Significance Statement

In the distal convoluted tubule, the basolateral inwardly rectifying potassium channel, a heterotetramer of Kir4.1 and Kir5.1, plays an important role in the regulation of potassium excretion by determining the activity of the thiazide-sensitive sodium-chloride cotransporter (NCC). Previous research found that the deletion of Kir4.1 abolishes the effect of dietary potassium intake on NCC and impairs potassium homeostasis. In this study, the authors demonstrate that deleting Kir5.1 abolishes the inhibitory effect of high dietary potassium intake on NCC and impairs the renal ability to excrete potassium during increased dietary potassium intake. Their findings illustrate that like Kir4.1, Kir5.1 is also an essential component of the potassium-sensing mechanism in the distal convoluted tubule, and that Kir5.1 is indispensable for regulation of renal potassium excretion and maintaining potassium homeostasis.

Keywords: potassium channels, hypokalemia, electrophysiology, distal tubule

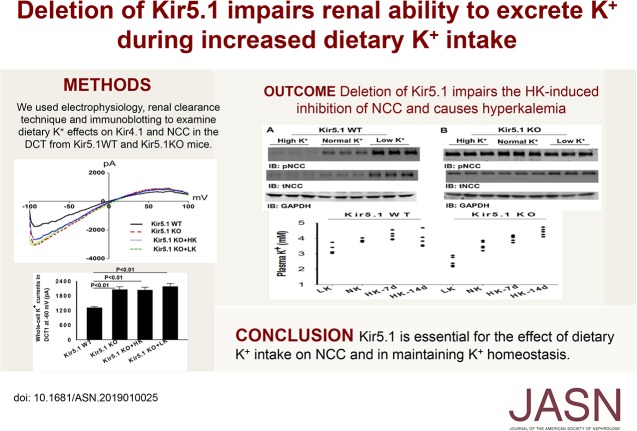

Visual Abstract

Abstract

Background

The basolateral potassium channel in the distal convoluted tubule (DCT), comprising the inwardly rectifying potassium channel Kir4.1/Kir5.1 heterotetramer, plays a key role in mediating the effect of dietary potassium intake on the thiazide-sensitive NaCl cotransporter (NCC). The role of Kir5.1 (encoded by Kcnj16) in mediating effects of dietary potassium intake on the NCC and renal potassium excretion is unknown.

Methods

We used electrophysiology, renal clearance, and immunoblotting to study Kir4.1 in the DCT and NCC in Kir5.1 knockout (Kcnj16−/−) and wild-type (Kcnj16+/+) mice fed with normal, high, or low potassium diets.

Results

We detected a 40-pS and 20-pS potassium channel in the basolateral membrane of the DCT in wild-type and knockout mice, respectively. Compared with wild-type, Kcnj16−/− mice fed a normal potassium diet had higher basolateral potassium conductance, a more negative DCT membrane potential, higher expression of phosphorylated NCC (pNCC) and total NCC (tNCC), and augmented thiazide-induced natriuresis. Neither high- nor low-potassium diets affected the basolateral DCT’s potassium conductance and membrane potential in Kcnj16−/− mice. Although high potassium reduced and low potassium increased the expression of pNCC and tNCC in wild-type mice, these effects were absent in Kcnj16−/− mice. High potassium intake inhibited and low intake augmented thiazide-induced natriuresis in wild-type but not in Kcnj16−/− mice. Compared with wild-type, Kcnj16−/− mice with normal potassium intake had slightly lower plasma potassium but were more hyperkalemic with prolonged high potassium intake and more hypokalemic during potassium restriction.

Conclusions

Kir5.1 is essential for dietary potassium’s effect on NCC and for maintaining potassium homeostasis.

Previous studies demonstrated that high potassium (K+) (HK) intake inhibited the thiazide-sensitive sodium-chloride (Na+-Cl−) (NCC) cotransporter and HK-induced inhibition of NCC was essential for increasing renal K+ excretion (EK) in the aldosterone-sensitive distal nephron (ASDN).1–8 Conversely, a low K+ (LK) intake stimulated NCC activity, thereby suppressing renal EK in the ASDN during decreased dietary K+ intake.1,4,6,8,9 Furthermore, our previous studies demonstrated that the basolateral K+ channel in the distal convoluted tubule (DCT) played a key role in the regulation of the activity of NCC.4,10,11 We observed that HK intake–induced inhibition of NCC was associated with decreased basolateral K+ conductance in the DCT and depolarization. In contrast, LK intake–induced stimulation of NCC was associated with an augmentation of the basolateral K+ conductance in the DCT and hyperpolarization.4,10 The notion that the basolateral K+ channel in the DCT was required for mediating the effect of dietary K+ intake on NCC activity was strongly indicated by the observation that deletion of the basolateral K+ conductance abolished the effect of dietary K+ intake on NCC.4,10

The basolateral K+ channel in the DCT is composed of inwardly rectifying K+ channel 4.1 (Kir4.1 encoded by Kcnj10) and Kir5.1 (encoded by Kcnj16).4,10–14 Although Kir4.1 is able to form a 20-pS homotetramer,15 it prefers interacting with Kir5.1 to form a 40-pS heterotetramer in the basolateral membrane of the DCT.12,16 Although the Kir4.1/Kir5.1 heterotetramer is also expressed in the basolateral membrane of the collecting duct and thick ascending limb in addition to the DCT,17–20 this heterotetramer is a dominant form of the basolateral K+ channel determining the basolateral K+ conductance of the DCT.4,10,11,18 Although Kir5.1 alone cannot be expressed in the plasma membrane or form a functional K+ channel,21 our previous study demonstrated that Kir5.1 may play a role in the regulation of Kir4.1 activity in the DCT by inducing Nedd4-2–mediated ubiquitination of Kir4.1 in the DCT.13 The possibility that Kir5.1 plays a role in regulating Kir4.1 activity in the DCT has a physiologic significance because changes in the basolateral K+ conductance of the DCT are associated with dietary K+ intake–induced alteration of NCC activity, which plays a role in the regulation of renal EK.4,10,11 Thus, the aim of this study is to examine whether the deletion of Kir5.1 impairs the dietary K+ intake–induced changes in the basolateral K+ conductance of the DCT and compromises the effect of dietary K+ intake on the NCC.

Methods

The detailed methods including animal preparation, electrophysiology, Western blot, and renal clearance method are available within the article and in Supplemental Appendix 1.

Animals

We used Kcnj16+/+ (Kir5.1 wild type [WT]) and Kcnj16−/− (Kir5.1 knockout [KO]) mice with C57bl/6j background. We purchased male and female Kcnj16+/− mice from Mary Lyon Centre (Oxfordshire, UK) for breeding in the animal facility of New York Medical College (NYMC). After genotyping, we used 8-week-old male and female Kcnj16−/− and Kcnj16+/+ (WT) mice for experiments. Animals were housed in the NYMC animal facility with lights on at 7:00 am and off at 7:00 pm. The mice had unlimited access to water and rodent chow. For studying the effect of dietary K+ intake on renal EK, the mice were fed with the control diet (1% potassium chloride [KCl]), HK diet (5% KCl) or K+-deficient diet for 7–14 days. The HK diet (catalog no. TD.110866) and K+-deficient diet (TD. 120441) were purchased from Harlan Laboratory (Madison, WI). The K+-deficient diet (LK) contains <0.001% K+ (by weight) and has 19% protein, 59.4% carbohydrate, and 5.2% fat whereas normal diet (1% KCl) has 18.4% protein, 49.7% carbohydrate, and 5.3% fat. The HK diet (5% K+) contains 50 g/kg KCl, 18.4% protein, 45.7% carbohydrate, and 5.3% fat. All the procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Electrophysiology

A Narishige electrode puller (Narishige, Tokyo, Japan) was used to manufacture the patch-clamp pipettes from borosilicate glass (1.7 mm OD). The resistance of pipettes was 5 or 2 MΩ (for whole-cell recording) when it was filled with solution containing 140 mM KCl, 1.8 mM magnesium chloride, and 10 mM HEPES (titrated with KOH to pH 7.4). The details for the single-channel and whole-cell recordings are described in Supplemental Appendix 1.

Renal Clearance and Urinary/Plasma Na+/K+ Analysis

The detailed method for renal clearance is described in Supplemental Appendix 1. After surgery, the mice were perfused with saline intravenously for 4 hour (0.25–0.3 ml/h and total 1.0–1.2 ml) to maintain hemodynamics. Urine collections started 1 hour after infusion of 0.3 ml saline, and six collections (every 30 minutes) were performed (two for controls and four for experiments).

Material

Hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) and amiloride were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). We obtained antibodies for pNCC (Phospho Solution), NCC (Millipore), epithelial sodium (Na+) channel α subunit (ENaCα) (Millipore), Kir4.1(Alomone), Kir4.2 (Alomone), Nedd4-2 (Cell Signaling), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Cell Signaling), and β-actin (Abcam). We verified the specificity of pNCC, NCC, Kir4.1, Kir4.2, and Nedd4-2 antibodies by using the tissues from corresponding gene KO mice.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed by t tests for comparisons between two groups or by one-way ANOVA for more than two groups, and the Holm–Šidák test was used as post hoc analysis. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data are presented as mean±SEM.

Results

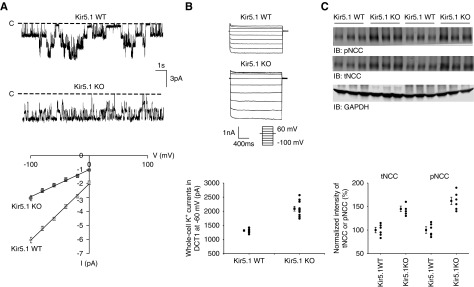

Deletion of Kir5.1 Increased Kir4.1 Activity and NCC in DCT

We first used the single-channel recording technique to examine the basolateral K+ channels in the DCT of WT mice and Kcnj16−/− (Kir5.1 KO) mice (Figure 1A). We detected a 40±2-pS K+ channel in the basolateral membrane of the DCT in both male and female WT mice. This 40-pS K+ channel was completely absent in Kir5.1 KO mice. Instead, we detected a 20±1-pS K+ channel, presumably a Kir4.1 homotetramer, in the basolateral membrane of the DCT of Kir5.1 KO mice (Figure 1A). To examine the effect of Kir5.1 deletion on the basolateral K+ conductance of the DCT, we also used the whole-cell recording to measure the K+ conductance in the early part of the DCT (DCT1) because the whole-cell K+ currents (IK) measured in the DCT1 were equal to Kir4.1 activity in the basolateral membrane.10,11,22,23 Figure 1B is a set of traces showing the whole-cell IKs measured with step protocol (−100 to 60 mV with 20-mV step) and the currents measured at −60 mV from seven or ten experiments (tubules) are summarized in a scatter graph (lower panel) and a bar graph (Supplemental Figure 1A). It is apparent that the IK (2091±86 pA) of the DCT1 in Kir5.1 KO mice are larger than in WT (1316±32 pA). We also confirmed the previous observation that the deletion of Kir5.1 increased the expression of Kir4.1.15 Supplemental Figure 1B is a Western blot showing that the expression of Kir4.1 is higher (190%±8% of the WT) in Kir5.1 KO mice than in Kir5.1 WT mice. Because Kir5.1 also interacts with Kir4.2 which is expressed in the proximal tubule (M. Paulais, personal communications), we have also examined the expression of Kir4.2 in WT and Kir5.1 KO mice. Supplemental Figure 1C is a Western blot demonstrating that the deletion of Kir5.1 decreases the expression of Kir4.2 by 70%±5% (Supplemental Figure 1D) compared with the WT, suggesting that the mechanism by which Kir5.1 regulates the expression of Kir4.1 and Kir4.2 is different. Thus, this study is consistent with a previous report that the deletion of Kir5.1 increases the activity and expression of Kir4.1 in the DCT.13–15 Because increased Kir4.1 activity is associated with high NCC activity,4,10,11 we next examined the expression of NCC and confirmed the previous observation that NCC activity was upregulated in Kir5.1 KO mice.15 Figure 1C is a Western blot showing that deletion of Kir5.1 increases the expression of tNCC/pNCC (the corresponding full-size Western blot is also shown in Supplemental Figure 2A). The results from six independent experiments are summarized in a scatter graph (lower panel) and a bar graph (Supplemental Figure 2B); they show that normalized band density of tNCC and pNCC is larger in Kir5.1 KO mice than in the WT mice (tNCC, 145%±6% of WT; pNCC, 162%±8% of WT). Thus, the deletion of Kir5.1 increased the basolateral Kir4.1 activity and NCC expression.

Figure 1.

Deletion of Kir5.1 increases basolateral K+ conductance and NCC abundance in the DCT. (A) Representative single-channel recordings showing the basolateral K+ channel activity in the DCT of WT and Kir5.1 KO mice. Bottom panel is a current (I)-voltage (V) curve of basolateral K+ channel in the DCT. The experiments were performed in cell-attached patches with bath solution containing 140 mM NaCl/5 mM KCl and the pipette solution containing 140 mM KCl. The channel-closed level is indicated by “C” and the holding potential was 0 mV. (B) Representative whole-cell recordings showing the barium-sensitive IKs measured with step protocol from −100 to 60 mV in the DCT1 of WT and Kir5.1 KO mice. A scatter graph summarizes the values measured at −60 mV with whole-cell recording. The mean value and SEM are shown on the left of each row. For the whole-cell recording, a symmetric 140 mM K+ solution was used for the bath and the pipette. (C) An immunoblot showing the expression of pNCC and tNCC in WT and Kir5.1 KO mice. A scatter graph summarizes the normalized band intensity of the above experiments for tNCC and pNCC, respectively. The mean value and SEM are shown on the left of each row. GADPH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; IB, immunoblot.

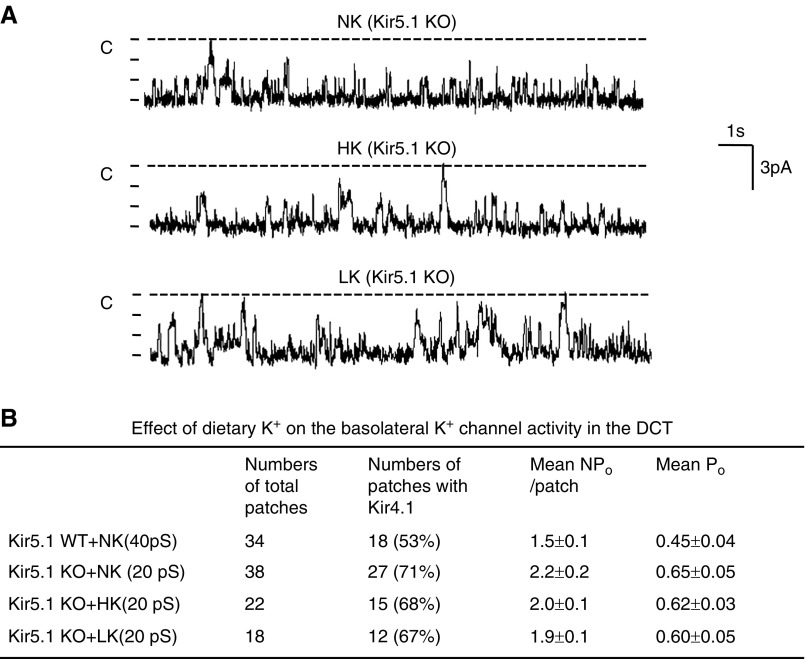

Deletion of Kir5.1 Abolished the Effect of HK Intake on Kir4.1 in DCT

We examined whether dietary K+ intake was still able to regulate basolateral K+ channels in the DCT in the absence of Kir5.1. We performed the single-channel study in the DCT of Kir5.1 KO mice on a normal K+ (NK), LK, or HK diet for 7 days (Figure 2A). The channel recordings show that neither HK nor LK has a significant effect on channel activity compared with the effects of NK. Figure 2B shows that the probability of finding basolateral 20-pS K+ channels was 71% in the DCT of Kir5.1 KO mice on NK diet (27 patches of 38 experiments). However, neither LK (67%, 12 patches of 18 experiments) nor HK (68%, 15 patches of 22 experiments) significantly changed the probability of finding 20-pS K+ channels in the DCT of Kir5.1 KO mice. This is in sharp contrast with WT mice in which HK decreased whereas LK increased the probability of finding the basolateral K+ channels in the DCT.4 Further analysis revealed that mean channel activity (defined by a product of channel number and open probability [NPo]) in the DCT (HK, NPo=2.0±0.1; NK, NPo=2.2±0.2; LK, NPo=1.9±0.1) was similar in the Kir5.1 KO mice on the different K+ diets.

Figure 2.

Deletion of Kir5.1 abolishes the effect of dietary K+ intake on the basolateral K+ channel in the DCT. (A) Representative single-channel recordings showing the basolateral K+ channel activity in the DCT of Kir5.1 KO mice on an NK, HK, or LK diet for 7 days, respectively. (B) Probability of finding basolateral K+ channel activity, mean NPo, and Po in the DCT of WT and Kir5.1 KO mice on NK, HK, and LK diets, respectively. NPo, a product of channel number and open probability; Po, open probability.

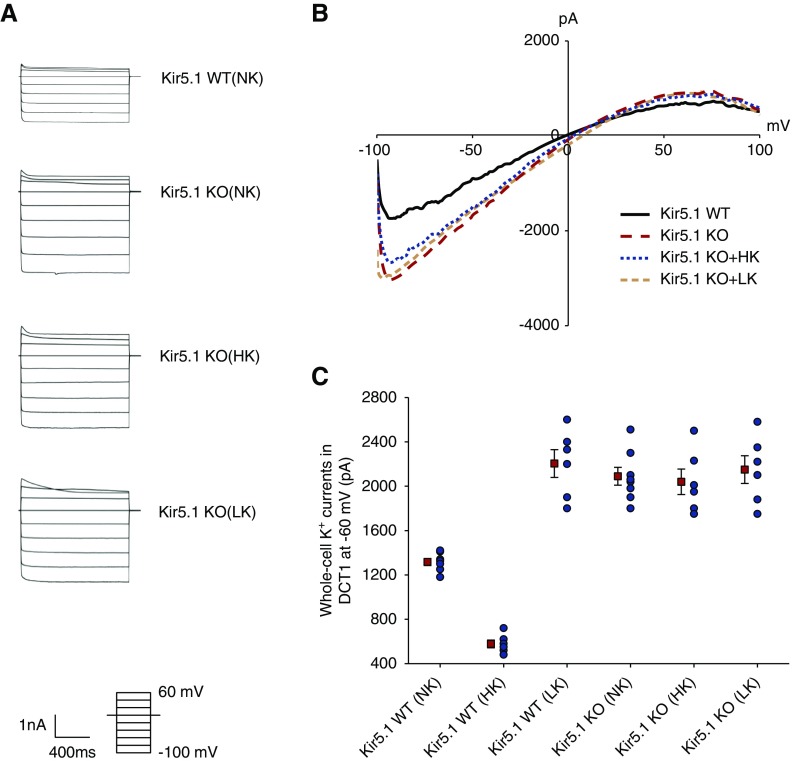

We confirmed that deletion of Kir5.1 abolishes the effect of dietary K+ intake on the basolateral Kir4.1 activity, using whole-cell recording. Figure 3A is a set of traces showing the whole-cell IKs measured with step protocol (−100 to 60 mV with 20-mV step) and Figure 3B is a set of traces demonstrating IKs measured with ramp protocol (−100 to 100 mV) in the DCT of WT mice on NK or Kir5.1 KO mice on HK, NK, and LK diets for 7 days, respectively. Although the deletion of Kir5.1 increased the basolateral IKs in the DCT (WT, 1318±32 pA at −60 mV; Kir5.1 KO, 2090±80 pA at −60 mV), the regulatory effect of dietary K+ intake on the basolateral K+ channel was completely absent in Kir5.1 KO mice. The IKs measured at −60 mV from six or seven experiments (tubules) are summarized in a scatter graph (Figure 3C) and a bar graph (Supplemental Figure 3A); they show that the whole-cell IKs at −60 mV were 2040±115 pA (HK) and 2150±125 pA (LK), values were not significantly different from NK. In contrast, we confirmed the previous finding that HK decreased (580±30 pA) whereas LK increased the IKs (2205±125 pA) in the WT mice (Figure 3C).4 These findings suggest that Kir5.1 is essential for the dietary K+ intake–induced regulation of basolateral K+ channels in the DCT.

Figure 3.

Deletion of Kir5.1 eliminates the effect of dietary K+ intake on the basolateral K+ conductance in the DCT. (A) A set of traces showing the barium-sensitive IKs measured with step protocol from –100 to 60 mV in the DCT1 of WT on NK and Kir5.1 KO mice on NK, HK, and LK diets for 7 days, respectively. (B) A set of recordings showing the barium -sensitive IKs measured with ramp protocol from –100 to 100 mV in the DCT1 of WT on NK and Kir5.1 KO mice on NK, HK, and LK diets for 7 days, respectively. (C) A scatter graph summarizes the values measured at –60 mV in the DCT1 of WT and Kir5.1 KO mice on different K+ diets with whole-cell recording. The mean value and SEM are shown on the left of each row.

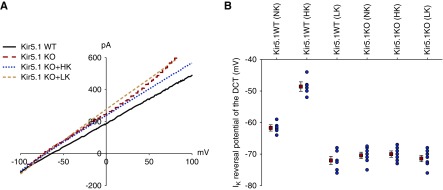

Measurement of IK reversal potential (an index of the membrane potential) also suggests that Kir5.1 plays a role in mediating dietary K+ intake on the basolateral K+ channels in the DCT. Figure 4A is a set of the traces showing IK reversal potential in the DCT from WT on NK and from Kir5.1 KO mice on NK (red), HK (blue), and LK (green), respectively. Figure 4B is a scatter graph showing the value of each measurement and mean value; Supplemental Figure 3B is a bar graph summarizing the results of six experiments (tubules) and the statistical analysis. IK reversal potentials of the DCT of WT on NK was −61.7±1 mV and it was −70.4±1 mV in the DCT of Kir5.1 KO mice on NK, suggesting the deletion of Kir5.1 hyperpolarized the membrane of the DCT. Moreover, dietary K+ intake failed to significantly alter IK reversal potential of the DCT in Kir5.1 KO mice (HK, −70±1 mV; LK, 71.4±1 mV). In contrast, we confirmed the previous finding that HK decreased (−48.6±1.5 mV) whereas LK increased IK reversal potential (−72±1.3 pA) in WT mice (Figure 4B).4 These results strongly indicate that Kir5.1 is required for the effect of dietary K+ intake on the basolateral K+ conductance of the DCT.

Figure 4.

Deletion of Kir5.1 hyperpolarizes DCT membrane. (A) A perforated whole-cell recording showing the IK reversal potential in the DCT of WT on NK and Kir5.1 KO mice on NK, HK, and LK diets for 7 days, respectively. (B) A scatter graph summarizes the results of experiments in which the IK reversal potentials were measured in WT and Kir5.1 KO mice on different K+ diets for 7 days. The mean value and SEM are shown on the left of each row. For the measurement of IK reversal potential, the bath solution contains 140 mM NaCl and 5 mM KCl and the pipette solution has 140 mM KCl.

Deletion of Kir5.1 Abolished the Effect of Dietary K+ Intake on NCC

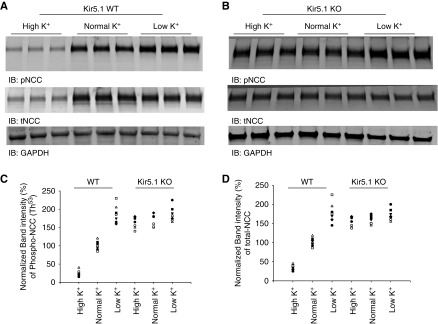

Because dietary K+–induced changes in DCT membrane potentials are associated with thiazide-sensitive NCC activity,4,24 we suspect that the effect of dietary K+ intake on NCC may be also compromised in Kir5.1 KO mice. Thus, we next examined the effect of dietary K+ intake on NCC in WT (Figure 5A) and Kir5.1 KO mice (Figure 5B) on HK, NK, and LK diets for 7 days, respectively (three or four male and three female mice for each group; full length of immunoblots are shown in Supplemental Figure 4). We confirmed the previous report that LK intake increased whereas HK intake decreased the expression of tNCC and pNCC (Thr53) in WT mice.3–8 The results are summarized in a scatter graph (Figure 5, C and D) and a bar graph (Supplemental Figure 5); they show that HK significantly decreased the expression of pNCC and tNCC to 25%±3% and 35%±3% of the control value (NK), respectively. Conversely, LK significantly increased the expression of pNCC and tNCC to 188%±10% and 180%±10% of the control value (NK). However, Figure 5B shows that HK failed to decrease the expression of tNCC and pNCC in Kir5.1 KO mice. Supplemental Figure 5, A and B are bar graphs summarizing the results for pNCC and tNCC, respectively. Although the expression of pNCC and tNCC in Kir5.1 KO mice on NK was 170%±6% and 159%±5% for WT mice on NK, HK failed to significantly decrease the expression of pNCC (165%±6%) and tNCC (153%±5%) in Kir5.1 KO mice. Also, LK did not significantly increase the expression of pNCC (185%±8%) and tNCC (173%±6%) in Kir5.1 KO mice.

Figure 5.

Deletion of Kir5.1 abolishes the effect of dietary K+ intake on tNCC and pNCC. An immunoblot (IB) showing the expression of pNCC and tNCC in (A) WT and in (B) Kir5.1 KO mice on NK, HK, and LK diets for 7 days, respectively. A scatter graph summarizes the normalized band intensity of the above experiments for (C) pNCC and (D) tNCC, respectively. GADPH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

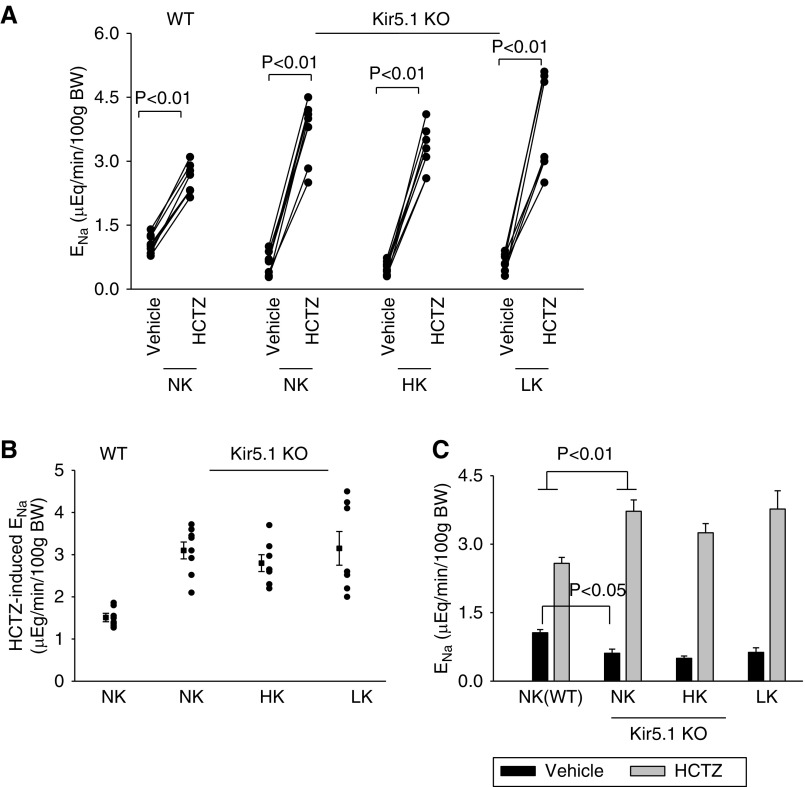

We confirmed that dietary K+ intake failed to alter the expression of NCC by examining the effect of HCTZ (25 mg/kg body wt) on urinary Na+ excretion (ENa) during renal clearance experiments. Figure 6A summarizes results from each individual experiment, Figure 6B is a scatter graph showing the Δ value of HCTZ-induced net ENa (before and after HCTZ), and Figure 6C is a bar graph demonstrating the mean value and statistical information from four male and three to four female mice for each group. Figure 6 shows that there was significantly greater HCTZ-induced natriuresis in Kir5.1 KO mice on NK (0.61±0.1 to 3.72±0.25 μEq/min per 100 g body wt) than in WT (1.06±0.07 to 2.58±0.13 μEq/min per 100 g body wt). Moreover, HK intake for 7 days failed to significantly decrease HCTZ-induced ENa in the Kir5.1KO mice (from 0.50±0.05 to 3.25 ±0.19 μEq/min per 100 g body wt). Also, LK diet for 7 days did not significantly increase HCTZ-induced natriuresis (from 0.63±0.1 to 3.77 ±0.41 μEq/min per 100 g body wt). Thus, the deletion of Kir5.1 abolished the stimulatory effect of LK on NCC and the inhibitory effect of HK on NCC.

Figure 6.

Deletion of Kir5.1 augments NCC function and abolishes the effect of dietary K+ intake on NCC function. (A) A scatter line graph showing the results of each experiment in which the effect of single-dose HCTZ (25 mg/L per kg body wt) on urinary ENa within 120 minutes was measured with the renal clearance method in WT on NK and Kir5.1 KO mice on NK, HK, and LK diets for 7 days, respectively. The significance is determined by t test. (B) A scatter graph shows the HCTZ-induced net ENa from the above experiments. The mean value and SEM are shown on the left of each row. (C) A bar graph summarizes the above results showing the mean values and statistical information. One-way ANOVA was used to determine the significance.

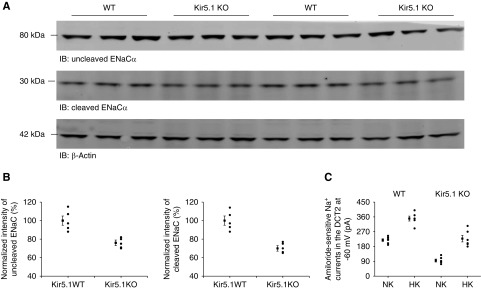

Deletion of Kir5.1 Decreased ENaC Activity

Although the NCC activity was upregulated in Kir5.1 KO mice, the previous study showed that the Kir5.1 KO mice had a normal BP and a similar urinary ENa compared with the WT mice.15 We speculate that the downregulation of ENaC activity may be, at least partially, responsible for maintaining a relatively normal Na+ absorption despite high NCC activity. Thus, we next examined the expression of ENaCα in WT and Kir5.1 KO mice (Figure 7A, Supplemental Figure 6A). Figure 7B is a set of scatter graphs and Supplemental Figure 6B is a bar graph showing the normalized band density of ENaCα (noncleaved and cleaved) and corresponding statistical information. The full-length ENaCα (76%±3% of WT control) and the cleaved ENaCα (70%±3% of WT control) were expressed less in Kir5.1 KO mice than in WT mice. For further evidence that ENaC is inhibited in Kir5.1 KO mice, we performed patch-clamp experiments in which amiloride-sensitive Na+ currents in the DCT were measured at −60 mV using whole-cell recording in the WT and Kir5.1 KO mice (Figure 7C, Supplemental Figure 6C). The amiloride-sensitive Na+ currents (95±9 pA, n=6) in Kir5.1 KO mice on NK were significantly lower than in those of WT mice (219±8 pA, n=5). High dietary K+ intake for 7 days significantly stimulated the ENaC of the DCT in both WT and Kir5.1 KO mice. However, the Na+ current in Kir5.1 KO mice on HK (228±20 pA, n=6) was significantly smaller than in WT mice (350±15 pA, n=6). Thus, it is possible that the downregulation of ENaC activity in Kir5.1 KO mice may be due to a compensatory mechanism of high NCC activity.

Figure 7.

ENaC activity is downregulated in Kir5.1 KO mice. (A) An immunoblot showing the expression of noncleaved ENaC-α and cleaved ENaC-α in Kir5.1 WT and Kir5.1 KO mice on NK. (B) A scatter graph summarizes the normalized band intensity of the above experiments for noncleaved ENaC-α and cleaved ENaC-α, respectively. The mean value and SEM are shown on the left of each row. (C) A scatter graph summarizes the results of experiments in which amiloride (0.1 mM)-sensitive Na+ currents were measured at −60 mV with perforated whole-cell recording in DCT2 of Kir5.1 WT and Kir5.1 KO mice on NK or HK diets for 7 days, respectively. The mean value and SEM are shown on the left of each row. IB, immunoblot.

Renal Ability for EK Is Compromised in Kir5.1 KO Mice

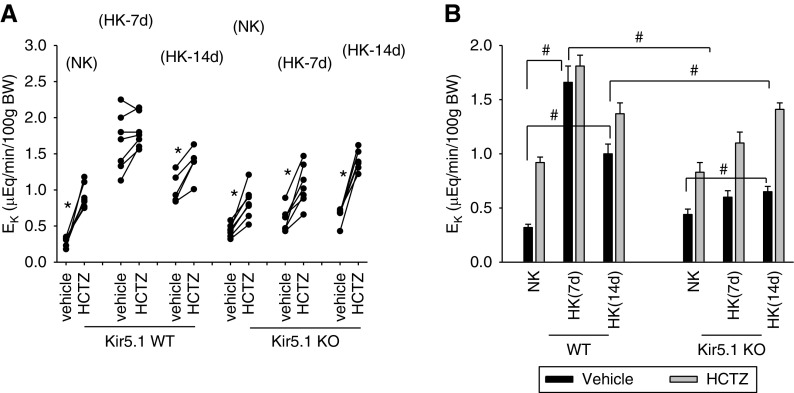

Because HK-induced inhibition of NCC was compromised in Kir5.1 KO mice, we speculated that renal ability to stimulate EK may be impaired in Kir5.1 KO mice on a HK diet. Thus, we used the renal clearance method to examine the effect of a HK diet for 1 or 2 weeks on renal EK in WT and Kir5.1 KO mice. Figure 8A is a line graph demonstrating the result of each experiment (three to four male and three female mice for each group) in which we have examined the effect of HCTZ on renal EK in WT and Kir5.1 KO mice on NK and HK diets for 7 or 14 days; Figure 8B is a bar graph showing the mean values and statistical information. The EK under basal (vehicle) conditions was 0.32±0.03 μEq/min per 100 g body wt in WT mice on NK and it increased to 1.66±0.15 and 1.01±0.1 μEq/min per 100 g body wt in WT mice on HK for 7 and 14 days, respectively. Although HCTZ significantly increased EK in WT mice on NK from 0.32±0.03 to 0.92±0.05 μEq/min per 100 g body wt, HCTZ had no additional effect on EK (from 1.66±0.15 to 1.81±0.1 μEq/min per 100 g body wt) in WT mice on HK for 7 days. The application of HCTZ slightly but significantly increased EK from 1.01±0.1 to 1.37±0.1 μEq/min per 100 g body wt in the WT mice on HK for 14 days.

Figure 8.

Deletion of Kir5.1 impairs renal ability for EK during HK intake. (A) A line graph showing the results of each experiment in which the effect of single-dose HCTZ on EK within 120 minutes was measured with the renal clearance method in WT and Kir5.1 KO mice on NK and HK (7 and 14 days). Asterisk indicates the significant difference between vehicle and HCTZ treatment determined by paired-t test: *P<0.05. (B) A bar graph shows the mean values of EK and statistical information for all above experiments. # indicates the difference is significant with one-way ANOVA. #P<0.05.

Application of HCTZ increased EK from 0.44±0.04 (vehicle or basal level) to 0.83±0.09 μEq/min per 100 g body wt in Kir5.1 KO mice on a NK diet. The basal level of EK was 0.6±0.06 μEq/min per 100 g body wt (HK diet for 7 days) and 0.65±0.05 μEq/min per 100 g body wt (HK diet for 14 days) in Kir5.1 KO mice; values were significantly lower than the corresponding values in WT on HK for 7 or 14 days. This suggests that the deletion of Kir5.1 impairs renal K+ secretion in response to increased dietary K+ intake. Furthermore, the application of HCTZ increased EK from 0.6±0.06 to 1.1±0.1 μEq/min per 100 g body wt and from 0.65±0.05 to 1.41±0.1 μEq/min per 100 g body wt in Kir5.1 KO mice on a HK diet for 7 days and 14 days, respectively. This suggests that compromised renal ability for EK was due to high NCC activity in Kir5.1 KO mice on a HK diet. This view was also supported by experiments in which we examined the effect of HCTZ-induced natriuresis in Kir5.1 KO mice on a HK diet for 2 weeks.

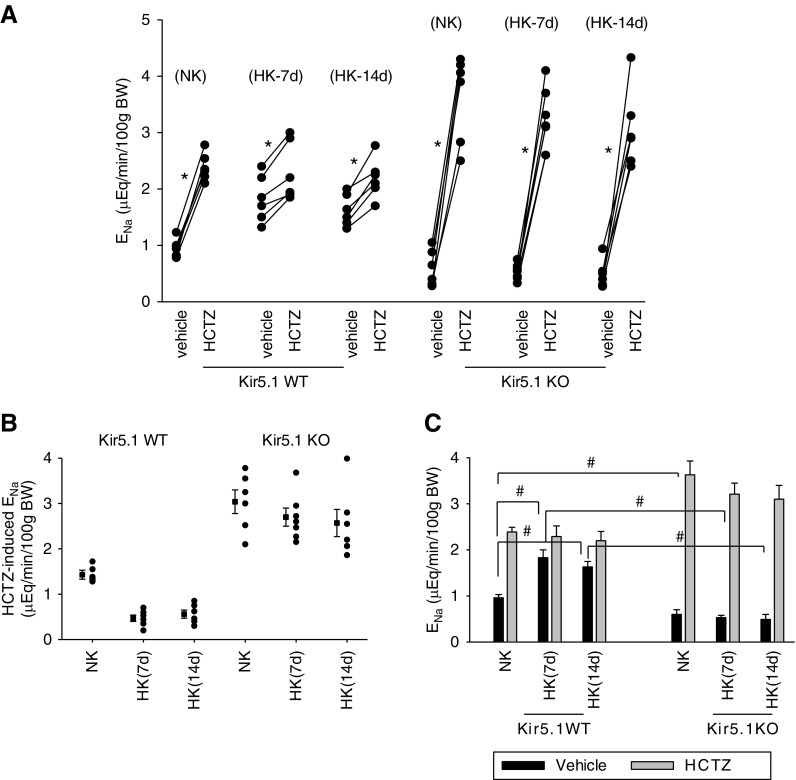

Figure 9A is a line graph showing the results from each experiment (three to four male and three female mice for each group) in which we have examined the effect of HCTZ on ENa in WT and Kir5.1KO mice on an NK or HK diet for 7 or 14 days, Figure 9B is a scatter graph summarizing the Δ value of HCTZ-induced net ENa, and Figure 9C is a bar graph showing the statistical analysis from above experiments. It is clear that HK intake for 2 weeks also decreased HCTZ-induced natriuresis in WT mice,4 indicating the inhibition of NCC. Application of HCTZ increased ENa from 0.96±0.07 to 2.39±0.1 μEq/min per 100 g body wt in WT mice on NK. HK intake increased the basal level of ENa and diminished HCTZ-induced ENa in WT mice. HCTZ application increased ENa from 1.83±0.17 to 2.29±0.23 μEq/min per 100 g body wt in WT mice on HK for 7 days and from 1.63±0.12 to 2.20±0.20 μEq/min per 100 g body wt in WT mice on HK for 14 days. In contrast, prolonged increased HK intake still failed to inhibit NCC in Kir5.1 KO mice because HCTZ-induced natriuresis remained similar between NK and HK. It is clear from Figure 9B that the net ENa induced by HCTZ is not significantly changed (NK, 3.04±0.26; 7 days HK, 2.7±0.2; 14 days HK, 2.57±0.3 μEq/min per 100 g body wt) in the Kir5.1 KO mice. Figure 9C shows that HCTZ increased ENa from 0.60±0.1 to 3.63±0.3 μEq/min per 100 g body wt in Kir5.1 KO mice on NK, from 0.53±0.05 to 3.21±0.24 μEq/min per 100 g body wt in Kir5.1 KO mice on HK for 7 days, and from 0.49±0.11 to 3.10±0.3 μEq/min per 100 g body wt in Kir5.1 KO mice on HK for 14 days. Thus, a prolonged dietary K+ intake was not able to inhibit NCC in Kir5.1 KO mice.

Figure 9.

High NCC activity is sustained in Kir5.1 KO mice on 14 days of an HK diet. (A) A line graph showing the results of each experiment in which the effect of single-dose HCTZ (25 mg/L per kg body wt) on ENa within 120 minutes was measured with the renal clearance method in WT and Kir5.1 KO mice on NK and HK (7 [7d] and 14 days [14d]). Asterisk indicates the significant difference between vehicle and HCTZ treatment (determined by paired t test): *P<0.05. (B) A scatter graph shows the HCTZ-induced net ENa from the above experiments. The mean value and SEM are shown on the left of each row. (C) A bar graph shows the mean values of ENa and statistical information for all above experiments. # indicates significant difference determined by one-way ANOVA: #P<0.05.

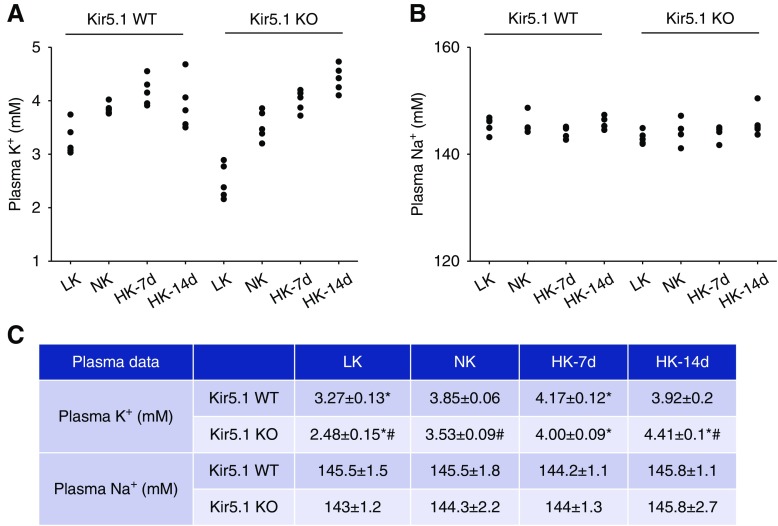

Consequently, the plasma K+ in Kir5.1 KO mice on HK significantly and progressively increased from 3.53±0.09 mM (NK) to 4.00±0.09 mM (HK for 7 days) and 4.41±0.1 mM (HK for 14 days) (Figure 10, A and C). In contrast, plasma K+ in WT mice slightly but significantly increased from 3.85±0.06 mM (NK) to 4.17±0.12 mM (HK for 7 days). However, the plasma K+ in WT mice on HK for 14 days was almost back to normal (3.92±0.2 mM) (Figure 9C). Figure 9, B and C show that the mean plasma Na+ levels in both WT and Kir5.1 KO mice were not significantly changed.

Figure 10.

Kir5.1 KO mice are hyperkalemic during increased K+ intake and hypokalemic during K+ restriction. A scatter graph showing (A) plasma K+ concentrations and (B) Na+ concentrations in WT and Kir5.1 KO mice on LK (7 days), NK, HK (7 days [7d]), and HK (14 days [14d]), respectively. (C) The mean value and SEM of above measurements are summarized in the table. Asterisk indicates significant difference compared with the corresponding control (NK), determined by one-way ANOVA. # indicates a significant difference between WT and Kir5.1 KO mice on the same K+ diet, determined by unpaired t test. *P<0.05, #P<0.05.

Renal Ability of Preserving K+ Was Compromised in Kir5.1 KO Mice

We next used the renal clearance method to investigate the effect of an LK diet (7 days) on EK in WT and Kir5.1 KO mice. Supplemental Figure 7A is a scatter graph showing results from each individual experiment and Supplemental Figure 7B is a bar graph summarizing the mean values and statistical information (three male and three female mice). The basal levels of EK in Kir5.1 KO mice had a trend to be higher than the corresponding value of WT mice on either NK (0.44±0.05 versus 0.32±0.03 μEq/min per 100 g body wt for Kir5.1 KO and WT mice, respectively) or LK diet for 7 days (0.06±0.01 versus 0.04±0.01 μEq/min per 100 g body wt for Kir5.1 KO and WT mice, respectively), although the difference was NS. Moreover, HCTZ increased EK similarly in both WT and Kir5.1 KO mice on LK for 7 days (Kir5.1 KO mice from 0.06±0.01 to 0.11±0.03 μEq/min per 100 g body wt; WT mice from 0.04±0.01 to 0.095±0.02 μEq/min per 100 g body wt). Although the renal clearance study did not find any significant difference in Kir5.1 KO mice and WT mice on a LK diet, the measurement of plasma K+ in WT and Kir5.1 KO mice suggests that the deletion of Kir5.1 also impairs the renal ability to preserve K+ during K+ restriction. Figure 10C shows that plasma K+ in WT mice on an LK diet for 7 days (3.27±0.13 mM) was significantly higher than in Kir5.1 KO mice on LK for 7 days (2.48±0.2 mM) (Figure 10C). This suggests that deletion of Kir5.1 not only impairs the renal ability to excrete K+ during increased dietary K+ intake, but also the ability for preserving K+ during K+ restriction. However, considering that NCC activity in Kir5.1 KO mice on an LK diet was similar to WT mice on an LK diet, hypokalemia in Kir5.1 KO mice on LK may be caused by compromised membrane transport in the nephron other than the DCT, because Kir5.1 is also expressed in nephron segments other than the DCT.

Discussion

A main finding of this study is that the deletion of Kir5.1 abolishes the effect of dietary K+ intake on the basolateral K+ conductance in the DCT. Our previous experiments demonstrated that increased dietary K+ intake inhibited the basolateral K+ channel and depolarized the DCT membrane, whereas decreased dietary K+ intake increased the basolateral K+ channel and hyperpolarized the DCT membrane.4,10,11 The effect of HK intake on the membrane potential is related to K+ intake rather than Cl− intake because the IK reversal potential of the DCT in mice on an HK diet containing 1% Cl (citrate replaced the rest of the Cl−) is the same as in those containing high Cl− (D. Lin, data not shown). Because Cl− movement across the basolateral Cl− channel is an electrogenic process,25 HK-induced depolarization is expected to increase the intracellular Cl− concentrations, whereas LK-induced hyperpolarization should decrease the intracellular Cl− concentrations. Because with-no-lysine kinase (WNK), which plays a key role in activating NCC,26 is a Cl−-sensitive protein kinase,9,27,28 high Cl− concentrations should inhibit and low Cl− concentrations should stimulate WNK and Ste20-proline-alanine-rich protein kinase (SPAK), a downstream kinase of WNK for the activation of NCC.29–34 Thus, HK-induced inhibition of basolateral K+ channels in the DCT should inactivate WNK-SPAK, whereas LK-induced stimulation of the basolateral K+ channel should have an opposite effect. This view is supported by the previous finding that SPAK activity was low in kidney-specific Kir4.1 KO mouse in which the membrane potential was depolarized in the DCT.10 Because WNK-SPAK activity determines NCC activity,9,35,36 HK intake inhibits and LK intake stimulates NCC. Thus, the regulation of basolateral K+ channels in the DCT plays an important role in the modulation of NCC activity in response to dietary K+ intake. In this regard, it is conceivable that the absence of dietary K+ intake–induced changes in NCC activity of Kir5.1 KO mice is due to the lack of dietary K+ intake–induced alteration of the basolateral K+ conductance in the DCT. In addition, the deletion of Kir5.1 may cause tubule remodeling which may be involved in compromised regulation of NCC by dietary K+ intake. To address this possibility, we have measured the total length of the NCC-positive tubules (in a given area) in WT and Kir5.1 KO mice (three kidneys for each group). Supplemental Figure 8 is an immunostaining image of NCC in WT and Kir5.1 KO mice showing that there is no obvious difference in the total DCT length between WT and Kir5.1 KO mice. In addition, by measuring mean length of isolated DCTs (eight to nine tubules) from WT and Kir5.1 KO mice, we did not observe obvious difference between the two groups. However, a separate and more sophisticated experiment is required to further address whether the deletion of Kir5.1 causes DCT tubule remodeling.

The basolateral K+ channel in the DCT is composed of two inwardly rectifying K+ channels, Kir4.1 and Kir5.1.12,18 Although Kir4.1 can form a 20- to 25-pS homotetramer in the basolateral membrane in the absence of Kir5.1, under physiologic conditions, Kir4.1 interacts with Kir5.1 to form a 40-pS K+ channel (Kir4.1/Kir5.1 heterotetramer) in the DCT.12,14,16 Previous studies have convincingly demonstrated that Kir4.1 was responsible for providing K+ conductance of the Kir4.1/Kir5.1 heterotetramer because the deletion of Kir4.1 completely eliminated the basolateral K+ conductance in the DCT.4,10,11,18 In contrast, the deletion of Kir5.1 increased rather than decreased basolateral K+ conductance in the DCT.13 This finding is also confirmed by these experiments demonstrating that the deletion of Kir5.1 increases the basolateral K+ conductance. Thus, experiments by us and others strongly suggest that Kir5.1 is a regulatory subunit which may play a role in suppressing Kir4.1 activity during increased dietary K+ intake or in augmenting Kir4.1 activity during K+ restriction. The notion that Kir5.1 regulates the basolateral K+ channels in the DCT is supported by the observation that neither HK nor LK intake affects the basolateral K+ channel activity in the DCT of Kir5.1 KO mice.

The mechanism by which Kir5.1 regulates Kir4.1 activity or expression is not completely understood. Previous studies showed that the Kir4.1/Kir5.1 heterotetramer was more pH sensitive than the Kir4.1 homotetramer, suggesting that Kir5.1 regulates the pH sensitivity of the K+ channel.37,38 However, changes in pH sensitivity of Kir4.1/5.1 could not explain the finding that the deletion of Kir5.1 increased the expression of Kir4.1.13,14 This suggests the possibility that Kir5.1 regulates Kir4.1 by a mechanism other than changing pH sensitivity. Indeed, our previous experiments demonstrated that Kir5.1 inhibited Kir4.1 activity in the presence of the E3 ubiquitin ligase Nedd4-2.13 We observed that Kir5.1 was able to bind Nedd4-2 in its carboxy terminus and that coexpression of Kir5.1 and nedd4-2 facilitated the ubiquitination of Kir4.1 in vitro. In vivo animal experiments also support the notion that Kir5.1 may inhibit Kir4.1 activity through Nedd4-2–mediated ubiquitination. We observed that the expression of Kir4.1 is significantly upregulated not only in Kir5.1 KO mice but also in kidney-specific Nedd4-2 KO mice (Supplemental Figure 9A),13 suggesting that Nedd4-2 and Kir5.1 are involved in the inhibition of Kir4.1 by a similar mechanism. Moreover, the increase in Kir4.1 expression induced by Kir5.1 deletion is unlikely to be caused by decreasing Nedd4-2 expression, because the Nedd4-2 expression level in Kir5.1 KO mice is similar to WT (Supplemental Figure 9B). Also, using the real-time PCR technique, we detected that the expression of Nedd4-2 in the DCT was similar to that in the cortical collecting duct (Supplemental Figure 9C). However, further experiments are required to examine the role of the Kir5.1–Nedd4-2 interaction in mediating the inhibitory effect of HK intake on the basolateral K+ channel activity in the DCT.

The DCT is an important nephron segment regulating EK by controlling the NCC activity such that HK intake inhibits whereas LK intake stimulates NCC.1,3,24,39,40 The inhibition of NCC is essential for HK-induced stimulation of renal EK because it increases the Na+ and fluid volume delivery to the ASDN, thereby stimulating ENaC-dependent EK or flow-stimulated EK.41,42 Conversely, the stimulation of NCC induced by LK intake should suppress the renal EK, thereby preserving K+ during decreased dietary K+ intake. The role of Kir5.1 of the DCT in mediating the effect of HK intake on NCC is strongly suggested by the observation that HK failed to decrease the expression and activity of NCC in Kir5.1 KO mice. Because the downregulation of NCC is required for stimulating EK in the late ASDN, high NCC activity in Kir5.1 KO mice on an HK diet is expected to impair the renal ability of EK during increased dietary K+ intake. This notion is supported by two lines of evidence: first, the renal clearance study showed that the basal level (vehicle) of renal EK was significantly lower in Kir5.1 KO mice on an HK diet than in WT mice on an HK diet, suggesting a diminished renal EK. Second, feeding Kir5.1 KO mice with an HK diet for 2 weeks progressively raised the plasma K+, whereas the same manipulations did not significantly increase the plasma K+ levels in WT mice. These findings strongly suggest that Kir5.1 is essential for properly regulating renal K+ secretion during increased dietary K+ intake.

This study has also confirmed the previous report that Kir5.1 KO mice on an NK diet were slightly hypokalemic rather than hyperkalemic,15 although increased NCC activity would be expected to decrease the renal K+ secretion. This paradox may be caused by the fact that Kir5.1 is also expressed in the nephron segments other than the DCT/connecting tubule; the deletion of Kir5.1 in the kidney may also affect K+ transport in other nephron segments such as in the proximal tubule. Although further experiments are required to examine whether Kir5.1 deletion impairs K+ transport in the proximal tubule, the finding that the expression of Kir4.2 is significantly decreased in Kir5.1 KO mice in comparison to WT mice has proved the principal. Because Kir4.2 is coexpressed in the basolateral membrane of the proximal tubule (M. Paulais, personal communication) with Kir5.1,37,43 it is conceivable that K+ recycling across the basolateral membrane by Kir4.2 should be compromised in the proximal tubule. Thus, the deletion of Kir5.1 might affect K+ reabsorption in the proximal tubule, thereby increasing K+ delivery to the ASDN. Consequently, compromised K+ transport in the proximal tubule may increase K+ load to the ASDN, thereby offsetting the effect of high NCC activity on renal EK. The finding that Kir5.1 KO mice on LK diet were more hypokalemic than WT littermates also suggested the possibility that deletion of Kir5.1 may affect the K+ transport in the proximal tubule. The notion that the DCT may not be mainly responsible for severe hypokalemia of Kir5.1 KO mice on an LK diet was suggested by the finding that the expression and activity of NCC in Kir5.1 KO mice on an LK diet were similar to those in WT mice. However, because NCC activity is high in Kir5.1 KO mice under control conditions (NK), the kidney has lost one important mechanism in the DCT to make a proper adjustment in response to changes in the Na+ and K+ transport in the proximal tubule. Consequently, Kir5.1 KO mice on LK were more hypokalemic than WT mice.

In this study, we observed that ENaC activity and ENaCα expression are modestly decreased in Kcnj16 KO mice compared with WT mice. However, the expression of ENaC-α was increased in salt-sensitive (SS) Kcnj16−/− rats on a diet containing 4% Na+ plus HK compared with WT rats.14 The discrepancy between the two studies may be the result of different genetic backgrounds between SS Kcnj16−/− rats and Kir5.1 KO mice. For instance, the regulation of ENaC is abnormal in SS Kcnj16−/− rats, as evidenced by the fact that high Na+ intake has been shown to stimulate ENaC activity rather than to inhibit ENaC. The high ENaC activity in SS Kcnj16−/− rats may be responsible for the high mortality of the animals fed with a high Na+ diet, because increased Na+ absorption by ENaC is expected to exacerbate renal K+ wasting and lead to severe hypokalemia. Thus, the HK diet compensated for renal K+ wasting in SS Kcnj16−/− rats, thereby decreasing the animal’s mortality. On the other hand, Paulais et al.15 have reported that the expression of full-length ENaC-α was not significantly different from the WT. Also, amiloride-induced natriuresis was similar between WT and Kcnj16 KO mice.15 We speculate that this discrepancy between the two studies may be induced by different Na+ contents in the diets used (0.25% versus 0.4%) and different experimental conditions. Since the amiloride test in Paulais et al.’s study has been performed in vivo, ENaC activity could be affected by factors that were not present in isolated DCT. Finally, low ENaC activity in our study is consistent with decreased aldosterone levels in Kir5.1 KO mice or rats.14,15

The physiologic significance of this study is to further establish the role of the Kir4.1/Kir5.1 heterotetramer of the DCT in the regulation of renal EK and K+ homeostasis during hyperkalemia and hypokalemia. Although the activity of Kir4.1 determines the basolateral K+ conductance and DCT membrane potential, Kir5.1 regulates the Kir4.1 activity in the DCT during increased or decreased dietary K+ intake. Therefore, neither Kir4.1 nor Kir5.1 in the DCT is dispensable for a proper regulation of renal EK. We conclude that the Kir5.1 in the DCT plays a key role in mediating the effect of dietary K+ intake on the basolateral K+ conductance, DCT membrane potential, and NCC activity. Therefore, the presence of Kir5.1 in the DCT is important for maintaining body K+ homeostasis and for the regulation of renal EK.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

The work is supported by National Institutes of Health grants DK 54983 (to Dr. Wang) and DK 115366 (to Dr. Lin).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms. Gail Anderson for editing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2019010025/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Appendix 1: Methods.

Supplemental Figure 1. Deletion of Kir5.1 increases basolateral K+ conductance.

Supplemental Figure 2. Deletion of Kir5.1 NCC expression.

Supplemental Figure 3. Deletion of Kir5.1 eliminates the effect of dietary K+ intake on the basolateral K+ conductance in the DCT.

Supplemental Figure 4. Deletion of Kir5.1 abolishes the effect of dietary K+ intake on tNCC and pNCC.

Supplemental Figure 5. Deletion of Kir5.1 abolishes the effect of dietary K+ intake on tNCC and pNCC.

Supplemental Figure 6. ENaC activity is down-regulated in Kir5.1 KO mice.

Supplemental Figure 7. K+ restriction decreases urinary K+ excretion in Kir5.1 KO mice.

Supplemental Figure 8. DCT tubule length of WT and Kir5.1 KO mice.

Supplemental Figure 9. Kir4.1 expression is increased in Ks-Nedd4-2 KO WT mice.

References

- 1.Frindt G, Palmer LG: Effects of dietary K on cell-surface expression of renal ion channels and transporters. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 299: F890–F897, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim GH, Masilamani S, Turner R, Mitchell C, Wade JB, Knepper MA: The thiazide-sensitive Na-Cl cotransporter is an aldosterone-induced protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95: 14552–14557, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rengarajan S, Lee DH, Oh YT, Delpire E, Youn JH, McDonough AA: Increasing plasma [K+] by intravenous potassium infusion reduces NCC phosphorylation and drives kaliuresis and natriuresis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 306: F1059–F1068, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang MX, Cuevas-Gallardo C, Su XT, Wu P, Gao ZX, Lin DH, et al.: Potassium intake modulates the thiazide-sensitive sodium-chloride cotransporter (NCC) activity via the Kir4.1 potassium channel. Kidney Int 93: 893–902, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang L, Xu S, Guo X, Uchida S, Weinstein AM, Wang T, et al.: Regulation of renal Na transporters in response to dietary K. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 315: F1032–F1041, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castañeda-Bueno M, Cervantes-Perez LG, Rojas-Vega L, Arroyo-Garza I, Vázquez N, Moreno E, et al. : Modulation of NCC activity by low and high K(+) intake: Insights into the signaling pathways involved. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 306: F1507–F1519, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vallon V, Schroth J, Lang F, Kuhl D, Uchida S: Expression and phosphorylation of the Na+-Cl- cotransporter NCC in vivo is regulated by dietary salt, potassium, and SGK1. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F704–F712, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Penton D, Czogalla J, Wengi A, Himmerkus N, Loffing-Cueni D, Carrel M, et al.: Extracellular K+ rapidly controls NaCl cotransporter phosphorylation in the native distal convoluted tubule by Cl- -dependent and independent mechanisms. J Physiol 594: 6319–6331, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Terker AS, Zhang C, Erspamer KJ, Gamba G, Yang CL, Ellison DH: Unique chloride-sensing properties of WNK4 permit the distal nephron to modulate potassium homeostasis. Kidney Int 89: 127–134, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cuevas CA, Su XT, Wang MX, Terker AS, Lin DH, McCormick JA, et al.: Potassium sensing by renal distal tubules requires Kir4.1. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 1814–1825, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang C, Wang L, Zhang J, Su XT, Lin DH, Scholl UI, et al.: KCNJ10 determines the expression of the apical Na-Cl cotransporter (NCC) in the early distal convoluted tubule (DCT1). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111: 11864–11869, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lourdel S, Paulais M, Cluzeaud F, Bens M, Tanemoto M, Kurachi Y, et al.: An inward rectifier K(+) channel at the basolateral membrane of the mouse distal convoluted tubule: Similarities with Kir4-Kir5.1 heteromeric channels. J Physiol 538: 391–404, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang MX, Su XT, Wu P, Gao ZX, Wang WH, Staub O, et al.: Kir5.1 regulates Nedd4-2-mediated ubiquitination of Kir4.1 in distal nephron. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 315: F986–F996, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palygin O, Levchenko V, Ilatovskaya DV, Pavlov TS, Pochynyuk OM, Jacob HJ, et al.: Essential role of Kir5.1 channels in renal salt handling and blood pressure control. JCI Insight 2: e92331, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paulais M, Bloch-Faure M, Picard N, Jacques T, Ramakrishnan SK, Keck M, et al.: Renal phenotype in mice lacking the Kir5.1 (Kcnj16) K+ channel subunit contrasts with that observed in SeSAME/EAST syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108: 10361–10366, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang C, Wang L, Thomas S, Wang K, Lin DH, Rinehart J, et al.: Src family protein tyrosine kinase regulates the basolateral K channel in the distal convoluted tubule (DCT) by phosphorylation of KCNJ10 protein. J Biol Chem 288: 26135–26146, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lachheb S, Cluzeaud F, Bens M, Genete M, Hibino H, Lourdel S, et al.: Kir4.1/Kir5.1 channel forms the major K+ channel in the basolateral membrane of mouse renal collecting duct principal cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294: F1398–F1407, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Su XT, Wang WH: The expression, regulation, and function of Kir4.1 (Kcnj10) in the mammalian kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 311: F12–F15, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Su XT, Zhang C, Wang L, Gu R, Lin DH, Wang WH: Disruption of KCNJ10 (Kir4.1) stimulates the expression of ENaC in the collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 310: F985–F993, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang C, Wang L, Su XT, Lin DH, Wang WH: KCNJ10 (Kir4.1) is expressed in the basolateral membrane of the cortical thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 308: F1288–F1296, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pessia M, Tucker SJ, Lee K, Bond CT, Adelman JP: Subunit positional effects revealed by novel heteromeric inwardly rectifying K+ channels. EMBO J 15: 2980–2987, 1996 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duan XP, Gu L, Xiao Y, Gao ZX, Wu P, Zhang YH, et al.: Norepinephrine-induced stimulation of Kir4.1/Kir5.1 is required for the activation of NaCl transporter in distal convoluted tubule. Hypertension 73: 112–120, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu P, Gao ZX, Su XT, Wang MX, Wang WH, Lin DH: Kir4.1/Kir5.1 activity is essential for dietary sodium intake-induced modulation of Na-Cl cotransporter. J Am Soc Nephrol 30: 216–227, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Terker AS, Zhang C, McCormick JA, Lazelle RA, Zhang C, Meermeier NP, et al.: Potassium modulates electrolyte balance and blood pressure through effects on distal cell voltage and chloride. Cell Metab 21: 39–50, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lourdel S, Paulais M, Marvao P, Nissant A, Teulon J: A chloride channel at the basolateral membrane of the distal-convoluted tubule: A candidate ClC-K channel. J Gen Physiol 121: 287–300, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lalioti MD, Zhang J, Volkman HM, Kahle KT, Hoffmann KE, Toka HR, et al.: Wnk4 controls blood pressure and potassium homeostasis via regulation of mass and activity of the distal convoluted tubule. Nat Genet 38: 1124–1132, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bazúa-Valenti S, Gamba G: Revisiting the NaCl cotransporter regulation by with-no-lysine kinases. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 308: C779–C791, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piala AT, Moon TM, Akella R, He H, Cobb MH, Goldsmith EJ: Chloride sensing by WNK1 involves inhibition of autophosphorylation. Sci Signal 7: ra41, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grimm PR, Coleman R, Delpire E, Welling PA: Constitutively active SPAK causes hyperkalemia by activating NCC and remodeling distal tubules. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 2597–2606, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kahle KT, Ring AM, Lifton RP: Molecular physiology of the WNK kinases. Annu Rev Physiol 70: 329–355, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ponce-Coria J, Markadieu N, Austin TM, Flammang L, Rios K, Welling PA, et al.: A novel Ste20-related proline/alanine-rich kinase (SPAK)-independent pathway involving calcium-binding protein 39 (Cab39) and serine threonine kinase with no lysine member 4 (WNK4) in the activation of Na-K-Cl cotransporters. J Biol Chem 289: 17680–17688, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.San-Cristobal P, Pacheco-Alvarez D, Richardson C, Ring AM, Vazquez N, Rafiqi FH, et al.: Angiotensin II signaling increases activity of the renal Na-Cl cotransporter through a WNK4-SPAK-dependent pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106: 4384–4389, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferdaus MZ, Barber KW, López-Cayuqueo KI, Terker AS, Argaiz ER, Gassaway BM, et al.: SPAK and OSR1 play essential roles in potassium homeostasis through actions on the distal convoluted tubule. J Physiol 594: 4945–4966, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thastrup JO, Rafiqi FH, Vitari AC, Pozo-Guisado E, Deak M, Mehellou Y, et al.: SPAK/OSR1 regulate NKCC1 and WNK activity: Analysis of WNK isoform interactions and activation by T-loop trans-autophosphorylation. Biochem J 441: 325–337, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCormick JA, Mutig K, Nelson JH, Saritas T, Hoorn EJ, Yang C-L, et al.: A SPAK isoform switch modulates renal salt transport and blood pressure. Cell Metab 14: 352–364, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grimm PR, Taneja TK, Liu J, Coleman R, Chen YY, Delpire E, et al.: SPAK isoforms and OSR1 regulate sodium-chloride co-transporters in a nephron-specific manner. J Biol Chem 287: 37673–37690, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tucker SJ, Imbrici P, Salvatore L, D’Adamo MC, Pessia M: pH dependence of the inwardly rectifying potassium channel, Kir5.1, and localization in renal tubular epithelia. J Biol Chem 275: 16404–16407, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tanemoto M, Kittaka N, Inanobe A, Kurachi Y: In vivo formation of a proton-sensitive K+ channel by heteromeric subunit assembly of Kir5.1 with Kir4.1. J Physiol 525: 587–592, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sorensen MV, Grossmann S, Roesinger M, Gresko N, Todkar AP, Barmettler G, et al.: Rapid dephosphorylation of the renal sodium chloride cotransporter in response to oral potassium intake in mice. Kidney Int 83: 811–824, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van der Lubbe N, Moes AD, Rosenbaek LL, Schoep S, Meima ME, Danser AHJ, et al.: K+-induced natriuresis is preserved during Na+ depletion and accompanied by inhibition of the Na+-Cl- cotransporter. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 305: F1177–F1188, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoorn EJ, Nelson JH, McCormick JA, Ellison DH: The WNK kinase network regulating sodium, potassium, and blood pressure. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 605–614, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xie J, Craig L, Cobb MH, Huang CL: Role of with-no-lysine [K] kinases in the pathogenesis of Gordon’s syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 21: 1231–1236, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Derst C, Karschin C, Wischmeyer E, Hirsch JR, Preisig-Müller R, Rajan S, et al.: Genetic and functional linkage of Kir5.1 and Kir2.1 channel subunits. FEBS Lett 491: 305–311, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.