Short abstract

Objective

This study was performed to investigate the potential of a modified puncture method to decrease the incidence of intravenous indwelling needle-related complications in inpatients with cardiovascular disease.

Methods

From February 2017 to July 2017, 436 consecutive inpatients with cardiovascular disease requiring infusion treatment were recruited and randomly divided into the control group and the treatment group. The standard infusion puncture method was applied in the control group, and a modified puncture method was applied in the treatment group. The incidence of complications and necessary positional adjustments of the intravenous indwelling needle in the two groups were observed.

Results

The incidence of necessary positional adjustments of the intravenous indwelling needle was significantly lower in the treatment group than control group (16.5% versus 5.0%, respectively). The incidences of redness at the puncture point and oozing of blood or fluid at the puncture point were also significantly lower in the treatment group than control group (18.6% versus 4.5% and 12.7% versus 5.5%, respectively).

Conclusions

The modified puncture method for intravenous indwelling needles can significantly decrease the incidence of complications and positional adjustments during application, which relieves patients’ pain and lightens nurses’ workload.

Keywords: Intravenous indwelling needle, puncture method, complications, cardiovascular disease, inpatients, modification

Introduction

An intravenous indwelling needle (i.e., a trocar) is a peripheral intravenous infusion tool that mainly consists of a stainless steel needle core, a hose catheter, and a plastic needle seat. Because of their long indwelling time and avoidance of repeated venipuncture,1 intravenous indwelling needles are widely used in long-term hospitalized patients. Such needles not only alleviate patients’ pain but also improve nurses’ work efficiency.2 According to the intravenous standard, while puncturing, the needle core and hose catheter should be injected together into the blood vessel, and the needle core should then be pulled out while the hose is left in the vessel. The peripheral venous indwelling needle needs to be replaced every 72 to 96 hours to reduce the incidence of phlebitis and bloodstream infection.3 Potential complications include catheter occlusion, fluid leakage, obstruction of venous transfusion, and redness at the puncture point, all of which can adversely affect the effective usage time of the indwelling needle.4 Therefore, the infusion needle may need to be moved to another limb and the nurses must readjust the indwelling needle to a backward position, replace the medical infusion fixation plaster, or even pull out the ineffective needle and perform re-puncture in another position to ensure smooth progression of the intravenous infusion. Not only does this procedure increase patients’ pain and dissatisfaction, but it also increases the burden on nurses and wastes resources. Therefore, we performed the present single-center prospective randomized controlled study to assess whether an improved intravenous indwelling needle puncture method can reduce puncture-related complications and the need to adjust the puncture position.

Methods

Patient selection

Patients with cardiovascular disease requiring intravenous indwelling transfusion in the Department of Cardiology, First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University were recruited from February 2017 to July 2017 and randomly divided into the control group and treatment group. Patients who were unconscious, uncooperative, or had a history of phlebitis were not included. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University (Approval Number: 2015-184). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Methods

In this quasi-randomized study, we grouped the patients according to their bed numbers. Patients with an odd bed number were assigned to the control group, and patients with an even bed number were assigned to the treatment group. The patients in both groups were punctured by trained, qualified nurses who had worked for >2 years after implementation of the Standard Operating Procedure for venous transfusion. The puncture sites were located at the dorsal metacarpal veins. Closed-style 24G indwelling needles were used. After transfusion, the catheter was sealed with normal saline. The indwelling time ranged from 72 to 96 hours.

Control group

After routine disinfection, the dorsal metacarpal veins were punctured by the holding needle at an angle of 15° to 30° above the blood vessel. The angle was then lowered by 5° to 10° after return of blood was confirmed, and the needle continued to be delivered for 2 mm. After the needle core was withdrawn 5 mm, the whole needle catheter was advanced into the blood vessel. The needle core was withdrawn and the catheter was fixed with infusion fixation plaster without tension.

Treatment group

The methods of disinfection and puncture were consistent with those in the control group, but the catheter was incompletely delivered into the blood vessel. Advancement of the needle catheter was stopped 2 mm away from the puncture point, the needle core was withdrawn, and the area was disinfected again with Anerdian II (Shanghai LiKang Disinfectant Hi-Tech Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). The catheter was then fixed with infusion fixation plaster without tension. The difference between the control group and treatment group was that the needle catheter in the treatment group was not completely pushed into the blood vessel; it was left outside the puncture point by 2 mm.

Observation indexes

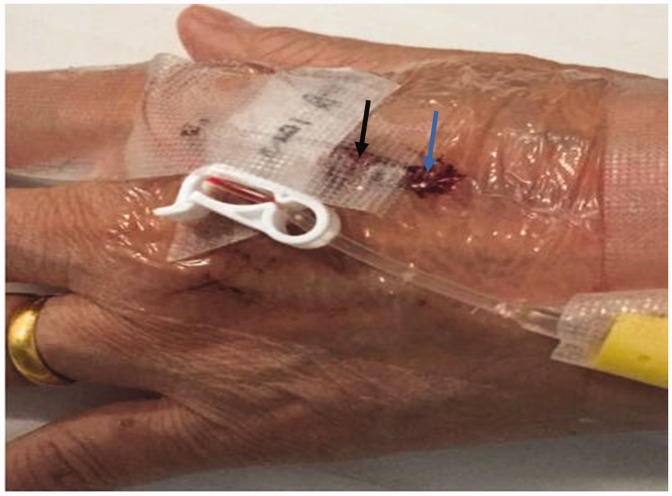

The catheter patency during intravenous fluid infusion was observed in both groups. The patients were also observed for complications and the need for positional adjustments of the indwelling needle. Complications included redness at the puncture site, hematoma, oozing of blood or fluid, and the need to change the indwelling needle position (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Complications of intravenous indwelling needle. The blue arrow indicates bleeding at the puncture point. The black arrow indicates blockage of the transfusion and the need for adjustment of the indwelling position and refixation with medical infusion plaster.

Statistics

SPSS 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for the statistical analysis. Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Categorical data were analyzed by the chi-square test. Probability values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All figures were created by GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

General clinical data

In total, 436 patients were included in this study. The control group comprised 236 patients (113 women, 123 men; average age, 56.54 years; age range, 25–80 years), and the treatment group comprised 200 patients (98 women, 201 men; average age, 54.35 years). There were no significant differences in sex or age between the two groups.

Complications

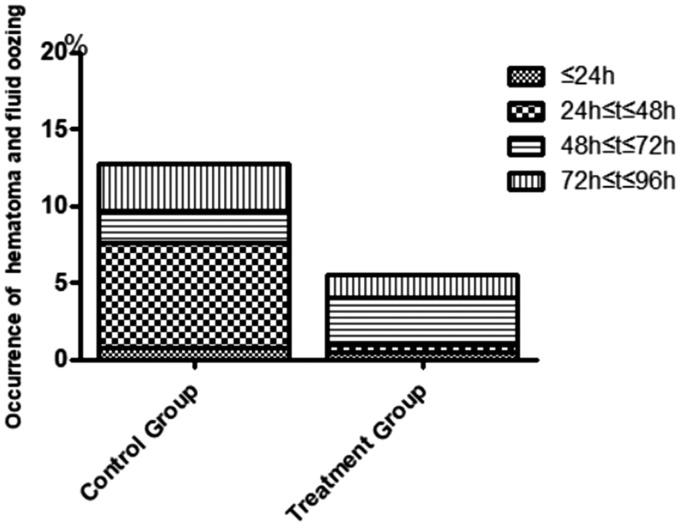

The incidence of complications in the control group was 31.4%. Redness at the puncture point occurred in 44 (18.6%) patients in this group (within 24 hours in 2 patients, from 24 to 48 hours in 16 patients, from 48 to 72 hours in 14 patients, and from 72 to 96 hours in 12 patients) (Figure 2). The incidence of oozing of blood and fluid at the puncture point was 12.7% in the control group (within 24 hours in 0.8%, from 24 to 48 hours in 6.8%, from 48 to 72 hours in 2.1%, and from 72 to 96 hours in 3.0% ) (Figure 3). In contrast, the incidence in the treatment group was significantly lower at 10.0%. In the treatment group, redness at the puncture point occurred in nine (4.5%) patients (from 24 to 48 hours in two patients, from 48 to 72 hours in three patients, and from 72 to 96 hours in four patients). The incidence of oozing of blood and fluid at the puncture point was 5.5% in the treatment group (within 24 hours in 0.5%, from 24 to 48 hours in 0.5%, from 48 to 72 hours in 3.0%, and from 72 to 96 hours in 1.5%). The incidence of complications was significantly different between the two groups (P < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Incidence of redness at the puncture position in the control and treatment groups.

Figure 3.

Incidence of hematoma formation and oozing of fluid in the control and treatment groups.

Positional adjustments of indwelling needle

In the control group, 39 (16.5%) patients underwent positional adjustments of the indwelling needle (within 24 hours in 4 patients, from 24 to 48 hours in 17 patients, from 48 to 72 hours in 11 patients, and from 72 to 96 hours in 7 patients). In the treatment group, 10 (5.0%) patients underwent positional adjustments of the indwelling needle (within 24 hours in 1 patient, from 24 to 48 hours in 1 patient, from 48 to 72 hours in 3 patients, and from 72 to 96 hours in 5 patients). The incidence of positional adjustments of the indwelling needle was significantly lower in the treatment group than control group (P < 0.05) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Incidence of positional adjustment of the indwelling needle in the control and treatment groups.

Discussion

Many complications associated with intravenous indwelling needles occur in clinical nursing practice, such as unsmooth liquid infusion, redness and swelling of the puncture point, and effusion of blood.5 Patients with cardiovascular disease, especially those with coronary heart disease and those undergoing ablation, are usually taking two or more antiplatelet or anticoagulant drugs, which makes them more prone to puncture-related complications.6 These complications not only increase patients’ pain but also reduce patients’ satisfaction with nursing care. Our study showed that the improved intravenous indwelling needle puncture method effectively ensured the smoothness of venous infusion, reduced the occurrence of complications during use of the indwelling needle, alleviated patients’ pain and medical costs, and simultaneously reduced nurses’ workload.

In the present study, we modified the method of indwelling needle puncture by keeping 2 mm of the needle catheter outside the puncture point to avoid formation of an angle between the catheter and needle core, thus ensuring smooth liquid infusion. This improved method can reduce the length of the indwelling needle within the blood vessel, thus leaving some room for the blood vessel to maintain its naturally tortuous and relaxed state and avoiding contact between the catheter tip and vascular wall with resultant friction on the vascular endothelium. We believe that this method can also be used in patients with other diseases, although this needs to be further evaluated in future research.

The process of indwelling needle puncture and site disinfection is standardized according to the established Standard Operating Procedure for venous transfusion. Before infusion is performed in clinical practice, normal return of blood is confirmed after withdrawal of the indwelling needle. However, redness, bleeding, and effusion might occur around the puncture point. Therefore, nurses usually tear down the medical infusion fixation plaster, clear the blood and effusion, withdraw the catheter by about 2 mm, disinfect the site, and apply new medical infusion fixation plaster. In this study, we used the improved indwelling puncture method, which involved incomplete puncture of the needle into the blood vessel and maintenance of about 2 mm of the needle catheter outside the puncture point. This method avoids the formation of an angle between the catheter and the needle core and decreases the repeated friction between the head end of the blood return chamber and the skin at the puncture point, thus alleviating mechanical stimulation at the puncture point and relieving patients’ discomfort. In addition, standardized disinfection was performed again before fixation with the medical infusion plaster. This disinfection procedure prevented possible contamination during puncture, ensured an effective time period of using the indwelling needle, and reduced the occurrence of complications and pain. Stopping advancement of the needle catheter 2 mm away from the puncture point and performing a second disinfection with Anerdian II in the study group were both important. In our opinion, if the first disinfection is standardized, the second disinfection is less important.

In this study, we used normal saline for catheter filling. Catheter filling is a quite important step in the process of intravenous indwelling needle infusion. The currently available catheter filling liquids are heparin and normal saline.7 Heparin, which is a highly effective anticoagulant,8 can inhibit some coagulation factors, interfere with the generation of fibrin, and inhibit platelet adhesion, aggregation, and release. In contrast, normal saline is isotonic to the human body and has no anticoagulant effect. When using heparin for catheter filling, even if blood return is present in the indwelling needle, heparin can combine with antithrombin III in plasma and inactivate thrombin, which plays an anticoagulant role and significantly reduces the probability of blockage. Cook et al.9 concluded that heparin was unnecessary for the maintenance of intravenous access devices because heparin might increase the risk to patient safety. In patients with hepatic insufficiency or heparin allergy, normal saline is recommended for catheter filling. All patients in our study had cardiovascular disease and had been treated with oral anticoagulants or subcutaneous injections of low-molecular-weight heparin. Therefore, normal saline was used to fill the catheters in our study.

In summary, this is the first study to investigate the potential of a modified puncture method to decrease intravenous indwelling needle-related complications in inpatients with cardiovascular disease. Our study has important clinical findings. We adopted an improved intravenous indwelling needle technique that involves maintenance of the needle catheter 2 mm outside the puncture point and a second disinfection with Anerdian II. This method significantly decreases the complications during application, reduces patients’ pain, and lightens nurses’ workload, which is of great significance in clinical nursing work.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Lu Y, Hao C, He W, et al. Experimental research on preventing mechanical phlebitis arising from indwelling needles in intravenous therapy by external application of mirabilite. Exp Ther Med 2018; 15: 276–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson NR. Influencing patient satisfaction scores: prospective one-arm study of a novel intravenous catheter system with retractable coiled-tip guidewire compared with published literature for conventional peripheral intravenous catheters. J Infus Nurs 2016; 39: 201–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ho KH, Cheung DS. Guidelines on timing in replacing peripheral intravenous catheters. J Clin Nurs 2012; 21: 1499–1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.González López JL, Arribi Vilela A, Fernández Del Palacio E, et al. Indwell times, complications and costs of open vs closed safety peripheral intravenous catheters: a randomized study. J Hosp Infect 2014; 86: 117–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bausone-Gazda D, Lefaiver CA, Walters SA. A randomized controlled trial to compare the complications of 2 peripheral intravenous catheter-stabilization systems. J Infus Nurs 2010; 33: 371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller A, Lees RS. Simultaneous therapy with antiplatelet and anticoagulant drugs in symptomatic cardiovascular disease. Stroke 1985; 16: 668–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beigi AA, Hadizadeh MS, Salimi F, et al. Heparin compared with normal saline to maintain patency of permanent double lumen hemodialysis catheters: a randomized controlled trial. Adv Biomed Res 2014; 3: 121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aláezversón CR, Lantero E, Fernàndezbusquets X. Heparin: new life for an old drug. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2017; 12: 1727–1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cook L, Bellini S, Cusson RM. Heparinized saline vs normal saline for maintenance of intravenous access in neonates: an evidence-based practice change. Adv Neonatal Care 2011; 11: 208–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]