Abstract.

We report on a pathway for Gabor domain optical coherence microscopy (GD-OCM)-based metrology to assess the donor’s corneal endothelial layers ex vivo. Six corneas from the Lions Eye Bank at Albany and Rochester were imaged with GD-OCM. The raw 3-D images of the curved corneas were flattened using custom software to enhance the 2-D visualization of endothelial cells (ECs); then the ECs within a circle of -diameter were analyzed using a custom corner method and a cell counting plugin in ImageJ. The EC number, EC area, endothelial cell density (ECD), and polymegethism (CV) were quantified in five different locations for each cornea. The robustness of the method (defined as the repeatability of measurement together with interoperator variability) was evaluated by independently repeating the entire ECD measurement procedure six times by three different examiners. The results from the six corneas show that the current modality reproduces the ECDs with a standard deviation of 2.3% of the mean ECD in every location, whereas the mean ECD across five locations varies by 5.1%. The resolution and imaging area provided through the use of GD-OCM may help to ultimately better assess the quality of donor corneas in transplantation.

Keywords: optical coherence tomography, Gabor domain optical coherence microscopy, cellular imaging, noninvasive imaging, corneal imaging, image processing

1. Introduction

The corneal endothelium is the innermost layer of the cornea, which serves as a leaky barrier to aqueous humor flow that supplies the stroma with necessary nutrients. Corneal transparency is maintained by healthy endothelial cells (ECs) that contain fluid pumps that control the level of stromal hydration.1 A malfunction in the deturgescence state of the cornea can lead to corneal edema and eventually to blindness. From penetrating keratoplasty, first developed in 1905, to endothelial keratoplasty,2,3 corneal transplantation remains the main method of treatment for endothelial dysfunction and failure.4 Endothelial cell density (ECD) is a key determinant in tissue selection/placement and graft survival.

Noncontact specular microscopy (SM) is a standard imaging apparatus used in eye banks to assess the donor corneal endothelium. Although the imaging modality is user-friendly, cost-effective, and fast, most SMs have a small field of view5 (e.g., Konan EB-10 of ),6 which introduces sampling error in ECD evaluation.7 Furthermore, given the curvature of the cornea, SM images often provide a partial view of ECs, which further limits the area of interest for EC analysis5 and a mixture of proximate layers near the endothelium. The latter issue has been mitigated using the confocal principle, found in various in vivo confocal microscopy (IVCM) such as tandem scanning confocal microscopy,8,9 slit scanning confocal microscopy,10,11 and laser scanning confocal microscopy.12 More thorough explanations of the utilized techniques and the limitations of various IVCMs for imaging the cornea were reviewed in previous articles,13,14 and IVCMs showed an ECD analysis comparable to SM.15,16 Optical coherence tomography (OCT) has been actively adopted in various ophthalmic applications17 to visualize cross-sectional views of the sample and is used at eye banks for corneal pachymetry.18 For the histological study of a cornea (e.g., endothelial cells), an embodiment of OCT with a high numerical aperture (NA) microscope objective called optical coherence microscopy (OCM)19 is gaining attention from researchers for its improved spatial resolution relative to that of IVCM. OCM has steadily evolved into two platforms, depending on the type of illumination and operating principles: full-field OCM (FF-OCM)20–22 and Fourier-domain OCM (FD-OCM).23–28 FF-OCM is a time-domain OCT, which provides direct access to en face images of the tissue. The volumetric image is obtained by scanning in depth and stacking all en face images from different depths. Cross-sectional images can be extracted from the volumetric image. On the other hand, FD-OCM is a spectral-domain OCT with high-spatial resolution comparable to that of confocal microscopy, which gives direct access to cross-sectional images. En face images can be extracted by restacking the volumetric image. Because of their high-spatial resolution typically obtained with an increase in NA, OCM methods have limited imaging depth that is set by the depth of focus (DOF) of the microscope objective. The DOF is estimated at tens of micrometers (i.e., 40 to depending on the criterion for contrast considered); the curvature of the cornea creates a depth which the ECs lie within . So, in principle, if focused carefully, one could image all ECs across the curved cornea within two zones of the Gabor domain optical coherence microscopy (GD-OCM) using the strictest criterion for DOF. Two or three zones allow the zones to be separated by less than of the DOF of GD-OCM for achieving the highest quality in-focus imaging throughout the endothelium. All imaging was conducted with at least two and up to three zones around the ECs locations for the full field of view of the GD-OCM.

GD-OCM,29 which is a variation of FD-OCM, was introduced to overcome the DOF limitation. The microscope objective in GD-OCM is custom designed and integrates a liquid lens to effectively extend the depth of imaging beyond the instantaneous DOF of the microscope by scanning the focus of light through depth with an invariant lateral resolution30,31 and acquiring and fusing multiple DOF-limited volumes at different depths for creating an image with high contrast across the extended depth. Fusion of multiple imaging volumes at different depths32 and high-speed parallel processing33 provides a 3-D volumetric GD-OCM image with an uncompromised resolution. GD-OCM has successfully revealed the morphologies of human corneas34–36 with a isotropic resolution over a millimeter range imaging depth.

In this pilot study, a pathway to assess corneal endothelial cells from ex vivo donor corneas using GD-OCM was demonstrated on six corneas. To assess the variability in ECD across the location of the cornea, the endothelial layer was evaluated at five locations, namely, nasal, temporal, central, superior, and inferior with respect to the apex of the mounted cornea. Four statistical metrics of the corneal endothelium—ECN, ECA, ECD, and CV—were quantified at the five locations. From the image acquisition to cell analysis, the entire process was repeated six times at each location to evaluate the variability in the estimation of ECD.

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol and Sample Preparation

The donor corneas were received from Lions Eye Bank at Albany and Rochester, New York. Corneas were preserved upon recovery in Optisol-GS medium (Bausch and Lomb, Rochester) inside a storage container for corneas and were delivered to the University of Rochester inside a polystyrene box filled with packs of ice. The donor age ranged from 32 to 66 years. Time from death to tissue preservation was about 5 to 22 h. Donor tissue details are summarized in Table 1. Prior to imaging, corneas were stored at room temperature for 1 h to improve the image quality.37 As a reference, a conventional noncontact specular microscope, Kerato Analyzer (EKA-98, Konan Medical Inc., Japan) was first employed to image the central location of the corneal endothelium through the storage container. A USAF calibration target (R1L1S1P, THORLABS) was used to convert the number of pixels into the physical dimension of endothelial cells area. Corneas were then removed from the storage container and mounted onto a corneal artificial chamber (Moria, Inc., France) equipped with a microfluidic system that was used to control the physiological pressure inside the anterior chamber. The latter was perfused using Optisol to avoid air bubbles inside the anterior chamber.

Table 1.

Information on the donor corneas.

| Cornea ID | Age | Gender | Cause of death | Death to preservation time (h) | Death to imaging time (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 32 | Male | Motocycle accident | 22 | 28 |

| 2 | 59 | Female | Chest bleed | 9 | 95 |

| 3 | 59 | ″ | ″ | ″ | 119 |

| 4 | 60 | Male | Nontraumatic intracranial hemorrhage | 14 | 20 |

| 5 | 66 | Female | Acute respiratory failure | 5 | 12 |

| 6 | 66 | ″ | ″ | ″ | 54 |

2.2. Imaging with GD-OCM

The light source of GD-OCM had a central wavelength of 840 nm and a bandwidth of 100 nm. The FWHM of the axial PSF in air was up to 1.2-mm-depth, equivalent to in the cornea. At least lateral separation could be resolved.36 The NA of the GD-OCM microscope objective was 0.2 and the theoretical DOF (for ) was . The MTF-driven experimental DOF assuming 20% contrast at was in air.31

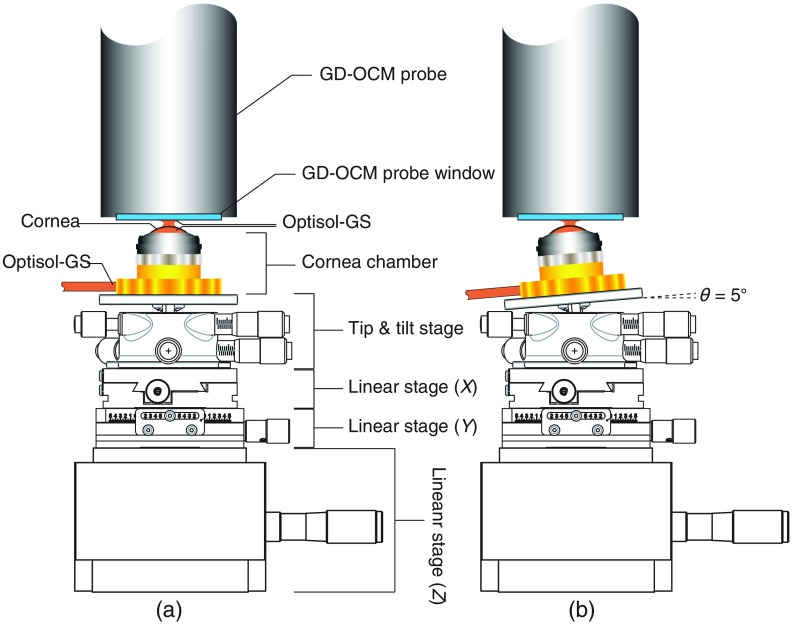

The assembly was secured on the deck of a tip, tilt and rotation stage (TTR001, THORLABS) mounted on two horizontal - and -linear stages (DTS25, THORLABS) and a vertical -linear stage (MVN80, Newport) as shown in Fig. 1(a). The positioning of the sample relative to the GD-OCM probe was monitored using 2-D scanning in and directions. The air gap of between the GD-OCM probe’s window and the cornea was filled with Optisol for index matching, thus reducing high-reflection imaging artifacts resulting from the corneal anterior surface. For imaging the four near-peripheral endothelial layer (superior, inferior, nasal, and temporal) locations, the cornea platform was tilted by 5 deg (up, down, left, and right, respectively) using the tip, tilt and rotation stage as shown in Fig. 1(b). In all cases, the centering of the cornea on the probe was performed using the 2-D scanning in and directions.

Fig. 1.

Illustration of the setup for GD-OCM imaging of the corneal endothelium layer. The configurations for (a) the central location on the cornea configuration and (b) one of the four near-peripheral corneal locations (nasal, temporal, superior, and inferior).

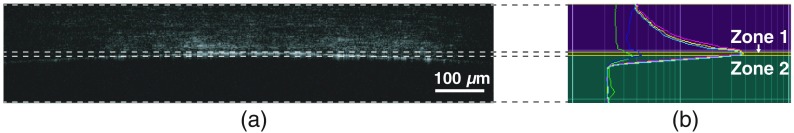

The effective number of focal planes allocated for imaging the curved endothelial layer was two to three depending on the cornea, accounting for the corneal curvature. For estimating the robustness of ECD measurement, each time the cornea platform was realigned mostly along the vertical direction, the GD-OCM images were acquired. Using the GD-OCM 4D™ software (LighTopTech Corp., Rochester, New York), a set of liquid lens voltages corresponding to two or three focal planes around the endothelial layer were configured to partition the effective imaging volume as shown in Fig. 2. The imaging procedure from the sample positioning to the reconfiguration of focal planes was repeated six times at each location by three examiners. We obtained thirty images per cornea (six images per location × five—central, superior, inferior, nasal, and temporal—locations) and a total of one hundred eighty volumetric images for six corneas to analyze.

Fig. 2.

(a) A cross-sectional view (B-scan) around the corneal endothelial layer, which is a 3-D fusion of two images by depth from zone 1 to 2 and (b) the corresponding intensity profiles (A-scans) of each zone. Zone 1 (yellow) covers the central region of the endothelial layer and zone 2 (cyan) covers the peripheral region of the endothelial layer.

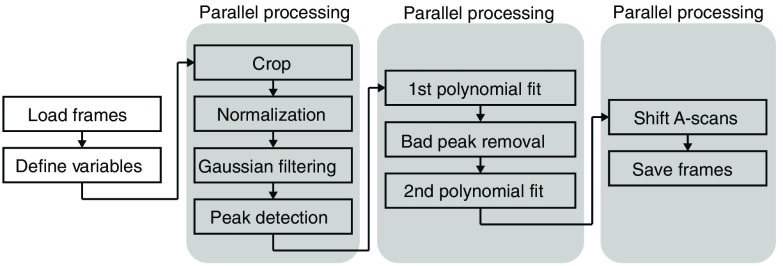

2.3. Flattening the GD-OCM Image

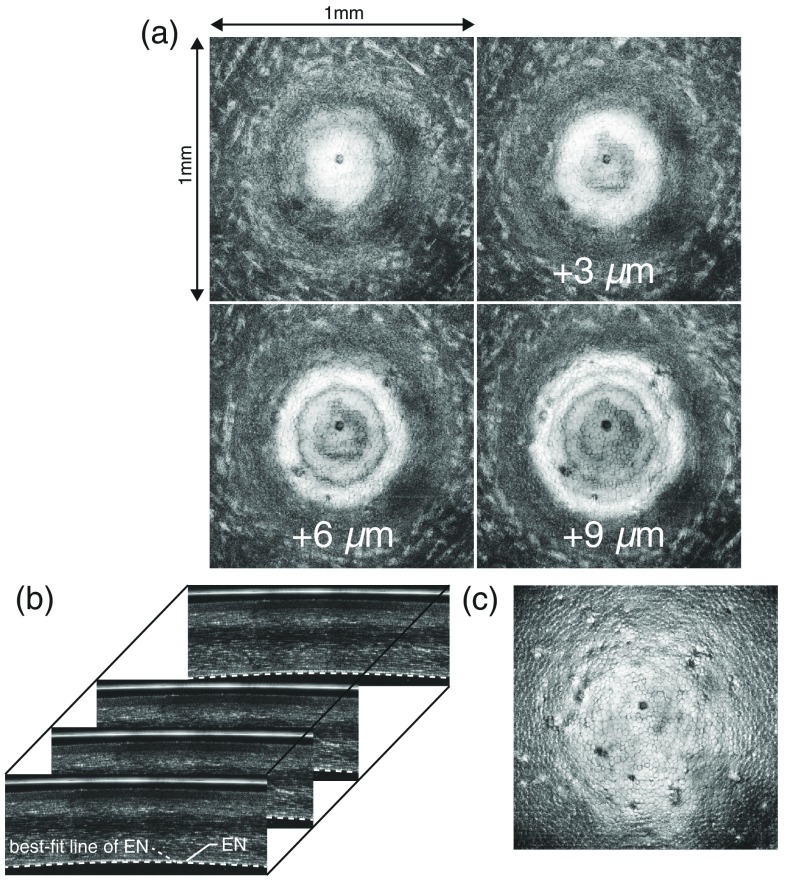

The three-dimensional visualization of the endothelial layer was a curved surface. To easily assess the endothelial cells on the curved surface, the raw GD-OCM images of the endothelial layer were projected onto a single plane using a custom MATLAB® code described in Fig. 3. The imaging flattening code runs on every B-scan image and first finds the depth coordinate of the endothelial layer using the peak intensity of the layer at each A-scan. Using the consecutive coordinates for one B-scan, the endothelium layer is curve-fitted by polynomials as a trial. Then any possible erroneous depth coordinate is automatically found based on the smoothness of the layer and is excluded in the secondary curve-fitting step. After curve-fitting, every A-scan is shifted using the second coordinate to create an image of a flat endothelium layer. This process is simultaneously applied to all B-scans of the volumetric image using the parallel computing toolbox in MATLAB®. The resulting volumetric image is then restacked to extract the wide en face view of the endothelial cells layer [Fig. 4(c)].

Fig. 3.

Flowchart of the image flattening code.

Fig. 4.

Process of the image flattening for cornea 4 at the center: (a) the raw en face images of the endothelial layer (EN) at four different depths of intervals before applying the flattening algorithm, (b) B-scan images, overlaid with the best-fit line of EN (dotted line), and (c) the en-face image of EN after the flattening process.

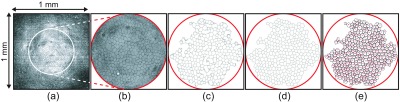

2.4. Counting the Endothelial Cells

The 2-D images of the flattened endothelial layers from all corneas were circularly cropped around the central region for the cell analysis as shown in Fig. 5(a). The diameter of the analysis area, where the cell borders were reasonably visible, ranged from 500 to depending on the location on the cornea. The smaller diameter of was then chosen for the analysis of all of the corneas to compare the results [Fig. 5(b)]. Thirty en face images of the flattened endothelial layers per cornea (total of 180 images for 6 corneas) were distributed to three blinded examiners. Every corner of the endothelial cells was manually identified by the examiners; then a custom MATLAB® algorithm was used to delineate the cell borders with a rule of connecting each corner to three other adjacent corners, as shown in Fig. 5(c). The corner algorithm often misinterpreted the cell borders in a way that caused the border to cross the center of a cell. This occurred both at all outer cells near the window of analysis and at some inner cells of irregular hexagonality. Three blinded examiners edited the borders using Adobe Illustrator® and generated an image of the cell borders, as shown in Fig. 5(d), after comparing the cropped image of the endothelial layer with the cell borders found with the custom MATLAB® algorithm. For the three examiners, it took about one hour from cropping the image to creating the refined cell borders per image. Finally, the images of the cell borders were analyzed using the “Analyze Particles…” plugin in Fiji38 (an advanced version of ImageJ). Every single counted cell was labeled with the cell index and the pixelated area was obtained, coupled to the corresponding cell index as shown in Fig. 5(e).

Fig. 5.

Process of the cell counting of the central endothelium for cornea 6: (a) 2-D en face image of the flattened endothelial layer, (b) the cropped image of (a) within a circle of -in diameter, (c) the endothelial cell borders found using a custom corner method with the manual corner identifications, (d) the corrected borders in (c), and (e) the cell counting using the “analyze particles…” plugin in Fiji.

3. Results

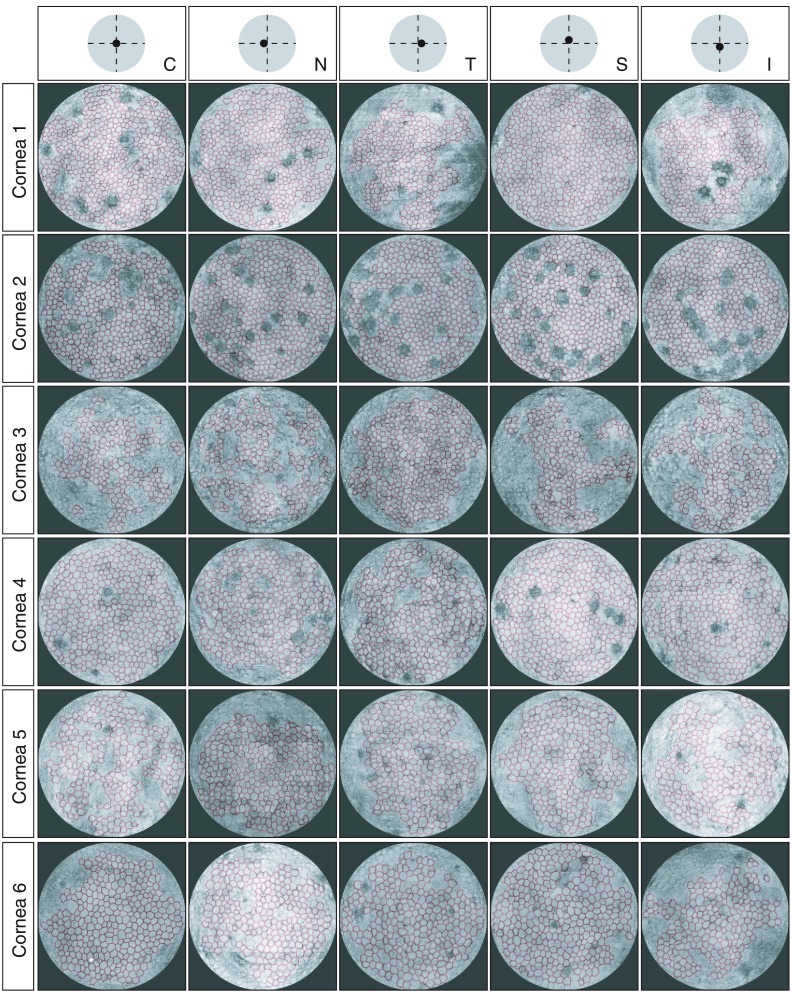

The cell counting procedure was applied to all the processed images of the endothelial layers as shown in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Counted endothelial cells via the corner method, overlaid with the 2-D image of the endothelial layer (N, nasal; T, temporal; C, center; S, superior; and I, inferior, with respect to the apex of the mounted cornea).

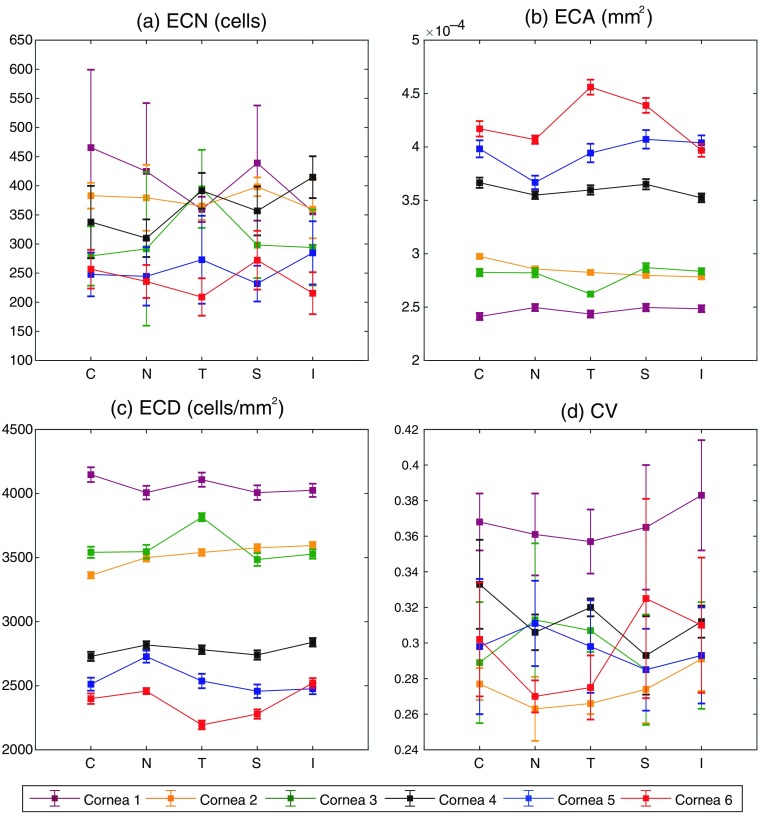

For the ’th sample of the counted cells as shown in Fig. 5(e), , , , and were first evaluated using Eq. (1)–(4), respectively. Then ECN, ECA, ECD, and CV were calculated with six samples as , respectively. The variability in the ECD measurements with six samples was quantified as a ratio of the standard deviation to the mean of the ECD in percent as shown in Eq. (5). The statistics of the donor endothelial cells are summarized in Table 2 and Fig. 7.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

Table 2.

Statistics () of the endothelial cells with the variability in the ECD measurement.

| Cornea ID | Age | Area | ECN (cell) | ECA () | ECD () | CV | Variability in ECD (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 32 | N | 1.327 | ||||

| T | 1.344 | ||||||

| C | 1.389 | ||||||

| S | 1.417 | ||||||

| I | 1.285 | ||||||

| All | 1.918 | ||||||

| 2 | 59 | N | 0.866 | ||||

| T | 0.739 | ||||||

| C | 0.725 | ||||||

| S | 0.793 | ||||||

| I | 0.782 | ||||||

| All | 2.504 | ||||||

| 3 | 59 | N | 1.504 | ||||

| T | 0.822 | ||||||

| C | 1.241 | ||||||

| S | 1.430 | ||||||

| I | 1.022 | ||||||

| All | 3.534 | ||||||

| 4 | 60 | N | 1.045 | ||||

| T | 1.227 | ||||||

| C | 1.318 | ||||||

| S | 1.321 | ||||||

| I | 1.164 | ||||||

| All | 1.929 | ||||||

| 5 | 66 | N | 1.712 | ||||

| T | 2.214 | ||||||

| C | 2.020 | ||||||

| S | 2.141 | ||||||

| I | 1.711 | ||||||

| All | 4.275 | ||||||

| 6 | 66 | N | 0.957 | ||||

| T | 1.550 | ||||||

| C | 1.710 | ||||||

| S | 1.607 | ||||||

| I | 1.526 | ||||||

| All | 5.288 |

Note: N, nasal; T, temporal; C, center; S, superior; and I, inferior with respect to the apex of the mounted cornea. ECDs of corneas 1, 2, and 3 were measured as higher than typical ECDs measured with SM.39 We present the likely cause for this discrepancy in the discussion.

Fig. 7.

Statistics of the donor endothelial cells at five different areas of interest for six corneas: (a) ECN (cell), (b) ECA (), (c) ECD (), and (d) CV. The error bars are the SD of each parameter.

For the purpose of validation, six SM images in total were taken near the central location of corneas 5 and 6 (not exactly at the same location as where the GD-OCM image was taken) then an image with the best quality of contrast was used per cornea to analyze the endothelial cells. The identical procedures of the cell count and parameterization were applied to the SM images. The measured , , and were 51 cells, , and , respectively, for cornea 5; and 56 cells, , and , respectively, for cornea 6. For cornea 6, the fell within the range of the average of all areas. However, for cornea 5, the showed a smaller value than the average of all areas by . The results from six corneas showed that (1) the interoperator variability in the estimation of the ECD via our current modality was for each location and for all locations and (2) the ECD value varied with the location of the assessment, which points to the need for evaluating ECD at multiple locations.40

4. Discussion

We presented a pathway to measure the clinical parameters of cornea endothelial cells, i.e., ECN, ECA, ECD, and CV, with GD-OCM. This metrology showed promise in the assessment with the capability of counting more than 400 cells from a curved cornea (but, depending on the image quality, the number of counted cells can be lower). It is worth noting that the standard deviation for the ECD measurement is small and of the mean ECD value at each location. Furthermore, 3-D visualization of corneal structures with cellular resolution and wide field of view () allows for integrative study of corneal structure across the layers. However, the current metrology has four technical limitations for its practical use in eye banks. First, the current flattening algorithm projects the curved endothelial cells to a plane; therefore, the cellular area measured is smaller than its actual area at the curve. This feature will locally result in increased ECD value depending on the curvature. The future flattening algorithm must account for the curvature dependence in the measurement of the cellular area. Second, a donor cornea had to be mounted onto a corneal artificial chamber for the GD-OCM imaging. GD-OCM is a noninvasive imaging technology but the manner of imaging required a mounted cornea. This limitation originated from the short working distance of the GD-OCM probe, which hindered the ability to image a donor cornea through its cornea storage container. However, this inability has been recently surmounted using the GD-OCM probe with a working distance of 15 mm,35 developed by LighTopTech Co., Rochester, New York. Third, the area of the cellular analysis did not cover the entire field of view of provided by the GD-OCM. This third issue arose from a lower scattering signal at the periphery of the imaging field of view even though the imaging conditions were optimized using multiple focuses across the curved layer. The low scattering signal from the inclined surface is the common phenomena for all intensity-based imaging techniques like SM and IVCM, but the issue might not have been resolved with the interference imaging technique that has an advantage of weak signal detection, herein, GD-OCM. In general, the scattering intensity highly depends on the incident angle of light. If the incident angles at the periphery could be reduced without flattening a donor cornea by force, e.g., adjusting the chief ray angles at the corneal surface via the nontelecentric illumination,41 this issue could be mitigated. Finally, the cell counting method took about 1 h for one en-face image regardless of the examiner. We attribute this issue to the image quality that influences the correct identification of a single endothelial cell. A robust cell counting algorithm that is less sensitive to image quality is needed to speed up this modality.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the Eye Bank Association of America through the 2016 Richard Lindstrom Research Grant. This work was also supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. IIP-1534701, the National Institutes of Health under Grant No. 1R43EY028827-01, and the Center for Emerging and Innovative Sciences.

Biographies

Changsik Yoon is a PhD student at the Institute of Optics, University of Rochester. He earned an MS degree in optics (2014) at the University of Rochester and a BS degree in physics at Yonsei University, South Korea. His current research interests include the development of optical systems for optical metrology and biomedical imaging, with specialties in optical coherence tomography and confocal fluorescence microscopy.

Amanda Mietus obtained her BS degree in optical engineering (2019) at the Institute of Optics, University of Rochester. Her work experience includes areas such as medical imaging, digital image processing, and optical fabrication.

Yue Qi obtained his BS degree in biomedical engineering (2019) at the University of Rochester. His research interests include medical imaging, immunocytochemistry, biomarkers, and bio-photonics.

Jonathon Stone is the director of Processing and Surgeon Relations at Lions Eye Bank at Albany & Rochester, Sight Society of Northeastern NY, Inc. He earned his BS degree in biology (2016) at the Rochester Institute of Technology and a certification as an eye bank technician (CEBT, 2016) through the Eye Bank Association of America. His current research interests include advancing corneal evaluation and processing and preventing endophthalmitis.

Johana C. Escudero holds a BS degree in optical engineering (2017) from the University of Rochester. She was a Paul F. Forman Graduate Fellow in the technical entrepreneurship and management master’s program with a concentration in optics (2018). Her work experience includes areas such as adaptive optics, virtual reality, free-space optical communications, and synthetic optical holography.

Cristina Canavesi holds her PhD in optics from the Institute of Optics, University of Rochester, a master’s in technical entrepreneurship and management from Simon School of Business, University of Rochester, and an MBA from Simon School of Business, University of Rochester. She was awarded the SPIE Optical Design and Engineering Scholarship in 2012. She is cofounder and president of LighTopTech Corp., an optics startup developing high-definition imaging solutions for industrial and medical applications.

Patrice Tankam is an assistant professor at Indiana University School of Optometry. He holds a PhD in optics (2010). He was a postdoctoral fellow at the Institut d’Optique Rhone-Alpes, France, from 2011 to 2012; and a research associate at the Institute of Optics and Center for Visual Science, Rochester, from 2012 to 2016. His research interests include anterior segment imaging, optical metrology, optical coherence tomography. He is a member of OSA, ARVO, and SPIE.

Holly B. Hindman, MD MPH, specializes in the medical and surgical care of corneal diseases. Her research collaborations have focused on using advanced corneal imaging technology to better understand corneal diseases and their impacts on ocular optics with the ultimate goal of improving visual outcomes and patient experience. Over her career she has also provided local and national service to the eye banking community.

Jannick P. Rolland is the Brian J. Thompson Professor of optical engineering at the Institute of Optics, University of Rochester and the CTO of LighTopTech Corp., a startup she cofounded in 2013 in biotechnology. She is the director of the National Science Foundation Center for Freeform Optics (CeFO) and the R.E. Hopkins Center for Optical Design and Engineering. She is a fellow of the OSA and SPIE and the recipient of the 2014 OSA David Richardson Medal and the 2017 Hajim Outstanding Faculty Award.

Disclosures

Cristina Canavesi and Jannick P. Rolland are president and CTO of the startup LighTopTech Corp.; other authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bourne W. M., “Biology of the corneal endothelium in health and disease,” Eye 17, 912–918 (2003). 10.1038/sj.eye.6700559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Price F. W., Jr., Price M. O., “Descemet’s stripping with endothelial keratoplasty in 50 eyes: a refractive neutral corneal transplant,” J. Refract. Surg. 21(4), 339–345 (2005). 10.3928/1081-597X-20050701-07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Melles G. R., et al. , “Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK),” Cornea 25(8), 987–990 (2006). 10.1097/01.ico.0000248385.16896.34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tan D. T., et al. , “Corneal transplantation,” Lancet 379(9827), 1749–1761 (2012). 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60437-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCarey B. E., Edelhauser H. F., Lynn M. J., “Review of corneal endothelial specular microscopy for FDA clinical trials of refractive procedures, surgical devices and new intraocular drugs and solutions,” Cornea 27(1), 1–16 (2008). 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31815892da [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tran K. D., et al. , “Comparison of endothelial cell measurements by two eye bank specular microscopes,” Int. J. Eye Banking 4(2) (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kheirkhah A., et al. , “Overestimation of corneal endothelial cell density in smaller frame sizes in in vivo confocal microscopy,” Cornea 35(3), 363–369 (2016). 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petran M., et al. , “In vivo microscopy using the tandem scanning microscope,” Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 483, 440–447 (1986). 10.1111/nyas.1986.483.issue-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lemp M. A., Dilly P. N., Boyde A., “Tandem-scanning (confocal) microscopy of the full-thickness cornea,” Cornea 4(4), 205–209 (1985). 10.1097/00003226-198504000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Masters B. R., Thaer A. A., “Real-time scanning slit confocal microscopy of the in vivo human cornea,” Appl. Opt. 33(4), 695–701 (1994). 10.1364/AO.33.000695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szaflik J., “White light confocal microscopy of preserved human corneas from an eye bank,” Cornea 26(3), 265–269 (2007). 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318033b2d0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niederer R. L., et al. , “Age-related differences in the normal human cornea: a laser scanning in vivo confocal microscopy study,” Br. J. Ophthalmol. 91(9), 1165–1169 (2007). 10.1136/bjo.2006.112656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Böhnke M., Masters B. R., “Confocal microscopy of the cornea,” Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 18(5), 553–628 (1999). 10.1016/S1350-9462(98)00028-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niederer R. L., McGhee C. N., “Clinical in vivo confocal microscopy of the human cornea in health and disease,” Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 29(1), 30–58 (2010). 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2009.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kitzmann A. S., et al. , “Comparison of corneal endothelial cell images from a noncontact specular microscope and a scanning confocal microscope,” Cornea 24(8), 980–984 (2005). 10.1097/01.ico.0000159737.68048.97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salvetat M. L., et al. , “Comparison between laser scanning in vivo confocal microscopy and noncontact specular microscopy in assessing corneal endothelial cell density and central corneal thickness,” Cornea 30(7), 754–759 (2011). 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3182000c5d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ang M., et al. , “Anterior segment optical coherence tomography,” Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 66, 132–156 (2018). 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2018.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gray K. E., et al. , “Comparative image atlas of current and new technologies in corneal donor tissue evaluation,” Cornea 37, S14–S35 (2018). 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Izatt J. A., et al. , “Optical coherence microscopy in scattering media,” Opt. Lett. 19(8), 590–592 (1994). 10.1364/OL.19.000590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vabre L., Dubois A., Boccara A. C., “Thermal-light full-field optical coherence tomography,” Opt. Lett. 27(7), 530–532 (2002). 10.1364/OL.27.000530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghouali W., et al. , “Full-field optical coherence tomography of human donor and pathological corneas,” Curr. Eye Res. 40(5), 526–534 (2015). 10.3109/02713683.2014.935444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mazlin V., et al. , “In vivo high resolution human corneal imaging using full-field optical coherence tomography,” Biomed. Opt. Express 9(2), 557–568 (2018). 10.1364/BOE.9.000557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leitgeb R. A., et al. , “Extended focus depth for Fourier domain optical coherence microscopy,” Opt. Lett. 31(16), 2450–2452 (2006). 10.1364/OL.31.002450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ang M., et al. , “Evaluation of a micro-optical coherence tomography for the corneal endothelium in an animal model,” Sci. Rep. 6, 29769 (2016). 10.1038/srep29769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bizheva K., et al. , “In vivo imaging and morphometry of the human pre-Descemet’s layer and endothelium with ultrahigh-resolution optical coherence tomography,” Invest. Ophthal. Vis. Sci. 57, 2782–2787 (2016). 10.1167/iovs.15-18936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen S., et al. , “Visualizing micro-anatomical structures of the posterior cornea with micro-optical coherence tomography,” Sci. Rep. 7, 10752 (2017). 10.1038/s41598-017-11380-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bizheva K., et al. , “Sub-micrometer axial resolution OCT for in-vivo imaging of the cellular structure of healthy and keratoconic human corneas,” Biomed. Opt. Express 8(2), 800–812 (2017). 10.1364/BOE.8.000800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tan B., et al. , “250 kHz, resolution SD-OCT for in-vivo cellular imaging of the human cornea,” Biomed. Opt. Express 9(12), 6569–6583 (2018). 10.1364/BOE.9.006569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rolland J. P., et al. , “Gabor-based fusion technique for optical coherence microscopy,” Opt. Express 18(4), 3632–3642 (2010). 10.1364/OE.18.003632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murali S., Thompson K. P., Rolland J. P., “Three-dimensional adaptive microscopy using embedded liquid lens,” Opt. Lett. 34(2), 145–147 (2009). 10.1364/OL.34.000145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murali S., et al. , “Assessment of a liquid lens enabled in vivo optical coherence microscope,” Appl. Opt. 49(16), D145–D156 (2010). 10.1364/AO.49.00D145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meemon P., Widjaja J., Rolland J. P., “Spectral fusion Gabor domain optical coherence microscopy,” Opt. Lett. 41(3), 508–511 (2016). 10.1364/OL.41.000508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tankam P., et al. , “Parallelized multi-graphics processing unit framework for high-speed Gabor-domain optical coherence microscopy,” J. Biomed. Opt. 19(7), 071410 (2014). 10.1117/1.JBO.19.7.071410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tankam P., et al. , “Assessing microstructures of the cornea with Gabor-domain optical coherence microscopy: pathway for corneal physiology and diseases,” Opt. Lett. 40(6), 1113–1116 (2015). 10.1364/OL.40.001113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Canavesi C., et al. , “3-D cellular imaging of the cornea with Gabor domain optical coherence microscopy,” Proc. SPIE 10867, 108670F (2019). 10.1117/12.2507868 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tankam P., et al. , “Capabilities of Gabor-domain optical coherence microscopy for the assessment of corneal disease,” J. Biomed. Opt. 24(4), 046002 (2019). 10.1117/1.JBO.24.4.046002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tran K. D., et al. , “Rapid warming of donor corneas is safe and improves specular image quality,” Cornea 36(5), 581–587 (2017). 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schindelin J., et al. , “Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis,” Nat. Methods 9(7), 676–682 (2012). 10.1038/nmeth.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Galgauskas S., et al. , “Age-related changes in corneal thickness and endothelial characteristics,” Clin. Interv. Aging 8, 1445–1450 (2013). 10.2147/CIA [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Amann J., et al. , “Increased endothelial cell density in the paracentral and peripheral regions of the human cornea,” Am. J. Ophthalmol. 135(5), 584–590 (2003). 10.1016/S0002-9394(02)02237-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beer F., et al. , “Conical scan pattern for enhanced visualization of the human cornea using polarization-sensitive OCT,” Biomed. Opt. Express 8(6), 2906–2923 (2017). 10.1364/BOE.8.002906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]