Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the impact of trans-vaginal fractional CO2 laser treatment on symptoms of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) in women.

Study design

Women clinically diagnosed with SUI preferring non-surgical treatment were recruited to the study. Fractional CO2 laser system (MonaLisa T, DEKA) treatments were administered trans-vaginally every 4–6 weeks for a total of three treatments. Response to treatment was assessed at baseline (T1), at 3 months after treatment completion (T2) and at 12–24-month follow-up (T3) using the Australian Pelvic Floor Questionnaire (APFQ). The primary outcome was changes in reported symptoms of SUI. Secondary outcomes assessed included bladder function, urgency, urge urinary incontinence (UUI), pad usage, impact of urinary incontinence on quality of life (QOL) and degree of bothersome bladder.

Results

Fifty-eight women were recruited and received the study treatment protocol. Eighty-two percent of participants reported an improvement in symptoms of SUI at completion of treatment (mild to no SUI) (p = <0.01). Treatment effect waned slightly when assessed at follow-up. Nevertheless, 71% of participants reported ongoing improvement in SUI symptoms at 12–24 months (p < 0.01). All secondary outcome measures were improved after treatment compared to baseline.

Conclusions

This study suggests that fractional CO2 laser is a safe, feasible, and beneficial treatment for SUI and may have a role as a minimally-invasive alternative to surgical management.

Keywords: Stress urinary incontinence, Fractional CO2 laser, Bladder function, Urinary leakage, Bladder urgency

Introduction

Urinary incontinence (UI), defined as the complaint of any involuntary leakage of urine, affects nearly 40% of women; stress urinary incontinence (SUI) accounts for approximately half of all UI [1]. UI significantly impacts on quality of life, affecting the woman’s physical, mental, social and sexual well-being and leading to avoidance of intimacy, depression and social isolation [[2], [3], [4]]. In addition, the economic impact of UI was estimated to be $710 million in 1998 and was projected to be $1.6 billion by 2009 in Australia [5].

Surgical options for SUI include trans-vaginal insertion of a mid-urethral sling (MUS) and the more invasive, traditional gold-standard Burch colposuspension procedure, requiring an abdominal approach (laparotomic or laparoscopic). With similar success rates of 74–90% and similar longevity, the choice of one procedure over the other often depends on surgical training, experience, and preference [6]. A systematic review suggests MUS to be a superior surgical treatment, which has rapidly become the procedure of choice for SUI due to shorter operating time and quicker patient recovery; there are nevertheless inherent surgical risks applicable to both procedures, including bleeding, infection, bladder and urethral injury, voiding dysfunction and pain [7].

In 2016, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) reclassified the use of mesh kits in urogynaecology as Class III medical devices requiring pre-market approval [8]. The resultant media attention and class actions against manufacturers of these devices has resulted in the withdrawal of most pelvic organ prolapse (POP) mesh devices from the market [9]. Thus, there is strong public interest in and a clinical need for a minimally-invasive, non-hormonal, effective treatment for SUI.

Fractional micro-ablative laser therapy has been shown to be a potential non-surgical treatment alternative for SUI [10,11]. The subclinical thermal tissue effect from the laser beam induces human dermal fibroblasts to initiate an inflammatory healing cascade, stimulating de novo collagen and elastin synthesis resulting in a thicker vaginal epithelium with larger diameter, glycogen-rich epithelial cells [[12], [13], [14]].

The aim of this study is to evaluate the change in SUI symptoms after trans-vaginal fractional micro-ablative CO2 laser in women at baseline, compared to follow-up at 3 months and 12–24 months post-treatment.

Materials and methods

This is a prospective observational study on women with SUI symptoms who were treated with trans-vaginal fractional CO2 laser. The study received Human Research Ethics approval from Bellberry Limited (Application ID: 2016-04-293). All participants provided informed, written consent; participants were not compensated for their participation.

Study population

During 2014–2017, all women aged 18 years or more being treated by a single gynaecology consultant at FBW Gynaecology Plus were invited to participate in the study. Inclusion criteria were no/unsatisfactory response to conservative treatments and a preference for non-surgical management of bothersome SUI symptoms. The women also demonstrated a positive cough test and urethral hypermobility on ultrasound. All women that participated were offered urodynamic studies and encouraged to continue with topical oestrogen therapy and pelvic floor muscle exercises. Women with ≥stage II pelvic organ prolapse quantification system (POPQ) score, acute or recurrent urinary tract infections, pregnancy, current malignancy, known cervical dysplasia or undiagnosed abnormal uterine bleeding were excluded. All participants were asked to complete the bladder function section of the Australian Pelvic Floor Questionnaire (APFQ) (Appendix A) at baseline (T1), 3 months after third treatment (T2), and at 12–24 months’ follow-up (T3). The APFQ is a validated self-administered pelvic floor questionnaire utilised for quantification of clinical and research outcomes [15]. The primary outcome of this study is to describe the change in self-reported SUI symptoms based on question 6 of APFQ.

The secondary outcomes were bladder function, urgency, urge incontinence, pad usage, quality of life, degree of bothersome bladder score as assessed by APFQ. Improvement of SUI was calculated based on severity scoring 0-3. Bladder function score was calculated by adding all 15 questions in the bladder subsection of APFQ, with maximum score of 45. Scores 0–11.25 was normal bladder function, 11.26–22.5 was mild bladder dysfunction, 22.6–33.75 was moderate bladder dysfunction, and 33.76–45 was severe bladder dysfunction. Questionnaires were distributed to participants and collated by practice staff; the identity of individual respondents remained blinded to the investigators.

Intervention

The intervention was carried out at the FBW Gynaecology Plus office. Participants were pre-treated with topical anaesthetic cream at the level of vestibulum. After 10 min, they were treated with trans-vaginal fractional micro-ablative CO2 laser system (MonaLisa Touch, SmartXide2 V2LR, DEKA, Italy) using the following settings: power 40 W, dwell time 1000 μs, DOT spacing 700 μm, SmartStak parameter 3 and D-pulse mode. The laser beam was emitted from a 90° vaginal probe gently inserted up to the level of the bladder neck, then rotated and withdrawn in order to provide treatment of the anterior lower one third of the vagina and external urethral meatus. Each patient also received three total vaginal length laser treatments with a 360-degree probe as per Salvatore et al. [15]. Three treatments were delivered at intervals of 4 to 6 weeks.

Patients were advised to abstain from vaginal intercourse for 5 days after laser application and avoid heavy lifting (>1 kg) for 6 weeks. Participants with a past history of genital herpes were given antiviral prophylaxis 2 h prior to laser treatment.

Statistical analysis

Power analysis showed that a sample size of 29 participants would be required to achieve 5% significance, 80% power. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used to detect differences for the primary and all secondary outcomes. The threshold for statistical significance was set at 0.05. Data were analysed using IBM SPSS software, version 21.0 (IBM, Chicago, Illinois)

Results

Fifty-eight women were recruited to the study with an average age of 57.4 ± 11.4 years (30–85 years); 45 (77.6%) were postmenopausal, 44 (75.9%) women were on vaginal oestrogen and 33 (56.9%) women underwent urodynamic studies, which confirmed SUI. There were 54 women who were followed-up at 3 months (T2) and 36 at 12–24 months (T3).

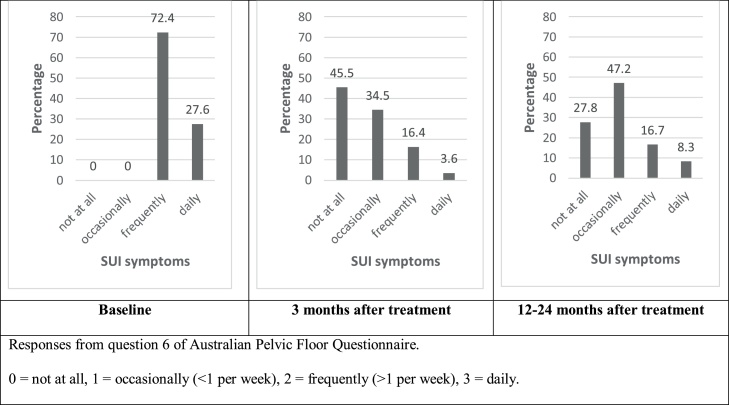

In relation to the primary outcome (question 6 of APFQ), Fig. 1 illustrates the reduction in SUI symptoms reported by women at follow-up (T2 and T3) compared to baseline (T1). At T1, all 58 participants reported frequent or daily SUI symptoms. At T2, 80% (44 of 55) reported an improvement in SUI symptoms, which included 45.5% (25 of 55) participants reporting no SUI symptoms, 16.4% (9 of 55) participants reported frequent symptoms, 3.6% (2 of 55) reported daily symptoms. These changes were also reflected in the median score reduction for Q6 (p < 0.01).

Fig. 1.

Changes in stress incontinence symptoms in women who underwent fractional CO2 laser at pre-treatment (T1; n = 58), 3 months post-treatment (T2; n = 55), and 12–24-month post-treatment (T3; n = 36).

At T2 (3 months); 27 of the 36 women (75%) that returned reported SUI symptoms ‘not more than occasionally,’ including 10 of the 36 (27.8%) (T3) who reported no symptoms. These women also had a negative cough test at the time of clinical examination. The remaining 9 of the 36 (25%) women experienced a return of occasional SUI symptoms.

Similar results were demonstrated for secondary outcomes of bladder function (APFQ questions 1–15), urge incontinence (APFQ question 5) and bothersome bladder (APFQ question 15). Normal bladder function increased from 31% (18 of 58) at T1 to 72.2% (39 of 54) at T2. This trend decreased to 69.4% (25 of 36) at T3. There was an overall improvement in participants’ urge incontinence scores from T1 to T2, with an increase in the number of patients reporting “never” leaking urine when they rush to the toilet from T1 to T2 (19% to 60%, p < 0.01); this trend decreased slightly to at T3 (44.4%, p < 0.01). There was an improvement in the participants’ degree of bothersome bladder from T1 to T2; more women reported “not at all (bothersome)” from T1 to T2 (3.4% to 50%, p < 0.01); this trend reduced at T3 (36%, p = 0.01). The results are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Outcomes for women who underwent fractional CO2 laser at pre-treatment (T1) compared to 3 months after treatment (T2) and 12–24 months after treatment (T3).

| APFQ | Improvement % (n) | Median T1 | Median T2 | p-value | Improvement % (n) | Median T1 | Median T3 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | |||||||||

| Stress incontinence | 6 | 80 (55) | 2 | 1 | <0.01 | 75 (36) | 2 | 1 | <0.01 |

| Secondary outcomes | |||||||||

| Bladder Function | 1-15 | 67 (54) | 1 | 0 | <0.01 | 87.5 (36) | 1 | 0 | <0.01 |

| Urge incontinence | 5 | 79 (55) | 2 | 0 | <0.01 | 63 (36) | 2 | 1 | <0.01 |

| Urgency | 4 | 65 (55) | 2 | 1 | <0.01 | 45 (36) | 2 | 1 | <0.01 |

| Wearing pads | 10 | 54 (55) | 2 | 0 | 0.01 | 46 (36) | 2 | 0 | 0.01 |

| Impact of urinary leakage on QOL | 14 | 63 (55) | 1 | 0 | <0.01 | 44 (36) | 1 | 0 | 0.01 |

| Degree of bothersome bladder | 15 | 56 (54) | 2 | 1 | <0.01 | 45 (36) | 2 | 1 | <0.01 |

APFQ = Australian Pelvic Floor Questionnaire.

STD = Standard deviation.

p < 0.05 as statistically significant.

Differences were assessed by Wilcoxon sign-rank testing.

Women lost to follow-up were contacted to offer review. Upon phoning 22 of the 58 patients to arrange the 12-month follow-up, 5 participants reported no further SUI symptoms (cured) and 3 participants reported 50–60% improvement of their SUI symptoms which they deemed manageable. There were another 14 women who did not improve after 3 sessions of CO2 laser treatment, 4 of whom opted for MUS surgery and some women desired to avoid surgery by undergoing autologous cell therapy, such as platelet-rich plasma (RegenPRP®).

There were no serious adverse events as a result of the treatment protocol. Out of 58 participants, 3 (5.4%) participants noticed a change in vaginal discharge diagnosed as thrush, which resolved with treatment; 2 (3.4%) participants reported symptoms of urinary tract infections (both of these patients had previous history of post-coital UTIs) and were treated with appropriate antibiotics; 1 (1.7%) participant developed a recurrence of genital herpes and required antiviral therapy.

Comments

This study describes the change in prevalence of SUI symptoms before and after fractionated CO2 laser to treat both pre- and post-menopausal women with SUI. The study showed that following 3 treatments at 4–6-week intervals, SUI symptoms improved in 80% of participants at 3 months (p < 0.01) and that these benefits persisted in 75% of participants at 12 months (p < 0.01).

SUI is a significant condition affecting women with their physical, mental and social well-being [1,2]. Women who seek non-surgical treatment are presented with a limited range of low-risk treatment options, such as pelvic floor muscle strengthening and vaginal pessaries [17]. For women who are sexually active, vaginal pessaries can pose coital problems. In addition, pessaries can be problematic for women with severe vaginal atrophy and mobility issues, as the need for regular examinations can be traumatising, painful and requiring concomitant topical oestrogen therapy.

Topical oestrogen therapy has been shown to provide modest treatment benefits for women experiencing UI, mostly improving urinary urgency and frequency related symptoms [18]. Recent literature suggests that topical oestrogen does not increase incidence of oestrogen-dependent malignancies, cardiovascular or thromboembolic complications [19]. However, women with a personal history of these conditions, especially breast cancer, are often advised to avoid any hormonal treatment and many others still decline, leaving them with few alternatives for management of their SUI. Furthermore, topical oestrogen benefits only last while the product is being applied, which requires patient compliance.

Since the 1990s, surgical management of SUI has shifted from the more invasive traditional Burch colposuspension to increasing use of the MUS, due to shorter operating time and fewer complications (except for bladder injury) with improved outcomes [7]. Furthermore, recent FDA statements, TGA withdrawal of mesh products, class actions, and media focus on mesh in urogynaecological procedures has seen a strong public reaction against mesh. There is a 2.4–9.8% risk of mesh erosion after MUS insertion with higher erosion rates after use of transvaginal mesh in POP surgery [[20], [21], [22], [23]].

Trans-vaginal fractionated CO2 laser treatment has been shown to improve vaginal tissue health in women with vaginal atrophy [12]. Since 2014, a growing number of studies have been published exploring the use of trans-vaginal laser treatment for gynaecogical conditions such as SUI, mixed UI (MUI) and genitourinary symptoms of menopause (GSM) [16,25]. Salvatore et al. first published a pilot study of 50 women with GSM who were dissatisfied with topical oestrogen therapy. Following three treatments with fractional CO2 laser, the outcomes were assessed with the Vaginal Health Index Score (VHIS) and Short Form-12 Quality of Life (SF-12 QOL) survey. They found significant improvements in the symptoms and impact of GSM on QOL by all measures assessed at 12 weeks [15]. Behnia-Willison et al. showed in a study treating 102 women with GSM with fractional CO2 laser having improvements up to 24 months by colposcopic examinations and responses to APFQ [24].

Regarding use of laser for UI, Ogrinc et al. recruited 175 women with symptoms of SUI or MUI. Their treatment protocol included an erbium-doped yttrium-aluminium-garnet (Er:YAG) laser to deliver both non-ablative full circumferential vaginal and fractionated anterior vaginal wall treatment; this significantly improved symptoms in 77% of women with SUI and 34% of women with MUI [26]. Two other prospective cohort studies using Er:YAG laser to treat SUI showed similar positive results [26,27].

This study builds on data from other prospective cohort studies showing that Er:YAG vaginal laser treatment was able to significantly improve symptoms of SUI short-term (up to 12 months) as assessed by the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire (ICIQ) and the Incontinence Severity Index (ISI) [27]. Similarly, Isaza et al. demonstrated long-term benefits up to 36 months after CO2 laser for women with mild SUI and GSM [28]. Hence, the treatment poses minimal risks and this study also adds to data demonstrating a good safety profile with trans-vaginal use.

The purpose of this study was to include women who were still symptomatic after first line conservative treatment, including pelvic floor exercises and vaginal oestrogen therapy, and desired to have an alternative non-surgical therapy. Whilst a blinded RCT would be ideal, data from this observational study suggests that fractionated CO2 laser treatment of the vagina results was able to produce comparable outcomes to MUS procedures, with ongoing improvement of SUI symptoms at 12–24 months. It is most likely that maintenance CO2 laser therapy is required. Due to individual ageing pattern and menopause effect and uncertain treatment intervals after T3, further studies are required.

Limitations of the study include the study design and attrition rate. We experienced a high attrition rate for responses from T1 (n = 58) to T3 (n = 36), which introduces a possibility of attrition bias and can weaken the strengths of our findings. At T2, all patients attended follow-up but 3 patients did not complete the data. At T3, there was 62% of women who attended follow-up. Another limitation was our primary outcome being based on a subjective measure reported by the participants and objective cough test and bladder neck funnelling by the treating specialist; only 33 participants agreed to undergo urodynamic studies. The remaining participants declined this test due to invasiveness and social circumstances, such as cost and insurance cover. There were 4 participants who underwent urodynamics and surgical management which had resolved their SUI symptoms. Another limitation is that this is an uncontrolled study and subjected to the usual biases. In addition there are well known placebo effects with the use of new medical devices. However, the strength of this study is the potential to develop a another non-surgical treatment option for symptomatic SUI. The first line treatment includes oestrogen cream for vaginal atrophy, pelvic floor muscle training, and lifestyle optimisation. The second line treatment includes CO2 laser treatment +/- platelet-rich plasma (PRP). Then third line treatment would be surgery.

In summary, micro-ablative fractional CO2 laser treatment appears to be a promising, non-surgical, non-hormonal, minimally invasive, durable, low risk treatment option for women with SUI. The safety this treatment modality and the reduced prevalence as per self-reported SUI symptom reduction from baseline suggests a possible alternative for women with SUI who are unwilling to accept the inherent risks of MUS and Burch colposuspension, or whose medical comorbidities exclude surgical treatment. Further research should compare the use of fractionated CO2 laser with placebo and/or established treatments, as well as determine whether booster treatment is required to sustain improvements in SUI symptoms longer term.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflict of interest. FBW is a preceptor for MonaLisa Touch and runs laser workshops for the company. FBW is paid to run these teaching workshops but received no support, financial or otherwise, to run this study.

Funding

There were no sources of funding for this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge the staff of FBW Gynaecology Plus in assisting with the running and follow-up of participants of the study. We wish to thank Aidan Norbury for his contribution to the paper.

Appendix A. Australian Pelvic Floor Questionnaire – Bladder Function Items

| Questionnaire item | Response options | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APFQ1. How many times do you pass urine in the day? | (0) Up to 7 | (1) Between 8-10 | (2) Between 11-15 | (3) More than 15 |

| APFQ2. How many times do you get up at night to pass urine? | (0) 0–1 | (1) 2 times | (2) 3 times | (3) More than 3 times |

| APFQ3. Do you wet the bed before you wake up at night? | (0) Never | (1) Occasionally–less than once per week | (2) Frequently–once or more than per week | (3) Always–every night |

| APFQ4. Do you need to rush or hurry to pass urine when you get the urge? | (0) Never | (1) Occasionally | (2) Frequently | (3) Daily |

| APFQ5. Does urine leak when you rush or hurry to the toilet? i.e. You can’t make it in time? | (0) Never | (1) Occasionally– less than once per week | (2) Frequently–more than once per week | (3) Daily |

| APFQ6. Do you leak urine with coughing, sneezing, laughing or exercising? | (0) Not at all | (1) Occasionally | (2) Frequently | (3) Daily |

| APFQ7. Is your urinary stream (urine flow) weak, prolonged or slow? | (0) Never | (1) Occasionally– less than once per week | (2) Frequently–more than once per week | (3) Daily |

| APFQ8. Do you have a feeling of incomplete bladder emptying? | (0) Never | (1) Occasionally– less than once per week | (2) Frequently–more than once per week | (3) Daily |

| APFQ9. Do you need to strain to empty your bladder? | (0) Never | (1) Occasionally– less than once per week | (2) Frequently–more than once per week | (3) Daily |

| APFQ10. Do you wear pads because of urinary leakage? | (0) None-never | (1) As a precaution | (2) When exercising/during a cold | (3) Always |

| APFQ11. Do you limit your fluid intake to decrease leakage? | (0) Never | (1) Before going out/socially | (2) Moderately | (3) Daily |

| APFQ12. Do you have frequent bladder infections? | (0) No | (1) 1–3 per year | (2) 4–12 per year | (3) More than once per month |

| APFQ13. Do you have pain in your bladder or urethra when you empty your bladder? | (0) Never | (1) Occasionally– less than once per week | (2) Frequently–more than once per week | (3) Daily |

| APFQ14. Does the urine leakage affect your routine activities like recreation, socialising, sleeping, shopping, etc.? | (0) Not at all | (1) Slightly | (2) Moderately | (3) Greatly |

| APFQ15. How much does the bladder problem bother you | (0) Not at all | (1) Slightly | (2) Moderately | (3) Greatly |

References

- 1.Lukacz E.S., Santiago-Lastra Y., Albo M.E., Brubaker L. Urinary incontinence in women: a review. JAMA. 2017;318(16):1592–1604. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.12137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minassian V.A., Yan X., Lichtenfeld M.J., Sun H., Stewart W.F. The iceberg of health care utilization in women with urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23(8):1087–1093. doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-1743-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duralde E.R., Rowen T.S. Urinary incontinence and associated female sexual dysfunction. Sex Med Rev. 2017;5(4):470–485. doi: 10.1016/j.sxmr.2017.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Almousa S., Bandin van Loon A. The prevalence of urinary incontinence in nulliparous adolescent and middle-aged women and the associated risk factors: a systematic review. Maturitas. 2018;107:78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . 2013. Incontinence in Australia. Canberra. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riemsma R., Hagen S., Kirschner-Hermanns R., Norton C., Wijk H., Andersson K.E. Can incontinence be cured? A systematic review of cure rates. BMC Med. 2017;15(1):63. doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-0828-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fusco F., Abdel-Fattah M., Chapple C.R., Creta M., La Falce S., Waltregny D. Updated systematic review and meta-analysis of the comparative data on colposuspensions, pubovaginal slings, and midurethral tapes in the surgical treatment of female stress urinary incontinence. Eur Urol. 2017;72(4):567–591. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Food and Drug Administration . 2017. Urogynecologic surgical mesh implants. September. [Google Scholar]

- 9.McAchran S.E., Goldman H.B. Synthetic midurethral slings redeemed. Lancet. 2017;389(February (10069)):580–581. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32597-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keane D.P., Sims T.J., Abrams P., Bailey A.J. Analysis of collagen status in premenopausal nulliparous women with genuine stress incontinence. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104(9):994–998. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1997.tb12055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rechberger T., Postawski K., Jakowicki J.A., Gunja-Smith Z., Woessner J.F., Jr. Role of fascial collagen in stress urinary incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179(1):1511–1514. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zerbinati N., Serati M., Origoni M., Candiani M., Iannitti T., Salvatore S. Microscopic and ultrastructural modifications of postmenopausal atrophic vaginal mucosa after fractional carbon dioxide laser treatment. Lasers Med Sci. 2015;30(1):429–436. doi: 10.1007/s10103-014-1677-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moalli P.A., Shand S.H., Zyczynski H.M., Gordy S.C., Meyn L.A. Remodeling of vaginal connective tissue in patients with prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(5):953–963. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000182584.15087.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salvatore S., Leone Roberti Maggiore U., Athanasiou S., Origoni M., Candiani M., Calligaro A. Histological study on the effects of microablative fractional CO2 laser on atrophic vaginal tissue: an ex vivo study. Menopause. 2015;22(8):845–849. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baessler K., O’Neill S.M., Maher C.F., Battistutta D. A validated self-administered female pelvic floor questionnaire. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(February (2)):163–172. doi: 10.1007/s00192-009-0997-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salvatore S., Nappi R.E., Zerbinati N., Calligaro A., Ferrero S., Origoni M. A 12-week treatment with fractional CO2 laser for vulvovaginal atrophy: a pilot study. Climacteric. 2014;17(4):363–369. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2014.899347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lipp A., Shaw C., Glavind K. Mechanical devices for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(12):CD001756. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001756.pub6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weber M.A., Kleijn M.H., Langendam M., Limpens J., Heineman M.J., Roovers J.P. Local oestrogen for pelvic floor disorders: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0136265. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crandall C.J., Hovey K.M., Andrews C.A., Chlebowski R.T., Stefanick M.L., Lane D.S. Breast cancer, endometrial cancer, and cardiovascular events in participants who used vaginal estrogen in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Menopause. 2018;25(January (1)):11–20. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keltie K., Elneil S., Monga A., Patrick H., Powell J., Campbell B. Complications following vaginal mesh procedures for stress urinary incontinence: an 8 year study of 92,246 women. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):12015. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11821-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ford A.A., Rogerson L., Cody J.D., Aluko P., Ogah J.A. Mid-urethral sling operations for stress urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;7:CD006375. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006375.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schimpf M.O., Abed H., Sanses T., White A.B., Lowenstein L., Ward R.M. Graft and mesh use in transvaginal prolapse repair: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(1):81–91. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang L., Zhu L., Chen J., Xu T., Lang J.H. Tension-free polypropylene mesh-related surgical repair for pelvic organ prolapse has a good anatomic success rate but a high risk of complications. Chin Med J (Engl) 2015;128(3):295–300. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.150088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Behnia-Willison F., Sarraf S., Miller J., Mohamadi B., Care A.S., Lam A. Safety and long-term efficacy of fractional CO2 laser treatment in women suffering from genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;213:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2017.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogrinc U.B., Sencar S., Lenasi H. Novel minimally invasive laser treatment of urinary incontinence in women. Lasers Surg Med. 2015;47(9):689–697. doi: 10.1002/lsm.22416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fistonic N., Fistonic I., Gustek S.F., Turina I.S., Marton I., Vizintin Z. Minimally invasive, non-ablative Er:YAG laser treatment of stress urinary incontinence in women-a pilot study. Lasers Med Sci. 2016;31(4):635–643. doi: 10.1007/s10103-016-1884-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pardo J.I., Sola V.R., Morales A.A. Treatment of female stress urinary incontinence with Erbium-YAG laser in non-ablative mode. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;204:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Isaza P., Jaguszewska K., Cardona J. Long-term effect of thermoablative fractional CO2 laser treatment as a novel approach to urinary incontinence management in women with genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:211–215. doi: 10.1007/s00192-017-3352-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]