ABSTRACT

Background: Intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) is the gold standard immunologic agent for treating patients with high-grade non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC). Nevertheless, relapse rates remain high and BCG unresponsive NMIBC often requires bladder removal. Preclinical data suggest that priming with percutaneous BCG vaccine could improve response to intravesical BCG.

Methods: A single-arm trial (NCT02326168) was performed to study the safety, immunogenicity, and preliminary efficacy of priming. Percutaneous BCG was given 21 days prior to intravesical BCG instillation in patients (n = 13) with high-risk NMIBC. Immune responses were monitored and compared to a sequentially enrolled cohort of nine control patients receiving only intravesical BCG. The effect of BCG on natural killer (NK) and γδ T cell in vitro cytotoxicity was tested. γδ T cell subsets were determined by T cell receptor gene expression with NanoString.

Results: Priming was well tolerated and caused no grade ≥3 adverse events. The 3-month disease-free rate for prime patients was 85% (target goal ≥ 75%). Priming boosted BCG-specific immunity at 3 months and increased the activation status of in vitro expanded circulating NK and γδ T cells and their cytotoxicity against bladder cancer cells through receptor NKG2D. BCG enhanced the cytotoxicity of NK and γδ T cells against K562, RT4, and UM-UC6 but not against T24, UM-UC-3, or UM-UC-14 cells. Infiltrating γδ T cell subsets identified in the bladder includes γ9δ2 and γ8δ2.

Conclusions: BCG priming is safe and tolerable. Poor sensitivity to NK and γδ T cell cytotoxicity by some bladder tumors represents a potential BCG-resistance mechanism.

KEYWORDS: Priming, BCG, vaccine, bladder cancer, clinical trial

Introduction

Bladder cancer tends to be a multifocal and metachronous disease process of the urothelium. Treatment paradigms are based on precise staging and grading of sampled tumor tissue, which vary from low-grade non-invasive tumors to high-grade tumors invading the lamina propria (T1) or muscular propria (T2) of the urinary bladder. For high-grade muscle-invasive bladder cancer, standard management involves extirpation of the entire organ (cystectomy) and urinary diversion. Conversely, high-grade but non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) is treated with local tumor resection followed by intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) immunotherapy. BCG is one of the first FDA-approved cancer immune therapies, indicated for treatment and prophylaxis of carcinoma in situ (CIS) of the urinary bladder and for prophylaxis of primary or recurrent stage Ta and/or T1 papillary tumors following endoscopic tumor removal.1 While BCG therapy is effective for eradicating CIS and reducing tumor recurrence,2,3 response is heterogeneous and tumor recurrence and disease progression occurs in approximately 50% and 20% of the treated patients, respectively.4,5 Thus, there is a need to improve response rates to BCG and/or find alternative approaches.

Following exposure to BCG, T cells proliferate in response to antigenic stimuli specific to proteins expressed by BCG giving rise to sensitized BCG-specific lymphocytes.6,7 It was demonstrated that BCG-specific immune responses are important for BCG treatment efficacy and that boosting BCG immunity via a percutaneous BCG vaccine prior to intravesical BCG, significantly improved survival in a mouse model of bladder cancer.8 In patients previously exposed to BCG, subsequent exposure to antigen with injection of PPD, stimulates BCG-sensitized T cells, evoking a local hypersensitivity reaction at the site of the PPD injection. Termed delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions, these are maximal at 48–72 h and are characterized by induration (palpable raised and firm area) due to cellular infiltration. PPD conversion (negative at baseline converted to positive after BCG therapy) in patients with bladder cancer undergoing BCG instillations is observed in 35–51% of the patients and is associated with decreased relapse rates following intravesical BCG therapy.9–11 Among a cohort of patients with NMIBC, previous exposure to percutaneous BCG and persisting immune memory, marked by a PPD reaction, was associated with a decreased relapse rate following intravesical BCG therapy.8 Further, PPD skin test, itself, was shown to improve anti-tumor responses to BCG.12 These findings suggest that immune priming with BCG vaccine prior to intravesical BCG instillation can improve BCG therapy responses and facilitate antitumor immunity in the bladder.

Previous clinical studies examined the combined use of intravesical and percutaneous (or scarification) routes, showing no definitive improvement in clinical response over intravesical therapy alone.13–15 In these studies, however, priming was not performed as the BCG vaccine was given contemporaneous with intravesical treatment. Priming with percutaneous BCG aims to elicit systemic BCG-specific immunity before the start of intravesical therapy and leads to a robust innate and cell-mediated immune response toward BCG in the bladder8, but this approach has not been tested in humans. BCG treatment induces a dramatic increase in multiple urinary cytokines following BCG instillation.16 Repeated intravesical BCG instillations lead to progressively higher urinary cytokine levels,16,17 a phenomenon akin to memory responses that have been termed tissue conditioning.16 To study the safety, immune effects, tissue conditioning, and potential efficacy of BCG priming, we conducted a single-arm clinical trial of percutaneous BCG followed 21 days later by intravesical BCG in patients with high-grade NMIBC. Immune effects and survival rates were compared to a cohort of control patients receiving intravesical BCG without priming.

Results

Patient characteristics

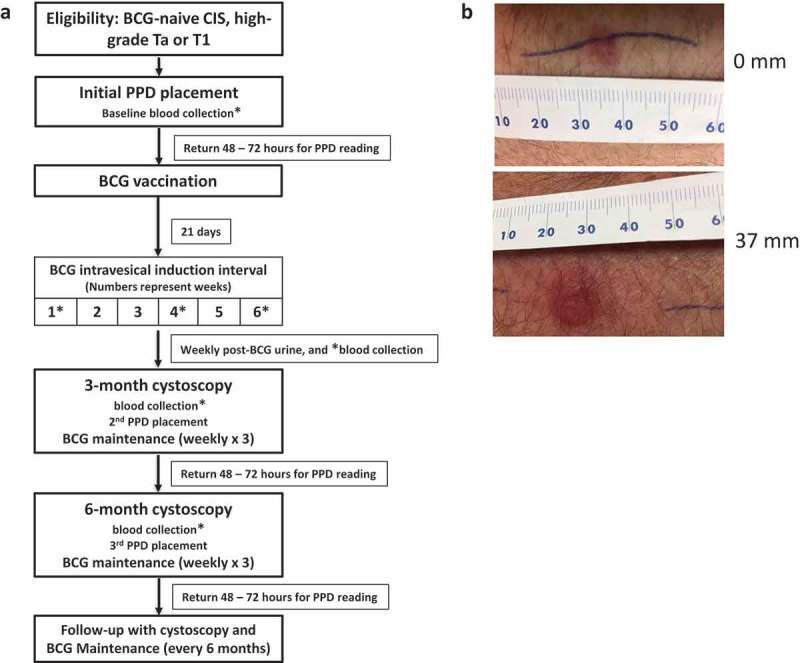

From February 2014 to February 2015, 14 patients were enrolled of which 13 were treated with percutaneous BCG plus intravesical BCG (prime patients) following trial schema shown in Figure 1A. Then, from August 2015 to January 2016, clinical data and materials were prospectively collected on nine control patients treated with intravesical BCG without percutaneous BCG. Most patients were men (82%) with no significant differences between prime and control patients observed for age, gender, race, ethnicity, tumor grade, tumor stage, or presence of CIS (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Trial Schema and results of PPD reading in prime patients. (a) Eligible patients were BCG naïve, PPD negative, and had high-grade non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC). BCG vaccination was administered percutaneously and 21 days later, patients were given standard-of-care intravesical BCG instillation. (b) Examples of PPD response. The “ballpoint pen” technique was used to measure response at 48–72 after PPD placement. Shown are the examples of a patient with negative PPD response (induration < 10 mm) and positive PPD response (induration ≥ 10 mm).

Table 1.

Demographics, PPD responses, and clinical outcomes of patients.

| Prime patients | Tumor grade & stage |

Gender | Age | Race/Ethnicity | PPD induration 3 mo 6 mo |

Recurrent pathology in bladder |

Time to recurrence in bladder (months) |

Time to progression in bladder (months) |

Follow up (months) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | HG Ta | M | 79 | W/NH | N/A | 6 mm | – | – | – | 44.0 |

| 2 | HG T1 | M | 91 | W/H | 12 mm | 12 mm | – * | – | – | 46.8 |

| 3 | CIS, LG Ta, HG Ta | M | 77 | W/NH | 0 mm | 0 mm | – | – | – | 35.5 |

| 4 | HG Ta | M | 44 | W/NH | 0 mm | 9 mm | – | – | – | 32.6 |

| 5 | HG T1 | M | 79 | W/NH | 0 mm | 15 mm | – | – | – | 38.2 |

| 6 | HG Ta/T1 | M | 74 | W/NH | 0 mm | 37 mm | LG Ta | 3.2 | – | 37.2 |

| 7 | HG Ta | M | 85 | W/NH | 20 mm | – | HG Ta | 7.1 | – | 37.0 |

| 8 | HG Ta/T1 | M | 65 | W/NH | 7 mm | 0 mm | HG Ta | 18.5 | – | 32.3 |

| 9 | HG Ta | M | 74 | W/NH | 30 mm | – | – | – | – | 36.1 |

| 10 | HG T1 | M | 72 | W/NH | 30 mm | – | HG Ta | 3.1 | – | 40.4 |

| 11 | LG Ta, HG Ta | M | 52 | W/NH | 10 mm | – | HG Ta, CIS | 10.8 | – | 36.0 |

| 12 | HG Ta | F | 65 | W/NH | 15 mm | – | – | – | – | 31.3 |

| 13 | HG T1 | F | 78 | W/NH | 20 mm | – | – | – | – | 14.8 |

| Control patients | ||||||||||

| 1 | HG Ta | M | 58 | W/NH | N/A | N/A | – | – | – | 9.4 |

| 2 | LG Ta, HG Ta | M | 75 | W/NH | N/A | N/A | LG Ta, HG Ta | 6.7 | – | 29.2 |

| 3 | HG T1 | F | 83 | W/NH | N/A | N/A | HG T2 | 13.6 | 13.6 | 13.6 |

| 4 | HG Ta | M | 67 | W/NH | N/A | N/A | – | – | – | 14.0 |

| 5 | HG T1 | M | 81 | W/NH | N/A | N/A | – | – | – | 26.1 |

| 6 | HG Ta/T1 | F | 71 | W/NH | N/A | N/A | – | – | –** | 25.1 |

| 7 | HG Ta/T1 | M | 70 | W/H | N/A | N/A | HG T1, HG Ta | 6.1 | 14.4 | 14.4 |

| 8 | LG Ta, HG Ta | M | 82 | W/NH | N/A | N/A | HG T1 | 2.5 | – | 2.5 |

| 9 | CIS, HG Ta | M | 73 | W/H | N/A | N/A | – | – | – | 21.4 |

* Upper track recurrence at 23.9 months but no recurrence in lower track or bladder up to date.

** Develops muscle invasive tumor of ureter at 20.7 months. W, white; H, Hispanic; NH, non-Hispanic; HG, high-grade; LG, low-grade; CIS, Carcinoma in situ. N/A, not available.

Safety and tolerability

Among prime patients, mild symptoms were common with nine (69%) patients reporting mild irritative voiding symptoms (urinary frequency, dysuria, or urgency) at some point during intravesical therapy and 11 (85%) reporting constitutional symptoms [(fever, weakness, fatigue, or myalgia), Supplemental Table 1]. No significant trend in symptoms was observed for a cumulative exposure to combined therapy. Grade 2 adverse events included hematuria requiring temporary discontinuation of treatment, placement of urethral catheter, and irrigation of bladder. No patients experienced grade ≥ 3 adverse events. No serious adverse events were noted from the site of percutaneous vaccination. Expected local reactions at BCG percutaneous site included redness, minimal pain/swelling at the injection site, and papules with no ulcers and no drainage. All lesions were healed without scarring by 3 months post vaccination. Priming caused no significant CD4+, CD8+, and γδ T cell lymphopenia (Supplemental Figure S1).

Efficacy

Among 14 patients enrolled, 11 were free of disease at 3 months (78.6%), including 11 of 13 (85%) patients who received percutaneous BCG. Among nine control patients, eight (89%) were free of disease at 3 months. The mean follow-up time was 35.6 months and 17.3 months for prime and control groups, respectively (Table 1). A total of five (38%) prime patients and four (44%) control patients experienced bladder tumor recurrences. The recurrence-free survival (RFS) was similar between prime and control populations (HR = 1.39, 95% CI = 0.36 to 5.41, Supplemental Figure S2). None of the prime patients progressed to higher disease stage in bladder compared to two (22%) in control patients (Table 1).

PPD conversion

PPD responses were monitored in prime patients with the expectation that priming would improve the historic PPD conversion rate. All prime patients receiving percutaneous BCG were PPD negative at baseline. At 3 months, seven (53.8%) prime patients successfully converted to PPD positive and an additional two converted at 6 months for a total conversion rate of 9/13 (69%) (Figure 1B, Table 1). BCG-related side effects were similar between PPD converters compared to PPD non-converters.

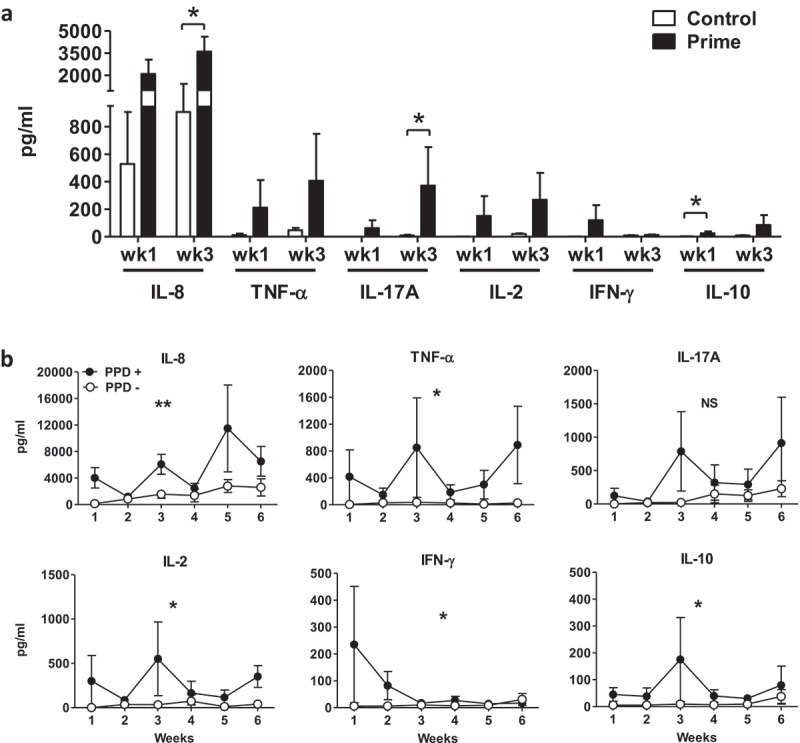

Priming boosts BCG-induced urinary cytokines correlating with PPD conversion

Priming was associated with an accelerated time to tissue conditioning evidenced by an increase in urinary cytokine levels at week 3 in prime compared to control patients (Figure 2A). Among prime patients, those who PPD converted by 3 months following BCG therapy exhibited an increase in several urinary cytokine responses compared to PPD non-converters at 3 months (Figure 2B). These findings support an increase in local (bladder) inflammation induced by priming and correlated with a systemic immune response to BCG.

Figure 2.

BCG-induced urinary cytokines during intravesical BCG therapy. Urine supernatant collected from prime patients 4–6 h after BCG instillation was measured for cytokine level by Luminex Multi-plex assay from all samples available. Cytokine concentrations were corrected by individual urinary creatinine concentrations and normalized to 100 mg/dl creatinine for data deduction and plotting as mean ± SEM. Urinary cytokines compared at (a) week 1 and 3 for control versus prime patients and at (b) weeks 1–6 for PPD conversion versus PPD non-conversion patients by 3 months. Filled symbols, prime patients, n = 13; open symbols, control patients, n = 5. Comparison between control and prime groups was performed using Mann–Whitney test. Filled circles, PPD+, 3-month PPD converted patients, n = 7; open circles, PPD-, PPD non-converted patients by 3 months, n = 6. Area under curves (AUCs) were compared between groups using Mann–Whitney test. * p < .05, **, Pp< .01, NS, not significant.

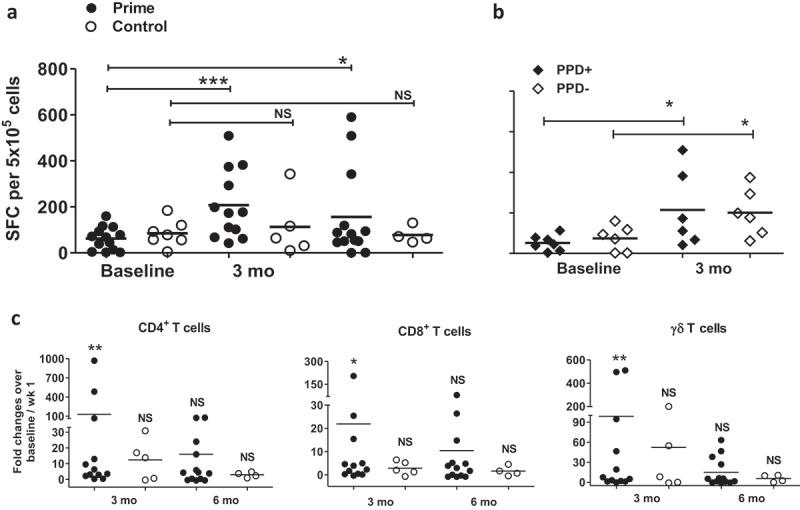

Priming increases IFN-γ producing effector T cells directly ex vivo

To monitor the frequency of circulating BCG-specific T cells, we measured IFN-γ ELISPOT responses after short-term (24 h) stimulation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) with live BCG or BCG-specific antigen Ag85b. At baseline, BCG-specific T cells were detected at low but detectable numbers in most patients (Supplemental Figures S3A-C; Figure 3A), likely due to prior exposure to non-tuberculosis mycobacteria, which share common antigens to BCG. An increase in BCG-specific T cells at 3 months was observed in patients who PPD converted as well as those who did not PPD convert at 3 months (Figure 3B). This suggests that PPD conversion may not precisely reflect the development of BCG-specific immunity in these patients. However, two patients who were PPD negative at 3 months were found to be reactive at 6 months, indicating a delayed conversion in some patients. In prime patients, significant increases in BCG-specific T cells were observed as early as the fourth week of BCG instillation (Supplemental Figures S3C) and levels remained elevated for at least 3 months (Figure 3A, filled circles). However, no significant increase of BCG-specific T cells was detected in control patients at either 3 or 6 months (Figure 3A, open circles) or in Ag85b response at 3-month fold changes over baseline between prime and control patients (Supplemental Figure 3D). These findings suggest that priming increases BCG-specific immunity during intravesical BCG treatment of bladder cancer.

Figure 3.

Priming boosts BCG-specific immunity and the simultaneous proliferation and effector function of memory T cells in circulation. ELISPOT assay in response to live BCG was conducted from PBMCs collected from patients at baseline (prior to BCG induction), 3 and 6 months. Response from all available samples is compared for: (a) prime (filled circles, n = 13) versus control patients (open circle, n = 7), or (b) prime patients who PPD converted by 3 months (filled diamonds, n = 7) versus who did not PPD convert (open diamonds, n = 6). SFC, spot-forming cells represent the absolute number of BCG-specific IFN-γ-producing PBMCs. (c) 1 × 106 patient PBMCs labeled with CFSE were cultured with the presence of live BCG for 7 days, then incubated with the cocktail of PMA, ionomycin and Golgi blocker for 5 h, prior to cell-surface staining for CD4, CD8, and γδ TCR markers, followed by intracellular staining for IFN-γ. Absolute numbers (AN) of proliferated memory T cell subsets (defined as both CFSElo and IFN-γ+) were calculated by multiplying total viable cells by the percentage of T cell subset acquired from flow cytometry. Shown are AN of proliferated memory CD4+, CD8+, and γδ T cells from circulation in response to live BCG at 3 or 6 months over baseline for PBMCs from prime (filled circles, n = 13) and control patients (open circles, n = 7). Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test was performed for each group at either 3-month or 6-month in comparison with baseline. *, Pp< .05, **, p < .01, NS, not significant.

Priming increases IFN-γ producing memory T cells capable of BCG-specific expansion

Durable immunity requires memory T cells with long-term homeostatic proliferation capacity that can both expand and produce effector functions in response to antigenic challenges.18–20 To assess the relative numbers of BCG-specific T cells with the capacity for both expansion and cytokine production, we used CFSE dilution to track lymphoproliferation coupled with intracellular staining to detect IFN-γ production (Supplemental Figure S4A) as described.21 As expected, we observed higher numbers of proliferating IFN-γ producing T cells in PPD converted compared to PPD unconverted prime patients (Supplemental Figure S4B-D). At 3 months after priming, the number of proliferating IFN-γ producing T cells, including γδ T cells, was significantly increased (Figure 3C). This effect of priming on γδ T cells suggests induction of a memory-like γδ T cell similar to the phenotype we reported in BCG vaccinated populations.22 At 6 months from baseline, however, the number of these cells was no longer increased, indicating that the effects of priming on long-term homeostatic proliferating memory T cells may wane over time. Taken together, the results indicate that priming enhances long-term BCG-specific memory T cell responses, but responses are transient and appear to plateau at 3 months following priming.

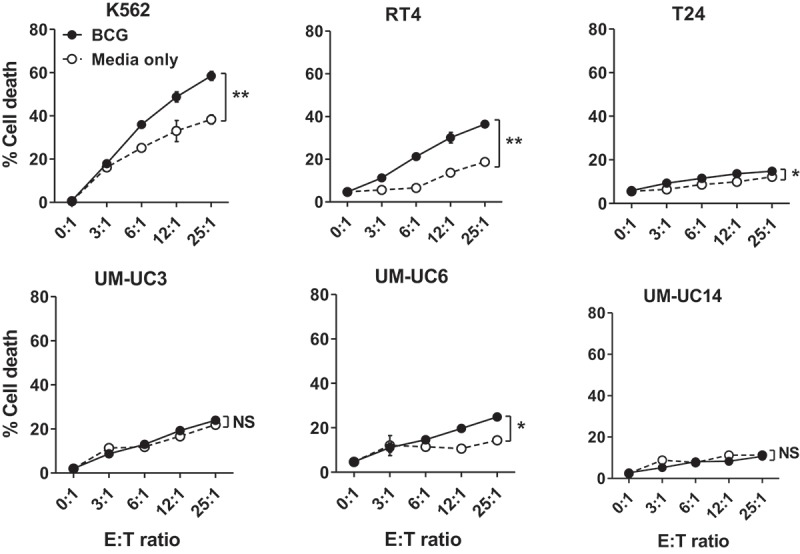

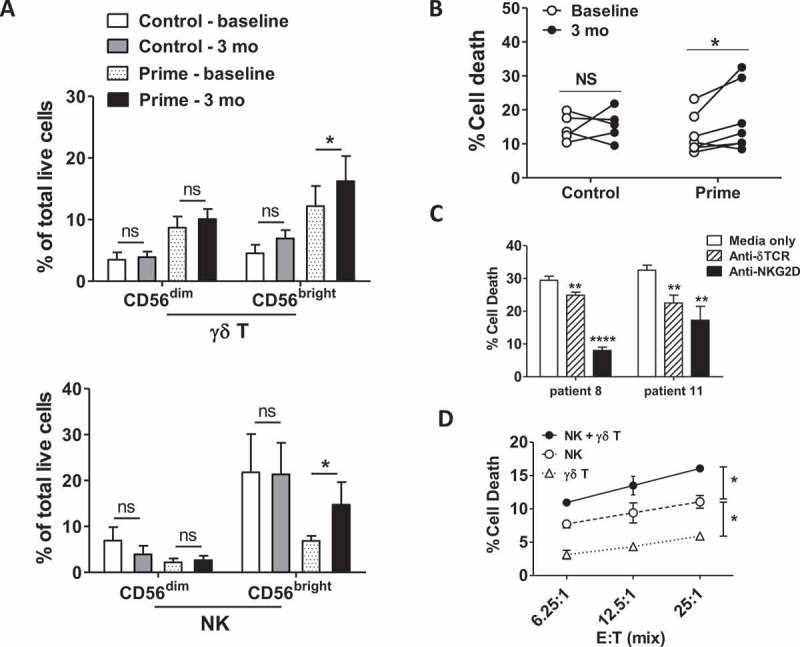

Priming increases NKG2D-dependent anti-tumor cytotoxicity

Because priming induced functional memory changes in γδ T cells (Figure 3B, right graph), we hypothesized that priming could also boost γδ T cell cytotoxic function. Priming did not significantly affect the percentage of circulating peripheral blood γδ T cells (Supplemental Figure S1). Further, we found no significant differences in the activation status of circulating γδ T cells between prime and control patients based on surface expression of activation markers (CD56 or CD69) and co-stimulatory receptors (NKG2D or 4-1BB) (data not shown). To examine function, γδ T cells were expanded from PBMCs using IPP and IL-2 ± live BCG as we reported.23 After 14 days in culture, γδ T cell frequency usually increased in all culture conditions with live cells containing 30–60% γδ T cells and 15–30% NK cells and vary among different patients’ PBMCs (Supplemental Figure S5). We confirmed that expanding cells in the presence of BCG improved cytotoxicity against NK-sensitive K562 cells as reported24,25 and against human bladder cancer cells (Figure 4). Notably, sensitivity of in vitro BCG-induced cytotoxicity was variable among different bladder cancer cell lines with RT4 exhibiting the most sensitivity whereas UM-UC3 was completely resistant to BCG-induced cytotoxicity (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

BCG increases the cytotoxicity of innate effector cells expanded in vitro. PBMCs from a patient with BC were cultured with IPP and human IL-2 for 14 days with or without the presence of live BCG (added on day 0 and day 7 of culture at MOI = 0.1) to expand innate effector cells. Then, these cells (effector) were co-cultured with CFSE-labeled human leukemia K562 cells or human bladder cancer cells (target) for 5 h at effector: target (E: T) ratio 0: 1 and up to 25: 1, followed by staining of fixable viability dye to analyze percentage cell death of target cells on flow cytometer. Results plotted as mean ± SEM based on assay replicates and groups (BCG vs. media only) were compared with two-way ANOVA, **, p < .001, *, Pp< .01, NS, not significant.

Comparing expanded PBMCs at baseline versus 3 months showed that priming notably increased the numbers of activated CD56bright γδ T and NK cells (Figure 5A). In agreement with this phenotypic data, expanded γδ T and NK cell mixture from PBMCs collected 3 months after priming killed RT4 human bladder cancer cells in vitro significantly better than those collected at baseline whereas expanded cells from control patients exhibited no significant increase in RT4 killing (Figure 5B). γδ T cells recognize tumor-associated antigens via δ T cell receptor (TCR) and/or NKG2D receptors26 and NKG2D is also an important NK cell activating the receptor.27,28 Using blocking antibodies, we found that γδ T and NK cell killing of RT4 cells occurred primarily through NKG2D and less through δ TCR (Figure 5C). To distinguish individual contributions, we sorted γδ T and NK cells by FACS after PBMC expansion and compared their RT4 killing to the unsorted cell mixture. NK cells killed RT4 cells better than γδ T cells, but killing was best in the unsorted mixture (Figure 5D), corroborating published data showing that human γδ T cells promote the cytolytic function of NK cells.29 In summary, although priming had no discernable effects on the activation status of γδ T and NK cells from unexpanded PBMCs, priming significantly increased activation status and RT4 cytotoxicity of γδ T and NK cells expanded in vitro that was dependent on NKG2D.

Figure 5.

BCG priming improves BC cytotoxicity of innate effector cells expanded in vitro. PBMCs were cultured in vitro with IPP and IL-2 to expand innate effector cells before testing cytotoxicity as in Figure 4. In parallel, percentage and expression of activation markers of γδ T cells or NK cells were measured by flow cytometry. Shown are (a) percentage of CD56-expressing population among γδ T and NK cells after in vitro expansion, as well as (b) percentage of cell death in target cells after cytotoxic killing by effector cells generated in vitro from PBMCs of control or prime patients at baseline versus 3 months post BCG treatment for patients with adequate samples remaining for analysis (prime, n = 7; control, n = 5). Mean ± SEM. Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test; *, p < .05; NS, not significant. Bonferroni corrections were applied to p value if multiple comparisons were used. (c) Innate effector cells from prime patients were pre-incubated with anti-γδTCR or anti-NKG2D blocking antibody for 45 min prior to cytotoxicity assay against RT4 cells. Shown are representative results from three experiments (prime patient 8 and 11, 3-month PBMCs). Mean ± SEM, unpaired t-test, **, p < .01, ****, p < .0001. (d) Cytotoxicity against RT4 was compared between the unsorted mixture of innate effector cells versus sorted γδ T cells or NK cells. Ratio of sorted γδ T and NK cells versus target RT4 cells are similar to those present in the unsorted mixture. Shown are the representative result from six experiments. two-way ANOVA, *, p < .05.

BCG boosts γ8δ2 and γ9δ2 T cell subsets

γδ T cells exhibit tissue-specific diversification in their TCR repertoire.22 In healthy individuals, BCG vaccination predominately boosts γ9δ2 T cells.22 To determine which γδ T cell subtypes were mostly affected by BCG in bladder cancer patients, we examined gene expression profiles of isolated γδ T cells from peripheral blood and patient-matched bladder tumors. Among circulating γδ T cells, γ8, γ9, and δ2 chains were frequent after BCG treatment whereas δ1 and δ3 chains were rare and not affected by BCG (Supplemental Figure S6A). Notably, there was a higher frequency of γ8 chains in bladder compared to circulation (Supplemental Figure S6B), suggesting γ8δ2 T cells as a potentially unique bladder-specific γδ T cell subset relevant in bladder cancer and BCG responsiveness.

Discussion

This trial demonstrates safety and preliminary efficacy of priming with percutaneous BCG prior to intravesical BCG for patients with NMIBC. No patients experience severe adverse events and clinical reactogenicity to the percutaneous BCG was limited to local skin responses including mild injection site pain and swelling. Further, while constitutional symptoms including myalgia and fatigue were common, all patients were able to complete a minimum of 6 weeks of induction and three cycles of maintenance BCG, showing that priming was tolerable and did not compromise their ability to receive intravesical BCG.

Priming enhanced urinary cytokine responses to intravesical BCG. It is well documented that weekly instillations of BCG lead to a type of bladder tissue conditioning effect evidenced by sequentially rising urinary cytokine and chemokine levels.16,17 The mechanism of this phenomenon is not understood but could be related to increased vascular permeability, development of immunologic memory, or conditioning of innate immune responses. Notably, post-treatment urinary cytokines have been examined in patients with bladder cancer treated with BCG and increased concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines, especially IL-2 and IL-8 are associated with improved long-term clinical response to BCG.30–32 Moreover, monitoring of urinary cytokines has been proposed as a means to identify patients during BCG treatment to guide modification of dose and duration of BCG immunotherapy, or to direct patients to alternative regimens.33 To our knowledge, this is the first evidence showing the correlation between systemic BCG-specific immune responses and local (bladder) BCG-induced cytokine responses. These data are significant because they suggest that BCG-specific immune responses could contribute to bladder tissue conditioning and that systemic immune responses could predict local responses to BCG therapy.

NK and γδ T cells are innate effector lymphocytes important for controlling tumor growth through non-major histocompatibility complex class I restricted mechanisms. These cells have limited TCR diversity and recognize a conserved set of pathogen- or self-encoded antigens or tumor-specific ligands.26–28 We show that priming boosts γδ T cells, which cooperate with NK cells to mediate bladder cancer cytotoxicity. Thus, our data corroborate observations from animal models of bladder cancer showing the requirement of NK and γδ T cells in mediating BCG’s antitumor efficacy.34,35 Although there is evidence showing the requirement for conventional T cells in mediating BCG’s antitumor effects, these data challenge the notion that BCG-specific conventional T cells are the sole mediators of BCG’s antitumor effects.8,36 We speculate that BCG’s antitumor activity also requires induction of innate immunity, including activation of γδ T cells and NK cells. Further, priming could boost intravesical BCG activity by enhancing γδ T cells’ responses, which influence NK cells.

The absence of sustained BCG-specific immunity and dependence on non-classical adaptive immunity for antitumor efficacy could explain the requirement of repeated maintenance BCG to provide durable clinical responses.1 Elucidating these underlying mechanisms of BCG’s antitumor activity is needed to understand the heterogeneity of BCG responsiveness among bladder tumors. Notably, we found variable sensitivity of BCG-induced cytotoxicity among different bladder cancer cell lines: RT4 was the most sensitive and UM-UC3 was the most resistant. Additional research is warranted to determine if the presence of markers of resistance to innate effector cells could identify bladder tumors unlikely to respond to BCG.

Immune responses to BCG in humans are complex involving numerous components of immunity. Also, BCG administration site (percutaneous versus intravesical) could influence subsequent immune responses as we showed recently that routes of BCG administration induce distinct mucosal and systemic immune responses during healthy subject vaccination.37 Therefore, we compared several immune functions induced by percutaneous and intravesical BCG including antigen-specific T cell expansion capacity, IFN-γ secretion, phenotypes of T cells consistent with effector and memory T cell functions, and direct cytotoxic effects of BCG-induced innate effector cells against human bladder cancer cell lines. While BCG priming had no discernable effect on frequency, percentage or surface protein expression assessed of T cell subsets, priming significantly increased BCG-specific immune responses including functional T cells capable of BCG-induced expansion. Importantly, an increased BCG-specific immune response correlates with improved response to BCG.8 Thus, improvement in BCG-specific immunity by priming could boost the efficacy of intravesical BCG. Notably, BCG-specific immune responses waned in most patients after 3 months with some responses returning to baseline levels at 6 months. This phenomenon is remarkably similar to another report,38 showing decreased lymphoproliferative responses toward PPD, BCG antigens, and live BCG over time among patients with bladder cancer receiving only intravesical BCG. Speculations about why this could occur include sequestration of antigen-specific T cells in the bladder after repeated BCG instillations or absence of a classical antigen-specific immune response.

Based on the disease-free rate of 85% at 3 months among prime patients, this first stage of a Simon’s two-stage phase II trial reached its specified objective to warrant proceeding to the second stage. However, the second stage is no longer planned because a phase III trial was recently initiated to test the efficacy of priming (NCT03091660). Although our study found no difference in RFS between the prime and control groups, the study was neither designed nor adequately powered to compare survival outcomes between these groups. While prime patients experienced no grade ≥ 3 adverse events suggesting safety of this approach, it is not possible to determine the effect of priming on BCG-related side effects since tolerability was not systematically collected through patient-reported questionnaires in the control cohort. While the vast majority of persons of this age in the U.S. are PPD negative39 another limitation of our study is that patients in the control group did not undergo routine PPD testing prior to BCG therapy. Moreover, it is possible that PPD testing, which only occurred in the prime patients, could influence subsequent BCG-specific immune responses40,41 and anti-tumor response to BCG,12 as suggested. If shown to be effective, BCG priming will have tremendous value for patients with NMIBC since the BCG vaccine is inexpensive, safe, and easy to administer.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates the safety and tolerability of priming with percutaneous BCG vaccine for patients with high-risk NMIBC undergoing treatment with intravesical BCG. These findings support the testing of BCG priming in a randomized clinical trial. BCG induces significant increases in circulating γδ T cell cytotoxicity, but γδ T cells are tissue specific. Therefore, further study is needed to determine BCG’s effects on bladder-derived γ8δ2 T cells. Tumor resistance to BCG-induced innate effector cytotoxicity could contribute to the lack of therapy response in some patients. Further study is needed to determine if the presence of NK and γδ T cell resistance markers could identify bladder tumors unlikely to respond to BCG.

Materials and methods

Study design and eligibility criteria

A non-randomized, open-label, single-arm trial was conducted following approval by the local institutional review board (IRB# HSC20140005H). This trial was registered retrospectively on 25 December 2014 at http://clinicaltrials.gov as NCT02326168. Eligible patients were 18 years old or older, BCG naïve, PPD negative, recently diagnosed with high-grade NMIBC (CIS, Ta, or T1), and able to provide informed consent. Study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. Patients were required to have adequate marrow function (blood leukocytes > 1,500 cells/µl and platelets > 150,000/µl) within 60 days from signing consent. Patients with a history of muscle-invasive bladder cancer, immunosuppression (e.g., HIV/AIDS), tuberculosis, or prior BCG vaccination were ineligible. A cohort of nine control patients receiving intravesical BCG without percutaneous BCG was prospectively followed under a separate IRB approved protocol (IRB# HSC20120159H) for comparison of immune responses and clinical outcomes to prime patients.

Invasive procedures

The study schema is shown in Figure 1A. PPD (Mantoux/TUBERSOL®) skin tests were performed prior to enrollment and at 3 months in prime patients and repeated at 6 months if the 3-month PPD was negative. At 48–72 h after PPD placement, the “ballpoint pen technique”42,43 (Figure 1B) was used to measure response: “positive” result taken as ≥10 mm maximal diameter of induration. Blood was collected at multiple study time points, including baseline (prior to any BCG), during BCG induction, and at 3 and 6 months from enrollment. Blood was collected into heparin anticoagulated sterile tubes and centrifuged to remove plasma. PBMCs were isolated from the remaining whole blood by Ficoll-Paque (GE Healthcare) centrifugation and cryopreserved at −150°C until analyzed. For all assays, thawed PBMCs were used. Total viable cells in each PBMC sample were determined on the day of the assay using an automatic cell counter (Vi-Cell XR, Beckman Coulter).

Prime patients received a standard World Health Organization adult potency BCG vaccine administered percutaneously in the deltoid region using a sterile multiple puncture device over a 1 x 2-in. area. One vial of TICE® BCG containing 1–8 × 108 colony-forming units (CFU) was reconstituted in sterile saline and 0.2–0.3 ml per patient was administered.

All papillary bladder tumors were resected prior to intravesical BCG administration. Patients with T1 disease underwent restaging transurethral biopsy/resection prior to initiating BCG as per standard-of-care. At 21 days following percutaneous BCG vaccination, prime patients began standard intravesical BCG instillation: 1 vial of TICE® BCG was diluted in 50 ml of sterile saline and instilled into a completely emptied bladder through a urethral catheter with a dwell time of 2 h. BCG induction therapy was given weekly for 6 weeks and maintenance therapy was given in cycles (weekly for 3 weeks) at 3 months, 6 months, and then every 6 months for a total of seven maintenance cycles1 (Figure 1A).

Symptoms, adverse events, and endpoint assessment

Prime patients were monitored in the clinic during BCG instillation. Treating physicians assessed safety and adverse events with history and physical exam before and after BCG instillation. Adverse events were graded according to the National Cancer Institute common toxicity criteria version 4.0. Tolerability was assessed with patient-reported questionnaires (Appendix A) and was administered prior to each weekly instillation during induction to ascertain prior instillations effects. Patients underwent cystoscopy every 3 months following bladder tumor removal for 2 years, then every 6 months for 2 years, then annually.

Urine collection and cytokine assay

Urine was collected 4–6 h following BCG instillation weekly during induction and centrifuged to remove cells and debris. Supernatants were aliquoted and stored immediately at −80°C until assayed. Samples were diluted 1:20 with high-performance liquid chromatography grade water and measured for urinary creatinine level according to the manufacturer’s instructions using the Creatinine Colorimetric Assay Kit (Cayman Chemical) and a Synergy 2 plate reader (BioTek). Undiluted or diluted (1:1) samples were also run in duplicates using a Milliplex MAP 6-plex human cytokine panel (Millipore), and analyzed using Luminex200 and MasterPlex software (Luminex). Average cytokine concentration of each urine sample was normalized based on its creatinine level to correct for bladder urine volume.

Live BCG stock preparation for in vitro T cell response tests

One vial of lyophilized BCG vaccine was reconstituted with 1 ml of sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Approximately 50 µl of homogenous BCG suspension was then transferred into a T-25 flask with 5 ml of 7H9 broth (BD) containing 0.2% glycerol, 10% ADC (5% BSA, 2% dextrose and 0.9% NaCl; EMD) and 0.05% Tween-80 (Fisher Bioreagent) and cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 7 days. When the BCG culture became turbid but with few visible clumps, the contents were transferred into a sterile 850-cm2 roller bottle (Celltreat Scientific Product) with up to 250 ml 7H9 broth with supplements. The BCG culture was kept on a roller at 30 rpm at 37°C with 5% CO2 for approximately 7 days when the culture started to form clumps and reached an OD600 absorbance of 0.8. BCG suspension was pelleted, washed with 7H9 broth, and aliquoted into 1 ml vials and stored at −80°C. After 48 h, three vials of BCG were thawed, and each was diluted in 10-fold series to spread on a 7H10 agar plate (BD). CFU of frozen BCG stock were calculated based on the dilution that formed distinguishable individual colonies (20–100 CFU at 1–2 mm diameter) after culturing for two weeks at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Antigen-specific IFN-γ ELISPOT assay

MultiScreen ImmunoSpot plates were coated with anti-human IFN-γ capture monoclonal antibody (mAb) from Human IFN-γ ELISPOT Set (BD) overnight followed by blocking with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA, Sigma Aldrich) in sterile PBS. PBMCs were added into each well at 3–5 × 105 cells in 100 µl complete RPMI medium (cR-10) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, HyClone, GE), 2 mM L-glutamine (Corning, Fisher) and penicillin/streptomycin (Corning, Fisher). Another 100 µl of cR-10 was added to each well alone (medium control), or plus live BCG (at the multiplicity of infection, MOI = 0.1), or plus 20 μg/ml Ag85b peptide,21 or plus phytohemagglutinin (PHA) and anti-human CD3 as a positive control for T cell activation. PBMCs and antigen (BCG or Ag85b peptide) in triplicates were mixed well and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 24 h. After washes, wells were incubated with biotin-conjugated anti-human IFN-γ detection mAb at 4°C overnight. Wells were incubated with streptavidin-HRP at room temperature for 1.5 h, followed by then developing with 3-Amino-9-Ethylcarbazole (AEC) substrate. Reaction was stopped by deionized water after spots were formed. IFN-γ producing spot-forming cells (SFC) were quantified using an ImmunoSpot analyzer (S6 Micro, Cellular Technology) with ImmunoSpot software, version 6.0 (Cellular Technology). Absolute SFC in response to BCG or Ag85b peptide was normalized by SFC in medium control well for every PBMC sample.

Simultaneous detection of antigen-specific proliferation and IFN-γ production

PBMCs (1x106) were labeled with CFSE (Molecular Probes, Life Technologies) and expanded with optimal dose of live BCG (MOI 0.1) in 1 ml of cR-10 containing 10% heat-inactivated human AB serum (MP Biomedicals), or resting in medium alone for 7 days at 37°C with 5% CO2. On day 7, cell suspensions were mixed 1:500 with Cell Activation Cocktail (PMA, ionomycin and Golgi blocker cocktail, Biolegend) for 5 h. Cells were then processed for total live cell count (Vi-CellXR, Beckman Coulter) and staining with fluorochrome-conjugated anti-human CD3 mAb (clone: HIT3a, Biolegend), CD4 mAb (clone: OKT4, Biolegend), CD8 mAb (clone: RPA-T8, Biolegend) and γδ TCR mAb (clone: B1, Biolegend), followed by fixation and permeabilization with Cytofix/Cytoperm buffer (BD) prior to intracellular staining with fluorochrome-conjugated anti-human IFN-γ mAb (clone: 4S.B3, Biolegend). Data were acquired with an LSR II cytometer and analyzed using FACS Diva software (both BD). Absolute numbers of proliferated functional (defined as both CFSElo and IFN-γ+) CD4+, CD8+, and γδ T cells were calculated by multiplying total viable cells recovered after 7-day culture by percentages of proliferated functional T cell subsets. Fold changes of response by 3 and 6 months were calculated over baseline except in two cases baseline were substituted with week 1 due to blood/PBMCs availability.

Innate effector cell expansion and in vitro cytotoxicity assay

We used our established protocol.23 Briefly, PBMCs from baseline and 3-month post BCG induction were cultured in cR-10 containing 15 µM isopentenyl pyrophosphate trilithium (IPP, Sigma Aldrich) and 100 IU/ml recombinant human IL-2 (Biolegend), at 2 × 106 cells/well in 2 ml in 24-well plates. ~50% supernatant was replaced with cR-10 containing 100 IU/ml IL-2 every 2 to 3 days. Wells were split into two wells at cell number >10 × 106 cells. On day 14 of culture, cells were harvested for studies. To prepare target cells for cytotoxicity assay, human leukemia K562 cells were cultured in complete RPMI media containing 10% FBS, human bladder cancer cells RT4 and T24 were cultured in McCoy’s-5 medium containing 10% FBS and bladder cancer cell lines UM-UC3, -UC6, -UC14 were cultured in complete DMEM media containing 10% FBS until ~70% confluency. Target cells (10 x 106 cells/ml) were resuspended in PBS with 0.1% BSA and 2 µM CFSE for 15 min at 37°C, followed by two washes and resuspended in cR-10 (0.5 x106 cells/ml) at 37°C for 30 min. To prepare effector cells from γδ T cell expansion, cells were counted and diluted in twofold series in cR-10, starting at an effector to target (E: T) ratio of 50:1 with a final target cell number of 2 × 104. Some of the γδ T cells at E: T ratio of 25:1 were pre-incubated with 10 µg/ml purified anti-human NKG2D mAb (clone: 1D11, Biolegend) or γδ TCR mAb (clone: B1, Biolegend) at 37°C for 45 min where indicated. For cytotoxicity assay, 100 µl of γδ T cells was mixed with 100 µl of CFSE-labeled target cells (0.2 x106 cells/ml) in 96-well U-bottom plates and incubated at 37°C for 5 h. The pellets were washed and stained with Fixable Viability Dye (FVD)-eFluor455UV (eBioscience-Affymetrix). Percentages of target tumor cell death were analyzed on a BD LSRII flow cytometer by gating on the CFSE positive population and sub-gating on FVD positive population.

Flow cytometry for phenotyping of circulating immune cells

Thawed PBMCs and 14-day expanded innate immune cells (mainly γδ T and NK cells) were stained using fluorochrome-conjugated anti-human CD3 (clone: HIT3a, Biolegend), CD4 (clone: OKT4, Biolegend), CD8 (clone: RPA-78, Biolegend), γδ TCR (clone: B1, Biolegend), Vγ9 (clone: B3, Biolegend), Vδ2 (clone: B6, Biolegend), CD56 (clone: 5.1H11, Biolegend), NKG2D (clone: 1D11, Biolegend), 4-1BB (clone: 4B4-1, Biolegend), and CD69 (clone: FN50, Biolegend) mAbs, plus FVD for gating live cells. The total γδ T cell population were CD3+CD4–CD8– .

Tumor sample processing

Bladder tumors were collected and processed as described.44 In brief, a portion of the surgically excised bladder tumor was separated and immediately placed in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium containing 1% antibiotic (Penicillin-Streptomycin) and transported on ice. Fresh tumor tissues were washed with PBS and minced into 1–2 mm pieces and incubated in digestion solution. After 1 h, digestion was stopped by 10 ml of RPMI medium containing 10% FBS prior to live cell count, and single cell suspension was cryopreserved −150°C until analyzed.

γδ T cell sorting and RNA extraction

Thawed PBMCs from three representative prime patients, as well as tumor samples and autologous PBMCs from our bladder cancer repository, were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated anti-human CD45 (clone: 2D1, Biolegend), CD3, CD4, CD8, γδ TCR. Total γδ T cell population were sorted based on CD45+CD3+CD4–CD8– gating on BD (fluorescence-activated cell sorting) FACSAria II cell sorter. Total RNA of sorted γδ T cells was extracted using a RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). RNA concentration and quality were measured using a ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop). RNA < 20 ng/µl were further concentrated using Vacufuge Plus 5305 (Eppendorf).

Direct digital detection and analysis of γδ TCR mRNA expression by NanoString

The basic NanoString protocol has been described previously.45 Briefly, custom designed TCR gene code-set hybridized with each of the bladder cancer patient sample using 5 μl (100 ng) total RNA, 10 μl hybridization buffer, 10 μl reporter probes, and 5 μl capture probes mixed in PCR tubes and incubated at 65°C for 12–18 h in a thermal cycler with a heated lid (Pelletier, BIO-RAD DNA Engine). After hybridization, samples were processed in an nCounter PrepStation and counted using an nCounter Digital Analyzer (NanoString Technologies). The digital count data were normalized to both spiked positive control RNA and housekeeping gene (ACTB, G6PD, OAZ1, POLR1B, POLR2A, RPL27, RPS13, and TBP) and differentially expressed γδ genes were identified. Spiked positive control normalization factor was calculated from the average of sums for all samples divided by the sum of counts for an individual sample. Housekeeping gene normalization factor was calculated from the average of geometric means for all samples divided by the geometric mean for an individual sample. Normalized counts for all, either gamma chain or delta chain were then summed up and each gamma or delta chain for each sample was converted to % of total expressed TCR-gamma and TCR-delta chain.

Statistical analysis

Target enrollment was 14 patients, aiming to complete the first stage of a Simon’s two-stage design. “Response” was defined as lack of residual or recurrent disease at 3 months, certified by cytological and endoscopic examinations. “No-response” was defined as positive urine cytology or a pathologically confirmed new bladder tumor of any stage or grade. Reports on similar populations receiving standard intravesical BCG therapy show clinical response rates of 60–79% at 3 months.13,46–49 We defined a “good-drug” response rate of 75% relapse-free at 3 months as an appropriate target for this early phase trial. The null hypothesis, that the true response rate is 50% was tested against a one-sided alternative. Under these assumptions, 14 patients needed to be accrued and if there were <7 responses, then we would conclude that there is insufficient evidence to warrant further study.50,51 While 14 patients were enrolled, one patient was withdrawn from study procedures because they did not receive percutaneous BCG due to unavailability of vaccine as a result of manufacturer shortage.

Data from all patients are shown, except in cases when complete data are not available due to the inability to collect patient materials or insufficient samples (noted in results or figure legends). Area under curves (AUCs) were created by plotting urine cytokine levels over time, and AUCs were compared between groups using the Mann–Whitney test. Difference in the change in immune responses from baseline between prime and control patients was assessed with the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test. Difference in the change in urinary symptoms/BCG-related side effects from baseline between PPD converters and PPD non-converters was assessed with the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test. Cytotoxicity of sorted γδ T cells, NK cells or unsorted innate effector cell mixture was compared with two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The Kaplan–Meier method was used to graph survival across prime versus control groups. Comparison of survival distributions between groups was analyzed by the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. Bonferroni-corrected p values were calculated to account for multiple testing. For all analyses, p-values are two-sided, and p < .05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 5–6 or Stata IC/10.1.

Appendix A

AUA SYMPTOM SCORE (AUASS)

PATIENT NAME: ___________________________________________________________TODAY’S DATE: ________________________

| (Circle One Number on Each Line) | Not at All | Less Than 1 Time in 5 |

Less Than Half the Time | About Half the Time | More Than Half the Time | Almost Always |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Over the past month or so, how often have you had a sensation of not emptying your bladder completely after you finished urinating? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| During the past month or so, how often have you had to urinate again less than two hours after you finished urinating? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| During the past month or so, how often have you found you stopped and started again several times when you urinated? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| During the past month or so, how often have you found it difficult to postpone urination? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| During the past month or so, how often have you had a weak urinary stream? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| During the past month or so, how often have you had to push or strain to begin urination? |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| |

None |

1 Time |

2 Times |

3 Times |

4 Times |

5 or More Times |

| Over the past month, how many times per night did you most typically get up to urinate from the time you went to bed at night until the time you got up in the morning? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Add the score for each number above and write the total in the space to the right.TOTAL: ________________________

SYMPTOM SCORE: 1–7 (Mild) 8–19 (Moderate) 20–35 (Severe)

QUALITY OF LIFE (QOL)

| Delighted | Pleased | Mostly Satisfied | Mixed | Mostly Dissatisfied | Unhappy | Terrible | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How would you feel if you had to live with your urinary condition the way it is now, no better, no worse, for the rest of your life? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

Funding Statement

Max and Minnie Tomerlin Voelcker Fund; The Roger L. and Laura D. Zeller Charitable Foundation Chair in Urologic Cancer; Bladder Cancer Advocacy Network [2016 Young Investigator Award]; National Institutes of Health [5K23CA178204-03].

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

Robert S. Svatek is the principal investigator for the S1602 clinical trial (NCT03091660). Robert S. Svatek is a consultant for Photocure, Cold Genesys, and Ferring Pharmaceuticals.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website.

References

- 1.Lamm DL, Blumenstein BA, Crissman JD, Montie JE, Gottesman JE, Lowe BA, Sarosdy MF, Bohl RD, Grossman HB, Beck TM, et al. Maintenance bacillus Calmette-Guerin immunotherapy for recurrent TA, T1 and carcinoma in situ transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: a randomized Southwest Oncology Group Study. J Urol. 2000;163:1124–1129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lamm DL, Blumenstein BA, Crawford ED, Montie JE, Scardino P, Grossman HB, Stanisic TH, Smith JA, Sullivan J, Sarosdy MF.. A randomized trial of intravesical doxorubicin and immunotherapy with bacille Calmette-Guerin for transitional-cell carcinoma of the bladder. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(17):1205–1209. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110243251703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sylvester RJ, van der Meijden AP, Witjes JA, Kurth K.. Bacillus Calmette-Guerin versus chemotherapy for the intravesical treatment of patients with carcinoma in situ of the bladder: a meta-analysis of the published results of randomized clinical trials. J Urol. 2005;174(1):86–91; discussion −2. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000162059.64886.1c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cookson MS, Herr HW, Zhang ZF, Soloway S, Sogani PC, Fair WR. The treated natural history of high risk superficial bladder cancer: 15-year outcome. J Urol. 1997;158(1):62–67. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199707000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lamm DL. Preventing progression and improving survival with BCG maintenance. Eur Urol. 2000;37(Suppl 1):9–15. doi: 10.1159/000052376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elsasser J, Janssen MW, Becker F, Suttmann H, Schmitt K, Sester U, Stöckle M, Sester M, Goletti D. Antigen-specific CD4 T cells are induced after intravesical BCG-instillation therapy in patients with bladder cancer and show similar cytokine profiles as in active tuberculosis. PLoS One. 2013;8:9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaufmann E, Spohr C, Battenfeld S, De Paepe D, Holzhauser T, Balks E, Homolka S, Reiling N, Gilleron M, Bastian M. BCG vaccination induces robust CD4+ T cell responses to mycobacterium tuberculosis complex-specific lipopeptides in guinea pigs. J Immunol. 2016;196(6):2723–2732. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biot C, Rentsch CA, Gsponer JR, Birkhauser FD, Jusforgues-Saklani H, Lemaitre F, Biot C, Jusforgues-Saklani H, Lemaitre F, Auriau C, et al. Preexisting BCG-specific T cells improve intravesical immunotherapy for bladder cancer. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(137):137ra72. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelley DR, Haaff EO, Becich M, Lage J, Bauer WC, Dresner SM, Catalona WJ, Ratliff TL. Prognostic value of purified protein derivative skin-test and granuloma-formation in patients treated with intravesical Bacillus Calmette-Guerin. J Urology. 1986;135(2):268–271. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)45605-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lamm DL. Bacillus Calmette-Guerin immunotherapy for bladder-cancer. J Urology. 1985;134(1):40–47. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)46972-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Torrence RJ, Kavoussi LR, Catalona WJ, Ratliff TL. Prognostic factors in patients treated with intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guerin for superficial bladder-cancer. J Urology. 1988;139(5):941–944. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)42723-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niwa N, Kikuchi E, Matsumoto K, Kosaka T, Mizuno R, Oya M. Purified protein derivative skin test prior to bacillus Calmette-Guerin therapy may have therapeutic impact in patients with nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer. J Urology. 2018;199:1447–1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lamm DL, DeHaven JI, Shriver J, Sarosdy MF. Prospective randomized comparison of intravesical with percutaneous bacillus Calmette-Guerin versus intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guerin in superficial bladder cancer. J Urol. 1991;145:738–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luftenegger W, Ackermann DK, Futterlieb A, Kraft R, Minder CE, Nadelhaft P, Studer UE. Intravesical versus intravesical plus intradermal bacillus Calmette-Guerin: a prospective randomized study in patients with recurrent superficial bladder tumors. J Urol. 1996;155:483–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Witjes JA, Fransen MP, van der Meijden AP, Doesburg WH, Debruyne FM. Use of maintenance intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG), with or without intradermal BCG, in patients with recurrent superficial bladder cancer. Long-Term Follow-Up of a Randomized Phase 2 Study. Urol Int. 1993;51:67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bisiaux A, Thiounn N, Timsit M-O, Eladaoui A, Chang -H-H, Mapes J, Mogenet A, Bresson J-L, Prié D, Béchet S, et al. Molecular analyte profiling of the early events and tissue conditioning following intravesical bacillus calmette-guerin therapy in patients with superficial bladder cancer. J Urol. 2009;181(4):1571–1580. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.11.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Svatek RS, Zhao XR, Morales EE, Jha MK, Tseng TY, Hugen CM, Hurez V, Hernandez J, Curiel TJ. Sequential intravesical mitomycin plus bacillus calmette-guerin for non-muscle-invasive urothelial bladder carcinoma: translational and phase I clinical trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(2):303–311. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Combadiere B, Boissonnas A, Carcelain G, Lefranc E, Samri A, Bricaire F, Debre P, Autran B. Distinct time effects of vaccination on long-term proliferative and IFN-gamma-producing T cell memory to smallpox in humans. J Exp Med. 2004;199(11):1585–1593. doi: 10.1084/jem.20032083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garcia S, DiSanto J, Stockinger B. Following the development of a CD4 T cell response in vivo: from activation to memory formation. Immunity. 1999;11:163–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geginat J, Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A. Cytokine-driven proliferation and differentiation of human naive, central memory, and effector memory CD4(+) T cells. J Exp Med. 2001;194(12):1711–1719. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.12.1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoft DF, Blazevic A, Abate G, Hanekom WA, Kaplan G, Soler JH, Weichold F, Geiter L, Sadoff JC, Horwitz MA. A new recombinant bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccine safely induces significantly enhanced tuberculosis-specific immunity in human volunteers. J Infect Dis. 2008;198(10):1491–1501. doi: 10.1086/592450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoft DF, Brown RM, Roodman ST. Bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccination enhances human gamma delta T cell responsiveness to mycobacteria suggestive of a memory-like phenotype. J Immunol. 1998;161:1045–1054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dao V, Liu Y, Pandeswara S, Svatek RS, Gelfond JA, Liu AJ, Hurez V, Curiel TJ. Immune-stimulatory effects of rapamycin are mediated by stimulation of antitumor gamma delta T cells. Cancer Res. 2016;76(20):5970–5982. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malnati MS, Lusso P, Ciccone E, Moretta A, Moretta L, Long EO. Recognition of virus-infected cells by natural-killer-cell clones is controlled by polymorphic target-cell elements. J Exp Med. 1993;178(3):961–969. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.3.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Esin S, Batoni G, Pardini M, Favilli F, Bottai D, Maisetta G, Florio W, Vanacore R, Wigzell H, Campa M. Functional characterization of human natural killer cells responding to mycobacterium bovis bacille Calmette-Guerin. Immunology. 2004;112(1):143–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.01858.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vantourout P, Hayday A. Six-of-the-best: unique contributions of gammadelta T cells to immunology. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13(2):88–100. doi: 10.1038/nri3384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Le Bert N, Gasser S. Advances in NKG2D ligand recognition and responses by NK cells. Immunol Cell Biol. 2014;92(3):230–236. doi: 10.1038/icb.2013.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pende D, Cantoni C, Rivera P, Vitale M, Castriconi R, Marcenaro S, Nanni M, Biassoni R, Bottino C, Moretta A, et al. Role of NKG2D in tumor cell lysis mediated by human NK cells: cooperation with natural cytotoxicity receptors and capability of recognizing tumors of nonepithelial origin. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31(4):1076–1086. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maniar A, Zhang X, Lin W, Gastman BR, Pauza CD, Strome SE, Chapoval AI. Human gammadelta T lymphocytes induce robust NK cell-mediated antitumor cytotoxicity through CD137 engagement. Blood. 2010;116(10):1726–1733. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-234211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanchez-Carbayo M, Urrutia M, Romani R, Herrero M, Gonzalez de Buitrago JM, Navajo JA. Serial urinary IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, TNFalpha, UBC, CYFRA 21-1 and NMP22 during follow-up of patients with bladder cancer receiving intravesical BCG. Anticancer Res. 2001;21:3041–3047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thalmann GN, Sermier A, Rentsch C, Mohrle K, Cecchini MG, Studer UE. Urinary Interleukin-8 and 18 predict the response of superficial bladder cancer to intravesical therapy with bacillus Calmette-Guerin. J Urol. 2000;164:2129–2133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thalmann GN, Dewald B, Baggiolini M, Studer UE. Interleukin-8 expression in the urine after bacillus Calmette-Guerin therapy: a potential prognostic factor of tumor recurrence and progression. J Urol. 1997;158:1340–1344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kamat AM, Briggman J, Urbauer DL, Svatek R, Nogueras Gonzalez GM, Anderson R, Grossman HB, Prat F, Dinney CP. Cytokine panel for response to intravesical therapy (CyPRIT): nomogram of changes in urinary cytokine levels predicts patient response to Bacillus Calmette-Guerin. Eur Urol. 2016;69(2):197–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brandau S, Riemensberger J, Jacobsen M, Kemp D, Zhao W, Zhao X, Jocham D, Ratliff TL, Böhle A. NK cells are essential for effective BCG immunotherapy. Int J Cancer. 2001;92:697–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takeuchi A, Dejima T, Yamada H, Shibata K, Nakamura R, Eto M, Nakatani T, Naito S, Yoshikai Y. IL-17 production by gammadelta T cells is important for the antitumor effect of Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guerin treatment against bladder cancer. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41(1):246–251. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ratliff TL, Ritchey JK, Yuan JJ, Andriole GL, Catalona WJ. T-cell subsets required for intravesical BCG immunotherapy for bladder cancer. J Urol. 1993;150:1018–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoft DF, Xia M, Zhang GL, Blazevic A, Tennant J, Kaplan C, Matuschak G, Dube TJ, Hill H, Schlesinger LS, et al. PO and ID BCG vaccination in humans induce distinct mucosal and systemic immune responses and CD4(+) T cell transcriptomal molecular signatures. Mucosal Immunol. 2018;11(2):486–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zlotta AR, Drowart A, Van Vooren JP, de Cock M, Pirson M, Palfliet K, Jurion F, Vanonckelen A, Simon J, Schulman CC, et al. Evolution and clinical significance of the T cell proliferative and cytokine response directed against the fibronectin binding antigen 85 complex of bacillus Calmette-Guerin during intravesical treatment of superficial bladder cancer. J Urol. 1997;157:492–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miramontes R, Hill AN, Yelk Woodruff RS, Lambert LA, Navin TR, Castro KG, LoBue PA, García-García J-M. Tuberculosis infection in the United States: prevalence estimates from the national health and nutrition examination survey, 2011–2012. PLoS One. 2015;10(11):e0140881. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ota MOC, Brookes RH, Hill PC, Owiafe PK, Ibanga HB, Donkor S, Awine T, McShane H, Adegbola RA. The effect of tuberculin skin test and BCG vaccination on the expansion of PPD-specific IFN-gamma producing cells ex vivo. Vaccine. 2007;25(52):8861–8867. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vilaplana C, Ruiz-Manzano J, Gil O, Cuchillo F, Montane E, Singh M, Spallek R, Ausina V, Cardona PJ. The tuberculin skin test increases the responses measured by T cell interferon-gamma release assays. Scand J Immunol. 2008;67(6):610–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2008.02103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pouchot J, Grasland A, Collet C, Coste J, Esdaile JM, Vinceneux P. Reliability of tuberculin skin test measurement. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:210–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoft DF, Brown RM, Belshe RB. Mucosal bacille calmette-Guerin vaccination of humans inhibits delayed-type hypersensitivity to purified protein derivative but induces mycobacteria-specific interferon-gamma responses. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30(Suppl 3):S217–S222. doi: 10.1086/313864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mukherjee N, Ji N, Hurez V, Curiel TJ, Montgomery MO, Braun AJ, Nicolas M, Aguilera M, Kaushik D, Liu Q, et al. Intratumoral CD56(bright) natural killer cells are associated with improved survival in bladder cancer. Oncotarget. 2018;9(92):36492–36502. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.26362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deniger DC, Maiti SN, Mi TJ, Switzer KC, Ramachandran V, Hurton LV, Ang S, Olivares S, Rabinovich BA, Huls MH, et al. Activating and propagating polyclonal gamma delta T cells with broad specificity for malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(22):5708–5719. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duchek M, Johansson R, Jahnson S, Mestad O, Hellstrom P, Hellsten S, Malmstrom PU, Members of the Urothelial Cancer Group of the Nordic Association of U. Bacillus Calmette-Guerin is superior to a combination of epirubicin and interferon-alpha2b in the intravesical treatment of patients with stage T1 urinary bladder cancer. A Prospective, Randomized, Nordic Study. Eur Urol. 2010;57(1):25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oddens J, Brausi M, Sylvester R, Bono A, van de Beek C, van Andel G, Gontero P, Hoeltl W, Turkeri L, Marreaud S, et al. Final results of an EORTC-GU cancers group randomized study of maintenance bacillus Calmette-Guerin in intermediate- and high-risk Ta, T1 papillary carcinoma of the urinary bladder: one-third dose versus full dose and 1 year versus 3 years of maintenance. Eur Urol. 2013;63(3):462–472. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaasinen E, Wijkstrom H, Malmstrom PU, Hellsten S, Duchek M, Mestad O, Rintala E. Alternating mitomycin C and BCG instillations versus BCG alone in treatment of carcinoma in situ of the urinary bladder: a nordic study. Eur Urol. 2003;43:637–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gandhi NM, Morales A, Lamm DL. Bacillus Calmette-Guerin immunotherapy for genitourinary cancer. BJU Int. 2013;112(3):288–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Simon R, Altman DG. Statistical aspects of prognostic factor studies in oncology. Br J Cancer. 1994;69:979–985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Simon R. Optimal two-stage designs for phase II clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1989;10:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.