Introduction

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic, allergy/immune-mediated disease diagnosed in patients with symptoms of esophageal dysfunction, an esophageal eosinophilic infiltrate, and without potential competing causes of eosinophilia.1 While EoE is classified as a rare disease with <200,000 affected in the United States,2, 3 the incidence and prevalence are rising, with rates outpacing increases in endoscopic detection.2, 4 The estimated prevalence is approximately 1 in 2000, with up to 150,000 cases in the U.S.3 In many patients, the condition can progress from a primarily inflammatory process to a fibrostenotic process, resulting in esophageal strictures, narrowing, and a need for dilation.5–7 Anti-inflammatory treatments include proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), swallowed topical corticosteroids (tCS), and dietary elimination,8, 9 but newer modalities such as biologics targeting the known pathogenesis of EoE are emerging.10, 11 Because the disease is chronic and recurs if treatments are stopped, ongoing maintenance therapy is needed in the majority of patients.12 Currently available paradigms for monitoring of biologic disease activity (endoscopic appearance and histologic features), require upper endoscopy with biopsy. For all of these reasons, the cost related to EoE are substantial, ~$1 billion annually in the U.S.13 However, there is relatively scant literature examining either the costs related to EoE or the approach to cost-effective care for the EoE patient.14 The goals of this review are to examine costs related to EoE, understand the source of these costs, discuss a possible approach for cost-effective care in EoE, and identify areas for future research in this topic.

Costs related to EoE

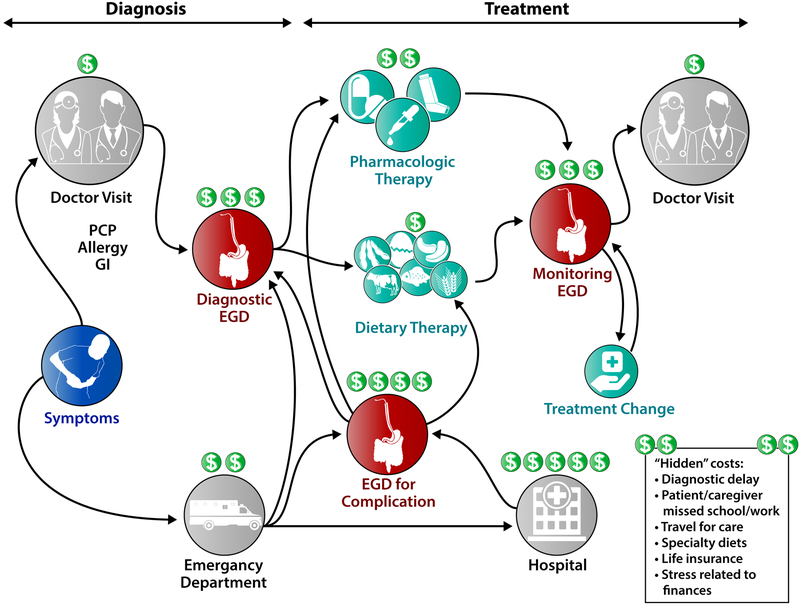

There are multiple costs related to EoE (Figure 1). Diagnostic costs include initial doctor visits for evaluation of symptoms and initial radiologic or endoscopic evaluation. If symptoms are severe and an esophageal food bolus impaction occurs, there will also be costs related to the emergency department visit, and possibly hospitalization. After diagnosis, costs are related to treatment, repeated endoscopic monitoring exams to assess and optimize treatment response, and doctor visits. These costs are obvious to both patients and providers. However, there are also “hidden” costs of EoE care, costs that are not picked up in traditional analyses and are as of yet to be fully quantified. These include costs related to diagnostic delay (due to patient or physician lack of awareness, or patients using compensatory behaviors to minimize symptoms), missed school or work for the patient as well as caregivers/family/friends who accompany the patient to clinic visits or endoscopy appointments, or missed school or work because of comorbid psychiatric diagnoses.15 There are also costs due to travel to centers that have expertise in EoE and other eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases (EGIDs), time and money spent shopping for specialty diets, and impact on insurance status. For example, a study by Leiman and colleagues found that life insurance policies were significantly more expensive in adults with EoE seeking life insurance compared to age-, sex-, and health-matched controls without EoE, despite the fact there are no objective data suggesting EoE decreases lifespan.16 Additionally, Hiremath and colleagues conducted a needs assessment study and reported that EoE and EGID patients and caregivers identified stress due to high medical costs and lack of insurance coverage for certain treatments as major areas of concern.17

Figure 1.

Points in the diagnostic and treatment algorithm where high costs are generated for EoE.

There are some studies that have quantified EoE costs (all costs below are in US$). Jensen and colleagues performed an analysis of a large claims database and identified more than 8,000 EoE cases and 32,000 controls.13 Median annual allowed costs, the amount covered by insurance as well as the amount required from patients (e.g. co-pays, deductibles, or co-insurance fees), were approximately $3,300 for EoE compared to $1,000 for non-EoE controls, indicating that EoE-attributable costs were $2,300/year. When assessing the source of these costs, on average (across the entire population of EoE cases identified) approximately $2,500 were for outpatient visits, $325 for pharmacy claims, and $160 for endoscopy, all substantially higher than non-EoE control ($700, $80, and $0, respectively). Overall, costs approached or exceeded $1 billion, annually, a tremendous amount for a rare disease, and comparable to expenditures for more common conditions.18 In this study, the large majority of EoE cases were adults (~80%), but in children under the age of 18, costs were about 25% higher, likely driven by higher endoscopy costs (hospital-based procedures; requirement for general anesthesia). Data presented by Schwartz and colleagues in abstract form corroborates the high costs of care in children with EoE.19 This study calculated actual hospital charges and physicians fees (rather than payments received) from a sample of patients at a single center, and found the cost of initial diagnosis was $18,800. Several studies have used the National Inpatient Sample to assess costs related to EoE patients who present to emergency departments with food impactions and require hospitalizations.20, 21 These data, reported in abstract form, show costs ranging from $14,000 to more than $18,000 for relatively short hospitalizations (median <2 days). Two other studies analyzing the same database, also presented as abstracts, looked at total inpatient EoE costs for any reason, and these exceeded a median of $20,000 (Eke),22 and demonstrated rising costs of hospitalizations for EoE over time (Solanki).23 While these costs are very high on a per-patient basis, it is important to realize that inpatient claims in EoE are relatively uncommon. In the Jensen study, the median overall number of claims for EoE patients was 67 (significantly higher than then median of 34 for non-EoE controls; p<0.001), while the median number of inpatient claims was actually zero.13

There are also more granular data on costs of EoE therapy. As there are currently no FDA-approved treatments for EoE, current pharmacologic strategies are used off-label and therefore it is unpredictable whether these medications will be covered by insurance. While over-the-counter PPIs are relatively inexpensive, swallowed tCS are quite expensive. Wholesale cost for a single fluticasone inhaler (120 actuations of 220 mcg) is approximately $390, and for initial dosing in adults (880 mcg BID) two inhalers are required per month. Full retail cost for a one month supply of aqueous budesonide respules at a starting dose of 1 mg BID (120 0.5mg/2mL vials) is approximately $1100.24 While some coupons may help individual patient pay lower out of pocket costs, using a range of sources, one study estimated the actual median quarterly cost of fluticasone to be $690 and budesonide to be $2300.25 If approved by insurance co-pays may vary (and the time spent on approval is another hidden cost on the provider side), but patients without a prescription plan or with a high-deductible plan may be responsible for these full costs, making obtaining these medications difficult to impossible. Dietary therapy is also not “free”. In a study by Wolf and colleagues, secret shoppers went to different groceries to price dietician-developed menus for the six-food elimination diet (SFED) where dairy, wheat, egg, soy, nuts, and seafood are removed, as well as a regular non-elimination diet. SFED was significantly more expensive than a regular diet on a weekly basis, and added nearly $700 annually to the grocery bill.26 Moreover, a trip to at least 2 different stores was required in order to purchase all of the needed ingredients and specialty foods. These costs would be multiplied if multiple family members were also try to comply with this diet to support the patient. In the Schwartz study, estimated total first-year patient-level costs from tCS, SFED, and elemental formula were approximately $20,000, $80,000, and $60,000, respectively (including all required treatments, doctor visits, and testing).19 Notably, elemental formulas are only covered by insurance in a minority of states in the U.S., and some require enteral feeding for coverage to be enacted.27

There are several reasons for these very high costs. EoE can be difficult to diagnose, requiring multiple doctor visits and ultimately necessitating upper endoscopy with biopsy. There are no FDA approved treatments, existing pharmacologic treatments are expensive and must be used chronically, and insurance may not cover treatments that do not have an indication for EoE. Foods required for dietary elimination are more expensive than a non-medical diet, and these costs are invisible to claims data analyses since food costs (and in many cases elemental formula costs) are not paid for by insurance. Endoscopy, an expensive invasive test, is used to obtain esophageal biopsies to monitor therapeutic response and assess disease activity. While outpatient procedures (often done in adults) add costs, in children where procedures are performed with general anaesthesia in a hospital setting, costs are even higher. Finally, complications of EoE, particularly esophageal food bolus impactions necessitating an emergency department visit, urgent endoscopy, or hospitalization, results in substantial expense.

Practicing cost-effective EoE care

Given the high costs related to EoE, it is important to consider how to best provide cost-effective care, but there are few studies to provide guidance. In cost-effectiveness studies, different perspectives are used which can inform the methods, the costs that are included, and the acceptable thresholds. These typically include payer perspectives, societal perspectives, and patient perspectives, though others are also possible. In an early exploration of this topic, Miller and colleagues used a 5-year Markov model from a third-party payer perspective to assess the diagnostic yield of esophageal biopsies for EoE in patients with symptoms of PPI-refractory GERD.28 They found that obtaining esophageal biopsies in this setting was only cost-effective if the expected prevalence of EoE was at least 8% in the population of interest (PPI-refractory GERD symptoms), a proportion that has been seen in children, but not in adults.2, 29 In contrast, esophageal biopsies will detect EoE in patients with dysphagia in at least 15% of subjects.2, 30, 31 Another cost-effectiveness study conducted by Kavitt and colleagues addressed the question of initial treatment of EoE.32 They modelled whether a patient who has not responded to PPI and remains symptomatic should receive fluticasone followed by dilation if symptoms persist, or dilation alone followed by fluticasone if symptoms persist. Costs for both approaches were similar (about $1100), but on sensitivity analysis initial treatment with fluticasone was more cost-effective if symptom response rates were greater than 62%. Cotton and colleagues performed a cost-utility analysis of tCS vs SFED for treatment of EoE patients who were non-responsive to PPI.25 Their model was constructed to reflect typical clinical care pathways, and included costs related to serial endoscopies for identifying food triggers, crossover between treatments for non-response to the initial therapy choice, and endoscopic dilation as a “rescue” therapy if neither treatment were effective. SFED and tCS (both budesonide and fluticasone were analyzed) had roughly similar efficacy for histologic response, but contrary to the authors’ hypothesis, SFED was more cost-effective than tCS at a 5 year time horizon. Though SFED required up to 7 endoscopies upfront, the long term costs of SFED (from the payer perspective and not accounting for increased grocery costs as noted above) were minimal compared to the fixed and high long-term costs of tCS. Data presented in abstract form have corroborated this finding.33 Limitations of these studies include relatively scant outcome data, a number of assumptions built into the model and the input data, no formal utility metrics available for EoE, and the fact that this study was conducted from the payer perspective rather than the societal or patient perspective (as analyses from these perspectives could provide different results).

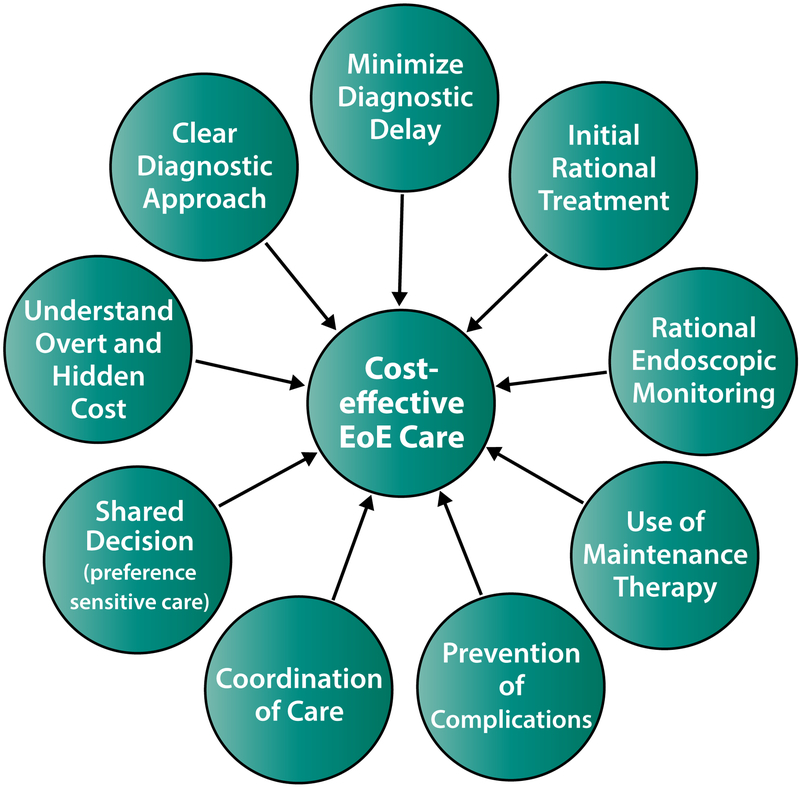

In this setting, and with a relative dearth of data, what is a framework for practicing cost-effective EoE care? There are several principles, though these remain to be tested clinically (Figure 2). The first is to have a rational diagnostic and therapeutic approach with clear goals of therapy for which practitioners and patients are aligned. This should allow provision of more efficient care. Suspecting EoE as a diagnostic possibility is crucial at the outset to minimize diagnostic delay,34 as early diagnosis and treatment may well prevent costly complications but will also eliminate the need for multiple visits to different providers prior to diagnosis. During the diagnostic process, it is important to follow guidelines.1, 35, 36 Incorrect diagnoses or situations where there may be competing diagnostic conditions (most notably gastroesophageal reflux disease [GERD]) would tend to increase costs. Equally important from this author’s perspective is the selection of a single initial therapy with subsequent assessment of symptomatic, endoscopic, and histologic response. At the time of initial diagnosis, particularly in a patient who is highly symptomatic or is suffering adverse consequences from EoE, there might be a temptation to start with multiple therapies at once. However, there are few studies of combination therapy,37 the majority of patients respond to a single agent (~50% to initial treatment with PPIs; ~60–70% to tCS or SFED in patients who have not responded to PPI),38–40 and if multiple treatments are started at once, it is not possible to know which one is responsible for a response. However, studies of single compared to multiple initial treatments are needed, including those stratifying patients based on severity of disease at the time of presentation. For those patients beginning with dietary elimination, targeted elimination diets based on allergy tests such as skin-prick test or food-specific serum IgE levels are less effective than empiric elimination,41, 42 and if testing-directed diet is selected first there is a higher likelihood of non-response and increased costs. Monitoring response after treatment changes, typically with endoscopy, may also be cost-effective. Because symptoms only modestly correlate with histologic disease activity,43 and because it is felt that ongoing eosinophilic inflammation is the major risk factor for progression to fibrostenosis,2, 5–7 ensuring an endoscopic and histologic response to treatment in addition to a symptomatic response confirms the most effective treatment is being used and allows treatment to be changed if it is ineffective. Additionally, having comorbid atopic diseases in EoE patients evaluated and treated by an allergist is an important component of EoE care,44, 45 though whether this is cost-effective has not been studied.

Figure 2.

Components of cost-effective care in EoE.

The second principle is to use effective maintenance therapy for disease control and ideally to prevent complications, however a formal analysis has not been performed on this topic. EoE is chronic, and disease activity returns after treatment is stopped,2, 46, 47 but more research is needed to identify the spectrum of minimally necessary therapy, which could significantly impact costs. While it might be appealing to treat patients only when they are symptomatic, if recurrent symptoms are manifest by a food bolus impaction requiring an urgent endoscopy and hospital stay, then high costs are conferred. While there are relatively few data on maintenance therapy for topical steroids,12, 47–51 histologic response has been associated with a decreased need for future esophageal dilation,52 a procedure that increases the cost of endoscopy. Barriers to long-term use of steroids may be related to side effects, including oral and esophagus candidiasis,8 concern about potential adrenal insufficiency or growth suppression/bone health,53 and more long-term safety data are needed. Some patients have concerns about long-term PPI use as well, though many of the recently reported associations are controversial and likely overstated.54 For dietary elimination, long-term adherence is an issue, and non-adherence can lead to disease flares.55 Barriers to adherence include perceived efficacy of the diet, challenges of maintaining the diet in social situations, and anxiety related to the diet.56

A third principle involves the approach to monitoring therapy. It makes sense to perform endoscopy to monitor the outcomes from initial therapy as well as when therapies are changed. However, the question remains about how frequently to monitor a patient endoscopically who has excellent disease control on stable therapy, and practice varies widely related to this.57 It is important, however, to have sufficient communication to allow newly diagnosed patients and caretakers to assimilate information and accurately implement the treatment plan, and to monitor treatment adherence. The monitoring approach in children may also be different given the need to assess growth and potential side effects of therapies. In the future, it is highly likely that less invasive monitoring methods will allow for decreased costs, as well as more routine monitoring that might pick up early disease flares that can be treated before complications arise.58Unsedated transnasal endoscopy (TNE) has been described in children with EoE, and in the initial report by Friedlander and colleagues, cost savings were substantial with >60% reduction compared with standard sedated endoscopy.59 Nguyen and colleagues have recently reported a large experience with TNE in children, and across almost 300 successful procedures, costs were decreased by 53% (~$4,400 for TNE compared to $9400 for EGD).60 Newer methods under development hold a promise of being far less expensive. The Esophageal String Test and Cytosponge can potentially be performed to sample the esophagus and monitor disease activity during a routine clinic visit rather than in an expensive procedural suite,61, 62 but costs of new diagnostic strategies have not been set and at present remain unknown, though are suggested to be lower in data presented in abstract form.63

A final principle, and perhaps the most important one, is that of patient-centric care. As EoE is still a “young” disease, evidence to support many clinical decisions is still needed, and a formal decision aid may be useful. As such, using a shared decision making model to select testing and treatment options seems prudent. If providers are cognizant of both the overt and hidden costs of EoE, as their patients most assuredly are, then providing cost-effective care can be incorporated into all clinical decisions. This also goes beyond cost-effectiveness to include symptom control and quality of life, and necessitates clear communication about treatments, testing, and goals. For example, if a patient is on an elimination diet but has not fully understood how to avoid the selected foods and there is ongoing disease activity, this is a “wasted” endoscopy that is not helpful in evaluating whether the treatment was successful. Additionally, as EoE is often managed with a multidisciplinary team that might not all be physically present on a given day that a patient is evaluated, communication amongst providers is imperative, and would be cost-effective. Communication is also crucial as children transition from pediatric to adult providers64, 65 because this is a time where patients could be lost to follow-up and develop complications which are costly to treat. New models of provider-patient interactions, via either patient portals or using telemedicine are promising, and should be studied in the context of EoE to determine if this reduces costs and/or improves outcomes. One simple cost saving measure may be telephone follow-up to convey results after endoscopy, depending on patient and provider preferences. This could save time required for patients to be off from work or school to come to the doctor’s office as well as costs associated with the office visit. This requires a potential sacrifice from providers as care provided over the phone may not be reimbursed or reflected in patient care effort, and may be more appropriate for follow-up and treatment changes in patients with known EoE rather than in patients who are newly diagnosed.

Conclusion

As a rare disease, EoE has outsized costs. High costs can be related to diagnostic delays, requirement for upper endoscopy with biopsy for diagnosis and monitoring of disease activity, expensive medications that are all currently used off-label, expensive dietary treatment options that are not often reimbursed by insurance, frequent doctor visits with subspecialists, and complications or disease exacerbations that result in additional expensive tests and treatments. High costs are also an understudied area in EoE, but there are many future areas of research that can be explored to optimize cost-effective care for EoE patients. If accurate predictors of treatment response can be identified, then treatment can be personalized and improved. This would increase the efficiency of care as the most effective treatments could be directed to those would most benefit from them, while patients unlikely to respond could be spared the costs of taking and evaluating a treatment that is not likely to work. This is particularly important if the biologic agents which are under study come into use,11 as they have the potential to increase costs substantially, and will required the development of guidelines and algorithms regarding when the use of these agents is warranted. If reliable minimally- or non-invasive methods to monitor disease activity are validated, either with tests that directly sample the esophagus or assess a peripheral biomarker, then costs associated with endoscopy can be greatly decreased. Coordinating a multidisciplinary care team may also save costs and facilitate communication amongst providers and between providers and patients. In addition, efforts by multiinstitutional consortia and patient advocacy groups to increase disease awareness among patients and education among providers will ultimately lead to more centers specializing in care,66 so patients can be effectively treated locally without having to travel large distances to find a provider. In the meantime, having a rational approach to cost-effective care using a patient-centric shared decision making model is currently the best option. Appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic algorithms, clear goals for starting with individual treatments and for when to perform endoscopy, using maintenance therapy for long-term disease control and complication minimization are tenets of cost-effective care in EoE at the current time.

Key Messages.

Though EoE is a rare disease, the costs of care related to EoE are substantial.

High costs in EoE can be related to diagnostic delays, requirement for upper endoscopy with biopsy for diagnosis and monitoring of disease activity, expensive medications currently used off-label, increased food costs related to dietary elimination treatment, frequent doctor visits with subspecialists, and complications or disease exacerbations.

Cost-effective care may be providing using a patient-centric approach and shared decision-making model, with a rationale strategy for EoE diagnosis and initial treatment, effective maintenance therapy for disease control and ideally to prevent complications, and appropriate long-term monitoring.

Provision of cost-effective care in EoE is an understudied area, and there a multiple areas where future research can make an impact.

Financial support:

This paper was supported by NIH R01 DK101856 and CEGIR (U54 AI117804) which is part of the Rare Disease Clinical Research Network (RDCRN), an initiative of the Office of Rare Diseases Research (ORDR), NCATS, and is funded through collaboration between NIAID, NIDDK, and NCATS. CEGIR is also supported by patient advocacy groups including APFED CURED and EFC.

Disclosures: Dr. Dellon has received research funding from Adare, Allakos, GSK, Meritage, Miraca, Nutricia, Celgene/Receptos, Regeneron, and Shire; has received consulting fees from Adare, Alivio, Allakos, AstraZeneca, Banner, Calypso, Celgene/Receptos, Enumeral, EsoCap, Gossamer Bio, GSK, Regeneron, Robarts, Shire, and educational grants from Allakos, Banner, and Holoclara.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dellon ES, Liacouras CA, Molina-Infante J, Furuta GT, Spergel JM, Zevit N, et al. Updated international consensus diagnostic criteria for eosinophilic esophagitis: Proceedings of the AGREE conference. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:1022–3.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dellon ES, Hirano I. Epidemiology and Natural History of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:319–22.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dellon ES, Jensen ET, Martin CF, Shaheen NJ, Kappelman MD. Prevalence of Eosinophilic Esophagitis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:589–96.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dellon ES, Erichsen R, Baron JA, Shaheen NJ, Vyberg M, Sorensen HT, et al. The increasing incidence and prevalence of eosinophilic oesophagitis outpaces changes in endoscopic and biopsy practice: national population-based estimates from Denmark. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:662–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schoepfer AM, Safroneeva E, Bussmann C, Kuchen T, Portmann S, Simon HU, et al. Delay in diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis increases risk for stricture formation in a time-dependent manner. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(6):1230–6 e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dellon ES, Kim HP, Sperry SL, Rybnicek DA, Woosley JT, Shaheen NJ. A phenotypic analysis shows that eosinophilic esophagitis is a progressive fibrostenotic disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:577–85.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warners MJ, Oude Nijhuis RAB, de Wijkerslooth LRH, Smout A, Bredenoord AJ. The natural course of eosinophilic esophagitis and long-term consequences of undiagnosed disease in a large cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(6):836–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dellon ES, Liacouras CA. Advances in Clinical Management of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(6):1238–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nhu QM, Aceves SS. Medical and dietary management of eosinophilic esophagitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;121(2):156–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirano I, Collins MH, Assouline-Dayan Y, Evans L, Gupta S, Schoepfer AM, et al. RPC4046, a Monoclonal Antibody Against IL13, Reduces Histologic and Endoscopic Activity in Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:592–603.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wechsler JB, Hirano I. Biological therapies for eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;142(1):24–31 e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Philpott H, Dellon ES. The role of maintenance therapy in eosinophilic esophagitis: who, why, and how? J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:165–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jensen ET, Kappelman MD, Martin CF, Dellon ES. Health-Care Utilization, Costs, and the Burden of Disease Related to Eosinophilic Esophagitis in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(5):626–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mukkada V, Falk GW, Eichinger CS, King D, Todorova L, Shaheen NJ. Health-Related Quality of Life and Costs Associated With Eosinophilic Esophagitis: A Systematic Review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(4):495–503 e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jose J, Virojanapa A, Lehman EB, Horwitz A, Fausnight T, Jhaveri P, et al. Parental perception of anxiety in children with eosinophilic esophagitis in a tertiary care center. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;119(4):382–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leiman DA, Kochar B, Posner S, Fan C, Patel A, Shaheen O, et al. A diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis is associated with increased life insurance premiums. Dis Esophagus. 2018;31(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hiremath G, Kodroff E, Strobel MJ, Scott M, Book W, Reidy C, et al. Individuals affected by eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders have complex unmet needs and frequently experience unique barriers to care. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2018;42:483–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peery AF, Crockett SD, Murphy CC, Lund JL, Dellon ES, Williams JL, et al. Burden and Cost of Gastrointestinal, Liver, and Pancreatic Diseases in the United States: Update 2018. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(1):254–72 e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwartz S, Manuel-Rubio M, Shaykin R, Hotwagner PG, Wechsler JB, Kagalwalla AF. Cost comparison of steroids vs. different elimination diet for the treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;63 (Suppl 2):S171–S2 (Ab 513). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stobaugh D, Deepak P, Ehrenpreis E. An analysis of hospital charges and length of stay in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis admitted for foreign body in the esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108 (Suppl 1):S12–3 (AB 33). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wadhwa V, Garg SK, Lopez R, Sanaka MR, Wadhwa N, Thota PN. Underdiagnosis of Eosinophilic Esophagitis (EoE) Related Esophageal Foreign Body Impactions in National Inpatient Sample. Gastroenterology. 2016;150 (Suppl 1):S669–S70 (Mo1202). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eke R, Vos D, Kamath S, Bauler LD, JLeonov A. The Epidemiology and Cost of Inpatient Care for Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112 (Suppl 1):S186.(Ab 343). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Solanki S, Haq KF, Khan MA, Khan VN, Patel S, Mansuri U, et al. Trends of eosinophilic esophagitis in the US inpatient population. Gastroenterology. 2017;152 (Suppl 1):S873.(Tu1131). [Google Scholar]

- 24.RedBook. [cited 2019 March 1]; Available from: www.micromedexcolutions.com.

- 25.Cotton CC, Erim D, Eluri S, Palmer SR, Green DJ, Wolf WA, et al. Cost-utility analysis of topical steroids compared to dietary elimination for treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:841–9.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolf WA, Huang KZ, Durban R, Iqbal ZJ, Robey BS, Khalid FJ, et al. The Six-Food Elimination Diet for Eosinophilic Esophagitis Increases Grocery Shopping Cost and Complexity. Dysphagia. 2016;31:765–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Groetch M, Venter C, Skypala I, Vlieg-Boerstra B, Grimshaw K, Durban R, et al. Dietary Therapy and Nutrition Management of Eosinophilic Esophagitis: A Work Group Report of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(2):312–24 e29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller SM, Goldstein JL, Gerson LB. Cost-effectiveness model of endoscopic biopsy for eosinophilic esophagitis in patients with refractory GERD. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(8):1439–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liacouras CA, Wenner WJ, Brown K, Ruchelli E. Primary eosinophilic esophagitis in children: successful treatment with oral corticosteroids. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1998;26(4):380–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prasad GA, Talley NJ, Romero Y, Arora AS, Kryzer LA, Smyrk TC, et al. Prevalence and Predictive Factors of Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Patients Presenting With Dysphagia: A Prospective Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2627–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dellon ES, Speck O, Woodward K, Gebhart JH, Madanick RD, Levinson S, et al. Clinical and Endoscopic Characteristics do Not Reliably Differentiate PPI-Responsive Esophageal Eosinophilia and Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Patients Undergoing Upper Endoscopy: A Prospective Cohort Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(12):1854–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kavitt RT, Penson DF, Vaezi MF. Eosinophilic esophagitis: dilate or medicate? A cost analysis model of the choice of initial therapy. Dis Esophagus. 2014(27):418–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schneider Y, Saumoy M, Otaki F, Schnoll-Sussman F, Bosworth B, Soumekh A, et al. A Cost-Eff ectiveness Analysis of Treatment Options for Adult Eosinophilic Esophagitis Utilizing a Markov Model. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111 (Suppl 1):S213–S4 (Ab 472). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reed CC, Koutlas NT, Robey BS, Hansen J, Dellon ES. Prolonged Time to Diagnosis of Eosinophilic Esophagitis Despite Increasing Knowledge of the Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(10):1667–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lucendo AJ, Molina-Infante J, Arias A, Von Arnim U, Bredenoord AJ, Bussmann C, et al. Guidelines on eosinophilic esophagitis: Evidence-based statements and recommendations for diagnosis and management in children and adults. United European Gastroenterol J. 2017;5:335–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spergel JM, Dellon ES, Liacouras CA, Hirano I, Molina-Infante J, Bredenoord AJ, et al. Summary of the updated international consensus diagnostic criteria for eosinophilic esophagitis: AGREE conference. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;121(3):281–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reed CC, Tappata M, Eluri S, Shaheen NJ, Dellon ES. Combination Therapy with Elimination Diet and Corticosteroids is Effective for Adults with Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reed CC, Safta AM, Qasem S, Angie Almond M, Dellon ES, Jensen ET. Combined and Alternating Topical Steroids and Food Elimination Diet for the Treatment of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63(9):2381–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lucendo AJ, Arias A, Molina-Infante J. Efficacy of Proton Pump Inhibitor Drugs for Inducing Clinical and Histologic Remission in Patients With Symptomatic Esophageal Eosinophilia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:13–22.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cotton CC, Eluri S, Wolf WA, Dellon ES. Six-Food Elimination Diet and Topical Steroids are Effective for Eosinophilic Esophagitis: A Meta-Regression. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:2408–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arias A, Gonzalez-Cervera J, Tenias JM, Lucendo AJ. Efficacy of Dietary Interventions for Inducing Histologic Remission in Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(7):1639–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Philpott H, Nandurkar S, Royce SG, Thien F, Gibson PR. Allergy tests do not predict food triggers in adult patients with eosinophilic oesophagitis. A comprehensive prospective study using five modalities. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44(3):223–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Safroneeva E, Straumann A, Coslovsky M, Zwahlen M, Kuehni CE, Panczak R, et al. Symptoms Have Modest Accuracy in Detecting Endoscopic and Histologic Remission in Adults With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(3):581–90 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aceves SS. Food Allergy Testing in Eosinophilic Esophagitis: What the Gastroenterologist Needs to Know. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:1216–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Robey BS, Eluri S, Reed CC, Jerath MR, Hernandez ML, Commins SP, et al. Subcutaneous immunotherapy in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Straumann A, Conus S, Degen L, Frei C, Bussmann C, Beglinger C, et al. Long-term budesonide maintenance treatment is partially effective for patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(5):400–9 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Greuter T, Bussmann C, Safroneeva E, Schoepfer AM, Biedermann L, Vavricka SR, et al. Long-Term Treatment of Eosinophilic Esophagitis With Swallowed Topical Corticosteroids: Development and Evaluation of a Therapeutic Concept. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:1527–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Greuter T, Safroneeva E, Bussmann C, Biedermann L, Vavricka SR, Katzka DA, et al. Maintenance treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis with swallowed topical steroids alters disease course over a 5-year follow-up period in adult patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:419–28.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eluri S, Runge TM, Hansen J, Kochar B, Reed CC, Robey BS, et al. Diminishing Effectiveness of Long-Term Maintenance Topical Steroid Therapy in PPI Non-Responsive Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2017;8(6):e97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Andreae DA, Hanna MG, Magid MS, Malerba S, Andreae MH, Bagiella E, et al. Swallowed Fluticasone Propionate Is an Effective Long-Term Maintenance Therapy for Children With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(8):1187–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rajan J, Newbury RO, Anilkumar A, Dohil R, Broide DH, Aceves SS. Long-term assessment of esophageal remodeling in patients with pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis treated with topical corticosteroids. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:147–56.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Runge TM, Eluri S, Woosley JT, Shaheen NJ, Dellon ES. Control of inflammation decreases the need for subsequent esophageal dilation in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Dis Esoph. 2017;30:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Philpott H, Dougherty MK, Reed CC, Caldwell M, Kirk D, Torpy D, et al. Systematic review: Adrenal insufficiency secondary to swallowed topical corticosteroids in eosinophilic oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47:1071–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Freedberg DE, Kim LS, Yang YX. The Risks and Benefits of Long-term Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors: Expert Review and Best Practice Advice From the American Gastroenterological Association. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(4):706–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reed CC, Fan C, Koutlas NT, Shaheen NJ, Dellon ES. Food Elimination Diets are Effective for Long-term Treatment of Adults with Eosinophilic Oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46:836–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang R, Hirano I, Doerfler B, Zalewski A, Gonsalves N, Taft T. Assessing Adherence and Barriers to Long-Term Elimination Diet Therapy in Adults with Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63(7):1756–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dellon ES, Gupta SK. A conceptual approach to understanding treatment response in eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hiremath G, Gupta SK. Promising Modalities to Identify and Monitor Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(11):1655–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Friedlander JA, DeBoer EM, Soden JS, Furuta GT, Menard-Katcher CD, Atkins D, et al. Unsedated transnasal esophagoscopy for monitoring therapy in pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:2999–306.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nguyen N, Lavery WJ, Capocelli KE, Smith C, DeBoer EM, Deterding R, et al. Transnasal Endoscopy in Unsedated Children With Eosinophilic Esophagitis Using Virtual Reality Video Goggles. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Furuta GT, Kagalwalla AF, Lee JJ, Alumkal P, Maybruck BT, Fillon S, et al. The oesophageal string test: a novel, minimally invasive method measures mucosal inflammation in eosinophilic oesophagitis. Gut. 2013;62(10):1395–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Katzka DA, Smyrk TC, Alexander JA, Geno DM, Beitia RA, Chang AO, et al. Accuracy and Safety of the Cytosponge for Assessing Histologic Activity in Eosinophilic Esophagitis: A Two-Center Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:1538–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Alexander JA, Katzka DA, Ravi K, Fitzgerald RC, Geno DM, Tholen C, et al. Efficacy of Cytosponge Directed Food Elimination Diet in Eosinophilic Esophagitis: A Pilot Trial. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(Suppl 1):S-76.(Ab 30). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dellon ES, Jones PD, Martin NB, Kelly M, Kim SC, Freeman KL, et al. Health care transition from pediatric to adult-focused gastroenterology in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Dis Esophagus. 2013;26(7–13). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Eluri S, Book WM, Kodroff E, Strobel MJ, Gebhart JH, Jones PD, et al. Lack of Knowledge and Low Readiness for Healthcare Transition in Eosinophilic Esophagitis and Eosinophilic Gastroenteritis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;65:53–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gupta SK, Falk GW, Aceves SS, Chehade M, Collins MH, Dellon ES, et al. Consortium for Eosinophilic Researchers: Advancing the Field of Eosinophilic GI Disorders Through Collaboration. Gastroenterology. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]