Abstract

Purpose

Overexpression and activation of SRC has been linked to breast carcinogenesis and bone metastases. We demonstrated the feasibility of combining the SRC inhibitor dasatinib with weekly paclitaxel in metastatic breast cancer (MBC) and here report the subsequent phase II trial.

Patients

Patients had received ≤2 chemotherapy regimens for measurable, HER2 negative MBC. Patients received paclitaxel and dasatinib (120mg daily) and were assessed by RECIST for overall response rate (ORR), the primary endpoint. Secondary endpoints included PFS and OS. A 30% ORR (n=55) was deemed worthy of further investigation. Exploratory biomarkers included N-telopeptide (NTX) and plasma VEGFR2 as predictors of clinical benefit.

Results

From March 2010 to March 2014, 40 patients, including 2 men enrolled. The study was stopped early due to slow accrual. Overall, 32 (80%) patients had ER positive tumors and 23 (58 %) had previous taxanes. Of the 35 assessable patients assessable, 1 (3%) had CR and 7 (20%) PR, resulting in an ORR of 23%. The median PFS and OS was 5.2 (95% CI 2.9-9.9) and 20.6 (95% CI 12.9-25.2) months respectively. As expected, fatigue (75%), neuropathy (65%) and diarrhea (50%) were common side-effects, but were generally low grade. Median baseline NTX was similar in patients who had clinical benefit (8.2) and no clinical benefit (10.9). Similarly, median baseline VEGF levels were similar between the two groups; 93.0 vs 83.0.

Conclusion

This phase II study of dasatinib and paclitaxel was stopped early due to slow accrual but showed some clinical activity. Further study is not planned.

Keywords: Dasatinib, Paclitaxel, Advanced Breast Cancer, SRC, Phase II

Microabstract

Overexpression and activation of SRC has been linked to breast carcinogenesis and bone metastases. We conducted a phase II trial inHER2 negative metastatic breast cancer of weekly paclitaxel and the SRC inhibitor dasatinib (120mg daily). The primary endpoint was response by RECIST and secondary endpoints included PFS and OS. We enrolled 40 patients, including 2 men, but the study was stopped early due to slow accrual. The overall response rate was of 23%. The median PFS and OS was 5.2 (95% CI 2.9-9.9) and 20.6 (95% CI 12.9-25.2) months respectively. Toxicities were as expected and included fatigue, neuropathy and diarrhea. We were unable to find any predictive biomarker of treatment benefit.

Introduction

Overexpression and activation of Src, a membrane associated nonreceptor tyrosine kinase has been linked to breast carcinogenesis 1-4. SRC Kinases enhance metastatic growth and survival of breast cells in the bone marrow microenvironment 5, 6. In addition, Src kinases play a part in the activation of osteoclasts, contributing to the development of late-onset bone metastases 5, 6. Osseous metastases are a common occurrence, affecting up to 70% of patients with metastatic breast cancer (MBC) 7, 8. Hence it is hypothesized that inhibitors of Src might have a role in the treatment of MBC, and might be of particular interest in patients with bone metastases. To date, many breast cancer targeted therapies have focused on the estrogen receptor (ER), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), although bone -modifying agents such as bisphosphonates, and RANK ligand inhibitors have improved the outcome for patients with bone metastases irrespective of breast cancer phenotype 9, 10. Because of its importance to many patients with breast cancer and the possible role in treating breast cancer bone metastases, we were particularly interested in targeting SRC as a therapeutic approach.

Dasatinib is an ATP-competitive inhibitor, which inhibits several tyrosine kinases, including members of the SRC family 11. This oral agent is approved by the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) for chronic myelogenous leukemia and has been studied in various solid tumors 12. Preclinical studies have shown that dasatinib inhibits the growth of cells that express activated SRC, and has particular activity in triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) that lacks expression of ER, progesterone receptor (PR) and HER2 13-15. Dasatinib has limited clinical activity as a single agent in breast cancer, but might have greater antitumor activity in combination with other agents 16. Preclinically, the combination of dasatinib and paclitaxel, a highly active cytotoxic with non-overlapping toxicity profile, showed greater antitumor activity than either single agent 17. We previously conducted a phase I study and demonstrated that the combination of weekly paclitaxel (80mg/m2) and dasatinib (120 mg orally) was feasible 18. Here we report the results of the subsequent phase II study of this combination in MBC.

Patients and Methods

Patients with HER2 negative locally advanced or MBC, irrespective of ER status were eligible. All patients were required to have measurable disease per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST), performance status of 0 or 1 (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group scale) and normal organ function (haematologic, renal and hepatic) 19. Up to two prior chemotherapy regimens for metastatic disease were permitted. Exclusion criteria included prior severe allergic reactions to paclitaxel, symptomatic central nervous system (CNS) metastases, pre-existing neuropathy (grade >1) and uncontrolled gastrointestinal malabsorption syndromes. Due to the risk of fluid retention with dasatinib, patients with symptomatic pleural effusion were not permitted to participate. Patients were not permitted to take potent CYP34A inhibitors or agents associated with QT-prolongation. Women of childbearing potential were required to use adequate contraception. All patients were required to have a paraffin-embedded tissue block or unstained slides available for correlative biomarker research.

Study design

This study was designed as a Ib-II open label trial and the results of the phase I study have been reported separately 18. For the phase II trial paclitaxel (80mg/m2) was given intravenously over 1 hour on days 1,8 and 15 of a 28 day cycle and dasatinib 120mg was given orally in a single-daily dose as recommended from the phase I portion 18. Paclitaxel and dasatinib doses were adjusted for toxicity and treatment could be delayed for no more than three weeks due to toxicity. Treatment was continued until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity or consent withdrawal. Due to the risk of hypocalcaemia with dasatinib therapy, patients were not permitted to receive bone targeting agents for the first 8 weeks of treatment. Patients were assessed every four weeks for adverse events and RECIST assessment was performed after the first two cycles of treatment and every three cycles thereafter.

The primary endpoint was overall response rate (ORR), defined, according to RECIST criteria as the percentage of patients achieving either an objective complete response (CR) or a partial response (PR) 19. Based on prior single agent response rates for paclitaxel, a 15% response rate was chosen for futility and 30% for the combination to be deemed worthy of further investigation 20. The phase II portion of the study used a Simon two-stage optimal design with Type I and II errors set at 0.10: if responses were seen in ≥4/23 (17.4%) patients, enrollment was extended to a total of 55 patients. Using this design if 12/55 patients had an ORR, then the study would be considered to have a positive result and this regimen would be considered worthy of further testing. Based on these hypotheses, the probability of early termination was 54% if the true ORR was ≤ 15%. Secondary end points included: clinical benefit (the sum of the percentage of patients who achieved CR, PR and stable disease (SD) for greater than 6 months), time to tumor progression (TTP), progression free survival (PFS) and, safety and tolerability of the combination. We also explored the activity of the combination in patients with bone metastases. Exploratory tumor biomarkers included Collagen Type IV (or N-telopeptide, NTX) plasma vascular epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) and circulating tumor cells (CTCs) obtained at baseline and after two cycles of treatment and correlated with clinical benefit. For CTCs, samples were processed as previously described using the CellSearch system.

Results

From March 2010 to March 2014, 40 patients, including 2 men, were enrolled (table 1). In total 32 (80%) patients had ER positive, HER2 negative tumors and 8 (20%) had TNBC. The commonest site of metastases was bone (60%) and most (73%) patients had visceral disease. Patients were generally quite heavily pre-treated: 55% had received 1 or more lines of hormone therapy and 65% had received at least 1 line of chemotherapy for advanced disease. Of note, 23 (58 %) had previously been treated with a previous taxane, either for early (N=20) or advanced (N =3) breast cancer.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| All Patients (N=40) |

Clinical Benefit (N=15) |

No Clinical Benefit (N=20) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Age (years); median (range) | 52 (30 – 79) | 55 (37–79) | 47 (35–61) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 38 (95) | 13 (87) | 20 (100) |

| Male | 2 (5) | 2 (13) | 0 (0) |

| Race | |||

| White | 29 (73) | 13 (87) | 12 (60) |

| Black | 5 (13) | 1 (7) | 4 (20) |

| Other | 6 (15) | 1 (7) | 4 (20) |

| Histology | |||

| ER positive | 32 (80) | 14 (93) | 14 (70) |

| Triple negative | 8 (2) | 1 (7) | 6 (30) |

| Site of metastases | |||

| Bone | 27 (68) | 11 (73) | 13 (65) |

| Liver | 25 (63) | 9 (60) | 13 (65) |

| Lymph Nodes | 18 (45) | 4 (27) | 14 (70) |

| Lung | 11 (28) | 2 (13) | 9 (45) |

| Skin / Soft Tissue | 7 (18) | 2 (13) | 3 (15) |

| Brain | 2 (5) | 0 | 1 (5) |

| Visceral disease | |||

| Yes | 29 (73) | 10 (67) | 16 (80) |

| No | 11 (27) | 5 (33) | 4 (20) |

| Number of prior lines of endocrine therapy for MBC | |||

| 0 | 18 (45) | 6 (40) | 11 (55) |

| 1 | 10 (25) | 3 (20) | 4 (20) |

| ≥2 | 12 (30) | 6 (40) | 5 (25) |

| Number of prior lines of chemotherapy for MBC | |||

| 0 | 14 (35) | 8 (53) | 4 (20) |

| 1 | 17 (43) | 4 (27) | 11 (55) |

| 2 | 9 (22) | 3 (20) | 5 (25) |

| Prior treatment with Taxane | |||

| Yes | 23 (58) | 6 (40) | 13 (65) |

| No | 17 (43) | 9 (60) | 7 (35) |

Abbreviations ER: estrogen receptor, MBC: metastatic breast cancer

Percentages rounded to nearest percent, so total may not reach 100%

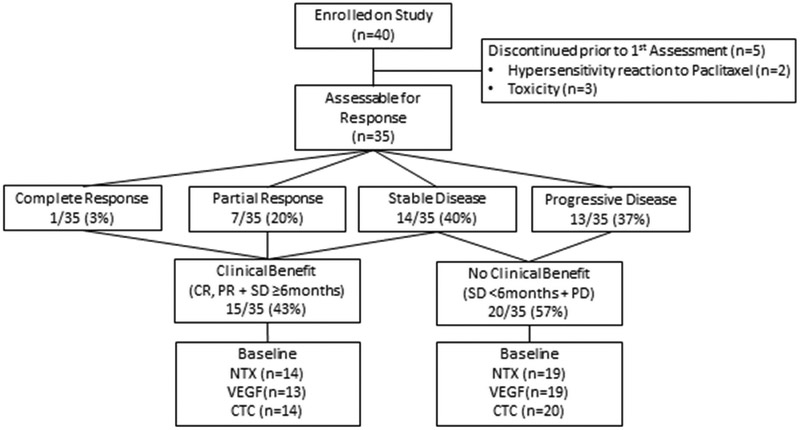

Response

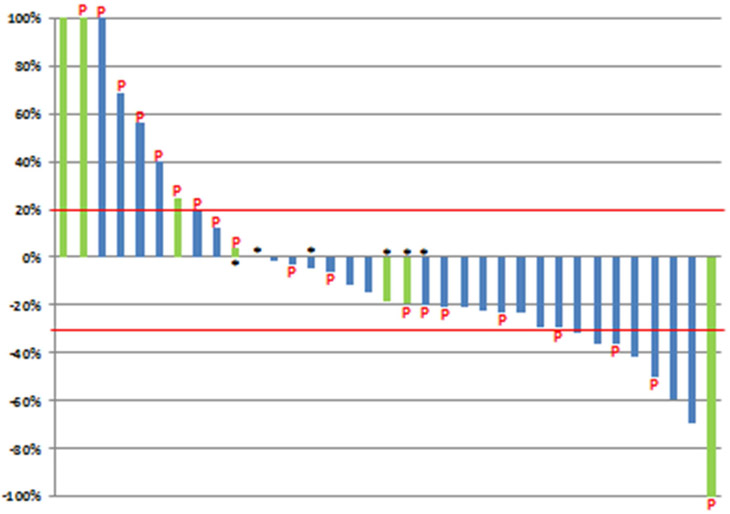

Responses were seen in ≥4/23 (17.4%) patients and enrollment was extended per protocol to stage two. However, due to the slow accrual over a 4 year period, the study was stopped prematurely. Of the final 40 patients, 5 (13%) discontinued treatment before the end of cycle two. Two of these had hypersensitivity reactions to paclitaxel and three discontinued due to unacceptable toxicity, including nausea and diarrhea. Therefore, 35 (88%) patients were evaluable for response per protocol (figure 1). Of these, 1 (3%) patient had a CR and 7 (20%) patients had a PR, resulting in an ORR of 23%. In total, 3/8 patients with disease response had received previous paclitaxel. The patient who achieved a CR had TNBC and all the patients who had a PR had ER positive breast cancer. Overall, the maximum diameter of measurable lesions decreased from baseline in 24 (69 %) patients (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Consort Diagram

Figure 2. Best Response of Target Lesions in Evaluable Patients (n=35).

P= prior therapy with paclitaxel

Green: patients with triple negative breast cancer

Blue: patients with ER positive disease

*Best Response = Progression of Disease (due to development of new lesions or progression of non-measurable disease)

Per protocol, PR was confirmed by repeat CT in 6/7 (86%) patients. One patient with PR discontinued treatment because of excessive toxicity and one patient with CR withdrew consent, prior to response confirmation. The 8 patients who had CR/PR continued on treatment for a median of 10.4 months (range 2.4 – 26.1), including 3 patients who were on treatment for more than one year. The best response to treatment was stable disease in 14 (40%) patients; of whom 7 (50%) had stable disease for ≥ 6 months. Therefore the clinical benefit rate (per protocol) was 43% (15/35). Of these patients, 11/15 (73%) had bone metastases, 6/15 (40%) had received prior taxanes and only one (3%) patient had TNBC.

Bone Metastases

In total, 27 (68%) patients had bone metastases, of whom 24 (89%) were assessable for response. Of these, 11 (46%) had clinical benefit and 13 (54%) did not. The ORR was 15% (4/27, all PR) and 7/27 (26%) had SD. However, 3/27 patients with bone metastases continued on treatment for ≥18 months.

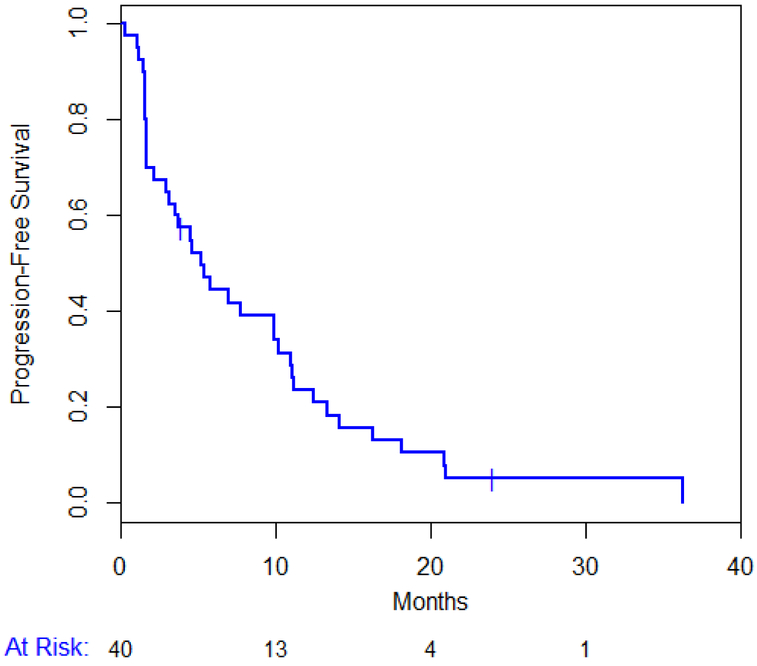

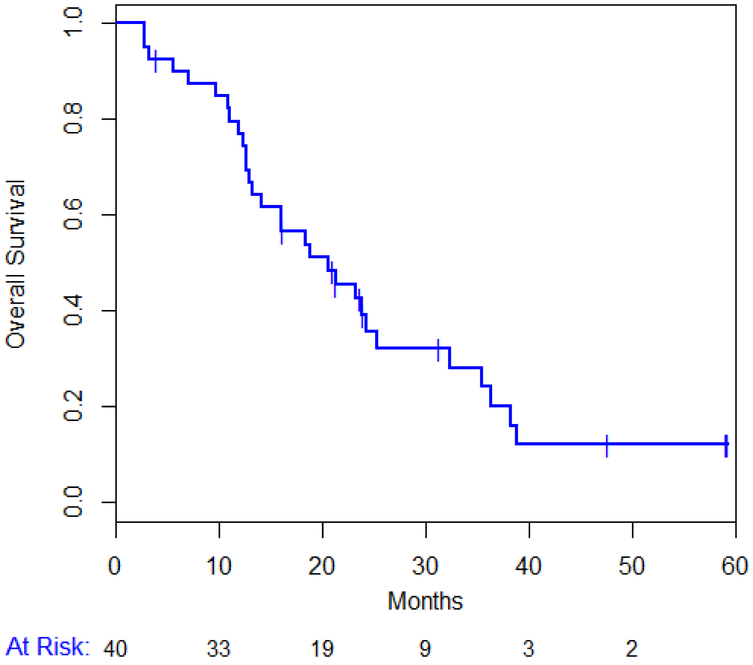

PFS and OS

Out of the 40 enrolled patients, treatment was discontinued in 10 (25%) patients due to excessive toxicity, in 26 (65%) for disease progression and 4 (10 %) patients withdrew consent. All patients have now discontinued study drugs: due to tumor progression in 38/40 (95%) patients. Overall 30 (75%) patients have died. The median PFS for all patients is 5.2 (95% CI 2.9-9.9) months (figure 3A) and the median OS is 20.6 (95% CI 12.9-25.2) months (figure 3B). Median TTP was 5.84 months (range: 0 - 25.7). Median TTP in patients with TNBC was 1.8 months compared to 6.8 months in those with ER positive disease (P = 0.052).

Figure 3.

Progression Free Survival (A) and Overall Survival (B)

Toxicities

In total, 8 (20%) patients required a dose reduction to dasatinib 100 mg; mostly due to fatigue and diarrhea, which subsequently improved. The most common toxicities were hematological and similar to those reported in the prior phase I study (table 2 and 3). Two patients developed pleural effusions, which were at least possibly related to dasatinib. One patient developed a grade II pleural effusion at the first tumor assessment and discontinued treatment for disease progression. Another patient with stable disease had a worsening of a pre-existing small pleural effusion after 7 months of therapy. As expected, fatigue (75%), neuropathy (65%) and diarrhea (50%) were common side-effects, but were generally grade I (table 2). Grade II fatigue, neuropathy and diarrhea occurred in only 10%, 2.5% and 15% patients respectively and no patients had grade ≥ III events.

Table 2.

Toxicities Possibly Related to Paclitaxel and Dasatinib

| Overall | Grade I | Grade II | Grade ≥III | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toxicity | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | -% |

| Pleural Effusion | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.5 | 1 | 2.5 |

| Peripheral edema | 13 | 33 | 11 | 28 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Nausea | 17 | 43 | 13 | 33 | 4 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Rash | 19 | 48 | 17 | 43 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 20 | 50 | 14 | 35 | 6 | 15 | 0 | 0 |

| Neuropathy | 26 | 65 | 25 | 63 | 1 | 2.5 | 0 | 0 |

| Fatigue | 30 | 75 | 26 | 65 | 4 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

Pleural effusion occurred in 2 patients.

Table 3.

Grade III-IV Laboratory Toxicities

| Type | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| ALT elevation | 1 | 2.50% |

| Hypokalemia | 1 | 2.50% |

| Thrombocytopenia | 1 | 2.50% |

| Hyperglycemia | 2 | 5% |

| Hypophosphatemia | 2 | 5% |

| Anemia | 4 | 10% |

| Neutropenia | 4 | 10% |

| Lymphopenia | 8 | 20% |

Overall, 19 (48%) patients had some skin toxicity: which included acneiform rash and hand foot syndrome, although events were grade I in almost all (17/19) patients. Similarly, peripheral edema occurred in 13 (33%) patients, but was grade I in almost all (11/13) patients and was mostly unrelated to dasatinib. Prolonged QTc interval occurred in 4 (10%) patients, although it was asymptomatic and didn`t result in any significant arrhythmia

Biomarkers

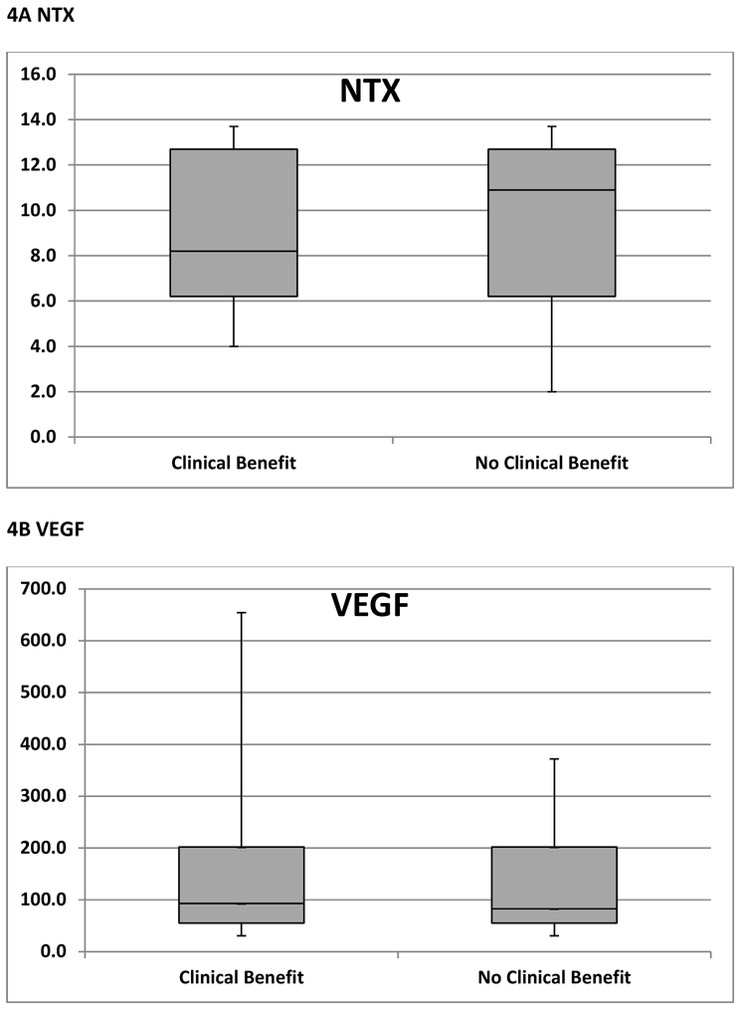

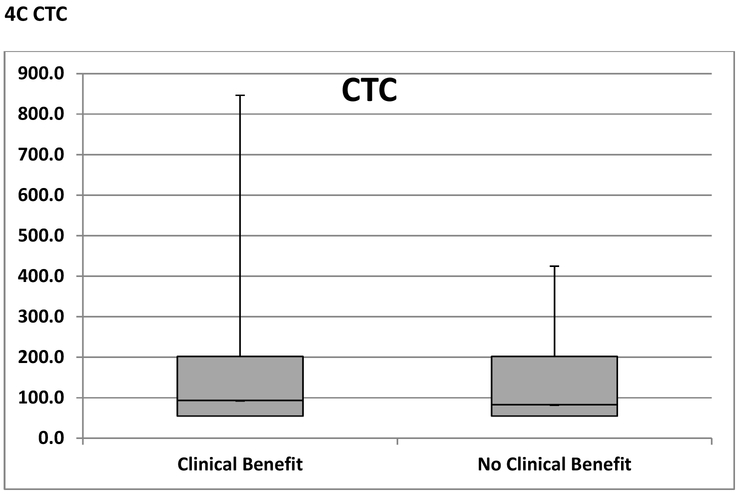

Among patients who had clinical benefit per protocol (N=15), baseline NTX, VEGF and CTCs were available in 14 (93%), 13 (87%) and 14 (93%) patients respectively (figure 1). Among patients who had no clinical benefit per protocol (N =20), baseline NTX, VEGF and CTCs were available in 19 (95%), 19 (95%) and 20 (100%) patients respectively (figure 1). As shown in figure 4A, median baseline NTX was similar in patients who had clinical benefit (8.2) and no clinical benefit (10.9). Similarly, median baseline VEGF and CTC levels were similar between the two groups; 93.0 vs. 83.0 (figure 4B) and 3.5 vs. 3.0 (figure 4C) respectively. Following 2 cycles of treatment, the above biomarkers did not correlate with clinical benefit.

Figure 4. A, B, C Predictive Biomarkers of Benefit from Paclitaxel and Dasatinib.

NTX; Collagen Type IV or N-telopeptide,

VEGF; vascular epidermal growth factor receptor 2

CTC; circulating tumor cells

Box and Whisker plots comparing median (horizontal line), interquartile range (shaded box) and range

Discussion

In this phase II study of dasatinib and paclitaxel the ORR was 23% (8/35), which was below the a priori 30% threshold deemed worthy of further study. However, definitive conclusions are limited as the study closed after 4 years due to slow accrual. Disease control was seen, including in taxane-pretreated patients and the toxicities were similar to our previous phase I study; diarrhea (50%), neuropathy (65% and fatigue (75%) were common 18. Although individual toxicities were generally low grade, it is likely that these effects impacted on Investigators’ decisions to recommend the trial to potential patients. Ultimately, this meant that accrual to a follow up phase III study would likely have been virtually impossible.

Preclinical studies predicted that dasatinib, a potent inhibitor of Src and other tyrosine kinases, would have significant activity in breast cancer 3, 4. However, single agent dasatinib (100mg once daily or 70mg twice daily) appears to have limited activity in unselected MBC 16. Therefore, supported by preclinical work, several studies, like ours, have examined dasatinib with cytotoxic chemotherapy 21, 22. In our previous phase I study of the same combination a 31% (4/13) response rate was seen 18. Similarly, in a phase I trial of dasatinib and capecitabine the response rate was 24% (6/25 patients) 21. The response rate in the current study (23%) was somewhat disappointing, but relatively similar to that seen in the previous (smaller) phase I trial (31%). Collectively, available data from phase I/II trials suggest limited activity for dasatinib with chemotherapy in unselected patients with MBC.

We had hoped to identify a cohort of patients who would derive relatively greater benefit from dasatinib using clinical or biomarker criteria. Since Src activates osteoclasts and is important for the development of osseous metastases, we hypothesized that dasatinib would have greatest benefit in patients with breast cancer bone metastases 3-6. Despite the rationale this, the ORR for this subgroup was only 15% in our study. However, 3/27 patients with bone metastases continued on treatment for ≥18 months, which is noteworthy given the limitation in assessing response in bone using RECIST. The concept that dasatinib could be useful in targeting breast cancer bone metastases was previously investigated in a phase I/II study in combination with zoledronic acid 23. Although a response rate of 23% (5/22) patients was seen, the median time to treatment failure was only 2.7 months in that study 23. The observation that 7/8 patients who had disease response by RECIST had ER positive breast cancer is also interesting, but also conversely suggests very limited activity in TNBC. Despite a preclinical rationale for dasatinib in TNBC, median TTP was only 1.8 months in these patients 14, 15. These results are overall disappointing and argue that dasatinib does not have a role in unselected patients with breast cancer bone metastases.

Given that this was a single arm study there can be no conclusions about the relative effect of either paclitaxel or dasatinib monotherapy on disease control. However, the fact that 3/8 patients with disease response had received previous paclitaxel, suggests at least some activity for dasatinib. Yet, we cannot exclude the possibility that these patients had particularly indolent disease, which was likely to respond to many different treatments (such as a taxane rechallenge). Since Src is important for the development of endocrine resistance, an alternative approach is the possible role of Src inhibitors in combination with endocrine therapy 24. Although letrozole in combination with dasatinib has shown encouraging PFS in a phase II study of postmenopausal women with ER positive HER2 negative MBC, the overall results were also somewhat disappointing 25.

Given that only a subset of patients derived clinical benefit in the current study, the identification of biomarkers was of major interest. Despite a high rate of compliance with baseline serum biomarker acquisition, we were unable to show any correlation between clinical benefit and predetermined biomarkers; NTX, VEGF or CTCs. Other studies have examined a series of biomarkers to predict dasatinib benefit with limited success 21, 26. Pusztai and colleagues examined tumor gene expression using three different predictive signatures, modified from cell line studies 26. Despite the large sample size (93 biopsies from 97 patients) and rigorous techniques, they were unable to identify tissue predictors of dasatinib benefit. In a phase I study in breast cancer, dasatinib (100mg daily) and capecitabine led to a decrease in VEGF-A by a median of 49.5% at 3 weeks and a corresponding increase in NTX by 22.9%, suggesting both anti-angiogenic and Src inhibition 21. In contrast, dasatinib 150mg combined with 5-fluorouracail, oxaliplatin and cetuximab failed to show any significant evidence of Src inhibition in a phase Ib/II study in metastatic colorectal cancer 27. Specifically, there was no change in tumor expression of phospho-Src after 3 weeks of combination treatment in patients with paired tumor samples taken from liver metastases. Collectively, these results suggest that although dasatinib with chemotherapy is associated with a decrease in serum biomarkers of angiogenesis and Src, there does not appear to be demonstrable Src inhibition within metastases, thereby limiting clinical utility of this agent.

Overall, this phase II study showed some clinical activity for the combination of dasatinib and paclitaxel in an unselected cohort of patients with MBC, but the slow accrual and cumulative toxicities mean that a confirmatory phase III study is not planned. It is hoped that biomarkers might allow the development of more potent, highly specific Src inhibitors in carefully selected patients with breast cancer in the future.

Clinical Practice Point

Although there was a strong biological rationale for combining the SRC inhibitor dasatinib with paclitaxel in metastatic breast cancer, this combination cannot be recommended for further study due to cumulative toxicities. More specific inhibitors of SRC might have more clinical utility in this setting.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by Bristol Myers Squibb

Footnotes

Disclosures

Monica Fornier has received grant support from BMS. Patrick Morris has received honoraria from BMS. All other authors have no disclosures to report.

Presented in Part at

32nd Annual San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, December 2009, San Antonio, Texas

American Society of Clinical Oncology 46th Annual Meeting, June 2010, Chicago, Illinois.

33rd Annual San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, December 2010, San Antonio, Texas

35th Annual San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, December 2012, San Antonio, Texas

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mayer EL, Krop IE. Advances in targeting SRC in the treatment of breast cancer and other solid malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:3526–3532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finn RS. Targeting Src in breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1379–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Verbeek BS, Vroom TM, Adriaansen-Slot SS, et al. c-Src protein expression is increased in human breast cancer. An immunohistochemical and biochemical analysis. J Pathol. 1996;180:383–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Myoui A, Nishimura R, Williams PJ, et al. C-SRC tyrosine kinase activity is associated with tumor colonization in bone and lung in an animal model of human breast cancer metastasis. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5028–5033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miyazaki T, Sanjay A, Neff L, Tanaka S, Horne WC, Baron R. Src kinase activity is essential for osteoclast function. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:17660–17666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang XH, Wang Q, Gerald W, et al. Latent bone metastasis in breast cancer tied to Src-dependent survival signals. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:67–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morris PG, McArthur HL, Hudis CA. Therapeutic options for metastatic breast cancer. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2009;10:967–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morris PG, Lynch C, Feeney JN, et al. Integrated positron emission tomography/computed tomography may render bone scintigraphy unnecessary to investigate suspected metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3154–3159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosen LS, Gordon D, Kaminski M, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of zoledronic acid compared with pamidronate disodium in the treatment of skeletal complications in patients with advanced multiple myeloma or breast carcinoma: a randomized, double-blind, multicenter, comparative trial. Cancer. 2003;98:1735–1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stopeck AT, Lipton A, Body JJ, et al. Denosumab compared with zoledronic acid for the treatment of bone metastases in patients with advanced breast cancer: a randomized, double-blind study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:5132–5139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shah NP, Kim DW, Kantarjian H, et al. Potent, transient inhibition of BCR-ABL with dasatinib 100 mg daily achieves rapid and durable cytogenetic responses and high transformation-free survival rates in chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia patients with resistance, suboptimal response or intolerance to imatinib. Haematologica. 2010;95:232–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Talpaz M, Shah NP, Kantarjian H, et al. Dasatinib in imatinib-resistant Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemias. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2531–2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nautiyal J, Majumder P, Patel BB, Lee FY, Majumdar AP. Src inhibitor dasatinib inhibits growth of breast cancer cells by modulating EGFR signaling. Cancer Lett. 2009;283:143–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finn RS, Dering J, Ginther C, et al. Dasatinib, an orally active small moleculeinhibitor of both the src and abl kinases, selectively inhibits growth of basal-type/“triple-negative” breast cancer cell lines growing in vitro. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2007; 105:319–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qian XL, Zhang J, Li PZ, et al. Dasatinib inhibits c-src phosphorylation and prevents the proliferation of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC) cells which overexpress Syndecan-Binding Protein (SDCBP). PLoS One. 2017;12:e0171169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schott AF, Barlow WE, Van Poznak CH, et al. Phase II studies of two different schedules of dasatinib in bone metastasis predominant metastatic breast cancer: SWOG S0622. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;159:87–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Company B-MS. Preclinical pharmacology of dasatinib, a SRC protein kinase inhibitor. 2003:Control No. 930003300. . [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fornier MN, Morris PG, Abbruzzi A, et al. A phase I study of dasatinib and weekly paclitaxel for metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:2575–2581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seidman AD, Berry D, Cirrincione C, et al. Randomized phase III trial of weekly compared with every-3-weeks paclitaxel for metastatic breast cancer, with trastuzumab for all HER-2 overexpressors and random assignment to trastuzumab or not in HER-2 nonoverexpressors: final results of Cancer and Leukemia Group B protocol 9840. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1642–1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Somlo G, Atzori F, Strauss LC, et al. Dasatinib plus capecitabine for advanced breast cancer: safety and efficacy in phase I study CA180004. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:1884–1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeong YJ, Kang JS, Lee SI, et al. Breast cancer cells evade paclitaxel-induced cell death by developing resistance to dasatinib. Oncol Lett. 2016;12:2153–2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitri Z, Nanda R, Blackwell K, et al. TBCRC-010: Phase I/II Study of Dasatinib in Combination with Zoledronic Acid for the Treatment of Breast Cancer Bone Metastasis. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:5706–5712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larsen SL, Laenkholm AV, Duun-Henriksen AK, Bak M, Lykkesfeldt AE, Kirkegaard T. SRC drives growth of antiestrogen resistant breast cancer cell lines and is a marker for reduced benefit of tamoxifen treatment. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0118346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paul D, Vukelja S, Holmes F, et al. Letrozole plus dasatinib improves progression-free survival (PFS) in hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative postmenopausal metastatic breast cancer (MBC) patients receiving first-line aromatase inhibitor (AI) therapy Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;159:87–95.27475087 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pusztai L, Moulder S, Altan M, et al. Gene signature-guided dasatinib therapy in metastatic breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:5265–5271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parseghian C, Parikh NU, Wu JY, et al. Dual Inhibition of EGFR and c-Src by Cetuximab and Dasatinib Combined with FOLFOX Chemotherapy in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;9:1078–0432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]