Abstract

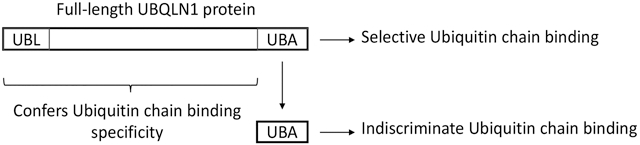

UBQLN proteins regulate proteostasis by facilitating clearance of misfolded proteins through the proteasome and autophagy degradation pathways. Consistent with its proteasomal function, UBQLN proteins contain both UBL and UBA domains, which bind subunits of the proteasome, including the S5a subunit, and ubiquitin chains, respectively. Conclusions regarding the binding properties of UBQLN proteins have been derived principally through studies of its individual domains, not the full-length (FL) proteins. Here we describe the in vitro binding properties of FL-UBQLN1 with the S5a subunit of the proteasome and two different lysine-linked (K48 or K63) ubiquitin chains. We show that in contrast to its isolated UBA domain, which binds almost equally well with both K48 and K63 ubiquitin chains, FL UBQLN1 binds preferentially with K63 chains. Furthermore, we show that deletion of the UBL domain from UBQLN1 abrogates ubiquitin binding. Taken together these results suggest that sequences outside of the UBA domain in UBQLN1 function to regulate the specificity and binding with different ubiquitin moieties. We also show that the UBL domain of UBQLN1 is required for S5a binding and that its binding to UBQLN1, in turn, enhances K48 ubiquitin chain binding to the complex. We discuss the implications of our findings with the known function of UBQLN proteins in protein degradation.

Keywords: Ubiquilin, UBQLN1, UBA domain, UBL domain, polyubiquitin

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Proteins that contain both UBL and UBA domains have been shown to play important roles in clearance of unwanted proteins from cells by binding and shuttling ubiquitinated proteins to the proteasome for degradation [1]. One such protein family are ubiquilins (UBQLN), which are highly conserved across species [2, 3].

Humans contain 4 highly related UBQLN proteins (UBQLN 1, 2, 3, and 4) that are approximately 600 amino acids in length [2, 4, 5]. The proteins are characterized by containing short highly conserved N- and C-terminal UBL and UBA domains, respectively, which have different functions. The UBA domain binds to ubiquitin chains typically conjugated onto proteins destined for destruction, whereas the UBL domain binds to the Rpn10(S5a) and Rpn13 receptors located in the 19S regulatory cap portion of the proteasome [6-12]. Through simultaneous binding with their respective targets, the two domains coordinate delivery of misfolded proteins to the proteasome for degradation. Besides these two domains, UBQLNs also contain a longer more variable central domain that has binding sites for different adaptors involved in its function. For example, the central domain contains a number of STI1 motifs that bind heat shock proteins and transmembrane-containing proteins [13-15]. The domain also contains binding sites for interaction with factors involved in ER-associated degradation [16, 17]. Consistent with a protein with these structural features, UBQLN proteins are known to function in protein quality control. They primarily function to regulate proteostasis by facilitating clearance of misfolded proteins from cells through both the proteasome and autophagy degradation pathways [4, 18-21]. They have also been shown to act as chaperones by shielding signal sequences and transmembrane domains of proteins during synthesis and to aid in protein refolding [14, 15, 22-24]. Recent findings also suggest UBQLN proteins may function in protein quality in stress granules [25, 26]. In accord with these important functions, mutations in UBQLN genes are linked to the cause a number of different neurodegenerative diseases [27-33].

The determinants by which UBQLNs direct proteins for degradation to either the ubiquitin-proteasome-system or the autophagy-lysosomal pathways remain unclear. One possibility is that the pathway selected for degradation is simply dictated by the types of ubiquitin linkages that are conjugated onto proteins with which they bind. For example, proteins degraded through the proteasome pathway typically carry K48 ubiquitin chains, whereas those that are degraded through the autophagy pathway are generally not tagged with K48 or other lysine-linked chains, but instead tagged with K63 ubiquitin chains [34-36].

There is considerable information regarding the binding specificity of UBQLN proteins with different ubiquitin moieties. However, this insight has largely been derived through studies of its isolated domains [6-10]. The studies have shown that the UBA domain is required for ubiquitin binding, but that it binds almost indiscriminately with very high affinity with almost all types of ubiquitin moieties tested, including mono ubiquitin and various ubiquitin-linked chains (K29, K48 and K63 linked chains)[9, 10]. However, it is possible that the ubiquitin-binding specificity may be different for full-length UBQLN proteins. To examine this possibility, we studied the binding properties of full-length and truncated forms of UBQLN1 proteins with K48 and K63 ubiquitin-chains using GST-pulldown assays. We demonstrate here that recombinant full-length UBQLN1 protein binds K63 ubiquitin chains with greater specificity than with K48 chains. Additionally, we demonstrate that full-length UBQLN1 can pulldown both types of ubiquitin chains as well as the S5a subunit of the proteasome, consistent with its function as a proteasome shuttle factor. We discuss the implications of these findings with regard to the known function of UBQLN proteins in cells.

Materials and Methods

Expression and purification of recombinant proteins

FL and different truncation (ΔUBL, ΔUBA, ΔUBLΔUBA) fragments of human UBQLN1 cDNA were expressed in BL21(DE3) bacteria as GST-fusion proteins and purified as described previously [8, 16]. Additionally, the Δ8 exon variant (UBQLN18i, kindly provided by Dr. Ming Guo, UCLA) and GST alone, were also expressed and purified from BL21(DE3) bacteria. Full-length human S5a proteasome subunit was expressed in BL21(DE3) bacteria and purified as a His-tagged protein [37].

GST-pulldown assays

GST fusion proteins were dialyzed against 20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, and 10% glycerol. Aliquots of the dialyzed proteins were frozen at −80°C until use. For the pulldown assays, ~10 μg amount of GST proteins were mixed with 100 μl of GST agarose beads and 800 μl of binding buffer (20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 3 mM MgCl and 0.1% Triton X-100). The proteins were rotated for 2 h at 4°C with the beads and then the beads were recovered by centrifugation, and then washed three times with binding buffer. Ligands tested for binding (2 μg) were then added to the washed beads and mixed by rotation at 4°C for 2h. The beads were then washed three times in binding buffer, resuspended in 50 mM Tris pH6.8 and adjusted to 1X with protein loading buffer [38]. The samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and either stained with Coomassie Blue to detect the added proteins or probed with primary and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies as described previously [39]. The results shown were faithfully reproduced in at least two independent experiments.

Antibodies and Reagents

K48 and K63 tetra and polyubquitin chains were purchased from Enzo Life Sciences (Farmingdale, NY). The following antibodies were used to detect the added proteins. Ubiquitin binding was detected with mouse monoclonal anti-ubiquitin (sc-8017) antibody from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. S5a-His proteins was detected with an anti-His antibody, and GST-UBQLN1 fusion proteins with either anti-UBQLN1 antibody (made in house [2]) or an anti-GST-fusion protein antibody also made in house (UM110 [40]).

Results

Full-length UBQLN1 binds stronger of K63-linked ubiquitin chains

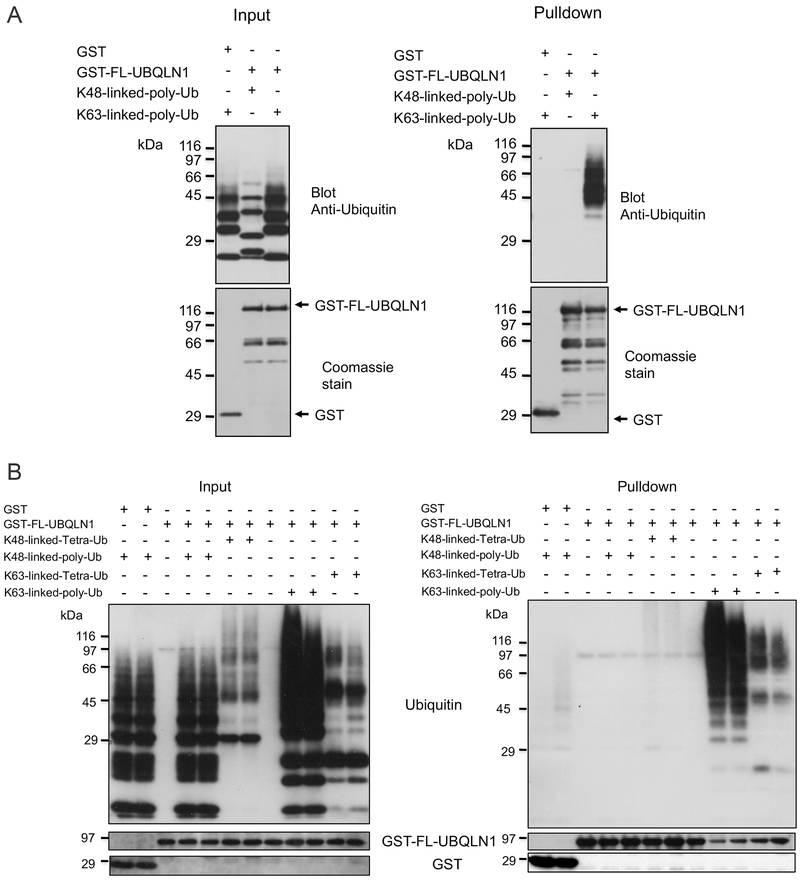

To investigate whether full-length UBQLN1 binds preferentially with different types of ubiquitin chains we expressed and purified full-length wild-type human UBQLN1 as a GST-fusion protein and used it to conduct in-vitro pulldown assays with either K48 or K63 polyubiquitin ubiquitin chains. The pulldown assays revealed that GST-FL-UBQLN1 binds strongly with K63 poly-ubiquitin chains but not with K48 poly-ubiquitin chains (Fig 1A). The specificity of K63 interaction with UBQLN1 is apparent from lack of binding of the chains with GST alone (Fig 1A). Interestingly, the K63 chains that were pulled down by UBQLN1 were principally the higher molecular weight forms, but not the lower molecular weight forms, suggesting a preference for binding longer K63 poly-ubiquitin chains.

Fig. 1. GST-FL-UBQLN1 binds preferentially to K63 compared to K48 ubiquitin chains.

A: Different lysine-linked (K48 or K63) poly ubiquitin chains were mixed with either GST-FL-UBQLN1 protein or with GST alone, as indicated, and a GST pulldown assay was conducted. Equal portions of the input or pulldown samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with an ant-ubiquitin antibody to detect the ubiquitin proteins that were added and that were pulled down. Also shown are Coomassie Blue stained gels of equal portions of the input and pulldown samples. B: Similar assay to that described in A, except this time tetra-linked K48 or K63 chains were also included in the assay, as indicated. Immunoblots (shown) were used to detect the different proteins contained in equal portion of the input and pulldown samples.

To verify the binding specificity for K63 chains we repeated the pulldown assays, but this time also included tetra ubiquitin chains in the assays (Fig 1B and Supplemental Fig 1S). Again, the GST pulldown assays revealed that full-length UBQLN1 GST-fusion protein binds strongly with both poly and tetra K63 ubiquitin chains, and negligibly with either poly or tetra-linked K48 ubiquitin chains.

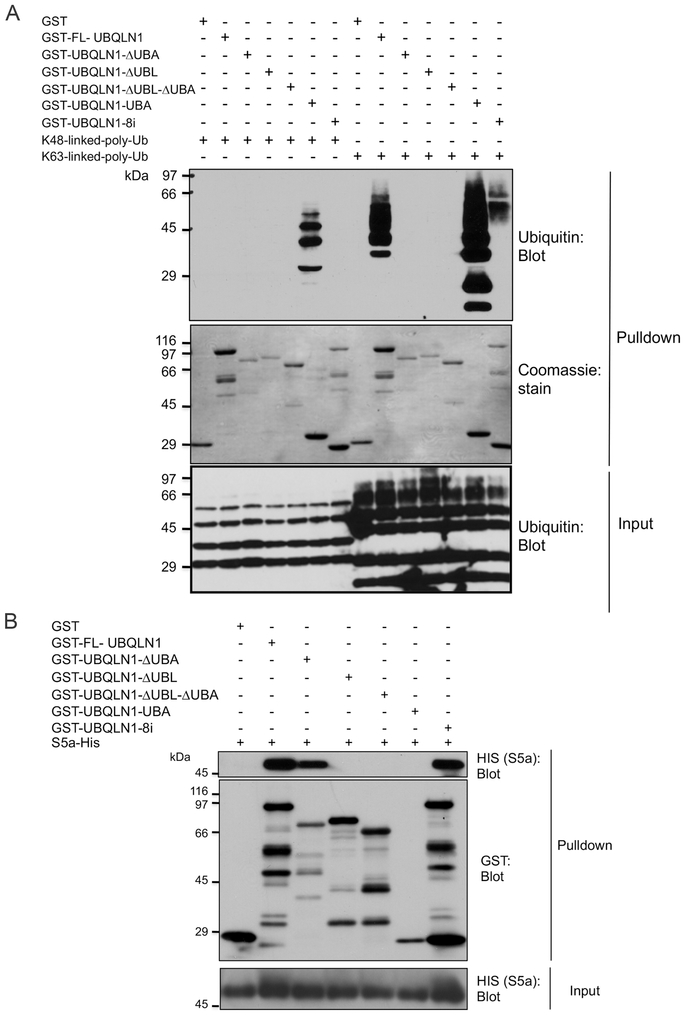

Discrimination in binding of K63 and K48 ubiquitin chains is relaxed upon truncation of UBQLN1 protein

Because previous studies had found the isolated UBA domain of UBQLN1 binds K48 and K63 chains with approximately equal affinity [9, 10] we next investigated whether its separation from the full-length protein would relax the discrimination seen with the latter for the two different ubiquitin linkages. Accordingly, we generated GST-fusion constructs expressing only the UBA domain of UBQLN1, or those missing the domain with or without the UBL domain. The purified GST-fusion proteins were used to assess binding with the K48 and K63 polyubiquitin chains in pulldown assays (Fig 2A and Supplemental Fig 2S). Similar to the previous result, FL-UBQLN1 fusion protein bound preferentially with K63 chains compared with K48 chains (Fig 1A and 2A). By contrast, the isolated UBA domain bound equally strongly with both K48 and K63 chains. Interestingly, more of the lower-molecular weight K63 chains were also pulled down by the isolated UBA domain, which were not brought down by the FL-UBQLN1 fusion protein, further suggesting its separation from the full-length protein relaxes length-dependent ubiquitin chain binding (Fig 2A). Analysis of the pulldown results for the remaining UBQLN1 deletion constructs revealed that deletion of the UBA, as expected, abrogates ubiquitin binding, as all constructs deleted of the domain failed to bind any of the ubiquitin chains. Unexpectedly, we also found that UBQLN1 fusion proteins deleted of only the UBL domain also failed to pull down any of the ubiquitin chains, although prolonged exposure of the blots indicated minor pulldown of K48 chains.

Fig. 2. The specificity of ubiquitin chain binding by UBQLN1 is governed by sequences in the full-length protein.

A: GST-fusion proteins expressing either the FL UBQLN1 polypeptide or deleted of either exon 8 (UBQLN1-8i), or the UBA domain, or the UBL domain, or both the UBA and UBL domains as well as GST alone were mixed with either K48 or K63 polyubiquitin chains, as indicated, and a GST pulldown experiment was conducted. The proteins contained in equal amounts of the input and pulldown samples were either analyzed for ubiquitin immunoreactivity or recovery of the GST proteins by Coomassie blue staining. Please note there is slight spillover of the K63 ubiquitin chains in the ΔUBLΔUBA lane due to its high recovery in by FL-UBLQN1. B: Pulldown assay using the same GST proteins used in A, except analyzed for S5a binding.

In these pulldown assays we also analyzed the binding ability of a UBQLN1 protein encoding the 8i variant, which has been linked to late-onset development of Alzheimer’s disease [41, 42] (Fig 2A). This variant generates a transcript that skips exon 8, encoding a polypeptide similar to WT UBQLN1 but missing one of the ST1 motifs. The pulldown assays revealed that the UBQLN18i-fusion protein displays similar K63 ubiquitin chain-binding specificity like that of WT UBQLN1, as K63 but not K48 chains were pulled down by the variant. Interestingly, more high molecular weight ubiquitin chains were pulled down by the UBQLN18i-fusion protein compared to WT UBQLN1.

Taken together the results suggest that the binding specificity of UBQLN1 with ubiquitin chains appears to be influenced by not only the UBA domain but by sequences contained in the rest of the UBQLN1 polypeptide, including the UBL domain.

The UBL domain of UBQLN1 binds the S5a subunit of the proteasome

The UBL domain of UBQLN1 has been shown to be required for binding the S5a subunit of the proteasome [7]. We therefore tested whether the GST-fusion proteins we had generated were capable of binding recombinant purified His-tagged S5a subunit using similar pulldown assays. As shown in Fig 2B, all of the UBQLN1 fusion proteins containing the UBL domain, including the 8i variant, were able to pulldown S5a. By contrast, those deleted of the UBL domain failed to pulldown the S5a subunit. The results confirmed the requirement of the UBL domain of UBQLN1 for binding the S5a subunit of the proteasome.

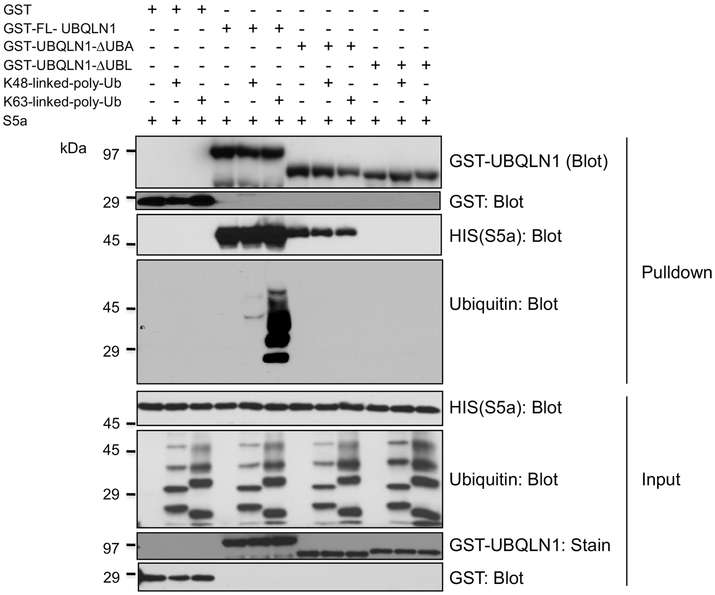

GST-UBQLN1 binds both the S5a subunit of the proteasome and ubiquitin chains

We next examined whether GST-fusion proteins expressing either FL UBQLN1, or portions of the protein that were deleted of either the UBA or UBL domains, could bind both the S5a proteasome subunit and K48 or K63 ubiquitin chains. Accordingly, each of the GST fusion proteins, or GST alone, were coincubated with the S5a and K48 or K63 ubiquitin chains and then the GST proteins were pulled down and analyzed for binding of the added proteins (Fig 3 and Supplemental Fig 3S). As expected, the S5a subunit was only pulled down by UBQLN1 fusion proteins containing an intact UBL domain, whereas the ubiquitin chains were only pulled down by the GST-FL-UBQLN1 (Fig 3). However, in contrast to the incubations done without S5a, when only K63 chains were pulled down, this time both K48 and K63 chains were pulled down. GST-FL-UBQLN1 protein pulled down abundant amounts of K63 chains, including more lower molecular weight species (Fig 3 and 3S). Interestingly, K48 chains were also pulled down, albeit considerably less than the K63 chains (Fig 3 and 3S). The results indicate that full-length UBQLN1, but not portions of it missing either its UBA or UBL domains are needed to bind both the S5a proteasome subunit and ubiquitin chains.

Fig. 3. Pulldown of both ubiquitin chains and the S5a subunit of the proteasome by GST-FL-UBQLN1 fusion protein.

GST-fusion proteins expressing either the FL UBQLN1 polypeptide, or deleted of either its UBA or UBL domains, or GST alone, were each incubated with recombinant purified S5a-HIS protein alone or together with either K48 or K64 polyubiquitin chains, as indicated, and then examined for binding of the S5a protein and the ubiquitin chains by GST pulldown assays. The different proteins in equal amounts of the input and pulldown samples are shown. Note S5a and K63 chains, and some K48 chains are pulldown only by GST-FL-UBQLN1 protein.

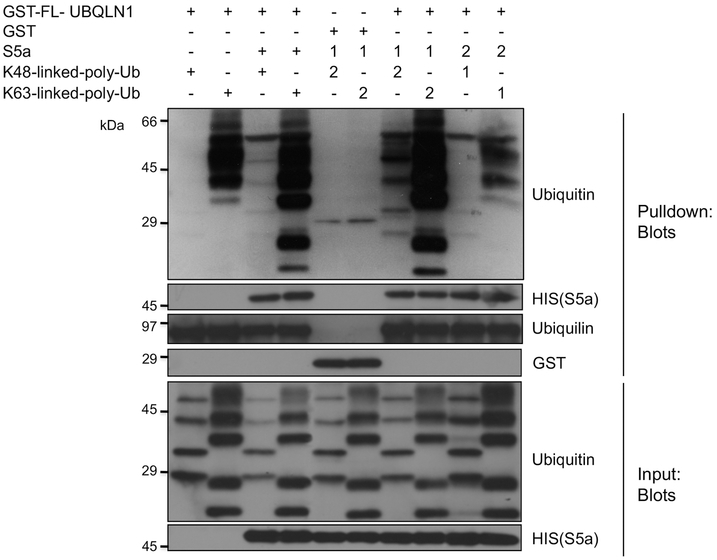

The sequence of S5a and ubiquitin chain addition determines GST-UBQLN1 pulldown of K48 ubiquitin chains

The preceding studies demonstrated that simultaneous addition of S5a and K48 ubiquitin chains somehow enhances pulldown of K48 ubiquitin chains with GST-UBQLN1 fusion protein. To determine if binding of K48 chains is influenced by the sequence of addition of the added proteins we conducted pulldown assays by first incubating GST-FL-UBQLN1 protein bound to GST-agarose beads with either S5a, or with K48 or K63 ubiquitin chains, then washed the beads and re-incubated them with the omitted protein. A binding assay was also conducted where all the proteins were coincubated together. A control was also performed to ensure there was no binding of the added proteins with GST alone. The results indicated that preincubation of GST-UBQLN1 with S5a enhances pulldown of K48 chains, and that this omission dramatically reduces the binding (Fig 4). By contrast, the order of S5a addition did not affect its recovery upon pulldown of GST-FL-UBQLN1, as its binding was independent of ubiquitin chain addition. Neither of the added proteins were pulled down by the negative GST control, irrespective of the order of addition, attesting to the specificity of binding of the proteins with UBQLN1.

Fig. 4. S5a binding to GST-FL-UBQLN1 in turn enhances binding with K48 and K63 ubiquitin chains.

A sequential pulldown experiment was performed where GST-FL-UBQLN1 was either coincubated with S5a and either K48 or K63 polyubiquitin chains or where it was first incubated with S5a subunit and then with the ubiquitin chains (Sequence 1), or in reverse order (Sequence 2). GST alone was only used for the pulldown using the Sequence 1 protocol. The proteins present in the input and following recovery from these pulldown experiments were identified by immunoblotting or Coomassie blue staining, as shown. Note that prebinding of S5a with UBQLN1 enhances K48 chain pulldown.

Discussion

Here we have shown, using in-vitro GST pulldown assays using purified proteins, that FL-UBQLN1 binds and forms a complex with both the S5a subunit of the proteasome as well as with ubiquitin chains, consistent with its role as a shuttle factor that binds and delivers ubiquitin-tagged proteins for proteasomal degradation. Unlike previous studies we found that in the absence of any other protein, FL-UBQLN1 binds more strongly with K63 ubiquitin chains than with K48 chains. Furthermore, we show that binding of S5a with FL-UBQLN1, in turn, enhances binding with K48 ubiquitin chains. The modulation and differential binding of UBQLN1 with different ubiquitin chains could be important in influencing the pathway that UBQLN1 participates during its function in signaling, trafficking, and/or proteasome degradation.

The preferential binding of FL-UBQLN1 with K63 chains compared with K48 chains is particularly noteworthy considering we found the isolated UBA domain of UBQLN1 binds indiscriminately with the same two types of ubiquitin linkages, including lower molecular weight forms that were not pulled down by the FL UBQLN1 protein. Similar findings regarding the indiscriminate binding of the isolated UBA of UBQLN1 with different ubiquitin moieties, including K48 and K63 chains, were reported previously [9, 10]. An obvious question is why does the FL protein differ from the UBA fragment in ubiquitin-chain binding properties? A likely explanation we believe is sequences besides the UBA domain within the full-length protein regulates the specificity of ubiquitin binding. Consistent with this idea, we found that deletion of the UBL domain from UBQLN1, which is primarily involved in binding the S5a subunit of the proteasome, almost completely abolished K48 and K63 ubiquitin chain binding. This finding also suggests that the UBL domain may function in a structural capacity within the UBQLN1 polypeptide to support ubiquitin binding to the UBA domain and that deletion of it may cause a large structural perturbation of the remaining polypeptide that blocks ubiquitin chain binding. Our results highlight the pitfalls with performing binding and or functional studies using deleted or isolated domains of UBQLN proteins as they could lead to erroneous conclusions when compared to the full-length protein.

With the same caution, we also realize that our conclusions are derived entirely from the use of GST-fusion proteins, of which there is some evidence the GST portion of the fusion can influence the binding preference of ubiquitin moieties [43]. For example, Sims et al., [43] found that fusion of GST can increase binding affinity of UBA domains for K63 polyubiquitin chains over K48 chains; however, in their studies, the contribution of GST was only studied in the context of the isolated UBA domains, not with respect to the full-length protein. Additionally, the UBA domain of UBQLN1 when used in GST pulldown assays bound K63 and K48 chains with similar affinity [9, 10], which is what we found in our assays, unlike the preference for K63 chains seen by Sims et al. [43].

If the preferential binding of FL UBQLN1 with K63 ubiquitin chains occurs in vivo, it may suggest that UBQLN1 proteins are normally poised to bind proteins tagged with K63 ubiquitin linkages, which are typically involved in cell signaling and protein trafficking, such as in NFκB signaling and autophagy. Interestingly, UBQLN proteins have been linked to NFκB signaling as well as in autophagy [4, 44] [20], which may be related to its ability to bind K63 ubiquitin chains. By contrast to the strong binding seen with K63 chains, we found FL UBQLN1 binds weakly with K48 ubiquitin chains, which is the typical ubiquitylation signal involved in proteasomal degradation. Interestingly however, we found K48 chain binding with UBQLN1 is enhanced by interaction of S5a with UBQLN1. The S5a subunit contains two UIM domains that can bind ubiquitin or UBL domains in shuttle receptors like UBQLN proteins. The C-terminal UIM domain in S5a binds ubiquitin 10-fold stronger than the N-terminal UIM domain [45], whereas the N-terminal UIM domain binds more strongly with the UBL domain of UBQLN1 and 2 proteins [6, 12, 46]. Thus, binding of S5a with UBQLN1 in a complex may increase binding with K48 ubiquitin chains through several possible mechanisms. One possibility is S5a binding to UBQLN1 induces a structural change in UBQLN1 enabling increased accessibility to the UBA domain of UBQLN1 to bind K48 chains. Additionally there is the possibility that UBQLN proteins may first bind proteins tagged with K63 linkages, which could subsequently be tagged with K48 ubiquitin linkages for proteasomal degradation. This idea would fit with the recent data showing K63 ubiquitination may serve as a seed for nucleating K48 ubiquitination, leading to mixed ubiquitin chain assembly [47], showing that complexity of ubiquitin chain involvement in protein degradation is more complicated than first envisaged.

While our studies have focused on UBQLN1 proteins that were recombinantly expressed in bacteria, the possibility exists that the properties of the proteins could also be regulated by post-translational modification or by alternate splicing of the proteins that occurs in eukaryotes in vivo. We examined if alternate splicing could affect UBQLN1 function by studying the delta exon 8 isoform of UBQLN1, encoding the variant that has been linked to late-onset AD, but found it has similar binding preference for K63 ubiquitin chains as WT UBQLN1, although the 8i isoform displayed a greater tendency to bind higher molecular weight ubiquitin chains. It will be interesting in the future to determine if changes in splicing and post-translational modification of UBQLN proteins are involved in regulating their function(s) and how UBQLN proteins function in ubiquitin chain binding and degradation.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Ubiquilin proteins facilitate clearance of ubiquitinated proteins from cells.

We examined whether UBQLN1 discriminates binding with different ubiquitin chains.

Full-length and UBQLN1 fragments display differences in ubiquitin chain-binding.

We show UBQLN1 binds both ubiquitin chains and the S5a proteasome subunit.

S5a binding to UBQLN1 enhances K48 ubiquitin chain-binding.

Acknowledgements

This work was support in part by NIH grants R01NS098243 and R01NS100008 to MJM.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- [1].Elsasser S, Finley D, Delivery of ubiquitinated substrates to protein-unfolding machines, Nat Cell Biol, 7 (2005) 742–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Mah AL, Perry G, Smith MA, Monteiro MJ, Identification of ubiquilin, a novel presenilin interactor that increases presenilin protein accumulation, J Cell Biol, 151 (2000) 847–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Wu AL, Wang J, Zheleznyak A, Brown EJ, Ubiquitin-related proteins regulate interaction of vimentin intermediate filaments with the plasma membrane, Mol Cell, 4 (1999) 619–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Rothenberg C, Monteiro MJ, Ubiquilin at a crossroads in protein degradation pathways, Autophagy, 6 (2010) 979–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Marin I, The ubiquilin gene family: evolutionary patterns and functional insights, BMC Evol Biol, 14 (2014) 63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Walters KJ, Kleijnen MF, Goh AM, Wagner G, Howley PM, Structural studies of the interaction between ubiquitin family proteins and proteasome subunit S5a, Biochemistry, 41 (2002) 1767–1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ko HS, Uehara T, Tsuruma K, Nomura Y, Ubiquilin interacts with ubiquitylated proteins and proteasome through its ubiquitin-associated and ubiquitin-like domains, FEBS Lett, 566 (2004) 110–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Massey LK, Mah AL, Ford DL, Miller J, Liang J, Doong H, Monteiro MJ, Overexpression of ubiquilin decreases ubiquitination and degradation of presenilin proteins, J Alzheimers Dis, 6 (2004) 79–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Raasi S, Varadan R, Fushman D, Pickart CM, Diverse polyubiquitin interaction properties of ubiquitin-associated domains, Nat Struct Mol Biol, 12 (2005) 708–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Zhang D, Raasi S, Fushman D, Affinity makes the difference: nonselective interaction of the UBA domain of Ubiquilin-1 with monomeric ubiquitin and polyubiquitin chains, J Mol Biol, 377 (2008) 162–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hamazaki J, Hirayama S, Murata S, Redundant Roles of Rpn10 and Rpn13 in Recognition of Ubiquitinated Proteins and Cellular Homeostasis, PLoS Genet, 11 (2015) e1005401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Chen X, Ebelle DL, Wright BJ, Sridharan V, Hooper E, Walters KJ, Structure of hRpn10 Bound to UBQLN2 UBL Illustrates Basis for Complementarity between Shuttle Factors and Substrates at the Proteasome, J Mol Biol, 431 (2019) 939–955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kaye FJ, Modi S, Ivanovska I, Koonin EV, Thress K, Kubo A, Kornbluth S, Rose MD, A family of ubiquitin-like proteins binds the ATPase domain of Hsp70-like Stch, FEBS Lett, 467 (2000) 348–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kurlawala Z, Shah PP, Shah C, Beverly LJ, The STI and UBA Domains of UBQLN1 Are Critical Determinants of Substrate Interaction and Proteostasis, J Cell Biochem, 118 (2017) 2261–2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Suzuki R, Kawahara H, UBQLN4 recognizes mislocalized transmembrane domain proteins and targets these to proteasomal degradation, EMBO Rep, 17 (2016) 842–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lim PJ, Danner R, Liang J, Doong H, Harman C, Srinivasan D, Rothenberg C, Wang H, Ye Y, Fang S, Monteiro MJ, Ubiquilin and p97/VCP bind erasin, forming a complex involved in ERAD, J Cell Biol, 187 (2009) 201–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Xia Y, Yan LH, Huang B, Liu M, Liu X, Huang C, Pathogenic mutation of UBQLN2 impairs its interaction with UBXD8 and disrupts endoplasmic reticulum-associated protein degradation, J Neurochem, 129 (2014) 99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].N'Diaye EN, Kajihara KK, Hsieh I, Morisaki H, Debnath J, Brown EJ, PLIC proteins or ubiquilins regulate autophagy-dependent cell survival during nutrient starvation, EMBO Rep, 10 (2009) 173–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Rothenberg C, Srinivasan D, Mah L, Kaushik S, Peterhoff CM, Ugolino J, Fang S, Cuervo AM, Nixon RA, Monteiro MJ, Ubiquilin functions in autophagy and is degraded by chaperone-mediated autophagy, Hum Mol Genet, 19 (2010) 3219–3232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Lee DY, Brown EJ, Ubiquilins in the crosstalk among proteolytic pathways, Biol Chem, 393 (2012) 441–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Senturk M, Lin G, Zuo Z, Mao D, Watson E, Mikos AG, Bellen HJ, Ubiquilins regulate autophagic flux through mTOR signalling and lysosomal acidification, Nat Cell Biol, 21 (2019) 384–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Matsuda M, Koide T, Yorihuzi T, Hosokawa N, Nagata K, Molecular cloning of a novel ubiquitin-like protein, UBIN, that binds to ER targeting signal sequences, Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 280 (2001) 535–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Stieren ES, El Ayadi A, Xiao Y, Siller E, Landsverk ML, Oberhauser AF, Barral JM, Boehning D, Ubiquilin-1 is a molecular chaperone for the amyloid precursor protein, J Biol Chem, 286 (2011) 35689–35698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Itakura E, Zavodszky E, Shao S, Wohlever ML, Keenan RJ, Hegde RS, Ubiquilins Chaperone and Triage Mitochondrial Membrane Proteins for Degradation, Mol Cell, 63 (2016) 21–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Dao TP, Kolaitis RM, Kim HJ, O'Donovan K, Martyniak B, Colicino E, Hehnly H, Taylor JP, Castaneda CA, Ubiquitin Modulates Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation of UBQLN2 via Disruption of Multivalent Interactions, Mol Cell, 69 (2018) 965–978 e966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Alexander EJ, Ghanbari Niaki A, Zhang T, Sarkar J, Liu Y, Nirujogi RS, Pandey A, Myong S, Wang J, Ubiquilin 2 modulates ALS/FTD-linked FUS-RNA complex dynamics and stress granule formation, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 115 (2018) E11485–E11494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Deng HX, Chen W, Hong ST, Boycott KM, Gorrie GH, Siddique N, Yang Y, Fecto F, Shi Y, Zhai H, Jiang H, Hirano M, Rampersaud E, Jansen GH, Donkervoort S, Bigio EH, Brooks BR, Ajroud K, Sufit RL, Haines JL, Mugnaini E, Pericak-Vance MA, Siddique T, Mutations in UBQLN2 cause dominant X-linked juvenile and adult-onset ALS and ALS/dementia, Nature, 477 (2011) 211–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Williams KL, Warraich ST, Yang S, Solski JA, Fernando R, Rouleau GA, Nicholson GA, Blair IP, UBQLN2/ubiquilin 2 mutation and pathology in familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Neurobiol Aging, 33 (2012) 2527 e2523–2510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Gonzalez-Perez P, Lu Y Chian RJ, Sapp PC, Tanzi RE, Bertram L, McKenna-Yasek D, Gao FB, Brown RH Jr., Association of UBQLN1 mutation with Brown-Vialetto-Van Laere syndrome but not typical ALS, Neurobiol Dis, 48 (2012) 391–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Fahed AC, McDonough B, Gouvion CM, Newell KL, Dure LS, Bebin M, Bick AG, Seidman JG, Harter DH, Seidman CE, UBQLN2 mutation causing heterogeneous X-linked dominant neurodegeneration, Ann Neurol, 75 (2014) 793–798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Scotter EL, Smyth L, Bailey J, Wong CH, de Majo M, Vance CA, Synek BJ, Turner C, Pereira J, Charleston A, Waldvogel HJ, Curtis MA, Dragunow M, Shaw CE, Smith BN, Faull RLM, C9ORF72 and UBQLN2 mutations are causes of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in New Zealand: a genetic and pathologic study using banked human brain tissue, Neurobiol Aging, 49 (2017) 214 e211–214 e215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Teyssou E, Chartier L, Amador MD, Lam R, Lautrette G, Nicol M, Machat S, Da Barroca S, Moigneu C, Mairey M, Larmonier T, Saker S, Dussert C, Forlani S, Fontaine B, Seilhean D, Bohl D, Boillee S, Meininger V, Couratier P, Salachas F, Stevanin G, Millecamps S, Novel UBQLN2 mutations linked to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and atypical hereditary spastic paraplegia phenotype through defective HSP70-mediated proteolysis, Neurobiol Aging, 58 (2017) 239 e211–239 e220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Edens BM, Yan J, Miller N, Deng HX, Siddique T, Ma YC, A novel ALS-associated variant in UBQLN4 regulates motor axon morphogenesis, Elife, 6 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Akutsu M, Dikic I, Bremm A, Ubiquitin chain diversity at a glance, J Cell Sci, 129 (2016) 875–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Komander D, Rape M, The ubiquitin code, Annu Rev Biochem, 81 (2012) 203–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Yau R, Rape M, The increasing complexity of the ubiquitin code, Nat Cell Biol, 18 (2016) 579–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Chang L, Monteiro MJ, Defective Proteasome Delivery of Polyubiquitinated Proteins by Ubiquilin-2 Proteins Containing ALS Mutations, PLoS One, 10 (2015) e0130162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Monteiro MJ, Mical TI, Resolution of kinase activities during the HeLa cell cycle: identification of kinases with cyclic activities, Exp Cell Res, 223 (1996) 443–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Le NT, Chang L, Kovlyagina I, Georgiou P, Safren N, Braunstein KE, Kvarta MD, Van Dyke AM, LeGates TA, Philips T, Morrison BM, Thompson SM, Puche AC, Gould TD, Rothstein JD, Wong PC, Monteiro MJ, Motor neuron disease TDP-43 pathology, and memory deficits in mice expressing ALS-FTD-linked UBQLN2 mutations, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 113 (2016) E7580–E7589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Stabler SM, Ostrowski LL, Janicki SM, Monteiro MJ, A myristoylated calcium-binding protein that preferentially interacts with the Alzheimer's disease presenilin 2 protein, J Cell Biol, 145 (1999) 1277–1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Bertram L, Hiltunen M, Parkinson M, Ingelsson M, Lange C, Ramasamy K, Mullin K, Menon R, Sampson AJ, Hsiao MY, Elliott KJ, Velicelebi G, Moscarillo T, Hyman BT, Wagner SL, Becker KD, Blacker D, Tanzi RE, Family-based association between Alzheimer's disease and variants in UBQLN1, N Engl J Med, 352 (2005) 884–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Haapasalo A, Viswanathan J, Bertram L, Soininen H, Tanzi RE, Hiltunen M, Emerging role of Alzheimer's disease-associated ubiquilin-1 in protein aggregation, Biochem Soc Trans, 38 (2010) 150–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Sims JJ, Haririnia A, Dickinson BC, Fushman D, Cohen RE, Avid interactions underlie the Lys63-linked polyubiquitin binding specificities observed for UBA domains, Nat Struct Mol Biol, 16 (2009) 883–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Picher-Martel V, Dutta K, Phaneuf D, Sobue G, Julien JP, Ubiquilin-2 drives NF-kappaB activity and cytosolic TDP-43 aggregation in neuronal cells, Mol Brain, 8 (2015) 71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Young P, Deveraux Q, Beal RE, Pickart CM, Rechsteiner M, Characterization of two polyubiquitin binding sites in the 26 S protease subunit 5a, J Biol Chem, 273 (1998) 5461–5467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Ko HS, Uehara T, Nomura Y, Role of ubiquilin associated with protein-disulfide isomerase in the endoplasmic reticulum in stress-induced apoptotic cell death, J Biol Chem, 277 (2002) 35386–35392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Ohtake F, Tsuchiya H, Saeki Y, Tanaka K, K63 ubiquitylation triggers proteasomal degradation by seeding branched ubiquitin chains, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 115 (2018) E1401–E1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.