SUMMARY

Lentiviruses are among the most promising viral vectors for in vivo gene delivery. To overcome the risk of insertional mutagenesis, integrase-deficient lentiviral vectors (IDLVs) have been developed. We show here that strong and persistent specific cytotoxic T cell (CTL) responses are induced by IDLVs, which persist several months after a single injection. These responses were associated with the induction of mild and transient maturation of dendritic cells (DCs) and with the production of low levels of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines. They were independent of the IFN-I, TLR/MyD88, IRF, RIG-I and STING pathways but require NF-κB signaling in CD11c+ DCs. Despite the lack of integration of IDLVs, the transgene persists during three months in the spleen and liver of IDLV-injected mice. These results demonstrate that the capacity of IDLVs to trigger persistent adaptive responses is mediated by a weak and transient innate response, along with the persistence of the vector in tissues.

INTRODUCTION

An ideal vaccine has to deliver the antigen to professional antigen presenting cells (APCs) in the context of appropriate costimulation and cytokine stimulus in order to induce potent primary and memory immune responses. In particular, dendritic cells (DCs) must efficiently capture the antigen and receive maturation signals. Indeed, while immature DCs induce T cell tolerance, the presence of costimulating signals and inflammatory cytokines results in the potent induction of immunity (Bonifaz et al., 2002) (Probst et al., 2003).

Several viral vectors, such as adenoviruses, adeno-associated viruses and lentiviral vectors (LVs) (Nayak and Herzog, 2010), have been used to deliver antigens to DCs, generating efficient immune responses against pathogens and tumors. LVs are a subclass of retroviral vectors derived from the human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1). They have been developed in order to generate self-inactivating vectors, without pathogenic or replicative capacity, while maintaining their ability to transfer and integrate into the host genome (Zufferey et al., 1998).

Compared to other gene delivery technologies, LVs possess major advantages. Indeed, their immunogenicity can be decreased by the deletion of selected genes, and there is usually no pre-existing immunity against LVs (Sakuma et al., 2012) (Vigna and Naldini, 2000). In vitro, both murine and human DCs can be transduced with LVs with efficiencies of 30 to 90% (Esslinger et al., 2002) (Chinnasamy et al., 2000) for the activation of CD8+ T cells (Esslinger et al., 2002) (He et al., 2005). LVs thus represent a very attractive platform for in vivo gene delivery, either for vaccination (Beignon et al., 2009) or to correct genetic defects (Aiuti et al., 2013; Biffi et al., 2013). Gamma-retroviral vectors have been successfully used to treat children with X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency (Hacein-Bey-Abina et al., 2003). However, acute leukemia developed in four of these patients, demonstrating that the main drawback of these vectors is the risk of insertional mutagenesis (Hacein-Bey-Abina et al., 2010). Conversely, to date, there has only been a single case of insertion dependent clonal expansion in lentiviral transduction in gene therapy cases despite hundreds of gene therapy patients (Cartier et al., 2009).

To develop safer LV-derived vectors, integrase-deficient LVs (IDLVs) have been recently generated through the use of mutations in the integrase protein that minimize proviral integration (Sakuma et al., 2012) (Philippe et al., 2006) (Vargas et al., 2004). Several reports have demonstrated that nonintegrative IDLVs induce strong immune responses that can be used in protective immunization against infectious diseases and for tumor immunotherapy (Negri et al., 2007) (Karwacz et al., 2009) (Grasso et al., 2013).

The mechanisms by which LVs induce these strong adaptive immune responses remain controversial. Indeed, the maturation of DCs is regulated by various signals that are sensed by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) including Toll-like receptors (TLRs), retinoic acid induced gene (RIG)-I-like receptors (RLRs), DNA sensors, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptors (NLRs) and C-type lectin receptors (CLRs) (Gurtler and Bowie, 2013) (Fritz et al., 2006) (Geijtenbeek and Gringhuis, 2009). HIV-1 has a single-stranded positive RNA (ssRNA) genome (Sakuma et al., 2012) that can be directly detected in the cytosol by the RIG-I receptor or by TLR7 in the endocytic compartment (Pichlmair et al., 2006) (Diebold et al., 2004). In addition, ssRNA can also be converted by RNA polymerase III into double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), which is a natural ligand of TLR3 (Alexopoulou et al., 2001). This mechanism is involved in the innate sensing of LVs by DCs (Breckpot et al., 2010). Furthermore, in vitro studies have suggested that the type I IFN (IFN-I) response to HIV-1 is due to the activation of TLR7 on plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) by the viral ssRNA genome (Beignon et al., 2005). Thus, LVs can directly activate pDCs through the engagement of TLR7/9 leading to IFN-α production, which in turn promotes the bystander maturation of myeloid DCs (Rossetti et al., 2011). Furthermore, by-products present in the vector preparation, such as tubulovesicular structures containing nucleic acids, can stimulate TLR9, leading to the production of IFN-I by pDCs (Pichlmair et al., 2007). dsDNA generated after reverse transcription of the viral genome by the viral reverse transcriptase (Sakuma et al., 2012), could be detected by cytosolic DNA sensors that act upstream of STING (Gurtler and Bowie, 2013). As a result, LV proviral DNA could trigger both TLR and non-TLR mediated pathways (Agudo et al., 2012). Very recently, Kim et al. demonstrated that the induction of efficient immune responses by LVs is mediated by DC activation following the pseudotransduction of LV particles in a phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)-dependent process and by the cellular DNA package from LV preparation through a STING and cGAS pathway (Kim et al., 2017).

In the present study, using IDLVs expressing ovalbumin (IDLV-OVA) as a model antigen, we confirmed that IDLVs can induce strong cytotoxic T cell (CTL) responses, which persist several months after a single injection in the absence of an adjuvant. These strong responses were associated with the in vivo induction of mild and transient maturation of both conventional DCs (cDCs) and pDCs and with the production of low levels of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Only cDCs were required for the induction of CTL responses by IDLVs. This induction was independent of the main signaling pathways that can be potentially activated by IDLVs, i.e., TLR/MyD88, IRF, RIG-I and STING, but were fully dependent upon NF-κB signaling in CD11c+ cells. In addition, we demonstrated that, despite their lack of integration, IDLV-OVA persisted in the spleen and the liver of vaccinated mice up to 3 months after vaccination via intravenous injection. This study thus demonstrates that potent adaptive immune responses can be triggered by IDLVs in the absence of marked and prolonged inflammatory responses, suggesting that the long-lasting CTL responses induced by IDLVs may be associated with the persistence of the transgene.

RESULTS

IDLV-OVA induces strong and persistent CTL responses

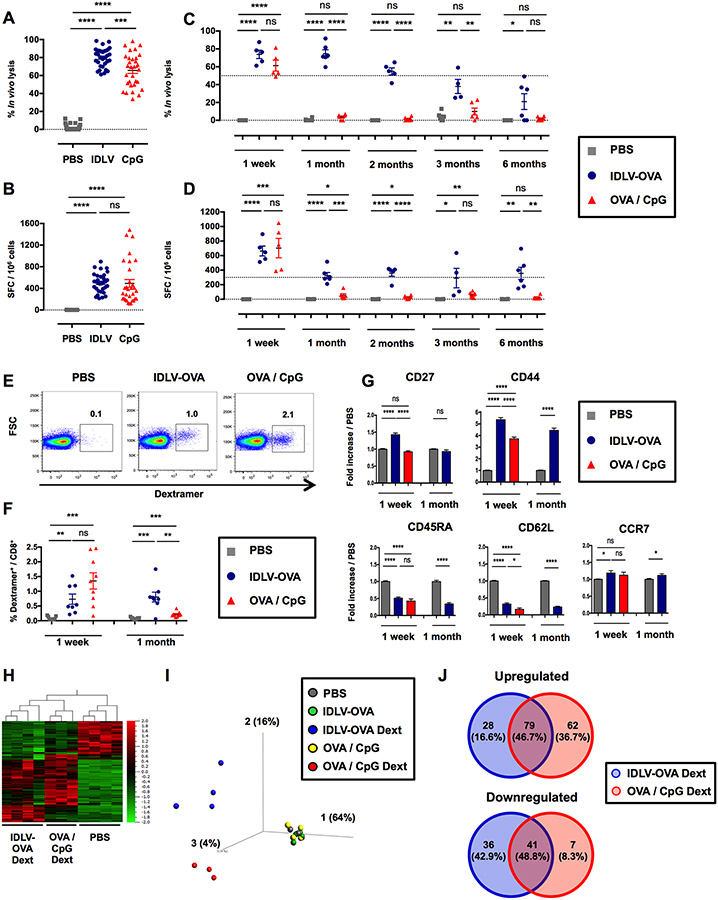

To analyze the CTL responses induced by IDLV-OVA, various doses of this recombinant IDLV were intravenously injected into C57BL/6 mice for comparison with OVA with CpG-B, a potent adjuvant used to induce CTL responses. The in vivo lysis as well as the number of IFN-γ-producing cells were analyzed one week later (Fig. S1A–B). Strong CTL responses were detectable, even after the injection of a low dose of the vaccine. The optimal dose of 106 transduction units (TUs) of IDLV-OVA was selected since this dose induced a high CTL response in all mice. In contrast, at 0.5×106 TUs and below, some mice were not responding in the IFN-γ ELISPOT assay. Following immunization with the optimal dose of 106 TUs, CTL responses were still detectable up to 6 months after vaccination (Fig. 1A–D). In contrast, the OVA-specific CTL response induced by OVA/CpG peaked at one week and then declined very rapidly. The ability of IDLV-OVA to prevent the growth of B16-OVA was then evaluated. C57BL/6 mice were immunized with IDLV-OVA and 6 months later were grafted with B16-OVA tumor cells. As compared to control mice, the survival of IDLV-OVA immunized mice was significantly improved and 2 out of 6 mice remained tumor-free until the end of the experiment (Fig. S1C–D). These data demonstrate that the persistent CTL responses induced by IDLV-OVA provided a long-lasting protective anti-tumor immunity. The phenotype of OVA-specific CD8+ T cells was analyzed by FACS on H-2Kb/SIINFEKL-Dextramer+ cells at one week and one month after immunization (Fig. 1E–G). One week after immunization, IDLV-OVA primed a lower frequency of OVA-specific dextramer+ cells (0.73% of total CD8+ T cells) compared to OVA/CpG (1.35% of the total CD8+ T cells) (Fig. 1E–F). However, the OVA-specific dextramer+ cells were still detectable one month after vaccination with IDLV-OVA in contrast to mice immunized with OVA/CpG (Fig. 1F). One week after vaccination, OVA-specific CD8+ T cells induced by IDLV-OVA expressed a classical effector CTL phenotype (Wherry and Ahmed, 2004) (CD27high CD44high CD45RAlow CD62Llow CCR7low), similar to the OVA-specific CD8+ T cells induced by OVA/CpG (Fig. 1G). However, the expression of CD27 and CD44 was significantly upregulated in CTL cells induced by IDLV-OVA, compared to OVA/CpG. One month after immunization, OVA-specific CD8+ T cells induced by IDLV-OVA expressed an effector-memory T cell phenotype (CD27low CD44high CD45RAlow CD62Llow CCR7low) (Fig. 1G). These results suggest that IDLV induced a more persistent CTL response compared to OVA/CpG.

Figure 1. IDLV-OVA induces sustained and persistent CTL responses.

C57BL/6 mice were injected i.v. with PBS, 106 TUs IDLV-OVA or OVA/CpG. (A-B) Seven days later, anti-OVA CTL responses were assessed by an in vivo killing assay (A) and IFN-γ ELISPOT (B). (C-D) The persistence of the anti-OVA CTL responses was assessed by an in vivo killing assay (C) and IFN-γ ELISPOT (D) up to 6 months after immunization. (A-D) The results are expressed as the percentage of specific lysis for the in vivo killing assay (A, C) and IFN-γ spot-forming cells (SFC) per 106 splenocytes for ELISPOT (B, D). Each dot represents an individual mouse. The results represent the means ± SEM of cumulative data from 33 mice from eleven independent experiments (A, B) or from 6 mice from two independent experiments (C, D). (E-G) Seven days and one month later, the OVA-specific CD8+ T cell response was analyzed by H-2Kb/SIINFEKL-Dextramer staining. The gating strategy for CD3+ CD8+ CD4− dextramer positive cells 1 week after immunization is shown in (E). (F) The percentage of CD3+ CD8+ dextramer+ cells among the total CD8+ cells is shown at 1 week and 1 month after immunization. The results represent the means ± SEM of cumulative data from 8 to 9 mice from three independent experiments. (G) Expression of CD27, CD44, CD45RA, CD62L and CCR7 by CD3+ CD8+ dextramer+ cells. The results are expressed as the fold-increase in the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) ± SEM compared to PBS-injected mice and represent the cumulative data from 8 to 9 mice from three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed by unpaired Student’s t-test (ns p > 0.05, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001). (H, I, J) Seven days later, splenic CD8+ T cells were purified from PBS, IDLV-OVA and OVA/CpG treated mice, whereas OVA-specific CD8+ T cells (H-2Kb/SIINFEKL-Dextramer+ CD8+) were purified from IDLV-OVA and OVA/CpG immunized mice. RNA was extracted, and the expression of genes involved in the immune response was assessed with the nCounter Mouse Pan Cancer Immune Profiling Panel. (H) Heat Map of genes significantly and differentially expressed by OVA-specific CD8+ T cells purified from IDLV-OVA or OVA/CpG immunized mice (IDLV-OVA Dext and OVA/CpG Dext, respectively) compared to CD8+ T cells purified from PBS-injected mice (PBS). (I) PCA (Principal Component Analysis) of genes significantly and differentially expressed by OVA-specific CD8+ T cells purified from IDLV-OVA or OVA/CpG immunized mice (IDLV-OVA Dext and OVA/CpG Dext, respectively) compared to CD8+ T cells purified from mice injected with PBS (PBS) or IDLV-OVA (IDLV-OVA) or OVA/CpG (OVA/CpG). (J) Venn diagrams of upregulated (left panel) and downregulated (right panel) genes differentially expressed by IDLV-OVA Dext or OVA/CpG Dext. The results represent the cumulative data from 4 to 5 mice from five independent experiments. See also Figures S1 and S2.

OVA-specific CD8+ T cells induced by IDLV-OVA display a specific transcriptomic signature

We next compared the transcriptomic profile of OVA-specific CD8+ T cells purified from the spleens of mice injected one week before with IDLV-OVA or OVA/CpG (Fig. S2A). The expression of 800 genes was compared using the Nanostring technology. The hierarchical Heat Map clustering analysis (Fig. 1H) and PCA (Fig. 1I) showed that OVA-specific CD8+ T cells induced by IDLV-OVA or OVA/CpG exhibited different gene expression profiles. To characterize more precisely the differences between the two treatments, we identified genes that were differentially up or downregulated in OVA-specific CD8+ T cells purified from immunized mice compared to CD8+ T cells purified from PBS-injected mice. Only 79 genes (46.7% of total upregulated genes) and 41 genes (48.8% of total downregulated genes) of the upregulated or downregulated genes, respectively, were shared by OVA-specific CD8+ T cells after immunization with IDLV-OVA or OVA/CpG, demonstrating that these CTL populations possess distinct gene expression profiles.

Among the 107 genes upregulated and the 77 genes downregulated in OVA-specific CD8+ T cells from mice immunized with IDLV-OVA (Fig. 1J), 14 genes were significantly upregulated, whereas 9 genes were significantly downregulated compared to CpG/OVA (Fig. S2B). While the significantly upregulated genes are involved in the activation of T lymphocytes (Klrkl) (Jamieson et al., 2002), the downregulated genes are involved in T cell exhaustion (Havcr2, Lag3, Tigit) (Wherry and Kurachi, 2015), apoptosis (Casp3) (Porter and Janicke, 1999) and the activation of T lymphocytes (Tnfrsf4) (Watts, 2005). These results suggest that the activation of OVA-specific CTL cells by OVA/CpG is followed by the exhaustion and apoptosis of CD8+ T cells, whereas the CTL cells induced by IDLV-OVA could be less activated and thus less prone to apoptosis, which could be correlated with the persistence of the CTL responses induced by IDLV-OVA. Thus, we then analyzed the expression of T cell exhaustion markers by OVA-specific CD8+ T cells. One week after immunization with IDLV-OVA or CpG/OVA, the expression of PD-1, CD153 (CD30-Ligand), CD223 (Lag3) and CD366 (Tim3) was analyzed by flow cytometry (Fig. S2C). The expression of PD-1 and CD223 was significantly upregulated following immunization with IDLV-OVA or CpG/OVA, while the level of CD366 was strongly downregulated. However, no statistical difference was observed between specific CD8+ T cells induced either by IDLV-OVA or CpG/OVA immunization, suggesting that these markers were not involved in the exhaustion of CD8+ T cell responses induced by CpG/OVA.

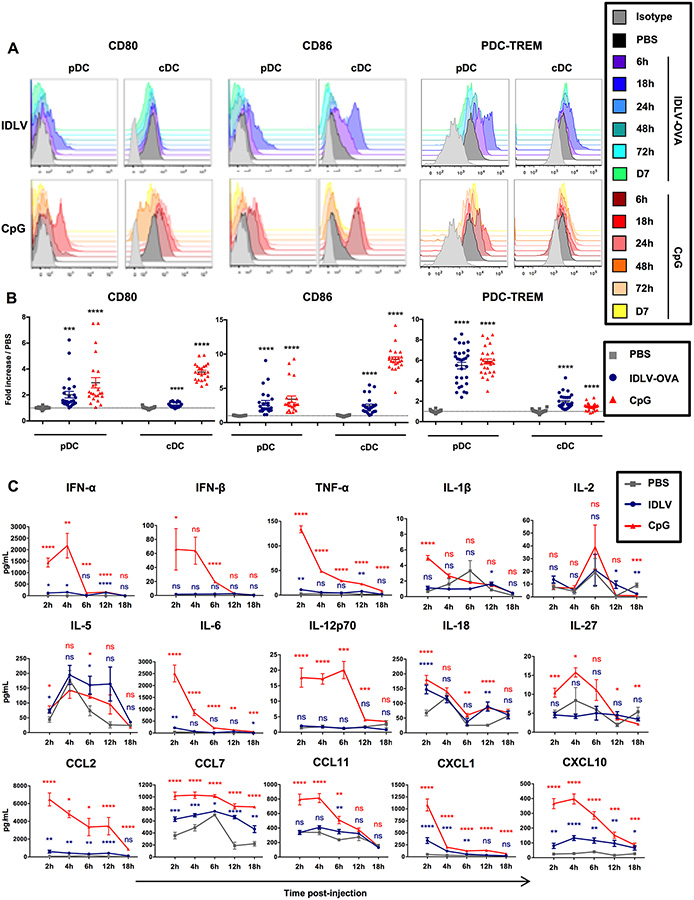

IDLVs induce a mild and transient maturation of mouse DCs

To understand the mechanisms responsible for the different gene expression profiles of the CD8+ T cells induced either by IDLV-OVA or OVA/CpG, we next analyzed the innate responses induced by IDLV-OVA compared to CpG. Various doses of IDLVs were injected into mice, and we analyzed the expression by CD11chighB220− cDCs and CD11clowB220+CD317+Siglec-H+ pDCs (Fig. S3A–B)of various activation markers and costimulatory molecules, as well as of molecules involved in the regulation of immune responses. After the injection of 5×106 TUs IDLV-OVA, a significant but transient increase in the expression of CD80, CD86 and PDC-TREM by cDCs and pDCs was observed, which peaked 18 hours after administration, whereas no significant effect was observed following the injection of lower doses (Fig. S1B and Fig. 2A–B). A significant increase in the expression of CD40, CD54, CD69, H-2Kb, I-Ab, ICOS-L, OX40-L and PDL1 (Fig. S3C–F) was also observed.

Figure 2. IDLVs induce a mild and transient maturation of mouse DCs.

C57BL/6 mice were injected i.v. with PBS, 5×106 TUs IDLV-OVA or CpG. (A-B) The maturation of pDCs (left panels) and cDCs (right panels) was assessed from 6 hours to 7 days after injection by monitoring the expression of CD80, CD86 and PDC-TREM by flow cytometry. The results are represented as histograms from one representative experiment (A) or expressed as the fold increase in MFI ± SEM compared to pDCs or cDCs from PBS-injected mice eighteen hours after injection. The results represent the cumulative data from 25 to 30 mice from nine independent experiments (B). (C) The production of cytokines and chemokines in the sera of C57BL/6 mice injected with PBS, IDLV-OVA or CpG was assessed up to eighteen hours after injection by Luminex MagPIX technology. The results are expressed in pg ml−1 and represent the cumulative data from 22 mice from six independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed by unpaired Student’s t-test in comparison with the PBS-treated mice (ns p > 0.05, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001). The statistical analysis in red corresponds to the statistics for CpG and in blue, to the statistics for IDLV-OVA compared to PBS-treated mice. See also Figure S3.

These results show that IDLV-OVA induces the maturation of both pDCs and cDCs. However, for some markers, this maturation was significantly less marked than in the CpG-treated mice. However, this was not true for CD80 (pDCs), CD86 (pDCs), I-Ab (pDCs), H-2Kb (cDCs), OX40-L and PDC-TREM (pDCs). Furthermore, this was observed only after 5×106 TUs, but not after the administration of lower doses, which were capable of promoting the induction of strong CTL responses.

We then analyzed the cytokines and chemokines produced in the sera of vaccinated mice using a Luminex assay (Fig. S3G). The administration of CpG induced the production of high levels of most of the cytokines and chemokines tested (Fig. 2C). The induction of IFN-I, IL-2 and IL-12p70 were correlated with the expansion of highly cytolytic, terminally differentiated, short-lived effector CD8+ T cells (Cox et al., 2013). In contrast, IDLV-OVA treatment induced only the production of significant concentrations of IL-5 and IL-18, both of which were required for an optimal CTL response (Cox et al., 2013) (Apostolopoulos et al., 2000).

Altogether, these data show that strong and persistent CTL responses induced by IDLV-OVA, are associated with a mild DC activation and a low and transient inflammation.

Conventional DCs are required for the induction of CTL responses by IDLV-OVA

Since both pDCs and cDCs were activated by IDLV-OVA, we analyzed their respective roles in the induction of CTL responses using BDCA2-DTR (Swiecki et al., 2010) and CD11c-DTR (Jung et al., 2002) transgenic mice, which express the human diphtheria toxin receptor (DTR) under the control of BDCA2, a pDC-specific promoter, or the CD11c promoter, respectively. Since nonhematopoietic cells may also express the CD11c-DTR transgene (Jung et al., 2002), we produced chimeric mice (CD11c-DTR → WT) in which only the hematopoietic compartment is derived from CD11c-DTR mice. Administration of DT to BDCA2-DTR mice resulted in the depletion of pDCs, without affecting cDCs (Fig. S4A–B). The treatment of CD11c-DTR → WT chimeric mice with DT induced the depletion of CD11c+ cells, i.e., cDCs and macrophages, but did not affect pDCs (Fig. S4C–G). This finding was consistent with the results of a previous study (Hervas-Stubbs et al., 2014). The administration of DT to BDCA2-DTR mice had a low impact on the CTL responses (Fig. 3A) or on the maturation of cDCs (Fig. 3B–C and Fig. S5) induced by IDLV-OVA but strongly reduced the adaptive and innate responses induced by OVA/CpG. In contrast, the administration of DT to CD11c-DTR → WT chimeric mice fully abolished the CTL responses induced by IDLV-OVA (Fig. 3D) and strongly reduced the maturation of pDCs (Fig. 3E–F and Fig. S5). The depletion of cDCs by DT treatment also suppressed the CTL responses induced by OVA/CpG vaccination (Fig. 3D), but did not affect the maturation of pDCs induced by the CpG (Fig. 3E–F and Fig. S5). Altogether, these results show that cDCs are strictly required for the induction of CTL responses by IDLV-OVA, whereas pDCs do not play a significant role.

Figure 3. Conventional DCs are mandatory for the induction of CTL responses by IDLV-OVA.

PBS and DT treated-BDCA2-DTR (A-C) and -CD11c-DTR → C57BL/6 chimeric mice (DF) were injected i.v. with PBS, 106 (A, D) or 5×106 TUs IDLV-OVA (B, C, E, F) or OVA/CpG (A, D) or CpG (B, C, E, F). Seven days later, anti-OVA CTL responses were assessed by in vivo killing and IFN-γ ELISPOT assays (A, D). The results are expressed as the percentage of specific lysis for CTL activity and IFN-γ SFC per 106 splenocytes for ELISPOT. Each dot represents an individual mouse. The results represent the means ± SEM of cumulative data from 6 to 8 mice collected from three independent experiments (A) or 3 to 5 mice from two independent experiments (D). Eighteen hours after injection, the expression of CD40, CD86 or PDC-TREM by cDCs (B, C) and pDCs (E, F) was assessed by flow cytometry. The results are represented as histograms from one representative experiment (B, E) or expressed as the fold-increase in MFI ± SEM compared to pDCs or cDCs from PBS-injected mice (C, F). They represent the cumulative data from 4 to 6 mice (C) or 2 to 5 mice from two independent experiments (F). Statistical analysis was performed by unpaired Student’s t-test in comparison with the PBS-treated mice or between PBS and DT treated-mice, as indicated by the horizontals bars (ns p > 0.05, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001). See also Figures S4 and S5.

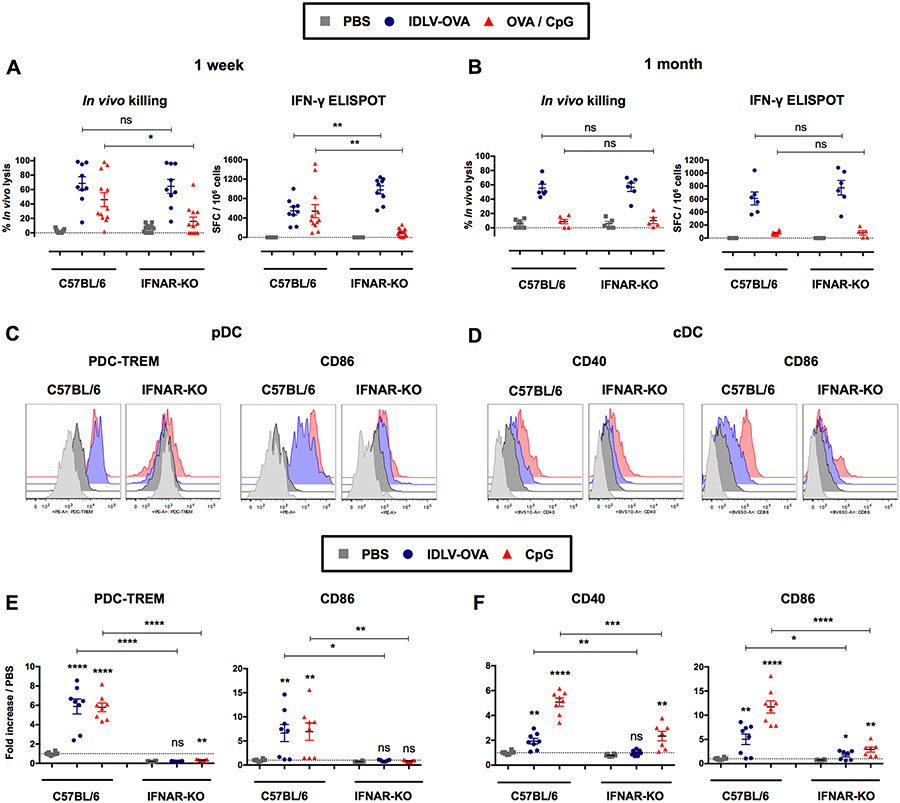

The induction of immune responses by IDLVs is independent upon IFN signaling

IFN-I play a major role in the induction of CTL responses (Hervas-Stubbs et al., 2007). We therefore analyzed the CTL responses induced by IDLV-OVA in IFNAR-KO mice, which are deficient in IFN-I receptors, compared to C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 4A–B). The lack of IFN-I signaling did not affect the induction of these responses either at one week (Fig. 4A) or one month after immunization by IDLV-OVA (Fig. 4B). In contrast, the CTL responses induced by OVA/CpG were strongly decreased in IFNAR-KO mice, in agreement with our previous results (Hervas-Stubbs et al., 2007).

Figure 4. The induction of CTL responses by IDLV-OVA does not require IFN-I signaling.

C57BL/6 and IFNAR-KO mice were injected i.v. with PBS, 106 TUs (A-B) or 5×106 TUs (C-F) IDLV-OVA or OVA/CpG (A-B) or CpG (C-F). Seven days (A) and one month (B) later, anti-OVA CTL responses were assessed by in vivo killing assay and IFN-γ ELISPOT. The results are expressed as the percentage of specific lysis for in vivo killing assay and IFN-γ SFC per 106 splenocytes for ELISPOT. Each dot represents an individual mouse. The results represent the means ± SEM of cumulative data from 9 to 12 mice from five independent experiments (A) or 5 to 6 mice from two independent experiments (B). Eighteen hours after injection, the expression of CD40, CD86 or PDC-TREM by pDCs (C, E) and cDCs (D, F) was assessed by flow cytometry. The results are represented as histograms from one representative experiment (C, D) or expressed as the fold-increases in MFI ± SEM compared to pDCs or cDCs from PBS-injected mice (E, F). They represent the cumulative data from 6 to 8 mice from three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed by unpaired Student’s t-test in comparison with the PBS-treated mice or between C57BL/6 and IFNAR-KO mice, as indicated by the horizontals bars (ns p > 0.05, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001). See also Figure S6.

Whereas the CTL responses induced by IDLV-OVA were not affected in IFNAR-KO mice, the maturation of cDCs and pDCs was strongly decreased in these mice (Fig. 4C–F and Fig. S6). A similar drastic reduction in DC maturation was observed in mice injected with CpG. These results demonstrate that the CTL responses induced by IDLVs are independent of IFNI signaling and can be generated in the absence of the efficient maturation of cDCs.

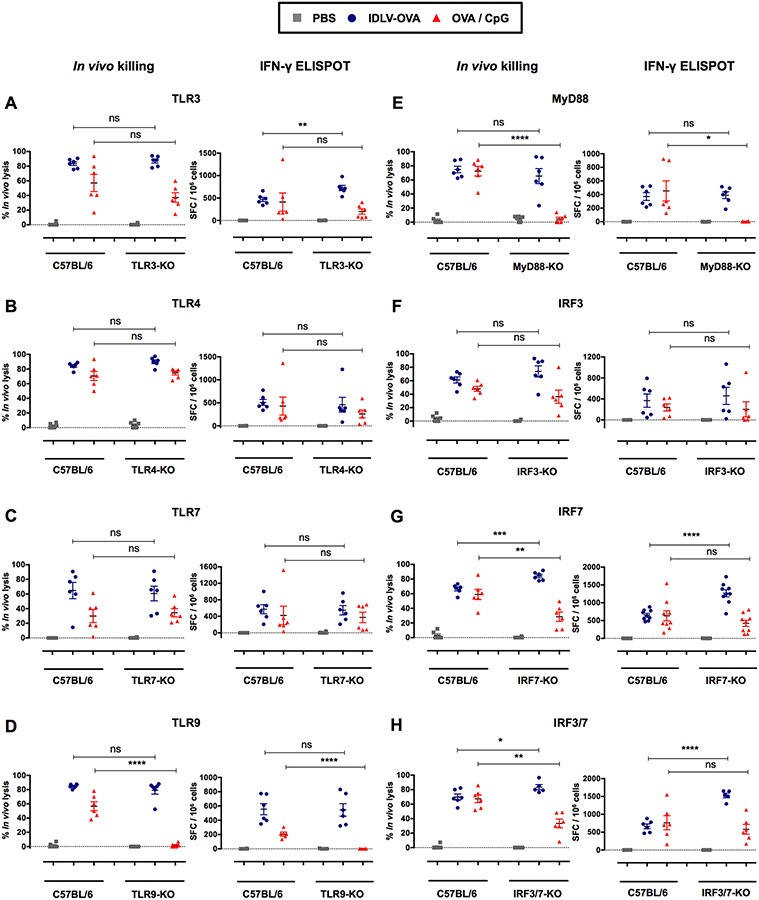

The induction of CTL responses by IDLV-OVA is independent of the TLR3, 4, 7, 9, MyD88, IRF3, and IRF7 pathways

IDLVs were produced in human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells through the transfection of three vector plasmids as previously described (Rossi et al., 2014). The culture supernatant contained the lentiviral particles of interest, as well as cell debris and plasmid contaminants possibly able to activate TLR3, TLR7 or TLR9 (Alexopoulou et al., 2001; Beignon et al., 2005; Breckpot et al., 2010; Diebold et al., 2004; Pichlmair et al., 2007; Rossetti et al., 2011). Upon recognition of their respective PAMPs (Pathogen Associated Molecular Patterns), TLRs recruit adaptor molecules that harbor the TIR (Toll/Interleukin Receptor) domain, such as TRIF and MyD88 which are utilized by all TLRs with the exception of TLR3 (Kawai and Akira, 2010). These adaptors initiate signal cascades leading to the activation of interferon regulatory factors 3 and 7 (IRF3 and IRF7) (Thompson et al., 2011). We thus analyzed the CTL responses induced by IDLV-OVA in TLR-KO, MyD88-KO and single and double IRF3 and IRF7-KO mice, in comparison with C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 5). As expected, the absence of TLR9 or MyD88, but not of TLR3 or 7, fully abolished the CTL response induced by OVA/CpG (Hemmi et al., 2000). These responses analyzed by in vivo killing assay were also significantly reduced in IRF7- or IRF3/7-KO mice. In contrast, the OVA-specific CTL responses induced by IDLV-OVA and tested either by the in vivo killing assay or by ELISPOT were not decreased between the TLR3, TLR4, TLR7, TLR9, MyD88, IRF3, IRF7 and IRF3/7-KO mice and the C57BL/6 wild type mice (Fig. 5A–H) showing that the induction of CTL responses by IDLV-OVA is fully independent of TLR/MyD88 and IRF signaling. However, a significant increase in these responses was observed in the IRF7 and IRF3/7-KO mice, suggesting a negative regulatory role of IRF7 on the induction of immune responses by IDLVs.

Figure 5. The induction of CTL responses by IDLV-OVA is independent of the TLR3, 4, 7, 9, MyD88, IRF3, and IRF7 pathways.

C57BL/6, TLR3−/− (A), TLR4−/− (B), TLR7−/− (C), TLR9−/− (D), MyD88−/− (E), IRF3−/− (F), IRF7−/− (G) and IRF3/7−/− (H) mice were immunized i.v. with PBS, 106 TUs IDLV-OVA or OVA/CpG. Seven days later, anti-OVA CTL responses were assessed by in vivo killing assays (left panels) and IFN-γ ELISPOT assays (right panels). The results are expressed as the percentage of specific lysis for the in vivo killing assay and as the IFN-γ SFC per 106 splenocytes for ELISPOT. Each dot represents an individual mouse. The results represent the means ± SEM of cumulative data from 5 to 9 mice from two to three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed by an unpaired Student’s t-test in comparison with control C57BL/6 mice (ns p > 0.05, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001).

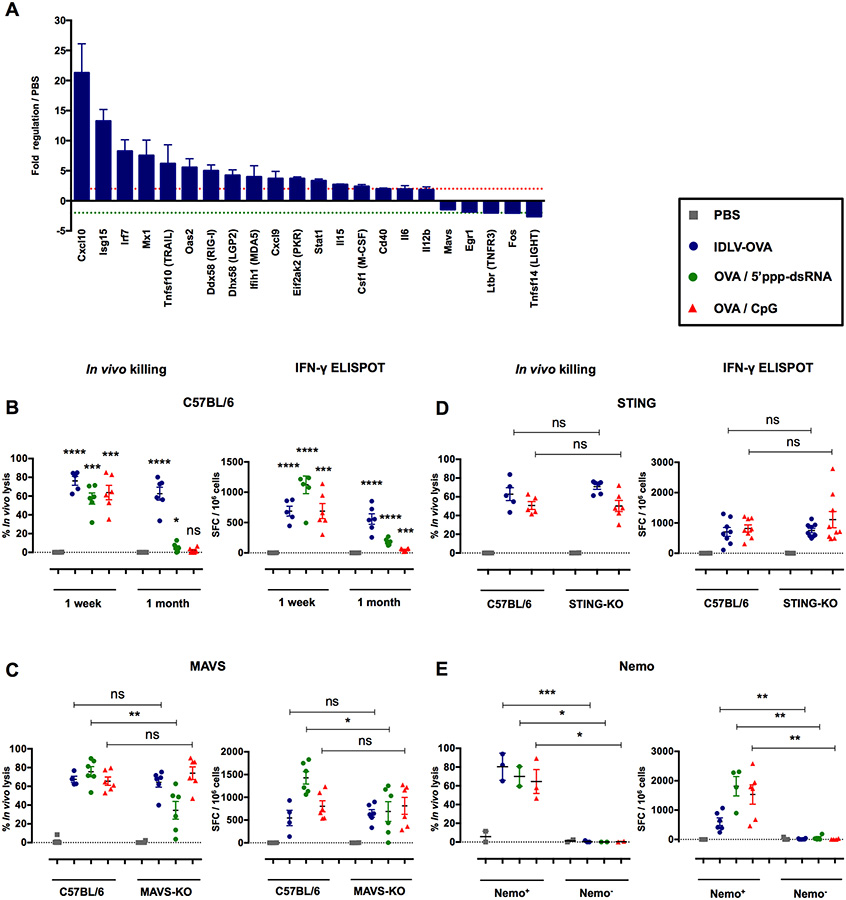

The induction of CTL responses by IDLV-OVA is independent of the RIG-I and STING pathways but dependent on NF-κB signaling

Our results clearly show that cDCs are mandatory for the induction of CTL responses by IDLVs, but that TLR signaling is not involved in this process. To characterize the DC pathways activated by IDLVs, we analyzed the expression of 142 genes related to antiviral responses and NF-κB signaling in splenic cDCs purified from mice injected with IDLVs (Fig. S7A–B). Our results show that IDLVs induced a network of antiviral genes (Fig. 6A). Four viral RNA pattern recognition genes were upregulated, of which RLRs such as RIG-I, LGP-2 and MDA-5 increased by 5-, 4.2- and 4-fold, respectively. PKR, an enzyme activated by dsRNA, was upregulated 3.7-fold, reflecting the presence of viral RNA in the cytoplasm. The expression of two IFN signaling genes, IRF7 and STAT1, also increased by 8.3-and 3.3-fold, respectively. Three antiviral IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs), Isg15, Mx1 and Oas2, were upregulated by 13.3-, 7.5-and 5.6-fold respectively, as well as the genes mediating antiviral immunity such as the Cxcl10 gene, which increased by 21.3-fold. Thus, after sensing IDLV, DCs activate IFN signaling and antiviral response.

Figure 6. The induction of CTL responses by IDLV-OVA is RIG-I and STING-independent, but depends upon the NF-κB pathway.

(A) C57BL/6 mice were injected i.v. with PBS or 5×106 TUs IDLV-GFP. Four hours after injection, CD11c+ splenic cells were sorted, and the pathways involved in antiviral responses and NF-κB signaling were analyzed using the RT2 profiler PCR array. The results are expressed as the means ± SEM of fold regulation compared to PBS-injected mice, and represent the cumulative data from two mice from two independent experiments. The green dashed line represents a threshold of two-fold downregulation and the red dashed line represents a threshold of two-fold upregulation. C57BL/6 (B), MAVS−/− (C), STING−/− (D) and CD11c-Cre × Nemo flox (E) mice were injected i.v. with PBS, 106 TUs IDLV-OVA, OVA/5’ppp-dsRNA or OVA/CpG. Seven days (B-E) or one month (B) later, anti-OVA CTL responses were assessed by an in vivo killing assay (left panels) and IFN-γ ELISPOT (right panels). The results are expressed as the percentage of specific lysis for the in vivo killing assay and IFN-γ SFC per 106 splenocytes for ELISPOT. Each dot represents an individual mouse. The results represent the means ± SEM of cumulative data from 3 to 9 mice from two to three independent experiments (B-D) or 2 to 6 mice from two independent experiments (E). Nemo+ mice were born from the crossing of CD11c-Cre littermate non transgenic mice × Nemo flox mice. In contrast, Nemo− mice were born from the crossing of CD11c-Cre transgenic mice × Nemo flox mice. Statistical analysis was performed by unpaired Student’s t-test in comparison with PBS-treated mice or between control and deficient mice, as indicated by the horizontal bars (ns p > 0.05, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001). See also Figures S7, S8 and S9.

These results suggest that IDLVs, presumably through the ssRNA genome (Sakuma et al., 2012), activate the RIG-I pathway. Recently, 5’-triphosphate RNA (5’ppp-dsRNA) was demonstrated to be a selective ligand for RIG-I with the ability to induce strong cytotoxic T cell responses (Hornung et al., 2006) (Hochheiser et al., 2016). We thus compared the CTL responses induced by OVA in the presence of this RIG-I ligand and IDLV-OVA. One week after immunization, strong CTL responses were observed in mice immunized by IDLV-OVA or by OVA in the presence of either 5’ppp-dsRNA or CpG, confirming the potent adjuvant property of this RIG-I ligand (Fig. 6B). However, one month after immunization, these CTL responses vanished in the mice that received OVA with 5’ppp-dsRNA, whereas they persisted in mice immunized with IDLV-OVA. This observation strongly suggests that the activation of the RIG-I pathway was not responsible for the persistence of these responses. To confirm this conclusion, we next analyzed the CTL responses induced by IDLV-OVA in mice deficient in MAVS, the common adaptor of RIG-I or MDA5 (Seth et al., 2005), in comparison with C57BL/6 mice. As expected, the CTL responses induced by OVA in the presence of 5’ppp-dsRNA were strongly reduced in MAVS-KO mice, whereas they were not affected in mice immunized by IDLV-OVA or OVA/CpG (Fig. 6C), confirming the lack of contribution of the RIG-I pathway in their induction. It was recently shown that the STING/cGAS pathway is activated through genomic DNA encapsulated into LV virion preparation (Kim et al., 2017). However, strong CTL responses were induced by IDLV-OVA in STING-KO mice (Fig. 6D), demonstrating the lack of involvement of STING signaling in the induction of CTL responses by our IDLV preparations. Finally, to investigate the role of NF-κB in the induction of CTL responses by IDLV-OVA, we used Nemo flox transgenic mice with loxP sites, which were crossed with CD11c-Cre transgenic mice, resulting in the deletion of Nemo in CD11c+ cells.

Indeed, Nemo is a protein necessary for the activation of NF-κB signaling (Israel, 2010) whereas CD11c+ DCs are mandatory for the induction of CTL responses by IDLV-OVA. As shown in Fig. 6E, the absence of Nemo in CD11c+ cells fully abolished the capacity of IDLV-OVA, OVA/CpG and OVA/5’ppp-dsRNA to stimulate CTL responses, clearly demonstrating that the induction of these responses is fully dependent on NF-κB signaling.

To further characterize the NF-κB pathway involved in the induction of CD8+ T cell responses by IDLV, we then performed a transcriptomic analysis of more than 750 genes expressed by cDCs following immunization with IDLV-OVA or CpG/OVA (Fig. S8 and S9)using the Nanostring technology. The hierarchical Heat Map clustering analysis showed that cDCs from IDLV-OVA immunized mice exhibited a low transcriptional gene modulation compared to cDCs from CpG/OVA immunized mice (Fig. S8A), confirming that IDLV induce a mild innate response. The analysis of the genes that were significantly induced or inhibited by cDCs from IDLV-OVA immunized mice compared to PBS injected mice (Fig. S8B), confirmed that cDCs were activated in mice immunized by IDLV-OVA, inducing the upregulation of antiviral genes. Furthermore, the analysis of the expression of cytokines and cytokine receptor genes (Fig. S9A) confirmed that IDLV induced a weak cytokine production as already shown by the quantification of cytokines/chemokines in the sera of immunized mice. These results also suggest that DCs could be the cells responsible for the production of IL-18, but not of IL-5.This analysis also showed that TRAF2/6 and RelA/B were up-regulated in mice immunized with IDLV-OVA (Fig. S9B), strongly suggesting that IDLV activates the canonical NF-κB/Rel pathway. Furthermore, the downregulation of IL-1β and the upregulation of TNF suggest that the activation of the NK-kB/Rel pathway could be linked to TNF signaling.

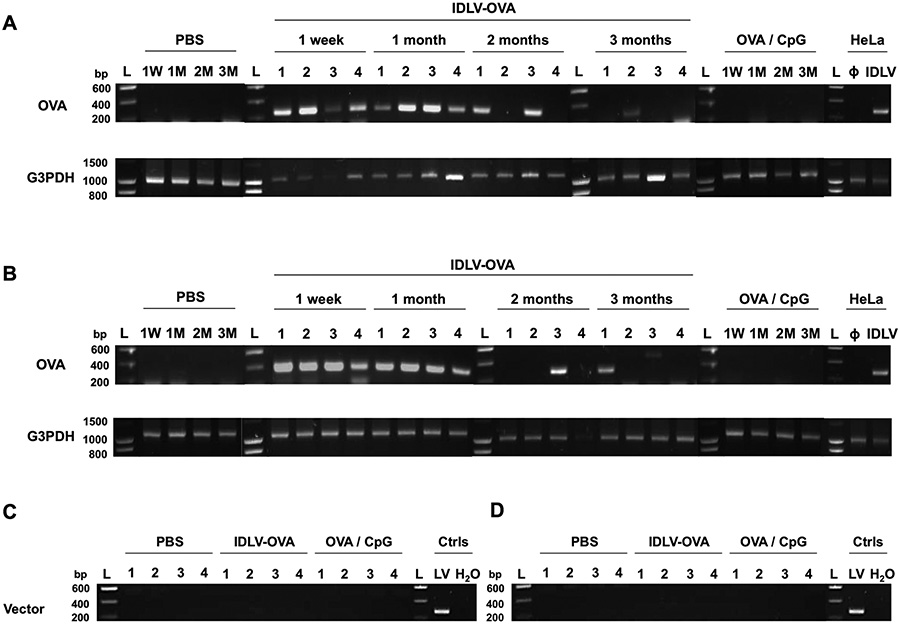

The long-lasting CTL responses induced by IDLV-OVA are correlated with the persistence of the transgene in the spleen and the liver of immunized mice

These results do not identify a specific activation pathway involved in the induction of the CD8+ T cell response by IDLV-OVA that could explain the persistence of the CTL response induced by this vector. We thus tested whether this persistence could be due to a prolonged antigen expression in immunized mice. C57BL/6 mice were injected with IDLV-OVA, and the presence of the transgene was evaluated by PCR in the spleen (Fig. 7A) and liver (Fig. 7B) tissues of the vaccinated mice up to 3 months after injection. All DNA samples were subjected to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (G3PDH) amplification to control for the DNA integrity (Fig. 7A–B bottom panels). The OVA transgene was still detectable in the spleen and/or the liver of all immunized mice one month after vaccination and in 50% of vaccinated mice up to 3 months after injection (after 2 months: 2/4 in spleen (lanes 1 and 3), and 1/4 in liver (lane 3) and after 3 months: 1/4 in spleen (lane 2) and 1/4 in liver (lane 1)) (Fig. 7A–B top panels).

Figure 7. The long-term persistence of the CTL responses induced by IDLV-OVA correlates with the persistence of the transgene in the spleen and the liver of vaccinated mice.

C57BL/6 mice were injected i.v. with PBS, 106 TUs IDLV-OVA or OVA/CpG. (A-B) One week or one, two or three months later, spleens (A) and livers (B) were harvested. DNA was extracted and amplified using the corresponding primer pair. At each time point, 4 mice were included for the IDLV-OVA treatment, whereas one mouse per time point is shown for the PBS and OVA/CpG groups. The presence of the OVA transgene (top panels) and the G3PDH (DNA integrity, bottom panels) was evaluated by PCR. (C-D) One month after injection, spleens (C) and livers (D) were harvested, and DNA was extracted and amplified using the corresponding primer pair to evaluate vector integration. At each time point, 4 mice were included per treatment. The positive and negative controls used to detect the presence of the OVA transgene were subjected to DNA extraction from HeLa cells, transduced or not (Φ) with IDLV-OVA (IDLV). G3PDH: glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; L: ladder; Ctrls: controls performed on DNA extracted from B16F10 cells infected with the integrase competent lentiviral vector (LV) expressing OVA and with a PCR performed with H2O.

The long-term persistence of the transgene in immunized mice cannot be due to the integration of the vector, since we did not find any evidence of its integration (Fig. 7C–D) one month after the injection of IDLV-OVA. This was in contrast to the DNA extracted from B16F10 cells infected with the integrase competent LV expressing OVA, which was used as a positive control of vector integration.

These data demonstrate that despite the lack of integration, IDLV-OVA persists in the spleen and the liver of immunized mice, suggesting a long-term expression of the OVA antigen, which could be responsible for the persistence of the CTL responses.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we evaluated the mechanisms underlying the strong effector memory cytotoxic T cell response, which persists up to 6 months after a single immunization with an integrase-deficient lentiviral vector without adjuvant. The induction of these responses is fully dependent on cDCs, although IDLVs induce mild and transient innate responses, characterized by low levels of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines and weak DC maturation. The activation of efficient immune responses by IDLVs does not require the IFN-I, TLR/MyD88, IRF, RIG-I and STING pathways but is fully dependent upon NF-κB signaling in CD11c+ cells. Moreover, we demonstrate that despite their lack of integration, IDLV-OVA persists up to 3 months in the spleen and the liver of intravenously vaccinated mice, in correlation with their capacity to induce long-lasting immune responses and protective antitumoral immunity.

We first analyzed whether the capacity of IDLVs to induce strong CTL responses is due to the stimulation of sustained innate responses, leading to DC activation and to the production of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines. Indeed, both cDCs and pDCs were activated following immunization by IDLVs, although cDCs were the only DCs required for the induction of CD8+ T cell responses. However, compared to CpG/OVA, IDLVs induced a mild and transient activation of cDCs, which was detectable only after the administration of high doses of IDLV-OVA. Interestingly, lower doses of IDLV-OVA were still capable of promoting the induction of strong CTL responses, but could not induce a detectable maturation of DCs. Thus, the magnitude and the duration of CTL responses induced by IDLV-OVA, compared to CpG/OVA, were not correlated with the level of innate responses induced by these vaccines. Remarkably, IDLVs in contrast to CpG induced a very low level of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. It has been shown that IFN-I and/or IL-12 are required for the expansion of highly cytolytic effector CD8+ T cells. Indeed, T cells exposed to high levels of IL-2 preferentially attain a terminally differentiated, short-lived effector phenotype. By contrast, the restriction of inflammatory conditions surrounding CD8+ T cells allows the formation of long-lived memory populations (Cox et al., 2013). These data are in agreement with our observations that CpG, which induces the secretion of IFN-I and IL-12p70, allows the expansion of short-lived effector CD8+ T cells, while the lack of production of IFN-I and IL-12p70 and the low secretion of IL-2 following IDLV-OVA immunization correlate with the induction of long-lasting CD8+ T cell responses. Upon IDLV-OVA treatment, only IL-5 and IL-18 were detectable. These cytokines have been shown to be required for an optimal CTL response and are associated with IFN-γ production by effector and memory CD8+ T cells (Apostolopoulos et al., 2000) (Cox et al., 2013), strongly suggesting that IL-5 and IL-18 are implicated in the induction of cytotoxic responses by IDLVs.

One week after vaccination, OVA-specific CD8+ T cells induced by IDLV-OVA expressed a classical effector CTL phenotype (Wherry and Ahmed, 2004), similar to the OVA-specific CD8+ T cells induced by OVA/CpG. However, the expression of CD27 and CD44 were significantly more upregulated in CTL cells induced by IDLV-OVA than after immunization with OVA/CpG. The engagement of CD27 promotes the development of CTL effectors and the survival of TCR-activated T cells (Hendriks et al., 2003). It also regulates their expansion at the site of priming, maintenance at the effector site, contraction, memory formation, and secondary expansion. A major mechanism by which CD27 affects the T cell response is their protection from apoptosis. The analysis of gene expression showed that OVA-specific CD8+ T cells induced by IDLV-OVA downregulate genes involved in apoptosis (Casp3) (Porter and Janicke, 1999) and in T cell exhaustion (Havcr2, Lag3, Tigit) (Wherry and Kurachi, 2015) compared to OVA/CpG. In addition, several genes involved in the activation of T lymphocytes were downregulated (Tnfrsf4) (Watts, 2005), although others were upregulated (Klrkl) (Jamieson et al., 2002). Thus, it could be suggested that the strong activation of cytotoxic T cells by OVA/CpG is followed by the rapid exhaustion of CD8+ T cells and apoptosis. In contrast, CD8+ T cells induced by IDLV-OVA could be less activated, eventually due to the low innate responses induced by this vector compared to CpG. They are therefore less prone to cell death and exhaustion, leading to a longer survival.

IFN-I was shown to be important in the induction of CD8+ T cell responses, as confirmed previously for CpG/OVA (Hervas-Stubbs et al., 2014). In contrast, the present study demonstrates that the effector and memory T cell responses induced by IDLVs are totally independent of IFN-I signaling. However, cDC activation and maturation induced by IDLV-OVA were strongly reduced in the absence of IFN-I signaling. These results confirm that efficient CTL responses could be induced by IDLV-OVA, even with the low maturation of cDCs.

HIV-1 possesses a ssRNA genome (Sakuma et al., 2012) which could be directly detected into the cytosol by the RIG-I receptor or by TLR7 in the endocytic compartment (Pichlmair et al., 2006) (Diebold et al., 2004). Through the action of the viral reverse transcriptase or RNA polymerase III, ssRNA is converted into dsDNA or dsRNA, which could be detected respectively into the cells by cytosolic DNA sensors that act upstream of STING (Gurtler and Bowie, 2013) or by TLR3 (Alexopoulou et al., 2001). In addition, tubovesicular structures containing nucleic acids present in the vector preparation could also stimulate TLR9 (Pichlmair et al., 2007). Several studies have shown the involvement of both TLR (TLR3, 7, 9) and non-TLR mediated mechanisms involving LV proviral DNA in the sensing of LVs (Beignon et al., 2005) (Breckpot et al., 2010) (Rossetti et al., 2011) (Agudo et al., 2012). NF-κB signaling could be engaged by IDLV-OVA, as the activation of RLR signaling leads to its activation (Nan et al., 2014). Moreover, NF-κB could also be activated by the dsRNA-dependent PKR (Gil et al., 2000), which is upregulated upon IDLV treatment. In agreement with these hypotheses, the absence of Nemo in CD11c+ cells fully abolished the capacity of IDLV-OVA to stimulate CTL responses, clearly demonstrating that the induction of these responses was fully dependent upon NF-κB signaling in dendritic cells. In agreement with these findings, the transcriptomic analysis of genes expressed by cDCs after immunization with IDLV-OVA demonstrated that IDLV activated the canonical NK-kB/Rel pathway. Altogether, these data suggest the presence of IDLV RNA in the cytoplasm of immunized mice, which could be detected by either RIG-I or PKR leading to NF-κB activation. However, mice deficient in TLR/MyD88, IRF, RIG-I or MDA5 were fully capable of developing strong CTL responses after IDLV-OVA immunization. These results suggest that IDLVs are not recognized by these sensors. Alternatively, it could be proposed that IDLVs can signal through several of these pathways, which could compensate for an absence in one of them.

In agreement with our results, it was recently shown that the activation of DCs by LVs is independent of MyD88, TRIF, and MAVS, ruling out the involvement of TLR or RLR signaling. However, this study also concluded that two different pathways could contribute to the in vitro activation of mouse BMDCs and human monocytic DCs by LVs (Kim et al., 2017). LVs could induce cell activation either following envelope-mediated viral fusion in a phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)-dependent process or by the cellular DNA packaged in these LV preparations, which stimulates the STING/cGAS pathway. However, the requirement of each of these processes in the in vivo activation of DCs was not clearly established. Indeed, while CD8+ T cell responses induced by LVs were reduced in mice deficient for STING and cGAS, the activation of the DCs of these immunized mice was not analyzed. In contrast to this study, our present data clearly show that IDLVs induce efficient CTL responses in STING-deficient mice, compared to C57BL/6 mice, thus demonstrating that STING is not involved in the induction of CD8+ T cell responses by IDLV-OVA. The discrepancy of our results with Kim’s study (Kim et al., 2017) could be explained by the mode of IDLV preparation or by the route of immunization used. In Kim’s study, the STING/cGAS pathway was activated not by the virion itself but by the human genomic DNA packaged during the preparation of LVs. This contaminant human DNA could thus play an important role in the induction of immune responses by the LVs used in that study.

Finally, we demonstrate that despite the lack of integration of IDLV-OVA, the OVA transgene was detectable in the spleen and the liver of vaccinated mice up to 3 months after a single intravenous injection. Interestingly, it was previously demonstrated that IDLVs could be detected at the injection site up to 3 months after intramuscular administration (Negri et al., 2007) (Karwacz et al., 2009). Altogether, these data suggest that the antigen can be expressed during several months after immunization, which could explain how high frequencies of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells are maintained following immunization with lentivirus (He et al., 2005) (Kimura et al., 2007). The expression of the transgene delivered by IDLVs persists in transduced human macrophages but is rapidly lost in dividing cells (Gillim-Ross et al., 2005). Macrophages are long-lived cells (Takahashi, 2001) and thus can stimulate naive CD8+ T cells to proliferate and differentiate into memory T cells (Pozzi et al., 2005). Recent studies have shown that DCs retain their dividing abilities and could maintain the expression of antigens in their progeny directly through successive cell divisions (Diao et al., 2007).

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that a single immunization with low doses of IDLVs induce strong CTL responses which were fully dependent upon NF-κB signaling in CD11c+ DCs. Despite their lack of integration, the transgene persists in the spleen and the liver of vaccinated mice, leading to a long lasting memory CTL response associated with protective antitumor immunity. Thus, we identify the persistence of the vector as an important parameter for the induction of efficient adaptive immune responses. In addition, our study also shows that sustained inflammatory responses are not required for the optimal induction of the immune response. This study highlights the improved safety and efficacy of IDLVs and provides important features to be considered for the development of new vaccine strategies.

STAR Methods

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Claude Leclerc (claude.leclerc@pasteur.fr).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

In vivo animal studies

Female C57BL/6/J (BL/6) mice were obtained from Charles River. CD11c-Diphtheria Toxin (DT) receptor (DTR) (B6.FVB-Tg(Itgax-DTR/GFP)57Lan/J) (Jung et al., 2002), CD11c-Cre (B6.Cg-Tg(Itgax-cre)1–1Reiz/J) (Caton et al., 2007) transgenic mice, MAVS-deficient (B6;129-Mavstm1Zjc/J) (Sun et al., 2006) and STING-deficient (C57BL/6J-Tmem173<gt>/J) (Sauer et al., 2011) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Except MAVS-deficient mice, which were a mix of C57BL/6 and 129/Sv strain, these mice were all on the C57BL/6 background. TLR3- (Alexopoulou et al., 2001), 4- (Hoshino et al., 1999), 7- (Hemmi et al., 2002), 9- (Hemmi et al., 2000), MyD88- (Kawai et al., 1999), IFN receptor 1- (IFNAR) (Muller et al., 1994), IRF3- (Sato et al., 2000), IRF7- (Honda et al., 2005) and IRF3/7-deficient mice, Nemo flox (Ikbkgtm1.1Mpa [flox]) (Schmidt-Supprian et al., 2000) and BDCA2-DTR (C57BL/6- Tg(CLEC4C-HBEGF)956Cln/J) (Swiecki et al., 2010) transgenic mice were on the C57BL/6 background. All strains were bred in Pasteur Institute facilities under specific and opportunistic pathogen-free conditions (SOPF). All experiments were performed under SPF conditions after acclimation of at least 8 days. Animal studies were approved by the CETEA ethics committee number 89 (Institut Pasteur, Paris, France) and by the French Ministry of Research (MESR 00355.02).

For in vivo animal studies, 6 to 12 weeks old female C57BL/6 mice were used as control mice for experiments using deficient mice (MAVS-, STING-, TLR3-, TLR4-, TLR7-, TLR9-, MyD88-, IFNAR-, IRF3-, IRF7- and IRF3/7-deficient mice). These deficient mice were 6 to 12 old weeks, male or female, according to their availability in the animal facilities.

To generate CD11c-DTR → C57BL/6 bone marrow (BM) chimeric mice, 5 weeks old female C57BL/6 mice were irradiated with a single lethal dose of 6 grays, which were then reconstituted with 5 × 106 BM cells from CD11c-DTR mice. BM chimeric mice were kept on antibiotic-supplemented drinking water for 10 days and used 8 weeks after reconstitution. Littermates PBS-treated of the same age and sex were randomly assigned to experimental groups which were DT-treated. The same experimental procedure was used for BDCA2-DTR mice. For the depletion of cDCs or pDCs, CD11c-DTR → C57BL/6 BM chimeric mice or BDCA2- DTR mice, were respectively injected i.p. with 5.2 ng DT (Calbiochem, Merck distributor, Fontenay sous Bois, France) per gramme 1 day before immunization and then every 2 days.

To generate mice with a conditional depletion of the NF-κB pathway in CD11c+ cells, CD11c-Cre transgenic mice were first crossed to obtain homozygous transgenic mice and littermate non transgenic mice. Then, these mice were crossed with the Nemo flox mice. At each generation, offspring were genotyped using PCR for CD11c-Cre and for Nemo flox. A first generation of females (F1) was obtained from a Nemo flox+ male crossed with homozygous CD11c-Cre transgenic female mice. The F1 females were then crossed with a Nemo flox+ male and F2 offpsrings with flox+ and Cre+ crossed between them. The offspring obtained from this last crossing (F3; Nemo−) were finally used for immunization. Control mice (Nemo+) obtained from a male CD11c-Cre littermate crossed with Nemo flox female mice were also immunized.

For tumor challenge, female C57BL/6 mice (6–8 weeks old) purchased from Charles River were kept in pathogen-free condition in the animal facilities at the Istituto Superiore di Sanità (ISS, Rome, Italy) and treated according to European Union guidelines and Italian legislation (Decreto Legislativo 26/2014). All animal studies were authorized by the Italian Ministry of Healthy and reviewed by the Service for Animal Welfare at ISS (Authorization n. 314/2015-PR of 30/04/2015). All animals were euthanized by CO2 inhalation using approved chambers, and efforts were made to minimize suffering and discomfort. Twenty-six weeks after immunization with 6×106 TUs IDLV-OVA or with IDLV expressing an unrelated antigen, mice were injected subcutaneously with 2×105 B16-OVA and the tumor growth was followed. Mice developing tumor larger than 15 mm or showing ulceration were sacrificed.

Cell lines

The cell lines used in this work were HeLa (ATCC, Manassas, VA), B16F10 and B16-OVA cells (obtained from Dr. Louis Sigal, University of Masachusetts, Worcester, MA 01655).

Indeed, to generate positive and negative controls to detect (1) the presence of the OVA transgene and (2) the integration of the vector, we extracted DNA (1) from HeLa cells, transduced or not with IDLV-OVA and (2) from B16F10 transduced with integrase-competent LV expressing the ovalbumin (LV-OVA). For that, (1) 105 HeLa adherent cells / well in complete DMEM medium (ATCC) were plated in 6-well plates. The day after, cells were transduced overnight with 1 mL of complete medium containing 1 MOI IDLV-OVA. DNA from HeLa cells transduced with IDLV and non-transduced (φ) HeLa cells were extracted on day 3 using the SV Total RNA Isolation System protocol, modified for DNA preparation as previously described (Rossi et al., 2014); (2) 105 B16F10 adherent cells in complete DMEM medium were plated in 6-well plates. The day after, cells were transduced overnight with 1 mL of complete medium containing 1 MOI LV-OVA. DNA from the transduced B16F10 cells was extracted at 2 weeks after transduction using the mi-Tissue Genomic DNA Isolation Kit (Metabion International AG, Martinsried, Germany).

For tumor challenge, B16-OVA tumor cells, which are B16 melanoma cells transfected with OVA antigen were kindly provided by L. Rosthein and L. Sigal (University of Massachusetts, Worcester, MA). They were cultured in complete medium supplemented with 2 mg/mL geneticin G418 (Life Technologies) and 60 μg/mL hygromycin B (Roche).

METHOD DETAILS

Reagents

The reagents used for vaccination were the following: the synthetic peptide OVA257–264 (SIINFEKL), corresponding to the H-2Kb restricted CTL epitope of ovalbumin (OVA), was purchased from NeoMPS (Strasbourg, France). The OVA protein was obtained from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). Unmethylated cytosine-guanine class B (CpG-B) motifs (TLR9 ligand-CpG-B 1826 5’-TCC ATG ACG TTC CTG ACG TT-3’) were synthetized by Sigma Aldrich (St Quentin Fallavier, France) and DOTAP Liposomal Transfection Reagent was purchased from Roche (Sigma Aldrich distributor, St Quentin Fallavier, France). 5’ppp-dsRNA was purchased from Invivogen (Toulouse, France) and the in vivo nucleic acid delivery in vivo-jetPEI was acquired from Polyplus transfection (Illkirch, France).

Lentiviral vector production

Integrase-Deficient Lenviral Vectors (IDLVs) expressing the coding sequence for ovalbumin (see next paragraph) (IDLV-OVA) or GFP (IDLV-GFP) were generated and tittered as previously described (Rossi et al., 2014). These doses are expressed as transduction units (TUs) corresponding to the number of functional viral particles in a solution that are capable of transducing a cell and expressing the transgene.

Coding sequence of the OVA protein

ATGgggctccatcggcgcagcaagcatggaattttgttttgatgtattcaaggagctcaaagtccaccatgccaatgagaacatcttctactgccccattgccatcatgtcagctctagccatggtatacctgggtgcaaaagacagcaccaggacacagataaataaggttgttcgctttgataaacttccaggattcggagacagtattgaagctcagtgtggcacatctgtaaacgttcactcttcacttagagacatcctcaaccaaatcaccaaaccaaatgatgtttattcgttcagccttgccagtagactttatgctgaagagagatacccaatcctgccagaatacttgcagtgtgtgaaggaactgtatagaggaggcttggaacctatcaactttcaaacagctgcagatcaagccagagagctcatcaattcctgggtagaaagtcagacaaatggaattatcagaaatgtccttcagccaagctccgtggattctcaaactgcaatggttctggttaatgccattgtcttcaaaggactgtgggagaaaacatttaaggatgaagacacacaagcaatgcctttcagagtgactgagcaagaaagcaaacctgtgcagatgatgtaccagattggtttatttagagtggcatcaatggcttctgagaaaatgaagatcctggagcttccatttgccagtgggacaatgagcatgttggtgctgttgcctgatgaagtctcaggccttgagcagcttgagagtataatcaactttgaaaaactgactgaatggaccagttctaatgttatggaagagaggaagatcaaagtgtacttacctcgcatgaagatggaggaaaaatacaacctcacatctgtcttaatggctatgggcattactgacgtgtttagctcttcagccaatctgtctggcatctcctcagcagagagcctgaagatatctcaagctgtccatgcagcacatgcagaaatcaatgaagcaggcagagaggtggtagggtcagcagaggctggagtggatgctgcaagcgtctctgaagaatttagggctgaccatccattcctcttctgtatcaagcacatcgcaaccaacgccgttctcttctttggcagatgtgtttcccctctagatgcatgctcgagcggccgccagtgtgatggatatctgcagaattcggctttgataatcaacctctggattacaaaatttgtgaaagatTGA

Flow cytometry analysis

Spleen cells were washed, incubated with a Fc block, and stained with various mAbs. Cells were then washed and acquired using an LSR Fortessa cytometer (BD Biosciences, Rungis, France) and analyzed with FlowJo Software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

For all flow cytometry analysis, fluorochrome-labeled Abs against murine cell surface Ags were from BD Biosciences (Le Pont de Claix, France), BioLegend (Ozyme distributor, Saint Quentin en Yvelines, France) and eBioscience (ThermoFisher Scientific, France). The Fc block is a mAb against mouse FcR produced by BioXCell (West Lebanon, NH).

To characterize DC subsets, the following mix of antibodies were used: one pre-mix with anti-CD11c/PE-Cy7 (N418), anti-CD317/APC (eBio927), anti-B220/PerCP-Cy5.5 (RA3–6B2), anti-CD11b/APC-eF780 (M1/70) and anti-CD8a/eF450 (53–6.7) mAbs as well as mix1 composed of anti-PDC-TREM/PE (4A6), anti-ICOS-L/Biotin (HK5.3) followed by an additional incubation with streptavidin-BV500 and anti-CD69/BV786 (H1.2F3); mix2 composed of anti-CD80/BV650 (16–10A1), anti-OX40-L/Biotin (RM134L) followed by an additional incubation with streptavidin-BV500 and anti-H-2Kb/PE (AF6–88-5); mix3 composed of anti-CD86/BV650 (GL1), anti-PDL1/Biotin (M1H5) followed by an additional incubation with streptavidin-BV500 and anti-I-Ab/PE (AF6–120.1) and mix4 composed of anti-CD40/Biotin (3/23), streptavidin-BV500 and anti-CD54/PE (YN1/1.7.4).

To control DC depletion, spleen cells were stained with a first mix for macrophages and DC: anti-CD8a/eF450, anti-CD317/APC, anti-CD11c/PE-Cy7, anti-B220/PerCP-eF710, anti-Siglec-H/PE (440c), anti-CD11b/APC-eF780 and anti-F4/80/Biotin (BM8) mAbs followed by an additional incubation with streptavidin-BV500 and a second mix for NK cells: anti-CD3/eF450 (145–2C1), anti-CD19/PE-Cy7 (1D3), anti-CD27/PE (LG.7F9), anti-NK1.1/APC (PK-136) and anti-CD11b/APC-eF780.

To characterize the OVA-specific CD8+ T cell phenotype, spleens were removed seven days and one month after immunization. 3×106 cells were washed, incubated for 10 min at RT with 10 μL of H- 2Kb/SIINFEKL-Dextramer (Immudex, Copenhagen, Denmark) followed by an additional incubation of 20 min at 4°C with Fc block, anti-CD3/APC-eF780 (17A2), anti-CD4/BUV737 (RM4–5), anti-CD8a/BUV395 (53–6.7), anti-CD27/PerCP-eF710 (LG.7F9), anti-CD44/APC (IM7), anti-CD45RA/BV650 (14.8), anti-CD62L/PE-Cy7 (MEL-14) and anti-CCR7/eF450 (4B12) mAbs (Fig. 1G) or anti-CD3/FITC (17A2), anti-CD4/eF450 (GK1.5), anti-CD8a/PE (53–6.7), anti-PD-1/BV786 (J43), anti-CD152/PE-Cy7 (UC10–4B9), anti-CD223/BV650 (C9B7W) and anti-CD336/PerCP-Cy5.5 (RMT3–23) mAbs (Fig. S2C). Cells were then washed, filtered and acquired using an LSR Fortessa cytometer and analyzed with FlowJo Software.

Analysis of cytokine and chemokine production

Cytokine and chemokine concentration in the mouse sera was assessed with Luminex MagPIX technology using the ProcartaPlex mouse cytokine/chemokine 26Plex immunoassay kit from eBioscience (eBioscience, Paris, France). IFN-α and IFN-β concentrations were determined using the ProcartaPlex Mouse IFN-α and IFN-β 2Plex Assay from eBioscience.

In vivo killing assay

Mice were injected i.v. with PBS, 106 TUs IDLV-OVA, 100 μg OVA with 25 μg 5’ppp-dsRNA and 4 μL in vivo-jetPEI, or 100 μg OVA with 30 μg CpG-B 1826 plus 60 μg DOTAP. The percentage of specific lysis was assessed by an in vivo killing assay as previously described (Hervas-Stubbs et al., 2007). Naive syngeneic splenocytes were pulsed with the OVA257–264 peptide (1 ng/ml) and labeled with a high concentration (2.5 μM) of CFSE (Molecular Probes, Fisher Scientific distributor, Illkirch, France). The non-pulsed control population was labeled with a low concentration (0.25 μM) of CFSE. CFSEhigh- and CFSElow-labeled cells were mixed in a 1:1 ratio and injected i.v. into the mice 6 days after the immunization. The number of CFSE-positive cells remaining in the spleen after 19 hours was determined by flow cytometry, and the percentage of specific lysis was calculated as follows: % specific lysis = 100 - [100 × (%CFSEhigh immunized mice/%CFSElow immunized mice) / (%CFSEhigh naive mouse/%CFSElow naive mouse)].

IFN-γ ELISPOT assay

Mice were injected i.v. with PBS, 106 TUs IDLV-OVA, 100 μg OVA with 25 μg 5’ppp-dsRNA and 4 μL in vivo-jetPEI, or 100 μg OVA with 30 μg CpG-B 1826 plus 60 μg DOTAP. The frequency of OVA257–264-specific IFN-γ-producing cells was determined by an enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay, as previously described (Schlecht et al., 2004). Ninety-six-well Multiscreen-HA sterile plates (Millipore, Molsheim, France) were coated with purified anti-IFN-γ mAbs (Murine IFN-γ ELISpot Pair from Diaclone). Plates were washed and blocked with complete culture medium for 2 hours before adding the cells. Various numbers of splenocytes from immunized and control mice were then added (2 to 4 × 105 per well) in the presence or absence of 10 μg/mL of OVA257–264 peptide. The cells were cultured O/N at 37° C. They were then washed and the biotinylated mAbs were added (Murine IFN-γ ELISpot Pair from Diaclone) in a solution of PBS 1% BSA. One hour and half later, the plates were washed and streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase (AKP) was added to the wells in a solution of PBS 1% BSA. One hour later, the plates were washed and BCIP/NBT (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate/nitro blue tetrazolium substrate; Sigma-Aldrich, 100 μL) was added to each well. Ten minutes later, the revelation was stopped with water. The spots were counted using the automated Bioreader-3000 pro counter (Bioreader, Karben, Germany). For each mouse, the number of peptide-specific IFN-γ-producing cells was determined by calculating the difference between the number of spots generated in the absence and in the presence of the OVA257–264 peptide. Results are expressed as spot-forming cells (SFCs) per number of splenocytes in the wells.

PCR arrays

CD11c+CD3e−B220−CD317− splenic cells from immunized mice were first magnetically sorted with anti-CD11c-Beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Paris, France) and then by FACS ARIA after labeling with anti-CD11c/eF450 (N418), anti-B220/PE (RA3–6B2), anti-CD317/APC (eBio927) and anti-CD3e/FITC (17A2) antibodies. The purity was always > 96.3% of live cells. RNA from purified CD11c+ cells was extracted from cell lysates with the RNeasy Plus microkit (QIAGEN, Courtaboeuf, France). cDNA was generated using a RT2 First Strand Kit and quantified using the RT2 Profiler Mouse antiviral responses and NF-κB signaling pathway PCR arrays (SABiosciences, QIAGEN, Courtaboeuf, France), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The results were analyzed using the SA Biosciences Data Analysis Web Portal (http://pcrdataanalysis.sabiosciences.com/pcr/arrayanalysis.php) and expressed as fold regulation compared to PBS-treated mice.

Genotyping of mice with NEMO-deficient CD11c+ cells

To generate mice with a conditional depletion of the NF-κB pathway in CD11c+ cells, offspring were genotyped using PCR for CD11c-Cre and for Nemo flox at each generation.

DNA was extracted from biopsies of the offpsring obtained after crossing CD11c-Cre mice with Nemo flox mice using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (QIAGEN, Courtaboeuf, France).

Samples were included in PCR analysis to detect the presence of:

CD11c-Cre using a primer pair spanning the transgene (oIMR7841: 5’-ACT TGG CAG CTG TCT CCA AG-3’; oIMR7842: 5’-GCG AAC ATC TTC AGG TTC TG-3’) and an internal positive control (oIMR8744: 5’- CAA ATG TTG CTT GTC TGG TG-3’; oIMR8745: 5’-GTC AGT CGA GTG CAC AGT TT-3’). Reactions were performed with 2 μL of genomic DNA in a 10 μL total volume containing 1× reaction buffer (Invitrogen, Fisher Scientific distributor, Illkirch, France), 2 mM MgCl2 (Invitrogen), 0.2 mM of each dNTP (Roche, Sigma Aldrich distributor, St Quentin Fallavier, France), 1 μM each of the forward and reverse transgene primers, 0.5 μM each of the forward and reverse internal positive control primers and 1 unit of Platinum Taq polymerase (Invitrogen). The PCR conditions were as follows: 1 cycle of 3 min at 94°C, followed by 35 cycles of 30 sec at 94°C, 1 min at 64°C, 1 min at 72°C with a final extension step of 2 min at 72°C in a CFX96 BioRad Thermocycler. PCR products were analyzed by gel electrophoresis on 2% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide. The resulting PCR product sizes were 313 bp for the transgene and 200 bp for the internal positive control.

Flox using the following primers (Nemo 209: 5’- CGT GGA CCT GCT AAA TTG TCT-3’; Nemo 210: 5’- ATC ACC TCT GCA AAT CAC CAG-3’; Nemo 211: 5’- ATG TGC CCA AGA ACC ATC CAG-3’), and reactions were performed with 2 μL of genomic DNA in a 10 μL total volume containing 1× reaction buffer (Invitrogen, Fisher Scientific distributor, Illkirch, France), 2 mM MgCl2 (Invitrogen), 0.2 mM of each dNTP (Roche, Sigma Aldrich distributor, St Quentin Fallavier, France), 0.2 μM each of the primers and 1 unit of Platinum Taq polymerase (Invitrogen). PCR conditions were: 1 cycle of 2 min at 94°C, followed by 30 cycles of 30 sec at 94°C, 30 sec at 60°C, 30 sec at 72°C with a final extension step of 5 min at 72°C in a CFX96 BioRad Thermocycler. PCR products were analyzed by gel electrophoresis on ethidium bromide 2% agarose gel. PCR product sizes were 301 bp for the WT and 446 bp for the flox and 644 bp for the KO.

As the PCR for CD11c-Cre does not distinguish hemizygous from homozygous transgenic animals, a quantitative PCR was performed using primer pairs spanning the transgene (oIMR1084: 5’- GCG GTC TGG CAG TAA AAA CTA TC-3’; oIMR1085: 5’- GTG AAA CAG CAT TGC TGT CAC TT-3’), an internal positive control (oIMR1544: 5’- CAC GTG GGC TCC AGC ATT-3’; oIMR3580: 5’- TCA CCA GTC ATT TCT GCC TTT G −3’) and internal control and transgenic probes (TmoIMR0105: 5’-Cy5- CCA ATG GTC GGG CAC TGC TCA A-BHQ2–3’; 13593: 5’−6-FAM-AAA CAT GCT TCA TCG TCG GTC CGG-BHQ1–3’). Reactions were performed with 20 μg of genomic DNA in a 20 μL total volume containing 1× iTaq (BioRad, Marnes-la-Coquette, France), 0.22 μM each of the forward and reverse transgene primers, 1.1 μM of the forward internal positive control primer, 0.44 μM of the reverse internal positive control primer and 0.16 μM each of the probes. The PCR conditions were: 1 cycle of 3 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 10 sec at 95°C and 1 min at 60°C in a CFX96 BioRad Thermocycler. The transgene genotype was determined by comparing ACt values of each sample.

Transcriptomic analysis

C57BL/6 mice were injected i.v. with PBS, 106 TU IDLV-OVA or OVA/CpG. Seven days later, CD8+ T cells and CD8+ dextramer+ T cells from the spleens of immunized mice were first magnetically sorted using CD8a+ T Cell Isolation Kit, mouse (Miltenyi Biotec, Paris, France) and then by FACS ARIA after labeling with anti-CD3/eF660 (17A2), anti-CD4/eF450 (GK1.5), anti-CD8/PE (53–6.7) and H-2Kb/SIINFEKL-Dextramer. The purity of CD8+ T cells and CD8+ dextramer+ T cells was always > 99.7% and > 95.1% of live cells, respectively.

C57BL/6 mice were injected i.v. with PBS, 5.106 TU IDLV-OVA or OVA/CpG. Eighteen hours later, CD11chigh B220− splenic cells were first magnetically sorted with Pan Dendritic Cell Isolation Kit from Miltenyi Biotec following manufacturer’s instruction and then by FACS ARIA after labelling with anti-CD11c/PE-Cy7 (N418) and anti-B220/PerCP-Cy5.5 (RA3–6B2) fluorescent antibodies. The purity was always > 95.3 % of live cells.

RNA was extracted from cell lysates (30 000 to 250 000 cells) of vaccinated mice with the NucleoSpin RNA XS (Machery-Nagel, Hoerdt, France), and the expression of genes involved in the immune response was assessed using Nanostring technologies with the nCounter Mouse Pan Cancer Immune Profiling Panel, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA quality was evaluated using Agilent RNA 6000 Pico Kit (Agilent technologies, Courtaboeuf, France) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and all samples with RIN values less than 7 were excluded.

For the analysis of genes expressed by OVA-specific CD8+ T cells, the results were analyzed using nSolver Analysis Software 3.0 and Qlucore Omics Explorer 3.0. Normalized data were exported from nSolver Analysis Software 3.0 after a negative control subtraction, positive control normalization and CodeSet content normalization using 5/20 housekeeping genes (Eif2b4, Nubp1, Sap130, Sdha and Sf3a3). Differentially expressed genes were analyzed using Qlucore Omics Explorer 3.0, filtered by a Multi Group Comparison with a q value = 0.05 and using a t-test comparison.

For the analysis of genes expressed by cDCs, normalization on endogenous genes and analysis (Fig. S8) was performed using R package DESeq2 (Love et al., 2014). Default settings of the DESeq2 package were used for the analysis of differentially expressed genes (Wald test followed by Benjamini Hochberg’s adjustment, selection of genes with adjusted p-value < 0.05). The visualization of specific genes (Fig. S9) was performed from normalized data exported from nSolver Analysis Software 3.0 after a negative control subtraction, positive control normalization and CodeSet content normalization using 8/20 housekeeping genes having at least an average count above 100 (Polr2a, Hprt, Gusb, Eef1g, Tubb5, Oaz1, Ppia and Rpl19).

OVA transgene and vector integration analysis

In order to evaluate the presence of the OVA transgene and the integration of the vector, DNA was extracted using the SV Total RNA Isolation System protocol modified for DNA preparation as described previously (Rossi et al., 2014). In brief, 2 important changes in the protocol allow the separate isolation of DNA and RNA, which are the vortexing of the sample during the lysis steps, and the addition of ethanol in two separate steps. When genomic DNA isolation is desired, two vortexing steps facilitate the liberation of genomic DNA from the cell debris so that it can be precipitated by the addition of ethanol. The addition of ethanol in two steps allows for the isolation of DNA after the first ethanol addition, while RNA passes through the SV column. The addition of ethanol to the flowthrough allows the isolation of RNA on a second SV System membrane (Otto P, 1998).

All samples supported the amplification of the mouse glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene (G3PDH using primer pair GlymoFor: 5’-TGA AGG TCG GTG TGA ACG GAT TTG GC-3’; GlymoRev: 5’-CAT GTA GGC CAT GAG GTC CAC CAC-3’). Reactions were performed on 100 ng of genomic DNA in a 25 μL total volume containing 1× reaction buffer (Invitrogen, Fisher Scientific distributor, Illkirch, France), 2 mM MgCl2 (Invitrogen), 0.2 mM of each dNTP (Roche, Sigma Aldrich distributor, St Quentin Fallavier, France), 0.1 μM each of the forward and reverse primers and 1 unit of Platinum Taq polymerase (Invitrogen). The PCR conditions were: 1 cycle of 5 min at 95°C, followed by 35 cycles of 30 sec at 95°C, 30 sec at 60°C, and 30 sec at 72°C with a final extension step of 10 min at 72°C in a CFX96 BioRad Thermocycler. Then, all samples were included in subsequent PCR analysis.

The detection of the presence of the OVA transgene was performed as follow. In the first step of amplification, a primer pair spanning the OVA sequence (OVAnewF1: 5’-TTC AGC CAA GCT CCG TGG ATT C-3’; OVAnewR1: 5’-TCA GGC AAC AGC ACC AAC ATG C-3’) was used, and reactions were performed on 200 ng of genomic DNA in a 50 μL total volume containing 1× reaction buffer (Invitrogen), 2 mM MgCl2 (Invitrogen), 0.4 mM of each dNTP (Roche), 0.4 μM each of the forward and reverse primers and 1 unit of Platinum Taq polymerase (Invitrogen). The PCR conditions were as follows: 1 cycle of 5 min at 94°C, followed by 35 cycles of 30 sec at 94°C, 30 sec at 60°C, 30 sec at 72°C with a final extension step of 10 min at 72°C in a CFX96 BioRad Thermocycler. After the first amplification, a nested PCR was performed on 5 μL of the first PCR product in a 50 μL final volume using the two internal primers in the OVA sequence described above (OVAnewF1/OVAnewR1).

The integrated vector sequence was evaluating using a modified B2-PCR assay (Negri et al., 2007). In the first step of amplification, one primer pair based on the murine B2 family of short interspersed elements (B2AS: 5’-ATA TGT AAG TAC ACT GTA GC-3’) was used with one primer in the central polypurine tract sequence of the vector (cPPT: 5’-TCA GTA CAA ATG GCA GTA TTC ATC C-3’). Reactions were performed on 500 ng of genomic DNA in a total volume of 50 μL containing 1× reaction buffer (Invitrogen), 2 mM MgCl2 (Invitrogen), 0.4 μM of each dNTP (Roche), 0.4 pM each of the forward and reverse primers and 1 unit of Platinum Taq polymerase (Invitrogen). The PCR conditions were as follows: 1 cycle of 1 min at 94°C, followed by 35 cycles of 30 sec at 94°C, 30 sec at 55°C, 15 min at 68°C, with a final extension step of 10 min at 72°C in a CFX96 BioRad Thermocycler. After the first amplification, a nested PCR was performed on 5 μL of the first PCR product in a 50 μL final volume using the two internal primers in the OVA sequence described above (OVAnewF1/OVAnewR1).

All the above PCR products were analyzed by gel electrophoresis on ethidium bromide 1% agarose gel. Sizes of PCR products were 983 bp for the GlymoFor/GlymoRev primer pair and 259 bp for the OVAnewF1/OVAnewR1 primer pair.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

All data were statistically analyzed by an unpaired two-tailed t-test using Prism software (GraphPad). ns, p > 0.05; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001. The results represent the means ± SEM of cumulative data for a given number of mice per group and experiments. These information can be found in the figure legends.

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| anti-mouse CD111c/PE-Cy7 (N418) | eBioscience | Cat#25-0114-82 |

| anti-mouse CD317/APC (eBio927) | eBioscience | Cat#17-3172-82 |

| anti-mouse B220/PerCP-Cy5.5 (RA3-6B2) | eBioscience | Cat#45-0452-82 |

| anti-mouse CD11b/APC-eF780 (M1/70) | eBioscience | Cat#47-0112-82 |

| anti-mouse CD8a/eF450 (53–6.7) | eBioscience | Cat#48-0081-82 |

| anti-mouse PDC-TREM/PE (4A6) | BioLegend | Cat#139204 |

| anti-mouse ICOS-L/Biotin (HK5.3) | eBioscience | Cat#13-5985-85 |

| anti-mouse CD69/BV786 (H1.2F3) | BD | Cat#564683 |

| anti-mouse CD80/BV650 (16–10A1) | BioLegend | Cat#104731 |

| anti-mouse OX40-L/Biotin (RM134L) | eBioscience | Cat#13-5905-85 |

| anti-mouse H-2Kb/PE (AF6-88-5) | eBioscience | Cat#12-5958-82 |

| anti-mouse CD86/BV650 (GL1) | BioLegend | Cat#105035 |

| anti-mouse PDL1/Biotin (M1H5) | eBioscience | Cat#13-5982-85 |

| anti-mouse I-Ab/PE (AF6-120.1) | BD | Cat#553552 |

| anti-mouse CD40/Biotin (3/23) | BD | Cat#553789 |

| anti-mouse CD54/PE (YN1/1.7.4) | eBioscience | Cat#12-0541-81 |

| anti-mouse Siglec-H/PE (440c) | eBioscience | Cat#12-0333-82 |

| anti-mouse F4/80/Biotin (BM8) | Biolegend | Cat#123105 |

| streptavidin-BV500 | BD | Cat#561419 |

| anti-mouse CD3/eF450 (17A2) | eBioscience | Cat#48-0032-82 |

| anti-mouse CD19/PE-Cy7 (1D3) | BD | Cat#561739 |

| anti-mouse CD27/PE (LG.7F9) | eBioscience | Cat#12-0271-82 |

| anti-mouse NK1.1/APC (PK-136) | eBioscience | Cat#17-5941-82 |

| anti-mouse CD3/APC-eF780 (17A2) | eBioscience | Cat#47-0032-82 |

| anti-mouse CD4/BUV737 (RM4-5) | BD | Cat#564933 |

| anti-mouse CD8a/BUV395 (53–6.7) | BD | Cat#563786 |

| anti-mouse CD27/PerCP-eF710 (LG.7F9) | eBioscience | Cat#46-0271-82 |

| anti-mouse CD44/APC (IM7) | eBioscience | Cat#17-0441-82 |

| anti-mouse CD45RA/BV650 (14.8) | BD | Cat#564360 |

| anti-mouse CD62L/PE-Cy7 (MEL-14) | eBioscience | Cat#25-0621-82 |

| anti-mouse CCR7/eF450 (4B12) | eBioscience | Cat#48-1971-82 |

| anti-mouse PD-1/BV786 (J43) | BD | Cat#744548 |

| anti-mouse CD152/PECy7 (UC10-4B9) | Biolegend | Cat#106313 |

| anti-mouse CD223/BV650 (C9B7W) | Biolegend | Cat#125227 |

| anti-mouse CD366/PerCPCy5.5 (RMT3-23) | Biolegend | Cat#119717 |

| anti-mouse CD11c/eF450 (N418) | eBioscience | Cat#48-0114-82 |

| anti-mouse B220/PE (RA3-6B2) | Biolegend | Cat#103207 |

| anti-mouse CD3e/FITC (17A2) | Biolegend | Cat#100203 |

| anti-mouse CD3/eF660 (17A2) | eBioscience | Cat#50-0032-82 |

| anti-mouse CD4/eF450 (GK1.5) | eBioscience | Cat#48-0041-82 |

| anti-mouse CD8/PE (53–6.7) | Biolegend | Cat#100707 |

| H-2Kb/SIINFEKL-Dextramer | Immudex | Cat#JD2163 |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| synthetic peptide OVA257-264 (SIINFEKL) | NeoMPS | N/A |

| OVA protein | Calbiochem | N/A |

| DOTAP Liposomal Transfection Reagent | Roche | Cat#11 202 375 001 |

| in vivo-jetPEI | Polyplus transfection | Cat#201-50G |

| Diphteria toxin | Calbiochem | N/A |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| ProcartaPlex mouse cytokine/chemokine 26Plex immunoassay kit | eBioscience | Cat#EPX260-26088-901 |

| ProcartaPlex Mouse IFN-α and IFN-β 2Plex Assay | eBioscience | Cat#EPX020-22187-901 |

| SV Total RNA Isolation System (modified for DNA preparation) | Promega | N/A |

| NucleoSpin RNA XS | Machery-Nagel | Cat#740902.50 |

| nCounter Mouse Pan Cancer Immune Profiling Panel | Nanostring technologies | Cat#XT-CSO-MIP1-12 |

| Agilent RNA 6000 Pico Kit | Agilent technologies | Cat#5067-1513 |

| DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit | QIAGEN | Cat#69504 |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| HeLa cells | ATCC | Cat#CCL-2 |

| B16-F10 cells | Univ. of Masachusetts, Worcester, MA 01655 | N/A |

| B16-OVA cells | Univ. of Masachusetts, Worcester, MA 01655 | N/A |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Mouse: B6.FVB-Tg(Itgax-DTR/GFP)57Lan/J | Jackson Laboratory | Stock No: 004509 |

| Mouse: B6.Cg-Tg(Itgax-cre) 1-1Reiz/J | Jackson Laboratory | Stock No: 008068 |

| Mouse: B6;129-Mavstm1Zjc/J | Jackson Laboratory | Stock No: 008634 |