Abstract

We use data from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) to document the medical spending of Americans aged 65 and older. We find that medical expenses more than double between ages 70 and 90 and that they are very concentrated: the top 10 per cent of all spenders are responsible for 52 per cent of medical spending in a given year. In addition, those currently experiencing either very low or very high medical expenses are likely to find themselves in the same position in the future. We also find that the poor consume more medical goods and services than the rich and have a much larger share of their expenses covered by the government. Overall, the government pays for over 65 per cent of the elderly's medical expenses. Despite this, the expenses that remain after government transfers are even more concentrated among a small group of people. Thus, government health insurance, while potentially very valuable, is far from complete. Finally, while medical expenses before death can be large, on average they constitute only a small fraction of total spending, both in the aggregate and over the life cycle. Hence, medical expenses before death do not appear to be an important driver of the high and increasing medical spending found in the US.

Keywords: concentration of medical spending, persistence of medical spending, end‐of‐life medical spending, H51, I13, I14

Policy points

Those at the top of the income distribution in the US consume 71 per cent as much health care resources as those at the bottom of the distribution per year.

Those in the last calendar year of life are responsible for 4.9 per cent of total spending. In the last 12 months of life, average medical spending is $59,000, accounting for 16.8 per cent of spending at ages 65 and over and for 6.7 per cent of spending at all ages. Medical spending in the three years before death accounts for 13.4 per cent of aggregate medical spending.

The government pays for over 65 per cent of health care spending by the elderly, with Medicare accounting for the majority of this. Nearly 20 per cent is financed out‐of‐pocket and about 13 per cent by private insurance.

Medical spending by the elderly is highly concentrated. Individuals in the top 5 per cent of the distribution of total expenditures account for 35 per cent of all medical spending. Out‐of‐pocket expenditures are even more concentrated, with about half of expenditures made by the top 5 per cent of spenders.

Total spending is on average about $1,100 per year more for women than for men, due to higher expenditures on nursing homes for women.

The financing of health care varies dramatically by income. In the bottom income quintile, Medicare pays $9,500 a year and Medicaid $3,900, while private insurance covers just $900 and out‐of‐pocket spending is $2,500. In the top income quintile, Medicare pays $6,300 and Medicaid only $300, while private insurance pays $2,400 and out‐of‐pocket spending is $3,000.

Medical spending is very persistent over time, with those in the top quintile of spending in one year having a 54 per cent chance of being in the top quintile in the next year and a 48 per cent chance of being in the top quintile in two years’ time.

I. Introduction

We use data from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) to document the medical spending of people aged 65 and over in the United States. This paper is part of a series of studies examining the properties of individual‐level medical spending both across several data sets for a given country and across countries.1 The medical spending of the US population aged 65 and over is notable for a number of reasons.

First, the typical elderly American receives far more medical services than those of younger ages. In 2010, average medical expenditures for an American aged 65 or older were 2.6 times the national average.2 In the same year, people of 65 and older accounted for over one‐third of US medical spending. As the population continues to age, this fraction will likely grow. Given that much of the elderly's medical expenditures are financed by the government, their spending is of increasing fiscal importance. A particularly contentious issue is spending at the end of life.3 Even though studies have found that over a quarter of Medicare spending on the elderly is for end‐of‐life care,4 proposals to reform this spending have generated scepticism5 and sometimes strident resistance.6 As our results and the results of other papers in this issue suggest, end‐of‐life spending in the US is not unusually high relative to that in other countries.

A second notable feature of this population is that virtually every American aged 65 or older is eligible for Medicare, a government‐provided health insurance programme. Medicare pays much of the cost of short hospital stays, doctor visits and, since 2006, pharmaceuticals. This is in sharp contrast to the younger population. The majority of Americans younger than 65 are covered through employer‐provided health insurance, but many others are covered by privately‐purchased health insurance or government‐provided insurance. Moreover, because privately‐purchased insurance can be expensive, and because the eligibility criteria for government insurance are strict for the non‐elderly, many people younger than 65 are uninsured. A number of studies suggest that access to health care in the US is unequal across the income distribution.7 This inequality is likely more pronounced among the younger population than among the elderly, where Medicare mitigates disparities in health care access. In fact, the US health care system for those aged 65 and over looks much more similar to health care systems elsewhere in the OECD. Perhaps unsurprisingly, many of the patterns of medical spending we document in this paper are similar to the patterns documented for other countries. More surprisingly, however, many of the patterns we document in this paper are similar to the patterns documented in Pashchenko and Porapakkarm (this issue) for the under‐65 US population. For both the over‐ and under‐65 populations in the US and elsewhere, there is a modest negative correlation between income and total medical spending.

A third reason to study medical spending among retirees is that medical expenses provide an important motive for retirement saving.8 This saving not only affects wages and economic growth, but is an important policy concern in its own right. Given the policy debates surrounding the financing of medical spending in the US, better knowledge of the patterns of existing medical spending risk faced by the elderly is of value. Despite near‐universal health insurance for the population aged 65 and over, we show that many elderly people in the US still face the risk of catastrophic medical spending.

The MCBS links the administrative Medicare records to survey information from households. In addition to high‐quality data on Medicare payments, the MCBS contains spending data for other payers from its survey component.

We find that medical expenses more than double between ages 70 and 90, with most of the increase coming from nursing home spending. Medical expenses are very concentrated: the top 10 per cent of all spenders are responsible for 52 per cent of medical spending in a given year. We also find that those currently experiencing either very low or very high medical expenses are likely to find themselves in the same position in the future. These features of the data are consistent with individuals or households facing a small risk of large medical expenses, which, once incurred, tend to be persistent over time. Because it is hard to self‐insure against such risks by saving, they may be quite costly for consumers, especially if there are frictions in private health insurance markets. Government insurance mitigating these risks may thus be very valuable to consumers. This notwithstanding, and despite the fact the government pays for 67 per cent of the elderly's medical expenses, the expenses that remain after government transfers are even more concentrated among a small group of people. Hence, government health insurance, while potentially very valuable, is far from complete. This is in part because the government's Medicaid programme is the payer of last resort, contributing only after private funding has been exhausted. As a result, even though the poor on average consume more medical goods and services than the rich, they are responsible for a much smaller share of their costs. Finally, while medical expenses before death can be large, on average they constitute only a small fraction of total spending, both in the aggregate and over the life cycle. Therefore, medical expenses before death do not appear to be an important driver of the high and increasing medical spending found in the US.

The rest of the paper is organised as follows. Section II. briefly describes the health care system for older Americans. Section III. describes the MCBS data and compares them with administrative data. Section IV. documents the concentration of medical expenditures, both within a single year and across multiple years, and the concentration of medical spending across the income distribution. Section V. shows the evolution of medical expenses and their payers during the retirement period. Section VI. presents new estimates of medical spending in the last three years of life and Section VII. concludes.

II. Health care for the population aged 65 and over in the US

1. Institutional background

With some exceptions, US health care is privately provided. Most US hospitals are run either by non‐profit institutions, such as universities or religious organisations, or by private for‐profit companies. The employees of those hospitals, including doctors and nurses, are then paid by the hospitals. Hospitals, doctors and other health care providers are largely free to charge what they wish for their services. However, health care insurers (public and private) usually negotiate prices for their insurees.

We define a payer of health care as the final payer of billed medical goods and services. Thus we count a payment by a private insurer as a private insurance payment, despite the fact that an individual paid insurance premiums to obtain these insurance services. So if an individual paid $1 for insurance that paid $1 to a hospital, we will count ‘out‐of‐pocket spending’ as 0 and payments by private insurance as $1.

The main payer of health care amongst the elderly is Medicare, a federal programme that provides health insurance to almost every person aged 65 or over. Individuals covered by Medicare have the option of traditional Medicare, where Medicare pays the providers, or Medicare Advantage, where Medicare provides payments to health maintenance organisations, which then provide care. Under traditional Medicare, the government sets a schedule of payments for most services. In order to discourage the over‐provision of health care services, many health care treatments performed by hospitals are paid on the basis of the diagnosis rather than the treatment. Traditional Medicare pays for the great majority of the cost of short‐term hospital stays, 80 per cent of the cost of doctor visits and, since 2006, most of the costs associated with pharmaceuticals. Medicare Advantage pays for close to 100 per cent of the cost of hospital stays, doctor visits and pharmaceuticals.

Many older individuals have private insurance plans that cover medical expenses not covered by Medicare, such as the residual share of the costs of doctor visits. However, some forms of care are largely uninsured by either Medicare or private health insurance, with the most important category being nursing home spending. A large share of nursing home costs are paid out‐of‐pocket. Because nursing home stays are expensive – of the order of $77,000–88,000 a year in 2014 – most individuals will be impoverished by a long nursing home stay. Those made financially destitute will be covered by Medicaid, a means‐tested programme that is run jointly by the federal and state governments.9 In 2013, around 29 per cent of nursing home costs were paid out‐of‐pocket, while around 30 per cent were covered by Medicaid. Medicaid covers almost all the nursing home costs of poor, old recipients. More generally, Medicaid ends up financing 63 per cent of nursing home residents.10 In 2009, 74 per cent of Medicaid's transfers to the elderly were for long‐term care.11 In large part because of its role in funding nursing home care, Medicaid is the second most important public health insurance programme for the elderly in the US. Nonetheless, Medicaid is the payer of last resort, contributing only after private funding and Medicare support have been (nearly) exhausted.

The National Health Expenditure Accounts (NHEA), maintained by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), document how much is being spent on each type of health care service, as well as the payers of those services.12 Tables 1 and 2 use these data to summarise the sources and uses of personal health care spending. Personal health care spending measures the total amount spent on all treatments for all individuals. It excludes government administration, government public health activities, and investment. We focus on personal health care expenditure since it is the concept that the MCBS data are designed to measure. Moreover, the bulk – in 2013, 85 per cent – of total national health care expenditures go to personal health care.

Table 1.

Funding sources of the elderly's personal health care expenditures, 2010

| Payer | Type of expenditure | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitals | Professional services | Nursing home care | Retail drugs | Other | All | |

| Out‐of‐pocket | 1.1% | 9.4% | 28.2% | 18.6% | 27.9% | 13.2% |

| Private insurance | 13.4% | 18.6% | 7.8% | 23.4% | 3.8% | 13.3% |

| Medicaid | 6.8% | 2.1% | 29.7% | 1.3% | 21.9% | 11.1% |

| Medicare | 69.7% | 64.3% | 24.3% | 52.8% | 36.5% | 54.4% |

| Other | 9.0% | 5.6% | 10.0% | 4.0% | 10.0% | 8.0% |

Source: National Health Expenditure Accounts.

Table 2.

Percentage of personal health care expenditures, by payer and expenditure type: national data

| Aged 65 and over | Aged under 65 | Whole population | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2010 | 1970 | 1990 | 2010 | 2013 | |

| Payers | ||||||

| Out‐of‐pocket | 13.2% | 14.3% | 39.6% | 22.5% | 13.9% | 13.7% |

| Private insurance | 13.3% | 45.2% | 22.2% | 33.3% | 34.4% | 34.3% |

| Medicaid | 11.1% | 19.5% | 7.9% | 11.3% | 16.7% | 16.6% |

| Medicare | 54.4% | 5.9% | 11.6% | 17.4% | 22.3% | 22.3% |

| Other | 8.0% | 15.1% | 18.7% | 15.6% | 12.7% | 13.0% |

| Expenditure types | ||||||

| Nursing home care | 16.2% | 1.5% | 6.3% | 7.3% | 6.5% | 6.3% |

| Hospitals | 35.3% | 38.0% | 43.1% | 40.6% | 37.1% | 38.0% |

| Professional services | 23.2% | 35.9% | 31.4% | 33.7% | 31.6% | 31.5% |

| Retail drugs | 10.3% | 12.4% | 8.7% | 6.5% | 11.7% | 11.0% |

| Other | 15.0% | 12.1% | 10.5% | 11.9% | 13.1% | 13.2% |

| Total personal health care expenditure ($ billion) | 800 | 1,550 | 310 | 990 | 2,350 | 2,500 |

Note: Dollar values are adjusted to 2014 dollars.

Source: National Health Expenditure Accounts.

Table 1 shows how the personal health care expenditures of the elderly were funded in 2010, the most recent year the age‐specific data are available in the CMS data set. Each column of the table corresponds to a particular type of service: hospital care; professional services such as doctor and dental visits; nursing home care; drugs; and other.13 Each row corresponds to a payer: out‐of‐pocket; private health insurance; Medicaid; Medicare; and other. The table shows the fraction of each expenditure subtotal paid by each payer. For example, the first column shows that only 1 per cent of the costs of hospital care are paid out‐of‐pocket, while almost 70 per cent of the costs are covered by Medicare. In fact, Medicare is the largest payer for every type of expenditure with the exception of nursing home care. The final column of Table 1 shows that Medicare covers well over half of the elderly's medical expenditures. Private health insurance, Medicaid and out‐of‐pocket expenditures each cover between 11 and 13 per cent of the total.

2. Trends in health care expenditures

Table 2 compares the spending of the elderly with that of the general population. The top panel shows the shares of medical spending covered by different payers. The first column in this panel repeats the final column of Table 1. The second column of Table 2 shows the equivalent to the first column for the under‐65 population and the remaining four columns show results for the entire US population for 1970, 1990, 2010 and 2013. While Medicare pays a much bigger share of health care expenditures for the population aged 65 and over than for the population as a whole, in 2010 the share spent out‐of‐pocket barely falls after age 64. Instead, the rise in Medicare expenditures after age 64 mostly displaces private insurance expenditures. The second panel of Table 2 shows the shares of total medical spending across service categories. The biggest changes in expenditure shares for those aged 65 and over are a rise in nursing home care and a fall in professional services such as doctor visits.

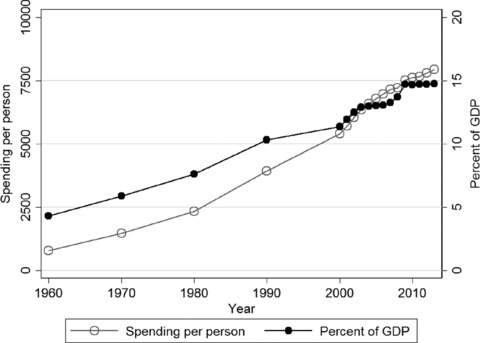

As is well known, the US spends large and increasing amounts on medical care. The bottom panel of Table 2 shows that in 2013 personal health care expenditures amounted to $2.5 trillion in 2014 dollars, representing 14.7 per cent of GDP. This translates to $7,930 per person. Figure 1 shows personal health care spending in the US, both per person and as a percentage of GDP, from 1960 to 2013. By either measure, health care spending has risen dramatically. Table 2 reveals that while the shares of spending going to each category have been fairly stable over time, the share of spending covered out‐of‐pocket has fallen by nearly two‐fifths. For most of this period, per‐capita expenditures on the elderly have grown more rapidly than expenditures on the young. Meara, White and Cutler (2004, exhibit 4) calculate that in 1963, average expenditures in the population aged 65 and over were 2.4 times the expenditures of those under 65. In 2000, the ratio had risen to 4.4. The authors also find, however, that this trend has reversed in recent decades, and per‐capita expenditures on the elderly are now growing more slowly than those on the young. The spending ratio calculated with the National Health Expenditure Accounts has fallen from 3.7 in 2002 to 3.4 in 2010.

Figure 1.

Personal health care expenditures for the whole population: per person (2014 dollars, left‐hand scale) and as a percentage of GDP (right‐hand scale)

III. The MCBS data set

1. Description

Our principal data source is the 1996 to 2010 waves of the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey. The MCBS is a nationally representative survey of disabled and elderly (aged 65 and over) Medicare beneficiaries.14 Although the sample misses elderly individuals who are not Medicare beneficiaries, virtually everyone aged 65 and over is a beneficiary. The survey contains an over‐sample of beneficiaries older than 80 and disabled individuals younger than 65. We exclude disabled individuals younger than 65, and use population weights throughout.

MCBS respondents are interviewed up to 12 times over a four‐year period and are asked about (and matched to administrative data on) health care utilisation over three of the four years, forming panels on medical spending for up to three years. We aggregate the data to an annual level. These sample selection procedures leave us 66,790 different individuals who contribute 152,193 person‐year observations.

The MCBS's unit of analysis is an individual. Respondents are asked about health status, income, health insurance, and health care expenditures paid out‐of‐pocket, by Medicaid, by Medicare, by private insurance and by other sources. The MCBS survey data are then matched to Medicare records. For this reason, the medical spending data are of particularly high quality.

The key variable of interest is medical spending. This includes the cost of hospital stays, doctor visits, pharmaceuticals, nursing home care and other long‐term care. The MCBS's medical expenditure measures are created through a reconciliation process that combines survey information with Medicare administrative files. As a result, the MCBS contains accurate data on Medicare payments and fairly accurate data on out‐of‐pocket, Medicaid, and other insurance payments. Out‐of‐pocket expenses include hospital, doctor and other bills paid out‐of‐pocket, but do not include insurance premiums paid out‐of‐pocket. Because the MCBS includes information on people who enter a nursing home or die, its medical spending data are very comprehensive.

In the MCBS, individuals are asked to report ‘… your and your spouse's total income before taxes during the past 12 months’. Respondents are asked to provide an income interval, rather than an exact dollar amount. The MCBS income measure appears to include household income, including transfer and asset income. In contrast, medical spending and most other variables in the MCBS are measured at the individual level. To make the income data compatible with the other variables, we rescale household income by standardised household size:15

When taking logs, we bottom‐code income and medical spending.16 We adjust all dollar amounts to 2014 dollars using the personal consumption expenditure index.

De Nardi, French and Jones (2013) benchmark the MCBS data to survey data from the Assets and Health Dynamics of the Oldest Old (AHEAD) data set and find that the MCBS and AHEAD match up well against each other, with the MCBS possibly being more accurate.17

2. Comparisons with administrative data

Although there is no high‐quality administrative information for out‐of‐pocket and private insurance payments for the population aged 65 and over, we can compare the MCBS data with administrative data from the Medicare and Medicaid programmes.

The first set of columns in Table 3 compares Medicare enrolment and average Medicare expenditures in the MCBS with the corresponding values in the aggregate data from the Census Bureau. It shows that, when using population weights, the number of Medicare beneficiaries and expenditures per beneficiary line up closely with the aggregate statistics. Over the 1996–2010 period, MCBS Medicare enrolment for the population aged 65 and over averages 36.7 million, only 3 per cent more than the average of 35.8 million from aggregate data. Over the same period, expenditures per beneficiary in the MCBS average $7,670, 14 per cent smaller than the value of $8,970 in the official statistics.18 The expenditure match weakens over time, as mean expenditures in the MCBS go from 92 per cent of the data in 1996 to 81 per cent of the data in 2010. We are not sure of the source of the decline in the quality of the match.

Table 3.

Medicare and Medicaid enrolment and expenditures for the population aged 65 and over: comparisons

| Medicare | Medicaid (Medicaid and Medicare dual‐eligibles only) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCBS | US Census Bureau | MCBS | MSIS | ||||||

| Population (million) | Mean expenditure ($) | Population (million) | Mean expenditure ($) | Population (million) | Mean expenditure ($) | Adjusted mean expenditurea ($) | Population (million) | Mean expenditure ($) | |

| 1996 | 34.8 | 6,430 | 33.4 | 6,970 | 4.71 | 9,800 | 10,510 | ‐ | ‐ |

| 1997 | 34.8 | 6,480 | 33.7 | 7,380 | 4.68 | 9,830 | 10,550 | ‐ | ‐ |

| 1998 | 34.9 | 6,170 | 33.8 | 7,380 | 4.64 | 9,590 | 10,300 | ‐ | ‐ |

| 1999 | 35.0 | 6,450 | 33.9 | 7,160 | 4.65 | 9,380 | 10,100 | 4.48 | 12,490 |

| 2000 | 35.1 | 6,650 | 34.3 | 7,120 | 4.80 | 9,830 | 10,540 | 4.60 | 13,270 |

| 2001 | 35.5 | 7,030 | ‐ | ‐ | 4.90 | 9,990 | 10,760 | 4.76 | 13,730 |

| 2002 | 35.9 | 7,490 | ‐ | ‐ | 5.09 | 10,100 | 10,940 | 5.12 | 13,740 |

| 2003 | 36.2 | 7,510 | 35.0 | 8,240 | 5.16 | 9,810 | 10,690 | 5.43 | 13,530 |

| 2004 | 36.3 | 7,690 | 35.4 | 8,590 | 5.39 | 9,560 | 10,530 | 5.47 | 14,040 |

| 2005 | 36.6 | 7,880 | 35.8 | 9,210 | 5.51 | 9,940 | 11,050 | 5.59 | 14,120 |

| 2006 | 36.9 | 8,640 | 36.3 | 9,910 | 5.38 | 8,760 | 9,980 | 5.66 | 12,340 |

| 2007 | 37.8 | 8,990 | 37.0 | 10,890 | 5.38 | 8,940 | 10,200 | 5.49 | 12,220 |

| 2008 | 38.7 | 9,110 | 37.9 | 10,750 | 5.46 | 8,760 | 10,010 | 5.58 | 12,410 |

| 2009 | 39.6 | 9,210 | 38.8 | 11,460 | 5.68 | 7,980 | 9,240 | 5.64 | 12,240 |

| 2010 | 40.6 | 9,340 | 39.6 | 11,530 | 5.73 | 8,820 | 10,240 | 5.85 | 12,560 |

Adjusted mean expenditure is expenditure plus estimated Medicaid payments to Medicare Part B.

Note: ‘‐’ denotes that the data are unavailable. MSIS is the Medicaid Statistical Information System. See footnotes 18 and 19 for details on construction of the aggregate Medicare and Medicaid statistics. Adjusted to 2014 dollars.

The MCBS uses administrative data to determine whether an individual is receiving Medicaid benefits, but it does not have administrative data on the value of those payments. In order to assess the quality of the Medicaid expenditure data in the MCBS, we benchmark them against administrative data from the Medicaid Statistical Information System (MSIS). Table 3 shows that the MCBS also accurately measures the share of the Medicare population aged 65 and over receiving Medicaid payments, after adjusting the MSIS estimates to include only those receiving Medicare, and not the full population, a group sometimes known as ‘dual‐eligibles’.19 According to MCBS data, there were on average 5.26 million aged Medicaid beneficiaries over the 1999–2010 period, versus 5.31 million aged Medicaid beneficiaries in the MSIS data, an underestimate of 1 per cent. However, for the same period, MCBS Medicaid payments for the population aged 65 and over are on average 29 per cent smaller than the MSIS data suggest. Part of this difference is explained by the MCBS payment data not including Medicaid payments to Medicare. After adjusting the MCBS estimates to also include estimated Medicaid contributions to Medicare, the MCBS captures 79 per cent of all Medicaid spending. As with the Medicare data, the discrepancy between the MCBS data and the administrative data is growing over time.20

IV. Medical expenditures in the cross‐section, over time and across the income distribution

1. Cross‐sectional distribution

The top panel of Table 4 shows a breakdown of medical spending in the MCBS among payers: out‐of‐pocket; private insurance; uncollected liabilities for treatments that have not been paid for; and government. The bottom panel shows a breakdown of spending among expenditure categories: nursing home care; hospital spending, by inpatients and outpatients; professional services; pharmaceutical costs; and home help and hospice care. Both panels use data from all waves.

Table 4.

Percentage of total expenditures, by payer, expenditure type and gender: MCBS data

| All | Men | Women | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Payers | |||

| Out‐of‐pocketa | 19.4% | 17.2% | 21.0% |

| Private insurance | 12.5% | 14.3% | 11.3% |

| Uncollected liabilities | 1.5% | 1.7% | 1.4% |

| Government | 66.5% | 66.9% | 66.3% |

| Medicaid | 9.4% | 6.0% | 11.6% |

| Medicare | 54.7% | 57.5% | 52.8% |

| Other government | 2.5% | 3.4% | 1.9% |

| Expenditure types | |||

| Nursing home care | 20.6% | 14.4% | 24.8% |

| Hospitals | 34.7% | 40.0% | 31.1% |

| Inpatients | 25.8% | 29.8% | 23.0% |

| Outpatients | 8.9% | 10.1% | 8.0% |

| Professional services | 27.1% | 28.9% | 25.9% |

| Drugs | 13.1% | 13.1% | 13.2% |

| Home help and hospice | 4.5% | 3.7% | 5.0% |

| Premiums to total expenditure ratio b | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.13 |

Includes all medical bills paid out‐of‐pocket, but does not include insurance premiums.

Total insurance premiums paid by individuals divided by total billed medical expenses.

Note: This table reports total spending in each category divided by total overall medical spending.

The percentages shown in Table 4 are constructed in the same way as those in Table 2. Mean spending in each category is divided by the mean of total medical spending, so that the percentages represent the distribution of aggregate medical spending.21 The percentages calculated for the MCBS are fairly similar to those for the aggregate data for the elderly in 2010 shown in Table 2. In both tables, the government covers over 65 per cent of the elderly's medical expenditures. The fraction of costs paid out‐of‐pocket is higher in the MCBS (19.4 per cent) than in the aggregate statistics (13.2 per cent), while the fraction covered by Medicaid is lower. Drug expenditures are relatively higher in the MCBS. These differences may in part reflect the lack of Medicare drug coverage in the years preceding 2006.

The two most notable differences between men and women in Table 4 involve Medicaid and nursing home care. The fraction of medical expenditures covered by Medicaid is nearly twice as large for women as it is for men. Similarly, women spend nearly twice as much on nursing home care as men. This is consistent with Table 1, which shows that Medicaid plays a particularly large role in funding nursing home care. Table 4 also shows that, in the aggregate, men rely more on Medicare (57.5 per cent) and spend relatively more on hospital care (40.0 per cent) than women (52.8 per cent and 31.1 per cent, respectively). This too is consistent with Table 1, which shows that Medicare reimburses nearly 70 per cent of hospital costs.

The last row of Table 4 presents the ‘premiums to total expenditure ratio’, which is calculated by dividing total private insurance premiums by total medical spending. Many elderly individuals have ‘Medigap’ health insurance plans that pay for items such as Medicare co‐payments for doctor visits. As it turns out, this ratio is 13 per cent (for all), which is very close to the 12.5 per cent share of aggregate costs paid for by private insurers, shown in the top panel of the table.

Table 5 shows the cross‐sectional distribution of medical spending by expenditure type and for the most important payer types, with the results for each spending type sorted by that type's spending. The top panel shows the distributions of total medical spending, total spending excluding nursing home care, and spending on hospitals. Individuals in the top 5 per cent of the total expenditure distribution spend $97,880 apiece, nearly seven times the overall average of $14,120, and constitute nearly 35 per cent of all medical spending. For hospitals, 50 per cent of individuals have almost zero spending and those in the top 5 per cent of the distribution account for over 52 per cent of the spending. The bottom panel of Table 5 shows results for out‐of‐pocket expenditures, Medicare and Medicaid. Although out‐of‐pocket expenditures are on average much lower than total expenditures, the distribution of out‐of‐pocket expenditures is more concentrated. Almost half of the out‐of‐pocket expenditure is made by the top 5 per cent. Even with public and private insurance, out‐of‐pocket medical expenditure risk is significant.

Table 5.

Medical spending percentiles: MCBS

| By expenditure type | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spending percentile | All | All (excluding nursing homes) | Hospitals | |||

| Average spending ($) | % of total | Average spending ($) | % of total | Average spending ($) | % of total | |

| All | 14,120 | 100.0 | 11,210 | 100.0 | 4,890 | 100.0 |

| 95–100% | 97,880 | 34.6 | 76,860 | 34.3 | 51,400 | 52.5 |

| 90–95% | 48,890 | 17.3 | 34,360 | 15.3 | 18,880 | 19.3 |

| 70–90% | 20,540 | 29.1 | 16,080 | 28.7 | 6,030 | 24.6 |

| 50–70% | 7,750 | 11.0 | 6,980 | 12.4 | 760 | 3.1 |

| 0–50% | 2,250 | 8.0 | 2,080 | 9.3 | 50 | 0.5 |

| By payer | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spending percentile | Out‐of‐pocket | Medicare | Medicaid | |||

| Average spending ($) | % of total | Average spending ($) | % of total | Average spending ($) | % of total | |

| All | 2,740 | 100.0 | 7,720 | 100.0 | 1,320 | 100.0 |

| 95–100% | 26,930 | 49.1 | 67,560 | 43.7 | 24,980 | 94.7 |

| 90–95% | 6,700 | 12.2 | 28,370 | 18.4 | 1,360 | 5.2 |

| 70–90% | 2,920 | 21.3 | 10,280 | 26.6 | 10 | 0.1 |

| 50–70% | 1,360 | 9.9 | 2,980 | 7.7 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 0–50% | 420 | 7.6 | 550 | 3.5 | 0 | 0.0 |

Note: The results for each expenditure type or payer are sorted by that expenditure type's or payer's spending. Adjusted to 2014 dollars.

To examine how the cross‐sectional distribution of medical spending differs by gender, we sort medical spending for men and women into quintiles, calculating the quintiles separately for each gender. Table 6 shows mean medical spending within each spending quintile. Total expenditures are higher for women than for men at every spending quintile. This difference is largely due to expenditures on nursing home care. Once we exclude nursing home care, men have higher expenditures on average ($11,540 versus $10,970) and in the top two spending quintiles. Men in particular incur higher hospital costs ($5,390 versus $4,530), consistent with Table 4. However, the overall shapes of the medical spending distributions are similar across genders.

Table 6.

Mean medical expenditures, by spending quintile and gender

| Spending quintile | Total expenditure | Total expenditure (excluding nursing homes) | Hospitals | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Men | Women | All | Men | Women | All | Men | Women | |

| All | 14,120 | 13,480 | 14,590 | 11,210 | 11,540 | 10,970 | 4,890 | 5,390 | 4,530 |

| Bottom | 740 | 600 | 860 | 670 | 560 | 760 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Second | 2,640 | 2,390 | 2,840 | 2,450 | 2,270 | 2,580 | 30 | 20 | 40 |

| Third | 5,430 | 5,100 | 5,670 | 4,980 | 4,820 | 5,090 | 310 | 270 | 330 |

| Fourth | 11,690 | 11,090 | 12,170 | 10,090 | 10,100 | 10,090 | 2,110 | 2,230 | 2,030 |

| Top | 50,110 | 48,250 | 51,440 | 37,870 | 39,970 | 36,330 | 22,030 | 24,410 | 20,260 |

Note: Adjusted to 2014 dollars.

2. Distribution by income

To document how medical spending is distributed by income, Table 7 displays mean income and medical expenditures by gender in the MCBS, broken down by income quintile. Low‐income people consume more medical resources per year. Of course, this higher spending of those with low incomes would be at least partly offset if we accounted for the fact that those at the top of the income distribution live longer than those at the bottom.22 The observation also does not take into account the fact that those at the top of the income distribution tend to be healthy and have less medical need than those at the bottom of the distribution. What the table shows, however, is that society does spend a fairly large amount of health care resources on low‐income people in the US.

Table 7.

Income and medical expenditures, by income quintile and gender

| Income quintile | Mean income | Mean expenditure | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Men | Women | All | Men | Women | |

| All | 28,280 | 31,920 | 25,600 | 14,120 | 13,480 | 14,590 |

| Bottom | 8,000 | 8,700 | 7,630 | 17,410 | 16,180 | 18,020 |

| Second | 14,260 | 16,060 | 13,250 | 14,940 | 14,050 | 15,890 |

| Third | 20,620 | 23,150 | 18,890 | 13,180 | 12,720 | 13,380 |

| Fourth | 30,080 | 33,410 | 27,650 | 12,650 | 12,120 | 13,050 |

| Top | 68,930 | 79,080 | 60,910 | 12,430 | 12,360 | 12,620 |

| Income quintile | Mean expenditure (excluding nursing homes) | Mean hospitals | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Men | Women | All | Men | Women | |

| All | 11,210 | 11,540 | 10,970 | 4,890 | 5,390 | 4,530 |

| Bottom | 11,890 | 12,190 | 11,650 | 5,660 | 6,280 | 5,300 |

| Second | 11,490 | 11,990 | 11,420 | 5,370 | 6,080 | 5,070 |

| Third | 10,990 | 11,240 | 10,680 | 4,840 | 5,170 | 4,430 |

| Fourth | 10,900 | 11,020 | 10,730 | 4,430 | 4,720 | 4,190 |

| Top | 10,800 | 11,280 | 10,370 | 4,180 | 4,680 | 3,670 |

Note: Adjusted to 2014 dollars.

The higher spending on the poor consists mostly of greater expenditure on nursing homes. When nursing home care is excluded, the income gradient is much less pronounced. Excluding nursing home expenditures, men consume more medical resources than women at each income quintile. But because women use more nursing home care than men, they have higher total medical spending at every income quintile.

The top panel of Table 8 shows how these expenditures are funded. Medicare is an important payer at every income quintile, spending an average of $9,490 on individuals in the lowest income quintile and $6,270 on those in the top one. Out‐of‐pocket spending is almost constant across the income distribution. De Nardi, French and Jones (2013) find that high‐income people spend significantly more out‐of‐pocket than low‐income people: singles at the top of the income distribution spend almost twice as much out‐of‐pocket as those at the bottom. The difference in results comes from the measure of out‐of‐pocket spending. De Nardi et al. include insurance payments, which is the relevant measure for measuring the spending risk paid by a household, whereas here we include only out‐of‐pocket payers to providers, since we measure everything from the standpoint of the payer of a particular medical bill. The out‐of‐pocket payments in this paper are lower than those in Fahle, McGarry and Skinner (this issue). However, most of the difference is due to the fact that they include out‐of‐pocket insurance premiums whereas we exclude them. French, Jones and McCauley (2016) show that MCBS out‐of‐pocket medical spending (including insurance premiums) is about 20 per cent higher than that in the Health and Retirement Study. Medicaid pays an average of $3,900 to those in the bottom quintile and only $270 to those in the top one, while private insurance pays an average of $2,420 a year to those in the top quintile and only $860 to those in the bottom one.

Table 8.

Mean medical expenditure, by income quintile and payer/expenditure type

| All | Income quintile | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bottom | Second | Third | Fourth | Top | ||

| Income | 28,280 | 8,000 | 14,260 | 20,620 | 30,080 | 68,930 |

| Payers | ||||||

| All payers | 14,120 | 17,410 | 14,940 | 13,180 | 12,650 | 12,430 |

| Out‐of‐pocket | 2,740 | 2,480 | 2,780 | 2,700 | 2,750 | 3,000 |

| Medicare | 7,720 | 9,490 | 8,430 | 7,460 | 6,950 | 6,270 |

| Medicaid | 1,320 | 3,900 | 1,590 | 570 | 260 | 270 |

| Government other | 360 | 510 | 460 | 320 | 270 | 230 |

| Private insurance | 1,760 | 860 | 1,450 | 1,920 | 2,170 | 2,420 |

| Uncollected liability | 220 | 170 | 230 | 210 | 230 | 240 |

| Expenditure types | ||||||

| All | 14,120 | 17,410 | 14,940 | 13,180 | 12,650 | 12,430 |

| Nursing home care | 2,910 | 5,520 | 3,450 | 2,190 | 1,750 | 1,630 |

| All (excl. nursing homes) | 11,210 | 11,890 | 11,490 | 10,990 | 10,900 | 10,800 |

| Professional services | 3,830 | 3,510 | 3,580 | 3,750 | 4,030 | 4,270 |

| Drugs | 1,860 | 1,780 | 1,810 | 1,860 | 1,940 | 1,900 |

| Home help and hospice | 630 | 930 | 740 | 550 | 490 | 450 |

| Hospitals | 4,890 | 5,660 | 5,370 | 4,840 | 4,430 | 4,180 |

| Inpatient | 3,640 | 4,420 | 4,020 | 3,610 | 3,240 | 2,920 |

| Outpatient | 1,250 | 1,250 | 1,350 | 1,220 | 1,190 | 1,250 |

Note: Adjusted to 2014 dollars.

The bottom panel of Table 8 shows a breakdown of expenditures by service item for each income quintile. Those at the bottom of the income distribution receive more medical services ($17,410) than those at the top ($12,430). Interestingly, this difference seems to be mainly driven by nursing home care expenditures. Once nursing home care is excluded, the difference in spending between those at the bottom ($11,890) and those at the top ($10,800) almost disappears.

3. Correlation over time

The distribution of cumulative medical spending depends not only on the distribution of spending at each age but also on its persistence: if an individual has high medical spending this year, how likely are they to have high medical spending next year as well? Relative to the concentration of medical spending over a single year, there has been much less work on the concentration of medical spending over multiple years. Spillman and Lubitz (2000), Lubitz et al. (2003) and Alemayehu and Warner (2004) describe how lifetime expenditures vary by health and time of death, but they do not describe the expenditures’ concentration. For the US, most of the research has focused on the persistence of medical spending across multiple years.23

Feenberg and Skinner (1994) and French and Jones (2004) analyse the persistence of out‐of‐pocket medical spending. Table 9 shows correlations, both in levels and in logs, of all medical spending, all spending excluding nursing home care, and hospital spending, one and two years apart, i.e. it shows the correlation of medical spending in year t with medical spending in years t+1 and t+2. In our analysis, we include everyone who was alive one year (respectively, two years) after the initial period and we exclude those who died during that time. The correlation of total medical spending between adjacent years is 0.57 in levels and 0.61 in logs. The correlation of total medical spending between years two years apart is 0.40 in levels and 0.53 in logs. Although medical spending is not perfectly correlated over time, its serial correlation is still relatively high two years later. Thus, even on a lifetime basis, there is likely to be a large amount of concentration of medical spending. The correlation drops slightly when nursing home care is excluded, and it drops considerably when we only consider hospital spending. Table A3 in the online appendix shows the results disaggregated by gender.

Table 9.

Correlation of medical spending in year t with spending in years t+1 and t+2

| Total spending in levels | Total spending in logs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t+1 | t+2 | t+1 | t+2 | ||

| All | 0.57 | 0.40 | All | 0.61 | 0.53 |

| All (excluding nursing homes) | 0.45 | 0.28 | All (excluding nursing homes) | 0.56 | 0.48 |

| Hospitals | 0.27 | 0.19 | Hospitals | 0.30 | 0.25 |

Correlation coefficients provide a single linear measure of co‐movement. Table 10 presents transition matrices, which allow for more flexible relationships across time periods and spending bins. The top panel displays one‐year transition probabilities and the bottom panel displays two‐year probabilities for movements between the total medical spending quintiles shown in Table 6. The row j, column k element of a transition matrix gives the probability that an individual is in spending quintile k in year t+1 or t+2, given that the individual was in spending quintile j in year t. The tables show that medical spending is concentrated in the top and bottom tails of the distribution. Conditional on being in the top quintile of the medical spending distribution in a given year, there is a 53.8 per cent chance of being in the top quintile in the following year and a 48.2 per cent chance of being in the top quintile in two years’ time. Tables A4 and A5 in the online appendix report the transition matrices for total expenditures net of nursing home costs and for hospital expenditures, respectively.

Table 10.

Transition matrices for total medical expenditure

| One‐year transitions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quintile in current year | Quintile next year | ||||

| Bottom | Second | Third | Fourth | Top | |

| Bottom | 61.9 | 17.8 | 8.9 | 6.5 | 5.0 |

| Second | 24.1 | 36.6 | 19.4 | 12.1 | 7.8 |

| Third | 9.8 | 25.4 | 32.3 | 21.0 | 11.5 |

| Fourth | 6.0 | 13.6 | 25.9 | 34.2 | 20.3 |

| Top | 3.5 | 6.6 | 11.9 | 24.3 | 53.8 |

| Two‐year transitions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quintile in current year | Quintile two years ahead | ||||

| Bottom | Second | Third | Fourth | Top | |

| Bottom | 58.3 | 17.6 | 10.3 | 7.5 | 6.3 |

| Second | 26.0 | 32.2 | 19.0 | 12.7 | 10.2 |

| Third | 11.9 | 25.6 | 28.3 | 20.5 | 13.8 |

| Fourth | 7.3 | 15.3 | 25.7 | 31.0 | 20.6 |

| Top | 4.7 | 8.5 | 13.5 | 25.1 | 48.2 |

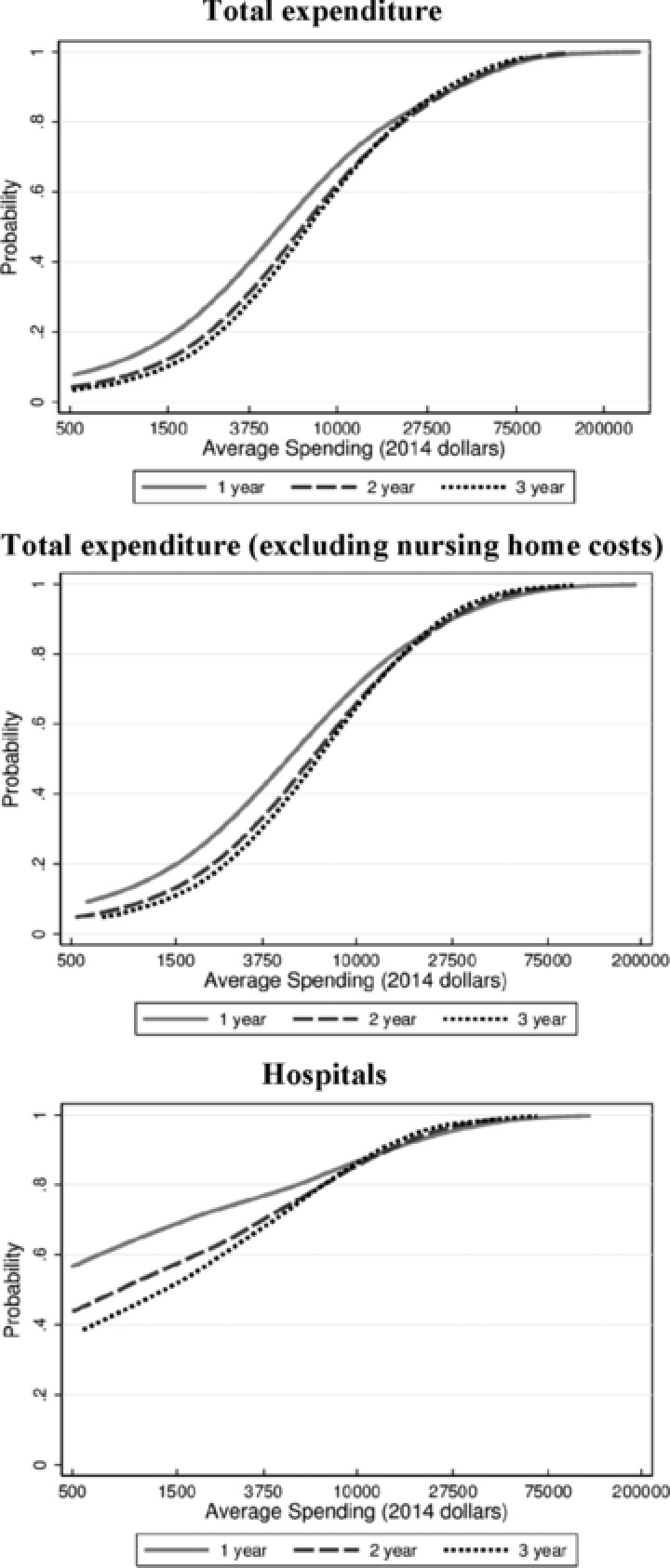

Figure 2 displays a more direct measure of how accumulated medical spending is concentrated, by displaying the cumulative distribution function (CDF) for medical spending averaged over one‐, two‐ and three‐year periods. Medical spending is highly concentrated even when the data are averaged across three years. For this to be the case, medical spending must be persistent across time, consistent with the preceding results.

Figure 2.

CDFs of medical expenditures, averaged over one, two and three years

Table 11 displays more measures of the concentration of medical spending over different durations – namely, the Gini coefficient24 and the shares of total medical spending, total spending excluding nursing home costs, and hospital spending for the top 1 per cent and top 10 per cent of spenders. Again, results are shown for one‐, two‐ and three‐year periods. Although medical spending becomes less concentrated as the averages cover more years, it remains very concentrated even at three years.

Table 11.

Measures of the concentration of medical spending over one, two and three years

| Medical spending averaged over: | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 year | 2 years | 3 years | |

| All | |||

| Gini coefficient for medical spending | 0.67 | 0.61 | 0.58 |

| Percentage spent by top 1% of spenders | 11.9% | 9.4% | 8.7% |

| Percentage spent by top 10% of spenders | 52.0% | 45.5% | 42.9% |

| All (excluding nursing homes) | |||

| Gini coefficient for medical spending | 0.64 | 0.57 | 0.54 |

| Percentage spent by top 1% of spenders | 12.9% | 10.0% | 8.9% |

| Percentage spent by top 10% of spenders | 49.6% | 42.1% | 38.7% |

| Hospitals | |||

| Gini coefficient for medical spending | 0.84 | 0.77 | 0.72 |

| Percentage spent by top 1% of spenders | 21.4% | 16.0% | 14.0% |

| Percentage spent by top 10% of spenders | 71.8% | 59.1% | 53.3% |

V. Average medical spending over the life cycle

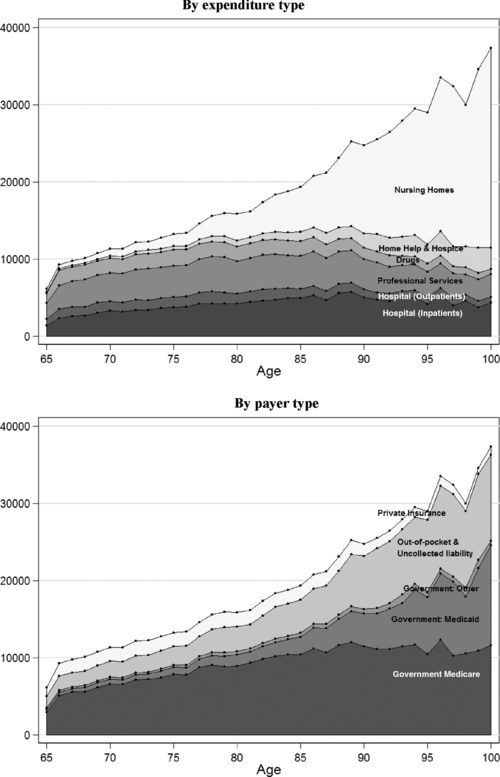

Figure 3 shows life‐cycle profiles of mean total medical spending. The two graphs in this figure plot spending profiles, first by expenditure type and then by payer.25 The estimates show that average medical spending exceeds $25,000 per year for those in their 90s. The top panel shows this is almost entirely due to nursing home expenditure. In fact, most other forms of expenditure fall with age after age 90. The bottom panel shows medical spending by payer. Given that nursing home care is mostly paid either out‐of‐pocket or by Medicaid and that nursing home spending rises quickly with age, it should come as no surprise that most of the increase in spending with age is paid either out‐of‐pocket or by Medicaid.

Figure 3.

Average total medical expenditures over the life cycle

An interesting question is to what extent the rise in medical expenses with age is due to the fact that people require more expensive medical services at older ages and to what extent it is due to large medical expenditures right before death. Yang, Norton and Stearns (2003) argue that medical spending in the US increases with age primarily because mortality rates increase with age and end‐of‐life expenditures are high. Other papers reach similar conclusions using data from different countries. For instance, Zweifel, Felder and Meiers (1999) use Swiss data, Seshamani and Gray (2004) use data from England and Polder, Barendregt and van Oers (2006) use data from the Netherlands. Interestingly, de Meijer et al. (2011) use Dutch data to find that time‐to‐death predicts long‐term care expenditures primarily by capturing the effects of disability. Yang et al. (2003) find that inpatient expenditures incurred near the end of life are higher at younger ages, while long‐term care expenditures rise with age. Braun, Kopecky and Koreshkova (2015) find that total end‐of‐life costs rise with age. Scitovsky (1994), Spillman and Lubitz (2000) and Levinsky et al. (2001) have also studied this question.

VI. Medical spending before death

It is often argued that people in the US spend too much on health care at the end of their lives. A number of studies have shown that end‐of‐life spending is significant. For example, Hoover et al. (2002) find that 22 per cent of all medical spending in the MCBS is for those in the last 12 months of life.26 Here we revisit and update their estimates. We estimate medical spending in the calendar year of death and in the two years before death. We also compare medical spending before death with total aggregate medical spending.

Table 12 presents key facts on medical spending in the final three years of life, relative to the medical spending of the whole population. The top panel displays aggregate statistics on medical spending and mortality for the US in 2008 that are useful for making these calculations. National statistics for spending come from the aggregate NHEA data. The rightmost column displays corresponding statistics from the MCBS. Data on mortality come from the National Vital Statistics Reports.27 The top panel of the table shows that the MCBS matches the aggregate spending statistics reasonably well and that it matches mortality statistics very well, giving us additional confidence in the data.

Table 12.

Medical spending in the last years of life

| Aggregate medical spending and mortality | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total population | Population aged 65 and over | ||

| National Stats | National Stats | MCBS | |

| Personal health care expenditure | |||

| Mean spending per person ($) | 7,220 | 19,110 | 15,570 |

| Aggregate spending ($ billion) | 2,190 | 740 | 600 |

| Mortality | |||

| Deaths (million) | 2.47 | 1.80 | 1.71 |

| Medical spending in the last years of life | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean spending ($) | As a percentage of aggregate spending | |||

| Total population | Population aged 65 and over | |||

| National Stats | National Stats | MCBS | ||

| Last years of life from data | ||||

| Year of death | 43,030 | 4.9% | 10.5% | 12.2% |

| Hospitals | 21,650 | 2.4% | 5.3% | 6.1% |

| Nursing home care | 9,150 | 1.0% | 2.2% | 2.6% |

| Second‐to‐last year | 42,810 | 4.8% | 10.4% | 12.2% |

| Hospitals | 13,790 | 1.6% | 3.4% | 3.9% |

| Nursing home care | 14,490 | 1.6% | 3.5% | 4.1% |

| Third‐to‐last year | 32,860 | 3.7% | 8.0% | 9.3% |

| Hospitals | 8,560 | 1.0% | 2.1% | 2.4% |

| Nursing home care | 12,290 | 1.4% | 3.0% | 3.5% |

| Sum of last three years | 118,690 | 13.4% | 28.9% | 33.7% |

| Hospitals | 44,000 | 5.0% | 10.7% | 12.5% |

| Nursing home care | 35,920 | 4.0% | 8.7% | 10.2% |

| Hoover et al. ( 2002 ) method | ||||

| Final 12 months | 59,100 | 6.7% | 14.4% | 16.8% |

| Hospitals | 26,870 | 3.0% | 6.5% | 7.6% |

| Nursing home care | 14,990 | 1.7% | 3.6% | 4.3% |

Note: All data are for 2008, adjusted to 2014 dollars.

Source: Last years of life spending data from MCBS. Aggregate medical spending data from NHEA. Aggregated death data from National Vital Statistics Reports.

The bottom panel of Table 12 displays medical spending in the last years of life. The leftmost column refers to mean spending in the last one, two and three calendar years before death. If an individual dies in March, medical spending in the year of death will refer only to medical spending between January and March. All the data in Table 12 are for 2008, so spending in the ‘second‐to‐last’ and ‘third‐to‐last’ years is by people who go on to die in 2009 and 2010, respectively. Spending in the last calendar year of life averages $43,030, or about six times average spending for the entire population and over twice the average medical spending of the population aged 65 and over. Average medical spending in the previous year is $42,810, again about six times average medical spending per person, and spending in the third‐to‐last year is $32,860. Of the $43,030 spending in the last year of life, $21,650 is on hospital care and $9,150 is on nursing home care.

The right‐hand block of the lower panel in Table 12 presents medical spending in the last years of life as a percentage of medical spending at all ages and as a percentage of medical spending for the population aged 65 and over. We calculate these percentages by multiplying the mean spending values in this panel by the number of deaths in the top panel and dividing the resulting product by the aggregate spending values reported in the top panel. By way of example, data from the National Vital Statistics Reports indicate that 2.47 million individuals died in 2008, of whom 73 per cent were aged 65 or older. Assuming that medical spending on people who die aged 65 or over is the same as medical spending for those who die younger than 65, we can infer that aggregate medical spending on all those who died in 2008 was $43,030 × 2.47 = $106.3 billion, which constitutes 4.9 per cent of aggregate medical spending.

Medical spending for the ‘year of death’ mixes together those who died in January (and so had only one month of spending in the ‘year of death’) and those who died in December (and so had 12 months of spending), along with those dying in other months. To estimate total medical spending in the last 12 months of life, we apply the approach taken in Hoover et al. (2002) and estimate the following regression:

| (1) |

where Ei is total medical spending in the calendar year for individual i and mi is individual i’s exact month of death, where mi = 1 if the month of death is January, mi = 2 if the month of death is February, and so on. The last three rows of Table 12 present our results. Using MCBS data from 2008, we find that 16.8 per cent of all medical spending for the population aged 65 and over occurs in the last 12 months of life. Using MCBS data for 1992 to 1996, Hoover et al. (2002) found that 22 per cent of all medical spending for the population aged 65 and over occurs in the last 12 months of life. Our lower estimate appears to be the result of using more recent data. For example, if we use data from just 1996, the estimate becomes 20.9 per cent, much closer to Hoover et al.’s estimate.

Because those aged 65 and over are more likely to die, end‐of‐life spending is far more important for that age group than for the population as a whole. The population aged 65 and over accounts for only 34 per cent of all medical spending but for 73 per cent of all deaths. The percentage of medical spending at all ages going towards individuals in the last 12 months of life is only 6.7 per cent. Medical spending in the last three years of life represents 13.4 per cent of aggregate medical spending. Thus, while end‐of‐life spending is high in the US, it hardly explains why total per‐capita medical spending is so much higher in the US than in other countries. For example, Polder, Barendregt and van Oers (2006) find that 11.1 per cent of all medical expenditures in the Netherlands are made in the last year of life, a higher percentage than (our estimates) for the US.

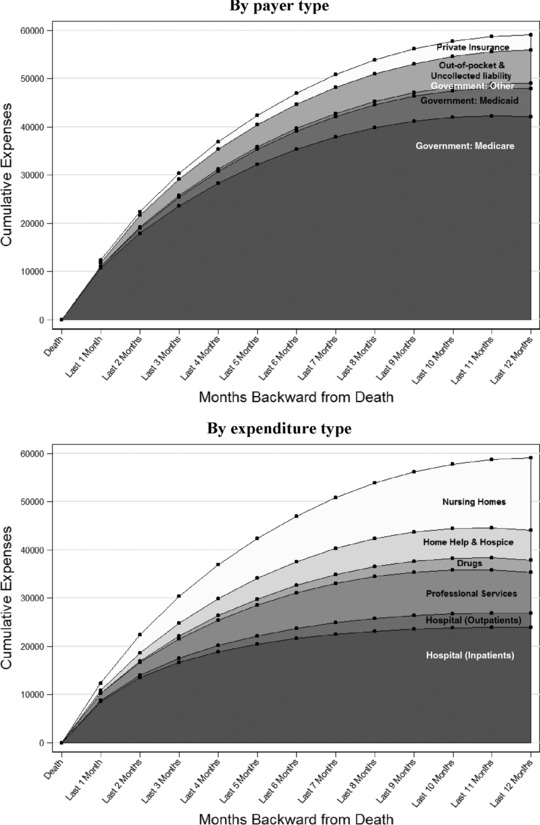

Figure 4 shows mean cumulative medical spending over the last 12 months of life as a function of the number of months from death. It decomposes medical spending into spending by payer and expenditure types. Total medical spending in the last month of life averages $12,400, the great majority of which is paid by the government, through Medicare, Medicaid and veterans’ programmes. Over the final year, total medical spending is $59,100. Of this total, $42,100, or 71 per cent, is covered by Medicare, while $5,900, or 10 per cent, is covered by Medicaid and $1,040 is covered by other government programmes. Relative to medical spending for all the elderly (see Table 4), the government picks up a larger share of medical spending amongst those near death, most notably through Medicare. Out‐of‐pocket expenses in the last year of life are $6,500, somewhat lower than found by French et al. (2006) or Marshall, McGarry and Skinner (2011). Uncollected liabilities are $380, while $3,180 is covered by private insurance. The greatest expenditure type is hospital inpatients at $24,000, or 41 per cent, followed by nursing homes at $14,990, or 25 per cent. Expenditures are $8,500 on professional services, $6,170 on home help and hospice, $2,870 on hospital outpatients and $2,560 on drugs.

Figure 4.

Spending in the last 12 months of life

VII. Conclusion

We find that medical expenses in the US more than double between ages 70 and 90 and that they are very concentrated: the top 10 per cent of all spenders are responsible for 52 per cent of medical spending in a given year. In addition, those currently experiencing either very low or very high medical expenses are likely to find themselves in the same position in the future. We also find that the poor consume more medical goods and services than the rich and have a much larger share of their expenses covered by the government. Overall, the government covers 67 per cent of the elderly's total medical expenses. Despite this, the expenses that remain after government transfers are even more concentrated among a small group of people. Thus, government health insurance, while potentially very valuable, is far from being complete. Finally, while medical expenses before death can be large, on average they constitute only a small fraction of total spending, both in the aggregate and over the life cycle. Hence, medical expenses before death do not appear to be an important driver of the high and increasing medical spending found in the US.

Supporting information

Disclaimer: Supplementary materials have been peer‐reviewed but not copyedited.

Appendix A: Supplementary Tables

Submitted June 2015.

The authors thank Elaine Kelly, Jon Skinner and participants at the ‘Medical Spending across the Developed World’ workshop at the Institute for Fiscal Studies for helpful comments, and Debra Reed‐Gillette, Joshua Volosov and the staff of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) for detailed explanations of the data. De Nardi acknowledges support from the European Research Council (ERC), grant 614328 ‘Savings and Risks’, and from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) through the Centre for Macroeconomics. French acknowledges support from a grant from the Michigan Research Retirement Center. McCauley acknowledges support from the ESRC. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research, any agency of the federal government, the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago or the Institute for Fiscal Studies.

Footnotes

Evans and Humpherys (2015), Fahle, McGarry and Skinner (this issue), Hirth et al. (this issue) and Pashchenko and Porapakkarm (this issue) focus on US data sets. Also within this issue of Fiscal Studies, Christensen, Gørtz and Kallestrup‐Lamb study Denmark, Aragón, Chalkley and Rice, Cookson et al. and Kelly, Stoye and Vera‐Hernández study England, Gastaldi‐Ménager, Geoffard and de Lagasnerie study France, Karlsson, Klein and Ziebarth study Germany, Ibuka et al. study Japan, Bakx, O'Donnell and van Doorslaer study the Netherlands, Côté‐Sergent, Échevin and Michaud study the province of Quebec in Canada, Chen and Chuang study Taiwan and Banks, Keynes and Smith analyse differences in health between the US and the UK. Related US studies include Goldman and Zissimopoulos (2003) and Hurd and Rohwedder (2009), who document out‐of‐pocket medical spending. Spillman and Lubitz (2000), Lubitz et al. (2003) and Joyce et al. (2005) use the MCBS to project total expenditures by the elderly over their remaining lives.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2015.

Hoover et al., 2002.

Emanuel and Emanuel, 1994.

Daly, 2009.

Wagstaff and van Doorslaer, 2000. More precisely, the authors review the literature on inequalities in the delivery of health care.

De Nardi, French and Jones, 2010.

Gardner and Gilleskie (2006) and De Nardi, French and Jones (2013) document many important aspects of Medicaid insurance in old age.

Kaiser Family Foundation, 2013, figure 12.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2015.

‘Other’ means ‘Other payers and programmes’, which includes Department of Defense, Department of Veterans Affairs, worksite health care, other private revenues, Indian Health Service, workers’ compensation, general assistance, maternal and child health, vocational rehabilitation, other federal programmes, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and other state and local programmes.

Adler (1998) describes the MCBS in some detail. The MCBS sourcebook series (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, multiple years) provides annual data summaries.

Citro and Michael, 1995.

Some people have zero medical spending, and so the log of their medical spending is undefined. To address this problem, we bottom‐code the medical spending data whenever we take logs. We treat all values of medical spending that are less than 10 per cent of the mean of medical spending as equal to 10 per cent of the mean. So, if someone has medical spending equal to 5 per cent of the mean, we recode their medical spending as 10 per cent of the mean. We bottom‐code income in the same way as medical spending.

The authors show that, conditional on income quintile, average total income (including asset and other non‐annuitised income), out‐of‐pocket medical spending and Medicaid recipiency rates in the AHEAD data are slightly lower than their counterparts in the MCBS data. The MCBS uses administrative data to identify Medicaid recipiency, which greatly reduces under‐reporting problems. In addition, the MCBS imputes forgotten out‐of‐pocket expenses if Medicare had to pay a share of the total cost. In contrast, AHEAD uses a more detailed set of questions to measure out‐of‐pocket medical spending, including ‘unfolding brackets’, where respondents can give ranges for their spending instead of a point estimate or ‘don't know’ as in the MCBS.

Medicare statistics come from US Census Bureau (2011). Medicare Part D payments are not disaggregated by age, so we assume 84 per cent of all Part D payments are for the 65‐and‐over age group, the same percentage as for Parts A and B.

In order to construct Table 3, we made a number of adjustments to the raw counts in both the MSIS and the MCBS. Most importantly, we adjusted the MSIS to account for the fact that, being a sample of Medicare beneficiaries, the MCBS does not include those not receiving Medicare. About 98 per cent of Americans aged 65 and over receive Medicare. However, based on our analysis of 2008 MSIS data, of those on Medicaid and aged 65 and over, only 92 per cent are also receiving Medicare, and they make up 93 per cent of total Medicaid spending for the population aged 65 and over. These estimates are similar to those in Young et al. (2012). Thus we multiplied the Medicaid population and payments in the MSIS by 0.92 and 0.93 respectively. Medicaid MSIS statistics are located at https://www.cms.gov/Research‐Statistics‐Data‐and‐Systems/Computer‐Data‐and‐Systems/MedicaidDataSourcesGenInfo/MSIS‐Tables.html.

In Table A1 in the online appendix, we compare the distribution of Medicaid spending in the MCBS with the distribution of Medicaid spending in the MSIS administrative payment data reported by Young et al. (2012).

An alternative approach is to construct spending ratios for each individual and calculate the means of these ratios. Table A2 in the online appendix displays these ratios.

Rettenmaier, 2012.

The Gini coefficient is a measure of inequality. It is generally bounded between 0 and 1, where 0 corresponds to perfect equality and 1 corresponds to maximum inequality.

We estimate total medical spending on a full set of age dummies, with age top‐coded at 100, without adjusting for cohort effects.

Other studies include Lubitz and Riley (1993), Scitovsky (1994), Levinsky et al. (2001), Riley and Lubitz (2010) and Marshall, McGarry and Skinner (2011).

Miniño et al., 2011.

Contributor Information

Mariacristina De Nardi, Email: denardim@nber.org.

Eric French, Email: eric.french.econ@gmail.com.

John Bailey Jones, Email: jbjones@albany.edu.

Jeremy McCauley, Email: jeremymccauley@gmail.com.

References

- Adler, G. S. (1998), ‘Concept and development of the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey’, in American Statistical Association, Proceedings of the Survey Research Methods Section, pp. 153–5. [Google Scholar]

- Alemayehu, B. and Warner, K. E. (2004), ‘The lifetime distribution of health care costs’, Health Services Research, vol. 39, pp. 627–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aragón, M. J. , Chalkley, M. and Rice, N. (2016), ‘Medical spending and hospital inpatient care in England: an analysis over time’, Fiscal Studies, vol. 37, pp. 405–32 (this issue). [Google Scholar]

- Bakx, P. , O'Donnell, O. and van Doorslaer, E. (2016), ‘Spending on health care in the Netherlands: not going so Dutch’, Fiscal Studies, vol. 37, pp. 593–625 (this issue). [Google Scholar]

- Banks, J. , Keynes, S. and Smith, J. P. (2016), ‘Health, disability and mortality differences at older ages between the US and England’, Fiscal Studies, vol. 37, pp. 345–69 (this issue). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, R. A. , Kopecky, K. A. and Koreshkova, T. (2015), ‘Old, sick, alone and poor: a welfare analysis of old‐age social insurance programs’, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, mimeo.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (2015), ‘National health expenditure data’, http://www.cms.gov/Research‐Statistics‐Data‐and‐Systems/Statistics‐Trends‐and‐Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical.html, downloaded January 2015.

- Chen, S. H. and Chuang, H. (2016), ‘Recent trends in Taiwanese medical spending’, Fiscal Studies, vol. 37, pp. 653–88 (this issue). [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, B. J. , Gørtz, M. and Kallestrup‐Lamb, M. (2016), ‘Medical spending in Denmark’, Fiscal Studies, vol. 37, pp. 461–97 (this issue). [Google Scholar]

- Citro C. F. and Michael R. T. (1995), Measuring Poverty: A New Approach, Washington DC: National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cookson, R. , Propper, C. , Asaria, M. and Raine, R. (2016), ‘Socio‐economic inequalities in health care in England’, Fiscal Studies, vol. 37, pp. 371–403 (this issue). [Google Scholar]

- Côté‐Sergent, A. , Échevin, D. and Michaud, P‐C. (2016), ‘The concentration of hospital‐based medical spending: evidence from Canada’, Fiscal Studies, vol. 37, pp. 627–51 (this issue). [Google Scholar]

- Daly, M. (2009), ‘Palin stands by “death panel” claim on Health Bill’, Real Clear Politics, 13 August. [Google Scholar]

- de Meijer, C. , Koopmanschap, M. , Bago d'Uva, T. and van Doorslaer, E. (2011), ‘Determinants of long‐term care spending: age, time to death or disability?’, Journal of Health Economics, vol. 30, pp. 425–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Nardi, M. , French, E. and Jones, J. B. (2010), ‘Why do the elderly save? The role of medical expenses’, Journal of Political Economy, vol. 118, pp. 39–75. [Google Scholar]

- De Nardi, M. , French, E. and Jones, J. B. (2013), ‘Medicaid insurance in old age’, National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), Working Paper no. 19151.

- Emanuel, E. J. and Emanuel, L. L. (1994), ‘The economics of dying: the illusion of cost savings at the end of life’, New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 330, pp. 540–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, R. W. and Humpherys, J. (2015), ‘U.S. healthcare spending trends from aggregated monthly claims data’, mimeo.

- Fahle, S. , McGarry, K. and Skinner, J. (2016), ‘Out‐of‐pocket medical expenditures in the United States: evidence from the Health and Retirement Study’, Fiscal Studies, vol. 37, pp. 785–819 (this issue). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feenberg, D. and Skinner, J. (1994), ‘The risk and duration of catastrophic health care expenditures’, Review of Economics and Statistics, vol. 76, pp. 633–47. [Google Scholar]

- French, E. , De Nardi, M. , Jones, J. B. , Baker, O. and Doctor, P. (2006), ‘Right before the end: asset decumulation at the end of life’, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, Economic Perspectives, vol. 30, no. 3, pp. 2–30. [Google Scholar]

- French, E. , De Nardi, M. , Jones, J. B. , Baker, O. and Jones, J. B. (2004), ‘On the distribution and dynamics of health costs’, Journal of Applied Econometrics, vol. 19, pp. 705–21. [Google Scholar]

- French, E. , De Nardi, M. , Jones, J. B. , Baker, O. and McCauley, J. (2016), ‘The accuracy of economic measurement in the Health and Retirement Study’, mimeo. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gardner, L. and Gilleskie, D. (2006), ‘The effects of state Medicaid policies on the dynamic savings patterns of the elderly’, National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), Working Paper no. 12208.

- Gastaldi‐Ménager, C. , Geoffard, P‐Y. and de Lagasnerie, G. (2016), ‘Medical spending in France: concentration, persistence and evolution before death’, Fiscal Studies, vol. 37, pp. 499–526 (this issue). [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, D. P. and Zissimopoulos, J. M. (2003), ‘High out‐of‐pocket health care spending by the elderly’, Health Affairs, vol. 22, no. 3, pp. 194–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirth, R. A. , Calónico, S. , Gibson, T. B. , Levy, H. , Smith, J. and Das, A. (2016), ‘Long‐term health spending persistence among the privately insured’, Fiscal Studies, vol. 37, pp. 749–83 (this issue). [Google Scholar]

- Hoover, D. R. , Crystal, S. , Kumar, R. , Sambamoorthi, U. and Cantor, J. C. (2002), ‘Medical expenditures during the last year of life: findings from the 1992–1996 Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey’, Health Services Research, vol. 37, pp. 1625–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd, M. D. and Rohwedder, S. (2009), ‘The level and risk of out‐of‐pocket health care spending’, Michigan Retirement Research Center, Working Paper no. 218.

- Ibuka, Y. , Chen, S. H. , Ohtsu, Y. and Izumida, N. (2016), ‘Medical spending in Japan: an analysis using administrative data from a citizen's health insurance plan’, Fiscal Studies, vol. 37, pp. 561–92 (this issue). [Google Scholar]

- Joyce, G. F. , Keeler, E. B. , Shang, B. and Goldman, D. P. (2005), ‘The lifetime burden of chronic disease among the elderly’, Health Affairs, doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w5.r18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation (2013), Medicaid: A Primer.

- Karlsson, M. , Klein, T. J. and Ziebarth, N. R. (2016), ‘Skewed, persistent and high before death: medical spending in Germany’, Fiscal Studies, vol. 37, pp. 527–59 (this issue). [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, E. , Stoye, G. and Vera‐Hernández, M. (2016), ‘Public hospital spending in England: evidence from National Health Service administrative records’, Fiscal Studies, vol. 37, pp. 433–59 (this issue). [Google Scholar]

- Levinsky, N. G. , Yu, W. , Ash, A. , Moskowitz, M. , Gazelle, G. , Saynina, O. and Emanuel, E. J. (2001), ‘Influence of age on Medicare expenditures and medical care in the last year of life’, Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), vol. 286, pp. 1349–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubitz, J. , Cai, L. , Kramarow, E. and Lentzner, H. (2003), ‘Health, life expectancy, and health care spending among the elderly’, New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 349, pp. 1048–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubitz, J. , Cai, L. , Kramarow, E. and Riley, G. F. (1993), ‘Trends in Medicare payments in the last year of life’, New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 328, pp. 1092–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, S. , McGarry, K. and Skinner, J. S. (2011), ‘The risk of out‐of‐pocket health care expenditures at the end of life’, in Wise D. A. (ed.), Explorations in the Economics of Aging, Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meara, E. , White, C. and Cutler, D. M. (2004), ‘Trends in medical spending by age, 1963–2000’, Health Affairs, vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 176–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miniño, A. M. , Murphy, S. L. , Xu, J. and Kochanek, K. D. (2011), ‘Deaths: final data for 2008’, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Vital Statistics Reports, vol. 59, no. 10, pp. 1–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pashchenko, S. and Porapakkarm, P. (2016), ‘Medical spending in the US: facts from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey data set’, Fiscal Studies, vol. 37, pp. 689–716 (this issue). [Google Scholar]

- Polder, J. J. , Barendregt, J. J. and van Oers, H. (2006), ‘Health care costs in the last year of life: the Dutch experience’, Social Science & Medicine, vol. 63, pp. 1720–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rettenmaier, A. J. (2012), ‘The distribution of lifetime Medicare benefits, taxes and premiums: evidence from individual level data’, Journal of Public Economics, vol. 96, pp. 760–72. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, G. F. and Lubitz, J. D. (2010), ‘Long‐term trends in Medicare payments in the last year of life’, Health Services Research, vol. 45, pp. 565–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scitovsky, A. A. (1984), ‘“The high cost of dying”: what do the data show?’, Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly: Health and Society, vol. 62, pp. 591–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scitovsky, A. A. (1994), ‘“The high cost of dying” revisited’, Milbank Quarterly, vol. 72, pp. 561–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seshamani, M. and Gray, A. M. (2004), ‘A longitudinal study of the effects of age and time to death on hospital costs’, Journal of Health Economics, vol. 23, pp. 217–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillman, B. C. and Lubitz, J. (2000), ‘The effect of longevity on spending for acute and long‐term care’, New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 342, pp. 1409–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau (2011), ‘Health and nutrition’, in Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2012, Washington DC. [Google Scholar]

- Wagstaff, A. and van Doorslaer, E. (2000), ‘Equity in health care finance and delivery’, in Culyer A. J. and Newhouse J. P. (eds), Handbook of Health Economics, Volume 1B, Amsterdam: North‐Holland. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z. , Norton, E. C. and Stearns, S. C. (2003), ‘Longevity and health care expenditures: the real reasons older people spend more’, Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, vol. 58, pp. S2–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young, K. , Garfield, R. , Musumeci, M. B. , Clemans‐Cope, L. and Lawton, E. (2012), ‘Medicaid's role for dual eligible beneficiaries’, Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Issue Brief, https://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/7846‐03.pdf.

- Zweifel, P. , Felder, S. and Meiers, M. (1999), ‘Ageing of population and health care expenditure: a red herring?’, Health Economics, vol. 8, pp. 485–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Disclaimer: Supplementary materials have been peer‐reviewed but not copyedited.

Appendix A: Supplementary Tables