Abstract

Background

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a major public health problem and threat to maternal and child health in Africa. No prior review has been conducted in Africa using the updated GDM diagnostic criteria. Therefore, this review aimed to estimate the pooled prevalence and determinants of GDM in Africa by using current international diagnostic criteria.

Methods

A systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted by comprehensive search of the published studies in Africa. Electronic databases (PubMed, Scopus, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, Google Scholar, CINAHL, Web of Science, Science direct and African Journals Online) were searched using relevant search terms. Data were extracted on an excel sheet and Stata/ SE 14.0 software was used to perform the meta-analysis. Heterogeneity of included studies were assessed using I2 and Q test statistics. I2 > 50% and Q test with its respective p-value < 0.05 were suggestive for the presence of a significant heterogeneity. Publication bias was assessed using the Egger‘s regression test and funnel plot. Subgroup and sensitivity analyses were done. A random effects model was used to estimate the pooled prevalence of GDM and odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI).

Result

A total of 23 studies were included in the final analysis. The pooled prevalence of GDM in Africa was 13.61% (95% CI: 10.99, 16.23; I2 = 96.1%), and 14.28% (95% CI, 11.39, 17.16; I2 = 96.4%) in the sub-Saharan African region. The prevalence was highest in Central Africa 20.4% (95% CI, 1.55, 38.54), and lowest in Northern Africa 7.57% (95% CI, 5.89, 9.25) sub- regions. Overweight and obesity, macrosomia, family history of diabetes, history of stillbirth, history of abortion, chronic hypertension and history of previous GDM had positively associated with GDM.

Conclusions

The prevalence of GDM is high in Africa. Being overweighed and/or obese, ever had macrocosmic baby, family history of diabetes, history of stillbirth, history of abortion or miscarriage, chronic hypertension and history of previous GDM were factors associated with GDM. Preventing overweighed and obese, giving due attention to women having high-risk cases for GDM in pregnancy are strongly recommended to mitigate the burden.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO (2018:CRD42018116843).

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13690-019-0362-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Prevalence, Gestational diabetes mellitus, Determinants, Updated diagnostic criteria Africa, Systematic review, Meta-analysis

Background

The World Health Organization (WHO) defined Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM) as “any degree of glucose intolerance with onset, or first recognized during pregnancy” [1]. GDM occurred by the increased severity of insulin resistance as well as an impairment of the compensatory increase in insulin secretion during pregnancy [2]. It causes a diverse range of adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes [3] and it is a threat to maternal and child health [4].

The global prevalence of GDM varies widely from 1 to 28% depending on population characteristics, screening methods, and diagnostic criteria [5]. The International Diabetes Federation (IDF)-2015 report showed that about 16.2% of women had some form of hyperglycemia during pregnancy, of which GDM shares about 85.1% of the load [6]. A review revealed the prevalence varies from 5.4% in Europe [7] to 11.5% in Asia [8]. Similarly, the IDF report indicated that there were regional differences in the magnitude of hyperglycemia during pregnancy, for instance, the South-East Asia region had higher (24.2%) as compared to 10.5% of the Africa Region. In addition, the majority (87.6%) of GDM accounts in low and middle-income countries, where access to maternal care was often limited [6].

A review indicated that the occurrence of GDM in sub-Saharan Africa was 14% [9] and the Middle East and North Africa ranged from 8.4 to 24.5% [10] though the study used different screening and diagnostic criteria which masked the true prevalence. Studies also showed that GDM also sees varied among African regions to a certain extent, for instance, East Africa (6%) [11] and West Africa (14%) [12]. Moreover, there were variations within the same sub-regions, like in Rwanda (8.3%) [13], Tanzania (5.9%) [11], and Ethiopia (3.7%) [14]. This disparity in GDM prevalence rate may be due to differences in diagnostic criteria [15–17], screening strategies [9, 18, 19], and population characteristics [20].

Recently, the highest rise in the incidence of obesity, diabetes and other non-communicable diseases are expected to occur in low and medium income countries (LMICs) especially in Africa. It was one of the challenging health problems of sub-Saharan African countries [21, 22].

The approach to screening and diagnosis of GDM around the world has historically been shrouded in controversies and the use of different diagnostic criteria results the different prevalence of GDM.

Lack of uniformity in the protocols for diagnosis vary not only in-between countries, but also within countries and makes it difficult to compare the prevalence of GDM between and within countries. However, in 2013, WHO revised its recommendations for the diagnosis of GDM taking into cognizance the issues raised by the International Association of Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Groups (IADPSG) recommendations [1, 23, 24]. The WHO 2013 modifications along with common diagnostic criteria for GDM by 2013 American Diabetes Association (ADA) [25]. Though, in the last five years, the diagnostic criteria have been changed and there is no known overall prevalence and associated factors of GDM after the change in Africa.

The previous review included studies only in sub-Saharan African countries with lack of uniformity in screening methods, definition, and diagnostic criteria for GDM makes it difficult to compare the prevalence of GDM between and within countries and point out the true pooled prevalence. Furthermore, the review did not include studies conducting by using updated or current diagnostic criteria (WHO 2013), and did not report findings on risk factors for GDM based in the new diagnostic criteria (WHO 2013) [9] and again review without meta-analysis included few studies did not investigate the sources of heterogeneity between the studies and did not report findings on risk factors for GDM [26]. Inconsistent findings were noted among studies conducted in Africa regarding the magnitude as well as factors associated with GDM [9, 15, 26].

There has been no review on the overall prevalence of GDM in Africa and in the sub-regions based on the updated diagnostic criteria. Therefore, the aim of this meta-analysis is to estimate the prevalence of GDM in a broader scope including the countries across Africa using the pieces of evidence from those studies conducted by using the updated diagnostic criteria for GDM. In addition, we also examine the risk factors for GDM among the African populations.

The findings of this study would underscore the importance and urgency of scaling-up GDM screening and its management throughout Africa. Moreover, understanding the prevalence and determinates of GDM in Africa may provide evidence on how interventions should be targeted to reduce the magnitude of the problem, to improve maternal and child health, and halt the burden of GDM in the sub-regions of Africa.

Therefore, We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to determine the prevalence and determinates of GDM in Africa, using pieces of evidence based on the updated and the current international GDM diagnostic criteria.

Materials and methods

Protocol and registration

The present review was registered with PROSPERO(2018:CRD42018116843) [27] and conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses (PRISMA) [28]. A protocol was developed during the planning process.

Study design and search strategy

A systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted using published articles on the prevalence and associated factors of GDM in Africa with the updated international diagnostic criteria. The databases used to search for studies were PubMed, Scopus, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, Google Scholar, CINAHL, Web of Science, Science direct and African Journals Online (AJOL). All potentially eligible studies were accessed through this searching strategy for “gestational diabetes mellitus OR hyperglycemia in pregnancy OR impaired glucose tolerance OR gestational hyperglycemia” AND “name of Africa countries” were used separately and in combination of the Boolean operators terms “OR” and “AND” as necessary. Likewise, terms like “determinant factors OR determinant variables OR associated factors” were used in combination with the above search terms. The search was also made by combining the above search terms with the names of all countries included in Africa and sub-region of Africa. A combination of expanded search term and free-text searches were used as shown in Table 4 in Appendix 1. Then the reference lists of the retrieved studies were also followed to access for additional articles and screened for its suitability to be recruited into this review.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Any studies in Africa that reported prevalence and risk factors for GDM and fulfilled the following criteria were entered into the analysis, including the following factors: (1) being conducted in African countries classified by the United Nations Statistics Division [29]; (2) Epidemiological studies had reported prevalence and risk factors of GDM as primary results; (3) provided the prevalence and OR with 95% confidence interval (CI) or total of participants and number of GDM events (3) Being published in English language journals from January 1, 2013 to November 26, 2018; (4) studies conducted on pregnant women regardless of gestational age, sample size and study setting; and (5) studies used the updated international diagnostic criteria for GDM diagnosis was made by using the new 2013 WHO [1] or ADA [25] or modified IADPSG [30] diagnostic criteria.

Exclusion criteria

If an article failed to mention any of the above inclusion criteria it was excluded. In addition, studies were excluded if they were: (1) studies with poor definition of the outcome of interest; (2) qualitative studies, review articles, case reports, and case series regardless of the number of cases, narrative reviews, conference abstracts with no full information or if authors have not responded to our inquiry on the full text, editorials, commentaries, letters to the editor, author replies, and other publications that do not include quantitative data on the prevalence and/or associated factors of GDM; (3) studies presenting contradictory/unclear quantitative measures that could not be verified with authors; (4) duplicated studies on GDM ascertainment in the same population. In the case of duplicated publications, only the study containing the most important information in the context of prevalence and ascertainment methodologies or most recent results was included; and (5) studies including GDM patients with other metabolic disorders or other non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in the same category.

Outcomes measurement

Gestational diabetes mellitus was diagnosis, if one or more of the following abnormality are met, fasting plasma glucose 5.1–6.9 mmol/l (92–126 mg/dl), one-hour plasma glucose ≥10.0 mmol/l (180 mg/dl), 2-h glucose 8.5–11 mmol/l (153–199 mg/dl) after overnight fasting with 75 g glucose load [1, 25, 30]. WHO endorsed the modified IADPSG criteria by 2013 [31].

Study selection

Relevant papers identified from the aforementioned databases and websites were imported into an EndNote X7, and duplicates were removed. Retrieved articles were assessed by two review authors with extensive experience in systematic reviews. Screening of titles abstracts and full text quality was conducted independently by two review authors (A & Y) on the bases of these inclusion criteria. Disagreement between the two reviewers was resolved by consensus or the third reviewer (O) made the decision regarding inclusion of the article in the final review.

Data extraction and quality assessment

The selected papers were fully reviewed and the required information for the systematic review was extracted and summarized using an extraction table in Microsoft Office Excel software. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline were followed throughout the review and analysis processes [32]. The study quality or risk of bias was assessed using the adopted a risk of bias tool developed by Hoy et al. [33] and modified it to suit to our study. The tool consists of ten items that assess sampling, attrition, measurement and reporting bias. The validity of methodology, appropriateness and reporting of results were also assessed (Table 5 in Appendix 2). When the information provided was not adequate to assist in making judgment for a certain item, we agreed to grade that item with a ‘NO’ meaning high risk of bias. Each study was graded depending on the number of items judged ‘YES’ as low (≥ 8), moderate (6 to 7) or high risk of bias (≤ 5) (Table 6 Appendix 2).

The main findings regarding the prevalence and risk factors for GDM were summarized by two authors, and excel sheet was prepared under subheadings agreed upon by all authors. Data were extracted from each study regarding name of author (s), country and sub-region, Study design, setting, year of publication, year of study conducted (year of survey), sample size, response rate, gestational age when GDM screen, participant selection, age of pregnant women, test approach (one step vs two step), screening criteria (Universal vs selective), Blood glucose levels measured by (Glucometer vs Laboratory method), prevalence of GDM (including percentage and 95% CI), odds ratio, relative risk of certain risk factors. The outcome measures extracted were prevalence of GDM and risk factors in terms of differences of proportion/percent of GDM in the total pregnant women were participated.

Statistical methods and analysis

The data were entered into Microsoft Excel, exported into STATA/SE version 14 software for analysis. The heterogeneity test of the included studies was assessed by using the I2 statistics and Q test with its respective p-value. The presence of heterogeneity was considered to I2 test statistics results > 50% [34, 35] and Q test and its respective P-value < 0.05. Furthermore, the heterogeneity was presumed in the protocol based on an estimate of a potential variation across studies and depicted in the analyses, we used a random effects model as a method of analysis [34]. The publication bias was assessed using the Egger‘s regression test objectively and funnel plot subjectively [36, 37]. Any asymmetry of a funnel plot and statistical significance of Egger’s regression test (P-value < 0.05) was suggestive of publication bias. Therefore, the Duval and Tweedie nonparametric trim and fill analysis using the random effect analysis was performed [38]. Forest plots used to present the combined prevalence and 95% confidence interval (CI). Subgroup analyses for prevalence were performed by sub regions of Africa, publication year of studies, quality of the study and study design. In addition, a sensitivity analysis was done to point out the study (s) that caused variation. The different factors associated with GDM were presented using odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence interval (CI).

Result

Description of included studies

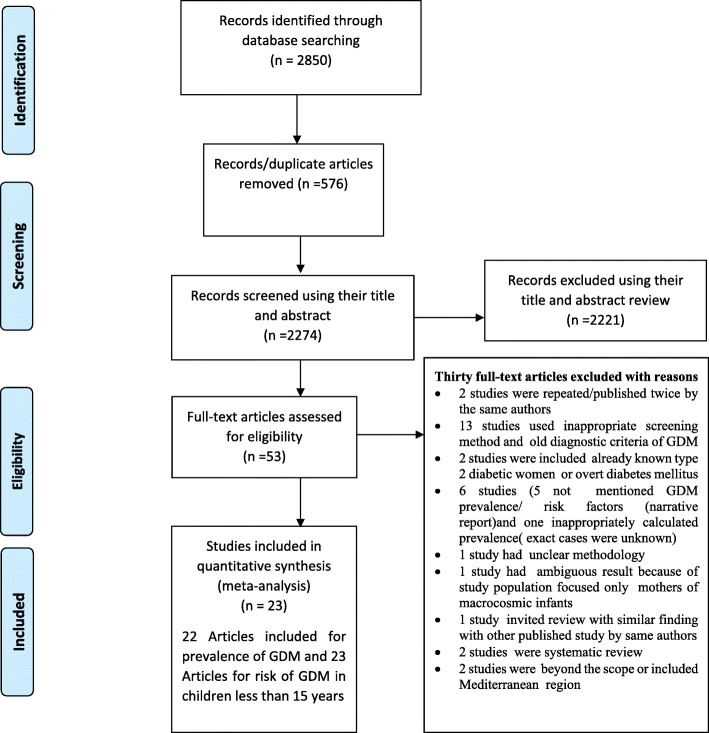

A total of 2,850 published articles were retrieved; of which 576 duplicate records were removed and 2221 records were excluded after screening by title and abstract. A total of 53 full-text articles were screened for eligibility. From those, 30 full-text articles were excluded, because they failed to fulfill the eligibility (n = 13) and 17 articles were excluded for reasons for prior criteria. Finally, 23 studies were included in the final analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the included studies for the systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence and determinants of gestational diabetes mellitus in Africa, 2013–2018

Characteristics of the included studies

Thirteen African countries were represented in this review. Of these, 9 (39.1%) of the studies were from West African [17, 39–46], 6 (26.08%) from East African countries [11, 13, 47–50], 3 (13.04%) from only one Central Africa (Cameroon) [51–53], 3 (13.04%) from Southern Africa [15, 54, 55], and 2 (8.695%) were from only one Northern African country (Egypt) [56, 57]. Regarding the study design, the majority [13] were cross-sectional [11, 13, 40, 41, 43–45, 48, 53–57], nine were cohort [15, 17, 39, 42, 47, 49–52], and one case control study [46]. A total of 11,902 participants were included in the review (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary characteristics of studies in the meta-analysis to show the prevalence Gestational diabetes mellitus in Africa, 2013–2018

| S.N | Author, year of publication (Year study conducted or year of survey) |

Country, Sub region | Study design | Sample size | Response rate | Mean age (SD)/range | GA when tested GDM(week) | Screening criteria | Test approach | Blood glucose levels were measured by | Prevalence of GDM (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Niyibizi et al., 2016 [13] (2012) |

Rwanda, East Africa | Institution-based cross-sectional | 96 | 100% |

M = 27 ± 9.8 R = 21–45 |

24–28 | Universal | One step | Glucometer (ACCU-CHECK-Aviva Plus) + laboratory glucose Oxidase method) | 8.3% (2.78,13.82) |

| 2 | Sagheer and Hamdi, 2018 [56] (2015) | Egypt, North Africa | Institution-based Cross-sectional | 700 | 89.7% |

M = 26.5 ± 5.5 R = 18–42 |

24–28 | Universal | One step | Laboratory method | 7.43% (5.49,9.37) |

| 3 | Ogoudjobi et al., 2017 [44] (2015–2017) | Benin, West Africa |

Institution-based cross-sectional |

967 | 100% |

M = 28.5 ± 5.7 R = 16–44 |

24–28 | Universal | One step | Laboratory glucose oxidase method | 7.5% (5.84.9.16) |

| 4 | Oppong et al., 2015 [45](2013) | Ghana, West Africa | Institution-based cross-sectional | 399 | 100% | NR | 24–28 | Universal | One step | Laboratory method | 9.3% (6.45,12.15) |

| 5 | Oriji et al., 2017 [41] (2015) | Nigeria, West Africa | Institution-based cross-sectional | 235 | 94% | NR | 24–28 | Universal | One step | Laboratory glucose oxidase method | 14.9% (10.35,19.45) |

| 6 | Agbozo et al., 2018 [39] (2016) | Ghana, West Africa | Institution-based Prospective study | 435 | 88.6% | R = 15–54 | 13–34 |

Selective (13th–20th) Universal (20th -34th) |

One step | NR | 9.0% (6.3, 11.69) |

| 7 | Nakabuye et al., 2017 [47] (2014) | Uganda, East Africa | Prospective cohort study | 251 | 75.4% | NR | 24–36 | Universal | One step | Glucose meter (Glucocard™ Σ1070) | 30.3% (24.61,35.99) |

| 8 |

Macaulay et al., 2018 [54] 2013–2017 |

South African, Southern Africa | Institution-based cross-sectional | 1906 | 94.8% |

M = 30 R = 25–35 |

24–28 | Universal | One step | Glucometer(ACCU-CHEK) | 9.1% (7.81, 10.39) |

| 9 |

Abbey and Kasso, 2018 [40] (2016–2017) |

Nigeria, West Africa | cross-sectional study | 288 | > 100% |

M = 31.18 ± 4.7 |

< 14 weeks | Universal | One step | Laboratory glucose oxidase method | 21.2% (16.48, 25.92) |

| 10 |

Njete, John et al., 2018 [48] (2015–2016) |

Tanzania, East Africa | Cross-sectional study | 333 | 77% | M = 27.9 ± 5.9 | 24–28 | Universal | One step | Plasma-calibrated hand-held glucometers (GlucoPlus) | 19.5% (15.24,23.76) |

| 11 |

Pastakia et al., 2017 [49] (2013–2015) |

Kenya, East Africa | Prospective study | 616 | 71.1% | M = 26.1 | 24–32 | Universal | Two step | Laboratory method and POC tests | 2.9% (1.57,4.23) |

| 12 |

Olagbuji et al., 2017 [42] (2015–2016) |

Nigeria, West Africa | Institution-based prospective cohort study | 280 | NR | R = 18–45 | 24–32 | Universal | Two step | Laboratory glucose oxidase method | 15.71% (11.45,19.97) |

| 13 |

Munang et al., 2017 [51] (2012–2013) |

Cameroon, Central Africa | Institution-based prospective study | 400 | 82% | M = 26 ± 5 | 24–28 | Universal | Two step | Glucometer (Accu-Chek® Compact Plus) | 32.1%. (27.52,36.68) |

| 14 |

Jao, Wong et al., 2013 [53] (2013??) NR |

Cameroon, Central Africa | Cross Sectional study | 316 | NR | R = 15–50 | 24–28 | Universal | One step | NR | 6.3% (3.62,8.98) |

| 15 |

Djomhou et al., 2016 [52] (2013) |

Cameroon, Central Africa | Institution-based prospective cohort study | 100 | 100% | M = 27 ± 6 | All GA | Universal | NR | Laboratory method | 22% (13.88,30.12) |

| 16 |

Olagbuji et al., 2015 [17] (2012–2014) |

Nigeria, West Africa | Institution-based prospective study | 1059 | 81.7% | M = 30.7 ± 4.4 | 24–32 | Universal | one-step | Laboratory glucose oxidase method | 8.6% (6.91,10.29) |

| 17 |

Ogu et al., 2017 [43] (2014–2015) |

Nigeria, West Africa | Institution-based cross-sectional | 837 | NR |

M = 30.67 ± 4.55 R = 18–48 years |

NR | Selective | NR | NR | 3.3% (2.09, 4.51) |

| 18 |

Khalil et al., 2017 [57] (2015–2016) |

Egypt, North Africa | Institution-based Cross sectional | 250 | 100% | NR | 24–28 | Universal | Two step | Laboratory glucose oxidase method | 8%. (4.64, 11.36) |

| 19 |

Adams and Rheeder, 2017 [15] (2012??) NR |

South Africa, Southern Africa | Prospective cohort study | 554 | 55.4% | M = 27.2 ± 5.8 | 24–28 | Universal | One step | Laboratory method + POC test | 25.8% (22.16, 29.44) |

| 20 |

Adoyo et al., 2016 [50] (2015) |

Kenya, East Africa | Cohort study design | 238 | 93.7 | M = 33.06 (GDM) & 27.9 (Non GDM) | ≥28 | NR | NR | NR | 27.73% (22.04,33.42) |

| 21 | Mwanri et al., 2013 [11] (2011–2012) |

Tanzania, East Africa |

cross-sectional study | 910 | NR |

M = 27.5(5.0) Urban & M = 26.6 (5.3) Rural |

≥20 Weeks | Universal | One step | POC (HemoCue Glucose B-201) | 13.1% (10.91, 15.29) |

| 22 |

Asare-Anane et al. 2014 [46] 2010. |

Ghana West Afrcia |

Case control | 200 | 100 | NR | All GA | Universal | NR | NR | NA |

| 23 |

Mathilda et al., 2017 [55] (2010–20140 |

Zimbabwe. Southern Africa | Institution-based cross-sectional | 532 | 100% | M = 26.9 ± 6.7 | All GA | NR | NR | Laboratory method | 8.5 (6.13, 10.87) |

GDM Gestational diabetes mellitus, M mean, R Range, SD Standard deviation, NR Not Reported, GA Gestational Age, POC Point of care, NA Not Applicable

Studies were categorized according to their risk of bias; ten studies were considered to have low 12 (52.2%), 4 (17.4%) moderate, and 7 (30.43%) as having high risk of bias (Tables 5 and 6 in Appendix 2). The studies with high risk of bias had either the small sample size, unclear selection of study participants, unclear measurement protocol, low response rate, and/or data collected from hospital records rather than from subjects.

Prevalence of GDM in Africa

Twenty-two articles included in the meta-analysis to estimate the prevalence of GDM in Africa. A total of 11,702 pregnant women were included in the analysis. The included studies reported sample size which ranged from 96 participants in Rwanda [13] to 1906 in South Africa [54] (Table 1).

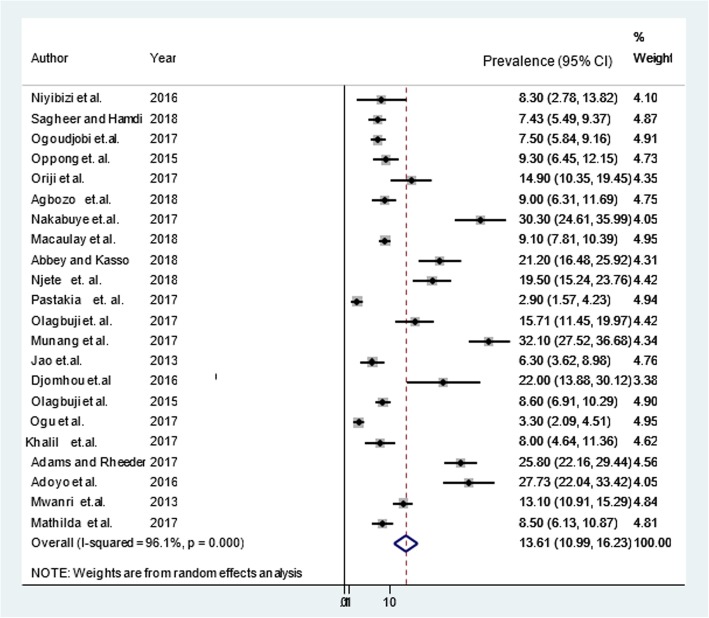

The random effect pooled prevalence of GDM in Africa was 13.61% (95% CI: 10.99, 16.23; I2 = 96.1%, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2). However, there was a publication bias (Egger’s test, βo = 7.98, p-value < 0.001). The trim and fill analysis added ten studies and the pooled prevalence of GDM in Africa varied to 6.81% (95% CI: 3.96, 9.7). There was significant heterogeneity (I2 = 96.1%) and Q test (Tau-squared = 35.6783, p-value p < 0.001) in the prevalence of GDM in Africa, which is likely due to differences prevalence in sub regions of Africa, publication year of studies, risk of bias and study design. Therefore, sub-group analysis showed that the pooled prevalence of GDM in sub-Saharan Africa was 14.28% (95% CI: 11.39, 17.16; I2 = 96.4%, p < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

Prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus in Africa, 2013–2018

Similarly, the sub-group analysis by sub-region showed that the prevalence of GDM was highest, 20.4% (95% CI: 1.55, 38.54) in the Central African sub-region, followed by 16.76% (95% CI: 8.47, 25.05) in East African sub-region, 14.28% (95% CI: 6.22, 22.35) in Southern Africa, 10.72% (95% CI: 7.52, 13.91) in West Africa, and the lowest was in Northern Africa, 7.57% (95% CI: 5.89, 9.25) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Subgroup analysis of the prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus in Africa, 2013–2018

| Subgroup | Number of studies | Total Sample |

Prevalence (95%CI) | Heterogeneity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q-value | Df | I2 | P-value | ||||

| Sub-region | |||||||

| East Africa | 6 | 2444 | 16.76 (8.47, 25.05) | 102.242 | 5 | 97.6 | < 0.001 |

| Southern Africa | 3 | 2992 | 14.28 (6.22, 22.35) | 49.0036 | 2 | 97.3 | < 0.001 |

| West Africa | 8 | 4500 | 10.72 (7.52, 13.91) | 18.7272 | 7 | 93.4 | < 0.001 |

| Central Africa | 3 | 816 | 20.04 (1.55, 38.54) | 259.1118 | 2 | 97.9 | < 0.001 |

| Northern Africa | 2 | 950 | 7.57 (5.89, 9.25) | 0.00 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.774 |

| Sub Saharan African countries | 20 | 10,752 | 14.28 (11.39, 17.16) | 39.6514 | 19 | 96.4 | < 0.001 |

| Publication year of study | |||||||

| 2013 | 2 | 1226 | 9.75 (3.08, 16.41) | 21.5605 | 1 | 93.3 | < 0.001 |

| 2015 | 2 | 1458 | 8.78 (7.33, 10.23) | 0.0000 | 1 | 0.0 | 0.679 |

| 2016 | 3 | 434 | 19.27 (6.63, 31.91) | 113.7686 | 2 | 91.7 | < 0.001 |

| 2017 | 10 | 4922 | 14.55 (9.69, 19.40) | 58.1562 | 9 | 97.7 | < 0.001 |

| 2018 | 5 | 3662 | 12.67 (8.78, 16.55) | 17.1333 | 4 | 91.9 | < 0.001 |

| Risk of bias | |||||||

| Low | 12 | 7488 | 13.49 (10.08, 16.90) | 33.9381 | 11 | 96.6 | < 0.001 |

| Moderate | 3 | 817 | 14.56 (3.19, 25.94) | 96.6674 | 2 | 96.5 | < 0.001 |

| High | 7 | 3397 | 13.77 (8.14, 19.41) | 52.1874 | 6 | 95.7 | < 0.001 |

| Study design | |||||||

| Cross-sectional study | 13 | 7769 | 10.14 (7.86, 12.41) | 15.0084 | 12 | 92.1 | < 0.001 |

| Prospective study | 9 | 3933 | 19.09 (12.35, 25.82) | 100.7873 | 8 | 97.9 | < 0.001 |

Sub-group analysis by publication year of studies indicated a highest, 19.27% (95% CI: 6.63, 31.91) prevalence of GDM was observed by 2016 and the lowest, 8.78% (95% CI: 7.33, 10.23) by 2015. Relating to the quality score of included studies, the prevalence of GDM in articles of low risk bias, 13.49% (95% CI: 10.08, 16.90), moderate risk bias 14.56% (95% CI: 3.19, 25.94), and high risk of bias (13.77% (95% CI: 8.14, 19.41), were similarly observed. Furthermore, the prevalence of GDM in articles conducted by cross sectional and prospective study design was 10.14% (95% CI: 7.86, 12.41) and 19.09% (95% CI: 12.35, 25.82) respectively (Table 2).

Factors associated with GDM

Demographic characteristics

The demographic factors included in this analysis were maternal age, parity, obesity, and family history of DM. A separate analysis was conducted for each variable. A total of 13 articles [13, 17, 40, 41, 43–45, 47, 48, 50, 54, 56, 57] were included to determine the association of maternal age and GDM. Seven out of 13 studies [17, 41, 44, 48, 50, 54, 57] had a significant association between maternal age and GDM, while the other six articles [13, 40, 43, 45, 47, 56] showed non-significant associations. In the random-effect model, the pooled odds of GDM among women aged ≥30 years is increased by nearly three folds (OR = 2.83; 95% CI: 1.75, 4.59: The I2 = 90.5%, p-value < 0.001). The sensitivity analysis showed that there is no influential study that caused variation, however, there was a publication bias (Egger’s test, βo = 2.64; p-value = 0.004). The final pooled effect size by the trim and fill analysis by added seven studies showed that there was no significant association between maternal age and GDM, OR = 1.27 (95% CI = 0.81, 1.99, p-value = 0.297). Moreover, a total of 11 articles [40, 41, 43–48, 54, 56, 57] were included to determine the association of multi-parity and GDM, and only five of the studies [43, 46–48, 57] had a significant association with GDM. There was heterogeneity (I2 = 79.3%, p-value < 0.001) among subgroups and no influential study caused variations by the sensitivity analysis. There was a publication bias (Egger’s test, βo = 3.9; p-value = 0.004). However, the pooled effect size by the trim and fill analysis by added six studies showed that there was no significant association between multi parity (≥ 2) and GDM, OR = 1.09 (95% CI = 0.63, 1.90, p-value = 0.758) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of the meta-analysis of associated factors for gestational diabetes mellitus in Africa, 2013–2018

| No. | Factors | No of studies | OR (95% CI) | P value | Heterogeneity | Publication bias (Egger’s test) |

Range of result of by omitted one study at a time | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q-value | Df (Q) | p –value | I2 | p- value | Minimum | Maximum | |||||

| 1 | Maternal age (≥ 30 year) | 13 | 1.27 (0.810, 1.992) | 0.297 | 249.831 | 19 | < 0.001 | 90.5% | 0.004 | 0.56 | 1.12 |

| 2 | Maternal overweight and/obesity | 12 | 3.51 (1.92, 6.40) | 0.005 | 146.455 | 12 | < 0.001 | 88.4% | 0.231 | 0.65 | 1.86 |

| 3 | Parity (≥ 2) | 11 | 1.091 (0.628, 1.897) | 0.758 | 121.267 | 16 | < 0.001 | 79.3% | 0.004 | 0.34 | 1.39 |

| 4 | Having macrosomic baby | 10 | 2.23 (1.12,4.44) | 0.023 | 55.883 | 10 | < 0.001 | 76.8% | 0.017 | 0.42 | 1.65 |

| 5 | Family history of diabetes | 13 | 2.69 (1.84, 3.91) | 0.005 | 84.227 | 16 | < 0.001 | 70.0% | 0.143 | 0.61 | 1.36 |

| 6 | History of still birth | 4 | 2.92 (1.23, 6.93) | 0.015 | 12.751 | 3 | 0.005 | 76.5% | 0.742 | 0.20 | 1.94 |

| 7 | History of abortion | 8 | 2.21 (1.68, 2.92) | 0.000 | 13.285 | 8 | 0.102 | 35.9% | 0.985 | 0.52 | 1.07 |

| 8 | History of hypertension | 9 | 2.49 (1.35, 4.59) | 0.004 | 31.043 | 8 | < 0.001 | 74.2% | 0.952 | 0.30 | 1.52 |

| 9 | Previous history of GDM | 3 | 14.16 (2.39, 84.08) | 0.004 | 5.619 | 2 | 0.060 | 64.4% | 0.128 | 0.87 | 4.43 |

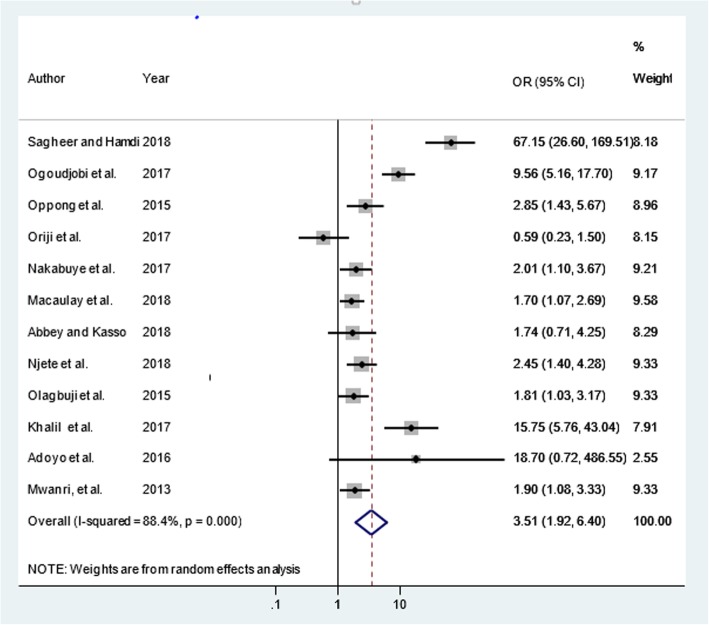

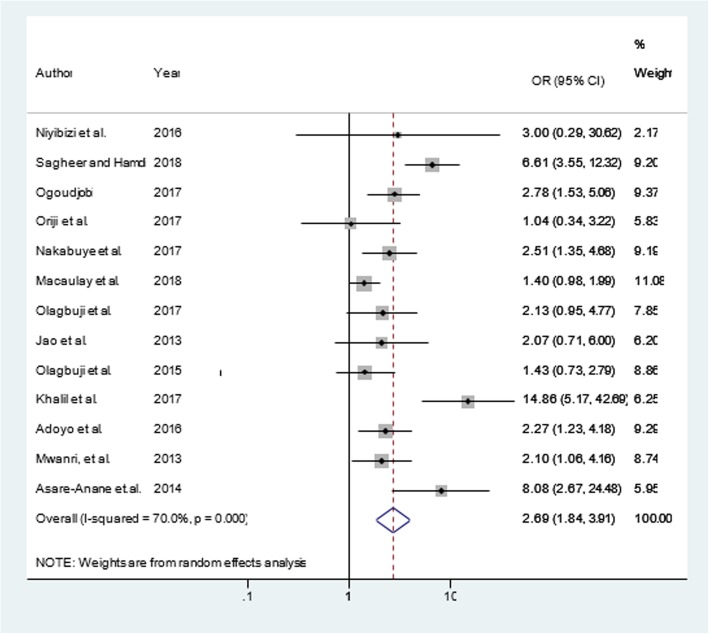

Similarly, a total of 12 articles [11, 40–42, 44, 45, 47, 48, 50, 54, 56, 57] were included to determine the association of maternal overweight and/or obesity and GDM. Nine of the included studies [11, 17, 44, 45, 47, 48, 54, 56, 57] had significant association while the rest [40, 41, 50] showed a non-significant association between maternal overweight and/or obesity and GDM. Even though, there was heterogeneity (I2 = 88.4%, p-value < 0.001) among subgroups, there was no influential study that caused variation by sensitivity analysis and no publication bias (Egger’s test, βo = 3.22; p-value = 0.231). The final pooled effect size showed that pregnant women with maternal overweight and/or obesity were more than three times (OR = 3.51; 95% CI = 1.92, 6.40) more likely to increase the risk of GDM (Fig. 3). Additionally, out of a total of 13 articles [11, 13, 17, 41, 42, 44, 46, 47, 50, 53, 54, 56, 57] included to determine the association of family history of diabetes mellitus and GDM seven of them [11, 44, 46, 47, 50, 56, 57] had significant association with GDM. The pooled odds of developing GDM was (OR = 2.69; 95% CI = 1.84, 3.91: I2 = 70%, p-value < 0.001), there was no any influential study that caused variations by the sensitivity analysis and no publication bias was observed (Egger’s test, βo = 1.965; p-value =0.143). The random-effect analysis showed that family history of diabetes mellitus were nearly three times more likely increased the risk of GDM (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Maternal overweight and/ obesity and gestational diabetes mellitus in Africa, 2013–2018

Fig. 4.

Family history of diabetes mellitus and gestational diabetes mellitus in Africa, 2013–2018

Medical factors

The medical factors included in this analysis were chronic hypertension and history of previous GDM. A total of 9 articles [15, 43–45, 48, 50, 56, 57] were included to see the association of history of chronic hypertension and GDM, of which 4 of them [15, 44, 50, 56] have shown a significant association with GDM. In the random-effect model, the overall odds of developing GDM among women suffered from chronic hypertension was raised by 2.5 folds (OR = 2.49; 95% CI = 1.35, 4.59: (I2 = 74.2%, p-value < 0.001) than their counterparts. According to the sensitivity analysis, there was no any influential study that causes variation. Likewise, publication bias was not a concern (Egger’s test, βo = − 0.096; p-value =0.952). Moreover, three articles [41, 45, 56] were included to determine the association of the history of previous GDM on the current risk of GDM, and one study [41] showed that it has a significant positive association. The pooled odds of GDM with women experienced in GDM in the previous times was increased by (OR = 14.16; 95% CI = 2.39, 84.08: (I2 = 64.4%, p = 0.060)). There was the absence of an influential study that contributed to the variation. No publication bias was observed (Egger’s test, βo = − 3.95; p-value = 0.128). Therefore, the final pooled effect size showed that having the history of previous GDM were fourteen times more likely increased the risk of GDM (Table 3).

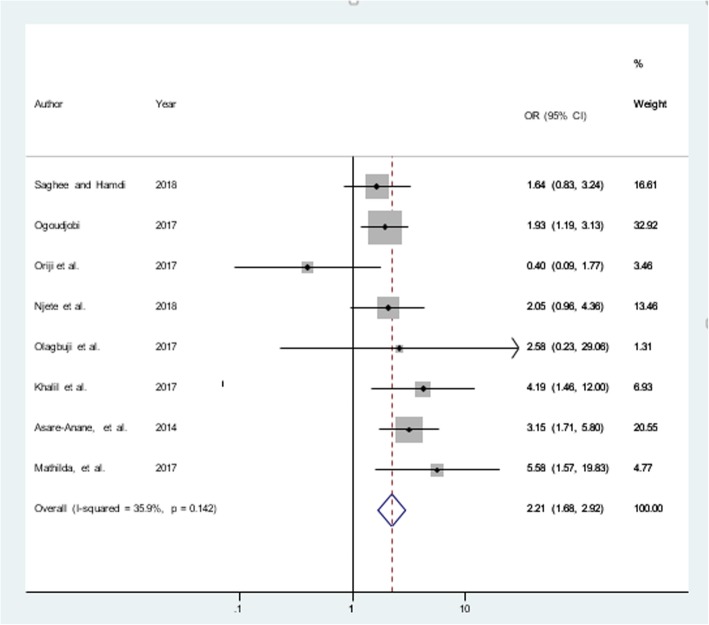

Obstetric factors

The obstetric factors included in this analysis were having history macrosomia (large size baby), stillbirth, and abortion or miscarriage. A total of 10 articles [17, 40–42, 44, 47, 48, 54, 55, 57] were included to determine the association of macrosomia and GDM, and half of them found a positive association [40, 44, 55, 57]. In the random-effect model, the pooled odds of experiencing GDM among women who gave birth to the macrocosmic neonate in former pregnancy was raised by nearly three times (OR = 2.81; 95% CI = 1.52, 5.21: I2 = 76.8%, p < 0.001). The sensitivity analysis revealed that no influential study that resulted in variation. Additionally, there was a publication bias (Egger’s test, βo = 6.46; p-value = 0.017), and the trim and fill analysis by added one study highlighted that women who gave birth to macrocosmic baby were two times more likely to develop GDM as compared to their counterparts, OR = 2.23 (95% CI = 1.12, 4.44, p-value = 0.023) (Table 3). Additionally, a total of four articles [11, 41, 44, 46] were included to determine the association of history of stillbirth and GDM, and only one of the study [41] showed a non-significant association. In the random-effect model, the overall odds of GDM among women having history of stillbirth was three times (OR = 2.92; 95% CI = 1.23, 6.93: I2 = 76.5%, p < 0.001). There was no any influential study that caused variation according to the sensitivity analysis and no publication bias was observed (Egger’s test, βo = − 1.93; p-value =0.742) (Table 3). Furthermore, eight articles [41, 42, 44, 46, 48, 55–57] were included to determine the association of history of abortion and GDM, and half of them [44, 46, 55, 57] showed a positive association. The overall odds of GDM among women having abortion history was two times (OR = 2.21; 95% CI = 1.68, 2.92: I2 = 35.9%, p = 0.142), and no publication bias was detected (Egger’s test, βo = 0.233; p-value = 0.985) (Fig. 5). Moreover, supplementary files on original funnel plots and funnel plots improved by the trim and fill method also presented (Additional file 1).

Fig. 5.

History of abortion and gestational diabetes mellitus in Africa, 2013–2018

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted to estimate the prevalence and determinants of GDM in Africa using the updated and current international diagnostic criteria for GDM. The IDF reports GDM is a severe and neglected threat to women and their offspring [4].

The pooled prevalence of GDM in Africa was 13.61% (95% CI: 10.99, 16.23) with a higher estimate compared to other low and middle-income countries (LMIC). However, it was varied to 6.81% (95% CI: 3.96, 9.7) by added ten studies in the trim and fill analysis. High prevalence of GDM were reported in some included studies in the this meta-analysis for instance in Cameron (32.1%) [51] and Uganda (30.3%) [47]. It might be due to these studies were universal screening strategy for all pregnant woman after 24 weeks of gestation. Selective screening strategy misses up to 45% of mothers with GDM [58, 59].

In this meta-analysis the pooled prevalence of GDM in sub-Saharan Africa was 14.28%, which depicts a public health concern. The finding is higher as compared to the finding of a previous systematic review conducted in sub-Saharan Africa (5.1%) [9], Africa (6.0%) [26], Europe (5.4%) [7], Asia (11.5%) [8], and Eastern and Southeastern Asia (10.1%) [18]. Similarly, it’s greater than those whose results were reported in Western countries, including Europe, US, and Australia, reporting the prevalence of 5.4, 9.2, and 5.7%, respectively [7, 60, 61]. This could be because of the use of different diagnostic criteria and the lack of consensus regarding the use of diagnostic criteria for GDM which might have largely contributed to the heterogeneity of GDM prevalence. In addition, the discrepancies could be related to a higher detection rate in recent years due to improved diagnosis of GDM during pregnancy at earlier gestational age and increased access to these tests more than before.

The high heterogeneity in the overall prevalence seen in our study may be due to several reasons. As the result we considered post-hoc subgroup analyses by different characteristics such as sub- regions of Africa, publication year of study, study quality, and study design. Variations in the rate of GDM were observed in different sub-regions of Africa, the highest in Central Africa (20.4%) and the lowest in Northern Africa (7.57%). This discrepancy might be attributable to sociocultural, environmental, and economic factors, resulting in differences in accessing ANC services. These factors were also mentioned as one of the reasons for a high level of GDM in sub-Saharan Africa. Moreover, the sub-group analysis found GDM prevalence with publication year of studies a highest by 2016 (19.3%) and the lowest by 2015(8.8%), relating to the quality of study score low risk bias (13.5%), moderate risk bias(14.6%), and high risk of bias (13.8%) which were similarly observed. In the same way, studies conducted by cross sectional and prospective study design found that overall pooled prevalence of GDM were 10.14 and 19.1% respectively. However still significant heterogeneity was also found in sub group analyses and these differences between groups may not statistically be reliable as the CIs overlap. This was further augmented by further supplementary analysis that revealed non-significant group differences.

This review also assessed the association of GDM with overweight and obesity, those who had a macrocosmic baby, family history of diabetes mellitus, history of stillbirth, history of abortion or miscarriage, chronic hypertension, and previous history of GDM in Africa.

Pregnant women with obesity had increased risk of GDM than pregnant women with normal weight (OR = 3.51; 95% CI = 1.92, 6.40). The finding was consistent with those of the previous meta-analysis conducted in sub-Saharan Africa [9], US [62], the Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome Study (HAPO) [63], a systematic review and meta-analysis by Nelson SM et al. which revealed [64] pre-pregnancy BMI was more strongly associated with the risk for GDM. The possible reason could be GDM due to the reduction of insulin sensitivity among obese pregnancies. In other words, obesity-related insulin resistance inflates the normal glucose levels [64, 65]. Moreover, it might be because women with overweight or obesity might be exposed to a sedentary life, again they became obese due to inactive in their daily activities. The present result has public health implications given the increasing prevalence of obesity; we can also expect a further rise in the prevalence of GDM in the coming years.

The study showed that having a family history of diabetes mellitus was a significant factor for an increased risk for GDM (OR = 2.69; 95% CI = 1.84, 3.91). The finding was consistent with Carr DB et al. study in the US [66], and Iran [67, 68]. This is utterly known that if the beta cell is not functional genetically, hyper-glycaemia will occur linked with insulin resistant surely happen; this is especially true family suffering of type I diabetes mellitus and due to the familial tendency of insulin secretory defects [69].

The current meta-analysis also found that pregnant women with a previous history of GDM had fourteen times higher risk of developing GDM in the future pregnancy (OR = 14.16; 95% CI = 2.39, 84.08). This finding was in line with findings from Colorado [70], a systematic review conducted by Catherine Kim et al. [71]. The recurring nature of GDM because of the shared risk factor in repeated pregnancies [72]. Similarly, this study also found that the odds of GDM were 2.5 times higher in women with chronic hypertension (OR = 2.49; 95% CI = 1.35, 4.59). This finding agrees with findings from Canada and India [66, 73, 74]. This might be due to the potential complication like obesity, inflammation, oxidative stress, insulin resistance, and mental stress owing to chronic hypertension could lead to GDM [75].

The current meta-analysis also found that pregnant women who were ever had macrocosmic (large sized) baby was more likely to develop GDM compared to their counterparts. Nearly similar finding observed by random effect model (OR = 2.81; 95% CI = 1.52, 5.21) and by added one study in the trim and fill analysis (OR = 2.23; 95% CI = 1.12, 4.44). The finding was consistent with the HAPO study [76], a cohort study in Nova Scotia Atlee Perinatal Database (NSAPD) in Canada by Stephanie et al. [77]. This could be due because large infant birth weight during index pregnancy may be indicative of poor control and/or poor maternal diet or may reflect GDM severity, which might predispose the women to recurrent GDM [77].

Moreover, women with a history of stillbirth had three times (OR = 2.92; 95% CI = 1.23, 6.93) higher risk of developing GDM in future pregnancies. The finding was in line with a review conducted in sub-Saharan Africa by Mwanri et al. [9]. Similarly, women with a history of miscarriage or abortion had two folds of higher risk for developing GDM (OR = 2.21; 95% CI = 1.68, 2.92). This finding agrees with findings from Australia [78] and China [79]. The risk of stillbirth and abortion or miscarriage during the index pregnancy might be indicative of women with poor blood glucose control and various endocrine system problems which affect the normal metabolism of insulin, which might then predispose women to recurrent or risk for GDM.

This review has certain strengths and limitations. This resulted the pooled prevalence of GDM noted using the updated and current international diagnostic criteria and using a similar definition of GDM allows to determine the current and true prevalence of GDM in Africa. Subgroup analysis (sub-regions of Africa, publication year of studies, risk of bias and study design) and assessed multiple factors were considered as the strength of our study. However, our meta-analysis has limitations, such as the presence of significant heterogeneity, only studies published in English included, did not used MeSH terms in the search strategy, and did not investigate grey literature. Hence the result of this meta-analysis had significant heterogeneity and there was some overlap of CIs in the result of sub group analysis. Therefore, some estimates could be influenced by an interaction between groups. Although, most of the articles included in this review assessed the demographic characteristics, medical factors, and obstetric factors, there were limited studies which presented the association of other variables like residence, dietary diversity, substance abuse, and physical activity issues with GDM. Future review studies which elucidate the association of GDM with other factors listed above. Additionally, this review didn’t include qualitative studies on the reasons for GDM.

Conclusions

The prevalence of GDM was found to be high in Africa. Wide differences in the prevalence of GDM were observed across the different sub-regions of Africa, the highest being in Central Africa and the East Africa regions. The prevalence was high in the sub-Sharan Africa region. The associated factors for GDM include women with obesity and overweight, previous fetal macrosomia, family history of diabetes, history of abortion/miscarriage, history of stillbirth, chronic hypertension, and history of previous GDM. Therefore, considering the trend towards the epidemic of obesity, a substantial burden of GDM is anticipated in Africa. Preventing overweighed and obese, giving due attention for women having family history of DM, poor obstetric history and women with history of previous GDM are strongly recommended to mitigate the burden. It is essential to further identify effective modifiable factors, and early screening and diagnosis of GDM for better management and to halt the burden.

Additional file

Supplementary files on original funnel plots and funnel plots improved by the trim and fill method. (DOCX 162 kb)

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the African Union Commission (AU) for funding this study and the University of Ibadan (UI) for hosting the program. We would also like to acknowledge the teaching and non-teaching staff of Pan African University Life and Earth Science Institute (PAULESI), UI, Nigeria and to all authors of studies included in this review.

Abbreviations

- BMI

Body mass index

- CI

Confidence interval

- CM

Centi meter

- DM

Diabetes mellitus

- FBG

Fasting blood glucose

- GDM

Gestational diabetes mellitus

- HAPO

Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome

- I2

I-squared statistic

- IADPSG

International Association of the Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Group

- IDF

International Diabetes Federation

- IGT

Impaired glucose tolerance

- LMIC

Low and Middle-Income Countries

- NCD

Non-Communicable Diseases

- OGTT

Oral glucose tolerance test

- OR

Odds Ratio

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analyses guidelines

- UN

United Nations

- US

United States

- WHO

World Health Organization

Appendix 1

Table 4.

Search terms used for final search 26 November, 2018

| Data based used | Search term | Items found | Date and Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed | (((diabetes OR hyperglycemia OR "glucose intolerance" OR "gestational diabetes" OR "impaired glucose tolerance" OR "impaired fasting glucose" OR "diabetes mellitus" OR "postprandial glucose tolerance" OR "glucose tolerance")) AND (("physical inactivity" OR "sedentary life style" OR "physical activity" OR "previous foetal macrosmia" OR "pervious unexplained still birth" OR "previous still birth" OR "family history of type 2 diabetes mellitus" OR "high mid upper arm circumference" OR obesity OR overweight OR "body mass index" OR "previous gestational diabetes mellitus" OR age OR "advanced maternal age" OR "previous pregnancies" OR "polyhydramnios" OR glycosuria OR "depression" OR "dietary diversity" OR HIV OR residence OR "Urban residence" OR "rural residence")) AND (((pregnan*) OR gestation*) OR Gravid*) OR gestational diabetes AND ((Africa* OR east Africa* OR north Africa* OR central Africa* OR Angola* OR algeria OR Benin* OR Botswan* OR burkina faso OR Burkinabe* OR burundi OR Cameroon* OR cape Verde* OR central african republic OR Chad* OR Comor* OR Congo* OR congo, democratic republic of OR cote d'ivoire OR ivory coast OR ivorian OR Djibouti* OR Dominica* OR egypt OR equatorial guinea OR Ecuador* OR Guinea* OR Eritrea* OR Ethiopia* OR Gabon* OR Gambia* OR Ghana* OR guinea OR guinea-bissau OR Kenya* OR lesotho OR Liberia* OR libya OR Madagascar* OR Malawi* OR Mali* OR Mauritania* OR mauritius OR mozambique OR morocco OR Namibia* OR Niger* OR nigeria OR Rwanda* OR sao tome and principe OR Senegal* OR seychelles OR sierra Leone* OR Somalia* OR south Africa* OR south sudan OR Sudan* OR swaziland OR swazi OR Tanzania* OR Togo* OR Tonga* OR Uganda* OR Zambia* OR tunisia OR Zimbabwe*)) AND human NOT animal | 1378 |

17/11/2018 Time 11:57 PM |

| Scopus | ( ALL ( diabetes OR hyperglycemia OR "glucose intolerance" OR "gestational diabetes" OR "impaired glucose tolerance" OR "impaired fasting glucose" ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "diabetes mellitus" OR "postprandial glucose tolerance" OR "glucose tolerance" ) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "physical inactivity" OR "sedentary life style" OR macrosmia OR "previous still birth" OR "family history of diabetes mellitus" ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "high mid upper arm circumference" OR obesity OR overweight OR "body mass index" OR "previous gestational diabetes mellitus" OR " maternal age" OR depression OR "dietary diversity" OR residence ) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ( pregnan* OR gestation* OR gravid* OR "gestational diabetes" ) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ( africa* OR east AND africa* OR north AND africa* OR central AND africa ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( angola* OR algeria OR benin* OR botswan* OR burkina AND faso OR burkinabe* OR burundi ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( cameroon* OR cape AND verde* OR 'central AND african AND republic' OR chad* OR comor* OR congo* OR congo, AND democratic AND republic AND of OR cote AND d'ivoire OR ivory AND coast OR ivorian ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( djibouti* OR dominica* OR egypt OR equatorial AND guinea OR ecuador* OR guinea* OR eritrea* OR ethiopia* ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( gabon* OR gambia* OR ghana* OR guinea OR guinea-bissau OR kenya* OR lesotho OR liberia* OR libya OR madagascar* OR malawi* OR mali* OR mauritania* OR mauritius OR mozambique OR morocco ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( namibia* OR niger* OR nigeria OR rwanda* OR sao AND tome AND principe OR senegal* OR seychelles OR sierra AND leone* OR somalia* OR south AND africa ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( south AND sudan OR sudan* OR swaziland OR swazi OR tanzania* OR togo* OR tonga* OR uganda* OR zambia* OR tunisia OR zimbabwe* ) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ( human ) ) | 543 |

17/11/2018 Time 12:08 AM |

| Google scholar | “ Gestational diabetes mellitus OR Hyperglycemia ” AND “ Name each African countries ” | 854 |

26/11/2018 Time 4:22 pm |

| Other sources | “gestational diabetes” and Africa; “impaired fasting glucose” and pregnancy and Africa; diabetes and pregnancy and Africa; “impaired glucose tolerance” and pregnancy and Africa; “gestational diabetes” and “African countries.” | 53 | 26 /11/2018 |

Appendix 2

Table 5.

Risk of bias assessment tool: Adapted from the Risk of Bias Tool for Prevalence Studies developed by [33] Name of the author and year of publication

| Risk of Bias Item | Answer: Yes (Low Risk) or No (High risk) |

|---|---|

| External Validity | |

| 1. Was the study target population a close representation of the national pregnant population in relation to relevant variables? | |

| 2. Was the sampling frame a true or close representation of the target population? (risk factors used appropriate?) | |

| 3. Was some form of random selection used to select the sample, OR, was a census undertaken? | |

| 4. Was the likelihood of non-participation bias minimal? (i.e. ≥75% response rate)? | |

| Internal Validity | |

| 5. Were data collected directly from the subjects? (as opposed to medical records) | |

| 6. Were acceptable diagnostic criteria for GDM used? | |

| 7. Was a reliable and accepted method of testing for blood glucose utilised? | |

| 8. Was the same mode of data collection used for all subjects? | |

| 9. Was GDM tested for within the advised gestational period of 24–28 weeks? | |

| 10. Were the numerator(s) and denominator(s) for the calculation of the prevalence of GDM appropriate? | |

| Summary item on the overall risk of study bias | |

|

A. LOW RISK OF BIAS: 8 or more ‘yes’ answers. Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate. B. MODERATE RISK OF BIAS: 6 to 7 ‘yes’ answers. Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate and may change the estimate. C. HIGH RISK OF BIAS: 5 or fewer ‘yes’ answers. Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate and is likely to change the estimate. |

Table 6.

Summary characteristics of studies in the meta-analysis to show assessment of risk of bias of the included studies the prevalence Gestational diabetes mellitus in Africa, 2013–2018

| S.N | Author, year of publication | Sample of pregnant women representative? | Sampling Frame representative? |

Random or census selection? | Response rate ≥75%? | Data from subjects? | Acceptable diagnostic criteria? | Reliable testing for BG? | Same method for all? | Proper gestational age GDM test? | Proper calculation prevalence | Total ‘Yes’ | Overall risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Niyibizi et al., 2016 [13] | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | 5 | High |

| 2 | Sagheer and Hamdi , 2018 [56] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 9 | Low |

| 3 | Ogoudjobi et al., 2017 [44] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 9 | Low |

| 4 | Oppong et al., 2015 [45] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 9 | Low |

| 5 | Oriji et.al., 2017 [41] | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8 | Low |

| 6 | Agbozo et al., 2018 [39] | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | 9 | High |

| 7 | Nakabuye et al., 2017 [47] | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | 6 | Moderate |

| 8 | Macaulay et al., 2018 [54] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 9 | Low |

| 9 | Abbey and Kasso , 2018 [40] | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | 4 | High |

| 10 | Njete et al., 2018 [48] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 10 | Low |

| 11 | Pastakia et al., 2017 [49] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 9 | Low |

| 12 | Olagbuji et al., 2017 [42] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | 8 | Low |

| 13 | Munang et al., 2017 [51] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | 8 | Low |

| 14 | Jao et al., 2013 [53] | No | No | Yes | NR | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 | Moderate |

| 15 | Djomhou et al., 2016 [52] | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | 4 | High |

| 16 | Olagbuji et al., 2015 [17] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 10 | Low |

| 17 | Ogu et al., 2017 [43] | No | No | No | NR | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 4 | High |

| 18 | Khalil et al, 2017 [57] | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 7 | Moderate |

| 19 | Adams and Rheeder, 2017 [15] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 9 | Low |

| 20 | Adoyo et al., 2016 [50] | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | NR | NR | NR | Yes | Yes | 4 | High |

| 21 | Mwanri et al., 2014 [11] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 8 | Low |

| 22 | Asare-Anane et al., 2014 [46] | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | NR | 6 | Moderate |

| 23 | Mathilda et al.,2017 [55] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | 4 | High |

GDM Gestational diabetes mellitus, NR Not Reported

Authors’ contributions

AAM was involved in the conceptualization, design, selection of articles, study quality assessment, data extraction, statistical analysis and writing the first draft of the manuscript. OO and YKG were variously involved in the conceptualization, study quality assessment, statistical analysis and editing of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was sponsored by the Pan African University (PAU), a continental initiative of the African Union Commission (AU), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, as part of the Ph.D. program in Reproductive Health Sciences.

Availability of data and materials

All data pertaining to this study are contained and presented in this document.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declared that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Achenef Asmamaw Muche, Email: ashua2014@gmail.com.

Oladapo O. Olayemi, Email: oladapo.olayemi@yahoo.com

Yigzaw Kebede Gete, Email: gkyigzaw@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO). Diagnostic criteria and classification of hyperglycaemia first detected in pregnancy. 2013. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/85975/1/WHO_NMH_MND_13.2_eng.pdf. [PubMed]

- 2.American Diabetes Association (ADA) Classification and diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(Supplement 1):S8–S16. doi: 10.2337/dc15-S005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wojcicki JM. Maternal prepregnancy body mass index and initiation and duration of breastfeeding: a review of the literature. J Womens Health. 2011;20(3):341–347. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.International Diabetes Federation (IDF) Diabetes Atlas, 7th edn. Brussels: International Diabetes Federation; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiwani A, Marseille E, Lohse N, Damm P, Hod M, Kahn JG. Gestational diabetes mellitus: results from a survey of country prevalence and practices. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25(6):600–610. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2011.587921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogurtsova K, da Rocha FJ, Huang Y, Linnenkamp U, Guariguata L, Cho N, et al. IDF diabetes atlas: global estimates for the prevalence of diabetes for 2015 and 2040. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;128:40–50. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2017.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eades CE, Cameron DM, Evans JM. Prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus in Europe: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;129:173–181. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2017.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee KW, Ching SM, Ramachandran V, Yee A, Hoo FK, Chia YC, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of gestational diabetes mellitus in Asia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):494. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-2131-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mwanri AW, Kinabo J, Ramaiya K, Feskens EJ. Gestational diabetes mellitus in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review and metaregression on prevalence and risk factors. Tropical Med Int Health. 2015;20(8):983–1002. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu Y, Zhang C. Prevalence of gestational diabetes and risk of progression to type 2 diabetes: a global perspective. Curr Diabetes Rep. 2016;16(1):7. doi: 10.1007/s11892-015-0699-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mwanri AW, Kinabo J, Ramaiya K, Feskens EJ. Prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus in urban and rural Tanzania. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;103(1):71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuti M. A., Abbiyesuku F. M., Akinlade K. S., Akinosun O. M., Adedapo K. S., Adeleye J. O., Adesina O. A. Oral glucose tolerance testing outcomes among women at high risk for gestational diabetes mellitus. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2011;64(8):718–721. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2010.087098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Niyibizi JB, Safari F, Ahishakiye JB, Habimana JB, Mapira H, Mutuku NC. Gestational diabetes mellitus and its associated risk factors in pregnant women at selected health facilities in Kigali City, Rwanda. J Diabetes Mellitus. 2016;6(04):269. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seyoum B, Kiros K, Haileselase T, Leole A. Prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus in rural pregnant mothers in northern Ethiopia. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1999;46(3):247–251. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(99)00101-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adams S, Rheeder P. Screening for gestational diabetes mellitus in a south African population: prevalence, comparison of diagnostic criteria and the role of risk factors. S Afr Med J. 2017;107(6):523–527. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2017.v107i6.12043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lauring JR, Kunselman AR, Pauli JM, Repke JT, Ural SH. Comparison of healthcare utilization and outcomes by gestational diabetes diagnostic criteria. J Perinat Med. 2018;46(4):401–409. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2017-0076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olagbuji BN, Atiba AS, Olofinbiyi BA, Akintayo AA, Awoleke JO, Ade-Ojo IP, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for gestational diabetes using 1999, 2013 WHO and IADPSG criteria upon implementation of a universal one-step screening and diagnostic strategy in a sub-Saharan African population. Eur J Obstetrics Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2015;189:27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2015.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nguyen CL, Pham NM, Binns CW, Duong DV, Lee AH. Prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus in eastern and southeastern Asia: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Diabetes Res. 2018;2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Hartling L, Dryden DM, Guthrie A, Muise M, Vandermeer B, Aktary WM, et al. Screening and diagnosing gestational diabetes mellitus. Evid Rep Technol Assess. 2012;210:1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huvinen Emilia, Eriksson Johan G., Koivusalo Saila B., Grotenfelt Nora, Tiitinen Aila, Stach-Lempinen Beata, Rönö Kristiina. Heterogeneity of gestational diabetes (GDM) and long-term risk of diabetes and metabolic syndrome: findings from the RADIEL study follow-up. Acta Diabetologica. 2018;55(5):493–501. doi: 10.1007/s00592-018-1118-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coetzee EJ. Pregnancy and diabetes scenario around the world: Africa. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2009;104:S39–S41. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abubakar I, Tillmann T, Banerjee A. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;385(9963):117–171. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colagiuri S, Falavigna M, Agarwal MM, Boulvain M, Coetzee E, Hod M, et al. Strategies for implementing the WHO diagnostic criteria and classification of hyperglycaemia first detected in pregnancy. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;103(3):364–372. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diabetes IAo, Panel PSGC International association of diabetes and pregnancy study groups recommendations on the diagnosis and classification of hyperglycemia in pregnancy. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(3):676–682. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Diabetes Association (ADA) Standards of medical care in diabetes—2013. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(Supplement 1):S11–S66. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Macaulay S, Dunger DB, Norris SA. Gestational diabetes mellitus in Africa: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e97871. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Achenef Muche, Oladapo Olayemi, Yigzaw Gete. Prevalence and determinants of gestational diabetes mellitus in Africa based on the updated international diagnostic criteria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PROSPERO 2018 CRD42018116843 Available from: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?ID=CRD42018116843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.United Nations Statistics Division, “Geographical region and composition of each region,” January 2017, https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/.

- 30.Jenum AK, Mørkrid K, Sletner L, Vange S, Torper JL, Nakstad B, et al. Impact of ethnicity on gestational diabetes identified with the WHO and the modified International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups criteria: a population-based cohort study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2012;166(2):317–324. doi: 10.1530/EJE-11-0866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McIntyre HD, Colagiuri S, Roglic G, Hod M. Diagnosis of GDM: a suggested consensus. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;29(2):194–205. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2014.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, Blyth F, March L, Bain C, et al. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(9):934–939. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Begg Colin B., Mazumdar Madhuchhanda. Operating Characteristics of a Rank Correlation Test for Publication Bias. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):1088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duval S, Tweedie R. A nonparametric “trim and fill” method of accounting for publication bias in meta-analysis. J Am Stat Assoc. 2000;95(449):89–98. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Agbozo FAA, Narh C, Jahn A. Accuracy of glycosuria, random blood glucose and risk factors as selective screening tools for gestational diabetes mellitus in comparison with universal diagnosing. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2018;6(1):e000493. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2017-000493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abbey M, Kasso T. First trimester fasting blood glucose as a screening tool for diabetes mellitus in a teaching hospital setting in Nigeria. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oriji VK, Ojule JD, Fumudoh BO. Prediction of gestational diabetes mellitus in early pregnancy: is abdominal skin fold thickness 20 mm or more an independent risk predictor? J Biosci Med. 2017;5(11):13. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Olagbuji BN, Aderoba AK, Kayode OO, Awe CO, Akintan AL, Olagbuji YW. Accuracy of 50-g glucose challenge test to detect International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups criteria-defined hyperglycemia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2017;139(3):312–317. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ogu RN, John CO, Maduka O, Chinenye S. Screening for Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Findings from a Resource Limited Setting of Nigeria. Br J Med Med Res. 2017;20(11):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ogoudjobi OM, Sossa Jérôme C, Lokossou MSHS, Tshabu-Aguemon C, Kérékou A, Tandjiékpon E, Denakpo JL, Perrin R-X. Risk Factors of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in a Reference Maternal Health Care Centre in Southern Benin. Adv Diabetes Metab. 2017;5(4):53–58. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oppong SA, Ntumy MY, Amoakoh-Coleman M, Ogum-Alangea D, Modey-Amoah E. Gestational diabetes mellitus among women attending prenatal care at Korle-Bu teaching hospital, Accra, Ghana. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2015;131(3):246–250. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Asare-Anane H, Ofori ATBEK, Amanquah SD. Risk factors for gestational diabetes mellitus among Ghanaian women at the Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital. Risk. 2014;4(12):54–6.

- 47.Nakabuye B, Bahendeka S, Byaruhanga R. Prevalence of hyperglycaemia first detected during pregnancy and subsequent obstetric outcomes at St. Francis Hospital Nsambya. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10(1):174. doi: 10.1186/s13104-017-2493-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Njete H, John B, Mlay P, Mahande M, Msuya S. Prevalence, predictors and challenges of gestational diabetes mellitus screening among pregnant women in northern Tanzania. Tropical Med Int Health. 2018;23(2):236–242. doi: 10.1111/tmi.13018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pastakia SD, Njuguna B, Onyango BA, Washington S, Christoffersen-Deb A, Kosgei WK, et al. Prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus based on various screening strategies in western Kenya: a prospective comparison of point of care diagnostic methods. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):226. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1415-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Adoyo MA, Mbakaya C, Nyambati V, Kombe Y. Retrospective cohort study on risk factors for development of gestational diabetes among mothers attending antenatal clinics in Nairobi County. Pan Afr Med J. 2016;24:155. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2016.24.155.8093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Munang YN, Noubiap JJ, Danwang C, Sama JD, Azabji-Kenfack M, Mbanya JC, et al. Reproducibility of the 75 g oral glucose tolerance test for the diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus in a sub-Saharan African population. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10(1):622. doi: 10.1186/s13104-017-2944-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Djomhou M, Sobngwi E, Noubiap JJ, Essouma M, Nana P, Fomulu NJ. Maternal hyperglycemia during labor and related immediate post-partum maternal and perinatal outcomes at the Yaounde Central Hospital, Cameroon. J Health Popul Nutr. 2016;35(1):28. doi: 10.1186/s41043-016-0065-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jao J, Wong M, Van Dyke RB, Geffner M, Nshom E, Palmer D, et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus in HIV-infected and -uninfected pregnant women in Cameroon. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(9):e141–e142. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Macaulay S, Ngobeni M, Dunger DB, Norris SA. The prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus amongst black South African women is a public health concern. Diabetes Clin Pract. 2018;139:278–287. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2018.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mathilda Z, Doreen M, Augustine N, Maxwell M. Prevalence of diabetes in pregnancy at a tertiary care institution and associated perinatal outcomes. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sagheer GM, Hamdi L. Prevalence and risk factors for gestational diabetes mellitus according to the diabetes in pregnancy study group India in comparison to International Association of the Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups in El-Minya, Egypt. Egypt J Int Med. 2018;30(3):131. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Khalil NA, Fathy WM, Mahmoud NS. Screening for gestational diabetes among pregnant women attending a rural family health center- Menoufia governorate- Egypt. J Fam Med Health Care. 2017;3(1):6–11. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cosson E, Benbara A, Pharisien I, Nguyen MT, Revaux A, Lormeau B, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic performances over 9 years of a selective screening strategy for gestational diabetes mellitus in a cohort of 18,775 subjects. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(3):598–603. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hiéronimus S, Le JM. Relevance of gestational diabetes mellitus screening and comparison of selective with universal strategies. Diabetes Metab. 2010;36(6 Pt 2):575–586. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.DeSisto CL, Kim SY, Sharma AJ. Peer reviewed: prevalence estimates of gestational diabetes mellitus in the United States, pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system (prams), 2007–2010. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Chamberlain C, Joshy G, Li H, Oats J, Eades S, Banks E. The prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus among aboriginal and Torres Strait islander women in Australia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2015;31(3):234–247. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chu SY, Callaghan WM, Kim SY, Schmid CH, Lau J, England LJ, et al. Maternal obesity and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(8):2070–2076. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2559a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Catalano PM, McIntyre HD, Cruickshank JK, McCance DR, Dyer AR, Metzger BE, et al. The hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcome study: associations of GDM and obesity with pregnancy outcomes. Diabetes Care. 2012; DC_111790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Nelson SM, Matthews P, Poston L. Maternal metabolism and obesity: modifiable determinants of pregnancy outcome. Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16(3):255–275. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Huda SS, Brodie LE, Sattar N. Obesity in pregnancy: prevalence and metabolic consequences. Elsevier; Seminars in Fetal and Neonatal Medicine. 2010;15(2):70–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 66.Carr DB, Utzschneider KM, Hull RL, Tong J, Wallace TM, Kodama K, et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus increases the risk of cardiovascular disease in women with a family history of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(9):2078–2083. doi: 10.2337/dc05-2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Keshavarz M, Cheung NW, Babaee GR, Moghadam HK, Ajami ME, Shariati M. Gestational diabetes in Iran: incidence, risk factors and pregnancy outcomes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2005;69(3):279–286. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Garshasbi A, Faghihzadeh S, Naghizadeh MM, Ghavam M. Prevalence and risk factors for gestational diabetes mellitus in Tehran. J Fam Reprod Health. 2008;2(2):75–80. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ehrmann DA, Sturis J, Byrne MM, Karrison T, Rosenfield RL, Polonsky KS. Insulin secretory defects in polycystic ovary syndrome. Relationship to insulin sensitivity and family history of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest. 1995;96(1):520–527. doi: 10.1172/JCI118064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dabelea D, Snell-Bergeon JK, Hartsfield CL, Bischoff KJ, Hamman RF, McDuffie RS. Increasing prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) over time and by birth cohort: Kaiser Permanente of Colorado GDM screening program. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(3):579–584. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.3.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kim C., Berger D. K., Chamany S. Recurrence of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A systematic review. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(5):1314–1319. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Spong C, Guillermo L, Kuboshige J, Cabalum T. Recurrence of gestational diabetes mellitus: identification of risk factors. Am J Perinatol. 1998;15(01):29–33. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-993894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Williams MA, Qiu C, Dempsey JC, Luthy DA. Familial aggregation of type 2 diabetes and chronic hypertension in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. J Reprod Med. 2003;48(12):955–962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rajput R, Yadav Y, Nanda S, Rajput M. Prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus & associated risk factors at a tertiary care hospital in Haryana. Indian J Med Res. 2013;137(4):728. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cheung BM, Li C. Diabetes and hypertension: is there a common metabolic pathway? Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2012;14(2):160–166. doi: 10.1007/s11883-012-0227-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Boney CM, Verma A, Tucker R, Vohr BR. Metabolic syndrome in childhood: association with birth weight, maternal obesity, and gestational diabetes mellitus. Pediatrics. 2005;115(3):e290–e2e6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.MacNeill S, Dodds L, Hamilton DC, Armson BA, VandenHof M. Rates and risk factors for recurrence of gestational diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(4):659–662. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.4.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kirke AB, Evans SF, Walters B. Gestational diabetes in a rural, regional centre in south Western Australia: predictors of risk. Rural Remote Health. 2014;14(3):1–9. [PubMed]

- 79.Yang H, Wei Y, Gao X, Xu X, Fan L, He J, et al. Risk factors for gestational diabetes mellitus in Chinese women—a prospective study of 16 286 pregnant women in China. Diabet Med. 2009;26(11):1099–1104. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary files on original funnel plots and funnel plots improved by the trim and fill method. (DOCX 162 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All data pertaining to this study are contained and presented in this document.