Significance Statement

Oxygen deprivation or hypoxia drives CKD and contributes to end organ damage. The erythrocyte’s role in delivery of oxygen (O2) is regulated by hypoxia, but the effects of CKD are unknown. The authors use untargeted metabolomics to show that 2,3-BPG, an erythrocyte-specific metabolite that triggers O2 release, increases in a mouse model of CKD. Mouse genetic and human studies revealed that increased erythrocyte 2,3-BPG production and O2 release mediated by the ADORA2B-AMPK signaling cascade counteracts CKD. Enhancing AMPK activation in mice promotes 2,3-BPG production and O2 release, reducing kidney hypoxia and CKD progression. More study is needed to determine if therapies boosting 2,3-BPG production and O2 delivery slow CKD progression.

Keywords: chronic hypoxia; chronic kidney disease; erythrocyte; ADORA2B-AMPK; 2,3-BPG

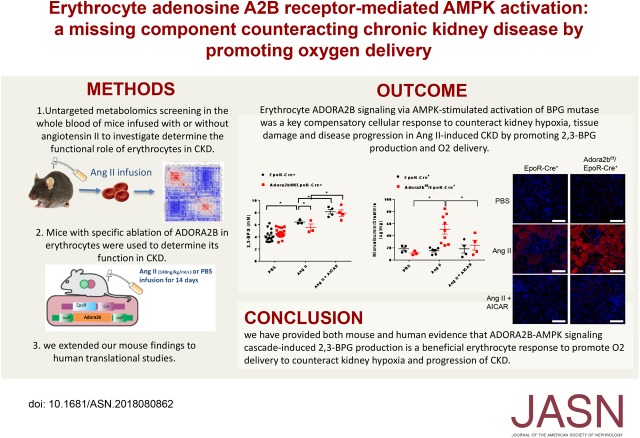

Visual Abstract

Abstract

Background

Oxygen deprivation or hypoxia in the kidney drives CKD and contributes to end organ damage. The erythrocyte’s role in delivery of oxygen (O2) is regulated by hypoxia, but the effects of CKD are unknown.

Methods

We screened all of the metabolites in the whole blood of mice infused with angiotensin II (Ang II) at 140 ng/kg per minute up to 14 days to simulate CKD and compared their metabolites with those from untreated mice. Mice lacking a receptor on their erythrocytes called ADORA2B, which increases O2 delivery, and patients with CKD were studied to assess the role of ADORA2B-mediated O2 delivery in CKD.

Results

Untargeted metabolomics showed increased production of 2,3-biphosphoglycerate (2,3-BPG), an erythrocyte-specific metabolite promoting O2 delivery, in mice given Ang II to induce CKD. Genetic studies in mice revealed that erythrocyte ADORA2B signaling leads to AMPK-stimulated activation of BPG mutase, promoting 2,3-BPG production and O2 delivery to counteract kidney hypoxia, tissue damage, and disease progression in Ang II–induced CKD. Enhancing AMPK activation in mice offset kidney hypoxia by triggering 2,3-BPG production and O2 delivery. Patients with CKD had higher 2,3-BPG levels, AMPK activity, and O2 delivery in their erythrocytes compared with controls. Changes were proportional to disease severity, suggesting a protective effect.

Conclusions

Mouse and human evidence reveals that ADORA2B-AMPK signaling cascade–induced 2,3-BPG production promotes O2 delivery by erythrocytes to counteract kidney hypoxia and progression of CKD. These findings pave a way to novel therapeutic avenues in CKD targeting this pathway.

CKD is a devastating and costly medical condition associated with high morbidity and mortality, affecting approximately one in ten adults, >20 million in the United States, and 8%–16% of the adult population worldwide.1,2 One potential outcome of CKD is ESRD, requiring costly renal replacement therapy by dialysis or transplantation. In the United States, the total Medicare expenditure for all stages of CKD is over $87 billion per year.3 Millions of people die each year due to lack of access to affordable treatments. Because early detection and treatment of CKD can be implemented at minimal cost, will reduce the burden of ESRD, will improve outcomes, and will substantially reduce morbidity and mortality from CKD, defining the molecular mechanisms underlying the disease is extremely important for the development of novel strategies for CKD prevention and treatment.

A large body of evidence indicates that CKD is driven by renal tissue hypoxia.4 In spite of a very high blood flow, the kidney functions under relative hypoxic conditions and is very susceptible to hypoxia.4 Such injury may be accounted for by the fact that the proximal tubule is restricted to primarily aerobic metabolism with little glycolytic capacity.4 Oxygen (O2) consumption by the kidney is predominantly linked to the active absorption of the large filtered load of sodium in the proximal tubule. As such, the kidney is one of the most sensitive organs in our body, consuming large amounts of O2 to maintain its normal “filtering and reabsorbing” function. Notably, the upregulated renin-angiotensin system is considered as one of the most common signaling cascades involved in CKD and its progression to ESRD.5 As a potent vasoconstrictor and the main mediator of the classic renin-angiotensin system, angiotensin II (Ang II) stimulates vasoconstriction, hypoperfusion of peritubular capillaries, and subsequent hypoxia of the tubulointerstitium.6 Without interference, persistent renal hypoxia leads to overly active hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α), transdifferentiation of tubular cells and mesangial cells, activation of resident fibroblasts, and further obstruction and loss of peritubular capillaries with progression of renal fibrosis.7 Although the erythrocyte is the most abundant cell type in our body, acting as both a deliverer and a sensor of O2, its role in increasing renal oxygenation to slow disease progression in CKD remains undetermined. Here, we conducted untargeted high-throughput metabolomics profiling, mouse genetics, preclinical studies, and human translational studies to determine the functional role of erythrocytes in CKD, the underlying mechanisms, and potential therapeutic targets.

Methods

The Methods can be found in the Supplemental Material file.

Results

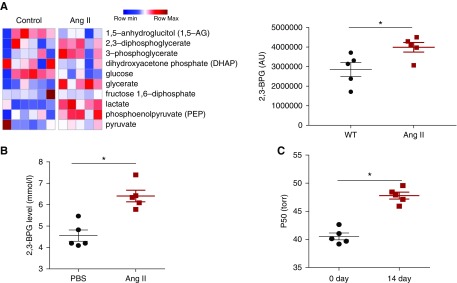

Erythrocyte 2,3-Biphosphoglycerate Levels and Oxygen Release Ability Are Induced in Ang II–Infused CKD Mouse Model

The mature erythrocyte is the most abundant cell type in the blood, and its O2 delivery capacity is finely regulated by its metabolism.8,9 Thus, to determine the functional role of the erythrocyte in CKD, we conducted high-throughput untargeted metabolomics screening in the blood in a well accepted experimental model of CKD with infusion of Ang II. Metabolomics profiling identified 218 metabolites in the whole blood, with significant changes of 68 metabolites (Supplemental Figure 1, Supplemental Material, Supplemental Table 1). Among all of the significantly changed metabolites, 2,3-diphosphoglycerate (2,3-BPG), a metabolic byproduct of glycolysis synthesized primarily by glycolysis in erythrocytes for the purpose of regulating Hb-O2 affinity,10 was highly elevated in the blood of Ang II–infused mice compared with controls (Figure 1). Next, we isolated erythrocytes from saline and Ang II–infused mice to accurately measure 2,3-BPG levels and confirmed our metabolomics screening results that 2,3-BPG levels were significantly increased in the erythrocytes of mice infused with Ang II (Figure 1B). Thus, we conclude that Ang II infusion induces mouse erythrocyte 2,3-BPG levels.

Figure 1.

Metabolomic profiling revealed that 2,3-biphosphoglycerate (2,3-BPG) was among the metabolites highly elevated in the whole blood of angiotensin II (Ang II)–induced hypertensive nephropathy mice compared with controls. (A) Heat map showing significant changes of ten metabolites in the glycolysis pathway. Shades of red and blue represent increased and decreased metabolite concentration, respectively, relative to the median metabolite level (see the color scale); 2,3-BPG, an erythrocyte-specific metabolite, was also increased in the whole blood of Ang II–infused mice. n=5 mice for control group, and n=5 mice for Ang II group. *P<0.05. (B) Level of 2,3-BPG in red blood cells collected from wild-type (WT) mice at day 14 with Ang II or PBS infusion. n=5 mice for each group. An outlier in the PBS group was removed. *P<0.05. (C) Level of the partial pressure of oxygen to allow 50% of hemoglobin binding to oxygen (P50) was significantly elevated in Ang II–infused mouse erythrocytes at day 14. n=5 mice for each group. *P<0.05.

Next, to determine whether increased erythrocyte 2,3-BPG level promotes O2 release capacity in an Ang II–infused mouse model of CKD, we measured the partial pressure of oxygen to allow 50% of hemoglobin binding to oxygen (P50). Specifically, the increased P50 indicates the ease in O2 release. As expected, we found that P50 was significantly elevated in Ang II–infused mouse erythrocytes compared with PBS-infused wild-type (WT) mice (Figure 1C). Thus, our metabolomics profiling led us to discover that erythrocyte 2,3-BPG and O2 release capacity are induced in the Ang II–infused mouse model of CKD.

Erythrocyte ADORA2B Underlies Increased 2,3-BPG Production and O2 Delivery in the Ang II–Infused Mouse Model of CKD

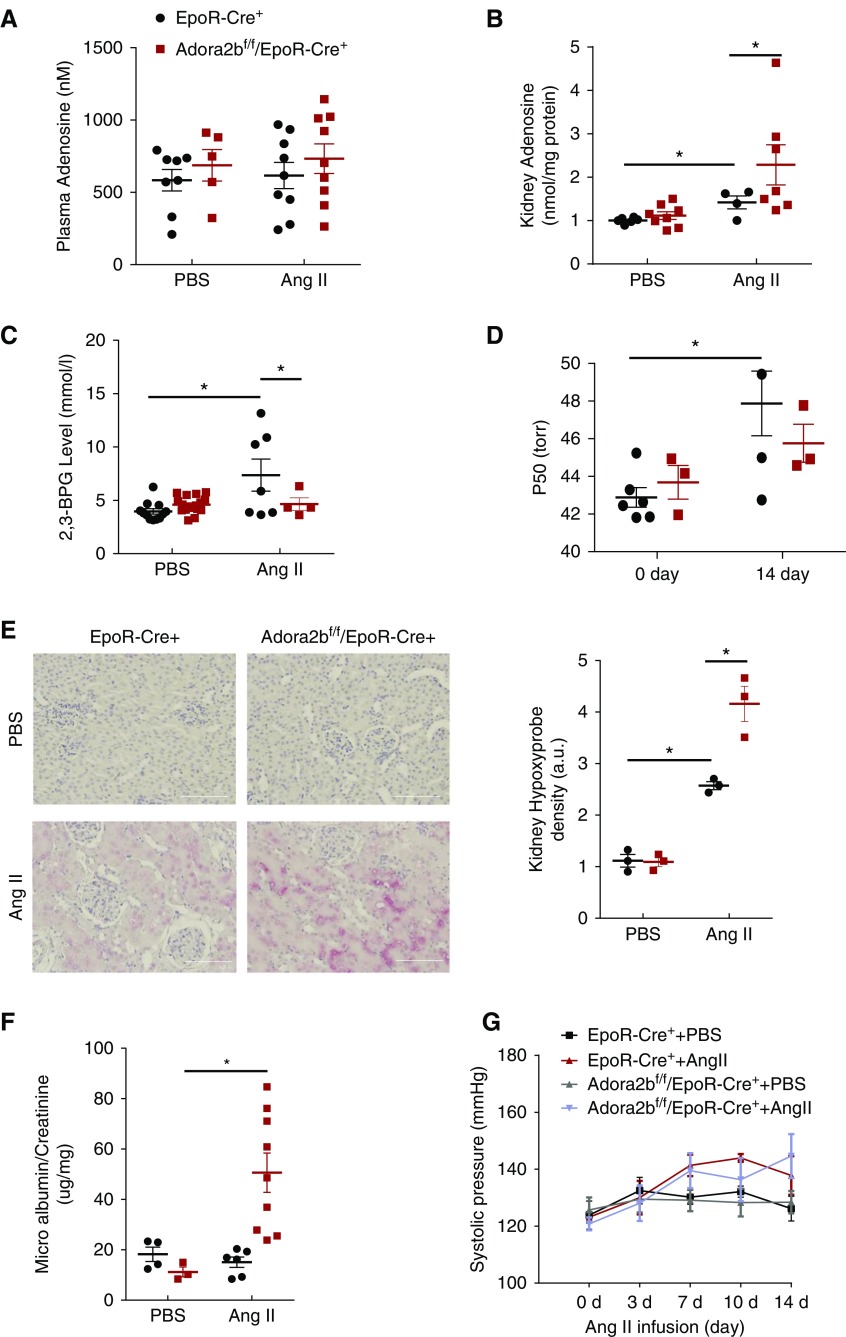

Although a recent study showed that erythrocyte ADORA2B is capable of inducing 2,3-BPG production and O2 delivery under hypoxia conditions,11,12 the functional role of erythrocyte ADORA2B in CKD remains unrecognized. Given that Ang II, a potent vasoconstrictor, decreases blood flow and in turn, leads to renal hypoxia and that Ang II infusion induces adenosine production in mouse kidneys,13,14 we conducted a proof-of-concept genetic study to determine if an erythrocyte-specific ADORA2B receptor underlies 2,3-BPG production, triggers O2 delivery from erythrocyte to promote renal oxygenation, and in turn, decreases kidney hypoxic damage and slows its progression in the CKD mouse model infused with Ang II. Briefly, we used minipump to deliver saline or Ang II (140 ng/kg per minute) to EpoR-Cre+ (control) and Adora2bf/f/EpoR-Cre+ (erythrocyte-specific knockouts) mice for 14 days.13,15,16 We found that Ang II induced renal but not plasma adenosine (Figure 2, A and B). Similar to WT mice, we found that erythrocyte 2,3-BPG levels and P50 were induced by Ang II in EpoR-Cre+ mice, whereas their elevations were significantly reduced in Ang II–infused Adora2bf/f/EpoR-Cre+ mice (Figure 2, C and D). Thus, we demonstrated that elevated renal adenosine signaling via erythrocyte ADORA2B promotes 2,3-BPG production and triggers O2 delivery capacity.

Figure 2.

Erythrocyte ADORA2B underlies increased 2,3-biphosphoglycerate (2,3-BPG) production and oxygen delivery in the angiotensin II (Ang II)–infused mouse model of CKD. (A) Adenosine levels in plasma of mice at day 14 with Ang II or PBS infusion. n=5–9 mice for each group. (B) Adenosine levels in kidneys of mice at day 14 with Ang II or PBS infusion. n=4–8 mice for each group. *P<0.05. (C) Level of 2,3-BPG in red blood cells collected from the mice at day 14 with Ang II or PBS infusion. n=4–17 mice for each group. *P<0.05. (D) The partial pressure of oxygen to allow 50% of hemoglobin binding to oxygen (P50) value of hemoglobin from mice at days 0 and 14 with Ang II or PBS infusion. n=3–6 mice for each group. *P<0.05. (E) Increased renal hypoxia was observed in ADORA2Bf/f/EpoR-Cre+ mice compared with EpoR-Cre+ mice after 14 days of Ang II treatment by Hypoxyprobe. Red indicates Hypoxyprobe and blue indicates 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. n=3 mice for each group. Scale bar, 200 µm. *P<0.05. (F) Ratio of microalbumin to creatinine in 24-hour urine collected on days 0 and 14. n=3–9 mice for each group. *P<0.05. (G) Systolic BP was measured at various intervals by the tail cuff method until mice were euthanized at 14 days. n=6–9 mice for each group.

Erythrocyte ADORA2B Counteracts Kidney Hypoxia, Damage, and Progression in the Ang II–Induced CKD Mouse Model

Our mouse genetic studies immediately suggest that erythrocyte ADORA2B-induced elevation of erythrocyte 2,3-BPG and P50 is a compensatory response to increase kidney oxygenation and in turn, lower Ang II– and vasoconstriction-mediated renal hypoxia, damage, and progression. To test this possibility, we monitor the levels of kidney tissue hypoxia by Hypoxyprobe.17 Elevated Hypoxyprobe signal was detected in the kidney sections of Adora2bf/f/EpoR-Cre+ mice compared with control mice (Figure 2E). Moreover, proteinuria, a parameter of renal injury, was significantly increased in Ang II–infused Adora2bf/f/EpoR-Cre+ mice compared with control mice (Figure 2F). Consistent with published studies,18 Ang II at this dosage did not induce obvious hypertension in both EpoR-Cre+ mice and Adora2bf/f/EpoR-Cre+ mice (Figure 2G). Thus, erythrocyte ADORA2B-induced 2,3-BPG production and O2 delivery directly enhance renal oxygenation, offset kidney hypoxia, and protect against renal damage in Ang II–infused CKD experimental model independent of hypertension.

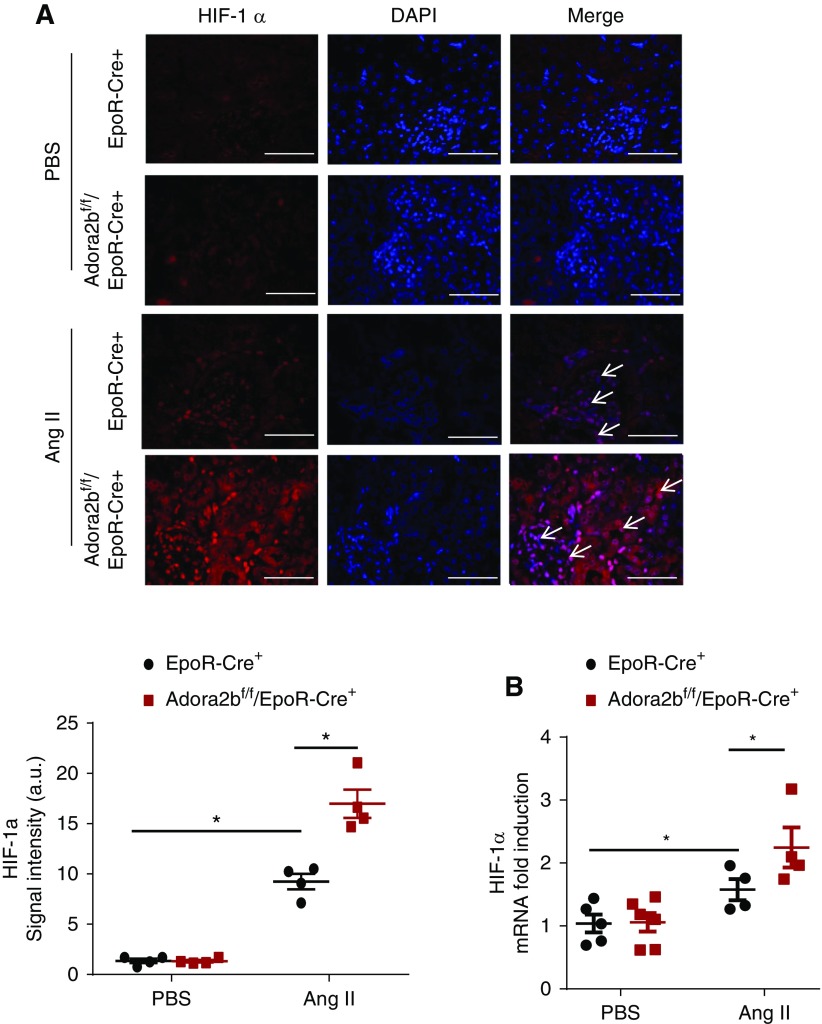

HIF-1α is known to be induced in CKD, and its sustained elevation contributes to disease progression by promoting multiple vasoactive and fibrotic gene expression.16 Thus, we conducted HIF-1α immunostaining and RT-PCR to quantify the gene expression of HIF-1α. Similar to Hypoxyprobe staining, HIF-1α immunostaining significantly increased in the kidney of Ang II–infused Adora2bf/f/EpoR-Cre+ mice compared with the controls (Figure 3A). Consistent with early studies,16 elevated HIF-1α levels were observed in the proximal tubular epithelial cells and the glomeruli, likely in the endothelial cells around the capiary lumen of the controls with Ang II infusion (Figure 3A). Finally, quantitative RT-PCR assay demonstrated that the kidney expression of HIF-1α was significantly elevated in Ang II–infused Adora2bf/f/EpoR-Cre+ mice compared with the controls (Figure 3B). Thus, these findings provide genetic evidence that local accumulation of kidney adenosine signaling via erythrocyte-specific ADORA2B-induced 2,3-BPG production and O2 release is beneficial to promote renal oxygenation and in turn, decrease Ang II–induced renal hypoxia and kidney damage.

Figure 3.

Erythrocyte ADORA2B signaling regulates angiotensin II (Ang II)–induced hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) expression and protein level in kidneys. (A) Increased HIF-1α was observed in ADORA2Bf/f/EpoR-Cre+ mice compared with EpoR-Cre+ mice after 14 days of Ang II treatment by immunofluorescence. Red indicates HIF-1α and blue indicates 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Scale bar, 200 µm. HIF-1α relative OD values in kidneys of mice at day 14 with Ang II or PBS infusion *P<0.05 (n=4 mice for each group). (B) Quantitative RT-PCR measurement of HIF-1α mRNA levels in kidneys of mice at day 14 following Ang II or PBS infusion. n=4 for each group. *P<0.05.

AMP-Activated Protein Kinase Functions Downstream of ADORA2B Underlying 2,3-BPG Production, and AICAR Treatment Rescues Renal Hypoxia and Disease Progression in Ang II–Infused Adora2bf/f/EpoR-Cre+

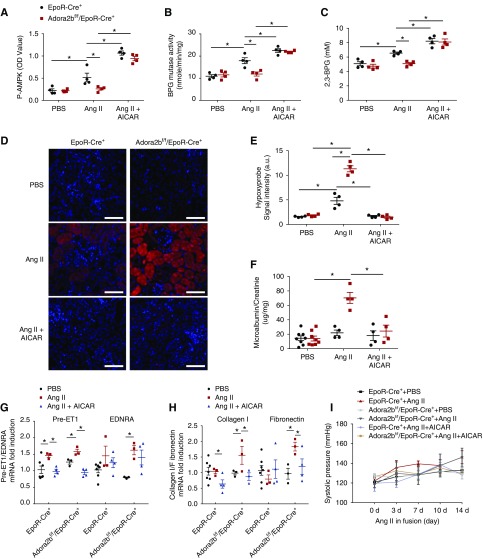

Like adenosine, AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) plays a critical role in multiple cellular functions, especially under conditions of energy depletion and limited O2 availability.19 Recent studies showed that AMPK is a key downstream mediator directly activating BPG mutase and leading to increased 2,3-BPG production in erythrocytes to counter tissue hypoxia in normal mice.11 However, whether AMPK functions downstream of ADORA2B as a key enzyme to induce 2,3-BPG production in red blood cells under CKD conditions is unknown. To test this hypothesis, we compared AMPK and BPG mutase activity in Ang II–infused EpoR-Cre+ (control) and Adora2bf/f/EpoR-Cre+ mice for 14 days. We found that both AMPK (i.e., phosphorylated AMPK) and BPG mutase activity were induced by Ang II in EpoR-Cre+ mice but not in Ang II–infused Adora2bf/f/EpoR-Cre+ mice (Figure 4, A and B). These findings immediately suggest that AMPK is a key molecule underlying 2,3-BPG production and O2 delivery.

Figure 4.

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and diphosphoglycerate (BPG) mutase activities are induced by angiotensin II (Ang II) in EpoR-Cre+ mice but not in Ang II–infused Adora2bf/f/EpoR-Cre+ mice, and AICAR (5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide) treatment rescues the CKD phenotype in Adora2bf/f/EpoR-Cre+ mice. (A–C) Phosphorylation levels of erythrocyte AMPK, mutase activity, and 2,3-BPG levels in mice at day 14 with Ang II or PBS infusion. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. n=4 for each group. *P<0.05. (D and E) AICAR treatment prevented renal hypoxia. (D) Immunohistochemical analysis of tissue hypoxia by Hypoxyprobe in the kidney. Scale bar, 70 μm. (E) Quantitative image analyses of tissue hypoxia by Hypoxyprobe in kidney. n=4 for each group. *P<0.05. (F) Ratio of microalbunin to creatinine in 24 hour urine. n=4 or 8 for each group. *P<0.05. (G and H) Preproendothelin-1 (prepro-ET1), endothelin receptor A (EDNRA), Collagen I, and Fibronectin mRNA levels in mouse kidney. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. n=3–7 for each group. *P<0.05. (I) BP in mice. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. n=4 for each group.

Next, to determine whether AMPK activation is capable of rescuing Ang II–induced 2,3-BPG mutase activity, 2,3-BPG production, renal oxygenation, and progression of CKD in Adora2bf/f/EpoR-Cre+ mice, we conducted proof-of-principle studies to treat Ang II–infused EpoR-Cre+ and Adora2bf/f/EpoR-Cre+ mice with AICAR, a potent AMPK activator, up to 14 days. We first found that AICAR treatment further induced phosphorylated AMPK levels in both EpoR-Cre+ and Adora2bf/f/EpoR-Cre+ mice, indicating the successful administration of AICAR and the response in erythrocytes (Figure 4A). Furthermore, we found that AICAR treatment restored both BPG mutase activity and 2,3-BPG levels in Ang II–infused Adora2bf/f/EpoR-Cre+ mice as well as the Ang II–infused EpoR-Cre+ mice and that it further enhanced their levels compared with those AICAR untreated groups (Figure 4, B and C). To further examine the pathologic consequence, we applied Hypoxyprobe to measure renal oxygenation. As expected, renal oxygenation was significantly improved in AICAR-treated EpoR-Cre+ mice and Adora2bf/f/EpoR-Cre+ mice, where the data showed fewer hypoxia signals compared with untreated groups (Figure 4, D and E). As such, we found that the increase of proteinuria and the progression of CKD, including increased gene expression of pre-ET1, endothelin receptor A, Collagen I, and Fibronectin in Ang II–infused Adora2bf/f/EpoR-Cre+ mice, were significantly attenuated by AICAR administration (Figure 4, F–H). In contrast, AICAR treatment had no obvious effects on BP in EpoR-Cre+ mice or Adora2bf/f/EpoR-Cre+ mice (Figure 4I). Taken together, we have provided pharmacologic and genetic evidence that AICAR treatment restored AMPK activation, leading to activation of BPG mutase and induction of 2,3-BPG production; thus, it rescued renal hypoxia, damage, and progression to CKD in Adora2bf/f/EpoR-Cre+ mice.

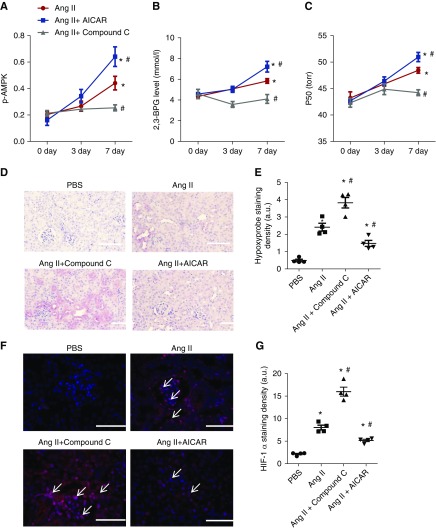

Preclinical Studies in Ang II–Infused WT Mice by AICAR and Compound C

Next, we extended our genetic studies to preclinical studies by treating Ang II–infused WT mice with or without AICAR (a specific AMPK activator) or Compound C (a potent AMPK inhibitor). We found that erythrocyte AMPK activity (i.e., phospho-AMPK) was induced by Ang II in WT mice in a time-dependent manner, and further enhanced by AICAR, whereas AMPK activity was completely abolished by Compound C (Figure 5). Consistently, we found that 2,3-BPG levels and P50 were significantly induced by Ang II in WT mice, further enhanced by AICAR, and completely abolished by Compound C (Figure 5, B and C). As such, AICAR treatment significantly reduced Hypoxyprobe and HIF-1α staining in the kidneys of Ang II–infused WT mice, whereas Compound C further enhanced Hypoxyprobe and HIF-1α staining in the kidneys of Ang II–infused WT mice (Figure 5, D–G). Thus, we provide pharmacologic evidence that AMPK is a critical molecule underlying ADORA2B-mediated BPG mutase activation and that induced AMPK activity by AICAR promotes 2,3-BPG production and O2 release to enhance renal oxygenation and thus, decrease HIF-1α in Ang II–infused WT mice.

Figure 5.

AMP-activated protein kinase functions downstream of ADORA2B, underlying 2,3-biphosphoglycerate (2,3-BPG) production and promoting oxygen delivery to prevent renal hypoxia and disease progression in angiotensin II (Ang II)–induced wild-type (WT) mice. (A–C) AICAR (5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide) treatment significantly stimulated (A) erythrocyte phosphorylated AMP-activated protein kinase (p-AMPK), (B) 2,3-BPG production, and (C) the partial pressure of oxygen to allow 50% of hemoglobin binding to oxygen (P50) levels in Ang II–infused WT mice compared with PBS-treated WT mice in a time-dependent manner, whereas Compound C treatment significantly attenuated (A) erythrocyte p-AMPK, (B) 2,3-BPG production, and (C) P50 levels in Ang II–infused wild-type mice compared with PBS-treated WT mice. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P<0.05 for 7 day versus basal level; #P<0.05 for AICAR-treated group versus PBS group and for Compound C–treated group versus PBS group at the same time point (n=5). (D–G) AICAR treatment prevented renal hypoxia and hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) expression, whereas Compound C treatment aggravated renal hypoxia and HIF-1α expression in WT mice induced by Ang II for 7 days. (D) Immunohistochemical analysis of tissue hypoxia by Hypoxyprobe in kidney. Scale bar, 200 μm. Quantitative image analyses of tissue hypoxia by (E) Hypoxyprobe in kidney and (F) HIF-1α staining in kidneys. Scale bar, 200 μm. *P<0.05 versus PBS-treated WT mice; #P<0.05 versus WT mice with Ang II. (G) Quantitative image analyses of HIF-1α staining in kidney. AICAR- or Compound C–treated WT mice after 7 days of Ang II treatment (n=5). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P<0.05 versus PBS-treated WT mice; #P<0.05 versus WT mice with Ang II.

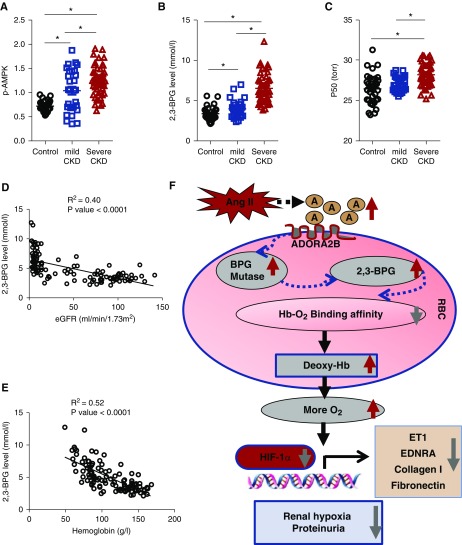

Erythrocyte AMPK, 2,3-BPG Level, and P50 Are Elevated and Correlated with Disease Severity in Patients with CKD

To address the human relevance, we extended our mouse findings to human translational studies. Specifically, we compared erythrocyte AMPK activity, 2,3-BPG levels, and P50 in normal individuals (n=35), patients with mild CKD (n=29), and patients with severe CKD (n=48) (details of clinical information of human subjects are in Table 1). Similar to mice with CKD induced by Ang II, we confirmed that the erythrocyte AMPK activity, 2,3-BPG levels, and P50 were increased in patients with mild CKD compared with the controls, and their elevations were further induced in patients with severe CKD (Figure 6, A–C). No differences were observed between men and women. Notably, elevated erythrocyte 2,3-BPG levels were significantly negatively correlated to the disease severity (reduced eGFR and Hb) (Figure 6, D and E). Our human studies support our mouse studies that elevated erythrocyte AMPK, 2,3-BPG, and P50 likely play a compensatory role to promote renal tissue oxygenation, reduce tissue damage, and thus, slow CKD progression.

Table 1.

Clinical parameters of the patients

| Variable | Control Individuals, n=35 | Patients with Mild CKD, n=29 | Patients with Severe CKD, n=48 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 43.09±10.413 | 45.28±16.65 | 50.56±12.768 |

| Sex, men/women | 16/19 | 16/13 | 25/23 |

| Proteinuria, N | 0 | 24 | 48 |

| Hematuria, N | 0 | 17 | 17 |

| SBP, mm Hg | 119.77±7.99 | 132.31±26.13a | 154.06±21.14a,b |

| DBP, mm Hg | 70.23±7.82 | 82.97±17.09a | 90.52±12.69a,b |

| HB, g/L | 142.20±11.47 | 117.45±27.29a | 83.92±14.96a,b |

| HCT, % | 42.41±3.44 | 35.21±7.64a | 25.83±4.60a,b |

| TP, g/L | 76.49±4.79 | 53.66±10.75a | 56.70±14.15a |

| ALB, g/L | 47.97±2.90 | 29.93±9.85a | 30.99±8.70a |

| GLO, g/L | 28.17±3.90 | 24.77±3.99a | 26.32±5.48 |

| BUN, mmol/L | 4.67±1.32 | 9.70±5.76a | 22.12±11.07a,b |

| SCR, μmmol/L | 79.80±15.25 | 153.52±92.56a | 744.33±311.15a,b |

| eGFR | 93.57±16.26 | 60.26±36.27 | 7.17±3.14 |

SBP, systolic BP; DBP, diastolic BP; HB, hemoglobin; HCT, hematocrit; TP, total plasma protein; ALB, plasma albumin; GLO, plasma globulin; SCR, serum creatinine.

Compared with control, P<0.05.

Compared with patients with mild CKD, P<0.05.

Figure 6.

Erythrocyte AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), 2,3-biphosphoglycerate (2,3-BPG), and the partial pressure of oxygen to allow 50% of hemoglobin binding to oxygen (P50) are elevated and correlated with disease severity in patients with CKD. (A–C) Erythrocyte AMPK, 2,3-BPG level, and P50 are elevated in patients with CKD. (A) Phosphorylated AMP-activated protein kinase (p-AMPK) activity, (B) 2,3-BPG levels, and (C) P50 in normal individuals (n=35), patients with mild CKD (n=29), and patients with severe CKD (n=48). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P<0.05. (D) The linear correlations between 2,3-BPG and eGFR in normal individuals and patients with CKD. (E) The linear correlations between 2,3-BPG and hemoglobin in normal individuals and patients with CKD. (F) Working model of a beneficial role of the erythrocyte adenosine ADORA2B-AMPK signaling cascade in counteracting angiotensin II (Ang II)–induced renal hypoxia, injury, and CKD progression. ET1, endothelin-1; HIF-1α, hypoxia-inducible factor-1α; O2, oxygen; RBC, red blood cell.

Discussion

Nothing was known about the functional role of erythrocytes in CKD before our studies. Here, we provide mouse genetic evidence that erythrocyte ADORA2B signaling via AMPK-mediated induction of 2,3-BPG, an erythroid-specific allosteric modulator, is an important compensatory cellular response to counteract kidney hypoxia, tissue damage, and disease progression in CKD by promoting O2 delivery. Enhancing AMPK activation by AICAR restores the activation of Ang II–induced AMPK activation, thus inducing BPG mutase activity and 2,3-BPG production and in turn, rescuing renal hypoxia, kidney damage, and progression to fibrosis in erythroid-specific ADORA2B knockouts. Preclinical studies showed that enhancing AMPK activation increases kidney oxygenation by triggering 2,3-BPG production and O2 delivery in WT mice. Human translational studies validated that erythrocyte AMPK activity, 2,3-BPG levels, and P50 are significantly increased in patients with CKD and correlated to disease severity. Overall, our findings reveal a beneficial role of the erythrocyte adenosine ADORA2B-AMPK signaling cascade in offsetting Ang II–induced renal hypoxia, injury, and CKD progression, and thereby, they identify novel and important therapeutic possibilities for the disease (Figure 6F).

The erythrocyte is the only cell type to deliver O2 to all of the peripheral tissues in our body. Erythrocyte O2 delivery capacity is regulated by multiple factors, including 2,3-BPG which interacts with oxygenated hemoglobin, causes allosteric conformational changes, decreases hemoglobin affinity to O2, and thereby, promotes the release of the O2 from hemoglobin.20 It has been known for more than four decades that, when humans ascend to high altitude, the concentration of 2,3-BPG in mature red blood cells increases rapidly, and its elevation is correlated with an increased capacity of O2 release from hemoglobin.21 Like normal individuals facing high-altitude hypoxia, erythrocyte 2,3-BPG levels are also elevated in many diseases associated with chronic hypoxia, including CKD, CVD, and anemia.22–24 However, whether increased erythrocyte 2,3-BPG leads to increased O2 delivery in CKD remains unresolved. Untargeted high-throughput metabolomics profiling allows us to identify that 2,3-BPG levels are significantly induced in a well accepted animal model of CKD infusion with Ang II. Similar to adaptive response to physiologic hypoxia, we validated that elevated 2,3-BPG leads to increased erythrocyte O2 delivery capacity in Ang II–infused mice. Consistent with mouse findings, we confirmed that both 2,3-BPG and P50 are increased in patients with CKD. Notably, we found that 2,3-BPG is a much more sensitive biomarker than P50. Its elevation is correlated to disease severity such as decreased eGFR and Hb levels. Thus, we revealed that erythrocyte 2,3-BPG levels and O2 delivery ability are induced in humans and mice with CKD.

The chronic hypoxia hypothesis, proposed by Fine et al.,25 emphasizes chronic hypoxia in the kidney as a final common pathway in end stage kidney injury. Accumulating evidence also indicates the critical role of renal hypoxia before the structural microvasculature damage in the corresponding region, suggesting the pathogenic role of hypoxia in the early stages of kidney disease.26 To offset hypoxia, erythrocytes undergo a number of adaptive responses to promote O2 delivery to peripheral tissues to cope with this challenging condition. Adenosine is well known to be induced by hypoxia, and it orchestrates multifaceted responses to hypoxia by engaging its membrane receptors.27 Multiple studies indicate that chronic accumulated adenosine is detrimental to induce vasoactive and fibrotic gene expression in CKD.28,29 However, the functional role of erythrocyte-regulated kidney oxygenation in the initiation and progression of renal tissue hypoxia, injury, and progression in CKD remains unclear. In this study, using mouse erythrocyte-specific ADOAR2B knockouts, we provided proof-of principle genetic evidence that elevated adenosine signaling via erythrocyte ADORA2B contributes to induction of 2,3-BPG production and O2 release by inducing BPG mutase activity in an AMPK-dependent manner. As such, genetic disruption of erythrocyte-specific ADORA2B lowers AMPK and BPG mutase activity, subsequently reduces 2,3-BPG production and O2 delivery capacity, and eventually exacerbates the Ang II–induced renal hypoxia and injury. Significantly, we provided the genetic proof of principle and preclinical evidence that activating AMPK by its specific agonist induces BPG mutase activity and 2,3-BPG production to counteract kidney hypoxia in WT mice and rescue renal damage and fibrosis in erythroid-specific ADOAR2B knockouts. Consistent with mouse findings, we validated that erythrocyte AMPK activity is also significantly increased in patients with CKD and correlated to the disease severity. Supporting our findings, early studies showed that, in normal individuals, both human high-altitude and mouse genetic studies demonstrate that adenosine can induce 2,3-BPG production and O2 release to counteract hypoxic tissue damage via ADORA2B receptor activation.30 In contrast, in sickle cell disease with the specific mutation in hemoglobin b-subunit, increased adenosine signaling via ADORA2B is detrimental because elevated 2,3-BPG production increases deoxygenated HbS, and subsequent polymerization and disease progression.20 Thus, ADORA2B-mediated elevation of erythrocyte 2,3-BPG production and O2 delivery are beneficial to offset tissue hypoxia in both normal individuals facing high altitude and patients with CKD, whereas they are detrimental in patients with sickle cell disease by promoting deoxygenated HbS polymerization and sickling.

A large body of evidence indicates that sustained renal hypoxia causes prolonged inflammation, upregulation of vasoactive and fibrotic genes, and disease progression through the transcription factor family of HIFs, particularly HIF-1α in CKD.31 In mouse kidneys, HIF-1α levels reach maximal levels after 1 hour under systemic hypoxia.32 Hypoxia and increased HIF-1α accumulation in areas of peritubular capillary rarefaction have been described in multiple CKD models.33,34 Moreover, genetic deficiency of renal epithelial HIF-1α inhibits the development of renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis in unilateral ureteral obstruction rats, and overexpression of HIF-1α in tubular epithelial cells promotes interstitial fibrosis in 5/6 nephrectomy mice.35 More recent studies showed that elevated endothelial HIF-1α also contributes to glomerular injury and promotes CKD. In a high-throughput RT-PCR–based gene expression profiling of the kidneys of Ang II–infused Hif-1αf/f mice and Hif-1αf/f-VEcadherin-Cre+ mice, recent studies identified that HIF-1α is required for the induction of the genes promoting vasoconstriction and fibrosis.16 In this study, we revealed that erythrocyte ADORA2B-induced 2,3-BPG production and O2 release are beneficial to counteract Ang II–induced elevation of renal HIF-1α protein and mRNA levels. As such, a series of genes encoding vasoactive and fibrotic factors, including prepro-ET1, EDNRA, Collagen I, and Fibronectin were significantly induced in erythrocyte ADORA2B-specific knockouts with Ang II infusion compared with the controls. Altogether, these findings indicate that erythrocyte adenosine ADORA2B signaling is required to counteract prolonged elevated HIF-1α–promoted renal vasoactive and fibrotic gene expression in an Ang II–induced CKD mouse model.

In conclusion, we provide both human evidence and mouse evidence supporting a novel working model that erythrocyte ADORA2B signaling–mediated AMPK activation is beneficial to offset renal hypoxia, injury, and progression by inducing 2,3-BPG production, promoting O2 release, and inhibiting HIF-1α–dependent upregulation of renal vasoactive and fibrotic gene expression. Our findings provide new mechanistic insights into CKD and highlight an innovative therapeutic avenue.

Disclosures

None.

Funding

This work is supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL113574 (to Dr. Xia), HL137990 (to Dr. Xia), and HL136969 (to Dr. Xia); Chinese Society of Nephrology grant 1502009057 (to Dr. Peng); Natural Science Foundation of Hunan, China grant 2018JJ3835 (to Dr. Peng); National Natural Science Foundation of China grant 81600528 (to Dr. Luo); and China Scholarship Council grant 201706370155 (to Dr. Xie).

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2018080862/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Figure 1. Heat map of the profiles of metabolites.

Supplemental Material. Material and methods.

Supplemental Table 1. List of all of the 218 metabolites that have been identified through metabolic screening in the whole blood of WT mice with saline (control) or angiotensin II infusion.

References

- 1.Schoolwerth AC, Engelgau MM, Hostetter TH, Rufo KH, Chianchiano D, McClellan WM, et al.: Chronic kidney disease: A public health problem that needs a public health action plan. Prev Chronic Dis 3: A57, 2006 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, Manzi J, Kusek JW, Eggers P, et al.: Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA 298: 2038–2047, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saran R, Li Y, Robinson B, Ayanian J, Balkrishnan R, Bragg-Gresham J, et al. : US Renal Data System 2014 annual data report: Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 66: Svii, S1–305, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fu Q, Colgan SP, Shelley CS: Hypoxia: The force that drives chronic kidney disease. Clin Med Res 14: 15–39, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Remuzzi G, Perico N, Macia M, Ruggenenti P: The role of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in the progression of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl 99: S57–S65, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Macconi D, Remuzzi G, Benigni A: Key fibrogenic mediators: Old players. Renin-angiotensin system. Kidney Int Suppl (2011) 4: 58–64, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Higgins DF, Kimura K, Iwano M, Haase VH: Hypoxia-inducible factor signaling in the development of tissue fibrosis. Cell Cycle 7: 1128–1132, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bianconi E, Piovesan A, Facchin F, Beraudi A, Casadei R, Frabetti F, et al.: An estimation of the number of cells in the human body. Ann Hum Biol 40: 463–471, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiback SJ, Palsson BO: Extreme pathway analysis of human red blood cell metabolism. Biophys J 83: 808–818, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brewer GJ: 2,3-DPG and erythrocyte oxygen affinity. Annu Rev Med 25: 29–38, 1974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu H, Zhang Y, Wu H, D’Alessandro A, Yegutkin GG, Song A, et al.: Beneficial role of erythrocyte adenosine A2B receptor-mediated AMP-activated protein kinase activation in high-altitude hypoxia. Circulation 134: 405–421, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun K, Zhang Y, Bogdanov MV, Wu H, Song A, Li J, et al.: Elevated adenosine signaling via adenosine A2B receptor induces normal and sickle erythrocyte sphingosine kinase 1 activity. Blood 125: 1643–1652, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang W, Zhang Y, Wang W, Dai Y, Ning C, Luo R, et al.: Elevated ecto-5′-nucleotidase-mediated increased renal adenosine signaling via A2B adenosine receptor contributes to chronic hypertension. Circ Res 112: 1466–1478, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dai Y, Zhang W, Wen J, Zhang Y, Kellems RE, Xia Y: A2B adenosine receptor-mediated induction of IL-6 promotes CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 890–901, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang W, Wang W, Yu H, Zhang Y, Dai Y, Ning C, et al.: Interleukin 6 underlies angiotensin II-induced hypertension and chronic renal damage. Hypertension 59: 136–144, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luo R, Zhang W, Zhao C, Zhang Y, Wu H, Jin J, et al.: Elevated endothelial hypoxia-inducible factor-1α contributes to glomerular injury and promotes hypertensive chronic kidney disease. Hypertension 66: 75–84, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song A, Zhang Y, Han L, Yegutkin GG, Liu H, Sun K, et al.: Erythrocytes retain hypoxic adenosine response for faster acclimatization upon re-ascent. Nat Commun 8: 14108, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saleh MA, McMaster WG, Wu J, Norlander AE, Funt SA, Thabet SR, et al.: Lymphocyte adaptor protein LNK deficiency exacerbates hypertension and end-organ inflammation. J Clin Invest 125: 1189–1202, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakada D, Saunders TL, Morrison SJ: Lkb1 regulates cell cycle and energy metabolism in haematopoietic stem cells. Nature 468: 653–658, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun K, Zhang Y, D’Alessandro A, Nemkov T, Song A, Wu H, et al.: Sphingosine-1-phosphate promotes erythrocyte glycolysis and oxygen release for adaptation to high-altitude hypoxia. Nat Commun 7: 12086, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lenfant C, Torrance J, English E, Finch CA, Reynafarje C, Ramos J, et al.: Effect of altitude on oxygen binding by hemoglobin and on organic phosphate levels. J Clin Invest 47: 2652–2656, 1968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Subudhi AW, Bourdillon N, Bucher J, Davis C, Elliott JE, Eutermoster M, et al.: AltitudeOmics: The integrative physiology of human acclimatization to hypobaric hypoxia and its retention upon reascent. PLoS One 9: e92191, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woodson RD, Torrance JD, Shappell SD, Lenfant C: The effect of cardiac disease on hemoglobin-oxygen binding. J Clin Invest 49: 1349–1356, 1970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bersin RM, Kwasman M, Lau D, Klinski C, Tanaka K, Khorrami P, et al.: Importance of oxygen-haemoglobin binding to oxygen transport in congestive heart failure. Br Heart J 70: 443–447, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fine LG, Orphanides C, Norman JT: Progressive renal disease: The chronic hypoxia hypothesis. Kidney Int Suppl 65: S74–S78, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nangaku M: Chronic hypoxia and tubulointerstitial injury: A final common pathway to end-stage renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 17–25, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borea PA, Gessi S, Merighi S, Varani K: Adenosine as a multi-signalling guardian angel in human diseases: When, where and how does it exert its protective effects? Trends Pharmacol Sci 37: 419–434, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Protasiewicz M, Początek K, Podgórski M, Poręba R, Derkacz A, Gosławska K, et al.: Kidney microcirculation response to adenosine stimulation in renal artery stenosis. Blood Press 24: 293–297, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang J, Jiang X, Zhou Y, Xia B, Dai Y: Increased adenosine levels contribute to ischemic kidney fibrosis in the unilateral ureteral obstruction model. Exp Ther Med 9: 737–743, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Y, Xia Y: Adenosine signaling in normal and sickle erythrocytes and beyond. Microbes Infect 14: 863–873, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gunaratnam L, Bonventre JV: HIF in kidney disease and development. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 1877–1887, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stroka DM, Burkhardt T, Desbaillets I, Wenger RH, Neil DA, Bauer C, et al.: HIF-1 is expressed in normoxic tissue and displays an organ-specific regulation under systemic hypoxia. FASEB J 15: 2445–2453, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ballermann BJ, Obeidat M: Tipping the balance from angiogenesis to fibrosis in CKD. Kidney Int Suppl (2011) 4: 45–52, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kawakami T, Mimura I, Shoji K, Tanaka T, Nangaku M: Hypoxia and fibrosis in chronic kidney disease: Crossing at pericytes. Kidney Int Suppl (2011) 4: 107–112, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kimura K, Iwano M, Higgins DF, Yamaguchi Y, Nakatani K, Harada K, et al.: Stable expression of HIF-1alpha in tubular epithelial cells promotes interstitial fibrosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F1023–F1029, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.