Abstract

Age-related hearing loss (or presbyacusis) is a progressive pathophysiological process. This study addressed the hypothesis that degeneration/dysfunction of multiple non-sensory cell types contributes to presbyacusis by evaluating tissues obtained from young and aged CBA/CaJ mouse ears and human temporal bones. Ultrastructural examination and transcriptomic analysis of mouse cochleas revealed age-dependent pathophysiological alterations in three types of neural crest-derived cells, namely intermediate cells in the stria vascularis, outer sulcus cells in the cochlear lateral wall and satellite cells in the spiral ganglion. A significant decline in immunoreactivity for Kir4.1, an inwardly rectifying potassium channel, was seen in strial intermediate cells and outer sulcus cells in the ears of older mice. Age-dependent alterations in Kir4.1 immunostaining also were observed in satellite cells ensheathing spiral ganglion neurons. Expression alterations of Kir4.1 were observed in these same cell populations in the aged human cochlea. These results suggest that degeneration/dysfunction of neural crest-derived cells maybe an important contributing factor to both metabolic and neural forms of presbyacusis.

Keywords: presbyacusis, human temporal bone, neural crest-derived cells, Kir4.1, auditory nerve, stria vascularis, spiral ganglion

1. Introduction

Age-related hearing loss (presbyacusis) is a global public health problem that impacts the well-being of many elderly people. Presbyacusis is characterized by declines in hearing sensitivity and understanding of speech, especially in noisy environments, slowed central processing of acoustic information and impaired localization of sound sources (Gates and Mills, 2005). Overall, about 30% of Americans aged 65–74 and 50% of those over 75 have impaired hearing (Gates and Mills, 2005). There are at least three types of presbyacusis; sensory, strial (or metabolic) and neural, which can occur alone or together in individual subjects. Studies of human temporal bones strongly indicate that presbyacusis, in the absence of significant noise trauma, stems from degeneration/dysfunction of non-sensory regions of the cochlea, such as in the stria vascularis and auditory nerve rather than sensory hair cells in the organ of Corti (Schuknecht and Gacek, 1993; Kusunoki et al, 2004; Suzuki et al, 2006; Makary et al, 2011; Gates and Mills, 2005). In the mammalian cochlea, several types of non-sensory cells including strial intermediate cells and fibrocytes in the lateral wall and glial cells in the auditory nerve are capable of regeneration under stressful conditions, although their ability to repopulate/self-repair declines with age (Yamasoba et al., 2003; Lang et al., 2003; Lang et al., 2011). Neural crest cell lineages give rise to several types of non-sensory cells in the inner ear, including strial intermediate cells, mesenchymal cells in the spiral ligament and glial cells of the auditory nerve (Hilding and Ginzberg, 1977; Dupin and Sommer, 2012; Locher et al., 2014). Previous studies in animal models have demonstrated that degeneration of the cochlear lateral wall and a corresponding reduction in the endocochlear potential (EP) play a prominent role in presbyacusis (Schulte and Schmiedt, 1992; Spicer et al., 1996; Schmiedt et al.,1996; Schmiedt, 2009; Lang et al., 2010). In this study, we evaluated the hypothesis that degeneration/dysfunction of neural crest-derived cells in the cochlear lateral wall and auditory nerve is associated with presbyacusis using both a CBA/CaJ mouse model and temporal bones obtained from human donors.

Inwardly rectifying potassium (Kir) channels are present in a wide variety of cell types and play critical roles in regulating many cellular activities including signaling processes, resting membrane potentials, neurotransmitter release and neuronal excitability, electrolyte transport in epithelial cells, and cellular contraction and volume changes (Chen and Zhao, 2014; Shieh et al, 2000). Kir channels are divided into seven subfamilies (Kir1.0-Kir7.0) and include more than 20 members based on their molecular and electrophysiological characteristics. The expression of Kir4.1 (KCNJ10) was first reported in glial cells of the central nervous system and then in the kidney, retina and inner ear (Bond et al, 1994; Garcia et al, 2007; Hibino et al, 1997). In the mammalian cochlea, Kir4.1 is expressed in the cochlear lateral wall, satellite cells surrounding spiral ganglion neurons (SGNs) and supporting cells in the organ of Corti (Hibino et al, 1997; Ando et al, 1999; Rozengurt et al, 2003; Jagger et al, 2010; Kim et al., 2013). It is believed that Kir4.1 expression in the cochlea is necessary for 1) generation and maintenance of the EP and the high K+ concentration in endolymph, and 2) buffering by satellite cells of K+ ions expelled from neurons during excitation in the auditory nerve (see review by Chen and Zhao, 2014). In the central nervous system, dysregulation of astroglial Kir4.1 has been reported to occur in animal models representing a wide array of neurological diseases such as Huntington’s disease (Tong et al., 2014), Rett syndrome (Lioy et al., 2011) and depression (Cui et al., 2018). Astroglial Kir4.1 also is dysregulated in older mice subjected to traumatic brain injury (Gupta and Prasad 2013). In this study, we examined changes in the pattern and levels of Kir4.1 expression to determine the functional integrity of neural crest-derived cells with age in cochleas obtained from CBA/CaJ mice and human temporal bones.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

CBA/CaJ mice have been widely used as a model to study late-onset hearing loss (Ohlemiller, 2009; Ohlemiller et al, 2010). For this study, CBA/CaJ mice were divided into two groups; young adult (1.5–3 months old) and aged (1.5–2.5) years-old. The groups included both sexes. The mice were derived from breeders purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Stock number: 000654; Bar Harbor, ME). The animals were bred and housed in a low noise environment and maintained on a 12h light/dark cycle at the animal research facility of the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC). All procedures were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of MUSC’s Institutional Animal Care and Use (IACUC) Committee.

2.2. Measurement of auditory brainstem response (ABR) and endocochlear potential

ABR measurements were performed on all mice prior to sacrifice. The mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection with a mixture of xylazine (20 mg/kg) and ketamine (100 mg/kg) as described previously (Hao et al, 2014; Panganiban et al., 2018). ABRs were recorded using subdermal needle electrodes at the vertex (+) and test-side mastoid (−), with a ground in the control side leg. Sound levels were reduced in 5-dB steps from 90 dB SPL to 10 dB SPL. ABR waveforms and thresholds were analyzed at individual frequencies ranging from 4.0 to 45.2 kHz. ABR wave I thresholds were obtained and defined as the lowest sound levels at which a repeatable wave I signal could be identified in the response waveforms.

The endocochlear potential (EP) was measured in the basal turn of the cochlea. The EP was recorded with a micropipette filled with 0.2 M KCl yielding an impedance of 25–40 MΩ connected to an electrometer (Duo773; World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) for direct recording of the potential. The micropipette was introduced into the scala media via 30–50 μm holes drilled through the otic capsule in the basal turn.

For each age group, ABR wave I thresholds, the maximum wave I amplitudes and EP values were averaged and mean ± SEM values were calculated and plotted using Origin 6.0 software (OriginLab) and GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software). Data for ABR wave I thresholds and EP levels were analyzed by Student’s unpaired t test or Mann-Whitney test. A value of p˂0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. After ABR and EP measures, the mice were deeply anesthetized, and cochlear tissues were collected for gene array, ultrastructural or immunohistochemical analysis as described below.

2.3. DNA microarray analysis

Total RNA samples were prepared from the auditory nerve and cochlear lateral wall of young adult and aged mice. Three independent samples consisting of tissue from six cochleas were prepared for each group; both groups included male and female mice. The total RNA quality was confirmed by Bioanalyzer and then samples were processed and hybridized to GeneChip Mouse 430 2.0 microarrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) as previously described (Lang et al., 2015; Panganiban et al., 2018). Resulting hybridization data were processed with GeneChip Expression Console software (Affymetrix) to derive RMA normalized expression intensities (Irizarry et al., 2003) and MAS5 detection calls. Microarray data are deposited with NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (CLW, accession GSE98070; AN accession GSE121856). Genes relating to neural crest cell function were assembled by query of the Gene Ontology Database (Ashburner et al., 2000; The Gene Ontology Consortium 2017_PMID: 27899567) and the WikiPathways database (Slenter et al., 2018). Comparative analyses of neural crest-related genes were conducted using dchip software (Li and Wong 2001) with p<0.05 (Student’s t-test, unpaired) interpreted as significant. False discovery rates were estimated by iterative comparisons involving randomized sampling groupings.

2.4. Preparation of mouse cochleas for morphological and histochemical studies

For ultrastructural observation, deeply anesthetized mice were sacrificed by intracardial perfusion of a mixture of 4% paraformaldehyde and 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). After cochlear dissection, the oval and round windows were opened, the same fixative was perfused into the scalea through the oval window. The cochleas were subsequently immersed in fixative at 4°C overnight and decalcified in 0.12M EDTA for 2–3 days. The same procedure was used to process cochleas for immunohistochemistry, except that the fixative was 4% paraformaldehyde and the total exposure time to fixative was limited to 2 hours. The cochlear tissues were decalcified in EDTA, cryoprotected in 30% sucrose in PBS and embedded in Tissue-Tek OCT compound.

2.5. Transmission electron microscopy and quantitative analysis of intermediate cell structural integrity.

For ultrastructural analysis, mouse cochlear tissues were post-fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide for 1 hour, dehydrated and embedded in Epon LX 112 resin. Semi-thin sections about 1 um thick were cut and stained with toluidine blue. Ultra-thin sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined by electron microscopy as previously described (Lang et al, 2011; Panganiban et al., 2018). The quantitative analysis of the intermediate cell structural integrity was performed by measuring the intermediate cell functional area defined as the strial regions occupied by processes of intermediate cells interdigitating with those of marginal cells (the shaded areas in Fig. 2H,2I). Approximately 100 to 600 μm2 areas (occupying the region from the apex of the marginal cells to the bottom of the basal cell level) were randomly selected from middle turns (n=6 ears for young adult group and n=4 ears for aged group). Area measurements were conducted manually with the assistance of the histogram function in Adobe Photoshop CS.

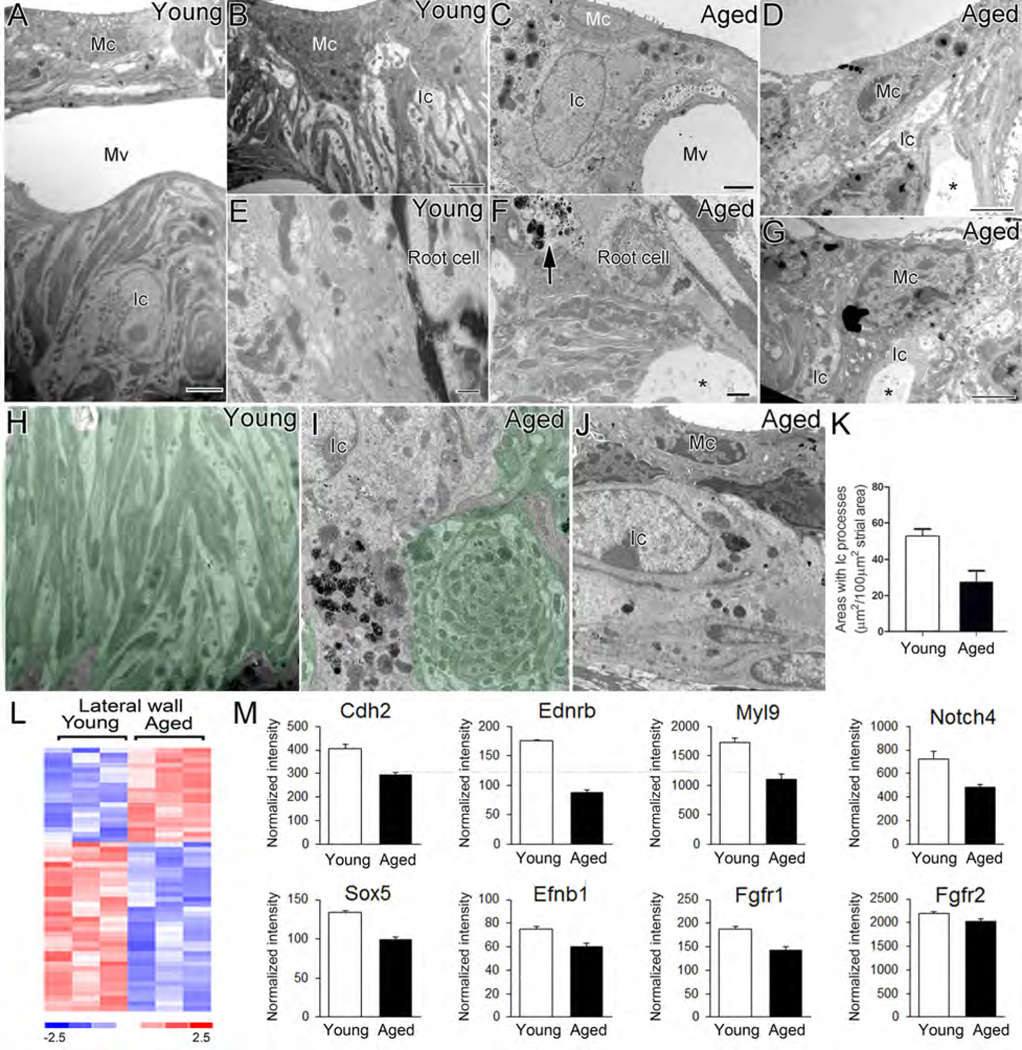

Fig. 2.

Age-related alterations in ultrastructure and expression patterns of neural crest-related genes in the mouse cochlear lateral wall. (A-J) TEM images of intermediate cells in the stria vascularis and root cells in the spiral ligament of young (A, B, E) and aged (C, D, F, G) mice. Partial loss (C, D, G, I), or a total loss (J) of the intermediate cell processes, and an increase of cellular debris (arrow) and vacuolization (*) around root cell processes (F) was seen in aged cochleas. Enlarged extracellular spaces (*) between marginal and intermediate cell processes (D, G) and abnormal intermediate cell processes (swirl-like structure; I) were often seen in the aged stria vascularis. (K) A significant loss in the area occupied by intermediate cell processes occurred in the aged group compared to young controls (Mann-Whitney test; p<0.05; n=6 mice for young adult group and n=4 mice for the aged group). (L) Heatmap of microarray data showing differential expression of 53 neural crest-genes in the aged cochlear lateral wall compared to young adult controls (p<0.05; Student’s t-test, unpaired, two-tailed, not assuming equal variance). The false discovery rate for this comparison approximated 15%. (M) Microarray expression values are shown for representative neural crest-related genes in the cochlear lateral wall. Mc, marginal cell; Ic, intermediate cell; Bc, basal cell; Mv, microvasculature. Scale bar: 2 μm in A, B, C; 1 mm in F; 500 nm in E; 10 μm in D, G; 1.5μm in H, 800 nm in I, 2 μm in J.

2.6. Collection and processing of human temporal bones (HTB)

Human temporal bones were selected from a collection obtained as part of a longitudinal study of age-related hearing loss conducted by the Clinical Research Center (P50) at MUSC in partnership with the Carroll A. Campbell, Jr., Neuropathology Laboratory (Brain Bank) at MUSC (Xing et al., 2012; Hao et al, 2014). All procedures used for the harvesting of temporal bones were approved by the MUSC Institutional Review Board under protocol E-607R and Pro00030845, with written consent obtained in all cases. Table 1 lists the age, sex and postmortem time to fixation for the 12 human temporal bones used in this study. Immediately following specimen removal (Schuknecht, 1968), the temporal bones were fixed by perilymphatic perfusion with 20 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde solution according to previously described techniques (Xing et al., 2012; Hao et al, 2014). After 48 hours, the perfused temporal bones were rinsed with PBS and decalcified using a microwave-assisted protocol as per our previous description (Cunningham et al, 2001). The total time of decalcification was about 3–6 weeks and the temporal bones were gradually trimmed to remove most of the hard bone encasing the cochlea and vestibular apparatus.

Table 1.

Summary of human donor information and Kir4.1 immunoreactivity.

| ID | Age | Sex | Death to perfusion interval | Kir4.1 immunostaining | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STV | RP | OCT | RC | ||||

| H95 | 30 | male | 13h15min | ++ | − | + | − |

| H98 | 31 | male | 7h | + | + | + | + |

| H61 | 36 | female | 21h19min | + | − | + | − |

| H109 | 42 | male | 8h45min | ++ | + | + | − |

| H87 | 55 | female | 5h50min | + | − | + | − |

| H122 | 57 | female | 12h25min | + | − | + | + |

| H107 | 65 | male | 5h20min | + | − | − | − |

| H94 | 69 | female | 5h25min | − | − | − | − |

| H114 | 75 | female | 3h30min | ++ | − | + | + |

| H33 | 87 | female | 3h35min | + | − | − | − |

| H55 | 86 | male | 4h45min | + | + | + | ++ |

| H34 | 91 | female | 3h15min | + | − | + | ++ |

2.7. Quantitative analysis of Kir 4.1 immunoreactivity

Frozen sections of cochlear tissue from mouse and human specimens were incubated overnight at 4°C with a primary antibody against Kir4.1 (1:100, catalog no: APC035AN0802, Alomone Labs). Second antibodies were biotinylated and binding was detected by labeling with FITC-conjugated avidin D or Texas-conjugated avidin D (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) and nuclei were then counterstained with propidium iodide (PI). To further identify cells expressing Kir4.1 as being neural crest-derived, dual immunostaining was performed with rabbit anti- Kir4.1 and goat anti-Sox10 (1:100, catalog no: sc173 neural crest-derived 42, Santa Cruz, CA). Areas of interest included stria vascularis (STV), root processes (RP) in the spiral ligament and the auditory nerve within Rosenthal’s canal (RC). Quantitative analysis of Kir4.1 staining intensity was compared by measuring luminescence pixel areas in young-adult and aged mouse ears. Confocal images of the Kir4.1 immunostained sections were collected using a Zeiss LSM 880 NLO microscope with ZEN acquisition software (Zeiss). For observations of Kir4.1 expression patterns around SGNs in the mouse, confocal images were collected using either image stacks (Figs. 4 and 5) or a single slice at the depth level where Kir4.1+ satellite cells were most numerous (Fig. 6). All confocal images of the cochlear lateral wall and the auditory nerve in human temporal bone preparations were taken as image stacks (Figs. 7, 8 and 9). Image stacks were taken at 0.75 μm intervals with image sizes of 134.95 μm (x) 134.95 mm (y). Images were processed using ZEN 2012 Blue Edition (Carl Zeiss Microscopy), Application Suite X (version 3.0.2.16120; Leica Microsystems), and Photoshop CC (Adobe Systems). Data for Kir4.1 expression intensity are presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed by two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test (GraphPad Prism). A value of p˂0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

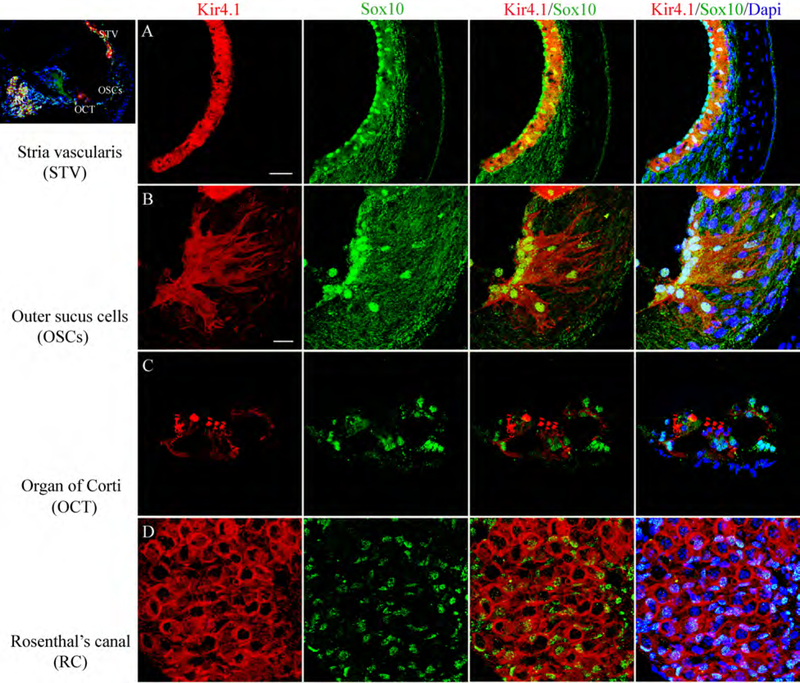

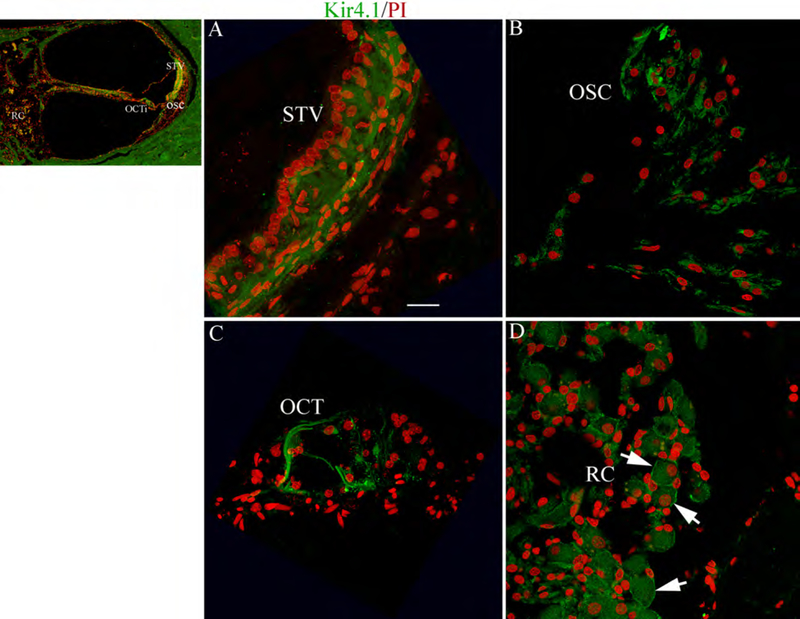

Fig. 4.

Expression of Kir4.1 in neural crest-derived cells of the young adult mouse cochlea. Immunostaining patterns for Kir4.1 (red) and Sox10 (a neural crest-derived cell marker; green) are illustrated in the middle turn of a 2 month-old mouse. (A) Kir4.1 and Sox10 proteins were co-localized in the intermediate cells in the stria vascularis (STV). (B) Outer sulcus cells (OSCs) and their root processes were also co-expressed Sox10, and Kir4.1. (C) Immunoreactive Kir4.1 and Sox10 were also found in supporting cells in the organ of Corti (OCT). (D) A honeycomb-like staining pattern for Kir4.1 reflected in the Sox10+ satellite cells ensheathing spiral ganglion neurons in Rosenthal’s canal (RC). Nuclei were counterstained with Dapi (blue). Scale bars, 25 μm in A; 12 μm in B (applies to C,D).

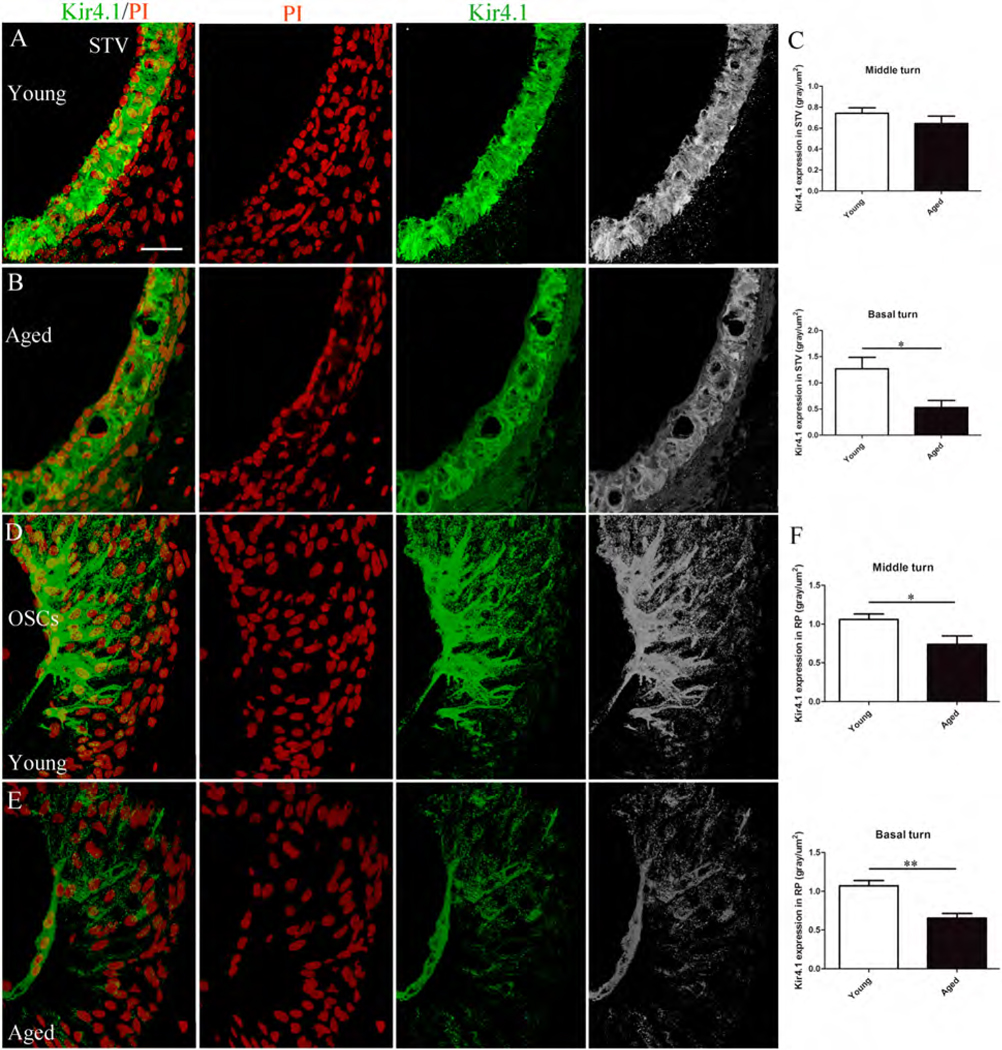

Fig. 5.

Age-related reduction of Kir4.1 expression in the mouse cochlear lateral wall. (A,C) Semiquantation of Kir4.1 expression levels as judged by measurements of fluorescence intensity in the middle and basal turns of the young versus aged group, revealed a significant decline of in the basal but not the middle turns of aged mice. (D-F) Immunostaining for Kir4.1 also declined in OSC root processes of the spiral ligament. A significant reduction of Kir4.1 fluorescence intensity was found in both the middle and basal turns of the aged mice. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, Student’s t test, unpaired, two-tailed; 5 mice for young adult group and 4 mice for aged group). Nuclei were counterstained with PI (red). Scale bar: 25 mm in A (applies to B-E)

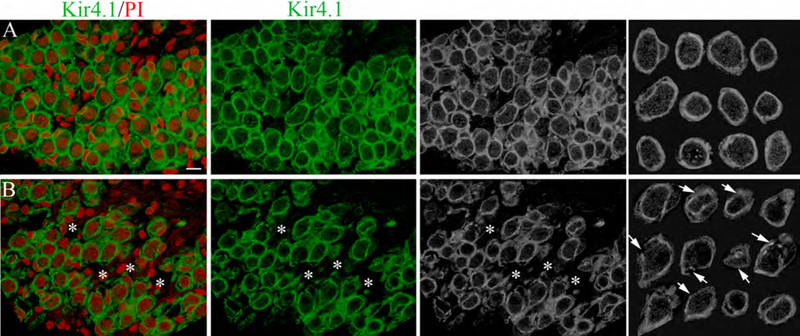

Fig. 6.

Age-related alterations in the Kir4.1 immunostaining pattern in satellite cells. The honeycomb-like Kir4.1 expression pattern reflects satellite cells ensheathing SGNs in the basal turn of young (A) and aged (B) CBA/CaJ mice. Notable alterations in the immunostaining pattern for Kir4.1 were seen in satellite cells of aged mice including discontinuities and thinning of Kir4.1+ components (arrows). The far right panels shows regions randomly selected from images in the left panels. Nuclei were counterstained with PI (red). Scale bar: 8 mm in A (applies to B, except for the right panels).

Fig. 7.

Immunolocalization of Kir4.1 in the human cochlea. (A-D) Similar to the mouse, the Kir4.1 immunoactivity was present in cells of the STV (A), OSCs (B), support cells in the Organ of Corti (C) and satellite cells surrounding SGNs within RC (D, arrows). The cochlear sections were taken from an 86 year-old donor (AC) Nuclei were counterstained with PI (red). Scale bar: 12 mm in A (applies to B-D).

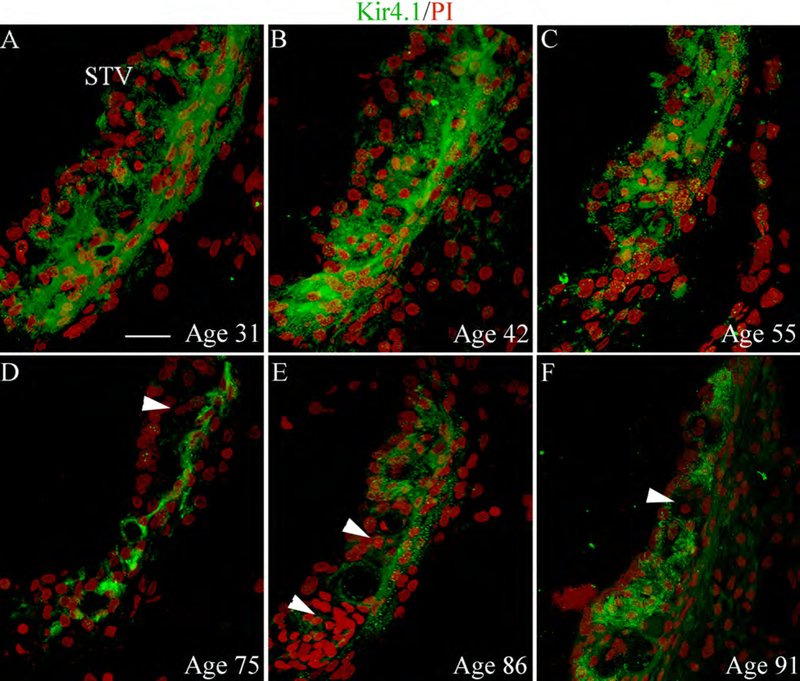

Fig. 8.

Immunostaining patterns for Kir4.1 in the STV from six temporal bones of different ages. (A-F) Kir4.1 immunoreactivity for intermediate cells in the STV generally appeared stronger and more uniform in the ears from the 31, 42 and 55 year-old donors (A-C). (D-E) There was a partial loss or reduction of Kir4.1 immunoreactivity in the STV (arrowheads) of the three human temporal bones from the 75, 86 and 91-year-old donors. All images were taken from the middle turn of the cochlea. Nuclei were counterstained with PI (red). Scale bar: 12 μm in A (applies to B-F).

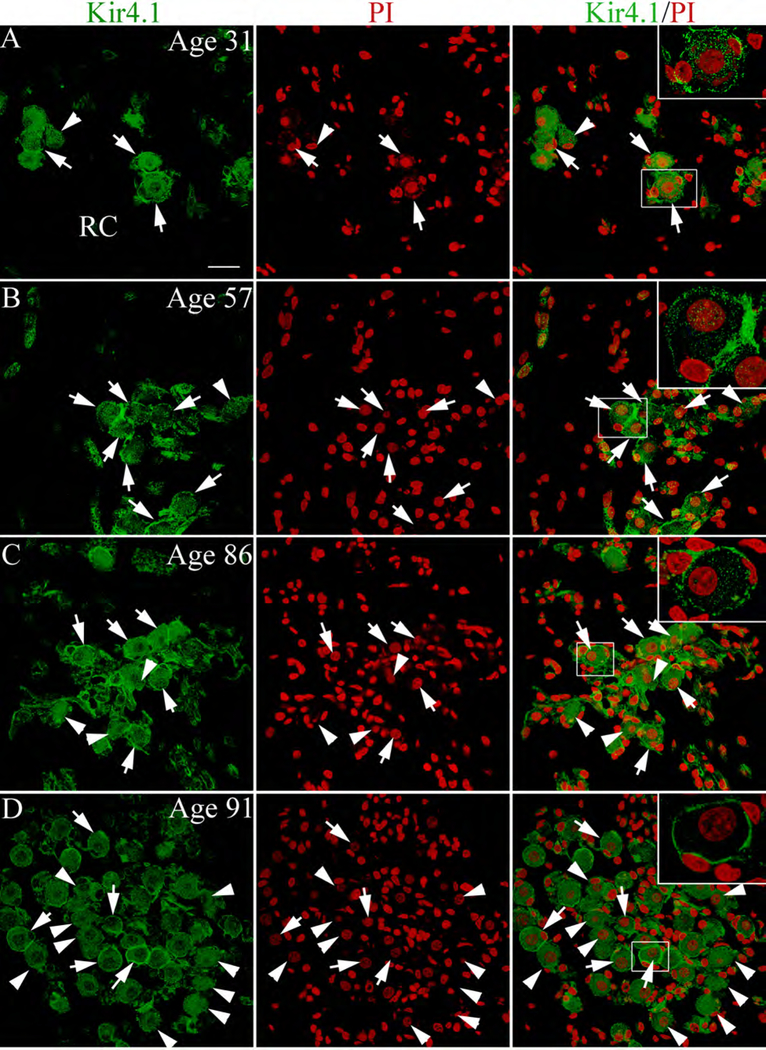

Fig. 9.

Kir4.1 immunoactivity in satellite cells of human spiral ganglion. (A,B) Kir4.1+ satellite cells (arrows) around SGNs seen in the human temporal bones from a 31-year-old donor and a 57-year-old donor. Arrowheads point to SGNs devoid of Kir4.1+ satellite cells. (C,D) increase in Kir4.1− satellite cells was seen in sections from an 86 and 91 year-old donor. Additional information concerning the percentage of Kir4.1+ satellite cells in the spiral ganglion from the younger and older donor groups is provided in Table 2. Nuclei were counterstained with PI (red). Scale bar: 10 μm in A (applies to B-F).

3. Results

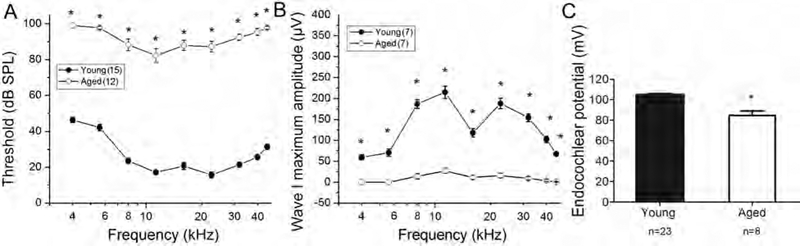

3.1. Age-related auditory function declines in CBA/CaJ mice

CBA/CaJ mice have been widely used as a “normal aging” model in age-related hearing loss research (Henry and Chole 1980; Zheng et al., 1999; Ohlemiller et al., 2004; Sergeyenko et al., 2013). Auditory brain stem responses (ABRs) were measured in young adult controls (n=15) and aged mice (n=12). As shown in Figure 1, significant threshold shifts of 40–60 dB and greatly reduced maximum amplitudes were present in ABR wave I responses in the aged group at all frequencies tested (Student’s unpaired t test; p<0.001). Sharp reductions of maximum amplitudes in ABR wave I responses indicate a decline in the suprathreshold hearing function and suggest a loss of auditory nerve activities (Hellstrom and Schmiedt 1990; Lang et al., 2003). In addition, there was an EP reduction of about 20 mV in old ears compared with young controls (Fig. 1C; Mann-Whitney test; p<0.001).

Fig. 1.

Declines in auditory nerve function in aged CBA/CaJ mice. (A, B) ABR wave I thresholds were elevated and maximum amplitudes were decreased in aged mice (2–2.5 year-old) at all frequencies tested. Differences between young and old CBA/CaJ mice in wave I thresholds (A) and maximum amplitude (B) were significant at all frequencies (Student’s unpaired t test, *p<0.001). (C) An EP reduction was seen in aged compared to the young controls group (Mann-Whitney test; *p<0.001). All data are presented as mean ± SEM.

3.2. Age-related changes in ultrastructural morphology and neural crest cell-associated gene expression in the mouse cochlea

Several cochlear cell types are thought to derive from neural crest. Among them, intermediate cells in the stria vascularis (STV) are classified as neural crest-derived melanocytes, because all stages of melanogenesis, including premelanosomes, melanosomes and melanin granules are found in these cells (Hilding and Ginzberg 1977). Genetic mutations that deplete strial intermediate cells in developing mice result in abnormal strial development and a total loss of the EP (Steel and Barkway, 1989). Reductions in EP also occur when intermediate cells are selectively ablated in adult mice (Kim et al., 2013). Here we evaluated age-related ultrastructural changes in neural crest-derived cells in the cochlear lateral wall and auditory nerve of young adult (n=6) and aged CBA/CaJ mice (n=4). As shown in Figures 2A, 2B, and 2H, the extensive mitochondria-enriched cytoplasmic processes of the strial intermediate cells interdigitate tightly with the more electron dense processes of marginal cells in young adult CBA/CaJ mice. Close apposition of the interdigital processes of intermediate cells with those of marginal cells is critical to proper exchange of ions across these membranes and EP generation (Schulte and Steel 1994; Hirose and Liberman 2003; Spicer et al., 2005). Structural alterations of intermediate cells in the aged mouse STV include partial to total loss of cellular processes (Figs. 2C,2D,2J), and the appearance of enlarged edematous spaces between intermediate and marginal cells (Figs. 2C, 2D, 2G). In the aged STV, abnormal intermediate cell processes in the absence of marginal cell processes often formed a swirl-like structure (Fig. 2I). To quantitative evaluate age-related pathological alterations in the STV we evaluated the areas of normal appearing intercellular interdigitations in the middle turns. The intermediate cell functional area was defined as the area occupied by interdigital intermediate cell processes as shown by shaded areas in Fig 2H, 2I. A significant reduction (~ a 50% loss) in the area of the intermediate cell functional area was found in the aged cochleas (52 ± 4 μm2 per 100 μm2 STV) compared to young controls (27± 6 μm2 per 100 μm2 STV) (Mann-Whitney test; p<0.05). Pathological alterations were also seen in the outer sulcus region in the spiral ligament of aged mice, including loss of the fibril-enriched matrix and accumulation of degenerative debris around root processes (Fig. 2F).

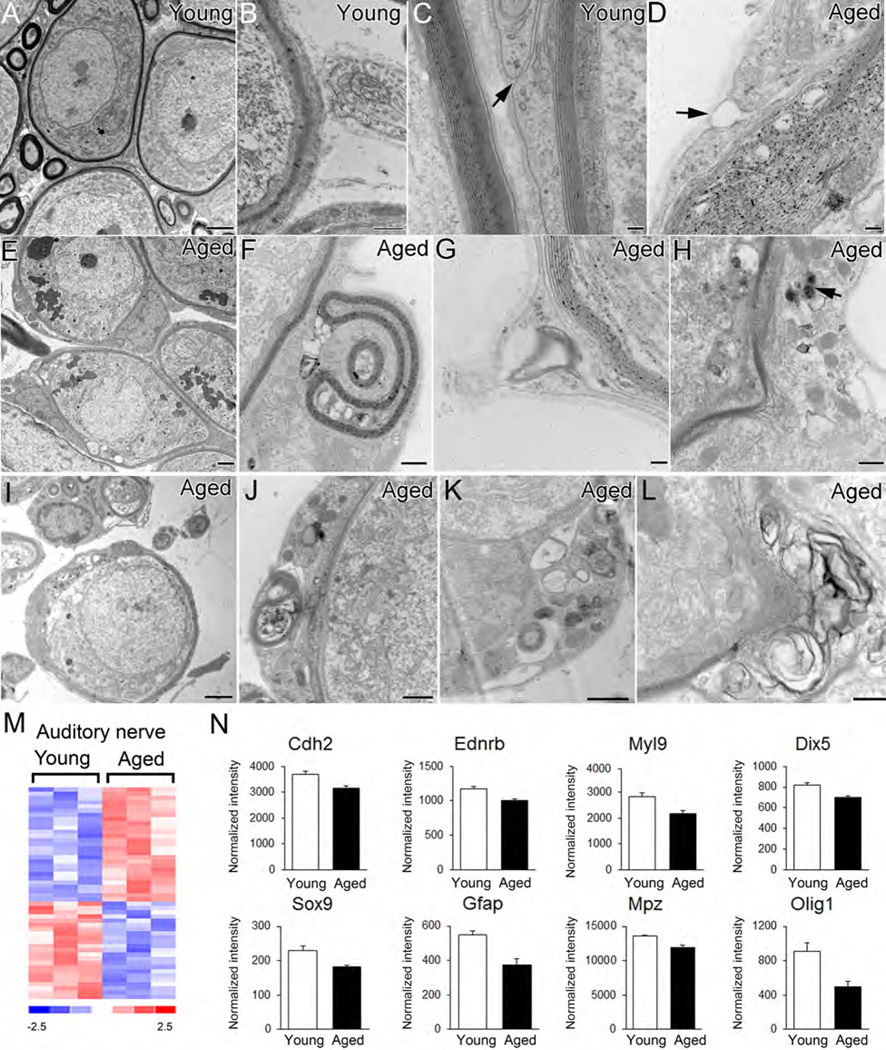

Satellite and Schwan cells in the peripheral auditory nerve are also thought to be of neural crest origin (Jessen and Mirsky 2005; Woodhoo and Sommer 2008). Evaluation of the auditory nerves from the samegroup of mice described above, revealed a number of age-related pathological alterations in the myelinating satellite cells ensheathing SGNs. These changes included disruption of myelin sheaths (Figs. 3D, 3H, 3I, 3K, 3L), the presence of multiple vacuoles in the intralamellar regions (Fig. 3D, 3F, 3I–3K), electron dense inclusion particles (Fig. 3H, 3J,3K), myelin segmentation (Fig 3F, 3G, 3J) and a separation between the external mesaxon members (Fig. 3D). Lipofuscin-like material aggregates were often seen in the cell bodies of spiral ganglion neurons in the aged mice (Fig.3E). The accumulation of lipofuscin aggregates has been reported in aged neurons in numerous locations and is considered to be a hallmark of aging. (Moreno-García et al., 2018).

Fig. 3.

Age-related ultrastructural alterations and changes in neural crest-associated gene expression patterns in the mouse auditory nerve. (A-C) Normal ultrastructural morphology of satellite cells ensheathing type I spiral ganglion neurons (Type I) of young adult mice. Surrounding axons are enclosed by multiple layers of myelin and only narrow gaps are present between members of external mesaxons (arrow). (D-L) Pathological alterations in satellite cells of aged mice include enlarged spaces or vacuoles between myelin layers (D, F) electron dense cytoplasmic inclusions (an arrow in H, J, K), segmented myelin or myelin debris (F, G, I, J, K, L) and a separation of external mesaxon members (arrow in D). A cluster of lipofuscin-like bodies appears in the spiral ganglion neurons of aged mouse cochleas (arrows in E). (M) Heatmap of microarray data showing differential expression of 50 neural crest-related genes in aged cochlear lateral wall compared to young adult controls (genes scored p<0.05; Student’s t-test, unpaired, two-tailed, not assuming equal variance). The false discovery rate for this comparison approximated 24%. (N) Expression values are shown for representative neural crest cell-associated genes in the auditory nerve. Scale bar: 2 mm in A, E, I; 500 nm in B, F, H, K, L; 100 nm in C, D, G; 800 nm in J.

Age-related alterations in the expression pattern of neural crest-related genes were examined by microarray transcriptional profiling of lateral wall and auditory nerve preparations from young adult and aged CBA/CaJ mice. Differential expression analysis identified 53 and 50 neural crest-related genes that were expressed in an age-dependent manner in the cochlear lateral wall and auditory nerve, respectively (Fig. 2L, 3M; Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). A number of these differentially expressed genes, such as Cdh2, Ednrb and Myl9, were down-regulated in both the aged lateral wall and auditory nerve (Fig. 2M, 3N). Other genes were down-regulated in one but not the other region. For example, Notch4, Sox5, Efnb1, Fgfr1 and Fgfr2 were selectively down-regulated in the aged lateral wall, whereas Dix5, Sox9, Gfap, Mpz whereas Olig1 were down-regulated in the aged auditory nerve (Fig. 2M, 3N).

3.3. Kir 4.1 expression in neural crest-derived cells in the mouse cochlea

Sox10 is a neural crest transcription factor with a conserved high-mobility group DNA-binding domain that plays important roles in differentiation and maintenance of melanocytes and peripheral glial cells (Herbarth et al., 1998; Britsch et al., 2001). Anti-Sox10 was used to label nuclei of cochlear neural crest-derived cells in dual staining experiments with Kir 4.1 in the CBA/CaJ mouse cochlea (Fig. 4). In agreement with previous studies on the expression of Kir4.1 in animal models (Hibino et al, 1997; Ando et al, 1999; Rozengurt et al, 2003; Jagger et al, 2010; Kim et al., 2013), Kir4.1 immunoreactivity in the mouse cochlea was present in several cell types of neural crest-origin including intermediate cells in the STV (Fig. 4A), outer sulcus cells in the spiral ligament (Fig. 4B) and satellite cells in the spiral ganglion (Fig. 4D). In addition, Sox10+ supporting cells in the organ of Corti expressed Kir4.1 as previously reported (Hibino et al, 1997).

3.4. Kir4.1 immunostaining in neural crest-derived cells undergoes alterations with age in the mouse cochlea

Cochlear Kir4.1 immunoreactivity was semiquantitatively analyzed by measuring relative fluorescence intensity of sections through the middle and basal turns of young and old mice. The STV (Fig 5A–C) and outer sulcus (Fig 5D–F) of Kir4.1 immunostaining intensity was reduced in strial intermediate cells of aged mice (Figs. 5A,B). The average pixel density of Kir4.1 expression in the STV of young vs aged mice was 0.74 and 0.64 gray/um2 in the middle turn, and 1.26 and 0.52 gray/um2 in the basal turn, respectively (Fig.5C). This reduction in Kir4.1 immunostaining pixel density in aged mice was significant in the basal turn (p˂0.05) but not the middle turn. A reduction in the Kir4.1 immunostaining intensity was also seen in the outer sulcus region of aged mice (Fig. 5D,E). The average Kir4.1+ pixel density in root cells in young and aged mice was 1.06 versus 0.74 gray/um2 for the middle turn, and 1.07 versus 0.65 gray/um2 for the basal turn. These pixel densities in root cell processes were significant between the young and aged mice in both the middle and basal turns (p˂0.05) (Fig. 5F).

The number of SGNs is reduced in aged mice (F6A,6B), in agreement with previous observations of CBA/CaJ mice at a similar age (Ohlemiller et al., 2010). A honeycomb-like Kir4.1+ satellite cell staining pattern was present in the auditory nerve of both young and old mice (Fig. 6A,6B). However, a slight but noticeable difference was seen in the immunostaining pattern of satellite cells in the aged spiral ganglion. These differences included discontinuity and thinning or blurred areas (Fig. 6B) which may also reflect structural changes in the myelin sheath formed by the satellite cells as reported in our previous study (Xing et al., 2012).

3.5. Kir4.1 expression in neural crest-derived cells of the human cochlea

As shown in Table 1, a total of 12 temporal bones from 7 female and 5 male donors aged from 30 to 91 years were examined in this study. The postmortem fixation interval ranged from around 3 to 21 hours. Immunoreactive Kir4.1 was present in human temporal bones in the same cell types as the mouse namely intermediate cells, outer sulcus cells and satellite cells (Fig.7–9). Figure 8 depicts Kir4.1 immunostaining patterns in the stria vascularis of cochleas from middle aged (younger than 55 years-old) and elderly (greater than 75 years old) donors. A notable reduction (or absence) of Kir4.1 immunoreactivity was present in some areas of the stria vascularis in the older ears (Figs. 8D–F). The finding that Kir4.1+ regions in the STV of appeared thinner in the older than the younger temporal bone is consistent with previous studies showing age-related progressive atrophy of the stria vascularis in human temporal bones (Suzuki T et al, 2006).

In the auditory nerve, Kir4.1immunoreactivity also was observed in satellite cells of the human cochleas examined (Fig. 9; Table 1). The percentage of SGNs ensheathed by Kir4.1+ cells was determined in the middle and basal turns of these human temporal bones (Table 2) and ranged from 15 to 32% in the middle turn and 19 to 30% in the basal turn. The younger specimens (aged 31 and 57; Fig. 9A,B) had higher percentages of SGNs associated with Kir4.1+ cells in the basal auditory nerve than did the older ears (aged 86 and 91; Fig. 9C,D). Because the postmortem interval between death and fixation was much longer in the younger as compared to the older specimens we did not attempt to quantify these differences.

Table 2.

Percentages of SGNs with Kir4.1 positive cells in human cochleas

| ID | Age | Sex | Death to perfusion interval | Percentage of SNGs with Kir4.1+ cells (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Middle turn | Basal turn | ||||

| H98 | 31 | male | 7h | 32.47 | 26.03 |

| H122 | 57 | female | 12h35min | 15.32 | 30.44 |

| H114 | 75 | female | 3h30min | 27.03 | 25.68 |

| H55 | 86 | male | 4h45min | 23.14 | 24.24 |

| H34 | 91 | female | 3h15min | 15.08 | 18.92 |

4. Discussion

In this study, we examined age-dependent alterations of Kir4.1 expression in neural crest-derived cells in the mouse and human cochlea. The data demonstrate that Kir4.1immunoreactivity declines significantly with age in strial intermediate cells and outer sulcus cells and their root processes in the mouse cochlear lateral wall. Age-related changes in Kir4.1 immunostaining were also seen in satellite cells ensheathing SGNs in the mouse auditory nerve. However, these changes were less pronounced than those in the lateral wall and most probably were associated with neuronal loss with age. The distribution of Kir4.1 in the human cochlea was similar to that in the mouse. Age-related declines in immunostaining intensity appeared to be present in the stria vascularis but evaluation of more specimens will be required to confirm this and to determine if alterations in the staining patterns of satellite cells occur in older humans.

In the cochlear lateral wall, both strial intermediate cells and outer sulcus cells contribute to the maintenance of K+ ion homeostasis and recycling, which is needed for generation and maintenance of the EP (Schulte and Steel, 1994; Spicer and Schulte, 1996; Wangemann, 2002; Jagger and Forge, 2012). Unlike marginal and basal cells, intermediate cells are melanocytes of neural crest origin (Hilding and Ginzberg, 1977; Steel and Barkway, 1989). During development, intermediate cells migrate to the stria vascularis and, together with marginal cells, form a unique extracellular space termed the “intrastrial space” (Salt et al. 1987). Pathological alteration such as edema were often seen in these intermediate cell associated structures following acute cochlear injury such as ototoxic drug administration (Santi et al., 1985) or noise exposure (Hirose and Liberman 2003). The Kir4.1 channels located in the apical membrane of intermediate cells are needed to keep a very low K+ concentration within the intrastrial space while maintaining a high K+ concentration within the intermediate cells, both of which are critical for generation and maintenance of the EP in this compartment (Hibino and Kurachi, 2006; Wangemann, 2002). Unlike the well-studied strial cells in the lateral wall, the function of outer sulcus cells in the spiral ligament is less well understood (Jagger and Forge, 2012; Shodo et al. 2017). These cells are connected by tight junctions apically and together form a multicellular branched epithelial structure similar to the roots of a tree. The root-like processes project into the spiral ligament where they are surrounded by and closely associated with type 2 fibrocytes and their numerous cellular processes (Kimura, 1984; Galic and Giebel, 1989; Spicer and Schulte, 1996). The expression of Kir4.1 in outer sulcus cells and their root processes was first reported in the guinea pig by Jagger et al. (2010), and later in rat and human cochlea by Eckhard et al (2012). A three-dimensional reconstruction study has confirmed that the root processes provide an enlarged basolateral cell surface area in close apposition to type 2 fibrocytes, allowing more efficient exchange of K+ in the lateral wall (Shodo et al. 2017). The number and size of individual root processes increases from the apex to the base of the cochlea, along with the increased volume density of type 2 fibrocytes, theroretically supporting the greater level of K+ reabsorption needed in the higher frequency encoding regions (Kimura, 1984; Galic and Giebel, 1989; Spicer and Schulte, 1996; Jagger et al. 2010; Jagger and Forge, 2012). Our results revealed that both strial intermediate cells and outer sulcus cells stain positively as Sox10, a marker for neural crest-derived cells. This co-expression of Sox10 and Kir 4.1 in the outer sulcus strongly suggests that similar to strial intermediate cells, they play an important role in K+ circulation and maintenance of the EP.

Age-related atrophy of the stria vascularis has been documented in animal models (Schulte and Schmiedt, 1992; Gratton and Schulte, 1995; Ohlemiller, 2009) and in human temporal bones (Schuknecht et al. 1974; Schuknecht and Gacek, 1993). Ultrastructural examination has also revealed degeneration of strial marginal, intermediate and basal cells in cochleas obtained from older human donors (Takahashi, 1971). Although marginal cells have long been considered as the prime target for degenerative changes in the aged cochlear lateral wall, a combination of marginal and intermediate cell degeneration and/or loss is frequently seen in the late phases of strial atrophy (Thomopoulos et al. 1997; Spicer and Schulte, 2005; Ohlemiller et al. 2010; Hao et al., 2014). The results presented here demonstrating declines in immunostaining for Kir4.1 with age in both strial intermediate and outer sulcus cells, together with quantitative analysis of an age-related decrease in the intermediate cell functional area suggests that both of these cell types, although they may act independently, play a major role in lateral wall K+ homeostasis. Together, these observations indicate that age-dependent dysfunction of at least two different populations of neural crest-derived cells is associated with the EP reduction in the aged CBA/CaJ mouse model of presbyacusis, as shown in this study (Fig. 1C) and a previous study (Ohlemiller et al., 2010). Pathophysiological alterations of neural crest-derived cells in the lateral wall may also contribute to the declines of auditory nerve function seen in animal models of metabolic presbyacusis (the strial form of presbyacusi) as was demonstrated in previous studies (Schmiedt et al., 2003; Lang et al., 2003; Schmiedt 2009). Chronic mild to moderate reductions in the EP have been shown to decrease auditory nerve activity, particularly the activity of low spontaneous rate fibers which is the key auditory nerve fiber subpopulation contributing to the suprathreshold functions of the auditory nerve (Schmiedt 2009).

Another interesting, but not totally unexpected, finding of this study was the age-related change in Kir4.1 immunostaining patterns of satellite cells ensheathing SGNs in both mouse and human cochleas. Mutations in the Kir4.1 (KCNJ10) gene have been linked to a wide range of neurological diseases, such as SeSAME/EAST syndrome (including sensorineural hearing loss), epilepsy and autism spectrum disorders. Evidence is accumulating that Kir4.1 activity contributes to several key functions of glial cells in the central nervous system including the control of resting and hyperpolarized membrane potentials, the maintenance of K+ homeostasis and the regulation of cell volume and glutamate uptake (Guglielmi et al, 2015; Nwaobi et al, 2016; Milton and Smith, 2018). K+ released during neuronal activity is taken up by glia nearby cells via Kir4.1 channels and then extruded from glia into extracellular sinks. The initation and growth of Kir channel activity was found to be coincident with the maturation of glial cell populations (Newman, 1985; Butt and Kalsi, 2006; Sontheimer et al., 1989). In certain pathological conditions such as injury to the trigeminal ganglion or spinal cord, decreases in Kir4.1 channel activity cause changes in neuronal excitability which may lead to abnormal sensory perception as well as the death of motor neurons (Kaiser et al, 2006; Vit et al. 2008). Here, our data show age-dependent alterations in Kir4.1 expression in satellite, but not Schwann cells, in both the mouse and human auditory nerve. These results, together with the demonstration of ultrastructural abnormalities in satellite cells, imply that dysfunction of cochlear glial cells plays a role in abnormal function of the auditory nerve with age and is a contributing factor to neural presbyacusis.

At least three types of human presbyacusis have been described based primarily on pathological changes in specific cell types in the cochlea. (1) There are termed sensory, mainly involving sensory hair cells and supporting cells in the organ of Corti; (2) neural, demonstrated by the loss of neurons or their peripheral processes in the auditory nerve; and (3) strial (metabolic), as a result of the loss/dysfunction of cells within the cochlear lateral wall (Schuknecht et al., 1974; Schuknecht and Gacek 1993). The findings reported here show that abnormalities of Kir4.1 expression can occur with age in several types of non-sensory cells of neural crest origin in different regions of the cochlea. Together these observations provide a cellular basis for the pathophysiological processes associated with both metabolic and neural phenotypes of presbyacusis, which have often been observed together and are most likely to occur as a mixed phenotype.

5. Conclusion

Age-related changes in Kir4.1 immunoreactivity were identified in three different cell types of neural crest origin residing in the lateral wall and spiral ganglion in both the mouse and human cochlea. The results reveal that degeneration/dysfunction of these non-sensory cells in the cochlea is associated with the onset of both metabolic and neural forms of presbyacusis. These observations also support previous studies indicating that two or more forms of presbyacusis can co-exist in the same ear.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Age-related declines in Kir4.1 expression are present in three cochlear cell-types

Neural crest-derived cell degeneration occurs in aged mouse and human cochleas

Pathology of neural crest-derived cells is a contributing factor to presbyacusis

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported (in part) by National Institutes of Health Grants R01DC012058 (H.L.), P50DC00422 (H.L., B.A.S), P30 CA138313 and S10 OD018113 from the Cell & Molecular Imaging Shared Resource and Hollings Cancer Center, and C06 RR014516 from the Extramural Research Facilities Program of the National Center for Research Resources. The project also received support from the South Carolina Clinical and Translational Research (SCTR) Institute with an academic home at the Medical University of South Carolina, NIH/NCRR Grant number UL1RR029882. Microarray experimentation conducted at the MUSC Proteogenomics Facility was supported by NIGMS GM103499 and MUSC’s Office of the Vice President for Research. We thank Juhong Zhu, Nancy Smythe, Reycel Rodriguez and Linda McCarson for their excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Ando M, Takeuchi S, 1999. Immunological identification of an inward rectifier K+ channel (Kir4.1) in the intermediate cell (melanocyte) of the cochlear stria vascularis of gerbils and rats. Cell Tissue Res. 298:179–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, Harris MA, Hill DP, Issel-Tarver L, Kasarskis A, Lewis S, Matese JC, Richardson JE, Ringwald M, Rubin GM, Sherlock G, 2000. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 25(1):25–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond CT, Pessia M, Xia XM, Lagrutta A, Kavanaugh MP, Adelman JP, 1994. Cloning and expression of a family of inward rectifier potassium channels. Receptors Channels. 2:183–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britsch S, Goerich DE, Riethmacher D, Peirano RI, Rossner M, et al. 2001. The transcription factor Sox10 is a key regulator of peripheral glial development. Genes Dev. 15:66–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchwald JS, Huang C, 1975. Far-field acoustic response: origins in the cat. Science. 189(4200):382–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt AM, Kalsi A, 2006. Inwardly rectifying potassium channels (Kir) in central nervous system glia: a special role for Kir4.1 in glial functions. J Cell Mol Med. 10(1):33–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Zhao HB, 2014. The role of an inwardly rectifying K(+) channel (Kir4.1) in the inner ear and hearing loss. Neuroscience. 265:137–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CD, Schulte BA, Bianchi LM, Weber PC, Schmiedt BN, 2001. Microwave decalcification of human temporal bones. Laryngoscope. 111:278–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y, Yang Y, Ni Z, Dong Y, Cai G, Foncelle A, Ma S, Sang K, Tang S, Li Y, Shen Y, Berry H, Wu S, Hu H, 2018. Astroglial Kir4.1 in the lateral habenula drives neuronal bursts in depression. Nature. 554(7692):323–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupin E, Sommer L, 2012. Neural crest progenitors and stem cells: From early development to adulthood. Dev Biol. 366(1):83–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhard A, Gleiser C, Rask-Andersen H, Arnold H, Liu W, Mack A, Müller M, Löwenheim H, Hirt B, 2012. Co-localisation of Kir4.1 and AQP4 in rat and human cochleae reveals a gap in water channel expression at the transduction sites of endocochlear K(+) recycling routes. Cell Tissue Res.350(1):27–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galic M, Giebel W, 1989. An electron microscopic study of the function of the root cells in the external spiral sulcus of the cochlea. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 461:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia MA, Meca R, Leite D, Boim MA, 2007. Effect of renal ischemia/reperfusion on gene expression of a pH-sensitive K+ channel. Nephron Physiol. 106:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates GA, Mills JH, 2005. Presbycusis. Lancet. 366(9491):1111–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratton MA, Schulte BA, 1995. Alterations in microvasculature are associated with atrophy of the stria vascularis in quiet-aged gerbils. Hear Res. 82(1):44–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guglielmi L, Servettini I, Caramia M, Catacuzzeno L, Franciolini F, D’Adamo MC, Pessia M, 2015. Update on the implication of potassium channels in autism: K(+) channelautism spectrum disorder. Front Cell Neurosci. 9:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta RK, Prasad S, 2013. Early down regulation of the glial Kir4.1 and GLT-1 expression in pericontusional cortex of the old male mice subjected to traumatic brain injury. Biogerontology. 14(5):531–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao X, Xing Y, Moore MW, Zhang J, Han D, Schulte BA, Dubno JR, Lang H, 2014. Sox10 expressing cells in the lateral wall of the aged mouse and human cochlea. PLoS One. 9(6):e97389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbarth B, Pingault V, Bondurand N, Kuhlbrodt K, Hermans-Borgmeyer I, et al. 1998. Mutation of the Sry-related Sox10 gene in Dominant megacolon, a mouse model for human Hirschsprung disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 95: 5161–5165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry KR, Chole RA, 1980. Genotypic differences in behavioral, physiological and anatomical expressions of age-related hearing loss in the laboratory mouse. Audiology. 19(5):369–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibino H, Horio Y, Inanobe A, Doi K, Ito M, Yamada M, Gotow T, Uchiyama Y, Kawamura M, Kudo T, Kurachi Y, 1997. An ATP-dependent inwardly rectifying potassium channel, KAB-2 (Kir4.1), in cochlear stria vascularis of inner ear: its specific subcellular localization and correlation with the formation of endocochlear potential. J Neurosci. 17:4711–4721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibino H, Kurachi Y, 2006. Molecular and physiological bases of the K+ circulation in the mammalian inner ear. Physiology (Bethesda). 21:336–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilding DA, Ginzberg RD, 1977. Pigmentation of the stria vascularis. The contribution of neural crest melanocytes. Acta Otolaryngol. 84(1–2):24–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose K, Liberman MC, 2003. Lateral wall histopathology and endocochlear potential in the noise-damaged mouse cochlea. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 4(3):339–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F, Beazer-Barclay YD, Antonellis KJ, Scherf U, Speed TP, 2003. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics. 4(2):249–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagger DJ, Forge A, 2012. The enigmatic root cell - emerging roles contributing to fluid homeostasis within the cochlear outer sulcus. Hear Res. 303:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagger DJ, Nevill G, Forge A, 2010. The Membrane Properties of Cochlear Root Cells are Consistent with Roles in Potassium recirculation and Spatial Buffering. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 11(3):435–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessen KR, Mirsky R, 2005. The origin and development of glial cells in peripheral nerves. Nat Rev Neurosci. 6(9):671–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser M, Maletzki I, Hulsmann S, Holtmann B, Schulz-Schaeffer W, Kirchhoff F, Bahr M, Neusch C, 2006. Progressive loss of a glial potassium channel (KCNJ10) in the spinal cord of the SOD1 (G93A) transgenic mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurochem 99, 900–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Gratton MA, Lee JH, Perez Flores MC, Wang W, Doyle KJ, Beermann F, Crognale MA, Yamoah EN, 2013. Precise toxigenic ablation of intermediate cells abolishes the “battery” of the cochlear duct. J Neurosci. 33(36):14601–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura RS, 1984. Sensory and accessory epithelia of the cochlea In: Friedmann I, Ballantyne J (eds) Ultrastructural Atlas of the inner ear. Butterworths, London, pp 101–132. [Google Scholar]

- Kusunoki T, Cureoglu S, Schachern PA, Baba K, Kariya S, Paparella MM, 2004. Age-related histopathologic changes in the human cochlea: a temporal bone study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 131(6):897–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang H, Li M, Kilpatrick LA, Zhu J, Samuvel DJ, Krug EL, Goddard JC, 2011. Sox2 upregulation and glial cell proliferation following degeneration of spiral ganglion neurons in the adult mouse inner ear. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 12: 151–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang H, Schulte BA, Schmiedt RA, 2003. Effects of chronic furosemide treatment and age on cell division in the adult gerbil inner ear. JARO 04, 164–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang H, Jyothi V, Smythe NM, Dubno JR, Schulte BA, Schmiedt RA, 2010. Chronic reduction of endocochlear potential reduces auditory nerve activity: further confirmation of an animal model of metabolic presbyacusis. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 11, 419–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang H, Xing Y, Brown LN, Samuvel DJ, Panganiban CH, Havens LT, Balasubramanian S, Wegner M, Krug EL, Barth JL, 2015. Neural stem/progenitor cell properties of glial cells in the adult mouse auditory nerve. Sci Rep. 5:13383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Wong WH, 2001. Model-based analysis of oligonucleotide arrays: expression index computation and outlier detection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 98(1):31–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lioy DT, Garg SK, Monaghan CE, Raber J, Foust KD, Kaspar BK, Hirrlinger PG, Kirchhoff F, Bissonnette JM, Ballas N, Mandel G, 2011. A role for glia in the progression of Rett’s syndrome. Nature. 475(7357):497–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locher H, de Groot JC, van Iperen L, Huisman MA, Frijns JH, Chuva de Sousa Lopes SM, 2014. Distribution and development of peripheral glial cells in the human fetal cochlea. PLoS One. 9(1):e88066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makary CA, Shin J, Kujawa SG, Liberman MC, Merchant SN, 2011. Age-related primary cochlear neuronal degeneration in human temporal bones. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 12(6):711–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milton M, Smith PD, 2018. It’s All about Timing: The Involvement of Kir4.1 Channel Regulation in Acute Ischemic Stroke Pathology. Front Cell Neurosci. 12:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-García A, Kun A, Calero O, Medina M, Calero M, 2018. An overview of the role of lipofuscin in age-related neurodegeneration. Front Neurosci. 12:464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman EA, 1985. Voltage-dependent calcium and potassium channels in retinal glial cells. Nature. 317(6040):809–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nwaobi SE, Cuddapah VA, Patterson KC, Randolph AC, Olsen ML, 2016. The role of glial-specific Kir4.1 in normal and pathological states of the CNS. Acta Neuropathol. 132(1):1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlemiller KK, Gagnon PM, 2004. Apical-to-basal gradients in age-related cochlear degeneration and their relationship to “primary” loss of cochlear neurons. J Comp Neurol. 479(1):103–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlemiller KK, 2009. Mechanisms and genes in human strial presbycusis from animal models. Brain Res. 1277:70–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlemiller KK, Dahl AR, Gagnon PM, 2010. Divergent aging characteristics in CBA/J and CBA/CaJ mouse cochleae. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 11(4):605–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panganiban CH, Barth JL, Darbelli L, Xing Y, Zhang J, Li H, Noble KV, Liu T, Brown LN, Schulte BA, Richard S, Lang H. Noise-induced dysregulation of Quaking RNA binding proteins contributes to auditory nerve demyelination and hearing loss. J Neurosci. 38(10):2551–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozengurt N, Lopez I, Chiu CS, Kofuji P, Lester HA, Neusch C, 2003. Time course of inner ear degeneration and deafness in mice lacking the Kir4.1 potassium channel subunit. Hear Res. 177:71–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salt AN, Melichar I, Thalmann R, 1987. Mechanisms of endocochlear potential generation by stria vascularis. Laryngoscope. 97:984–991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santi PA, Lakhani BN, Edwards LB, Morizono T. Cell volume density alterations within the stria vascularis after administration of a hyperosmotic agent. Hear Res. 1985. June;18(3):283–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmiedt RA, 1996. Effects of aging on potassium homeostasis and the endocochlear potential in the gerbil cochlea. Hear Res. 102(1–2):125–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmiedt RA, Mills JH, Boettcher FA, 1996. Age-related loss of activity of auditory-nerve fibers. J Neurophysiol. 76(4):2799–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmiedt RA, 2009. The physiology of cochlear presbyacusis In: The aging auditory system: Perceptual characterization and neural bases of presbyacusis. Gordon-Salant S, Frisina RD, Poper AN, Fay RR, eds., New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Schuknecht H, 1968. Temporal bone removal at autopsy. Preparation and uses. Arch Otolaryngol. 87(2):129–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuknecht HF, Gacek MR, 1993. Cochlear pathology in presbyacusis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 102(1 Pt 2):1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuknecht HF, Watanuki K, Takahashi TT, Belal AA Jr., Kimura RS, Jones DD, Ota CY, 1974. Atrophy of the stria vascularis, a common cause for hearing loss. Laryngoscope. 84(10):1777–1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte BA, Schmiedt RA, 1992. Lateral wall Na,K-ATPase and endocochlear potentials decline with age in quiet-reared animals. Hear Res. 61(1–2):35–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte BA, Steel KP 1994. Expression of alpha and beta subunit isoforms of Na,K-ATPase in the mouse inner ear and changes with mutations at the Wv or Sid loci. Hearing Res 78: 65–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergeyenko Y, Lall K, Liberman MC, Kujawa SG, 2013. Age-related cochlear synaptopathy: an early-onset contributor to auditory functional decline. J Neurosci. 33(34):13686–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shieh CC, Coghlan M, Sullivan JP, Gopalakrishnan M, 2000. Potassium channels: molecular defects, diseases, and therapeutic opportunities. Pharmacol Rev. 52(4):557–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shodo R, Hayatsu M, Koga D, Horii A, Ushiki T, 2017. Three-dimensional reconstruction of root cells and interdental cells in the rat inner ear by serial section scanning electron microscopy. Biomed Res. 38(4):239–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slenter DN, Kutmon M, Hanspers K, Riutta A, Windsor J, Nunes N, Mélius J, Cirillo E, Coort SL., Digles D, Ehrhart F, Giesbertz P, Kalafati M, Martens M, Miller R, Nishida K, Rieswijk L, Waagmeester A, Eijssen LMT, Evelo CT, Pico AR, Willighagen EL, 2018. WikiPathways: a multifaceted pathway database bridging metabolomics to other omics research. Nucleic Acids Res. 46(D1):D661–D667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sontheimer H, Trotter J, Schachner M, Kettenmann H, 1989. Channel expression correlates with differentiation stage during the development of oligodendrocytes from their precursor cells in culture. Neuron. 2(2):1135–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spicer SS, Schulte BA, 1996. The fine structure of spiral ligament cells relates to ion return to the stria and varies with place-frequency. Hear Res. 100:80–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spicer SS, Schulte BA, 2005. Pathologic changes of presbycusis begin in secondary processes and spread to primary processes of strial marginal cells. Hear Res. 205(1–2):225–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steel KP, Barkway C, 1989. Another role for melanocytes: their importance for normal stria vascularis development in the mammalian inner ear. Development. 107(3):453–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Nomoto Y, Nakagawa T, Kuwahata N, Ogawa H, Suzuki Y, Ito J, Omori K, 2006. Age-dependent degeneration of the stria vascularis in human cochleae. Laryngoscope. 116(10):1846–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, 1971. The ultrastructure of the pathologic stria vascularis and spiral prominence in man. Ann Oto Rhin Laryn. 80(5):721–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Gene Ontology Consortium. Expansion of the Gene Ontology knowledgebase and resources. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017. Jan 4;45(D1):D331–D338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomopoulos GN, Spicer SS, Gratton MA, Schulte BA, 1997. Age-related thickening of basement membrane in stria vascularis capillaries. Hear Res. 111(1–2):31–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong X, Ao Y, Faas GC, Nwaobi SE, Xu J, Haustein MD, Anderson MA, Mody I, Olsen ML, Sofroniew MV, Khakh BS, 2014. Astrocyte Kir4.1 ion channel deficits contribute to neuronal dysfunction in Huntington’s disease model mice. Nat Neurosci. 17(5):694–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vit JP, Ohara PT, Bhargava A, Kelley K, Jasmin L, 2008. Silencing the Kir4.1 potassium channel subunit in satellite glial cells of the rat trigeminal ganglion results in pain-like behavior in the absence of nerve injury. J Neurosci. 28(16):4161–4171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wangemann P, 2002. K+ cycling and the endocochlear potential. Hearing Research. 165(1–2):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodhoo A, Sommer L, 2008. Development of the Schwann cell lineage: from the neural crest to the myelinated nerve. Glia. 56(14):1481–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing Y, Samuvel DJ, Stevens SM, Dubno JR, Schulte BA, Lang H, 2012. Age-related changes of myelin basic protein in mouse and human auditory nerve. PLoS One. 7(4):e34500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasoba T, Kondo K, Miyajima C, Suzuki M, 2003. Changes in cell proliferation in rat and guinea pig cochlea after aminoglycoside-induced damage. Neurosci Lett. 347(3):171–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng QY, Johnson KR, Erway LC, 1999. Assessment of hearing in 80 inbred strains of mice by ABR threshold analyses. Hear Res. 130(1–2):94–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.