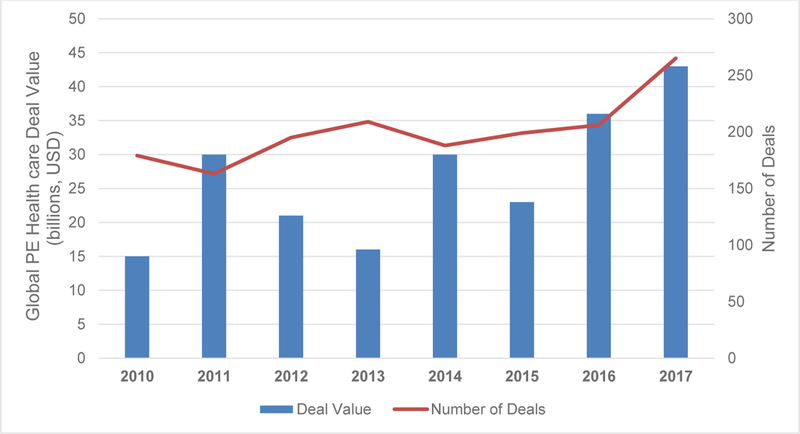

Much of the US health care system relies on private physician practices. Little is known about the role of private equity in today’s health care delivery system. From 2010 to 2017, the value of private equity deals involving the acquisition of a health care–related company (most involving physician practices and hospitals) increased 187% and reached $42.6 billion, while the number of health care deals increased by 48% (Figure).1 Given the increasing role of this type of financing, physicians and policy makers should understand private equity, common strategies used by its firms, and the potential risks and benefits for physicians and patients.

Figure. Total Health Care Deal Value and Number of Deals, 2010-2017*.

* Data from Bain Insights Report on Global Healthcare Private Equity and Corporate M&A Report 2018. Between 2010 and 2017, the total value of private equity deals in health care has increased 187% while the total number of private equity deals in health care has increased by 48%. Abbreviations: PE = private equity.

What Is Private Equity?

Private equity firms use capital from institutional investors to invest in private companies with potential to return a profit. That potential is realized if private equity firms manage to add value to the company and subsequently sell their stake at a price higher than the purchase, typically within 3 to 7 years. Private equity deals range from tens to hundreds of millions of dollars and are expected to deliver 20% to 30% returns. Private equity firms use several strategies to raise the value of practices, such as reducing costs (often through layoffs) and improving efficiency by consolidating and internalizing previously outsourced processes like billing. However, in physician practice acquisitions, key private equity tactics also include increasing prices and volume. Private equity firms typically purchase an established group practice and acquire smaller practices to establish regional brands that can exercise greater bargaining power with insurers and medical suppliers. As ownership shifts from physicians to private equity firms, more emphasis might be placed on extracting higher contracted payment rates, lowering overhead, and increasing volume and ancillary revenue streams (eg, imaging or procedures).

Growth of Private Equity in Health Care

In 2017, the value of private equity deals in health care totaled $42.6 billion globally, up 17% from 2016.1 The number of deals also increased to 265, from 206 in 2016. Health care deals comprised 18% of all private equity deals globally in 2017.1 Physicians, hospitals, and other facilities accounted for the most buyout activity, with 139 of the 265 health care private equity deals announced worldwide involving care delivery companies.1 Sectors of interest include retail health, behavioral health, free-standing medical centers (eg, for ambulatory surgery), and physician practice management, especially in highly paid specialties such as dermatology, ophthalmology, orthopedics, gastroenterology, urology, and allergy.

Several attributes of health care markets may help to explain why private equity investment in health care is increasing. First, groups that deliver care are often fragmented geographically, which allows private equity funds to consolidate market power and strive for economies of scale. Second, demand for health care is often considered recession resistant, with valuations remaining high despite turbulence in the economy. Third, the delivery system has numerous inefficiencies, which attracts private equity firms with a core competency of reducing waste. An aging population and the increasing prevalence of chronic disease also contribute to a growing demand for health care services.

Physicians may be attracted by private equity buyouts for several reasons, including the appeal of large upfront payments from the sale of their practice (often at double-digit multiples of earnings). These up-front payments are attractive because they replace future income but are taxed at capital gains rates, which are significantly lower than income tax rates. New requirements and mounting uncertainty as the health care system moves toward value-based purchasing may have also made physicians more interested in selling their practices. Some physicians may sell because of concern that they can no longer compete for insurance contracts as an independent practice in an increasingly consolidated market. Other motivating factors for physicians to sell include relief of financial pressures from increasing expenses for billing and technology and the opportunity to use an infusion of capital to grow the practice. These factors may outweigh any salary reductions or loss of autonomy from a buyout.

Potential Consequences

Although it may be premature to determine the consequences of increased private equity ownership on the health care system, the incentive structures and tactics of buyout firms raise concerns over the proliferation of private equity in health care. Evidence comparing the quality of private equity firm–owned practices with physician-owned practices is limited, due in part to nondisclosure agreements. However, the need for private equity firms to achieve high returns on investment (often at least 2.5×) on a fast time horizon (approximately 6 years on average) may conflict with the need for investments in quality and safety.2 Additionally, the need for generating returns may create pressure to increase utilization, direct referrals internally to capture revenue from additional services, and rely on care delivered by unsupervised allied clinicians.

A case study in dermatology illustrates the risks of private equity in health care. Dermatologists, despite comprising 1% of physicians in the United States, were involved in approximately 15% of the more than 200 medical-practice acquisitions by private equity in 2015 and 2016.3 Some have expressed concern that private equity ownership may create an emphasis on profitability, which influences patient care.3 In particular, dermatologists reported pressure to meet production numbers for procedures, sell products (eg, acne creams and antiaging products), and refer patients to affiliated specialists, laboratory technicians, and estheticians. Other concerns included upcharging in billing offices and significant reliance on physician assistants in unsupervised settings,3 which raises questions about patient safety and low-value care and highlights the importance of regulatory standards for medically necessary care and appropriate supervision of nonphysician clinicians.

Some specialties may be more susceptible than others. In ophthalmology, experience with private equity ownership and the effects on clinical practice appear to be mixed. While only qualitative evidence is available, some practices acquired by private equity firms report a short-term profit mentality that surpassed the need for long-term planning and equipment and facility requests; whereas others report little change in practice operations or patient care.4 The limited data and variability of anecdotal experience motivate the need for systematic study. The literature on private equity and nursing homes provides a model for research, including comparisons of quality between private equity–owned and independent nursing homes, as well as longitudinal case studies that document the operational changes following private equity buyout.5 One key concern for quality is that keeping referrals within the practice may render referral patterns less responsive to patient needs or preferences.

In light of increasing health care spending nationwide, the potential effects of private equity buyouts on spending deserve further study. Although hospital ownership of physician practices has been associated with higher prices and spending, private equity ownership has yet to be rigorously evaluated. As both hospitals and private equity firms benefit, under a fee-for-service model, from acquisitions that garner higher prices and higher volume (through internalizing referrals and ancillary revenue streams), private equity ownership may have similar effects as hospital or health system ownership of physician practices. However, given that hospitals and academic medical centers, unlike private equity firms, use revenues from some insurers to subsidize care for low-income patients and to fund medical education and research, private equity may have different implications for spending. Even though consolidation may create economies of scale and layoffs and other cost-cutting measures may reduce operating costs, increased market power over price negotiations with insurers and boosting volume for ancillary revenue streams may increase spending. Empirical analysis is needed to understand the net consequences and to compare spending among private equity–owned, hospital-owned, and independent practices.

In addition to quality and costs, there is reason to be concerned about access. After a private equity firm consolidates a fragmented market, it can use its market position to drive smaller independent practices out of business, potentially reducing the availability of physician services in a given geography. Another risk is that when a private equity firm sells recently acquired practices for a profit to new owners, some of those practices may be forced to declare bankruptcy. The struggles of physician practice management companies in the 1990s is an important example of how financially motivated efforts to consolidate practices can lead to physician group bankruptcies.6 Private equity–owned practices may also face pressure from investors to avoid providing low-profit services.

Conclusions

Policy makers have an important role in the changing landscape of private equity and health care. First, because redirection of referrals and internalization of ancillary services are core strategies for boosting financial performance of physician practices, regulators could watch for violations of Stark Law, which prohibits physician self-referral for certain services, and the Antikickback Statute, which prohibits the use of incentives to encourage referrals among private equity–owned groups. Second, generating unnecessary volume and overreliance on allied practitioners without proper supervision may implicate the False Claims Act, which renders it illegal to submit fraudulent claims to Medicare or Medicaid, and possible malpractice. The Department of Justice recently pursued private equity firms that own health care companies in False Claims Act litigation.7 Third, given that private equity firms often consolidate practices in a region, regulators could monitor serial buyouts for anticompetitive consequences. Fourth, greater transparency over private ownership of physician practices may help patients make more informed choices about their care. This may also induce greater attention to quality among private equity owners of practices. These steps might help protect and empower patients, especially those in vulnerable populations.

The increase in private equity investments in health care poses risks, including overutilization, practice instability, and patient safety concerns. However, these investments may also benefit patients and bring more efficiency to a system burdened with waste. More research, and likely thoughtful regulation, are needed to preserve the positive effects of private equity in health care while mitigating the negative ones.

Acknowledgements

Supported by a grant from the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health (NIH Director’s Early Independence Award, 1DP5OD024564-01, to Dr. Song).

Footnotes

Disclosures

Suhas Gondi is an advisor for Where4Care, LLC and 8VC, LLC. He does not receive any financial compensation from either entity.

Zirui Song has no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Murphy K, Jain N Global Healthcare Private Equity and Corporate M&A Report 2018. https://www.bain.com/insights/global-healthcare-private-equity-and-corporate-ma-report-2018/. Accessed February 23, 2019.

- 2.Lewis A PE hold times keep going up. https://pitchbook.com/news/articles/pe-hold-times-keep-going-up. Accessed January 24, 2019.

- 3.Resneck JS Jr. Dermatology practice consolidation fueled by private equity investment. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(1):13–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kent C Is a private equity deal right for you? https://www.reviewofophthalmology.com/article/is-a-private-equity-deal-right-for-you-pt-2. Accessed November 18, 2018.

- 5.Stevenson DG, Grabowski DC Private equity investment and nursing home care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(5):1399–1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reinhardt UE The rise and fall of the physician practice management industry. Health Aff (Millwood). 2000;19(1):42–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andrisani NJ, Sitarchuk EW, Klayman MD DOJ targeting private equity firms in false claims act litigation. https://www2.law.temple.edu/10q/doj-targeting-private-equity-firms-infalse-claims-act-litigation/. Accessed January 19, 2019.