Abstract

Promising mitral valve (MV) repair concepts include leaflet augmentation and saddle shaped annuloplasty, and recent long-term studies have indicated that excessive tissue stress and the resulting strain-induced tissue failure are important etiologic factors leading to the recurrence of significant MR after repair. In the present work, we are aiming at developing a high-fidelity computational framework, incorporating detailed collagen fiber architecture, accurate constitutive models for soft valve tissues, and micro-anatomically accurate valvular geometry, for simulations of functional mitral valves which allows us to investigate the organ-level mechanical responses due to physiological loadings. This computational tools also provides a means, with some extension in the future, to help the understanding of the connection between the repair-induced altered stresses/strains and valve functions, and ultimately to aid in the optimal design of MV repair procedure with better performance and durability.

1. Introduction

Many surgeons have come to view mitral valve (MV) repair as the treatment of choice in patients with mitral regurgitation (MR) due to myxomatous leaflet degeneration and post infarction ventricular remodeling (ischemic mitral regurgitation - IMR) [1]. However, recent long-term studies have indicated that the recurrence of significant MR after repair may be much higher than previously believed, particularly in patients with IMR [2]. Since a significant number of these failures result from chordal, leaflet and suture line disruption, it has been suggested that excessive tissue stress and the resulting strain-induced tissue damage are important etiologic factors. We thus hypothesize that restoration of homeostatic normal MV leaflet tissue stress levels in IMR repair techniques ultimately leads to improved repair durability through restoration of normal MV responses. In the past two decades, computational approaches have begun to be realistically applied. For example, Driessen et al. [3, 4] developed a finite-element (FE) model to relate changes in collagen fiber content and orientation to the mechanical loading condition within the engineered heart valve construct demonstrating a resemblance to experimental data from native aortic heart valves. For the MV, the pioneering finite element work by Kunzelman [5, 6] has clearly demonstrated how computational modeling of MV function can provide insight into the relationship between the various components of the MV apparatus and MV function. Einstein et al. [7] simulated early acoustic detection of changes in MV properties leading to better management of MV diseases. However, these models with simplified micro-structural and anatomical representation of the MV only render an important first step in developing physiologically realistic models of heart valves. Therefore, the objective of this study is to develop a novel high-fidelity and micro-anatomically accurate 3D finite element (FE) model that incorporates detailed collagen fiber architecture, accurate constitutive models, and micro-anatomically accurate valvular geometry to predict the MV mechanical responses, and to assist with the improvement of MV repair techniques.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Specimen Preparation and Finite Element Model Generation

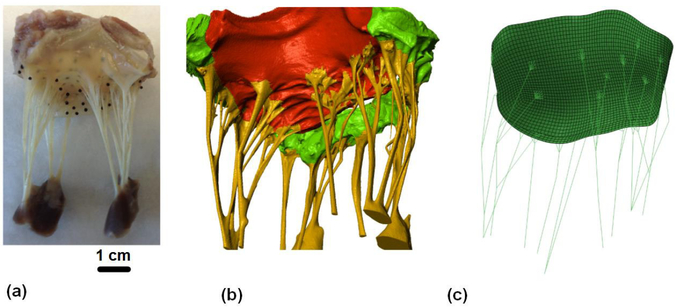

Ovine heart was obtained from local slaughterhouse (Harvest House Farms, Johnson City, TX). The entire heart was fixed in 4% aqueous paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 12 hours under systolic hydrostatic pressure [8]. Ebony glass beads were then placed on both anterior and posterior leaflets using fast-curing glue (cyanoacrylate, Bazic Products, CA, USA) as shown in Fig. 1 (a).

Fig. 1.

(a-b) MicroCT based reconstruction of an ovine mitral valve with fiducial markers for SALS mapping technique, and (c) resulting 3D finite element model with realistic chordae reconstruction

The fixed mitral valve was scanned using a high-resolution micro-CT scanner (Xradia, Inc., CA, USA), and the micro-CT images were then segmented in ScanIP (Simpleware, United Kingdom) to acquire micro-structurally accurate geometry of the MV apparatus (see Fig. 1 (b)). A thin-shell leaflet model with realistic chordae reconstruction was generated (see Fig. 1 (c)) for the following FE simulations.

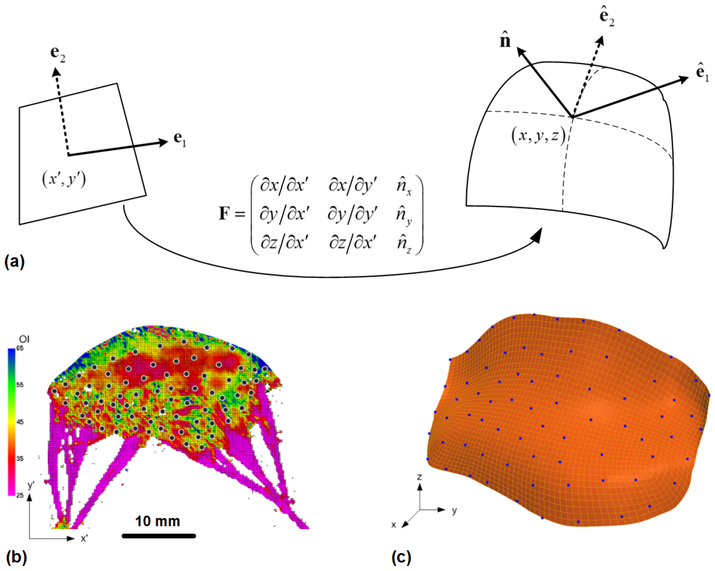

2.2. SALS Informed Mapping Technique

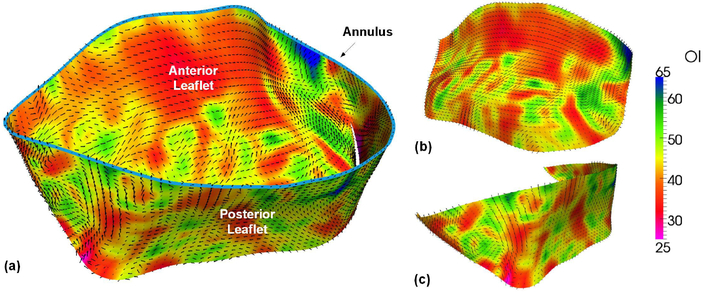

The MV leaflets were dissected and prepared for measurement of collagen fiber architecture using the small angle light scattering (SALS) technique [9, 10], including the preferred fiber orientation ϕf and the orientation index (OI) which indicates the strength of fiber alignment. As illustrated in Fig. 2 (a–c), SALS measured collagen fiber architecture was mapped onto the 3D MV FE mesh by utilizing the fiducial markers positions on the 2D microstructural data and their associated 3D coordinates. Local smoothing and interpolation were performed using the cubic B-spline function.

Fig. 2.

Schematic of SALS mapping technique. Each point on the 2D microstructural data shown in (a) was projected onto the 3D finite element mesh (b) using the fiducial markers and the cubic B-spline function for smoothing and interpolation.

The proposed mapping technique can be then used to estimate the changes of collagen fiber orientation due to deformation by

| (1) |

where R0(Θ) and R(ϑ) are the fiber distribution functions at the reference and deformed configurations, respectively, N(Θ)) is the unit vector of the preferred fiber direction associated with angle Θ, C is the right Cauchy-Green deformation tensor, and J is the Jacobian of the deformation gradient F.

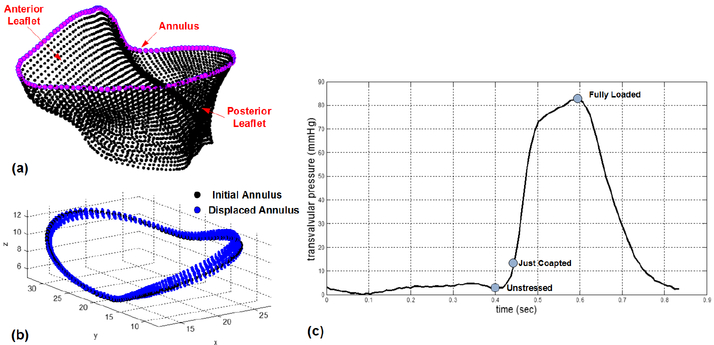

2.3. Finite Element Simulations in ABAQUS

Quasi-static simulations of MV closure during ventricular systole, with prescribed transvalvular pressure loadings and dynamic annular motions [11] (see Fig. 3) and self-contact behavior, were performed in FE commercial software ABAQUS (Simulia, RI, USA). Noted that the displacements associated with the translational degrees of freedom of the annulus nodes (margenta circles in Fig. 3(a)) are prescribed at each time increment in the FE simulations. The following general invariant-based constitutive model is employed for the stress-strain behavior of the MV tissues and is implemented in ABAQUS UMAT user subroutine:

| (2) |

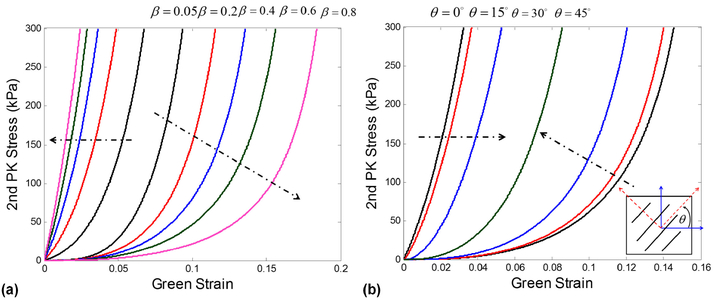

where I1 = trace(C), I4 = N · C · N, C10, C01, c0, c1, and c2 are material constants, and β is the parameter governs the level of anisotropy of the tissue materials, i.e., β = 0 is purely isotropy (randomly aligned fibers), β = 0.5 is the standard transversely isotropic model, which can be related to the strength of fiber alignment (OI) obtained from SALS test by β = (1.0 − OI/90). The proposed constitutive model can be viewed as a preluded devise that enables the investigation of how the material anisotropy at the tissue level affects the MV functional responses at the organ level. The two terms in the second bracket of Eq. 2 account for the responses of matrix and collagen fiber, respectively, and the first term in Eq. 2 improves the stability and solution convergence under low strain responses. Noted that incompressibility and plane-stress conditions are considered in the formulation of stress-strain relationships based on hyper-elasticity theory. Table 1 summarizes the model parameters models that are characterized from the standard biaxial and uniaxial testing data [12–14], including the isotropic and transversely isotropic models for MV leaflets and the tension-only model for the chordae tendineae component. The corresponding effects of different levels of anisotropy and local material axis on the stress-strain responses are illustrated in Fig. 4.

Fig. 3.

(a) Illustration of finite element nodes on the MV annulus, (b) prescribed dynamic annular motions in ABAQUS DISP user subroutine, and (c) transvalvular pressure loadings defined in ABAQUS AMPLITUDE module

Table 1.

Parameters of various constitutive models for MV apparatus

| Type | C10 (kPa) | C01 | c0 (kPa) | c1 | c2 | β |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isotropy (MV Leaflets) | 2.85 | 6.79 | 32.3 | 75.95 | 0 | 0 |

| Transversely Isotropy (MV Leaflets) | 0.84 | 28.68 | 13.93 | 79.79 | 66.03 | 0.5 |

| Marginal Chordae | 4.79 | 137.2 | — | — | — | — |

| Strut Chordae | 18.55 | 121.07 | — | — | — | — |

Fig. 4.

Illustration of MV tissue stress-strain responses: (a) effect of different levels of anisotropy, and (b) effect of local material axis

3. Results

The detailed micro-structural collagen fiber architecture was quantified by the SALS technique as shown in Fig. 2(b) along with the array of fiducial markers, and the resulting preferred fiber direction ϕf and the strength of fiber alignment (OI value) were successfully mapped onto the MicroCT based finite element mesh as demonstrated in Fig. 5(a). The SALS informed mapping results of individual anterior and posterior leaflets were presented in Fig. 5(b–c), respectively.

Fig. 5.

SALS informed mapping of mean fiber direction ϕf and orientation index (OI) onto 3D segmented finite element mesh (a) entire MV leaflets, (b) anterior leaflet, and(c) posterior leaflet (light blue curve in (a) shows the MV annulus boundary)

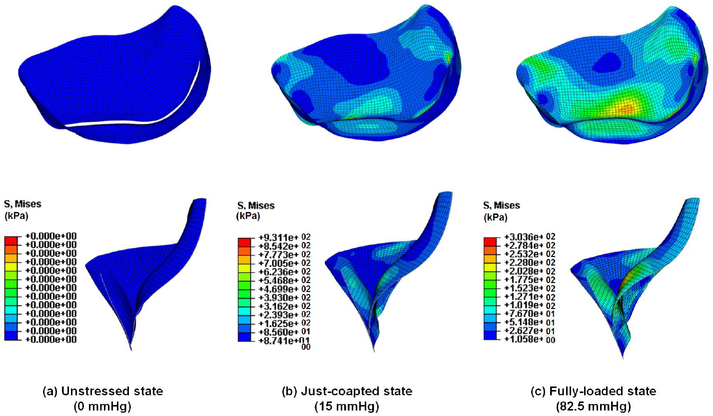

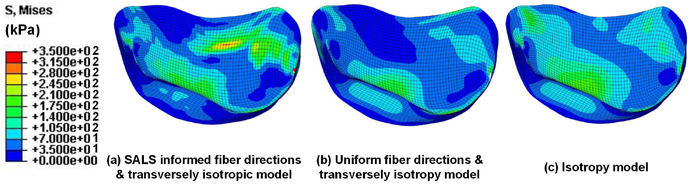

Fig. 6 showed the quasi-static simulation results of the von Mises stresses during MV closure at various pressure loadings. The results demonstrated the capability of the proposed computational framework to quantitatively predict the MV responses due to the alteration of external loadings. Moreover, parametric studies on the effects of preferred fiber directions and material anisotropy on the numerical predictions were presented in Fig. 7.

Fig. 6.

Results of FE quasi-static analysis of MV closure during ventricular systole

Fig. 7.

Parametric studies on preferred fiber directions and material anisotropy with increasing levels of fidelity from (a) to (c) (all cases are at the fully-loaded configurations)

4. Discussions

In this work, we developed a computational framework that incorporates the detailed collagen fiber architecture, utilizes the accurate constitutive models for valve tissues, and uses the micro-anatomically accurate MV geometry The proposed computational framework, allowing us to perform the quasi-static simulations of functional mitral valve in order to investigate the mechanical responses of MV under external physiological loadings. In this study, we hypothesize that the MV failures result from abnormally high stresses and the greatest tissue stresses occur at fully systolic loading and the MV tissues can be modeled by the function elastic material. Therefore, we performed the quasi-static analyses of MV closure events by neglecting the blood flow effect that is similar to the considerations in other research [16, 17]. The stress field obtained in the current study is in a similar order to other studies on the modeling of MV [17–19].

To the authors’ understanding, this is the first time to incorporate high-fidelity micro-structural detailed information with the constitutive model using the same specimen and species for numerical FE simulations of MV function, comparing to the existing study [15] which uses previously measured fiber architecture on the later numerical calculation that lacks the experimental data integrity and detailed mapping procedure. Finally, the MV deformations, leaflet regional strains, and collagen fiber architecture at various deformed configurations are carefully validated with the in-vitro experimental measurements.

Although invasive measurements are acquired in the current study, the proposed computational framework demonstrates the necessity of taking high fidelity into consideration for the numerical simulations, and it can be viewed as a population-based archival model model for future extension with a spline-based microstructural mapping technique [20] in (i) in-vivo predictive capabilities and calibration with the in-vivo data, (ii) patient-specific modelign, and (iii) optimal design of MV repair strategy and technique with improved performance and durability.

Acknowledgments.

This work was supported by the ICES Postdoctoral Fellowship (CH Lee) and the National Institute of Health grants (HL 63954, HL 72021, HL 103723, and HL110651). The help from Ronen Aniti, Young Lee, and Ted Weber is greatly appreciated.

References

- 1.Carpentier A: Cardiac valve surgery–the French correctoin. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg 86(3), 323–337 (1983) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldsmith IR, Lip GY, Patel RL: A prospective study of changes in the quality of life of patients following mitral valve repair and replacement. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg 20(5), 949–955 (2001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Driessen NJ, Boerboom RA, Huyghe JM, Bouten CV, Baaijens FP: Computational analyses of mechanically induced collagen fiber remodeling in the aortic heart valve. J. Biomech. Eng 125(4), 549–557 (2003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boerboom R, Driessen NB, Bouten CC, Huyghe J, Baaijens FT: Finite element model of mechanically induced collagen fiber synthesis and degradation in the aortic valve. Ann. Biomed. Eng 31(9), 1040–1053 (2003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kunzelman KS, Cochran RP, Chuong C, Ring WS, Verrier ED, Eberhart RD: Finite element analysis of the mitral valve. J. Heart Valve Dis 2(3), 326–340 (1993) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kunzelman KS, Reimink MS, Cochran RP: Flexible versus rigid ring annuloplasty for mitral valve annular dilatation: a finite element model. J. Heart Valve Dis 7(1), 108–116 (1998) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Einstein DR, Kunzelman KS, Reinhall PG, Nicosia MA, Cochran RP: The relationship of normal and abnormal microstructural proliferation to the mitral valve closure sound. J. Biomech. Eng 127(1), 134–147 (2005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sacks MS, Smith DB, Hiester ED: The aortic valve microstructure: Effects of transvalvular pressure. J. Biomed. Mater. Res 41(1), 131–141 (1998) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cochran RP, Kunzelman KS, Chuong CJ, Sacks MS, Eberhard RC: Nondestructive analysis of mitral valve collagen fiber orientation. ASAIO Trans. 37(3), M447–M448 (1991) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sacks MS: Incorporation of experimentally-derive fiber orientation into a structural constitutive model for planar collagenous tissues. J. Biomech. Eng 125(2), 280–287 (2003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gorman JH, Gupta KB, Streicher JT, Gorman RC, Jackson BM, Ratcliffe MB, Bogen DK, Edmunds LH Jr.: Dynamic three-dimensional imaging of the mitral valve and left ventricle by rapid sonomicrometry array localization. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg 112(3), 712–726 (1996) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grashow JS, Yoganathan AP, Sacks MS: Biaxial stress-stretch behavior of the mitral valve anterior leaflet at physiologic strain rates. Ann. Biomed. Eng 34(2), 315–325 (2006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He Z, Ritchie J, Grashow JS, Sacks MS, Yoganathan AP: In vitro dynamic strain behavior of the mitral valve posterior leaflet. J. Biomech. Eng 127(3), 504–511 (2005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kunzelmann KS, Cochran RP: Mechanical properties of basal and marginal mitral valve chordae tendineae. ASAIO Trans. 36, M405–M408 (1990) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kunzelman KS, Einstein DR, Cochran RP: Fluid-structure interaction models of the mitral valve: function in normal and pathological states. Phil. Trans. Soc. B 362, 1393–1406 (2007) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun W, Abad A, Sacks MS: Simulated bioprosthetic heart valve deformation under quasi-static loading. J Biomech. Eng 127, 1–9 (2005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prot V, Haaverstad R, Skallerud B: Finte element analysis of the mitral apparatus: annulus shape effect and chordae force distribution. Biomech. Model Mechanobiol 8, 43–55 (2009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lau KD, Diaz V, Scambler P, Burriesci G: Mitral valve dynamics in structure and fluid-structure interaction models. Med. Eng. Phys 32, 1057–1064 (2010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Q, Sun W: Finite element modeling of mitral valve dynamic deformation using patient-specific multi-slices computed tomography scans. Annals Biomed. Eng (2012), doi: 10.1007/s10439-012-0620-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aggarwal A, Aguilar VS, Lee CH, Gorman JH, Gorman RC, Sacks MS: Spline based microstructural mapping for soft biological tissues: application to aortic valves. In: 11th International Symposium on Computer Methods in Biomechanics and Biomedical Engineering (2013) [Google Scholar]