Abstract

Housing prices being one factor thought to contribute to segregation patterns, this article aims at differentiating gated communities from non-gated communities in terms of change in property values. To what extent do gated communities contribute to price filtering of residents, and do patterns of price differentiation favor gated communities in the long run? The article provides an analysis of the territorial nature of gated communities and how the private urban-governance realm theoretically sustains the hypothesis that property values within gated communities are better protected. In order to identify price patterns across time, we elaborate a spatial analysis of values (price distance index) by identifying gated communities with real estate listings in 2008 and matching these with historical data at the normalized census-tract level from the 1980, 1990 and 2000 census in the greater Los Angeles region. We conclude that gated communities are very diverse in kind. The wealthier the area, the more it contributes to fuelling price growth, especially in the most highly desired locations in the region. Furthermore, a dual behavior emerges in areas with an over-representation of gated communities. On the one hand, gated communities are located within local contexts that introduce greater heterogeneity and instability in price patterns. In this way, they contribute to a local increase in price inequality that destabilizes price patterns at neighborhood level. On the other hand, gated communities proliferate in contexts that show a very strong stability in terms of price homogeneity at the local level.

Résumé

La sélection des résidents d’un quartier par le prix constituant un facteur fondamental de la ségrégation, cet article vise à analyser la manière dont les gated communities se différentient des autres lotissements non enclos, en termes d’évolution des valeurs immobilières. Les gated communities constituant avant tout des lotissements comme les autres, à la différence près que leur accès est fermé et contrôlé, notre étude porte sur la manière dont ces lotissements fermés se différencient des autres lotissements en termes d’appréciation ou de dépréciation relative des biens immobiliers; et ce faisant dans quelle mesure elles contribuent à une sélection sociale des résidents accentuée par des logiques différentielles de production des prix immobiliers sur le temps long. Dans une perspective expérimentale à l’échelon local dans la région de Los Angeles, cet article vise donc, d’une part, à explorer la nature territoriale des gated communities, en particulier la manière dont leur appartenance au genre plus général des lotissements en copropriété (Common Interest Development) permet de structurer la réflexion sur la plus-value immobilière générée par rapport aux lotissements non-enclos. L’analyse porte d’autre part — avec les outils de l’analyse spatiale — sur les discontinuités des prix immobiliers dans les zones ou les lotissements planifiés (fermés ou non) sont surreprésentés (entre 1980 et 2008). A partir de données immobilières, nous identifions les gated communities et les comparons aux données fournies au niveau des Census Tract du recensement en 1980, 1990 et 2000, afin d’analyser les types de trajectoires temporelles des prix immobiliers. Les résultats montrent que les gated communities sont d’une part très hétérogènes, et contribuent globalement à soutenir la hausse des marchés immobiliers, en particulier dans les zones les plus attractives. De plus, les gated communities introduisent localement une plus grande hétérogénéité et instabilité dans les types de trajectoires temporelles des prix immobiliers à l’échelon du quartier.

Introduction

For almost two decades, scholars have been scrutinizing gated communities (GCs), including those who address the question of whether or not they produce a housing price premium and thus contribute to residential segregation. Earlier studies on housing prices in GCs have focused either on the price premium produced by gating a neighborhood by means of hedonic modeling in the United States (Bible and Hsieh, 2001; Lacour-Little and Malpezzi, 2001) or other empirical methods in South Africa (Altini and Akindele, 2005). All studies yield comparable results concerning the price premium in favor of gated communities compared to non-gated subdivisions in the same area. Our line of inquiry seeks to analyze how this price premium structures price differentiation patterns between gated and non-gated areas in the long run.

This article studies the sprawling suburban areas of southern California (Santa Barbara, Ventura, Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino and Riverside counties) by means of a quantitative approach to price change between communities in the same vicinity. The article therefore focuses on gated communities in southern California, and differentiates gated communities from non-gated communities in terms of property values. We further study the patterns of change in property values between 1980 and 2008.

Two overlapping understandings of gated communities have emerged in academic literature. One group of scholars considers them to be a family member of a more general class that includes master-planned communities (horizontal version) and condominiums (vertical version) governed by collective tenure and incorporated organizational arrangements (McKenzie, 1994; Kennedy, 1995; Webster, 2001; McKenzie, 2003; Gordon, 2004; Webster and Le Goix, 2005; Kirby et al., 2006; McKenzie, 2006a; Le Goix and Webster, 2008). Important considerations from this perspective include the nature of ownership, governance and management. Such neighborhoods will, for example, have some kind of property owners association employed by a governing body formed from residents who are tied together by a common set of interests by contract.

A second group of scholars contends that it is the existence of fences, walls and security features that distinguishes gated communities as a residential form that is significantly different from non-gated places (Blakely and Snyder, 1997; Low, 2003; Le Goix, 2005, Vesselinov et al., 2007; Vesselinov and Le Goix, 2009). This discourse tends to emphasize the impact of gated communities on crime, segregation, property values, citizenship and related behavior.

This article adjudicates between these two understandings and elaborates on whether gating a neighborhood enhances the effect of private governance efforts in that both lead to shielding property values. Gated developments in the United States are residential communities, among others, and they are private Common Interest Developments run according to private contractual regulations, the major difference being that they are gated. Two overlapping lines of inquiry need to be addressed here: (1) Are gated communities different from non-gated suburban neighborhoods with regard to price increase or depreciative trends? (2) To what extent does the enclosure of a neighborhood significantly contribute to price change-patterns in favor of gated communities?

We argue that housing prices describe not only intrinsic characteristics of housing but also the characteristics of places, assessed and perceived at different geographical levels (location in a city, social characteristics of the neighborhood, and those of the street). Price changes also induce a powerful social filter in metropolitan suburban areas. From an experimental perspective at the lower local scale, we analyze property values in areas where planned communities were prevalent between 1980 and 2008. We identify gated and non-gated communities using as primary source real estate agents’ listings of properties on sale in 2008. We identify price patterns across time by matching these with data at the tract level from the 1980, 1990 and 2000 census.

The next section of the article reviews the relationships between gated communities and private residential governance in proprietary neighborhoods, in order to better understand how gating a neighborhood might generate a higher price premium than the overall legal and contractual structuring of a private neighborhood designed to avoid negative externalities. We then review the issues of gated communities and prices in a context of price growth since the 1980s, which was interrupted by two major crises (in the mid-1990s and the 2008 foreclosure crisis). We also put into perspective a case study based upon empirical data from southern California. In the subsequent section, we analyze the main trends of price changes, so that we might identify underlying local depreciation and valuation dynamics as they apply to gated communities. Finally, we propose a spatial analysis that discriminates patterns of price changes between neighborhoods in 1980 and 2008, with a special focus on how price change introduces similarity or dissimilarity between communities and how these changes correlate with the gated or non-gated status of neighborhoods.

Protecting property values in gated and non-gated private communities: theoretical perspectives

In this section, we analyze how the definition of gated communities (GCs) requires addressing on the one hand the structuring of private urban governance, dedicated to the protection of property values (McKenzie, 1994), and on the other hand how gating a planned subdivision also has an impact on property values and theoretically sustains the hypothesis of a price premium in GCs, compared to non-gated private residential communities.

Gated communities: providing security and community services

Blakely and Snyder’s (1997) book focused academic debate and helped shape the discourse on this topic. The authors took a predominantly morphological view, in which gated communities were simply walled and gated residential neighborhoods. After almost two decades of academic debate on GCs, one major difficulty in addressing this phenomenon is how to compare different types of gated communities, which can be described using the same terminology as for privatized neighborhoods, but do not cover the same societal impact (Claessens, 2009). Commentators have recorded the phenomenon across national contexts, under a diversity of denominations (Glasze et al., 2002; Atkinson and Blandy, 2005), all with contextual references and an emphasis on historical patterns of enclosure (Low, 2006; Bagaeen and Uduku, 2010). There is nevertheless a noticeable consensus among authors who describe the security logic as a non-negotiable requirement in contemporary urbanism and architecture, and all agree that ‘both the privatization of public space and the fortification of the urban realm, in response to the fear of crime, has contributed significantly to the rise of the contemporary gated community phenomena’ (Bagaeen and Uduku, 2010: 3) in Western Europe (Blandy, 2006; Raposo, 2006; Le Goix and Callen, 2010), in post-communist Europe (Blinnikov et al., 2006; Stoyanov and Frantz, 2006; Cséfalvay, 2009a), in the Arabian peninsula (Glasze, 2006), in Israel (Rosen and Razin, 2009), in China (Wu, 2005; Low, 2006; Webster et al., 2006) and elsewhere. On the one hand, a strong thesis is the link between security and fear of others — sometimes distinguished from the desire for security of person and property (Low, 2001; 2003). In Argentina and in Brazil (Caldeira, 2000), in the United States (Blakely and Snyder, 1997; Low, 2003), in Europe (Billard et al., 2005) and in Mexico (Low, 2001), gating has been associated with a lack of confidence in public security enforcement. On the other hand, residential preferences and economic rationale prevail, and gated communities are understood as an exit option from the public realm, from the over-regulated and overcrowded cities, with their inefficiency in providing community services (Cséfalvay, 2009b).

Regardless of local traditions and national legal contexts, there are various organizational types of private residential neighborhoods, which are differentiated by the way property rights are assigned for shared spaces, facilities and exclusively used housing units: condominiums, stock cooperatives, corporations and homeowners associations (McKenzie, 1994; Glasze, 2005). In homeowners associations, all common spaces and facilities are the property of an incorporated body set up specifically for that purpose. A covenant making the owner a shareholder in the corporation is attached to the deed of a residential lot, with voting rights according to the size of the share (Glasze, 2005). McKenzie has termed these neighborhoods Common Interest Developments (CIDs), and we shall use this term too.

By the year 2000 more than 15% of the United States housing stock was in Common Interest Developments — and the number of units in these privately governed residential schemes rose from 701,000 in 1970 to 16.3 million in 1998 (McKenzie, 2003; 2005; 2006b). The Community Association of America estimated in 2002 that 47 million Americans were living in 231,000 community associations and that 50% of all new homes in major cities belonged to community associations (Sanchez and Lang, 2005). Only a proportion — between 12% and 30% in the region of Los Angeles (Le Goix, 2003) — of these private local government areas are gated.

Gated communities and CIDs in the US: Social homogeneity and the preservation of property values

Across history, red-lining, neighborhood associations and land-use regulations have been instrumental in protecting property values (Massey and Denton, 1993). Research on the homeowners movements in Los Angeles (Purcell, 1997) and another recent study by Cervero and Duncan (2004: 299) in Santa Clara (California) suggest that, ‘to the degree that local zoning responds to land-market forces, exclusion in residential settings is more a product of racial than land-use composition’. In the United States there is thus a long history of exclusive regulations being implemented both in planning and land-use documents (Ihlanfeldt, 2004; Kato, 2006), but more significantly in the legal structuring of residential associations by means of restrictive covenants (Kennedy, 1995; Fox-Gotham, 2000; Kirby et al., 2006). As a consequence, the implementation of Conditions, Covenants and Restrictions (CCRs) and the overall private urban governance effort in private neighborhoods are not tangential in protecting or shielding property values. For instance, based on a New York gated communities and condominiums case study, Low (2009) believes that private governance structures (condominium and residential associations) designed to exclude others and organize social homogeneity are as important as securitization strategies in shaping the social project in gated communities and exclusive housing schemes.

Both CIDs and GCs belong to the same kin by law, but differ in morphology in terms of gates and security features. Gated communities are territories of exclusiveness; they build up social homogeneity based on security, snob value, fear of crime, and symbolic and physical distance from others (through gates and walls). But all these attributes are not truly independent, as they result from a contractual agreement binding all property owners (Brower, 1992; Kennedy, 1995). Generally speaking, CID and condominium ownership encourage speculation around real estate prices. However, gating a CID reinforces a proactive private governance effort towards preservation of property values. The liberal hypothesis assumes that operating costs of private governance are paid for by the increase in property values.

First, the quasi-governmental regime plays a crucial role in shielding property values: GCs and non-gated developments, as local quasi-governments in terms of provision of public services (McKenzie, 1994; 2006c), act as local consumption clubs of urban services (Webster, 2002). The short-term apparent cost-benefits market efficiency in providing collective services (Foldvary, 1994) must be matched to the risks of long-term spillover effects, inefficiency of the decision-making process, residents’ lack of involvement (discussed, for example, by McKenzie, 1994; Blakely and Snyder, 1997; Low, 2003), and the risk that obsolescence and inflated maintenance costs may undermine the tidiness and reputation of a neighborhood and ultimately its property values (Miller, 1989; Berding, 1999). Second, according to Brower (1992) and Kennedy (1995), many court cases and legal restrictions apply only to gated communities and make a special case of their governmental regime that cannot be extended to non-gated private communities. Finally, as public dedication cannot obviously be applied to gated streets, GCs need to live up to their promise and must be founded on a financial model that takes account of rising costs owing to obsolescence of infrastructure and amenities managed behind gates by the property owners associations. The gating of a CID ultimately stresses the private realm and thus reinforces the selection of residents. This effort towards social control and homogeneity contributes to the overall effect of shielding property values and creating a price premium.

Gated communities, a tool to protect prices and to avoid urban decay

Neither private urban governance nor gated morphology can independently explain the social structure of the community (Low, 2009) or the price premium in gated communities (Lacour-Little and Malpezzi, 2001). An early theorization of gated streets as defensible spaces has been developed by Newman et al. (1974) as a pre-emptive effort against urban decay and depreciation of a neighborhood. Newman makes an apology for gating as a device that prevents urban decay by giving social control over the environment to residents. This includes installing street barriers in retro-fitted residential neighborhoods as a way of reintroducing public safety and controlling gang activities. Furthermore, gates, CCTV, private police and amenities have to be paid for, thus residents of gated communities bet on property-value gains to offset the cost of gating and private urban governance. Consent to pay seems paramount in determining which residents are attracted to a scheme that promotes security, exclusiveness and a gated lifestyle (Newman, 1996). Recent research also shows that GCs enjoy premium house prices compared to private neighborhoods in surrounding areas. Hedonic modeling demonstrated the measurable effect of the location of the property within a gated community (Bible and Hsieh, 2001). In Saint Louis, Missouri, it has been demonstrated that the premium can be attributed in part to the privacy-security effects of gating, and in part to private subdivision and the homeowners association’s proactive regulations and governance efforts to protect the neighborhood from negative externalities. By means of hedonic analysis, the author demonstrates a 26% price premium in cases where gates had been erected between 1979 and 1998. By comparison, a regular, non-gated private neighborhood produced only an estimated 9% price premium over a regular neighborhood (Lacour-Little and Malpezzi, 2001). All these results support evidence that gated streets and residential associations together are instrumental in avoiding decay and other externalities in a neighborhood. This is confirmed in some places, for instance in South Africa, where gated community property values are usually higher than in regular neighborhoods; this perception is shared both by prospective buyers and real estate agents (Altini and Akindele, 2005).

But there is also some evidence that the price premium in GCs is sometimes detrimental to property prices in non-gated developments nearby. In the Los Angeles area, between 1980 and 1990, GC prices were more resistant to real estate market fluctuations than prices for regular residential neighborhoods and non-gated CIDs, especially between 1990 and 1995 (Le Goix, 2007). The study shows that failure of property owners associations occurs when costs rise above a sustainable level in conjunction with a rapid decrease in property values. A majority of average middle-class gated enclaves located within more diverse neighborhoods did not succeed in creating a significant price premium and/or did not maintain significant price growth during the last decade (Le Goix, 2007).1

A case study in southern California: context matters

Southern California makes a good case study for three main reasons: (1) the level of diffusion of GCs in the area; (2) the legacy of gated and private communities in the area, starting in the early 1930s (Le Goix and Callen, 2010); and (3) the specific fiscal context that has favored the diffusion of private residential neighborhoods.

The impact of taxation in California

The diffusion of homogeneous residential suburban communities in this region is related to suburban growth, to the anti-fiscal posture and to municipal fragmentation dynamics that have affected the Los Angeles area since the 1950s. This level of analysis yields intricate interactions between private governance and public authorities, which also has an impact on property values, mostly because of taxation issues in the United States, and particularly in California. These processes have progressively diminished the fiscal resources available to local governments, while urban sprawl has produced an increased need for revenue to finance public infrastructure (roads, freeways) in low-density suburban settlement patterns. In Los Angeles, the anti-fiscal posture has been associated with the incorporation of numerous cities — the first of which was Lakewood in 1954.2 These new municipal governments were designed to avoid paying costly county property taxes — which after incorporation were replaced by lower city assessments and better local control over local development and other municipal affairs (Miller, 1981). A second step was the 1978 ‘taxpayers’ revolt’ — a homeowner-driven property tax roll-back known as Proposition 13 (Purcell, 1997). Passed in 1978, this tax limitation increased the need for public governments to attract new residential subdivisions, especially those that would bring wealthy taxpayers into their jurisdiction. A third influence on the spatial diffusion of gated enclaves was the rapid growth of the Los Angeles area, which was sustained by massive population inflow during the 1980s. Common Interest Developments (CIDs) are fiscal ‘cash cows’ for local public governments, as they enlarge the tax base at almost no cost and are efficient at privately funding urban sprawl in the fastest-growing areas (Dilger, 1992; McKenzie, 1994). Access control, private security and other infrastructure and services represent a substantial capital and recurrent cost for homeowners, which would otherwise have been subsidized by the general tax-paying public. As compensation, homeowners are granted private and exclusive access to their neighborhoods. This ultimately has an impact on property values in both CIDs and gated communities, as their exclusivity is theoretically capitalized in land rent. However, so far there are no empirical data that show how this capitalization fluctuates irrespective of whether the neighborhood is gated or not.

Main trends: booms and burst bubbles

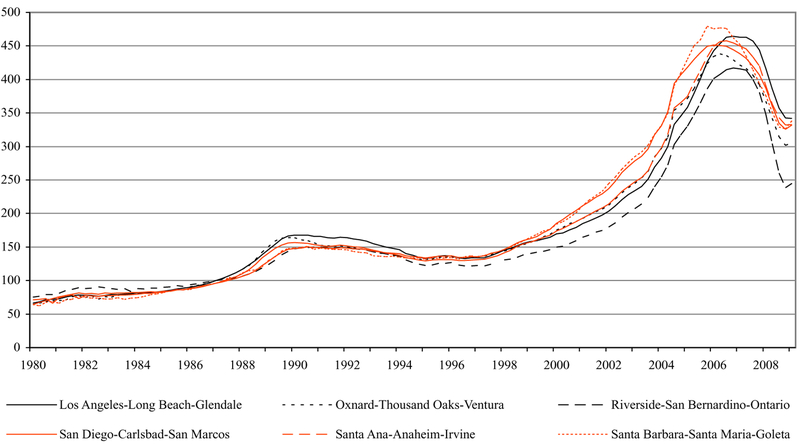

Two main trends affected property values between 1980 and 2008 (see Figure 1). After a continuous increase in the five counties over the first decade, this trend was reversed between 1990 and 1995: the average transaction lost half of its value, a drop that was consistent with the real estate market crisis in Los Angeles, mainly as a result of the burst of a speculative bubble (Jaffee and Kroll, 2001), as well as the 1992 riots, the 1993 earthquake and floods and fires between 1994 and 1995. More importantly, after 1995 and during a decade of geometrical growth of property values, metropolitan areas followed diverging trends. While increases in property value in Santa Barbara and San Diego were well above those in Los Angeles, Oxnard and Santa Ana-Irvine, the fast-growing area of Riverside experienced slower growth in property values. After 2007 and in the wake of the sudden foreclosure crisis, the Santa Barbara, Santa Ana and Oxnard metropolitan areas were affected first, and harder than the Los Angeles and Riverside counties.

Figure 1.

Home price index in southern California’s metropolitan areas (index 100 in 1987, first quarter (source: Freddie Mac, 2009)

Our main line of inquiry being how GCs behave compared to other suburban communities, we rely on a 1980–2008 sample of property values at a disaggregated level. We seek to analyze how GCs differ from other non-gated suburban communities in terms of price increase or depreciative trends.

A long-term comparison of price patterns between gated and non-gated private neighborhoods is an empirical issue that needs further investigation, especially in the context of the 2008 foreclosure crisis. Rising prices would normally have a positive knock-on effect on substitute properties available in the market. A high-end GC in a low-income area of a developing city, for example, will boost local land values. If there are other middle-income housing areas nearby, a GC of sufficient prominence might have an enhancing effect. By contrast, if GCs are of sufficient size that they effectively introduce a layer of superior housing above the existing housing stock, then the existing housing might be marked down. This is more likely to happen in times of excess supply. The mortgage crisis thus offers an opportunity to observe the behavior of property prices over time, during a period in which affluent housing (including gated housing) will be in excess supply in a depressed market, and in which GCs may ultimately fail to protect property values. Data available in 2008 offer an opportunity to monitor the first effects of the crisis on property prices in GCs.

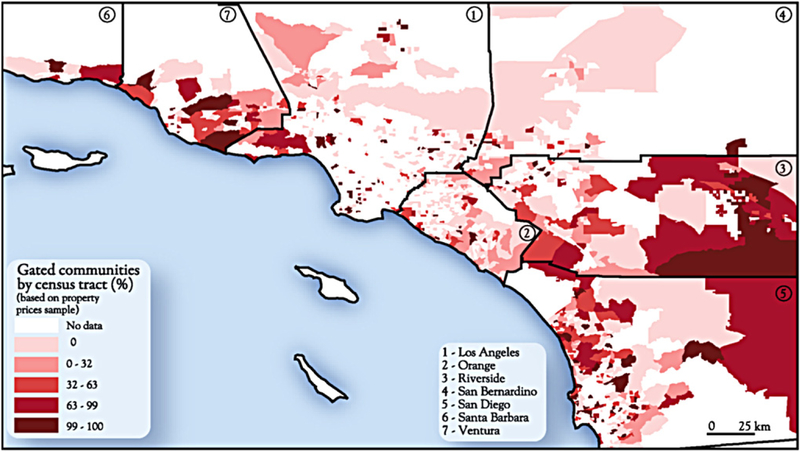

A spatial analysis of price change

In the area defined by seven counties of the larger Los Angeles area in southern California, a sample of 9,694 properties was established, using real estate online listings in 2008 (see methodological appendix). In a fast-growing metropolitan region such as southern California, the sample of properties in residential subdivisions is quite homogeneous in terms of square footage (mean = 2,522 square feet) and year of construction (average date 1993). Property prices, indeed, introduce a great deal of variance into the sample (US $873,000 on average; Std. Dev. = 1,386,744). Following the selection of valid data and aggregation by census tract, the analysis was carried out on a set of 581 census tracts (See Figure 2).3 The overall quality of data has been verified by means of a control variable, an assessment of the ratio of streets in gated communities by census tract (independent variable % gated streets), based on proprietary data.4 In fact, we do not record the 2008 actual transaction prices, as the data set is based on advertised prices. This choice was made taking into account the different variables also collected for each of the advertised properties (gated status of the neighborhood, age of the house, square footage). All these variables were collected at a disaggregated level. We are aware of the bias this might introduce, as during price booms advertised prices may understate transaction prices, while the reverse is true during market slowdowns. The net effect may be to understate the range of variation in house prices. However, this is not a major concern, as we only seek to estimate the trend in median property price changes (ups and downs), these trends being unlikely to be inverted as a result of marginal under- or over-estimation of advertised prices over long periods.

Figure 2.

Properties in gated communities, percentage of sample population, by census tract; (sources: cartography by Le Goix and Averlant, based on GeoLytics, 2003; Census Bureau, 2000; realtor.com, 2008; database: ANR JCJC IP4, Université Paris 1/UMR Géographie-cités 8504)

‘Location, location, location’: price data at the normalized census tract level

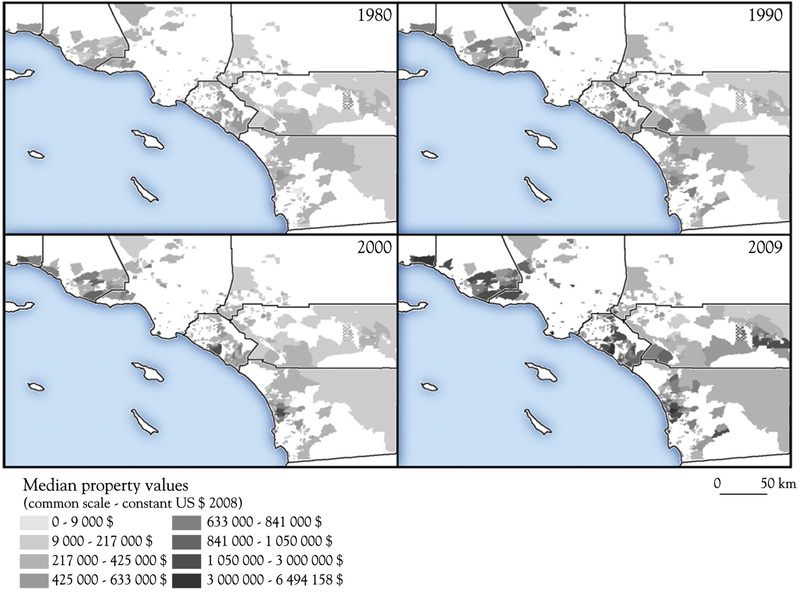

As we seek to analyze price change on the urban edge between 1980 and 2000, a larger geographical scale than the neighborhood or the metropolitan statistical area is required. Property values must be observed not only locally (comparing a gated community with a nearby non-gated community peer-to-peer) but also globally — at the metropolitan-region level — given that residents of gated communities, according to location, express different lifestyle preferences and such GCs serve as a subset of the range of market segments (Le Goix, 2005; Vesselinov and Le Goix, 2007). Nevertheless, several communities in the same area or neighborhood often reflect the same socio-economic patterns and the same market segment (see Figure 3). As a consequence, at the very local level, the question is whether a price premium benefit for a particular GC might derive from its gates and walls, or from the general effect of location rent in the metropolitan area (location advantages and municipal amenities). Such contextual effects are well described by hedonic modeling and multilevel analyses of prices that take into account distances from amenities and local externalities in the valuation of a residential property (Orford, 2002). We have to ensure that a positive price change identified for a specific gated enclave is consistent with global patterns of price change in a metropolitan area in order to determine whether a gated enclave is more efficient at generating property value than a non-gated master-planned community, everything else being equal at the metropolitan level.

Figure 3.

Median property values 1980, 1990, 2000 and 2008 compared on a common scale, in census tracts with gated communities (sources: cartography by Le Goix and Averlant, based on GeoLytics, 2003; Census Bureau, 2000; realtor.com, 2008; database: ANR JCJC IP4, Université Paris 1/UMR Géographie-cités 8504)

Such changes in property value have been analyzed over three decades between 1980, 1990 and 2000. Data are available at the normalized census tract geographical level, with historical data fitted into the 2000 census tracts boundaries.5 Historical data are matched to the subset of census tracts for which we have a 2008 property-value profile, based on our own sample. Inflation effects are corrected according to the US government standard price index, and prices are expressed in equivalence with 2008 US dollars (constant prices).6

Local trends

Figure 3 shows that price changes follow divergent trends. On the one hand, some areas experience a continuous increase in property values, especially in coastal tracts with a higher site rental, such as in Santa Barbara/Montecito, Newport Beach area and the southern part of Orange county, as well as the north of the San Diego urbanized area (Encinatas, Rancho Santa Fe and Del Mar). The residential tracts located north of Malibu, west of Los Angeles County and east of Ventura county in the Calabasas/Agoura Hills/Thousand Oaks and Camarillo area have also experienced this trend. In other areas, data show a relative decline in value between 1990 and 2000, followed by an increase in value between 2000 and 2008, especially in the south-west side of Riverside county. Finally, in some areas such as the resort desert city of Palm Springs and its vicinity, where gated communities are a widespread characteristic of the urban landscape, property values were relatively stable until 2000, followed by a significant increase over the last decade.

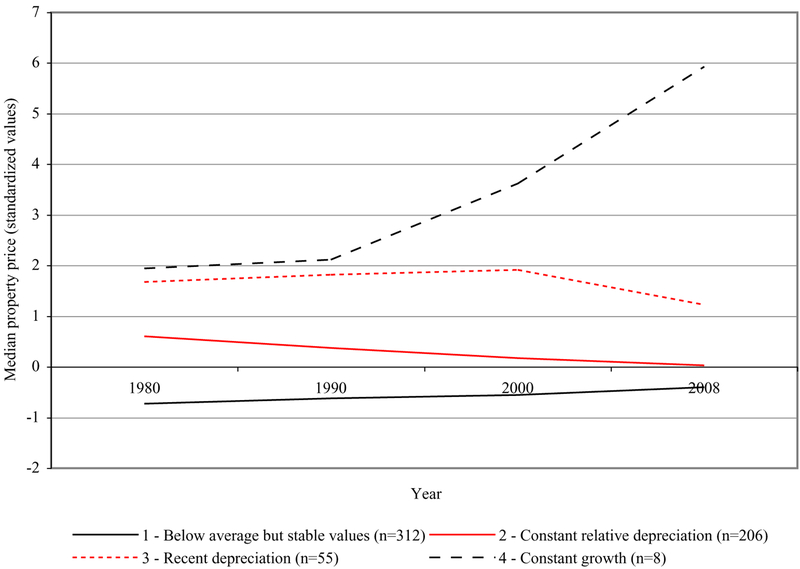

Gated communities protect property values

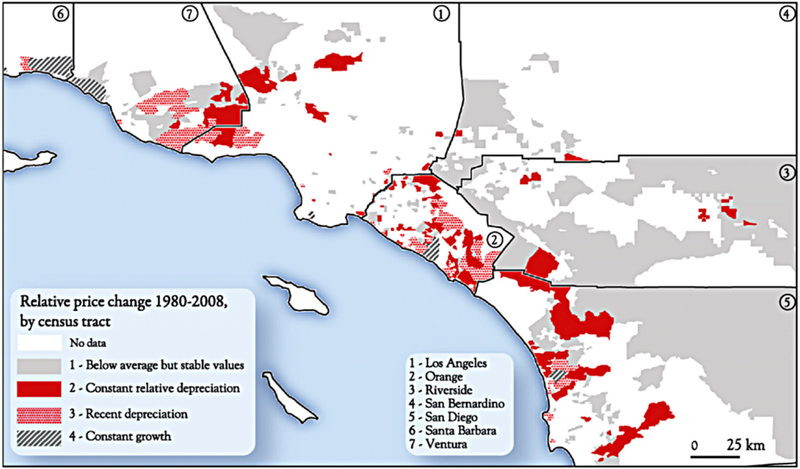

Here, we clarify trends in price change at the tract level and compare these with the percentage of properties in gated communities and non-gated subdivisions by tract. To achieve this, we apply a cluster analysis based on median property prices; cluster profiles are reported in Figure 4. The typology shows four significant patterns of price change. In addition to trends at the metropolitan level reported in Figure 1, the results sort different phases of accelerating growth in price over time.

Figure 4.

Cluster profiles: a typology of price change patterns by census tract (1980–2008) (cluster analysis, ward method, Euclidian distance, r.sq. = 0.72, standardized values)

The standardized profiles show spatial patterns of relative price change (see Figure 5):

Figure 5.

A typology of price change patterns by census tract (1980–2008) (sources: cartography by Le Goix and Averlant, based on GeoLytics, 2003; Census Bureau, 2000; realtor.com, 2008; database: ANR JCJC IP4, Université Paris 1/UMR Géographie-cités 8504)

Cluster 1 records below-average but stable property values in constant US dollars, and this trend specifically applies to the desert side of the suburban areas north of Los Angeles county (Santa Clarita valley and Palmdale area), west San Bernardino, most of Riverside county and the east side of San Diego counties (although these tracts are only partially built up).

Cluster 2 describes a trend of relative depreciation in constant US dollars over a period, especially on the north and the western side of Los Angeles (Agoura Hills and Santa Clarita, for instance) and also in the affluent south of Orange county.

Tracts described in cluster 3 show higher property values during the first three decades, but a recent loss of relative value (2008), everything being equal when compared to the average profile of the cluster analysis. This cluster describes places in Ventura county (Camarillo), the Thousand Oaks and Calabasas area, but also larger gated development areas such as Dove Canyon and Coto de Caza, south of Orange county.

Finally, cluster 4 has a profile of continuous and sustained growth, experienced in areas such as Montecito and Santa Barbara, Oxnard in Ventura county, the south of Irvine and Newport Beach in Orange county, and the Rancho Santa Fe area in San Diego county.

This analysis yields first insights into how tracts with a majority of properties in gated communities compare with properties in non-gated developments in terms of price change profiles. We compare tracts with more than 50% properties in gated communities, and tracts below this threshold. On the one hand, a large majority of tracts show below-average but stable values (cluster 1) or constant relative depreciation (cluster 2); in both cases, gated status does not have a significant impact on property values. In the majority of cases, there is no significant contrast between most gated communities and most non-gated communities: 54% of both gated and non-gated communities experienced ‘below average but stable values’. On the other hand, it is significant that a higher share of census tracts with more than 50% of properties in GCs are found in cluster 3 (higher values between 1980 and 2000, but experiencing recent depreciation) and cluster 4 (constant growth) — 36.4% and 87.5% of all tracts in the clusters, respectively. Although fewer tracts are described by clusters 3 and 4, as both these trends are confined to atypical areas, it is nevertheless significant that in these specific cases, gated communities are more likely to experience ‘recent depreciation’ or ‘constant growth’ than non-gated communities. The statistical relationship is significant, both when considering the percentage of properties in GCs, and the control data set describing the share of gated streets in a census tract (see Tables 1 and 2). These trends are confirmed by a chi-square test, which proves the correlation between gating and favorable trends in price patterns; we also control the effect produced by the date of construction on price trends, and the relationship proves to be weak (see Table 2), as a more recent date of construction might also yield either higher property values (fashionable architecture) or lower values (i.e. obsolescence of the house).

Table 1.

Contingency table for percentage of gated communities and 1980 to 2008 price profiles by census tract (CT)

| Cluster* GC | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Below average but stable values | 209 | 66.9 | 103 | 33.03 | 312 | 100 |

| 2 Constant relative depreciation | 145 | 70.4 | 61 | 29.6 | 206 | 100 |

| 3 Recent depreciation | 35 | 63.6 | 20 | 36.4 | 55 | 100 |

| 4 Constant growth 100 | 1 | 12.5 | 7 | 87.5 | 8 | 100 |

| Total | 390 | 67.1 | 191 | 32.9 | 581 | 100 |

Over-representation is highlighted in italics.

Table 2.

Statistical relations at the census tract level (N = 581 spatial units)

| Price Patterns and % Gated Streets | Price Patterns and % Properties in GCs | % Properties in GCs and Median Building Date | Price Patterns and Median Building Date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clusters X | 1–2–3–4 | 1–2–3–4 | 1–2–3–4 | |

| −50% | ||||

| Max = 2008 | Max = 2008 | |||

| Chi2 (observed value) | 21.40 | 12.12 | 30.36 | 21.8 |

| DF | 3 | 3 | 3 | 9 |

| p-value | <0.0001*** | 0.007** | <0,0001*** | 0.0093 not significant |

Blakely and Snyder (1997) were among the first to establish that there are different types of gated communities in the United States. A vast majority of GCs are average standardized products for the middle and upper-middle class, and a minority are high-end, exclusive, expensive hideaways for wealthier owners (Sanchez and Lang, 2005). This is especially true in southern California (Le Goix, 2005). Indeed, analyses show that price trends are on average undifferentiated, regardless of whether communities are gated or not. As shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4, the majority of average middle-class gated enclaves located within the continuum of low to average median property values do not contribute to a measurable price premium between 1980 and 2008. Nevertheless, results show that in some very significant cases, GCs do contribute to fuelling price growth (in clusters 3 and 4). This is especially true in the most desired locations in the metropolitan areas, such as in the south of Orange county, and in the Santa Barbara, Calabasas (west Los Angeles) or Thousand Oaks (Ventura county) areas.

Some trends clearly emerge from this analysis of price patterns between 1980 and 2008 in gated communities versus non-gated CIDs. First, GCs are very heterogeneous and diverse in kind, ranging from average standardized products for the middle class to high-end coastal communities. It is significant that gated communities were more likely than non-gated communities to have experienced either ‘recent depreciation’ in the wake of the foreclosure crisis, or ‘constant growth’. But on average, the wealthier the area, the more GCs contributed to fuelling price growth, as these GCs offer better rent-gap opportunities and are situated in more desired locations in metropolitan areas. There is a significant correlation between gating and securing a neighborhood and price growth trends at the census tract level.

Gated communities emphasize price inequalities at the local level

In a second step of the analysis, we measured the level of price discontinuity between two adjacent tracts using the price distance index (PDI) — the absolute value of median price difference between adjacent tracts. Where PDIs are significantly high, there is a statistically significant level of dissimilarity between two contiguous tracts that can then be mapped as a line segment that clearly indicates the level of discontinuity. The spatial analysis in this part aims at measuring the contribution of topological distance (census tract boundaries) on price differentiation patterns.

Methodology: a price distance index

The analysis of price change aims to compare census tracts with an over-representation of properties in GCs (above a threshold of 50%) and census tracts with an over-representation of non-gated subdivisions. We implement a price distance index (PDI) based on a methodology developed for price change patterns analysis in downtown Paris (Guérois and Le Goix, 2009).

Analysis at neighborhood level primarily measures the distance between prices in one census tract and adjacent (gated or non-gated) tracts. Segregation, concentration and dissimilarity indices are known to be sensitive to spatial auto-correlation (Apparicio, 2000; Grasland et al., 2000; Nelson et al., 2004). It is also well established that these indices usually ignore spatial patterns, depending on the level of spatial auto-correlation (White, 1983; Massey and Denton, 1988; Nelson et al., 2004). To study differentiation and segregation patterns at a local level, we therefore need to implement a function of topological distance (adjacency) in the measure to account for gradient and proximity effects. The proposed local PDI circumscribes usual spatial auto-correlation bias, as it measures the level of price discontinuity between two adjacent tracts.7 We then compare the PDIs and the spatial distribution of gated areas and non-gated areas.

Results: a typology of price distance indices

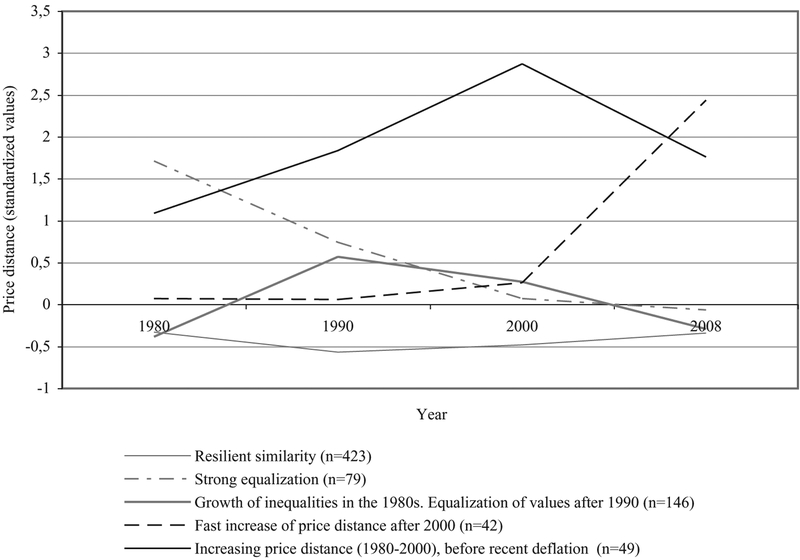

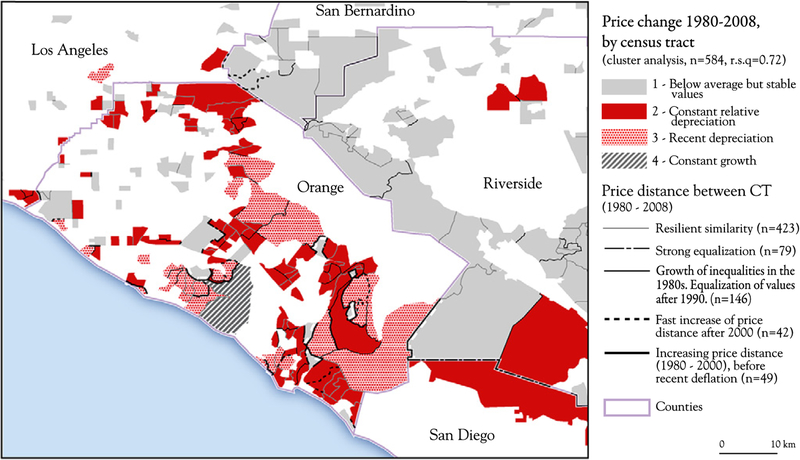

In order to compare values over time between census tracts with gated communities and non-gated areas, the PDI between tracts in 1980, 1990, 2000 and 2008 (see Figure 6 and Figure 7) is classified by means of a cluster analysis. The focus of the method is such that each cluster summarizes a trend, thus describing how census tracts in the same area have diverging or converging property values (relative differentiation between median property values between two adjacent tracts).

Figure 6.

Cluster profiles: A typology of price distance index (cluster analysis, ward method, Euclidian distance, r.sq. = 0.58, standardized values)

Figure 7.

Map of price change patterns and price distance index, south of Los Angeles (Orange, San Diego and Riverside counties, 1980–2008) (sources: cartography by Le Goix and Averlant, based on GeoLytics, 2003; Census Bureau, 2000; realtor.com, 2008; database: ANR JCJC IP4, Université Paris 1/UMR Géographie-cités 8504)

A first cluster results from the classical patterns of positive spatial auto-correlation: the majority of tracts experience the same property price trends as their adjacent neighbors. Indeed, everything being equal, the vast majority of segments between tracts (57.2%) belong to a pattern called resilient similarity, which means that median prices remain more or less equivalent on both sides of the tract boundary. Thus, values in adjacent tracts experience a parallel increase during periods of price booms, and values decrease in sync during crisis.

Cluster 2 describes strong equalization patterns. A constant trend of decreasing inequalities in price occurs over the entire period between two adjacent tracts (10.7% of all segments).

Cluster 3 describes a dynamic close to the average profile, showing a growth of inequalities in the 1980s, and then an equalization of values (1990–2008) (frequency = 19.8% of all segments). This cluster particularly includes newer subdivisions on the urban edge. After the development of pioneer subdivisions in rural and desert areas (favoring higher differentiation of prices), tract-by-tract contagion of suburban subdivisions produced a diffusion of price patterns (similar houses, similar subdivisions, similar property owners, similar developers on the urban edge), thus favoring a homogenization of prices between adjacent neighborhoods. This pattern seems quite common on the outskirts of the urban edge, which is consistent with the spatial diffusion of planned subdivision, both gated and non-gated.

Cluster 4 describes neighborhoods where price dissimilarities boomed after 2000, following a stable system of price homogeneity during the first two decades (fast increase of price distance after 2000, frequency = 5.7%). On average, the PDI has increased from 0 to almost 2.5 standard deviation, thus corresponding either to urban renewal areas with new subdivisions in a previously built-up homogeneous environment, or new pioneer subdivisions in rural locations.

Cluster 5 describes boundaries between tracts where local price dynamics fuel spatial differentiation patterns over the first 20 years, followed by a relative equalization of prices between 2000 and 2008 (increasing price distance, 1980–2000, before recent deflation, frequency = 6.6%).

Are gated communities more likely to generate price inequalities?

Based on this typology we analyze how GCs and non-gated subdivisions are correlated with prices dissimilarities (PDIs) over time. In order to offset the risk of ecological fallacy, the typology of the PDI only accounts for the local context of price patterns in which GCs and other subdivisions are located. We consider the percentage of properties located in gated communities (see Table 3). The statistical relationship is shown to be very strong (see Table 4) for both percentage properties in GCs and percentage of gated streets (control variable).

Table 3.

properties in GCs and price differentiation patterns*

| Price Distance Index (Clusters) % of Properties in GCs | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 1 Resilient similarity | 69 | 16.3 | 84 | 19.9 | 270 | 63.8 | 423 | 100 |

| 2 Strong equalization pattern | 22 | 27.9 | 23 | 29.1 | 34 | 43.0 | 79 | 100 |

| 3 Growth of inequalities in the 1980s; equalization of values after 1990 | 21 | 14.4 | 35 | 24.0 | 90 | 61.6 | 146 | 100 |

| 4 Fast increase of price distance after 2000 | 70 | 23.8 | 19 | 45.2 | 13 | 30.9 | 42 | 100 |

| 5 Increasing price distance (1980–2000) before recent deflation | 6 | 12.2 | 19 | 38.8 | 24 | 49.0 | 49 | 100 |

| Total | 128 | 17.4 | 180 | 24.36 | 431 | 58.32 | 739 | 100 |

Contingency table of price distance index and percentage of properties in gated communities on both sides of the census tract boundaries (N = 747 line segments); overrepresentation is highlighted in italics. Results were analyzed at the segment level (line segment between adjacent tracts): more than 50% of properties in GCs on both sides of the segment; more than 50% on one side only; and less than 50% of properties in GCs on both sides.

Table 4.

Chi-square test on boundaries between CT level

| Price Distance (Clusters) and Gated Communities | % Gated Streets | % Properties in GCs* |

|---|---|---|

| N | 739 | 739 |

| Clusters X | 1–2–3–4–5 | 1–2–3–4–5 |

| few GCs on both sides | few GCs on both sides | |

| Chi-square (Observed value) | 35.5 | 32.46 |

| DF | 8 | 8 |

| p-value | <0.0001*** | <0.0001*** |

The same categorization for the control variable as for the percentage of gated streets on both sides of the census tract boundaries, but with a 25% threshold only, as a 50% threshold does not yield significant results.

Our main line of inquiry has been to analyze to what extent GCs are different from other non-gated suburban subdivisions, and whether the enclosure contributes significantly to price change patterns in favor of GCs. A threefold answer can be provided, which can be illustrated with examples from Orange county (see Figure 7).

First, data show strong evidence that GCs correlate with stronger price differentiation patterns, compared to adjacent non-gated subdivisions. In areas where the percentage of GCs lies above the threshold of 50% properties in gated communities by census tract, there is a higher probability of increased price dissimilarities, as described in cluster 4 (fast increase of price distance after 2000). GCs are more likely to be found in local contexts that introduce greater heterogeneity and instability in price patterns, thereby contributing to a local increase in price inequality that destabilizes price patterns at neighborhood level, compared to non-gated communities. This is the case, for instance, in the affluent communities of Dove Canyon and Coto de Caza, which differ from the rest of the Rancho Santa Margarita area. This trend is spatially associated with cluster 5 (increased price distance from 1980–2000 before deflation of the PDI). Furthermore, cluster 5 is more likely to be found where there are only GCs on one side of the census tract boundaries. For instance, the newly developed Newport Coast–Pelican Hills Master Planned Community (Newport Beach) differs strongly from the rest of the Newport and Irvine area, showing constant price growth and an increased PDI.

Secondly, cluster 2 shows that strong equalization patterns also occur between 1980 and 2008. Everything else being equal, segments in cluster 2 are more likely to separate either census tracts with GCs on both sides or census tracts with GCs on one side only. As shown in Figure 7, they relate to areas — for instance the central area of Orange county (Santa Ana, Tustin, Orange and Irvine) — in which gated communities are prevalent morphologies in denser, clustered or in-fill developments, which produce a spatial diffusion of gated communities (contagion effect) and thereby lead to a homogenization of price patterns. This may be explained by a convergence of factors at different geographical levels: the attractiveness of GCs to prospective buyers, the risk of negative spillovers for those living near a GC (Helsley and Strange, 1999), as well as the price premium generated by the gated neighborhood, all fuelled a powerful contagion effect (Vesselinov and Le Goix, 2009). As far as crime is concerned, for instance, the deterrent effect of gates (Atlas and Leblanc, 1994) leads to crime being diverted to adjacent non-gated communities (Helsley and Strange, 1999). This creates a major spillover for non-residents, and nearby communities might react by building their own gates. At the metropolitan level, in areas that already display strong segregation patterns, newer developments adopt a model that has been successful in the vicinity, thereby targeting niche markets of prospective buyers with rent-seeking strategies. To a certain extent, some older neighborhoods nearby may retrofit gates and walls in order to anticipate and avoid the negative spillover effects of crime and declining property values. Among other reasons that fuel the contagion effect, fiscal reasons seem paramount; GCs are a result of planning strategies by suburban local bodies of government (counties and municipalities). These developments reduce public financial responsibility by providing their own security, infrastructure and services, while generating new fiscal revenues. In compensation, homeowners are granted exclusive access to their neighborhoods, a condition that enhances location rent and has a positive effect on property values.

Finally, GCs are least likely to be found in local contexts of price homogenization. Indeed, everything else being equal, segments between tracts with a below-the-threshold share of 50% of properties in GCs are in relative terms most likely to belong to cluster 1 (resilient similarity) and cluster 3 [growth of inequalities in the 1990s, then equalization of values (1990–2008)]: this is the case in areas of lower property values (west of Riverside and San Bernardino counties), but also along the northern boundaries of Orange county, in a depreciative context affecting mostly non-gated subdivisions.

The PDI analysis highlights how price trends may diverge in different areas with an over-representation of gated communities. On the one hand, GCs are located in local contexts that introduce greater heterogeneity and instability in price patterns, thereby contributing to a local increase of price inequality that destabilizes the price patterns at neighborhood level. On the other hand, GCs are also frequently found in contexts that show a very strong stability in terms of producing price homogeneity at the local level.

Conclusion

Gated and non-gated private neighborhoods (non-gated CIDs) share the overall legal and contractual structure of a private neighborhood designed to avoid negative externalities, but are discriminatory because the gating of a private neighborhood might generate a higher price premium and more price stability over time. Based on this background hypothesis, we analyzed how to differentiate gated communities from non-gated communities in terms of patterns of change in property values.

The results yielded two series of conclusions. First, along the axis of price differentiation, gated communities are more likely to generate inequalities than non-gated CIDs, and are indeed more likely to produce a filtering of residents, which has a profound impact on segregation patterns. The dynamics of prices in gated communities show that homeowners are more likely to profit from price bubble periods, and more likely to resist a sudden drop in value during downturns, such as the foreclosure crisis, at the same time contributing not only status and ‘snob value’ but also providing a means to differentiate themselves from others economically.

Secondly, a dualism results from the contexts in which gated communities are located. On the one hand, data show new empirical evidence of the highly theoretical contagion effect produced by gating. A strongly positive spatial auto-correlation pattern of property values is especially true in denser suburban areas with more in-fill redevelopments and closer proximity between subdivisions. On the other hand, GCs also correlate with stronger price differentiation patterns, especially in recently developed large master-planned communities, when values are compared to those of nearby non-gated subdivisions. This yields evidence that price premiums for GCs are detrimental to property values in nearby non-gated developments and demonstrates a long-standing hypothesis about the unfavorable effects of gated communities on the value of properties located outside GCs’ walls. This is particularly true in lower-density suburbs, in communities on the urban edges or along the coastline.

Acknowledgments

This article is part of a research program funded by the US NICHD, titled ‘Socio-Economic Impact of Gated Communities on American Cities’. Data and methodological research have also been funded under the ANR (French National Research Agency) 2007–10 research program ‘IP4 — Public–Private Interactions in the Production of Suburban Areas’. This support is gratefully acknowledged.

Appendix — Methodology

Identifying properties in gated and non-gated suburban planned communities

In order to identify properties in gated and in non-gated suburban planned communities in a data set, we extracted our main information from realtor.com online listings, which are operated by a US federation of real estate agents. The listings of properties for sale in the United States are publicly available online. These public listings were analyzed for single-family homes in order to achieve a sample of properties in targeted subdivisions. Based on the common definition of CIDs, we extracted properties in neighborhoods sharing a privately operated ‘community amenity’ (as referenced in listings), such amenities being good proxies to identify CIDs. Properties were geo-coded at the address level. By doing so, we obtained general data describing the property, community information (gating, private streets, leisure amenities), as well as data on the date of construction, the square footage of each house, and estimated property prices (advertised price in November 2008) — thus taking into account the first phases of the mortgage crisis. We characterized each property with a dummy variable (independent variable property in GC) according to the available information:

either as a property in a gated subdivision, where any of the words ‘guarded’, ‘gated’, ‘patrol’, ‘security features’ and ‘private street/lane’ are explicitly mentioned in the property description (3,947 properties, 40.7%);

or as a property in a non-gated subdivision in all other cases (5,747 properties, 59.3%).

Data were initially aggregated and matched to 992 census tracts. This geographical level was chosen for sampling reasons so as to avoid having too many geographical units with a small number of properties. We disregarded census tracts containing less than three properties and aggregated property values on the basis of median value in order to avoid obvious bias being introduced by a single exceptional property in a census tract. The final data set contained 581 census tracts (see Figure 2).

Footnotes

This article elaborates on Le Goix (2007), seeking to analyze price change and gated communities from a different perspective. Previous work focused on analyzing the impact of the legal structuring of gated communities on property values, with a special focus on the relationships between gating, decreasing property values and obsolescence of a neighborhood. The latter issue should be seen as particularly significant in private neighborhoods where all infrastructures are paid for and maintained by residents’ fees. This article takes a different perspective: on the one hand we compare price patterns in both gated and non-gated CIDs, which are identified by means of an ad hoc database; on the other hand we examine trends by means of a multivariate analysis, in order to better characterize price change in neighborhoods.

Incorporation is the legal process by which unincorporated land (under county jurisdiction) becomes a city, once approved by the state (in California, Local Agency Formation Commissions — LAFCOs — are in charge of supervising the process) and by two-thirds of voters. A new municipality can either be granted a charter by the state, as is the case with large cities, or be incorporated under general law, which is usually the case.

Our data set underestimates the number of properties in gated communities: recent field surveys (April and July 2010, with 618 subdivisions surveyed) have shown that 10% of subdivisions in the database are classified as non-gated, whereas they are actually gated, and only 3% of visited subdivisions are mistakenly classified as gated in the database.

These data come from Thomas Bros. Maps®. The company publishes interactive maps that identify private streets. Access to vector maps allows spatial queries of gated streets, in order to identify gated neighborhoods. The files also contain information related to military bases, airfields, airports, prisons, amusement parks and colleges, some of which may also contain private streets with restricted access. Aerial photographs (for example, Google Earth, MapQuest) are further used to help identify GCs as opposed to non-residential gated areas (Vesselinov and Le Goix, 2009).

GeoLytics is a commercial organization that provides a normalized database in which data for the decennial census are matched to the 2000 census tract boundaries. Variables selected were: Median Value All Owner Occupied Housing Units (2000); Median Value Owner Occupied (1990); Median Value Non-Condo Housing Units (1980) — Neighborhood Change Database (1970–2000) and 1980 census in 2000 Boundaries (2003). As census tract boundaries have changed considerably over time, a remapping of former census boundaries according to 2000 definitions is required in order to compare variables across time for a given location accurately. The incomplete coverage by census tract in the 1970 and 1980 censuses, which contain only data for urban areas, is an additional difficulty. The normalization of historic tract data to 2000 tract boundaries starts with an estimate based on block-level weighted geographic data. The 1970 and 1980 boundary files are related to the 1990 boundary files using correspondence files produced by the Census Bureau, which are given a computed tract weight. A detailed methodology is published online [WWW document], URL http://www2.urban.org/nnip/ncua/ncdb/AppendixJ.pdf (accessed: June 2010).

Source: Consumer Price Index, 2009 (US Bureau of Labor Statistics: http://www.bls.gov). US $1 in 2008 is equivalent to $0.38 in 1980, $0.61 in 1990 and $0.80 in 2000.

The price distance index (PDI), which is, in fact, the absolute value of median price difference between tracts, will be our main indicator in this comparison between census tracts with gated communities and census tracts with non-gated subdivisions. It has been computed at the normalized 2000 census tract level. For each year (1980, 1990, 2000 and 2008), the index is constructed by subtracting median property values in a given tract and median property values in an adjacent tract and is the absolute value of the difference for each spatial unit (the line segment, or boundary, between two adjacent tracts).

Contributor Information

Renaud Le Goix, Department of Geography, University of Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, UMR 8504 Géographie-Cités, 191 Rue Saint Jacques, 75005 Paris, France.

Elena Vesselinov, Department of Sociology, Queens College and the Graduate Center, City University of New York, Flushing, NY 11367, New York, USA..

References

- Altini GR and Akindele OA (2005) The effect that enclosing neighbourhoods has on property values Paper presented at the International Symposium on ‘Territory, Control and Enclosure’, Pretoria, South Africa, 28 February–2 March. [Google Scholar]

- Apparicio P (2000) Indices of residential segregation: an integrated tool in geographical information system. Cybergeo 134 [WWW document]. URL http://www.cybergeo.eu/index12063.html (accessed December 2009). [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson R and Blandy S (2005) Introduction: international perspectives on the new enclavism and the rise of gated communities. Housing Studies 202, 177–86. [Google Scholar]

- Atlas R and Leblanc WG (1994) The impact on crime of streets closures and barricades: a Florida case study. Security Journal 5, 140–5. [Google Scholar]

- Bagaeen S. and Uduku O (eds.) (2010) Gated communities: social sustainability in contemporary and historical gated developments Earthscan, London. [Google Scholar]

- Berding TP (1999) The uncertain future of common interest developments. Echojournal: A Journal for Community Association Leaders 5. [Google Scholar]

- Bible DS and Hsieh C (2001) Gated communities and residential property values. Appraisal Journal 692, 140–5. [Google Scholar]

- Billard G, Chevalier J and Madore F (2005) Ville fermée, ville surveillée: la sécurisation des espaces résidentiels en France et en Amérique du Nord. Presses Universitaires de Rennes, Rennes. [Google Scholar]

- Blakely EJ and Snyder MG (1997) Fortress America: gated communities in the United States Brookings Institution Press, Washington DC, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Blandy S (2006) Gated communities in England: historical perspectives and current developments. GeoJournal 66.1/2, 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Blinnikov M, Shanin A, Sobolev N and Volkova L (2006) Gated communities of the Moscow green belt: newly segregated landscapes and the suburban Russian environment. GeoJournal 66.1/2, 65–81. [Google Scholar]

- Brower T (1992) Communities within the community: consent, constitutionalism, and other failures of legal theory in residential associations. Land Use and Environmental Law Journal 72, 203–73. [Google Scholar]

- Caldeira TPR (2000) City of walls: crime, segregation, and citizenship in São Paulo. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau Census (2000) Census of population and housing 1980, 1990, 2000 [WWW document]. URL http://factfinder2.census.gov (accessed December 2009).

- Cervero R and Duncan M (2004) Neighbourhood composition and residential land prices: does exclusion raise or lower values? Urban Studies 412, 299–315. [Google Scholar]

- Claessens B (2009) Systematising trans/interdisciplinary gated community research: towards a holistic understanding of the complex social phenomenon ‘gated community’ Paper presented at the 5th International Conference of the Research Network Private Urban Governance and Gated Communities on ‘Redefinition of Public Space Within the Privatization of Cities’, University of Chile, Santiago, 30 March–2 April. [Google Scholar]

- Cséfalvay Z (2009a) Demythologising gated communities in Budapest In Smigiel C (ed.), Gated and guarded housing in Eastern Europe, Forum ifl, Selbstverlag des Leibniz-Instituts für Länderkunde, Leipzig. [Google Scholar]

- Cséfalvay Z (2009b) The magic of trilemma: urban governance and gated communities Paper presented at the International Conference on ‘City Futures 2009’, Madrid, 4–6 June. [Google Scholar]

- Dilger RJ (1992) Neighborhood politics: residential community association in American governance. New York University Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Foldvary F (1994) Public goods and private communities: the market provision of social services Edward Elgar, Aldershot. [Google Scholar]

- Fox-Gotham K (2000) Urban space, restrictive covenants and the origins of racial segregation in a US city, 1900–50. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 243, 616–33. [Google Scholar]

- Freddie Mac House Price Index (FMHPISM) Data (2009) Freddie Mac [WWW document]. URL http://www.freddiemac.com/finance/fmhpi/ (accessed December 2011).

- GeoLytics Inc (2003) Neighborhood change database (1970–2000) and 1980 census in 2000 boundaries [WWW document]. URL http://www.geolytics.com/USCensus,Neighborhood-Change-Database-1970-2000,Products.asp (accessed December 2009).

- Glasze G (2005) Some reflections on the economic and political organisation of private neighbourhoods. Housing Studies 202, 221–33. [Google Scholar]

- Glasze G (2006) Segregation and seclusion: the case of compounds for western expatriates in Saudi Arabia. GeoJournal 66.1/2, 83–8. [Google Scholar]

- Glasze G, Frantz K and Webster CJ (2002) The global spread of gated communities. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 293, 315–20. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon TM (2004) Moving up by moving out? Planned developments and residential segregation in California. Urban Studies41.2, 441–61. [Google Scholar]

- Grasland C, Mathian H and Vincent J-M (2000) Multiscalar analysis and map generalisation of discrete social phenomena: statistical problems and political consequences. Statistical Journal of the United Nations ECE 17, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Guérois M and Le Goix R (2009) La dynamique spatio-temporelle des prix immobiliers à différentes échelles: le cas des appartements anciens à Paris (1990–2003). Cybergeo 470 [WWW document]. URL http://www.cybergeo.eu/index22644.html (accessed December 2009). [Google Scholar]

- Helsley RW and Strange WC (1999) Gated communities and the economic geography of crime. Journal of Urban Economics 461, 80–105. [Google Scholar]

- Ihlanfeldt KR (2004) Introduction: exclusionary land-use regulations. Urban Studies 412, 255–9. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee DM and Kroll CA (2001) The bubble has burst — how will California fare? Research Report, Fisher Center for Real Estate and Urban Economics, University of California, Berkeley, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Kato Y (2006) Planning and social diversity: residential segregation in American new towns. Urban Studies43.12, 2285–99. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy DJ (1995) Residential associations as state actors: regulating the impact of gated communities on nonmembers. Yale Law Journal 1053, 761–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby A, Harlan SL, Larsen L, Hackett EJ, Bolin B, Nelson A, Rex T and Wolf S (2006) Examining the significance of housing enclaves in the metropolitan United States of America. Housing, Theory and Society 231, 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Lacour-Little M and Malpezzi S (2001) Gated communities and property values. Research report, Wells Fargo Home Mortgage and Department of Real Estate and Urban Land Economics, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI. [Google Scholar]

- Le Goix R (2003) Les gated communities aux Etats-Unis: morceaux de villes ou territoires à part entière? PhD thesis, Department of Geography, Université Paris 1 Panthéon–Sorbonne, Paris. [Google Scholar]

- Le Goix R (2005) Gated communities: sprawl and social segregation in southern California. Housing Studies 202, 323–43. [Google Scholar]

- Le Goix R (2007) The impact of gated communities on property values: evidences of changes in real estate markets (Los Angeles, 1980–2000) In Cybergeo, Proceedings of the Conference on Systemic Impacts and Sustainability of Gated Enclaves in the City, Pretoria, South Africa, 28 February–3 March. [Google Scholar]

- Le Goix R and Callen D (2010) Production and social sustainability of private enclaves in suburban landscapes: local contexts and path dependency in French and US long-term emergence of gated communities and private streets In Bagaeen S and Uduku O (eds.), Gated communities: social sustainability in contemporary and historical gated developments, Earthscan, London. [Google Scholar]

- Le Goix R and Webster CJ (2008) Gated communities. Geography Compass 24, 1189–214. [Google Scholar]

- Low S (2001) The edge and the center: gated communities and the discourse of urban fear. American Anthropologist 1031, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Low S (2003) Behind the gates: life, security, and the pursuit of happiness in fortress America Routledge, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Low S (2006) Towards a theory of urban fragmentation: a cross-cultural analysis of fear, privatization, and the state In Cybergeo, Proceedings of the Conference on Systemic Impacts and Sustainability of Gated Enclaves in the City, Pretoria, South Africa, 28 February–3 March. [Google Scholar]

- Low S (2009) An interdisciplinary framework for the study of private housing schemes: integrating anthropological, psychological and political levels of theory and analysis Paper presented at the 5th International Conference of the Research Network Private Urban Governance and Gated Communities on ‘Redefinition of Public Space Within the Privatization of Cities’, University of Chile, Santiago, 30 March–2 April. [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS and Denton NA (1988) The dimensions of residential segregation. Social Forces 67, 281–315. [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS and Denton NA (1993) American apartheid: segregation and the making of the underclass Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie E (1994) Privatopia: homeowner associations and the rise of residential private government. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT and London. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie E (2003) Common interest housing in the communities of tomorrow. Housing Policy Debates 14.1/2, 203–34. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie E (2005) Constructing the Pomerium in Las Vegas: a case study of emerging trends in American gated communities. Housing Studies 202, 187–203. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie E (2006a) Emerging trends in state regulation of private communities in the U.S. GeoJournal 66.1/2, 89–102. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie E (2006b) The dynamics of privatopia: private residential governance in the USA In Glasze G, Webster CJ and Frantz K (eds.), Private cities: local and global perspectives, Routledge, London. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie E (2006c) The dynamics of privatopia: private residential governance in the USA In Glasze G, Webster CJ and Frantz K (eds.), Private cities: local and global perspectives, Routledge, London. [Google Scholar]

- Miller DJ (1989) Life cycle of an RCA In Residential Community Associations: Private Governments in the Intergovernmental System? Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Miller GJ (1981) Cities by contract The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson AC, Dawkins CJ and Sanchez TW (2004) Urban containment and residential segregation: a preliminary investigation. Urban Studies 41, 423–39. [Google Scholar]

- Newman O (1996) Creating defensible space US Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research, Institute for Community Design Analysis, Center for Urban Policy Research, Rutgers University, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Newman O, Grandin D and Wayno F (1974) The private streets of St Louis. National Science Foundation, Institute for Community Design, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Orford S (2002) Valuing locational externalities: a GIS and multilevel modelling approach. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 291, 105–27. [Google Scholar]

- Purcell M (1997) Ruling Los Angeles: neighborhood movements, urban regimes, and the production of space in southern California. Urban Geography 188, 684–704. [Google Scholar]

- Raposo R (2006) Gated communities, commodification and aestheticization: the case of the Lisbon metropolitan area. GeoJournal 66, 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Realtor.com (2008) National Association of Realtors [WWW document]. URL http://www.realtor.com (accessed December 2008).

- Rosen G and Razin E (2009) The rise of gated communities in Israel: reflections on changing urban governance in a neo-liberal era. Urban Studies 468, 1702–22. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez T and Lang RE (2005) Security vs. status? A first look at the census’ gated community data. Journal of Planning Education and Research 243, 281–91. [Google Scholar]

- Stoyanov P and Frantz K (2006) Gated communities in Bulgaria: interpreting a new trend in post-communist urban development. GeoJournal 66.1/2, 57–63. [Google Scholar]

- Vesselinov E, Cazessus M and Falk W (2007) Gated communities and spatial inequality. Journal of Urban Affairs 292, 109–27. [Google Scholar]

- Vesselinov E and Le Goix R (2007) Gated communities and homogeneity in Las Vegas and Phoenix. Paper presented at the 4th International Conference of the International Research Network Private Urban Governance on ‘Private Urban Governance and Gated Communities’, University Paris 1, Panthéon–Sorbonne, Paris, 5–8 June 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Vesselinov E and Le Goix R (2009) From picket fences to iron gates: suburbanization and gated communities in Phoenix, Las Vegas and Seattle. GeoJournal 772, 203–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster CJ (2001) Gated cities of tomorrow. Town Planning Review 722, 149–70. [Google Scholar]

- Webster CJ (2002) Property rights and the public realm: gates, green belts, and Gemeinschaft. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 293, 397–412. [Google Scholar]

- Webster CJ and Le Goix R (2005) Planning by commonhold. Economic Affairs 254, 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Webster CJ, Wu F and Zhao Y (2006) China’s modern walled cities In Glasze G, Webster CJ and Frantz K (eds.), Private cities: local and global perspectives, Routledge, London. [Google Scholar]

- White MJ (1983) The measurement of spatial segregation. American Journal of Sociology 885, 1008–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wu F (2005) Rediscovering the ‘gate’ under market transition: from work-unit compounds to commodity housing enclaves. Housing Studies 202, 235–54. [Google Scholar]