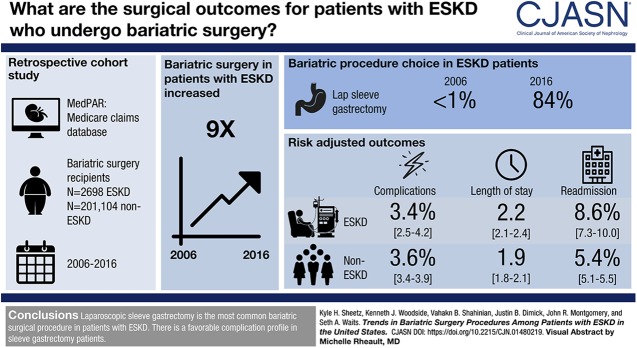

Visual Abstract

Keywords: Outcomes; Gastric Bypass; Patient Readmission; Bariatric Surgery; Gastrectomy; obesity; Health Status; Medicare; Kidney Failure, Chronic; Laparoscopy

Abstract

Background and objectives

Despite the potential for improving health status or increasing access to transplantation, national practice patterns for bariatric surgery in obese patients with ESKD are poorly understood. The purpose of this study was to describe current trends in surgical care for this population.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

Using 100% Medicare data, we identified all beneficiaries undergoing bariatric surgery in the United States between 2006 and 2016. We evaluated longitudinal practice patterns using linear regression models. We also estimated risk-adjusted complications, readmissions, and length of stay using Poisson regression for patients with and without ESKD.

Results

The number of patients with ESKD undergoing bariatric surgery increased ninefold between 2006 and 2016. The proportional use of sleeve gastrectomy increased from <1% in 2006 to 84% in 2016. For sleeve gastrectomy, complication rates were similar between patients with and without ESKD (3.4% versus 3.6%, respectively; difference, −0.3%; 95% confidence interval, −1.3% to 0.1%; P=0.57). However, patients with ESKD had more readmissions (8.6% versus 5.4%, respectively; difference, 3.2%; 95% confidence interval, 1.9% to 4.6%; P<0.001) and slightly longer hospitals stays (2.2 versus 1.9 days, respectively; difference, 0.3; 95% confidence interval, 0.1 to 0.4; P<0.001).

Conclusions

This study suggests that laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy has replaced Roux-en-Y gastric bypass as the most common bariatric surgical procedure in patients with ESKD. The data also demonstrate a favorable complication profile in patients with sleeve gastrectomy.

Introduction

Nearly 40% of adults in the United States are now classified as obese (1). There is a considerable body of evidence suggesting that obese patients with CKD have worse access to transplantation, higher rates of delayed graft function, and lower 1-year graft and overall survival compared with other nonobese adults (2–6). Because of this epidemic, the American Society of Transplant Surgeons recently formed an obesity task force to evaluate whether current practice standards are generalizable to this growing and high-risk patient population (7). Expanding the use and indications for bariatric surgery in patients with ESKD on dialysis has been an early focus and is gaining momentum.

Despite this, current practice patterns for bariatric surgery in this population are not well understood. Those that favor greater use cite prior work suggesting that bariatric surgery improves kidney function and associated comorbidities and may even facilitate access to transplantation through greater weight loss (8–14). Others are more cautious—pointing to early single-center studies of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass that found higher rates of postoperative complications and risks for calcium dysregulation and oxalate deposition in the native or transplant kidney (15–17). However, recent population-based evaluations in the general population suggest that laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy is now the favored surgical approach and represents >70% of all bariatric operations (18). With fewer complications and metabolic derangements, it is important to understand how this shift in practice affects patients with ESKD and the weight loss strategies used by the transplant community overall.

Using 100% Medicare claims for the years 2006–2016, we assessed national practice patterns for bariatric surgery in the ESKD population. We then estimate modern day outcomes and resource utilization for these patients compared with other Medicare beneficiaries without ESKD.

Materials and Methods

Data Source and Study Population

We used data from the 100% capture Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MedPAR) files for the years 2006–2016. We extracted data for patient age, demographic information, geographic location, and comorbidities. We identified patients undergoing bariatric surgery using International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) or International Classification of Disease, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes. These procedures included laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, and laparoscopic gastric banding (Supplemental Table 1 has a full description of study cohort selection methodology). We excluded open procedures, because these are increasingly uncommon, are performed only in unique clinical scenarios, and represented <5% of the original cohort. Missing data were present in <1% of the original cohort and subsequently excluded from our analyses.

We linked patient- and hospital-level data from the MedPAR files to the American Hospital Association Annual Survey for each corresponding year to obtain additional information on hospital characteristics, such as bed size, teaching status, and operating business model (e.g., not for profit). These data also included information on which hospitals in the study cohort also perform kidney transplantation. Medicare includes a special designating variable for patients with ESKD. This information was corroborated with ICD-9 (58.56) or ICD-10 (N18.6) diagnosis codes from the primary claims file to identify all patients with ESKD. We further verified the status of a prior kidney transplant and current dialysis status. Prior transplants were identified by ICD-9 (V42.0) and ICD-10 (Z94.0) codes. Patients were considered to be on dialysis if they had ESKD as well as ICD-9 (V45.11) and ICD-10 (Z99.2) codes for current dialysis status. We reported patient and hospital characteristics across three time periods to highlight any potential changes in the study cohort that may influence practice patterns or our primary outcomes measures.

Outcome Measures

We used ICD-9-CM/ICD-10-CM codes to identify 30-day postoperative complications, such as pulmonary failure (unplanned intubation and need for mechanical ventilation), pneumonia, myocardial infarction, deep venous thrombosis/pulmonary embolism, kidney failure, surgical site infection, gastrointestinal bleeding, and hemorrhage. The complications of kidney failure and/or dialysis were excluded as postoperative outcomes for patients with ESKD. These complications represent a subset of codes with the highest sensitivity and specificity (19). Readmissions were identified as any claim for any readmission to the hospital within 30 days after discharge. Length of stay was calculated from date of admission to date of discharge.

Statistical Analyses

There were two goals of these analyses. We first sought to characterize the proportional use of each bariatric procedure in patients with ESKD over time. For this analysis, we calculated raw proportions for each procedure by dividing the number of patients undergoing that specific operation by the total number of patients with ESKD undergoing bariatric surgery in a given year. We used linear regression to test the association (trend) between time in years treated as a continuous variable and the proportional use of each procedure as the outcome.

Next, we estimated risk-adjusted rates of complications and readmissions and risk-adjusted length of stay using multilevel mixed effects regression models. Patient-level covariates were included as fixed effects, and the hospital-level effects were modeled as a random effect. For dichotomous outcomes (complications and readmissions), we fit Poisson regression models accounting for patient age, race, sex, procedure year, and 27 Elixhauser comorbidities as fixed effects in a manner that has been previously validated using Medicare claims data (20). These variables were treated as potential confounders. We further adjusted for certain hospital characteristics, such as bed size, kidney transplant program status, overall bariatric surgical volume, and teaching status, as fixed effects. We modeled a random effects parameter at the hospital level. We generated normal-based confidence intervals derived from bootstrapping with 1000 replications, where draws were made at the hospital level to deal with clustering at the hospital level. Risk-adjusted length of stay was performed in an identical manner as well using a Poisson regression model. We performed an additional sensitivity analysis for length of stay using a linear model.

For complications and readmissions, we estimated these outcomes for patients with and without ESKD in two ways. ESKD is our primary exposure in these analyses. We use this exposure to then predict outcomes for each group of patients. We first included all patients in a single model with the procedure type as a categorical dummy variable. We performed a secondary analysis with each procedure individually and obtained similar results. To account for possible time trends toward better outcomes, we estimated outcomes from each model with and without a categorical dummy variable for the claim year. Finally, to address any issues that may arise from erroneous categorization of patients who had previously undergone kidney transplant and then, subsequently resumes dialysis, we performed a sensitivity analysis excluding all patients with a history of kidney transplant both on and off dialysis. All risk-adjusted rates were derived from the primary models using marginal means.

All statistical analyses were performed using STATA statistical software version 14 (College Station, TX). We used a two-sided approach at the 5% significance level for all hypothesis testing. This study was deemed exempt by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan.

Results

Patient and Hospital Characteristics

Descriptive statistics for the study population and United States hospitals that perform bariatric surgery are included in Table 1. There were few clinically meaningful changes in either patient group over time. There was an increase in coded illness severity in patients with and without ESKD. For example, from 2006 to 2008, patients with ESKD had a median of three (interquartile range, two to four) comorbidities and that number increased to four (interquartile range, three to five) by 2014–2016. More hospitals offered bariatric surgery over time, increasing from 808 in 2006–2008 to 1191 in 2014–2016. The proportion of patients undergoing surgery in centers that offer kidney transplant decreased from 30% to 21% over the study period. For patients with ESKD, that proportion was significantly higher, ranging from 50% in 2006–2008 to 38% from 2009 to 2013.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients who underwent bariatric surgery and hospitals that perform bariatric surgery, 2006–2016

| Characteristic | Time Period | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2006–2008, n=32,577 | 2009–2013, n=92,223 | 2014–2016, n=76,879 | |

| Patients with ESKD | |||

| Patients, no. (%) | 275 (10) | 1094 (41) | 1329 (49) |

| Age, yr, mean (SD) | 46 (11) | 48 (10) | 49 (10) |

| Men, no. (%) | 115 (42) | 453 (41) | 566 (43) |

| White race, no. (%) | 135 (49) | 489 (45) | 612 (46) |

| Black race, no. (%) | 117 (43) | 493 (45) | 571 (49 |

| Comorbidities, mean (SD) | 3.2 (1) | 3.9 (1) | 4.4 (1) |

| Comorbidities, median (IQR) | 3 (2–4) | 4 (3–5) | 4 (3–5) |

| Prior kidney transplant, no. (%) | 8 (3) | 34 (3) | 45 (3) |

| Hospital characteristics | |||

| Hospitals, no. | 147 | 338 | 474 |

| No. of beds, no. (% of patients) | |||

| <200 | 40 (15) | 173 (16) | 166 (13) |

| 200–349 | 42 (16) | 190 (18) | 295 (23) |

| 350–499 | 63 (24) | 252 (23) | 265 (20) |

| ≥500 | 123 (46) | 465 (43) | 587 (45) |

| Profit status, no. (% of patients) | |||

| Not for profit | 197 (74) | 778 (72) | 893 (68) |

| For profit | 45 (17) | 222 (21) | 292 (22) |

| Other | 26 (11) | 80 (7) | 128 (10) |

| Teaching hospital, no. (% of patients) | 131 (49) | 392 (36) | 474 (36) |

| Kidney transplant center, no. (% of patients) | 136 (50) | 414 (38) | 575 (43) |

| Patients without ESKD | |||

| Patients, no. (%) | 33,240 (17) | 91,419 (46) | 76,445 (38) |

| Age, yr, mean (SD) | 55 (12) | 556 (12) | 57 (11) |

| Men, no. (%) | 8520 (26) | 24,226 (27) | 19,658 (26) |

| White race, no. (%) | 27,303 (82) | 72,781 (80) | 58,819 (77) |

| Black race, no. (%) | 4486 (14) | 14,138 (16) | 13,398 (18) |

| Comorbidities, mean (SD) | 2.2 (1.1) | 2.5 (1.3) | 2.6 (1.5) |

| Comorbidities, median (IQR) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (2–3) | 2 (2–3) |

| Prior kidney transplant, no. (%) | 87 (0.3) | 267 (0.3) | 267 (0.4) |

| Hospital characteristics | |||

| Hospitals, no. | 808 | 952 | 1191 |

| No. of beds, no. (% of patients) | |||

| <200 | 7051 (22) | 18,330 (20) | 17,258 (23) |

| 200–349 | 7319 (23) | 23,004 (25) | 19,468 (26) |

| 350–499 | 7384 (23) | 21,120 (23 | 15,668 (21) |

| ≥500 | 10,555 (33) | 28,689 (32) | 23,172 (31) |

| Profit status, no. (% of patients) | |||

| Not for profit | 23,049 (71) | 63,664 (70) | 52,894 (70) |

| For profit | 5479 (17) | 18,786 (21) | 16,535 (22) |

| Other | 3781 (12) | 8693 (10) | 6137 (8) |

| Teaching hospital, no. (% of patients) | 10,322 (32) | 25,159 (28) | 16,403 (22) |

| Kidney transplant center, no. (% of patients) | 9789 (30) | 24,428 (27) | 16,042 (21) |

P values for all trends across time periods <0.01 when calculated using Spearman rank correlation test. Comorbidities were calculated from the list of 27 Elixhauser categories. IQR, interquartile range.

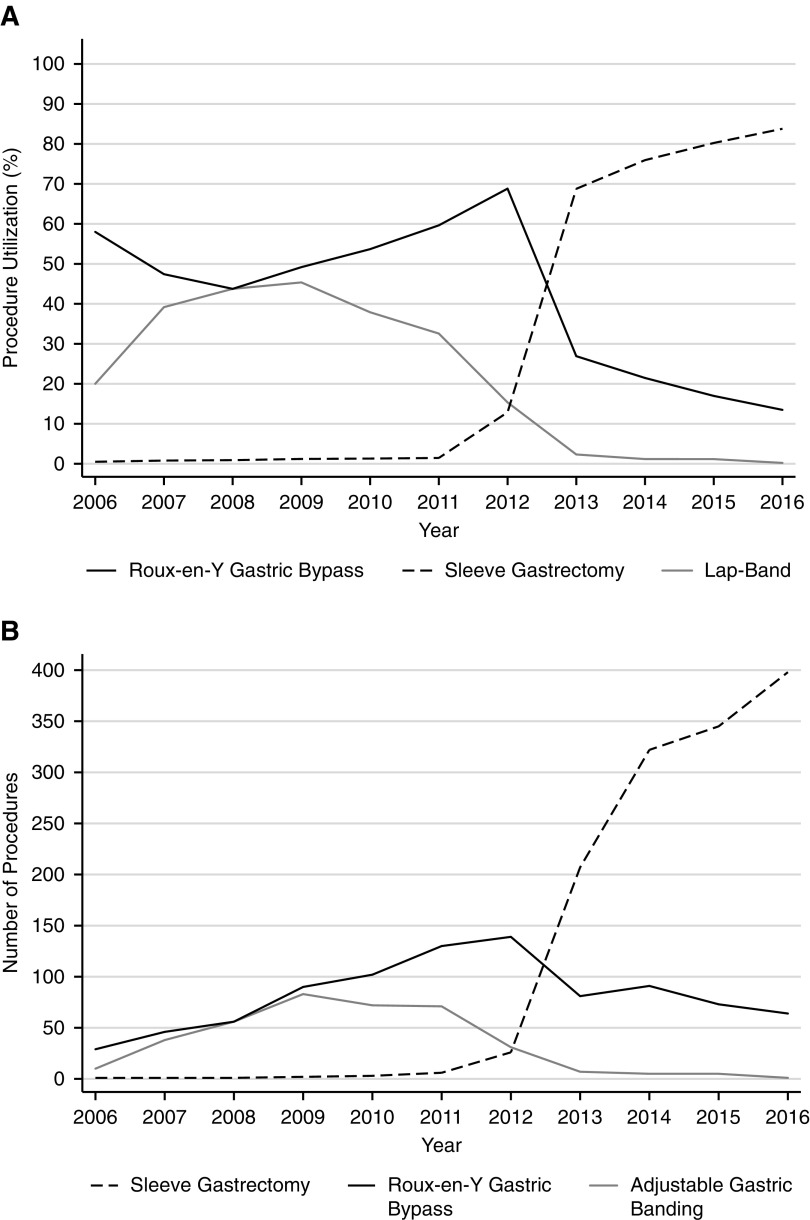

Trends in the Type of Bariatric Surgery for Patients with ESKD

Figure 1 displays the overall volume and proportional use of each bariatric surgical procedure in patients with ESKD. The use of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy increased significantly from <1% in 2006 to 84% in 2016 (10% per year increase; P<0.001). In contrast, the use of laparoscopic gastric banding declined precipitously over the study period and represented <1% of patients by 2016 (4% per year decrease; P=0.004). To a lesser extent, the use of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass also declined from 58% in 2006 to 13% in 2016 (4% per year decrease; P=0.02). The proportional use in patients without ESKD mirrors trends observed in the ESKD cohort.

Figure 1.

Bariatric procedures in Medicare beneficiaries with ESKD description. (A) Proportional use of bariatric surgical procedures and (B) total number of procedures in Medicare beneficiaries with ESKD from 2006 to 2016.

Outcomes for Patients with and without ESKD

For laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, complication rates were similar between patients with (3.4%; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 2.5% to 4.2%) and without ESKD (3.6%; 95% CI, 3.4% to 3.9%) (Table 2). Unadjusted rates of specific complications are included in Supplemental Table 2. Patients with ESKD had slightly longer length of stay (2.2 days; 95% CI, 2.1 to 2.4) compared with those without ESKD (1.9 days; 95% CI, 1.8 to 2.1) after sleeve gastrectomy. A similar trend was observed for readmissions, where patients with ESKD were readmitted in 8.6% of cases (95% CI, 7.3% to 10.0%) compared with 5.4% (95% CI, 5.1% to 5.5%) in patients without ESKD. Trends in outcome differences between patients with and without ESKD were similar for the other procedures. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass was associated with more complications, longer hospital stays, and more readmissions for all patients.

Table 2.

Risk-adjusted postoperative outcomes for patients with and without ESKD

| Outcome | Risk-Adjusted Rates or Means | Absolute Difference | Mean Effect | P Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with ESKD | Patients without ESKD | ||||

| Postoperative complications, % | |||||

| Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy | 3.4 | 3.6 | −0.3 | −0.9 | 0.57 |

| 95% CI | 2.5 to 4.2 | 3.4 to 3.9 | −1.3 to 0.1 | −0.4 to 0.2 | |

| Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass | 6.4 | 6.2 | 0.2 | 0.03 | 0.84 |

| 95% CI | 5.0 to 7.6 | 5.7 to 6.6 | −1.4 to 1.7 | −0.2 to 0.3 | |

| Laparoscopic gastric banding | 2.5 | 2.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.66 |

| 95% CI | 1.9 to 3.1 | 1.9 to 2.5 | −1.1 to 1.7 | −0.4 to 0.7 | |

| Length of stay, d | |||||

| Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy | 2.2 | 1.9 | 0.3 | 0.1 | <0.001 |

| 95% CI | 2.1 to 2.4 | 1.8 to 2.1 | 0.1 to 0.4 | 0.0 to 0.2 | |

| Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass | 3.5 | 2.6 | 0.9 | 0.3 | <0.001 |

| 95% CI | 3.0 to 4.0 | 2.5 to 2.7 | 0.4 to 1.4 | 0.2 to 0.4 | |

| Laparoscopic gastric banding | 1.6 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.02 |

| 95% CI | 1.4 to 1.7 | 1.2 to 1.4 | 0.1 to 0.5 | 0.1 to 0.3 | |

| Readmission, % | |||||

| Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy | 8.6 | 5.4 | 3.2 | 0.5 | <0.001 |

| 95% CI | 7.3 to 10.0 | 5.1 to 5.5 | 1.9 to 4.6 | 0.3 to 0.6 | |

| Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass | 16.2 | 9.1 | 7.1 | 0.6 | <0.001 |

| 95% CI | 14.3 to 18.1 | 8.8 to 9.4 | 5.2 to 9.0 | 0.4 to 0.7 | |

| Laparoscopic gastric banding | 8.1 | 4.6 | 3.4 | 0.6 | 0.02 |

| 95% CI | 5.2 to 10.9 | 4.3 to 4.9 | 0.1 to 6.4 | 0.2 to 0.9 | |

Relative differences for binary outcomes (complications and readmission) reported as mean effects. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

P values are for the absolute difference statistic. Outcomes were estimated from a single model for all procedures. All models were adjusted for age, race, sex, and 27 Elixhauser categories for comorbidities: congestive heart failure, valvular disease, pulmonary circulation disease, peripheral vascular disease, paralysis, neurologic disorders, chronic pulmonary disease, diabetes with and without complications, hypothyroidism, kidney failure, liver disease, peptic ulcer disease, AIDS, lymphoma, metastatic cancer, solid tumor without metastasis, rheumatoid arthritis, coagulopathy, obesity, recent weight loss in last 6 months, fluid or electrolyte disorders, chronic blood loss anemia, other deficiency anemias, alcohol abuse, drug abuse, psychoses, depression, and hypertension.

Risk-adjusted estimates were similar in sensitivity analyses that accounted for time, suggesting that there was no significant time-varying effect on outcomes (Supplemental Tables 3–6). Excluding patients with prior kidney transplant who are either on or not currently on dialysis did not alter our findings, and these patients represented just 0.4% of the total ESKD cohort. Estimates for length of stay from a linear model were identical.

Discussion

This longitudinal, population-based study evaluated changes in bariatric surgical practice patterns for patients with ESKD. Annual patient volumes increased dramatically between 2006 and 2016: more than ninefold within the context of a 1.5-fold increase in the overall prevalence of ESKD over the same time period. Over the decade, laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy surpassed all others as the most common bariatric surgical procedure in patients with ESKD. Relative to other procedures, like Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy had a more favorable complication profile, shorter average length of stay, and fewer readmissions. These data add to the growing body of evidence suggesting that bariatric surgery is safe, efficient, and increasingly common in Medicare beneficiaries with ESKD. Moreover, these trends match what has already occurred in patients without ESKD—suggesting that surgeons are treating patients with ESKD as they would any other.

Multiple prior studies suggest that bariatric surgery is beneficial for obese patients with CKD (8,21–23). For example, bariatric surgery was associated with an increase in access to kidney transplantation as a result of significant weight loss (24). Others have shown that it improves post-transplant outcomes—including lower rates of delayed graft function and higher 1-year patient and graft survival (4–6). In the CKD population overall, bariatric surgery and concomitant weight loss improved residual kidney function and delayed the onset of dialysis (25,26). However, most prior work has been limited to single-center studies or was generated before the diffusion of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, and thus, it may not reflect modern day outcomes. Our study goes beyond this to provide updated, population-based outcomes that reflect the dramatic shift toward sleeve gastrectomy and away from Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

Perceptions of surgical risk continue to be a fundamental barrier to broader adoption of weight loss surgery in patients with ESKD. Surgeons and referring providers may believe that short-term safety for these patients is markedly worse. Anecdotally, some centers even have policies that establish relative contraindications to weight loss surgery in patients with kidney disease. The obesity paradox has also been regarded as a barrier to widespread adoption of aggressive weight loss in patients with ESKD on dialysis. Large observational studies found that higher body mass index (BMI) in patients with ESKD was associated with 31% increase in survival on dialysis—a finding counter to what is observed in patients without ESKD (27,28). This may also drive hesitation from primary care physicians and nephrologists to refer patients with ESKD for bariatric surgery consultation. However, our understanding of the obesity paradox has improved over time, suggesting that patients with higher BMI may be less likely to have sarcopenia or poor nutritional status, which seems to be the more important determinant of long-term outcomes (29–34).

Our results should be interpreted within the context of several limitations. Because our data are derived from the Medicare population, it may not be generalizable to all patients or practice settings. However, a large proportion of patients with ESKD are covered, at least in part, by Medicare. Although some may argue that our comparison group is predisposed to poor outcomes (elderly or disabled beneficiaries without ESKD) and that this may bias our estimates, the raw and risk-adjusted outcome rates are low by any comparison. In other words, even if this is true, it does not detract from the primary finding that these operations have a favorable safety profile in the ESKD population. It is also possible that our ability to accurately identify patients with ESKD but a functioning transplant is limited by coding. This could bias our outcomes toward lower complication rates in the ESKD cohort; however, it is unlikely to change our primary findings given the small number of patients that this may affect. It is also possible that the complications that we report do not fully reflect the true incidence of all complications—especially because we include postoperative (acute) kidney failure as a complication for only patients without ESKD. To address this, we included other outcomes, such as length of stay and readmission, to reflect other measures that reflect a higher level of care complexity that could be associated with complications. This is particularly relevant within the context of surgeons’ learning curves for procedures that are being rapidly adopted. We were unable to account for BMI in this analysis. However, each patient qualified for bariatric surgery, which requires a BMI of at least 35 kg/m2 and at least one obesity-related comorbidity. Thus, the patient population is reasonably standardized through Medicare’s eligibility criteria alone.

In many ways, the transplant (nephrology) and bariatric surgical communities are well suited to partner in the care of these complex patients. Both disciplines rely on multidisciplinary teams that include medical and surgical care as well as robust ancillary support services (e.g., nutrition, pharmacy, and social work). Both are also familiar with providing care in the context of tight regulatory environments, where significant scrutiny is placed on outcomes. Most importantly, obese patients with ESKD require longitudinal care, a particular strength of nephrologists, in addition to transplant and bariatric surgery. More work will need to be done to better understand precisely why these changes in practice have occurred. It remains unclear whether this was an intentional shift, was due to particular outcome benefits, or is attributed to other issues (i.e., ease of operation or patient preference). These issues will be particularly important to the ESKD population.

Our findings highlight the need for greater collaboration between nephrologists, primary care physicians, and surgeons. Within the context of our findings, bariatric surgery is safe, and ESKD should not be considered a contraindication for surgical evaluation. The overall shift in practice toward sleeve gastrectomy—with its more favorable short- and long-term complication profiles—may facilitate greater access to transplantation for many patients. That said, readmission rates remained higher in the ESKD population. This may reflect the incidence of additional complications or appropriate care (e.g., avoiding a potentially risky complication), a distinction that will require greater attention as bariatric surgery is offered to larger groups of patients with ESKD. In the longer term, however, the surgical and nephrology community should move toward trials that assess its efficacy along the continuum of care from the diagnosis of CKD, initiation of dialysis, and transplant evaluation to the post-transplant period. With each comes challenges in the adoption of new treatment strategies and questions around the cost-effectiveness of bariatric surgery relative to other weight loss interventions. Nonetheless, obesity rates will continue to rise in the transplant population—bringing with it more opportunities to optimize the care of these particularly challenging patients.

Disclosures

Dr. Dimick, Dr. Montgomery, Dr. Shahinian, Dr. Sheetz, Dr. Waits, and Dr. Woodside have nothing to disclose.

Funding

Dr. Dimick is supported by grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R01HS023597), National Institutes of Health and National Institute on Aging (R01AG039434). Dr. Sheetz is supported by funding from an Association for Academic Surgery Resident Research Fellowship and a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2T32HS000053-27).

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Bariatric Surgery for ESKD Patients: Why, When, and How?,” on pages 1125–1127.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.01480219/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Table 1. Information on selection of the study cohort.

Supplemental Table 2. Unadjusted rates of specific complications for patients with and without ESKD.

Supplemental Table 3. Raw data for procedure utilization.

Supplemental Table 4. Specific codes for bariatric surgery and our exclusion criteria diagram.

Supplemental Table 5. Risk-adjusted outcome rates over time for patients with ESKD.

Supplemental Table 6. All complication codes for ICD-9 and ICD-10 specifications.

References

- 1.NCHS: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, 2017

- 2.Segev DL, Simpkins CE, Thompson RE, Locke JE, Warren DS, Montgomery RA: Obesity impacts access to kidney transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 349–355, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gill JS, Hendren E, Dong J, Johnston O, Gill J: Differential association of body mass index with access to kidney transplantation in men and women. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 951–959, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hill CJ, Courtney AE, Cardwell CR, Maxwell AP, Lucarelli G, Veroux M, Furriel F, Cannon RM, Hoogeveen EK, Doshi M, McCaughan JA: Recipient obesity and outcomes after kidney transplantation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 30: 1403–1411, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cannon RM, Jones CM, Hughes MG, Eng M, Marvin MR: The impact of recipient obesity on outcomes after renal transplantation. Ann Surg 257: 978–984, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meier-Kriesche HU, Arndorfer JA, Kaplan B: The impact of body mass index on renal transplant outcomes: A significant independent risk factor for graft failure and patient death. Transplantation 73: 70–74, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Society of Transplant Surgeons. Available at: http://www.asts.org. Accessed February 9, 2019

- 8.Kim Y, Jung AD, Dhar VK, Tadros JS, Schauer DP, Smith EP, Hanseman DJ, Cuffy MC, Alloway RR, Shields AR, Shah SA, Woodle ES, Diwan TS: Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy improves renal transplant candidacy and posttransplant outcomes in morbidly obese patients. Am J Transplant 18: 410–416, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schauer PR, Kashyap SR, Wolski K, Brethauer SA, Kirwan JP, Pothier CE, Thomas S, Abood B, Nissen SE, Bhatt DL: Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy in obese patients with diabetes. N Engl J Med 366: 1567–1576, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, Wolski K, Brethauer SA, Navaneethan SD, Aminian A, Pothier CE, Kim ES, Nissen SE, Kashyap SR; STAMPEDE Investigators : Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes--3-year outcomes. N Engl J Med 370: 2002–2013, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, Wolski K, Aminian A, Brethauer SA, Navaneethan SD, Singh RP, Pothier CE, Nissen SE, Kashyap SR; STAMPEDE Investigators : Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes - 5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med 376: 641–651, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holcomb CN, Goss LE, Almehmi A, Grams JM, Corey BL: Bariatric surgery is associated with renal function improvement. Surg Endosc 32: 276–281, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang AR, Chen Y, Still C, Wood GC, Kirchner HL, Lewis M, Kramer H, Hartle JE, Carey D, Appel LJ, Grams ME: Bariatric surgery is associated with improvement in kidney outcomes. Kidney Int 90: 164–171, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Montgomery JR, Telem DA, Waits SA: Bariatric surgery for prospective living kidney donors with obesity? [published online ahead of print January 11, 2019]. Am J Transplant 10.1111/ajt.15260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Troxell ML, Houghton DC, Hawkey M, Batiuk TD, Bennett WM: Enteric oxalate nephropathy in the renal allograft: An underrecognized complication of bariatric surgery. Am J Transplant 13: 501–509, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andalib A, Aminian A, Khorgami Z, Navaneethan SD, Schauer PR, Brethauer SA: Safety analysis of primary bariatric surgery in patients on chronic dialysis. Surg Endosc 30: 2583–2591, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mozer AB, Pender JR 4th, Chapman WH, Sippey ME, Pories WJ, Spaniolas K: Bariatric surgery in patients with dialysis-dependent renal failure. Obes Surg 25: 2088–2092, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reames BN, Finks JF, Bacal D, Carlin AM, Dimick JB: Changes in bariatric surgery procedure use in Michigan, 2006-2013. JAMA 312: 959–961, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iezzoni LI, Daley J, Heeren T, Foley SM, Fisher ES, Duncan C, Hughes JS, Coffman GA: Identifying complications of care using administrative data. Med Care 32: 700–715, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM: Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care 36: 8–27, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Bahri S, Fakhry TK, Gonzalvo JP, Murr MM: Bariatric surgery as a bridge to renal transplantation in patients with end-stage renal disease. Obes Surg 27: 2951–2955, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jamal MH, Corcelles R, Daigle CR, Rogula T, Kroh M, Schauer PR, Brethauer SA: Safety and effectiveness of bariatric surgery in dialysis patients and kidney transplantation candidates. Surg Obes Relat Dis 11: 419–423, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tafti BA, Haghdoost M, Alvarez L, Curet M, Melcher ML: Recovery of renal function in a dialysis-dependent patient following gastric bypass surgery. Obes Surg 19: 1335–1339, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carandina S, Genser L, Bossi M, Montana L, Cortes A, Seman M, Danan M, Barrat C: Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy in kidney transplant candidates: A case series. Obes Surg 27: 2613–2618, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friedman AN, Wahed AS, Wang J, Courcoulas AP, Dakin G, Hinojosa MW, Kimmel PL, Mitchell JE, Pomp A, Pories WJ, Purnell JQ, le Roux C, Spaniolas K, Steffen KJ, Thirlby R, Wolfe B: Effect of bariatric surgery on CKD risk. J Am Soc Nephrol 29: 1289–1300, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bilha SC, Nistor I, Nedelcu A, Kanbay M, Scripcariu V, Timofte D, Siriopol D, Covic A: The effects of bariatric surgery on renal outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg 28: 3815–3833, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Doshi M, Streja E, Rhee CM, Park J, Ravel VA, Soohoo M, Moradi H, Lau WL, Mehrotra R, Kuttykrishnan S, Kovesdy CP, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Chen JL: Examining the robustness of the obesity paradox in maintenance hemodialysis patients: A marginal structural model analysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 31: 1310–1319, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park J, Ahmadi SF, Streja E, Molnar MZ, Flegal KM, Gillen D, Kovesdy CP, Kalantar-Zadeh K: Obesity paradox in end-stage kidney disease patients. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 56: 415–425, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Streja E, Molnar MZ, Kovesdy CP, Bunnapradist S, Jing J, Nissenson AR, Mucsi I, Danovitch GM, Kalantar-Zadeh K: Associations of pretransplant weight and muscle mass with mortality in renal transplant recipients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 1463–1473, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naderi N, Kleine CE, Park C, Hsiung JT, Soohoo M, Tantisattamo E, Streja E, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Moradi H: Obesity paradox in advanced kidney disease: From bedside to the bench. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 61: 168–181, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Streja E, Molnar MZ, Lukowsky LR, Krishnan M, Kovesdy CP, Greenland S: Mortality prediction by surrogates of body composition: An examination of the obesity paradox in hemodialysis patients using composite ranking score analysis. Am J Epidemiol 175: 793–803, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dai L, Mukai H, Lindholm B, Heimbürger O, Barany P, Stenvinkel P, Qureshi AR: Clinical global assessment of nutritional status as predictor of mortality in chronic kidney disease patients. PLoS One 12: e0186659, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kang SS, Chang JW, Park Y: Nutritional status predicts 10-year mortality in patients with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis. Nutrients 9: E399, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dierkes J, Dahl H, Lervaag Welland N, Sandnes K, Sæle K, Sekse I, Marti HP: High rates of central obesity and sarcopenia in CKD irrespective of renal replacement therapy - an observational cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrol 19: 259, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.