Abstract

Purpose of review

This review focuses on the role of intracellular chloride in regulating transepithelial ion transport in the distal convoluted tubule (DCT) in response to perturbations in plasma homeostasis.

Recent findings

Low dietary potassium increases the phosphorylation and activity of the sodium chloride cotransporter (NCC) in the DCT, and vice versa, affecting sodium-dependent potassium secretion in the downstream aldosterone-sensitive distal nephron. In cells, NCC phosphorylation is increased by lowering of intracellular chloride, via activation of the chloride-sensitive WNK (With No Lysine)-SPAK/OSR1 (Ste20-related proline/alanine rich kinase/oxidative stress response) kinase cascade. In vivo studies have demonstrated pathway activation in the kidney in response to low dietary potassium. A possible mechanism is lowering of DCT intracellular chloride in response to low potassium due to parallel basolateral potassium and chloride channels. Recent studies support a role for these channels in the response of NCC to varying potassium. Studies examining chloride-insensitive WNK mutants, in the Drosophila renal tubule and in the mouse, lend further support to a role for chloride in regulating WNK activity and transepithelial ion transport. Caveats, alternatives and future directions are also discussed.

Summary

Chloride sensing by WNK kinase provides a mechanism to allow coupling of extracellular potassium with NCC phosphorylation and activity to maintain potassium homeostasis.

Keywords: hypokalemia, hyperkalemia, ion transport, hypertension

Introduction

The kidney plays an essential role in maintaining homeostasis of serum electrolytes. Potassium concentration, for example, is maintained between 3.5 – 5 mmol/L, and even small deviations from normal (including within the laboratory-defined “normal range”) are associated with morbidity and mortality [1–6, 7*,8*,9*,10*,11,12]. Furthermore, a potassium-deficient diet is associated with higher blood pressures and hypertension [13,14], and there is an inverse association between potassium intake and death [15], indicating the importance of homeostatic mechanisms that maintain normal serum potassium concentrations. The kidney excretes ~90% of daily ingested potassium [16], and therefore is central to potassium homeostasis. This article will review the role of intracellular chloride in regulating transepithelial ion transport in the distal convoluted tubule (DCT) to achieve potassium homeostasis.

Dietary potassium modulates phosphorylation of the sodium chloride cotransporter

A major mechanism for potassium secretion by the aldosterone-sensitive distal nephron (ASDN) is the exchange of sodium ions for potassium. Therefore, increasing distal delivery of sodium facilitates renal potassium secretion [16], and it has long been appreciated that potassium has natriuretic (and blood pressure-lowering) effects [17–19]. Potassium loading decreases sodium reabsorption by the proximal tubule [20,21*] and thick ascending limb [22–26]. The DCT is also upstream of the ASDN and therefore positioned to influence ASDN sodium delivery. Genetic mutations influencing DCT sodium reabsorption result in hypokalemia [27,28] or hyperkalemia [29], suggesting an important role for DCT transport in the regulation of serum potassium concentrations.

The sodium chloride-reabsorbing transporter on the apical membrane of DCT epithelial cells is the sodium chloride cotransporter (NCC) [30,31]. NCC phosphorylation increases its activity [32,33]. In rodents, acute potassium administration, via oral or intravenous routes [34,35*,36–38], results in rapid dephosphorylation of NCC, as does acute elevation in plasma potassium due to amiloride administration [39**]. Feeding rodents high potassium diet over several days results in decreased total, phosphorylated and surface NCC abundance [40–42,43*,44], while low potassium diet results in increased total and phosphorylated NCC [45–48]. Importantly, the effects of low potassium on NCC upregulation persist in mice and humans concomitantly fed high sodium, ie, the typical “Western” diet [49,50]. These data indicate that low potassium states result in NCC activation, and vice versa. Indeed, there is an inverse linear association between plasma potassium concentration and phosphorylated NCC levels in mice [51], and a similar association is observed in DCT cells in kidney slices bathed in varying potassium baths for 30 minutes [36], suggesting a direct effect of potassium on DCT epithelial cells.

Chloride regulates SLC12 cotransporters

NCC is an SLC12 cation-coupled chloride cotransporter that is closely related to the sodium-potassium-2-chloride cotransporters (NKCCs) [52]. John Russell and colleagues, working with the internally dialyzed squid giant axon preparation, showed that NKCC was activated by lowering of intracellular chloride concentrations [53–55]. This relationship was also demonstrated in salivary gland acinar cells [56] and in a transporting epithelium, the shark rectal gland, and was associated with increased transporter phosphorylation [57]. In cultured cells and Xenopus oocytes, maneuvers resulting in lowering of intracellular chloride, such as hypotonic low chloride bathing medium or expression of chloride-excreting transporters, stimulate the phosphorylation and activity of NCC, NKCC1 and NKCC2 [32,33,58,59].

Role of basolateral potassium and chloride channels in the DCT

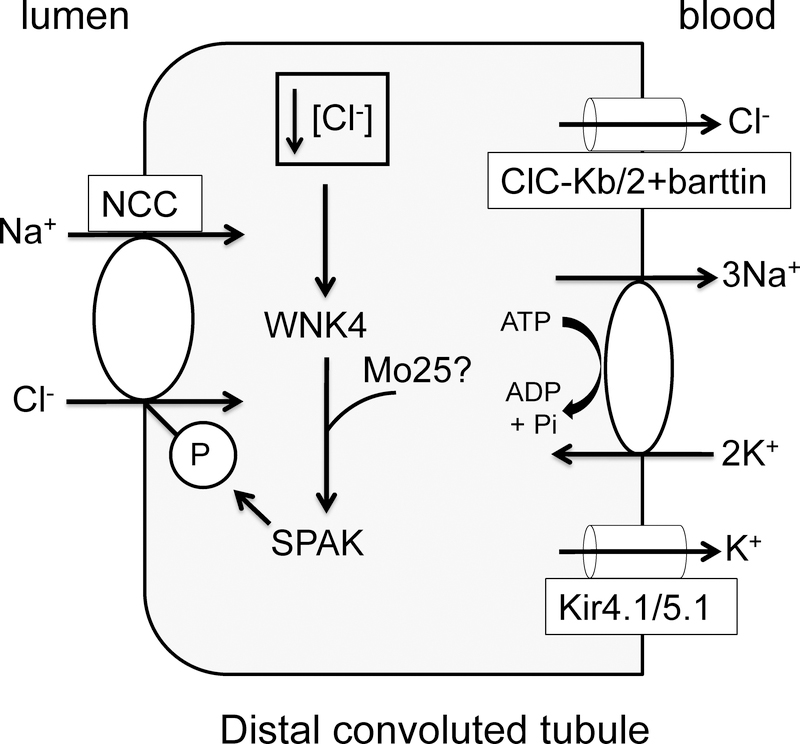

In a secretory epithelium like the shark rectal gland, hormonal stimulation of apical chloride exit lowers intracellular chloride, providing a mechanism for increasing basolateral NKCC1 phosphorylation and activation [60]. On the DCT basolateral membrane, potassium entering through the sodium/potassium-ATPase is recycled through a potassium channel consisting of a heterotetramer of Kir4.1, encoded by KCNJ10, and Kir5.1, encoded by KCNJ16 [61–63]. In parallel, Clc-Kb/2 channels, together with the β-subunit barttin, allow chloride exit across the basolateral membrane [64,65] (Figure 1). This provides a potential mechanism to link changes in extracellular potassium to changes in intracellular chloride. A decrease in plasma extracellular potassium will increase the driving force for potassium exit across the basolateral membrane, hyperpolarizing the membrane potential, and increasing the driving force for basolateral chloride exit. This could lower intracellular chloride, increasing NCC phosphorylation and activity.

Figure 1.

Changes in plasma potassium regulate NCC phosphorylation and activity through chloride regulation of WNK pathway activity. A model of the DCT epithelial cell is shown, including apical NCC and the chloride/WNK4/SPAK kinase pathway regulating it. Mo25 may also play a cooperative role in pathway activation, although this has not been demonstrated in the DCT thus far. Sodium/potassium-ATPase, the heteromeric Kir4.1/Kir5.1 potassium channel, and Clc-Kb/2 chloride channel (with barttin) are on the basolateral membrane, and provide a mechanism to lower intracellular chloride concentration and increase WNK4/SPAK activity and NCC phosphorylation and activity when plasma potassium concentration is low. See text for further details.

A number of observations support the model that the activity of Kir4.1/5.1 and Clc-Kb/2 (with barttin) influences NCC phosphorylation and activity and serum potassium concentrations. Human mutations in KCNJ10, CLCKB or BSND (encoding barttin) result in hypokalemia [66–69]. In mice, low potassium diet increases the activity of Kir4.1/5.1 channels on the basolateral membrane of DCT, resulting in hyperpolarization of the DCT basolateral membrane and increased total and phosphorylated NCC expression and activity. High potassium diet has the opposite effects, and low and high potassium diet effects were abolished in mice with nephron knockout or knockdown of Kir4.1 [70**,71**,72*]. Loss of Kir4.1 also results in loss of NPPB (5-Nitro-2-(3-phenylpropylamino)benzoic acid)-sensitive chloride currents [71**,73], and the changes in potassium current in response to low and high potassium diets are paralleled by changes in chloride currents [70**], suggesting coupling between the basolateral potassium and chloride conductances. Mice carrying a hypomorphic mutation in Bsnd are hypokalemic, and, unlike wild-type mice, there was no increase in total or phosphorylated NCC in response to low potassium diet in the mutant mice, supporting a role for basolateral chloride efflux in this process [74*]. The Bsnd mutant mice were also protected from the hypertensive effect of a high sodium/low potassium diet [74*].

WNK kinases as chloride sensors

The increased phosphorylation of NCC observed in low potassium conditions implies activation of a kinase cascade. NCC, together with NKCC1 and NKCC2, is regulated by phosphorylation of conserved N-terminal serines and threonines by the WNK (With No Lysine)-SPAK/OSR1 (Ste20-related proline/alanine rich kinase/oxidative stress response) kinase cascade [33,75–79]. SPAK and OSR1 are paralogous Ste20 kinases that are phosphorylated and activated by all WNK isoforms, although WNK4 and SPAK dominate in the DCT [29]. Bathing cultured cells in hypotonic low chloride medium results in activation of WNK1 and SPAK/OSR1, NCC phosphorylation, and increased NCC transport activity [33,80].

Chloride regulates WNK-SPAK/OSR1 phosphorylation of NCC

Chloride binds directly to the WNK1 kinase active site, as observed by X-ray crystallography, and inhibits the autophosphorylation required for WNK activation [81]. Mutating the chloride-binding Leu 369 in WNK1 decreases the inhibitory effect of chloride on WNK1 autophosphorylation in vitro [81], and introducing this mutation into WNK1, or the homologous mutation into WNK4, in HEK293 cells or Xenopus oocytes resulted in increased NCC phosphorylation and transport activity [51,82]. This implies that a decrease in intracellular chloride relieves inhibition of WNKs to allow SPAK/OSR1 activation and NCC phosphorylation and activation. Interestingly, SPAK autophosphorylation is also inhibited by increased chloride concentration in vitro [83]; whether the mechanism is similar to WNKs has not been determined.

As a chloride-sensitive signaling cassette, the WNK-SPAK/OSR1 kinase cascade could mediate changes in NCC phosphorylation and activity in response to altered potassium and consequent changes in DCT intracellular chloride, as first proposed by Terker et al. (Figure 1) [49]. In COS7 cells, there was an inverse association between bathing medium potassium concentration and OSR1 phosphorylation [84], mirroring the relationship between serum potassium and NCC phosphorylation in mice [51]. Bathing HEK293 cells in low potassium medium, which decreased intracellular chloride, also increased SPAK/OSR1 and NCC phosphorylation in a WNK1 and WNK3-dependent manner. Potassium channel inhibition with barium, or expression of mutant Kir4.1 or CLC-K2, blocked the effect, while expression of chloride-insensitive WNK1 mimicked the effect of low potassium and conferred insensitivity to changes in bath potassium [49]. In an ex vivo kidney slice preparation, 30 minutes of low potassium bath increased phosphorylated SPAK/OSR1 in physiological chloride concentrations (110 mM) but not in low chloride (5 mM) conditions [36].

Effects of low and high potassium diets on WNK signaling

Studies have demonstrated increased SPAK [47,49,50], apical localization of OSR1 in the DCT [47], or increased SPAK/OSR1 phosphorylation [46,47] in mice fed low potassium diets. WNK4 was also increased in mice fed a low potassium diet [49], and there was no increase in total NCC in response to low potassium diet in WNK4 knockout mice [46]. A recent study corroborated this finding, demonstrating that there was no increase in either total or phosphorylated NCC in response to low potassium diet in WNK4 knockout mice, nor an increase in NCC activity (as measured by thiazide-induced natriuresis), despite preserved ability to increase NCC phosphorylation and activity in response to increased sodium delivery to the DCT via furosemide administration. This indicates a specific role for WNK4 in regulating NCC in response to low dietary potassium [85**]. Similarly, mice in which SPAK was knocked out together with nephron-specific OSR1 knockout had either blunted [49] or absent [86] increase in total or phosphorylated NCC in response to low potassium diet.

A recent study in the Drosophila renal tubule measured acute changes in intracellular chloride and WNK activity in transporting tubules. In this epithelium, WNK-SPAK/OSR1 signaling regulates transport through a basolateral NKCC [87,88*]. Hypotonic bathing medium (in which both potassium and chloride concentrations are lowered) stimulates transport in a WNK-SPAK/OSR1-NKCC-dependent manner [87]. Under these conditions, intracellular chloride, measured using a transgenic sensor, decreased, with a nadir at 30–60 minutes, and WNK activity increased during the same timeframe [88*], supporting the hypothesis that acute changes in intracellular chloride can influence WNK activity, and, importantly, transepithelial ion transport [87]. Like the DCT, the basolateral membrane of the Drosophila renal epithelium has both potassium and chloride conductances [89], and manipulation of bath potassium, without changes in tonicity or extracellular chloride, was sufficient to result in changes in WNK activity, with low potassium bath stimulating WNK activity and vice versa [88*]. Furthermore, expression of chloride-insensitive WNK, together with the scaffold protein Mo25 (Mouse protein 25)/Cab39 (calcium-binding protein 39), was sufficient to increase transepithelial ion transport in standard bathing conditions, indicating a role for chloride regulation of WNK in a transporting renal epithelium [88*].

A recent paper similarly examined the effect of chloride-insensitive WNK4 on potassium homeostasis in the mouse. WNK4 is the dominant WNK paralog regulating NCC in the DCT [90,91], and is the most sensitive to chloride in vitro and in cellular studies [51,82]. Chen et al. generated chloride-insensitive WNK4 knockin mice, which were hyperkalemic, with decreased fractional excretion of potassium, and hypertensive. The mice had increased phosphorylated SPAK/OSR1 and total and phosphorylated NCC expression and activity, which did not increase further with low potassium diet (Chen JC, Lo YF, Lin YW, Lin SH, Huang CL, Cheng CJ, unpublished data). These findings support the model that the effects of low potassium diet on NCC phosphorylation and activity are mediated by chloride regulation of WNK4 activity.

Whether the effects of acute or chronic potassium administration on NCC dephosphorylation are mediated by the WNK-SPAK/OSR1 pathway is controversial. In the Drosophila renal epithelium, high potassium bath decreased tubule WNK activity acutely, although whether this is mediated by chloride is unknown. In rodent tissue, NCC dephosphorylation has been observed in the absence of changes in SPAK/OSR1 phosphorylation, in the presence of low or high extracellular chloride, and in the presence of chloride channel blockers [34,36,92*]. In the chloride-insensitive WNK4 mice, there was blunted natriuresis in the first 6 hours of a high-potassium diet, but total and phosphorylated NCC expression, and thiazide-sensitive sodium excretion, were suppressed in both wild-type and mutant mice, suggesting that the effect of high potassium diet on NCC is independent of WNK4 chloride sensing (Chen et al., unpublished data). Activation of phosphatases could explain this effect [92*,93,94]. On the other hand, rapid NCC dephosphorylation after potassium loading by gavage failed to occur in the chloride-insensitive WNK4 mutant mice, with a greater rise in plasma potassium after gavage (Chen et al., unpublished data). Further research is required to clarify the roles of chloride-regulated WNK signaling, phosphatases, and other mechanisms in potassium-induced NCC dephosphorylation.

Caveats and alternatives

Modeling studies have suggested that changes in proximal tubule and/or thick ascending limb sodium reabsorption may be quantitatively more important than changes in DCT sodium reabsorption in influencing ASDN potassium secretion [21*,43*]. Furthermore, although initial modeling studies supported the idea that changes in NCC phosphorylation could be driven by changes in intracellular chloride [49], a more recent study challenged this concept, with the caveat that changes in intracellular chloride were predicted rather than measured [39**]. Thus, measurement of intracellular chloride in the DCT with varying perturbations in systemic potassium would be useful, but are difficult to perform in vivo; ex vivo measurements could be complicated if tubules are analyzed in conditions in which they are no longer transporting, due to altered driving forces for chloride movement across apical and basolateral membranes.

Distal tubule remodeling also influences sodium reabsorption and potassium secretion. Maneuvers which increase sodium delivery to the DCT or connecting tubule (CNT) result in parallel changes in ultrastructure and transport capacity [95–97], while DCT atrophy occurs in mice lacking NCC, SPAK or Kir4.1 [98,99,100**,101]. In mice expressing constitutively active SPAK in the early DCT (DCT1) [102**], which results in increased NCC expression and activity, DCT1 undergoes hypertrophy, while the CNT, quantitatively the most important segment for potassium secretion [103,104], atrophies [102**]. The effects of hydrochlorothiazide on tubule morphology and the timecourse of natriuresis and kaliuresis suggested that these structural changes explain renal potassium retention and hyperkalemia [102**]. Three days of low potassium diet itself is sufficient to induce hyperplasia in multiple nephron segments, including DCT1 [100**]. In light of these results, it would be interesting to determine whether there are morphological changes in WNK4 knockout or chloride-insensitive WNK4 knockin mice that could explain altered potassium homeostasis in these animals, rather than the inability of WNK4 to respond to acute changes in intracellular chloride concentration.

As discussed above, potassium also influences sodium chloride reabsorption, via NKCC2, in the thick ascending limb, and NKCC2 is regulated by WNK-SPAK/OSR1 signaling, although other kinases also contribute to NKCC2 phosphorylation [26,78,105–107,108*,109]. However, studies have shown variable effects on NKCC2 in response to potassium loading [34,43*,110*], and there was no difference in total or phosphorylated NKCC2 in the chloride-insensitive WNK4 mutant mice in whole-kidney lysates (Chen et al., unpublished data). Thus, whether intracellular chloride could regulate WNK-SPAK/OSR1-mediated NKCC2 phosphorylation and activity in response to changes in potassium is, so far, unclear, and other mechanisms for NKCC2 regulation (for example, membrane trafficking) could also play a role [111,112]. Interestingly, while Kir4.1/5.1 is the sole potassium conductance on the basolateral membrane of the DCT, it coexists with other potassium channels on the basolateral thick ascending limb [113]. This may make the DCT more sensitive to hormonal regulators of Kir4.1/5.1, such as bradykinin or angiotensin II [114,115].

Conclusion and Future Directions

Substantial evidence supports a role for chloride-regulated WNK signaling in mediating changes in NCC activity in response to perturbations in potassium homeostasis, particularly low potassium diet. WNK paralogs interact [116], influencing WNK activity [117]. A recent study demonstrated that co-expression in Xenopus oocytes of a WNK1 isoform lacking the kinase domain, KS-WNK1, increases WNK4 chloride sensitivity [118**]. Further studies are needed to understand the effects of low or high potassium diets on WNK heteromers. Furthermore, perturbations in potassium homeostasis result in the formation of KS-WNK1-dependent “WNK bodies,” consisting of KS-WNK1, WNK4, SPAK, and OSR1, in cultured cells and mouse and human DCT [49,101,119–121,122*,123*]. Whether and how WNK bodies interact with chloride regulation of WNKs remains unknown. Future studies should further elucidate the elegant mechanisms by which the kidney achieves potassium homeostasis, with important implications for maintaining normokalemia and normotension.

Key points.

A low potassium diet is associated with higher blood pressure and increased mortality, and both hypo- and hyperkalemia are associated with morbidity and mortality in human populations.

Low potassium diet increases the phosphorylation and activity of the sodium chloride-reabsorbing sodium chloride cotransporter in the distal convoluted tubule through the activation of the WNK (With No Lysine)-SPAK/OSR1 (Ste20-related proline/alanine rich kinase/oxidative stress response) kinase cascade.

Basolateral potassium and chloride channels in the distal convoluted tubule provide a mechanism for lowering of intracellular chloride in response to low potassium diet.

Relief of chloride inhibition of WNK allows pathway activation by low potassium diet.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Dr. Alicia McDonough for insightful discussion of the effect of varying dietary potassium on NKCC2, and Dr. Chih-Jen Cheng for sharing unpublished data on chloride-insensitive WNK4 knockin mice.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the Department of Internal Medicine and Molecular Medicine Program, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, the US Department of Veterans Affairs, the National Institutes of Health (R01DK110358) and the American Heart Association (16CSA28530002).

Funding: The author is supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01DK110358) and the American Heart Association (16CSA28530002).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None.

References

- 1.Einhorn LM, Zhan M, Hsu VD, Walker LD, Moen MF, Seliger SL, et al. The frequency of hyperkalemia and its significance in chronic kidney disease. Arch Intern Med. American Medical Association; 2009. June 22;169(12):1156–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Korgaonkar S, Tilea A, Gillespie BW, Kiser M, Eisele G, Finkelstein F, et al. Serum potassium and outcomes in CKD: insights from the RRI-CKD cohort study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010. May;5(5):762–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowling CB, Pitt B, Ahmed MI, Aban IB, Sanders PW, Mujib M, et al. Hypokalemia and outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure and chronic kidney disease: findings from propensity-matched studies. Circ Heart Fail. 2010. March;3(2):253–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goyal A, Spertus JA, Gosch K, Venkitachalam L, Jones PG, Van den Berghe G, et al. Serum potassium levels and mortality in acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2012. January 11;307(2):157–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luo J, Brunelli SM, Jensen DE, Yang A. Association between Serum Potassium and Outcomes in Patients with Reduced Kidney Function. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2016. January 7;11(1):90–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Y, Chang AR, McAdams DeMarco MA, Inker LA, Matsushita K, Ballew SH, et al. Serum Potassium, Mortality, and Kidney Outcomes in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016. October;91(10):1403–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krogager ML, Torp-Pedersen C, Mortensen RN, Køber L, Gislason G, Søgaard P, et al. Short-term mortality risk of serum potassium levels in hypertension: a retrospective analysis of nationwide registry data. Eur Heart J. 2017. January 7;38(2):104–12.* Retrospective analysis of Danish patients with hypertension, showing lowest mortality risk in patient with serum potassium in the range of 4.1 – 4.7 mmol/L.

- 8.Hughes-Austin JM, Rifkin DE, Beben T, Katz R, Sarnak MJ, Deo R, et al. The Relation of Serum Potassium Concentration with Cardiovascular Events and Mortality in Community-Living Individuals. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017. February 7;12(2):245–52.* Analysis of individuals, free of baseline cardiovascular disease, enrolled in the MESA and CHS cohorts, showing least morbidity and mortality with serum potassium in the range of 4.0 to 4.4 mEq/L.

- 9.Collins AJ, Pitt B, Reaven N, Funk S, McGaughey K, Wilson D, et al. Association of Serum Potassium with All-Cause Mortality in Patients with and without Heart Failure, Chronic Kidney Disease, and/or Diabetes. Am J Nephrol. 2017;46(3):213–21.* Demonstrates U-shaped associations between serum potassium and mortality in patients with heart failure, chronic kidney disease, diabetes mellitus, and individuals without these comorbidities.

- 10.Furuland H, McEwan P, Evans M, Linde C, Ayoubkhani D, Bakhai A, et al. Serum potassium as a predictor of adverse clinical outcomes in patients with chronic kidney disease: new risk equations using the UK clinical practice research datalink. BMC Nephrology. 2018. August 22;19(1):211.* Demonstrates U-shaped associations between serum potassium and mortality and cardiovascular events in patients with chronic kidney disease.

- 11.Gasparini A, Evans M, Barany P, Xu H, Jernberg T, Arnlov J, et al. Plasma potassium ranges associated with mortality across stages of chronic kidney disease: the Stockholm CREAtinine Measurements (SCREAM) project. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2018. August 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kovesdy CP, Matsushita K, Sang Y, Brunskill NJ, Carrero JJ, Chodick G, et al. Serum potassium and adverse outcomes across the range of kidney function: a CKD Prognosis Consortium meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2018. May 1;39(17):1535–42.* Meta-analysis of 27 international cohorts with or without chronic kidney disease, demonstrating lowest risk of mortality with serum potassium between 4 and 4.5 mmol/L.

- 13.Aburto NJ, Hanson S, Gutierrez H, Hooper L, Elliott P, Cappuccio FP. Effect of increased potassium intake on cardiovascular risk factors and disease: systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ. 2013;346:f1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mente A, O’Donnell MJ, Rangarajan S, McQueen MJ, Poirier P, Wielgosz A, et al. Association of urinary sodium and potassium excretion with blood pressure. N Engl J Med. 2014. August 14;371(7):601–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Donnell M, Mente A, Rangarajan S, McQueen MJ, Wang X, Liu L, et al. Urinary sodium and potassium excretion, mortality, and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2014. August 14;371(7):612–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malnic G, Giebisch G, Muto S, Wang W, Bailey MA, Satlin LM. Regulation of K+ excretion In: Alpern RJ, Moe OW, Caplan MJ, editors. Seldin and Giebisch’s The Kidney. 5 ed. Burlington: Elsevier; 2013. pp. 1659–715. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keith NM, Binger MW. Diuretic action of potassium salts. JAMA. American Medical Association; 1935. November 16;105(20):1584–91. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Womersley RA, Darragh JH. Potassium and sodium restriction in the normal human. J Clin Invest. 1955. March;34(3):456–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krishna GG, Miller E, Kapoor S. Increased blood pressure during potassium depletion in normotensive men. N Engl J Med. 1989. May 4;320(18):1177–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brandis M, Keyes J, Windhager EE. Potassium-induced inhibition of proximal tubular fluid reabsorption in rats. Am J Physiol. 1972. February;222(2):421–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weinstein AM. A mathematical model of the rat kidney: K+-induced natriuresis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2017. June 1;312(6):F925–50.* Models the natriuretic effect of increasing plasma potassium, using a mathematical model of the rat nephron with addition of medullary vasculature, with greatest effects on kaliuresis deriving from decreased proximal sodium reabsorption.

- 22.Battilana CA, Dobyan DC, Lacy FB, Bhattacharya J, Johnston PA, Jamison RL. Effect of chronic potassium loading on potassium secretion by the pars recta or descending limb of the juxtamedullary nephron in the rat. J Clin Invest. American Society for Clinical Investigation; 1978. November;62(5):1093–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stokes JB. Consequences of potassium recycling in the renal medulla. Effects of ion transport by the medullary thick ascending limb of Henle’s loop. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1982. August;70(2):219–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kirchner KA. Effect of acute potassium infusion on loop segment chloride reabsorption in the rat. Am J Physiol. 1983. June;244(6):F599–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higashihara E, Kokko JP. Effects of aldosterone on potassium recycling in the kidney of adrenalectomized rats. Am J Physiol. 1985. February;248(2 Pt 2):F219–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng C-J, Truong T, Baum M, Huang C-L. Kidney-specific WNK1 inhibits sodium reabsorption in the cortical thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012. September;303(5):F667–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gitelman HJ, Graham JB, Welt LG. A new familial disorder characterized by hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia. Trans Assoc Am Physicians. 1966;79:221–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simon DB, Nelson-Williams C, Bia MJ, Ellison D, Karet FE, Molina AM, et al. Gitelman”s variant of Bartter”s syndrome, inherited hypokalaemic alkalosis, is caused by mutations in the thiazide-sensitive Na-Cl cotransporter. Nat Genet. 1996. January;12(1):24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hadchouel J, Ellison DH, Gamba G. Regulation of Renal Electrolyte Transport by WNK and SPAK-OSR1 Kinases. Annu Rev Physiol. 2016. February 10;78:367–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ellison DH, Velázquez H, Wright FS. Thiazide-sensitive sodium chloride cotransport in early distal tubule. Am J Physiol. 1987. September;253(3 Pt 2):F546–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gamba G, Miyanoshita A, Lombardi M, Lytton J, Lee WS, Hediger MA, et al. Molecular cloning, primary structure, and characterization of two members of the mammalian electroneutral sodium-(potassium)-chloride cotransporter family expressed in kidney. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994. July 1;269(26):17713–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pacheco-Alvarez D, Cristóbal PS, Meade P, Moreno E, Vazquez N, Muñoz E, et al. The Na+:Cl- cotransporter is activated and phosphorylated at the amino-terminal domain upon intracellular chloride depletion. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006. September 29;281(39):28755–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Richardson C, Rafiqi FH, Karlsson HKR, Moleleki N, Vandewalle A, Campbell DG, et al. Activation of the thiazide-sensitive Na+-Cl- cotransporter by the WNK-regulated kinases SPAK and OSR1. J Cell Sci. The Company of Biologists Ltd; 2008. March 1;121(Pt 5):675–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rengarajan S, Lee DH, Oh YT, Delpire E, Youn JH, McDonough AA. Increasing plasma [K+] by intravenous potassium infusion reduces NCC phosphorylation and drives kaliuresis and natriuresis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. American Physiological Society; 2014. May 1;306(9):F1059–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Veiras LC, Girardi ACC, Curry J, Pei L, Ralph DL, Tran A, et al. Sexual Dimorphic Pattern of Renal Transporters and Electrolyte Homeostasis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017. December;28(12):3504–17.* Highlights sexual dimorphism in baseline nephron transporter expression, and male and female responses to potassium load.

- 36.Penton D, Czogalla J, Wengi A, Himmerkus N, Loffing-Cueni D, Carrel M, et al. Extracellular K+ rapidly controls NaCl cotransporter phosphorylation in the native distal convoluted tubule by Cl- -dependent and independent mechanisms. J Physiol (Lond). 2016. November 1;594(21):6319–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sorensen MV, Grossmann S, Roesinger M, Gresko N, Todkar AP, Barmettler G, et al. Rapid dephosphorylation of the renal sodium chloride cotransporter in response to oral potassium intake in mice. Kidney International. 2013. May;83(5):811–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jensen IS, Larsen CK, Leipziger J, Sorensen MV. Na(+) dependence of K(+) -induced natriuresis, kaliuresis and Na(+) /Cl(−) cotransporter dephosphorylation. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2016. September;218(1):49–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frindt G, Yang L, Uchida S, Weinstein AM, Palmer LG. Responses of distal nephron Na+ transporters to acute volume depletion and hyperkalemia. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2017. July 1;313(1):F62–F73.** Based on experimental studies examining NCC phosphorylation in response to varying combinations of amiloride, furosemide and hydrochlorothiazide, models the relationship between extracellular potassium or intracellular chloride and NCC phosphorylation, with lack of correlation between calculated intracellular chloride and NCC phosphorylation.

- 40.Wade JB, Fang L, Coleman RA, Liu J, Grimm PR, Wang T, et al. Differential regulation of ROMK (Kir1.1) in distal nephron segments by dietary potassium. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011. June;300(6):F1385–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Frindt G, Palmer LG. Effects of dietary K on cell-surface expression of renal ion channels and transporters. AJP: Renal Physiology. 2010. October 1;299(4):F890–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van der Lubbe N, Moes AD, Rosenbaek LL, Schoep S, Meima ME, Danser AHJ, et al. K+-induced natriuresis is preserved during Na+ depletion and accompanied by inhibition of the Na+-Cl- cotransporter. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2013. October 15;305(8):F1177–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang L, Xu S, Guo X, Uchida S, Weinstein AM, Wang T, et al. Regulation of renal Na transporters in response to dietary K. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2018. October 1;315(4):F1032–41.* Demonstrates decreased NKCC2 phosphorylation in male mice on high potassium diet, and models quantitative effect of decreased sodium reabsorption in different nephron segments on kaliuresis, with greatest effects of proximal tubule and smaller effects of thick ascending limb and DCT.

- 44.Yang L, Frindt G, Lang F, Kuhl D, Vallon V, Palmer LG. SGK1-dependent ENaC processing and trafficking in mice with high dietary K intake and elevated aldosterone. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2017. January 1;312(1):F65–F76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vallon V, Schroth J, Lang F, Kuhl D, Uchida S. Expression and phosphorylation of the Na+-Cl- cotransporter NCC in vivo is regulated by dietary salt, potassium, and SGK1. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009. September;297(3):F704–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Castañeda-Bueno M, Cervantes-Perez LG, Rojas-Vega L, Arroyo-Garza I, Vazquez N, Moreno E, et al. Modulation of NCC activity by low and high K(+) intake: insights into the signaling pathways involved. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2014. June 15;306(12):F1507–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wade JB, Liu J, Coleman R, Grimm PR, Delpire E, Welling PA. SPAK-mediated NCC regulation in response to low-K+ diet. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2015. April 15;308(8):F923–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Frindt G, Houde V, Palmer LG. Conservation of Na+ vs. K+ by the rat cortical collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011. July;301(1):F14–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Terker AS, Zhang C, McCormick JA, Lazelle RA, Zhang C, Meermeier NP, et al. Potassium modulates electrolyte balance and blood pressure through effects on distal cell voltage and chloride. Cell Metab. 2015. January 6;21(1):39–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vitzthum H, Seniuk A, Schulte LH, Müller ML, Hetz H, Ehmke H. Functional coupling of renal K+ and Na+ handling causes high blood pressure in Na+ replete mice. J Physiol (Lond). 2014. March 1;592(Pt 5):1139–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Terker AS, Zhang C, Erspamer KJ, Gamba G, Yang C-L, Ellison DH. Unique chloride-sensing properties of WNK4 permit the distal nephron to modulate potassium homeostasis. Kidney International. 2016. January;89(1):127–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gamba G Molecular physiology and pathophysiology of electroneutral cation-chloride cotransporters. Physiological Reviews. 2005. April;85(2):423–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Russell JM. Chloride and sodium influx: a coupled uptake mechanism in the squid giant axon. J Gen Physiol. 1979. June;73(6):801–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Breitwieser GE, Altamirano AA, Russell JM. Osmotic stimulation of Na(+)-K(+)-Cl- cotransport in squid giant axon is [Cl-]i dependent. Am J Physiol. 1990. April;258(4 Pt 1):C749–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Breitwieser GE, Altamirano AA, Russell JM. Elevated [Cl-]i, and [Na+]i inhibit Na+, K+, Cl- cotransport by different mechanisms in squid giant axons. J Gen Physiol. Rockefeller Univ Press; 1996. February 1;107(2):261–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Robertson MA, Foskett JK. Na+ transport pathways in secretory acinar cells: membrane cross talk mediated by [Cl-]i. Am J Physiol. 1994. July;267(1 Pt 1):C146–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lytle C, Forbush B. Regulatory phosphorylation of the secretory Na-K-Cl cotransporter: modulation by cytoplasmic Cl. Am J Physiol. 1996. February;270(2 Pt 1):C437–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Isenring P, Jacoby SC, Payne JA, Forbush B. Comparison of Na-K-Cl cotransporters. NKCC1, NKCC2, and the HEK cell Na-L-Cl cotransporter. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998. May 1;273(18):11295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ponce-Coria J, San-Cristobal P, Kahle KT, Vazquez N, Pacheco-Alvarez D, de Los Heros P, et al. Regulation of NKCC2 by a chloride-sensing mechanism involving the WNK3 and SPAK kinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008. June 17;105(24):8458–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Riordan JR, Forbush B, Hanrahan JW. The molecular basis of chloride transport in shark rectal gland. Journal of Experimental Biology. 1994. November;196:405–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Palygin O, Pochynyuk O, Staruschenko A. Distal tubule basolateral potassium channels: cellular and molecular mechanisms of regulation. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2018. Sep;27(5):373–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Su X-T, Wang W-H. The expression, regulation, and function of Kir4.1 (Kcnj10) in the mammalian kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016. July 1;311(1):F12–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Staruschenko A Beneficial Effects of High Potassium: Contribution of Renal Basolateral K+ Channels. Hypertension. 2018. June;71(6):1015–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zaika O, Tomilin V, Mamenko M, Bhalla V, Pochynyuk O. New perspective of ClC-Kb/2 Cl- channel physiology in the distal renal tubule. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016. May 15;310(10):F923–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Teulon J, Planelles G, Sepúlveda FV, Andrini O, Lourdel S, Paulais M. Renal Chloride Channels in Relation to Sodium Chloride Transport. Compr Physiol. 2018. Dec 13;9(1):301–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Scholl UI, Choi M, Liu T, Ramaekers VT, Häusler MG, Grimmer J, et al. Seizures, sensorineural deafness, ataxia, mental retardation, and electrolyte imbalance (SeSAME syndrome) caused by mutations in KCNJ10. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009. April 7;106(14):5842–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bockenhauer D, Feather S, Stanescu HC, Bandulik S, Zdebik AA, Reichold M, et al. Epilepsy, ataxia, sensorineural deafness, tubulopathy, and KCNJ10 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2009. May 7;360(19):1960–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Birkenhäger R, Otto E, Schürmann MJ, Vollmer M, Ruf EM, Maier-Lutz I, et al. Mutation of BSND causes Bartter syndrome with sensorineural deafness and kidney failure. Nat Genet. 2001. November;29(3):310–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Simon DB, Bindra RS, Mansfield TA, Nelson-Williams C, Mendonca E, Stone R, et al. Mutations in the chloride channel gene, CLCNKB, cause Bartter’s syndrome type III. Nat Genet. 1997. October;17(2):171–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang M-X, Cuevas CA, Su X-T, Wu P, Gao Z-X, Lin D-H, et al. Potassium intake modulates the thiazide-sensitive sodium-chloride cotransporter (NCC) activity via the Kir4.1 potassium channel. Kidney International. 2018. April;93(4):893–902.** Demonstrates effects of low and high potassium diets on DCT potassium and chloride currents, and basolateral membrane potential, in control vs. KCNJ10 (encoding Kir4.1) nephron knockout mice, demonstrating the importance of Kir4.1 for these responses.

- 71.Cuevas CA, Su X-T, Wang M-X, Terker AS, Lin D-H, McCormick JA, et al. Potassium Sensing by Renal Distal Tubules Requires Kir4.1. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017. June;28(6):1814–25.** Demonstrates importance of Kir4.1 for basal levels of total and phosphorylated NCC, NCC phosphorylation in response to changes in plasma potassium, and systemic plasma homeostasis.

- 72.Malik S, Lambert E, Zhang J, Wang T, Clark H, Cypress M, et al. Potassium Conservation is Impaired in Mice with Reduced Renal Expression of Kir4.1. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2018. August 15;315:F1271–82.* Demonstrates that KCNJ10 (Kir4.1) knockdown in the kidney impairs NCC phosphorylation in response to low potassium diet, resulting in severe hypokalemia.

- 73.Zhang C, Wang L, Zhang J, Su XT, Lin DH, Scholl UI, et al. KCNJ10 determines the expression of the apical Na-Cl cotransporter (NCC) in the early distal convoluted tubule (DCT1). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014. August 12;111(32):11864–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nomura N, Shoda W, Wang Y, Mandai S, Furusho T, Takahashi D, et al. Role of ClC-K and barttin in low potassium-induced sodium chloride cotransporter activation and hypertension in mouse kidney. Biosci Rep. 2018. February 28;38(1).* Demonstrates requirement for barttin in increasing SPAK activation and NCC phosphorylation in response to low potassium diet, and in the hypertensive effect of a high sodium/low potassium diet.

- 75.Anselmo AN, Earnest S, Chen W, Juang Y-C, Kim SC, Zhao Y, et al. WNK1 and OSR1 regulate the Na+, K+, 2Cl- cotransporter in HeLa cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006. July 18;103(29):10883–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dowd BFX, Forbush B. PASK (proline-alanine-rich STE20-related kinase), a regulatory kinase of the Na-K-Cl cotransporter (NKCC1). J Biol Chem. 2003. July 25;278(30):27347–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gagnon KBE, England R, Delpire E. Volume sensitivity of cation-Cl- cotransporters is modulated by the interaction of two kinases: Ste20-related proline-alanine-rich kinase and WNK4. AJP: Cell Physiology. 2006. January;290(1):C134–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Richardson C, Sakamoto K, de Los Heros P, Deak M, Campbell DG, Prescott AR, et al. Regulation of the NKCC2 ion cotransporter by SPAK-OSR1-dependent and -independent pathways. J Cell Sci. 2011. March 1;124(Pt 5):789–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Vitari AC, Thastrup J, Rafiqi FH, Deak M, Morrice NA, Karlsson HKR, et al. Functional interactions of the SPAK/OSR1 kinases with their upstream activator WNK1 and downstream substrate NKCC1. Biochem J. 2006. July 1;397(1):223–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Moriguchi T, Urushiyama S, Hisamoto N, Iemura S-I, Uchida S, Natsume T, et al. WNK1 regulates phosphorylation of cation-chloride-coupled cotransporters via the STE20-related kinases, SPAK and OSR1. Journal of Biological Chemistry. American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology; 2005. December 30;280(52):42685–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Piala AT, Moon TM, Akella R, He H, Cobb MH, Goldsmith EJ. Chloride sensing by WNK1 involves inhibition of autophosphorylation. Sci Signal. 2014. May 6;7(324):ra41–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bazua-Valenti S, Chavez-Canales M, Rojas-Vega L, González-Rodríguez X, Vazquez N, Rodríguez-Gama A, et al. The Effect of WNK4 on the Na+-Cl- Cotransporter Is Modulated by Intracellular Chloride. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015. August;26(8):1781–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gagnon KBE, England R, Delpire E. Characterization of SPAK and OSR1, regulatory kinases of the Na-K-2Cl cotransporter. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2006. January;26(2):689–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Naito S, Ohta A, Sohara E, Ohta E, Rai T, Sasaki S, et al. Regulation of WNK1 kinase by extracellular potassium. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2010. November 25;15(2):195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yang Y-S, Xie J, Yang S-S, Lin S-H, Huang C-L. Differential roles of WNK4 in regulation of NCC in vivo. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2018. January 31;299(487):F890.** Demonstrates that WNK4 knockout mice fail to increase total and phosphorylated NCC, and NCC activity, in response to low dietary potassium, while the ability to upregulate NCC in response to increased sodium delivery (via furosemide administration) is unimpaired.

- 86.Ferdaus MZ, Barber KW, López-Cayuqueo KI, Terker AS, Argaiz ER, Gassaway BM, et al. SPAK and OSR1 play essential roles in potassium homeostasis through actions on the distal convoluted tubule. J Physiol (Lond). 2016. September 1;594(17):4945–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wu Y, Schellinger JN, Huang C-L, Rodan AR. Hypotonicity stimulates potassium flux through the WNK-SPAK/OSR1 kinase cascade and the Ncc69 sodium-potassium-2-chloride cotransporter in the Drosophila renal tubule. J Biol Chem. 2014. September 19;289(38):26131–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sun Q, Wu Y, Jonusaite S, Pleinis JM, Humphreys JM, He H, et al. Intracellular Chloride and Scaffold Protein Mo25 Cooperatively Regulate Transepithelial Ion Transport through WNK Signaling in the Malpighian Tubule. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018. May;29(5):1449–61.* Demonstrates that Drosophila renal tubule WNK activity is increased in conditions in which intracellular chloride decreases, and that expression of chloride-insensitive WNK, together with Mo25, increases transepithelial ion transport.

- 89.Ianowski JP, O’Donnell MJ. Basolateral ion transport mechanisms during fluid secretion by Drosophila Malpighian tubules: Na+ recycling, Na+:K+:2Cl- cotransport and Cl- conductance. Journal of Experimental Biology. 2004. July;207(Pt 15):2599–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Castañeda-Bueno M, Cervantes-Perez LG, Vazquez N, Uribe N, Kantesaria S, Morla L, et al. Activation of the renal Na+:Cl- cotransporter by angiotensin II is a WNK4-dependent process. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. National Acad Sciences; 2012. May 15;109(20):7929–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Takahashi D, Mori T, Nomura N, Khan MZH, Araki Y, Zeniya M, et al. WNK4 is the major WNK positively regulating NCC in the mouse kidney. 2014;34(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Shoda W, Nomura N, Ando F, Mori Y, Mori T, Sohara E, et al. Calcineurin inhibitors block sodium-chloride cotransporter dephosphorylation in response to high potassium intake. Kidney International. 2017. February;91(2):402–11.* Highlights a potential role for calcineurin in oral potassium gavage-induced NCC dephosphorylation.

- 93.Lazelle RA, McCully BH, Terker AS, Himmerkus N, Blankenstein KI, Mutig K, et al. Renal Deletion of 12 kDa FK506-Binding Protein Attenuates Tacrolimus-Induced Hypertension. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016. May;27(5):1456–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Picard N, Trompf K, Yang CL, Miller RL, Carrel M, Loffing-Cueni D, et al. Protein Phosphatase 1 Inhibitor-1 Deficiency Reduces Phosphorylation of Renal NaCl Cotransporter and Causes Arterial Hypotension. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2014. February 28;25(3):511–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kaissling B, Stanton BA. Adaptation of distal tubule and collecting duct to increased sodium delivery. I. Ultrastructure. Am J Physiol. 1988. December;255(6 Pt 2):F1256–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Stanton BA, Kaissling B. Adaptation of distal tubule and collecting duct to increased Na delivery. II. Na+ and K+ transport. Am J Physiol. 1988. December;255(6 Pt 2):F1269–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ellison DH, Velázquez H, Wright FS. Adaptation of the distal convoluted tubule of the rat. Structural and functional effects of dietary salt intake and chronic diuretic infusion. J Clin Invest. American Society for Clinical Investigation; 1989. January;83(1):113–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Loffing J, Vallon V, Loffing-Cueni D, Aregger F, Richter K, Pietri L, et al. Altered renal distal tubule structure and renal Na(+) and Ca(2+) handling in a mouse model for Gitelman’s syndrome. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2004. September;15(9):2276–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Schultheis PJ, Lorenz JN, Meneton P, Nieman ML, Riddle TM, Flagella M, et al. Phenotype resembling Gitelman’s syndrome in mice lacking the apical Na+-Cl- cotransporter of the distal convoluted tubule. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998. October 30;273(44):29150–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Saritas T, Puelles VG, Su X-T, McCormick JA, Welling PA, Ellison DH. Optical Clearing in the Kidney Reveals Potassium-Mediated Tubule Remodeling. Cell Rep. 2018. December 4;25(10):2668–2675.e3.** Demonstrates rapid changes in tubule epithelial cell proliferation and morphology in multiple nephron segments in response to low potassium diet or KCNJ10 knockout.

- 101.Grimm PR, Taneja TK, Liu J, Coleman R, Chen Y-Y, Delpire E, et al. SPAK isoforms and OSR1 regulate sodium-chloride co-transporters in a nephron-specific manner. J Biol Chem. 2012. November 2;287(45):37673–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Grimm PR, Coleman R, Delpire E, Welling PA. Constitutively Active SPAK Causes Hyperkalemia by Activating NCC and Remodeling Distal Tubules. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017. September;28(9):2597–606.** Demonstrates remodeling of the aldosterone-sensitive distal nephron in response to SPAK knockout in the first part of the DCT (DCT1), with DCT1 atrophy and connecting tubule hypertrophy, influencing renal potassium handling.

- 103.Rubera I, Loffing J, Palmer LG, Frindt G, Fowler-Jaeger N, Sauter D, et al. Collecting duct–specific gene inactivation of αENaC in the mouse kidney does not impair sodium and potassium balance. Journal of Clinical Investigation. American Society for Clinical Investigation; 2003. August 15;112(4):554–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.A mathematical model of rat distal convoluted tubule. II. Potassium secretion along the connecting segment. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005. October;289(4):F721–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rafiqi FH, Zuber AM, Glover M, Richardson C, Fleming S, Jovanović S, et al. Role of the WNK-activated SPAK kinase in regulating blood pressure. EMBO Mol Med. 2010. February 4;2(2):63–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.McCormick JA, Mutig K, Nelson JH, Saritas T, Hoorn EJ, Yang C-L, et al. A SPAK Isoform Switch Modulates Renal Salt Transport and Blood Pressure. Cell Metab. 2011. September;14(3):352–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lin S-H, Yu I-S, Jiang S-T, Lin S-W, Chu P, Chen A, et al. Impaired phosphorylation of Na(+)-K(+)-2Cl(−) cotransporter by oxidative stress-responsive kinase-1 deficiency manifests hypotension and Bartter-like syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. National Acad Sciences; 2011. October 18;108(42):17538–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Terker AS, Castañeda-Bueno M, Ferdaus MZ, Cornelius RJ, Erspamer KJ, Su X-T, et al. With no lysine kinase 4 modulates sodium potassium 2 chloride cotransporter activity in vivo. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2018. October 1;315(4):F781–90.* Demonstrates a role for WNK4 in regulating NKCC2.

- 109.Cheng C-J, Yoon J, Baum M, Huang C-L. STE20/SPS1-related proline/alanine-rich kinase (SPAK) is critical for sodium reabsorption in isolated, perfused thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2015. March 1;308(5):F437–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Palygin O, Levchenko V, Ilatovskaya DV, Pavlov TS, Pochynyuk OM, Jacob HJ, et al. Essential role of Kir5.1 channels in renal salt handling and blood pressure control. JCI Insight. 2017. September 21;2(18):1289.* Deletion of Kir5.1 in salt-sensitive rats abolishes the hypertensive effect of a high-salt diet.

- 111.Ares GR, Caceres PS, Ortiz PA. Molecular regulation of NKCC2 in the thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011. December;301(6):F1143–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Mutig K Trafficking and regulation of the NKCC2 cotransporter in the thick ascending limb. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2017. September;26(5):392–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Zhang C, Wang L, Su X-T, Lin D-H, Wang W-H. KCNJ10 (Kir4.1) is expressed in the basolateral membrane of the cortical thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2015. June 1;308(11):F1288–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zhang D-D, Gao Z-X, Vio CP, Xiao Y, Wu P, Zhang H, et al. Bradykinin Stimulates Renal Na+ and K+ Excretion by Inhibiting the K+ Channel (Kir4.1) in the Distal Convoluted Tubule. Hypertension. 2018. August;72(2):361–9.* Proposes a role for bradykinin as a hormonal regulator of Kir4.1 activity and systemic potassium homeostasis.

- 115.Wu P, Gao Z-X, Duan X-P, Su X-T, Wang M-X, Lin D-H, et al. AT2R (Angiotensin II Type 2 Receptor)-Mediated Regulation of NCC (Na-Cl Cotransporter) and Renal K Excretion Depends on the K Channel, Kir4.1. Hypertension. 2018. April;71(4):622–30.* Proposes a role for angiotensin II signaling through the AT2 receptor in the regulation of Kir4.1 activity and systemic potassium homeostasis.

- 116.Thastrup JO, Rafiqi FH, Vitari AC, Pozo Guisado E, Deak M, Mehellou Y, et al. SPAK/OSR1 regulate NKCC1 and WNK activity: analysis of WNK isoform interactions and activation by T-loop trans-autophosphorylation. Biochem J. 2012. January 1;441(1):325–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Chavez-Canales M, Zhang C, Soukaseum C, Moreno E, Pacheco-Alvarez D, Vidal-Petiot E, et al. WNK-SPAK-NCC cascade revisited: WNK1 stimulates the activity of the Na-Cl cotransporter via SPAK, an effect antagonized by WNK4. Hypertension. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014. November;64(5):1047–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Argaiz ER, Chavez-Canales M, Ostrosky-Frid M, Rodríguez-Gama A, Vazquez N, González-Rodríguez X, et al. Kidney-specific WNK1 isoform (KS-WNK1) is a potent activator of WNK4 and NCC. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2018. May 30;306(3):F1507–745.** KS-WNK1 binds WNK4 and stimulates its autophosphorylation in Xenopus oocytes in conditions of relatively high intracellular chloride, in which WNK4 autophosphorylation does not otherwise occur.

- 119.Al-Qusairi L, Basquin D, Roy A, Stifanelli M, Rajaram RD, Debonneville A, et al. Renal tubular SGK1 deficiency causes impaired K+ excretion via loss of regulation of NEDD4–2/WNK1 and ENaC. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016. August 1;311(2):F330–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Al-Qusairi L, Basquin D, Roy A, Rajaram RD, Maillard MP, Subramanya AR, et al. Renal Tubular Ubiquitin-Protein Ligase NEDD4–2 Is Required for Renal Adaptation during Long-Term Potassium Depletion. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2017. March 13;:ASN.2016070732–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Schumacher FR, Siew K, Zhang J, Johnson C, Wood N, Cleary SE, et al. Characterisation of the Cullin-3 mutation that causes a severe form of familial hypertension and hyperkalaemia. EMBO Mol Med. 2015. October 1;7(10):1285–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Boyd-Shiwarski CR, Shiwarski DJ, Roy A, Namboodiri HN, Nkashama LJ, Xie J, et al. Potassium-regulated distal tubule WNK bodies are kidney-specific WNK1 dependent. Mol Biol Cell. 2018. February 15;29(4):499–509.* Demonstrates a role for KS-WNK1, and particularly a cysteine-rich motif in the 4a exon of KS-WNK1, for the formation of WNK bodies in cultured cells and DCT in response to low or high potassium.

- 123.Thomson MN, Schneider W, Mutig K, Ellison DH, Kettritz R, Bachmann S. Patients with hypokalemia develop WNK bodies in the distal convoluted tubule of the kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2018. November 28;:ajprenal.00464.2018.* Demonstrates the presence of WNK bodies in kidneys from patients with hypokalemia.