Introduction

A great deal of attention is being paid to the plight of immigrants in the United States, particularly those who are undocumented and gain entry to the United States on our southern border. If undocumented immigrants become ill in the United States, there is a dilemma and often, difference of opinion over whose responsibility it is to deliver and pay for their care. When the care is life saving and expensive beyond their capability to pay, such as that for ESKD, the quandary is even more difficult.

Undocumented Immigrants with ESKD

Using numbers from 2008, a review estimated that there may be 6400 undocumented immigrants with ESKD with variation in numbers across states in the United States (1). For the most part, undocumented immigrants with ESKD have been in the United States for >5 years before their being diagnosed with ESKD, and many of them continue to work despite ESKD (2). In many states in the United States, undocumented patients with ESKD do not receive routine, thrice-weekly hemodialysis, to which their counterpart United States citizens are entitled, and they must instead present to an emergency department (ED) in nearly critical condition to receive hemodialysis, a situation termed “emergency-only hemodialysis.” Kidney transplantation is more elusive, despite reports of undocumented immigrants’ above-average willingness to donate their own organs (3).

Prior to a 2019 Colorado health policy change that expanded access to standard dialysis for undocumented immigrants with ESKD, undocumented immigrants with ESKD received emergency-only hemodialysis when they met “critically ill” criteria after presenting to the urgent care center or the ED. Emergency-only hemodialysis is provided in many states when undocumented immigrants with ESKD are “critically ill,” and the definition of “critical illness” varies from hospital to hospital but typically includes elevated potassium, low bicarbonate level, low oxygen saturation, and/or uremic symptoms. Patients are admitted for emergency-only hemodialysis and receive two consecutive hemodialysis sessions; then, they typically repeat the process again 6–7 days later. Similarly, undocumented immigrants with ESKD in Houston, Texas receive emergency-only hemodialysis after evaluation for “critically ill” criteria in the ED. However, patients receive one hemodialysis session and repeat the process two to three times per week. Arteriovenous (AV) access for hemodialysis also varies, and in Denver, patients receive an AV fistula or graft, whereas patients in Houston initiate emergency-only hemodialysis with a temporary or tunneled catheter. In San Francisco, California, patients receive routine, thrice-weekly hemodialysis with an AV fistula or graft and only receive emergent dialysis if they develop complications between treatments or fail to adhere to this treatment schedule.

Outcomes for Patients Who Rely on Emergency-Only Hemodialysis

Undocumented immigrants with ESKD that rely on emergency-only hemodialysis describe significant physical and psychosocial distress. Patients describe anxiety and a distressing weekly crescendo of symptoms that is necessary to trigger an ED visit for emergency-only hemodialysis. Although patients understood that emergency-only hemodialysis was substandard care, they expressed appreciation for their care, because they would not have access to dialysis in their country of origin (2).

In a study in three cities in different states (Denver, CO; Houston, TX; and San Francisco, CA), the mean 5-year relative hazard of mortality for patients who rely on emergency-only hemodialysis was >14-fold higher compared with those who receive standard hemodialysis. They also spend tenfold more time in the hospital and less time in the outpatient setting compared with those receiving standard hemodialysis (4). The lower mortality and the lower health care utilization among undocumented immigrants who receive standard hemodialysis were confirmed in a follow-up study that compared undocumented immigrants who receive emergency-only hemodialysis with undocumented privately insured patients who receive standard hemodialysis (5). Emergency-only hemodialysis is expensive from a societal perspective, although to a hospital or health care system, it may be reimbursed by emergency Medicaid. A cost-effectiveness analysis from both societal and health care system perspectives would be helpful. A study of 32 patients previously receiving emergency only hemodialysis dialysis demonstrated a reduction in emergency room visits, days hospitalized, and transfusions after obtaining commercial health insurance and receiving routine thrice-weekly hemodialysis (6). A retrospective study of undocumented immigrants with ESKD who died after presenting to the hospital for emergency-only hemodialysis showed the majority had an electrical rhythm disturbance and died of cardiac arrest (7). Clinicians who provide emergency-only hemodialysis care report emotional exhaustion from witnessing needless suffering and high mortality as well as moral distress from the perception of propagating injustice (8).

Variation in the Availability of Standard Hemodialysis in the United States

Variation in the availability of standard versus emergency-only hemodialysis is driven, in part, by reimbursement for care. Undocumented immigrants are excluded from the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Public Law 111–148) as well as federally funded insurance programs, such as traditional Medicaid and the diagnostically based 1972 ESKD Amendments to the Social Security Act (Public Law 92–603). To receive federal reimbursement for care, the 1986 Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act states that funds are available to states for medical care provided to undocumented immigrants only if “such care and services are necessary for the treatment of an emergency medical condition.” To change this would take an act of Congress, because it is expressly called out in a statute (Social Security Act §1903[v][2][C]).

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) manual restates this definition and includes that services for an emergency medical condition cannot include care related to organ transplantation. What is not widely appreciated is that, beyond these general requirements, the CMS and the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) defer to states to identify which medical conditions and circumstances qualify as an emergency. The OIG audits a state’s compliance with its own state definition of an emergency medical condition and has not previously raised concerns in states where dialysis for undocumented immigrants is covered.

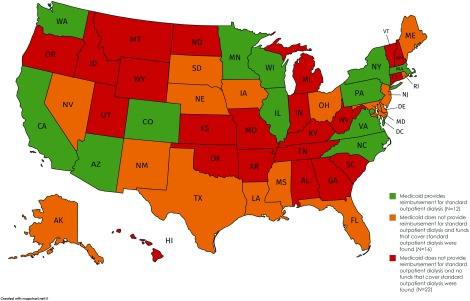

There is not an inventory of those states that include dialysis as an emergency medical condition. Therefore, we identified the emergency Medicaid language as well as the dialysis and transplantation language for kidney replacement therapy in the eligibility manual in each of the 50 states in the United States. We used this information along with information from local physicians, National Kidney Foundation local affiliates, and the ESKD Networks to catalog where Medicaid provides reimbursement for standard hemodialysis for undocumented immigrants with ESKD and where we found other funds (e.g., state risk pools and health system charity care) that cover standard kidney replacement therapy (Figure 1). In Arizona, for example, the emergency Medicaid definition includes “outpatient dialysis services for a Federal Emergency Services Member with ESKD” (AZ Admin. Code R9-22-217). In contrast, North Carolina, rather than changing the emergency Medicaid definition (which is similar to the federal definition), includes a section in their manual titled “Procedures to Establish Authorization Dates for Ongoing Hemodialysis” that includes dialysis treatment (NC Integrated Eligibility Manual, Section 15190 Coverage for Emergency Medical Services).

Figure 1.

Provision of standard outpatient dialysis for undocumented immigrants with ESKD in the United States as of March 2019.

Separate from federal reimbursement for care, undocumented immigrants with ESKD have acquired private health insurance plans off the marketplace exchange. Normally, these plans are cost prohibitive for undocumented immigrants given their socioeconomic status; however, nonprofit entities provide needy patients with ESKD with charitable support (9). There is sometimes variation in the availability of standard hemodialysis within states where there is no state/federal reimbursement for standard hemodialysis, because there are county-funded and sometimes, safety net hospital-funded free-standing outpatient standard hemodialysis centers for undocumented immigrants (10). Illinois recently provided transplantation for undocumented immigrants.

Need for Change

The availability of standard hemodialysis varies throughout the country, leaving many undocumented immigrants with ESKD with no chance for survival unless they rely on emergency-only hemodialysis. Emergency-only hemodialysis is vexing for patients and leads to suboptimal health outcomes compared with standard care. Emergency-only hemodialysis also puts clinicians in the position of intentionally delivering inferior care (8). Although politically difficult, in part due to constrained Medicaid funding and the effect on resources for all patients and not just those with ESKD, if the states that do not currently define need for dialysis as an emergent medical condition were to adopt the position of the states that have, many deaths, unnecessary suffering, and valueless health care utilization could be prevented. Policy makers, taxpayers, health care providers, and citizens in different states should join together to examine the evidence and take purposeful action toward clinically sound, humane, and economically sensible health policy for undocumented immigrants with ESKD.

Disclosures

Dr. Cervantes, Mr. Mundo, and Dr. Powe have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by the Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development Award from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, grant 2015212 from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation (University of Colorado School of Medicine fund to retain clinical scientist), and National Institute for Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases award K23DK117018.

The funding agencies had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The content of this article does not reflect the views or opinions of the American Society of Nephrology (ASN) or CJASN. Responsibility for the information and views expressed therein lies entirely with the author(s).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Rodriguez RA: Dialysis for undocumented immigrants in the United States. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 22: 60–65, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cervantes L, Fischer S, Berlinger N, Zabalaga M, Camacho C, Linas S, Ortega D: The illness experience of undocumented immigrants with end-stage renal disease. JAMA Intern Med 177: 529–535, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shen JI, Hercz D, Barba LM, Wilhalme H, Lum EL, Huang E, Reddy U, Salas L, Vangala S, Norris KC: Association of citizenship status with kidney transplantation in Medicaid patients. Am J Kidney Dis 71: 182–190, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cervantes L, Tuot D, Raghavan R, Linas S, Zoucha J, Sweeney L, Vangala C, Hull M, Camacho M, Keniston A, McCulloch CE, Grubbs V, Kendrick J, Powe NR: Association of emergency-only vs standard hemodialysis with mortality and health care use among undocumented immigrants with end-stage renal disease. JAMA Intern Med 178: 188–195, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nguyen OK, Vazquez MA, Charles L, Berger JR, Quiñones H, Fuquay R, Sanders JM, Kapinos KA, Halm EA, Makam AN: Association of scheduled vs emergency-only dialysis with health outcomes and costs in undocumented immigrants with end-stage renal disease. JAMA Intern Med 179: 175–183, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sheikh-Hamad D, Paiuk E, Wright AJ, Kleinmann C, Khosla U, Shandera WX: Care for immigrants with end-stage renal disease in Houston: A comparison of two practices. Tex Med 103: 54–58, 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cervantes L, O’Hare A, Chonchol M, Hull M, Van Bockern J, Thompson M, Zoucha J: Circumstances of death among undocumented immigrants who rely on emergency-only hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 1405–1406, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cervantes L, Richardson S, Raghavan R, Hou N, Hasnain-Wynia R, Wynia MK, Kleiner C, Chonchol M, Tong A: Clinicians’ perspectives on providing emergency-only hemodialysis to undocumented immigrants: A qualitative study. Ann Intern Med 169: 78–86, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raghavan R: New opportunities for funding dialysis-dependent undocumented individuals. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 370–375, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raghavan R: When access to chronic dialysis is limited: One center's approach to emergent hemodialysis. Semin Dial 25: 267–271, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]