Abstract

Background

Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are associated with reduced health-related quality of life (HRQoL), but findings differ between studies. The aim of this study was to analyse the impact of disease activity and social factors on HRQoL.

Method

A total of 513 patients diagnosed with UC and CD between 2003 and 2004, in a population-based setting, were followed for 7 years. HRQoL was assessed using the Short Form-12, the Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) Questionnaire (SIBDQ), the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire: General Health and a national health survey. Associations were assessed using multiple linear regressions.

Results

A total of 185 of the eligible patients (UC: 107 (50.2%) and CD: 78 (50.3%)) were included. No differences in disease-specific or generic HRQoL were found between CD and UC patients, and IBD patients did not differ compared with the background population. The majority of CD (73.1%) and UC (85.0%) patients had ‘good’ disease-specific HRQoL using the SIBDQ. Unemployment for ≥ 3 months occurred more in CD vs UC patients(30.6 vs 15.5%, p = 0.03); however, sick leave for ≥ 3 months did not differ significantly (17.4 vs 11.4%, p = 0.4). Using multiple linear regressions, unemployment, sick leave and disease activity were the factors most frequently associated with reduced HRQoL.

Conclusion

In a population-based cohort with 7 years of follow-up, HRQoL did not differ between patients and the background population.

Keywords: Inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis, quality of life, cohort study, observational study, patient-reported outcome

Key summary

Summarize the established knowledge on this subject

Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) have been shown to be associated with reduced health-related quality of life (HRQoL).

The impacts of the diseases on HRQoL remain uncertain as previous studies are heterogeneous in their findings.

What are the significant and/or new findings of this study?

In a population-based cohort, HRQoL in CD and UC patients did not differ from that of the background population.

Sick leave, unemployment and activity scores were found to influence HRQoL the most, while disease-related factors such as phenotype, disease course and extraintestinal manifestations were less associated with HRQoL.

HRQoL might not capture the true impact of inflammatory bowel disease on patients' lives.

Introduction

Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are chronic inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs), which are characterized by a heterogeneous and varying disease course. Due to its chronicity, young age of onset, the need for hospital admissions, and medical and surgical treatment, IBD affects patients not only physically but also impairs their social and professional well-being.1 Previous studies have shown that health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is compromised in UC and CD patients.2–4 Several factors have been shown to affect HRQoL, especially clinical- and treatment-related factors such as corticosteroid treatment, hospitalization, IBS-type symptoms, mood disorders and the number of relapses.4–7 Similarly, sociodemographic factors such as gender, smoking, work disability, sick leave and unemployment also influence HRQoL in IBD patients.3,8,9

Patient-reported outcomes have been shown to be important treatment outcomes for UC and CD patients, and should be considered as endpoints in research studies, as well as used in outpatient clinics to support clinical decision-making.10,11 However, the studies differ in their methodologies, and are often reported from tertiary centres or based on selected patient groups, which makes generalizations based on their results difficult.12

The aim of the present study was to analyse the impact of disease activity and social factors on patient-reported HRQoL in an unselected population-based inception cohort of IBD patients 7 years after diagnosis.

Materials and methods

Population

The study cohort has been described in greater depth elsewhere.13 The patients prospectively enrolled were diagnosed with UC, CD or IBD unclassified (IBDU), between 1 January 2003 and 31 December 2004, in a well-defined geographical area of Copenhagen covering a reference population of 1,211,634 inhabitants (23% of the total population of Denmark in January 2004). In 2012, all diagnoses were re-evaluated, and patients who did not fulfil the diagnostic criteria for CD or UC were excluded from further analysis. In total, 300 UC and 213 CD patients were included in the cohort. The follow-up period started at the date of diagnosis and ended 31 December 2011, covering a minimum follow-up period of 7 years.

Classification and definition

The diagnosis of CD, UC and IBDU was based on the Copenhagen diagnostic criteria.14–16 Disease phenotypes were defined according to the Vienna classification.17 A severe disease course was defined as needing three or more courses of systemic steroids ( ≥ 50 mg/day), and/or biological therapy, and/or surgical resection or colectomy during the follow-up period. Disease activity was defined according to the Harvey–Bradshaw Index (HBI)18 (remission: 0–4, mild: 5–7, moderate: 8–16 and severe: > 16) and the Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index (SCCAI) (remission: 0–2, mild: 3–5, moderate: 6–11 and severe: > 11).19,20 Treatments were grouped into six levels according to the highest level reached during follow-up (0: no treatment, 1: 5-aminosalicylates (5-ASA) (topical and/or systemic 5-ASA ± topical steroids), 2: corticosteroids (systemic steroids ± 5-ASA or topical steroids), 3: immunomodulators (azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP) ± corticosteroids), 4: biological therapy (tumour necrosis factor-α inhibitors) (with any of the options above) and 5: surgical treatment (IBD-related surgery)).

Disease-related factors were defined as factors directly associated with IBD (e.g. location, behaviour and extension of the diseases), while socioeconomic factors were defined as factors that influence the socioeconomic position of a person (e.g. sick leave, unemployment and education).

Data collection

In Denmark, all citizens, whether by birth or immigration, are given a unique 10-digit personal identification number that is used to link their personal information.21 The National Patient Registry and The National Registry of Causes of Death were assessed for missing data, and additional information relevant to this study.22,23 Nationwide data regarding leaves of absence, unemployment and family income were provided by Statistics Denmark.

All medical records (except for two lost records) were retrospectively reviewed from 1 November 2011 to 30 November 2012 and data were collected regarding phenotype, diagnostic procedures (endoscopy, X-ray, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging and capsule endoscopy), medical therapy and surgery.

The patients were excluded if one of following was present: death, mental illness, no Danish skills, emigrated to another country or out of the study area, or wished not to be contacted. All eligible patients were contacted by postal mail with an invitation to an outpatient follow-up visit as well as four self-administrated questionnaires. A reminder was sent in case of no response. During the follow-up visit, disease activity was assessed by the HBI18 and SCCAI.20

Assessment of HRQoL and questionnaires

HRQoL was assessed using the generic Short Form-12 (SF-12) questionnaire and the disease-specific Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (SIBDQ). The SF-12 evaluates patients’ health through a physical and a mental component (PCS-12 and MCS-12), using an empirical scoring algorithm derived from a US population survey.24,25 A mean score of 50 with an SD of 10 was used as the background population for comparison, as it is recommended to facilitate a comparison of results across countries and has proven to be appropriate for the Danish population.25,26 The SIBDQ evaluates HRQoL through four dimensions: bowel symptoms, systemic symptoms, emotional functioning and social functioning. The cut-off point for a ‘good’ HRQoL was set at 50.24–28 Work impairment was assessed using the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire: General Health (WPAI-GH).29 It consists of six items concerning work carried out during the preceding 7 days. The WPAI-GH addresses employment status, number of working and non-working hours due to health problems or other reasons, and the impact of health problems on working productivity and daily activity productivity.30 Absenteeism, presenteeism, activity impairment and productivity loss are all assessed by the questionnaire.30 Validated Danish translations of the original English questionnaires were used.

Information on education, work status and sick leave was obtained using an adapted version of the Danish National Health Survey.31 In short, patients were asked to choose their highest completed level of education and to provide information on their occupation. The patients were asked to recall unemployment and sick leave during the prior 3 years of follow-up. Sick leave options were categorized as ≥3 months, <3 months or no sick leave. Unemployment options were categorized as ≥12 months, 3–12 months or no unemployment.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive data were reported as medians and ranges, or means and SDs, and as counts and percentages. Comparisons between groups were carried out using the Chi-square test, Fisher's exact test or an independent sample Student's t-test. WPAI-GH scores were calculated according to its accompanying guidelines.32

The associations between independent variables (age, gender, smoking status at diagnosis, education, occupation, unemployment status, sick leave, days of absence, yearly family income corrected by number of household members, cumulative unemployment days, behaviour, location and extension at diagnosis, extraintestinal manifestations and severity of disease course) and HRQoL were analysed by multiple linear regression. To avoid overfitting in the regression model, we used the Akaike information criterion for all aforementioned variables in a stepwise algorithm and selected the most appropriate model for the multiple linear regression models. In case of missing data in the independent and dependent variables, multiple imputations with predictive mean matching were performed and imputation was repeated 1000 times. All independent and dependent variables were used in the imputation models. A significance level <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Analyses were performed in SPSS software (version 22.0) and RStudio (R Core Team (2017). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), with the mice R-package used for multiple imputation.

The study was approved by the regional ethical committee on 1 February 2012 (H-1-2011-088) and permission was obtained from the Danish Data Registry (01769 HVH-2012-027). All patients gave written informed consent prior to their inclusion in the present study and the study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as reflected in a priori approval by the institution's human research committee.

Results

Response rate and demographics

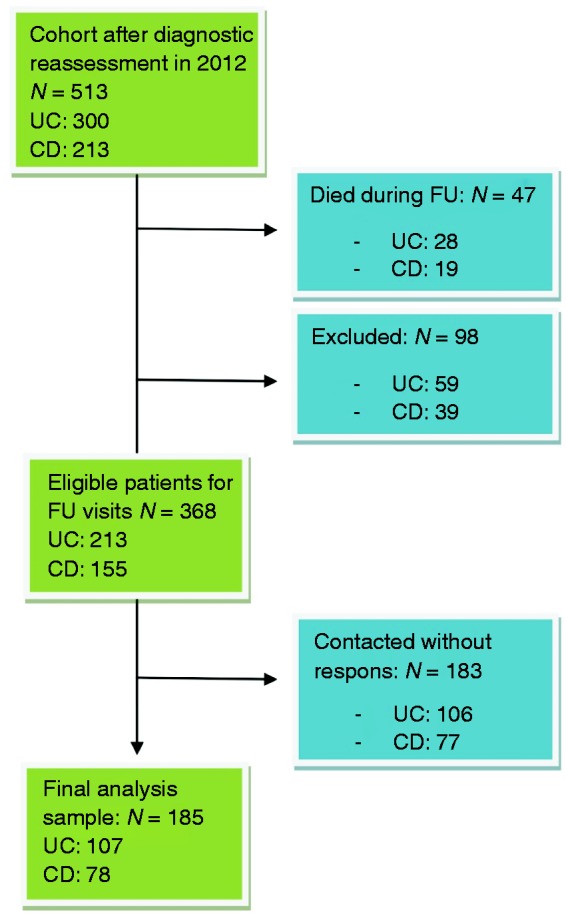

Of the 513 (UC: 300 (58%) and CD: 213 (42%)) patients, 145 were excluded from follow-up (Figure 1). Thus, a total of 368 (UC: 213 and CD: 155) patients were eligible for the follow-up visit, of which 183 (49.7%) declined to participate. A total of 185 (50.3%) (UC: 107 (50.2%) and CD: 78 (50.3%)) of the eligible patients answered all four questionnaires; however, four were not scored with the SCCAI and six were not scored with the HBI (Tables 1 and 2). The median follow-up period of the 185 patients was 7.6 (interquartile range (IQR): 7.2–8.3) years.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study population.

CD: Crohn's disease; FU: follow-up; UC: ulcerative colitis.

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of ineligible and eligible patients.

| CD |

UC |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Included | Excluded | Included | Excluded | |

| Number of patients, N | 78 | 77 | 107 | 106 |

| Gender, N (%) | ||||

| Male | 43 (55.1) | 42 (54.5) | 47 (43.9)b | 61 (57.5) |

| Female | 35 (44.9) | 35 (45.5) | 60 (56.1)b | 45 (42.5) |

| Median age (SD) at diagnosisa | 29 (13.5) | 33 (16.2) | 36 (14.3) | 33 (15.5) |

| Smoking at diagnosis, N (%)a | ||||

| Never smoked | 32 (41.6) | 43 (56.6) | 52 (48.6) | 54 (62.1) |

| Current smoker | 32 (41.6) | 27 (35.5) | 14 (15.1) | 15 (17.2) |

| Former smoker | 13 (16.9) | 6 (7.9) | 27 (25.2) | 18 (20.7) |

| N/A | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.3) | 14 (13.1) | 19 (17.9) |

| Yearly income adjusted for household members (€) | 33639 (15899) | 35,446 (22,974) | ||

| Cumulative days of absence | 387 (563) | 334 (601) | ||

| Cumulative days of unemployment | 78 (163) | 121 (286) | ||

| Treatment (highest treatment step reached during follow-up), N (%)a | ||||

| 0: no treatment | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.3) | 9 (8.4) | 5 (4.7) |

| 1: 5-ASA | 4 (5.1) | 3 (3.9) | 29 (27.1) | 34 (32.1) |

| 2: corticosteroids | 11 (14.1) | 11 (14.3) | 29 (27.1) | 30 (28.3) |

| 3: immunomodulators | 21 (26.9) | 21 (27.3) | 22 (20.6) | 15 (14.2) |

| 4: biological therapy | 13 (16.7) | 8 (10.4) | 7 (6.5) | 3 (2.8) |

| 5: IBD-related surgery | 29 (37.2) | 33 (42.9) | 11 (10.3) | 19 (17.9) |

| Severe disease course, N (%)a | ||||

| Yes | 42 (53.8) | 39 (50.6) | 29 (27.1) | 27 (25.5) |

| No | 36 (46.2) | 38 (49.4) | 78 (72.9) | 79 (74.5) |

| Extraintestinal manifestations at diagnosis, N (%)a | ||||

| None | 65 (83.3) | 71 (92.2) | 100 (93.5) | 104 (98.1) |

| 1 ≥ | 13 (16.7) | 6 (7.8) | 7 (6.5) | 2 (1.9) |

| Disease extent at diagnosis (only UC), N (%) | ||||

| E1: proctitis | 37 (34.6) | 27 (25.5) | ||

| E2: left-sided | 43 (40.2) | 53 (50.0) | ||

| E3: extensive colitis | 27 (25.2) | 26 (24.5) | ||

| Age according to Vienna classification (only CD), N (%) | ||||

| A1: < 40 | 55 (70.5) | 47 (61.0) | ||

| A2: ≥ 40 | 23 (29.5) | 30 (39.0) | ||

| Location and behaviour at diagnosis (only CD), N (%) | ||||

| Location: | ||||

| L1: terminal ileum | 17 (21.8) | 25 (32.5) | ||

| L2: colon | 39 (50.0) | 22 (28.6) | ||

| L3: ileocolonic | 18 (23.1) | 23 (29.9) | ||

| L4: upper GI tract | 4 (5.1) | 7 (9.1) | ||

| Behaviour, N (%) | ||||

| B1: non-stricturing, non-penetrating | 63 (80.8) | 57 (74.0) | ||

| B2: stricturing | 8 (10.3) | 10 (13.0) | ||

| B3: penetrating | 7 (9.0) | 10 (13.0) | ||

| Change in phenotype, N (%) | ||||

| Yes | 23 (29.5) | 31 (40.3) | 33 (30.8) | 35 (33.0) |

| No | 55 (70.5) | 46 (59.7) | 74 (69.2) | 71 (67.0) |

5-ASA: 5-aminosalicylates; CD: Crohn's disease; GI: gastrointestinal; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; UC: ulcerative colitis.

Difference between included ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease patients, p < 0.05.

Difference between included and excluded patients, separately analysed for ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease.

Table 2.

Mean scores (SD) for the Short Form-12 and Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire.

| CD | UC | |

|---|---|---|

| SF-12: | ||

| PCS-12 (vs background population) | 49.1 (10.2) (p = 0.6) | 49.7 (10.0) (p = 0.8) |

| MCS-12 (vs background population) | 49. 6 (10.6) (p = 0.8) | 52.1 (9.0) (p = 0.1) |

| SIBDQ: | ||

| SIBDQ score | 55.6 (11.9) | 57.9 (10.3) |

| • Bowel | 16.6 (4.0) | 16.8 (3.7) |

| • Systemic | 9.8 (3.2) | 10.9 (2.7) |

| • Emotional | 16.8 (4.1) | 17.4 (3.2) |

| • Social | 12.5 (2.4) | 12.8 (2.6) |

Three patients (two with ulcerative colitis and one with Crohn's disease) (1.6%) were excluded from the Short Form-12 mean score analysis due to incomplete responses to the questionnaires.

CD: Crohn's disease; MCS-12: mental component of the SF-12; PCS-12: physical component of the SF-12; SF-12: Short Form-12; SIBDQ: Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire; UC: ulcerative colitis.

Clinical conditions and disease activity at follow-up

In CD patients, the median score (IQR) for the HBI was 1 (0–3). In UC patients, the median score for the SCCAI was 1 (0–3). A total of 84.7% of CD patients and 70.9% UC patients had scores equivalent to remission (i.e. HBI ≤ 2 and SCCAI < 5) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Social factors and disease activity scores of included patients after 7 years of follow-up.

| CD | UC | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 78 | 107 |

| Level of education, N (%)a | ||

| Academic | 35 (44.9) | 57 (53.8) |

| Non-academic | 39 (50.0) | 29 (27.4) |

| Other | 4 (5.1) | 20 (18.9) |

| N/A | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) |

| Work status, N (%) | ||

| Employed | 55 (73.3) | 77 (74.0) |

| Unemployed | 5 (6.7) | 4 (3.8) |

| Student | 6 (8.0) | 5 (4.8) |

| Retired | 9 (12.0) | 18 (17.3) |

| N/A | 3 (3.8) | 3 (2.8) |

| Unemployment during last 3 years, N (%)a | ||

| ≥ 1 year | 13 (18.1) | 7 (7.2) |

| 3–12 months | 9 (12.5) | 8 (8.2) |

| No unemployment | 50 (69.4) | 82 (84.5) |

| N/A | 6 (7.7) | 10 (9.3) |

| Sick leave during last 3 years, N (%) | ||

| ≥ 3 months | 12 (17.4) | 11 (11.4) |

| < 3 months | 21 (30.4) | 31 (32.3) |

| No sick leave | 36 (52.2) | 54 (56.3) |

| N/A | 9 (11.5) | 11 (10.3) |

| HBI (CD only), N (%) | ||

| Remission | 61 (84.7) | |

| Mild disease activity | 9 (12.5) | |

| Moderate disease activity | 2 (2.8) | |

| Severe disease activity | 0 (0.0) | |

| N/A for HBI | 6 (7.7) | |

| SCCAI (UC only), N (%) | ||

| Remission | 73 (70.9) | |

| Mild disease activity | 22 (21.4) | |

| Moderate disease activity | 8 (7.8) | |

| Severe disease activity | 0 (0.0) | |

| N/A for SCCAI | 4 (3.7) |

CD: Crohn's disease; HBI: Harvey–Bradshaw Index; SSCAI: Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index; UC: ulcerative colitis.

Difference between ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease patients, p < 0.05.

Among those with a severe disease course (i.e. three or more courses of systemic steroids and/or biological therapy and/or surgical resection), there was a significant difference between CD and UC patients (p < 0.001), but no significant difference between male and female patients (Table 1).

HRQoL

The mean scores for the SF-12 and SIBDQ are shown in Table 2. Female CD patients reported significantly lower scores for the PCS-12 (female: 45.7 (11.6) vs male: 53.3 (6.3), p < 0.001), while no difference between genders was found for the MCS-12 (female: 48.1 (11.6) vs male: 51.4 (9.0)). There were no significant differences in SF-12 scores between UC males and females. No gender difference was found among SIBDQ scores. The overall proportion of UC and CD patients with a ‘good’ disease-specific HRQoL (SIBDQ ≥ 50) was 80.0%. No significant difference between UC and CD patients was found, although there was a trend towards better HRQoL in UC patients (UC: 91 (85.0%) vs CD: 57 (73.1%), p = 0.07) measured by SIBDQ. In an unpaired Student's t-test, no significant difference was found between the IBD group and the background population for the PCS-12 or for the MCS-12 (Table 2).

Significantly more CD patients experienced better QoL when in remission, measured by the SIBDQ (remission: 61 (82.0%) vs active disease: 11 (36.4%), p = 0.005). However no differences were found between using the PCS-12 or MCS-12. When assessing the same for UC patients, a significant differences was found both using the SIBDQ (remission: 69 (94.5%) vs active disease 18 (60.0), p < 0.001), the PCS-12 (remission: 59 (83.1%) vs active disease (10 (33.3%), p < 0.001) and the MCS-12 (remission: 59 (78.9%) vs active disease: 17 (56.7%), p = 0.042). When stratifying by disease behaviour, location or extension, whether the patients had a change in phenotype or whether they received biological treatment during follow-up, no significant differences were found in CD patient nor UC patients.

When assessing associating factors, the independent variables (shown in Table 4 and 5) were all tested for their relevance using the Akaike information criterion. The relevant factors for generic and disease-specific HRQoL were then incorporated into the respective multiple linear regression models. The results are shown in Tables 4 and 5.

Table 4.

Factors associated with health-related quality of life and work productivity among Crohn's disease patients.

| Crohn's disease Health-related quality of life and work productivity |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (CI95) | PCS | MCS | SIBDQ | Absenteeism | Presenteeism | Activity impairment | Productivity loss |

| Age at diagnosis | N/A | N/A | N/A | −0.1 (−0.4, 0.1) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Gender (male) (ref = female) | 7.3 (3.3, 11.2) | N/A | N/A | N/A | −6.3 (−16.9, 4.2) | −12.7 (−24.4, −1.1) | N/A |

| Smoking at diagnosis (current) (ref = never/former) | N/A | 3.8 (−0.1, 7.8) | N/A | −5.6 (−11.2, 0.1) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Location at diagnosis (ref = terminal ileum + ileocolonic) | |||||||

| Colon + upper GI | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | −2.7 (−13.4, 8.1) | N/A | N/A |

| Behaviour at diagnosis (ref = non-stricturing, non-penetrating) | |||||||

| Complicated Crohn's diseasea | N/A | N/A | N/A | 5.9 (−1, 12.9) | −4.3 (−17.8, 9.2) | N/A | N/A |

| Change in disease phenotype | 4 (−0.1, 8.2) | −2.7 (−7.2, 1.8) | N/A | −7.8 (−14.5, −1.1) | N/A | −12 (−25.1, 1) | N/A |

| Extraintestinal manifestation | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | −4.3 (−19.5, 10.9) | N/A | N/A |

| Education status (academic) (ref = non-academic/others) | 5.4 (1.6, 9.3) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Employment status (ref = unemployed) | |||||||

| Employed | N/A | 7.2 (−0.7, 15.1) | −4.9 (−10.6, 0.7) | −9 (−19.9, 1.9) | −26 (−47.7, −4.2) | N/A | N/A |

| Other | N/A | 0.3 (−8.5, 9.1) | −5.3 (−10.2, −0.4) | −12.2 (−24.4, 0) | −20.4 (−44.7, 3.9) | N/A | N/A |

| Unemployment (ref = no unemployment) | |||||||

| 3–12 months | N/A | −1.7 (−8.3, 4.8) | N/A | 1.1 (−8.1, 10.3) | −8.5 (−26.5, 9.5) | N/A | −40,6 (−60.8, −20.3) |

| > 12 months | N/A | −10.7 (−16.1, −5.2) | N/A | −6.4 (−14, 1.1) | 7.7 (−6.2, 21.5) | N/A | −32.7 (−54.9, −10.5) |

| Sick leave (ref = no sick leave) | |||||||

| < 3 months | N/A | −7.1 (−11.7, −2.4) | N/A | 7 (0.6, 13.5) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| > 3 months | N/A | 0.1 (−5.8, 6.1) | N/A | 10.6 (2.3, 18.9) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Severe disease course | N/A | N/A | N/A | −8.7 (−25, 7.6) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Severe disease course + perianal disease | N/A | N/A | −3 (−6.7, 0.7) | 8.1 (−8.4, 24.5) | 4.2 (−6.6, 15) | 9.9 (−2.2, 22.1) | N/A |

| Yearly family income (100,000 €) | 15.8 (3.9, 27.6) | −9.7 (−21.7, 2.4) | N/A | 40.7 (24.2, 57.2) | N/A | N/A | 25 (−7.6, 57.7) |

| Cumulative days of absence | N/A | 0 (0, 0) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Cumulative days of unemployment | N/A | 0 (0, 0) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Harvey–Bradshaw Index | −1.5 (−2.3, −0.6) | −0.6 (−1.5, 0.4) | −2.7 (−3.5, −1.9) | 0.5 (−0.8, 1.8) | 0.5 (−1.9, 2.9) | 4.5 (2, 7) | 1.4 (−1, 3.8) |

Using the Akaike information criterion for all the listed variables in a stepwise algorithm, we selected the most appropriate model based on the Akaike information criterion for the multiple linear regression model. If ‘N/A’, the variable was not appropriate for the model. Numbers in bold indicate a significant association. Positive estimates indicate a positive linear relationship and vice versa.

GI: gastrointestinal; MCS: mental component summary; PCS: physical component summary; ref: reference; SIBDQ: Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire; CI95: 95 % confidence interval.

Stricturing or penetrating Crohn's disease.

Table 5.

Factors associated with health-related quality of life and work productivity among ulcerative colitis patients.

| Ulcerative colitis Health-related quality of life and work productivity |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (CI95) | PCS | MCS | SIBDQ | Absenteeism | Presenteeism | Activity impairment | Productivity loss |

| Age at diagnosis | −0.2 (−0.3, −0.1) | 0.2 (0.1, 0.3) | 0.2 (0, 0.3) | N/A | 0.3 (0.1, 0.5) | N/A | 0.5 (0.1, 1) |

| Gender (male) (ref = female) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Smoking at diagnosis (current) (ref = never/former) | −3.2 (−7.6, 1.3) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 9.7 (1.2, 18.3) | 8.5 (−1.6, 18.7) | 21.9 (6, 37.7) |

| Extension at diagnosis (ref = proctitis) | |||||||

| Left-sided + extensive | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | −5.1 (−12.6, 2.4) | N/A |

| Change in disease phenotype | N/A | N/A | −2.5 (−5.9, 0.9) | N/A | 9 (2.3, 15.7) | N/A | N/A |

| Extraintestinal manifestation | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Education status (academic) (ref = non-academic/others) | N/A | 2.4 (−0.8, 5.6) | 2.5 (−0.6, 5.6) | N/A | N/A | N/A | −11.7 (−23.6, 0.2) |

| Employment status (ref = unemployed) | |||||||

| Employed | 8 (−0.3, 16.3) | N/A | 7.4 (−0.5, 15.4) | N/A | N/A | N/A | −46.2 (−72.6, −19.8) |

| Other | 7 (−2.3, 16.3) | N/A | 5.3 (−3.7, 14.3) | N/A | N/A | N/A | −37.2 (−67.4, −7.1) |

| Unemployment (ref = no unemployment) | |||||||

| 3–12 months | 3 (−4.1, 10.1) | N/A | 4.1 (−2.7, 10.8) | N/A | N/A | 0.9 (−13, 14.8) | N/A |

| >12 months | −5.4 (−11.1, 0.3) | N/A | −4.9 (−10.5, 0.6) | N/A | N/A | 12.4 (−0.1, 24.9) | N/A |

| Sick leave (ref = no sick leave) | |||||||

| <3 months | −0.8 (−4.4, 2.7) | −3.4 (−6.9, 0) | −2.1 (−5.5, 1.4) | 5.4 (−4.1, 14.9) | 4.2 (−2.6, 11) | 2.2 (−5.6, 9.9) | NA |

| >3 months | −7.8 (−13, −2.5) | −5 (−10.1, 0.1) | −7.7 (−12.7, −2.8) | 24.4 (10.5, 38.4) | 17.5 (7.4, 27.5) | 12.5 (0.9, 24.2) | NA |

| Severe disease course | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Severe disease course + perianal disease | N/A | 4 (0.5, 7.6) | N/A | N/A | 5.4 (−2.1, 12.8) | N/A | N/A |

| Yearly family income (100,000 €) | N/A | N/A | 4.5 (−2, 11.1) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Cumulative days of absence | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Cumulative unemployment days | 0 (0, 0) | N/A | N/A | 0 (0, 0) | N/A | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0.1) |

| Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index | −2 (−2.8, −1.3) | −1.5 (−2.2, −0.7) | −2.6 (−3.3, −1.9) | 1.8 (−0.2, 3.9) | 3.2 (1.8, 4.7) | 6.3 (4.6, 8) | 4.7 (2, 7.4) |

Using the Akaike information criterion for all the listed variables in a stepwise algorithm we selected the most appropriate model based on the Akaike information criterion for the multiple linear regression model. If ‘N/A’, the variable was not appropriate for the model. Numbers in bold indicate a significant association. Positive estimates indicate a positive linear relationship and vice versa.

PCS: physical component summary; MCS: mental component summary; ref: reference; SIBDQ: Short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire; CI95: 95 % confidence interval.

Unemployment, sick leave and work productivity

A total of 20 patients (13 CD and 7 UC) (12.1%) reported having been unemployed for ≥ 12 months at some point during the prior 3 years. An almost equal distribution of men and women (male: 22 (23.2%) vs female: 15 (20.3%), p = 0.8) reported > 3 months of unemployment, but a greater number of these suffered from CD as compared to UC (CD: 22 (30.6%) vs UC: 15 (15.5%), p = 0.03) (Table 3). Sick leave for ≥ 3 months or longer was more common among CD patients than among UC patients (CD: 12 (17.4%) and UC: 11 (11.4%), p = 0.4), but with a similar distribution between men and women (males: 12.3% and females: 15.2%, p = 0.8).

The mean percentage for absenteeism during the follow-up period was 5.6% for CD patients and 6.5% for UC patients. While working, 11.7% of the CD patients and 9.6% of the UC patients experienced presenteeism, and 22.6% of CD patients and 16.4% of UC patients experienced activity impairment. The average productivity loss among CD patients was 16.0%, while among UC patients it was 14.6%; these differences are not statistically significant.

When assessing associating factors, the independent variables (shown in Tables 4 and 5) were all tested for their relevance using the Akaike information criterion. The relevant factors for absenteeism, presenteeism, activity impairment and productivity loss were then incorporated into the respective multiple linear regression models. The results are shown in Tables 4 and 5.

Discussion

In a population-based inception cohort, we found that after a median of 7.6 years of follow-up, patients with CD and UC did not experience reduced generic or disease-specific HRQoL. HRQoL was driven by disease activity and socioeconomic factors. Patients in clinical remission at the time of the survey experienced good generic HRQoL that was similar to that of the background population, despite differences in their independent disease courses.

Regarding generic QoL measurements, we found that SF-12 scores were comparable to those of the background population.24,25 The same was true of disease-specific HRQoL. Both of these findings are supported by previous studies: the Inflammatory Bowel Disease in South-Eastern Norway (IBSEN) cohort study found that disease-specific HRQoL scores after 10 years of follow-up were similar to those of the general population,8,33 and a Europe-wide population-based cohort study reported no overall reduction in HRQoL when compared to the background population.9 These findings indicate that several years after diagnosis, most patients' HRQoL is not being influenced significantly by their IBD. This might be explained by the disease course of IBD. Previous cohort studies have shown that the years immediately following diagnosis are characterized by attempts to get the disease under control, including multiple adjustments to medical therapy.34–36 It is in these first years after diagnosis that the majority of surgical interventions are carried out, thereby reducing disease activity, and likely improving generic and disease-specific HRQoL.13,37 Furthermore, after several years patients are more likely to have learned to live with their disease and accepted their chronic diagnosis, and thus their burden can sometimes be masked by their coping strategies.38 To overcome this limitation when measuring HRQoL, the IBD Disability Index has recently been developed in order to objectively measure the impact of the diseases on patients' daily lives.39,40

We found that sick leave and unemployment during follow-up significantly correlated with a reduction in patient-reported HRQoL. Interestingly, when assessing variables for inclusion in the multivariable analysis, we found that when we included the disease-related factors (except activity scores), there was a significant overfitting of the models and the use of socioeconomic factors was statistically more correct. This observation is supported by a recent study that demonstrated that patient-reported disease activity was poorly correlated with intestinal inflammation, but strongly correlated with the perception of stress.41 Based on our results, one could hypothesize that the measured HRQoL in fact reflects the socioeconomic safety and stresses that a patient experiences.

Previous studies have reported a significant negative impact of IBD on labour force participation, especially in CD patients, and more often in those that are highly educated.42 We were not able to replicate these findings in the present study. The general absence rate (caused by patient sickness) in Denmark in 2013 was 3.5%, which is lower than the absenteeism of 6.1% found in our cohort of IBD patients. IBD is a chronic disease and patients with chronic diseases (such as arthritis, cancer, diabetes, and heart and lung diseases) often present increased rates of absenteeism.43 The absenteeism scores found in our cohort were similar to those found in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (7.7 vs 5.6% for CD and 6.5% for UC patients),44 indicating that chronic diseases affect patients' work capacities. Given the differences in social welfare systems between countries, comparison of unemployment and sick leave rates between European countries, or with the US, is almost impossible.

The primary strength of the present study is its unselected population-based design, which thereby avoids any selection bias. All enrolled patients were newly diagnosed and lived in a well-defined area, providing a valid representation of disease occurrence, including a broad spectrum of disease severity. The follow-up period of 7 years is long when compared with other study designs, and helps to more accurately characterize the long-term disease course in UC and CD. A further strength of this study is the unique Danish personal identification number, which enables the complete follow-up of every patient and the ready availability of their detailed clinical data. The Danish governmental registries make it possible for additional information to be added in the event that a medical record is lost or incomplete. We also sought to eliminate misdiagnoses by re-evaluating all cases using the Vienna classification.45,46

However, several limitations of the study should be borne in mind. Its small population size increases the risk of type II errors and, in particular, small sample sizes in the various subgroups made it difficult to obtain significant results. Furthermore, the low response rate, and the times between completion and the follow-up visits introduce potential biases. However, no differences in clinical or demographic characteristics (other than gender) were found between patients who were included and patients who were not. The use of questionnaires introduces the risk of recall bias, which might impact the reporting of HRQoL and work impairment. In this study, we did not measure anxiety, mood disorders and IBS-type symptoms, which all are known to have an impact on reducing the HRQoL in patients with IBD.6,7 Interestingly, without assessing these factors, we have managed to demonstrate generic and disease-specific HRQoL that is similar to that of the background population. Finally, we did not ask patients to answer the questionnaires at the time of their diagnosis or regularly during their disease course, and therefore we can neither compare scores over time (and therefore disease courses) nor assess the impact of treatment on the results.

In conclusion, in a population-based inception cohort of IBD patients with 7 years of follow-up, HRQoL was not found to differ between them and the background population. Sick leave, unemployment and activity scores were found to influence HRQoL the most, while disease-related factors were not associated with HRQoL. While these findings are somewhat encouraging, they also highlight the limitations of using the current tools that are designed to assess HRQoL, which might not capture the true impact of IBD on patients' lives.

Acknowledgements

All authors made significant contributions to the research described in this manuscript. LKC: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and manuscript writing. BL: analysis and interpretation of data, and manuscript writing. JB: study concept and design, interpretation of data and manuscript writing. FB and MKVA: acquisition of data, interpretation of data and critical revision of the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as well as the authorship list. JB is the guarantor of the article.

Funding

This work was supported by an unrestricted grants from Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD), Ferring Pharmaceuticals and Tillotts. The study sponsors did not contribute to the study design, the analysis and interpretation of the data, or to the work’s publication.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the regional ethical committee on 1 February 2012 (H-1-2011-088) and permission was obtained from the Danish Data Registry (01769 HVH-2012-027).

Informed consent

All patients gave written informed consent prior to their inclusion in the present study and the study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as reflected in a priori approval by the institution's human research committee.

References

- 1.Burisch J, Jess T, Martinato M, et al. The burden of inflammatory bowel disease in Europe. J Crohn's Colitis 2013; 7: 322–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carlsen K, Burisch J, Munkholm P. Evaluation of quality of life in Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis: What is health-related quality of life? In: Baumgart D. (ed). Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis, Cham: Springer, 2017, pp. 279–289. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernklev T, Jahnsen J, Lygren I, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease measured with the short form-36: Psychometric assessments and a comparison with general population norms. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2005; 11: 909–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burisch J, Weimers P, Pedersen N, et al. Health-related quality of life improves during one year of medical and surgical treatment in a European population-based inception cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease–an ECCO-EpiCom study. J Crohns Colitis 2014; 8: 1030–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernklev T, Jahnsen J, Schulz T, et al. Course of disease, drug treatment and health-related quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease 5 years after initial diagnosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005; 17: 1037–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gracie DJ, Hamlin PJ, Ford AC. Longitudinal impact of IBS-type symptoms on disease activity, healthcare utilization, psychological health, and quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2018; 113: 702–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walker JR, Ediger JP, Graff LA, et al. The Manitoba IBD cohort study: A population-based study of the prevalence of lifetime and 12-month anxiety and mood disorders. Am J Gastroenterol 2008; 103: 1989–1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoivik ML, Moum B, Solberg IC, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with ulcerative colitis after a 10-year disease course: Results from the IBSEN study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012; 18: 1540–1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huppertz-Hauss G, Høivik ML, Langholz E, et al. Health-related quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease in a European-wide population-based cohort 10 years after diagnosis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2015; 21: 337–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williet N, Sandborn WJ, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Patient-reported outcomes as primary end points in clinical trials of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 12: 1246–56.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peyrin-Biroulet L, Sandborn W, Sands BE, et al. Selecting therapeutic targets in inflammatory bowel disease (STRIDE): Determining therapeutic goals for treat-to-target. Am J Gastroenterol 2015; 110: 1324–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoivik ML, Bernklev T, Moum B. Need for standardization in population-based quality of life studies: A review of the current literature. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2010; 16: 525–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vester-Andersen MK, Prosberg MV, Jess T, et al. Disease course and surgery rates in inflammatory bowel disease: A population-based, 7-year follow-up study in the era of immunomodulating therapy. Am J Gastroenterol 2014; 109: 705–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langholz E. Ulcerative colitis. An epidemiological study based on a regional inception cohort, with special reference to disease course and prognosis. Dan Med Bull 1999; 46: 400–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Munkholm P. Crohn's disease—occurrence, course and prognosis. An epidemiologic cohort-study. Dan Med Bull 1997; 44: 287–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vind I, Riis L, Jess T, et al. Increasing incidences of inflammatory bowel disease and decreasing surgery rates in Copenhagen City and County, 2003–2005: A population-based study from the Danish Crohn colitis database. Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101: 1274–1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gasche C, Scholmerich J, Brynskov J, et al. A simple classification of Crohn's disease: Report of the Working Party for the World Congresses of Gastroenterology, Vienna 1998. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2000; 6: 8–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Best WR. Predicting the Crohn's disease activity index from the Harvey-Bradshaw Index. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2006; 12: 304–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walsh AJ, Ghosh A, Brain AO, et al. Comparing disease activity indices in ulcerative colitis. J Crohn's Colitis 2014; 8: 318–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jowett SL, Seal CJ, Phillips E, et al. Defining relapse of ulcerative colitis using a symptom-based activity index. Scand J Gastroenterol 2003; 38: 164–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pedersen CB. The Danish civil registration system. Scand J Public Health 2011; 39: 22–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M. The Danish National Patient Register. Scand J Public Health 2011; 39: 30–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Helweg-Larsen K. The Danish Register of Causes of Death. Scand J Public Health 2011; 39: 26–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ware JE, Kosinski MA, Keller SD. SF-12: How to score the SF-12 Physical and Mental Summary Scales, 3rd ed Boston: The Health Institute, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gandek B, Ware JE, Aaronson NK, et al. Cross-validation of item selection and scoring for the SF-12 Health Survey in nine countries: Results from the IQOLA Project. International Quality of Life Assessment. J Clin Epidemiol 1998; 51: 1171–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ware JE, Gandek B, Kosinski M, et al. The equivalence of SF-36 summary health scores estimated using standard and country-specific algorithms in 10 countries: Results from the IQOLA Project. J Clin Epidemiol 1998; 51: 1167–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Irvine EJ, Zhou Q, Thompson AK. The Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire: A quality of life instrument for community physicians managing inflammatory bowel disease. CCRPT Investigators. Canadian Crohn's Relapse Prevention Trial. Am J Gastroenterol 1996; 91: 1571–1578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han SW, Gregory W, Nylander D, et al. The SIBDQ: Further validation in ulcerative colitis patients. Am J Gastroenterol 2000; 95: 145–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lofland JH, Pizzi L, Frick KD. A review of health-related workplace productivity loss instruments. Pharmacoeconomics 2004; 22: 165–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reilly M. Reilly Associates WPAI:GH V2.0, http://www.reillyassociates.net/WPAI_GH.html (2004, accessed 17 August 2015).

- 31.Elkholm O, Kjøller M, Davidsen M, et al. Sundhed og sygelighed i Danmark 2005 & udviklingen siden 1987, https://www.sdu.dk/da/sif/rapporter/2007/sundhed_og_sygelighed_i_danmark_2005_udviklingen_siden_1987 (2007, accessed 14 April 2015).

- 32.Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics 1993; 4: 353–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Høivik ML, Bernklev T, Solberg IC, et al. Patients with Crohn's disease experience reduced general health and vitality in the chronic stage: Ten-year results from the IBSEN study. J Crohn's Colitis 2012; 6: 441–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burisch J, Kiudelis G, Kupcinskas L, et al. Natural disease course of Crohn's disease during the first 5 years after diagnosis in a European population-based inception cohort: An Epi-IBD study. Gut 2019; 68: 423–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burisch J, Ungaro R, Vind I, et al. Proximal disease extension in patients with limited ulcerative colitis: A Danish population-based inception cohort. J Crohn's Colitis 2017; 11: 1200–1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lo B, Vester-Andersen MK, Vind I, et al. Changes in disease behaviour and location in patients with Crohn's disease after seven years of follow-up: A Danish population-based inception cohort. J Crohn's Colitis 2018; 12: 265–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Solberg IC, Lygren I, Jahnsen J, et al. Clinical course during the first 10 years of ulcerative colitis: Results from a population-based inception cohort (IBSEN Study). Scand J Gastroenterol 2009; 44: 431–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCombie AM, Mulder RT, Gearry RB. How IBD patients cope with IBD: A systematic review. J Crohn's Colitis 2013; 7: 89–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peyrin-Biroulet L, Cieza A, Sandborn WJ, et al. Development of the first disability index for inflammatory bowel disease based on the international classification of functioning, disability and health. Gut 2012; 61: 241–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lo B, Prosberg MV, Gluud LL, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis: Assessment of factors affecting disability in inflammatory bowel disease and the reliability of the inflammatory bowel disease disability index. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018; 47: 6–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Targownik LE, Sexton KA, Bernstein MT, et al. The relationship among perceived stress, symptoms and inflammation in persons with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2015; 110: 1001–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bernklev T, Henriksen M, Lygren I, et al. Relationship between sick leave, unemployment, disability, and health-related quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2006; 12: 402–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vuong T, Berverly C. Absenteeism due to functional limitations caused by seven common chronic diseases in US workers. J Occup Env Med 2015; 57: 779–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Radner H, Smolen JS, Aletaha D. Remission in rheumatoid arthritis: Benefit over low disease activity in patient-reported outcomes and costs. Arthritis Res Ther 2014; 16: R56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, et al. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: Report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol 2005; 19: 5A–36A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, et al. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: Controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut 2006; 55: 749–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]