Abstract

Monoclonal antibodies constitute important and useful tools in clinical practice and biotechnology for diagnosing and treating infectious, inflammatory, immunological and neoplastic diseases. This article reviews evidence on the different acute adverse effects of monoclonal antibodies, specifically infusion-related reactions (IRRs), and on the measures that should be taken before and during crises. A literature search using key terms relating to IRRs produced by monoclonal antibodies was undertaken to generate a comprehensive narrative review of the information available. Immunomodulatory monoclonal antibodies may produce IRRs and hypersensitivity-related reactions. Strategies to avoid or minimize the appearance of IRRs depend on the monoclonal antibody and type of patient and reaction (pre-medication, slowing infusion rates, infusion interruption or desensitization, etc.). Considering the great number of available monoclonal antibodies in current practice and those which will soon be authorized, it is mandatory to have clear guidelines that can give support to practitioners and nurses to help them respond quickly and safely to the different IRRs related to the use of these therapeutic drugs.

Keywords: antibodies, monoclonal, drug-related side effects and adverse reactions, nurse practitioners

Introduction

Important recent advances in biomedical science have been associated with the development and clinical application of biological agents based on monoclonal antibodies (mAb).1 These have been used as important tools in clinical practice and biotechnology in diagnosing and treating infectious, inflammatory, immunological and neoplastic diseases, and also for examining the host/pathogen interaction, and for detecting and quantifying diverse molecules.2

Throughout the evolution from murine, chimeric, and humanized to completely human products, there has been a significant reduction in the immunogenic risks associated with mAbs that resemble endogenous human immunoglobulins more closely.3 Their high specificity enables achieving of very accurate targets that can determine various cellular changes. The clinical use of nearly human or completely human mAbs has increased their clinical tolerability.4 However, an inherent risk of generating adverse immune-mediated drug reactions in humans, such as infusion-related reactions (IRRs), cytokine storms, immunosuppression and autoimmunity has constituted a major obstacle for the development of an early clinical investigation of many of these immunomodulatory mAbs.5

In an analysis of FDA MedWatch safety alerts for mAbs therapeutics, Stanulovic et al (2011) showed that premarketing clinical trials can predict more than half of safety concerns.6 This means, however, that a high percentage of the adverse reactions that mAbs may present will be known through post-marketing notifications. Stanulovic et al (2015) expanded this analysis to assess whether predictable alerts are detected sooner than unpredictable alerts. It was demonstrated that placing the focus on such predictable reactions defined as potential risks may play a role in detecting important safety concerns earlier.7

In recent years, regulatory agencies have approved the merchandising of new mAbs, and many more will appear in the very near future. Nursing professionals, who are responsible for drug administration, should be aware of the most important characteristics of this type of therapeutic tools (mechanisms of action, adverse effects, etc.).8 As a rapid response and appropriate management of hypersensitivity reactions (HR) is vital for optimal patient outcomes, nurses dealing with infusion ought to be familiar with the signs and symptoms of the typical infusion reactions seen with monoclonal antibody treatments, as well as the symptoms of more severe HR.9

It is very important that any facility where mAbs are administered has all the required emergency resuscitation equipment and medication, and that rigorously trained staff are readily available. A basic emergency plan should be made, and each nurse must be familiar and at ease with the protocol.10

Although IRRs are the most common adverse effects of the majority of mAbs, these are usually easily manageable.11

This article reviews recent evidence on the different acute adverse effects of mAbs, and more specifically iIRRs, and on the measures that should be taken before and during crises to control them.

Methods

Different key terms relating to IRRs produced by mAbs were employed to undertake a literature search in order to generate a comprehensive narrative review of the information available. Hand-searching was carried out to find relevant papers from the reference lists of included articles. In addition, all the summaries of product characteristics12 of mAbs in which a possible presentation of IRRs is reported have been reviewed.

Results

Infusion-related reactions

IRRs are common adverse drug reactions which happen when monoclonal antibodies are infused. Symptoms are related in time to drug administration and may range from symptomatic discomfort to fatalities.13 Death may occur rapidly; thus, when dealing with severe IRRs, it is essential that risks are understood and early signs and symptoms are recognized quickly. All clinical staff should know about and be well trained in managing acute adverse events.14

IRRs may be defined as “any signs or symptoms experienced by patients during the infusion of pharmacologic or biologic agents or any event occurring on the first day of drug administration.”14 Acute reactions can manifest within 24 hrs from the first administration of the mAbs, but they appear most frequently from 10 mins to 4 hrs after beginning the administration.15 Clinical manifestations of these reactions vary; Table 1 shows the IRRs reported in the technical files of all mAb drugs ordered according to the ATC classification.12,16

Table 1.

IRRs reported in the technical files of all mAb drugs

|

L. ANTINEOPLASTIC AND IMMUNOMODULATING AGENTS L01. ANTINEOPLASTIC AGENTS | ||||

| ATC code | Drug (brand name) | IRRs | Frequency | Prevention/treatment |

|

L01X. OTHER ANTINEOPLASTIC AGENTS L01XC. Monoclonal Antibodies | ||||

| 02 | Rituximab (MabThera®) | Headache, itching, sore throat, Redness, rashes, urticaria, hypertension and fever.* Generalized edema, bronchospasm, wheezing, laryngeal edema, angioneurotic edema, generalized pruritus, anaphylaxis, anaphylactoid reaction.** |

*Very common **Uncommon |

Pre-medication is advised with analgesic/antipyretic and antihistamine drug. Methylprednisolone i.v. may also be useful before the infusion to lower incidence rate and severity of IRRs. Mild or moderate IRRs are solved by reducing infusion speed. |

| 03 | Trastuzumab (Herceptin®) | Chills, fever, dyspnea, hypotension, wheezing, bronchospasm, tachycardia, decreased oxygen saturation, respiratory distress, rash, nausea, vomiting and headache. | Very common | In case of IRR stop or slowdown infusion and monitor the patient until the resolution of all observed symptoms. Symptoms can be treated with analgesic/antipyretic as meperidine or paracetamol, as well as an antihistaminic agent (diphenhydramine) Severe IRRs were satisfactory treated with support measures such as oxygen, beta-agonists and corticoids. |

| 05 | Gemtuzumab (Mylotarg®) | Fever, chills, hypotension, tachycardia and respiratory symptoms. | Common | Perform perfusion under close clinical supervision, including control of pulse, blood pressure and temperature. Pre-medication with a corticosteroid, antihistamine and paracetamol is recommended 1 hr before administration. |

| 06 | Cetuximab (Erbitux®) | Bronchospasm, urticaria, increased or decreased blood pressure, loss of consciousness or shock. | Very common (mild and moderate) Common (severe) |

In case of severe IRRs, it is mandatory to stop infusion and possibly withdraw permanently. Emergency treatment or measures may be needed. The first dose must be slowly infused and speed must not be >5 mg/min while vital signs are monitored for at least 2 hrs. If any reaction related with the infusion is observed during the first 15 mins of the first administration, the infusion must be stopped. |

| 07 | Bevacizumab (Avastin®) | Dyspnea/shortness of breath, flushing/redness/rash, hypotension o hypertension, oxygen desaturation, chest pain, shivering and nausea/vomiting. | Common | If any reaction related with the infusion is observed, the infusion must be stopped and suitable medical treatment and support immediately administered. Pre-medication is not systematically considered as necessary. |

| 08 | Panitumumab (Vectibix®) | Shivering, fever or dyspnea. | Uncommon | In case of severe IRRs, or a life-threatening reaction, it is mandatory to stop infusion and possibly withdraw permanently. In mild or moderate IRRs it is advisable to slowdown infusion. |

| 11 | Ipilimumab (Yervoy®) | Is not specified. | Common | In case of mild or moderate IRRs patients can receive ipilimumab in combination with nivolumab with close monitoring and pre-medication according to local prophylactic treatment guidelines. In case of severe IRR the infusion of ipilimumab or ipilimumab in combination with nivolumab should be discontinued and appropriate medical treatment should be administered. |

| 12 | Brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris®) | Rash, shortness of breath, breathless sensation, chest tightness, fever and back pain. | Very common | If an IRR occurs, the infusion should be discontinued and appropriate medical treatment instituted. The infusion can be restarted at a slower rate after resolution of symptoms. Patients who have undergone a previous IRR should be pre-medicated before the following infusions (paracetamol, antihistamine and corticosteroid). |

| 13 | Pertuzumab (Perjeta®) | Fever, shivering, tiredness, headache, asthenia, hypersensibility and vomiting. | Very common | If an IRR occurs, the infusion should be discontinued and appropriate medical treatment instituted. Treatment with oxygen, beta-agonists, antihistamines, iv. fluids and antipyretics can help to relieve symptoms. |

| 14 | Trastuzumab emtansine (Kadcyla®) | Flushing, chills, pyrexia, dyspnea, hypotension, wheezing, bronchospasm and tachycardia. | Common | If an IRR occurs, the infusion should be discontinued and appropriate medical treatment instituted. The treatment must be stopped and withdrawn in case of severe IRRs. |

| 15 | Obinutuzumab (Gazyvaro®) | Nausea, shivering, hypotension, pyrexia, vomiting, dyspnea, redness, hypertension, headache, tachycardia and diarrhea, bronchospasm, laryngeal irritation, wheezing, laryngeal edema and auricular fibrillation. | Very common | Stop antihypertensive treatment 12 hrs before each infusion. In the case of Grade 4 IRRs, the infusion should be stopped and treatment discontinued permanently. In the case of Grade 3 IRRs, the infusion should be temporarily discontinued and appropriate medication given to treat the symptoms. In the case of Grades 1 and 2 IRR, the infusion rate should be reduced and the symptoms treated appropriately. |

| 16 | Dinutuximab (Qarziba®) | Fever, hypotension, urticaria, bronchospasm. | Very common (hypersensitivity and CRS) Common (anaphylaxis) |

Pre-medication with antihistaminic iv should be administered (eg diphenhydramine) approximately 20 mins before the start of each infusion. It is recommended to repeat the administration of antihistamine medication every 4–6 hrs as needed during perfusion. |

| 17 | Nivolumab (Opdivo®) | Is not specified. | Common | In case of mild or moderate IRRs can receive nivolumab or nivolumab in combination with ipilimumab with close monitoring and pre-medication according to local prophylactic treatment guidelines. In case of severe IRRs, nivolumab or nivolumab in combination with ipilimumab should be discontinued and appropriate medical treatment should be administered. |

| 18 | Pembrolizumab (Keytruda®) | Hypersensitivity, anaphylactic shock, and CRS. | Common | In case of mild or moderate IRR, patients can continue to receive pembrolizumab with close monitoring; you can assess the previous medication with antipyretics and antihistamines. In severe infusion reactions, the infusion should be stopped and pembrolizumab should be permanently discontinued. |

| 19 | Blinatumomab (Blincyto®) | Pyrexia, CRS, hypotension, myalgia, acute kidney injury, hypertension, and erythematous rash. Infusion reactions may be clinically indistinguishable from the manifestations of CRS. | Very common | The use of antipyretics (eg, paracetamol) is recommended to help in reducing pyrexia during the first 48 hrs of each cycle. |

| 21 | Ramucirumab (Cyramza®) | Tremors, spasms/back pain, pain and/or chest tightness, chills, flushing, dyspnea, wheezing, hypoxia and paresthesias, bronchospasm, supraventricular tachycardia and hypotension. | Is not specified | The administration of a histamine H1 antagonist (eg diphenhydramine) is recommended as a pre-infusion medication. If a patient presents IRRs of Grade 1 or 2, he/she must receive previous histamine/antipyretic medication in all subsequent infusions. Dexamethasone (or equivalent) should be administered if a patient has a second IRR of Grade 1 or 2. For the following infusions, previously administer a histamine H1 antagonist iv (diphenhydramine), paracetamol and dexamethasone. |

| 22 | Necitumumab (Portrazza®) | Chills, fever or dyspnea. | Common | In case of previous hypersensitivity or IRR of Grade 1 or 2, pre-medication with a corticosteroid and an antipyretic is recommended in addition to an antihistamine. |

| 23 | Elotuzumab (Empliciti®) | Fever, chills and hypertension. | Common | Pre-medication should be administered 45–90 mins before perfusion: Dexamethasone 8 mg iv, diphenhydramine (25–50 mg vo or iv) or equivalent, ranitidine (50 mg iv or 150 mg vo) or equivalent, paracetamol (650–1000 mg vo). |

| 24 | Daratumumab (Darzalex®) | Nasal congestion, cough, chills, throat irritation, vomiting, nausea, bronchospasm, dyspnea, laryngeal edema, pulmonary edema, hypoxia, and hypertension. | Very common | Pre-medication with antihistamine, antipyretics and corticosteroids should be administered to reduce the risk of IRR before treatment. The perfusion should be discontinued at any IRR of any intensity and medical/supportive treatment should be instituted as appropriate. In patients with IRR of Grade 1, 2 or 3, when the perfusion is resumed, the perfusion rate should be reduced. |

| 26 | Inotuzumab ozogamicin (Besponsa®) | Hypotension, hot flashes or respiratory problems. | Very common | Depending on the severity of the IRR, consider the interruption of the perfusion or the administration of steroids and antihistamines. In case of serious or life-threatening reactions due to perfusion, stop treatment permanently. |

| 27 | Olaratumab (Lartruvo®) | Chills, fever or dyspnea. | Very common | Pre-medication with antihistamine (eg diphenhydramine) and dexamethasone iv should be administered 30–60 mins before perfusion. |

|

L04. IMMUNOSUPPRESSANTS L04A. IMMUNOSUPPRESSANTS L04AA. Selective immunosuppressants | ||||

| 23 | Natalizumab (Tysabri®) | Dizziness, nausea, urticaria and tremors. | Very common (urticaria) Uncommon (hypersensitivity) |

No measures are specified. |

| 25 | Eculizumab (Soliris®) | Is not specified. | Uncommon | In all cases of patients with severe IRR, the administration of eculizumab should be stopped, and appropriate medical treatment should be instituted. |

| 26 | Belimumab (Benlysta®) | Bradycardia, myalgia, headache, rash, urticaria, pyrexia, hypotension, hypertension, dizziness, and arthralgia. | Common | If an IRR occurs, the infusion should be discontinued and appropriate medical treatment instituted. Pre-medication can be administered (antihistamine with or without an antipyretic). Sufficient data is not available at the moment to establish whether pre-medication can reduce frequency or minimize the severity of IRRs. |

| 33 | Vedolizumab (Entyvio®) | Dyspnea, bronchospasm, urticaria, redness, rash, hypertension and tachycardia. | Uncommon | In the event of severe IRR or anaphylactic reaction discontinue administration immediately and initiate appropriate treatment (epinephrine and antihistamines). In case of mild to moderate IRR, the infusion may be interrupted or slowed down, and appropriate treatment initiated. Consider pretreatment (antihistamines, hydrocortisone and/or paracetamol) before the next infusion in the case of patients with a history of mild to moderate IRR. |

| 34 | Alemtuzumb (Lemtrada®) | Headache, rash, pyrexia, nausea, urticaria, pruritus, insomnia, shivering, redness, tiredness, dyspnea, dysgeusia, chest discomfort, hives, tachycardia, dyspepsia, dizziness and pain. | Common | Patients should be pre treated with corticosteroids immediately prior to administration. In addition, pre treatment with antihistamines and/or antipyretics may be considered. If an IRR occurs, provide symptomatic treatment. In case of severe infusion reactions, immediate discontinuation of infusion should be considered. |

| 36 | Ocrelizumab (Ocrevus®) | Itching, rash, urticaria, erythema, throat irritation, oropharyngeal pain, dyspnea, pharyngeal or laryngeal edema, redness, hypotension, pyrexia, fatigue, headache, dizziness, nausea and tachycardia. | Very common | Pre-medication with 100 mg of methylprednisolone iv (or equivalent) approximately 30 mins before each perfusion and antihistamine approximately 30–60 mins before each infusion. The administration of an antipyretic (eg, paracetamol) may be considered approximately 30–60 mins before each infusion. If during the infusion there are signs of a potentially fatal or incapacitating IRR, the infusion should be discontinued immediately and definitively and the patient given the appropriate treatment. In mild or moderate IRR reduce the rate of infusion. |

| L04AB Inhibitors of tumor necrosis factor alpha (anti-TNF-α) | ||||

| 02 | Infliximab (Inflectra®) | Anaphylactic shock and hypersensibility delayed reactions. Evanescent macular rash that disappears within minutes or hours, chest tightness, dizziness or shortness of breath, headache, hypotension, hypertension, nausea, sweating, and hyperthermia. |

Very common | If acute reactions occur, the infusion should be stopped immediately. Patients can be previously treated with, for example, an antihistamine, hydrocortisone and/or acetaminophen to prevent mild and temporary effects. |

| L04AC Inhibitors of the interleukins | ||||

| 05 | Ustekinumab (Stelara®) | Exanthemas, urticaria. | Uncommon (urticaria) Rare (anaphylaxis, angioedema) |

Is not specified |

| 07 | Tocilizumab (RoActemra®) | Hypertension, headache, nausea and hypotension. | Common | If an anaphylactic reaction or another severe hypersensitivity/severe reaction related to the perfusion occurs, treatment should be stopped immediately and definitively discontinued. |

| 11 | Siltuximab (Sylvant®) | Symptoms of IRRs are not specified in the technical file. | Common (anaphylaxis) | Mild to moderate infusion reactions may improve if the infusion rate is reduced or the infusion is discontinued. Once the reaction has subsided, the resumption of perfusion at a lower rate and the therapeutic administration of antihistamines, acetaminophen and corticosteroids may be considered. It should be discontinued in patients with severe infusion-related hypersensitivity reactions (eg, anaphylaxis) |

Notes: Classification of the frequency of the adverse reactions as per the Guidelines for preparing core clinical-safety information on drugs second edition – report of CIOMS working groups III and V.38 Very common ≥1/10 (≥10%), common (frequent) ≥1/100 and <1/10 (≥1% and <10%), uncommon (infrequent) 1/1000 and ≤1/100 (≥0.1% and <1%), rare ≥1/10,000 and <1/1000 (≥0.01% and <0.1%), and very rare ≤1/10,000 (<0.01%). This table has been made according to the technical specifications of the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Health Products, as per Cima (aemps).12

Abbreviations: mAbs, Monoclonal Antibodies; ATC, Anatomic-Therapeutic-Chemical Classification; IRR, Infusion-related reaction; CRS, Cytokine-release syndrome.

Immunomodulatory mAbs may also result in different HR that include IRRs, cytokine-release reactions, type I (IgE/non-IgE), type III and delayed type IV reactions.17 The symptoms of all types of immunologically mediated infusion reactions overlap, making it difficult to pinpoint the cause without additional laboratory work.5,14

Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters for drug allergy defined anaphylaxis as “an immediate systemic reaction that occurs when a previously sensitized individual is re-exposed to an allergen.”18 The characteristics of true anaphylactic reactions (type I IgE-mediated HR) are dyspnea and tightness of the chest, suffocation, hypotension, bronchospasm, and urticaria; in the absence of either of the latter two symptoms, it is unlikely that an acute reaction is anaphylactic, and it should thus be considered non-allergic.19,20 Since the first exposure to antigen is required for IgE sensitization, type I HR do not occur during the first administration of a mAbs infusion,21 except in rare cases where patients have pre-existing antibodies which cross-react with the drug.5,22

Non-IgE reactions are “immediate systemic reactions that mimic anaphylaxis but are caused by non-IgE-mediated release of mediators from mast cells and basophils.”18 These reactions can occur at the first exposure to an antigen and may be clinically indistinguishable from anaphylaxis. Unlike anaphylactic reactions, non-IgE reactions become milder upon repeated administration. However, there does not appear to be consensus as to whether non-IgE reaction is a separate entity from anaphylaxis.13

Complement activation-related pseudoallergy (CARPA)

CARPA is linked to adverse events evoked by several liposomal and micellar formulations, nanoparticles, radiocontrast agents, and therapeutic antibodies.23 It has been reported as:

a HR, the symptoms of which fit into the Coombs and Gell’s Type I category, which is not initiated or mediated by pre-existing IgE antibodies but arises as a consequence of activation of the complement system.24

MAbs activate the classical complement pathway by binding to the target antigen, allowing the binding of C1q, the recognition molecule of the activation initiator C1 complex, to the Fc part of the antibodies. MAb may provoke this feature and can be manipulated to enhance the effectiveness for avoiding certain adverse effects.25 CARPA typically appears within minutes after the start of the infusion. However, a delay is possible, particularly in pre-medicated patients. Almost all organs can be affected, the most often observed symptoms being flushing, rash, dyspnea, chest pain, back pain and subjective distress.13 All currently available mAbs can be considered to be potentially immunogenic, as their molecular size is large enough and their structure is different from endogenous proteins.25

Cytokine-release syndrome (CRS) is “a potentially life-threatening systemic inflammatory reaction which is observed after the infusion of agents targeting different immune effectors.”26 CRS can manifest itself with a variety of symptoms that range from mild, flu-like symptoms to severe life-threatening occurrences of the overshooting inflammatory response. Starting out with fever and unspecific symptoms, CRS might impact the majority of organ systems (Grades III–IV cases shows signs of life-threatening cardiovascular, pulmonary, renal involvement or neurotoxicity).27 Because events manifest during or after the first exposure to a “new” drug, a differentiation from anaphylaxis may be difficult. There are few allergy-specific symptoms such as urticaria or glottis edema which could guide an allergic diagnosis here.26 In order to get a differential diagnosis, it could be of help to obtain several samples of serum to know the plasmatic level of tryptase (tryptase test), it has to be done at 30 mins of the event, at 2 hrs and at 24 hrs. If this test results positive, it can indicate the activation of mastocytes, and in case of negative, it could be compatible with a CRS or tumoral lysis.28

Health care practitioners must differentiate between the terms “infusion reaction” and “anaphylaxis” and give a clear definition of which symptoms are to be labeled as “infusion-related reaction.” “Infusion reactions” usually represent symptoms that occur within a close time-related relationship to an infusion and are not necessarily linked to anaphylaxis or even hypersensitivity.13 In any case, it may be difficult to differentiate between various types of reactions at the onset of symptoms. Anaphylactic reactions occur within the first few minutes of the infusion, so documenting the time of the onset of symptoms is highly important.10

The latest version of Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events by The US Department of Health and Human Services of the National Cancer Institute (National Institute of Health) depicts a differentiation of all these concepts, using a grading scale of adverse events (Table 2).29

Table 2.

Extracts from the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v5.0 (CTCAE)

| Adverse event | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Infusion-related reaction A disorder characterized by adverse reaction to the infusion of pharmacological or biological substances. |

Mild transient reaction; infusion interruption not indicated; intervention not indicated | Therapy or infusion interruption indicated but responds promptly to symptomatic treatment (for example, antihistamines, NSAIDs, narcotics, IV fluids); prophylactic medications indicated for ≤24 hrs | Prolonged (eg, not rapidly responsive to symptomatic medication and/or brief interruption of infusion); recurrence of symptoms following initial improvement; hospitalization indicated for clinical sequelae | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

|

Anaphylaxis A disorder characterized by an acute inflammatory reaction resulting from the release of histamine and histamine-like substances from mast cells, causing a hypersensitivity immune response. Clinically, it presents with breathing difficulty, dizziness, hypotension, cyanosis and loss of consciousness and may lead to death. |

– | – | Symptomatic bronchospasm, with or without urticaria; parenteral intervention indicated; allergy related edema/angio-edema; hypotension | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

|

Allergic reaction A disorder characterized by an adverse local or general response from exposure to an allergen. If related to infusion, use Injury, poisoning and procedural complications: Infusion-related reaction. Do not report both. |

Systemic intervention not indicated | Oral intervention indicated | Bronchospasm; hospitalization indicated for clinical sequelae; intravenous intervention indicated | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

|

Cytokine-release syndrome A disorder characterized by fever, tachypnea, headache, tachycardia, hypotension, rash, and/or hypoxia caused by the release of cytokines. Also consider reporting other organ dysfunctions including neurological toxicities such as: Psychiatric disorders: Hallucinations or Confusion; Nervous system disorders: Seizure, Dysphasia, Tremor, or Headache |

Fever with or without constitutional symptoms | Hypotension responding to fluids; hypoxia responding to <40% O2 | Hypotension managed with one pressor; hypoxia requiring ≥40% O2 | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

Notes: Adapted from: Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v5.0. US Department of Health and Human Services; National Institutes of Health; National Cancer Institute; 2017. Available from: https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/CTCAE_v5_Quick_Reference_8.5x11.pdf.29

Abbreviations: ALS, advanced life support; CARPA, complement activation-related; CRS, cytokine-release syndrome; CTCAE, common terminology criteria for adverse events; IRR, infusion-related reaction; mAbs, monoclonal antibodies; ATC, anatomic-therapeutic-chemical classification; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Due to the fact that current reporting practices are predominantly based on clinical presentation, researchers, health care professionals and pharmaceutical companies are not employing consistent terminology for reporting IRRs, which leads to under-reporting or over-reporting of allergic reactions, in particular, anaphylaxis.13 Terminology differs between package inserts (eg, allergic reactions, hypersensitivity and infusion reaction) which is a real obstacle. The grading criteria used to measure the severity of the reaction are often unclear. Inserts are vague concerning the exact timing of the reaction. Defining terminology is essential. Similar impediments often seen in clinical practice and medical literature include variations in terminology, inadequate documentation about time of onset of the reaction, inconsistency in grading, lack of documentation on when the reaction occurred, record of pre-medications (if any), and inadequate citation of management actions and effectiveness.10

Infusion-related reactions: prevention and treatment

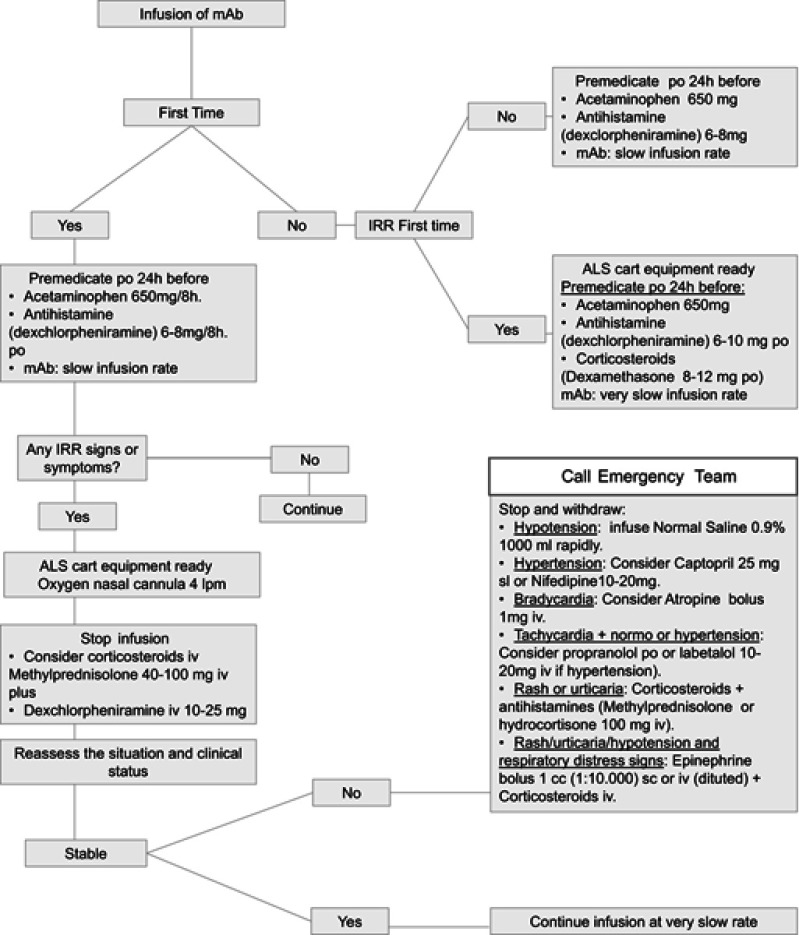

Considering the varied nature of infusion reactions, nurses and other health care practitioners must recognize the underlying nature of these events for a clear identification of patients at risk and for providing optimal prophylactic measures and management of symptoms.30 Nursing professionals must be aware of different strategies to tackle with MAb HR. They have to register the onset time of reaction and symptoms, vital signs and rate of infusion at the time of the event. A rapid initiation of emergency measures must be taken. As initial clinical measures are similar to all type of reactions and the knowledge of a standard protocol is mandatory. We provide an algorithm (Figure 1) that shows a daily-practice guide to manage the use of mAbs, in agreement with the Departments of Intensive Care, Oncology and Allergy of the University Hospital, Badajoz (Health Service of Extremadura, Spain).

Figure 1.

Algorithm proposed as a daily-practice guide to manage the use of mAb.

Abbreviations: IRR, infusion-related reaction; ALS, advanced life support; mAbs, monoclonal antibodies; po, per oral; iv, intravenous; sl, sublingual; sc, subcutaneous.

Readministration strategies to avoid or minimize the appearance of IRRs depending on the mAb and type of patient and reaction may include pre-medication (paracetamol, NSAIDs antihistamines, and corticosteroids) to reduce incidence or mitigate the symptoms. In addition, it may be necessary to slowdown infusion rates, or interrupt infusion, and in some cases, it could be necessary to reinitiate the treatment. This depends on the type of mAb and the severity of the IRR. Other measures could be to induce pharmacological desensitization and temporary immune tolerance15 or to fractionate the dose.13,18

Most technical files agree that the majority of mild or moderate IRRs are generally solved by slowing down the speed of infusion. Nevertheless, in case of a severe IRR, infusion must be stopped and reintroduction of treatment needs to be assessed. The decision to recommence an infusion will depend on the nature of the reaction and the choices made by the clinician. Each case must be considered separately, taking onboard the severity of the initial reaction, comorbidities, the aims of the therapy, and the risk of rechallenge versus the potential benefits of successful treatment.10

Although the information available in technical files with regard to the pharmacologic treatment of IRRs varies, there is some agreement on the need to establish symptomatic medical treatment, which can be the use of oxygen, beta-agonist agents, corticosteroids, intravenous fluid therapy or even antipyretics. The re-establishment of the mAb treatment may require the use of pre-medication.

Many studies have valued the efficacy of pre-medication to reduce or diminish symptoms of acute reactions due to mAbs. In the vast majority of the technical files, this is specifically recommended (with some exceptions as in the case of bevacizumab where the use of pre-medication is not systematically recommended).

Dotson et al (2016) carried out a study of which the main objective was to assess the safety and feasibility of a 60-min rituximab rapid infusion protocol (in B cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients) in the outpatient infusion center of a comprehensive cancer center. The conclusion of the study was that infusions can be safely administered over 60 mins and without steroid pre-medication in an experienced outpatient infusion center where patients are appropriately screened. The more rapid infusions can reduce the use of resources and increase satisfaction among nursing personnel.31

Ikegawa et al (2017) evaluated IRRs associated with cetuximab combination chemotherapy comprising an H1-receptor antagonist plus dexamethasone as anti-allergy pre-medications for patients with head and neck cancer. They reported that the occurrence of IRRs was lower compared with previous studies. Dexamethasone combined with an H1-receptor antagonist was useful for preventing allergic responses.32

When evaluating the first dose of trastuzumab, IRRs happened more commonly when patients were not administrated pre-medication compared to those who were. Previously unknown risk factors associated with the development of trastuzumab-associated IRRs have also been identified, more specifically the issues of obesity and advanced stage breast cancer, which may enable clinicians to identify patients at high risk for IRRs who could potentially benefit from pre-medication, although this hypothesis needs to be further validated.33

In patients with IRRs observed during previous obinutuzumab infusions, pre-medication with an oral analgesic such as acetaminophen or paracetamol and antihistamine before obinutuzumab treatment is required. In addition, pre-medication with corticosteroids should be considered as an option in patients with a high risk of severe IRRs.11,34

In dermatologic subjects with mild to moderate infusion reactions to infliximab, the prophylactic treatment of oral diphenhydramine and paracetamol should be administered at subsequent infusions, 90 mins before the start of each infusion. In patients who have manifested severe infusion reactions, pre-medication with IV hydrocortisone acetate 100 mg 20 mins before the infusion or with oral prednisone the day before the infusion is optional, according to the opinion of the clinician involved.19 Bartoli et al (2016) led a study which aimed to evaluate the incidence of IRRs in patients with joint inflammatory diseases (rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis) receiving treatment with infliximab with and without pre-medication. The combination of paracetamol, hydroxyzine, 6-methylprednisolone and ranitidine was more effective than paracetamol, esomeprazole, hydrocortisone, and chlorpheniramine maleate combination protocol to reduce the number of IRRs due to infliximab.35

Pre-medications are considered as standard procedure for keeping the risk for IRRs with mAbs to a minimum. However, due to the fact that most infusion reactions with mAbs take place following the first or second infusion, the value of pre medication on subsequent infusions may decrease.

For the type of patients that receive treatment with mAbs, a change or swift to second-line drugs after a HR can have a negative impact for their quality of life and life expectancy.36 New guidelines in the management and treatment of reactions, creating a new standard of care for mAb desensitization.17 There exist different protocols for desensitization that even allow a single day outpatient performance with trained 1-to-1 nursing. The protocol of Brenann et al (2009) proposes single day outpatient desensitization performed in a hospital associated infusion center with specially trained 1-to-1 nursing.37 Until now, it has been successfully desensitized mAb HSR to rituximab, ofatumumab, obinutuzumab, trastuzumab, cetuximab, tocilizumab, infliximab, etanercept, adalimumab, golimumab, certolizumab, brentuximab, bevacizumab and omalizumab.38

Conclusion

To conclude, mAbs can give rise to HR, such as anaphylaxis, IRRs, CRS or CARPA. Nurses responsible for the administration of mAbs should be able to promptly identify and grade IRRs, and to rapidly manage any adverse reaction linked with the use of these drugs in order to prevent dangerous risks for patients.

Although recommendations or published protocols exist on the management of IRRs caused by some mAbs, such as infliximab in dermatologic patients,19 obinutuzumab in chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients,34 natalizumab in multiple sclerosis,9 much remains to be known about the correct way to manage IRRs. In addition to this, the lack of uniform terminology entails an obstacle for clinical practice.

Considering the great number of mAbs available in current practice and those which will soon be authorized, it is mandatory to have clear guidelines that can give support to practitioners and nurses to help them respond quickly and safely to the different IRRs related to the use of these therapeutic drugs.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially financed by a grant of the Regional Goverment of Extremadura; European Regional Development Fund (FEDER; IB18101).

The collaboration of Dr Pedro Bobadilla from the Badajoz University Hospital, Allergology Department, is gratefully acknowledged.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Lushova A, Biazrova M, Prilipov A, Sadykova G, Kopylov T, Filatov A. Next-generation techniques for discovering human monoclonal antibodies. Mol Biol. 2017;51(6):782–787. doi: 10.1134/S0026893317060103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Machado NP, Tèllez GA, Castaño JC. Anticuerpos monoclonales: desarrollo físico y perspectivas terapéuticas [Monoclonal antibodies: physical development and therapeutic perspectives]. Infectio. 2006;10(3):186–197. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cui Y, Cui P, Chen B, Li S, Guan H. Monoclonal antibodies: formulations of marketed products and recent advances in novel delivery system. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2017;43(4):519–530. doi: 10.1080/03639045.2017.1278768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Merino AG. Anticuerpos monoclonales. aspectos básicos. [Monoclonal antibodies. Basic aspects]. Neurología. 2011;26(5):301–306. doi: 10.1016/j.nrl.2010.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brennan FR, Morton LD, Spindeldreher S, et al. Safety and immunotoxicity assessment of immunomodulatory monoclonal antibodies. mAbs. 2010;2(3):233–255. doi: 10.4161/mabs.2.3.11782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stanulovic V, Zelko R, Kerpel-Fronius S. Predictability of serious adverse reaction. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;49(3):185–190. doi: 10.5414/cp201497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stanulovic V, Kadlecova P, Zelko R, Kerpel-Fronius S. Earlier identification of risks: cumulative probability analysis of time to safety alerts for therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2015;53(7):499–503. doi: 10.5414/CP202283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cáceres MC, Durán-Gómez N, Guerrero-Martín J, Pérez Civantos DV, Carreto-Lemus MA, Postigo-Mota S. Interés para la enfermera de los nuevos anticuerpos monoclonales. una revolución terapéutica. Revista Rol De Enfermera. 2017;40(7–8):524–530. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Namey M, Halper J, O’leary S, Beavin J, Bishop C. Best practices in multiple sclerosis: infusion reactions versus hypersensitivity associated with biologic therapies. J Infus Nurs. 2010;33(2):98–111. doi: 10.1097/NAN.0b013e3181cfd36d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vogel WH. Infusion reactions: diagnosis, assessment, and management. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2010;14(2):E10. doi: 10.1188/10.CJON.E10-E21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korycka-Wołowiec A, Wołowiec D, Robak T. The safety profile of monoclonal antibodies for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2017;16(2):185–201. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2017.1264387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cima (aemps); 2018. Available from: https://cima.aemps.es/cima/publico/home.html.

- 13.Doessegger L, Banholzer ML. Clinical development methodology for infusion-related reactions with monoclonal antibodies. Clin Transl Immunol. 2015;4(7):e39. doi: 10.1038/cti.2015.14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kang SP, Saif MW. Infusion-related and hypersensitivity reactions of monoclonal antibodies used to treat colorectal cancer – identification, prevention, and management. J Support Oncol. 2007;5(9):451–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calogiuri G, Ventura MT, Mason L, et al. Hypersensitivity reactions to last generation chimeric, umanized and human recombinant monoclonal antibodies for therapeutic use. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14(27):2883–2891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. ATC/DDD Index 2019. Available from: http://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/.

- 17.Isabwe GAC, Neuer MG, de Las Vecillas Sanchez L, Lynch D, Marquis K, Castells M. Hypersensitivity reactions to therapeutic monoclonal antibodies: phenotypes and endotypes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;142(1):170. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters, American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, Joint Council of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Drug allergy: an updated practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;105(4):259–273. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2010.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Puig L, Sáez E, Lozano MJ, et al. Reacciones a la infusión de infliximab en pacientes dermatológicos. [reactions to infliximab infusions in dermatologic patients: consensus statement and treatment protocol]. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas. 2009;100(2):103–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheifetz A, Smedley M, Martin S, et al. The incidence and management of infusion reactions to infliximab: A large center experience. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(6):1315–1324. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07457.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maggi E, Vultaggio A, Matucci A. Acute infusion reactions induced by monoclonal antibody therapy. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2011;7(1):55–63. doi: 10.1586/eci.10.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chung CH, Mirakhur B, Chan E, et al. Cetuximab-induced anaphylaxis and IgE specific for galactose-α-1, 3-galactose. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(11):1109–1117. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Szebeni J. Complement activation-related pseudoallergy caused by liposomes, micellar carriers of intravenous drugs, and radiocontrast agents. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst. 2001;18(6):567–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szebeni J. Complement activation-related pseudoallergy: a new class of drug-induced acute immune toxicity. Toxicology. 2005;216(2):106–121. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2005.07.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fülöp T, Mészáros T, Kozma G, Szebeni J, Józsi M. Infusion reactions associated with the medical application of monoclonal antibodies: the role of complement activation and possibility of inhibition by factor H. Antibodies. 2018;7(1):14. doi: 10.3390/antib7010014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kroschinsky F, Stölzel F, von Bonin S, et al. New drugs, new toxicities: severe side effects of modern targeted and immunotherapy of cancer and their management. Crit Care. 2017;21(1):89. doi: 10.1186/s13054-017-1686-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shimabukuro-Vornhagen A, Gödel P, Subklewe M, et al. Cytokine release syndrome. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6(1):56. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0343-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cardona V, Cabañes N, Chivato T, De la Hoz B, Fernández Rivas M, Gangoiti Goikoetxea I. Guía de actuación en anafilaxia : Galaxia 2016. [Anaphylaxis Action Guide: Galaxia]. Available from: https://www.aepnaa.org/recursos/publicaciones-archivos/5851f6dd835b9ffc3f32220233dc3eca.pdf. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 29.US Department of Health and Human Services. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 5.0. national institutes of health, national cancer institute; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chung CH. Managing premedications and the risk for reactions to infusional monoclonal antibody therapy. Oncologist. 2008;13(6):725–732. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dotson E, Crawford B, Phillips G, Jones J. Sixty-minute infusion rituximab protocol allows for safe and efficient workflow. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(3):1125–1129. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2869-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ikegawa K, Suzuki S, Nomura H, et al. Retrospective analysis of premedication, glucocorticosteroids, and H1-antihistamines for preventing infusion reactions associated with cetuximab treatment of patients with head and neck cancer. J Int Med Res. 2017;45(4):0300060517713531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thompson LM, Eckmann K, Boster BL, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and management of infusion-related reactions in breast cancer patients receiving trastuzumab. Oncologist. 2014;19(3):228–234. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Snowden A, Hayden I, Dixon J, Gregory G. Prevention and management of obinutuzumab‐associated toxicities: Australian experience. Int J Nurs Pract. 2015;21(S3):15–27. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bartoli F, Bruni C, Cometi L, et al. Premedication prevents infusion reactions and improves retention rate during infliximab treatment. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35(11):2841–2845. doi: 10.1007/s10067-016-3351-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sloane D, Govindarajulu U, Harrow-Mortelliti J, et al. Safety, costs, and efficacy of rapid drug desensitizations to chemotherapy and monoclonal antibodies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;4(3):497–504. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2015.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brennan PJ, Bouza TR, Hsu FI, Sloane DE, Castells MC. Hypersensitivity reactions to mAbs: 105 desensitizations in 23 patients, from evaluation to treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124(6):1259–1266. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bonamichi-Santos R, Castells M. Diagnoses and management of drug hypersensitivity and anaphylaxis in cancer and chronic inflammatory diseases: reactions to taxanes and monoclonal antibodies. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018;54(3):375–385. doi: 10.1007/s12016-016-8556-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guidelines for preparing core clinical-safety information on drugs second edition – report of CIOMS working groups III and V • COUNCIL FOR INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS OF MEDICAL SCIENCES; 1999. Available from: https://cioms.ch/shop/product/guidelines-preparing-core-clinical-safety-information-drugs-second-edition-report-cioms-working-groups-iii-v/. Accessed May10, 2019.