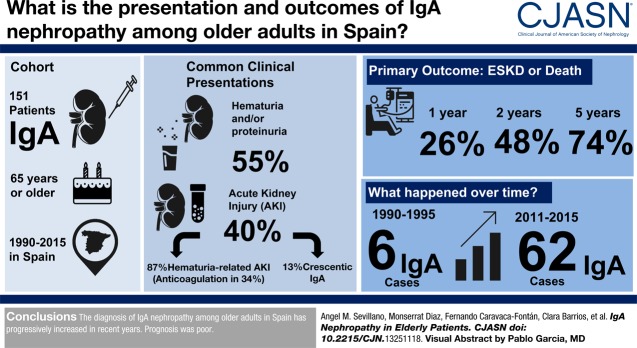

Visual Abstract

Keywords: IgA nephropathy; acute renal failure; hematuria; anticoagulation therapy; Glomerulonephritis, IGA; nephrotic syndrome; Hematuria; Retrospective Studies; risk factors; creatinine; aldosterone; Renin; Incidence; Angiotensins; Kidney Function Tests; Biopsy; Renal Replacement Therapy; Prognosis; Anticoagulants; Erythrocytes; acute kidney injury

Abstract

Background and objectives

Some studies suggest that the incidence of IgA nephropathy is increasing in older adults, but there is a lack of information about the epidemiology and behavior of the disease in that age group.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

In this retrospective multicentric study, we analyzed the incidence, forms of presentation, clinical and histologic characteristics, treatments received, and outcomes in a cohort of 151 patients ≥65 years old with biopsy-proven IgA nephropathy diagnosed between 1990 and 2015. The main outcome was a composite end point of kidney replacement therapy or death before kidney replacement therapy.

Results

We found a significant increase in the diagnosis of IgA nephropathy over time from six patients in 1990–1995 to 62 in 2011–2015 (P value for trend =0.03). After asymptomatic urinary abnormalities (84 patients; 55%), AKI was the most common form of presentation (61 patients; 40%). Within the latter, 53 (86%) patients presented with hematuria-related AKI (gross hematuria and tubular necrosis associated with erythrocyte casts as the most important lesions in kidney biopsy), and eight patients presented with crescentic IgA nephropathy. Six (4%) patients presented with nephrotic syndrome. Among hematuria-related AKI, 18 (34%) patients were receiving oral anticoagulants, and this proportion rose to 42% among the 34 patients older than 72 years old who presented with hematuria-related AKI. For the whole cohort, survival rates without the composite end point were 74%, 48%, and 26% at 1, 2, and 5 years, respectively. Age, serum creatinine at presentation, and the degree of interstitial fibrosis in kidney biopsy were risk factors significantly associated with the outcome, whereas treatment with renin-angiotensin-aldosterone blockers was associated with a lower risk. Immunosuppressive treatments were not significantly associated with the outcome.

Conclusions

The diagnosis of IgA nephropathy among older adults in Spain has progressively increased in recent years, and anticoagulant therapy may be partially responsible for this trend. Prognosis was poor.

Podcast

This article contains a podcast at https://www.asn-online.org/media/podcast/CJASN/2019_07_16_CJASNPodcast_19_08_.mp3

Introduction

IgA nephropathy has been traditionally considered to predominantly affect children and young adults (1,2). However, recent studies suggest that the incidence of IgA nephropathy is increasing among older adults (3–5). Compared with younger adults, older patients with IgA nephropathy exhibit higher rates of hypertension, poorer kidney function, and higher degrees of tubulointerstitial fibrosis at the time of kidney biopsy (6). Likewise, older patients with IgA nephropathy showed a faster decline of kidney function and greater mortality (7). However, most of the data in these studies were obtained from small series of patients, registries of patients with different forms of kidney diseases, or registries of kidney biopsies (8–10) without a detailed description of the patients’ characteristics.

In this study, we present the largest series so far reported of older adult patients with biopsy-proven IgA nephropathy. In an initiative from the Spanish Group for the Study of Glomerular Diseases (GLOSEN), information on 151 older patients with IgA nephropathy (65 years old or older) was collected, with a complete description of their baseline characteristics, forms of presentation, treatments received, and outcome.

Material and Methods

Patients

Twenty-three centers belonging to the GLOSEN participated in the study. The participating centers identified and included in the study all patients with a diagnosis of IgA nephropathy by kidney biopsy in the period 1990–2015 who were 65 years of age or older at the time of biopsy. Patients with systemic or hepatic diseases, IgA vasculitis, or any other type of secondary IgA nephropathy and patients with missing data were excluded. ANCAs were negative in all of the patients.

Information on 175 patients was collected following these criteria. Twenty-four patients were excluded because of missing data: lack of information about the type of clinical presentation in 14 patients and lack of information about kidney biopsy in ten patients. The remaining 151 patients were included in the study. All of them were regularly followed after the diagnosis of IgA nephropathy. The baseline and follow-up data were collected from medical records in all participating centers following a uniform protocol. Initiation of kidney replacement therapy (KRT) and the causes of death in patients who died before the start of KRT were carefully recorded.

Kidney Biopsy

Kidney biopsies were re-evaluated at every participating center, and lesions were scored according to the Oxford classification: mesangial score <0.5 or >0.5; segmental glomerulosclerosis absent or present; endocapillary hypercellularity absent or present; and tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis <25%, 26%–50%, and >50%. The presence of glomerular crescents was also evaluated and expressed as no crescents, crescents in <25% of glomeruli, and crescents in >25% of the glomeruli. The presence of red blood cell casts that occluded kidney tubules was expressed as the percentage of tubules that presented these lesions.

Classification

Patients were classified according to the clinical presentation at the time of kidney biopsy into the following categories: (1) asymptomatic urinary abnormalities, (2) AKI, and (3) nephrotic syndrome. Patients with AKI were subdivided in turn into the following categories: (2a) hematuria-related AKI and (2b) crescentic AKI.

Definitions

Asymptomatic urinary abnormalities were defined by the presence of non-nephrotic proteinuria and/or microscopic hematuria. AKI was defined according to the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes guidelines criteria for AKI diagnosis (11). Nephrotic syndrome was defined as proteinuria >3.5 g/24 h plus hypoalbuminemia. Hematuria-related AKI was defined by a clinical presentation characterized by gross hematuria or very intense nonvisible hematuria and the finding of tubular necrosis associated with erythrocyte casts as the most important lesions in kidney biopsy. Crescentic AKI was defined by the presence of crescents affecting 50% or more of the glomeruli (12).

Baseline was established as the time of kidney biopsy performance. Follow-up was defined as the interval between kidney biopsy and the last outpatient visit, death, or the onset KRT (maintenance dialysis or kidney transplantation). eGFR was calculated by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease abbreviated equation.

The recovery of kidney function after AKI was calculated as the percentage of serum creatinine decrease after 6 months of follow-up with respect to baseline serum creatinine. Overall survival was defined as the time from baseline to patient death. Kidney survival was defined as the time from baseline evaluation to requirement for KRT.

Outcomes

The main outcome was a composite end point of KRT or death before KRT.

Secondary outcomes (in patients presenting with AKI) were recovery ≥25% and ≥75% of baseline kidney function 6 months after AKI.

Control Cohort

We reviewed medical records of patients with biopsy-proven IgA nephropathy younger than 65 years old (n=135) at the Hospital 12 de Octubre in the period 1995–2015 to compare their baseline characteristics and outcomes with the cohort of older adult patients with IgA nephropathy.

Statistical Analyses

Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to analyze the main factors associated with the composite end point (death or KRT). The proportional hazard assumption was checked graphically (log-log Kaplan–Meier curves) for all covariates. Parametric and nonparametric tests were chosen as appropriate for descriptive comparisons of continuous variables, and chi-squared tests were used for categorical variables. Descriptive statistics are presented as means and SDs or medians and interquartile ranges for continuous variables and as absolute values and percentages for categorical variables. Statistical methods to estimate the cumulative incidence of KRT while accounting for the competing risk of dying before dialysis initiation and the propensity score matching analysis performed to compare outcomes of the study group with the control cohort of patients younger than 65 years old are described in Supplemental Appendix. P<0.05 was considered to be significant. Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Results

Forms of IgA Nephropathy Presentation and Changes over Time

As shown in Table 1, the most common form of presentation was asymptomatic urinary abnormalities (84 patients; 55%) followed by AKI (61 patients; 40%), whereas six (4%) patients presented with nephrotic syndrome. The most common type of AKI was hematuria-related AKI (53 patients; 86%), whereas the remaining patients with AKI corresponded to crescentic IgA nephropathy (eight patients; 13%).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and kidney biopsy results of older adults diagnosed with IgA nephropathy in 23 centers belonging to the Spanish Group for the Study of Glomerular Diseases

| All Patients, n=151 | Asymptomatic Urinary Abnormalities, n=84 | Hematuria-Related AKI, n=53 | Crescentic AKI, n=8 | Nephrotic Syndrome, n=6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men (%) | 116 (77) | 68 (81) | 37 (70) | 7 (87) | 4 (67) |

| Age, yr | 72±5 | 71±4a,b,c | 74±5 | 74±4 | 75±7 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 39 (26) | 24 (29) | 13 (25) | 2 (25) | 0 |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 142±20 | 141±15d | 140±22 | 155±27 | 149±37 |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 78±11 | 79±11 | 77±12 | 82±9 | 76±9 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dl | 3±2.3 | 2.1±1.4b,c | 4.3±2.8 | 4.7±2.1 | 1.4±0.6e |

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 32±22 | 39±22b,c | 19±16 | 15±10 | 54±26e |

| Proteinuria, g/d | 2.1 (1–4.1) | 2.1 (0.8–3.8) | 1.2 (0.8–3.5) | 7 (2.1–7.6) | 4.5 (3.5–6.3)f |

| Macroscopic hematuria, n (%) | 45 (30) | 0 (0)b | 41 (77) | 4 (50) | 0 (0)e,g |

| Duration of macroscopic hematuria, d | 11±33 | 0 | 27±47 | 2±3.2 | 0 |

| Microscopic hematuria, n (%) | 130 (85) | 65 (80)c | 53 (100) | 8 (100) | 6 (100)e |

| Oral anticoagulant therapy (%) | 30 (20) | 11 (13)c | 18 (34) | 0 | 1 (17) |

| KRT at presentation, n (%) | 14 (9) | 1 (1)b,c | 10 (20) | 3 (37) | 0 (0)e,g |

| M1 (%) | 100 (66) | 49 (58)h | 39 (74) | 6 (75) | 6 (100) |

| E1 (%) | 42 (28) | 17 (20) | 18 (34) | 3 (37) | 4 (40) |

| S1 (%) | 56 (37) | 35 (42) | 17 (32) | 2 (25) | 2 (25) |

| T1–T2 (%) | 77 (51) | 41 (49) | 28 (53) | 5 (62) | 3 (50) |

| ATN (%) | 59 (39) | 19 (23)i | 35 (66) | 3 (38) | 2 (33) |

| Glomeruli with crescents (%) | 0.21±0.4 | 2±6d | 3±7j | 53±5.8 | 7±10k |

KRT, kidney replacement therapy; M1, mesangial hypercellularity; E1, endocapillary hypercellularity; S1, segmental glomerulosclerosis; T1–T2, tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis >25%; ATN, acute tubular necrosis.

P=0.00 versus nephrotic syndrome.

P<0.001 versus crescentic AKI.

P<0.001 versus hematuria-related AKI.

P=0.02 versus crescentic AKI.

P<0.001 versus hematuria-related AKI.

P=0.02 versus hematuria-related AKI.

P=0.04 versus crescentic AKI.

P=0.04 versus nephrotic syndrome.

P=0.03 versus hematuria-related AKI.

P=0.00 versus crescentic AKI.

P<0.001 versus crescentic AKI.

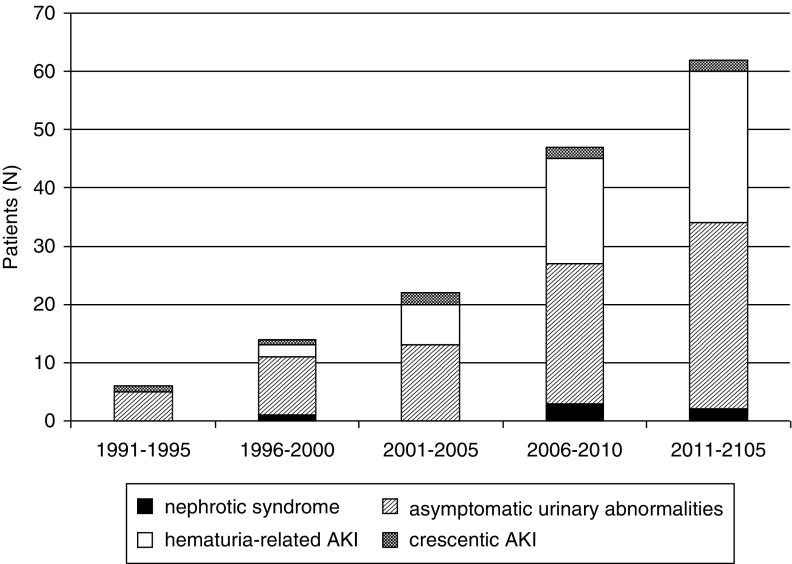

As shown in Figure 1, a clear increase in the diagnosis of IgA nephropathy among patients ≥65 years old was observed over time from six patients in the period 1990–1995 to 62 patients in the period 2011–2015 (P=0.03). A similar, although nonsignificant, increase was observed in the percentage of IgA nephropathy in patients ≥65 years old within the total number of biopsies with the diagnosis of IgA nephropathy (Supplemental Table 1). Within this global increase, the form of presentation that presented a more remarkable increase was hematuria-related AKI (0%, 14%, 33%, 38%, and 42% in the periods 1990–1995, 1996–2000, 2001–2005, 2006–2010, and 2011–2015, respectively), whereas other forms of presentation, such as asymptomatic urinary abnormalities (83%, 72%, 62%, 50%, and 52% in the periods 1990–1995, 1996–2000, 2001–2005, 2006–2010, and 2011–2015, respectively), crescentic AKI (17%, 7%, 5%, 6%, and 3% in the periods 1990–1995, 1996–2000, 2001–2005, 2006–2010, and 2011–2015, respectively) and nephrotic syndrome (0%, 7%, 0%, 6%, and 3% in the periods 1990–1995, 1996–2000, 2001–2005, 2006–2010, and 2011–2015, respectively), remained stable.

Figure 1.

Clinical presentation of biopsy-diagnosed IgA nephropathy among older adults over time.

Baseline Characteristics

Main baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Patients presenting with hematuria-related AKI, crescentic AKI, and nephrotic syndrome were significantly older than patients presenting with asymptomatic urinary abnormalities. As expected, kidney function was significantly worse in patients with hematuria-related AKI and patients with crescentic AKI than in the other groups. Proteinuria was significantly greater in patients with nephrotic syndrome, whereas the presence of visible macroscopic hematuria and the duration of hematuria were significantly higher in the hematuria-related AKI and crescentic AKI groups. The number of patients who were anticoagulated was significantly higher among hematuria-related AKI compared with the other groups. Significantly greater numbers of patients with hematuria-related AKI and patients with crescentic AKI required acute hemodialysis compared with the other groups. A majority of patients presenting with asymptomatic urinary abnormalities (84%) showed CKD stage 3 (44%), 4 (33%), or 5 (7%).

Compared with a control cohort of patients with biopsy-proven IgA nephropathy younger than 65 years old, a significantly higher proportion of patients >65 years old showed CKD stages 4 and 5, whereas a significantly lower number of patients >65 years old showed CKD stages 1 and 2 (Supplemental Table 2).

Kidney Biopsies

The presence of mesangial hypercellularity was significantly less common in patients presenting with asymptomatic urinary abnormalities compared with patients with nephrotic syndrome. Patients with crescentic AKI had a mean number of glomeruli with crescents (53±5.8%) significantly higher than those in the other groups. No other significant differences were found (Table 1).

Treatment and Outcomes

All Patients.

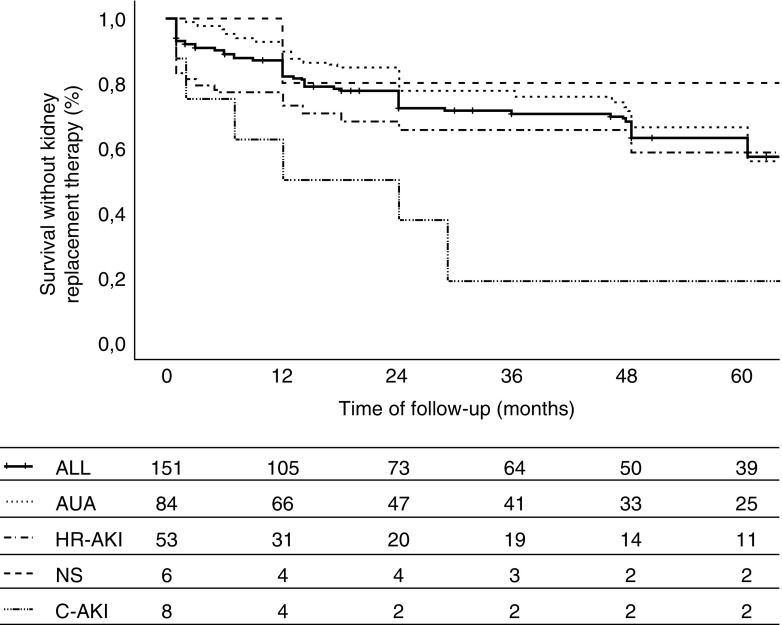

One hundred twenty-seven (84%) patients were treated with renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) blockers, and 70 (46%) patients received immunosuppressive treatments. As shown in Table 2, 40 (26%) patients needed KRT at the end of follow-up, and 29 (20%) patients died before the start of KRT, with no significant differences between groups. Figure 2 shows survival without the composite end point in the whole cohort and the different groups according to the type of clinical presentation. Patient survival and kidney survival are shown in Supplemental Figure 1. For the whole cohort, survival rates without combined end point (KRT or death before KRT) were 74%, 48%, and 26% at 1, 2, and 5 years, respectively. There were no differences in survival among the different groups according with the type of presentation except for patients with crescentic AKI, who presented significantly worse survival rates (50%, 25%, and 12.5% at 1, 2, and 5 years, respectively) (Figure 2). As shown in Supplemental Figure 2, there were no differences in survival according with the period of diagnosis.

Table 2.

Treatment and outcomes

| All Patients, n=151 | Asymptomatic Urinary Abnormalities, n=84 | Hematuria-Related AKI, n=53 | Crescentic AKI, n=8 | Nephrotic Syndrome, n=6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up, mo | 24 (12–66) | 36 (16–72) | 19 (4–60) | 18 (2–27) | 40 (10–120) |

| Treatment, n (%) | |||||

| RAAS blockade | 127 (84) | 73 (87) | 43 (81) | 6 (75) | 5 (83) |

| Immunosuppressive treatment | 70 (46) | 29 (35) | 32 (60) | 6 (75) | 3 (50) |

| Outcomes | |||||

| Composite outcome, n (%) | 69 (46) | 38 (45) | 23 (53) | 6 (75) | 2 (33) |

| KRT, n (%) | 40 (26) | 24 (29) | 13 (25) | 3 (37) | 0 (0) |

| Death before KRT, n (%) | 29 (20) | 14 (17) | 10 (19) | 3 (37) | 2 (33) |

| Incidence rate of composite outcome per 100 patient-yr (95% CI) | 12 (9 to 14) | 11 (8 to 14) | 14 (10 to 21) | 20 (7 to 55) | 0 |

RAAS, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system; KRT, kidney replacement therapy; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Figure 2.

Survival without kidney replacement therapy according to clinical presentation. Crescentic AKI (C-AKI) versus asymptomatic urinary abnormality (AUA): P=0.03. Composite outcome definition: kidney replacement therapy or death before kidney replacement therapy. HR-AKI, hematuria-related AKI; NS, nephrotic syndrome.

By Cox proportional hazards regression model (Table 3), age and serum creatinine at presentation as well as the degree of interstitial fibrosis in kidney biopsy were the only factors significantly associated with the combined end point (KRT or death before KRT), whereas treatment with RAAS blockers was associated with a significantly better outcome. Over a period of 2 years, treatment with RAAS blockade lowered the chance of reaching the composite outcome by 46% compared with patients not treated with that therapy (40% versus 75%, respectively). However, no association between immunosuppressive treatment and better outcomes was found.

Table 3.

Associations of clinical characteristics, kidney biopsy results, and treatments with the composite outcome of kidney replacement therapy or death before kidney replacement therapy

| Variable (at Presentation) | No. of Events/No. at Risk (n/N) | Unadjusted Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | Adjusted Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr (per 1 yr older) | 1.05 (0.99 to 1.11) | 0.10 | 1.06 (1.01 to 1.10) | 0.02a | |

| Men | 53/116 | 1.62 (0.84 to 3.13) | 0.15 | ||

| Smoking | 32/65 | 1.13 (0.65 to 1.96) | 0.67 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 17/39 | 1.21 (0.64 to 2.28) | 0.56 | ||

| Oral anticoagulant therapy | 12/30 | 0.78 (0.36 to 1.67) | 0.52 | ||

| Charlson comorbidity index (per 1-U increment) | 1.01 (0.84 to 1.22) | 0.88 | |||

| Systolic BP, mm Hg (per 10-mm Hg increment) | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.02) | 0.94 | |||

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg (per 10-mm Hg increment) | 0.98 (0.95 to 1.01) | 0.11 | |||

| Serum creatinine (per 1-mg/dl increment) | 1.19 (1.07 to 1.33) | 0.00 | 1.20 (1.10 to 1.31) | <0.001a | |

| Serum albumin, g/dl (per 1-g/dl increment) | 0.76 (0.47 to 1.23) | 0.27 | |||

| Proteinuria, g/24 h (per 1-g/24 h increment) | 1.04 (0.91 to 1.20) | 0.56 | |||

| M1 | 46/100 | 1.35 (0.74 to 2.45) | 0.33 | ||

| E1 | 21/42 | 0.78 (0.41 to 1.49) | 0.44 | ||

| S1 | 28/56 | 1.17 (0.67 to 2.06) | 0.59 | ||

| T1–T2 | 44/77 | 1.70 (1.09 to 2.65) | 0.02 | 1.94 (1.33 to 2.82) | <0.001a |

| Crescents >25% | 16/32 | 1.45 (0.70 to 3.03) | 0.32 | ||

| RAAS blockade | 51/127 | 0.18 (0.09 to 0.36) | <0.001 | 0.21 (0.12 to 0.39) | <0.001a |

| Immunosuppressive treatment | 32/70 | 1.22 (0.66 to 2.26) | 0.52 |

The number of events (composite outcome) in the whole cohort was of 69. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; M1, mesangial hypercellularity; E1, endocapillary hypercellularity; S1, segmental glomerulosclerosis; T1–T2, tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis >25%; RAAS, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system.

These rows denote statistical significances.

A separate analysis of the main determinants of mortality before KRT and KRT initiation adjusted for competing risk of death is shown in Supplemental Table 3. Charlson comorbidity index was the main determinant of death before KRT.

Study patients were further compared with a propensity-matched cohort of patients younger than 65 years old with IgA nephropathy and a similar degree of baseline kidney function and interstitial fibrosis in kidney biopsy (Supplemental Table 4). Survival without the composite end point was significantly worse among patients with IgA nephropathy >65 years old compared with younger patients (Supplemental Figure 3).

Patients Presenting with Asymptomatic Urinary Abnormalities.

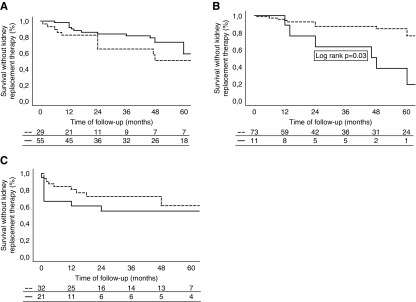

Twenty-four (29%) patients presenting with asymptomatic urinary abnormalities needed KRT, and 14 (17%) patients died before KRT at the end of follow-up. However, 14 (9%) patients were lost to follow-up. Twenty-nine (35%) patients received immunosuppressive treatments (corticosteroids alone in 21 patients, corticosteroids plus mycophenolate mofetil in seven patients, and mycophenolate mofetil alone in one patient). As shown in Supplemental Table 5, there were no significant differences at baseline between patients who did receive immunosuppressive treatments and those who did not, with the exception of the amount of proteinuria and the number of patients receiving RAAS blockers, which were significantly higher among patients given immunosuppressive treatments. There were no significant differences in the number of patients reaching the combined end point (KRT or death before KRT) according to immunosuppressive therapy (Figure 3A, Supplemental Table 5). As shown in Figure 3B, survival was significantly higher among those patients treated with RAAS blockers compared with those patients who did not receive this treatment.

Figure 3.

Survival without kidney replacement therapy by treatment received after diagnosis. (A) Patients with asymptomatic urinary symptoms according to immunosuppressive treatment. Dotted line indicates immunosuppressive therapy. Solid line indicates no immunosuppressive therapy. (B) Patients with asymptomatic urinary symptoms according to renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors. Dotted line indicates renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors. Solid line indicates no renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors (C) Patients with hematuria-related AKI according to immunosuppressive treatment. Dotted line indicates immunosuppressive therapy. Solid line indicates no immunosuppressive therapy.

Patients Presenting with Hematuria-Related AKI.

Fifty-three patients presented with hematuria-related AKI, 18 of whom (34%) were receiving oral anticoagulants. Compared with patients <72 years old, the number of patients presenting with macroscopic hematuria and receiving anticoagulant therapy was significantly higher among patients older than 72 years old (Supplemental Table 6). There were no significant differences at baseline between patients treated and not treated with anticoagulants, although the number of patients who received immunosuppressive treatments was significantly higher among patients treated with anticoagulants (Supplemental Table 7).

Anticoagulation was discontinued in four of 18 (22%) patients. No differences were found between these patients and the remaining 14 in whom anticoagulant treatment was maintained regarding kidney function recovery or patient and kidney survival. Thirty-two (60%) patients were treated with immunosuppressive treatment: corticosteroids alone in 21 patients, corticosteroids associated with cyclophosphamide in six patients, corticosteroids associated with mycophenolate mofetil in four patients, and corticosteroids associated with azathioprine in one patient. As shown in Supplemental Table 7, there was a nonsignificant trend for a higher number of patients recovering >25% of kidney function and a lower number requiring KRT among those who received immunosuppressive treatments, although the number of patients with >75% kidney function recovery was similar independent of treatment. There was also a nonsignificant trend for a lower number of patients reaching KRT among those who received immunosuppressive treatments (Figure 3C, Supplemental Table 7).

Patients Presenting with Crescentic AKI.

Of the eight patients presenting with crescentic AKI, six (75%) received immunosuppressive treatments (corticosteroids in four patients and corticosteroids plus cyclophosphamide in two patients) As shown in Table 2, three patients required KRT at the end of follow-up, and three died before KRT.

Patients Presenting with Nephrotic Syndrome.

Six patients presented with nephrotic syndrome, which was accompanied by microscopic hematuria in all of them. Three patients were treated with corticosteroids, and complete remission of nephrotic syndrome was achieved in two patients. No patient required KRT, and two patients died 12 and 118 months after presentation (Table 2).

Discussion

Our study shows an increasing number of IgA nephropathy in patients older than 65 years old diagnosed over the last 24 years. The causes of this epidemiologic change are not clear. It could be related to a change in the policy of kidney biopsy indications, but it seems unlikely considering the diversity of centers that participated in the study. Another explanation may be related to the increase in life expectancy and the progressive aging of the Spanish population, a feature shared by most European countries. However, it is important to note that almost one half of our patients presented with symptomatic and aggressive forms of the disease, such as AKI, nephrotic syndrome, and advanced CKD. Therefore, it is possible that the increase in these aggressive presentations resulted in a greater indication of kidney biopsy in the last years and consequently, a greater number of cases of IgA nephropathy diagnosed among older adult patients.

One of the most salient findings in our study is the high and increasing incidence of AKI as the first manifestation of IgA nephropathy. In the majority of patients presenting with AKI (53 of 61 patients; 86%), the acute impairment of kidney function coincided with an outbreak of gross hematuria or a very intense nonvisible hematuria, and the presence of numerous erythrocyte casts within renal tubules with associated tubular necrosis was the most prominent finding in kidney biopsy. The cause of this increase in hematuria-related AKI is not clear, but our data suggest that the high prevalence of anticoagulant treatments among the older population can contribute, at least partially, to this epidemiologic change. Thus, 18 (34%) of the 53 patients who presented with hematuria-related AKI were receiving anticoagulant treatments, and this proportion rose to 42% among patients older than 72 years old.

Hematuria-related AKI has been reported in patients treated with warfarin (warfarin-related nephropathy) (13), and a similar complication has been described with other types of oral anticoagulants (14). It is plausible to think that anticoagulant treatments in patients with IgA nephropathy, an entity in which persistent microhematuria and gross hematuria episodes are characteristic clinical manifestations, may exacerbate the predisposition of older patients with IgA nephropathy to episodes of gross hematuria–related AKI as our study shows. Notably, no cases of warfarin-related nephropathy have been reported in patients with glomerular diseases other than IgA nephropathy. However, some studies have shown that an important number of otherwise healthy subjects may have glomerular deposits of IgA without clinical manifestations (15), and it is possible that anticoagulation may precipitate an episode of severe glomerular hematuria in these previously asymptomatic patients. However, more studies are needed to investigate this hypothesis.

Glomerular hemorrhage in Bowman’s space and numerous occlusive erythrocyte casts in tubules with signs of acute tubular injury are found in both patients with anticoagulant-related nephropathy and patients with hematuria-related AKI of IgA nephropathy (13,14,16,17), making the differentiation between the entities very difficult. Some patient reports of patients with IgA nephropathy and hematuria-related AKI precipitated by anticoagulant treatment have been described in recent years (18), but our study is the first to highlight the real incidence of this complication in a large cohort of older patients with IgA nephropathy.

Previous studies have reported that chronic lesions in kidney biopsy are more frequent and that the decline in kidney function is faster in older patients with IgA nephropathy than in younger ones (4,6). However, most of these data were extracted from registry studies or small series of patients. Our study confirms in a large cohort of patients the poor prognosis of IgA nephropathy in older adults. After 2 years of follow-up, survival without KRT (maintenance dialysis or kidney transplantation) or death before KRT was 48%, and at 5 years, this proportion had decreased to 26%.

The poor outcome of older patients with IgA nephropathy may be related to the advanced CKD found in most of them at presentation, with severe chronic lesions in the kidney biopsy (19,20). In fact, the level of serum creatinine at baseline and the degree of interstitial fibrosis were, along with age at presentation, risk factors associated with the probability of reaching the combined end point of KRT or death before KRT. Those patients presenting with hematuria-related AKI also had poor prognosis, with only 36% and 21% survival without KRT or death before KRT after 2 and 5 years, respectively.

Our group had previously described a greater susceptibility of older patients with IgA nephropathy to the deleterious consequences of hematuria-related AKI, with a significant proportion of patients not recovering their previous kidney function after the cessation of gross hematuria (18,19). To explain these different outcomes, it could be hypothesized that the senile kidney parenchyma is more sensitive to the tubular damage induced by the hemoglobin released by erythrocytes in the tubular lumen (17,20-22). However, it has been recently shown that hemoglobin uptake by podocytes causes intense oxidative stress and apoptosis, leading to podocyte loss (23).

There is a general consensus about the beneficial effect of RAAS blockers in patients with significant proteinuria and hypertension (24,25). In line with this recommendation, we found an association between RAAS blockers and a better outcome in our cohort in both univariate and multivariable analyses. However, despite the fact that a large majority of our patients were treated with RAAS blockers, the overall prognosis was poor.

The role of immunosuppressive treatment in IgA nephropathy has been questioned by the results of recent studies (26,27) showing that the severity of their side effects may overcome their marginal benefits on kidney function. Nevertheless, information about the influence of immunosuppressive treatments on the outcomes of older patients with IgA nephropathy is remarkably scarce, and very few older adults have been included in prospective therapeutic trials. In our study, immunosuppression was not associated with a better outcome in those patients who presented with asymptomatic urinary abnormalities, whereas there was a nonsignificant trend for a higher rate of baseline kidney function recovery and a lower rate of KRT requirements among those patients presenting with hematuria-related AKI who received immunosuppressive treatments. Nevertheless, prospective controlled trials to determine the possible efficacy of immunosuppressive or other new treatments in older patients with IgA nephropathy are needed.

Our study presents important limitations, mainly related to its retrospective design and the lack of uniform protocols for kidney biopsy indication. The lack of common protocols for the use of immunosuppressive treatments, the variability in the doses and duration of these treatments, and the small number of patients in some of the subgroups hamper the assessment of the influence of immunosuppression. However, the study presents evident strengths, including the largest series of older patients with biopsy-proven IgA nephropathy so far collected; an overview of the changes in the types of clinical presentation in the last 25 years; and a detailed description of the clinical, analytic, and histologic characteristics at presentation. Furthermore, all of the patients were regularly and carefully monitored during follow-up, and the study provides a detailed report of final outcomes and the influence of the treatments received by the patients.

In summary, our study shows that the diagnosis of IgA nephropathy in older adults has progressively increased in the last 25 years, especially at the expense of patients with hematuria-related AKI. Our data suggest that anticoagulant therapy may be, at least partially, responsible for this trend. Our study also illustrates the dismal prognosis of IgA nephropathy in older adults, with survival rates without KRT of 48% and 26% at 2 and 5 years of follow-up, respectively. RAAS blockade was associated with a protective influence on kidney survival, whereas immunosuppressive treatments were not associated with a beneficial influence on patients presenting with asymptomatic urinary abnormalities. The almost significant trend that we found regarding a protective role of immunosuppressive treatments on patients with hematuria-related AKI should be explored by means of carefully designed prospective studies. Overall, considering the increasing diagnosis and the poor prognosis of IgA nephropathy in older adults shown by our study, investigations about new therapeutic alternatives for this type of patients are urgently needed.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

Dr. Moreno was supported by grants from Programa Miguel Servet (CP10/00479, CPII16/00017, PI13/00802 and PI14/00883), the Spanish Society of Nephrology, and Fundación Renal Iñigo Alvarez de Toledo. Dr. Praga was supported by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III and by grants from REDinREN (RD012/0021) and Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias (ISCIII/FEDER; grants 13/02502, ICI14/00350, and 16/01685).

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.13251118/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Appendix. Statistical analysis.

Supplemental Figure 1. Survival without kidney replacement therapy, death, or the composite end point (RRT or death before RRT) in the whole cohort of patients.

Supplemental Figure 2. Survival without composite end point (RRT or death before RRT) according to the period of diagnostic.

Supplemental Figure 3. Survival without composite end point of patients of our study cohort (>65 years old) and the 12 de Octubre cohort (<65 years old) after a propensity score matching.

Supplemental Table 1. Number of kidney biopsies, number of them with the diagnosis of IgA nephropathy, and number of IgA nephropathy diagnoses in patients >65 years old in each period of time.

Supplemental Table 2. CKD stages at diagnosis in the study cohort of patients >65 years old and a control cohort of patients with IgA nephropathy younger than 65 years old.

Supplemental Table 3. Cox proportional hazard regression model for association between covariates and mortality before kidney replacement therapy or kidney replacement therapy initiation adjusted for competing risk of death (subdistribution hazards model of Fine and Gray).

Supplemental Table 4. Baseline characteristics and outcome of our study cohort (>65 years old) and the 12 de Octubre cohort (<65 years old) after a propensity score matching.

Supplemental Table 5. Patients presenting with asymptomatic urinary abnormalities treated and not treated with immunosuppressive drugs.

Supplemental Table 6. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of patients ≥72 and <72 years old.

Supplemental Table 7. Patients presenting with hematuria-related AKI treated and not treated with immunosuppressive drugs.

Supplemental Table 8. Cause of death in patients who died before the start of kidney replacement therapy.

References

- 1.Floege J, Feehally J: Treatment of IgA nephropathy and Henoch-Schönlein nephritis. Nat Rev Nephrol 9: 320–327, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lai KN, Tang SCW, Schena FP, Novak J, Tomino Y, Fogo AB, Glassock RJ: IgA nephropathy. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2: 16001, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gutiérrez E, Praga M, Rivera F, Sevillano A, Yuste C, Goicoechea M, López-Gómez JM; all members of the Spanish Registry of Glomerulonephritis : Changes in the clinical presentation of immunoglobulin A nephropathy: Data from the Spanish registry of glomerulonephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 33: 472–477, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duan ZY, Cai GY, Chen YZ, Liang S, Liu SW, Wu J, Qiu Q, Lin SP, Zhang XG, Chen XM: Aging promotes progression of IgA nephropathy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Nephrol 38: 241–252, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sumnu A, Gursu M, Ozturk S: Primary glomerular diseases in the elderly. World J Nephrol 4: 263–270, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frimat L, Hestin D, Aymard B, Mayeux D, Renoult E, Kessler M: IgA nephropathy in patients over 50 years of age: A multicentre, prospective study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 11: 1043–1047, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheungpasitporn W, Nasr SH, Thongprayoon C, Mao MA, Qian Q: Primary IgA nephropathy in elderly patients. Nephrology (Carlton) 20: 419–425, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abrass CK: Glomerulonephritis in the elderly. Am J Nephrol 5: 409–418, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rivera F, López-Gómez JM, Pérez-García R; Spsnish Registry of Glomerulonephritis : Frequency of renal pathology in Spain 1994-1999. Nephrol Dial Transplant 17: 1594–1602, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yokoyama H, Sugiyama H, Sato H, Taguchi T, Nagata M, Matsuo S, Makino H, Watanabe T, Saito T, Kiyohara Y, Nishi S, Iida H, Morozumi K, Fukatsu A, Sasaki T, Tsuruya K, Kohda Y, Higuchi M, Kiyomoto H, Goto S, Hattori M, Hataya H, Kagami S, Yoshikawa N, Fukasawa Y, Ueda Y, Kitamura H, Shimizu A, Oka K, Nakagawa N, Ito T, Uchida S, Furuichi K, Nakaya I, Umemura S, Hiromura K, Yoshimura M, Hirawa N, Shigematsu T, Fukagawa M, Hiramatsu M, Terada Y, Uemura O, Kawata T, Matsunaga A, Kuroki A, Mori Y, Mitsuiki K, Yoshida H; Committee for the Standardization of Renal Pathological Diagnosis and for Renal Biopsy and Disease Registry of the Japanese Society of Nephrology, and the Progressive Renal Disease Research of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan : Renal disease in the elderly and the very elderly Japanese: Analysis of the Japan Renal Biopsy Registry (J-RBR). Clin Exp Nephrol 16: 903–920, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) : KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury.Kidney Int 3: [suppl 1]: S8–S12, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Glomerulonephritis Work Group : KDIGO clinical practice guideline for glomerulonephritis. Immunoglobulin a nephropathy. Kidney Int 3: [suppl 2]: S139–S274, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brodsky SV, Satoskar A, Chen J, Nadasdy G, Eagen JW, Hamirani M, Hebert L, Calomeni E, Nadasdy T: Acute kidney injury during warfarin therapy associated with obstructive tubular red blood cell casts: A report of 9 cases. Am J Kidney Dis 54: 1121–1126, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ryan M, Ware K, Qamri Z, Satoskar A, Wu H, Nadasdy G, Rovin B, Hebert L, Nadasdy T, Brodsky SV: Warfarin-related nephropathy is the tip of the iceberg: Direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran induces glomerular hemorrhage with acute kidney injury in rats. Nephrol Dial Transplant 29: 2228–2234, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suzuki K, Honda K, Tanabe K, Toma H, Nihei H, Yamaguchi Y: Incidence of latent mesangial IgA deposition in renal allograft donors in Japan. Kidney Int 63: 2286–2294, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gutiérrez E, González E, Hernández E, Morales E, Martínez MA, Usera G, Praga M: Factors that determine an incomplete recovery of renal function in macrohematuria-induced acute renal failure of IgA nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2: 51–57, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moreno JA, Martín-Cleary C, Gutiérrez E, Rubio-Navarro A, Ortiz A, Praga M, Egido J: Haematuria: The forgotten CKD factor? Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 28–34, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Escoli R, Santos P, Andrade S, Carvalho F: Dabigatran-related nephropathy in a patient with undiagnosed IgA nephropathy. Case Rep Nephrol 2015: 298261, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cattran DC, Coppo R, Cook HT, Feehally J, Roberts IS, Troyanov S, Alpers CE, Amore A, Barratt J, Berthoux F, Bonsib S, Bruijn JA, D’Agati V, D’Amico G, Emancipator S, Emma F, Ferrario F, Fervenza FC, Florquin S, Fogo A, Geddes CC, Groene HJ, Haas M, Herzenberg AM, Hill PA, Hogg RJ, Hsu SI, Jennette JC, Joh K, Julian BA, Kawamura T, Lai FM, Leung CB, Li LS, Li PK, Liu ZH, Mackinnon B, Mezzano S, Schena FP, Tomino Y, Walker PD, Wang H, Weening JJ, Yoshikawa N, Zhang H; Working Group of the International IgA Nephropathy Network and the Renal Pathology Society : The Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy: Rationale, clinicopathological correlations, and classification. Kidney Int 76: 534–545, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.D’Amico G, Ferrario F, Colasanti G, Ragni A, Bestetti Bosisio M: IgA-mesangial nephropathy (Berger’s disease) with rapid decline in renal function. Clin Nephrol 16: 251–257, 1981 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yuste C, Rubio-Navarro A, Barraca D, Aragoncillo I, Vega A, Abad S, Santos A, Macias N, Mahillo I, Gutiérrez E, Praga M, Egido J, López-Gómez JM, Moreno JA: Haematuria increases progression of advanced proteinuric kidney disease. PLoS One 10: e0128575, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moreno JA, Yuste C, Gutiérrez E, Sevillano ÁM, Rubio-Navarro A, Amaro-Villalobos JM, Praga M, Egido J: Haematuria as a risk factor for chronic kidney disease progression in glomerular diseases: A review. Pediatr Nephrol 31: 523–533, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rubio-Navarro A, Sanchez-Niño MD, Guerrero-Hue M, García-Caballero C, Gutiérrez E, Yuste C, Sevillano Á, Praga M, Egea J, Román E, Cannata P, Ortega R, Cortegano I, de Andrés B, Gaspar ML, Cadenas S, Ortiz A, Egido J, Moreno JA: Podocytes are new cellular targets of haemoglobin-mediated renal damage. J Pathol 244: 296–310, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Praga M, Gutiérrez E, González E, Morales E, Hernández E: Treatment of IgA nephropathy with ACE inhibitors: A randomized and controlled trial. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 1578–1583, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coppo R, Peruzzi L, Amore A, Piccoli A, Cochat P, Stone R, Kirschstein M, Linné T: IgACE: A placebo-controlled, randomized trial of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in children and young people with IgA nephropathy and moderate proteinuria. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 1880–1888, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rauen T, Eitner F, Fitzner C, Sommerer C, Zeier M, Otte B, Panzer U, Peters H, Benck U, Mertens PR, Kuhlmann U, Witzke O, Gross O, Vielhauer V, Mann JF, Hilgers RD, Floege J; STOP-IgAN Investigators : Intensive supportive care plus immunosuppression in IgA nephropathy. N Engl J Med 373: 2225–2236, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lv J, Zhang H, Wong MG, Jardine MJ, Hladunewich M, Jha V, Monaghan H, Zhao M, Barbour S, Reich H, Cattran D, Glassock R, Levin A, Wheeler D, Woodward M, Billot L, Chan TM, Liu ZH, Johnson DW, Cass A, Feehally J, Floege J, Remuzzi G, Wu Y, Agarwal R, Wang HY, Perkovic V; TESTING Study Group : Effect of oral methylprednisolone on clinical outcomes in patients with IgA nephropathy: The TESTING randomized clinical trial. JAMA 318: 432–442, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.