Abstract

Photolabile protecting groups (or “photocages”) enable precise spatiotemporal control of chemical functionality and facilitate advanced biological experiments. Extant photocages exhibit a simple input–output relationship, however, where application of light elicits a photochemical reaction irrespective of the environment. Herein, we refine and extend the concept of photolabile groups, synthesizing the first Ca2+‐sensitive photocage. This system functions as a chemical coincidence detector, releasing small molecules only in the presence of both light and elevated [Ca2+]. Caging a fluorophore with this ion‐sensitive moiety yields an “ion integrator” that permanently marks cells undergoing high Ca2+ flux during an illumination‐defined time period. Our general design concept demonstrates a new class of light‐sensitive material for cellular imaging, sensing, and targeted molecular delivery.

Keywords: bioimaging, calcium, fluorescence, ion sensing, photocaging

Small molecules that absorb light have broad utility as tools to probe and perturb biological systems. Chemical fluorophores constitute one important type of light‐absorbing molecule.1 The ability to modify dyes using chemistry allows the construction of numerous probes for specific applications. For example, changing the chemical structure of fluorophores can allow fine‐tuning of spectral properties. Likewise, chemical dyes that respond to changes in ion concentration have been prepared. The design and synthesis of such ion indicators involves incorporation of molecular recognition motifs into a fluorophore where the reversible binding of a specific ion alters the absorption and/or fluorescence quantum yield of the dye. This strategy has produced probes for many biologically relevant ions, including Na+, K+, Mg2+, Ca2+, and Zn2+, allowing noninvasive monitoring of ion concentration inside living cells.2

Photolabile protecting groups or “photocages” comprise another important class of organic chromophore where photon absorption elicits cleavage of a chemical bond.3 Like fluorophores, the spectral properties of photocages have been manipulated using chemistry, resulting in photolabile groups with longer wavelengths and larger two‐photon cross‐sections.4 However, unlike fluorescent dyes, the incorporation of ion‐sensitive motifs into photocages is essentially unexplored. Probes built from ion‐sensitive photolabile groups could complement reversible ion indicators, functioning as chemical coincidence detectors that would selectively and irreversibly release a small molecule only in the presence of both light and increased ion concentration. In particular, caging a fluorophore with such an ion‐sensitive photocage would yield a fluorescent ion “snapshot indicator” or “integrator” that would permanently record increased ion concentration during an illumination‐defined time period. Integrator systems based on fluorescent proteins5 and rhodopsins6 have been described recently, but small‐molecule ion integrators remain unknown. This currently limits the use of such probes to biological systems that are amenable to genetic manipulation. Herein we describe the design and synthesis of the first Ca2+‐sensitive photocage. Caging a coumarin fluorophore with this moiety yields a probe that exhibits a 600‐fold increase in photochemical quantum yield upon binding Ca2+. This compound can serve as an ion integrator that permanently marks neurons undergoing increased [Ca2+] elicited by ionophore treatment or electrical stimulation.

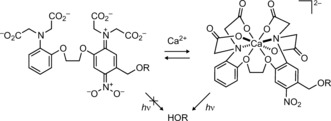

Nearly all small‐molecule Ca2+ indicators utilize the calcium‐ion chelator moiety 1,2‐bis(o‐aminophenoxy)ethane‐N,N,N′,N′‐tetraacetic acid (BAPTA) developed by Tsien.7 To fashion a Ca2+‐sensitive photocage we envisioned incorporating an o‐nitrobenzyl photolabile group into BAPTA as shown in Scheme 1. In the absence of Ca2+, we surmised that the para‐nitroaniline ring would adopt a charge‐separated colored quinoid form, which exhibits a low‐lying triplet state,8 thus suppressing photochemical release. Both nitrobenzyl and nitroindoline cages containing p‐dialkylamino substituents display low photochemical quantum yields (Φ).9 We expected Ca2+ binding would reverse this effect as the aniline nitrogen lone pair participates in chelation. This would recapitulate the o‐nitrobenzyl electronic structure and increase the Φ value.

Scheme 1.

Design of a Ca2+‐dependent photocage.

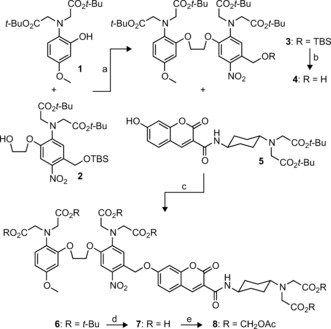

As a result of the intricacy of this molecular system, we developed a facile, modular synthesis of the Ca2+‐sensitive photocage and first‐generation integrator as shown in Scheme 2. We prepared phenol 1 and alcohol 2 through efficient 4‐ and 7‐step syntheses, respectively (see Scheme S1 in the Supporting Information). The key step in our convergent route is a high‐yielding Mitsunobu reaction between these atypical coupling partners to give bis‐phenoxyethane 3. The electron‐donating methoxy substituent on module 1 was incorporated to balance the requisite electron‐withdrawing nitro group on component 2 and maintain a biologically relevant equilibrium dissociation constant (K d) for Ca2+.7b Compound 3 was selectively deprotected to give benzyl alcohol 4. Attachment of coumarin 5 10 yielded 6, which could be deprotected to afford Ca2+‐dependent photocaged coumarin 7.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of Ca2+‐dependent photocaged coumarin 7 and permeable derivative 8. a) DIAD, PPh3, THF, 80 %. b) TBAF, THF, 95 %. c) DIAD, PPh3, THF, 71 %. d) TFA, CH2Cl2, 84 %. e) BrCH2OAc, DIEA, DMF, 51 %. DIAD=diisopropyl azodicarboxylate; TBAF=tetrabutylammonium fluoride; TFA=trifluoroacetic acid; DIEA=N,N‐diisopropylethylamine; TBS=tert‐butyldimethylsilyl.

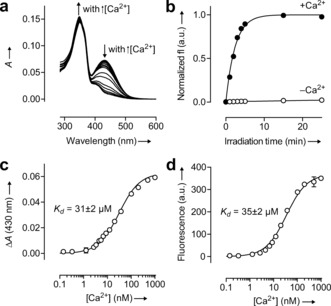

We first examined the absorption spectrum of 7 in buffers containing varying Ca2+ ion concentrations (Figure 1 a). The absorption in the visible region at λ=430 nm shows a dramatic decrease as [Ca2+] increases. We also observe a small (less than 5 %) but significant increase in absorption around 350 nm when the calcium ion concentration is raised. However, the coumarin moiety dominates absorption in the UV region with an extinction coefficient ɛ=2.4×104 m −1 cm−1 at λ=350 nm. These absorbance changes support our hypothesis that chelation of calcium would cause a switch from the colored quinoid form to the UV‐absorbing aromatic form (Scheme 1). We then investigated the Ca2+ dependence of the photochemical reaction of compound 7 in vitro where we observed efficient photochemistry only in the presence of calcium ions (Figure 1 b). Under illumination with light of wavelength λ=365 nm, the photocaged fluorophore 7 exhibited Φ values of 0.008 % and 4.8 % in the absence or presence of Ca2+, respectively. This 600‐fold enhancement in quantum yield further validates our molecular design. We determined the calcium ion affinity of compound 7 by measuring, as a function of [Ca2+], the change in absorption at λ=430 nm (Figure 1 c) or the initial fluorescence increase from photoactivation (Figure 1 d). We found K d values of 31 and 35 μm for the absorbance and fluorescence measurements, respectively, consistent with the nitro and methoxy substituents on the BAPTA system.7b To ensure generality of this approach we prepared an analogous compound based on the dye Tokyo Green (Scheme S2) and observed Φ −Ca=0.011 % and Φ +Ca=1.6 % (150‐fold enhancement) with similar affinity (K d=28 μm; Figure S1). Photocaged coumarins are known to exhibit higher photochemical quantum yields than other photoactivatable fluorophores as a result of efficient energy transfer from the coumarin chromophore to the photolabile cage moiety.10, 11

Figure 1.

Properties of the calcium‐sensitive photocage. a) Absorbance spectra of 7 in aqueous buffers containing different [Ca2+]. b) Normalized fluorescence intensity (fl) of released coumarin versus irradiation time (irradiating at λ=365 nm) of 7 in the presence (•; 10 mm CaCl2) or absence (○; 10 mm ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA)) of Ca2+ ions. c) Determination of the K d value of compound 7 by the change in absorption at λ=430 nm (ΔA). d) Determination of the K d value of compound 7 by the initial fluorescence increase. Error bars in (b–d) show ± the standard error (S.E.; n=2).

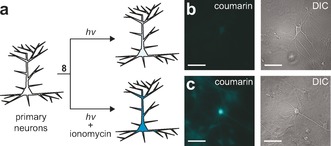

We next examined the utility of this system in a cellular context. The hexa‐acetoxymethyl (AM) ester of compound 7 was prepared (8; Scheme 2). This cell‐permeant compound enabled loading of cultured hippocampal neurons with the calcium‐sensitive photocaged dye. Cells were washed and then treated with normal media or media containing ionomycin, followed by illumination with activating light (Figure 2 a). The overlap of the photo‐uncaging wavelength (λ max=351 nm) with the absorption band of the released coumarin (λ max=402 nm) allowed simultaneous imaging and activation with a single light source centered at λ=365 nm. Illumination of control cells elicited a relatively small fluorescence increase (Figure 2 b). In contrast, cells pretreated with ionomycin showed a 40‐fold increase in the accumulation of cellular fluorescence (Figure 2 c; Figure S2). Similar results were observed in human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells (Figure S3).

Figure 2.

Function of Ca2+‐sensitive photocaged coumarin in neurons. a) Representation showing the experimental setup. b, c) Fluorescence (left) and differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy images (right) of live cultured hippocampal neurons incubated with AM ester 8 (10 μm) for 1 h and then illuminated with light of wavelength λ=365 nm for 20 s. Scale bars=100 μm. b) Untreated neurons. c) Neurons treated with ionomycin.

We then investigated if this approach could measure calcium ion changes in neurons induced by electrical stimulation. Low‐affinity reversible Ca2+ indicators are advantageous for studying biological systems as their low buffering capacity preserves native calcium ion dynamics.12 Nevertheless, the inherently poor signal‐to‐background ratios of such indicators typically restrict their utility to subcellular compartments undergoing extremely high calcium flux (for example, dendritic spines).13 We hypothesized that the permanent signal afforded by the ion integrator would allow measurement of smaller changes in cellular calcium levels using this non‐perturbative, low‐affinity probe.

To further support this prediction, we modeled the expected release rate of compound 7 under different Ca2+ concentrations using Equation (1):

| (1) |

where k=the rate of photochemical reaction, I=the intensity of light, σ=the decadic extinction coefficient, C=the concentration of indicator, Φ=the photochemical quantum yield, and subscripts b and f indicate Ca2+‐bound and Ca2+‐free, respectively. From mass action (see the Supporting Information), the concentration of bound indicator (Cb) can be calculated using Equation (2):

| (2) |

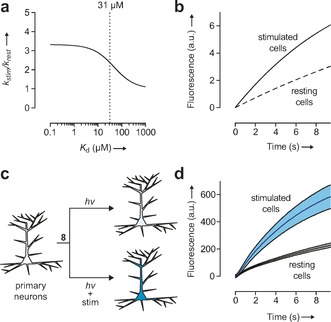

where Ct=total concentration of indicator, [Ca2+]t is the total calcium ion concentration in the cells, and K d is the dissociation constant of the Ca2+‐sensitive photocage indicator. The concentration of free indicator (Cf) can be calculated from Ct and Cb values. We first modeled the rate of uncaging in stimulated cells relative to the rate in resting cells (k stim/k rest, the uncaging contrast) as a function of K d value, assuming average Ca2+ ion concentrations of 245 nm and 62 nm in stimulated and resting cells, respectively,14 and an indicator concentration (Ct) of 10 μm (Figure 3 a). Under these conditions, the maximum achievable contrast is predicted to be 330 %. This value is largely dictated by the approximately fourfold increase in Ca2+ concentration and noncooperative binding of BAPTA (Hill coefficient=1). Moreover, our mathematical modeling predicts that decreasing the K d value has only a modest effect on contrast; compound 7 (K d=31 μm) should still give a k stim/k rest value of 240 % (Figure 3 a) resulting in a clear delineation of stimulated and unstimulated cells (Figure 3 b). This magnitude of photochemical contrast is similar to the change in fluorescence over resting fluorescence (ΔF/F 0) achieved with reversible small‐molecule Ca2+ indicators in cells (typically less than 300 %). However, we note the integrating‐type measurement of the Ca2+‐sensitive photocage yields a permanent rather than transient fluorescent signal.

Figure 3.

Theoretical and experimental performance of the Ca2+‐sensitive photocage as an ion integrator. a) Plot showing the theoretical uncaging contrast (k stim/k rest) as a function of K d. Dashed line shows the K d value for compound 7 (31 μm). b) Theoretical rate of fluorescence intensity increase using probe 7 in cells, assuming an average [Ca2+] of 245 nm and 62 nm in stimulated and resting cells, respectively. c) Schematic representation showing the experimental setup. d) Plot of the increase in cellular fluorescence intensity versus irradiation time of cultured neurons without electrical stimulation (gray; k=0.0325 s−1) and with stimulation (cyan; k=0.133 s−1). Shading shows ±S.E. (n=20).

We then tested this prediction in living cells with the experimental design shown in Figure 3 c. Cells were incubated with AM ester 8 and subjected to the photoactivation‐imaging procedure as before. In one population of cells we elicited neuronal action potential firing by field stimulation at 80 Hz. This electrical stimulation caused a significant rate increase in signal relative to unstimulated cells, giving a permanent, 200 % larger ΔF in stimulated cells (Figure 3 d). These experimental rates are similar to those predicted (Figure 3 b), validating the mathematical model.

In summary, we have designed and synthesized the first Ca2+‐sensitive photocage and demonstrated a new paradigm for sensing using small‐molecule ion integrators. Our probe exhibits high photochemical contrast, functions in a cellular context, and can sense biologically relevant calcium ion levels. This new class of small‐molecule Ca2+ indicator yields a permanent fluorescent signal that could enable simpler assays for high‐throughput screening or the post hoc mapping of active cells in genetically intractable organisms. Additionally, our modular synthetic strategy should facilitate improvements to this probe, such as modulating the Ca2+ affinity,2d, 15 altering the properties of the released fluorophore,16 increasing the two‐photon cross‐section of the photocage by using the indoline scaffold,9a, 17 and changing selectivity to other ions that are similarly unable to elicit chemical reactions on their own (e.g., Na+).2c, 18 Finally, unlike the genetically encoded systems,5, 6 the flexibility of this small‐molecule scaffold opens the door for pharmacological agents or chemical gene inducers to be photocaged and released using a “functional photochemistry” approach, allowing sophisticated biological experiments where active cells are selectively targeted for chemical manipulation.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

We thank H. White for cell culture assistance, D. Kim for use of the electrostimulation microscopy setup, and R. Kerr, S. Sternson, L. Looger, K. Svoboda, M. Tadross, and T. Gruber for contributive discussions (all at Janelia). The Howard Hughes Medical Institute supported this work.

L. M. Heckman, J. B. Grimm, E. R. Schreiter, C. Kim, M. A. Verdecia, B. C. Shields, L. D. Lavis, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 8363.

References

- 1.

- 1a. Lavis L. D., Raines R. T., ACS Chem. Biol. 2008, 3, 142–155; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1b. Lavis L. D., Raines R. T., ACS Chem. Biol. 2014, 9, 855–866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.

- 2a. Minta A., Tsien R. Y., J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 19449–19457; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2b. Minta A., Kao J. P., Tsien R. Y., J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 8171–8178; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2c. Martin V. V., Rothe A., Diwu Z., Gee K. R., Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2004, 14, 5313–5316; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2d. Adams S. R. in Imaging in neuroscience and development: A laboratory manual (Eds.: R. Yuste, A. Konnerth), Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, New York, 2005, pp. 239–244; [Google Scholar]

- 2e. Nolan E. M., Lippard S. J., Acc. Chem. Res. 2009, 42, 193–203; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2f. Kamiya M., Johnsson K., Anal. Chem. 2010, 82, 6472–6479; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2g. Fujii T., Shindo Y., Hotta K., Citterio D., Nishiyama S., Suzuki K., Oka K., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 2374–2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Puliti D., Warther D., Orange C., Specht A., Goeldner M., Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2011, 19, 1023–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.

- 4a. Kantevari S., Matsuzaki M., Kanemoto Y., Kasai H., Ellis-Davies G. C., Nat. Methods 2010, 7, 123–125; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4b. Fournier L., Gauron C., Xu L., Aujard I., Le Saux T., Gagey-Eilstein N., Maurin S., Dubruille S., Baudin J.-B., Bensimon D., ACS Chem. Biol. 2013, 8, 1528–1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fosque B. F., Sun Y., Dana H., Yang C.-T., Ohyama T., Tadross M. R., Patel R., Zlatic M., Kim D. S., Ahrens M. B., Jayaraman V., Looger L., Schreiter E., Science 2015, 347, 755–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Venkatachalam V., Brinks D., Maclaurin D., Hochbaum D., Kralj J., Cohen A. E., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 2529–2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.

- 7a. Tsien R. Y., Biochemistry 1980, 19, 2396–2404; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7b. Pethig R., Kuhn M., Payne R., Adler E., Chen T.-H., Jaffe L., Cell Calcium 1989, 10, 491–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schuddeboom W., Warman J. M., Biemans H., Meijer E., J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100, 12369–12373. [Google Scholar]

- 9.

- 9a. Papageorgiou G., Corrie J. E., Tetrahedron 2000, 56, 8197–8205; [Google Scholar]

- 9b. Riguet E., Bochet C. G., Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 5453–5456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Guo Y. M., Chen S., Shetty P., Zheng G., Lin R., Li W., Nat. Methods 2008, 5, 835–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhao Y. R., Zheng Q., Dakin K., Xu K., Martinez M. L., Li W. H., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 4653–4663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sabatini B. L., Oertner T. G., Svoboda K., Neuron 2002, 33, 439–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang S. S.-H., Denk W., Häusser M., Nat. Neurosci. 2000, 3, 1266–1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Maravall M., Mainen Z., Sabatini B., Svoboda K., Biophys. J. 2000, 78, 2655–2667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Adams S., Kao J. P., Grynkiewicz G., Minta A., Tsien R., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 3212–3220. [Google Scholar]

- 16.

- 16a. Diwu Z., Lu Y., Upson R. H., Zhou M., Klaubert D. H., Haugland R. P., Tetrahedron 1997, 53, 7159–7164; [Google Scholar]

- 16b. Kwan D. H., Chen H. M., Ratananikom K., Hancock S. M., Watanabe Y., Kongsaeree P. T., Samuels A. L., Withers S. G., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 300–303; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2011, 123, 314–317; [Google Scholar]

- 16c. Grimm J. B., Gruber T. D., Ortiz G., Brown T. A., Lavis L. D., Bioconjugate Chem. 2016, 27, 474–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Matsuzaki M., Ellis-Davies G. C., Nemoto T., Miyashita Y., Iino M., Kasai H., Nat. Neurosci. 2001, 4, 1086–1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chan J., Dodani S. C., Chang C. J., Nat. Chem. 2012, 4, 973–984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary