ABSTRACT

Introduction: Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) with sarcomatoid component carries a poor prognosis. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (CPIs) have been approved for the treatment of metastatic RCC, but their efficacy in patients with sarcomatoid component is not known.

Materials and Methods: We conducted a retrospective chart review of 30 consecutive patients at our center who were treated for metastatic RCC with sarcomatoid component.

Results: Ten patients were treated with CPI group while 20 patients were in No-CPI group. There were no significant differences in age, sex, race, and stage at diagnosis between the two groups. After a median follow-up of 35 months, 3 of 10 patients in CPI arm and 5 of 20 patients in No-CPI group were alive. The median overall survival was 33.8 m in immunotherapy group compared to 8.8 m in nonimmunotherapy group (p = .001).

Discussion: In our experience, CPI therapy resulted in better outcomes compared to traditional therapy with molecular-targeted agents or chemotherapy in these patients.

KEYWORDS: Immunotherapy, renal cell carcinoma, sarcomatoid, kidney cancer, nivolumab

Background

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the most common type of primary renal neoplasm, accounting for 80–85% of all kidney cancers.1 In the United States, approximately 65,000 new cases of RCC are diagnosed annually resulting in 15,000 deaths each year.2 Prior to the approval of immune checkpoint inhibitors (CPIs), the first-line treatment of advanced RCC consisted of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) or molecular inhibitors of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR).3-7 The response rates to these agents range from 25% to 30% translating into progression-free survival of 8–10 months and overall survival (OS) around 24 months.8-10 The presence of sarcomatoid differentiation in RCC is historically associated with poor response to treatment with TKIs and chemotherapeutic agents. In a retrospective analysis of 43 patients with metastatic sarcomatoid RCC-treated with VEGF-directed therapy, the overall response rate (ORR) was only 19% and responses were limited to patients with less than 20% sarcomatoid component.11 In another study of 230 patients with metastatic sarcomatoid RCC, the response rate was only 21% with OS of 10.4 months with VEGF inhibitors.12 Higher response rate was observed with the combination of chemotherapy with molecularly targeted therapy. A phase II trial comparing the combination of sunitinib and gemcitabine to sunitinib alone showed ORR of 30% with median OS of 11 months.13 However, the outcomes remain poor overall and most patients diagnosed with metastatic sarcomatoid RCC die within a year of diagnosis.13,14

The advent of immune CPIs has led to improved outcomes in patients with metastatic RCC in recent years. Nivolumab, a fully human monoclonal IgG4 antibody directed against programmed cell death-1 (PD-1), and ipilimumab, a recombinant human IgG1 antibody that binds to the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4), have both shown therapeutic efficacy in the treatment of RCC. In a phase III trial evaluating second-line treatment options for metastatic RCC, nivolumab significantly improved OS (25 vs. 19.6 months) compared with everolimus.15 In the first-line setting, the combination of ipilimumab and nivolumab produced durable responses in intermediate and poor-risk RCC in the phase III Checkmate 214 trial with significant improvement in response rate (42% vs. 27%) and OS (not reached vs. 39 months) compared to monotherapy with sunitinib.16 These results have led to incorporation of immune CPIs in the treatment algorithms for metastatic RCC along with molecular targeted agents against VEGF and mTOR.17 However, there is paucity of data regarding the efficacy of immune CPI agents in RCC with sarcomatoid features. A recent study showed that RCC with sarcomatoid differentiation express PD-L1 at higher levels compared to RCC without sarcomatoid differentiation.18 This finding indicates that patients with sarcomatoid RCC may be good candidates for treatment with PD-1/PD-L1 blockers.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective chart review of all patients who were diagnosed with metastatic RCC containing sarcomatoid component at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center between January 2010 to June 2017. Patients who never received any antineoplastic therapy were excluded from analysis. Patients were divided into two cohorts (CPI vs. no CPI) depending on whether or not they received immune CPIs as any line of therapy. Patient characteristics, tumor histology, type of therapy used, time to immunotherapy, and outcomes including response and OS were recorded and analyzed.

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics were reported by cohort using the mean and median for continuous variables; and using frequencies and relative frequencies for categorical variables. Comparisons were made using the Mann–Whitney U and Fisher’s exact tests for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. OS was defined as the time from diagnosis of metastatic disease until death due to any cause or last follow-up. OS was summarized by cohort using standard Kaplan–Meier methods, where estimates of median OS and half-year OS rates were obtained with 95% confidence intervals. Comparisons were made using the log-rank test. To account for potential effects of age or stage on OS, a stratified log-rank test (stratified by dichotomized age or stage) was also utilized. All analyses were completed in SAS v9.4 (Cary, NC) at a significance level of 0.05.

Results

A total of 35 patients were diagnosed with metastatic sarcomatoid RCC at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center between January 2010 and June 2017. Five patients did not receive any systemic therapy and were excluded from analysis. Ten patients were treated with immune CPIs while 20 patients were treated without the use of immunotherapy. All patients had metastatic disease at the time of treatment. All patients had total or partial nephrectomy as part of their treatment. Baseline patient characteristics of the two groups are summarized in Table 1. No significant differences were observed between the two cohorts. All patients but two (one in each cohort) had intermediate or poor risk disease by International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium criteria.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients in two cohorts.

| CPI N (%) |

No-CPI N (%) |

Overall | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 10 (33.3) | 20 (66.7) | 30 (100) | ||

| Age, years | Mean | 63 | 56 | 58.4 | 0.22 |

| Median | 61.5 | 58 | 59 | ||

| Age, years | ≤60 | 5 (50) | 11 (55) | 16 (53.3) | 1.00 |

| >60 | 5 (50) | 9 (45) | 14 (46.7) | ||

| Sex | Male | 7 (70) | 10 (50) | 17 (56.7) | 0.44 |

| Female | 3 (30) | 10 (50) | 13 (43.3) | ||

| Race | Caucasian | 9 (90) | 19 (95) | 28 (93.3) | 1.00 |

| African American | 1 (10) | 1 (5) | 2 (6.7) | ||

| Stage at diagnosis | 2 | 2 (20) | 2 (6.7) | 0.10 | |

| 3 | 4 (40) | 6 (30) | 10 (33.3) | ||

| 4 | 4 (40) | 14 (70) | 18 (60) | ||

| IMDC Risk Score | Low (0) | 1 (10) | 1 (5) | 2 | 0.31 |

| Intermediate (1-2) | 2 (20) | 9 (45) | 11 | ||

| Poor (≥3) | 7 (70) | 10 (50) | 17 | ||

CPI: Check point Inhibitors, IMDC: International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database.

In the immunotherapy arm, nine patients received nivolumab and one patient was treated with combination of ipilimumab and nivolumab. Patients receiving immunotherapy were not treated with any other treatment modality while on immune CPIs. The median time from diagnosis of metastatic disease to the start of treatment with immunotherapy was 19.0 months. Patients received a median of two therapies (Range: 1–5) prior to treatment with immune CPIs. Eight of ten patients received VEGF-directed therapy, two received inhibitors of mTOR pathway, while three were treated with cytotoxic chemotherapy. One patient received palliative radiation to paraspinal metastasis. The median duration of CPI-therapy was 17 weeks (Range: 4–weeks).

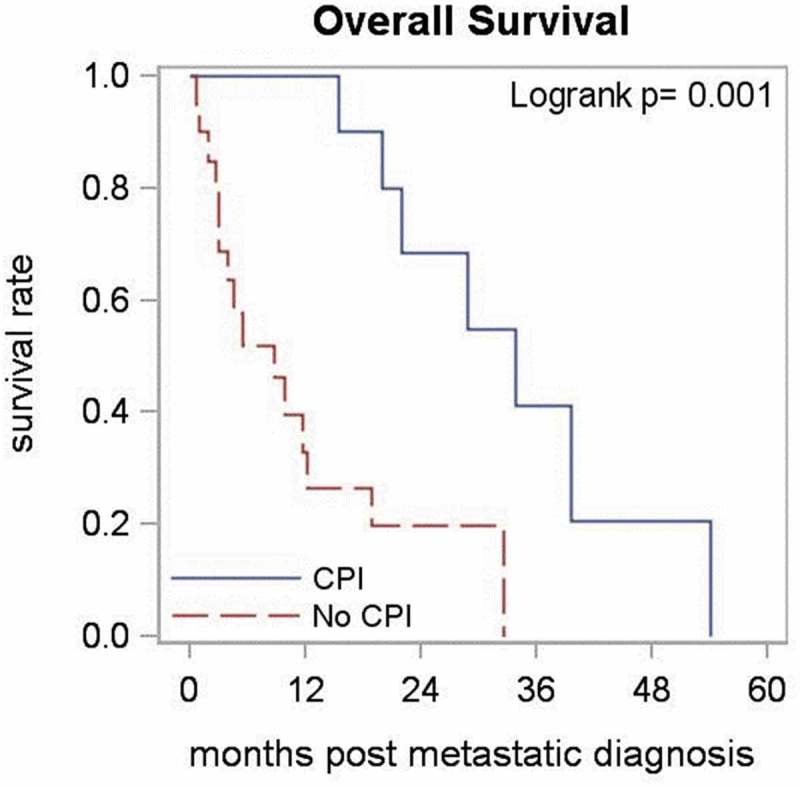

After a median follow-up of 35 months, 3 of 10 patients in CPI arm and 5 of 20 patients in no CPI group were alive. There was a statistically significant difference in OS (p = .001) between the patients treated with CPIs and untreated cohorts, where the treated patients tended to have improved outcomes (Figure 1). The median OS was 33.8 months in immunotherapy group compared to 8.8 months in nonimmunotherapy group. These results were also observed in the stratified analysis (by age, p = .002; and by stage at diagnosis, p = .011). As per RECIST v1.1, one patient had a partial response, four patients had stable disease while five patients had progressive disease as the best response to treatment with CPIs. Overall, the CPIs were well tolerated, the only grade ≥3 adverse effect being a grade 3 colitis that necessitated a short course of steroids, but the patient had already been taken off the drug due to disease progression.

Figure 1.

Overall survival between patients who received therapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors (CPI) and those who did not (No CPI).

Discussion

Our analysis of ten patients with metastatic sarcomatoid RCC show immunotherapy with CPIs is a valid option for these patients and results in better outcomes compared to traditional therapy with molecular-targeted agents or chemotherapy. These results are consistent with those reported by Raychaudhuri et al. in their case series of two patients with sarcomatoid RCC, who had prolonged responses to nivolumab following failure of TKI therapy.19 The excellent response to immunotherapy observed in our study can be attributed to the immunosuppressive biology of sarcomatoid RCC. The cellular expression of PD-L1 in sarcomatoid RCC was characterized by Joseph et al. in 40 patients and found PD-L1 positivity in 89% of samples.18 In addition, the sarcomatoid component in RCC is known to have a greater mutation burden in terms of higher number of somatic single-nucleotide variants and increased frequency of loss of heterozygosity, compared to carcinomatous component.20 These findings suggest the immunosuppressive nature of sarcomatoid RCC and its potential susceptibility to CPIs.

Our study has several limitations including a retrospective analysis and a large interval between diagnosis and start of CPI therapy. However, the magnitude of difference in OS between the two groups suggests that the difference in outcomes would have persisted even when this “immortal time bias” has been accounted for. Our patients were heavily pretreated with six patients having received ≥2 therapies prior to the start of CPIs.

In summary, our results show that immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibition is a valid therapeutic option for patients with metastatic sarcomatoid RCC. Although the current treatment guidelines from National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) does not differentiate RCC based on the presence of sarcomatoid component, immune CPIs should be considered early in the treatment paradigm. These results suggest further prospective studies of immune CPIs alone or in combination with other agents/RT for metastatic RCC with sarcomatoid differentiation.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Roswell Park Cancer Institute and National Cancer Institute (NCI) grant P30CA016056.

Disclosure of interest

Dr George reported personal fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Corvus, Exelixis, Genentech, Janssen, Novartis, Sanofi/Genzyme, Genentech and Pfizer, and institutional research funds from Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Corvus, Celldex, Merck, Novartis, and Pfizer. Other authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Specific contributions to the study

AH, MP, KA, and SG created and designed the study. AH, MP and SK collected the data. All authors contributed to writing and revising the manuscript.

References

- 1.Chow W-H, Dong LM, Devesa SS.. Epidemiology and risk factors for kidney cancer. Nat Rev Urol. 2010. May;7(5):245–257. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2010.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A.. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018. January;68(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Oudard S, Hutson TE, Porta C, Bracarda S, Grünwald V, Thompson JA, Figlin RA, Hollaender N, et al. Efficacy of everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase III trial. Lancet Lond Engl. 2008. August 9;372(9637):449–456. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, Michaelson MD, Bukowski RM, Oudard S, Negrier S, Szczylik C, Pili R, Bjarnason GA, et al. Overall survival and updated results for sunitinib compared with interferon alfa in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2009. August 1;27(22):3584–3590. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sternberg CN, Davis ID, Mardiak J, Szczylik C, Lee E, Wagstaff J, Barrios CH, Salman P, Gladkov OA, Kavina A, et al. Pazopanib in locally advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results of a randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2010. February 20;28(6):1061–1068. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.9764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hudes G, Carducci M, Tomczak P, Dutcher J, Figlin R, Kapoor A, Staroslawska E, Sosman J, McDermott D, Bodrogi I, et al. Temsirolimus, interferon alfa, or both for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007. May 31;356(22):2271–2281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc063190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Escudier B, Eisen T, Stadler WM, Szczylik C, Oudard S, Staehler M, Negrier S, Chevreau C, Desai AA, Rolland F, et al. Sorafenib for treatment of renal cell carcinoma: final efficacy and safety results of the phase III treatment approaches in renal cancer global evaluation trial. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2009. July 10;27(20):3312–3318. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.5511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Cella D, Reeves J, Hawkins R, Guo J, Nathan P, Staehler M, de Souza P, Merchan JR, et al. Pazopanib versus sunitinib in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2013. August 22;369(8):722–731. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1303989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, McCann L, Deen K, Choueiri TK. Overall survival in renal-cell carcinoma with pazopanib versus sunitinib. N Engl J Med. 2014. May 1;370(18):1769–1770. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1400731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Motzer RJ, Barrios CH, Kim TM, Falcon S, Cosgriff T, Harker WG, Srimuninnimit V, Pittman K, Sabbatini R, Rha SY, et al. Phase II randomized trial comparing sequential first-line everolimus and second-line sunitinib versus first-line sunitinib and second-line everolimus in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2014. September 1;32(25):2765–2772. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.6911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Golshayan AR, George S, Heng DY, Elson P, Wood LS, Mekhail TM, Garcia JA, Aydin H, Zhou M, Bukowski RM, et al. Metastatic sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted therapy. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2009. January 10;27(2):235–241. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.0000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chittoria N, Zhu H, Choueiri TK, Kroeger N, Lee J-L, Srinivas S, Page R, Lind MJ, Peake MD, Møller H. Outcome of metastatic sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma (sRCC): results from the International mRCC Database Consortium. J Clin Oncol. 2013. May 20;31(15_suppl):4565. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.0219. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Michaelson MD, McDermott DF, Atkins MB, Cho DC, Olivier KM, Schwarzberg AB, Page R, Lind MJ, Peake MD, Møller H. Combination of antiangiogenic therapy and cytotoxic chemotherapy for sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013. May 20;31(15_suppl):4512. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.0219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Escudier B, Droz JP, Rolland F, Terrier-Lacombe MJ, Gravis G, Beuzeboc P, Chauvet B, Chevreau C, Eymard JC, Lesimple T, et al. Doxorubicin and ifosfamide in patients with metastatic sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma: a phase II study of the Genitourinary Group of the French Federation of Cancer Centers. J Urol. 2002. September;168(3):959–961. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64551-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, McDermott DF, George S, Hammers HJ, Srinivas S, Tykodi SS, Sosman JA, Procopio G, Plimack ER, et al. Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2015. November 5;373(19):1803–1813. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Escudier B, Tannir NM, McDermott DF, Frontera OA, Melichar B, Plimack ER, Barthelemy P, George S, Neiman V, Porta C, et al. LBA5CheckMate 214: efficacy and safety of nivolumab + ipilimumab (N+I) v sunitinib (S) for treatment-naïve advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC), including IMDC risk and PD-L1 expression subgroups. Ann Oncol [Internet] 2017. September 1 [cited 2018 April4];28(suppl_5). Available from ;(). []. https://academic.oup.com/annonc/article/28/suppl_5/mdx440.029/4109941. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Powles T, Albiges L, Staehler M, Bensalah K, Dabestani S, Giles RH, Hofmann F, Hora M, Kuczyk MA, Lam TB, et al. Updated European Association of Urology Guidelines recommendations for the treatment of first-line metastatic clear cell renal cancer. Eur Urol. 2017. December 7;73(3):311–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joseph RW, Millis SZ, Carballido EM, Bryant D, Gatalica Z, Reddy S, Bryce AH, Vogelzang NJ, Stanton ML, Castle EP, et al. PD-1 and PD-L1 expression in renal cell carcinoma with sarcomatoid differentiation. Cancer Immunol Res. 2015. December 1;3(12):1303–1307. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raychaudhuri R, Riese MJ, Bylow K, Burfeind J, Mackinnon AC, Tolat PP, Iczkowski KA, Kilari D. Immune check point inhibition in sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma: a new treatment paradigm. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2017. October 1;15(5):e897–901. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2017.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bi M, Zhao S, Said JW, Merino MJ, Adeniran AJ, Xie Z, Nawaf CB, Choi J, Belldegrun AS, Pantuck AJ, et al. Genomic characterization of sarcomatoid transformation in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2016. February 23;113(8):2170–2175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1525735113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]