Abstract

Background:

Public health advocacy is by necessity responsive to shifting socio-political climates, and thus a challenge of advocacy research is that the intervention must by definition be adaptive. Moving beyond the classification of advocacy efforts to measurable indicators and outcomes of policy therefore requires a dynamic research approach.

Objectives:

The purpose of this article is to: 1) Describe use of the CBPR approach in the development and measurement of a community health worker intervention designed to engage community members in public health advocacy; and 2) Provide a model for application of this approach in advocacy interventions addressing community-level systems and environmental change.

Methods:

The Kingdon three-streams model of policy change provided a theoretical framework for the intervention. Research and community partners collaboratively identified and documented intervention data. We describe five research methods used to monitor and measure CHW advocacy activities that both emerged from and influenced intervention activities.

Discussion:

Encounter forms provided a longitudinal perspective of how CHWs engaged in advocacy activities in the three streams. Strategy maps defined desired advocacy outcomes and health benefits. Technical assistance notes identified and documented intermediate outcomes. Focus group and interview data reflected CHW efforts engage community members in advocacy and the development of community leaders.

Application of Lessons Learned:

We provide a model for application of key principles of CPBR that are vital to effectively capturing the overarching and nuanced aspects of public health advocacy work in dynamic political and organizational environments.

Keywords: Community advocacy, community health workers, community-based participatory research, policy development, methodological studies

Background

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is an approach guided by principles of community engagement in the collaborative production of knowledge (1) that encompasses a range of research designs and methods (2). The fundamental characteristic of CBPR is the partnership between the researcher and those affected by the issue under study (3). Co-governance of the research process between researchers and community members improves the identification of relevant and culturally-appropriate research questions, enhances data collection and interpretation, and facilitates translation of research findings into social change (4–7). In this paper, we describe use of the CBPR approach to cultivate a public health advocacy intervention led by community health workers (CHWs) and to collaboratively develop measures of community member engagement in CHW-driven public health advocacy efforts. We argue that the CBPR approach stimulates an evolution of research methods that is responsive to developing strategies and emerging outcomes of a community-level advocacy intervention addressing systems and environmental change.

Advocacy Research

Application of research findings to promote social change is intrinsic to CBPR (8, 9), and there are several examples in the literature on partnerships that use participatory research results to drive policy change (11–13). However, there are few instances in which policy change is the intervention being researched. Consequently, there is minimal guidance about how to achieve and measure policy outcomes (10, 11). A challenge of advocacy work is that the intervention and desired outcomes must by definition be adaptive (12). Standard evaluation methods set a priori to an advocacy intervention may fail to capture the nuanced aspects of the advocacy process. Moving beyond classification of advocacy efforts to measurable indicators and outcomes of policy change therefore requires a dynamic approach.

The Partnership

The community organizations and academic institution represented in this article have partnered for more than 15 years on research, program development and capacity building in communities along the southern Arizona border. The Arizona Prevention Research Center (AzPRC) provides an umbrella for university-community partnership research activities guided by a Community Action Board (CAB) of organizational representatives from four border counties. In 1999, we received a federal appropriation to focus on chronic disease prevention, and CAB members selected diabetes as the priority issue, with CHWs as the driving force for the intervention (13–16). Over time, AzPRC/CAB members began looking at chronic disease within the context of the social determinants of health and we shifted our focus from behavioral interventions to environmental and systems changes. Our current study, Acción Para La Salud (Action for Health), seeks to determine the effectiveness of a CHW intervention designed to engage community members in advocating for community-driven policy change within organizations, systems, and the broader social and physical environment.

Acción is governed by a research committee comprised of university-based team and representatives from a range of health organizations in which CHWs are core to health efforts. The research committee is responsible for guiding development of the intervention and how it is documented and measured. Partners from two community health centers, a grassroots clinic and a grassroots organization self-selected to participate directly in the research and identified two or three experienced CHWs on their staff to work on Acción. Approximately one-third of the Acción budget supports CHW time to train on, engage in and document community advocacy activities. Although the research committee oversees research methods, the Acción CHWs and their supervisors are integral in providing direct feedback regarding the utility of data collection strategies.

Methods

In this section we describe the process of developing methods to monitor and measure CHW advocacy activities that both emerged from and influenced intervention activities.

Acción Advocacy Intervention

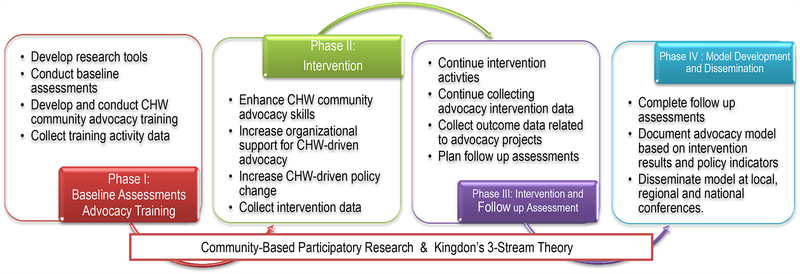

Acción has four phases (Figure 1). In the first, the AzPRC/CAB training committee developed and implemented CHW community advocacy training. We introduced Acción CHWs to Kingdon’s three streams concept (17) in which policy change results from the coalescence of a defined problem, a policy alternative and a supportive political climate. Between trainings, CHWs collected information related to the streams, first on the social, economic and political history of their communities, second on issues identified by community members, and third in documenting who has the power to make change. We are currently in the intervention phase, in which CHWs are planning, carrying out and documenting advocacy projects with ongoing technical assistance from the AzPRC team. The third phase will focus on follow up on baseline measures and policy outcomes, and the fourth on development of a CHW community advocacy model.

Figure 1:

Acción Research Plan

Monitoring and measurement

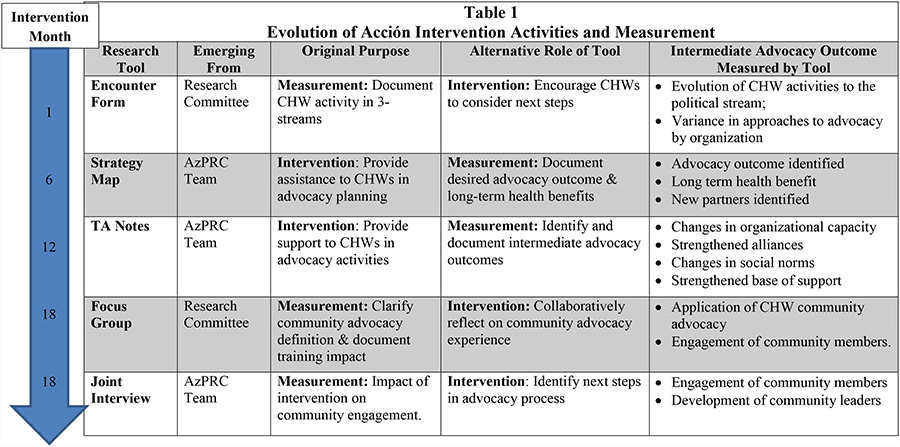

In the original research plan, AzPRC partners identified potential data sources to track CHW advocacy efforts and policy outcomes, including advocacy plans, CHW activity logs, media accounts, policy proposals, new policies and resource allocations. In practice, this exhaustive list overwhelmed the CHWs who were beginning to apply advocacy strategies and had not yet envisioned concrete policy or health outcomes. Responding to their feedback, we transitioned to collaboratively developing tools that both assisted CHWs in the intervention and also identified and documented intermediate advocacy outcomes. Fundamental to this method was the willingness of all partners to allow the intended intervention outcomes and measurements to evolve, with findings from one research method influencing further development of the intervention and documentation. Table 1 outlines five instruments we used to measure advocacy outcomes and/or to follow the intervention, when they were introduced, whether they emerged from the research or intervention, the role they played in advancing both the intervention and measurement and the intermediate advocacy outcome that was measured by each tool. All methods were approved by a human subject internal review board.

|

Encounter Forms:

The research committee developed the encounter forms prior to the intervention to document CHW interactions with community members. The encounter forms were grounded in the Kingdon framework to enable the identification of opportunities or ‘windows’ for policy change by tracking issues of concern to community members, potential solutions and the political climate for change. CHWs indicated on a single page the number of participants in the encounter activity, whether the encounter was formal or informal, and which stream(s) the contact addressed. The CHWs provided a narrative regarding the purpose of the encounter, what they discussed and planned next steps. Thus, while developed as a research tool, the encounter form also encouraged CHWs to develop advocacy projects.

Strategy maps:

CHWs found the encounter forms useful for documenting activities, but expressed frustration with their capacity to construct advocacy objectives and corresponding strategies. In response, the AzPRC team identified strategy maps (18) as a technical assistance tool. Strategy maps helped CHWs identify the what, who, how and when of an advocacy project and encouraged them to identify potential allies. During technical assistance visits, the AzPRC team facilitated an exercise to develop strategy maps based on issues CHWs had identified in the problem stream in their communities. The CHWs then developed their own strategy maps and updated them quarterly. Thus, the map also engaged the CHWs in defining and documenting measurable progress. On each map the CHWs: 1) defined their desired advocacy outcome; 2) identified the long term health benefits of a health advocacy intervention; and 3) identified intermediate outcomes such as creating new partnerships or developing community leaders.

Technical assistance notes:

Technical assistance meetings between the AzPRC team, CHWs and their supervisors were conceived as an exchange of ideas about how to develop advocacy efforts. As the AzPRC team became aware of the difficulty of identifying intermediate outcomes of the advocacy process and the complexity of capturing differences in approach between agencies, the conversations evolved as opportunities to describe specific achievements resulting from CHW activities. While we found few examples in the literature of standardized outcomes related to policy work that we could use to structure these discussions, The Guide to Measuring Advocacy and Policy provided us with a means to couple the strategy map with intermediate outcomes toward long-term policy change. The Guide recommends a process through which those involved in implementing and evaluating advocacy efforts apply a theory of change that connects activities with a collective vision, develop outcome categories related to advocacy and policy, and finally identify an approach for measurement (19). The AzPRC team chose four relevant outcome categories from the guide: 1) changes in social norms; 2) strengthened organizational capacity; 3) strengthened alliances; and 4) strengthened base of support. The AzPRC team modified the framework to a one-page menu of intermediate outcomes and translated it into Spanish. In the meetings, we systematically discussed these areas and identified examples of intermediate outcomes and the strategies used to achieve them. Through this lens, the CHWs began to consider the impact of their advocacy work on building community capacity.

CHW Focus group:

As the intervention evolved, the research committee struggled to determine how CHWs were applying the concept of community advocacy and whether they found Kingdon’s framework useful in moving their efforts forward. The committee decided to hold a researcher-facilitated focus group to give the CHWs an opportunity to discuss their understanding and application of community advocacy, along with their views of the Acción training and technical assistance on this experience. The objective of the focus group was to clarify these key aspects of the intervention. CHW efforts to engage community members in advocacy and the development of community leaders emerged as key outcomes for future study.

Joint interviews:

To further explore concepts of community engagement identified in the focus group and gather the community perspective on advocacy, a member of the AzPRC team developed a method called the CHW-Researcher Conversation Team (CHWRCT). The CHWRCT sought to situate the CHW and researcher as co-investigators to understand the experiences and transformations of community members involved in Acción. The CHWRCT method created a safe and conversational environment that enabled the participant and the CHW to reflect on their personal experiences in advocacy. The AzPRC team developed a general interview guide and a CHW who was involved in the advocacy effort worked with an AzPRC team member to modify the template based on what they were most interested in knowing about the project’s impact on the participant. Although specific questions varied by organization, instrument constructs the same across interviews and included descriptions of personal impact and transformation, plans for sustainability, or momentum of existing or new project identification. The AzPRC team member allowed the CHW to lead the conversation as the expert in the advocacy project and to ask specific questions to jog the memory of the participant regarding opportunities and challenges of the advocacy project. An informal debriefing followed between CHW and researcher to allow the CHW to reflect on and make meaning of the interview and perhaps identify next steps in the advocacy process.

Discussion

The evolution of methods to assess advocacy from the various perspectives outlined in this paper demonstrates the inherent value of CBPR in developing and measuring an advocacy intervention. The reciprocal and iterative nature of the CBPR approach allowed for collaborative identification of intermediate advocacy outcomes, or stepping stones toward actual policy targets and health outcomes. We present preliminary data from each method below with discussion of the influence of findings on the intervention.

Encounter forms

A systematic content analysis of one year of forms indicated that the CHWs were comfortable working in the problem stream, using various strategies to talk generally about community issues with clients and program participants (20). As they began to formulate ideas for advocacy projects, some CHWs began facilitating community meetings or forums to discuss identified problems, indicating a shift into the policy or solution stream. A small sample of the forms documented activity in the political stream, meeting with the mayor to discuss transit infrastructure, for example, and compiling information about patient preference for clinic hours to be communicated to the CEO. While the encounter forms served as a standardized data collection tool to measure the application of Kingdon’s 3-stream theory to CHW community advocacy activities, the format did not provide sufficient guidance to the CHWS in planning their next steps or how do follow up on what they documented on the form.

Strategy maps:

The encounter forms fell short in illustrating the emergence of concrete plans to achieve an advocacy objective, and the strategy map marked a turning point in the progress of the intervention and measurement. Desired advocacy outcomes and health benefits indicated on the initial maps included:

Extended clinic hours to increase access to health care for farmworkers

Public transportation infrastructure to increase communities’ access to services.

Establishment of safe routes to school to increase physical activity levels of youth.

Prohibited sale of energy drinks to minors to reduce related morbidity/mortality.

Content analysis of four strategy maps identified four common advocacy strategies across the four organizations designed to meet desired advocacy outcomes. 1) CHWs in three of the four organizations designed strategies to engage community members to discuss the issue and develop a solution through neighborhood meetings, parent/youth meetings, civic education, and a patient petition. 2) CHWS in three agencies developed strategies to collect more information regarding their issue. Two involved canvassing the community served by the agency, one used coalition partners to identify what current efforts, and the fourth relied on secondary data. 3) CHWs in two organizations identified partners to engage in their advocacy effort including law enforcement, city officials, social service providers, school districts, parks and recreation and local business. 4) CHWs in three organizations included plans to publicize their issue through the media, community forums, and a community awareness campaign. CHWs in two agencies used the strategy map as a tool for communicating with stakeholders, reformatting them and adding graphics.

Technical Assistance Notes

The technical assistance notes moved partners into the next stage of identifying intermediate outcomes of strategies outlined on the strategy maps. Changes in social norms involved the increased support for the issue resulting from CHW door-to-door education campaigns and community events. Changes in organizational capacity related to acceptance of CHW advocacy within the organization. One organization was cautious about advocacy because CHW efforts to identify community issues might results in client dissatisfaction. The CHWs carefully framed the issue of clinic hours as a mechanism for “positive improvement” and garnered support of decision makers. In another agency, the CHWs trained other CHWs in their organization in advocacy skill and expanded their job focus to include a broader scope of social and environmental issues impacting health. CHWs strengthened alliances through new partnerships with county health and transportation departments. In one agency, they collaborated with the police on community events to improve the cultural saliency of police conduct in the community. To strengthen their base of support, CHWs in two organizations mentored community members who then mobilized neighbors. In one case, CHWs used the binational radio station, newspapers and public libraries to communicate their success in establishing a transportation route from the U.S. port of entry to the hospital.

Focus Groups

The focus group revealed that Kingdon’s theory fell short in capturing a theme of central importance to the CHWs, that of identifying community members historically excluded or marginalized from decision-making processes and providing a structure in which they could exercise leadership. As one CHW explained, community advocacy “is to give our community the tools so that they are their own advocates, that they represent their communities more, so that in the future when we are no longer there we have taught them to defend themselves. Another CHW was specific in saying, “It is to teach them their rights as citizens and that we can enforce our rights. At times we need to form leaders, because people tell me that they go to city council meetings but that no one pays attention to them. We need to give them the tools and teach them how to be heard so they can achieve their goal.” The focus groups also helped clarify that while many of the advocacy strategies described in the strategy map and technical assistance meetings were familiar activities, the Acción intervention was crucial in helping CHWs organize their efforts. In the words of one CHW: “We have greater possibilities of achieving our goal. With more structure and organization there is much more possibility of achieving what will benefit the community or the patient, or what is favorable for them.” CHWs in two agencies emphasized a more profound impact of the intervention; “We have gone out of our comfort zone really….we have a broader scope of action.”

Joint interviews

The CHWRCT method created an opportunity to triangulate in real time the impact of the Acción intervention on community engagement from CHW, community member and researcher perspectives. To date, the AzPRC team has interviewed six community members who worked with CHWs from two partner agencies. Although the results are preliminary, themes of personal transformation and leadership development emerged. Community members reflected on changes in knowledge, belief and skill they gained through working with a CHW. They described increased self-confidence, power and skills to make change in their communities. They were less intimidated by decision makers and people in “powerful positions’. They felt their voice mattered and represented those of others who may not have such an opportunity. In one case, a leader said she felt “realizada” or “complete” as a human being following her participation. Another now represents her parent-teacher organization at the state level. One community leader organized her exercise group to attend and present their views on the city’s proposal to eliminate public space in which they held their classes.

Application of Lessons Learned

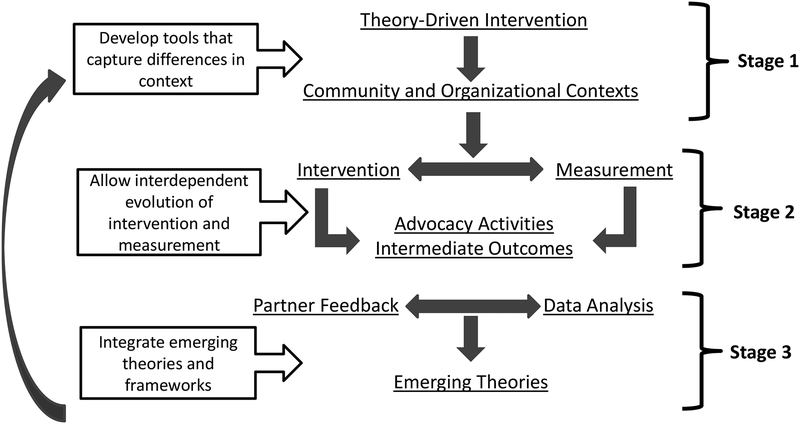

Our experiences in Acción lead us to conclude that key principles of a CBPR approach are vital to effectively capturing the overarching and nuanced aspects of public health advocacy work in dynamic political and organizational environments. Figure 2 describes a model for applying basic tenets of CBPR that are crucial to advocacy intervention development. These concepts occur in stages and build upon one another, but are also overlapping and iterative. The examples below describe each stage:

Figure 2:

CBPR Approach in the Development of Methods to Measure Community-Level Advocacy Interventions

Development of research within the contexts of communities and organizations. Context is central to the CBPR approach (21, 22) and an essential consideration in organizations with varied orientations toward advocacy work. Each CHW interpreted the encounter form differently based upon previous advocacy experience and the culture of their organization. After one year, the forms revealed patterns within each agency. In one organization the forms documented the influence of Acción in encouraging CHWs to take their clients’ issues up the decision-making ladder, in another how CHWs had expanded their role to work in new arenas, and in a third the ways CHWs were initiating conversations with clients about community issues in the context of their other job activities.

The iterative and interdependent development of both intervention and measurement: Consistent with the CPBR approach, intervention and evaluation research methods unfolded simultaneously, and in some cases the CHWs’ needs drove the development of the data collection tool. The strategy map was a response to CHWs’ request for technical assistance on initiating an advocacy effort. They were thrilled with the map because it displayed graphically on one page the self-determined steps of an advocacy project. In the words of one CHW, “with the map we have learned how to organize ourselves…we were already doing it, but we didn’t really know how to start, how to follow up, who to contact, who we should include. So this strategy map has been really useful.”

Integrate theories and frameworks that respond to partner feedback and emerging data: We integrated two additional contributions to our theoretical framework to understand and describe how CHWs were using community advocacy as a form of community engagement. The Guide to Measuring Advocacy and Policy provided us with a way to link CHW activities with concrete intermediate outcomes towards long-term policy change. The second is based on a meta-analysis of international development projects that provides a framework for CHW community engagement activities that have implications for public policy development (23).

Although policy has the potential to substantively alter conditions that impact health, achieving policy change is complex and the current literature provides little in the way of evidence-based practices. We recommend the development of methods within a CBPR approach to build skills at an advocacy level and to link those skills to the process of policy development and policy change.

Acknowledgements

This publication was supported by the Cooperative Agreement 5U48DP001925–24 from the Centers for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The authors would like to acknowledge organizations that participate on the AzPRC research committee in overseeing this research: Campesinos Sin Fronteras, Cochise County Health Department, El Rio Community Health Center, Mariposa Community Health Center, Pima County Health Department, Regional Center for Border Health, and Sunset Community Health Center. In addition, we would like to recognize the CHWs from the partner organizations who participated in both the design and implementation of the Acción study.

Contributor Information

Maia Ingram, University of Arizona Prevention Research Center.

Samantha J. Sabo, University of Arizona Prevention Research Center

Sofia Gomez, University of Arizona Prevention Research Center.

Rosalinda Piper, Mariposa Community Health Center.

Jill Guernsey de Zapien, University of Arizona Prevention Research Center.

Kerstin M. Reinschmidt, University of Arizona Prevention Research Center

Ken A. Schachter, University of Arizona Prevention Research Center

Scott C. Carvajal, University of Arizona Prevention Research Center

References

- 1.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health 1998;19:173–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jagosh J, Macaulay AC, Pluye P, Salsberg J, Bush PL, Henderson J, et al. Uncovering the benefits of participatory research: implications of a realist review for health research and practice. Milbank Q 2012;90(2):311–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Green LW, George MA, Daniel M, Frankish CJ, Herbert CJ, Bowie WR. Study of participatory research in health promotion. Ottawa. Ottawa: The Royal Society of Canada; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallerstein N, Duran B. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. Am J Public Health 2010;100 Suppl 1:S40–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arble B Participatory Research in Development of Public Health Interventions. Madison: University of Wisconsin: Population Health Institute; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hicks S, Duran B, Wallerstein N, Avila M, Belone L, Lucero J, et al. Evaluating community-based participatory research to improve community-partnered science and community health. Prog Community Health Partnersh 2012;6(3):289–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Viswanathan M, Ammerman A, Eng E, Garlehner G, Lohr K, Griffith D, et al. Community-based participatory research: Assessing the evidence. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2004. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Themba MN, Minkler M. Influencing policy through community based participatory research. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Israel BA, Coombe CM, Cheezum RR, Schulz AJ, McGranaghan RJ, Lichtenstein R, et al. Community-based participatory research: a capacity-building approach for policy advocacy aimed at eliminating health disparities. Am J Public Health 2010;100(11):2094–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Izumi BT, Schulz AJ, Israel BA, Reyes AG, Martin J, Lichtenstein RL, et al. The one-pager: a practical policy advocacy tool for translating community-based participatory research into action. Prog Community Health Partnersh 2010;4(2):141–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ritas C Speaking Truth Creating Power: A guide to policy work for community-based participatory research practitioners. In. http://www.ccph.info/: Community Campus Partnerships in Health; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Devlin-Foltz D, Fagen MC, Reed E, Medina R, Neiger BL. Advocacy evaluation: challenges and emerging trends. Health Promotion Practice 2012;13(5):581–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen SJ, Ingram M. Border health strategic initiative: overview and introduction to a community-based model for diabetes prevention and control. Prev Chronic Dis 2005;2(1):A05. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ingram M, Gallegos G, Elenes J. Diabetes is a community issue: the critical elements of a successful outreach and education model on the U.S.-Mexico border. Prev Chronic Dis 2005;2(1):A15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Staten LK, Scheu LL, Bronson D, Peña V, Elenes J. Pasos Adelante: the effectiveness of a community-based chronic disease prevention program. Prev Chronic Dis 2005;2(1):A18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teufel-Shone NI, Drummond R, Rawiel U. Developing and adapting a family-based diabetes program at the U.S.-Mexico border. Prev Chronic Dis 2005;2(1):A20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kingdon J Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies. New York: Longman; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zacoks R, Dobson N, Kabel C, Briggs S. Framework and tools for evaluating progress toward desired policy and environmental changes: A guidebook informed by the NW community changes initiative In: NW Community Changes Guidebook; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reisman J, Gienapp A, Stachowiak S. A guide to measuring advocacy and policy. In. Baltimore Maryland: Annie E. Casey Foundation; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ingram M, Shachter K, Sabo SJ, Reinschmidt KM, Guernsey de Zapien J, Carvajal SC. Brief Report: A community health worker intervention to address the social determinants of health through policy change. Journal for Primary Prevention; Accepted for Publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ibanez-Carrasco F, Riano-Alcala P. Organizing community-based research knowledge between universities and communities: lessons learned. Journal of Community Development 2011;26(1):72–88. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goins RT, Garroutte EM, Fox SL, DG S, Manson SM. Theory and Practice in Participatory Research: Lessons from the Native Elder Care Study. The Gerontologist 2011;51(3):285–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gaventa JK, Barrett G. So What Difference Does It Make? Mapping the Outcomes of Citizen Engagement In: B G, editor. Working Paper. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies; 2010. [Google Scholar]