Abstract

Purpose:

To describe perceptions of physical activity, opinions, on intergenerational approaches to physical activity and a vision for increasing physical activity in an underresourced urban community.

Approach:

Focus groups embedded in a large Community-Based Participatory Research Project.

Setting:

West and Southwest Philadelphia.

Participants:

15 parents, 16 youth, and 14 athletic coaches; youth were 13 to 18 years old and attended West Philadelphia schools; parents’ children attended West Philadelphia schools; and coaches worked in West Philadelphia schools.

Methods:

Six focus groups (2 youth, 2 parent, and 2 coach) were conducted guided by the Socio-Ecological Model; transcriptions were analyzed using a rigorous process of directed content analysis.

Results:

Factors on all levels of the Socio-Ecological Model influence the perception of and engagement in physical activity for youth and their families. Future strategies to increase engagement in physical activity need to be collaborative and multifaceted.

Conclusion:

When physical activity is reframed as a broad goal that is normative and gender-neutral, a potential exists to engage youth and their families over their lifetimes; with attention to cross-sector collaboration and resource sharing, engaging and sustainable intergenerational physical activity interventions can be developed to promote health in underresourced urban communities.

Keywords: physical activity, intergenerational, underresourced community, Socio-Ecological Model, Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR), qualitative methods

Lack of physical activity is a nationwide public health crisis and a risk factor for prevalent diseases such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease in the United States for youth and adults.1–3 Only 27% of US children in grades 9 through 12 and 51% of adults meet the current US physical activity guidelines, greatly increasing their risk of poor health outcomes.4,5 Individuals who are members of racial/ethnic monitory groups or who live in poverty have lower levels of physical activity most likely because of structural factors such as racism, barriers to economic opportunity, and neighborhood segregation make it harder to be active.6,7

At 25.7%, Philadelphia’s poverty rate is highest of the 10 largest cities in the United States. Four (79.1%) out of 5 Philadelphia youth do not participate in government-recommended levels of physical activity and 1 (21.9%) of 5 youth perform no physical activity at all, a problem especially prevalent among African American girls (29.8%). West Philadelphia (sometimes known as West and Southwest Philadelphia) includes areas geographically west and southwest of the Schuylkill River. Seventy-seven percent of the population of West Philadelphia is non-Hispanic black or African American. Forty-three percent of community members in West Philadelphia are affected by obesity.8–10

Factors on all ecological levels have been found to be important in understanding the levels of physical activity in youth. Youth are most influenced by proximal/personal factors, including family and friends, followed by more distal factors including school and neighborhood.11,12 Proximal/personal factors such as self-efficacy are particularly important for boys, while other factors such as instrumental or tangible support for physical activity are most important for girls.13 Parental support for physical activity typically wanes with increasing age14 but remains influential in helping certain youth maintain physical activity, especially girls. Parental physical activity self-efficacy may not influence that of their own children, but parents can serve as positive role models,15,16 and family participation, direct parental engagement, and parental support are important for sustaining physical activity in both girls and boys.16–20

Research has demonstrated both the potential benefits and the positive moderating effect of family-level interventions increase intervention efficacy in African American youth and adults.13,18,20–22 Intergenerational approaches that incorporate 2 and 3 generations hold promise not only to increase the interventions’ health impact on youth (due to increased instrumental or tangible and emotional or social support) but also to influence the health outcomes for entire families.23

Purpose

In order to promote and support intergenerational physical activity, existing resources, barriers to building sustainable policies and programs, and availability and acceptability of intergenerational approaches must be examined.24 Thus, the purpose of this study was to gauge the interests, goals, priorities, and barriers related to physical activity in West Philadelphia; to explore participant perceptions of intergenerational approaches to physical activity; and to elicit their vision about increasing physical activity in their community.17

Approach

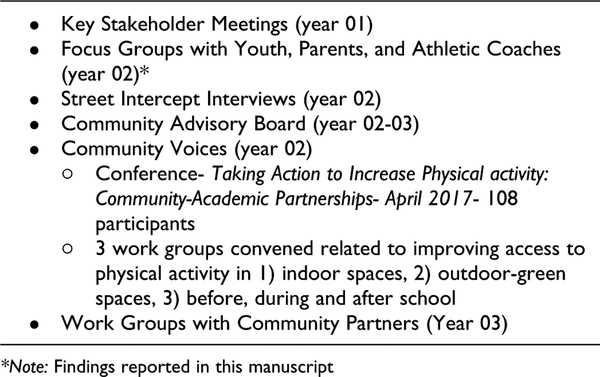

The Socio-Ecological Model (SEM), applied via a Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) approach,20,24 guided a large CBPR collaboration among community partners.25 As shown in Figure 1, the overall project included key stakeholders, focus groups, street intercept interviews, a community advisory board, work groups, and a conference to elicit community voices about physical activity as well as methods for improving physical activity. Key stakeholders were from the University, community organizations, and public schools. The University is large, private, and research intensive. Members of the School of Nursing, the Center for Public Health Initiatives, and the Netter Center for Community Partnerships were University participants. Twelve key community organizations were recruited based on their mission related to physical activity for youth and their families, commitment to long-term partnerships, and history of positive engagement in the community. Youth, parents, and athletic coaches from the public schools participated in the focus groups reported in this article as well as in the community advisory board, conference, and work groups for the larger project.

Figure 1.

Community/academic partnerships to increase activity in youth and their families: implementation of 3-year community-based participatory process.

The SEM was used throughout the project to consider individual and interpersonal (microsystem), organizations/institutions (exosystem), and social–political–economic (macrosystem) factors. This article reports the results of the focus groups; however, input was garnered during other facets of the overall study to plan and implement the focus groups and evaluate the focus group data.

Setting

The youth and parent focus groups were held in 2 schools, one in Southwest Philadelphia and one in West Philadelphia. The athletic coach focus groups were held in the Netter Center which is part of the University and is in West Philadelphia.

Participants

Participants for the focus groups were recruited by word of mouth, flyers, and e-mail. The eligibility criteria for the youth and parents included (1) live in West (or Southwest) Philadelphia; (2) (youth) 13 to 18 years old; (3) (youth) attend West (or Southwest) Philadelphia Schools; (4) (parents) children attend school in West (or Southwest) Philadelphia; and (5) able to read and understand written and spoken English. Youth and their parents could enroll independently; that is, both did not have to enroll. Eligibility criteria for athletic coaches included (1) employed by the University (via the University’s Netter Center) who hires coaches and places them in positions in the community; (2) work in a West (or Southwest) Philadelphia school; and (3) able to read and understand written and spoken English. Each participant received a $20 gift card for participating

Tables 1 to 3 describe the characteristics of the 45 participants (15 parents, 16 youth, and 14 coaches) who participated in the 6 focus groups. All parents and youth identified as African American as did 71 % (n = 10) of the coaches. Most parents were 34 to 48 years old (38%), had some college or technical school (47%), had never been married (53%), and earned less than $39 000, which would be 150% of the federal poverty for a family of 4 (87%). Most youth were 16 to 17 years old (44%). Most coaches were 27 to 30 years old (50%) and were college graduates. Many of the parents, youth, and coaches and their family members are affected by chronic conditions such as asthma, diabetes, and high blood pressure.

Table 1.

Parent Demographic Characteristics.

| Frequency | ||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | n = 15 | % |

| Agea | ||

| 18–33 | 3 | 20 |

| 34–49 | 5 | 33 |

| 59–65 | 4 | 27 |

| 66+ | 1 | 7 |

| Unknown | 2 | 13 |

| Race | ||

| African American | 15 | 100 |

| Neighborhood | ||

| West Philadelphia | 12 | 80 |

| Southwest Philadelphia | 3 | 20 |

| Education | ||

| Grades 9–11 (some high school) | 2 | 13 |

| Grade 12 or GED (high school graduate) | 5 | 33 |

| Some college or technical school (1–3 years) | 7 | 47 |

| College graduate (4 years) | 1 | 7 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 5 | 33 |

| Divorced | 1 | 7 |

| Never been married | 8 | 53 |

| Member of an unmarried couple | 1 | 7 |

| Household income | ||

| Less than $10 000 | 4 | 27 |

| $10 000–$19 000 | 1 | 7 |

| $20 000–$39 000 | 8 | 53 |

| $80 000+ | 2 | 13 |

| Health conditions | Patient, % | Family Member, % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arthritis | 3 | 20 | 7 | 47 |

| Asthma | 3 | 20 | 10 | 67 |

| Cancer | 1 | 7 | 7 | 47 |

| COPD | 0 | 0 | 5 | 33 |

| Diabetes | 2 | 13 | 9 | 60 |

| Gallstones | 1 | 7 | 1 | 7 |

| Gout | 0 | 0 | 4 | 27 |

| Heart disease | 0 | 0 | 6 | 40 |

| High cholesterol | 1 | 7 | 6 | 40 |

| High blood pressure | 5 | 33 | 8 | 53 |

| Kidney/renal disease | 0 | 0 | 4 | 27 |

| Liver disease | 0 | 0 | 4 | 27 |

| Sleep apnea | 2 | 13 | 3 | 20 |

| Stroke | 0 | 0 | 3 | 20 |

| Thyroid disease | 0 | 0 | 4 | 27 |

Abbreviation: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Two missing values.

Table 3.

Coach Demographic Characteristics.

| Frequency | ||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | n = 14 | % |

| Column 1 | Column 2 | Column 3 |

| Age | ||

| 27–30 | 7 | 50 |

| 31–34 | 4 | 29 |

| 35–38 | 1 | 7 |

| 39+ | 2 | 14 |

| Race | ||

| White | 2 | 14 |

| African American | 10 | 71 |

| Native American | 1 | 7 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1 | 7 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Latino | 1 | 7 |

| Neighborhood | ||

| West Philadelphia | 9 | 64 |

| South Philadelphia | 1 | 7 |

| Southwest Philadelphia | 1 | 7 |

| Northwest Philadelphia | 1 | 7 |

| Other | 2 | 14 |

| Education | ||

| Some college or technical school (1–3 years) | 1 | 7 |

| College graduate (4 years) | 7 | 50 |

| Advanced degree | 6 | 43 |

| Household income | ||

| $30 000–$39 000 | 5 | 36 |

| $40 000–$49 000 | 5 | 36 |

| $50 000–$59 000 | 1 | 7 |

| $60 000+ | 3 | 22 |

| Employer | ||

| Penn/Netter Center | 1 | 7 |

| CIS Philadelphia | 1 | 7 |

| Various schools | 1 | 7 |

| Amtrak | 1 | 7a |

| Job title | ||

| Program director, coordinator, manager | 11 | 79 |

| Educator/coach | 1 | 7 |

| Teen parent counselor | 1 | 7 |

| Tech support specialist | 1 | 7a |

| Health conditions | Patient, % | Family Member, % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arthritis | 2 | 14 | 7 | 50 |

| Asthma | 2 | 14 | 6 | 43 |

| Cancer | 0 | 0 | 11 | 79 |

| COPD | 0 | 0 | 2 | 14 |

| Diabetes | 0 | 0 | 10 | 71 |

| Gallstones | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 |

| Gout | 0 | 0 | 4 | 29 |

| Heart disease | 0 | 0 | 6 | 43 |

| High cholesterol | 0 | 0 | 8 | 57 |

| High blood pressure | 0 | 0 | 10 | 71 |

| Kidney/renal disease | 0 | 0 | 3 | 21 |

| Liver disease | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 |

| Sleep apnea | 0 | 0 | 3 | 21 |

| Stroke | 0 | 0 | 4 | 29 |

| Thyroid disease | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 |

Abbreviation: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Some coaches hold multiple jobs.

Table 4 describes respondents’ self-reported activity habits, locations where physical activity took place, time spent doing the activity, and intensity of the activity. Popular activities across all groups included walking, dancing, muscle strengthening, and cardio exercises. Most parents, youth, and coaches reported exercising at home.

Table 4.

Description of Participant’s Physical Activity.

| Parents, n = 15 | Youth, n = 16 | Athletic Coaches, n = 14 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of activity | ||||||

| Walking | 14 | 93 | 14 | 87 | 10 | 71 |

| Jogging | 5 | 33 | 5 | 31 | 7 | 50 |

| Running | 5 | 33 | 5 | 31 | 6 | 42 |

| Swimming | 2 | 13 | 2 | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| Bicycling | 4 | 26 | 4 | 25 | 5 | 35 |

| Dancing | 7 | 46 | 7 | 43 | 3 | 21 |

| Basketball | 5 | 33 | 5 | 31 | 4 | 28 |

| Football | 2 | 13 | 2 | 12 | 2 | 14 |

| Soccer | 1 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Lacrosse | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 28 |

| Muscle strengthening/cardio | 5 | 33 | 5 | 31 | 11 | 78 |

| Other | 1 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 21 |

| How many times per week do you engage in moderate-intensity aerobic activity such as brisk walking, jogging, running, swimming, and/or bicycling? | ||||||

| None | 1 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 14 |

| Once every week | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Twice every week | 5 | 33 | 5 | 31 | 1 | 7 |

| Three times every week | 5 | 33 | 5 | 31 | 5 | 35 |

| Four times or more every week | 4 | 26 | 4 | 25 | 6 | 42 |

| How many hours each week do you engage in your physical activity? | ||||||

| None | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 |

| Less than 1 h/wk | 2 | 13 | 2 | 12 | 4 | 28 |

| 2 h/wk | 3 | 20 | 3 | 18 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 h/wk | 3 | 20 | 3 | 18 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 h/wk | 2 | 13 | 2 | 12 | 2 | 14 |

| 5 hours or more per week | 5 | 33 | 5 | 31 | 6 | 42 |

| How do you rate the level of intensity of your current physical activity/activities? | ||||||

| None | 1 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 14 |

| Light | 1 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 14 |

| Moderate | 11 | 73 | 11 | 68 | 7 | 50 |

| Vigorous | 2 | 13 | 2 | 12 | 2 | 14 |

| Where do you exercise? (You may choose more than one answer) | ||||||

| No place | 1 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 14 |

| Home | 9 | 60 | 9 | 56 | 9 | 64 |

| School | 5 | 33 | 5 | 31 | 3 | 21 |

| Rec center | 3 | 20 | 3 | 18 | 4 | 28 |

| The Y | 1 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 7 |

| Fitness club | 2 | 13 | 2 | 12 | 4 | 28 |

| Other | 5 | 33 | 5 | 31 | 5 | 35 |

Method

As a part of the overall project, we conducted a series of 6 focus groups (2 youth, 2 parent, and 2 coach). Before each focus group, each participant was asked to fill out a questionnaire about demographic information, current activity level, and physical health. Results of the demographic questionnaire were entered manually into a Redcap database maintained by the study coordinator. Descriptive statistics were obtained from this database.

An institutional review board of the University approved all study procedures (Protocol Number 824623). Facilitators greeted participants and reviewed and obtained informed consent documents. Semi-structured focus group guides were used to facilitate discussion. Participants were provided food and refreshments during the focus groups. Each focus group lasted approximately 60 to 90 minutes. Facilitators for the focus groups were trained by an experienced focus group leader for 1 and one-half hours including consideration of issues related to the process and content of conducting focus groups and issues related specifically to this series of focus groups. The facilitators led the discussion; one obtained field notes and others assisted as necessary with logistics. The semi-structured guides were based on input from key stakeholders and the community advisory board for the larger project (see Figure 1), the SEM, and the literature. The 3 focus group discussions covered similar topics but were tailored to each type of group. The interview guides also reflected the discussions in our ongoing community advisory board meetings as well as specific feedback on draft interview guides. See Supplemental Materials (Supplemental Tables 1–3) for a copy of each guide.

The electronic recordings were transcribed by a professional transcription service using Microsoft Word (Microsoft 365) and then uploaded into Atlas.ti (Atlas.ti 8.0) after their content was verified for accuracy. A directed content analysis approach was used, based on CBPR and SEM, and included a combination of both deductive and inductive approaches.26 Teams of 2 coders and the senior author (JD) reviewed all transcripts,27 and an audit trail was created in order to validate the process of data analysis with the goal of strengthening the scientific rigor of the analysis.28 A combination of “start codes” (those identified from the focus group guide and those inductively derived during the analysis) were continuously revised throughout the process. Discrepancies between coders were resolved by building consensus. Analysis proceeded from specific codes to broader categories to resultant larger themes28,29 and treated each group (youth, parents, and coaches) as the unit of analysis and focused on identifying overall themes from each group. Because data from the 6 groups offered similar themes, data were combined, and it was determined that saturation had been achieved.29

Results

Two broad themes were identified and discussed below with exemplar quotations from youth (y), parents (p), and coaches (c). The themes reflect microsystem, exosystem, and macrosystem factors that facilitate or inhibit engagement in physical activity as well as the development, implementation, and evaluation of sustainable strategies to increase physical activity to improve health outcomes.

Theme 1: Factors on all levels of the SEM influence the perception of and engagement in physical activity for youth and their families.

Microsystem

Meaning of physical activity.

Participants in all focus groups attested to the importance of what physical activity means to the individual, family, and community while noting that perceptions about the importance of physical activity may be situationally dependent. Youth agreed on the importance of physical activity for the family. Parents and youth acknowledged the physical benefits of physical activity and parents thought it was most important to people as they age. Participants also endorsed physical activity programs that included educational components such as general health, nutrition, academics/learning, and safety in addition to the physical activity because many of their members are affected by these interrelated problems.

Relationships, resources, and responsibilities.

Relationships, resources, responsibilities as well as other factors were discussed as influencing participation. Most participants said that relationships were the primary reason why youth and parents participate in physical activity; they noted it is especially powerful when an active person suggests to someone that they should/could be more active and could be active with them. While many youth said that parents and grandparents encouraged them to be physically active, a few youth related that “… no one encourages me.”

Coaches thought the relationship of youth and parents was most important because parents could communicate expectations about the importance of physical activity, prioritize physical activity (eg, avoid scheduling routine appointments during practice), and support physical activity (eg, provide transportation and watch the activity). Such engagement, however, may be limited by parents’ views of themselves and their children as either active or inactive and their inability to influence their child’s activity level. For example, one mother explained, “My daughter hasn’t shown an interest.” Other parents, however, did see how they could increase physical activity in the family or for family members:

P: They weren’t as active as they are now; I’m proud of myself for that. Just keeping them moving and keeping them less in the house, sitting around watching TV, on their phone. This doesn’t apply just children, but to us also; my husband does a lot of walking and we do too.

Resources needed for youth to participate in programs as well as barriers to participation were discussed by parents and coaches. Coaches reported in both focus groups that lack of family-based resources may present barriers to participation. For instance, youth told coaches that parents sometimes told them not participate because they had no backup clothing or shoes or the time/resources to clean clothing and shoes worn during sports. Many parents expressed a lack of knowledge about community venues for physical activity as well as a lack of personal resources to access them; however, other parents gave suggestions for how to remediate some concerns. Direct costs including fees to access facilities or services, expenses for uniforms, equipment, and related items, and transportation created significant barriers, as 87% of the sample lived in deep poverty. Parents noted that costs increase with the number of family members engaged in a physical activity. Indirect costs include lost wages for youth and parents alike.

All participants described responsibilities that interfered with participation in physical activity. Parents stated that they could be overwhelmed with everything they had to accomplish, citing busy schedules for themselves and their children, parental responsibilities, and logistics of accomplishing responsibilities. Parents described feeling tired because they had to get up early or had chaotic work schedules. They complained, “Exercise doesn’t energize you like they say.” As a result of these and other issues, coaches observed that the same group of parents were engaged in supporting children’s participation in physical activity.

Youth, parents, and coaches also believed other individual and interpersonal factors influenced participation in physical activity, including physical ability to participate, age, technology, gender, and intrinsic motivation. The physical ability to participate, specifically issues related to obesity, was singled out repeatedly by youth and parents as a major barrier to participating in physical activity because participants could be “embarrassed” or “uncomfortable.” Conversations seemed to connote that this barrier was often unspoken and assumed. Similar concerns about obesity were not mentioned in the coach groups. Parents were most vocal about personal concerns related to their own health and how their own health problems interfere with physical activity. Conversely maintaining and losing weight was most frequently cited in all groups as a reason to participate in physical activity.

In addition, socialized gender roles may be important. For example girls may prioritize appearance over participation when same gender peers and siblings do the same. One coach said about girls, “… appearance and grooming may become increasingly important by middle school.”

Finally, emotional problems were cited throughout youth and parent discussions. Issues included being too depressed to exercise, not feeling motivated to exercise, and having fears that prevented exercise (eg, the fear of water prevented swimming). One of the youth suggested the best way to overcome issues with motivation was:

Y: … to take ideas from kids on what they want to do. I don’t know ‘cause it’s like interest. Like if you’re not interested in something, you’re not gonna do it.

Exosystem

Exosystem factors included issues regarding physical space, safety, logistics, and technology. Physical spaces were judged relative to their perceived appropriateness, safety, and accessibility. Indoor spaces included city recreation centers, schools, and the YMCA. Outdoor spaces included parks, but were noted to be limited due to the amount of “concrete” in the urban environment. Coaches underscored the importance of leadership with regard to the identification and use of space. Using the example of parks, one coach said,

C: Leadership gets them in or keeps them out of the park. We need to be out in the community… we may work at a school and doing activity but never set foot in the rec[reation] center across the street … we need to link with each other.

Coaches explained various perspectives about the safety of spaces. In terms of indoor space, coaches reiterated that all areas within a space need to be considered; for instance, while schools may have a gym, it is unlikely that the school has monitored facilities for showering or changing clothes. In addition, the qualifications of staff in the space must be considered; therefore, parents generally felt their children were safer in school-connected activities because school staff must undergo background checks. In terms of outdoor spaces, coaches said that parents, coaches, and youth may think a space is or isn’t dangerous depending on their actual familiarity with the space.

Logistics were also a concern for parents and youth who wanted well-designed programs that were easy to access. Youth reported, “A program has got to be well organized too … because if you are not well-organized, then it will be havoc.” Coaches thought that the need for business acumen including budgeting and strategic planning was crucial along with the ability to communicate and collaborate. Finally, coaches felt resources were needed to logistically integrate academic support into physical activity programs and vice versa, especially in after school programs, to support the potential of success for the youth and the program.

Technology was viewed as both a potential solution and a hindrance to physical activity. Parents and coaches suggested that a website could help increase knowledge about available resources for physical activity, including the type of activities and how they could be accessed. Conversely, parents thought technology preoccupied youth and took away time and energy that could be directed toward physical activity.

Macrosystem

Resources from and relationships with the city, community, and the University were described with regard to physical activity of youth and their families. Parents and coaches highlighted the money needed to maintain physical resources, provide programs, and hire the right individuals in the schools and recreation centers. Parents and coaches noted that within the past 10 years, Philadelphia had put more funding and support into recreation centers, pools, and libraries (mentioned in relationship to being a source of health information) that had been closed during more desperate financial times in the city. Finally, as explained by this coach, financial resources are needed to hire staff that can build quality programs, act as ambassadors for their organizations, and provide leadership to work with the community:

C: We are trying to create a better relationship between the University and the community and physical activity … [Requires] a really big investment in a number of individuals … employing the right people, sometimes that’s a lot of the battle.

Neighborhood politics also arose during the discussion of funding. One of the coaches commented, “Sports are political,” meaning that neighborhoods had identities related to sports and competed with each other. Any proposed changes had to start by renegotiating those established relationships and identities.

Theme 2: Physical activity strategies need to be collaborative and multifaceted.

Participants emphasized multifaceted approaches to improve engagement in physical activity that takes into account individuals, organizations, and the city/community. They stated that communication, networking with the community, building relationships, and leadership skill-building were needed on every level. Collaboration with city government and academics was needed to leverage support and pool resources to maximize the impact on youth and families. The merits of collaboration were recounted by one coach’s experience:

C: … I worked in a program and we literally had the boys and girls club across the street from our program and …. We found out that the boys and girls club received a grant from the Stock Up for Success Foundation. They didn’t have enough kids, but we had all the kids in the world to use their field, to use their gym, and to use their swimming pool …

In addition, focus group members felt that successful programs, especially those that have spread across the city, should be examined closely to see if they could be used as models especially those that enhance engagement and participation:

P: The nature of future programs should be innovative … all of this stuff needs to start to kick and relate and tie together nutrition, physical activity, and academics.

Physical activity should be fun, strategies should be gamified, musical, and offer alternative for participation (low, moderate, and high intensity). Rewards would ideally be included to attract those who would otherwise not be involved and parents and youth should be rewarded for participating together (eg, lower fee).

Intergenerational programs, while acknowledged as not being widely available, were discussed positively by youth, parents, and coaches. As one coach said,

C: If I can get the whole family, then a cycle of disconnect with their own self-care and wellness will be broken … now you’re building the time back together.

Youth participants stressed that such programs would have to be consistently offered, well organized, and versatile to meet the needs of those involved. While previous attempts at family-oriented activities may be well intentioned, some youth wondered if family members could and would be able to follow through with a commitment to participating. Some younger youth participants verbalized some reluctance to participate in family-oriented physical activity and wanted activities separate from the parents, while older teenagers were more open to intergenerational activities. Youth, parent, and coach participants, however, were specific in saying that intergenerational activities do not have to be within the same family but could be multigenerational and across families. They were also specific in saying that the nature of activity would have to be appropriate. In the qualitative and demographic data, most mentioned Dance for Health, which is an intergenerational program.30 Competitive activities were also suggested by some youth (parents vs youth).

Discussion

The findings of this research demonstrate that the meaning and accessibility of physical activity varies among parents, youth, and coaches in West and Southwest Philadelphia and factors at all level of the SEM influence physical activity. These findings suggest that physical activity was conceptualized much more broadly than just “sports” or structured workouts (eg, going to the gym). When physical activity was reframed as a broad goal that is normative and gender-neutral, a potential exists to engage youth and their families over their lifetimes. This insight is novel and based on systematic triangulation of youth, parents, and coach perspectives gathered within the community setting and analyzed through the lens of the SEM.

Youth and parents agreed that physical activity was a family affair. Past research has explicated how members of the family organize around physical activity through encouraging self-efficacy, providing emotional and tangible support, serving as role models to each other, and participating “together” as they are able.31 Family engagement in physical activity was perceived as both a facilitator of activity and a way to bolster relationships and the health of families.

Although findings reported in this article are limited to the focus groups that we conducted, they were interpreted using insights and supports from a larger project and more in-depth community engagement. Future steps will incorporate a focus on strengths and perspectives of individuals and families in the community, recognition of the pressures felt by the youth, parents, and coaches, and the need for collaborative problem-solving to reduce barriers to intergenerational activity.

Conclusion

Our findings reinforce the importance of considering all levels of the SEM when developing physical activity interventions, particularly for vulnerable communities who face increased barriers to health promotion. Individual and interpersonal, institutional, and organizational factors influenced the perception of physical activity for youth and their families. Even the most creative and passionate program leaders cannot work effectively across these complex issues without some kind of corporate partnership or business skills. Harnessing the power of institutions and cross-sector partnerships (city/school/community/university) to accomplish mutually defined missions and to provide resources is crucial in developing sustainable interventions.32–35

Supplementary Material

Table 2.

Youth Demographic Characteristics.

| Frequency | ||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | n = 16 | % |

| Ages | ||

| 16–17 | 7 | 44 |

| 18–19 | 9 | 56 |

| Race | ||

| African American | 16 | 100 |

| Neighborhood | ||

| West Philadelphia | 14 | 88 |

| Southwest Philadelphia | 2 | 12 |

| Health conditions | Patient, % | Family Member, % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arthritis | 0 | 0 | 3 | 19 |

| Asthma | 2 | 13 | 7 | 44 |

| Cancer | 0 | 0 | 6 | 38 |

| COPD | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| Diabetes | 1 | 6 | 9 | 56 |

| Gallstones | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| Gout | 0 | 0 | 4 | 25 |

| Heart disease | 0 | 0 | 4 | 25 |

| High cholesterol | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| High blood pressure | 0 | 0 | 10 | 63 |

| Kidney/renal disease | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| Liver disease | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| Sleep apnea | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| Stroke | 0 | 0 | 3 | 19 |

| Thyroid disease | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

Abbreviation: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

SO WHAT?

As in many cities, multiple initiatives in Philadelphia are devoted to increasing physical activity in youth and their families. Much enthusiasm exists for expanding access to physical activity programs, but there is a great need for systematic community assessments and for networking and resource-sharing partnerships among systems to operate effectively and reduce overlap. With attention to such collaboration, engaging and sustainable intergenerational physical activity programs can be developed to support the lifelong health of children and families in underresourced communities.

This systematic investigation examines the perspectives of key stakeholder groups about existing resources and barriers to building sustainable policies and programs and the availability and acceptability of intergenerational approaches. The public health significance of the manuscript includes attention to multilevel influences on the perception of and engagement in physical activity for youth and their families. With attention to multilevel factors that influence physical activity, structures and programs can be put in place to promote engagement in physical activity and better health outcomes for children, families, and communities.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work is supported by Grant No. R13 HD085960 and T32 NR007100 from the National Institutes Child Health and Development, National Institutes of Health, and the National Institute of Nursing Research.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Janssen I, LeBlanc AG. Systematic review of health benefits of physical activity and fitness in school-aged children and youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7(1):40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warburton DE, Nicol CW, Bredin SS. Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. CMAJ. 2006;174(6):801–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lipman TH, Ratcliffe S, Cooper R, Katz L. Population-based survey of the prevalence of type 1 and type 2 diabetes in school children in Philadelphia. J Diabetes. 2013;5(4): 456–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reiner M, Niermann C, Jekauc D, Wall A. Long-term health benefits of physical activity – a systematic review of longitudinal studies. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Exercise or physical activity. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/exercise.htm. Updated January 20, 2017. Accessed October 10, 2018.

- 6.Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin S. Youth risk behavior surveillance — United States, 2013. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/ss/ss6304.pdf. Updated 2013. [PubMed]

- 7.Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Physical activity guidelines for adults. https://health.gov/paguidelines/.Updated 2008. Accessed October 10, 2018.

- 8.Capri S, Daniels SR, Drewnoski A, et al. Influence of race, ethnicity, and culture on childhood obesity: implications for prevention and treatment. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(11): 2211–2221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Adult obesity by state, 2015. http://stateofobesity.org/adult-obesity/. Accessed October 10, 2018.

- 10.The Pew Charitable Trust. Philadelphia’s poor: Who they are, where they live, and how that has changed. November 2017. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2017/11/philadelphias-poor. Accessed October 10, 2018.

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Community Health Status Indicators. Health indicators: adult physical activity inactivity. https://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dch/programs/communitiesputtingpreventiontowork/communities/profiles/both-pa_philadelphia.htm. Updated 2012. Accessed October 10, 2018.

- 12.Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. County health rankings and roadmap. http://www.countyhealthrankings.org/sites/default/files/state/downloads/CHR2017_PA.pdf. Updated 2017.

- 13.Kuo J, Voorhees CC, Haythornthwaite JA, Young DR. Associations between family support, family intimacy, and neighborhood violence and physical activity in urban adolescent girls. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):101–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson DK, Lawman HG, Segal M, Chappell S. Neighborhood and parental supports for physical activity in minority adolescents. Am JP rev Med. 2011;41(4):399–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rutkowski EM, Connelly CD. Self-efficacy and physical activity in adolescent and parent dyads. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2012;17(1): 51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davison KK, Jago R. Change in parent and peer support across ages 9 to 15 yr and adolescent girls’ physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(9):1816–1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams W, Berry D. It’s time to get moving: what black mothers say about physical activity. J Natl Black Nurses Assoc. 2014; 25(2):47. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wright MS, Wilson DK, Griffin S, Evans A. A qualitative study of parental modeling and social support for physical activity in underserved adolescents. Health Educ Res. 2010; 25(2):224–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berge JM, Wall M, Larson N, Loth KA, Neumark-Sztainer D. Family functioning: associations with weight status, eating behaviors, and physical activity in adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(3):351–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goh YY, Bogart LM, Sipple-Asher BK, et al. Using community-based participatory research to identify potential interventions to overcome barriers to adolescents’ healthy eating and physical activity. J Behav Med. 2009;32(5):491–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davison KK, Jurkowski JM, Li K, Kranz S, Lawson HA. A childhood obesity intervention developed by families for families: results from a pilot study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013; 10(3):5868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flora PK, Faulkner GE. Physical activity: an innovative context for intergenerational programming. J Intergenerat Relat. 2007; 4(4):63–74. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swanson M, Studts CR, Bardach SH, Bersamin A, Schoenberg NE. Intergenerational energy balance interventions: a systematic literature review. Health Educ Behav. 2011;38(2):171–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Werner D, Teufel J, Holtgrave PL, Brown SL. Active generations: an intergenerational approach to preventing childhood obesity. J Sch Health. 2012;82(7):382–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McConnell J, Naylor P. Feasibility of an intergenerational-physical-activity leadership intervention. J Intergenerat Relat. 2016; 14(3):220–241. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruff C, Alexander I, McKie C. The use of focus group methodology in health disparities research. Nurs Outlook. 2005;53(3):15–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Handler A, Issel M, Turnock B. A conceptual framework to measure performance of the public health system. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(8):1235–1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 1988; 15(4):351–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Estrada-Martinez L, et al. Engaging urban residents in assessing neighborhood environments and their implications for health. J Urban Health. 2006;83(3):523–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hsieh HF, Shannon S. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu YP, Thompson D, Aroian KJ, McQuaid EL, Deatrick J. Writing and evaluating qualitative research reports. J Pediatr Psychol. 2016;41(5):493–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whittemore R, Chase S, Mandle C. Validity in qualitative research. Qual Health Res. 2001;11(4):522–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schroeder K, Ratcliffe SJ, Perez A, Earley D, Bowman C, Lipman TH. Dance for health: an intergenerational program to increase access to physical activity. J Pediatr Nurs. 2017;37(1):29–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trost SG, Loprinzi PD. Parental influences on physical activity behavior in children and adolescents: a brief review. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2011;5(3):171–181. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harkvay I Engaging urban universities as anchor institutions for health equity. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(12):2155–2157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.