Abstract

Background

Magnifying Narrow Band Imaging (NBI) during colonoscopy is a reliable method for differential and depth diagnoses of colorectal lesions. This study examined the diagnostic yield of magnifying NBI based on the Japan NBI Expert Team (JNET) classification in a clinical setting using a large-scale clinical practice database. Types 1, 2A, 2B and 3 correspond to the histopathological classifications of hyperplastic polyp/sessile-serrated polyp, low-grade intramucosal neoplasia, high-grade intramucosal neoplasia/shallow submucosal invasive cancer, and deep submucosal invasive cancer, respectively.

Methods

The prospective records of colonoscopy reports and pathological data of 1558 consecutive superficial colorectal lesions removed by colonoscopy were retrospectively analysed. After excluding 156 lesions, the documented JNET classifications of the remaining 1402 colorectal lesions were analysed. Diagnostic yield was analysed and also compared between expert endoscopists and nonexpert endoscopists.

Results

The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV) and accuracy were respectively 75%, 96%, 74%, 96% and 93% for type 1; 91%, 70%, 92%, 67% and 87% for type 2A; 42%, 95%, 26%, 98% and 93% for type 2B; and 35%, 100%, 93%, 98% and 98% for type 3. Nonexpert and expert endoscopists alike had specificity, NPV and accuracy >90% for types 1, 2B and 3, and a sensitivity and PPV >90% for type 2A. Type 2B had a low sensitivity of 42% because it included various histological features.

Conclusions

The JNET classification proved useful in a clinical setting both for expert and nonexpert endoscopists, as was expected from the original JNET definition, but type 2B requires further investigation using pit pattern diagnosis.

Keywords: Colorectal neoplasms, endoscopic diagnosis, Japan NBI Expert Team (JNET) classification, magnifying NBI, Narrow Band Imaging (NBI)

Key summary

- What is the established knowledge?

- Magnifying Narrow Band Imaging (NBI) during colonoscopy is a reliable method for differential and depth diagnoses of colorectal lesions.

- A unified magnifying NBI classification called the Japan NBI Expert Team (JNET) classification was developed.

- If a lesion is classified as JNET type 2B, pit pattern diagnosis should be used as an adjunct for depth diagnosis.

- What are the new findings of this study?

- This study demonstrates the high diagnostic performance of the JNET classification in a clinical setting. Accuracy of >87% is achieved in differentiating neoplastic and non-neoplastic lesions, and in diagnosing low-grade intramucosal neoplasia, high-grade intramucosal neoplasia/shallow submucosal invasive cancer, and deep submucosal invasive cancer.

- The JNET classification proved useful in a clinical setting both for expert and non-expert endoscopists.

Introduction

Most colorectal cancers arise from preexisting adenomatous polyps following the adenoma–carcinoma sequence.1,2 There is evidence that the removal of colorectal adenomas may reduce the risk of future colorectal cancer.3 If the diagnosis of neoplastic polyps removed at colonoscopy is inaccurate, it can lead to additional unnecessary polypectomies in clinical practice, giving rise to potential negative consequences for patients and higher medical costs.

Narrow Band Imaging (NBI, Olympus, Inc, Tokyo, Japan) was developed in 1999 and is an innovative optical technology providing unique images that emphasise the surface and vessel patterns of the lesion. Magnifying NBI, in particular, is a reliable method for differentiating neoplastic from non-neoplastic lesions.4 Several magnifying NBI classifications for optical diagnoses of neoplastic and non-neoplastic lesions have been developed.5–10 Recently, a unified magnifying NBI classification called the Japan NBI Expert Team (JNET) classification was developed.11 The aim of this study was to clarify the diagnostic accuracy of the JNET classification using large-scale clinical practice data.

Methods

Patients and images

This retrospective, single-centre observational study involved 1558 consecutive pathologically diagnosed superficial colorectal lesions removed by endoscopy at the National Cancer Center Hospital, Tokyo, Japan, between April and December 2015 (Figure 1). In our institution, clinically diagnosed adenomas, sessile-serrated adenoma/polyps, traditional serrated adenomas, high-grade dysplasia, and shallow submucosal (SM) invasive cancer are endoscopically resected. We do not resect hyperplastic polyps <10 mm located in the rectum and sigmoid colon. JNET classifications based on endoscopy reports were prospectively collected and stored in a database. Of the 1558 lesions, 156 lesions were excluded because of JNET findings not being recorded, recurrent lesions, patients with a history of chemotherapy for colorectal cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, SM tumour, pathologically diagnosed inflamed colon mucosa, inflammatory polyp, lymphoma, squamous cell carcinoma, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, granulation tissue, or an insufficient specimen for diagnosis. Ultimately, 1402 colorectal lesions were used for analysis. All images were obtained with a magnifying colonoscope (CF-H260AZI, PCF-260AZI, CF-HQ290ZI, or PCF-H290AZI; Olympus Optical Co, Tokyo, Japan) with up to a 100 times magnification combined with a standard video processor (EVIS LUCERA ELITE CV-290, Olympus, Inc, Tokyo, Japan) and NBI system (Olympus, Inc).

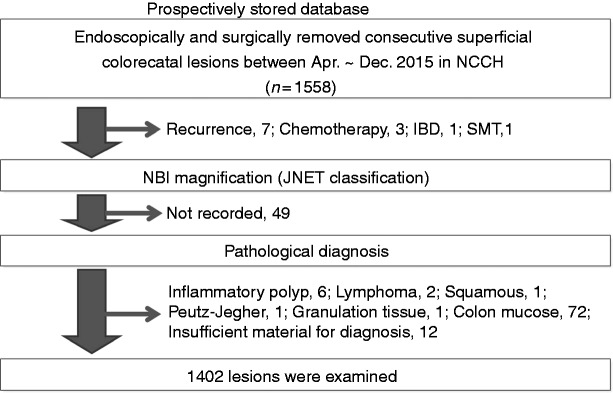

Figure 1.

Study flow.

IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; JNET: Japan NBI Expert Team; NBI: Narrow Band Imaging; NCCH: National Cancer Center Hospital; SMT: submucosal tumour.

This study was approved by the ethics committee of our institution (approval number 2016-245), and its protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in a priori approval by the institution’s human research committee. Informed consent was obtained from each patient included in the study.

Endoscopic diagnosis using JNET classification

The JNET classification was used as originally reported.11 Briefly, the JNET classification consists of four categories, types 1, 2A, 2B and 3, based on vessel and surface pattern findings. Vessel patterns of types 1, 2A, 2B and 3 are defined as invisible, regular calibre/regular distribution (meshed/spiral pattern), variable calibre/irregular distribution, and loose vessel areas/interruption of thick vessels, respectively. Surface patterns of types 1, 2A, 2B and 3 are defined as regular dark or white spots/similar to surrounding normal mucosa, regular (tubular/branched/papillary), irregular or obscure, and amorphous areas, respectively (Figure 2). JNET types 1, 2A, 2B and 3 correspond to the histopathological classifications of hyperplastic polyp/SSP, low-grade intramucosal neoplasia (LGN), high-grade intramucosal neoplasia (HGN)/shallow SM invasive cancer, and deep SM invasive cancer, respectively. It is important to note that JNET type 2B mainly corresponds to HGN/shallow SM invasive cancer but sometimes includes deep SM invasive cancer. Therefore, pit pattern diagnosis using crystal-violet is still the gold standard for JNET type 2B lesions.12 We investigated pit pattern diagnosis for lesions misclassified by the JNET classification.

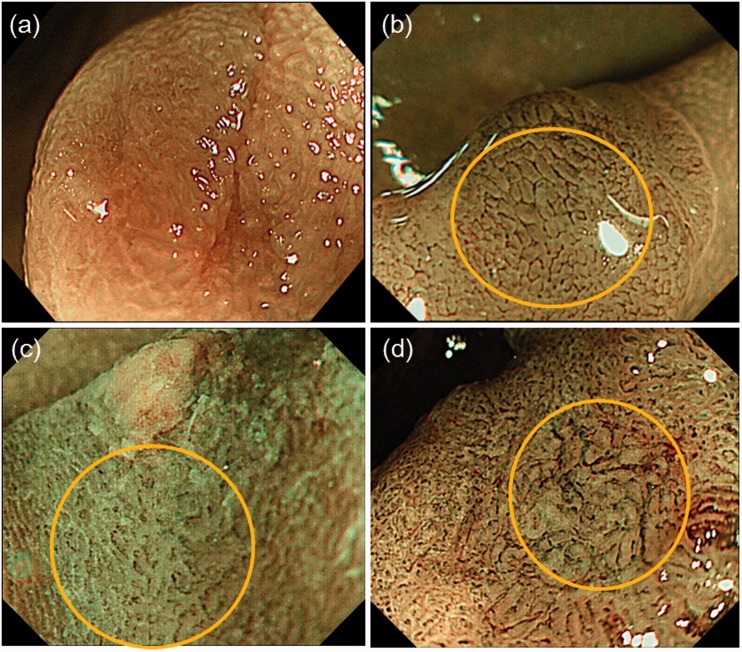

Figure 2.

Representative example of the Japan NBI Expert Team classification. (a) Invisible vessel pattern and white spots (type 1); (b) regular vessel and surface patterns (type 2A); (c) irregular vessel and surface patterns (type 2B); (d) nearly avascular or loose vascular areas (type 3). NBI: Narrow Band Imaging.

Histopathological evaluation

Resected specimens were fixed in formalin and serially sectioned at 2–3 mm intervals. Histological classification was performed using the Japanese Classification of Colorectal Carcinoma.13 Depth of tumour invasion was classified as adenoma, intramucosal cancer (Tis (M)), SM superficial invasive cancer (T1a (SM1), <1000 µm of SM tumour invasion) or SM deep invasive cancer (T1b (SM2), ≥1000 µm). The depth of SM tumour invasion was measured from the lower border of the muscularis mucosae to the deepest area of tumour invasion. When it was not possible to identify the depth of invasion in this way, depth was measured from the surface of the tumour using the Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum guidelines.14

HGN in Europe and Tis/early cancer in Japan are mostly the same lesions. Tis/early cancer in the Japanese classification is for the most part equivalent to Category 4 of the Vienna classification.

Statistical analysis

We analysed the diagnostic yield (sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV) and accuracy) of the JNET classification for each type (types 1, 2A, 2B and 3). The diagnostic yield was compared between expert and nonexpert endoscopists. An expert endoscopist was defined as having performed ≥5000 colonoscopies, and a nonexpert endoscopist was defined as having performed <5000 colonoscopies. We further analysed the diagnostic yield stratified by lesion size.

The Fisher exact test was used to compare outcomes between expert and nonexpert endoscopists. Statistical analysis was performed using R version 3.5.0 (R Core Team (2018). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, http://www.R-project.org/). P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical tests were two sided, and the alpha level was set at 0.05.

Results

Clinicopathological features of colorectal lesions

Clinicopathological data are summarised in Table 1. The median lesion size was 6 mm (interquartile range, 4–10). A total of 807 (58%) lesions were in the proximal colon, 455 (32%) lesions were in the distal colon and 140 (10%) lesions were in the rectum. Pathologically, we identified 185 (13%) non-neoplastic lesions (hyperplastic polyp, sessile-serrated adenoma/polyp) and 1217 (87%) neoplastic lesions (traditional serrated adenoma, tubular adenoma, tubulovillous adenoma and cancer).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| No. of patients | 750 |

| No. of lesions | 1402 |

| Gender, male (%) | 961 (69%) |

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 68 (61–75) |

| Size, mm, median (IQR) | 6 (4–10) |

| Location | |

| Proximal colon | 807 (58%) |

| Distal colon | 455 (32%) |

| RS and rectum | 140 (10%) |

| Macroscopic typea | |

| Ip | 69 (5%) |

| Is, Is+IIc | 510 (36%) |

| IIa, IIa+IIc | 651 (46%) |

| IIb, IIc | 8 (1%) |

| LST-G | 67 (5%) |

| LST-NG | 97 (6%) |

| Treatment procedure | |

| Cold forceps polypectomy | 255 (18%) |

| Snare polypectomy | 594 (42%) |

| EMR (including EMR + OPE) | 411 (29%) (6, 0.4%) |

| PEMR | 35 (2%) |

| ESD (including ESD + OPE) | 83 (6%) (11, 1%) |

| OPE | 24 (2%) |

| Pathological diagnosis | |

| Non-neoplastic lesions | |

| Hyperplastic polyp | 72 (5%) |

| Sessile-serrated adenoma/polyp | 113 (8%) |

| Neoplastic lesions | |

| TSA | 10 (1%) |

| Tubular adenoma | 1001 (71%) |

| Tubulovillous adenoma | 27 (2%) |

| Tis (M) | 124 (9%) |

| T1a (SM, <1000 mm) | 15 (1%) |

| T1b (SM, ≥1000 mm) | 40 (3%) |

IQR: interquartile range; LST-G: laterally spreading tumour granular type; LST-NG: laterally spreading tumour nongranular type; EMR: endoscopic mucosal resection; ESD: endoscopic submucosal dissection; OPE: operation; PEMR: piecemeal endoscopic mucosal resection; RS: rectum sarcoma; SM: submucosal invasive cancer; TSA: traditional serrated adenoma.

Diagnostic yield of JNET classification

The PPV of each type of JNET classification based on the pathological diagnosis presented in Table 2 was 74% (139/187), 92% (1026/1110), 26% (23/90) and 93% (14/15), for types 1, 2A, 2B and 3, respectively. Table 3 shows the details of the diagnostic yield of the JNET classification and a comparison between expert and nonexpert endoscopists. For JNET type 1, the sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV and accuracy of differentiating neoplastic from non-neoplastic lesions were 75% (139/185), 96% (1169/1217), 74% (139/187), 96% (1169/1215) and 93% (1308/1402), respectively. When comparing expert and nonexpert endoscopists, the sensitivity of JNET type 1 was clinically higher for expert endoscopists (p = 0.09). Specificity was significantly higher for nonexpert endoscopists. For JNET type 2A, the sensitivity, PPV and accuracy were significantly higher for nonexpert endoscopists. There was no significant difference between expert and nonexpert endoscopists for JNET types 2B or 3. The specificity of JNET type 3 for deep SM invasive cancer was 100% (1361/1362) both for expert and nonexpert endoscopists. When type 2B included HGN to deep SM invasive cancer, the sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV and accuracy for differentiating HGN from deep SM invasive cancer were 44% (42/95), 96% (1259/1307), 47% (42/90), 96% (1259/1312) and 93% (1375/1402), respectively.

Table 2.

Diagnostic PPV of JNET classification.

| Hyperplastic polyp, SSA/P (n = 185) | Adenoma ∼ Tis (LGN) (n = 1122) | Tis (HGN) ∼ T1a (n = 55) | T1b (n = 40) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type 1 | 74% (139/187) | 26% (48/187) | 0% (0/187) | 0% (0/187) |

| Type 2A | 4% (46/1110) | 92% (1026/1110) | 3% (31/1110) | 1% (7/1110) |

| Type 2B | 0% (0/90) | 53% (48/90) | 26% (23/90) | 21% (19/90) |

| Type 3 | 0% (0/15) | 0% (0/15) | 7% (1/15) | 93% (14/15) |

HGN: high-grade intramucosal neoplasia; JNET: Japan NBI Expert Team; LGN: low-grade intramucosal neoplasia; NBI: Narrow Band Imaging; PPV: positive predictive value; SSA/P: sessile-serrated adenoma/polyp.

Table 3.

Diagnostic yield of JNET classification.

| Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Accuracy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type 1 (Non-neoplastic vs neoplastic) | |||||

| Expert | 79% (101/128) | 95% (701/739) | 73% (101/139) | 96% (701/728) | 93% (802/867) |

| Nonexpert | 67% (38/57) | 98% (468/478)a | 79% (38/48) | 96% (468/487) | 95% (506/535) |

| Combined | 75% (139/185) | 96% (1169/1217) | 74% (139/187) | 96% (1169/1215) | 93% (1308/1402) |

| Type 2A (LGN vs others) | |||||

| Expert | 90% (600/669) | 70% (139/198) | 91% (600/659) | 67% (139/208) | 85% (739/867) |

| Nonexpert | 94% (426/453)a | 70% (57/82) | 94% (426/451)a | 68% (57/84) | 90% (483/535)a |

| Combined | 91% (1026/1122) | 70% (196/280) | 92% (1026/1110) | 67% (196/292) | 87% (1222/1402) |

| Type 2B (HGN and shallow submucosal invasive cancer vs others) | |||||

| Expert | 40% (17/42) | 95% (785/825) | 30% (17/57) | 97% (785/810) | 93% (802/867) |

| Nonexpert | 46% (6/13) | 95% (495/522) | 18% (6/33) | 99% (495/502) | 94% (501/535) |

| Combined | 42% (23/55) | 95% (1280/1347) | 26% (23/90) | 98% (1280/1312) | 93% (1303/1402) |

| Type 3 (Deep submucosal invasive cancer vs others) | |||||

| Expert | 43% (12/28) | 100% (839/839) | 100% (12/12) | 98% (839/855) | 98% (851/867) |

| Nonexpert | 17% (2/12) | 100% (522/523) | 67% (2/3) | 98% (522/532) | 98% (524/535) |

| Combined | 35% (14/40) | 100% (1361/1362) | 93% (14/15) | 98% (1361/1387) | 98% (1375/1402) |

| Reference diagnostic yield of Type 2B including HGN, shallow and deep submucosal invasive cancer | |||||

| Combined | 44% (42/95) | 96% (1259/1307) | 47% (42/90) | 96% (1259/1312) | 93% (1301/1402) |

HGN: high-grade intramucosal neoplasia; JNET: Japan NBI Expert Team; LGN: low-grade intramucosal neoplasia; NBI: Narrow Band Imaging; NPV: negative predictive value; PPV: positive predictive value.

aP < 0.05 comparison between expert and nonexpert.

Table 4 shows the diagnostic yield of JNET type 1 stratified by lesion size (1–5 mm, 6–9 mm, ≥10 mm). The sensitivity and PPV were 57% (43/75) and 62% (43/69) for 1 to 5 mm lesions and 94% (65/69), 89% (65/73) for ≥10 mm lesions, respectively. Furthermore, there was a significant difference in specificity for <10 mm lesions between expert and nonexpert endoscopists.

Table 4.

Diagnostic yield of JNET type 1 stratified by size.

| Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Accuracy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 ∼ 5 mm | |||||

| Expert | 57% (25/44) | 94% (302/322) | 56% (25/45) | 94% (302/321) | 89% (327/366) |

| Nonexpert | 58% (18/31) | 98% (257/263)a | 75% (18/24) | 95% (257/270) | 94% (275/294) |

| Combined | 57% (43/75) | 96% (559/585) | 62% (43/69) | 95% (559/591) | 91% (602/660) |

| 6 ∼ 9 mm | |||||

| Expert | 81% (26/32) | 92% (130/142) | 68% (26/38) | 96% (130/136) | 90% (156/174) |

| Nonexpert | 60% (5/9) | 99% (104/106)a | 86% (5/7) | 96% (104/108) | 96% (109/115) |

| Combined | 76% (31/41) | 94% (234/248) | 69% (31/45) | 96% (234/244) | 92% (255/289) |

| ≥10 mm | |||||

| Expert | 96% (50/52) | 98% (269/275) | 89% (50/56) | 99% (269/271) | 98% (319/327) |

| Nonexpert | 88% (15/17) | 98% (107/109) | 88% (15/17) | 98% (107/109) | 97% (122/126) |

| Combined | 94% (65/69) | 98% (376/384) | 89% (65/73) | 99% (376/380) | 97% (441/453) |

JNET: Japan NBI Expert Team; NBI: Narrow Band Imaging; NPV: negative predictive value; PPV: positive predictive value.

aP < 0.05 comparison between expert and nonexpert

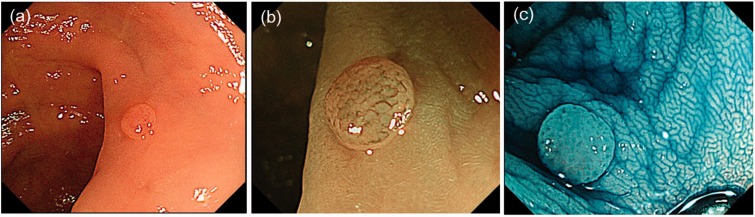

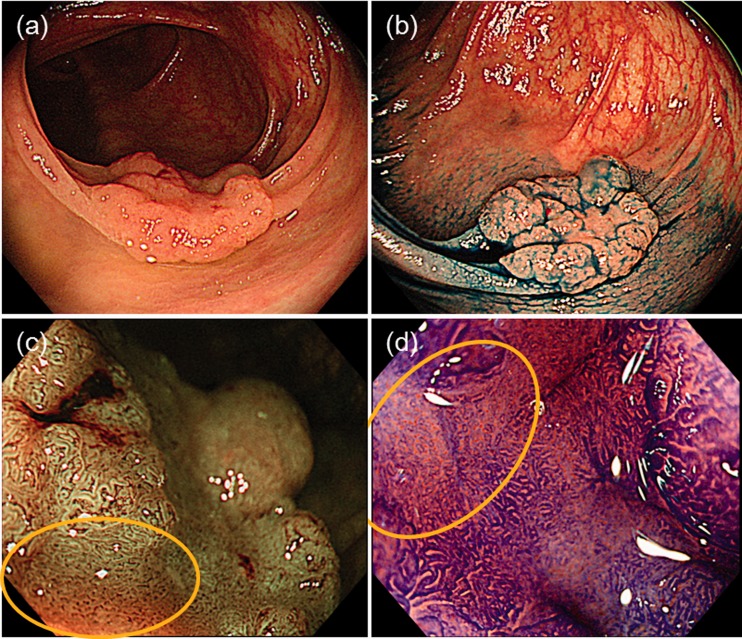

Table 5 shows lesions that were misclassified by the JNET classification. In total, 48 neoplastic lesions were evaluated as JNET type 1; polyps were small, at 5 mm (range, 3–6 mm), and approximately half the lesions were in the right colon and were macroscopically type 0–IIa (Figure 3). However, approximately half were correctly diagnosed as neoplastic lesions when using pit pattern diagnosis. There were 48 lesions of adenoma-Tis (LGN) that were evaluated as JNET type 2B. Approximately half the lesions were in the right colon and were macroscopically 0–IIa and of the laterally spreading tumour, nongranular type. Almost all cases were correctly diagnosed when using pit pattern diagnosis, and 31 lesions were Tis (HGN) to T1a but were evaluated as JNET type 2A. Lesions were >20 mm, and 77% (24/31) were protruding lesions (Ip, Is, Is+IIc, LST-G). Of these lesions, only 25% (8/31) showed a VI pit pattern. There were 19 T1b lesions evaluated as JNET type 2B, and approximately 60% (11/19) were correctly diagnosed using pit pattern diagnosis (Figure 4).

Table 5.

Representative lesions misclassified by JNET classification.

| Neoplastic | Adenoma | Tis (HGN) | Tis (HGN) | T1b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∼Tis (LGN) | ∼T1a | ||||

| JNET type | Type 1 | Type 2B | Type 2A | Type 3 | Type 2B |

| No. of lesions | 48 | 48 | 31 | 1 | 19 |

| Size (mm, median (IQR)) | 5 (3–6) | 16 (8–26) | 25 (16–30) | 10 | 25 (18–40) |

| Location | |||||

| Right colon | 27 (56%) | 25 (52%) | 15 (48%) | 0 | 6 (32%) |

| Left colon | 13 (27%) | 16 (33%) | 9 (29%) | 1 (100%) | 8 (42%) |

| Rectum | 8 (17%) | 7 (15%) | 7 (23%) | 0 | 5 (26%) |

| Macroscopic type | |||||

| Ip | 2 (4%) | 7 (15%) | 6 (19%) | 0 | 0 |

| Is, Is+IIc | 14 (29%) | 6 (13%) | 6 (19%) | 0 | 6 (32%) |

| IIa, IIa+IIc | 26 (54%) | 12 (25%) | 1 (3%) | 0 | 5 (26%) |

| IIb, IIc | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| LST-G | 3 (6%) | 7 (15%) | 12 (39%) | 0 | 2 (11%) |

| LST-NG | 3 (6%) | 16 (33%) | 6 (19%) | 0 | 6 (32%) |

| Pit pattern | |||||

| I | 1 (2%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (5%) |

| II | 20 (43%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| IIIL, IIIS, IIIH | 24 (52%) | 26 (54%) | 9 (29%) | 0 | 0 |

| IV, IVH | 1 (2%) | 4 (8%) | 14 (45%) | 0 | 0 |

| VI (noninvasive) | 0 | 17 (35%) | 6 (19%) | 0 | 7 (37%) |

| VI (invasive) | 0 | 0 | 2 (6%) | 1 (100%) | 9 (47%) |

| VN | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (11%) |

| Not recorded | 2 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

G: granular type; HGN: high-grade intramucosal neoplasia; IQR: interquartile range; JNET: Japan NBI Expert Team; LGN: low-grade intramucosal neoplasia; LST: laterally spreading tumour; NBI: Narrow Band Imaging; NG: nongranular type.

Figure 3.

Representative images of an adenoma evaluated as Japan NBI Expert Team type 1. (a) Type 0–IIa in the Paris classification; (b) unclear meshed vessel pattern; (c) indigo carmine dye image. NBI: Narrow Band Imaging.

Figure 4.

Representative images of a deep submucosal invasive cancer evaluated as Japan NBI Expert Team (JNET) type 2B. (a) Type 0–IIa+IIc in the Paris classification; (b) indigo carmine dye image; (c) JNET type 2B; (d) pit pattern diagnosis correctly shows type VI severe irregularity. NBI: Narrow Band Imaging.

Discussion

This cross-sectional study clearly demonstrates the usefulness of the JNET classification based on large-scale clinical practice data from a clinical setting. The specificity, NPV and accuracy for differentiating neoplastic and non-neoplastic lesions all exceeded 90%. Furthermore, the diagnostic yield was high among expert and nonexpert endoscopists alike. Additionally, both nonexpert and expert endoscopists had specificity, NPV and accuracy >90% for JNET type 2B and 3. Therefore, the JNET classification appears to be a reliable tool for selective diagnosis of Tis (HGN) or T1a. The JNET classification also appears to be clinically useful for differential diagnosis by all endoscopists. NBI magnification is an effective tool for differentiating neoplastic from non-neoplastic lesions.6,15 Previously, a meta-analysis of 11 studies on NBI magnification reported that the pooled sensitivity (95% confidence interval (CI)) and specificity (95% CI) for differentiating neoplastic and non-neoplastic lesions was 92% (90%–94%) and 81% (78%–84%), respectively.16

However, many previous reports were from expert endoscopists. Therefore, in the present study, we included a comparison analysis between eight expert and 11 nonexpert endoscopists. There was no difference between the groups. Therefore, nonexpert endoscopists can use the JNET classification as well as expert endoscopists.

Rastogi et al. reported a prospective study that used NBI without magnification for the characterisation of polyp histology. The sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of NBI for predicting adenomas for polyps ≤5 mm were 95%, 88% and 92%, respectively.10 McGill and colleagues reported a meta-analysis of 28 studies that used NBI to differentiate neoplastic from non-neoplastic colorectal polyps in real time.17 The overall sensitivity and specificity for polyps ≤5 mm were 86% and 84%, respectively. In the present study, the specificity of JNET type 1 (the rate at which the lesion is diagnosed correctly when diagnosed as not non-neoplastic) was 96%. Furthermore, for polyps ≤5 mm, the specificity remained 96%. These results are consistent with previous studies, and therefore, the JNET classification seems to have high diagnostic performance in differential diagnosis, even for diminutive polyps. However, the sensitivity of JNET type 1 for diminutive polyps was low, at 57%. The present study has sampling bias because we did not resect all hyperplastic polyps during colonoscopy.

JNET type 2A had a high diagnostic sensitivity for LGN, but protruding lesions (Ip, Is, LST-G) with a histological classification of HGN to T1a were often misclassified as JNET type 2A. In a prospective study of pit pattern diagnosis, Matsuda et al. reported the superiority of the clinical pit pattern classification for properly identifying the depth of invasion of flat and depressed lesions over polypoid lesions (97.5% vs 75.8%).18 Another study also reported difficulty with depth diagnosis in polypoid lesions compared with nonpolypoid lesions.19 Therefore, it is possible that the protruding lesion is covered by the adenoma component and that this cover results in endoscopic diagnosis of benign disease rather than its actual malignancy.

JNET type 2B had a low sensitivity of 42% because it included various histological features. This result is consistent with the finding by Sano and colleagues of various histological features ranging from adenoma to deep SM cancer.11 Therefore, the endoscopist needs to perform an additional pit pattern diagnosis using magnifying chromoendoscopy when diagnosing a lesion as JNET type 2B. This finding is expected based on the original definition from JNET, in which pit pattern diagnosis is the gold standard for differentiating between T1a and T1b. Therefore, JNET type 2B lesions could include T1b and T1a, and thus require pit pattern diagnosis using crystal-violet for a final treatment decision.

Because the specificity of JNET type 3 was 100%, JNET type 3 is a very specific finding in SM deep invasive cancer. Thus, it may be possible to omit pit pattern diagnosis when there is a high index of suspicion of JNET type 3 lesion. Hayashi et al. reported the endoscopic prediction of deep SM invasive carcinoma by expert endoscopists using the NBI international colorectal endoscopic classification.20 The specificity was 81.5%, even with high confidence. Thus, the strength of the JNET classification is the use of magnifying colonoscopy, which can observe details of the lesion surface.

Based on these large-scale data from 1402 lesions in a clinical setting, JNET type 3 was found to have a high specificity, PPV, NPV and accuracy of deep SM invasive cancer of 100%, 93%, 98% and 98%, respectively. Lesions diagnosed as JNET type 2A had a high sensitivity, PPV and accuracy for LGN (91%, 92% and 87%, respectively). Although Puig and colleagues21 reported that NBI International Colorectal Endoscopic (NICE) type 3 had a high specificity and NPV (96% and 98%, respectively), NICE classification type 2 includes various lesions from LGN to T1a. We thus considered the JNET classification to be useful because the indication for endoscopic treatment can be determined.

This study has some limitations. First, this was a retrospective study performed in a single high-volume centre. However, many participating endoscopists were involved. Second, there was some selection bias. Data were obtained from a clinical examination, and hyperplastic polyps in the sigmoid colon and rectum were mostly not removed even though they were easy to diagnose. We diagnosed the endoscopic resected lesions as type 1 based on sessile-serrated adenoma/polyp,22 a hyperplastic polyp in the proximal colon, the patient’s expectations, and further pit pattern diagnosis showing types II, III and IV. In accordance with the definition of the JNET classification, lesions with granulation tissue and an inflammatory polyp were excluded from this study. Indeed, the sensitivity of type 1 for non-neoplastic vs neoplastic lesions is a reference value. This study focused on lesions removed using endoscopy, and endoscopically unresectable lesions were not included. Third, this study included diminutive polyps (1–5 mm, 47%), which had a lower sensitivity than lesions ≥6 mm. These reasons were considered to account for the low sensitivity of JNET type 1 in this study. Fourth, in total, 11 nonexpert endoscopists including only two board-certified Fellows of the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society had studied the JNET classification in daily clinical conferences and meetings. They were involved in the development of the JNET classification system, attended meetings about the JNET classification, often received expert advice, and routinely used the JNET classification in practice. The learning curve might have influenced the results.23 Thus, caution should be exercised in generalising the outcomes of this study, and it is important to attend study meetings and conferences. Fifth, the study did not include a review of images, and there were no data on the confidence level of the endoscopic diagnosis. Therefore, we are now planning a validation study of the JNET classification system with endoscopists across all of Japan. Sixth, in this study, the endoscopic images were obtained from LUCERA, whereas EXERA is mainly used in most European countries. However, a previous report showed that analysis of endoscopic imaging from LUCERA and EXERA endoscopes provides the same clinical benefit.24 Sumimoto et al.25,26 and Iwatate and colleagues27 reported the diagnostic performance of the JNET classification for differentiation among noninvasive, superficially invasive and deeply invasive colorectal neoplasia. However, there are still few reports on the JNET classification, which is a newly established classification, so its validation is important.

Conclusion

This study clearly demonstrates the utility of the JNET classification both for expert and nonexpert endoscopists for differential and depth diagnoses. If a lesion is classified as JNET type 2B, pit pattern diagnosis should be used as an adjunct for depth diagnosis.

Declaration of conflicting interests

None declared.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the ethics committee of our institution (approval number 2016-245), and the study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in a priori approval by the institution’s human research committee.

Funding

This work was supported by The National Cancer Center Research and Development Fund (29-A-13) and JSPS KAKENHI, grant number 18K07925.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from each patient included in this study.

References

- 1.Allen JI. Molecular biology of colon polyps and colon cancer. Semin Surg Oncol 1995; 11: 399–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carethers JM. The cellular and molecular pathogenesis of colorectal cancer. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 1996; 25: 737–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Ho MN, et al. Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. The National Polyp Study Workgroup. N Engl J Med 1993; 329: 1977–1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sano Y, Ikematsu H, Fu KI, et al. Meshed capillary vessels by use of narrow-band imaging for differential diagnosis of small colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc 2009; 69: 278–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Machida H, Sano Y, Hamamoto Y, et al. Narrow-band imaging in the diagnosis of colorectal mucosal lesions: A pilot study. Endoscopy 2004; 36: 1094–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ikematsu H, Matsuda T, Emura F, et al. Efficacy of capillary pattern type IIIA/IIIB by magnifying narrow band imaging for estimating depth of invasion of early colorectal neoplasms. BMC Gastroenterol 2010; 10: 33–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanao H, Tanaka S, Oka S, et al. Narrow-band imaging magnification predicts the histology and invasion depth of colorectal tumors. Gastrointest Endosc 2009; 69: 631–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wada Y, Kudo SE, Kashida H, et al. Diagnosis of colorectal lesions with the magnifying narrow-band imaging system. Gastrointest Endosc 2009; 70: 522–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hewett DG, Kaltenbach T, Sano Y, et al. Validation of a simple classification system for endoscopic diagnosis of small colorectal polyps using narrow-band imaging. Gastroenterology 2012; 143: 599–607.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rastogi A, Keighley J, Singh V, et al. High accuracy of narrow band imaging without magnification for the real-time characterization of polyp histology and its comparison with high-definition white light colonoscopy: A prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol 2009; 104: 2422–2430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sano Y, Tanaka S, Kudo SE, et al. Narrow-band imaging (NBI) magnifying endoscopic classification of colorectal tumors proposed by the Japan NBI Expert Team. Dig Endosc 2016; 28: 526–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sakamoto T, Nakajima T, Matsuda T, et al. Comparison of the diagnostic performance between magnifying chromoendoscopy and magnifying narrow-band imaging for superficial colorectal neoplasms: An online survey. Gastrointest Endosc 2018; 87: 1318–1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishiguro S. Pathological diagnosis of colorectal cancer according to Japanese Classification of Colorectal Carcinoma [article in Japanese]. Nihon Rinsho 2011; 69(Suppl 3): 325–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watanabe T, Itabashi M, Shimada Y, et al. Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (JSCCR) guidelines 2014 for treatment of colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol 2015; 20: 207–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sakamoto T, Saito Y, Nakajima T, et al. Comparison of magnifying chromoendoscopy and narrow-band imaging in estimation of early colorectal cancer invasion depth: A pilot study. Dig Endosc 2011; 23: 118–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu L, Li Y, Li Z, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of narrow-band imaging for the differentiation of neoplastic from non-neoplastic colorectal polyps: A meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis 2013; 15: 3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGill SK, Evangelou E, Ioannidis JP, et al. Narrow band imaging to differentiate neoplastic and non-neoplastic colorectal polyps in real time: A meta-analysis of diagnostic operating characteristics. Gut 2013; 62: 1704–1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsuda T, Fujii T, Saito Y, et al. Efficacy of the invasive/non-invasive pattern by magnifying chromoendoscopy to estimate the depth of invasion of early colorectal neoplasms. Am J Gastroenterol 2008; 103: 2700–2706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamada M, Saito Y, Sakamoto T, et al. Endoscopic predictors of deep submucosal invasion in colorectal laterally spreading tumors. Endoscopy 2016; 48: 456–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayashi N, Tanaka S, Hewett DG, et al. Endoscopic prediction of deep submucosal invasive carcinoma: Validation of the Narrow-band imaging International Colorectal Endoscopic (NICE) classification. Gastrointest Endosc 2013; 78: 625–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Puig I, López-Cerón M, Arnau A, et al. Accuracy of the Narrow-Band Imaging International Colorectal Endoscopic classification system in identification of deep invasion in colorectal polyps. Gastroenterology 2019; 156: 75–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamada M, Sakamoto T, Otake Y, et al. Investigating endoscopic features of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps by using narrow-band imaging with optical magnification. Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 82: 108–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higashi R, Uraoka T, Kato J, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of narrow-band imaging and pit pattern analysis significantly improved for less-experienced endoscopists after an expanded training program. Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 72: 127–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rey JF, Tanaka S, Lambert R, et al. Evaluation of the clinical outcomes associated with EXERA II and LUCERA endoscopes. Dig Endosc 2009; 21: 113–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sumimoto K, Tanaka S, Shigita K, et al. Clinical impact and characteristics of the narrow-band imaging magnifying endoscopic classification of colorectal tumors proposed by the Japan NBI Expert Team. Gastrointest Endosc 2017; 85: 816–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sumimoto K, Tanaka S, Shigita K, et al. Diagnostic performance of Japan NBI Expert Team classification for differentiation among noninvasive, superficially invasive, and deeply invasive colorectal neoplasia. Gastrointest Endosc 2017; 86: 700–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iwatate M, Sano Y, Tanaka S, et al. Validation study for development of the Japan NBI Expert Team classification of colorectal lesions. Dig Endosc 2018; 30: 642–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]