Abstract

Objective

This study evaluates English newspaper coverage of mental health topics between 2008 and 2014 to provide context for the concomitant improvement in public attitudes and seek evidence for changes in coverage.

Method

Articles in 27 newspapers were retrieved using keyword searches on two randomly chosen days each month in 2008–2014, excluding 2012 due to restricted resources. Content analysis used a structured coding framework. Univariate logistic regression models were used to estimate the odds of each hypothesised element occurring each year compared to 2008.

Results

There was a substantial increase in the number of articles covering mental health between 2008 and 2014. We found an increase in the proportion of antistigmatising articles which approached significance at P < 0.05 (OR = 1.21, P = 0.056). The decrease in stigmatising articles was not statistically significant (OR = 0.90, P = 0.312). There was a significant decrease in the proportion of articles featuring the stigmatising elements ‘danger to others’ and ‘personal responsibility’, and an increase in ‘hopeless victim’. There was a significant proportionate increase in articles featuring the antistigmatising elements ‘injustice’ and ‘stigma’, but a decrease in ‘sympathetic portrayal of people with mental illness’.

Conclusion

We found a decrease in articles promoting ideas about dangerousness or mental illness being self‐inflicted, but an increase in articles portraying people as incapable. Yet, these findings were not consistent over time.

Keywords: mental health, mental disorders, social marketing, social stigma, newspapers

Significant outcomes.

A small but significant positive change in newspaper reporting of mental health topics was identified through the observed increase in antistigmatising articles and a simultaneous decrease in the presentation of mental illness as ‘dangerous to others’.

Specific mental health diagnoses are persistently reported in a stigmatising manner.

Limitations.

The study's findings are not generalisable to developmental disorders and neurodegenerative diseases as articles reporting on the specific conditions were excluded from the sample.

The focus of the study was placed on the text aspect of the eligible articles. Other powerful contextual aspects of the articles such as photographs were not included in the analysis.

Introduction

Stigma and discrimination against people with mental illness have substantial public health impact in England, maintaining inequalities 1 including poor access to mental and physical health care 2, reduced life expectancy 3, 4, exclusion from higher education 5, 6, employment 7, increased risk of contact with criminal justice systems, victimisation 8, poverty and homelessness. Stigma associated with mental illness is recognised as having a negative impact on the lives of people with mental illness, causing decreased perception of self‐worth and social withdrawal, and leading to social isolation, poor employment, education, housing options and delayed access to services 9. Rusch et al. hypothesise that these factors also independently contribute to increased suicidality amongst people with mental health problems 10.

Thornicroft defined stigma as problems of knowledge (ignorance and misinformation), attitudes (prejudice) and behaviour 9 while a recent study by Schomerus et al. suggests that negative attitudes towards mental illness increase over the life span 11, and the media are a main source of knowledge about mental illness for many people. Media coverage can both shape and reflect attitudes to mental illness, although the most documented causal link is between negative reporting and prejudicial attitudes 10, 12, 13, 14. In the context of the Time to Change programme specifically, there are two reasons to study media coverage over the course of the programme. First, the overall effect of the mass media on attitudes may either enhance or reduce the effectiveness of campaigns to reduce mental health‐related stigma; an assessment of changes in coverage over time is therefore useful in interpreting the outcomes of antistigma programmes in terms of public attitudes. Second, examination of coverage for allows an assessment of the effectiveness of this programme's targeted work with journalists and editors.

Media coverage of mental illness worldwide has frequently been shown to be inaccurate and stigmatising, associating people with mental health problems with violence and criminality, or portraying them as hopeless victims 15, 16. Within articles related to homicides, suicides and other violent crimes, Carpiniello et al. found that articles reporting crimes committed by mentally ill people are significantly longer and contain more pictures and stigmatising language 17.

Coverage of topics such as recovery from mental health problems has been as little as 4% of mental health articles 18, and few articles contain quotes from people with mental health problems themselves. Treatments for mental health are frequently portrayed as ineffective or punitive, and articles discussing psychopharmacological treatments are also more critical than articles discussing cardiac medications 19.

The evidence for longitudinal change in reporting is limited: Clement and Foster found no evidence of significant change in UK reporting on schizophrenia between 1996 and 2005 20, although Wahl found small but positive changes in US reporting between 1989 and 1999 21. Whitley et al. demonstrated in a longitudinal study of Canadian print media that there had been no significant change in mental health reporting over a 5‐year period 22. In the UK, a content analysis published in 2013 documented that over a 10‐year period, mental health articles had increased in number but continued to use pejorative terms and link mental illness with violence and drug use 23, while Goulden et al. found a significant proportional reduction in negative articles about mental illness between 1992 and 2008, and a proportional increase in articles explaining mental illness. Goulden also found that coverage had improved for depression but remained largely negative for schizophrenia over this period 24.

Coverage of mental illness can positively or negatively influence the attitudes of the general public; Klin and Lemish hypothesise that positive framing of mental disorders may contribute to developing positive perceptions and reducing stigma 25. Corrigan et al. demonstrated that scores on measures of stigma and affirming attitudes are significantly affected by newspaper articles about mental health 26: participants reading an article about recovery from mental health problems showed decreased stigmatising beliefs and increased affirming attitudes. Participants reading an article discussing failures in provision of mental health services resulting in a suicide demonstrated the reverse.

In England, from 2009, Time to Change conducted a targeted social media campaign, and a large number of grassroots community projects with the aim of reducing mental health stigma and discrimination. Evans‐Lacko et al. found favourable changes in attitudes and confidence to challenge stigma following bursts of the Time to Change social marketing campaign 27.

Thornicroft et al. previously found a significant increase in the proportion of antistigmatising articles on mental illness during Phase 1 of the Time to Change campaign, 2008–2011, no reduction in the proportion of stigmatising articles, and fewer articles coded as mixed or neutral 28.

Aims of the study

This study provides an update to previously reported findings and an overview of the changes in newspaper reporting of mental illness over the duration of the Time to Change campaign. We addressed the same hypotheses as used to study coverage during the first phase of Time to Change 29:

We tested the hypotheses that there would be

a significant increase in the overall proportion of antistigmatising articles;

-

a significant increase in the proportion of articles featuring the following antistigmatising elements:

mental health promotion,

stigma or

injustice;

a significant decrease in the overall proportion of stigmatising articles;

-

a significant decrease in the proportion of articles featuring the following stigmatising elements:

danger to others or

pejorative language;

-

a significant increase in the proportion of sources who are

people with a mental illness,

family/friends/carers or

mental health charities.

Material and methods

The Lexis Nexis Professional UK electronic newspaper database was used to search articles from 27 local and national newspapers which were published on two randomly chosen days each month, and which referred to mental illness.

Ten national mass circulation (>100 000), daily newspapers and the eight highest circulation regional newspapers in England were used. To ensure geographical diversity, only one newspaper per town/city was used. The Sun on Sunday is used from 2011 onwards to replace ‘News of the World’ which went out of print in July 2011.

The following newspapers were included: Daily/Sunday Telegraph, Daily/Sunday Mail, Daily/Sunday Star, Daily/Sunday Express, Daily/Sunday Mirror, Times/Sunday Times, Sun/Sun on Sunday, Guardian/Observer, Independent/Independent on Sunday, Birmingham Evening mail, Eastern Daily Press (Norwich), Evening Chronicle (Newcastle), The Evening Standard, Hull Daily Mail, Leicester Mercury, Liverpool Echo, Manchester Evening News, The Sentinel (Stoke).

Inclusion criteria

Articles were included if they focused on mental illness, that is upon people with mental illness or mental health services. The search terms consisted of 35 general and diagnostic terms covering the full range of mental disorders. This approach follows Wahl's recommendations 19. The full text of articles in the selected newspapers were searched using the following terms (* = wildcard): ‘mental health OR mental illness OR mentally ill OR mental disorder OR mental patient OR mental problem OR (depression NOT W/1 economic OR great) OR depressed OR depressive OR schizo! OR psychosis OR psychotic OR eating disorder OR anorexi! OR bulimi! OR personality disorder OR dissociative disorder OR anxiety disorder OR anxiety attack OR panic disorder OR panic attack OR obsessive compulsive disorder OR OCD OR post‐traumatic stress OR PTSD OR social phobia OR agoraphobi! OR bipolar OR ADHD OR attention deficit OR psychiatr! OR mental hospital OR mental asylum OR mental home OR secure hospital’.

Exclusion criteria

Non‐literal and non‐clinical references to mental health were excluded, as well as articles which mentioned mental illness only peripherally. Articles which used a search term (i) in a context unrelated to mental health (e.g. ‘the government is schizophrenic about this issue’); (ii) described a non‐clinical use (e.g. ‘I'm feeling a bit depressed about this’); or (iii) where diagnostic or slang terms were used metaphorically (e.g. ‘he's driving me nuts’) were excluded. Articles relating primarily to developmental disorders (e.g. autism), neurodegenerative diseases (e.g. Alzheimer's) or alcohol/substance abuse were excluded.

Coding

Articles were coded for their date; newspaper origin; and article type (news, features or opinion); diagnoses mentioned, and any person/source directly or indirectly quoted. The central theme or idea conveyed in each article was coded into an ‘element’, which was stigmatising, antistigmatising or neutral. These elements were derived from (i) existing studies of mental health reporting; (ii) the wider literature on mental health stigma; and (iii) a process of inductive coding, in which a sample of articles was qualitatively analysed for recurrent themes and ideas. Finally, each article was coded overall as stigmatising, antistigmatising, mixed or neutral.

To maximise consistency of coding over time, a detailed codebook was developed, outlining the criteria to be used in coding. Coding was completed by RG in 2008–2009, GS in 2010, AT in 2011, DRh in 2013 and A‐MK in 2014. Each researcher completed trials of coding which was compared with coding performed by RG and discussed with him, to identify and address areas of potential discrepancy. Kappa analysis was performed between pairs of coders: a minimum of 0.73 was achieved, indicating substantial agreement.

Analysis

Frequencies and proportions of elements in the articles were determined. Univariate logistic regression models were used to estimate the odds that each of the hypothesised elements would occur in each year compared to the 2008 baseline data.

Each element was counted only once per article, that is whether or not present in each article. Frequencies and proportions of sources were calculated.

A Wald test was used to assess the overall statistical significance of the year variable as the predictor in each model, and a Holm–Bonferroni adjustment was used on the P‐values of the Wald tests to reduce the probability of making a type 1 error (concluding there is a difference when there is none), after multiple testing. A Wald test was used to test for specific differences between 2008 and 2014 data sets.

Results

The press cuttings sample

The sampling protocol outlined above retrieved a total of 1350 articles for 2014. This compares with 1738 articles for 2013, 1186 in 2011, 1701 in 2010, 1935 in 2009 and 1882 in 2008. After exclusions, including duplicates and those not meeting the inclusion criteria, a total of 941 articles were left for the final analysis. In 2013, 934 were used, in 2011, 698 were used, 627 articles were used in 2010, in 2009, 794 articles were included, and in 2008, 882 articles were included.

Changes in elements reported

In 2014, a greater percentage of articles were stigmatising (44%) than antistigmatising (35%), with the remainder mixed (7%) or neutral (14%), see Table 1. There was an increase in antistigmatising articles in 2014 compared with 2008 which approached significance at P < 0.05 (OR = 1.21, 95% CI 1.00–1.47, P = 0.056), but the small decrease in stigmatising articles during the same period was not statistically significant (OR = 0.90, 95% CI 0.76–1.09, P = 0.312). However, analysis of the proportion of articles coded as stigmatising or antistigmatising each year compared to 2008 demonstrated that these changes were not consistent across the 6 years studied, see Table 2.

Table 1.

Elements coded by year

| Yeara | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 [n (%)] | 2009 [n (%)] | 2010 [n (%)] | 2011 [n (%)] | 2013 [n (%)] | 2014 [n (%)] | ||

| Antistigmatising elements | |||||||

| Mental health promotion | 59 (7) | 41 (5) | 26 (4) | 125 (18) | 80 (5) | 108 (8) | 439 (13.1) |

| Stigma | 11 (1) | 16 (2) | 7 (1) | 16 (2) | 56 (4) | 34 (3) | 140 (4.2) |

| Injustice | 42 (5) | 55 (7) | 25 (4) | 30 (4) | 125 (8) | 88 (7) | 365 (10.9) |

| Stigmatising elements | |||||||

| Danger to others | 186 (21) | 138 (17) | 130 (21) | 95 (14) | 74 (5) | 109 (8) | 732 (21.8) |

| Pejorative language | 49 (6) | 61 (8) | 26 (4) | 31 (4) | 106 (7) | 50 (4) | 323 (9.6) |

| Overall coding | |||||||

| Stigmatising | 406 (46) | 342 (43) | 316 (50) | 316 (45) | 359 (38) | 411 (44) | 2150 (44) |

| Antistigmatising | 273 (31) | 284 (36) | 212 (34) | 288 (41) | 373 (40) | 331 (35) | 1761 (36) |

| Mixed | 58 (7) | 48 (6) | 30 (5) | 37 (5) | 58 (6) | 67 (7) | 298 (6) |

| Neutral | 145 (16) | 120 (15) | 69 (11) | 57 (8) | 143 (15) | 132 (14) | 666 (14) |

Percentages calculated from the total number of articles containing the element over the total number of articles for each year.

Table 2.

Logistic regression of the proportion of stigmatising and antistigmatising articles per year compared to 2008

| OR | SE | P | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | ||||

| Stigmatising | |||||

| 2008 | Reference | ||||

| 2009 | 0.89 | 0.09 | 0.224 | 0.73 | 1.08 |

| 2010 | 1.19 | 0.12 | 0.094 | 0.97 | 1.46 |

| 2011 | 0.97 | 0.10 | 0.763 | 0.79 | 1.18 |

| 2013 | 0.73 | 0.07 | 0.001 | 0.61 | 0.88 |

| 2014 | 0.90 | 0.08 | 0.312 | 0.76 | 1.09 |

| Antistigmatising | |||||

| 2008 | Reference | ||||

| 2009 | 1.24 | 0.13 | 0.037 | 1.01 | 1.52 |

| 2010 | 1.14 | 0.13 | 0.241 | 0.92 | 1.42 |

| 2011 | 1.57 | 0.17 | <0.001 | 1.27 | 1.93 |

| 2013 | 1.49 | 0.15 | <0.001 | 1.22 | 1.80 |

| 2014 | 1.21 | 0.12 | 0.056 | 1.00 | 1.47 |

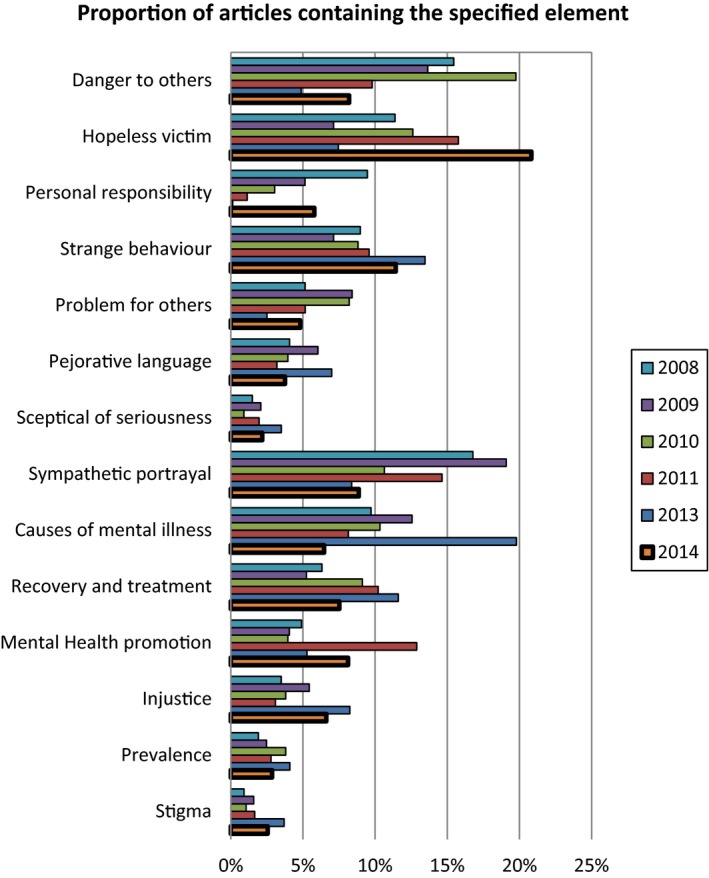

Figure 1 (below) illustrates that much of the increase in the antistigmatising articles can be explained by the increase in the ‘mental health promotion’, ‘injustice’ and ‘stigma’ elements in 2014 when compared to 2008. In the stigmatising category, although the elements ‘danger to others’ (OR = 0.49, P < 0.001) and ‘personal responsibility’ (OR = 0.59, P < 0.001) decreased significantly, the ‘hopeless victim’ was the most frequently reported element in 2014, accounting for more than one‐fifth of the overall coded elements.

Figure 1.

Proportion of articles containing the specified element across the 7 years of study.

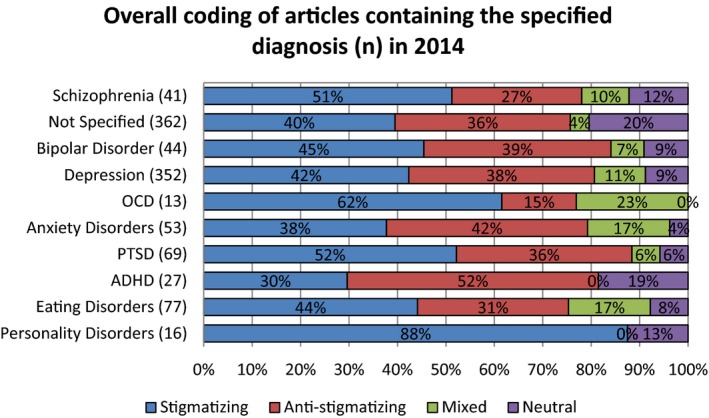

Diagnosis

The proportions of articles featuring the specific diagnoses coded were broadly similar over 7 years, with articles about depression and those which do not discuss a specific diagnosis accounting for almost two‐thirds of the total. Patterns of the overall tone of the articles coded in 2014 are illustrated in Fig. 2 according to the principal diagnosis.

Figure 2.

Overall tone of articles per diagnosis in 2014.

Sources of comments and quotations

The distribution of source types was overall similar throughout the years studied with some notable exceptions. Across the 7 years, there was a significant increase (9–21%) in ‘other individual’ as a source (OR = 2.67, P < 0.001). There was a decrease in mental health service providers (17–12%) (OR = 0.65, P = 0.001) and in the ‘not specified’ category (41–34%) (OR = 0.39, P < 0.001) as a source. No significant changes were found in the proportion of articles that cited mental health charities (OR = 0.94, P = 0.854), people with mental illness (OR = 0.95, P = 0.653) or their family/friends/carers (OR = 0.83, P = 0.187) as their sources between the 2008 and 2014 articles .

Table 3.

Frequency and proportion of sources by year

| Sources | Year | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 [n (%)] | 2009 [n (%)] | 2010 [n (%)] | 2011 [n (%)] | 2013 [n (%)] | 2014 [n (%)] | |

| People with a mental illness | 149 (18) | 116 (16) | 100 (23) | 115 (28) | 194 (23) | 217 (18) |

| Family/friends/carers | 134 (16) | 116 (16) | 68 (16) | 48 (12) | 114 (13) | 151 (13) |

| Mental health service providers | 123 (17) | 104 (17) | 68 (16) | 51 (13) | 117 (14) | 143 (12) |

| Other individual | 65 (9) | 47 (8) | 43 (10) | 50 (13) | 165 (19) | 253 (21) |

| Mental health charities | 17 (2) | 23 (3) | 14 (3) | 23 (6) | 31 (4) | 27 (2) |

Discussion

Over the 7‐year period evaluated, the numbers of articles covering mental health stories in England have significantly increased. Our findings suggest that there has been a slight increase in the proportion of articles which present mental illness in an antistigmatising manner and a simultaneous proportional decrease in the depiction of mental illness as ‘dangerous to others’ in newspaper coverage.

In detail, we found a substantial increase in the number of articles meeting our inclusion criteria between 2008 and 2014. This supports previous research findings that mental health coverage in the UK is increasing disproportionately to increases in other news stories 23. The rising profile of mental health issues in the media could be interpreted as the result of or contributor to greater public awareness of mental health or both.

Regarding the first and second of our hypotheses, we found a marginal increase in the proportion of antistigmatising articles between 2008 and 2014 as a result of increases in the main aspects of antistigmatising coverage (stigma, injustice and mental health promotion). A decrease in the proportion of stigmatising articles was also found although it was not statistically significant. There was therefore little support for our third hypothesis. However, these changes were not demonstrated consistently between the 7 years studied: some years found no evidence of significant change compared to previous years. This variability may be explained by the chance occurrences of incidents that are widely reported, for example violent crimes committed by people with mental health problems, or interviews with celebrities regarding their mental health. We found support for one component of hypothesis four, namely the reduction in the proportion of articles featuring the element ‘danger to others’. The proportional shift in stigmatising elements from ‘danger to others’ and ‘personal responsibility’ to that of ‘hopeless victim’ is similar to changes observed by Knifton and Quinn in Scottish newspaper coverage of schizophrenia over the course of the Scottish antistigma campaign See Me 29. These authors observed a fall in the proportion of articles they categorised as including the theme of dangerousness, but also a fall in the proportion of positive depictions. There was no support for our fifth hypothesis with respect to mental health charities, people with mental health problems or members of their support networks.

In 2014 print media, anxiety disorders and ADHD were the diagnoses that were more often reported in an antistigmatising manner. These were frequently found in articles that suggested that ‘recovery/successful treatment’ is possible, in ‘sympathetic portrayals’ of individuals with mental health issues and in articles that aimed in the promotion of knowledge around mental illness. Personality disorders, schizophrenia, OCD, PTSD and eating disorders were mostly represented in a stigmatising context. The former three were often coded alongside elements which reported ‘strange behaviour’ of the people with mental health problems, while eating disorders and PTSD were mostly found in articles which placed an emphasis on the ‘hopelessness’ of the individuals with these diagnoses.

The changes we report are consistent with recent evidence of improving public attitudes to mental illness 30. These attitudes are likely to be influenced by and/or influence newspaper coverage. During the time period studied, Time to Change has likely affected reporting through the effects of two of its components: the inclusion of newspaper journalists and editors as a target group for advice, training and lobbying, and the effect of its social marketing campaign on journalists as members of the public. However, our mixed results show that this impact has been a partial one, and the lack of a consistent pattern over time precludes optimism about continued positive change in the future.

It will be important to continue to assess newspaper coverage of mental health topics in the future, particularly beyond the end of Time to Change. Further research including a qualitative analysis would be invaluable in exploring the progression of reporting of mental health problems in greater depth.

Mental health activists may consider using the results of this current research in future education targeting journalists. In particular, we concur with Knifton and Quinn's conclusion that antistigma campaigns should address negative depictions other than that of violence 29. Thus, Time to Change's campaign aimed at picture editors to use alternative images to those of people with their heads in their hands (http://www.time-to-change.org.uk/news/campaign-aimed-picture-editors-puts-mental-health-frame-0) could be extended to address the textual equivalent. A recent Cochrane collaboration review of mass media interventions found that first person narratives and social inclusion or human rights messages were most effective in reducing prejudice 31. Future interventions could focus on training and empowering people with experience of mental health problems to engage with journalists to provide opinions and quotes, and to describe their experiences. This would be particularly relevant for individuals with mental health problems which are more often portrayed in a stigmatising manner. The same review found that portrayal of acute symptoms and biomedical messages can increase prejudice, so further training aimed at journalists should encourage a more holistic portrayal of the individual.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The strengths and limitations of this study are discussed below with reference to Whitley et al.'s five domains of difficulty in analysing media representations of mental illness 32: (i) defining relevant search terms: It is possible that the search terms used did not identify all articles that could convey references to mental health, although pilot searches for non‐diagnostic terms such as ‘stress’ and ‘breakdown’, as well as a long list of slang terms, revealed that they yielded no additional, relevant stories. (ii) developing appropriate inclusion and exclusion criteria: We have excluded articles relating to neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative conditions; conditions such as dementia and autism have been prominent in the media over the last 7 years, and this study may have therefore missed changes in articles related to these conditions. (iii) creating a coding scheme: The coding framework for this study was designed with reference to three sources: existing studies of mental health reporting, the wider literature on mental health stigma and a process of inductive coding, in which a sample of articles was qualitatively analysed for recurrent themes and ideas. (iv) choosing strategies of analysis and dissemination: This study was designed as a quantitative analysis, to facilitate statistical analysis of changing reporting over time. We focused on content analysis of the text in the articles and did not code other powerful contextual aspects related to the article, such as photographs and headlines used, and placing of the article. (v) staffing and training issues: The newspaper articles were coded by different research workers, although all researchers used the same detailed codebook, and differences in coding were minimised using trial periods of coding, assessment of agreement levels and discussing discrepancies with other coders.

Funding

Time to Change programme, grants from UK Department of Health and Comic Relief.

Declarations of interest

GT has received grants for stigma‐related research in the past 5 years from the National Institute for Health Research.

Acknowledgements

We thank Sue Baker, Maggie Gibbons and Paul Farmer, Mind; Paul Corry and Mark Davies, Rethink Mental Illness, for their collaboration. DR and GT are also supported in relation to the NIHR Specialist Mental Health Biomedical Research Centre at the Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London and the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (GT). GT and DR are supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care South London at King's College London Foundation Trust. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

The study was partly funded by the UK Department of Health, Big Lottery Fund and Comic Relief through their funding of the Time to Change programme.

Rhydderch D, Krooupa A‐M, Shefer G, Goulden R, Williams P, Thornicroft A, Rose D, Thornicroft G, Henderson C. Changes in newspaper coverage of mental illness from 2008 to 2014 in England.

References

- 1. Hatzenbuehler M, Phelan J, Link B. Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. Am J Public Health 2013;103:813–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mai Q, D'Arcy C, Holman J, Sanfilippo F, Emery J, Preen D. Mental illness related disparities in diabetes prevalence, quality of care and outcomes: a population‐based longitudinal study. BMC Med 2011;9:118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Laursen T, Munk‐Olsen T, Nordentoft M, Mortensen PB. Increased mortality among patients admitted with major psychiatric disorders: a register‐based study comparing mortality in unipolar depressive disorder, bipolar affective disorder, schizoaffective disorder, and schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 2007;68:899–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gissler M, Laursen TM, Ösby U, Nordentoft M, Wahlbeck K. Patterns in mortality among people with severe mental disorders across birth cohorts: a register‐based study of Denmark and Finland in 1982–2006. BMC Public Health 2013;13:834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Suhrcke M, De Paz Nieves C. The impact of health and health behaviours on educational outcomes in high‐income countries: a review of the evidence. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee S, Tsang A, Breslau J et al. Mental disorders and termination of education in high‐income and low‐ to middle‐income countries: epidemiological study. Br J Psychiatry 2009;194:411–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Social Exclusion Unit . Mental health and social exclusion. London: Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Clement S, Brohan E, Sayce L, Pool J, Thornicroft G. Disability hate crime and targeted violence and hostility: a mental health and discrimination perspective. J Ment Health 2011;20:219–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Thornicroft G. Shunned: discrimination against people with mental illness. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rusch N, Zlati A, Black G, Thornicroft G. Does the stigma of mental illness contribute to suicidality? Br J Psychiatry 2014;205:257–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schomerus G, van der Auwera S, Matschinger H, Baumeister SE, Angermeyer MC. Do attitudes towards persons with mental illness worsen during the course of life? An age‐period‐cohort analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2015;132:357–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Philo G. The media and public belief In: Philo G, ed. Media and mental distress. Harrow: Longman, 1996:82–114. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dietrich S, Heider D, Matschinger H, Angermeyer M. Influence of newspaper reporting on adolescents’ attitudes toward people with mental illness. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2006;41:318–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Thornton J, Wahl O. Impact of a newspaper article on attitudes toward mental illness. J Community Psychol 1996;24:17–25. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wahl O. Mass‐media images of mental illness: a review of the literature. J Community Psychol 1992;20:343–352. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Coverdale R, Nairn R, Claasen D. Depictions of mental illness in print media: a prospective national sample. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2002; 36:697–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Carpiniello B. Mass‐media, violence and mental illness: evidence from some Italian newspapers. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc 2007;16:251–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rusch N, Angermeyer M, Corrigan P. Mental illness stigma: concepts, consequences, and initiatives to reduce stigma. Eur Psychiatry 2005;20:529–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sartorius N, Gaebel W, Cleveland H et al. WPA Guidance on how to combat stigmatization of psychiatry and psychiatrists. World Psychiatry 2010;9:131–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Clement S, Foster N. Newspaper reporting on schizophrenia: a content analysis of five national newspapers at two time points. Schizophr Res 2008;98:178–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wahl OE, Wood A, Richards R. Newspaper coverage of mental illness: is it changing? Am J Psychiatr Rehabil 2002;6:9–31. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Whitley R, Berry S. Trends in newspaper coverage of mental illness in Canada 2005‐2010. Can J Psychiatry 2013;58:107–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Murphy N, Fatoya F, Wibberley C. The changing face of newspaper representations of the mentally ill. J Ment Health 2013;22:271–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Goulden R, Corker E, Evans‐Lacko S, Rose D, Thornicroft G, Henderson C. Newspaper coverage of mental illness in the UK, 1992‐2008. BMC Public Health 2011;11:796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Klin A, Lemish D. Mental disorders stigma in the media: review of studies on production, content and influences. J Health Commun 2008;13:434–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Corrigan P, Powell K, Michaels P. The effects of news stories on the stigma of mental illness. J Nerv Ment Dis 2013;201:179–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Evans‐Lacko S, Malcolm E, West K et al. Influence of time to change's social marketing interventions on stigma in England 2009‐2011. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 2013;55:77–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Thornicroft A, Goulden R, Shefer G et al. Newspaper coverage of mental illness in England 2008‐2011. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 2013;202:64–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Knifton L, Quinn N. Media, mental health and discrimination: a frame of reference for understanding reporting trends. Int J Ment Health Promot 2008;10:1023–1031. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Evans‐Lacko S, Corker E, Williams P, Henderson C, Thornicroft G. Trends in public stigma among the English population in 2003‐2013: influence of the Time to Change anti‐stigma campaign. Lancet Psychiatry 2014;1:121–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Clement S, Lassman F, Barley E et al. Mass‐media interventions for reducing mental health‐related stigma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 27:7:DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD009453.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Whitley R, Berry S. Analyzing media representations of mental illness: lessons learnt from a national project. J Ment Health 2013;22:246–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]