Abstract

Seizures are very common in the early periods of life and are often associated with poor neurologic outcome in humans. Animal studies have provided evidence that early life seizures may disrupt neuronal differentiation and connectivity, signaling pathways, and the function of various neuronal networks. There is growing experimental evidence that many signaling pathways, like GABAA receptor signaling, the cellular physiology and differentiation, or the functional maturation of certain brain regions, including those involved in seizure control, mature differently in males and females. However, most experimental studies of early life seizures have not directly investigated the importance of sex on the consequences of early life seizures. The sexual dimorphism of the developing brain raises the question that early seizures could have distinct effects in immature females and males that are subjected to seizures. We will first discuss the evidence for sex-specific features of the developing brain that could be involved in modifying the susceptibility and consequences of early life seizures. We will then review how sex-related biological factors could modify the age-specific consequences of induced seizures in the immature animals. These include signaling pathways (e.g., GABAA receptors), steroid hormones, growth factors. Overall, there are very few studies that have specifically addressed seizure outcomes in developing animals as a function of sex. The available literature indicates that a variety of outcomes (histopathological, behavioral, molecular, epileptogenesis) may be affected in a sex-, age-, region- specific manner after seizures during development. Obtaining a better understanding for the gender-related mechanisms underlying epileptogenesis and seizure comorbidities will be necessary to develop better gender and age appropriate therapies.

Keywords: animal models, epilepsy, early life seizures, GABA, sex differences, status epilepticus, development, substantia nigra, hippocampus

Introduction

Early life seizures are among the most common clinical signs of brain dysfunction. They can be caused by genetic abnormalities or acquired insults such as perinatal asphyxia, traumatic brain injury, intracranial hemorrhage, central nervous system infection, malformations of cortical development, metabolic disturbances or just fever (Annegers et al., 1995; Chapman et al., 2012; Huang et al., 1998; Jensen, 2009; Sillanpaa et al., 2008; Tekgul et al., 2006; Verity et al., 1985). In humans, early onset seizures including neonatal seizures not associated with acute metabolic derangements, and particularly status epilepticus (SE), have been linked to poor neurologic outcome and increased risk of subsequent neurodevelopmental dysfunction and epilepsy (Brunquell et al., 2002; Holmes, 2009; Ronen et al., 2007; Sheppard and Lippe, 2012). Animal studies have corroborated these observations showing that the immature brain is more prone to seizures but more resilient to seizure-induced histopathological injury to the hippocampus or epileptogenesis compared with the adult brain (Albala et al., 1984; Friedman and Hu, 2014; Galanopoulou, 2008a; Galanopoulou and Moshe, 2009; Galanopoulou et al., 2002; Holmes, 2005; Nardou et al., 2013; Sperber et al., 1991). Early life seizures may, under certain circumstances, adversely alter the developing brain and disrupt neuronal differentiation, signaling and connectivity, and ultimately the function of specific neuronal networks (Auvin et al., 2012; Ben-Ari and Holmes, 2006; Sankar and Rho, 2007; Scantlebury et al., 2007). Among the factors contributing to the different effects of early life seizures are the incomplete maturation of the operant neurotransmitter systems and networks, metabolic factors, or interactions with environmental or systemic factors. In experimental studies, the consequences of early life seizures are strongly age- and model- dependent.

Incidence studies have indicated a higher incidence of acute symptomatic seizures (excluding febrile seizures) in males than in females, including in pediatric populations (Annegers et al., 1995). The age-specific incidence of acquired (nongenetic) epilepsy, in general, is only mildly higher in males than in females (Hauser et al., 1993; Kotsopoulos et al., 2002) without statistically significant sex differences (Perucca et al., 2014). However interesting sex-specific differences emerge when specific seizure syndromes or epilepsies are considered. Females appear to have greater risk for generalized-onset epilepsy in general (Hauser et al., 1993), childhood absence, or photosensitive seizures of genetic or unknown etiology (Asadi-Pooya et al., 2012; Nicolson et al., 2004; Taylor et al., 2013; Taylor et al., 2004), or febrile status epilepticus (Hesdorffer et al., 2013). In contrast, mild male predominance has been shown in Landau-Kleffner syndrome, West and Lennox Gastaut syndromes, and severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy (Aicardi and Chevrie, 1970; Galanopoulou et al., 2000; Tsai et al., 2013; Widdess-Walsh et al., 2013). Regarding the consequences of seizures, clinical and epidemiological studies indicate sex-differences in the natural course of epilepsy in adults. However, very few conclusive clinical studies exist on sex-specific outcomes in very young individuals with seizures or epilepsies, due to experimental limitations.

Despite the obvious phenotypic differences between males and females, most of the preclinical studies on the consequences of early life seizures have been performed either only in male animals or the sex distribution of the subjects has not been reported. Increasing evidence supports that the sexual dimorphism of the brain starts very early in life, differentially affecting molecular signaling pathways, physiologic functions or morphologic attributes, including of brain regions classically involved in seizure expression and control. If the male and female brains operate differently, it would be expected that early seizures should have sex-specific effects. Indeed, few studies have started evaluating the sex-specific effects of early life seizures on neurogenesis, GABAergic or other signaling pathways, behavioral tests, or subsequent injury (Castelhano et al., 2010; Desgent et al., 2012; Galanopoulou, 2008a; Lemmens et al., 2005). It is less clear whether these changes lead to distinct long-term epilepsy or functional outcomes. In this review, we will discuss the animal studies on the sex-specific acute and long-term consequences of early life seizures and will discuss the underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms.

Why look for sex-specific effects of seizures?

Brain maturation is a long process of evolving changes in neurogenesis and migration, gliogenesis, cellular differentiation, synaptogenesis, myelination and synaptic pruning, all of which can be affected by the ongoing developmental processes that occur in systems outside the CNS. It is controlled by species-specific, genetic or non-genetic biological, environmental or epigenetic factors, many of which influence differently males and females. In humans, brain maturation begins about 3 weeks after conception and continues until about 30 years of life (Kolb et al., 2013). To facilitate the comparison between humans and rodents, Table 1 outlines the chronology of developmental stages in male and female rats. Postnatal (PN) 8–10 rodents have been suggested to be developmentally equivalent to human newborn babies, because the rate of brain growth, and its DNA, cholesterol and water contents resemble those of a human full-term neonate (Dobbing and Sands, 1979; Gottlieb et al., 1977). The infantile stage extends until PN21 with peaks of the myelination rate and synaptic density at PN20–21 (Semple et al., 2013). The onset of puberty (early pubertal stage in Table 1) is between PN32–36 (females) and PN35–45 (males), while rodents are considered young adults on PN60 (Ojeda et al., 1980). This is however only a simplified schema of the equivalency of developmental processes between rodents and humans as several developmental processes proceed at different tempos across species (Avishai-Eliner et al., 2002).

Table 1.

Developmental stages in rats, based on hypothalamus-pituitary-gonadal maturation

| Stage | Females | Males | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PN | Features | PN | Features | |

| Neonatal | 0–6 | 0–6 | ||

| Infantile | 7–21 | 7–21 | ||

| Juvenile | 21–32 | 21–35 | ||

| Early pubertal | 32–36 | Anestrus to early proestrus; pulsatile gonadotropin release in sleep only | 35–45 | Pulsatile gonadotropin release in sleep only |

| Puberty | 34–38 | 1st proestrus, first estrus; 1st surge of gonadotropins and vaginal opening | 45–60 | Gonadotropin release also in wakefulness;

Maximal testicular response to gonadotropins; Increase in Leydig cells and steroidogenesis |

| Adult | >60 | >60 | ||

The table is based on reference (Ojeda et al., 1980). Please note that these age groups have been defined based on the endocrine changes occurring during maturation and not brain maturation. In general, PN8–10 rats are considered equivalent to full-term newborn humans, based on gross brain growth and its DNA, cholesterol and water contents that resemble those of a human full-term neonate (Dobbing and Sands, 1979; Gottlieb et al., 1977).

Similar to the earlier sexual maturation of females (see Table 1), brain maturation also follows different paths in males and females, which affect protein expression and function, neurogenesis and migration, cellular physiology and differentiation (Table 2) and function (Giorgi et al., 2014), or the interactions of the CNS with other biological systems or environmental factors. Here we will highlight some of the sex-specific features of factors that may influence the sex-specific outcomes of early life seizures.

Table 2.

Sex-specific features in the brain of immature rodents.

| Feature | Species, brain region | Age | Sex-specific findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GABA signaling | ||||

| GABRA1 mRNA | Sprague-Dawley Rat SNR | PN15, PN30 | F>M | (Ravizza et al., 2003) |

| GABRA1 mRNA | Long Evans Rat SS cortex and SS thalamus | PN7, PN14, PN35, PN60 | F=M (PN7, PN14) F<M (PN35, PN60) |

(Li et al., 2007) |

| GABRA1 protein and zolpidem sensitivity of IPSCs | Sprague-Dawley Rat SNR | PN5, PN15, PN30 | F>M F=M |

(Chudomel et al., 2009) |

| GABRA3 protein | Sprague-Dawley Rat SNR | PN5, PN15, PN30 | F>M F=M |

(Chudomel et al., 2009) |

| GABAAR IPSCs - baseline IPSCs | Sprague-Dawley Rat SNR | PN5–9 PN28–32 |

F<M: frequency, amplitude,

charge/event F<M: amplitude F>M: decay and rise times |

(Chudomel et al., 2009) |

| GABRG2 mRNA | Long Evans Rat SS cortex | PN7, PN14, PN35, PN60 |

Somatosensory

Cortex: F=M (PN7, PN14) F<M (PN35, PN60) Somatosensory Thalamus: F=M (PN7, PN14, PN60) F<M (PN35) |

(Li et al., 2007) |

| GAD mRNA | Sprague-Dawley Rat, dorsomedial nucleus, arcuate nucleus, CA1 | PN1 PN15 |

F<M F=M |

(Davis et al., 1996) |

| GABA content | Sprague-Dawley Rat SNR | PN15, PN30 | F>M | (Ravizza et al., 2003) |

| GABA-ir cells | Sprague-Dawley Rat striatum | E16–22 | F>M | (Ovtscharoff et al., 1992) |

| GABA-ir cells or parvalbumin GABAergic neurons | Sprague-Dawley Rat SNR | PN15, PN30 | F>M | (Galanopoulou et al., 2001; Ravizza et al., 2003) |

| GABAAR switch to hyperpolarizing | Sprague-Dawley Rat SNR | PN4–26 | F: PN10 M: PN17 |

(Kyrozis et al., 2006) |

| GABAAR switch to hyperpolarizing | Sprague-Dawley Rat CA1 pyramidal neurons | PN4–18 | F: isoelectric or hyperpolarizing responses

from PN4 M: PN14 |

(Galanopoulou, 2008a) |

| Muscimol effects on Vm, in vitro | Sprague-Dawley Rat SNC | PN15 | F: no effect M: depolarization |

(Galanopoulou, 2006) |

| Muscimol effects on pCREB, in vivo | Rat hypothalamus, CA1 pyramidal neurons | Neonatal | F: decrease in pCREB-ir M: increase in pCREB-ir |

(Auger et al., 2001) |

| Muscimol effects on pCREB, n vivo | Rat SN | PN15 | F: no effect M: increase in pCREB-ir and KCC2 mRNA |

(Galanopoulou, 2006; Galanopoulou et al., 2003b) |

| GABRB1 | Sprague-Dawley Rat hypothalamus | PN1–38, adult |

GABRB1a F>M (PN1) F<M (PN38) GABRB1b: F=M GABRB2: F=M |

(Bianchi et al., 2005) |

| GABRB1 | Sprague-Dawley Rat anterior pituitary | PN4-PN38, adults |

GABRB1a F>M (PN4, 12) GABRB1b: F: very low M: barely detectable GABRB2: F, M: barely detectable |

(Bianchi et al., 2001) |

| Effects of intranigral muscimol infusions, in vivo | Sprague-Dawley Rat SNR | PN15-PN60 | Sex specific effects on flurothyl seizure threshold | (Veliskova and Moshe, 2001) |

| GABAergic neurons | Sprague-Dawley Rat striatum | E26, E18, E20, E21 | F>M | (Ovtscharoff et al., 1992) |

| Cation Cl− Cotransporters | ||||

| KCC2 protein | Sprague-Dawley Rat CA1 pyramidal hippocampal neurons | PN10 | F>M | (Galanopoulou, 2008a) |

| KCC2 protein | Wistar Rat hippocampus | PN1–15 | F>M (PN5–15) | (Murguia-Castillo et al., 2013) |

| KCC2 protein | Wistar Rat entorhinal cortex | PN1–15 | F>M (PN9–15) | (Murguia-Castillo et al., 2013) |

| KCC2 mRNA | Sprague-Dawley Rat hippocampus (CA1, CA3, DG) | PN5, PN8 | F=M | (Damborsky and Winzer-Serhan, 2012) |

| KCC2 mRNA | Sprague-Dawley Rat SNR | PN15, PN30 | F>M | (Galanopoulou et al., 2003b) |

| KCC2 protein | Sprague-Dawley Rat hypothalamus | E20, PN0, PN5 | F>M (PN5) | (Perrot-Sinal et al., 2007) |

| KCC2 mRNA | Sprague-Dawley Rat hypothalamus | E20, PN0, PN5 | F>M (PN0) | (Perrot-Sinal et al., 2007) |

| NKCC1 mRNA | Sprague-Dawley Rat hippocampus (CA1, CA3, DG) | PN5 PN8 |

F<M F=M |

(Damborsky and Winzer-Serhan, 2012) |

| NKCC1 protein | Wistar Rat hippocampus | PN1–15 | F<M (PN9) F>M (PN7, 13) |

(Murguia-Castillo et al., 2013) |

| NKCC1 protein | Wistar Rat entorhinal cortex | PN1–15 | F<M (PN5, PN9, PN11) | (Murguia-Castillo et al., 2013) |

| NKCC1 protein | Sprague-Dawley Rat hypothalamus | E20, PN0 | F<M | (Perrot-Sinal et al., 2007) |

| NKCC1 mRNA | Sprague-Dawley Rat hypothalamus | E20, PN0, PN5 | F<M (PN0) | (Perrot-Sinal et al., 2007) |

| Glutamatergic signaling | ||||

| NR1 protein | Long Evans Rat preoptic area | E16, PN1, PN3 | F<M | (Hsu et al., 2000) |

| NR2A mRNA | Sprague-Dawley Rat hippocampus (CA1, CA3, DG) | PN5 PN8 |

F<M F=M |

(Damborsky and Winzer-Serhan, 2012) |

| NR2B mRNA | Sprague-Dawley Rat hippocampus (CA1, CA3, DG) | PN5 PN8 |

F>M F=M |

(Damborsky and Winzer-Serhan, 2012) |

| GluR1 | C57BL/6 mice Hippocampus |

PN0, PN7, PN14, PN30, PN60 | F>M (PN0) F<M (PN7, PN14, PN30, PN60) |

(Bian et al., 2012) |

| Cholinergic system | ||||

| High affinity choline uptake | Wistar Rat hippocampus | PN7, PN14, 3 months | F: no lateralization M: left lateralization of Vmax [left > right) (PN14, 3 months)] |

(Kristofikova et al., 2004) |

| Nicotine effects on KCC2 and BDNF | Sprague-Dawley Rat hippocampus (CA1, CA3, DG) | PN5, PN8 |

Daily nicotine

po F: no effect M: increase in KCC2, BDNF mRNA |

(Damborsky and Winzer-Serhan, 2012) |

| Muscarinic receptors | Sprague-Dawley Rat cortex (cingulate, parietal), hippocampus | Adult | M1 receptor binding: M>F

(CA1) M3 mRNA: M>F |

(Potier et al. 2005) |

| Catecholaminergic system | ||||

| Tyrosine hydroxylase positive axons | Sprague-Dawley Rat striatum | E26, E18, E20, E21 | F>M | (Ovtscharoff et al., 1992) |

| Dopamine levels | BALB/cByJ mice, cerebral cortex, hypothalamus | PN3 | F<M | (Connell et al., 2004) |

| Dopamine, Serotonin (5-HT), Dihydroxyphenylacetic acid, Homovanillic acid, 5-hydroxyindoloacetic acid (5-HIAA) | Rat Caudate |

PN0–30 | F=M | (Restani et al., 1990) |

| Dopamine | Rat | PN35 | F=M (midbrain, prefrontal cortex, striatum) | (Llorente et al., 2010) |

| 5HT | Rat | PN35 | F>M (striatum) F=M (midbrain, prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, cerebellum |

(Llorente et al., 2010) |

| Dopaminergic neurons | CBA/J mice Substantia nigra Ventral tegmental area |

E21 – PN90 | F=M | (Lieb et al., 1996) |

| Dopamine beta-hydroxylase | Rat Plasma |

PN5-adulthood | F>M | (Koudelova and Mourek, 1990) |

| Other | ||||

| BDNF mRNA | Sprague-Dawley Rat hippocampus (CA1, CA3, DG) | PN5, PN8 | F<M (PN5) | (Damborsky and Winzer-Serhan, 2012) |

| BDNF, NGF, NT-3, trkB mRNA | Rat Ventromedian nucleus of hypothalamus) |

E20, PN4 | F=M | (Sugiyama et al., 2003) |

| Anti-NGF treatment | Wistar Rat | PN0–12 qod anti-NGF treatment |

PN16 choline

acetyltransferase in cortex: F: no effect M: reduced |

(Ricceri et al., 1997) |

| Bcl-2 protein | Long Evans Rat preoptic area | PN8 | F<M | (Hsu et al., 2000) |

| IGF-1R positive cells | Wistar Rat hippocampus | PN0 PN7 PN14 |

F>M (CA1, CA3, DG) Right: F<M (DG) Left: F>M (CA1, CA3, DG) Right: F<M (CA1, DG) Left: F<M (CA1, CA3, DG) |

(Hami et al., 2013) |

| Morphology, neurogenesis | ||||

| Dendritic spine number | Rat ventromedial nucleus of hypothalamus | PN2 | F<M | (Todd et al., 2007) |

| NeuN positive cells | Hippocampus | PN7 | F<M (CA1, CA2/3, DG) | (Hilton et al., 2003) |

| Amygdalar, hippocampal growth | Humans | 0–25 years |

Age of amygdala

peak volume: F: L/R = 9.6/11.4 years; earlier subsequent growth deceleration in F M: L/R = 11.1/12.6 years Rightward laterality: F: L<R hippocampus M: L<R hippocampus and amygdala Hippocampal volume: F<M |

(Uematsu et al., 2012) |

| Dendritic tree | Long Evans hooded Rat dentate granule cells of hippocampus | PN25, adults |

Number of dendritic

segments: F>M (PN25 only) Length of individual dendritic segments: F=M (PN2, adults) |

(Juraska, 1990) |

| Neurogenesis in dentate gyrus | Sprague-Dawley Rat | 4 week old | F<M | (Perfilieva et al., 2001) |

Abbreviations: BDNF: Brain-derived neurotrophic factor; DG: dentate gyrus; F: females; GABA: gamma-aminobutyric acid; GABRA1: GABAA receptor α1 subunit; GABRA3: GABAA receptor α3 subunit; GABRB1: GABAB receptor 1 subunit; GABRG2: GABAA receptor γ2 subunit; GAD: glutamic acid decarboxylase; GluR1: AMPA-type glutamate receptor 1; IGF-1R: insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor; IPSCs: inhibitory postsynaptic currents; -ir: -immunoreactivity; KCC2: potassium/chloride co-transporter 2; L: left; M: males; NGF: Nerve growth factor; NKCC1: sodium/potassium/chloride co-transporter 1; NR1: NMDA receptor subunit 1; NR2A: NMDA receptor subunit 2A; NR2B: NMDA receptor subunit 2B; pCREB: phosphorylation of cAMP responsive element binding protein at Ser133; R: right; SNC: substantia nigra pars compacta; SNR: substantia nigra pars reticulata; SS: somatosensory.

GABA signaling

GABAA receptor (GABAAR), and to a lesser extent GABABR signaling pathway, has been extensively studied as to its sex-specific features. These features include sex-specific differences in (a) the developmental expression patterns of various GABAAR subunits, (b) kinetics, amplitude, and agonist sensitivity of GABAAR inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs), (c) GABA content in certain brain regions, (d) the timing of the developmental shift from depolarizing to hyperpolarizing GABAAR signaling, as well as (e) the responsiveness of seizure control networks to GABAARs that may modify the strength of the pro- or anticonvulsant effects (Table 2) (Giorgi et al., 2014).

In general, the trend of changes observed in the GABAergic system favor an earlier maturation of certain aspects of the GABA-mediated inhibition in certain sexually dimorphic brain regions of the immature females. For instance, the GABAergic neurons of the substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNR) appear to have an earlier peak of neurogenesis prenatally (Galanopoulou et al., 2001), are more abundant in the developing SNR (Galanopoulou et al., 2001; Ravizza et al., 2003), demonstrate earlier developmental rise in the expression of the α1 GABAAR subunit (Chudomel et al., 2009; Ravizza et al., 2003), which then renders them more sensitive to α1-selective GABAAR agonists in developing females compared with males (Chudomel et al., 2009). As detailed also in the review by Giorgi et al (2014) the earlier maturation of the female SNR extends to the earlier appearance of its muscimol-sensitive anticonvulsant function in the anterior SNR (Veliskova and Moshe, 2001). However, exceptions can be seen in certain regions, where the expression of glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD; GABA synthesizing enzyme) mRNA in the CA1 region of hippocampus and dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus is higher in males than in females (Davis et al., 1996).

Of particular interest is the earlier appearance of hyperpolarizing GABAAR signaling in certain sexually dimorphic brain structures, like the rat substantia nigra, CA1 pyramidal hippocampal neurons, or hypothalamus which results from the higher expression of Cl− exporters, like potassium-chloride cotransporter-2 (KCC2), and lower levels of Cl− importers, like sodium-potassium-chloride cotransporter-1 (NKCC1), in developing females (Galanopoulou, 2003; Galanopoulou, 2006, 2008a; Kyrozis et al., 2006; Murguia-Castillo et al., 2013; Nunez and McCarthy, 2007). The role of cation Cl− cotransporters (CCCs) in the regulation developmental changes in GABAAR signaling and their impact on neuronal activity and age and sex-specific transcriptional control are depicted in Figure 1. The timing of the shift from depolarizing to hyperpolarizing GABAAR signaling is different for different cell types and brain regions and appears to be important for normal brain development. Failure to develop hyperpolarizing GABAAR signaling by KCC2 knockout can be lethal (Hubner et al., 2001). In contrast, early termination of depolarizing GABAAR signaling in developing cortical neurons may disrupt dendritic arborization and formation of dendritic spines, having severe consequences on functions that depend on sensorimotor gating (Cancedda et al., 2007; Wang and Kriegstein, 2009, 2011).

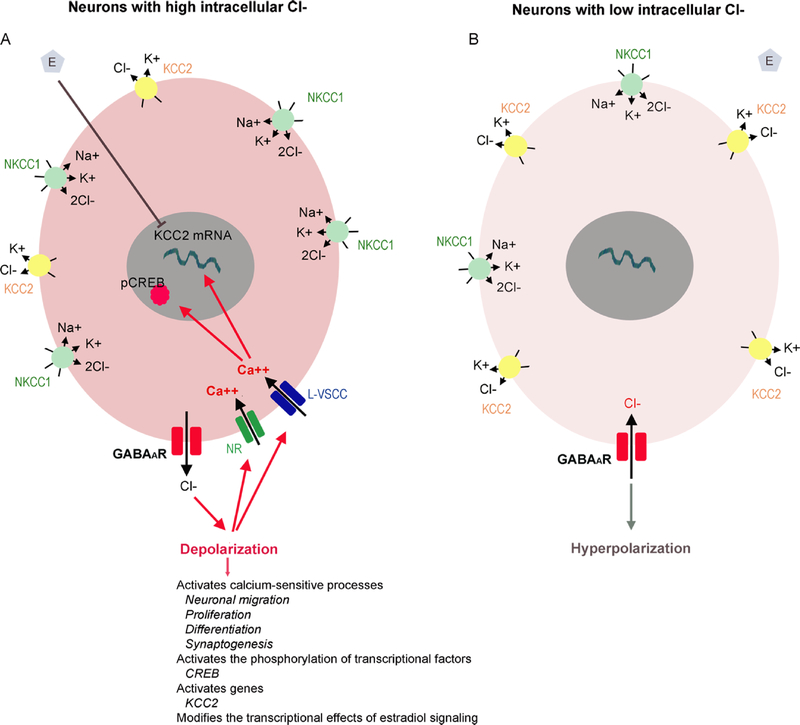

Fig 1:

Sex-specific developmental changes in the direction of GABAAR signaling are determined by cation chloride cotransporters.

Panel A: Early in life, in most studied neurons, the intracellular Cl− concentration is higher than in adults, due to the functional dominance of cation chloride cotransporters (CCCs) that import Cl−, like the Na+/K+/Cl− cotransporter NKCC1, over cotransporters that export Cl−, like the K+/Cl− cotransporter KCC2 (Plotkin et al., 1997; Rivera et al., 1999). As a result of this intracellular accumulation of Cl−, activation of GABAAR triggers Cl− efflux, neuronal depolarization that activates L-type voltage-sensitive calcium channels (L-VSCCs) or NMDA receptors (NRs) triggering intracellular calcium increases that eventually activate calcium-sensitive processes that are important in neuronal migration, proliferation, differentiation and synaptogenesis (Ben-Ari, 2002; Farrant and Kaila, 2007; Galanopoulou, 2008b). For example, GABAAR-induced calcium rises activate the phosphorylation of certain transcriptional factors, like cAMP responsive element binding protein (CREB), and genes (e.g. KCC2). Furthermore, 17β-estradiol can downregulate KCC2 mRNA expression only in neurons that demonstrate depolarizing GABAAR signaling. In certain sexually dimorphic brain regions, like the hypothalamus, CA1 pyramidal hippocampal neurons and substantia nigra, the developmental period when depolarizing GABAAR signaling is observed is protracted, compared to same age females and this possibly contributes to the sex-specific differentiation of these regions.

Panel B: During development, a gradual shift in the balance of these transporters from NKCC1 dominant to KCC2 dominant state is responsible for the switch of GABAAR signaling from depolarizing to hyperpolarizing (Galanopoulou, 2008c; Plotkin et al., 1997; Rivera et al., 1999). The increased KCC2 and decline in NKCC1 activity reduce the inracellular Cl− levels. Therefore, GABAAR activation results in hyperpolarization. This strengthens the GABAAR inhibition but also abolishes the transcriptional effects observed by depolarizing GABAAR signaling.

This Figure has been modified with permission from (Galanopoulou, 2008c).

The prolonged developmental windows when GABAAR signaling is depolarizing in males compared with females in these structures are likely to directly influence the patterns of responses to afferent GABAergic projections and consequently the neuronal activity and intracellular signaling responses of these sexually dimorphic structures. This has been well illustrated in vitro with gramicidin perforated patch clamp studies, where electrical stimulation of GABAergic afferents or bath application of GABAAR agonists evoked depolarizing responses, intracellular calcium rises, only in males but elicited isoelectric or inhibitory responses in same age immature female GABAergic SNR or dopaminergic substantia nigra pars compacta (SNC) or CA1 pyramidal neurons (Galanopoulou, 2003; Galanopoulou, 2006, 2008a). As a result, in vivo systemic administration of GABAAR agonists, like muscimol, enhances the activity of calcium-sensitive signaling targets in these sexually dimorphic nuclei of male rats but not in same age females. Thus, muscimol can increase the phosphorylation of cAMP responsive element binding protein (pCREB) in the PN15 male SNR and SNC neurons but has no effect in same age females (Galanopoulou, 2003; Galanopoulou, 2006) and may also modify, in a sex-specific pattern, the downstream effects of other signaling that are critical for normal development, as has been described for estradiol (Galanopoulou, 2006; Galanopoulou and Moshe, 2003). Similar observations were also reported in the neonatal rat hypothalamus and hippocampus, where in vivo systemic muscimol administration increased pCREB immunoreactivity (-ir) in males but reduced it in females (Auger et al., 2001). Depolarizing GABAAR can also permit the transcriptional regulation of certain genes (e.g., KCC2) by estradiol, during the perinatal period, facilitating possibly the masculinization of certain brain regions that are exposed to higher local estradiol levels in males derived either through aromatization by the perinatal testosterone surge or from local steroidogenesis. These sex-specific transcriptional effects are therefore likely to produce more persistent effects promoting the sexual dimorphism of the targeted neurons (Galanopoulou, 2008c). GABAAR signaling also plays a major role in the control of seizures and their consequences, raising the question of whether such sex differences could also set the ground for sex-specific consequences of early life seizures.

Fewer studies have looked into the sex-specific features of GABABR signaling and these have focused on the expression of GABABR subunits in the hypothalamus and anterior pituitary, where GABRB1a was expressed at higher levels in neonatal females than in males. In the hypothalamus, GABRB1a declined more in peripubertal females than in males, an event that was thought to be linked to the onset of puberty (Table 1) (Bianchi et al., 2001; Bianchi et al., 2005).

Glutamatergic receptors

NMDA receptors (NR) are ligand gated cation channels that are tetramers comprised usually of two NR1 subunits, that bind glycine, and two NR2 subunits which bind L-glutamate (Benarroch, 2011). NR1/NR2A receptors are mostly postsynaptic and their intracellular effects may promote neuroprotection and synaptic plasticity whereas NR1/NR2B receptors are usually extrasynaptic and mediate the pro-apoptotic effects in the setting of excessive NR activation. NR binding in the hippocampus increases with age in a region-specific manner (Insel et al., 1990). Region and subunit specific changes have been reported, with different patterns in mRNA and protein studies (reviewed in (Szczurowska and Mares, 2013)). In many regions including the hippocampus and cerebral cortex, there seems to be predominantly NR1/NR2B expression perinatally followed by a dramatic increase in NR2A during the first three first postnatal weeks (Chang et al., 2009; Ling et al., 2012; Sans et al., 2000; Szczurowska and Mares, 2013; Zhong et al., 1995). Interestingly, newborn male rats have higher expression of NR2A and lower expression of NR2B in their hippocampus on PN5 compared to females, whereas such differences are not present at older ages (Damborsky and Winzer-Serhan, 2012). NR1 protein expression in the preoptic nucleus is also higher in males than in females during the embryonic and early postnatal periods, which has been proposed to be important for the presence of perinatal testosterone surge in males and for reducing apoptosis (Hsu et al., 2000). It is therefore possible that in females, during the early postnatal period, there may be fewer synaptic NRs – and more silent synapses – in these brain regions.

The α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptors (AMPA-R) are heteromeric complexes comprised of combinations of GluR1-GluR4 and elicit the fast excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs). The presence of GluR2 renders AMPA-R calcium-impermeable; consequently, the low levels of GluR2 early in life allows for more calcium-permeable AMPA-Rs (Pellegrini-Giampietro et al., 1992; Pellegrini-Giampietro et al., 1997). There is no report of sexspecific expression of GluR2 in the developing brain, although sex-specific regulation by estradiol has been reported in adult rat hypothalamus (Diano et al., 1997). In contrast, GluR1 expression is higher in the male PN0 hippocampus, whereas it becomes predominant in PN7–60 females (Bian et al., 2012).

Metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR) control neuronal activities and differentiation by influencing the activity of other ion channels (e.g., NRs, L-VSCCs) or intracellular signaling pathways. There is currently no report of sex specific expression in the brain for any of the eight known mGluRs.

Catecholaminergic system

The sexual dimorphism of the dopaminergic system perinatally also defines social behavior later in life (Auger and Olesen, 2009). During the neonatal period, males have higher dopamine levels in the cerebral cortex and hypothalamus than female mice (Connell et al., 2004), although such differences appear to be region-specific (Restani et al., 1990). Females have higher densities of dopaminergic axons in the striatum prenatally compared with males (Ovtscharoff et al., 1992) as well as higher dopamine β-hydroxylase plasma levels (Koudelova and Mourek, 1990).

Cholinergic system

The cholinergic system in developing rats also exhibits sexually dimorphic features (lateralization of high affinity choline uptake, nicotine effects on KCC2 and brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)) in the rat hippocampus (Damborsky and Winzer-Serhan, 2012; Kristofikova et al., 2004). The participation and role of these factors in the pathogenesis of seizures and epilepsy is known. The role of the sex-specific features of excitatory systems on seizure outcomes needs further investigation.

Signaling pathways involved in epileptogenesis

Many pathways involved in the generation of seizures and epileptogenesis have been studied as to their sex specific influence. BDNF modulates synaptic transmission, neurogenesis, and promotes survival, neuronal growth and differentiation and has been proposed as an anti-epileptogenic treatment (Bovolenta et al., 2010). Interestingly, in the hippocampus, BDNF mRNA expression is higher in males than in females on PN5 but not on PN8 (Damborsky and Winzer-Serhan, 2012). BDNF may have age-specific effects on KCC2 expression and GABAAR inhibition. It decreases KCC2 in mature neurons, potentially switching GABAAR signaling to depolarizing, an effect that has been proposed to underlie the neuroprotective effects of BDNF, although it reduces the strength of GABAAR inhibition (Rivera et al., 2004; Shulga et al., 2008). Immature neurons however respond differently, since BDNF increases KCC2 expression and synaptogenesis (Aguado et al., 2003). The factors that control the way BDNF regulates KCC2 expression and GABAAR inhibition include the intracellular Cl− concentration and TrkB-activation of calcium-sensitive or insensitive pathways (Huang et al., 2012; Rivera et al., 2004). Given the interplay of BDNF with these intracellular pathways that do show sex-specific patterns of activity, it would be interesting to explore whether BDNF may mediate sex-specific effects of seizures.

Higher expression of Bcl-2 protein, an important factor in the regulation of neuronal cell death and survival of neurons, is reported in preoptic area of male rats (Hsu et al., 2000). Insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) receptor shows sex and laterality differences in an age-dependent manner in hippocampal CA1, CA3 and DG areas (Hami et al., 2013). There is no study known to us that demonstrates sex-specific effects of mTOR activation in the brain of developing animals, although sex-specific mTOR signaling has been reported in the cardiomyocytes of mice (Gurgen et al., 2013).

Morphological differences

Various morphological sex differences in brain attributes have been reported including the number of dendritic segments, the number of cells in certain brain regions, connectivity or volumetric differences. For example, dendritic branching is higher in the ventromedial nucleus of hypothalamus of the male rats during neonatal period (PN2). These differences are hormonally regulated and were abolished by treating female neonates with exogenous testosterone (Todd et al., 2007). In contrast, at PN25 the number of dendritic segments is greater in female than in male rats (Juraska, 1990). MRI studies in humans indicate that the volumes of amygdala and hippocampi exhibit significant age-related changes from infancy to early adulthood, and amygdala reach their peak volume earlier in females than in males (Uematsu et al., 2012).

Age-specific effects of early life seizures

Early life seizures can produce cell injury, metabolic disturbances, affect the developing and plastic neuronal circuitry or neurogenesis, change gene and protein expression and/or function, or lead to epileptogenesis but their effects are age dependent, and often their effects are distinct from seizures occurring in adulthood (Auvin et al., 2012; Ben-Ari and Holmes, 2006; Galanopoulou and Moshe, 2011; Kubova and Mares, 2013; Rakhade and Jensen, 2009; Sankar and Rho, 2007; Wasterlain et al., 2013). Multiple factors affect the outcomes, including the age at seizure induction, timepoint of outcome observation, cell type and brain region studied, model, duration or recurrence of seizures, the species or strain studied, or the environmental conditions. A major limitation however of these developmental studies is the difficulty in extrapolating the bioequivalency of the administered chemoconvulsant doses across ages, given the need to use different doses at age groups that differ substantially as to the type and degree of engagement of their downstream signaling targets.

SE in immature rodents, during the first two weeks of life, does not always induce cell loss or synaptic reorganization but the degree and pattern of injury and histopathological findings increase and change if SE is induced in older animals, in a model-specific manner (Albala et al., 1984; Galanopoulou, 2008a; Kubova et al., 2001; Raol et al., 2003; Sankar et al., 1998; Scholl et al., 2013; Sperber et al., 1991). Unlike adults, in two week old rats, kainic acid SE (KA-SE) or kindling seizures produce less KA-SE induced cell loss, no kindling cell loss, no synaptic reorganization or change in dentate gyrus (DG) inhibition (Haas et al., 2001; Sperber et al., 1991). Lithium–pilocarpine SE induced cell loss appears mostly at the CA1 region if SE is induced in 2 week old rats, but mostly in CA3, hilus and dentate granule cells in 3–4 week old rats (Sankar et al., 1998). The development of mossy fiber sprouting and spontaneous seizures was also more likely to occur when SE was induced at older ages (Haas et al., 2001; Roch et al., 2002; Sankar et al., 2000; Sperber et al., 1991). Nevertheless, histopathological changes may not be limited to the hippocampal region as extra-hippocampal areas appear to be injured and may contribute to both epileptogenesis and associated comorbidities (Galanopoulou and Moshe, 2009; Scholl et al., 2013).

Early life recurrent or prolonged seizures have been reported to either reduce or increase neurogenesis (McCabe et al., 2001; Nunes et al., 2000), whereas in adults seizures usually increase it (Parent et al., 1997; Scharfman et al., 2000). They may alter neurotransmitter signaling pathways in complex manners that may vary according to the downstream target, the cell type or brain region studied, the age at seizure induction or study of each endpoint, or the seizure model. Exposure to early life seizures changes the expression or the distribution of GABAARs (Briggs and Galanopoulou, 2011; Goodkin et al., 2008; Ni et al., 2005; Raol et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2004). For certain subunits, like the α1, SE can have opposite effects on their expression if induced in very young (PN10: increase in α1) or adult rats (decrease in α1) exposed to lithium-pilocarpine SE (Brooks-Kayal et al., 1998; Raol et al., 2006). Also, within the same animals subjected to lithium-pilocarpine SE on PN20, mature and immature DG neurons respond with different changes in the expression of glutamatergic receptors, suggesting that not only the chronological age but also the maturational state of the cell is important in defining outcomes (Porter et al., 2006). Single or repetitive flurothyl seizures may influence in the same way certain outcomes [e.g., number of GABAAR α1-ir or NMDA receptor (NR) NR2C-ir neurons] but not others (e.g., cell loss, glutamatergic or GABAergic responses) (Isaeva et al., 2006; Isaeva et al., 2010; Ni et al., 2005; Sogawa et al., 2001). KA-SE in immature rats has age-specific effects on glutamatergic receptors and GABAARs that are often opposite to those observed in adult rats (Friedman et al., 1994; Friedman et al., 1997). The effects of seizures on certain signaling pathways are also age-specific. Seizures can increase BDNF or FGF-2 in young animals, but this effect is more pronounced in older age groups (Kim et al., 2010; Kornblum et al., 1997; Talos et al., 2012b). It is therefore important to replicate specific findings to other seizure models as well as evaluate the overall functional impact of these changes to deduce whether these are impactful or compensated.

In contrast to adult rats, most of which develop epilepsy after SE, early life SE does not necessarily result in epilepsy (Galanopoulou and Moshe, 2011; Haas et al., 2001; Holmes et al., 2002; Moshe, 1993; Roch et al., 2002; Stafstrom et al., 1992). There is no report of adult epilepsy after SE induced in normal rats during the first week of life. Lithium-pilocarpine induced SE on PN12 or PN14 results in epilepsy in approximately 25% of rats, whereas 50–82% of rats develop spontaneous recurrent seizures in adulthood if SE is induced at PN21–25 (Kubova et al., 2004; Roch et al., 2002). A similar age-specific trend is observed when seizure susceptibility to induced seizures is being studied: the older the age at seizure induction is, the greater is its impact on lowering seizure threshold later in life. KA-SE in 2–3 week old rats does not change kindling susceptibility in adulthood (Okada et al., 1984) whereas PN27 rats exposed to KA-SE kindle faster than controls, 3 days later (Holmes and Thompson, 1988). Early exposure of PN10 male rats to lithium-pilocarpine induced SE does not alter the long-term susceptibility to seizures induced by GABAAR antagonists or kainic acid during adulthood (Nehlig et al., 2002). In contrast, adult rats exposed to lithium-pilocarpine SE had higher susceptibility to pentylenetetrazol during the latent phase (Rattka et al., 2011). However, again, model specific differences are observed.

Despite the milder pro-epileptogenic consequences of seizures in very young rats, compared to older age groups, normal rats subjected to single or repeated episodes of neonatal seizures may develop significant cognitive impairments during adolescence or adulthood (Cornejo et al., 2008; de Oliveira et al., 2008; Dube et al., 2009; Holmes et al., 1998; Sayin et al., 2004; Stafstrom, 2002). These include changes in learning and memory, behavioral abnormalities and emotional behavior, may occur both with repetitive brief seizures of SE and are reported to be more severe if SE is induced at older age groups (Huang et al., 1999; Karnam et al., 2009; Kubova et al., 2004; Sogawa et al., 2001). Interestingly, even a single episode of kainic acid induced seizures on PN7 impairs hippocampal-dependent working memory and this have been correlated with changes at the synaptic level such as reduction of GluR1 subunits and NR2A, impairments in long term potentiation (LTP) and enhancement of long-term depression (LTD) in the CA1 region of male rats (Cornejo et al., 2008; Cornejo et al., 2007).

Sex-specific consequences of early life seizures

Most of the above studies have included either males or animals of unspecified sex. Despite the different trajectories of brain maturation in males and females, to date, only few experimental studies have been designed to compare sex specific molecular or functional consequences of early life seizures, as will be discussed below (Table 3). In this review we will refer to induced models of seizures in immature rodents, as genetic models will be addressed elsewhere in this issue.

Table 3.

Consequences of early life seizures as a function of sex in induced rodent models of seizures.

| Endpoint | Model | Species, Region | Age at seizures | Observation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seizure susceptibility and induced mortality | Picrotoxin seizures | CBA/HZgr mice | PN20, 2.5–3 mo, 2 yrs |

Seizure occurrence,

mortality F=M: PN20, 2 yrs F<M: 2.5–3 mo |

(Manev et al., 1987) |

| Bicuculline seizures | CBA/HZgr mice | PN20, 2.5–3 mo, 2 yrs |

Seizure occurrence,

mortality F=M PN20, 2 yrs F<M: 2.5–3 mo: (mortality) |

(Manev et al., 1987) | |

| 3KA-SE | Sprague-Dawley Rat, CA1 | PN4–6 | F=M: Latency to seizure onset | (Galanopoulou, 2008a) | |

| Kindling (left CA1) | Sprague-Dawley Rat | PN14–15 | F=M: kindling parameters | (Young et al., 2006) | |

| DG Neurogenesis | Hyperthermic seizure | Sprague-Dawley Rat, DG | PN10 | F: no effect M: Increased survival of BrdU-positive DG cells by PN66; |

(Lemmens et al., 2005) |

| GABAergic system | 3KA-SE | Sprague-Dawley Rat, CA1 | PN4–6 | F: no change in KCC2; increased NKCC1

activity; EGABA : depolarizing shift 4 days post-SE

(transient) M: increased KCC2; decreased NKCC1 activity; EGABA : hyperpolarizing shift 4 days post-SE |

(Galanopoulou, 2008a) |

| 3KA-SE | Sprague-Dawley Rat, SNR | PN4–6 | M, F: increased KCC2; EGABA : hyperpolarizing shift | (Kyrozis et al., 2003) | |

| Domoic acid (unknown if seizures occurred) | Sprague-Dawley Rat, hippocampus | PN8–14 (daily inj) | M: reduced PRV counts in mid-DG and CA3;

reduced GAD counts in CA3 ventral (PN90) F: no change in PRV; reduced GAD in DG ventral (PN90) |

(Gill et al., 2010) | |

| Cholinergic system (Muscarinic receptors) | Pentylenetetr azole seizure | Sprague-Dawley rat, cortex (cingulate, parietal) and hippocampus | PN20 |

Controls

(adult): F<M: M1 receptor binding: (CA1) F<M: M3 mRNA F>M: [35S]GTPγS incorporation Early PTZ seizures (adult): F>M: [35S]GTPγS incorporation: (cingulate, parietal cortex) |

(Potier et al., 2005) |

| Other neurotransmitter systems | Domoic acid (unknown if seizures occurred) | Sprague-Dawley Rat, hippocampus | PN8–14 (daily inj) |

Adrenergic receptors

(adult): F: no change M: elevated α2A and α2C Mineralocorticoid receptors (MR, adult): F: no change M: elevated |

(Gill et al., 2012) |

| Estradiol neuroprotection | Kainic acid (unknown if seizures occurred) | Sprague-Dawley Rat, hippocampus | PN0–1 | F: estradiol protected from KA-induced

neuronal loss (PN7) M: no effect of estradiol |

(Hilton et al., 2003) |

| Gabapentin effects | Acute ischemic seizures | CD1 mice | PN12 | F<M: Seizure and injury reduction | (Traa et al., 2008) |

| Learning | 3KA-SE | Sprague-Dawley Rat | PN4–6 |

Barnes maze

(PN16–19)) F: no effect M: learning delay (PN16–19) |

(Akman et al., 2014) |

| Domoic acid (unknown if seizures occurred) | Sprague-Dawley Rat, hippocampus | PN8–14 (daily inj) |

Morris water maze or Water

H-maze (adult) M: delayed latencies F: no effect |

(Gill et al., 2012) | |

| Social behavior, anxiety | Pilocarpine | Wistar Rat | PN9 | M: less attack and defensive play behaviors than F | (Castelhano et al., 2010) |

| Locomotor activity | Pilocarpine | Wistar Rat | PN9 | F=M: reduced after PN30 | (Castelhano et al., 2010) |

| Hippocampal sclerosis | Intrahippocampal KA-SE | Sprague-Dawley Rat, hippocampus | PN10 | F=M: Hippocampal sclerosis (PN55) | (Dunleavy et al., 2010) |

| Subsequent seizure susceptibility | 3KA-SE | Sprague-Dawley Rat | PN4–6 | M, F: no change in flurothyl seizure thresholds (PN32) | (Akman et al., 2014) |

| Adult epilepsy | Two-hit model of MTLE | Sprague-Dawley Rat, | PN1: freeze-lesion; PN10: hyperthermic seizures | M: Epilepsy after PN90 F: No epilepsy |

(Desgent et al., 2012) |

Abbreviations: DG: dentate gyrus; GAD: glutamic acid decarboxylase; F: females; PN: post-natal; GABA: gamma-aminobutyric acid; KA-SE: kainic acid induced SE; KCC2: potassium/chloride co-transporter 2; M: males; M1 and M3: muscarinic receptors; MR: mineralocorticoid receptor; MTLE: mesial temporal lobe epilepsy (MTLE); NKCC1: sodium/potassium/chloride co-transporter 1; PRV: parvalbumin; SE: status epilepticus; TLE: temporal lobe epilepsy.

GABA signaling

Many reports indicate that seizures may alter GABAAR signaling in immature and mature periods. Following the report of depolarizing GABAAR responses in human epileptic subiculum (Cohen et al., 2002), multiple studies confirmed or extended these findings that suggest abnormal CCC expression and depolarizing GABAAR in human epileptic tissues (Aronica et al., 2007; Cepeda et al., 2007; Conti et al., 2011; Huberfeld et al., 2007; Jansen et al., 2010; Munakata et al., 2007; Munoz et al., 2007; Palma et al., 2006; Talos et al., 2012a). Several animal studies also indicated that seizures or the epileptic state in adult rodents may lead to re-appearance of depolarizing GABAAR due to either increase in NKCC1 or decrease in KCC2 activity (Benini and Avoli, 2006; Okabe et al., 2002; Okabe et al., 2003; Pathak et al., 2007; Rivera et al., 2002). Until recently, it had been unclear how GABAAR signaling is affected in immature animals exposed to seizures when these occur during the period when GABAARs are normally depolarizing. Of equal importance, do male and female neonatal pups respond in the same manner, given the known sexual dimorphism of GABAAR signaling? The only report demonstrating abnormal switch to depolarizing GABAAR as a result of seizures in immature neurons was in PN6–7 male Wistar rat hippocampi induced to generate spontaneous seizures in vitro, using the mirror focus formation method (Khalilov et al., 2003). However, in this study, PN6–7 seizure-naïve hippocampal CA3 pyramidal neurons had isoelectric or mildly hyperpolarizing reversal potentials, rather than depolarizing, as seen in neonatal neurons.

In our lab, we evaluated the effects of early life kainic acid induced SE on GABAAR signaling of CA1 rat pyramidal neurons during the first week of life, when GABAARs elicit depolarizing responses in males and isoelectric or hyperpolarizing responses in females (Galanopoulou, 2008a). This allowed us to study the effects of seizures on neonatal male and female rats of the same chronological age (PN4–6) but with distinct modes of GABAAR responses, given their known sex differences. After inducing 3 episodes of kainic acid status epilepticus (3KA-SE) at PN4–6, we determined the reversal potential of GABAAR responses (EGABA) in CA1 pyramidal neurons during the subsequent 2 weeks, using gramicidin-perforated patch clamp. In males that had depolarizing EGABA at the time of 3KA-SE(PN4–6) induction, seizures caused a precocious appearance of hyperpolarizing EGABA, 4 days earlier than expected. In contrast, in females that had isoelectric or hyperpolarizing EGABA at the time of 3KA-SE(PN4–6), a transient re-emergence of depolarizing EGABA was observed between PN8–13, but this was not persistent. Interestingly, GABAAR blockade with bicuculline during 3KA-SE reversed the effects of 3KA-SE on EGABA, suggesting that the effects of seizures on EGABA are GABAAR mediated. The 3KA-SE induced changes in EGABA also correlated with altered activity of KCC2 and NKCC1.

We have also extended these findings to the SNR. Both male and female SNR GABAergic neurons have depolarizing EGABA at the time of 3KA-SE(PN4–6) induction (Kyrozis et al., 2006). Similar to our observations in the male hippocampus, seizures also accelerated the appearance of hyperpolarizing GABAAR responses in GABAergic SNR neurons and abolished the muscimol-induced intracellular calcium rises that are normally observed at that age (Kyrozis et al., 2003). Both our hippocampal and SNR studies support that neonatal seizures tend to reverse the polarity of GABAAR responses in developing neurons, during the days following seizure exposure, in a manner that depends upon their EGABA at the time of seizure induction.

These 3KA-SE induced changes in EGABA and CCCs are distinct from those induced simply by the separation stress of the animals, which tends to cause hyperpolarizing shifts in both males and females (Galanopoulou, 2008a). If indeed depolarizing GABAAR signaling is associated with the epileptic state, it would be tempting to hypothesize that the inability of neonatal 3KA-SE to cause persistent appearance of depolarizing GABAAR could potentially contribute to the low pro-epileptogenic diathesis of newborn rats.

To address whether the disruption of EGABA might also affect the related developmental processes that control seizure susceptibility, we looked at the effects of early life 3KA-SE upon the muscimol-sensitive anticonvulsant function of the anterior SNR and on the susceptibility to flurothyl seizures. For more details on the seizure control function of the SNR please see (Giorgi et al., 2014). Interestingly, 3KA-SE also disrupted the muscimol-sensitive anticonvulsant function of the anterior SNR in males, when it was induced during the developmental period of depolarizing GABAAR signaling in GABAergic SNR neurons (3KA-SE(PN4–6)) but not after the time of EGABA shift (3KA-SE(PN14–16)) (unpublished data). However, neither 3KA-SE(PN4–6) nor 3KA-SE(PN14–16) affected flurothyl seizure thresholds in PN32 male rats, in the absence of intranigral muscimol infusions, suggesting that other compensatory factors overcame the impaired seizure-controlling function of the SNR (Akman et al., 2014). In line with the hypothesis that the early termination of depolarizing GABAAR signaling may produce developmental abnormalities, we recently found learning delay in male rats exposed to 3KA-SE at PN 4–6 but not in females (Akman et al., 2014).

Overall, these observations suggest that neonatal seizures may impact on the GABAAR-sensitive brain development, including its sexually dimorphic features, and that their effects appear to be region, network, and sex-specific. However, complex age-, sex-, and network-specific homeostatic mechanisms may compensate for or aggravate some of the anticipated deficits.

Neurogenesis

Neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of young rats may be influenced by sex hormones (Ormerod et al., 2003), hence shows differences between males and females. PN17 or 4 week old male rats exhibit more newborn neurons in the dentate than same age females, yet their survival is better in females (Lemmens et al., 2005; Perfilieva et al., 2001). Exposure to 30-min hyperthermic seizures on PN10 improves survival of newborn DG neurons in males till PN66, but had no effect in females (Lemmens et al., 2005). It would also be important to investigate how neonatal exposure to seizures may differentially affect neoneurogenesis in the DG, given the prior studies that indicate reduction of newborn cells after neonatal flurothyl seizures (McCabe et al., 2001). In addition, investigation as to how environmental or nutritional factors, or life experiences may alter the effects of early life seizures on DG neurogenesis, as a function of age and sex, is also warranted, given the evidence that malnutrition increases seizure-induced neurogenesis after PN15 flurothyl seizures (Nunes et al., 2000). Although seizure-induced neoneurogenesis has been associated with either epileptogenesis or cognitive dysfunction, a clear causative link with the ensuing epileptogenesis or associated comorbidities has not been established. Future research into the mechanisms involved in seizure-induced neoneurogenesis and how age and sex-specific factors control this process will be needed.

Histological changes

Sex-specific differences in the pattern of seizure-induced injury in adult rats have been described and could potentially reflect differences in hormonal milieu (Galanopoulou et al., 2003a). There are no studies, known to us, documenting sex-specific seizure-induced injury shortly after early life induced seizures, although this has not been systematically pursued. Intrahippocampal injection of kainic acid to induce seizures in PN10 rats caused hippocampal sclerosis in both sexes by PN55, without any discernible sex differences (Dunleavy et al., 2010). In contrast, daily administration of low doses of domoic acid in PN8–14 rats, reduced parvalbumin (PRV) and GAD positive cells in a sex and region specific manner in the adult hippocampus (Gill et al., 2010). Although domoic acid is a structural analog of kainic acid, it is unclear if, in this study, seizures had occurred and might have contributed to the observed findings. However, it still warns that potential chemoconvulsants may have sex-specific effects on the observed pathology.

Sex-specific factors could potentially interfere with the neuroprotective effects of tested drugs. For example, gabapentin reduced injury and seizures in PN12 CD1 mice subjected to acute ischemic seizures (Traa et al., 2008). A study on the apoptosis induced by anticonvulsant drugs (lamotrigine alone or in combination with phenobarbital or phenytoin) in seizure-naïve neonatal male and female PN7 rats did not report any sex differences in apoptosis (Katz et al., 2007). Administration of estradiol in PN0–1 rats that had been given kainic acid, prevented hippocampal neuronal loss by PN7 in females but not in males (Hilton et al., 2003). Neonatal Wistar female rats subjected to cortical freezing to induce microgyria had less pronounced neuropathology in the medial geniculate nucleus compared to males or androgenized females (testosterone-treated), suggesting again the gonadal hormones may modify the expected histopathological outcomes in certain procedures utilized in epilepsy research (Rosen et al., 1999). The interplay of gonadal hormones with many neurotransmitter systems and the fact that during development, and particular the neonatal period, steroid hormones may play critical role in the neuronal survival and differentiation (see (Giorgi et al., 2014)) emphasize the importance of accounting for sex-related factors when looking at seizure outcomes.

Behavioral tests

Overall, males appear to be more vulnerable to subsequent behavioral comorbidities than females when exposed to early life seizures. Castelhano et al (2010) reported that a single episode of pilocarpine-induced SE at PN9 produces social impairment in males but not in females after PN30 (Castelhano et al., 2010). In contrast, early life SE enhanced self-grooming only in females. Using the 3KA-SE model in PN4–6 rats, we observed selective learning delay in males but not in females at the Barnes maze test performed between PN16–19 (Akman et al., 2014). Reduced susceptibility to short-term social-memory deficits induced by neonatal freezing model of microgyria was observed in female mice in adulthood, compared to males (Rial et al., 2009). Daily administration of domoic acid in PN8–14 rats (uncertain if seizures were induced) impaired Morris water maze and water H-maze performance in males but not in females during adulthood (Gill et al., 2012).

Seizure susceptibility, mortality, epileptogenesis in induced models of seizures

Review of the literature did not reveal any sex-specific differences in seizure susceptibility or resultant mortality in immature rats acutely induced to develop seizures (see Table 2), although such reports are present in adult animals (Galanopoulou, 2008a; Manev et al., 1987; Young et al., 2006). In rats with prior experience of 3KA-SE (PN4–6) no change in flurothyl seizure threshold on PN32 was observed, even if prior alterations in GABAergic system and GABA-sensitive seizure controling networks had been documented (Akman et al., 2014). These may indicate that in spite of known sex differences in the expression or function of specific neurotransmitter systems, these may be (a) either compensated by other homeostatic mechanisms or (b) overridden by the strong proconvulsant effects of exogenous seizure-inducing methods.

In contrast, a recent study by Desgent and coworkers (2012) reported sexual dimorphism in the long-term vulnerability to develop spontaneous recurrent seizures (epileptogenesis) in the two-hit model of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy (MTLE). In this model, a cortical malformation induced at PN1 with freeze-lesioning of the cortex leads to enhanced susceptibility to a second insult, the hyperthermic seizure (HS), at PN10. Male or androgenized (with prenatal testosterone) female but not female rats with initial cortical malformation displayed spontaneous recurrent seizures after experiencing hyperthermic seizures at PN10. This correlated with a rise in corticosterone levels following the lesion at PN1 in male or androgenized female rats only. Cortical lesion volumes in adulthood were similar between male and female adult rats (Desgent et al., 2012).

Conclusions

There is solid evidence in support of the sexual dimorphism of the brain, including regions and networks that control seizures. The current evidence strongly suggests potent and age-dependent effects of early life seizures on the developing brain at cellular and network levels, including neurotransmitter signaling pathways, neuronal proliferation, differentiation and connectivity, long-term behavioral or epilepsy outcomes. Despite the differences of brain maturation in males and females, to date, the sex specific molecular or functional consequences of early life seizures have not been fully elucidated, largely because most of the available studies have been done in males or rodents of unclear sex specification or because the low sample sizes and variability in outcomes in animal studies may not allow the detection of certain sex differences. Among the studies that have addressed sex differences in the consequences of early life seizures, a number of outcomes have shown statistical significance, including: molecular or functional alterations in certain neurotransmitter systems (e.g., GABAAR, cholinergic), survival of newborn DG cells, injury induced by seizures or their induction methods, neuroprotective effects of selected drugs (e.g., gabapentin) or hormones (e.g., gonadal hormones), long-term behavioral or epilepsy outcomes. A variety of factors have been implicated in the expression of sex-specific outcomes, including but not limited to GABAAR signaling, growth factor signaling, gonadal hormones, network differences, although more needs to be known. In contrast, there is also sufficient evidence that in many cases, and despite documented sex-specific abnormalities, subsequent pathology or seizure susceptibility may be unaltered, emphasizing the importance and power of homeostatic mechanisms that may overcome these deficits. However, even if this is the case, gender-focused research into the mechanisms of epileptogenesis will be necessary in the identification of gender-appropriate therapies that will minimize side effects and improve patient care and quality of life.

Highlights.

The sexual dimorphism of the brain is present very early in life

The substantia nigra and hippocampus are sexually dimorphic

Early life seizures may have age- and sex-specific consequences.

GABAA receptors mediate sex-specific effects of neonatal seizures

More studies are needed to elucidate the sex-specific effects of seizures

Acknowledgements

ASG acknowledges research grant funding from: NINDS (NS078333), CURE, Autism Speaks, Department of Defense, and the Heffer Family and Siegel Family Foundations. ASG has received royalties from Morgan & Claypool Publishers and John Libbey Eurotext Ltd, and consultancy honorarium from Viropharma. SLM received grants from NINDS (NS020253, NS043209, NS045911, NS078333), Department of Defense, CURE, the Heffer Family and Siegel Family Foundations, and consultancy honorarium from Lundbeck and UCB Pharma.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Aguado F, Carmona MA, Pozas E, Aguilo A, Martinez-Guijarro FJ, Alcantara S, et al. “BDNF regulates spontaneous correlated activity at early developmental stages by increasing synaptogenesis and expression of the K+/Cl− co-transporter KCC2.” Development 2003; 130: 1267–1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aicardi J Chevrie JJ. “Convulsive status epilepticus in infants and children. A study of 239 cases.” Epilepsia 1970; 11: 187–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akman O, Moshé SL Galanopoulou AS. “Effects of recurrent neonatal status epilepticus and stress on learning and the anticonvulsant phenobarbital effects.” Epielpsy Currents 2014; 14: 101–102. [Google Scholar]

- Albala BJ, Moshe SL Okada R. “Kainic-acid-induced seizures: a developmental study.” Brain Res 1984; 315: 139–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annegers JF, Hauser WA, Lee JR Rocca WA. “Incidence of acute symptomatic seizures in Rochester, Minnesota, 1935–1984.” Epilepsia 1995; 36: 327–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronica E, Boer K, Redeker S, Spliet WG, van Rijen PC, Troost D, et al. “Differential expression patterns of chloride transporters, Na+-K+−2Cl−-cotransporter and K+-Cl−-cotransporter, in epilepsy-associated malformations of cortical development.” Neuroscience 2007; 145: 185–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asadi-Pooya AA, Emami M Sperling MR. “Age of onset in idiopathic (genetic) generalized epilepsies: clinical and EEG findings in various age groups.” Seizure 2012; 21: 417–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auger AP, Hexter DP McCarthy MM. “Sex difference in the phosphorylation of cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) in neonatal rat brain.” Brain Res 2001; 890: 110–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auger AP Olesen KM. “Brain sex differences and the organisation of juvenile social play behaviour.” J Neuroendocrinol 2009; 21: 519–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auvin S, Pineda E, Shin D, Gressens P Mazarati A. “Novel animal models of pediatric epilepsy.” Neurotherapeutics 2012; 9: 245–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avishai-Eliner S, Brunson KL, Sandman CA Baram TZ. “Stressed-out, or in (utero)?” Trends Neurosci 2002; 25: 518–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y “Excitatory actions of gaba during development: the nature of the nurture.” Nat Rev Neurosci 2002; 3: 728–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y Holmes GL. “Effects of seizures on developmental processes in the immature brain.” The Lancet Neurology 2006; 5: 1055–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benarroch EE. “NMDA receptors: recent insights and clinical correlations.” Neurology 2011; 76: 1750–1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benini R Avoli M “Altered inhibition in lateral amygdala networks in a rat model of temporal lobe epilepsy.” J Neurophysiol 2006; 95: 2143–2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian C, Zhu K, Guo Q, Xiong Y, Cai W Zhang J. “Sex differences and synchronous development of steroid receptor coactivator-1 and synaptic proteins in the hippocampus of postnatal female and male C57BL/6 mice.” Steroids 2012; 77: 149–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi M, Rey-Roldan E, Bettler B, Ristig D, Malitschek B, Libertun C, et al. “Ontogenic expression of anterior pituitary GABA(B) receptor subunits.” Neuropharmacology 2001; 40: 185–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi MS, Lux-Lantos VA, Bettler B Libertun C. “Expression of gamma-aminobutyric acid B receptor subunits in hypothalamus of male and female developing rats.” Brain Res Dev Brain Res 2005; 160: 124–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovolenta R, Zucchini S, Paradiso B, Rodi D, Merigo F, Navarro Mora G, et al. “Hippocampal FGF-2 and BDNF overexpression attenuates epileptogenesis-associated neuroinflammation and reduces spontaneous recurrent seizures.” J Neuroinflammation 2010; 7: 81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs SW Galanopoulou AS. “Altered GABA signaling in early life epilepsies.” Neural Plast 2011; 2011: 527605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Kayal AR, Shumate MD, Jin H, Rikhter TY Coulter DA. “Selective changes in single cell GABA(A) receptor subunit expression and function in temporal lobe epilepsy.” Nat Med 1998; 4: 1166–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunquell PJ, Glennon CM, DiMario FJ Jr., Lerer T Eisenfeld L. “Prediction of outcome based on clinical seizure type in newborn infants.” J Pediatr 2002; 140: 707–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancedda L, Fiumelli H, Chen K Poo MM. “Excitatory GABA action is essential for morphological maturation of cortical neurons in vivo.” J Neurosci 2007; 27: 5224–5235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castelhano AS, Scorza FA, Teixeira MC, Arida RM, Cavalheiro EA Cysneiros RM. “Social play impairment following status epilepticus during early development.” J Neural Transm 2010; 117: 1155–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepeda C, Andre VM, Wu N, Yamazaki I, Uzgil B, Vinters HV, et al. “Immature neurons and GABA networks may contribute to epileptogenesis in pediatric cortical dysplasia.” Epilepsia 2007; 48 Suppl 5: 79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang LR, Liu JP, Zhang N, Wang YJ, Gao XL Wu Y. “Different expression of NR2B and PSD-95 in rat hippocampal subregions during postnatal development.” Microsc Res Tech 2009; 72: 517–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman KE, Raol YH Brooks-Kayal A. “Neonatal seizures: controversies and challenges in translating new therapies from the lab to the isolette.” Eur J Neurosci 2012; 35: 1857–1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chudomel O, Herman H, Nair K, Moshe SL Galanopoulou AS. “Age- and gender-related differences in GABAA receptor-mediated postsynaptic currents in GABAergic neurons of the substantia nigra reticulata in the rat.” Neuroscience 2009; 163: 155–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen I, Navarro V, Clemenceau S, Baulac M Miles R. “On the origin of interictal activity in human temporal lobe epilepsy in vitro.” Science 2002; 298: 1418–1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell S, Karikari C Hohmann CF. “Sex-specific development of cortical monoamine levels in mouse.” Brain Res Dev Brain Res 2004; 151: 187–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti L, Palma E, Roseti C, Lauro C, Cipriani R, de Groot M, et al. “Anomalous levels of Cl− transporters cause a decrease of GABAergic inhibition in human peritumoral epileptic cortex.” Epilepsia 2011; 52: 1635–1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornejo BJ, Mesches MH Benke TA. “A single early-life seizure impairs short-term memory but does not alter spatial learning, recognition memory, or anxiety.” Epilepsy Behav 2008; 13: 585–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornejo BJ, Mesches MH, Coultrap S, Browning MD Benke TA. “A single episode of neonatal seizures permanently alters glutamatergic synapses.” Ann Neurol 2007; 61: 411–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damborsky JC Winzer-Serhan UH. “Effects of sex and chronic neonatal nicotine treatment on Na(2)(+)/K(+)/Cl(−) co-transporter 1, K(+)/Cl(−) co-transporter 2, brain-derived neurotrophic factor, NMDA receptor subunit 2A and NMDA receptor subunit 2B mRNA expression in the postnatal rat hippocampus.” Neuroscience 2012; 225: 105–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis AM, Grattan DR, Selmanoff M McCarthy MM. “Sex differences in glutamic acid decarboxylase mRNA in neonatal rat brain: implications for sexual differentiation.” Horm Behav 1996; 30: 538–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira DL, Fischer A, Jorge RS, da Silva MC, Leite M, Goncalves CA, et al. “Effects of early-life LiCl− pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus on memory and anxiety in adult rats are associated with mossy fiber sprouting and elevated CSF S100B protein.” Epilepsia 2008; 49: 842–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desgent S, Duss S, Sanon NT, Lema P, Levesque M, Hebert D, et al. “Early-life stress is associated with gender-based vulnerability to epileptogenesis in rat pups.” PLoS One 2012; 7: e42622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diano S, Naftolin F Horvath TL. “Gonadal steroids target AMPA glutamate receptor-containing neurons in the rat hypothalamus, septum and amygdala: a morphological and biochemical study.” Endocrinology 1997; 138: 778–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbing J Sands J “Comparative aspects of the brain growth spurt.” Early Hum Dev 1979; 3: 79–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube CM, Zhou JL, Hamamura M, Zhao Q, Ring A, Abrahams J, et al. “Cognitive dysfunction after experimental febrile seizures.” Exp Neurol 2009; 215: 167–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunleavy M, Shinoda S, Schindler C, Ewart C, Dolan R, Gobbo OL, et al. “Experimental neonatal status epilepticus and the development of temporal lobe epilepsy with unilateral hippocampal sclerosis.” Am J Pathol 2010; 176: 330–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrant M Kaila K “The cellular, molecular and ionic basis of GABA(A) receptor signalling.” Prog Brain Res 2007; 160: 59–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman L Hu S “Early-life seizures in predisposing neuronal preconditioning: a critical review.” Life Sci 2014; 94: 92–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman LK, Pellegrini-Giampietro DE, Sperber EF, Bennett MV, Moshe SL Zukin RS. “Kainate-induced status epilepticus alters glutamate and GABAA receptor gene expression in adult rat hippocampus: an in situ hybridization study.” J Neurosci 1994; 14: 2697–2707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman LK, Sperber EF, Moshe SL, Bennett MV Zukin RS. “Developmental regulation of glutamate and GABA(A) receptor gene expression in rat hippocampus following kainate-induced status epilepticus.” Dev Neurosci 1997; 19: 529–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanopoulou A “Sex-specific KCC2 expression and GABAA receptor function in rat substantia nigra.” Experimental Neurology 2003; 183: 628–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanopoulou AS. “Sex- and cell-type-specific patterns of GABAA receptor and estradiol-mediated signaling in the immature rat substantia nigra.” Eur J Neurosci 2006; 23: 2423–2430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanopoulou AS. “Dissociated gender-specific effects of recurrent seizures on GABA signaling in CA1 pyramidal neurons: role of GABA(A) receptors.” J Neurosci 2008a; 28: 1557–1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanopoulou AS. “GABA(A) receptors in normal development and seizures: friends or foes?” Curr Neuropharmacol 2008b; 6: 1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanopoulou AS. “Sexually dimorphic expression of KCC2 and GABA function.” Epilepsy Res 2008c; 80: 99–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanopoulou AS, Alm EM Veliskova J. “Estradiol reduces seizure-induced hippocampal injury in ovariectomized female but not in male rats.” Neurosci Lett 2003a; 342: 201–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanopoulou AS, Bojko A, Lado F Moshe SL. “The spectrum of neuropsychiatric abnormalities associated with electrical status epilepticus in sleep.” Brain Dev 2000; 22: 279–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanopoulou AS, Kyrozis A, Claudio OI, Stanton PK Moshe SL. “Sex-specific KCC2 expression and GABA(A) receptor function in rat substantia nigra.” Exp Neurol 2003b; 183: 628–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanopoulou AS, Liptakova S, Veliskova J Moshé SL. “Sex and regional differences in the time and patterns of neurogenesis of the rat substantia nigra.” Epilepsia 2001; 42: 109. [Google Scholar]

- Galanopoulou AS Moshe SL. “Role of sex hormones in the sexually dimorphic expression of KCC2 in rat substantia nigra.” Exp Neurol 2003; 184: 1003–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanopoulou AS Moshe SL. “The epileptic hypothesis: developmentally related arguments based on animal models.” Epilepsia 2009; 50 Suppl 7: 37–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanopoulou AS Moshe SL. “In search of epilepsy biomarkers in the immature brain: goals, challenges and strategies.” Biomark Med 2011; 5: 615–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanopoulou AS, Vidaurre J Moshe SL. “Under what circumstances can seizures produce hippocampal injury: evidence for age-specific effects.” Dev Neurosci 2002; 24: 355–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill DA, Perry MA, McGuire EP, Perez-Gomez A Tasker RA. “Low-dose neonatal domoic acid causes persistent changes in behavioural and molecular indicators of stress response in rats.” Behav Brain Res 2012; 230: 409–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill DA, Ramsay SL Tasker RA. “Selective reductions in subpopulations of GABAergic neurons in a developmental rat model of epilepsy.” Brain Res 2010; 1331: 114–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi FS, Galanopoulou AS Moshé SL. “Sex dimorphism in seizure-controlling networks.” Neurobiology of Disease 2014: this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodkin HP, Joshi S, Mtchedlishvili Z, Brar J Kapur J. “Subunit-specific trafficking of GABA(A) receptors during status epilepticus.” J Neurosci 2008; 28: 2527–2538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb A, Keydar I Epstein HT. “Rodent brain growth stages: an analytical review.” Biol Neonate 1977; 32: 166–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurgen D, Kusch A, Klewitz R, Hoff U, Catar R, Hegner B, et al. “Sex-specific mTOR signaling determines sexual dimorphism in myocardial adaptation in normotensive DOCA-salt model.” Hypertension 2013; 61: 730–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas KZ, Sperber EF, Opanashuk LA, Stanton PK Moshe SL. “Resistance of immature hippocampus to morphologic and physiologic alterations following status epilepticus or kindling.” Hippocampus 2001; 11: 615–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hami J, Kheradmand H Haghir H. “Gender Differences and Lateralization in the Distribution Pattern of Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 Receptor in Developing Rat Hippocampus: An Immunohistochemical Study.” Cell Mol Neurobiol 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser WA, Annegers JF Kurland LT. “Incidence of epilepsy and unprovoked seizures in Rochester, Minnesota: 1935–1984.” Epilepsia 1993; 34: 453–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesdorffer DC, Shinnar S, Lewis DV, Nordli DR Jr., Pellock JM, Moshe SL, et al. “Risk factors for febrile status epilepticus: a case-control study.” J Pediatr 2013; 163: 1147–1151 e1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton GD, Nunez JL McCarthy MM. “Sex differences in response to kainic acid and estradiol in the hippocampus of newborn rats.” Neuroscience 2003; 116: 383–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes GL. “Effects of seizures on brain development: lessons from the laboratory.” Pediatr Neurol 2005; 33: 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes GL. “The long-term effects of neonatal seizures.” Clin Perinatol 2009; 36: 901–914, vii–viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes GL, Gairsa JL, Chevassus-Au-Louis N Ben-Ari Y. “Consequences of neonatal seizures in the rat: morphological and behavioral effects.” Ann Neurol 1998; 44: 845–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes GL, Khazipov R Ben-Ari Y. “New concepts in neonatal seizures.” Neuroreport 2002; 13: A3–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes GL Thompson JL. “Effects of kainic acid on seizure susceptibility in the developing brain.” Brain Res 1988; 467: 51–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu C, Hsieh YL, Yang RC Hsu HK. “Blockage of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors decreases testosterone levels and enhances postnatal neuronal apoptosis in the preoptic area of male rats.” Neuroendocrinology 2000; 71: 301–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CC, Chang YC Wang ST. “Acute symptomatic seizure disorders in young children--a population study in southern Taiwan.” Epilepsia 1998; 39: 960–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Cilio MR, Silveira DC, McCabe BK, Sogawa Y, Stafstrom CE, et al. “Long-term effects of neonatal seizures: a behavioral, electrophysiological, and histological study.” Brain Res Dev Brain Res 1999; 118: 99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]