It is well appreciated that proteins are involved in all processes of life ranging from cell proliferation to cell survival and death. With such a wide spectrum of activities, which in many cases have opposing results, proteins must be tightly regulated to ensure the right outcome at the right time. Indeed, proteins are regulated at various levels prior to, during, and after their translation. The latter type of regulation, known as posttranslational modification (PTM), occurs via modifiers that covalently bind the target protein. These modifiers comprise small molecules, as in the case of phosphorylation, acetylation, and methylation, and also small polypeptides, such as ubiquitin (Ub) and ubiquitin-like proteins (UBLs). Ub is a highly conserved 76-residue protein, which is covalently linked to target proteins mainly via an isopeptide bond between its C-terminal glycine (Gly) and a lysine (Lys) side chain on a target protein, a process known as ubiquitination (1). Ubiquitination refers to a family of modifications, since proteins can be modified with monoubiquitin (Ub) on 1 or several lysines or with Ub chains (2, 3). With such a wide range of modifications, it is not surprising that ubiquitination plays a role in many different processes including protein degradation, activation, and localization. Accordingly, improper regulation of ubiquitination has been observed in many human diseases including cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease (4). Therefore, understanding the molecular mechanisms of ubiquitination is of high interest not only for basic research but also for the development of novel therapeutic applications.

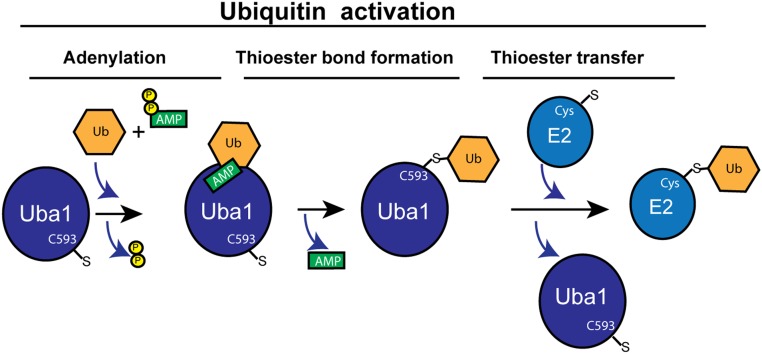

Before its conjugation to a target protein, Ub or UBL undergoes an activation process mediated by an activating enzyme (E1) (5). While each UBL has its own E1, activation of Ub occurs mainly via the E1, Uba1. Activation of both Ub and UBL comprises 3 steps: 1) adenylation of the Ub/UBL C-terminal Gly (Ub/UBL-AMP), 2) thioester bond formation with the E1 active-site cysteine (Cys) (E1∼Ub/UBL), and 3) thioester bond transfer to the E2 active site (E2∼Ub/UBL) (Fig. 1). Therefore, the transfer of Ub to the E2 marks the end of the activation process and the competency of Ub to enter the next phase of conjugation. In this phase, which is mediated by E3 ligases, Ub is transferred from the E2 to the final destination—mainly a lysine residue of a target protein. Therefore, while the steps required for Ub activation are established, the structural basis that enables the E1 to execute these steps is yet not well understood. In PNAS, Hann et al. (6) provide the structural basis for adenylation and thioester bond formation in the Ub E1.

Fig. 1.

The 3 steps in ubiquitin activation. Ub adenylation occurs when the E1 is in the open conformation and the active-site C593 is separated from the Ub-AMP. In the second step, the E1 undergoes conformational changes to the closed conformation. This juxtaposes C593 to the Ub-AMP, enabling thioester bond formation. In the last step the E1 returns to the open conformation that allows thioester transfer to the E2, generating E2∼Ub.

The Ub E1 is a member of the canonical E1 family that comprises the E1s for the UBLs SUMO, NEDD8, FAT10, and ISG15. Structural insights into canonical E1s were gained from the crystal structures of the E1s of NEDD8, SUMO, and Ub (7–10). These structures include apo E1s or E1s bound to ATP/Mg and/or with E2s. As expected based on their similar function, all canonical E1 structures share common features including an adenylation domain, which is responsible for Ub/UBL adenylation, a Cys domain comprising the active site cysteine that forms the thioester bond with the Ub/UBL C terminus, and a Ub-fold domain (UFD) required for the interaction with the E2. An additional and perhaps more interesting common feature is the large distance between the active-site Cys and the position of the Ub/UBL C-terminal Gly at the adenylation domain. Therefore, these structures capture the open conformation of E1s.

While the above structures significantly advanced our structural understanding of canonical E1s, they all left open the question of how the active-site Cys reaches the adenylated Ub/UBL to facilitate thioester bond formation. The first answer to this question came from the work of Olsen et al. (11) in which they captured the SUMO E1 in a closed conformation. Using an elegant chemical approach, they applied an electrophilic trap bound to SUMO (SUMO-AVSN) that upon E1 binding locked the reaction in the tetrahedral intermediate (12). In this structure the Cys domain underwent an ∼130° rotation compared with its position in the open conformation and as a result juxtaposed the active-site Cys and the SUMO-AVSN. In parallel, remodeling of several structural features, including the helix comprising the active-site Cys as well as the crossover and reentry loops that connect between the adenylation domain and the Cys domain, yielded a productive closed conformation that enabled thioester bond formation. To date this is the only structure of an E1 in a closed conformation. Interestingly, although the Ub E1 shares common features with SUMO E1, the Cys domain of Ub E1 is larger than the Cys domain of SUMO E1 and comprises the first and second catalytic cysteine half-domains (FCCH and SCCH, respectively), while the SCCH domain contains the active-site Cys residue. Therefore, structural insights into how the closed conformation of Ub E1 is achieved and whether it keeps the structural remodeling observed in the SUMO E1 are not yet clear.

In PNAS Hann et al. (6) provide 2 crystal structures of Ub E1, each at a different step in the activation process, which together fill the gap in our structural understanding of the Ub E1 catalytic cycle. To capture the activation process at the adenylation step, before pyrophosphate (PPi) release, Hann et al. (6) crystalized the E1 in complex with Ub-AMSN, which mimics the adenylate intermediate, and with PPi. As expected, the structure is in the open conformation with an overall architecture that is similar to the structure of Ub E1 bound to Ub/ATP/Mg. Interestingly, the orientation of the PPi is no longer the same as the β γ phosphates of the ATP in the ATP-bound structure. Specifically, the bridging oxygen of the PPi moves toward the side chain of N471, thereby altering the hydrogen-bond network that the PPi generates with the adenylation domain. In parallel, variations in the distances between Ub Gly76 and the α-phosphorous and β-phosphorous atoms and their equivalents in the Ub-AMSN structure were also observed. Taken together, these structural differences further advance our structural understanding and fit the proposed mechanism of an in-line attack on the ATP α-phosphate by Ub Gly76 carboxylate (7, 10, 13, 14).

The next step in the activation process, after Ub adenylation, is the attacking of the E1 active-site Cys and the formation of a thioester bond with Ub C-terminal Gly. To capture this step, Hann et al. (6) exploited their previous approach of an electrophilic trap and generated UB-AVSN. With this in hand, they crystalized the Ub E1 bound to UB-AVSN. As expected, the structure shows the active-site Cys linked to the UB-AVSN, thereby capturing the closed conformation. To achieve this conformation the SCCH domain undergoes a 124° rotation compared with its position in the open conformation. Moreover, both the N-terminal helices and helix g7 melt to leave room for the active-site Cys that is no longer part of a helix but instead occupies the position of the above helices in the open conformation. In parallel, these conformational changes disorder the ATP binding site, thereby making the closed conformation less able to bind ATP. Additional changes take place in the paths of the crossover and reentry loops which change by 115° and 59°, respectively, compared with their position in the open conformation structure. These structural changes also lead to a short 2-stranded β-sheet between the crossover and reentry loops that probably plays a role in holding the active-site Cys in the right position for thioester bond formation.

While the above conformational changes as well as the rotation of the Cys domain are common to the SUMO E1, the relatively large Cys domain of the Ub E1 contributes unique features to the closed conformation that are not observed in the SUMO E1. Due to its large size, in the closed conformation the buried surface area between the SCCH domain and the rest of the enzyme is ∼500 Å2 more than the corresponding buried surface in the closed conformation of the SUMO E1 structure. Moreover, the Ub E1 SCCH domain possesses unique interdomain interactions that are missing in the SUMO E1. Such interactions include S642 and S641 of the SCCH domain that in the closed conformation form hydrogen bonds with Q105, while in the open conformation are more than 40 Å away from that glutamine.

Next, to further understand the importance of these interactions, Hann et al. (6) tested a set of Ub E1 mutants using 2 different biochemical assays. One assay tested the ability of the UB-AVSN to generate a stable complex with Ub E1, therefore indirectly indicating the existence of a productive closed conformation. The other assay tested the whole activation process from Ub adenylation to thioester bond transfer to the E2. Interestingly, while several mutations increased or decreased the AVSN cross-linking, they showed a very mild effect on the rate of Ub transfer to E2. This supports what has been previously suggested, that the rate-limiting step in Ub activation is the transfer of Ub from the E1 to the E2. Taken together, in this work Hann et al. (6) provide 2 missing structures of Ub E1, one structure corresponding to the open conformation and the other to the closed conformation. In its catalytic cycle the Ub E1 acquires at least 2 conformations, open and closed. The open conformation is suitable for the adenylation reaction as well as for the transfer of Ub from the E1 to the E2, while the closed conformation is required for the thioester bond formation (Fig. 1).

It is well appreciated that significant structural understanding of the enzymes involved in Ub conjugation requires capturing the enzymatic reactions at distinct steps. Therefore, the work of Hann et al. (6) provides not only crucial structural data on Ub E1 activation, but also tools that enable the capture of adenylated UBLs and tetrahedral intermediates. Specifically, while both AMSN and AVSN have been used successfully with the SUMO E1 for structural work, here Hann et al. (6) modified the protocol for generating Ub-AVSN. This protocol not only increases the yield of Ub-AVSN, but also simplifies the procedure and minimizes the reaction time. This therefore will benefit structural studies on other E1 enzymes and specifically on noncanonical E1 enzymes. Noncanonical E1s do not have a Cys domain but rather have the catalytic Cys within the adenylation domain (15). To date, while crystal structures of noncanonical E1s alone or in complex with their cognate UBL and E2 have been solved (16–22), the structural basis of how these enzymes satisfy UBL adenylation and thioester bond formation is not yet clear.

Acknowledgments

Our research is supported by the Israel Science Foundation (Grant 1383/17), the Israel Cancer Research Fund, and the Israeli Cancer Association (Grant 20180069).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

See companion article on page 15475.

References

- 1.Hershko A., Ciechanover A., The ubiquitin system. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67, 425–479 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Komander D. The emerging complexity of protein ubiquitination. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 37, 937–953 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yau R., Rape M., The increasing complexity of the ubiquitin code. Nat. Cell Biol. 18, 579–586 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petroski M. D., The ubiquitin system, disease, and drug discovery. BMC Biochem. 9, S7 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cappadocia L., Lima C. D., Ubiquitin-like protein conjugation: Structures, chemistry, and mechanism. Chem. Rev. 118, 889–918 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hann Z. S., et al. , Structural basis for adenylation and thioester bond formation in the ubiquitin E1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 15475–15484 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lois L. M., Lima C. D., Structures of the SUMO E1 provide mechanistic insights into SUMO activation and E2 recruitment to E1. EMBO J. 24, 439–451 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olsen S. K., Lima C. D., Structure of a ubiquitin E1-E2 complex: Insights to E1-E2 thioester transfer. Mol. Cell 49, 884–896 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schäfer A., Kuhn M., Schindelin H., Structure of the ubiquitin-activating enzyme loaded with two ubiquitin molecules. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 70, 1311–1320 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walden H., et al. , The structure of the APPBP1-UBA3-NEDD8-ATP complex reveals the basis for selective ubiquitin-like protein activation by an E1. Mol. Cell 12, 1427–1437 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olsen S. K., Capili A. D., Lu X., Tan D. S., Lima C. D., Active site remodelling accompanies thioester bond formation in the SUMO E1. Nature 463, 906–912 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu X., et al. , Designed semisynthetic protein inhibitors of Ub/Ubl E1 activating enzymes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 1748–1749 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lake M. W., Wuebbens M. M., Rajagopalan K. V., Schindelin H., Mechanism of ubiquitin activation revealed by the structure of a bacterial MoeB-MoaD complex. Nature 414, 325–329 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tokgöz Z., Bohnsack R. N., Haas A. L., Pleiotropic effects of ATP.Mg2+ binding in the catalytic cycle of ubiquitin-activating enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 14729–14737 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schulman B. A., Harper J. W., Ubiquitin-like protein activation by E1 enzymes: The apex for downstream signalling pathways. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 319–331 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hong S. B., et al. , Insights into noncanonical E1 enzyme activation from the structure of autophagic E1 Atg7 with Atg8. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18, 1323–1330 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Noda N. N., et al. , Structural basis of Atg8 activation by a homodimeric E1, Atg7. Mol. Cell 44, 462–475 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oweis W., et al. , Trans-binding mechanism of ubiquitin-like protein activation revealed by a UBA5-UFM1 complex. Cell Rep. 16, 3113–3120 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taherbhoy A. M., et al. , Atg8 transfer from Atg7 to Atg3: A distinctive E1-E2 architecture and mechanism in the autophagy pathway. Mol. Cell 44, 451–461 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bacik J. P., Walker J. R., Ali M., Schimmer A. D., Dhe-Paganon S., Crystal structure of the human ubiquitin-activating enzyme 5 (UBA5) bound to ATP: Mechanistic insights into a minimalistic E1 enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 20273–20280 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaiser S. E., et al. , Noncanonical E2 recruitment by the autophagy E1 revealed by Atg7-Atg3 and Atg7-Atg10 structures. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19, 1242–1249 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamaguchi M., et al. , Noncanonical recognition and UBL loading of distinct E2s by autophagy-essential Atg7. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19, 1250–1256 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]