatus, Lactobacillus gallinarum, Lactobacillus helveticus, Lactobacillus gasseri, Lactobacillus johnsonii, and Lactobacillus iners were gathered into a large cluster, whereas Lactobacillus delbrueckii subspecies were individually assembled into a cluster. Meanwhile, Lactobacillus ruminis was separated from the Lactobacillus salivarius group when the phylogenetic tree was built on the basis of groEL gene. On the other hand, the closely related Lactobacillus species and subspecies formed clusters, and distinct Lactobacillus species formed different clusters. The Pediococcus species were gathered into an individual branch on the phylogenetic tree. However, the phylogenetic dendrogram using the 16S rRNA gene indicated some distinct Lactobacillus species were grouped into the same clusters, such as Lactobacillus iners and Lactobacillus amylophilus, Lactobacillus brevis and Lactobacillus amylophilus (Figure S1). These results suggest that groEL gene could better differentiate between the Lactobacillus species when compared to 16S rRNA gene.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree of Lactobacillus on the basis of groEL gene sequences by maximum likelihood (ML) analysis method. Bootstrapping with 1000 replicates, and bootstrap values over 70% were shown on the branches.

3.3. Design of Novel Primer Sets for Identifying Lactobacillus

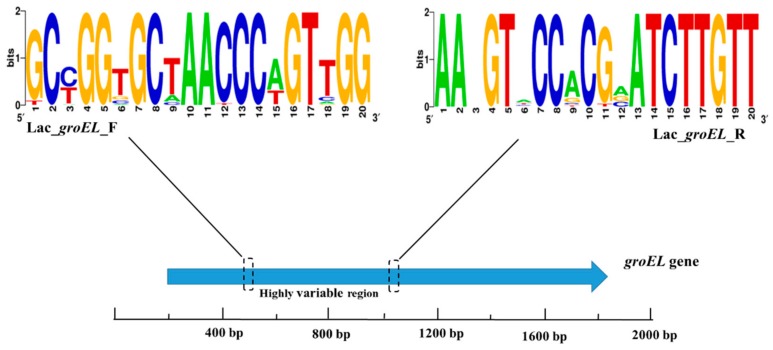

The NCBI database and the chaperonin sequence database contain enough groEL gene sequences of Lactobacillus strains to meet the requirements of sequence alignment and new species identification. The emergence of next-generation sequencing technology facilitates amplification and sequencing of partial gene sequences of bacterium. The full-length groEL gene is approximately 1600 bp long, which is not suitable for short-read sequencing platform. Therefore, partial Lactobacillus groEL gene was used for sequencing and designing a novel primer set (Lac_groEL_F and Lac_groEL_R) as per the primer design criteria using the MiSeq Illumina sequencing platform. Based on the results of multiple sequence alignment, the 340–824 bp region of the groEL gene was targeted for PCR amplification. After the procedure of PCR, the amplicon was about 480 bp which could be sequenced by 2 × 300-bp paired-end Illumina sequencing. Figure 2 shows the sequence conservation of the groEL gene as represented by WebLogo images.

Figure 2.

A WebLogo representation was generated to demonstrate the primer sequence conservation. The higher the total stack height, the better the sequence conservativeness of the location. Different symbols at the same location indicate different relative frequencies of the nucleic acid.

3.4. Development of Biological Information Analysis Tool for Lactobacillus

All of the available complete sequences of the Lactobacillus groEL gene were downloaded from the NCBI, EMBL, and chaperonin sequence database and summarized in an annotation library (Lac_groEL_database). This database is constantly updated with newly obtained sequences of the Lactobacillus groEL gene.

Disassembly data were analyzed with the QIIME1.9.1 software. Briefly, disassembly sequences were first screened to select sequences with quality Q value higher than 30, and high-quality sequences were spliced with Flash software package. The splicing condition was overlap base number of >10 bp, and no mismatch base was found. The barcode and primer sequences were then removed to obtain the final effective sequence. Notably, sequence similarity of 97% could be clustered into one operational taxonomic unit (OTU). OTUs based on the gene composition of Lactobacillus groEL were comparable with those in Lac_groEL_database.

3.5. Performance Evaluation of the Degenerate Primers for Identifying Lactobacillus Species

In silico PCR was performed using PRIMER-BLAST for evaluating the specificity of the novel primer set. The result showed that only one amplicon was generated from the Lactobacillus genomes, indicating that the primer set had good specificity for Lactobacillus. Further, an in vitro experiment was carried out by using the primers Lac_groEL_F/Lac_groEL_R for amplifying DNA obtained from 35 Lactobacillus and 12 non-Lactobacillus species. The results showed that PCR product could be obtained using the template DNA extracted from Lactobacillus, Pediococcus, Weissella, and Leuconostoc species (Figure S2), indicating that the newly designed primer set could distinguish Lactobacillus and genera historically associated with or grouped within the lactobacilli. Other bacteria cannot be amplified by corresponding gene segments in the research.

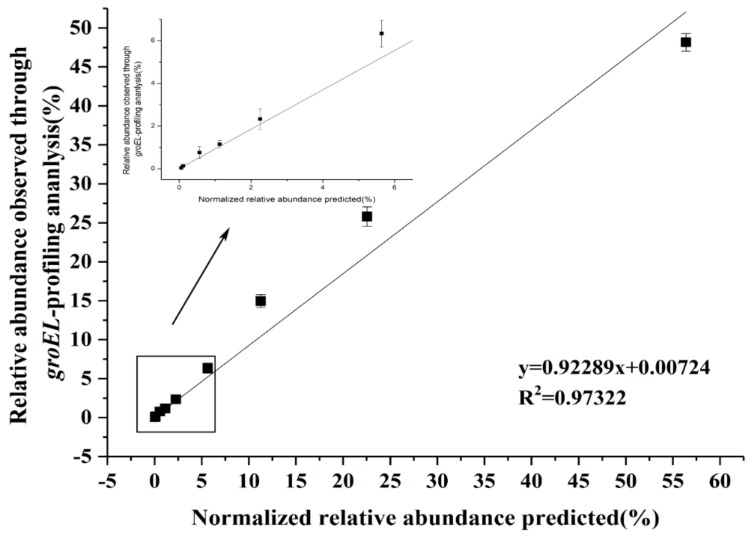

In addition, the ability to distinguish Lactobacillus accurately and sensitively by the new degenerate primers were evaluated. Briefly, the DNA of different Lactobacillus species were mixed in known quantities. After PCR amplification with new primers for this artificial Lactobacillus community, the amplicons were sequenced using MiSeq Illumina sequencing platform. The findings indicated that the predicted relative concentration of Lactobacillus had a good correlation with the relative concentration measured using the degenerate primer pair Lac_groEL_F/Lac_groEL_R, proving the accuracy of the new primers (Figure 3). The lowest amount of Lactobacillus DNA, by the means of MiSeq Illumina sequencing platform, was 0.05 ng corresponding with a concentration of 104 cfu/mL. Hence, the detection limit of the newly constructed primers was considered 104 cfu/mL.

Figure 3.

Accuracy and sensitivity of the new primer pair. The relative abundance of the predicted artificial Lactobacillus community was normalized, which was well consistent with the results of the analysis method based on the new primers. The linear regression equation is y = 0.92289x + 0.00724, and the y value represents the relative abundance observed through groEL-profiling analysis. The correlation index R2 = 0.97322.

3.6. Resolution of Partial groEL Gene of Lactobacillus by Analyzing Samples from Varied Habitats

To evaluate the overall performance and resolution of the Lactobacillus new primers in different ecosystems, the Lactobacillus diversity of 24 samples, including six human fecal samples, six rat fecal samples, six mouse fecal samples, and six fermented yak milk samples was analyzed. Moreover, the V3–V4 region of 16S rRNA amplicons of these samples were sequenced. The 16S rRNA gene method assigned approximately 0.05–25% of the reads from the stool samples to the Lactobacillus genus, and the Lactobacillus species composition was not clear due to the limited resolution of the universal primer set 341F/806R. In contrast, using the groEL gene-based method, nearly all of the amplified sequences clustered as Lactobacillus and classified down to species level. Table 1 shows the microflora composition of four different habitats on the basis of 16S rRNA profiling method. Table 2 shows the species composition of the habitats on the basis of groEL gene profiling method. The values represent the average of the relative abundance of the microbes of six samples, and the value in parentheses is the standard error of the sample. The relative abundance values of genera and species less than 0.01 are omitted.

Table 1.

16S rRNA profiling method of the microflora composition of four different habitats 1.

| Samples | Human | Rat | Mice | Kurut | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | |||||

| Enterobacteriaceae | 0.28(0.12) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | |

| Streptococcus | 0.11(0.09) | 0(0) | 0.02(0.02) | 0.15(0.03) | |

| Bacteroides | 0.1(0.05) | 0.03(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | |

| Bifidobacterium | 0.09(0.03) | 0(0) | 0.07(0.05) | 0(0) | |

| other genera <1% | 0.09(0.02) | 0.07(0) | 0.05(0.01) | 0.01(0) | |

| Blautia | 0.06(0.03) | 0.01(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | |

| Ruminococcaceae | 0.05(0.02) | 0.06(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | |

| Clostridiales | 0.04(0.03) | 0.16(0.01) | 0.12(0.03) | 0(0) | |

| Lachnospiraceae | 0.04(0.01) | 0.03(0.01) | 0.04(0.02) | 0(0) | |

| Clostridiaceae | 0.03(0.01) | 0.01(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | |

| Collinsella | 0.02(0.01) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | |

| Enterococcus | 0.02(0.01) | 0(0) | 0.01(0) | 0(0) | |

| Erysipelotrichaceae | 0.01(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | |

| Eubacterium | 0.01(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | |

| Lactobacillus | 0.01(0) | 0.13(0.02) | 0.14(0.02) | 0.82(0.03) | |

| Mitsuokella | 0.01(0.01) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | |

| Parabacteroides | 0.01(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | |

| Prevotella | 0.01(0.01) | 0.08(0.01) | 0(0) | 0(0) | |

| Ruminococcus | 0.01(0) | 0.03(0) | 0.05(0.01) | 0(0) | |

| Adlercreutzia | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0.03(0.01) | 0(0) | |

| Aerococcaceae | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0.01(0) | 0(0) | |

| Aerococcus | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0.06(0.04) | 0(0) | |

| Pseudomonas | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0.01(0) | |

| Bacteroidales | 0(0) | 0.17(0.01) | 0.13(0.06) | 0(0) | |

| Coprococcus | 0(0) | 0.01(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | |

| Desulfovibrionaceae | 0(0) | 0.01(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | |

| Helicobacteraceae | 0(0) | 0.01(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | |

| Planococcaceae | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0.03(0.01) | 0(0) | |

| Pseudomonas | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0.01(0) | 0(0) | |

| Oscillospira | 0(0) | 0.04(0) | 0.01(0) | 0(0) | |

| Peptostreptococcaceae | 0(0) | 0.05(0.01) | 0(0) | 0(0) | |

| Staphylococcus | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0.21(0.07) | 0(0) | |

| Rikenellaceae | 0(0) | 0.04(0.01) | 0(0) | 0(0) | |

| Turicibacter | 0(0) | 0.02(0) | 0.01(0) | 0(0) | |

| unassigned genera | 0(0) | 0.04(0.01) | 0.01(0) | 0(0) | |

1 The values represent the average of the relative abundance of the microbes of six samples, and the value in parentheses is the standard error of the sample. The relative abundance values of genera and species less than 0.01 are omitted.

Table 2.

groEL gene profiling method of the species composition of four different habitats 1.

| Samples | Human | Rat | Mice | Kurut | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | |||||

| L. mucosae | 0.67(0.04) | 0(0) | 0.01(0.01) | 0(0) | |

| L. gasseri | 0.06(0.02) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | |

| L. salivarius | 0.06(0.01) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | |

| other Lactobacillus <1% | 0.06(0.01) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | |

| L. oris | 0.05(0.03) | 0.01(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | |

| L. rhamnosus | 0.03(0.01) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | |

| L. amylovorus | 0.02(0.01) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | |

| L. casei | 0.01(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | |

| L. crispatus | 0.01(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | |

| L. plantarum | 0.01(0.01) | 0.01(0) | 0.01(0) | 0(0) | |

| L. vaginalis | 0.01(0.01) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | |

| L. acidophilus | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0.1(0.03) | 0(0) | |

| L. fermentum | 0(0) | 0.05(0.05) | 0(0) | 0(0) | |

| L. reuteri | 0(0) | 0.1(0.04) | 0.11(0.02) | 0(0) | |

| unassigned Lactobacillus | 0(0) | 0.07(0.02) | 0.1(0.02) | 0(0) | |

| L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0.97(0.03) | |

| L. helveticus | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0.03(0.03) | |

| L. intestinalis | 0(0) | 0.33(0.1) | 0.01(0) | 0(0) | |

| L. johnsonii | 0(0) | 0.4(0.11) | 0.65(0.04) | 0(0) | |

| L. sp. L6 | 0(0) | 0.01(0) | 0.01(0) | 0(0) | |

| L. animalis | 0(0) | 0.01(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | |

| unassigned species | 0(0) | 0.01(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | |

1 The values represent the average of the relative abundance of the microbes of six samples, and the value in parentheses is the standard error of the sample. The relative abundance values of genera and species less than 0.01 are omitted.

Further, using the groEL gene profiling, L. mucosae accounting for about 60% lactobacilli was found to be the most abundant Lactobacillus in people’s intestinal tract, followed by L. gasseri and L. salivarius (Table 2). In contrast, partial 16S rRNA gene profiling revealed that the Lactobacillus genus accounted for less than 3% of the human intestinal flora, the average is 1% (Table 1).

Analysis of genome DNA from six rat and six mouse fecal samples based on novel primer set Lac_groEL_F/Lac_groEL_R suggested the usefulness of this method for accurate cataloging of Lactobacillus species. In particular, L. johnsonii and L. intestinalis showed the highest relative abundance among the Lactobacillus population in the rat gut (Table 2), whereas L. johnsonii and L. reuteri were shown to be the main Lactobacillus in mouse gut (Table 2). Interestingly, 16S rRNA gene profiling method showed that the Lactobacillus genus accounted for more than 10% of the microbes in the rat and mouse intestines (Table 1).

In addition to using the method developed in this paper for studying the composition of lactobacilli in complex ecosystems, the formation of Lactobacillus species was also investigated in a relatively simple system. Tibetan people in Qinghai, China, prepare kurut using traditional methods. Six kurut samples were profiled using Lac_groEL_F/Lac_groEL_R, and the results showed that L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus was the most abundant Lactobacillus species. Meanwhile, 16S rRNA gene profiling revealed that more than 82% of the microbes in kurut are Lactobacillus, followed by the Streptococcus genus at approximately 15% (Table 1).

Notably, OTU analysis of the results obtained from partial groEL and 16S rRNA gene profiling methods demonstrated 97% identity. Lactobacillus species with a relative abundance of less than 0.01 in each sample were excluded as “other Lactobacillus <1%” in the table, and OTU which could not be clustered as Lactobacillus was shown as “unassigned” when the results were based on groEL gene profiling method. The genera with a relative abundance of <1% in each sample were excluded as “other Genera <1%” in the table, and unassigned genera whose relative abundance were less than approximately 5% includes OTUs that were temporarily not recognized as any other genus when the results were based on 16S rRNA profiling method.

4. Discussion

To design a Lactobacillus-specific primer pair using MiSeq Illumina sequencing platform, several criteria need to be satisfied: first, the target gene must be present across all Lactobacillus species; second, the target gene should be sufficient to distinguish different species; third, the target gene should involve a highly variable region flanked by conserved regions on both sides; fourth, the region targeted for amplification within the target gene should be less than 500 bp long; and fifth, sufficient number of target gene sequences should be available [15,31]. The primer pair designed in this study met these criteria.

The detection limit of Lac_groEL_F/Lac_groEL_R was 104 cfu/mL estimated from the means of MiSeq Illumina sequencing platform. Notably, in one previous study, the detection limit of Lactobacillus ITS profiling was 1.85 × 103 cells/µL [10], but ITS marker has different operon copy number within a genome which may skew the diversity estimates of bacterial communities. Since groEL is a single-copy gene in Lactobacillus species, the estimates obtained in this study could be used as a reference. The assessment of detection specificity using the Lactobacillus groEL profiling method found that Lactobacillus, Pediococcus, Weissella, and Leuconostoc genus could be distinguished, but non-Lactobacillus Genus Complex could not be detected, indicating that the primers Lac_groEL_F/Lac_groEL_R are not specific only for Lactobacillus. It is not clear that Lactobacillus present in the microbial flora of the sample if the results merely based on the PCR amplification and gel imaging. Further confirmation would be needed by sequencing and alignment.

To evaluate the performance of groEL gene profiling method, Lactobacillus species diversity was assessed in different ecosystems. The results showed the composition and abundance of Lactobacillus species in people’s intestinal tract varied between different people. L. mucosae had the highest relative abundance of Lactobacillus in the intestine of Chinese, inconsistent with the previous finding that L. acidophilus and L. helveticus were the two dominant species in the gut of adult humans [32]. This discrepancy between the results could be explained by the finding that gut microbial composition differs between individuals based on internal and external factors such as diet, ethnicity, age, and physiological condition [33,34,35]. Furthermore, L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus showed the highest relative abundance among Lactobacillus species in fermented yak milk samples, consistent with previous results [21]. The evaluation of the species diversity of Lactobacillus under different ecological environments is expected to provide valuable information for promoting the application of Lactobacillus for industrial production and therapeutic purpose.

There have been many classification methods since Lactobacillus was introduced in 1901, and it is likely that no single gene can distinguish between all Lactobacillus species. Thus, similar to most methods, groEL gene profiling is not without drawbacks. Cross-alignment analysis showed that lactobacilli have extremely high phylogenetic diversity (Table S5). Notably, the groEL sequences downloaded from the chaperonin sequence database (cpnDB) includes two strains of Lactobacillus plantarum and Lactobacillus rumis which are misclassified as Lactobacillus salivarius. In fact, Lactobacillus plantarum cannot be identical with Lactobacillus salivarius since these species are so distant on the basis of groEL gene sequence. Table 3 showed that 9 species shared groEL gene sequence identity over 97% with one or more Lactobacillus species. Thus, caution should be exercised when identifying these Lactobacillus species using the groEL gene as a genetic marker. The combination of groEL gene profiling with profiling based on 16S rDNA, rpoB, clpC, or any other gene may be more effective in distinguishing between Lactobacillus species. Moreover, complete genomic information, including that on groEL gene sequences, of some Lactobacillus species is not available. These species would be labeled as “unassigned Lactobacillus” when annotated in database. Thus, the database needs to be updated regularly when new species are discovered to enable the identification of all Lactobacillus species. Furthermore, Pediococcus, Weissella, and Leuconostoc genus produced corresponding fragments when using the degenerate primers for PCR amplification, indicating that the primers may be effective when assessing genera that are closely related to Lactobacillus genus.

Table 3.

Lactobacillus species with groEL sequence identity of over 97% with another Lactobacillus species.

| Species | groEL identity % with the Closet Species 2 | Closest Species |

|---|---|---|

| L. acidophilus | 100 | L. amylovorus |

| L. acidophilus | 99.8 | L. kitasatonis |

| L. amylolyticus | 99.6 | L. helveticus |

| L. buchneri | 99.8 | L. hilgardii |

| L. farciminis | 98.4 | L. formosensis |

| L. gasseri | 100 | L. paragasseri |

| L. johnsonii | 98.9 | L. taiwanensis |

| L. plantarum | 100 | L. pentosus |

| L. sakei | 99.3 | L. curvatus |

| L. zeae | 100 | L. paracasei |

2 The percentage shown in the table corresponds to the highest identity observed among groEL universal target sequences identified in strains of the two species compared.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, a newly designed primer pair based on groEL gene could distinguish Lactobacillus species from other non-Lactobacillus Genus Complex bacterial species, with a detection limit of 104 cfu/mL. The results of characterization of the Lactobacillus population in different ecosystems, such as human, rat, and mouse gut and traditional fermented yak milk, demonstrated the efficacy of this new groEL gene-based profiling method, indicating its applicability for academic research and industrial purposes.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by Collaborative innovation center of food safety and quality control in Jiangsu Province.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4425/10/7/530/s1, Figure S1: A phylogenetic tree using Maximum Likelihood method on the basis of v3v4 region of 16S rRNA gene sequences for lactobacilli, Figure S2: Specificity of the newly designed primer pair in amplifying the selected partial groEL gene. Table S1: Lactobacillus strains used for primer specificity test, Table S2: 108 species of Lactobacillus used for primers design, Table S3: List of strains used for creation of the artificial sample, Table S4: List of Lactobacillus strains used in phylogenetic trees based on the v3v4 region of 16S rRNA and groEL gene, Table S5: MatGAT cross-alignment of groEL sequences of Lactobacillus.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.X., M.P., and W.L.; methodology, M.X. and M.P.; software, M.X., M.P., and Y.J.; formal analysis, M.X., M.P., and Y.J.; investigation, M.X., M.P., and Y.J.; resources, X.L., W.L., and W.C.; data curation, M.X. and M.P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.X.; writing—review and editing, X.L., W.L., H.Z., and W.C.; visualization, M.X., M.P., and Y.J.; supervision, W.L., J.Z., H.Z., and W.C.; project administration, W.L., H.Z. and W.C.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31820103010, 31771953, 31871774), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (JUSRP51903B), the National first class discipline program of Food Science and Technology (JUFSTR20180102).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Makarova K., Slesarev A., Wolf Y., Sorokin A., Mirkin B., Koonin E., Pavlov A., Pavlov N., Karamychev V., Polouchine N., et al. Comparative genomics of the lactic acid bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:15611–15616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607117103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duar R.M., Lin X.B., Zheng J., Martino M.E., Grenier T., Perez-Munoz M.E., Leulier F., Ganzle M., Walter J. Lifestyles in transition: Evolution and natural history of the genus Lactobacillus. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2017;41:S27–S48. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fux030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walter J. Ecological role of lactobacilli in the gastrointestinal tract: Implications for fundamental and biomedical research. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008;74:4985–4996. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00753-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldstein E.J., Tyrrell K.L., Citron D.M. Lactobacillus species: Taxonomic complexity and controversial susceptibilities. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2015;60:S98–S107. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foster L.M., Tompkins T.A., Dahl W.J. A comprehensive post-market review of studies on a probiotic product containing Lactobacillus helveticus R0052 and Lactobacillus rhamnosus R0011. Benef. Microbes. 2011;2:319–334. doi: 10.3920/BM2011.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salvetti E., Harris H.M.B., Felis G., O’Toole P.W. Comparative genomics reveals robust phylogroups in the genus Lactobacillus as the basis for reclassification. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018 doi: 10.1128/AEM.00993-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bao Q., Song Y., Xu H., Yu J., Zhang W., Menghe B., Zhang H., Sun Z. Multilocus sequence typing of Lactobacillus casei isolates from naturally fermented foods in China and Mongolia. J. Dairy Sci. 2016;99:5202–5213. doi: 10.3168/jds.2016-10857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng J., Ruan L., Sun M., Ganzle M. A Genomic View of Lactobacilli and Pediococci Demonstrates that Phylogeny Matches Ecology and Physiology. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015;81:7233–7243. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02116-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun Z., Harris H.M., McCann A., Guo C., Argimon S., Zhang W., Yang X., Jeffery I.B., Cooney J.C., Kagawa T.F., et al. Expanding the biotechnology potential of lactobacilli through comparative genomics of 213 strains and associated genera. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8322. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milani C., Duranti S., Mangifesta M., Lugli G.A., Turroni F., Mancabelli L., Viappiani A., Anzalone R., Alessandri G., Ossiprandi M.C., et al. Phylotype-Level Profiling of Lactobacilli in Highly Complex Environments by Means of an Internal Transcribed Spacer-Based Metagenomic Approach. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018;84:e00706–e00718. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00706-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shevtsov A., Kushugulova A., Tynybayeva I.K., Kozhakhmetov S., Abzhalelov A.B., Momynaliev K.T., Stoyanova L.G. Identification of phenotypically and genotypically related Lactobacillus strains based on nucleotide sequence analysis of the groEL, rpoB, rplB, and 16S rRNA genes. Microbiology. 2011;80:672–681. doi: 10.1134/S0026261711050134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Viale A.M., Arakaki A.K., Soncini F.C., Ferreyra R.G. Evolutionary relationships among eubacterial groups as inferred from GroEL (chaperonin) sequence comparisons. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1994;44:527–533. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-3-527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bergonzelli G.E., Granato D., Pridmore R.D., Marvin-Guy L.F., Donnicola D., Corthesy-Theulaz I.E. GroEL of Lactobacillus johnsonii La1 (NCC 533) is cell surface associated: Potential role in interactions with the host and the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Infect. Immun. 2006;74:425–434. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.1.425-434.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blaiotta G., Fusco V., Ercolini D., Aponte M., Pepe O., Villani F. Lactobacillus strain diversity based on partial hsp60 gene sequences and design of PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism assays for species identification and differentiation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008;74:208–215. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01711-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu L., Lu W., Wang L., Pan M., Zhang H., Zhao J., Chen W. Assessment of Bifidobacterium Species Using groEL Gene on the Basis of Illumina MiSeq High-Throughput Sequencing. Genes. 2017;8:336. doi: 10.3390/genes8110336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dobson C.M., Chaban B., Deneer H., Ziola B. Lactobacillus casei, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, and Lactobacillus zeae isolates identified by sequence signature and immunoblot phenotype. Can. J. Microbiol. 2004;50:482–488. doi: 10.1139/w04-044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caporaso J.G., Lauber C.L., Walters W.A., Berg-Lyons D., Huntley J., Fierer N., Owens S.M., Betley J., Fraser L., Bauer M., et al. Ultra-high-throughput microbial community analysis on the Illumina HiSeq and MiSeq platforms. ISME J. 2012;6:1621–1624. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shi Y., Kellingray L., Le Gall G., Zhao J., Zhang H., Narbad A., Zhai Q., Chen W. The divergent restoration effects of Lactobacillus strains in antibiotic-induced dysbiosis. J. Funct. Foods. 2018;51:142–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2018.10.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Castro V.S., Teixeira L.A.C., Rodrigues D.D.P., Dos Santos L.F., Conte-Junior C.A., Figueiredo E.E.S. Occurrence and antimicrobial resistance of E. coli non-O157 isolated from beef in Mato Grosso, Brazil. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2019;51:1117–1123. doi: 10.1007/s11250-018-01792-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tan H., Zhao J., Zhang H., Zhai Q., Chen W. Novel strains of Bacteroides fragilis and Bacteroides ovatus alleviate the LPS-induced inflammation in mice. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019;103:2353–2365. doi: 10.1007/s00253-019-09617-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun Z., Liu W., Gao W., Yang M., Zhang J., Wu L., Wang J., Menghe B., Sun T., Zhang H. Identification and characterization of the dominant lactic acid bacteria from kurut: The naturally fermented yak milk in Qinghai, China. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 2010;56:1–10. doi: 10.2323/jgam.56.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang H., Xu J., Wang J., Menghebilige, Sun T., Li H., Guo M. A survey on chemical and microbiological composition of kurut, naturally fermented yak milk from Qinghai in China. Food Control. 2008;19:578–586. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2007.06.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferrario C., Milani C., Mancabelli L., Lugli G.A., Turroni F., Duranti S., Mangifesta M., Viappiani A., Sinderen D., Ventura M. A genome-based identification approach for members of the genus Bifidobacterium. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2015;91:fiv009. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiv009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar S., Nei M., Dudley J., Tamura K. MEGA: A biologist-centric software for evolutionary analysis of DNA and protein sequences. Brief. Bioinform. 2008;9:299–306. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbn017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar S., Stecher G., Tamura K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chenna R., Sugawara H., Koike T., Lopez R., Gibson T.J., Higgins D.G., Thompson J.D. Multiple sequence alignment with the Clustal series of programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3497–3500. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Untergasser A., Cutcutache I., Koressaar T., Ye J., Faircloth B.C., Remm M., Rozen S.G. Primer3—new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:e115. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wojciech R. OLIGO 7 Primer Analysis Software. Methods Mol. Biol. 2007;402:35–59. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-528-2_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ye J., Coulouris G., Zaretskaya I., Cutcutache I., Rozen S., Madden T.L. Primer-BLAST: A tool to design target-specific primers for polymerase chain reaction. BMC Bioinform. 2012;13:134. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jia H.R., Geng L.L., Li Y.H., Wang Q., Diao Q.Y., Zhou T., Dai P.L. The effects of Bt Cry1Ie toxin on bacterial diversity in the midgut of Apis mellifera ligustica (Hymenoptera: Apidae) Sci. Rep. 2016;6:24664. doi: 10.1038/srep24664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dieffenbach C.W., Lowe T.M., Dveksler G.S. General concepts for PCR primer design. PCR Methods Appl. 1993;3:S30–S37. doi: 10.1101/gr.3.3.S30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stsepetova J., Sepp E., Kolk H., Loivukene K., Songisepp E., Mikelsaar M. Diversity and metabolic impact of intestinal Lactobacillus species in healthy adults and the elderly. Br. J. Nutr. 2011;105:1235–1244. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510004770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Filippo C., Cavalieri D., Di Paola M., Ramazzotti M., Poullet J.B., Massart S., Collini S., Pieraccini G., Lionetti P. Impact of diet in shaping gut microbiota revealed by a comparative study in children from Europe and rural Africa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:14691–14696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005963107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Armougom F., Henry M., Vialettes B., Raccah D., Raoult D. Monitoring bacterial community of human gut microbiota reveals an increase in Lactobacillus in obese patients and Methanogens in anorexic patients. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7125. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zmora N., Suez J., Elinav E. You are what you eat: Diet, health and the gut microbiota. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018;16:35–56. doi: 10.1038/s41575-018-0061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.