Abstract

Background

Although women represent an increasing proportion of those presenting with abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) rupture, the current prevalence of AAA in women is unknown. The contemporary population prevalence of screen‐detected AAA in women was investigated by both age and smoking status.

Methods

A systematic review was undertaken of studies screening for AAA, including over 1000 women, aged at least 60 years, done since the year 2000. Studies were identified by searching MEDLINE, Embase and CENTRAL databases until 13 January 2016. Study quality was assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa scoring system.

Results

Eight studies were identified, including only three based on population registers. The largest studies were based on self‐purchase of screening. Altogether 1 537 633 women were screened. Overall AAA prevalence rates were very heterogeneous, ranging from 0·37 to 1·53 per cent: pooled prevalence 0·74 (95 per cent c.i. 0·53 to 1·03) per cent. The pooled prevalence increased with both age (more than 1 per cent for women aged over 70 years) and smoking (more than 1 per cent for ever smokers and over 2 per cent in current smokers).

Conclusion

The current population prevalence of screen‐detected AAA in older women is subject to wide demographic variation. However, in ever smokers and those over 70 years of age, the prevalence is over 1 per cent.

Short abstract

Significant in older women who smoke

Introduction

Previously abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) has been considered a male‐dominated disorder, with four to six times more men than women receiving both elective and emergency AAA repair, and epidemiological studies showing that the prevalence of AAA was three to six times higher in men than in women1, 2, 3. Women tend to develop AAA later in life than men4, 5. Population screening for AAA in men has been introduced in several countries, to reduce mortality from ruptured AAA6. However, today almost one‐third of the patients presenting to hospital with ruptured AAA are women and their mortality is very high, so that women are contributing an increasing proportion of AAA deaths7, 8. Therefore, it is questionable whether women are being offered appropriate diagnosis and adequate management of their AAA9.

Smoking is the strongest risk factor for AAA, the association being much stronger than that between smoking and other forms of cardiovascular disease10. Historically, women took up smoking in large numbers some 15–20 years after men, and several studies11, 12, 13 suggest that today the prevalence of smoking may be higher in women than in men. There has been a steady decline in the prevalence of smoking over the past 25–30 years, most notably among men, which has been linked to a declining prevalence of screen‐detected AAA in men, from 4–5 per cent in the 1990s to about 1–2 per cent today14, 15. Other factors, including the more widespread use of diagnostic imaging leading to an increasing incidental detection of AAA, could also have contributed to the declining prevalence of screen‐detected AAA in men. There are far fewer data available for women. This study is a systematic review of contemporary (2000 or later) AAA screening studies in women, to assess the population prevalence, and determine how this may vary with age and smoking status.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted according to the PRISMA guidelines16, and registered in May 2015 in the PROSPERO database (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/; registration number CRD42015020444). The review protocol was reviewed externally (F. Lederle, Veterans Administration Hospital, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA). The aim was systematically to review published and unpublished data of the current (since 2000) prevalence of AAA in women, detected by either ultrasonography or CT (aortic diameter 3·0 cm or greater).

MEDLINE, Embase and CENTRAL databases were searched, using a combination of controlled vocabulary (medical subject heading (MeSH) or Emtree®) terms and free‐text terms in ProQuest Dialog™, and limiting the search to data published since 2000. The search was restricted to major European languages, and used the following terms: abdominal aortic aneurysm, women/gender/sex/women's health/sex difference, genetic predisposition, prevalence/incidence/occurrence/frequency, screening, population/population‐based. The final search date was 13 January 2016.

Clinicaltrials.gov (http://clinicaltrials.gov), Current Controlled Trials (http://www.controlled‐trials.com/) and the National Research Register (UK) were also searched for details of ongoing or unpublished trials. This search was complemented by scanning reference lists of relevant articles, and manual searches of Endovascular Today and vascular surgery conference proceedings.

Study selection

The inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Table 1. The initial rejection or inclusion was based on the study title; review articles were retained for examination of their references.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Screening date year 2000 onwards | Review articles |

| Women ≥ 60 years of age | Editorials |

| All ethnic groups | Letters |

| Population described clearly | Case reports |

| Screening of ≥ 1000 women | Studies of people with known cardiovascular disease |

| For studies reporting duplicated data, the most recent or most comprehensive publication to be included | |

| Ultrasonography or CT for aortic diameter measurement |

Full‐text versions of the selected shortlist of documents were obtained. Two reviewers assessed them individually to make sure they adhered to the initial eligibility criteria and then selected studies that met the inclusion criteria. Differences of opinion were resolved by discussion.

Data extraction and quality scoring

A data extraction form, which identified demographic and technical details, and potential biases, in the selected studies, was designed by the reviewers and approved by the full study team. A summary checklist was completed for each study. For four publications, study authors were contacted to request additional information to enable completion of the checklist. Three authors/studies provided the requested data. Quality scoring was undertaken using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale for cross‐sectional studies17. Criteria for quality assessment are detailed in the protocol (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPEROFILES/20444_PROTOCOL_20160426.pdf).

The following data were extracted independently by the two reviewers: study design, screening setting (including number of centres) and country, AAA screening start and end dates, screening method, AAA definition, population description of women (including ethnicity, age range, smoking and diabetes), exclusion criteria (particularly when the study excluded non‐screen‐detected/known AAA or previous AAA repairs), number of women invited to be screened, number of women who accepted screening, number of women with AAA (including AAA detection by age and smoking status), and authors' reported limitations of the study.

Data synthesis and analysis

An estimate of the prevalence was made from each study, calculated as the number of women with AAA divided by the number of women who were screened successfully. A 95 per cent confidence interval (c.i.) for the prevalence in each study was calculated using the score confidence interval18, 19. Three studies20, 21, 22 included women younger than 60 years of age in their screening. As the present review excludes younger women, only those aged 60 years and above from these studies were included. A random‐effects meta‐analysis was performed on the logit probability scale (with standard errors transformed using the δ method) using the method of DerSimonian and Laird23. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I 2 statistic24. Further exploration of between‐study heterogeneity was investigated by meta‐regression. Results are presented as forest plots.

Results

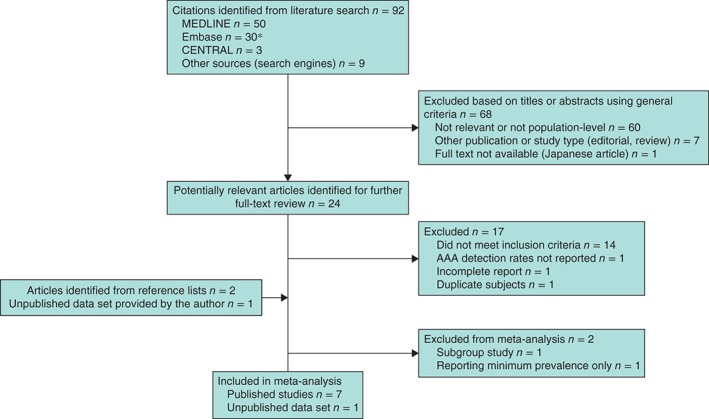

A total of 92 unique articles were identified, of which 24 (26 per cent) were considered potentially relevant and assessed in detail (Fig. 1). Six papers based on six studies met the inclusion criteria20, 21, 25, 26, 27, 28 and a seventh study22 reported on AAA defined as diameter of 3·5 cm or more, but data for women with aortic diameter of 3·0 cm or over were obtained from the corresponding author. All these studies used ultrasonography for screening. Correspondence with the authors provided further details of several studies21, 25, 26 and one author25 provided an eighth unpublished study using ultrasonography for screening. These eight studies were included in the meta‐analysis. One study29 reported on a subgroup of a larger study, and was retained for assessment of prevalence by smoking status only. One further medium‐sized study30 reported on physician‐initiated screening (with both ultrasonography and CT) in a population, but without defining either the specific criteria for screening or AAA by a minimum aortic diameter, and hence provides only a minimum estimate of prevalence. All of the studies excluded women with known AAA from screening.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of included studies. *Five duplicates between MEDLINE and Embase removed. AAA, abdominal aortic aneurysm

Of the 17 studies that were excluded after reviewing the full text, two did not meet the inclusion criteria as they had screened fewer than 1000 women: 795 women31 and 796 women32. Three large studies were excluded: one33 consisted of a selected population (including 14 834 Chinese women with hypertension) and the other two34, 35 had been carried out in 1992 and between 1992 and 1997 respectively. A recent French study36 provided insufficient information.

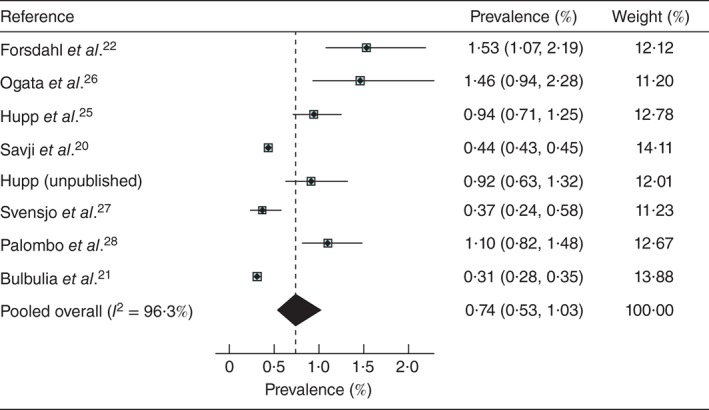

The characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 2. Two studies20, 21 of very large cohorts were identified (about 1·4 and 0·9 million women aged at least 60 years respectively), mainly self‐referred for self‐purchased Life Line screening, from the USA and Great Britain and Ireland. The US Life Line screening data included a minority of subjects (7·0 per cent) with at least one cardiovascular risk factor, put forward for sponsored Life Line screening; this minority was reported on separately by Derubertis and colleagues29. These latter data were used to assess the effect of smoking on AAA prevalence, as this was not reported in the overall USA Life Line cohort20. Smaller studies offering free screening based on population registers were from Sweden27, Norway22 and Italy28, but only two of these were of very high quality, and in total this type of study contributed only 11 003 women. There were two further published studies25, 26 and one unpublished study offering, by advertisement, sponsored free screening in the USA. This gave an overall total of 1 537 633 women screened in eight separate studies, with a pooled prevalence of AAA of 0·74 (95 per cent c.i. 0·53 to 1·03) per cent in women aged at least 60 years, but with considerable heterogeneity (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies, ordered by date of screening

| Reference | Selection for screening | Screening dates | Country | No. of women screened (% attendance) |

Age range (years) |

Never smoked (current smokers) (%) | N‐O score* | No. of AAAs (% prevalence) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forsdahl et al. 22 | Population‐based, free | 2001 | Norway | 1956 (85†) | 61 to ≥ 80 | 35 (25) | 9 | 30 (1·53) |

| Ogata et al. 26 | Self‐referred, free | 2001–2004 | USA | 1298 (n.a.) | 60–89 | n.a. (9·2) | 5 | 19 (1·46) |

| Hupp et al. 25 | Self‐referred, free | 2000–2006 | USA | 4982 (n.a.) | 60–89 | n.a. | 7 | 47 (0·94) |

| Savji et al. 20, ‡ | Mainly self‐referred, self‐purchased | 2003–2008 | USA | 1 428 316 (n.a.) | 61–100 | n.a. | 6 | 6229 (0·44) |

| Hupp (unpublished) | Self‐referred, free | 2006–2008 | USA | 3060 (n.a.) | 66–105 | 22 (n.a.) | 7 | 28 (0·92) |

| Svensjo et al. 27 | Population‐based, free | 2007–2009 | Sweden | 5140 (74) | 70 | 56 (10) | 9 | 19 (0·37) |

| Palombo et al. 28 | Population‐based, free | 2007–2009 | Italy | 3907 (48) | ≥ 65 | n.a. | 7 | 43 (1·10) |

| Bulbulia et al. 21 | Self‐referred, self‐purchased | 2008–2012 | UK, Ireland | 88 974 (n.a.) | 60 to ≥ 80 | n.a. | 6 | 278 (0·31) |

| Jahangir et al. 30, § | Physician‐initiated, reimbursed | 2002–2009 | USA | 11 815 (n.a.) | ≥ 65 | 42 (21) | 5 | 123 (1·04) |

Newcastle–Ottawa scale (N‐O), used to assess study quality; highest scores represent the best quality studies (http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp).

Similar numbers of men and women screened; overall uptake 85 per cent.

Does not report aneurysm size and smoking; used for prevalence only owing to the very large population of women and supplemented by data from Derubertis and colleagues29, who also used the same Life Line screening, but provided data on a subgroup of 10 012 women, mean age 69 years, with at least one cardiovascular risk factor, screened between 2004 and 2006.

Physician‐initiated screening study reporting only minimum prevalence; not included in data synthesis, but outline details are provided for comparison with a group of lower socioeconomic status. AAA, abdominal aortic aneurysm; n.a., not available.

Figure 2.

Pooled prevalence of abdominal aortic aneurysm in women aged at least 60 years: eight studies with screening performed between 2001 and 2012. Values in parentheses are 95 per cent confidence intervals

The lowest prevalence (0·31 per cent) was observed in the large UK and Ireland Life Line study21 of self‐referred individuals paying for screening. Otherwise the overall prevalence of AAA ranged from 0·37 per cent in Sweden to 1·53 per cent in Norway (both studies based on population registers). The Life Line screening of predominantly self‐referred women purchasing screening yielded similar low AAA prevalence in the USA (0·44 per cent) and in Great Britain and Ireland (0·31 per cent). The study of a large predominantly uninsured and ethnically diverse US population aged 65 years and over, in which almost half of the women smoked, reported a minimum prevalence of 1·04 per cent30 (Table 2).

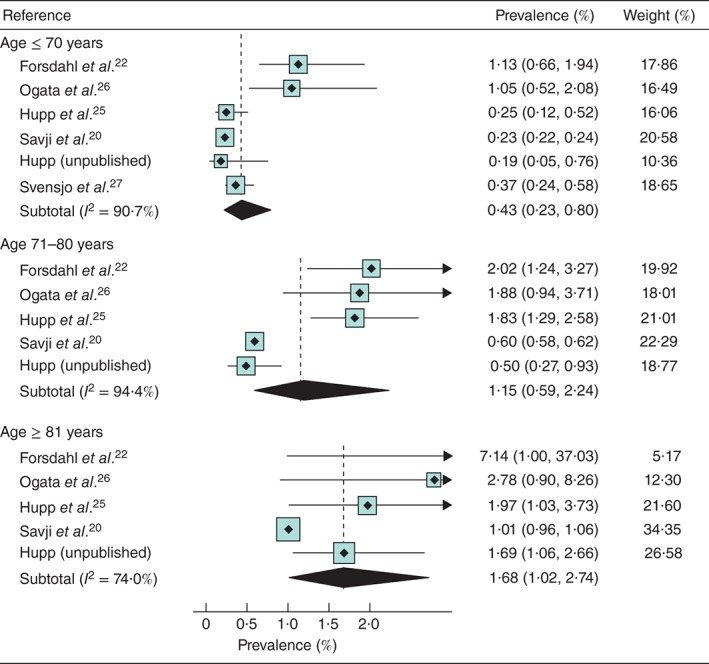

The pooled prevalence of AAA increased rapidly with age: 0·43 per cent at 61–70 years, 1·15 per cent in those 71–80 years and 1·68 per cent in those aged 81 years or more (Fig. 3). However, there was considerable heterogeneity even for these pooled estimates (I 2 = 74–94 per cent), and in every age band the prevalence was lowest in the self‐referred cohorts and highest in the Norwegian population register‐based cohort. However, when relative risks were assessed, there was more consistency between studies (I 2 = 0–49 per cent) than seen with the absolute risks. Compared with those aged 70 years or less, the prevalence was 2·7 (95 per cent c.i. 1·8 to 4·2) times higher in the 71–80‐years age group and 4·3 (4·0 to 4·7) times higher among women aged 81 years or more.

Figure 3.

Prevalence of abdominal aortic aneurysm in women aged at least 60 years by 10‐year age groups. All women were aged 70 years in Svensjo et al. 27. Values in parentheses are 95 per cent confidence intervals

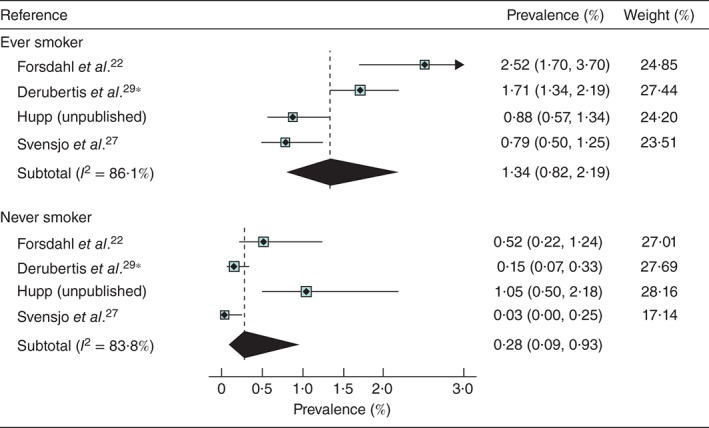

Only five studies reported on prevalence by smoking status (Table 2), although the recording of smoking status was not uniform. Hupp (unpublished) recorded those who remembered having smoked over 100 cigarettes in their lifetime, which is the definition used by the US Preventive Services Task Force37. The pooled prevalence was lower for never smokers (0·28 per cent) than for ever smokers (1·34 per cent) (Fig. 4). The study by Jahangir and colleagues30 provides support for this effect as the association between AAA and former smoking had a hazard ratio of 3·4, rising to 9·2 in current smokers. Three studies reported the prevalence in current smokers: 2·08 per cent27, 4·63 per cent22 and 2·82 per cent26. Two of the smaller studies27, 29 reported similar prevalence for those with, and without diabetes.

Figure 4.

Prevalence of abdominal aortic aneurysm in women aged at least 60 years by smoking status. *Derubertis and colleagues29 reported data on smoking status in a subgroup of patients from the study by Savji et al.; the analysis included 10 012 women, mean age 69 years, with at least one cardiovascular risk factor screened between 2004 and 2006. Values in parentheses are 95 per cent confidence intervals

Discussion

Data on the population prevalence of AAA in women are sparse and this systematic review identified only a handful of studies conducted since 2000, with a pooled prevalence of 0·74 (95 per cent c.i. 0·53 to 1·03) per cent in women aged 60 years and over. This date limitation was introduced because of the observed twofold reduction in prevalence of screen‐detected AAA in men between 1990 and now15. Of the identified studies, only three invited women for free screening based on population registers; the remainder recruited by advertisement, with self‐referral screening being either sponsored or paid for by the woman screened. This diversity in design implies that the populations screened were of diverse demographic characteristics, particularly with respect to socioeconomic status, which is likely to underlie part of the significant heterogeneity between studies. For this reason, the physician‐referred screening in a largely uninsured southern US population with high ethnic diversity is included as a comparator30. The contemporary pooled prevalence of AAA in women aged at least 60 years, reported here, appears to be lower than that for earlier studies. For instance, in the population register‐based Chichester (UK) screening trial2, the prevalence in 65–80‐year‐old women in 1988–1990 was 1·3 per cent (but 1·7 per cent in those aged over 70 years).

This study also reports an increasing prevalence of AAA with age and smoking, particularly for current smokers where the prevalence appears to be over 2 per cent. Of all the cardiovascular disorders, AAA has the strongest association with smoking, particularly current smoking10. The decline in smoking in those aged over 65 years has been slower in women than in men8, 13. The proportion of current smokers varied in the different studies included in this review, but was highest in Norway19, where the prevalence of AAA was highest. Some of the difference in overall prevalence between the neighbouring countries of Norway19 and Sweden14 might be explained by differences in smoking prevalence: 25 and 10 per cent respectively. The high prevalence of AAA in women smokers was a notable feature of the Jahangir study30, suggesting that smoking may have a greater relative impact on prevalence in women than in men. There was insufficient information in the included studies to assess the impact of other risk factors. Other contributions to heterogeneity might come from the variable used for ultrasound diameter measurements: anterior–posterior or transverse, based on inner‐to‐inner wall, outer‐to‐outer wall or leading edge‐to‐leading edge. Only one study27 was specific about the measurement method reported.

All the data for this systematic review are based on the definition of an AAA having a maximum infrarenal aortic diameter of at least 3 cm on ultrasonography. This definition has been derived for men, where 3·0 cm represents an approximately 50 per cent increase in normal infrarenal aortic diameter. In men the median diameter of those aged 65 years or more is 2·02 cm, whereas in women aged at least 65 years the median infrarenal aortic diameter is only 1·75 cm38. This begs the question whether the diameter threshold for definition of an AAA should be lower in women, perhaps 2·6 cm. If this were the case, the screen‐detected prevalence of AAA in women would be much higher. For instance, with this lower diameter threshold, the prevalence of AAA in 70‐year‐old Swedish women would more than double27. Whether an aortic diameter between 2·6 and 2·9 cm in women represents clinically significant disease is unknown, and only studies with long‐term follow‐up of this group will determine whether there is any clinical benefit in refining the definition of an AAA for women.

The data for the contemporary prevalence of AAA in women should be considered in the context of the ongoing debate about whether AAAs in women are diagnosed and treated adequately. If AAA screening in 65‐year‐old men is cost‐effective down to a prevalence rate as low as 0·35 per cent39, AAA screening also may be cost‐effective in 70‐year‐old women, especially as the AAA rupture rate in women is about four times that in men for a given AAA diameter40. Indeed, a modelling study from Sweden41 has already suggested that AAA screening for older women would be cost‐effective, based on an AAA prevalence of 1·1 per cent in 65‐year‐old women.

Present guidelines for AAA screening in women are only that it is not recommended for older women who have never smoked37. This contemporary review, showing a pooled prevalence of 0·74 per cent in women aged at least 60 years, rising to over 1·0 per cent in ever smokers and those aged 70 years or older, might stimulate the debate about offering targeted AAA screening to older women.

Collaborators

SWAN (Screening Women for Aortic aNeurysm) Collaborative Group members: S. G. Thompson (Chief Investigator), M. J. Sweeting, E. Jones (University of Cambridge, Cambridge); J. T. Powell, P. Ulug (Imperial College London, London); M. J. Bown (University of Leicester, Leicester); M. J. Glover (Brunel University, Uxbridge).

Acknowledgements

Particular thanks go to all authors who provided additional data to complete this review and other members of the SWAN collaborative group. This project was funded by the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Appraisal (HTA) programme (project number 14/179/01). The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the HTA programme, NIHR, National Health Service or the Department of Health.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

SWAN Collaborative Group:

S. G. Thompson, M. J. Sweeting, E. Jones, J. T. Powell, P. Ulug, M. J. Bown, and M. J. Glover

References

- 1. Pleumeekers HJ, Hoes AW, van der Does E, van Urk H, Hofman A, de Jong PT et al Aneurysms of the abdominal aorta in older adults. The Rotterdam Study. Am J Epidemiol 1995; 142: 1291–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Scott RA, Bridgewater SG, Ashton HA. Randomized clinical trial of screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm in women. Br J Surg 2002; 89: 283–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Norman PE, Powell JT. Abdominal aortic aneurysm: the prognosis in women is worse than in men. Circulation 2007; 115: 2865–2869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bengtsson H, Bergqvist D, Sternby NH. Increasing prevalence of abdominal aortic aneurysms. A necropsy study. Eur J Surg 1992; 158: 19–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Katz DJ, Stanley JC, Zelenock GB. Gender differences in abdominal aortic aneurysm prevalence, treatment, and outcome. J Vasc Surg 1997; 25: 561–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. International AAA Screening Group , Björck M, Bown MJ, Choke E, Earnshaw J, Florenes T et al International update on screening for abdominal aortic aneurysms: issues and opportunities. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2015; 49: 113–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. IMPROVE Trial Investigators . Endovascular or open repair strategy for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm: 30 day outcomes from IMPROVE randomised trial. BMJ 2014; 348: f7661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Anjum A, von Allmen R, Greenhalgh R, Powell JT. Explaining the decrease in mortality from abdominal aortic aneurysm rupture. Br J Surg 2012; 99: 637–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Starr JE, Halpern V. Abdominal aortic aneurysms in women. J Vasc Surg 2013; 57(Suppl): 3S–10S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pujades‐Rodriguez M, George J, Shah AD, Rapsomaniki E, Denaxas S, West R et al Heterogeneous associations between smoking and a wide range of initial presentations of cardiovascular disease in 1 937 360 people in England: lifetime risks and implications for risk prediction. Int J Epidemiol 2015; 44: 129–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Amos A. Women and smoking. Br Med Bull 1996; 52: 74–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Office for National Statistics . Adult Smoking Habits in Great Britain 2014. http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171778_433639.pdf [accessed 23 February 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Svensjö S, Björck M, Wanhainen A. Update on screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: a topical review. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2014; 48: 659–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sidloff D, Stather P, Dattani N, Bown M, Thompson J, Sayers R et al Aneurysm global epidemiology study: public health measures can further reduce abdominal aortic aneurysm mortality. Circulation 2014; 129: 747–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. National Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Screening Programme . 2013/14 AAA Screening Data. http://aaa.screening.nhs.uk/2013‐14datareports [accessed 5 June 2015]. [Google Scholar]

- 16.PRISMA: Transparent Reporting of Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses. http://www.prisma‐statement.org [accessed 20 August 2015].

- 17. Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M et al The Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta‐Analyses. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp [accessed 18 December 2015]. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nyaga VN, Arbyn M, Aerts M. Metaprop: a Stata command to perform meta‐analysis of binomial data. Arch Public Health 2014; 72: 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wilson EB. Probable inference, the law of succession, and statistical inference. J Am Stat Assoc 1927; 22: 209–212. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Savji N, Rockman CB, Skolnick AH, Guo Y, Adelman MA, Riles T et al Association between advanced age and vascular disease in different arterial territories: a population database of over 3·6 million subjects. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 61: 1736–1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bulbulia R, Chabok, M , Aslam, M , Lewington S, Sherliker P, Manganaro A et al The prevalence of abdominal aortic aneurysm, carotid stenosis, peripheral arterial disease and atrial fibrillation among 280 000 screened British and Irish Adults. Vasc Med 2013; 18: 155. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Forsdahl SH, Singh K, Solberg S, Jacobsen BK. Risk factors for abdominal aortic aneurysms: a 7‐year prospective study: the Tromso Study, 1994–2001. Circulation 2009; 119: 2202–2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta‐analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986; 7: 177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Higgins JP Thompson TS, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta‐analyses. BMJ 2003; 327: 557–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hupp JA, Martin JD, Hansen LO. Results of a single center vascular screening and education program. J Vasc Surg 2007; 46: 182–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ogata T, Arrington S, Davis PM Jr, Sam AD II, Hollier LH, Tromp G et al Community‐based, nonprofit organization‐sponsored ultrasonography screening program for abdominal aortic aneurysms is effective at identifying occult aneurysms. Ann Vasc Surg 2006; 20: 312–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Svensjo S, Bjorck M, Wanhainen A. Current prevalence of abdominal aortic aneurysm in 70‐year‐old women. Br J Surg 2013; 100: 367–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Palombo D, Lucertini G, Pane B, Mazzei R, Spinella G, Brasesco PC. District‐based abdominal aortic aneurysm screening in population aged 65 years and older. J Cardiovasc Surg 2010; 51: 777–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Derubertis BG, Trocciola SM, Ryer EJ, Pieracci FM, McKinsey JF, Faries PL et al Abdominal aortic aneurysm in women: prevalence, risk factors, and implications for screening. J Vasc Surg 2007; 46: 630–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jahangir E, Lipworth L, Edwards TL, Kabagambe EK, Mumma MT, Mensah GA et al Smoking, sex, risk factors and abdominal aortic aneurysms: a prospective study of 18 782 persons aged above 65 years in the Southern Community Cohort Study. J Epidemiol Comm Health 2015; 69: 481–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Puech‐Leão P, Molnar LJ, Oliveira IR, Cerri GG. Prevalence of abdominal aortic aneurysms – a screening program in São Paulo, Brazil. São Paulo Med J 2004; 122: 158–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schermerhorn M, Zwolak R, Velazquez O, Makaroun M, Fairman R, Cronenwett J. Ultrasound screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm in medicare beneficiaries. Ann Vasc Surg 2008; 22: 16–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Guo W, Zhang T. Abdominal aortic aneurysm prevalence in China. Endovascular Today 2014: 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ishikawa S, Takahashi T, Sato Y, Suzuki M, Ohki S, Oshima K et al Screening cost for abdominal aortic aneurysms: Japan‐based estimates. Surg Today 2004; 34: 828–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lederle FA, Johnson GR, Wilson SE, Aneurysm D; Group Management Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study. Abdominal aortic aneurysm in women. J Vasc Surg 2001; 34: 122–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Laroche JP, Becker F, Baud JM, Miserey G, Jaussent A, Picot MC et al [Ultrasound screening of abdominal aortic aneurysm: lessons from Vesale 2013.] J Mal Vasc 2015; 40: 340–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. LeFevre ML; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2014; 161: 281–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rogers IS, Massaro JM, Truong QA, Mahabadi AA, Kriegel MF, Fox CS et al Distribution, determinants, and normal reference values of thoracic and abdominal aortic diameters by computed tomography (from the Framingham Heart Study). Am J Cardiol 2013; 111: 1510–1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Glover MJ, Kim LG, Sweeting MJ, Thompson SG, Buxton MJ. Cost‐effectiveness of the National Health Service Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Screening Programme in England. Br J Surg 2014; 101: 976–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sweeting MJ, Thompson SG, Brown LC, Powell JT; RESCAN collaborators . Meta‐analysis of individual patient data to examine factors affecting growth and rupture of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. Br J Surg 2012; 99: 655–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wanhainen A, Lundkvist J, Bergqvist D, Björck M. Cost‐effectiveness of screening women for abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg 2006; 43: 908–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]