Abstract

While natural photosynthesis serves as the model system for efficient charge separation and decoupling of redox reactions, bio‐inspired artificial systems typically lack applicability owing to synthetic challenges and structural complexity. We present herein a simple and inexpensive system that, under solar irradiation, forms highly reductive radicals in the presence of an electron donor, with lifetimes exceeding the diurnal cycle. This radical species is formed within a cyanamide‐functionalized polymeric network of heptazine units and can give off its trapped electrons in the dark to yield H2, triggered by a co‐catalyst, thus enabling the temporal decoupling of the light and dark reactions of photocatalytic hydrogen production through the radical′s longevity. The system introduced here thus demonstrates a new approach for storing sunlight as long‐lived radicals, and provides the structural basis for designing photocatalysts with long‐lived photo‐induced states.

Keywords: artificial photosynthesis, carbon nitrides, EPR spectroscopy, hydrogen evolution, stable radical

Photosynthesis is the exemplary biological process for capturing and storing the abundant but intermittent energy from the sun. Photosystems I and II efficiently separate the light‐induced electron–hole pairs through a series of donor and acceptor co‐factors—the electron‐transport chain—to compartmentalize the two halves of the overall redox reaction, thus minimizing both electron–hole recombination and back reaction. Coupled to the light‐dependent photosystems is the Calvin–Benson cycle, a light‐independent (“dark”) process that uses the chemical energy and low‐potential electrons (as ATP and NADPH generated during irradiation) to produce carbohydrates as a building block and storable energy vector. The molecular machinery of photosynthesis thus serves as a model for developing artificial systems for solar‐fuel generation, which can replace the non‐renewable combustion of fossil fuels with a pollution‐free energy cycle.1 However, no artificial photosynthetic system currently exists that is commercially viable for the capture and storage of solar energy in chemical fuels.

We present herein an artificial photocatalytic system that has two parallels to natural photosynthesis, namely long‐lived “trapped” electrons as reducing equivalents, and the ability to decouple the light‐dependent and light‐independent reactions to enable “dark” photocatalysis. Unlike natural photosynthesis and bio‐inspired systems where highly specific, multiple pigment‐based electron relays are necessary to prevent recombination,2 our system combines the dual functions of the photosystem and electron relay in a single carbon nitride species, which is robust and easy to make from earth‐abundant precursors. This system has the ability not only to store electrons when irradiated or charged electrochemically (similar to TiO2),3 but also to release them on demand when coupled to an electrocatalyst, with time‐delays in the order of hours. As such, complex photoelectrochemical configurations become redundant.4 This feature provides an alternative approach to the intermittency of solar irradiation, which is in high demand given the currently limited availability of high capacity and safe electrical and chemical storage mechanisms.

The photocatalyst is a cyanamide‐functionalized heptazine‐based polymer (denoted henceforth as NCN‐CNx)5 obtained by an ionothermal treatment of melon6 (also known as graphitic carbon nitride) with KSCN. The local structure and opto‐electronic properties of these materials are summarized in Table S1 in the Supporting Information. This polymer changes color from yellow to blue when irradiated in the presence of certain electron donors in an oxygen‐free environment, whereas no change is observed in the presence of TEMPO ((2,2,6,6‐tetramethyl‐piperidin‐1‐yl)oxyl) as an electron scavenger,7 suggesting the formation of long‐lived “trapped” electrons (Figure S3). Carbon nitrides, previously referred to as “quasi monomers” in terms of their photophysics,8 are generally believed to suffer from fast de‐excitation through charge recombination, which inherently limits their photocatalytic activity.9 Herein, we demonstrate that the light‐induced transient species in NCN‐CNx has a lifetime from tens of minutes to hours after cessation of irradiation. The observed trapping of photoelectrons may therefore bypass the need for efficient charge carrier separation in carbon nitrides.

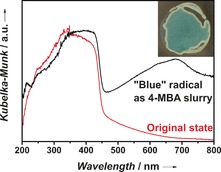

While the pristine “yellow” NCN‐CNx shows one main absorption band with onset at 450 nm, the “blue” NCN‐CNx exhibits a broad absorption in the range 500–750 nm in its diffuse reflectance spectrum (Figure 1) similar to the distinctive three‐band pattern observed for the blue radical from 1,4‐dicyanamidobenzene dianion,10 though these features are better resolved as a propylene carbonate suspension (Figure S4).

Figure 1.

Diffuse reflectance UV/Vis spectra of the “blue” NCN‐CNx slurried with aqueous 4‐methylbenzyl alcohol (4‐MBA), and of its original “yellow” state. Inset: a photograph of the blue slurry in the spectrometer sample holder.

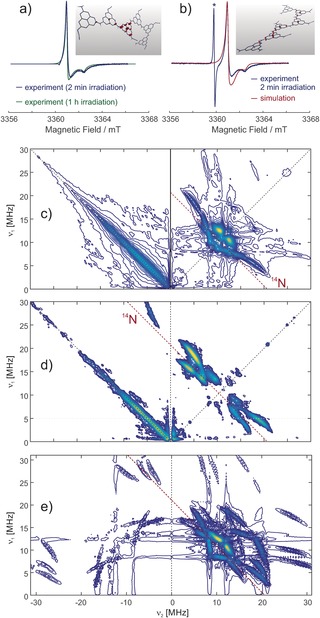

EPR spectroscopy was employed to determine the nature of the trapped electron species (detailed analyses in the Supporting Information). The light‐generated “blue” NCN‐CNx shows a strong, uncharacteristic and nearly symmetric Gaussian line near the free electron g value at X‐band frequency of approximately 9.6 GHz (data not shown). The intensity of the EPR signal begins to plateau after 1 h of irradiation (Figure S5a), then decays over 16 h after removing the light source (Figure S5b), thus demonstrating the longevity of this radical species. At a higher field of about 3.361 T, anisotropy of the g tensor is resolved in a continuous‐wave (CW) EPR spectrum, although the principal values are distributed by significant anisotropic strain (Figure 2 a,b), indicating the presence of several types of radicals that differ slightly in their electronic structure. The spectral line shape depends on irradiation time, with strain being reduced at longer irradiation times. The spectrum can be simulated with mean g tensor principal values that are typical for a π radical. The radicals exhibit unusually fast relaxation and a broad distribution of relaxation times that is consistent with the existence of radicals with different delocalization of the electron spin or different exchange and dipole–dipole coupling to neighboring radicals.

Figure 2.

W‐band EPR spectroscopy of light‐irradiated NCN‐CNx taken at a frequency of 94.2 GHz and DFT computations on model oligomer radical anions. a) Dependence of the CW EPR spectrum on the duration of irradiation. In the spectrum obtained with 2 min irradiation, a line from a MnII internal reference was removed. The inset shows the spin density distribution in a hexamer with a charge‐neutral cyanamide side group isolated between anionic cyanamide side groups. b) Simulation taking into account a rhombic g tensor (gx, gy, gz)=(2.00246, 2.00285, 2.00295) with strain (0.00060, 0.00037, 0.00006) and an axial 14 N hyperfine tensor (0.9, 0.9, 18.0) MHz with strain (0, 0, 18.0) MHz. The asterisk denotes a line from a MnII:MgO internal reference. Inset: the spin density distribution in a hexamer with only charge‐neutral cyanamide side groups. c)–e) HYSCORE spectra of NCN‐CNx at W‐band frequencies. The spectra are sums of three magnitude spectra measured or simulated with interpulse delays τ of 124, 144, and 164 ns. Intensity on the antidiagonal in the left quadrant of the experimental spectra is due to incomplete suppression of an echo crossing by phase cycling. c) Spectrum taken at the maximum of the EPR absorption spectrum (3362.8 mT). The red line denotes the 14N nuclear Zeeman frequency of 10.35 MHz along the diagonal direction. d) Spectrum taken at a field of 3364 mT. e) Simulated spectrum. All simulations were performed with EasySpin.12

Further insight can be obtained from hyperfine sublevel correlation (HYSCORE) spectra at W‐band frequencies, where strong 14 N nuclear modulation is observed. The spectra (Figure 2 c–e) display rich features from a single axial 14N hyperfine coupling tensor. Note that cross suppression hides correlation peaks of other nuclei if one nucleus is close to exact cancellation,11 an effect that in our case prevents observation of 14N nuclei with weaker hyperfine coupling.

By a set of DFT computations we have explored a structural space consisting of oligomers of triazine and heptazine repeat units without and with charge‐neutral and ionic cyanamide side groups (see Supporting Information). According to these computations, the observed hyperfine coupling corresponds to about 0.7 % spin density in the s orbital and about 10 % spin density in a p orbital on the 14N nucleus, which in turn indicates spin localization to one heptazine repeat unit with only slight delocalization to the neighboring units. In oligomer models with more than two repeat units, such localization is observed for a heptazine unit with a charge‐neutral cyanamide side group if the immediate and next neighbors are anionic cyanamide side groups. For such oligomer models, the nuclear quadrupole coupling and g tensor principal values also agree with experiment within the combined experimental and computational uncertainties. For alternative triazine‐based oligomer models with more than two triazine units or for heptazine‐based oligomers without cyanamide side groups, the experimental parameters do not match.

Note that the experimental data is consistent with the existence of additional radicals of similar type that are more delocalized. According to the DFT computations, such radicals have similar g values and smaller hyperfine couplings. This matches the large hyperfine strain that is required in the simulation of the CW EPR spectrum. The smaller hyperfine couplings lead to much smaller nuclear modulation depths and thus are not observed in the HYSCORE spectrum. Such stronger delocalization is found in the DFT computations if neighboring heptazine units all have neutral cyanamide side groups or if two heptazine units with neutral cyanamide side groups are separated by only one unit with an anionic side group. Considering the experimental evidence from W‐band CW EPR and HYSCORE and the computational evidence from the DFT calculations, the radicals can be assigned to a polymer of heptazine units with cyanamide side groups that are partially in a charge‐neutral and partially in an anionic state (charge‐compensated by K+ ions). Note that the EPR data are consistent with both a 1D melon structure (insets in Figure 2 a,b) and a 2D poly(heptazine imide)‐type (PHI) backbone carrying cyanamide defects.13

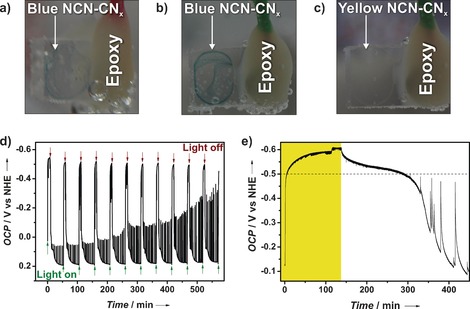

The “blue radical” is highly reductive with a potential more negative than −445 mV versus the normal hydrogen electrode (NHE) as determined using the pH‐independent redox indicator methyl viologen (MV; Figure S8).14 This is also verified by photoelectrochemical measurements using working electrodes of fluorine‐doped tin oxide (FTO) on which NCN‐CNx was drop‐cast (Figure 3). Under concentrated simulated sunlight (7 sun) in an electrolyte solution containing 4‐MBA, the open circuit potential (OCP) increased to about −500 mV versus NHE, and then decayed back to its original, yellow state after the irradiation source was switched off; these OCP results can be reproduced for over 10 cycles of light on and off without significant changes (Figure 3 d). The decay of the blue radicals back to the non‐reduced state is noticeably faster as a film on FTO compared to the powder suspension. This is attributed to an accelerated charge transfer from the thin film of the NCN‐CNx radical to the FTO substrate; small amounts of oxygen leakage may also be possible. As shown in Figure 3 e, increasing the irradiation time led to further increase of the OCP that slowly saturates, coming along with an increase in the time required for the blue state to decay back to the yellow state. This behavior suggests a continuum of closely spaced accessible states in NCN‐CNx and resembles capacitive charging. This blue state can also be induced solely electrochemically in the dark by applying a potential more negative than −500 mV versus NHE as described in Table S3. Similar to above, the considerably shorter lifetime of the electrochemically populated states on the order of minutes compared to the suspension is likely due to fast back transfer of charges from NCN‐CNx to the FTO.

Figure 3.

Photographs of NCN‐CNx drop‐cast on FTO: a) blue state after illumination in the presence of 4‐MBA; b) blue state after charging by applying −530 mV versus NHE in the dark, and c) the original state after de‐charging by applying 0 V versus NHE. Photoelectrochemical measurements of electrodes of NCN‐CNx on FTO: d) OCP monitored under continuous chopped light, showing reproducible excitation of the blue state at about −500 mV versus NHE. The spikes during the decay after illumination arise from current peaks of NCN‐CNx particles that are in weak electrical contact with FTO and are decharged with a time delay when the potential difference is sufficiently large. e) Effect of longer illumination time in the presence of sodium citrate as electron donor (period of illumination highlighted in yellow). The population of even higher electronic states occurs slowly but continuously as shown in the region above the dashed line.

Since the above measurements suggest that the “blue” state is long lived and thermodynamically capable of reducing H+ to H2 (the hydrogen evolution reaction, HER), it can be exploited for time‐delayed “dark” photocatalysis for generating hydrogen in a fashion similar to the light‐independent reactions in natural photosynthesis or the redox decoupled electrochemical water‐splitting systems reported recently.4

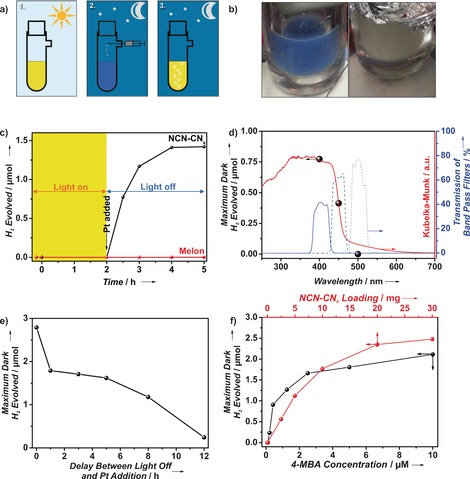

This process, as illustrated in Figure 4 a,c, first involves generating the radical by irradiating an aqueous suspension of NCN‐CNx containing an electron donor, such as 4‐MBA—see the Supporting Information for details regarding the standard experimental methods. Henceforth, we focus solely on 4‐MBA as a donor, as the photophysics and interaction between NCN‐CNx and this molecule is well understood,5b and the use of 4‐MBA leads to a high yield of the blue radical. After irradiation, the reaction is isolated from light and hydrogen is evolved on demand upon addition of a suitable HER catalyst, such as a Pt colloid (marked by a black arrow in Figure 4 c). The amount of hydrogen evolved maximizes typically two hours after cessation of irradiation and is accompanied by reversion of the material's color back to yellow (Figure 4 b, right).

Figure 4.

a) Schematic summary of the dark hydrogen evolution process: 1. Irradiation of the NCN‐CNx suspension to form the blue radical state; 2. Addition of a solution of hydrogen evolution co‐catalyst under oxygen‐free transfer in the dark, and 3. Evolution of hydrogen with the concomitant reversal of suspension color. b) Photographs of the “blue radical” (left) and its color reversal subsequent to dark hydrogen evolution (right). c) Plot illustrating the process of dark hydrogen evolution as a function of time, in which the region highlighted in yellow corresponds to the period of irradiation. d) Wavelength dependence on maximum dark hydrogen evolved (black spheres) overlaid on the diffuse reflectance UV/Vis spectrum of the NCN‐CNx (red line) and the transmission spectra of the filters used (blue lines; 400 nm solid, 450 nm dashed, 500 nm dotted). e) Maximum dark hydrogen evolved as a function of the time between switching off the light and injection of the Pt colloid. f) Maximum dark hydrogen evolved versus NCN‐CNx loading and 4‐MBA concentration.

As a control, this “dark” photocatalysis does not occur for melon, illustrating the necessity of the cyanamide moiety for radical formation (Figure 4 c, red plot). Likewise, the blue radical is not observed when NCN‐CNx is irradiated with electron acceptors such as MV, Pt or O2 (Figure S9), corroborating that a reduced state is responsible for the coloration and that “dark” photo‐oxidation does not occur. We demonstrate that this long‐lived radical, and in turn hydrogen evolution in the dark, is manifested by band gap excitation by employing irradiation at different wavelengths. As shown in Figure 4 d, the amount of dark hydrogen evolved follows the UV/Vis diffuse reflectance spectrum of NCN‐CNx, with dark hydrogen evolving when the irradiation source was filtered with a 400 nm or 450 nm, but not 500 nm, band pass filter.

Furthermore, as with the growth in EPR signal following irradiation (Figure S5 a), the amount of dark hydrogen evolved increases towards a plateau with increasing irradiation intensity and time (Figure S10 b–d), suggesting that the radical population is correlated with photons impinging on the sample. In addition to the slow decay of the EPR signal after cessation of irradiation (Figure S5 b), the longevity of the radical can also be demonstrated by varying the delay between switching off the light and injection of platinum to commence the dark hydrogen evolution. Figure 4 e illustrates the decoupling of irradiation and hydrogen production and shows that the dark hydrogen evolution can be initiated as much as 12 h after irradiation ceased, thus demonstrating the lifetime of these radicals to exceed the nocturnal duration.

The total dark hydrogen evolved has a negligible dependence on the amount of platinum injected (ca. 10 % increase of maximum dark H2 evolved with 4 times the amount of platinum injected, see Figure S9 b), but is dependent on the NCN‐CNx loading and the amount of donor (Figure 4 f). The total dark hydrogen evolved can provide an indirect measure of radical density if one assumes one molecule of H2 is obtained from two radicals. For 10 mg of NCN‐CNx, which would correspond to 40 μmol of the cyanamide‐heptazine units assuming a molecular weight of 249 g mol−1, 1.77 μmol of hydrogen was evolved and is equivalent to 3.54 μmol of radical. We provide a rough estimate of one in ten cyanamide‐heptazine motifs to be involved in the radical formation, although we stress that it is based on the assumptions that: 1) no other decay pathways exist, and 2) 100 % of the radicals transfer into hydrogen. This dark photocatalytic hydrogen evolution process can be repeated for over 15 cycles (Figure S11 e,f), although with decreasing amount of dark hydrogen evolved. Reasons for this decrease are deactivation of the Pt colloid and partial hydrolysis of NCN‐CNx to urea with concomitant loss of K+ based on characterization of the spent material (Figure S12).

In summary, we demonstrate a carbon nitride‐based material that can harvest and store sunlight as long‐lived trapped electrons for redox chemistry in the dark, akin to the light‐dependent and independent processes in natural photosynthesis. As revealed by EPR spectroscopy, the system comprises a partially anionic, cyanamide‐functionalized heptazine polymer, which in the presence of an appropriate electron donor forms a radical species under irradiation that has a lifetime of over ten hours. This ultra‐long‐lived radical can reductively produce hydrogen in the presence of a hydrogen evolution catalyst in the dark on demand. The storage of trapped electrons within a carbon nitride backbone may open the prospect for overcoming limitations of the diurnal availability of sunlight for solar fuel production, provided that a scalable photo‐oxidation process can be identified. This finding not only reveals a hitherto undescribed property of heptazine‐based materials exploitable for specialized applications,15 but may also inspire rational design of photocatalytic materials16 with long‐lived, photo‐induced states, a challenge that currently limits their applicability. Finally, the long‐lived radical can also be prepared electrochemically by applying a cathodic voltage. The continuous charging of the carbon nitride with electrons reveals a capacitor‐like function, which suggests that energy storage by this carbon nitride photocatalyst in the form of a “solar battery” may ultimately become possible.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (project LO1801/1‐1) and an ERC Starting Grant (B.V.L., grant number 639233), the Max Planck Society, the cluster of excellence Nanosystems Initiative Munich (NIM), and the Center for Nanoscience (CeNS). We acknowledge support by the Christian Doppler Research Association (Austrian Federal Ministry of Science, Research and Economy, National Foundation for Research, Technology and Development) and the OMV Group (H.K., E.R.). V.W.‐h.L. gratefully acknowledges a postdoctoral scholarship from the Max Planck Society. We would also like to thank Ms Michaela Wieland for the XPS analysis, Dr. Igor Moudrakovski for the solid‐state NMR measurements, Dr. Reinhard Kremer for the preliminary EPR characterizations, and Mr Benjamin Martindale for fruitful discussions.

V. W.-h. Lau, D. Klose, H. Kasap, F. Podjaski, M.-C. Pignié, E. Reisner, G. Jeschke, B. V. Lotsch, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 510.

Contributor Information

Dr. Erwin Reisner, Email: reisner@ch.cam.ac.uk.

Prof. Gunnar Jeschke, Email: gunnar.jeschke@phys.chem.ethz.ch.

Prof. Bettina V. Lotsch, Email: b.lotsch@fkf.mpg.de.

References

- 1.

- 1a. Wasielewski M. R., J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 5051–5066; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1b. Magnuson A., Anderlund M., Johansson O., Lindblad P., Lomoth R., Polivka T., Ott S., Stensjo K., Styring S., Sundstrom V., Hammarstrom L., Acc. Chem. Res. 2009, 42, 1899–1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.

- 2a. J. D. Megiatto, Jr. , Antoniuk-Pablant A., Sherman B. D., Kodis G., Gervaldo M., Moore T. A., Moore A. L., Gust D., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 15578–15583; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2b. Gust D., Moore T. A., Moore A. L., Acc. Chem. Res. 2009, 42, 1890–1898; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2c. Li X., Wang M., Zhang S., Pan J., Na Y., Liu J., Akermark B., Sun L., J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 112, 8198–8202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mohamed H. H., Mendive C. B., Dillert R., Bahnemann D. W., J. Phys. Chem. A 2011, 115, 2139–2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.

- 4a. Rausch B., Symes M. D., Chisholm G., Cronin L., Science 2014, 345, 1326–1330; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4b. Rausch B., Symes M. D., Cronin L., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 13656–13659; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4c. Symes M. D., Cronin L., Nat. Chem. 2013, 5, 403–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.

- 5a. Lau V. W.-h., Moudrakovski I., Botari T., Weinberger S., Mesch M. B., Duppel V., Senker J., Blum V., Lotsch B. V., Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12165; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5b. Kasap H., Caputo C. A., Martindale B. C. M., Godin R., Lau V. W.-H., Lotsch B. V., Durrant J. R., Reisner E., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 9183–9192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.

- 6a. Wang X., Maeda K., Thomas A., Takanabe K., Xin G., Carlsson J. M., Domen K., Antonietti M., Nat. Mater. 2009, 8, 76–80; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6b. Lotsch B. V., Döblinger M., Sehnert J., Seyfarth L., Senker J., Oeckler O., Schnick W., Chem. Eur. J. 2007, 13, 4969–4980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Li L., Zhang Z., Wang D., Wan Q., J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 1997, 102, 279–284. [Google Scholar]

- 8.

- 8a. Merschjann C., Tyborski T., Orthmann S., Yang F., Schwarzburg K., Lublow M., Lux-Steiner M.-C., Schedel-Niedrig T., Phys. Rev. B 2013, 87, 205204; [Google Scholar]

- 8b. Merschjann C., Tschierlei S., Tyborski T., Kailasam K., Orthmann S., Hollmann D., Schedel-Niedrig T., Thomas A., Lochbrunner S., Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 7993–7999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Huda M. N., Turner J. A., J. Appl. Phys. 2010, 107, 123703. [Google Scholar]

- 10.

- 10a. Rezvani A. R., Evans C. E. B., Crutchley R. J., Inorg. Chem. 1995, 34, 4600–4604; [Google Scholar]

- 10b. Crutchley R., Comp. Coord. Chem. II 2004, 2, 785–796. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stoll S., Calle C., Mitrikas G., Schweiger A., J. Magn. Reson. 2005, 177, 93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stoll S., Schweiger A., J. Magn. Reson. 2006, 178, 42–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Döblinger M., Lotsch B. V., Wack J., Thun J., Senker J., Schnick W., Chem. Commun. 2009, 1541–1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mitoraj D., Kisch H., J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 20890–20895. [Google Scholar]

- 15.

- 15a. Schwarzer A., Saplinova T., Kroke E., Coord. Chem. Rev. 2013, 257, 2032–2062; [Google Scholar]

- 15b. Liu J., Wang H., Antonietti M., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 2308–2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vyas V. V., Lau V. W.-H., Lotsch B. V., Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 5191–5204. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary