Abstract

Cell therapy offers great promises in replacing the neurons lost due to neurodegenerative diseases or injuries. However, a key challenge is the cellular source for transplantation which is often limited by donor availability. Direct reprogramming provides an exciting avenue to generate specialized neuron subtypes in vitro, which have the potential to be used for autologous transplantation, as well as generation of patient-specific disease models in the lab for drug discovery and testing gene therapy. Here we present a detailed review on transcription factors that promote direct reprogramming of specific neuronal subtypes with particular focus on glutamatergic, GABAergic, dopaminergic, sensory and retinal neurons. We will discuss the developmental role of master transcriptional regulators and specification factors for neuronal subtypes, and summarize their use in promoting direct reprogramming into different neuronal subtypes. Furthermore, we will discuss up-and-coming technologies that advance the cell reprogramming field, including the use of computational prediction of reprogramming factors, opportunity of cellular reprogramming using small chemicals and microRNA, as well as the exciting potential for applying direct reprogramming in vivo as a novel approach to promote neuro-regeneration within the body. Finally, we will highlight the clinical potential of direct reprogramming and discuss the hurdles that need to be overcome for clinical translation.

Keywords: Cell reprogramming, Neuronal subtypes, Transcription factors, Direct reprogramming, Glutamatergic neurons, GABAergic neurons, Retinal neurons

Core tip: Direct reprogramming represents an innovative technology to generate neurons in the lab, which can be used for cell therapy, drug screening and disease modeling for neurodegenerative diseases. In this review we will discuss the current advance in identifying transcription factors to promote direct reprogramming of specialized neuronal subtypes, including glutamatergic, GABAergic, dopaminergic, sensory and retinal neurons. We will also discuss the hurdles that need to be overcome for clinical translation.

INTRODUCTION

The mammalian nervous system in adults has limited regenerative capacity, thus disease or trauma often cause permanent neuronal damages and have debilitating repercussions[1]. To facilitate regenerative medicine and repair damages in the nervous systems, we must develop robust methods to generate specialized subtypes of neurons efficiently in the laboratory. Cellular reprogramming could be the key to this issue. This is a technique that utilizes transcription factors to convert one cell type into another. This was demonstrated by the early work of Takahashi and Yamanaka who were able to reprogram somatic cells into induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, using Oct-3/4, Sox2, c-Myc, and Klf[2].This seminal work established cellular reprogramming as a major game changer in generation of patient-specific cells in vitro[3] and enabled subsequent development of direct reprogramming, also known as trans-differentiation. A key characteristic of direct reprogramming is that this method bypasses the pluripotency stage and allows the conversion of one cell lineage directly to another, which represents a potentially faster method to generate cells compared to iPS cell generation and subsequent differentiation[4].

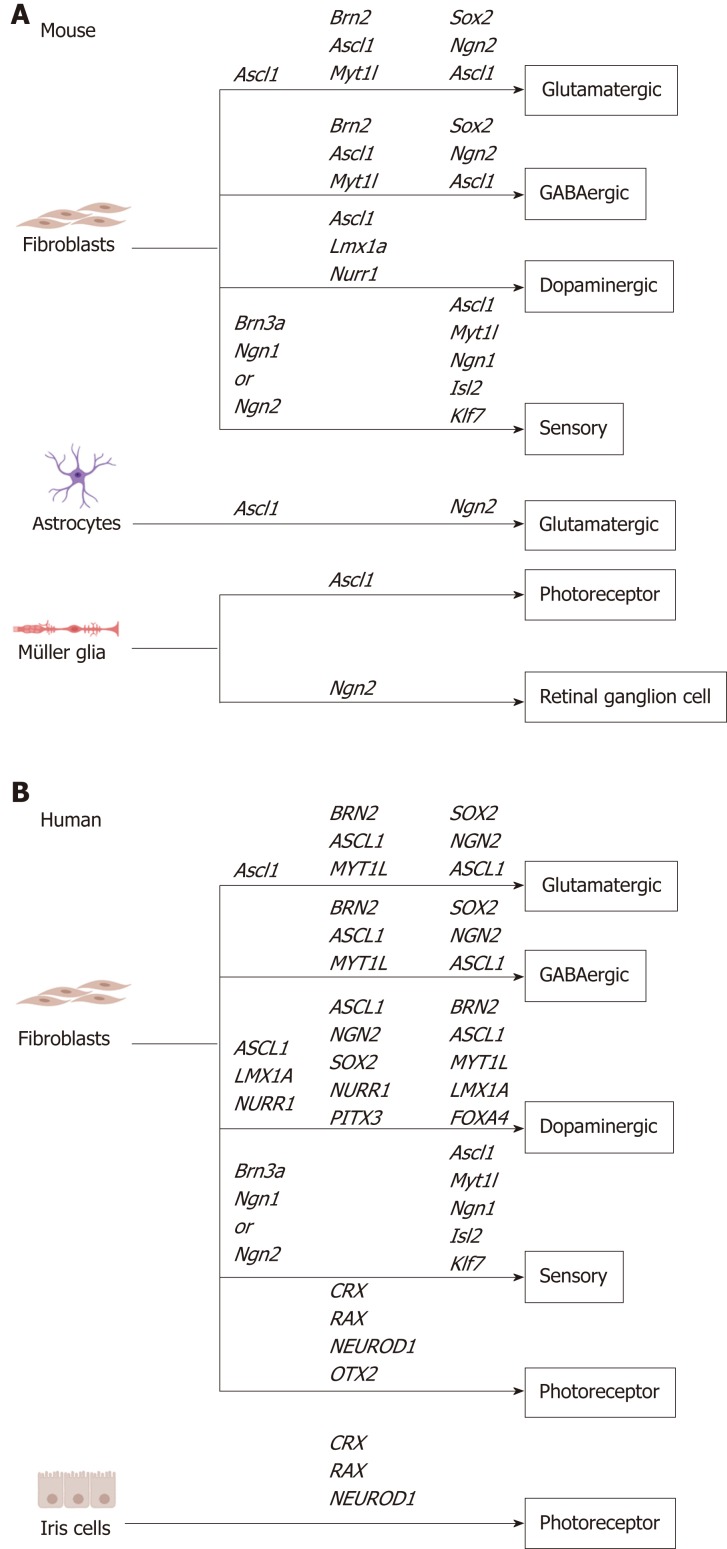

Direct reprogramming allows the rapid generation of patient-derived neurons in vitro, providing a cellular source for transplantation, disease modelling, drug screening and gene therapy[5]. Previous studies have identified transcription factors that promote direct reprogramming of multiple starting cell types into specialized neuronal subtypes (Table 1, Figure 1). Here, we will summarize the role of proneural transcription factors in development and highlight their use in direct reprogramming, with particular focus on their use for specification of neuronal subtypes in vitro.

Table 1.

Summary of in vitro neuronal reprogramming studies discussed in this review with details of transcription factors used and neuronal characteristics

| Species | Cell of origin | Target cell | Transcription factor(s) | Neuronal characteristic | Year and ref. |

| Mouse | Embryonic fibroblast | iN | Ascl1 | Neuronal morphology Neuronal markers Functional electrophysiology | 2014[12] |

| Human | Fetal fibroblast | iN | ASCL1 | Neuronal morphology Neuronal markers | 2014[12] |

| Human | Fibroblast | iN | ASCL1, SOX2 and NGN2 | Neuronal morphology Neuronal markers Neuronal gene expression profile Functional electrophysiology | 2015[14] |

| Mouse | Embryonic fibroblast | iN | Ascl1 | Simple neuronal morphology Neuronal markers | 2010[25] |

| Mouse | Embryonic fibroblast | iN (mostly GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons) | Brn2, Myt1l, Zic1, Olig2, and Ascl1 | Neuronal morphology Neuronal markers Functional electrophysiology Synaptic maturation | 2010[25] |

| Mouse | Embryonic fibroblast | iN (mostly excitatory neurons) | Brn2, Myt1l, and Ascl1 | Neuronal morphology Neuronal markers Functional electrophysiology Synaptic maturation | 2010[25] |

| Mouse | Adult tail tip fibroblast | iN (mostly excitatory neurons) | Brn2, Myt1l, and Ascl1 | Neuronal morphology Neuronal markers Functional electrophysiology Synaptic maturation | 2010[25] |

| Human | Fibroblast | iN (mostly dopaminergic neurons) | BRN2, MYT1, ASCL1, LMX1A and FOXA4 | Neuronal markers Functional electrophysiology | 2011[26] |

| Mouse | Embryonic fibroblast | iN (mostly dopaminergic neurons) | Mash1, Nurr1 and Lmx1a | Neuronal markers Neuronal gene expression profile Neuronal epigenetic reactivation Functional electrophysiology | 2011[33] |

| Human | Adult fibroblast | iN (mostly dopaminergic neurons) | MASH1, NURR1 and LMX1A | Neuronal morphology Neuronal markers Neuronal gene expression profile Functional electrophysiology | 2011[33] |

| Human | Fibroblast | iN (mostly dopaminergic neurons) | ASCL1, NGN2, SOX2, NURR1 and PITX3 | Neuronal morphology Neuronal markers Neuronal gene expression profile Functional electrophysiology | 2012[35] |

| Mouse | Embryonic fibroblast | Induced sensory neurons | Brn3a and Ngn1 or Ngn2 | Neuronal gene expression profile Functional electrophysiology Synaptic maturation | 2015[38] |

| Human | Adult fibroblast | Induced sensory neurons | BRN3A and NGN1 or NGN2 | Neuronal morphology Neuronal markers Neuronal morphology Neuronal markers Functional electrophysiology | 2015[38] |

| Mouse | Embryonic fibroblast | Induced nociceptors | Ascl1, Myt1l, Ngn1, Isl2, and Klf7 | Neuronal morphology Neuronal markers Neuronal gene expression profile Functional electrophysiology Synaptic maturation | 2014[43] |

| Human | Fibroblast | Induced nociceptors | ASCL1, MYT1L, NGN1, ISL2 and KLF7 | Neuronal markers Functional electrophysiology | 2014[43] |

| Human | Iris cells | Photoreceptor- like cells | Crx, Rx and Neurod1 | Neuronal morphology Neuronal markers Neuronal gene expression profile Functional light electrophysiology | 2012[47] |

| Human | Dermal fibroblast | Photoreceptor- like cells | CRX, RAX, NEUROD1 and OTX2 | Neuronal markers Neuronal gene expression profile Functional light electrophysiology | 2014[48] |

| Mouse | Müller glia | iN (mostly retinal glia- like neurons) | Neurog2 | Neuronal morphology Neuronal markers Functional electrophysiology Neuronal gene expression profile | 2018[56] |

| Mouse | Müller glia | iN (mostly retinal neurons) | Ascl1 | Neuronal morphology Neuronal markers Functional electrophysiology Neuronal gene expression profile | 2018[56] |

| Mouse | Cerebellum astroglia | iN (mostly glutamatergic neurons) | Neurog2 | Neuronal morphology Neuronal markers Synaptic maturation Functional electrophysiology | 2017[57] |

| Mouse | Cerebellum astroglia | iN (mostly glutamatergic neurons) | Ascl1 | Neuronal morphology Neuronal markers Synaptic maturation Functional electrophysiology | 2017[57] |

iN: Induced neurons.

Figure 1.

Transcription factor combination used for in vitro direct reprogramming to specific neuron subtypes in mouse and human, including sensory neurons, GABAergic neurons, glutamatergic neurons, dopaminergic neurons, photoreceptors and retinal ganglion cells. A: Mouse; B: Human.

MASTER REGULATORS OF THE NEURONAL LINEAGE

Proneural genes were first discovered in Drosophila by knockout studies to determine genes responsible for development of sensory bristles[6]. A lack of bristles in a scute mutant fly led to the discovery of many proneural genes essential to proper neural development of the fly[7]. Likewise in the early developmental stages of humans, proneural factors promote neurogenesis and differentiation of progenitor cells to become specialised neurons[6]. For instances, basic helix loop helix (bHLH) genes are important regulators for the specification of neuronal cell fate and differentiation of neural cells in the central and peripheral nervous system[8]. Due to their importance in neural development, bHLH genes are often utilized in direct reprogramming to direct cells into the neuronal lineages[9]. bHLH genes can be categorized into two subtypes; specification and differentiation, both of which are important in the reprogramming of a neuronal subtype[8].

Mash1/Ascl1, is a specification bHLH transcription factor found to be expressed in neural precursors of the developing embryo with a transient expression[8,10]. Mash1/Ascl1 double knockout mice die within 24 h of birth and show major defects in the development of neuronal progenitors in olfactory epithelium, as well as lack of generation of sympathetic neurons. Hence, Mash1/Ascl1 plays an important role in the development of neuronal progenitors[11]. In terms of direct reprogramming, Ascl1 alone was shown to have the ability to reprogram mouse fibroblasts into functional induced neurons (iN). These iN exhibited the expression of mature neuronal markers, including Tuj1, NEUN, MAP2 and synapsin, after 21 d of induction. Notably, the iN were predominantly excitatory as they expressed vesicular glutamatergic transporter 1 but not GABAergic transporter[12]. Furthermore, the use of Ascl1 in a combinational approach has shown to increase the directionality of target neuronal subtype and complexity of the maturation. This will be discussed further in the review under specific subtypes of neurons.

Another bHLH specification gene is neurogenin 2 (NGN2), which is found to have a similar expression pattern to ASCL1 in undifferentiated neural crest cells during development. In neuronal reprogramming experiments NGN2 and ASCL1 can bind and interact when used in combination[13] and increase the neuronal conversion efficiency by up to 13.4%[14]. However, other studies have shown that the expression of NGN2 returns to basal level after neuronal conversions have occurred, suggesting that it is involved in the initial neuronal specification but doesn't have a long-term neuronal survival effect following reprogramming[15].

Unlike the specification factors, differentiation factors have a role in the later maturation of neurons. The bHLH differentiation factor NeuroD1 is absent in precursors and is found to increase expression by 50-fold once the neuron has reached terminal differentiation[16]. Its expression is required for both the maturation process as well as the survival of newly generated neurons[17]. NeuroD1 is found to be upstream to Ngn2[18]. These factors show sequential expression which can be attributed to their loci placement. This pattern is commonly seen in transcription factors involved in different stages of the cell cycle. For instance, the specification factors are found upstream to the differentiation factors[19]. In addition, differentiation factors often play a major role in the neuronal reprogramming and maturation processes.

TRANSCRIPTION FACTORS IN SPECIFICATION OF NEURONAL SUBTYPES

Glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons

The in vitro generation of neuronal subtypes provides an invaluable resource for the study of many neuronal diseases. Figure 1 summarized the transcription factor combinations that were used for in vitro direct reprogramming into neuronal subtypes. One such promising effort is in the reprogramming of glutamatergic neurons. Glutamate is the major neurotransmitter of the central nervous system and an imbalance in its production can lead to major neuronal defects[20,21]. Degradation of glutamatergic neurons is linked to disorders such as schizophrenia[22]. On the other hand, overexpression of glutamate can lead to excitotoxicity and glutamatergic cell death, which are associated with Alzheimer's disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis[23,24].

As mentioned previously, ASCL1 alone is capable of reprogramming fibroblasts into excitatory glutamatergic neurons. However, ASCL1 is often used in a com-binatorial transcription factor approach for direct reprogramming to generate neurons, such as the widely used BAM combination (ASCL1, BRN2 and MYT1L) discovered by Vierbuchen et al[25]. In this study, reprogramming using ASCL1 alone resulted in generation of Tuj1-positive neurons. However, the morphological complexity, maturity and action potentials of the cells could be further improved by the addition of BRN2 and MYT1L. BAM were able to reprogram fibroblasts into predominantly a mix of both glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons; while no other major neuronal subtypes were detected in significant numbers[26]. Unlike glutamate, gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) is the major inhibitory neurotransmitter produced by GABAergic neurons[27]. A further study has discovered that BAM expression is only required in the initial stages of the reprogramming process and removing gene expression 3 days after transduction has no effect on the neuronal reprogramming process[26].

The incorporation of BRN2 and MYT1L into neuronal reprogramming is due to their importance in neural development. BRN2 has a role in the mouse hypothalamus enhancing neural differentiation during development, as well as promoting activation of other events which play a role in the maturation and survival of paraventricular nuclei, as well as supraoptic nuclei[28,29]. MYT1L is a gene expressing a zinc finger protein which can be found in early differentiating neurons but is absent from glial cell populations, suggesting a role in early neuronal differentiation[30]. Although these factors are important for the reprogramming of neurons, neither BRN2 or MYT1L alone is sufficient to induce neurons, as they require ASCL1 to initiate the specification process[25].

Dopaminergic neurons

Dopaminergic (DA) neurons are the main source of dopamine production in the mammalian nervous system and its degeneration could lead to devastating neurological disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease. Restoration of DA neurons in Parkinson's disease could provide a treatment for the disease as demonstrated in rat models[31]. In order to achieve this level of cell type specification, incorporation of fate specification factors during the reprogramming process is necessary.

By incorporating the expression of DA specification factors LMX1A and FOXA4 along with BAM factors, approximately 10% of the human iN reprogrammed from human embryonic fibroblasts were DA neurons. Interestingly, the same study found that LMX1A and FOXA4 drove more human iN to a DA fate but did not increase the overall neuronal conversion rate[26]. The differentiation of DA neurons has been shown to be influenced by a positive feedback system in which FOXA1 and FOXA2 promote the expression of LMX1A and LMX1B, which subsequently leads to the development of mesodiencephalic DA neurons[32].

There are also other studies that utilized alternative combination of factors with similar results. Caiazzo et al[33] were able to induce DA neuron reprogramming using fibroblasts with a combination of Ascl1, Nurr1 and Lmx1a. This 3-factor cocktail was able to induce approximately 85% iN that are positive for the DA marker, TH. In this regard, Nurr1 is a DA specific receptor, essential for the formation and survival of DA neurons[34]. It is not activated by ligands but rather forms a heterodimer complex with retinoid X receptor (RXR), and together this complex is able to bind RXR ligands that produce signalling essential for the survival of DA neurons[34].

A subsequent study identified another set of 5 transcription factors which successfully converted human fibroblasts into human-induced DA neurons: ASCL1, NGN2, SOX2, NURR1 and PITX3. Importantly, ASCL1, NGN2 and SOX2 are required for this reprogramming process. On the other hand, exclusion of NURR1 and PITX3 did not have an effect in the early reprogramming process, rather these factors increased the dendrite network and facilitated maturation of DA neurons[35].

Sensory neurons

Diverse subtypes of sensory neurons are responsible for pain and itch perception. Mutations in sensory neuron-specific proteins result in development of a wide range of sensory disorders, like Friedreich’s ataxia[36]. Due to limited availability of human sensory neurons, research in this field is largely dependent on animal models, especially rodents. Therefore, many mechanisms involved in human pain and itch perception remain uncharacterized. Studies from human primary dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons have identified differences between human and mouse nociceptors in function of individual channels, receptors and their response to chemical stimuli[37]. Hence, the development of protocols for the generation of bona-fide human sensory neurons in sufficient numbers is vital for accurate modeling of processes like pain and itch.

A previous study has demonstrated the feasibility of reprogramming fibroblasts into sensory neurons using a combination of Brn3a either with Ngn1 or Ngn2[38]. The cells displayed pseudounipolar morphology, and selectively responded to chemical mimics of pain, temperature, and itch. Both combinations with Ngn1 or Ngn2 equally induced the differentiation into three functional classes of sensory neurons, expressing one of the tropomyosin receptor kinase TrkA, TrkB, or TrkC[38]. Ngn1 and Ngn2 are alternative neurogenic bHLH factors that are expressed within progenitors of the developing DRG[39]. Both factors promote cell cycle exit through the induction of NeuroD1 and NeuroD4, and regulate two waves of neurogenesis[40-42]. Ngn1 and Ngn2 are co-expressed during much part of the early phase of DRG neurogenesis, and are both required for the generation of TrkB+ and TrkC+ sensory neurons. On the other hand, in the later phase Ngn1 is exclusively expressed in neural precursors and is largely responsible for the development of TrkA+ class sensory neurons[39]. At the time of cell cycle exit, the sensory neurons express the “pan-sensory” factors Brn3a and Islet1, which terminate the expression of the bHLH neurogenic factors and initiate the expression of definitive sensory markers to complete neurogenesis[42].

Similarly, functional nociceptor neurons can be generated through the transgenic expression of Ascl1, Myt1l, Ngn1, Isl2, and Klf7 in mouse and human fibroblasts[43]. The resultant iN expressed functional receptors for the noxious compounds menthol (TrpM8), mustard oil (TrpA1) and capsaicin (TrpV1). They also displayed the nociceptor-specific TTX-resistant Nav1.8 sodium channel. Notably, these iN were able to replicate inflammatory and chemotherapy-induced sensitization, which form the basis of pathological pain. Furthermore, this reprogramming method was successful in the generation of patient-derived neurons from familial dysautonomia, thus representing a promising approach for disease modeling[43]. For the five factors employed, Ascl1 and Myt1l are members of the three-factor combination for neuronal lineage reprogramming BAM[25]; Klf7 is a factor involved in TrkA expression maintenance[44]; and Isl2 was selected based on its expression profile in DRG[45]. The extent of Isl2 contribution to the lineage reprogramming remained unknown and further studies are needed to clarify this.

Retinal neurons

Retinal neurons are another promising target for therapeutic in situ reprogramming strategies. The retina is a highly organized structure bearing several major types of neurons, including rod and cone photoreceptors, bipolar, amacrine, horizontal and retinal ganglion cells (RGC)[46]. Rod and cone photoreceptors are responsible for detecting light stimuli and converting it to electrical signals that are later sent to the brain for visual perception. The loss of photoreceptors is a key hallmark of many blinding diseases and currently there are no effective treatments to cure blindness once photoreceptors are lost. Therefore, cellular reprogramming is a powerful technique for developing novel approaches for photoreceptor regeneration.

Akihiro Umezawa’s group used a promising combination of factors (CRX, RAX and NEUROD1) to induce the conversion of both iris cells[47] and fibroblasts into photoreceptor-like cells[48]. These factors induced the expression of photoreceptor-related genes and the reprogrammed cells became positive for the rod marker rhodopsin and the cone marker blue-opsin. Notably, some of the reprogrammed cells were photoresponsive. Interestingly, the authors showed that although OTX2 enhanced the upregulation of retinal genes, it was not essential for the repro-gramming[48]. The same combination of factors was used to reprogram peripheral blood mononuclear cells[49], which facilitate clinical applications of this reprogramming strategy as blood samples are easier to collect from patients than fibroblasts. The generated photoreceptor-like cells expressed blue and red/green opsin, and some of the cells were able to respond to light stimuli. However, the reprogrammed cells expressed low levels of rod marker rhodopsin and some photoreceptor-related genes were not detected, which indicated that additional factors might be required to produce mature and functional photoreceptors[49].

In the developing retina, OTX2 is expressed in progenitors and early precursors that become committed to a photoreceptor fate[50,51]. NEUROD and CRX are factors expressed in developing photoreceptors and their expression is maintained in photoreceptors of mature retina, therefore they are proposed to participate in cell fate specification, as well as in maturation and survival processes[41,51]. Additionally, NEUROD is known to promote neuron specification in retinal progenitors and regulates interneuron differentiation to direct the amacrine cells fate[41]. On the other hand, CRX is downstream of OTX2 activity, it enhances the expression of photoreceptor-specific genes and is important for terminal differentiation into rod and cone photoreceptors[51,52]. RAX is a factor expressed in retinal and hypothalamic progenitor cells and is a key transcription factor for eye development in vertebrates. In the developing retina, it is involved in retinal progenitor proliferation and photoreceptor fate specification[53-55].

RGC are another interesting therapeutic target within the retina. These specialised retinal neurons convey the visual cues to the brain and form the optic nerve[46,51]. Degeneration of RGC is a major hallmark in glaucoma, a major blinding disease affecting the aging population[56]. Thus, in vitro generation of RGC offers an exciting avenue to develop regenerative therapy for this disease.

A study by Guimarães et al[56] demonstrated that RGC can be reprogrammed from postnatal Müller glia through the overexpression of Ngn2. The forced expression of Ngn2 produced a pool of iN which express genes associated with photoreceptors, amacrine cells and RGCs. However, this was only possible with Müller glia from young mice, as P(21) Müller glia cells failed to reprogram into iN. They also showed that the presence of mitogenic factors like EGF or FGF2 during the expansion of Müller glia enhanced the efficiency of the reprogramming. This finding supports the theory that the starting cell types for reprogramming have a strong influence on the neuronal subtypes in the resultant iN. For instance, ASCL1 or NGN2 alone can reprogram astroglia from the cerebellum and neocortex into neuron subtypes in the brain[57]. On the other hand, these factors can drive reprogramming of Müller glia into iN subtypes with retinal neuronal identities[56,58]. Thus, careful consideration should be taken in choosing the starting cell type in reprogramming to generate specialized neuronal subtypes.

NEW TECHNOLOGICAL ADVANCES IN CELLULAR REPROGRAMMING

Recent studies have demonstrated several exciting approaches to further develop the direct reprogramming processes. Here we will highlight and discuss the use of new technological advances in overcoming the hurdles of direct reprogramming as well as the potential of in vivo application of direct reprogramming to promote regeneration.

Computational predictions of transcription factors

Most of the reprogramming studies mentioned above have taken an elimination approach to identify the optimal set of transcription factor(s) required for direct reprogramming, which is a tedious and laborious screening process. Recent advances in computational biology provide an alternative approach to predict the required transcription factor for cellular reprogramming in a faster and more efficient manner. One early example is CellNet, a computational algorithm that analyze, categorize and predict the function of transcription factors[59]. Subsequently, several other programs have been described to predict the transcription factors for cellular reprogramming, including Mogrify[60], BART[61], MAGICACT[62] and CellRouter[63]. Most of these programs work by comparing the quantitative amount of transcription factor in one cell type to another cell type to create a specificity score, which is used to create a ranking in which transcription factor are sorted and categorized depending on the cell type they are most prominent in[59,64]. Another exciting approach to predict transcription factors for cellular reprogramming is by creating computer models of cells. These programs, such as DeepNEU, can be used to create a simulation model of the cell using deep learning and provides a simulation of the events after the introduction of selected transcription factors[65]. Although these advanced algorithmic models are still in their infancy, further development will improve our understanding of the fundamental properties of cells and the molecular interplay of transcription factors that promote cellular reprogramming.

In vivo application of direct reprogramming

The potential to apply direct reprogramming in vivo represents an exciting direction for regenerative medicine. Therapeutic approaches using in vivo reprogramming have the potential to re-purpose local cells into the cells lost following injury or disease, thus providing an alternative regenerative approach to transplantation[66]. This has already been demonstrated for many neuronal subtypes, including glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons[67]. It was shown that overexpression of NeuroD1 is sufficient to convert astrocytes to glutamatergic neurons in rodents in vivo, as characterized by vGlut1 expression and glutamate-mediated synapses. Compared to astrocytes, interestingly the same study found that the NG2 glial cells have a larger repro-gramming capacity into multiple neuronal subtypes, as the presence of both glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons was detected after NeuroD1 overexpression[67].

There has also been an extensive effort to re-purpose local cells for retinal regeneration. Many studies target the Müller glia within the retina for repro-gramming, which are cells responsible for maintaining the integrity and homeostasis of the retina[68]. Interestingly, the Müller glia exhibit some progenitor properties. In the teleost fish and chicken, upon retinal injury the Müller glia can dedifferentiate into multipotent progenitors and give rise to all retinal neural subtypes[69]. This remarkable trait makes Müller glia an excellent candidate for reprogramming studies.

In several elegant studies by Tom Reh’s group, the author has demonstrated successful reprogramming of mouse Müller glia into a range of retinal neurons both ex vivo and in vivo, by the forced expression of the pro-neural factor Ascl1[58,70]. When Ascl1 was overexpressed in retinal explants and in Müller glia dissociated cultures, the cells re-entered the mitotic cell cycle and expressed neural progenitor genes[58]. This reprogramming was accompanied with chromatin remodeling, acquisition of neural morphology and the ability to respond to neurotransmitters[58]. In addition to its role as a pioneer proneural factor for direct reprogramming and retinal development, Ascl1 induction in response to injury is required for retinal regeneration in the fish[71-73]. Conversely, organisms with limited regenerative capacity in the retina do not upregulate Ascl1 following retinal damage[58,74]. Subsequently, in a landmark study the same group extended the application of Ascl1 to reprogram Müller glia into retinal neurons in vivo following retinal injury[70]. Marker analysis showed that the reprogrammed retinal neurons were able to functionally integrate with the existing retinal circuit. Interestingly, this reprogramming approach was less effective in adult mice compared to young mice[75]. The restrictive regenerative capacity of adult mice Müller glia is thought to be caused by reduced epigenetic accessibility of progenitor genes in the cell, as the addition of histone deacetylase tricostatin A is able to overcome this epigenetic hurdle in adult Müller glia[70]. In support of this, epigenetic profiling using ATAC-seq demonstrated that the treatment with trichostatin A favored the accessibility of genes associated with neural development and differentiation, such as Otx2[70]. In this case, Otx2 is known to regulate genes associated with bipolar and amacrine cells. However, it should be noted that most of the reprogrammed retinal neurons are bipolar cells, suggesting that additional factors are required to induce photoreceptors in vivo.

A subsequent study from Bo Chen’s group demonstrated that adult mice Müller glia can be reprogrammed to rod photoreceptors without the necessity of retinal injury[76]. In this study, the authors first stimulated Müller glia proliferation by forced expression of β-catenin, followed by overexpression of Otx2, Crx and Nrl after two weeks. This approach allowed successful generation of rod photoreceptors in vivo that functionally integrate into the retinal and visual cortex circuits. In a remarkable experiment, the authors were able to use this in vivo reprogramming approach to restore light response in a mouse model of photoreceptor degeneration. Collectively, these studies demonstrate the potential of in vivo reprogramming as a novel approach for neural regeneration.

Alternatives to transcription factor-mediated reprogramming

Beside transcription factors, alternative direct reprogramming strategies using small chemicals and microRNAs are also two exciting research directions to improve the usability of the technology. For instance, chemical reprogramming using small chemicals has been shown to induce functional neurons without the need for transcription factor. A cocktail of 7 small molecules (Valproic acid, CHIR99021, Repsox, Forskolin, SP600125, GO6983 and Y-27632) was successful at reprogramming human fibroblasts into neurons with functional electrophysiology representative of glutamatergic and GABAergic cells[77]. Furthermore, the use of a combinational approach of small molecules together with transcription factors can improve direct reprogramming. In a study by Liu et al[15], NGN2 along with small molecules, forskolin and dorsomorphin, directly reprogrammed human fetal lung fibroblasts to cholinergic neurons with functional electrophysiology. In this regard, forskolin is a cAMP activator in the PKA signalling pathway and dorsomorphin acts as a BMP inhibitor in the BMP signalling pathway, both of which are signaling pathways involved in neurogenesis.

Similarly, microRNAs have also been used in combinational approaches with transcription factors to induce neuronal reprogramming. microRNAs are known to play important roles in post transcriptional regulation, neural differentiation, morphological and phenotypic development[78-82]. In a study by Yoo et al[83], miR-9/9* and miR-124 were used in combination with NEUROD1 to convert human fibroblasts into neurons, however these cells would not always demonstrate repetitive action potential, signifying immature neurons. In order to tackle this issue the same group also introduced two other factors, ASCL1 and MYT1L, and in turn were able to induce neurons with higher maturity which demonstrated repetitive action potentials and even the ability to convert adult human fibroblasts into functional neurons. These studies highlighted alternative approaches to transcription factors that promote neuronal reprogramming.

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVES OF IN VITRO NEURONAL REPROGRAMMING AND CHALLENGES FOR CLINICAL APPLICATION

Allogeneic transplantation represents a promising cell therapy approach to replace neurons lost by injury or neurodegenerative disease, such as Parkinson’s disease[84]. However, there are two major challenges related to transplantation: (1) The shortage of donor tissue for transplantation; and (2) Immuno-rejection issues of the grafted tissue. Development of stem cell and cell reprogramming technology to generate patient-specific cells in vitro would be critical to overcome these hurdles. Cell therapies strategy using pluripotent stem cells have been extensively highlighted previously[85-87]. In comparison, notably direct reprogramming bypasses the pluri-potent stem cell state, thus this is potentially a faster and more cost-effective approach to generate neurons in vitro, with less tumorigenic risks compared to pluripotent stem cell strategy. Moreover, there is also the exciting opportunity to combine with gene therapy to correct disease-causing mutation(s) in the cells in vitro, prior to transplantation to patients to treat hereditary neurodegenerative diseases.

To facilitate clinical translation of direct reprogramming technology, it is critical to develop robust reprogramming protocol to generate target cells with high purity and efficiency. Optimization of transcription factors for direct reprogramming, as well as improved method for gene delivery would be key to improving the reprogramming efficiency. Flow cytometry or magnetic-activated cell sorting can be used to enrich the purity of the target cell type prior to transplantation. For clinical applications, cells derived by direct reprogramming should be produced under good manufacturing practices conditions. To ensure the quality of the reprogrammed cells, it is important that the derived cells are extensively characterized for marker expression and functional studies, and screened to ensure the derived cells have a normal karyotype. In the latter case, the use of non-integrative methods for direct reprogramming is desirable, such as Sendai viruses or episomal vectors.

CONCLUSION

In summary, direct reprogramming allows the conversion of one somatic cell type directly to another cell type. The in vitro reprogramming of neurons provides an exciting avenue to generate patient-specific neurons for disease modelling, drug testing and cell therapy for neurodegenerative diseases. Transcription factors responsible for the specialization and differentiation of neuronal cells during development are commonly for direct reprogramming to generate multiple neuronal subtypes. Future studies that optimize the precise combinations of transcription factors for neuronal reprogramming would improve the reprogramming efficiency, expand the neuronal subtypes that can be generated and facilitate the translation of cellular reprogramming to the clinics. Emerging computational algorithms and alternative reprogramming approaches will further improve the technique of direct reprogramming, and future application of direct reprogramming in vivo would provide a novel approach to promote regeneration in the nervous system.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

RW was supported by funding from the Ophthalmic Research Institute of Australia, the University of Melbourne De Brettville Trust, the Kel and Rosie Day Foundation and the Centre for Eye Research Australia. The Centre for Eye Research Australia receives operational infrastructure support from the Victorian Government.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: There is no conflict of interest associated with any of the senior author or other coauthors contributed their efforts in this manuscript.

Peer-review started: February 24, 2019

First decision: June 5, 2019

Article in press: June 27, 2019

Specialty type: Cell and tissue engineering

Country of origin: Australia

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Andrukhov O, Hassan AI, Leanza G, Li SC S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A E-Editor: Ma YJ

Contributor Information

Layal El Wazan, Cellular Reprogramming Unit, Centre for Eye Research Australia, Melbourne 3004, Australia; Department of Surgery, University of Melbourne, Melbourne 3002, Australia.

Daniel Urrutia-Cabrera, Cellular Reprogramming Unit, Centre for Eye Research Australia, Melbourne 3004, Australia; Department of Surgery, University of Melbourne, Melbourne 3002, Australia.

Raymond Ching-Bong Wong, Cellular Reprogramming Unit, Centre for Eye Research Australia, Melbourne 3004, Australia. wongcb@unimelb.edu.au; Department of Surgery, University of Melbourne, Melbourne 3002, Australia; Ophthalmology, Shenzhen Eye Hospital, Shenzhen 518040, Guangdong Province, China.

References

- 1.Björklund A, Lindvall O. Cell replacement therapies for central nervous system disorders. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:537–544. doi: 10.1038/75705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hung SSC, Khan S, Lo CY, Hewitt AW, Wong RCB. Drug discovery using induced pluripotent stem cell models of neurodegenerative and ocular diseases. Pharmacol Ther. 2017;177:32–43. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelaini S, Cochrane A, Margariti A. Direct reprogramming of adult cells: Avoiding the pluripotent state. Stem Cells Cloning. 2014;7:19–29. doi: 10.2147/SCCAA.S38006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fang L, El Wazan L, Tan C, Nguyen T, Hung SSC, Hewitt AW, Wong RCB. Potentials of Cellular Reprogramming as a Novel Strategy for Neuroregeneration. Front Cell Neurosci. 2018;12:460. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2018.00460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bertrand N, Castro DS, Guillemot F. Proneural genes and the specification of neural cell types. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:517–530. doi: 10.1038/nrn874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghysen A, Dambly-Chaudière C. From DNA to form: The achaete-scute complex. Genes Dev. 1988;2:495–501. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.5.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee JE. Basic helix-loop-helix genes in neural development. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1997;7:13–20. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(97)80115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vierbuchen T, Wernig M. Molecular roadblocks for cellular reprogramming. Mol Cell. 2012;47:827–838. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lo LC, Johnson JE, Wuenschell CW, Saito T, Anderson DJ. Mammalian achaete-scute homolog 1 is transiently expressed by spatially restricted subsets of early neuroepithelial and neural crest cells. Genes Dev. 1991;5:1524–1537. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.9.1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guillemot F, Lo LC, Johnson JE, Auerbach A, Anderson DJ, Joyner AL. Mammalian achaete-scute homolog 1 is required for the early development of olfactory and autonomic neurons. Cell. 1993;75:463–476. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90381-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chanda S, Ang CE, Davila J, Pak C, Mall M, Lee QY, Ahlenius H, Jung SW, Südhof TC, Wernig M. Generation of induced neuronal cells by the single reprogramming factor ASCL1. Stem Cell Reports. 2014;3:282–296. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gradwohl G, Fode C, Guillemot F. Restricted expression of a novel murine atonal-related bHLH protein in undifferentiated neural precursors. Dev Biol. 1996;180:227–241. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao P, Zhu T, Lu X, Zhu J, Li L. Neurogenin 2 enhances the generation of patient-specific induced neuronal cells. Brain Res. 2015;1615:51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu ML, Zang T, Zou Y, Chang JC, Gibson JR, Huber KM, Zhang CL. Small molecules enable neurogenin 2 to efficiently convert human fibroblasts into cholinergic neurons. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2183. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boutin C, Hardt O, de Chevigny A, Coré N, Goebbels S, Seidenfaden R, Bosio A, Cremer H. NeuroD1 induces terminal neuronal differentiation in olfactory neurogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:1201–1206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909015107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao Z, Ure K, Ables JL, Lagace DC, Nave KA, Goebbels S, Eisch AJ, Hsieh J. Neurod1 is essential for the survival and maturation of adult-born neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1090–1092. doi: 10.1038/nn.2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma Q, Kintner C, Anderson DJ. Identification of neurogenin, a vertebrate neuronal determination gene. Cell. 1996;87:43–52. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81321-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weintraub H. The MyoD family and myogenesis: Redundancy, networks, and thresholds. Cell. 1993;75:1241–1244. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90610-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fagg GE, Foster AC. Amino acid neurotransmitters and their pathways in the mammalian central nervous system. Neuroscience. 1983;9:701–719. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(83)90263-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fonnum F. Glutamate: A neurotransmitter in mammalian brain. J Neurochem. 1984;42:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1984.tb09689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim JS, Kornhuber HH, Schmid-Burgk W, Holzmüller B. Low cerebrospinal fluid glutamate in schizophrenic patients and a new hypothesis on schizophrenia. Neurosci Lett. 1980;20:379–382. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(80)90178-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greenamyre JT, Maragos WF, Albin RL, Penney JB, Young AB. Glutamate transmission and toxicity in Alzheimer's disease. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 1988;12:421–430. doi: 10.1016/0278-5846(88)90102-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Plaitakis A. Glutamate dysfunction and selective motor neuron degeneration in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A hypothesis. Ann Neurol. 1990;28:3–8. doi: 10.1002/ana.410280103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vierbuchen T, Ostermeier A, Pang ZP, Kokubu Y, Südhof TC, Wernig M. Direct conversion of fibroblasts to functional neurons by defined factors. Nature. 2010;463:1035–1041. doi: 10.1038/nature08797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pfisterer U, Kirkeby A, Torper O, Wood J, Nelander J, Dufour A, Björklund A, Lindvall O, Jakobsson J, Parmar M. Direct conversion of human fibroblasts to dopaminergic neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:10343–10348. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105135108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bettler B, Kaupmann K, Mosbacher J, Gassmann M. Molecular structure and physiological functions of GABA(B) receptors. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:835–867. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00036.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakai S, Kawano H, Yudate T, Nishi M, Kuno J, Nagata A, Jishage K, Hamada H, Fujii H, Kawamura K. The POU domain transcription factor Brn-2 is required for the determination of specific neuronal lineages in the hypothalamus of the mouse. Genes Dev. 1995;9:3109–3121. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.24.3109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schonemann MD, Ryan AK, McEvilly RJ, O'Connell SM, Arias CA, Kalla KA, Li P, Sawchenko PE, Rosenfeld MG. Development and survival of the endocrine hypothalamus and posterior pituitary gland requires the neuronal POU domain factor Brn-2. Genes Dev. 1995;9:3122–3135. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.24.3122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim JG, Armstrong RC, v Agoston D, Robinsky A, Wiese C, Nagle J, Hudson LD. Myelin transcription factor 1 (Myt1) of the oligodendrocyte lineage, along with a closely related CCHC zinc finger, is expressed in developing neurons in the mammalian central nervous system. J Neurosci Res. 1997;50:272–290. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19971015)50:2<272::AID-JNR16>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wernig M, Zhao JP, Pruszak J, Hedlund E, Fu D, Soldner F, Broccoli V, Constantine-Paton M, Isacson O, Jaenisch R. Neurons derived from reprogrammed fibroblasts functionally integrate into the fetal brain and improve symptoms of rats with Parkinson's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:5856–5861. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801677105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin W, Metzakopian E, Mavromatakis YE, Gao N, Balaskas N, Sasaki H, Briscoe J, Whitsett JA, Goulding M, Kaestner KH, Ang SL. Foxa1 and Foxa2 function both upstream of and cooperatively with Lmx1a and Lmx1b in a feedforward loop promoting mesodiencephalic dopaminergic neuron development. Dev Biol. 2009;333:386–396. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Caiazzo M, Dell'Anno MT, Dvoretskova E, Lazarevic D, Taverna S, Leo D, Sotnikova TD, Menegon A, Roncaglia P, Colciago G, Russo G, Carninci P, Pezzoli G, Gainetdinov RR, Gustincich S, Dityatev A, Broccoli V. Direct generation of functional dopaminergic neurons from mouse and human fibroblasts. Nature. 2011;476:224–227. doi: 10.1038/nature10284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perlmann T, Wallén-Mackenzie A. Nurr1, an orphan nuclear receptor with essential functions in developing dopamine cells. Cell Tissue Res. 2004;318:45–52. doi: 10.1007/s00441-004-0974-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu X, Li F, Stubblefield EA, Blanchard B, Richards TL, Larson GA, He Y, Huang Q, Tan AC, Zhang D, Benke TA, Sladek JR, Zahniser NR, Li CY. Direct reprogramming of human fibroblasts into dopaminergic neuron-like cells. Cell Res. 2012;22:321–332. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sghirlanzoni A, Pareyson D, Lauria G. Sensory neuron diseases. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4:349–361. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70096-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davidson S, Copits BA, Zhang J, Page G, Ghetti A, Gereau RW. Human sensory neurons: Membrane properties and sensitization by inflammatory mediators. Pain. 2014;155:1861–1870. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blanchard JW, Eade KT, Szűcs A, Lo Sardo V, Tsunemoto RK, Williams D, Sanna PP, Baldwin KK. Selective conversion of fibroblasts into peripheral sensory neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:25–35. doi: 10.1038/nn.3887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ma Q, Fode C, Guillemot F, Anderson DJ. Neurogenin1 and neurogenin2 control two distinct waves of neurogenesis in developing dorsal root ganglia. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1717–1728. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.13.1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ma Q, Chen Z, del Barco Barrantes I, de la Pompa JL, Anderson DJ. neurogenin1 is essential for the determination of neuronal precursors for proximal cranial sensory ganglia. Neuron. 1998;20:469–482. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80988-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morrow EM, Furukawa T, Lee JE, Cepko CL. NeuroD regulates multiple functions in the developing neural retina in rodent. Development. 1999;126:23–36. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lanier J, Dykes IM, Nissen S, Eng SR, Turner EE. Brn3a regulates the transition from neurogenesis to terminal differentiation and represses non-neural gene expression in the trigeminal ganglion. Dev Dyn. 2009;238:3065–3079. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wainger BJ, Buttermore ED, Oliveira JT, Mellin C, Lee S, Saber WA, Wang AJ, Ichida JK, Chiu IM, Barrett L, Huebner EA, Bilgin C, Tsujimoto N, Brenneis C, Kapur K, Rubin LL, Eggan K, Woolf CJ. Modeling pain in vitro using nociceptor neurons reprogrammed from fibroblasts. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:17–24. doi: 10.1038/nn.3886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lei L, Laub F, Lush M, Romero M, Zhou J, Luikart B, Klesse L, Ramirez F, Parada LF. The zinc finger transcription factor Klf7 is required for TrkA gene expression and development of nociceptive sensory neurons. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1354–1364. doi: 10.1101/gad.1227705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Allen Institute for Brain Science. Allen Spinal Cord Atlas, 2012 [cited 20 January 2019] Available from: https://alleninstitute.org/what-we-do/brain-science/

- 46.Masland RH. The fundamental plan of the retina. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:877–886. doi: 10.1038/nn0901-877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seko Y, Azuma N, Kaneda M, Nakatani K, Miyagawa Y, Noshiro Y, Kurokawa R, Okano H, Umezawa A. Derivation of human differential photoreceptor-like cells from the iris by defined combinations of CRX, RX and NEUROD. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35611. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seko Y, Azuma N, Ishii T, Komuta Y, Miyamoto K, Miyagawa Y, Kaneda M, Umezawa A. Derivation of human differential photoreceptor cells from adult human dermal fibroblasts by defined combinations of CRX, RAX, OTX2 and NEUROD. Genes Cells. 2014;19:198–208. doi: 10.1111/gtc.12127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Komuta Y, Ishii T, Kaneda M, Ueda Y, Miyamoto K, Toyoda M, Umezawa A, Seko Y. In vitro transdifferentiation of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells to photoreceptor-like cells. Biol Open. 2016;5:709–719. doi: 10.1242/bio.016477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nishida A, Furukawa A, Koike C, Tano Y, Aizawa S, Matsuo I, Furukawa T. Otx2 homeobox gene controls retinal photoreceptor cell fate and pineal gland development. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:1255–1263. doi: 10.1038/nn1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Swaroop A, Kim D, Forrest D. Transcriptional regulation of photoreceptor development and homeostasis in the mammalian retina. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:563–576. doi: 10.1038/nrn2880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Furukawa T, Morrow EM, Cepko CL. Crx, a novel otx-like homeobox gene, shows photoreceptor-specific expression and regulates photoreceptor differentiation. Cell. 1997;91:531–541. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80439-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Muranishi Y, Terada K, Furukawa T. An essential role for Rax in retina and neuroendocrine system development. Dev Growth Differ. 2012;54:341–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2012.01337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Furukawa T, Kozak CA, Cepko CL. rax, a novel paired-type homeobox gene, shows expression in the anterior neural fold and developing retina. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:3088–3093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mathers PH, Grinberg A, Mahon KA, Jamrich M. The Rx homeobox gene is essential for vertebrate eye development. Nature. 1997;387:603–607. doi: 10.1038/42475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Guimarães RPM, Landeira BS, Coelho DM, Golbert DCF, Silveira MS, Linden R, de Melo Reis RA, Costa MR. Evidence of Müller Glia Conversion Into Retina Ganglion Cells Using Neurogenin2. Front Cell Neurosci. 2018;12:410. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2018.00410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chouchane M, Melo de Farias AR, Moura DMS, Hilscher MM, Schroeder T, Leão RN, Costa MR. Lineage Reprogramming of Astroglial Cells from Different Origins into Distinct Neuronal Subtypes. Stem Cell Reports. 2017;9:162–176. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pollak J, Wilken MS, Ueki Y, Cox KE, Sullivan JM, Taylor RJ, Levine EM, Reh TA. ASCL1 reprograms mouse Muller glia into neurogenic retinal progenitors. Development. 2013;140:2619–2631. doi: 10.1242/dev.091355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Morris SA, Cahan P, Li H, Zhao AM, San Roman AK, Shivdasani RA, Collins JJ, Daley GQ. Dissecting engineered cell types and enhancing cell fate conversion via CellNet. Cell. 2014;158:889–902. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rackham OJ, Firas J, Fang H, Oates ME, Holmes ML, Knaupp AS FANTOM Consortium, Suzuki H, Nefzger CM, Daub CO, Shin JW, Petretto E, Forrest AR, Hayashizaki Y, Polo JM, Gough J. A predictive computational framework for direct reprogramming between human cell types. Nat Genet. 2016;48:331–335. doi: 10.1038/ng.3487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang Z, Civelek M, Miller CL, Sheffield NC, Guertin MJ, Zang C. BART: A transcription factor prediction tool with query gene sets or epigenomic profiles. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:2867–2869. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Roopra A. MAGICACT: A tool for predicting transcription factors and cofactors driving gene sets using ENCODE data. BioRiv 2018, 492744. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1007800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lummertz da Rocha E, Rowe RG, Lundin V, Malleshaiah M, Jha DK, Rambo CR, Li H, North TE, Collins JJ, Daley GQ. Reconstruction of complex single-cell trajectories using CellRouter. Nat Commun. 2018;9:892. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03214-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.D'Alessio AC, Fan ZP, Wert KJ, Baranov P, Cohen MA, Saini JS, Cohick E, Charniga C, Dadon D, Hannett NM, Young MJ, Temple S, Jaenisch R, Lee TI, Young RA. A Systematic Approach to Identify Candidate Transcription Factors that Control Cell Identity. Stem Cell Reports. 2015;5:763–775. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Danter WR. DeepNEU: cellular reprogramming comes of age - a machine learning platform with application to rare diseases research. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2019;14:13. doi: 10.1186/s13023-018-0983-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nguyen T, Wong RC. Neuroregeneration using in vivo cellular reprogramming. Neural Regen Res. 2017;12:1073–1074. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.211182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Guo Z, Zhang L, Wu Z, Chen Y, Wang F, Chen G. In vivo direct reprogramming of reactive glial cells into functional neurons after brain injury and in an Alzheimer's disease model. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:188–202. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang J, O'Sullivan ML, Mukherjee D, Puñal VM, Farsiu S, Kay JN. Anatomy and spatial organization of Müller glia in mouse retina. J Comp Neurol. 2017;525:1759–1777. doi: 10.1002/cne.24153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lenkowski JR, Raymond PA. Müller glia: Stem cells for generation and regeneration of retinal neurons in teleost fish. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2014;40:94–123. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jorstad NL, Wilken MS, Grimes WN, Wohl SG, VandenBosch LS, Yoshimatsu T, Wong RO, Rieke F, Reh TA. Stimulation of functional neuronal regeneration from Müller glia in adult mice. Nature. 2017;548:103–107. doi: 10.1038/nature23283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fausett BV, Gumerson JD, Goldman D. The proneural basic helix-loop-helix gene ascl1a is required for retina regeneration. J Neurosci. 2008;28:1109–1117. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4853-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ramachandran R, Zhao XF, Goldman D. Insm1a-mediated gene repression is essential for the formation and differentiation of Müller glia-derived progenitors in the injured retina. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:1013–1023. doi: 10.1038/ncb2586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wan J, Ramachandran R, Goldman D. HB-EGF is necessary and sufficient for Müller glia dedifferentiation and retina regeneration. Dev Cell. 2012;22:334–347. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Karl MO, Hayes S, Nelson BR, Tan K, Buckingham B, Reh TA. Stimulation of neural regeneration in the mouse retina. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19508–19513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807453105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ueki Y, Wilken MS, Cox KE, Chipman L, Jorstad N, Sternhagen K, Simic M, Ullom K, Nakafuku M, Reh TA. Transgenic expression of the proneural transcription factor Ascl1 in Müller glia stimulates retinal regeneration in young mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:13717–13722. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1510595112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yao K, Qiu S, Wang YV, Park SJH, Mohns EJ, Mehta B, Liu X, Chang B, Zenisek D, Crair MC, Demb JB, Chen B. Restoration of vision after de novo genesis of rod photoreceptors in mammalian retinas. Nature. 2018;560:484–488. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0425-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hu W, Qiu B, Guan W, Wang Q, Wang M, Li W, Gao L, Shen L, Huang Y, Xie G, Zhao H, Jin Y, Tang B, Yu Y, Zhao J, Pei G. Direct Conversion of Normal and Alzheimer's Disease Human Fibroblasts into Neuronal Cells by Small Molecules. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;17:204–212. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ebert MS, Sharp PA. Roles for microRNAs in conferring robustness to biological processes. Cell. 2012;149:515–524. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.De Pietri Tonelli D, Pulvers JN, Haffner C, Murchison EP, Hannon GJ, Huttner WB. miRNAs are essential for survival and differentiation of newborn neurons but not for expansion of neural progenitors during early neurogenesis in the mouse embryonic neocortex. Development. 2008;135:3911–3921. doi: 10.1242/dev.025080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kawase-Koga Y, Low R, Otaegi G, Pollock A, Deng H, Eisenhaber F, Maurer-Stroh S, Sun T. RNAase-III enzyme Dicer maintains signaling pathways for differentiation and survival in mouse cortical neural stem cells. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:586–594. doi: 10.1242/jcs.059659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kawase-Koga Y, Otaegi G, Sun T. Different timings of Dicer deletion affect neurogenesis and gliogenesis in the developing mouse central nervous system. Dev Dyn. 2009;238:2800–2812. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Babiarz JE, Hsu R, Melton C, Thomas M, Ullian EM, Blelloch R. A role for noncanonical microRNAs in the mammalian brain revealed by phenotypic differences in Dgcr8 versus Dicer1 knockouts and small RNA sequencing. RNA. 2011;17:1489–1501. doi: 10.1261/rna.2442211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yoo AS, Sun AX, Li L, Shcheglovitov A, Portmann T, Li Y, Lee-Messer C, Dolmetsch RE, Tsien RW, Crabtree GR. MicroRNA-mediated conversion of human fibroblasts to neurons. Nature. 2011;476:228–231. doi: 10.1038/nature10323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lindvall O, Brundin P, Widner H, Rehncrona S, Gustavii B, Frackowiak R, Leenders KL, Sawle G, Rothwell JC, Marsden CD. Grafts of fetal dopamine neurons survive and improve motor function in Parkinson's disease. Science. 1990;247:574–577. doi: 10.1126/science.2105529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Thies RS, Murry CE. The advancement of human pluripotent stem cell-derived therapies into the clinic. Development. 2015;142:3077–3084. doi: 10.1242/dev.126482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Trounson A, DeWitt ND. Pluripotent stem cells progressing to the clinic. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016;17:194–200. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Martin U. Therapeutic Application of Pluripotent Stem Cells: Challenges and Risks. Front Med (Lausanne) 2017;4:229. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2017.00229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]