Abstract

Background

Methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) colonization is associated with the development of skin and soft tissue infection in children. While MRSA decolonization protocols are effective in eradicating MRSA colonization, they have not been shown to prevent recurrent MRSA infections. This study analyzed the prescription of decolonization protocols, rates of MRSA abscess recurrence, and factors associated with recurrence.

Materials and Methods

This study is a single institution retrospective review of patients ≤ 18 years of age diagnosed with MRSA culture-positive abscesses who underwent incision and drainage at a tertiary care children’s hospital. The prescription of a MRSA decolonization protocol was recorded. The primary outcome was MRSA abscess recurrence.

Results

Three hundred ninety-nine patients with MRSA culture-positive abscesses who underwent incision and drainage were identified. Patients with prior history of abscesses, prior MRSA infection groin/genital region abscesses, higher number of family members with a history of abscess/cellulitis or MRSA infection and incision and drainage by a pediatric surgeon were more likely to be prescribed decolonization. Decolonized patients did not have lower rates of recurrence. Recurrence was more likely to occur in patients with prior abscesses, prior MRSA infection, family history of abscesses, family history of MRSA infection, Hispanic ethnicity, and those with fever on admission.

Conclusions

MRSA decolonization did not decrease the rate of recurrence of MRSA abscesses in our patient cohort. Patients at high risk for MRSA recurrence such as personal or family history of abscess or MRSA infection, Hispanic ethnicity, or fever on admission did not benefit from decolonization.

Keywords: MRSA, decolonization, staphylococcus, SSTI, abscess, pediatric

Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus is the most common microorganism responsible for skin and soft tissue infections (SSTI) in children and adults1,2. The percentage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strains has increased dramatically since its emergence as a community-acquired pathogen capable of infecting immunocompetent hosts in the 1990’s1–5. SSTIs are estimated to comprise greater than one percent of all pediatric and adult hospital admissions in the United States, and the inflation-adjusted economic burden associated with each admission for SSTI is increasing1,3,6–8. Recurrence of MRSA SSTI is extremely common, ranging from 18% to 43%9–12.

MRSA colonization is a risk factor for both primary and recurrent MRSI SSTIs, with colonization in approximately 76% of infected patients4,13–16. A study by Al-Zubeidi et al. demonstrated that 90% of recurrent MRSA SSTIs were due to identical strain types via repetitive-sequence polymerase chain reaction, lending support that colonization predisposes to recurrent infection17. Additionally, MRSA carriage among household members is very common in patients with MRSA SSTI and may serve as a reservoir for future infections18–20.

Despite this, decolonization efforts have been largely unsuccessful at reducing recurrence of MRSA SSTI17,18,21–25. Various methods have been proposed, such as sodium hypochlorite (bleach) baths, chlorhexidine or hexachlorophene washes, and mupirocin nasal ointments, alone or in combination with oral or IV antibiotics20–27. These decolonization protocols have significantly reduced MRSA colonization in some studies, but MRSA decolonization has not been demonstrated to decrease MRSA SSTI recurrence21,22,25,27. The literature for decolonization in the prevention of surgical site infections after clean surgery is more robust, with multiple specialties demonstrating significant reductions in surgical site infection after decolonization28–32. Therefore, the role of decolonization in SSTIs remains unclear. However, responsible antibiotic stewardship requires scrutiny of all medications that may induce resistance, including the agents used in decolonization protocols28,33–35.

The objective of this study was to evaluate whether MRSA decolonization impacted recurrence of MRSA SSTI after incision and drainage in pediatric patients. Additionally, we sought to identify whether certain patient characteristics are associated with benefit from MRSA decolonization, in order to more effectively target MRSA decolonization to certain populations.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

Patients less than 18 years of age who underwent surgical incision and drainage (I&D) for a skin and soft tissue infection with a positive MRSA culture from January 2007 to December 2017 at a tertiary care children’s hospital were identified. Subjects were queried using CPT codes for incision and drainage (10060–10061), ICD9 codes for SSTIs (680, 681, 682, 685, 686) and MRSA testing (CPT 87081) from the institution’s electronic medical record reporting workbench. Each medical record was examined to only include patients with positive MRSA cultures who underwent I&D. For patients who underwent multiple incision and drainage procedures, the first I&D was considered the index case, and all subsequent SSTIs and/or I&Ds were documented as recurrences. Exclusion criteria included patients who underwent initial I&D in the emergency department, patients without positive MRSA cultures and patients with incomplete or incorrectly coded electronic medical records. Patients undergoing initial I&D in the emergency department were excluded due to inconsistent operative note, decolonization, and follow-up documentation in this setting. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained prior to the initiation of this retrospective chart review (IRB# 2017–1121). No informed consent or waiver of informed consent was obtained for this review.

Data Collection

Clinical parameters collected by chart review included age, gender, race/ethnicity, height, weight, past medical and surgical history, length of stay, fever, white blood count, prior MRSA infections, prior hospitalizations, family history of SSTI, SSTI characteristics, surgeon subspecialty, antibiotic use, and the prescription of a decolonization protocol after surgery and prior to any subsequent recurrences. A patient was classified as decolonized if they were prescribed the decolonization protocol. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, assessment of compliance or adherence to the protocol was not performed. Additionally, patients were classified as having hospital-acquired MRSA if their initial MRSA culture occurred greater than or equal to 48 hours after hospital admission36. Otherwise, patients were classified as having community-acquired MRSA. The decolonization protocol administered is a standardized handout that instructed the patient’s parents to administer mupirocin nasal ointment once daily and to perform sodium hypochlorite baths or chlorhexidine towel washes two to three times per week, for a total of two weeks (Table 1). The protocol specifies that the affected child and all household family members, as well as primary caregivers who do not live in the house, should be decolonized. The primary endpoint was recurrent SSTI. Patient electronic medical records were reviewed by two observers with discussion and agreement on relevant data.

Table 1:

MRSA Decolonization Protocol

|

Who should perform the MRSA Decolonization? |

| The patient |

| Every household member of the family |

| Primary caregivers of the patient who do not live in the household |

|

Mupirocin nasal ointment |

| ALL family members including infants |

| Apply to anterior nares 2-3 times a day for 14 days |

|

Clorox Bleach Baths |

| Any family member over the age of 1 |

| 1-3 years of age |

| ¼ cup Clorox bleach in full tub of water |

| 4 years and older |

| ½ cup of Clorox bleach in a full tub of water |

| Soak in water for 10-15 minutes, neck to feet, then scalp |

| Avoid face; do not get in eyes, nose, or mouth |

| This should be done 2-3 times a week for 2 weeks |

| May substitute bleach baths with chlorhexidine solution or Hibiclens wipes |

Statistical Analysis

Differences in clinical parameters and outcomes were compared for patients with community acquired MRSA versus hospital acquired MRSA, patients who were not decolonized versus those who were decolonized, and patients without MRSA recurrence versus with recurrence. Subgroup analysis was performed on patients with prior abscesses, prior MRSA infections or positive family history to determine the relationship between decolonization and recurrence in these groups. All data were analyzed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, ND). Categorical variables were compared via Fisher’s exact test. Statistical tests were 2-sided, with a p-value of <0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient cohort

Three hundred ninety-nine patients with MRSA culture-positive abscesses undergoing I&D were included in the analysis. Of the patients with MRSA abscesses, 377 (94.5%) were community-acquired infections and 22 (5.5%) were hospital-acquired. 45% of the study population was male and the average age was 3.44 ± 4.4 years old. A majority of the patients were African American (38%) or Hispanic (41%). Fourteen (3.5%) patients were immunocompromised and 14 (3.5%) had a cardiac disorder. Twenty-five percent of patients attended daycare, 21.4% had a prior history of abscess/cellulitis, and 9.5% had a prior history of MRSA.

Patients selected for decolonization

Decolonization protocols were prescribed to 119 (29.8%) of our patient cohort. Patient race was significantly different between decolonized and non-decolonized patients (p=0.04) (Table 2). A subset analysis revealed that African-Americans were less likely to be prescribed decolonization than other races (22.3% vs 34.3%, p=0.012). Risk factors for SSTIs were then assessed (Table 3). Patients with prior history of abscess or cellulitis and prior history of MRSA infection had higher rates of decolonization (16.8% vs 32%, p=0.002; 4.6% vs 17.6%, p=0.0001, respectively). A higher number of family members with a history of abscess/cellulitis or MRSA was associated with a significantly increased likelihood of decolonization prescription (p<0.0001 and p<0.0001, respectively). There was no difference in decolonization rates between patients with community-acquired and hospital-acquired infections (p=0.63).

Table 2:

Demographics

| Variable | Not Prescribed Decolonization | Prescribed Decolonization | p value | No Recurrence | Recurrence | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=280 | n=119 | n=336 | n=62 | |||

| Age (mean ± SD, years) | 3.67 ± 4.72 | 2.90 ± 3.67 | 0.72 | 3.42 ± 4.39 | 3.57 ± 4.79 | 0.72 |

| Gender | 0.91 | 0.07 | ||||

| Male | 124 (44.3%) | 54 (45.4%) | 156 (46.4%) | 21 (33.9%) | ||

| Female | 156 (55.7%) | 65 (54.6%) | 180 (53.6%) | 41 (66.1%) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | 0.04 | 0.04 | ||||

| Caucasian | 42 (15.3%) | 20 (17.2%) | 53 (16.2%) | 9 (14.8%) | ||

| African American | 115 (42.0%) | 33 (28.5%) | 132 (40.3%) | 15 (24.6%) | ||

| Asian | 7 (2.6%) | 1 (0.9%) | 8 (2.4%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Hispanic | 103 (37.6%) | 55 (47.4%) | 125 (38.1%) | 33 (54.1%) | ||

| Other | 7 (2.5%) | 7 (6.0%) | 10 (3.0%) | 4 (6.5%) | ||

| Height (mean ± SD, cm) | 38.14 ±12.99 | 34.45 ± 10.04 | 0.17 | 36.8 ± 12.2 | 39.1 ± 12.94 | 0.70 |

| Weight (mean ± SD, kg) | 20.76 ± 22.96 | 15.23 ± 11.64 | 0.42 | 18.68 ± 18.93 | 21.27 ±26.95 | 0.80 |

Table 3:

Patients selected for decolonization

| Variable | Not Prescribed Decolonization | Prescribed Decolonization | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n=280 (%) | n=119 (%) | ||

|

Risk Factors | |||

| Immunocompromised | 10 (3.6%) | 4 (3.4%) | 0.99 |

| Cardiac Disorder | 12 (4.3%) | 2 (1.7%) | 0.25 |

| Attend Day Care | 58 (20.7%) | 24 (20.2%) | 0.96 |

| Prior Hx of abscess/cellulitis | 47 (16.8%) | 38 (31.9%) | 0.002 |

| Prior Hx of MRSA | 13 (4.6%) | 21 (17.6%) | 0.0001 |

| # of family members with Hx of abscess/cellulitis (mean ± SD) | 0.20 ± 0.55 | 0.47 ± 0.75 | <0.0001 |

| # of family members with Hx MRSA (mean ± SD) | 0.05 ± 0.25 | 0.27 ± 0.63 | <0.0001 |

| Previous hospitalization that year | 37 (6.1%) | 20 (16.8%) | 0.35 |

| Community-acquired MRSA | 263 (94.0%) | 114 (95.8%) | 0.63 |

| Hospital-acquired MRSA | 17 (6.1%) | 5 (4.2%) | |

| Indwelling catheter or device | 1 (0.4%) | 0 | 0.99 |

|

Clinical Factors and Outcomes | |||

| Duration of symptoms prior to presentation (mean ± SD, days) | 4.25 ± 6.34 | 4.73 ± 4.26 | 0.01 |

| Size of abscess (mean ± SD; cm) | 4.35 ± 3.10 | 4.32 ± 2.66 | 0.57 |

| Fever | 117 (41.8%) | 37 (31.1%) | 0.09 |

| Leukocytosis | 139 (81.3%) | 52 (91.2%) | 0.98 |

| Nasal MRSA Screen | 19 (6.8%) | 8 (6.7%) | 0.99 |

| Antibiotics administered | 0.38 | ||

| None | 0 | 1 (0. 8%) | |

| PO antibiotics only | 13 (4.6%) | 3 (2.5%) | |

| IV antibiotics only | 151 (54.1%) | 64 (53.8%) | |

| Both PO and IV antibiotics | 115 (41.2%) | 51 (42.9%) | |

| Length of Stay (mean ± SD, days) | 75.78 ± 79.77 | 53.45 ± 33.09 | 0.01 |

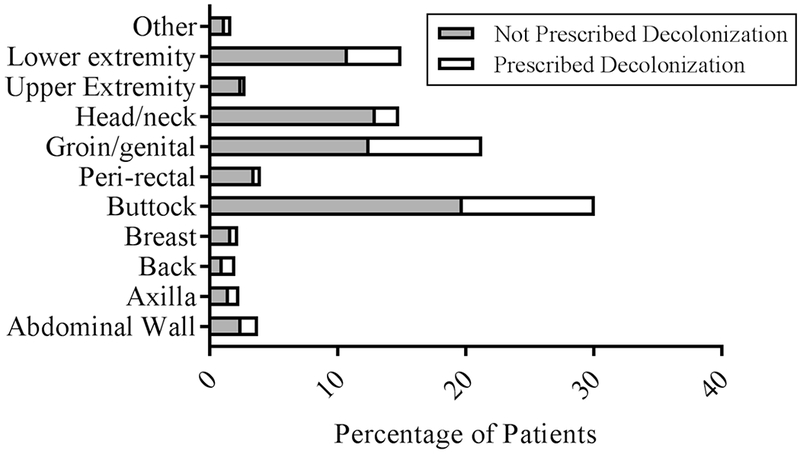

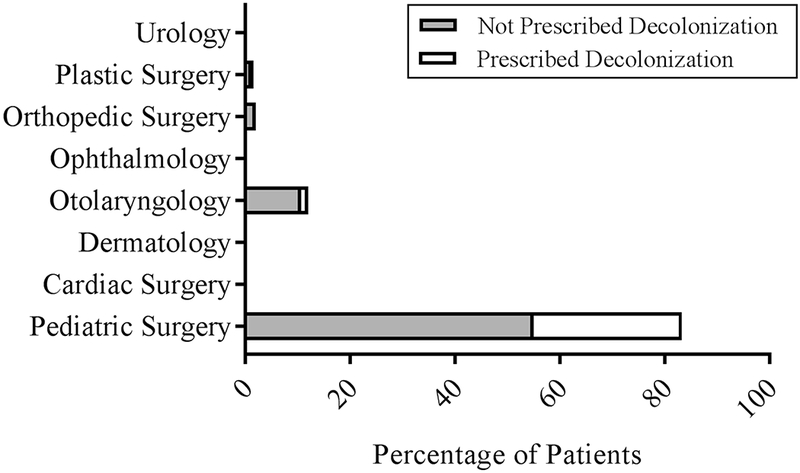

Clinical factors and outcomes were also assessed between the two groups (Table 3). Decolonized patients had a longer duration from onset of symptoms to presentation than non-decolonized patients (p=0.008). The most common site of SSTI involvement was the buttock for both decolonized and non-decolonized patients (Figure 1). A subgroup analysis revealed that patients with groin/genital SSTIs were significantly more likely to undergo decolonization (30% vs 18%, p=0.01), and patients with head and neck SSTIs were significantly less likely to undergo decolonization (11.9% vs 33.1%, p=0.001). Pediatric surgeons performed the I&D for 83.4% of patients (Figure 2). They were significantly more likely to prescribe decolonization compared to other specialties, with 34.0% of their patients prescribed decolonization. Otolaryngologists performed the I&D for 12.0% of patients, making them the second most common I&D surgeons; however, only 10.4% of otolaryngology patients were prescribed decolonization. I&D care was not standardized across providers in terms of drain use, packing, and post-operative antibiotic selection.

Figure 1: Abscess Location.

Percentage of patients prescribed decolonization in different abscess locations.

Figure 2: I&D Provider.

Percentage of patients prescribed decolonization by different provider subspecialties.

Nasal MRSA screens were performed in a minority of patients (7%), and there was no significant difference between decolonized and non-decolonized patients (p=0.99). Antibiotic use was nearly universal (99.7%). Intravenous (IV) antibiotics used alone or in combination with oral (PO) antibiotics accounted for greater than 95% of antibiotic treatments in both groups, with no significant difference between them. Clindamycin was the most commonly used antibiotic. Daycare, size of the abscess, fever on admission, and white blood cell (WBC) count were not significant predictors of decolonization prescription.

MRSA abscess recurrence

Sixty-two of the 398 (15.6%) patients had a recurrence, with an average follow up of 6.35 ± 3.47 years since initial I&D. Of those who had a recurrence, the mean duration from the index I&D to recurrence was 198 days, with a range of 13 to 2,465 days and standard deviation of 327. Twenty-seven (43.5%) patients with recurrence required an additional I&D. Race was significantly associated with recurrence (p=0.04) (Table 2). Subset analysis revealed that Hispanic patients were significantly more likely to recur (20.9% vs. 13.8%, p=0.02) whereas African-American patients were significantly less likely to recur (10.2% vs. 23.5%, p=0.02). Patients with a personal or family history of abscess/cellulitis or MRSA had higher rates of recurrence (Table 4). Fever on admission to the hospital was the only clinical characteristic significantly associated with recurrence (36% vs. 50%, p=0.047). There was no significant difference in recurrence between various locations of the initial abscess or between the subspecialty of surgeon performing incision and drainage.

Table 4:

Patients with recurrence

| Variable | No Recurrence | Recurrence | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n=336 (%) | n=62 (%) | ||

| 0.29 | |||

| Not Prescribed Decolonization | 239 (71.1%) | 40 (64.5%) | |

| Prescribed Decolonization | 97 (28.9%) | 22 (35.5%) | |

|

Risk Factors | |||

| Immunocompromised | 11 (3.3%) | 3 (4.8%) | 0.55 |

| Cardiac Disorder | 3 (4.8%) | 5 (8.0%) | 0.05 |

| Attended Day Care | 68 (20.2%) | 14 (22.6%) | 0.8 |

| Prior Hx of abscess/cellulitis | 61 (18.2%) | 23 (37.1%) | 0.004 |

| Prior Hx of MRSA | 24 (7.1%) | 10 (16.1%) | 0.04 |

| # of family members with Hx of abscess/cellulitis (mean ± SD) | 0.23 ±0.55 | 0.53 ± 0.89 | 0.002 |

| # of family members with Hx MRSA (mean ± SD) | 0.08 ±0.36 | 0.26 ±0.59 | 0.0003 |

| Previous hospitalization that year | 44 (13.1%) | 13 (21.0%) | 0.12 |

| Community-acquired MRSA | 317 (94.3%) | 59 (95.2%) | 0.99 |

| Hospital-acquired MRSA | 19 (5.7%) | 3 (4.8%) | |

| Indwelling catheter or device | 1 (0.3%) | 0 | 0.99 |

|

Clinical Factors and Outcomes | |||

| Duration of symptoms prior to presentation (mean ± SD, days) | 4.42 ± 6.14 | 4.22 ± 3.25 | 0.51 |

| Size of abscess (mean ± SD, cm) | 4.32 ± 2.88 | 4.49 ± 3.40 | 0.97 |

| Fever | 122 (36.2%) | 31 (50.0%) | 0.047 |

| Leukocytosis | 157 (82.2%) | 33 (91.7%) | 0.22 |

| Nasal MRSA Screen | 23 (6.8%) | 4 (6.5%) | 0.99 |

| Antibiotics administered | 0.27 | ||

| None | 1 (0.3%) | 0 | |

| PO antibiotics only | 12 (3.6%) | 4 (6.5%) | |

| IV antibiotics only | 176 (52.5%) | 38 (61.3%) | |

| Both PO and IV antibiotics | 146 (43.6%) | 20 (32.3%) | |

| Length of Stay (mean ± SD, days) | 70.35 ± 73 | 62.6 ± 46 | 0.65 |

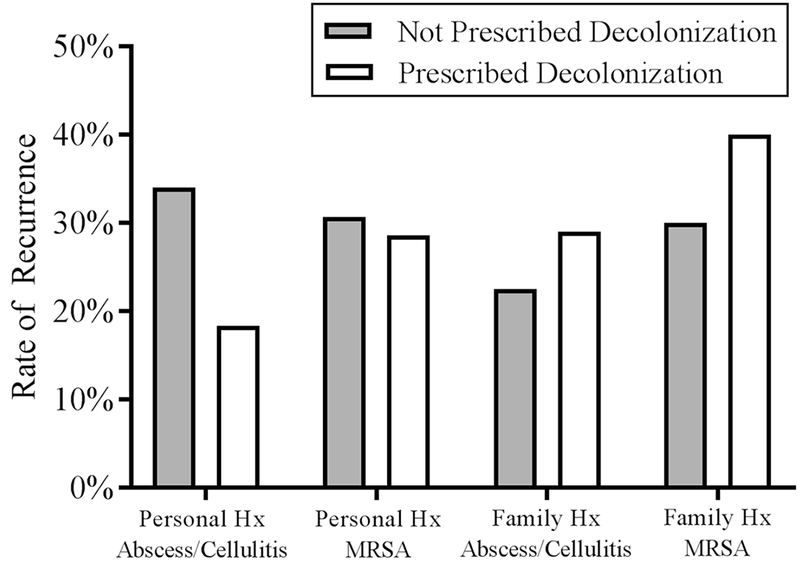

Patients who were prescribed decolonization had a recurrence rate of 18.5%, whereas patients who were not prescribed decolonization had a recurrence rate of 14.3% (p=0.29). A subgroup analysis was performed to determine whether specific patient or clinical characteristics derived benefit from decolonization. Of patients with personal or family history of abscess/cellulitis or MRSA, decolonization did not yield lower rates of recurrence (Figure 3). Additionally, pediatric surgeons were isolated to analyze the association of decolonization with their patients. For patients treated by pediatric surgeons, there was no significant difference in recurrence between decolonized and non-decolonized patients (18.6% vs 15.5%, p=0.466).

Figure 3: Risk Factors for Recurrence: Personal and Family History.

Rate of recurrence for patients with personal or family history of abscess/cellulitis or MRSA. 47 patients with a personal history of abscess/cellulitis were not prescribed decolonization, 16 recurred; 38 patients were prescribed decolonization, 7 recurred; p=0.1. 13 patients with a personal history of MRSA were not prescribed decolonization, 4 recurred; 21 patients were prescribed decolonization, 6 recurred; p=0.89. 40 patients with a family history of abscess/cellulitis were not prescribed decolonization, 9 recurred; 41 were prescribed decolonization, 12 recurred; p=0.49. 10 patients with a family history of MRSA were not prescribed decolonization, 3 recurred; 20 were prescribed decolonization, 8 recurred; p=0.59.

Discussion

MRSA decolonization for SSTI may be prescribed by pediatric surgeons after incision and drainage21. The intention is to reduce MRSA carriage in patients susceptible to recurrent infection. While MRSA decolonization may be an effective means of reducing carriage, it remains unclear whether this translates to decreased SSTI recurrence. Additionally, antibiotic stewardship remains at the forefront of medical practice, and there is concern for the development of microorganisms resistant to antibiotics used in decolonization protocols28,33–35.

MRSA decolonization practices are variable between institutions and subspecialties. Universal decolonization protocols have been documented at several tertiary care centers, especially in the prevention of bloodstream infections in intensive care units and surgical site infection after clean surgery31,32,37,38. The Infectious Diseases Society of America has published recommendations on decolonization for recurrent SSTIs but does not make recommendations for primary MRSA SSTIs39. Regardless, its recommendations are based on Grade C-III evidence39. Our institution does not have guidelines for MRSA decolonization in SSTI and has not developed a universal decolonization protocol. However, a standardized protocol is available for decolonization if the decision is made to prescribe (as described in the methods). Based on a review of the literature, our decolonization protocol is similar in terms of the medications used (topical mupirocin, sodium hypochlorite and/or chlorhexidine) and duration compared to other studies20–25,27,40,41. Additionally, our decolonization protocol is within the recommended protocols for the Infectious Diseases Society of America Clinical Practice guidelines39.

Prior studies have documented the prescribing practices of decolonization protocols at their respective institutions, and prior history of SSTI and household exposures with SSTI are associated commonly associated with decolonization26. Our study similarly found that past history was associated with the prescription of decolonization. Additionally, we found that African-Americans were significantly less likely to be prescribed decolonization. Although the reason for this is not immediately discernable, other literature has shown similar findings with more frequent antibiotics prescription to Caucasian and non-Hispanic races for SSTIs42. Racial disparities in antibiotic prescribing practices for other types of infections are well-documented, and future research should be conducted to determine whether implicit bias may contribute to prescribing practices for decolonization43–45. Decolonization was significantly more likely to be prescribed for groin and genital infections. The reasons for this association are unclear, but we theorize that groin and genital infections may be perceived to have a high likelihood of recurrence and therefore may be prescribed decolonization more commonly. Pediatric surgeons were significantly more likely to prescribe decolonization than other surgeons. We also observed that prescribing practices varied widely between individual pediatric surgeons as well. Some pediatric surgeons prescribed decolonization for many patients and some never prescribed decolonization, perhaps reflecting differences in training or perceptions of the efficacy of decolonization.

Our study identified multiple risk factors for recurrence of MRSA SSTI after incision and drainage. As expected, prior personal or family history of abscess/cellulitis or MRSA infection were associated with recurrence. Interestingly, presence of fever upon admission to the hospital and Hispanic race were significant risk factors for recurrence. While conclusions regarding these findings should be made with caution, Hispanic and febrile patients may serve as targeted risk factors for future study. While African-American patients were less likely to be prescribed decolonization, they were also less likely to recur. A study of HIV-infected patients similarly found that African-American patients with MRSA SSTIs were less likely to recur46. The reasons for this are likely multifactorial. Differences in follow-up at our hospital could contribute to a bias in recurrence rates between races. Furthermore, socioeconomic differences were previously found to explain differences in MRSA rates between races, and may contribute as well47. Despite differences in prescription practices between providers, there was no significant difference in recurrence based on the subspecialty of surgeon performing the I&D.

Similar to many previous studies, we did not identify a significant difference in recurrence between decolonized and non-decolonized children21–25,40. From our review of the literature, only one study demonstrated decreased recurrence after MRSA decolonization20. This randomized trial differed from others in that decolonization was performed on the index patient and all household contacts20. We performed a separate subgroup analysis of patients with significant risk factors for recurrence, in order to identify whether certain patient or clinical characteristics may derive benefit from MRSA decolonization. For patients with prior history of SSTI, MRSA infection, and positive family history of SSTI, decolonization did not significantly impact recurrence.

Several limitations exist in our study. The retrospective nature of our study introduces possible selection bias. The study may not be generalizable to other institutions, as our institution is a tertiary-care referral center in a large metropolitan city, which may have different decolonization practices to other hospitals. Additionally, the mean age of our patients was 3.1 years, limiting the generalizability of the results to older children and teenagers. This is consistent with prior studies of pediatric MRSA SSTIs and may be consistent with the true epidemiology of MRSA SSTIs in children18. However, older children may instead present to adult hospitals for followup for recurrences, and thus our study may underestimate the true incidence of MRSA SSTI recurrence in older pediatric patients. A major limitation is that we used the prescription of the decolonization protocol as a proxy for decolonization. Upon review of the electronic medical records of our patients, minimal documentation was provided on whether or not patients adhered to the protocol. Compliance with bleach baths is likely difficult for entire families. While families have the option of substituting bleach baths for chlorhexidine wipes or towel washes, this is a more expensive option and may not reconcile difficulties with compliance for some families. Therefore, the true number of decolonized patients is likely much less. An additional limitation of the study is that recurrence was only documented if the patient returned to our hospital. Therefore, the recurrence rates of decolonized and non-decolonized patients are likely underestimated, however this is likely to affect both groups similarly. The mean time to recurrence was 198 days, ranging from 13 to 2,465 days, and only 2 of our 62 recurrences occurred within one month after the initial I&D. Therefore, recurrences after the index case are likely to represent genuine recurrences rather than inadequately-drained abscesses. Finally, we were unable to document whether MRSA eradication occurred after decolonization, as very few patients had MRSA nasal screens upon admission. This practice is within recommended guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America, who recommend that MRSA nasal screen should not be performed in all patients undergoing decolonization39. Additionally, prior studies have documented that similar decolonization protocols resulted in effective MRSA clearance27,48. Further studies should be performed with prospective data in order to provide evidence of adherence to the decolonization protocol, to document MRSA carriage before and after decolonization, and to document recurrence at outside institutions.

Conclusions

In summary, MRSA decolonization prescription was not associated with decreased recurrence of MRSA SSTI in pediatric patients, as hypothesized. Additionally, we did not identify subgroups of patients that differentially benefitted from decolonization. We did observe that pediatric surgeons were significantly more likely to prescribe decolonization in our institution but did not have decreased recurrence compared to other providers. A prospective study is necessary to document the relationship between MRSA decolonization and recurrence which can measure adherence and MRSA eradication.

Acknowledgements:

Disclosures: There are no disclosures from the authors. This work was supported by the National Institute of Health Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease Grant (K08DK106450) and the Jay Grosfeld Award from the American Pediatric Surgical Association to C.J.H.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declarations of Interest: None.

References

- 1.Kaplan SL, Hulten KG, Gonzalez BE, et al. Three-year surveillance of community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus infections in children. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(12): 1785–1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ki V, Rotstein C. Bacterial skin and soft tissue infections in adults: A review of their epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment and site of care. Can JInfect Dis Med Microbiol. 2008;19(2):173–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frei CR, Makos BR, Daniels KR, Oramasionwu CU. Emergence of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin and soft tissue infections as a common cause of hospitalization in United States children. JPediatr Surg. 2010;45(10):1967–1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Creech CB, Al-Zubeidi DN, Fritz SA. Prevention of Recurrent Staphylococcal Skin Infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015;29(3):429–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stankovic C, Mahajan PV. Healthy children with invasive community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;22(5):361–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lautz TB, Raval MV, Barsness KA. Increasing national burden of hospitalizations for skin and soft tissue infections in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46(10): 1935–1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hall MJ, DeFrances CJ, Williams SN, Golosinskiy A, Schwartzman A. National Hospital Discharge Survey: 2007 Summary. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; October 26, 2010. 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Witt WP, Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A. Overview of hospital stays for children in the United States. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Web site. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb187-Hospital-Stays-Children-2012.jsp Published 2012 Accessed October 10, 2018.

- 9.Davis SL, Perri MB, Donabedian SM, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45(6): 1705–1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holsenback H, Smith L, Stevenson MD. Cutaneous abscesses in children: epidemiology in the era of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28(7):684–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams DJ, Cooper WO, Kaltenbach LA, et al. Comparative effectiveness of antibiotic treatment strategies for pediatric skin and soft-tissue infections. Pediatrics. 2011;128(3):e479–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sreeramoju P, Porbandarwalla NS, Arango J, et al. Recurrent skin and soft tissue infections due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus requiring operative debridement. Am J Surg. 2011;201(2):216–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wertheim HF, Melles DC, Vos MC, et al. The role of nasal carriage in Staphylococcus aureus infections. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5(12):751–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kluytmans J, van Belkum A, Verbrugh H. Nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus: epidemiology, underlying mechanisms, and associated risks. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997; 10(3):505–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Immergluck LC, Jain S, Ray SM, et al. Risk of Skin and Soft Tissue Infections among Children Found to be Staphylococcus aureus MRSA USA300 Carriers. West J Emerg Med. 2017;18(2):201–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hobbs MR, Grant CC, Thomas MG, et al. Staphylococcus aureus colonisation and its relationship with skin and soft tissue infection in New Zealand children. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2018;37(10):2001–2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Zubeidi D, Burnham CA, Hogan PG, Collins R, Hunstad DA, Fritz SA. Molecular Epidemiology of Recurrent Cutaneous Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Infections in Children. JPediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2014;3(3):261–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fritz SA, Hogan PG, Hayek G, et al. Staphylococcus aureus colonization in children with community-associated Staphylococcus aureus skin infections and their household contacts. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012; 166(6):551–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mollema FP, Richardus JH, Behrendt M, et al. Transmission of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus to household contacts. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48(1):202–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fritz SA, Hogan PG, Hayek G, et al. Household versus individual approaches to eradication of community-associated Staphylococcus aureus in children: a randomized trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(6):743–751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finnell SM, Rosenman MB, Christenson JC, Downs SM. Decolonization of children after incision and drainage for MRSA abscess: a retrospective cohort study. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2015;54(5):445–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weintrob A, Bebu I, Agan B, et al. Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study on Decolonization Procedures for Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) among HIV-Infected Adults. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0128071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaplan SL, Forbes A, Hammerman WA, et al. Randomized trial of “bleach baths” plus routine hygienic measures vs. routine hygienic measures alone for prevention of recurrent infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(5):679–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ellis MW, Griffith ME, Dooley DP, et al. Targeted intranasal mupirocin to prevent colonization and infection by community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains in soldiers: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51(10):3591–3598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cluzet VC, Gerber JS, Nachamkin I, et al. Duration of Colonization and Determinants of Earlier Clearance of Colonization With Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(10): 1489–1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jennings JE, Timm NL, Duma EM. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: decolonization and prevention prescribing practices for children treated with skin abscesses/boils in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2015;31(4):266–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fritz SA, Camins BC, Eisenstein KA, et al. Effectiveness of measures to eradicate Staphylococcus aureus carriage in patients with community-associated skin and soft-tissue infections: a randomized trial. Infect ControlHosp Epidemiol. 2011;32(9):872–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Humphreys H, Becker K, Dohmen PM, et al. Staphylococcus aureus and surgical site infections: benefits of screening and decolonization before surgery. J Hosp Infect. 2016;94(3):295–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schweizer ML, Chiang HY, Septimus E, et al. Association of a bundled intervention with surgical site infections among patients undergoing cardiac, hip, or knee surgery. JAMA. 2015;313(21):2162–2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen AF, Wessel CB, Rao N. Staphylococcus aureus screening and decolonization in orthopaedic surgery and reduction of surgical site infections. Clin Orthop RelatRes. 2013;471(7):2383–2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stambough JB, Nam D, Warren DK, et al. Decreased Hospital Costs and Surgical Site Infection Incidence With a Universal Decolonization Protocol in Primary Total Joint Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(3):728–734 e721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lemaignen A, Armand-Lefevre L, Birgand G, et al. Thirteen-year experience with universal Staphylococcus aureus nasal decolonization prior to cardiac surgery: a quasi-experimental study. J Hosp Infect. 2018;100(3):322–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hayden MK, Lolans K, Haffenreffer K, et al. Chlorhexidine and Mupirocin Susceptibility of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Isolates in the REDUCE-MRSA Trial. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54(11):2735–2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poovelikunnel T, Gethin G, Humphreys H. Mupirocin resistance: clinical implications and potential alternatives for the eradication of MRSA. JAntimicrob Chemother. 2015;70(10):2681–2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Poovelikunnel TT, Budri PE, Shore AC, Coleman DC, Humphreys H, Fitzgerald-Hughes D. Molecular Characterization of Nasal Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Isolates Showing Increasing Prevalence of Mupirocin Resistance and Associated Multidrug Resistance following Attempted Decolonization. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fukunaga BT, Sumida WK, Taira DA, Davis JW, Seto TB. Hospital-Acquired Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia Related to Medicare Antibiotic Prescriptions: A State-Level Analysis. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2016;75(10):303–309. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang SS, Septimus E, Kleinman K, et al. Targeted versus universal decolonization to prevent ICU infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(24):2255–2265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnson AT, Nygaard RM, Cohen EM, Fey RM, Wagner AL. The Impact of a Universal Decolonization Protocol on Hospital-Acquired Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a Burn Population. J Burn Care Res. 2016;37(6):e525–e530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the infectious diseases society of america for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children: executive summary. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(3):285–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ellis MW, Schlett CD, Millar EV, et al. Hygiene strategies to prevent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin and soft tissue infections: a cluster-randomized controlled trial among high-risk military trainees. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(11): 1540–1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller LG, Tan J, Eells SJ, Benitez E, Radner AB. Prospective investigation of nasal mupirocin, hexachlorophene body wash, and systemic antibiotics for prevention of recurrent community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(2): 1084–1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mohareb AM, Dugas AF, Hsieh YH. Changing epidemiology and management of infectious diseases in US EDs. Am JEmergMed. 2016;34(6): 1059–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goyal MK, Johnson TJ, Chamberlain JM, et al. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Antibiotic Use for Viral Illness in Emergency Departments. Pediatrics. 2017;140(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gerber JS, Prasad PA, Localio AR, et al. Racial differences in antibiotic prescribing by primary care pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2013;131(4):677–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hausmann LR, Ibrahim SA, Mehrotra A, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in pneumonia treatment and mortality. Med Care. 2009;47(9): 1009–1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hemmige V, McNulty M, Silverman E, David MZ. Recurrent skin and soft tissue infections in HIV-infected patients during a 5-year period: incidence and risk factors in a retrospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.See I, Wesson P, Gualandi N, et al. Socioeconomic Factors Explain Racial Disparities in Invasive Community-Associated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Disease Rates. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(5):597–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kohler P, Bregenzer-Witteck A, Rettenmund G, Otterbech S, Schlegel M. MRSA decolonization: success rate, risk factors for failure and optimal duration of follow-up. Infection. 2013;41(1):33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]