Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Planning for mass critical care (MCC) in resource-poor or constrained settings has been largely ignored, despite their large populations that are prone to suffer disproportionately from natural disasters. Addressing MCC in these settings has the potential to help vast numbers of people and also to inform planning for better-resourced areas.

METHODS:

The Resource-Poor Settings panel developed five key question domains; defining the term resource poor and using the traditional phases of disaster (mitigation/preparedness/response/recovery), literature searches were conducted to identify evidence on which to answer the key questions in these areas. Given a lack of data upon which to develop evidence-based recommendations, expert-opinion suggestions were developed, and consensus was achieved using a modified Delphi process.

RESULTS:

The five key questions were then separated as follows: definition, infrastructure and capacity building, resources, response, and reconstitution/recovery of host nation critical care capabilities and research. Addressing these questions led the panel to offer 33 suggestions. Because of the large number of suggestions, the results have been separated into two sections: part 1, Infrastructure/Capacity in this article, and part 2, Response/Recovery/Research in the accompanying article.

CONCLUSIONS:

Lack of, or presence of, rudimentary ICU resources and limited capacity to enhance services further challenge resource-poor and constrained settings. Hence, capacity building entails preventative strategies and strengthening of primary health services. Assistance from other countries and organizations is needed to mount a surge response. Moreover, planning should include when to disengage and how the host nation can provide capacity beyond the mass casualty care event.

Summary of Suggestions

Definition

1. We suggest the term “resource poor or constrained setting” defines a locale where the capability to provide care for life-threatening illness is limited to basic critical care resources, including oxygen and trained staff. It may be stratified by categories: No resources, limited resources, and limited resources with possible referral to higher care capability.

2. We suggest “critical care in a resource poor or constrained setting” be defined by the provision of care for life threatening illness without regard to the location, including the pre-hospital, emergency, hospital wards, and intensive care setting.

Infrastructure and Capacity Building

3. We suggest in order to provide quality critical care, at any capability level, resource limited countries or health-care bodies should strengthen their primary care, basic emergency care, and public health systems.

4. We suggest capacity building in public health include education for families, community health-care workers, and clinicians in addition to infrastructure support such as transportation and communication systems.

5. We suggest developing countries strive to build capacity by leveraging critical care expertise and resources that exist in such disciplines as surgery, obstetrics, internal medicine, and pediatrics.

6. In order to support those countries with limited critical care assets, we suggest professional critical care societies in resource-rich, developed countries should advocate broadly to mitigate the intellectual siphoning of critical care providers from resource poor countries.

7. We suggest investment in critical care education and development of processes where limited resources can be applied to those patients most likely to benefit from the interventions.

7a. We suggest such processes explore innovative staffing methods and preventative and supportive care that decreases critical illness.

Building Capacity and Quality in District Hospitals:

8. We suggest performance improvement activities be instituted at district or regional level facilities and information shared such that other ICUs and hospitals can learn from one another.

9. We suggest, where feasible, that surgical capacity of the district or regional hospital build capacity to optimize surgical volumes and maintain skills in order to reduce preventable morbidity and mortality.

Emergency Care and Triage:

10. In order to mitigate the need for critical care, we suggest the development of simple triage tools, protocols, and care guidelines modified to resource limitations that can be used by health workers with limited clinical backgrounds. This education should include the IMCI (Integrated Management of Childhood Illness) and IMAI (Integrated Management of Adolescent and Adult Illness) guidelines for recognition, triage, and treatment of the critically ill in resource limited areas.

Prehospital Care and Transport:

11. We suggest education and training of resuscitation, evacuation, and transport of the critically ill be a priority for providers.

11a. We suggest expanding pre-hospital support in the community through education of medical and non-medical laypersons.

Strategic Planning to Build Capacity:

12. We suggest developing countries or settings that are chronically resource constrained develop a minimal level of critical care to be provided at district or regional hospital facilities.

12a. We suggest critical care advocates involve administrators, financiers, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and other similar stakeholders to provide resources to expand capacity to meet such minimal levels.

13. We suggest focusing limited emergency and critical care resources at facilities where the greatest benefit can be achieved. Although basic resuscitation capabilities must exist at all levels, rather than developing rudimentary critical care at primary health clinics, district or regional hospitals may be the most effective and efficient areas of focus to improve national critical care capabilities.

External Alliances:

14. We suggest local authorities establish formal relationships with coalitions of academic medical centers, professional societies, NGO’s, and governmental organizations prior to an actual event in disaster-prone, resource poor regions.

We suggest these partnerships have the following objectives:

To develop and maintain effective communication with the goal of assessing the need for assistance and planning for training, logistics, and timetable for the delivery of support;

To help implement relief efforts, including schedule rotations for teams in and out of the disaster affected areas; and,

To develop planning and preparation for potential disaster events based on historical experience within each region. Such planning should include resolving issues related to licensure and liability coverage in addition to resource allocation and training.

Current Resource Allocation During Crises:

15. We suggest critical care providers use protocols to combine workable approaches that are also cost effective and efficient.

16. We suggest feasibility plans of a protracted event requiring long-term use of critical care resources be developed, whereby the health-care system will require a coordination between less resource-intense but large numbers of primary care patients in concert with resource-intense but fewer critical care patients.

Laboratory Services:

17. We suggest the establishment and implementation of national laboratory strategic plans and policies that integrate existing laboratory systems to combat major prevalent infectious diseases.

Engagement of Staff:

18. In order to engage a motivated workforce to provide critical care, we suggest several initiatives:

Making data readily available

Using data to inform subsequent interventions that can promote change in resource-poor settings

Acquiring or attempting to garner additional resources with government support including affordable and sustainable technologies

Engaging local leadership to encourage staff and motivate buy-in

World Health Organization Resources:

19. We suggest an international body such as the United Nations or World Health Organization (WHO) develop a Relief Coordination Center to aid the evaluation and coordination of international disaster response with use of prepositioned, stored emergency materials and teams.

20. We suggest the WHO develop a Pocket Book of Acute/Critical Care for Hospitalized Patients to help standardize expectations and medical practice.

Introduction

Planning for mass critical care (MCC) in resource-limited settings has been largely ignored, despite large populations who live in crowded conditions and who are prone to suffer disproportionately from natural disasters. In these settings, crisis standards of care are a daily reality. Thus, addressing MCC in these settings has the potential to benefit large populations and also inform planning in better-resourced areas. All stages of planning should involve clinicians, administrators and the public. Decisions made have grave implications and should always include ethicists in all stages (see “Ethical Considerations” article by Daugherty Biddison et al1 in this consensus statement). Given this background, the Resource-Poor Settings panel of the Task Force for Mass Critical Care defined the setting and outlined suggestions for capacity building and mitigation, preparedness, response, and reconstitution and recovery. This article focuses on defining the setting and preparatory actions prior to a disaster event. Many of the capability building and mitigation suggestions in this article are relevant to policy makers and health administrators, whereas preparedness and response primarily relate to clinicians. However, the suggestions inevitably rely on close working relationships and should be read by both clinicians and policy makers. In addition, an approach that works well in one country may work less well in another, and not all approaches are equally acceptable to all governments or their multiple constituencies. There is no one blueprint for an ideal health-care system, nor are there any magic bullets that will automatically elicit improved performance.2 This is hardly surprising: healthcare systems are complex social systems, and the success of any one approach will depend on the system into which it is intended to fit as well as on its consistency with local values and ideologies. In fact, the need to modify World Health Organization (WHO) protocols and the need to work cooperatively within an integrated model with local authorities, especially when local infrastructure is even partially intact, is highlighted by the recent experience with Typhoon Yolanda in the Philippines.3 Thus, how these suggestions are implemented is best left to the local authorities. The second article, “Resource-Poor Settings: Response, Recovery, and Research,” by Geiling et al4 in this consensus statement examines events following a disaster and future research opportunities.

Materials and Methods

The Resource-Poor Settings panel developed five key question domains, and literature searches were conducted to identify an evidence base on which to answer the key questions (see e-Appendix 1 for search terms and literature results if sufficient evidence found). Searches were limited to 2007 to 2013; English-language and non-English-language papers were included. Given the lack of data upon which to develop evidence-based recommendations, expert-opinion suggestions were developed, with consensus achieved using a modified Delphi process. Full details regarding the methodology are provided elsewhere in this supplement (see “Methodology” article by Ornelas et al5 in this consensus statement).

Results

Definition

1. We suggest the term “resource poor or constrained setting” defines a locale where the capability to provide care for life-threatening illness is limited to basic critical care resources, including oxygen and trained staff. It may be stratified by categories:

No resources, limited resources, and limited resources with possible referral to higher care capability.

2. We suggest “critical care in a resource poor or constrained setting” be defined by the provision of care for life-threatening illness without regard to the location, including the pre-hospital, emergency, hospital wards, and intensive care setting.

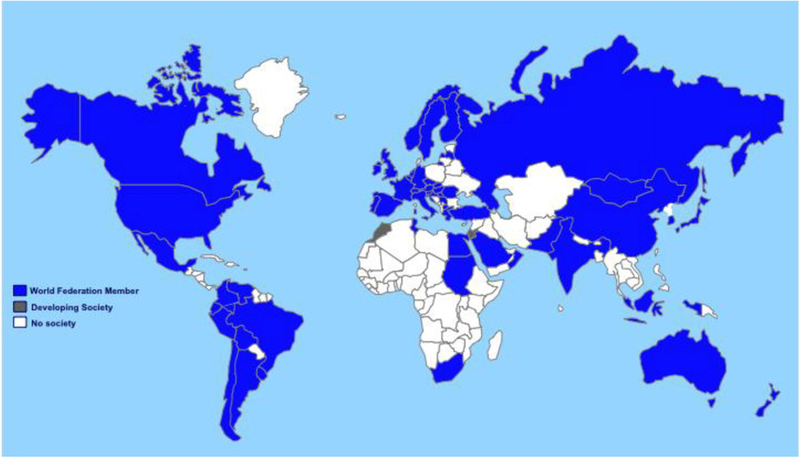

Throughout this article “a developing country” refers to both developing or underdeveloped countries. The peer-reviewed literature on critical care in the developing world is predominantly descriptive in nature. Nevertheless, it supports the view that the current status of services is too often rudimentary, unaffordable, and complex.6–18 The presence or absence of critical care resources indirectly defines the differences between “have and have not” populations in many developing countries (Fig 1).19 Currently, even rapidly emerging economies, such as India, China, and Indonesia, still harbor the largest proportion of the world’s “bottom billion” living in poverty.20 The peer-reviewed literature suggests that in the developing world, many critical care services for the bulk of the population are similar to the services seen in the Western world in the 1950s and 1960s, with limited monitoring and treatment capabilities and high patient-to-nurse staffing ratios. The situation is even worse in resource-poor countries, where progress has been painfully slow and difficult to maintain and has often slipped back or disappeared because of many barriers external to health, such as war, conflict, economic strife, and health-care workforce crises.

Figure 1 -.

Accurate numbers of critical care centers and services worldwide are unknown. Membership in the World Federation of Societies in Intensive and Critical Care Medicine is used as an extrapolation of possible services worldwide, with countries illustrated where membership Societies are fully developed (blue), those where existing membership is developing a professional Society (gray), and countries without Federation members (white). (Adapted with permission from World Federation of Societies of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine.19)

In the developed world, critical care services usually involve “a coordinated system of triage, emergency management and Intensive Care Units (ICUs)” providing contemporary and standards of care to the population.6 Unfortunately, in many developing countries, critical care services are constrained because of limited human and material resources.21 Thus, hospital systems do not prioritize the critically ill, and very few hospitals have ICUs with adequate training and awareness of the principles of critical care.6

In developing countries, an ICU often consists of pressurized air or oxygen but rarely any mechanical ventilation or renal replacement therapy.22 Although ICU services in some university and private hospitals in South Africa, Uganda, Kenya, Rwanda, and Namibia are comparable to Western countries, in township and district hospitals ICU care is often nonexistent. What can be found at the district hospital level is a four- to eight-bed ICU with one or two nurses and nothing else. Fifty percent of the patients will have an empty IV drip and no patient monitors, mechanical ventilators, necessary disposable materials (EEG stickers, tubing, and so forth), or electricity. Oxygen is rare because refilling cylinders or electric oxygen concentrators generally do not exist.22 Lack of ICU services is also found in South and East Asia and the Pacific Islands.23–26

Nevertheless, critically ill patients clearly exist in these countries and may benefit from timely care even in settings without ICUs. Critical care in resource-poor settings is defined, therefore, by the provision of care to the critically ill regardless of location or the availability of intensive care services.

Infrastructure and Capacity Building

3. We suggest in order to provide quality critical care, at any capability level, resource limited countries or health-care bodies should strengthen their primary care, basic emergency care, and public health systems.

4. We suggest capacity building in public health include education for families, community health-care workers, and clinicians in addition to infrastructure support such as transportation and communication systems.

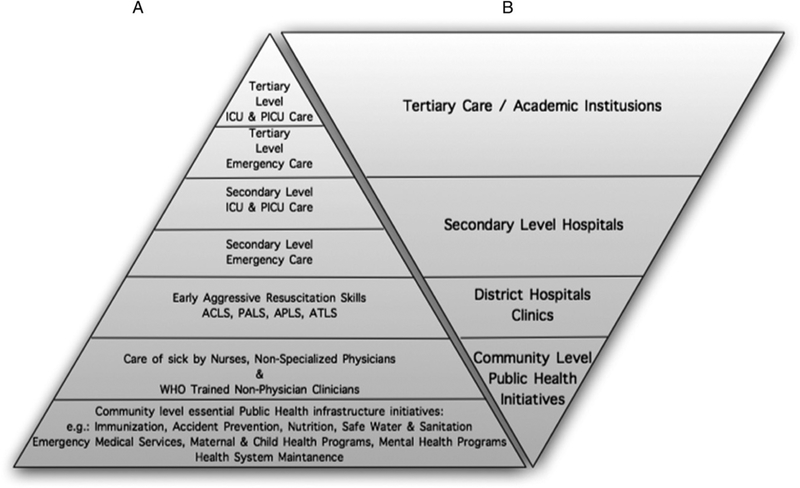

Published recommendations emphasize improving primary care, prevention, and basic emergency care where possible (Fig 2). A study of 30 low-income countries with the highest average daily reduction of mortality of children following the 1978 Declaration of Alma-Ata showed that a committed, prioritized, and phased primary health-care investment was cost effective and led to achieving the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).27 Developing primary health facility-specific preparedness plans also strengthened the preventive response to future disasters.28

Figure 2 -.

A, Progression of care in developed countries leading from established community level public health and emergency services in support of both secondary and tertiary level critical care services. B, The reality of conditions in many resource-poor countries, where basic emergency and protective public health services are lacking or nonexistent. Where critical care services are available, they are limited primarily to urban academic medical centers. ACLS = Advanced Cardiac Life Support; APLS = Advanced Pediatric Life Support; ATLS = Advanced Trauma Life Support; PALS = Pediatric Advanced Life Support; PICU = pediatric ICU; WHO = World Health Organization.

Advances in care should move incrementally without compromising primary care resources.21 Using personnel, materials, and health-system infrastructure creatively can cost-effectively optimize the provision of emergency care in resource-poor settings.29 Researchers and decision-makers should promote the case for universal access to emergency care and research agendas to fill the gaps in knowledge. Obstacles to developing effective emergency medical care include a lack of structural models, inappropriate training foci, and concerns about cost and sustainability in the face of a high demand for services.14,30

5. We suggest developing countries strive to build capacity by leveraging critical care expertise and resources that exist in such disciplines as surgery, obstetrics, internal medicine, and pediatrics.

Severe shortages of primary care providers, specialists, nurses, and prehospital-care providers are present today in about 60 developing countries. Logistic and financial limitations, as well as poorly resourced supporting disciplines (eg, laboratories, radiology, nursing), poor general health status of patients, and delayed presentation of severely sick patients to the ICU also contribute to comparatively high mortality.19 Where critical care is available, the most common reasons for admission are for postsurgical treatment, including trauma, infectious diseases, and peripartum maternal or neonatal complications. These conditions are major contributors to the global burden of disease, and, hence, building critical care capacity around the relevant disciplines (eg, surgery, obstetrics, pediatrics, and internal medicine) will enhance everyday care and lead to a more robust response to pandemics and disasters.

6. In order to support those countries with limited critical care assets, we suggest professional critical care societies in resource-rich, developed countries should advocate broadly to mitigate the intellectual siphoning of critical care providers from resource poor countries.

The intellectual siphoning of critical care providers from resource-poor to resource-rich countries exacerbates the health-care worker crisis in many countries. Critical care professionals in the developed nations also have a duty to avoid damaging the health-care systems of resource-poor countries by advocating against such intellectual siphoning of their health-care professionals.31

7. We suggest investment in critical care education and development of processes where limited resources can be applied to those patients most likely to benefit from the interventions.

7a. We suggest such processes explore innovative staffing methods and preventative and supportive care that decreases critical illness.

Education clearly has a role to play in developing a sufficiently large pool of health-care professionals to meet demand. However, education should be context specific. With little prospect of the return or retention of physicians, the WHO has placed increasing emphasis on task sharing and training of nonspecialist physicians, nurses, and nonphysician clinicians to perform surgery or other skill sets. The issues of what and how to teach are equally important, because the first world mass casualty incident training does not necessarily account for challenges in developing countries.23 Simulation training provides an opportunity to engage learners regardless of language and cultural barriers and has been found especially useful in introducing primary triage and culturally sensitive treatments.32 Simulation training,33 telemedicine,34 and internet courses35 are useful adjuncts for training and evaluating humanitarian health workers, but they have not yet been explored as an educational tool for the indigenous populations.33

Building Capacity and Quality in District Hospitals:

8. We suggest performance improvement activities be instituted at district or regional level facilities and information shared such that other ICUs and hospitals can learn from one another.

Emphasis in developing countries is placed on district hospitals, which serve as the hub of hospital care for surrounding primary care clinics, typically referring more complex, specialty care needs to national or academic centers.36 Unfortunately, the inefficiencies of the district hospitals is considerably high and may negatively affect the government’s initiatives to improve access to quality health-care interventions that are necessary to achieve the health-related MDGs.37 Modeling and learning from best practices are crucial. Inefficient hospitals must learn from their efficient peers to improve the overall performance of the health system.37

9. We suggest, where feasible, that surgical capacity of the district or regional hospital build capacity to optimize surgical volumes and maintain skills in order to reduce preventable morbidity and mortality.

A comprehensive countrywide assessment of surgical capacity in resource-limited settings found severe shortages in available resources. For example, in Rwanda, < 10% of the country can claim adequate surgical services, including trained anesthesia providers, reliable electricity, running water, generators, pulse oximetry, and life-saving surgical airway equipment.38 A recent study of surgical, anesthetic, and obstetric capacities in 78 government district hospitals in seven low-income countries (Bangladesh, Bolivia, Ethiopia, Liberia, Nicaragua, Rwanda, and Uganda) highlighted the lack of trained staff and adequate equipment and suggested that surgery and safe anesthesia must be prioritized within global health.39 Increasing surgical capacity will address unmet surgical needs, and higher volumes will bolster surgical skills and the ability to provide care in disasters. Thus, surgical capacity of the district hospital should be significantly expanded.40

Emergency Care and Triage:

10. In order to mitigate the need for critical care, we suggest the development of simple triage tools, protocols, and care guidelines modified to resource limitations that can be used by health workers with limited clinical backgrounds. This education should include the IMCI (Integrated Management of Childhood Illness) and IMAI (Integrated Management of Adolescent and Adult Illness) guidelines for recognition, triage, and treatment of the critically ill in resource limited areas.

Emergency care, including triage, is often one of the weakest parts of the health system in resource-poor settings, but if well organized it can be life-saving and cost effective. In a wide range of settings, patient populations and systems (eg, inpatient children,11,41 multidisciplinary providers,42 emergency triage assessment and treatment,43 transport training,44,45 poisoning,46 evaluation of urban triage,47 nurses trained in triage,48,49 experience-based realities,50 triage scoring51), simplified protocols, and treatment algorithms have resulted in reduced morbidity and mortality.

Prehospital Care and Transport:

11. We suggest education and training of resuscitation, evacuation, and transport of the critically ill be a priority for providers.

11a. We suggest expanding pre-hospital support in the community through education of medical and non-medical laypersons.

High risk of worsening morbidity and mortality exists during the transport process in settings of personnel and resource limitations. Education and training of appropriate resuscitation, proper evacuation, and safe transport of the critically ill, including obstetrical emergencies from rural birthing centers, are a priority.44,52,53

Strategic Planning to Build Capacity:

12. We suggest developing countries or settings that are chronically resource constrained develop a minimal level of critical care to be provided at district or regional hospital facilities.

12a. We suggest critical care advocates involve administrators, financiers, NGOs, and other similar stakeholders to provide resources to expand capacity to meet such minimal levels.

Emergency and critical care may be improved by defining the minimum standard of care as the level of care that ought to be delivered under conditions of appropriate and efficient referral in a national system. However, the moral argument may be made in some circumstances for an even higher level of care.54 For example, in pandemics, an incremental advancement of emergency and critical care capacity may be realized over time. Strategic planning should focus on personnel, training, equipment support services, ethics, and research.16 These settings also require the iterative introduction of service improvements that leverage human resources through training, focus on sustainable technology, continually analyze cost effectiveness, and share context-specific best practices.54 The strategic planning process must engage senior managers and front-line practitioners and publicize the strategic process throughout the public and the hospital, where formal challenges to the reasoning process are encouraged.55

13. We suggest focusing limited emergency and critical care resources at facilities where the greatest benefit can be achieved. Although basic resuscitation capabilities must exist at all levels, rather than developing rudimentary critical care at primary health clinics, district or regional hospitals may be the most effective and efficient areas of focus to improve national critical care capabilities.

Most district hospitals face challenges in providing complex critical care, and hence those resources typically lie at regional or national hospitals.6,22,36 However, internal country assistance from those regional hospitals can also be valuable, an example of which occurred during the second wave of the 2009 influenza A(H1N1) pandemic in Mexico. There, larger hospitals sent support teams with health personnel and equipment to ill-equipped and inexperienced areas, thereby improving their training to standardize processes and the clinical care of the patients.56

External Alliances:

14. We suggest local authorities establish formal relationships with coalitions of academic medical centers, professional societies, NGO’s, and governmental organizations prior to an actual event in disaster-prone, resource poor regions.

We suggest these partnerships have the following objectives:

To develop and maintain effective communication with the goal of assessing the need for assistance and planning for training, logistics, and timetable for the delivery of support;

To help implement relief efforts, including schedule rotations for teams in and out of the disaster affected areas; and,

To develop planning and preparation for potential disaster events based on historical experience within each region. Such planning should include resolving issues related to licensure and liability coverage in addition to resource allocation and training.

Academic medical centers in the developed world may be able to provide disaster support for an extended time to underserved areas, including countries with austere resources at baseline, with little significant impact on their own operations.57,58 This support can be accomplished by using their own clinical departments and by partnering with similar like-minded institutions. A long on-site presence allows for integration of the responding teams into the local community, permits continuity of care, provides enough time to coordinate replacement teams, and facilitates a transition of responsibility to the local medical community. Humanitarian efforts in unfamiliar territory can result in misappropriation of resources due to poor communication, misunderstanding of resources, and needs.59,60

Resources Necessary to Enhance Capacity

Current Resource Allocation During Crises:

15. We suggest critical care providers use protocols to combine workable approaches that are also cost effective and efficient.

Recent crises, such as the 2009 A(H1N1) influenza pandemic, emphasize the need for bulk antiviral medications, oxygen concentrators, and pulse oximetry monitoring in developing countries. Using pulse oximetry in resource-poor health facilities to target oxygen therapy is likely to save costs, and these devices can be shared between patients by trained technicians. Novel practices, such as the use of ultrasound devices to diagnose degrees of dehydration and other innovations, may take the place of nonexistent laboratory resources.61,62 Protocols such as those in sepsis management combine workable approaches that are also cost effective and efficient.63

16. We suggest feasibility plans of a protracted event requiring long-term use of critical care resources be developed, whereby the health-care system will require a coordination between less resource-intense but large numbers of primary care patients in concert with resource-intense but fewer critical care patients.

Health-care systems need to study the implications of protracted health-care events in which the care of additional, resource-intense critical care patients will have to be delivered in concert with the routine healthcare needs of the general population and other competing hospital operations.64

Laboratory Services:

17. We suggest the establishment and implementation of national laboratory strategic plans and policies that integrate existing laboratory systems to combat major prevalent infectious diseases.

Medical laboratory services play a central role in public health, disease control, surveillance, and patient management but are often neglected in developing countries. Leveraging funding from other sources, such as HIV/AIDS prevention, care, surveillance, and treatment programs, can strengthen medical laboratory services in developing countries.65 Properly functioning laboratory equipment is critical to strengthening health systems.66 Because of inadequate basic infrastructure, such as electricity, clean water, and supplies, laboratory services may be unreliable and may result in delays in treatment and diagnosis.67 Improvements in these services will require coordinated efforts by national governments and partners by implementing national laboratory strategic plans and policies that integrate laboratory services.65

Engagement of Staff:

18. In order to engage a motivated workforce to provide critical care, we suggest several initiatives:

Making data readily available

Using data to inform subsequent interventions that can promote change in resource-poor settings

Acquiring or attempting to garner additional resources with government support including affordable and sustainable technologies

Engaging local leadership to encourage staff and motivate buy-in

Key areas of consideration in building critical care in developing countries settings include personnel and training, equipment and support services, and ethics. Basic care processes, such as monitoring vital signs, administering medications, and laboratory testing, if performed unreliably, may result in treatment delays owing to lack of information needed for clinical decision-making. Lack of information may also hinder advocacy for resources and effective and efficient care. Making data visible and using data to inform subsequent interventions, lobbying for resources, and involving local leadership are essential for success, thereby encouraging staff and motivating their engagement.67 Ethical decision-making and human resource decisions must be based on data68 when possible and always on transparent, articulated policies16 to quantify improvements necessary for meeting MDGs37 and for priority setting for all institutions.55

World Health Organization Resources:

19. We suggest an international body such as the United Nations or WHO develop a Relief Coordination Center to aid the evaluation and coordination of international disaster response with use of prepositioned, stored emergency materials and teams.

In acute crises, appropriate rapid crisis intervention could be achieved by ongoing global disaster surveillance by a Relief Coordination Center served by a panel of experts who would evaluate and coordinate the international disaster response and make use of stored emergency material and emergency teams. Successful disaster response depends on accurate and relevant medical intelligence and socio-geographical mapping in advance of, during, and after the event(s) causing the disaster.69 A first step in preparing for a pandemic in developing countries involves building capacity in public health surveillance and proven community containment and mitigation strategies.17,70 During pandemics, resource-poor settings are more vulnerable for many reasons, but it is universally accepted that surveillance must take priority.71

20. We suggest the WHO develop a Pocket Book of Acute/Critical Care for Hospitalized Patients to help standardize expectations and medical practice.

The WHO has previously developed a field-tested toolkit to guide the care of children.70 We suggest the WHO complement this existing pocket book with a similar Pocket Book of Acute/Critical Care for the Hospitalized Patient. Additional competency-based education and training is available through mechanisms such as the Educational Committee of the World Federation of Societies of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine.8,72 The World Health Assembly Resolution 60.22, “Health Systems: Emergency Care Systems,” serves as a policy tool for improving emergency care and availability globally.73

Areas for Future Research/Interventions/Limitations

In resource-poor areas, advocacy for resources to provide basic emergency and minimum critical care services should be undertaken. Research should be directed to preventative measures, such as social distancing, as well as to implementation and improvement projects on ways to build capacity for mass casualties and pandemics. Efforts should be expended to adjust guidelines to complement the available resources. Partnerships should be formed to participate in joint exercises simulating likely scenarios. Underlying these efforts, efficacy must be measured and validated, with limited resources targeted to those practices that save lives, time, and resources.

Conclusions

Resource-poor settings offer a unique challenge to the provision of MCC to vulnerable victims. However, by better defining those at risk, we can begin to explore mechanisms to not only respond but also build greater capacity and resilience, and then, following the event, rebuild or even expand health-care capabilities. The suggestions proposed in this document are not a defined set of proposals meant to serve as a gold standard. Rather, they serve as a starting point to help those at risk and those responding to help in such resource-constrained settings and situations. Only through the pursuit of active research, training, and effective measurement of outcomes can these suggestions be improved to better care for disaster and pandemic victims in resource-poor settings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Endorsements: This consensus statement is endorsed by the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses, American Association for Respiratory Care, American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma, International Society of Nephrology, Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, Society of Critical Care Medicine, Society of Hospital Medicine, World Federation of Pediatric Intensive and Critical Care Societies, World Federation of Societies of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST the following conflicts: Dr West receives research funding from the National Institutes of Health, the Wellcome Trust, the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, the Firland Foundation, and the Henry M. Jackson Foundation. The remaining authors have reported that no potential conflicts of interest exist with any companies/organizations whose products or services may be discussed in this article.

Role of sponsors: The American College of Chest Physicians was solely responsible for the development of these guidelines. The remaining supporters played no role in the development process. External supporting organizations cannot recommend panelists or topics, nor are they allowed prepublication access to the manuscripts and recommendations. Further details on the Conflict of Interest Policy are available online at http://chestnet.org.

Collaborators: Executive Committee: Michael D. Christian, MD, FRCPC, FCCP; Asha V. Devereaux, MD, MPH, FCCP, co-chair; Jeffrey R. Dichter, MD, co-chair; Niranjan Kissoon, MBBS, FRCPC; Lewis Rubinson, MD, PhD; Panelists: Dennis Amundson, DO, FCCP; Michael R. Anderson, MD; Robert Balk, MD, FCCP; Wanda D. Barfield, MD, MPH; Martha Bartz, MSN, RN, CCRN; Josh Benditt, MD; William Beninati, MD; Kenneth A. Berkowitz, MD, FCCP; Lee Daugherty Biddison, MD, MPH; Dana Braner, MD; Richard D Branson, MSc, RRT; Frederick M. Burkle Jr, MD, MPH, DTM; Bruce A. Cairns, MD; Brendan G. Carr, MD; Brooke Courtney, JD, MPH; Lisa D. DeDecker, RN, MS; COL Marla J. De Jong, PhD, RN [USAF]; Guillermo Dominguez-Cherit, MD; David Dries, MD; Sharon Einav, MD; Brian L. Erstad, PharmD; Mill Etienne, MD; Daniel B. Fagbuyi, MD; Ray Fang, MD; Henry Feldman, MD; Hernando Garzon, MD; James Geiling, MD, MPH, FCCP; Charles D. Gomersall, MBBS; Colin K. Grissom, MD, FCCP; Dan Hanfling, MD; John L. Hick, MD; James G. Hodge Jr, JD, LLM; Nathaniel Hupert, MD; David Ingbar, MD, FCCP; Robert K. Kanter, MD; Mary A. King, MD, MPH, FCCP; Robert N. Kuhnley, RRT; James Lawler, Md; Sharon Leung, MD; Deborah A. Levy, PhD, MPH; Matthew L. Lim, MD; Alicia Livinski, MA, MPH; Valerie Luyckx, MD; David Marcozzi, MD; Justine Medina, RN, MS; David A. Miramontes, MD; Ryan Mutter, PhD; Alexander S. Niven, MD, FCCP; Matthew S. Penn, JD, MLIS; Paul E. Pepe, MD, MPH; Tia Powell, MD; David Prezant, MD, FCCP; Mary Jane Reed, MD, FCCP; Preston Rich, MD; Dario Rodriquez, Jr, MSc, RRT; Beth E. Roxland, JD, MBioethics; Babak Sarani, MD; Umair A. Shah, MD, MPH; Peter Skippen, MBBS; Charles L. Sprung, MD; Italo Subbarao, DO, MBA; Daniel Talmor, MD; Eric S. Toner, MD; Pritish K. Tosh, MD; Jeffrey S. Upperman, MD; Timothy M. Uyeki, MD, MPH, MPP; Leonard J. Weireter Jr, MD; T. Eoin West, MD, MPH, FCCP; John Wilgis, RRT, MBA; ACCP Staff: Joe Ornelas, MS; Deborah McBride; David Reid; Content Experts: Amado Baez, MD; Marie Baldisseri, MD; James S. Blumenstock, MA; Art Cooper, MD; Tim Ellender, MD; Clare Helminiak, MD, MPH; Edgar Jimenez, MD; Steve Krug, MD; Joe Lamana, MD; Henry Masur, MD; L. Rudo Mathivha, MBChB; Michael T. Osterholm, PhD, MPH; H. Neal Reynolds, MD; Christian Sandrock, MD, FCCP; Armand Sprecher, MD, MPH; Andrew Tillyard, MD; Douglas White, MD; Robert Wise, MD; Kevin Yeskey, MD.

FUNDING/SUPPORT: This publication was supported by the Cooperative Agreement Number 1U90TP00591-01 from the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention, and through a research sub award agreement through the Department of Health and Human Services [Grant 1 - HFPEP070013-01-00] from the Office of Preparedness of Emergency Operations. In addition, this publication was supported by a grant from the University of California–Davis.

abbreviations:

- MCC

mass critical care

- MDG

Millennium Development Goal

- NGO

nongovernmental organization

- WHO

World Health Organization

Footnotes

COI grids reflecting the conflicts of interest that were current as of the date of the conference and voting are posted in the online supplementary materials.

Publisher's Disclaimer: DISCLAIMER: American College of Chest Physicians guidelines and consensus statements are intended for general information only, are not medical advice, and do not replace professional care and physician advice, which always should be sought for any medical condition. The complete disclaimer for this consensus statement can be accessed at http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.1464S1.

Additional information: The e-Appendix is available in the Supplemental Materials section of the online article.

References

- 1.Daugherty Biddison L, Berkowitz KA, Courtney B, et al. ; on behalf of the Task Force for Mass Critical Care. Ethical considerations: care of the critically ill and injured during pandemics and disasters: CHEST consensus statement. Chest. 2014;146(4_suppl):e145S–e155S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mills A. Health care systems in low- and middle-income countries. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(6):552–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merin O, Kreiss Y, Lin G, Pras E, Dagan D. Collaboration in response to disaster—Typhoon Yolanda and an integrative model. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(13):1183–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geiling J, Burkle FM Jr, West TE, et al. ; on behalf of the Task Force for mass Critical Care. Resource-poor settings: response, recovery, and research: care of the critically ill and injured during pandemics and disasters: CHEST consensus statement. Chest. 2014; 146 (4_suppl): e168S–e177S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ornelas J, Dichter JR, Devereaux AV Kissoon N, Livinski A, Christian MD; on behalf of the Task Force for Mass Critical Care. Methodology: care of the critically ill and injured during pandemics and disasters: CHEST consensus statement. Chest. 2014; 146 (4_suppl): 35S–41S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker T Critical care in low-income countries. Trop Med Int Health. 2009; 14(2):143–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amoateng-Adjepong Y Caring for the critically ill in developing countries–our collective challenge. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(4): 1288–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Besso J, Bhagwanjee S, Takezawa J, Prayag S, Moreno R. A global view of education and training in critical care medicine. Crit Care Clin. 2006; 22(3):539–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Molyneux E Emergency care in poorly resourced settings: trying to make a difference. Engineering Management Journal. 2010:3–4. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barrett H, Bion JF. An international survey of training in adult intensive care medicine. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31(4):553–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Molyneux E. Emergency care for children in resource-constrained countries. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103 (1):11–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adhikari NK, Fowler RA, Bhagwanjee S, Rubenfeld GD. Critical care and the global burden of critical illness in adults. Lancet. 2010;376(9749): 1339–1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fowler RA, Adhikari NK, Bhagwanjee S. Clinical review: critical care in the global context—disparities in burden of illness, access, and economics. Crit Care. 2008;12(5):225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kobusingye OC, Hyder AA, Bishai D, Hicks ER, Mock C, Joshipura M. Emergency medical systems in low- and middle-income countries: recommendations for action. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83(8):626–631. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhagwanjee S Critical care in Africa. Crit Care Clin. 2006;22(3): 433–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riviello ED, Letchford S, Achieng L, Newton MW. Critical care in resource-poor settings: lessons learned and future directions. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(4):860–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burkle FM Jr, Argent AC, Kissoon N; Task Force for Pediatric Emergency Mass Critical Care. The reality of pediatric emergency mass critical care in the developing world. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2011;12(suppl 6):S169–S179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dünser MW, Baelani I, Ganbold L. A review and analysis of intensive care medicine in the least developed countries. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(4): 1234–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Federation of Societies of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine. World coverage of Societies of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine. World Federation of Societies of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine website. http://www.world-critical-care.org/. Accessed August 3, 2014.

- 20.Sumner A. The new bottom billion and the mdgs - a plan of action. IDS in focus policy briefing Institute of Development Studies website. http://www.ids.ac.uk/files/dmfile/IFBottomBillionMDGsweb.pdf. Published 2010. Accessed September 15, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linton DM. Appropriate critical care development in southern Africa. S Afr Med J. 1994; 84 (suppl 11): 795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dünser MW, Festic E, Dondorp A, et al. ; Global Intensive Care Working Group of European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Recommendations for sepsis management in resource-limited settings. Intensive Care Med. 2012; 38 (4): 557–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flabouris A, Hart GK, Nicholls A. Patients admitted to Australian intensive care units: impact of remoteness and distance travelled on patient outcome. Crit Care Resusc. 2012;14(4):256–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duncan AW. The burden of paediatric intensive care: an Australian and New Zealand perspective. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2005; 6(3):166–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goh AY, Abdel-Latif Mel-A, Lum LC, Abu-Bakar MN. Outcome of children with different accessibility to tertiary pediatric intensive care in a developing country—a prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2003; 29 (1): 97–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ho NK. Priorities in neonatal care in developing countries. Singapore Med J. 1996;37(4): 424–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rohde J, Cousens S, Chopra M, et al. 30 years after Alma-Ata: has primary health care worked in countries? Lancet. 2008;372(9642): 950–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phalkey R, Dash SR, Mukhopadhyay A, Runge-Ranzinger S, Marx M. Prepared to react? Assessing the functional capacity of the primary health care system in rural Orissa, India to respond to the devastating flood of September 2008. Glob Health Action. 2012; 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kobusingye OC, Hyder AA, Bishai D, Joshipura M, Hicks ER, Mock C. Emergency medical services. Chapter 68 In: Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, Alleyne G, Claeson M, Evans DB, Jha P, Mills A, Musgrove P, eds. Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2006:1261–1279. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Razzak JA, Kellermann AL. Emergency medical care in developing countries: is it worthwhile? Bull World Health Organ. 2002; 80 (11): 900–905. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parsi K. International medical graduates and global migration of physicians: fairness, equity, and justice. Medscape J Med. 2008;10(12):284. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vincent DS, Berg BW, Ikegami K. Mass-casualty triage training for international healthcare workers in the Asia-Pacific region using manikin-based simulations. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2009; 24 (3): 206–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burkle FM, Walls AE, Heck JP, et al. Academic affiliated training centers in humanitarian health, part I: program characteristics and professionalization preferences of centers in North America. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2013; 28 (2): 155–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wootton R, Bonnardot L, Geissbuhler A, et al. Feasibility of a clearing house for improved cooperation between telemedicine networks delivering humanitarian services: acceptability to network coordinators. Glob Health Action. 2012; 5: 18713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joynt GM, Zimmerman J, Li TS, Gomersall CD. A systematic review of short courses for nonspecialist education in intensive care. J Crit Care. 2011;26(5):533.e1–533.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.English M, Lanata CF, Ngugi I, Smith PC. The district hospital. Chapter 65 In: Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, Alleyne G, Claeson M, Evans DB, Jha P, Mills A, Musgrove P, eds. Source Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. 2nd edition Washington, DC: World Bank; 2006: 1211–1228. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zere E, Mbeeli T, Shangula K, et al. Technical efficiency of district hospitals: evidence from Namibia using data envelopment analysis. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2006;4:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Petroze RT, Nzayisenga A, Rusanganwa V, Ntakiyiruta G, Calland JF. Comprehensive national analysis of emergency and essential surgical capacity in Rwanda. Br J Surg. 2012;99(3): 436–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.LeBrun DG, Chachungal S, Chao TE, et al. Prioritizing essential surgery and safe anesthesia for the Post-2015 development agenda: operative capacities of 78 district hospitals in 7 low- and middle-income countries. Surgery. 2014155(3):365–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Galukande M, von Schreeb J, Wladis A, et al. Essential surgery at the district hospital: a retrospective descriptive analysis in three African countries. PLoS Med. 2010;7(3):e 1000243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Molyneux E, Ahmad S, Robertson A. Improved triage and emergency care for children reduces inpatient mortality in a resource-constrained setting. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84(4):314–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gottschalk SB, Wood D, DeVries S, Wallis LA, Bruijns S, Cape Triage G; Cape Triage Group; Proposal from the Cape Triage Group. The Cape Triage Score: a new triage system South Africa. Emerg Med J. 2006;23(2):149–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gove S, Tamburlini G, Molyneux E, Whitesell P, Campbell H. Development and technical basis of simplified guidelines for emergency triage assessment and treatment in developing countries. WHO Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) Referral Care Project. Arch Dis Child. 1999; 81 (6):473–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khilnani P, Chhabra R. Transport of critically ill children: how to utilize resources in the developing world. Indian J Pediatr. 2008;75(6):591–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Malik ZU, Pervez M, Safdar A, Masood T, Tariq M. Triage and management of mass casualties in a train accident. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2004;14(2):108–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bond GR, Pièche S, Sonicki Z, et al. ; WHO EMRO Pediatric Insecticide Study Group. A clinical decision aid for triage of children younger than 5 years and with organophosphate or carbamate insecticide exposure in developing countries. Ann Emerg Med. 2008; 52 (6):617–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bruijns SR, Wallis LA, Burch VC. A prospective evaluation of the Cape triage score in the emergency department of an urban public hospital in South Africa. Emerg Med J. 2008;25(7):398–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bruijns SR, Wallis LA, Burch VC. Effect of introduction of nurse triage on waiting times in a South African emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2008;25(7):395–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tamburlini G, Di Mario S, Maggi RS, Vilarim JN, Gove S. Evaluation of guidelines for emergency triage assessment and treatment in developing countries. Arch Dis Child. 1999;81(6):478–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carpentier JP, Petrognani R, Raynal M, Ponchel C, Saby R. Natural selection and medical triage: everyday realities [in French]. Med Trop (Mars). 2002; 62(3):263–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosedale K, Smith ZA, Davies H, Wood D. The effectiveness of the South African Triage Score (SATS) in a rural emergency department. S Afr Med J. 2011;101(8):537–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dib JE, Naderi S, Sheridan IA, Alagappan K. Analysis and applicability of the Dutch EMS system into countries developing EMS systems. J Emerg Med. 2006; 30(1):111–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Firoz T, Sanghvi H, Merialdi M, von Dadelszen P. Pre-eclampsia in low and middle income countries. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;25(4):537–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hyder AA, Dawson L. Defining standard of care in the developing world: the intersection of international research ethics and health systems analysis. Dev World Bioeth. 2005;5(2):142–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kapiriri L, Martin DK. Priority setting in developing countries health care institutions: the case of a Ugandan hospital. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006; 6:127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Volkow P, Bautista E, de la Rosa M, Manzano G, Muñoz-Torrico MV, Pérez-Padilla R. The response of the intensive care units during the influenza A H1N1 pandemic: the experience in Chiapas, Mexico [in Spanish]. Salud Publica Mex. 2011;53(4):345–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sarani B, Mehta S, Ashburn M, et al. The academic medical centre and nongovernmental organisation partnership following a natural disaster. Disasters. 2012;36(4):609–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Michaels AJ, Hill JG, Bliss D, et al. Pandemic flu and the sudden demand for ECMO resources: a mature trauma program can provide surge capacity in acute critical care crises. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74(6):1493–1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sarani B, Mehta S, Ashburn M, et al. Evolution of operative interventions by two university-based surgical teams in Haiti during the first month following the earthquake. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2011;26(3):206–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pierce JR Jr, Pittard AE, West TA, Richardson JM. Medical response to hurricanes Katrina and Rita: local public health preparedness in action. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2007;13(5): 441–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sippel S, Muruganandan K, Levine A, Shah S. Review article: use of ultrasound in the developing world. Int J Emerg Med. 2011;4:72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Levine AC, Shah SP, Umulisa I, et al. Ultrasound assessment of severe dehydration in children with diarrhea and vomiting. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(10):1035–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jacob ST, Lim M, Banura P, et al. Integrating sepsis management recommendations into clinical care guidelines for district hospitals in resource-limited settings: the necessity to augment new guidelines with future research. BMC Med. 2013;11:107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Farmer JC, Carlton PK Jr. Providing critical care during a disaster: the interface between disaster response agencies and hospitals. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(suppl 3):S56–S59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nkengasong JN, Mesele T, Orloff S, et al. Critical role of developing national strategic plans as a guide to strengthen laboratory health systems in resource-poor settings. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;131(6): 852–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fonjungo PN, Kebede Y, Messele T, et al. Laboratory equipment maintenance: a critical bottleneck for strengthening health systems in sub-Saharan Africa? J Public Health Policy. 2012;33(1):34–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kotagal M, Lee P, Habiyakare C, et al. Improving quality in resource poor settings: observational study from rural Rwanda. BMJ. 2009;339:b3488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lanata CF. Human resources in developing countries. Lancet. 2007; 369(9569):1238–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bremer R Policy development in disaster preparedness and management: lessons learned from the January 2001 earthquake in Gujarat, India. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2003;18(4):372–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Burkle FM Jr. Do pandemic preparedness planning systems ignore critical community- and local-level operational challenges? Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2010;4(1):24–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ungchusak K, Sawanpanyalert P, Hanchoworakul W, et al. Lessons learned from influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 pandemic response in Thailand. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18(7):1058–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lumb PD. The World Federation: enhancing global critical care practice and performance. Crit Care Clin. 2006;22(3): 383–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Anderson PD, Suter RE, Mulligan T, et al. World Health Assembly Resolution 60.22 and its importance as a health care policy tool for improving emergency care access and availability globally. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(1):35–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.