ABSTRACT

Pexastimogene devacirepvec (Pexa-Vec) is a vaccinia virus-based oncolytic immunotherapy designed to preferentially replicate in and destroy tumor cells while stimulating anti-tumor immunity by expressing GM-CSF. An earlier randomized Phase IIa trial in predominantly sorafenib-naïve hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) demonstrated an overall survival (OS) benefit. This randomized, open-label Phase IIb trial investigated whether Pexa-Vec plus Best Supportive Care (BSC) improved OS over BSC alone in HCC patients who failed sorafenib therapy (TRAVERSE).

129 patients were randomly assigned 2:1 to Pexa-Vec plus BSC vs. BSC alone. Pexa-Vec was given as a single intravenous (IV) infusion followed by up to 5 IT injections. The primary endpoint was OS. Secondary endpoints included overall response rate (RR), time to progression (TTP) and safety.

A high drop-out rate in the control arm (63%) confounded assessment of response-based endpoints. Median OS (ITT) for Pexa-Vec plus BSC vs. BSC alone was 4.2 and 4.4 months, respectively (HR, 1.19, 95% CI: 0.78–1.80; p = .428). There was no difference between the two treatment arms in RR or TTP. Pexa-Vec was generally well-tolerated. The most frequent Grade 3 included pyrexia (8%) and hypotension (8%). Induction of immune responses to vaccinia antigens and HCC associated antigens were observed.

Despite a tolerable safety profile and induction of T cell responses, Pexa-Vec did not improve OS as second-line therapy after sorafenib failure. The true potential of oncolytic viruses may lie in the treatment of patients with earlier disease stages which should be addressed in future studies.

ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01387555

KEYWORDS: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Pexa-Vec, sorafenib, oncolytic immunotherapy, oncolytic vaccinia

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the third most common cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide .1 Approximately 750,000 people develop HCC globally each year with ~80% of cases reported in developing countries .2 Sorafenib and lenvatinib, both multikinase inhibitors that target multiple signaling pathways, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling, 3–5 are the only systemic therapies currently approved for the first-line treatment of patients with advanced or metastatic HCC .5–7 Nevertheless, drug-induced toxicities often require dose reductions or treatment discontinuation.8,9 Moreover, tumor response is rare following RECIST criteria .6,7,10 Several agents have been investigated in the setting of sorafenib failure, 11–19 and so far, the multikinase inhibitors cabozantinib14 and regorafenib, 15 and the PD-1 inhibitors nivolumab16 and pembrolizumab17,19 have been approved for this setting by the FDA (in the case of regorafenib also by the EMEA). Furthermore, while ramucirumab, an antibody inhibiting VEGF receptor-2, failed to improve survival of advanced HCC patients in the second line setting, 13 it showed to have a significant survival benefit in patients with AFP levels ≥400 ng/mL18 and is awaiting approval in this patient population. Because of the success of immune checkpoint inhibitors in several cancer entities and the encouraging data from nivolumab and pembrolizumab in HCC patients, different cancer immunotherapies have to be explored in HCC, which still remains an important unmet medical need especially in the intermediate and advanced stage.

Oncolytic immunotherapy represents a novel therapeutic platform for the treatment of cancer with unique attributes compared with conventional chemotherapy or targeted agents .20–24 Oncolytic viruses may not only selectively infect and lyse tumor cells relative to normal cells leading to a broad therapeutic range but may also reactivate the immune system against tumor-specific antigens. Recently, the first oncolytic immunotherapy was approved for melanoma (talimogene laherparepvec; T-VEC), paving the way for Phase II/III development of oncolytic immunotherapies in other indications.

Pexa-Vec (pexastimogene devacirepvec; JX-594) is a thymidine kinase gene-inactivated oncolytic vaccinia virus engineered to express the transgenes human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and β-galactosidase .25–27 In phase I/II trials of intratumoral (IT) injection into advanced HCC tumors (primarily in the first-line setting), Pexa-Vec was well-tolerated, and associated with a dose-related survival benefit .28

Here we report the Phase IIb TRAVERSE study which evaluated safety and efficacy of Pexa-Vec plus BSC compared to treatment with BSC alone in patients whose tumor had progressed on/after sorafenib treatment or who were intolerant to sorafenib. Viral and immune correlate analyses were also performed. Thus, this is the first large randomized trial of an oncolytic immunotherapy in HCC patients and the second world-wide late-stage, randomized trial of an oncolytic immunotherapy .29

Results

Patient characteristics, disposition and treatment

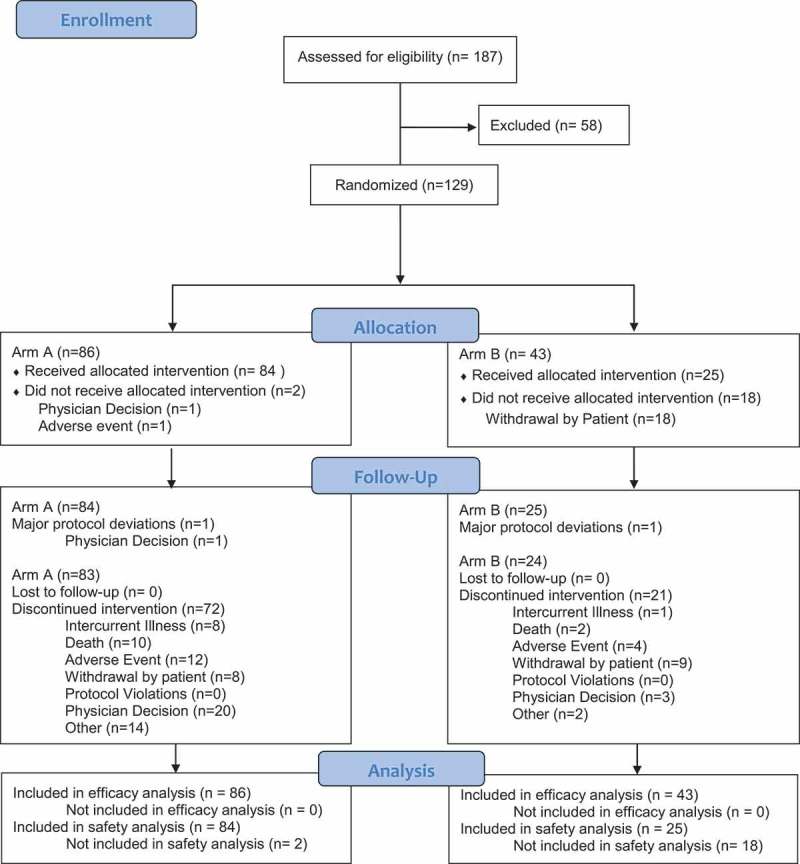

Between October 24, 2011 and June 4, 2013, 129 patients were assigned to treatment and included in the intent-to-treat analyses (Pexa-Vec plus BSC, n = 86; BSC alone, n = 43; Figure 1). Twenty-five percent of patients were from North America, 54% from Asia, and 21% from Europe. Demographics and disease characteristics were generally balanced between the two arms, except for mean age (Pexa-Vec, 60; BSC, 55 years; p = 0.045; Table 1). Baseline characteristics were macroscopic vascular invasion (23%), extrahepatic disease (73%), Child-Pugh class A (88%), BCLC stage C (85%), ECOG equal to 2 (3%), prior surgery (39%), prior loco-regional therapy (69%), and prior radiation therapy (19%). Most patients had progression on prior sorafenib (88%) and one or more known risk factors for HCC, including hepatitis B (51%), hepatitis C (14%) and alcohol (19%). Patients had advanced-stage HCC (BCLC stage C 85%) with preserved liver function (Child-Pugh class A 88%) and good performance status (ECOG 0 or 1 97%). Patients exhibited a high tumor burden in the liver, with a median sum of longest diameters (SLD) of 104 mm, a median number of 4 target liver tumors as well as a high median alpha fetoprotein (AFP) blood level (794 ng/mL) (55% patients >200 ng/mL at baseline; median 863 vs. 398 ng/ml (p = 0.472) experimental vs control arm, respectively).

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram of sorafenib-pretreated patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in the TRAVERSE study.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics of the patients (Intent-to-treat population).

| Variable | Pexa-Vec + BSC (N = 86) |

BSC (N = 43) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years)- Mean (SD)* | 60 (11) | 55 (12) |

| *p = .005 | ||

| Gender – n (%) | ||

| Female | 14 (16) | 10 (23) |

| Male | 72 (84) | 33 (77) |

| Stratum: Asian Region – n (%) | ||

| Asian | 46 (54) | 24 (56) |

| non Asian | 40 (47) | 19 (44) |

| Stratum: Sorafenib Therapy – n (%) | ||

| Intolerance | 11 (13) | 5 (12) |

| Progression | 75 (87) | 38 (88) |

| Stratum: Extra-hepatic spread – n (%) | 62 (72) | 32 (74) |

| Race – n (%) | ||

| Asian | 52 (62) | 26 (62) |

| White | 30 (36) | 15 (36) |

| Other | 2 (2) | 1 (2) |

| Cirrhosis – n (%) | 57 (66) | 30 (70) |

| Etiology of Disease – n (%) | ||

| Hepatitis B | 42 (49) | 24 (56) |

| Hepatitis C | 10 (12) | 8 (19) |

| Alcohol | 17 (20) | 7 (16) |

| NASH | 8 (9) | 4 (9) |

| Other | 10 (12) | 1 (2) |

| Child-Pugh Status – n (%) | ||

| Class A | 76 (88) | 37 (86) |

| Class B (7 points) | 10 (12) | 6 (14) |

| ECOG PS – n (%) | ||

| Grade < 2 | 82 (95) | 43 (100) |

| Grade 2 | 4 (5) | 0 (0) |

| BCLC Stage (based on local) – n (%) | ||

| B-Intermediate | 11 (13) | 9 (21) |

| C-Advanced | 75 (87) | 34 (79) |

| AFP (ng/mL) | ||

| Median (Range) | 863 (2–1802066) | 398 (1–516204) |

| > 200 – n (%) | 51 (62) | 20 (50) |

| TK-1 (DU/L), Median (Range) | 350 (7–5587) | 219 (35–1706) |

| Duration of Prior Sorafenib (months), Median (Range) | 4 (1–41) | 4 (1–26) |

| Prior non-systemic therapies – n (%) | ||

| Surgical resection | 33 (38) | 17 (40) |

| TACE | 49 (57) | 27 (63) |

| RFA | 16 (19) | 9 (21) |

| Radiation Therapy | 19 (22) | 6 (14) |

| Macroscopic vascular invasion – n (%) | 20 (23) | 10 (23) |

| Tumor burden (SLD) in the liver (mm), Median (Range) | 105 (15–257) | 102 (34–314) |

Blinding of the study was not feasible due to the ethical issues associated with sham intratumoral injection. Two patients on the Pexa-Vec arm did not receive treatment. Of note, only 13% of patients completed the protocol-specified regimen: 98% of patients received the IV Pexa-Vec infusion, while 84%, 67%, 51%, 27%, and 13% went on to receive the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, and 6th treatments (all IT), respectively (Supplementary Table). Approximately half the patients (51%) received at least three IT treatments (over the course of the first 6 weeks) as administered in the previous trial of Pexa-Vec in HCC.

Efficacy

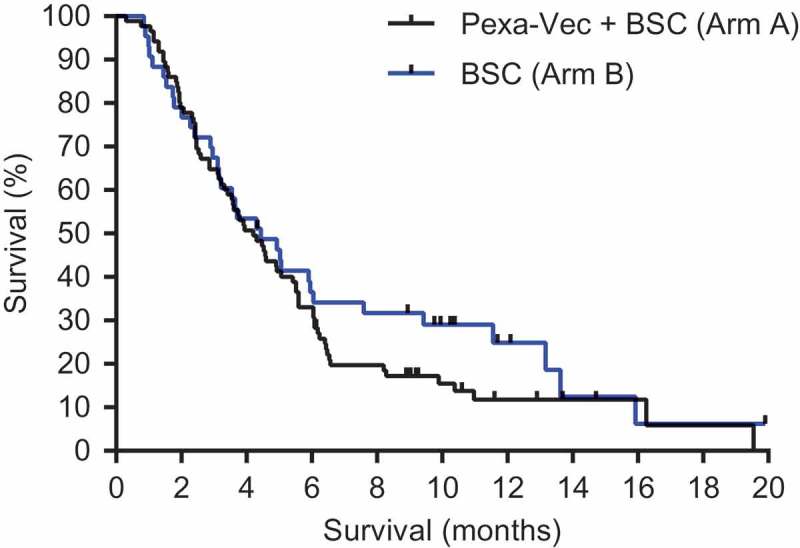

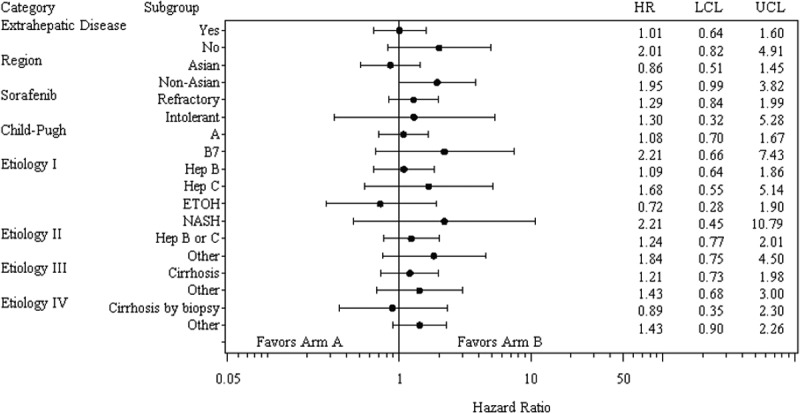

Based on the ITT analysis with 109 deaths, the primary endpoint of OS with Pexa-Vec plus BSC vs BSC alone was not met (HR, 1.19, 95% CI: 0.78 to 1.80; p = 0.428, stratified log-rank test, Figure 2). Median OS was 4.2 for the Pexa-Vec plus BSC arm and 4.4 months for the BSC alone arm. A multivariate Cox analysis of prespecified baseline factors revealed no statistically significant difference in survival between the 2 arms within subgroups (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimates overall survival (OS). OS was computed on all randomized patients. Those patients who had not died or were lost to follow-up at the time of database lock were censored on the last date on which they were known to be alive.

Figure 3.

Overall survival in selected subsets. Hep B, hepatitis B; Hep C, hepatitis C; EtOH, alcohol, NASH, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; HR, hazard ratio; LCL lower control limit; UCL, upper control limit.

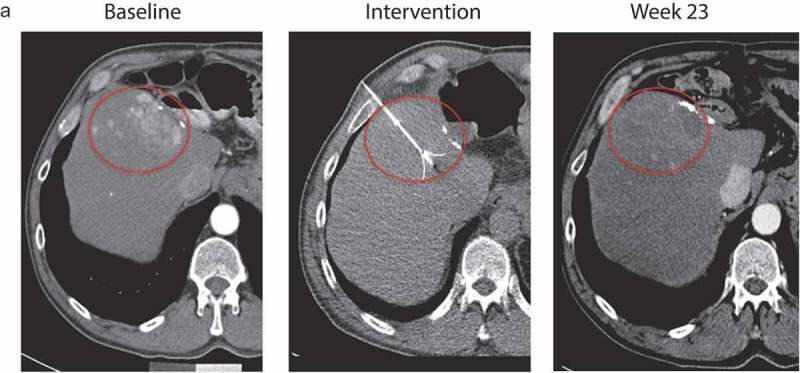

A total of 48 patients (37%) were not evaluable for tumor response. In particular, there was a high drop-out rate in the control arm, with 63% of Arm B patients not evaluable radiographically. Therefore, no valid comparisons in response and disease control rate (DCR) can be made. DCR was 13% in the Pexa-Vec/BSC group vs. 18% in the BSC alone group (Table 2). No patient on either arm responded according to mRECIST. Median TTP was 1.8 (95% CI: 1.5 to 2.8 months) in Arm A vs 2.8 months in Arm B (95% CI: 1.5 months to not unable to evaluate due to censoring; p = 0.463, stratified log-rank test). The overall HR was 1.33 (95% CI: 0.61 to 2.90; p = 0.478). One patient exhibited a mixed response to Pexa-Vec treatment (Figure 4). The injected tumor responded but the patient recurred at a distant site in the liver. Though the patient had histological confirmation of HCC at diagnosis, the recurrent tumor was classified as cholangiocarcinoma upon histopathological analysis.

Table 2.

mRECIST response assessment (ITT).

| Best mRECIST Tumor Response | Pexa-Vec + BSC(N=86) | BSC(N=43) |

|---|---|---|

| Not Evaluable (NE) - n (%) Due to: |

21 (24) | 27 (63) |

| Death - n (%) | 5 (6) | 1 (2) |

| AE - n (%) | 6 (7) | 2 (5) |

| Physician’s Decision - n (%) | 6 (7) | 1 (2) |

| Consent withdrawal - n (%) | 2 (2) | 23 (53) |

| Intercurrent illness - n (%) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Complete Response (CR) - n (%) | 0 | 0 |

| Partial Response (PR) - n (%) | 0 | 0 |

| Stable Disease (SD) - n (%) | 11 (13) | 8 (19) |

| Progressive Disease (PD) - n (%) | 37 (43) | 7 (16) |

| Disease Control Rate (CR, PR, or SD) | 0.13 | 0.19 |

| 95% CI for DCR | (0.07, 0.22) | (0.08, 0.33) |

| P-value | 0.349 | |

Figure 4.

Patient 211–001 exhibited a response to Pexa-Vec treatment in the injected tumor as demonstrated by CT scans of this patient before (baseline), during (intervention) and 23 weeks after treatment showing a strong reduction in the extent of the tumor at week 23.

Safety

Adverse events (AEs) occurring more frequently among patients receiving Pexa-Vec were mostly mild (grade 1–2) and included pyrexia, chills, decreased appetite, nausea, hypotension, and papulopustular rash. Six patients presented with at least one AE related to the IT injection procedure (7%): grade 3–4 AEs included hypotension (2%), hepatic hemorrhage and staphylococcal sepsis, upper abdominal pain, anemia, ascites, acute respiratory failure, fluid overload, pleural effusion, acute renal failure, and increased troponin (1% each).

The overall frequency of treatment-emergent AEs was quite high in both arms, with 100% in the Pexa-Vec plus BSC arm and 84% in the BSC alone arm (Table 3). Treatment-related grade 3 AEs that occurred with a frequency of ≥5% with Pexa-Vec were pyrexia and hypotension (8% each).

Table 3.

Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) of all grades and grades 3–5 by treatment arm, regardless of relationship (incidence ≥10% in Arm A).

| Treatment Arm | Pexa-Vec+ BSC (N = 84) n(%) |

BSC alone (N = 25) n(%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred Term | All grades | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | All grades | Grade 3 | Grade 4 |

| Number (%) of Patients with at least one AE | 84 (100) | 45 (54) | 8 (9) | 21 (84) | 7 (28) | 2 (8) |

| Pyrexia | 67 (80) | 7 (8) | 1 (1) | 3 (12) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Chills | 44 (52) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Abdominal pain | 32 (38) | 4 (5) | 0 (0) | 8 (32) | 3 (12) | 0 (0) |

| Decreased appetite | 31 (37) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (12) | 2 (8) | 0 (0) |

| Nausea | 30 (36) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 4 (16) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Hypotension | 24 (29) | 8 (9) | 0 (0) | 3 (12) | 2 (8) | 0 (0) |

| Rash pustular | 24 (29) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Anemia | 22 (26) | 9 (10) | 0 (0) | 4 (16) | 2 (8) | 0 (0) |

| Fatigue | 22 (26) | 3 (4) | 0 (0) | 2 (8) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Ascites | 21 (25) | 3 (4) | 0 (0) | 8 (32) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) |

| AST increased | 20 (24) | 14 (17) | 4 (5) | 6 (24) | 5 (20) | 1 (4) |

| Blood bilirubin increased | 20 (24) | 17 (20) | 2 (2) | 4 (16) | 3 (12) | 1 (4) |

| Influenza like illness | 20 (24) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Vomiting | 18 (21) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Diarrhea | 17 (20) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (20) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Abdominal pain upper | 16 (19) | 3 (4) | 0 (0) | 2 (8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Asthenia | 16 (19) | 4 (5) | 0 (0) | 4 (16) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Edema peripheral | 16 (19) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 4 (16) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Abdominal distension | 15 (18) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (8) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Constipation | 15 (18) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (12) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Headache | 14 (17) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| ALT increased | 13 (15) | 11 (13) | 0 (0) | 2 (8) | 2 (8) | 0 (0) |

| Back pain | 11 (13) | 3 (4) | 0 (0) | 2 (8) | 1 (4) | 1 (4) |

| Insomnia | 11 (13) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Dyspnea | 10 (12) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 3 (12) | 2 (8) | 0 (0) |

| Musculoskeletal pain | 9 (11) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Pleural effusion | 9 (11) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Pruritus | 9 (11) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Twenty-three patients experienced an AE leading to death, 17 in arm A (20%) and 6 in arm B (24%). The primary reason for an AE-related death was a hepatic failure, 6 in arm A (7%) and 2 in arm B (8%); other reasons were related to the worsening of liver function and progression of the disease. One death in arm A (1%) was considered possibly related to treatment (hepatic failure). The treating physician stated while the progressive disease was the likely cause of death, the contribution of Pexa-Vec to the patient’s liver failure could not be completely ruled out due to the absence of CT imaging just prior to death. No deaths were considered procedure-related.

Assessment of quality of life and time to symptomatic progression was confounded by the high patient dropout rate.

Pexa-Vec replication and shedding

Induction of antibodies to the Pexa-Vec transgene product β-galactosidase was used as a marker of Pexa-Vec replication and transgene expression (β-galactosidase is not present in the virion product; high-level expression requires replication). Fifty-six percent of evaluable arm A patients (39/70) exhibited an induction of anti-β-galactosidase antibodies over the course of the study, thereby indicating robust Pexa-Vec replication in these patients.

In addition, urine and throat swab samples were collected for Pexa-Vec titer (infectious unit) analysis. Pexa-Vec was recovered from throat swabs at the pre-day 8 timepoint in 36% (9/25) evaluable arm A patients. Samples for all subsequent timepoints (days 15, 22 and 29) were negative. All urine samples were tested negative at all timepoints (24 patients; days 8, 15, 22, 29).

Rectal swab samples were tested for Pexa-Vec genomes by qPCR analysis given that it was not feasible to perform a plaque assay on these samples. Genomes were detected at the pre-day 8 timepoint in 21% (5/24) evaluable arm A patients. Samples from all subsequent timepoints (days 15, 22 and 29) were negative.

Finally, a subset of Pexa-Vec related pustules were sampled and tested; Pexa-Vec could be recovered from the site of skin pustules.

T cell induction to Pexa-Vec, β-galactosidase and tumor antigens

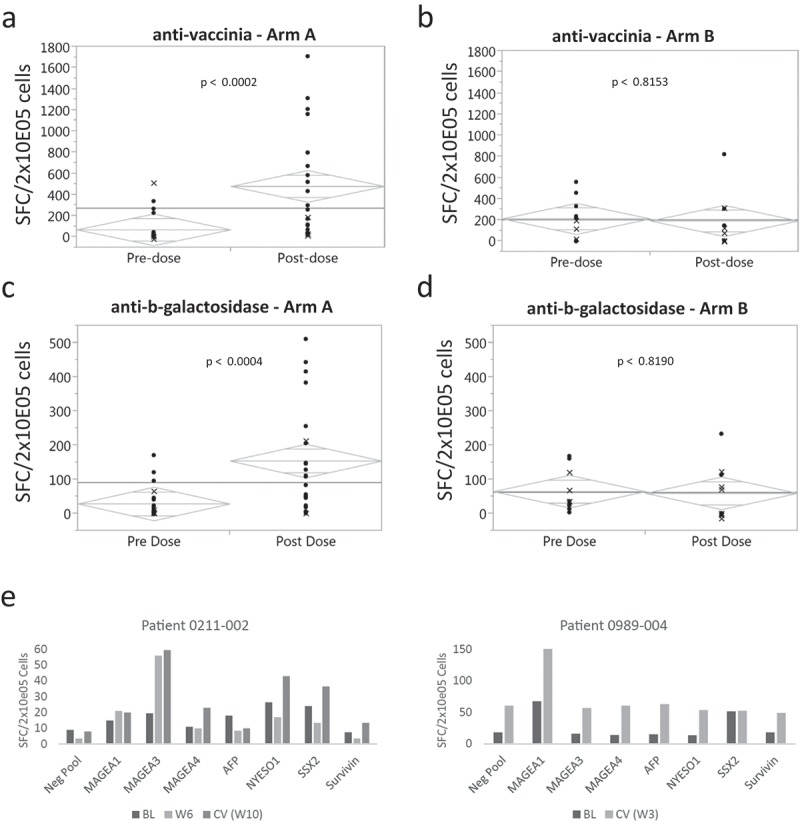

ELISPOT analysis of PBMCs from patients (23 patients for vaccinia and 22 patients for β-galactosidase) indicated that most developed increased T-cell responses to vaccinia and β-galactosidase peptides, although the T-cell responses to β-galactosidase were not as strong as the responses to vaccinia (Figure 5(a,c)). Even though the T-cell responses were measured using a cultured ELISPOT assay, a clear signal for an increase in T-cells from baseline was observed in many patients. The number of T-cells was usually highest at week 6 (for patients with post-dose samples after week 6). Statistical difference was observed between baseline and post-dose responses for both vaccinia in the paired T-test (p = 0.0002) and beta-galactosidase (p = 0.0004). Notably, analysis of PBMCs from 10 patients from the control arm indicated that there were no statistical increases between baseline and post-dose responses for both vaccinia (p = 0.8153) and beta-galactosidase (p = 0.8190) (Figure 5(b,d)). HCV-specific T-cell responses were observed in a subset of HCV positive patients (number of positive/total patients: arm A 3/4; arm B 0/3; Supplementary Figure).

Figure 5.

ELISPOT analysis of immune response to vaccinia, β-galactosidase and tumor antigens before (pre-dose) and 6 weeks after treatment (post-dose). Detection of T-cells specific for (a) vaccinia and (c) β-galactosidase peptides for all evaluable patients treated with Pexa-Vec (23 patients for vaccinia [A] and 22 patients for β-galactosidase [C]) and for 10 patients in the control arm (b = vaccinia and d = β-galactosidase peptides) is shown. The y axis represents the SFC/2x10E05 of the sample normalized by subtracting the respective negative pool (NC). The grey diamonds represent the 95% confidence interval. The data points depicted with an x indicate that one of the replicate values for either the sample or the respective negative pool was missing. (e) Detection of T-cells specific for tumor-associated antigen peptides for two patients with detectable responses against MAGE-A1 and MAGE-A3, respectively. Detection of T-cells specific for HCV peptides in HCV positive patients (Supplementary Figure).

T-cell responses to the following tumor-associated antigens were also measured: MAGE-A1, MAGE-A3, MAGE-A4, AFP, NYESO-1, SSX2 and Survivin. These antigens have been associated with HCC in a subset of patients, 30–32 although tumor antigen expression was not confirmed on patients from this study. Tumor antigen-specific T-cell responses were observed in five patients against the tumor antigens MAGE-A1, MAGE-A3 and Survivin (Figure 5(e); data not shown for Survivin). MAGE-A1 and MAGE-A3 are among the most frequently expressed tumor antigens in HCC patients with an expression frequency of 75% and 70%, respectively .30,31 These data suggest that Pexa-Vec can induce or reactivate tumor-specific T-cells in patients.

Discussion

There is a great need for agents with novel mechanisms-of-action in the setting of sorafenib-refractory HCC .33 The advent of immune checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of various cancers including HCC has put the development of effective cancer immunotherapies in the spotlight. It is well known that the immune system plays a central role in hepatocarcinogenesis and HCC progression .34 However, the heterogeneity of HCC also affects its tumor microenvironment and the infiltrating immune cells. In this regard, an immune subclass of HCC has recently been defined .35 Therefore, not all HCC patients will benefit equally from different kinds of immunotherapy. However, it has been shown that HCCs with a higher proportion of T cells and cytotoxic cells as well as a lower proportion of macrophages and Th2 cells generally have a better survival .36 Hence, developing immunotherapies which modulate the frequency and activity of these immune cells in HCC appears to be a promising approach.

Pexa-Vec is a vaccinia virus-based oncolytic immunotherapy engineered to preferentially infect and replicate in tumor cells while producing GM-CSF from infected tumor cells, thereby exposing additional tumor antigens in the context of virus infection and GM-CSF expression. A previous study in predominantly sorafenib-naïve HCC, both tumor response and an overall survival improvement (when comparing high vs low-dose Pexa-Vec treatment) was demonstrated .28

The TRAVERSE study is the first large, international randomized study of an oncolytic immunotherapy in HCC. In this Phase IIb study evaluating Pexa-Vec plus BSC vs. BSC alone, no difference in OS as the primary endpoint was observed. Major prognostic factors relating both to tumor burden and underlying liver function were well-balanced in both arms. Although there was also no significant difference between the two arms for the secondary endpoints, DCR, RR and TTP, any conclusion is severely limited by the high drop out and non-evaluable patient rate on both arms, with 24% and 63% of patients not being evaluable for response in the investigational and control arm, respectively. The inability to blind the study treatment almost certainly led to the high drop-out rate on the control arm; blinding was not feasible as it is not ethical to perform a sham IT procedure.

Pexa-Vec treatment had an acceptable safety profile. Frequently occurring AEs were mostly flu-like symptoms, a safety profile similar to other OVs .29 The only grade 3 or 4 AEs occurring in ≥5% of Pexa-Vec treated patients were hypotension and pyrexia. One death was potentially related to Pexa-Vec treatment.

Induction of immune responses to vaccinia, the β-galactosidase transgene, HCV and tumor antigens were observed in a subset of patients during the first 6 weeks. By contrast, anti-tumor immune responses have not been reported in patients treated with sorafenib. Furthermore, suppression of hepatitis B virus (HBV) replication was also observed in HCC patients in a Phase 1 study of Pexa-Vec .37

Although cross-study comparisons must be considered at best as hypothesis generating analyses, it is notable that the median OS in the control arm on TRAVERSE (4.4 months) is much shorter than the median survival in the control arm of other second-line HCC studies that enrolled at approximately the same time using similar entry criteria; for instance 8.2 months in the brivanib BRISK PS study, 12 7.3 months in the everolimus EVOLVE-1 study, 38 7.6 months in the ramucirumab REACH study, 13 9.7 months in the axitinib trial, 11 and 7.8 months in the regorafenib RESORCE study which led to the subsequent approval of regorafenib in the sorafenib-refractory setting .15 Although it is unclear why OS on TRAVERSE for both the control and the treatment arms was lower (~4 vs ~7–8 months) compared to that of these phase 3 studies in the second-line setting despite similar entry criteria, it is notable that TRAVERSE enrolled a greater number of patients from Asia and those with hepatitis B than other phase 3 studies.

Interestingly, the only other completed late-stage trial of an oncolytic immunotherapy – the OPTiM study of T-VEC in advanced melanoma – revealed in a subset analysis an OS benefit in treatment naïve and earlier stage patients but not treatment-refractory and later stage patients .29 T-VEC efficacy was most pronounced in patients with earlier-stage disease and in patients who did not receive prior systemic therapy. This observation is similar to the data generated with Pexa-Vec in HCC. In a prior study of three IT injections of Pexa-Vec in patients with primarily sorafenib-naïve HCC, a statistically significant improvement in OS was observed in a high dose cohort vs a low-dose cohort .28 These observations from both T-Vec and Pexa-Vec trials may indicate that earlier-stage and treatment-naïve disease is more likely to respond to oncolytic immunotherapy treatment. This may be expected as an oncolytic viral infection of tumors can trigger induction of anti-tumor immunity .28,39–42 The limited lifespan of patients with very advanced stage disease may not allow sufficient time for patients to first develop and then respond to any induced anti-tumor immunity. Alternatively, pre-treated late-stage patients may not be the optimal target patient population for oncolytic virus-based anti-tumor activity, particularly if mediated by immune induction, given their relatively more suppressed immune status.

Another potential efficacy limiting factor may have been neutralizing antibodies (NAb) against JX-594. Although NAb were not measured in this study, it is known from the previous JX-594-IT-HEP007 trial that NAb are present in patients (in 50% at baseline and in all patients 4 weeks after treatment start) .28 While the presence or absence of NAb at baseline did not correlate with survival duration in that study, it remains possible that anti-viral immunity limited the activity of JX-594 in the present study.

Agents with novel mechanisms-of-action are required for patients with HCC .33 Recent studies of immune checkpoint inhibitors, including the PD-1 inhibitors nivolumab16 and pembrolizumab17,19 as well as the CTLA-4 blocking antibody tremelimumab, 43,44 have shown promise in HCC patients. Given that oncolytic immunotherapies such as Pexa-Vec infect tumors and prime anti-tumor immunity, Pexa-Vec may complement immune checkpoint inhibitors, which are designed to enable an existing anti-tumor immune response, or other types of immunotherapy, which modulate the tumor microenvironment, e.g. by increasing the frequency of immune effector cells such as T cells in the tumor tissue. Overall, combination treatments including tyrosine kinase inhibitors, immunotherapeutic agents and locoregional therapies may yield the strongest results and therefore need to be explored in future trials.

In conclusion, this is the first late-stage study of an oncolytic immunotherapy in HCC patients. Patients enrolled in the TRAVERSE trial had failed prior sorafenib therapy. The study did not meet its primary endpoint of OS improvement. Thus, consistent with the mechanism-of-action of oncolytic immunotherapies – infection of tumors and in situ vaccination – and the data from this and other oncolytic virotherapy studies strongly suggest that oncolytic immunotherapy agents may be best indicated for a more fit patient population, and not treatment-refractory patients.

Materials and methods

Patients

Patients with a histological or clinical diagnosis of advanced HCC who had radiographic progression on or after sorafenib treatment, or who were intolerant to sorafenib were eligible. Clinical diagnosis was based on EASL-EORTC guidelines .45 Patients were required to have at least one tumor in the liver amendable to IT injection and measurable by modified RECIST .46 Other eligibility criteria included liver function of Child-Pugh Class A or B7 (without ascites), an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) ≤2, and adequate hematologic, hepatic and renal function.

All patients provided written informed consent before study enrollment. The study was approved by the institutional review board or ethics committee at each center and complied with the provisions of the Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki and local laws.

Study design and treatment

Patients were randomly assigned (2:1) to receive Pexa-Vec plus BSC or BSC alone. Patients were stratified based on sorafenib discontinuation (progression vs. intolerance), extra-hepatic spread (yes vs. no), and region (Asian vs. non-Asian). Patients randomized to Pexa-Vec received doses of 109 plaque forming units (pfu) intravenously (IV) on day 1 followed by up to 5 IT treatments at day 8 and Week 3, 6, 12 and 18. Treatment was discontinued either due to the occurrence of both centrally confirmed radiologic progression, based on modified RECIST for HCC and site-determined symptomatic progression, as defined by the ECOG scale and/or the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Hepatobiliary Symptom Index 8 (FHSI-8) questionnaire or to clinical and symptomatic deterioration suggestive for progressive disease. Blinding of the study was not feasible due to the ethics/risk/benefit associated with the sham intratumoral injection. Changes to the modified RECIST for HCC were implemented to reflect the unique mechanism-of-action of Pexa-Vec. This included confirmation of progression, to avoid premature discontinuation of therapy in patients with possible pseudoprogression, as implemented for other immunotherapy agents .47 Primary liver tumors as well as extrahepatic tumors were tracked as the target or non-target lesions.

Assessments

The primary endpoint was OS and secondary endpoints included time to progression (TTP), overall response rate (ORR), disease control rate (DCR) as assessed by mRECIST for HCC, time to symptomatic progression (TSP), safety, tolerability and quality of life (QoL). Tumor measurements were performed every 6 weeks during treatment by contrast-enhanced, dual-phase computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Confirmatory assessments were performed at consecutive imaging after the initial demonstration of the response. Assessments were performed locally by investigators and reviewed centrally by a blinded independent radiologic review committee. Results for TPP, ORR, and DCR were based on this central review. Safety assessments in patients who received at least one dose of study therapy included adverse events (AEs) and clinical laboratory tests (National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events [CTCAE], version 4.03).

Viral genome quantitation by qPCR

The concentration of viral DNA in blood was assessed over time using a quantitative Real-time PCR assay validated for clinical sample testing. Samples were collected before treatment on day 1, and on days 15, 22 (before the second treatment), and 29. Amplification was performed using the “Multicode RTx®” technology (Luminex Corp. Madison, WI) together with a forward primer (TAC.GTC.CTA.TGG.ATG.TGC.ACC) and reverse primer (TAG.TGC.TCT.ATA.CTC.ATA.CGC.TT), which specifically amplify JX-594 viral DNA by binding to the viral DNA sequence and a transgene sequence, respectively. The assay was demonstrated to have good accuracy, precision, and linearity for clinical sample testing. Sensitivity of the assay for testing whole blood and rectal swab samples was the following: LOD of 78 copies/mL and LOQ of 150 copies/mL for whole blood samples and 177 copies/mL and 450 copies/mL for rectal swabs.

Shedding analysis by PFU plaque assay

Shedding was assessed by collecting throat swab and urine samples before treatment on days 1 (Baseline) and 8 and on days 15, 22, and 29. Pustules were swabbed over the outlying skin when they arose, typically within 1 week after the first IV infusion. Throat and pustule swabs were placed in 3 mL of Becton Dickinson Universal Viral Transport Media (BDUM), vortexed and frozen until testing, whereas virus from urine or plasma samples was recovered by centrifugation and resuspended in Tris buffer prior to testing. The plaque assay was demonstrated to have suitable accuracy, precision, and linearity for clinical sample testing and to have a range of 20–4,000 PFU/mL. Infectious viral units of JX-594 were detected as plaques three days after seeding virus on a monolayer of U-2 OS cells. Plaques of the recombinant virus that expressed E. coli β-galactosidase were visualized by X-gal staining (5-bromo-4-chloro-indolyl-beta-D-galactopyranoside) in agarose solution, which renders plaques blue if β-galactosidase is expressed.

Elispot analysis of T-cell responses to viral and tumor antigens

Cellular immunity for each patient was assessed by Elispot on PBMCs from blood samples taken prior to treatment and on week 6, week 12, or the completion of the study. ELISPOT analysis was performed using whole antigen, rather than HLA-restricted peptides, for stimulation. This source of antigen allowed for the induction of immune responses from all patients irrespective of haplotype. Briefly, PBMCs from patients were stimulated by pulsing 1 × 106 cells/mL with either a Vaccinia/B-gal pepmix pool (LPT Laboratories) or a tumor-associated antigen pepmix pool (LPT Laboratories), consisting of libraries of overlapping peptides specific for each antigen. A subset of PBMCs treated with the Vaccinia/B-gal pepmix pool (seven patients) was also treated with a HCV pepmix pool (LPT Laboratories). The pulsed cells were expanded by culturing in CTL medium for at least 7 days in the presence of IL-17 (10ng/mL final concentration) and IL-15 (5 ng/mL final concentration). Cells were then harvested and seeded on 12-well plates coated with antibodies to interferon-gamma. Specificity to beta-galactosidase, vaccinia, HCV, and tumor antigens was tested in duplicate by challenging cells with individual pepmixes of overlapping peptides (1 pg/mL final concentration). Each plate included a negative (medium-alone) control. After overnight incubation, plates were developed and spot-forming cells (SFC) expressing interferon-gamma were enumerated on a plate reader using ImmunoSpot Software (Cellular Technology Ltd.). The frequency of T cells specific to each antigen was expressed as SFC per input cell number. A positive response was defined as a signal of at least 30 SFC/2x105 cells and at least 2 times the magnitude of the negative control.

Assay for immunogenicity

Serum samples from patients treated with JX-594 were tested for antibodies to beta-galactosidase. Detection was performed with a GLP-validated electrochemiluminescence (ECL) immunoassay utilizing the Meso Scale Discovery (MSD) platform. Briefly, serum samples were diluted 1:25 in Diluent/Block buffer and loaded on MSD plates coated with human beta-galactosidase (Sigma-Aldrich) after which 500 pg/mL biotin labeled goat anti-human kappa and goat anti-human gamma antibodies (Bethyl Laboratories, Inc.) was bound. The plates were then incubated with ruthenium labeled (Sulfo-Tag) Streptavidin (1.0 µg/mL) followed by development with a tripropylamine (TPA)-containing read buffer (Mesoscale) and measurement of the ECL signal with a MSD Sector Imager 2400 (Meso Scale Discovery®, Cat. #R92TC-2). The positive control, rabbit anti-human beta-galactosidase (Lifespan Biosciences), was loaded on each plate at 200 ng/mL (LPC) and 1000 ng/mL (HPC) in 4% normal human serum. The negative control on each plate was pooled healthy serum. The plates also included wells coated with Human IgG (R&D Systems), Human IgM (Rockland), and Human IgA (Rockland) as binding controls.

Cut point and end point titer determination

Samples that tested positive in a screening step were tested in a confirmatory assay to identify true positives by assessing the specificity of the signal through competition with soluble beta-galactosidase. Positive signals were defined using a statistically determined, study-specific screening and confirmatory cutpoints calculated from background ECL signals of 110 patients' Day 1 predose samples. The screening cutpoint CP was set to a theoretical 5% false-positive rate (95% confidence Interval) and the confirmatory step CP was set to a theoretical 0.1% false-positive rate (99.9% confidence interval).48 To calculate the CP values, the data was transformed to Log (base 10) and assessed for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test. After removal of outliers, a non-parametric analysis was used to calculate the CP for the screening step, whereas a parametric analysis was used to calculate the CP for the confirmatory step. The relative level of antibodies in samples was expressed as end point titer (EPT), defined as the reciprocal of the last dilution above the CP (set in this study at twice the Negative Control mean signal).

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Jennerex Biotherapeutics Inc., San Francisco, USA (now Sillajen Biotherapeutics) and Transgene S.A., Illkirch-Graffenstaden, France.

Authors’ Contributions

concept and design: RL, DHK, CJB, JMB, MHo, JML, ML, MHe; experiment execution JH, HCL, WYT, SWP, YC, HJY, KSB, AB, GU, DJ, LR, MC, AK, HM, HW, PM, OE, FH, JFB, MM, OR; experiment monitoring/supervision: AML. CMR TH, LL, JMB, MHo, NS; data analysis and interpretation: ND, AML, MHe, CJB, FF, JMB, JML, Mho, MM.

Disclosures

CJB, JMB, AP, DS, BM, NG, ND, DHK are employees of Sillajen Biotherapeutics Inc.; MHo, NS, ML, JML, and MHe are employees of Transgene S.A. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website.

References

- 1.GLOBOCAN Estimated Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide in 2012; 2012. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-11-11-0999-PDN [DOI]

- 2.El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1264. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilhelm SM, Carter C, Tang L, et al. BAY 43-9006 exhibits broad spectrum oral antitumor activity and targets the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway and receptor tyrosine kinases involved in tumor progression and angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7099–7109. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilhelm SM, Adnane L, Newell P, Villanueva A, Llovet JM, Lynch M. Preclinical overview of sorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor that targets both Raf and VEGF and PDGF receptor tyrosine kinase signaling. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:3129–3140. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018;391:1163–1173. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30207-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378–390. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:25–34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lencioni R, Kudo M, Ye SL, et al. First interim analysis of the GIDEON (Global Investigation of therapeutic decisions in hepatocellular carcinoma and of its treatment with sorafeNib) non-interventional study. Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66:675–683. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2012.02940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lencioni R. New data supporting modified RECIST (mRECIST) for hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:1312–1314. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Llovet JM, Di Bisceglie AM, Bruix J, et al. Design and endpoints of clinical trials in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:698–711. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kang YK, Yau T, Park JW, et al. Randomized phase II study of axitinib versus placebo plus best supportive care in second-line treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:2457–2463. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Llovet JM, Decaens T, Raoul JL, et al. Brivanib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma who were intolerant to Sorafenib or for whom Sorafenib failed: results from the randomized phase III BRISK-PS study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3509. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu AX, Park JO, Ryoo BY, et al. Ramucirumab versus placebo as second-line treatment in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma following first-line therapy with sorafenib (REACH): a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:859–870. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abou-Alfa GK, Meyer T, Cheng AL, et al. Cabozantinib in patients with advanced and progressing hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:54–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1717002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruix J, Qin SK, Merle P, et al. Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:56–66. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32453-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El-Khoueiry AB, Sangro B, Yau T, et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): an open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2492–2502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31046-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu AX, Finn RS, Edeline J, et al. Pembrolizumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma previously treated with sorafenib (KEYNOTE-224): a non-randomised, open-label phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:940–952. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30351-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu AX, Kang YK, Yen CJ, et al. Ramucirumab after sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma and increased alpha-fetoprotein concentrations (REACH-2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:282–296. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30937-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finn RS, Chan SL, Zhu AX, et al. KEYNOTE-240: randomized phase III study of pembrolizumab versus best supportive care for second-line advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(4_suppl):TPS503-TPS503. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bell J, McFadden G. Viruses for tumor therapy. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15:260–265. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Russell SJ, Peng KW, Bell JC. Oncolytic virotherapy. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:658–670. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirn DH, Thorne SH. Targeted and armed oncolytic poxviruses: a novel multi-mechanistic therapeutic class for cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:64–71. doi: 10.1038/nrc2545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moehler M, Goepfert K, Heinrich B, Breitbach CJ, Delic M, Galle PR, Rommelaere J. Oncolytic virotherapy as emerging immunotherapeutic modality: potential of parvovirus h-1. Front Oncol. 2014;4:92. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lichty BD, Breitbach CJ, Stojdl DF, Bell JC. Going viral with cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:559–567. doi: 10.1038/nrc3770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim JH, Oh JY, Park BH, et al. Systemic armed oncolytic and immunologic therapy for cancer with JX-594, a targeted poxvirus expressing GM-CSF. Mol Ther. 2006;14:361–370. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parato KA, Breitbach CJ, Le Boeuf F, et al. The oncolytic poxvirus JX-594 selectively replicates in and destroys cancer cells driven by genetic pathways commonly activated in cancers. Mol Ther. 2012 Apr;20(4):749–758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Breitbach CJ, Arulanandam R, De Silva N, et al. Oncolytic vaccinia virus disrupts tumor-associated vasculature in humans. Cancer Res. 2013;73:1265–1275. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heo J, Reid T, Ruo L, et al. Randomized dose-finding clinical trial of oncolytic immunotherapeutic vaccinia JX-594 in liver cancer. Nat Med. 2013;19:329–336. doi: 10.1038/nm.3089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andtbacka RH, Kaufman HL, Collichio F, et al. Talimogene laherparepvec improves durable response rate in patients with advanced melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2780–2788. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.3377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen HS, Qin LL, Cong X, et al. Expression of tumor-specific cancer/testis antigens in hepatocellular carcinoma. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2003;11:145–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao L, Mou DC, Leng XS, Peng J-R, Wang W-X, Huang L, Li S, Zhu J-Y. Expression of cancer-testis antigens in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:2034–2038. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i14.2034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao X, Ogunwobi OO, Liu C, Gaetano C. Survivin inhibition is critical for Bcl-2 inhibitor-induced apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21980. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Worns MA, Galle PR. HCC therapies–lessons learned. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11:447–452. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2014.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ringelhan M, Pfister D, O’Connor T, Pikarsky E, Heikenwalder M. The immunology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Immunol. 2018;19:222–232. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0044-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sia D, Jiao Y, Martinez-Quetglas I, et al. Identification of an immune-specific class of hepatocellular carcinoma, based on molecular features. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:812–826. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Foerster F, Hess M, Gerhold-Ay A, Marquardt JU, Becker D, Galle PR, Schuppan D, Binder H, Bockamp E. The immune contexture of hepatocellular carcinoma predicts clinical outcome. Sci Rep. 2018;8. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21937-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu TC, Hwang T, Park BH, Bell J, Kirn DH. The targeted oncolytic poxvirus JX-594 demonstrates antitumoral, antivascular, and anti-HBV activities in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1637–1642. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu AX, Kudo M, Assenat E, et al. Effect of everolimus on survival in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma after failure of sorafenib: the EVOLVE-1 randomized clinical trial. Jama. 2014;312:57–67. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.7189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moehler MH, Zeidler M, Wilsberg V, Cornelis JJ, Woelfel T, Rommelaere J, Galle PR, Heike M. Parvovirus H-1-induced tumor cell death enhances human immune response in vitro via increased phagocytosis, maturation, and cross-presentation by dendritic cells. Hum Gene Ther. 2005;16:996–1005. doi: 10.1089/hum.2005.16.996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sieben M, Schafer P, Dinsart C, Galle PR, Moehler M. Activation of the human immune system via toll-like receptors by the oncolytic parvovirus H-1. Int J Cancer. 2013;132:2548–2556. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim MK, Breitbach CJ, Moon A, et al. Oncolytic and immunotherapeutic vaccinia induces antibody-mediated complement-dependent cancer cell lysis in humans. Sci Transl Med. 2013;(5):185ra163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moehler M, Delic M, Goepfert K, et al. Immunotherapy in gastrointestinal cancer: recent results, current studies and future perspectives. Eur J Cancer. 2016;59:160–170. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Duffy AG, Ulahannan SV, Makorova-Rusher O, et al. Tremelimumab in combination with ablation in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2017;66:545–551. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sangro B, Gomez-Martin C, de la Mata M, et al. A clinical trial of CTLA-4 blockade with tremelimumab in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2013;59:81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.European Association for Study of L, European Organisation for R, Treatment of C EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:599–641. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lencioni R, Llovet JM. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30:52–60. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jd Wolchok, Hoos A, O’Day S, et al. Guidelines for the evaluation of immune therapy activity in solid tumors: immune-related response criteria. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:7412–7420. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koren E, Smith HW, Shores E, et al. Recommendations on risk-based strategies for detection and characterization of antibodies against biotechnology products. J Immunol Methods. 2008;333:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.