Abstract

Caged compounds enable fast, light-induced, and spatially-defined application of bioactive molecules to cells. Covalent attachment of a caging chromophore to a crucial functionality of a biomolecule renders it inert, while short pulses of light release the caged molecule in its active form. Caged neurotransmitters have been widely used to study diverse neurobiological processes such as receptor distribution, synaptogenesis, transport, and long-term potentiation. Since the neurotransmitters glutamate and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) are the most important, they have been studied extensively using uncaging. However, to be able to probe their interactions on a physiologically relevant timescale, fast and independent application of both neurotransmitters in an arbitrary order is desired. This can be achieved by combining two caging chromophores absorbing non-overlapping and thus orthogonal wavelengths of light, which enables the precise application of two caged molecules to the same preparation in any order, a technique called two-color uncaging. In this chapter, we describe the principles of orthogonal two-color uncaging with one- and two-photon excitation with an emphasis on caged glutamate and GABA. We then give a guide to its practical application and highlight some key studies utilizing this technique.

Keywords: uncaging, two-color, one-photon, two-photon, glutamate, GABA, neurophysiology

1. Introduction

1.1. The idea of orthogonality

In 1977, Bruce Merrifield stated: “An orthogonal system is defined as a set of completely independent classes of protecting groups. In a system of this kind, each class of groups can be removed in any order and in the presence of all other classes.” (Barany & Merrifield, 1977). This is a historically-conditioned, chemical expression of a fundamental control problem by someone who met this challenge in his own field using the diversity of chemical reagents which allow such independence to be achieved. Such chemo-selective reactions are part and parcel of thermally activated functional protecting groups now standard in organic chemistry that enable multi-factorial, independent manipulation. However, the use of a single reagent, namely, light, presents an inherent challenge for photochemically-driven chromatic orthogonality (Fig. 1). This problem has been highlighted recently in chemistry and biology approaches to selective two-color actuation. First, chemists (Hagen and co-workers) have said: “A real chromatic orthogonality as introduced by Bochet, where the cleavage of protecting groups can be performed in any order, is improbable. This is due to the considerable absorption of all chromophores in the range 300–350 nm. Therefore, the protecting group with a long-wavelength absorption has to be photolyzed first.” (Kotzur et al., 2009; emphasis added). Similarly, biologists (Boyden and co-workers) have stated: “The fundamental limitation in creating an independent two-color channelrhodopsin pair is that all opsins can be driven to some extent by blue light.” (Klapoetke et al., 2014; emphasis added). It is important to appreciate that blue light for opsins is analogous to UV light (300–380 nm) for uncaging. To meet the orthogonality requirement as defined by Merrifield, the long wavelength chromophore must effectively absorb no light at the short wavelength. This scenario is schematized in Figure 1, where such a chromophore, shown in red, has a minimum that complements a shorter wavelength chromophore (shown in purple, centered around λ1). However, since all traditional caging chromophores (and opsins) typically have significant overlap (as illustrated by the blue and purple spectra in Fig. 1), application of short wavelengths (e.g., λ1) activate both compounds. Thus, attempts characterized as “two-color uncaging” are in fact limited to the sequential scenario shown in Figure 1. Here, the long wavelength cage is photolyzed first in its entirety before the short wavelength probe is activated. This does not yield truly orthogonal two-color uncaging which would be favored for most biological applications where activation of signaling processes in an arbitrary order is desired (Fig. 1). In this chapter, we discuss recent advances in the field of two-color actuation which provided us with the tools to perform arbitrarily-ordered two-color uncaging of glutamate and GABA with no functional crosstalk in biological applications and give a guide to the practical application of these techniques.

Figure 1.

Chromatic orthogonality using two-color uncaging. Absorption spectra of three caging chromophores (purple, blue and red) with their respective excitation wavelength (λ1–3). Chromophores with significant overlap in the short wavelength UV range (purple and blue) do not allow chromatically-independent two-color photolysis (middle). Irradiation of a mixture with UV light λ1 releases effectors 1 and 2 (E1/2) simultaneously (shaded). Only sequential two-color uncaging of E1 and E2 is possible with such chromophores. Blue light (λ2) must be used to photolyze E2 fully, before UV light can be used to uncage E1 selectively. In contrast, the longer wavelength chromophore with a complementary minimum (red) shows an idealized situation in which short and long wavelengths (λ1 and λ3) only uncage E1 and E3, respectively (bottom). Thus, full chromatically independent photochemical deprotection is envisaged, one that meets Merrifield’s “orthogonality ideal” (Barany & Merrifield, 1977). In the context of neuronal signaling, this would allow one to apply photostimulation to two receptors any number of times, in any order, with any magnitude and duration. In other words, truly arbitrary two-color uncaging would be achieved.

1.2. Caged compounds

Caged compounds are composed of a chromophore which is covalently attached to a biomolecule (Ellis-Davies, 2007). This photochemical protection renders the biomolecule functionally inactive or inert. Excitation of the chromophore by light breaks the covalent bond, liberating the biomolecule (examples of such uncaging reactions are shown in Fig. 2). This has the obvious advantage that the caged compound can be applied to a biological sample without binding to its target; e.g., a caged neurotransmitter may be delivered right in front of the receptor without activating it. Since light penetrates biological tissue and modern microscopes allow precise application of light, the biomolecule can be uncaged rapidly at a spatially-defined location in a biological sample; e.g., a caged neurotransmitter may be released quickly at a single synapse. This allows studying the underlying receptor signaling on a physiologically-relevant time scale at defined subcellular locations which has been the major issue of many common types of drug application being either too slow or not precise enough. Besides the temporal and spatial freedom that light entails, its power can be regulated, making it tunable in its magnitude.

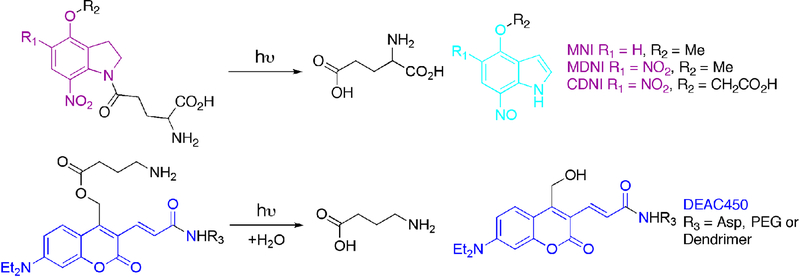

Figure 2.

Examples of neurotransmitter uncaging. Top, structures of 7-nitroindolinyl-caged glutamate probes with the chromophore shown in purple. MNI-Glu is probably the most widely-used optical probe for two-photon photolysis in biology because of its unique combination of properties (see text). Also, it has been commercially available from Tocris since 2004. MDNI-Glu and CDNI-Glu were introduced in 2005 and 2007 (Ellis-Davies, Matsuzaki, Paukert, Kasai, & Bergles, 2007; Fedoryak, Sul, Haydon, & Ellis-Davies, 2005). Both show an improved quantum yield of photolysis compared to MNI; however, each is slowly hydrolyzed at physiological pH. MDNI-Glu has recently been marketed by Femtonics under the trade name DNI-Glu.

Bottom, structures of DEAC450-GABA probes with the chromophore shown in blue. Variation of the substituent R3 significantly changes the GABA-A receptor antagonism of the DEAC450 probes.

Note, the uncaging reaction mechanisms are quite different. Nitroindolinyls produce nitrosoindoles (cyan), but DEAC450 undergoes photosolvolysis, preserving the DEAC450 chromophore upon acid release.

In addition to most naturally-occurring molecules being organic and therefore amenable to caging, the technique also enables caging of non-natural products such as drugs or fluorophores. Furthermore, ions, which may act as important second messenger, have been caged by incorporating chelating molecules into the caged compound. In fact, since Kaplan and colleagues described the first caged biomolecule, caged ATP (Kaplan, Forbush, & Hoffman, 1978), most classes of biologically relevant molecules, such as neurotransmitters, peptides, nucleic acids, drugs, and ions, have been caged (Ellis-Davies, 2007).

Caged compounds need to fulfill certain criteria to be useful for neurophysiology:

Efficient light absorption: As with chromophores used for imaging, efficient absorption of light is also vital for caging chromophores. How well a chromophore absorbs light is given as the extinction coefficient (ε, unit: M–1 cm–1).

Efficient use of absorbed light: While light absorption itself is important, for uncaging it is critical how well excitation translates to release of the caged molecule, a property measured as the quantum yield (QY; Φ, unitless).

Fast release: Most ionotropic neurotransmitter receptors activate on a fast time scale. To be able to mimic endogenous receptor signaling, photolytic release must therefore occur on a time scale faster than the signaling to be activated.

Hydrolytic stability: Depending on the type of covalent bond between the caging chromophore and the biomolecule, this bond may be prone to hydrolysis in aqueous solutions. Stability of the caged compound at physiological pH at least for the duration of the experiment is vital.

Solubility: Caged compounds need to be soluble under physiological conditions at a concentration that will allow efficient uncaging to activate the targeted signaling pathway. Although being organic by nature and as such often insoluble in physiological solution, attaching certain solubilizing groups usually yields sufficient solubility.

Biologically inert: To be effective, caged compounds need to be biologically inert at the working concentration. Attaching the caging chromophore to a functionally crucial side chain of the biomolecule generally renders it inert towards its target receptor.

1.3. Principles of two-color uncaging

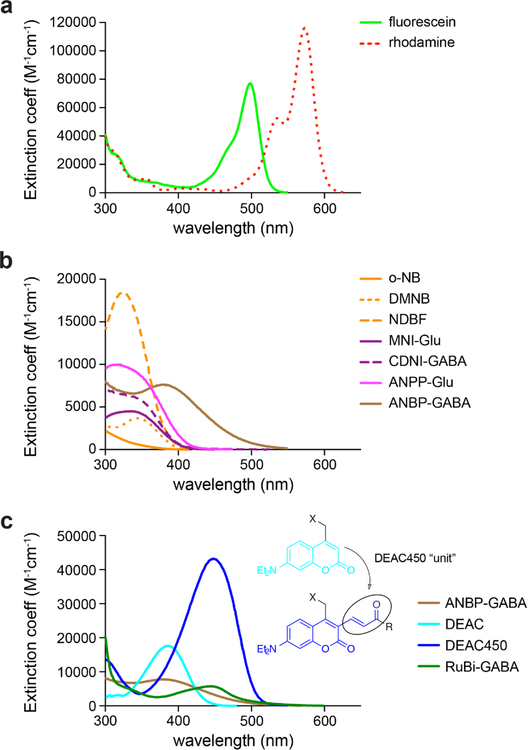

The key feature for successful, wavelength-independent excitation of two chromophores is the lack of excitation of the longer-wavelength chromophore by light used to excite the shorter-wavelength chromophore. The importance of “non-excitation” is easily understood by examination of the spectral overlap of the classic green and red fluorophores fluorescein and rhodamine (Fig. 3a). At the green channel excitation maximum (λmax) the red channel undergoes about 10% excitation compared to the green channel. However, conditions can normally be found for reasonably selective fluorescence imaging of green and red by adjustment of laser powers on a confocal microscope. Further, one is able to subtract the contribution of any optical crosstalk by imaging each color separately. Thus, multi-color fluorescence imaging of fixed as well as live cells works very well such that imaging up to four colors is now standard practice.

Figure 3.

Chromophores for uncaging with near-UV and blue light. (a) The absorption spectra of the fluorescent dyes fluorescein (green line) and rhodamine (red dots). (b) Nitroaromatic caging chromophores which absorb near-UV and violet light. Note that the ANBP chromophore (brown) has an exceptionally long absorption tail that extends into the green. (c) Long wavelength-absorbing caging chromophores absorbing different degrees of short wavelength light. Introducing an acrylate moiety (the “DEAC450 unit”) shifts both, the maximum and minimum of DEAC, to 450 nm and 350 nm, respectively, creating DEAC450. Compared to the long wavelength chromophore RuBi, DEAC450 has a distinct minimum in the near-UV and a larger min-to-max ratio favorable for two-color uncaging.

The most widely used chromophores for uncaging are the ortho-nitrobenzyl (o-NB) (Barltrop, Plant, & Schofield, 1966) and the 4,5-dimethoxy-2-nitrobenzyl (DMNB) (Patchornik, Amit, & Woodward, 1970) groups, which were introduced in 1966 and 1970, respectively (Fig. 3b). Since then, several studies have tried to improve the absorption properties of these chromophores by adding π-electron units. For example, the NDBF (nitrodibenzofuranyl) chromophore (Momotake, Lindegger, Niggli, Barsotti, & Ellis-Davies, 2006) had a large hyperchromic shift, but no bathochromic change (Fig. 3b). Although such nitrobenzyl chromophores are famously versatile and can release many functional groups, the importance of acidic functionalities in biology has led to several groups developing chromophores which work for uncaging molecules with carboxylates, phosphates, or phenols. In this regard, the nitrophenpropyl (NPP) group has been studied by several laboratories. In particular, Pfleiderer and colleagues have studied NPP and derivatives in great detail (Bühler, Lagoja, Giegrich, Stengele, & Pfleiderer, 2004; Hasan et al., 1997). Building on these studies, Goeldner and colleagues applied the NPP uncaging reaction to glutamate (Gug et al., 2008) and GABA (Donato et al., 2012), claiming enormous improvements in the two-photon cross-section when compared to simpler nitroaromatic cages. Importantly, the amino-biphenyl chromophore shows a marked bathochromic shift compared to the less electron-rich oxygen analog (compare the ANBP and ANPP spectra in Fig. 3b). While such chromophores are useful for sequential two-color photolysis, the lack of a minimum for ANBP’s absorbance in the near-UV region prevents it from being used for arbitrarily-ordered two-color uncaging (Fig. 1).

Shortly after his development of the DMNB photochemical protecting group, the Israeli chemist Patchornik introduced another acidic functionality cage in 1976 using a 7-nitroindolinyl (NI) chromophore (Amit, Ben-Efraim, & Patchornik, 1976). Rather neglected until 1999, this photochemistry was revived by Corrie and colleagues with application to glutamate uncaging, providing an important benefit over the important alpha-carboxy-NB chromophore (Wieboldt, Gee, et al., 1994; Wieboldt, Ramesh, Carpenter, & Hess, 1994) in that such caged acids were very stable at physiological pH. In the same year, Niggli and co-workers showed that two-photon uncaging in living cells was possible using the DMNB chromophore (Lipp & Niggli, 1998). Inspired by these two reports, we hypothesized that an electron-rich NI would be effective for two-photon uncaging. Thus, we revealed a year later that this was the case by introducing the 4-methoxy-NI (MNI) group (Matsuzaki, Ellis-Davies, & Kasai, 2000). The absorption spectra of two such caging chromophores, MNI and CDNI (4-carboxymethoxy-5,7-dinitroindolinyl) (Ellis-Davies et al., 2007), are shown in Fig. 3b (structures in Fig. 2), where it can be seen that they absorb light like the DMNB cage. The spectra in Fig. 3b show that there are many caging chromophores available to fill the short wavelength channel required for two-color photolysis (Fig. 1). What about the complementary, longer wavelength chromophore?

Attempts to shift the absorption of nitroaromatic photochemical protecting groups met with modest success, with the best probably being the ANBP cage (Donato et al., 2012). While effective for blue light photolysis, this chromophore works even better in the near-UV range. Thus, organic chemists have developed alternative photochemical protecting groups based on other chromophores. One notable contribution to this field was the 7-diethylaminocoumarin (DEAC) chromophore (Hagen et al., 2001), a violet-blue light absorbing (Fig. 3c) version of the 7-methoxycoumarin cage (Furuta, Torigai, Sugimoto, & Iwamura, 1995). Unfortunately, this chromophore still overlaps significantly with near-UV chromophores (see Fig. 1). A second, completely different red-shifted caging chromophore was introduced by Etchenique in 2003, with the organometallic photochemical protecting group based on the widely-studied ruthenium-bipyridyl (RuBi) molecule (Zayat, Calero, Alborés, Baraldo, & Etchenique, 2003). RuBi absorbs strongly in the blue-green region, but still lacks a real λmin in the near-UV (Fig. 3c). However, two-color uncaging is possible since RuBi-GABA (Rial Verde, Zayat, Etchenique, & Yuste, 2008) undergoes efficient one-photon photolysis at low working concentrations which are insufficient for significant two-photon release. Thus, combining low concentrations of RuBi-GABA for one-photon photolysis with a two-photon sensitive short wavelength caged glutamate enabled two-color, one-photon/two-photon uncaging (Amatrudo, Olson, Agarwal, & Ellis-Davies, 2015; Hayama et al., 2013; Lovett-Barron et al., 2012).

In 2013, we introduced a new caging chromophore called DEAC450 (structure in Fig. 2), which has a λmax in the blue region (450 nm) but, in contrast to RuBi, has a pronounced λmin in the short wavelength region (Olson, Kwon, et al., 2013) (Fig. 3c). This bathochromic shift was mirrored during two-photon excitation, with DEAC450 being about 30x more two-photon active at long wavelengths (900 nm) when compared to short wavelengths (720 nm), allowing clean wavelength-selective two-photon uncaging for the first time (Amatrudo et al., 2014; Olson, Kwon, et al., 2013). Thus, when partnered with caged compounds designed to work at 720 nm (e.g. CDNI, Fig. 2), DEAC450 enabled clean wavelength-selective two-color, two-photon uncaging of glutamate and GABA in brain slices without functional crosstalk (Amatrudo et al., 2015). In our initial report of two-color, two-photon uncaging, we made use of the long wavelength caging chromophore DCAC (Kantevari, Matsuzaki, Kanemoto, Kasai, & Ellis-Davies, 2010). However, significant spectral overlap and slow photolysis only allowed two-color uncaging under restricted conditions, a problem now solved with DEAC450 (Amatrudo et al., 2015). Recently, we further refined the DEAC450 caging chromophore by attaching a polyanionic repetitively branched macromolecule (dendrimer) (Passlick, Kramer, Richers, Williams, & Ellis-Davies, 2017). The dendrimer induced a bathochromic shift of the λmax from 450 to 454 nm (hence called DEAC454) and, more importantly, further reduced the λmin at the shorter wavelength by another 50%. By partnering DEAC454-caged GABA with the short-wavelength probe dcPNPP-Glu (Kantevari et al., 2016), we demonstrated for the first time wavelength-selective two-color, one-photon uncaging of glutamate and GABA without significant functional crosstalk (Passlick et al., 2017). In conclusion, recent developments enabled us to perform wavelength-selective two-color uncaging of glutamate and GABA with one- and two-photon excitation without significant biological crosstalk.

2. Methods

Neurotransmitter uncaging is commonly combined with electrophysiological patch-clamp recordings and has been carried out in diverse types of biological preparations from simple ectopic expression systems in cultured cells to in vivo applications. However, we and others mainly perform neurotransmitter uncaging in acute mouse brain slices, which have the advantage that cells are easily accessible and the external solution can be manipulated while cells remain in a native biological environment. A detailed description of the preparation of acute mouse brain slices and electrophysiological patch-clamp recordings is beyond the scope of this chapter and has been described in detail in numerous publications (Davie et al., 2006; Ting, Daigle, Chen, & Feng, 2014). Here, we will highlight procedures relevant to two-color uncaging.

2.1. Handling of caged compounds

Several properties need to be considered when handling caged compounds, especially light sensitivity, solubility and stability/storage. By definition, light induces photolysis of the caged molecule. Therefore, caution must be taken while handling such probes in ambient white light. This is particularly the case for compounds absorbing longer wavelength light such as RuBi and DEAC450/454 while a bit less so for short wavelength probes like MNI or CDNI due to the wavelength composition of normal fluorescent light. We routinely place Roscolux filters 13 and 25 on our fluorescent lamps and try to minimize exposure of solutions to light from monitors during experiments (reducing the brightness of monitors and covering the recirculating solution with aluminum foil further minimizes exposure).

Most caged compounds described here are fairly soluble in physiological solution. However, stability varies and is particularly dependent on the pH of the solution. MNI-Glu as well as RuBi and DEAC450 caged neurotransmitters are very stable in physiological solution and may be stored frozen for >1 year without significant hydrolysis. This allows preparation and storage of frozen stock solutions or aliquots (see section 2.2). Furthermore, we found that when these caged compounds are bath-applied in a recirculating perfusion system, the perfusion solution containing the caged compounds may be reused for several days of experiments when stored frozen in between experiments. However, solutions should be filtered and the pH confirmed before reuse. Also, osmolarity needs to be checked and if necessary adjusted by adding water when recirculating small volumes due to evaporation over the course of a recording session. CDNI, on the other hand, slowly hydrolyses even when frozen, unless the pH is slightly acidic (pH ~ 4). However, if stored at acidic pH, CDNI is stable for > 2 years and compound may then be recycled by HPLC purification after use (Amatrudo et al., 2015).

For two-color uncaging, the concentration of each compound is another factor that can influence crosstalk. Optical and chemical properties as well as suggested concentrations for one- and two-photon uncaging of commonly used caged glutamate and GABA probes are listed in Table I.

Table I.

Photochemical properties of caged glutamate and GABA compounds.

| Caged compound | ε (M−1 cm−1) | λmax (nm) | QY | Stability | Concentration one-photon | Concentration two-photon |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MNI-Glu | 4,500 | 336 | 0.065(1) | Stable | 1 mM | 5 mM |

| MDNI-Glu | 6,400 | 330 | 0.38* | Slow hydrolysis | 0.2 mM | 2.5 mM |

| CDNI-Glu | 6,400 | 330 | 0.38* | Slow hydrolysis | 0.2 mM | 1 mM |

| CDNI-GABA | 6,400 | 330 | 0.46* | Slow hydrolysis | 0.1–0.2 mM | 0.5–1 mM |

| RuBi-Glu | 5,600 | 450 | 0.13 | Stable | 30 μM | 0.3 mM |

| RuBi-GABA | 6,400 | 424 | 0.2 | Stable | 10 μM | 0.3 mM |

| DEAC450-Glu | 43,000 | 450 | 0.39 | Stable frozen | ND | 0.2–0.6 mM |

| DEAC450-GABA | 43,000 | 450 | 0.39 | Stable frozen | 10–20 μM | 0.2 mM |

| dcPNPP-Glu | 9,900 | 330 | 0.0595 | Stable | 300–330 μM | ND |

| DEAC454-GABA | 43,000 | 454 | 0.23 | Slow hydrolysis | 30 μM | ND |

Notes:

this is the new quantum yield (QY) for MNI-Glu (Corrie, Kaplan, Forbush, Ogden, & Trentham, 2016).

Based on this value, we have revised our published values for the dinitro probes. ND = not determined.

2.2. Aliquoting of caged compounds by vacuum centrifugation/lyophilization

Several caged compounds are quite stable in aqueous solution and may thus be stored as frozen aliquots. However, we prefer to prepare aliquots by means of vacuum centrifugation or lyophilization for long-term storage. This has the advantage that compounds are kept as solids, which significantly increases their long-term stability. This is particularly important and necessary for compounds prone to hydrolysis at basic pH, such as CDNI.

Dissolve batch of caged compound in water or in an appropriate organic solvent such as methanol.

Determine the exact concentration of stock solution by recording an absorption spectrum of that solution and calculating the concentration using the known extinction coefficient for the λmax (see Table I).

optical density at λmax/extinction coefficient = concentration (in M)

Prepare aliquots in centrifuge tubes based on how much compound is desired in the final volume during the experiment.

Evaporate solvent by means of vacuum centrifugation or lyophilization.

Store aliquots at -20°C.

2.3. Application of caged compounds to brain slices

In general, there are two types of application of caged compounds to brain slices: bath-application via a recirculating perfusion system, and local application from a patch pipette. The advantage of bath-application is that it is simple and the concentration of caged compound is constant in the entire preparation. However, this is by far the most expensive mode of application and is not feasible considering the substantial cost of most caged compounds. We were able to reduce the volume of recirculating solution to 6–7 mL. However, care must be taken to keep osmolarity constant over the course of the recording session as we found that evaporation has quite a substantial impact when using such tiny volumes, which is further amplified when working at elevated temperatures. When using a carbonate buffer in the external solution as commonly the case in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF), the solution should be saturated with carbogen (95% O2/5% CO2) before addition of the caged compounds to prevent hydrolysis at a more basic pH. As mentioned before, we found that recirculating solutions of hydrolytically-stable compounds in ACSF may be frozen and reused for several days of experiments if filtered and osmolarity adjusted, which reduces the costs of bath-application.

The other common method is local application from a patch pipette attached to a pressure application system such as the widely used Picospritzer (Parker Instrumentation, Fairfield, NJ, USA). Here, only small volumes of compound are necessary, significantly reducing the cost per experiment. However, a few things should be considered when using local application:

As the name implies, application is quite local and puffing may also depend on the current flow of perfused external solution in the recording chamber. For practicing purposes and to establish the correct settings, it can be useful to test the flow by puffing a fluorescent dye (e.g. fluorescein or Alexa dyes) from the Picospritzer to a brain slice.

Since solution is puffed into normal external solution, it is inevitably diluted. As a rule of thumb, concentration for local application should be double the desired concentration or twice as much as with bath-application.

Since ACSF in the local application pipette cannot be bubbled with carbogen, the local pH might shift upwards. We recommend either using a HEPES-buffered solution with oxygen as pressure source or ACSF with carbogen as pressure source. Furthermore, care should be taken when using the trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) salt of any caged compound, since this might exceed the buffer capacity of ACSF or HEPES solution, especially when high concentrations of caged compound need to be used for two-photon uncaging.

Local application usually employs small diameter pipettes. Therefore, filtration (standard 0.22 μm syringe filters) of the caged compound solution before loading is recommended to prevent clogging of the application pipette.

To increase the area to which the caged compound solution is applied, a custom-made local application system employing larger diameter capillary glass tubing may be used as described by Civillico and colleagues (Civillico, Shoham, O’Connor, Sarkisov, & Wang, 2012). Although this system does require larger volumes and therefore more caged compound per experiment compared to puffing from a patch pipette, it is still significantly more cost-effective compared to bath-application. Furthermore, it enables more consistent application to a wider area, i.e. the entire hippocampal CA1 area of a horizontal mouse brain slice. We also developed a two-channel version of this system allowing the direct comparison of two caged compounds on the same neuron (Passlick & Ellis-Davies, 2018). However, the same precautions as described for local application from a patch pipette should be considered here.

2.4. Hardware and laser alignment for two-color uncaging

Anyone working with high energy one- and two-photon lasers needs to receive full training and follow institutional laser safety rules. Particular care should be taken during laser alignment where potential exposure to high energy laser light is increased.

Two-color uncaging may be carried out as two-photon/one-photon, dual two-photon, or dual one-photon uncaging. For any mode that includes two-photon uncaging or one-photon laser uncaging, a two-galvanometer, two-photon microscope is desired for independent control of the uncaging and imaging lasers. Due to the high resolution of two-photon excitation, perfect alignment of the imaging and uncaging galvanometric scanning mirrors is vital so that the uncaging laser hits the correct location visualized by the imaging laser. Multiple microscope companies now provide two-galvanometer systems with different solutions to aligning the scanning mirrors to each other.

In general, the alignment process requires two steps. First, both lasers need to be adjusted in the beam path on the table so that they enter the scan head and pass through the microscope as straight beams. Second, by using the software, the final precise alignment of both beams is performed. For two-color uncaging, however, we have an additional uncaging laser. Since there are only two galvanometric mirror systems, both uncaging lasers are directed by the same set of mirrors and must therefore be perfectly aligned to each other in the light path before entering the scan head. Precise alignment of both uncaging lasers to each other must then be verified by testing the alignment of each uncaging laser to the imaging laser by using the software alignment procedure.

Two-galvanometer two-photon microscopes for two-color laser uncaging combined with two-photon imaging are expensive and not readily available to every laboratory. In contrast, most institutions have access to epifluorescence or confocal microscopes equipped with LEDs or with one-photon continuous wave lasers used for multi-color fluorescence imaging. For the two-color, one-photon uncaging approach with whole-field illumination which we recently introduced, a simple and inexpensive LED-based system compatible with most normal fluorescence microscopes was used (Passlick et al., 2017). For two-color uncaging of dcPNPP-Glu and DEAC454-GABA, we employed the customizable Multi-LED source system from Thorlabs (NJ, USA) with the following components and adaptions: two LEDs (365 nm and 450 or 470 nm, Thorlabs), each collimated by lenses in a lens tube which is mounted to a cage cube containing a combining long-pass dichroic mirror (387 nm, Chroma, Bellows Falls, VT, USA). Depending on the specific light sources used, notch filters should be placed in the light path for each LED to restrict the wavelength of the transmitted light and further reduce crosstalk (365/20 nm for the 365 nm LED; 455/20 nm for the 450 nm LED, Chroma). Note, the wavelength implied by the name of the LED not necessarily provides the actual λmax for that particular LED. Additionally, the spectrum can be fairly broad which needs to be taken into account for potential crosstalk issues.

The cage cube is mounted to the epifluorescence port of the microscope and the light is directed to the sample by using a long-pass dichroic mirror (here: 488 nm, Semrock, Rochester, NY, USA) in the fluorescence filter turret. The LEDs are controlled independently by an LED driver (LEDD1, Thorlabs) which can also be modulated and triggered by external voltage modulation. Two-color, one-photon uncaging should also be possible with confocal microscopes equipped with UV and blue lasers, which would significantly increase the spatial resolution.

For all modes of two-color uncaging, power should be measured for all light sources (one- and two-photon lasers and/or LEDs) prior to the experiment using a photometer. We use a microscope slide-type photodiode power sensor which can conveniently be placed under the microscope lens (S120C, Thorlabs). The galvanometers should be centered prior to power measurement and the laser should be turned on at least 30 min before measuring the power to allow thermal equilibration of all components.

2.5. Establishing conditions for orthogonal two-color uncaging

Absence of optical crosstalk between two caged compounds when using specific wavelengths of light is the defining key parameter for orthogonal two-color uncaging. Crosstalk, however, can have a different meaning in chemistry or biology. From the chemist’s perspective, one could argue that any absorption inevitably leads to excitation and therefore uncaging so that crosstalk must occur if any spectral overlap is seen (Kotzur et al., 2009). Indeed, even with our newest probe DEAC454, the absorption is not truly zero at the λmin in the UV range, while on the other hand, short wavelength probes like dcPNPP show zero absorption at the longer wavelength (Fig. 4a). Some photolysis is therefore measurable with highly sensitive techniques such as HPLC or NMR when irradiating DEAC454 with UV light. However, these probes are made for two-color uncaging in a biological context, so what is the readout for crosstalk here?

Figure 4.

Two-color, one-photon uncaging of glutamate and GABA. (a) Optical densities of solutions of DEAC454-GABA (blue line) and dcPNPP-Glu (violet line) at working concentrations (here: 30 and 330 μM, respectively). The blue and violet dashed lines are the spectral outputs of the LEDs (here: 365 and 470 nm) used for uncaging. The black and red lines are the microscope filters.

(b) Left, representative current response from a hippocampal CA1 neuron to uncaging of dcPNPP-Glu with UV and blue light. Right, energy dosage/response curve for dcPNPP-Glu uncaging with UV and blue light. Increasing the uncaging duration with the UV LED increased the amplitude of the current response. No current could be elicited even with a high energy dosage of blue light (10 mW, 1000 ms).

(c) Left, representative current response from a hippocampal CA1 neuron to uncaging of DEAC454-GABA with UV and blue light. Right, energy dosage/response curve for DEAC454-GABA uncaging with UV and blue light. Increasing the uncaging duration with the blue LED increased the amplitude of the current response while only small currents could be elicited when using high energy dosages of UV light.

(d) The dcPNPP chromophore does not absorb blue light, so no biological actuation is possible with longer wavelengths used for optimal DEAC454 excitation. Thus, there is an “infinite power domain” for photolysis of DEAC454-GABA with such wavelengths (blue shading).

(e) Determination of the power domain for two-color, one-photon uncaging of DEAC454-GABA with zero biological crosstalk. As a result of the small absorbance of DEAC454 in the UV range, no biological crosstalk was detectable with UV light below 5 mW and 6 ms (pink shading). However, using such energies, dcPNPP-Glu was readily uncaged and elicited robust currents. At increased energy dosage, the power window was still >30x for the two caged compounds using UV light (grey shading).

The decisive factor for biological crosstalk is whether a certain energy dosage (uncaging power * duration) of UV light induces a functional response in the cell. This does not only depend on the quantitative measure of how much compound is photolyzed but whether the receptor to be studied is sufficiently activated by this amount to evoke a response. Even with the same caged probes and light sources, the crosstalk may be different when studying for example ionotropic vs. metabotropic receptors due their different sensitivity and since the response of the latter may be amplified by downstream signaling cascades (see Passlick et al., 2017). For each set of caged compounds, combination of wavelengths, and pair of receptors to be studied, the optical crosstalk should therefore be determined.

To measure optical crosstalk in biological systems, the general idea is to record energy dosage/response curves for both compounds separately with both wavelengths of light used (Fig. 4). The readout and detection limit are the critical factors here to be able to determine the conditions where two-color uncaging is possible without functional crosstalk. Therefore, conditions for determining the crosstalk might be different from the actual final experiment since the signals to be studied might not be readily detectable under those conditions. For example, when using physiological ion concentrations extracellularly and intracellularly, uncaging of GABA likely does not induce a detectable current since the reversal potential for chloride ions is close to the resting membrane potential of the cell. Therefore, despite opening of the GABA-A receptor and increasing the chloride conductivity of the cell by GABA uncaging, no net current might be measurable. To be able to determine the crosstalk of GABA uncaging with two wavelengths of light, experimental conditions need to be established where the detection limit is increased such that even small amounts of photolyzed GABA become detectable. To this end, in our two-color, one-photon uncaging approach, we must manipulate the extracellular and intracellular ion concentrations to increase the driving force for chloride ions. Further, we must optimize our recording conditions so that even small currents (here, >5 pA) may be measured. By doing so, we demonstrated that there was no functional biological crosstalk of GABA uncaging when using UV light energy dosages that elicited large AMPA-receptor mediated currents when dcPNPP-Glu was present (Fig. 4 and Passlick et al., 2017). Therefore, although the crosstalk may not be absolute zero in the chemical preparation (chemical crosstalk), it is functionally zero in the biological application (biological crosstalk) which demonstrates that caged GABA remains orthogonal in biological systems in which dcPNPP-Glu is being used.

Next, we describe the detailed procedure for determining the optical crosstalk for two-color, one-photon uncaging of dcPNPP-Glu and DEAC454-GABA to activate AMPA and GABA-A receptors, respectively. However, the same basic procedure also applies to other modes of two-color uncaging.

2.5.1. Extracellular solution

ACSF (in mM):

125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 26 NaHCO3, 10 glucose, 3 Na-pyruvate, 1.3 Na-ascorbate equilibrated with 95% O2/ 5% CO2.

Note: We and others include ascorbate and pyruvate in our ACSF, which are beneficial for cellular health during imaging and uncaging experiments.

For these recordings we include the following blockers and antagonists to look at pure AMPA and GABA-A receptor responses: tetrodotoxin (TTX, 1 μM) to prevent firing of action potentials, DL-AP5 (100 μM) to block NMDA receptors, CGP-55845 (3 μM) to block GABA-B receptors, and JNJ-16259685 (1 μM), MPEP (3 μM) and LY341495 (30 nM) to block metabotropic glutamate receptors.

2.5.2. Intracellular patch-clamp solutions

K-gluconate (in mM):

135 K-gluconate, 4 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 5 ethylene glycol-bis(β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (EGTA), 4 Na2-ATP, 0.4 Na2-GTP, 10 Na2 phosphocreatine, pH adjusted to 7.35.

Note: In combination with the above ACSF solution (section 2.5.1), the calculated AMPA receptor reversal potential is -1 mV. When neurons are clamped at -60 mV, the strong ionic driving force enables detection of small amounts of free glutamate from dcPNPP-Glu uncaging.

Cs-methanesulfonate (in mM):

135 Cs-methanesulfonate, 4 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 5 EGTA, 4 Na2-ATP, 0.4 Na2-GTP, 10 Na2 phosphocreatine, pH adjusted to 7.35.

Note: In combination with the above ACSF solution (section 2.5.1), the calculated GABA-A receptor reversal potential is -71 mV. When neurons are clamped at +10 mV, the strong ionic driving force enables detection of small amounts of free GABA by DEAC454-GABA uncaging.

2.5.3. Protocol for recording the optical crosstalk for two-color, one-photon uncaging

This protocol describes the steps to determine the power window where two-color, one-photon whole-field (LED) uncaging of dcPNPP-Glu and DEAC454-GABA can be performed with zero functional crosstalk. We commonly perform these experiments by recording patch-clamp whole-cell currents from hippocampal neurons of acute mouse brain slices. However, the approach can easily be adapted to other preparations, caged compounds, or light sources.

Details on the hardware used here are given in section 2.4 (see also Passlick et al., 2017).

Calibrate the output power of the UV (365 nm) and blue LED (470 nm) and determine settings for different power levels, e.g. for 5 and 10 mW. If experiments will be performed on different microscopes, it may be useful to describe the power in mW/cm2 for comparison.

Prepare mouse brain slices by standard protocols (Davie et al., 2006; Ting et al., 2014) (or other preparations such as cultured cells if preferred).

Dissolve 330 μM dcPNPP-Glu in carbogenated ACSF (including blockers; see 2.5.1), and recirculate the solution through the recording chamber.

Patch a cell with K-gluconate internal solution (see 2.5.2) in the whole-cell configuration, and hold it in the voltage-clamp mode at -60 mV.

Switch the light path at the microscope to uncaging.

Record an energy dosage/response curve for both LEDs: Either set the power of the LED to a fixed value and increase the uncaging duration, or set a fixed duration and increase the power of the LED while simultaneously recording the current response of the cell. We commonly record two eight-point power dosage/response curves with fixed power (5 and 10 mW) by increasing the uncaging duration (0/2/4/6/8/10/15/20 ms for both LEDs), respectively (Fig. 4b). Record these curves with both LEDs for the same cell and record at least three individual cells.

- Perform the same type of experiment for DEAC454-GABA with the following modifications:

- Dissolve 30 μM DEAC454-GABA in carbogenated ACSF (including blockers; see 2.5.1) and recirculate the solution through the recording chamber.

- Patch a cell with Cs-methanesulfonate internal solution (see 2.5.2) in the whole-cell configuration and hold it in the voltage-clamp mode at +10 mV.

- Record energy dosage/response curves for both LEDs as described under point 6 (Fig. 4c).

2.5.4. Analysis of data and determination of power window with zero functional crosstalk

Measure the cellular current response to all stimuli from both LEDs for each cell separately and calculate the average current response for each stimulus.

Plot the measured cellular current response to dcPNPP-Glu and DEAC454-GABA uncaging against energy dosage (uncaging duration/power) with the blue LED (Fig. 4d) and the UV LED (Fig. 4e).

Determine the power window where no current is detectable from dcPNPP-Glu uncaging with blue light (Fig. 4d; infinite here since dcPNPP does not absorb any blue light) and DEAC454-GABA uncaging with UV light (Fig. 4e; finite since DEAC454 does absorb some UV light). This is the energy dosage range considered as zero functional crosstalk and should thus be used during the final experiment.

3. Examples of two-color uncaging

Glutamate and GABA are the most important neurotransmitters mediating excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission in the central nervous system, respectively. The balance between these two opposing signals is crucial for normal signal processing in the brain and its malfunction has been determined to be a central cause of several neurological diseases (Tatti, Haley, Swanson, Tselha, & Maffei, 2017). Two-color uncaging of glutamate and GABA depicts an ideal way to study the interaction between excitation and inhibition, as both signals can be activated quickly and independently by means of light. Recent developments described above have provided neuroscientists with the technology to perform different modes of two-color actuation. Here, we describe some examples from the literature utilizing these optical tools.

In 2012, Losonczy and colleagues demonstrated the first example of two-color, one-photon/two-photon uncaging of glutamate and GABA in acute brain slices (Lovett-Barron et al., 2012). By making use of the efficient one-photon uncaging of RuBi-GABA at very low concentrations and combining it with a two-photon sensitive short wavelength caged glutamate probe, they were able to selectively stimulate glutamatergic and GABAergic signaling on hippocampal pyramidal neurons. As a result, they showed that inhibition is more effective in dampening dendritic excitation when colocalized with the excitation compared to inhibition placed at the soma (Lovett-Barron et al., 2012). This was the first experimental test of the so far theoretical assumption that local dendritic inhibition is more potent than somatic inhibition. In a similar experiment, we showed that two-photon uncaging of CDNI-Glu at multiple spines combined with one-photon uncaging of DEAC450-GABA on that dendrite reduced the threshold for generation of a dendritic spike (Amatrudo et al., 2015).

In another study, it was shown that two-photon uncaging of CDNI-GABA or optogenetic activation of interneurons targeting spines reduced the Ca2+ transient of backpropagating action potentials in the targeted spine (Chiu et al., 2013). By performing two-color, one-photon/two-photon uncaging of RuBi-GABA and CDNI-Glu at single spines, they further revealed that inhibition of synaptic excitation at single spines was highly compartmentalized and did not spread to neighboring spines (Fig. 5) (Chiu et al., 2013).

Figure 5.

Two-color, two-photon/one-photon uncaging of CDNI-Glu and RuBi-GABA. (a) Optical densities of solutions of RuBi-GABA (blue line) and CDNI-Glu (violet line) at the working concentrations (10.8 μM and 1 mM, respectively). Note that the very low concentration of RuBi-GABA necessary for efficient one-photon uncaging prevents sufficient two-photon uncaging of GABA at 720 nm used for CDNI-Glu uncaging.

(b) CDNI-Glu and RuBi-GABA were applied simultaneously to a patch-clamped dye-filled layer 2/3 neuron of the prefrontal cortex in a brain slice. Two-photon uncaging of CDNI-Glu (arrowheads) and one-photon uncaging of RuBi-GABA (asterisk) were performed at three individual dendritic spines. Scale bar, 1 μm.

(c) Two-photon glutamate uncaging evoked an increase in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration (ΔCa2+) optically measured at each spine (as indicated in (b)) and an excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP) measured by the patch-electrode at the soma (black traces). When combined with one-photon GABA uncaging (red traces), the Ca2+ increase and depolarization were reduced in spine 1, while 2 and 3 were unaffected, indicating compartmentalization of inhibition in spine 1. Scale bars, 4% ΔG/Gsat, 50 ms (top) or 0.1 mV, 5 ms (bottom).

(d) Average effect of two-color uncaging of glutamate and GABA on glutamate-evoked Ca2+ and voltage transients showing GABA-induced inhibition. Scale bars, 2% ΔG/Gsat, 50 ms (left) or 0.1 mV, 10 ms (right).

(e) Summary bar graph showing significant effect of two-color glutamate/GABA uncaging (red) on amplitude and duration of glutamate uncaging-evoked EPSPs (black; paired Student’s t-test).

Adapted from Chiu et al., 2013, by permission of the AAAS.

With the same set of caged compounds, the Kasai laboratory demonstrated that spine long-term depression (LTD) was facilitated by GABA uncaging (Hayama et al., 2013). First, they used two-photon glutamate uncaging combined with electrophysiology to induce spike-timing-dependent plasticity at single spines. Interestingly, they found that while long-term potentiation (LTP) was readily induced by uncaging followed by action potential firing (pre-before-post), LTD (post-before-pre) was only induced if paired with GABA uncaging within 50 ms of the action potential. Moreover, although only a single spine was stimulated by glutamate uncaging, LTD spread to neighboring spines, a property that was not observed for LTP (Hayama et al., 2013).

In 2010, we presented the first example of two-color, two-photon uncaging of glutamate and GABA in brain slices (Kantevari et al., 2010). While bidirectional modification of neuronal excitability was feasible, color separation was not ideal due to significant absorption of the long wavelength caging chromophore DCAC at the short wavelength (DCAC is a water-soluble dicarboxylated version of the DEAC chromophore, Fig. 3c, light blue curve). Furthermore, its comparatively slow release of GABA led to rather slow GABA currents. With the development of the caging chromophore DEAC450 (Amatrudo et al., 2014; Olson, Banghart, Sabatini, & Ellis-Davies, 2013; Olson, Kwon, et al., 2013), which absorbs longer wavelength light and exhibits a distinct minimum at shorter wavelength, we are now able to perform orthogonal two-color, two-photon uncaging (Amatrudo et al., 2015). With CDNI-Glu and DEAC450-GABA present in same preparation, 720 and 900 nm light selectively induced glutamatergic and GABAergic currents, respectively (Fig. 6a,b). Thus, action potentials evoked by two-photon glutamate uncaging along a basal dendrite of a hippocampal CA1 neuron could be blocked when preceded by two-photon GABA uncaging at the soma to bidirectionally modify neuronal excitability (Fig. 6c).

Figure 6.

Two-color, two-photon uncaging of CDNI-Glu and DEAC450-GABA. (a) Optical densities of solutions of G5-DEAC450-GABA (blue line) and CDNI-Glu (violet line) at the working concentrations (0.6 and 1 mM, respectively).

(b) Left, two-photon uncaging of CDNI-Glu (1.2 mM) at a single spine of a hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neuron (holding potential -60 mV). Uncaging at 720 nm elicited a glutamatergic current, while uncaging at 900 nm did not elicit any response. CDNI does not absorb light at this wavelength. Right, after addition of G5-DEAC450-GABA (0.9 mM), uncaging at the primary apical dendrite of another cell (holding potential +10 mV) elicited a robust GABAergic current at 900 nm. Irradiation with the same energy at 720 nm used for CDNI-Glu produced no detectable current. This lack of functional crosstalk using two-photon excitation is analogous to that seen in Fig. 4e for one-photon excitation.

(c) Left, two-photon fluorescence image of a dye-filled CA1 hippocampal pyramidal neuron with locations of uncaging indicated. Right (from left to right), in the presence of CDNI-Glu (1 mM) and G5-DEAC450-GABA (0.6 mM), two-photon uncaging with 720 nm irradiation at 10 points along a basal dendrite (left, red) evoked an action potential. Uncaging with 900 nm at 3 points at the soma (left, black) of the same cell did not induce any change in the membrane potential at -60 mV, since it is close to the reversal potential for chloride. When the excitatory stimulus (720 nm) is preceded by the inhibitory (900 nm), the action potential is reversibly blocked. When the cell is set to a more depolarized potential (-50 mV), the underlying GABA-induced hyperpolarization becomes visible.

The most challenging of all configurations is two-color uncaging with one-photon excitation in both optical channels. Here, lack of absorption of the long wavelength chromophore in the short wavelength region is vital. In 2012, a report demonstrated two-color, one-photon uncaging of glutamate and GABA (Stanton-Humphreys et al., 2012). However, to achieve color-separation, very short 250–260 nm light was used for one chromophore, which is not compatible with most microscope objectives and exhibits an increased risk of phototoxicity due to its high energy. Furthermore, the evoked glutamatergic and GABAergic currents were very slow, limiting its applicability to studying the underlying fast neurotransmission (Stanton-Humphreys et al., 2012). Recently, we developed the caged compound DEAC454-GABA (Passlick et al., 2017) which has a further improved λ min-to-max ratio compared to DEAC450-GABA. When combined with the caged compound dcPNPP-Glu (Kantevari et al., 2016), we were able to perform orthogonal two-color, one-photon uncaging over a wide range of light energy dosages without functional crosstalk. We showed that wavelength-selective activation is feasible with neurons from two different brain areas in acute mouse brain slices. Furthermore, we established conditions for ionotropic as well as metabotropic receptors activated by glutamate and GABA. We were thus able to fire action potentials by glutamate uncaging and block them by co-activation of GABA-A receptors in an arbitrary order (Fig. 7) and bidirectionally modulate the spontaneous spiking in dopaminergic neurons (Passlick et al., 2017).

Figure 7.

Two-color, one-photon uncaging of dcPNPP-Glu and DEAC454-GABA. (a) dcPNPP-Glu and DEAC454-GABA were applied simultaneously to a hippocampal brain slice at the same concentrations as used individually in Fig. 4. Irradiation with 365 nm light (5 mW, 6 ms) evoked single action potentials. Preceding this stimulus with 470 nm light irradiation (10 mW, 1 ms) reversibly blocked the action potential. The 470 nm light stimulus alone did not evoke a detectable change in membrane potential (shunting inhibition).

(b) 365 nm light irradiation (5 mW, 4 ms) at 1 Hz evoked multiple action potentials (left). Preceding the 2nd and 4th stimulus with 470 nm light irradiation (10 mW, 12 ms) reversibly blocked the action potentials selectively on these stimuli (middle). Removal of the blue flashes restored reliable action potential responses (right).

From Passlick et al., 2017.

Uncaging may also be combined with optogenetic approaches in a wavelength-selective, two-color fashion. Since short wavelength caged compounds are not sensitive to blue light used for channelrhodopsin activation and the channel density and conductance of channelrhodopsins are typically too low for sufficient two-photon excitation with pulses used for two-photon uncaging, two-color, one-photon/two-photon actuation is feasible. By combining single spine two-photon uncaging of MNI-Glu with postsynaptic depolarization of the same neuron with ChR2, Oertner and coworkers were able to induce LTP at single spines (Zhang, Holbro, & Oertner, 2008). This all-optical approach of spike-timing-dependent plasticity enabled them to detect that CaMKII selectively accumulated at the stimulated spine (Zhang et al., 2008). In another study, two-photon uncaging of CDNI-Glu at single spines of medium spiny neurons was combined with optogenetic release of dopamine from axons targeting the same cells. By varying the timing of dopamine release in relation to single spine LTP induced by two-photon uncaging, they were able to isolate the timing window in which dopamine is able to enhance LTP of individual spines, which might reflect reinforced behavior at the single synapse level (Yagishita et al., 2014). Thus, combining optogenetic approaches and neurotransmitter uncaging have led to new insights into neuronal function due to the orthogonal nature of two-color actuation using these approaches.

4. Summary and conclusion

Recent developments have provided us with the tools to perform multi-color actuation of cell function. By refining the absorption of caging chromophores and defining conditions to prevent optical crosstalk in the biological application, chemists and biologists have established conditions for orthogonal two-color uncaging. This enabled physiologists to study the interaction of glutamatergic and GABAergic signals in living cells. Future developments should include the design and synthesis of new probes caging diverse signaling molecules beyond glutamate and GABA, which will provide new insights into the underlying signaling pathways in health and disease.

Acknowledgements.

This work was supported by the NIH (USA) grants GM053395 and NS069720 to GCRED and a Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Research Fellowship (DFG, Germany) to SP.

References

- Amatrudo JM, Olson JP, Agarwal HK, & Ellis-Davies GCR (2015). Caged compounds for multichromic optical interrogation of neural systems. The European Journal of Neuroscience, 41(1), 5–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amatrudo JM, Olson JP, Lur G, Chiu CQ, Higley MJ, & Ellis-Davies GCR (2014). Wavelength-Selective One- and Two-Photon Uncaging of GABA. ACS Chemical Neuroscience, 5(1), 64–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amit B, Ben-Efraim DA, & Patchornik A (1976). Light-sensitive amides. The photosolvolysis of substituted 1-acyl-7-nitroindolines. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 98(3), 843–844. [Google Scholar]

- Barany G, & Merrifield RB (1977). A new amino protecting group removable by reduction. Chemistry of the dithiasuccinoyl (Dts) function. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 99(22), 7363–7365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barltrop JA, Plant PJ, & Schofield P (1966). Photosensitive protective groups. Chemical Communications (London), 0(22), 822–823. [Google Scholar]

- Bühler S, Lagoja I, Giegrich H, Stengele K-P, & Pfleiderer W (2004). New Types of Very Efficient Photolabile Protecting Groups Based upon the [2-(2-Nitrophenyl)propoxy]carbonyl (NPPOC) Moiety. Helvetica Chimica Acta, 87(3), 620–659. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu CQ, Lur G, Morse TM, Carnevale NT, Ellis-Davies GCR, & Higley MJ (2013). Compartmentalization of GABAergic inhibition by dendritic spines. Science, 340(6133), 759–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Civillico EF, Shoham S, O’Connor DH, Sarkisov DV, & Wang SS-H (2012). Preparing, handling, and applying caged compound solutions for acousto-optical deflector-based patterned uncaging with ultraviolet light. Cold Spring Harbor Protocols, 2012(8). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrie JET, Kaplan JH, Forbush B, Ogden DC, & Trentham DR (2016). Photolysis quantum yield measurements in the near-UV; a critical analysis of 1-(2-nitrophenyl)ethyl photochemistry. Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences: Official Journal of the European Photochemistry Association and the European Society for Photobiology, 15(5), 604–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davie JT, Kole MHP, Letzkus JJ, Rancz EA, Spruston N, Stuart GJ, & Häusser M (2006). Dendritic patch-clamp recording. Nature Protocols, 1(3), 1235–1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donato L, Mourot A, Davenport CM, Herbivo C, Warther D, Léonard J, … Specht A (2012). Water-soluble, donor-acceptor biphenyl derivatives in the 2-(o-nitrophenyl)propyl series: highly efficient two-photon uncaging of the neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid at λ = 800 nm. Angewandte Chemie (International Ed. in English), 51(8), 1840–1843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis-Davies GCR (2007). Caged compounds: photorelease technology for control of cellular chemistry and physiology. Nature Methods, 4(8), 619–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis-Davies GCR, Matsuzaki M, Paukert M, Kasai H, & Bergles DE (2007). 4-Carboxymethoxy-5,7-dinitroindolinyl-Glu: an improved caged glutamate for expeditious ultraviolet and two-photon photolysis in brain slices. The Journal of Neuroscience, 27(25), 6601–6604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedoryak OD, Sul J-Y, Haydon PG, & Ellis-Davies GCR (2005). Synthesis of a caged glutamate for efficient one- and two-photon photorelease on living cells. Chemical Communications, 0(29), 3664–3666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuta T, Torigai H, Sugimoto M, & Iwamura M (1995). Photochemical Properties of New Photolabile cAMP Derivatives in a Physiological Saline Solution. The Journal of Organic Chemistry, 60(13), 3953–3956. [Google Scholar]

- Gug S, Charon S, Specht A, Alarcon K, Ogden D, Zietz B, … Goeldner M (2008). Photolabile glutamate protecting group with high one- and two-photon uncaging efficiencies. Chembiochem: A European Journal of Chemical Biology, 9(8), 1303–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen V, Bendig J, Frings S, Eckardt T, Helm S, Reuter D, & Kaupp UB (2001). Highly Efficient and Ultrafast Phototriggers for cAMP and cGMP by Using Long-Wavelength UV/Vis-Activation. Angewandte Chemie (International Ed. in English), 40(6), 1045–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan A, Stengele K-P, Giegrich H, Cornwell P, Isham KR, Sachleben RA, … Foote RS (1997). Photolabile protecting groups for nucleosides: Synthesis and photodeprotection rates. Tetrahedron, 53(12), 4247–4264. [Google Scholar]

- Hayama T, Noguchi J, Watanabe S, Takahashi N, Hayashi-Takagi A, Ellis-Davies GCR, … Kasai H (2013). GABA promotes the competitive selection of dendritic spines by controlling local Ca2+ signaling. Nature Neuroscience, 16(10), 1409–1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantevari S, Matsuzaki M, Kanemoto Y, Kasai H, & Ellis-Davies GCR (2010). Two-color, two-photon uncaging of glutamate and GABA. Nature Methods, 7(2), 123–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantevari S, Passlick S, Kwon H-B, Richers MT, Sabatini BL, & Ellis-Davies GCR (2016). Development of Anionically Decorated Caged Neurotransmitters: In Vitro Comparison of 7-Nitroindolinyl- and 2-(p-Phenyl-o-nitrophenyl)propyl-Based Photochemical Probes. Chembiochem: A European Journal of Chemical Biology, 17(10), 953–961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan JH, Forbush B, & Hoffman JF (1978). Rapid photolytic release of adenosine 5’-triphosphate from a protected analogue: utilization by the Na:K pump of human red blood cell ghosts. Biochemistry, 17(10), 1929–1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klapoetke NC, Murata Y, Kim SS, Pulver SR, Birdsey-Benson A, Cho YK, … Boyden ES (2014). Independent optical excitation of distinct neural populations. Nature Methods, 11(3), 338–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotzur N, Briand B, Beyermann M, & Hagen V (2009). Wavelength-selective photoactivatable protecting groups for thiols. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 131(46), 16927–16931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipp P, & Niggli E (1998). Fundamental calcium release events revealed by two-photon excitation photolysis of caged calcium in Guinea-pig cardiac myocytes. The Journal of Physiology, 508(3), 801–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovett-Barron M, Turi GF, Kaifosh P, Lee PH, Bolze F, Sun X-H, … Losonczy A (2012). Regulation of neuronal input transformations by tunable dendritic inhibition. Nature Neuroscience, 15(3), 423–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki M, Ellis-Davies GCR & Kasai H (2000). Two-photon uncaging of glutamate reveals AMPA receptors density expression at single spine heads. Society for Neuroscience Annual Conference 2000, 426.12 [Google Scholar]

- Momotake A, Lindegger N, Niggli E, Barsotti RJ, & Ellis-Davies GCR (2006). The nitrodibenzofuran chromophore: a new caging group for ultra-efficient photolysis in living cells. Nature Methods, 3(1), 35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson JP, Banghart MR, Sabatini BL, & Ellis-Davies GCR (2013). Spectral Evolution of a Photochemical Protecting Group for Orthogonal Two-Color Uncaging with Visible Light. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 135(42), 15948–15954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson JP, Kwon H-B, Takasaki KT, Chiu CQ, Higley MJ, Sabatini BL, & Ellis-Davies GCR (2013). Optically selective two-photon uncaging of glutamate at 900 nm. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 135(16), 5954–5957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passlick S, & Ellis-Davies GCR (2018). Comparative one- and two-photon uncaging of MNI-glutamate and MNI-kainate on hippocampal CA1 neurons. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 293, 321–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passlick S, Kramer PF, Richers MT, Williams JT, & Ellis-Davies GCR (2017). Two-color, one-photon uncaging of glutamate and GABA. PloS One, 12(11), e0187732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patchornik A, Amit B, & Woodward RB (1970). Photosensitive protecting groups. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 92(21), 6333–6335. [Google Scholar]

- Rial Verde EM, Zayat L, Etchenique R, & Yuste R (2008). Photorelease of GABA with Visible Light Using an Inorganic Caging Group. Frontiers in Neural Circuits, 2, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton-Humphreys MN, Taylor RDT, McDougall C, Hart ML, Brown CTA, Emptage NJ, & Conway SJ (2012). Wavelength-orthogonal photolysis of neurotransmitters in vitro. Chemical Communications, 48(5), 657–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatti R, Haley MS, Swanson OK, Tselha T, & Maffei A (2017). Neurophysiology and Regulation of the Balance Between Excitation and Inhibition in Neocortical Circuits. Biological Psychiatry, 81(10), 821–831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ting JT, Daigle TL, Chen Q, & Feng G (2014). Acute brain slice methods for adult and aging animals: application of targeted patch clamp analysis and optogenetics. Methods in Molecular Biology, 1183, 221–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieboldt R, Gee KR, Niu L, Ramesh D, Carpenter BK, & Hess GP (1994). Photolabile precursors of glutamate: synthesis, photochemical properties, and activation of glutamate receptors on a microsecond time scale. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 91(19), 8752–8756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieboldt R, Ramesh D, Carpenter BK, & Hess GP (1994). Synthesis and photochemistry of photolabile derivatives of gamma-aminobutyric acid for chemical kinetic investigations of the gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor in the millisecond time region. Biochemistry, 33(6), 1526–1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagishita S, Hayashi-Takagi A, Ellis-Davies GCR, Urakubo H, Ishii S, & Kasai H (2014). A critical time window for dopamine actions on the structural plasticity of dendritic spines. Science, 345(6204), 1616–1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zayat L, Calero C, Alborés P, Baraldo L, & Etchenique R (2003). A new strategy for neurochemical photodelivery: metal-ligand heterolytic cleavage. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 125(4), 882–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y-P, Holbro N, & Oertner TG (2008). Optical induction of plasticity at single synapses reveals input-specific accumulation of alphaCaMKII. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 105(33), 12039–12044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]