Abstract

Domain-specific control beliefs typically buffer the influence stressors have on people’s negative affect (affective stressor reactivity). However, little is known about the extent to which individuals’ control beliefs vary across stressor types and whether such stressor-related control diversity is adaptive for affective well-being. We thus introduce a control diversity construct (a person-level summary of across-domain control beliefs) and examine how control diversity differs with age and relates to negative affect and affective stressor reactivity. We apply a multilevel model to daily diary data from the National Survey of Daily Experiences (NSDE, N = 2,022; mean age = 56 years; 33–84; 57% women). Our findings indicate that above and beyond average control beliefs, people whose control is spread over fewer stressor domains (less control diversity) have lower negative affect and less affective stressor reactivity. Older adults are more likely than younger adults to have their control beliefs concentrated in one domain. Additionally, associations between control diversity and negative affect and affective stressor reactivity were age invariant. Moderation effects indicated that when people with low average control beliefs are faced with stressors, having control beliefs focused on fewer domains rather than spread broadly across many domains is associated with less negative affect. Our findings suggest that control diversity provides unique insights into how control beliefs differ across adulthood and contribute to affective well-being.

Keywords: control beliefs, control diversity, stress, entropy, negative affect, intraindividual variability

Lifespan psychologists highlight the importance of general control beliefs for successful aging (Rodin, 1986; Rowe & Kahn, 1997; Ryff & Singer, 1998). For example, general control beliefs buffer how stressors are coupled with negative affect (affective stressor reactivity; Koffer et al., 2017; Neupert, Almeida, & Charles, 2007; Ong, Bergeman, & Bisconti, 2005). It is also known that people’s perceived control varies across work, family and health life domains, and such across-domain variation differs between people and over time (Lachman, 1986). However, little is known about how individuals’ daily control beliefs vary across life domains. The extent of spread may be particularly relevant to daily stressors. To illustrate, one person might perceive high control over a work stressor, but little control over a social life stressor. In contrast, another person might perceive little control consistently over many key stressors of daily life. This paper introduces the concept of control diversity, investigates how peoples’ control beliefs vary across multiple domains, examines whether having control resources focused more narrowly or spread more broadly across domains differs by age, and explores whether control diversity is adaptive or maladaptive by studying associations with negative affect and affective stressor reactivity and how these are moderated by age. To examine these questions about the nature and correlates of dispersion of control beliefs across domains, we make use of daily diary data from the National Survey of Daily Experiences (NSDE, N = 2,022; mean age = 56 years; 33–84; 57% women).

Lifespan Control Beliefs: General, Daily, and Domain-Specific

Individuals’ perceived control over life and circumstances reflects subjective beliefs about their ability to apply effective coping strategies (Lachman & Weaver, 1998a; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Levenson, 1981; Skinner, 1996). Control beliefs are known to be protective against physical health decrements, cognitive decline, and are associated with lower mortality risk (Aldwin et al., 1996; Bandura, 1987; Levenson, 1974; Skinner, 1996; Baltes & Baltes, 1986; Lachman, 1986; Rodin, 1986; Schindler & Staudinger, 2008). High control beliefs serve to motivate the individual to use coping strategies in the face of stressors, thereby increasing the likelihood of effectively buffering the impact of stressors on negative affect and overall well-being (Bandura, 1997; Heckhausen, Wrosch, & Schulz, 2010; Lachman, Neupert, & Agrigoroaei, 2011; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). General (trait) control beliefs reflect individuals’ perception that they have the resources and ability needed to face life’s demands and obtain desired outcomes (Bandura, 1997; Skinner, 1996). Adding proximal information to these general control beliefs, more situational (e.g., daily) control beliefs pertain to whether individuals have the resources and ability to cope with challenges and reach desired outcomes in specific situations. When situational (e.g., daily) control beliefs are high, individuals supplement their general control beliefs with more specific perceptions about whether they can successfully face a particular situation. Daily control beliefs reflect an aggregate of the situational sense of control from a particular day. Both general and daily control beliefs support the adoption of health-promoting behaviors (Lachman & Firth, 2004), buffer the physiological reactivity to stressors (Kunz-Ebrecht et al., 2004), down-regulate negative emotions (Hay & Diehl, 2010), and mobilize social support in times of need (Antonucci, 2001).

Control beliefs are often examined in domain-generalized ways by asking people how much control they perceive over their lives. Conceptual considerations and empirical reports, however, have noted that control beliefs are multidimensional and changes in domain-specific control beliefs may be multidirectional. Control beliefs vary by area of life considered (Levenson, 1974) and age group studied (Lachman, 1986; Lachman & Weaver, 1998). That is, individuals may feel in control of some domains of life (e.g., work) but not others (e.g., family). Conceptually, individuals’ perceived control differs across domains because the actual controllability of outcomes varies across domains of life and/or because individuals perceive challenges as differing across domains (Lachman, Neupert, & Agrigoroaei, 2012). To illustrate, a person may perceive no control over the health status of a spouse who suffers from an untreatable chronic illness, but may still perceive high control over the daily demands of work. Age-related shifts in available or perceived resources lead to a scenario in which such domain differences in control beliefs also vary by age.

Indeed, empirical evidence suggests domain-specific control beliefs may differ by age. For example, Lachman and Weaver (1998) found that older adults reported more control over work, finances, and marriage than middle-aged and younger adults, but less control over social relationships with children and sex life. Similarly, examining long-term changes in particular control domains over a 3-year period, McAvay, Seeman, and Rodin (1996) identified domains relevant to older adults (e.g., transportation, safety, health) and showed that age-related declines in control over financial, safety, and productivity domains were steeper than changes in control over transportation and friendship domains. In sum, control potential is preserved for some areas of life (e.g., friendship), whereas the control potential over functioning and development in other domains (e.g., health) declines. In this paper, we extend previous work on daily and domain specific control beliefs (Lachman, 1986; Lachman, Neupert, & Agrigoroaei, 2012; Lachman & Weaver, 1998) by introducing the concept of control diversity – an index of each person’s across-domain distribution of control beliefs over the study period.

Control Diversity: Advancing Quantification of Cross-Domain Control Beliefs

The above studies were based on cross-sectional data (Lachman & Weaver, 1998) and macro-longitudinal data (McAvay et al., 1996) and thus do not capture how control beliefs vary across domains in adults’ everyday lives. Drawing on evidence that control beliefs vary week-to-week (Drewelies et al., 2018; Eizenman et al., 1997) and across domains of life (Lefcourt, 1984), we consider the within-person distribution of domain-specific control beliefs, an approach that has not previously been pursued. Specifically, we advance the notion of control diversity as the extent to which control differs across multiple domains of life. In doing so, we highlight the importance of considering how control beliefs differ from domain to domain in a multivariate manner rather than examining each domain individually. This is important, because it is the first study to provide understanding of the context of control beliefs within any one domain: whether experiences manifest equally across domains over the study period. In doing so, we can move beyond traditional measures that have quantified levels of control beliefs to quantifying relative experiences of control. Subsequently, our theoretical understanding of how levels of control relate to adaptive outcomes should also account for the relative distribution of control.

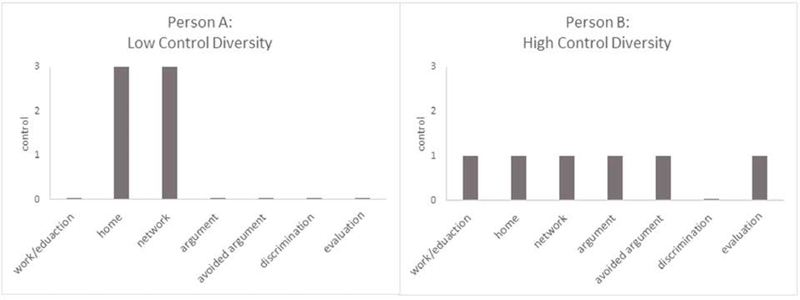

Control diversity is a person-level summary of within-person variability in control beliefs across stressor domains throughout a given study period (Benson, Ram, Almeida, Zautra, & Ong, 2017; Kliegel & Sliwinski, 2004, Nesselroade, 2001). Some people have their control beliefs spread across many domains over time, whereas others have their control beliefs focused in a few domains. Specifically, we adapt Shannon’s (1948) entropy, a widely used index of diversity. This approach has recently been applied to quantify diversity in multiple aspects of individuals’ behavioral experience, including the diversity of daily activities (Lee et al., 2018), stressors (Koffer, Ram, Conroy, Pincus, & Almeida, 2016), emotions (Benson et al., 2017; Ong et al., 2018; Quoidbach, Gruber, & Norton, 2014), and social activities (Ram, Conroy, Pincus, Hyde, & Molloy, 2012). In similar fashion, control diversity quantifies how an individual’s control beliefs are dispersed across multiple domains of life, and thus provides information that is not captured by the typically used univariate arithmetic means of responses on multi-item scales of domain-specific control. As illustrated in Figure 1, Persons A and B do not differ in mean levels of control beliefs, averaged across domains. Both persons’ mean level of control is 0.86. However, Persons A and B differ considerably in control diversity. Person A perceives high levels (i.e., 3 on a 0 to 3 scale) of control over only two domains of life (home, network), and very low levels of control (none) over the other five domains listed. Person A’s control diversity is relatively low (CDa = .36) because her perceived control is concentrated in a few categories. In contrast, Person B perceives low levels of (i.e., 1 on a 0 to 3 scale) control consistently over six life domains and no control over discrimination. Person B has equivalent total control, but relatively high control diversity (CDb = .92) because her perceived control is spread evenly across many domains. To summarize, adapting Shannon’s (1948) concept of entropy, we quantify control diversity as the distribution of an individual’s control beliefs across multiple domains of life rather than looking at domain-specific control beliefs one by one.

Figure 1.

Participants with identical mean-levels of control over stressors (0.86), but who differ considerably in control diversity (person A: .36 vs. person B: .92).

The Psychology of Control Diversity and its Association with Negative Affect

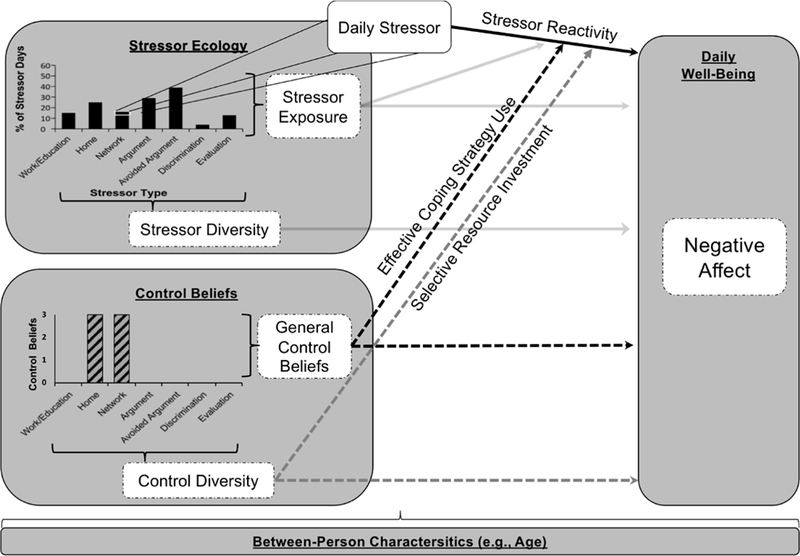

Figure 2 displays the conceptual diagram for the present study. Conceptually, daily control beliefs are particularly important for affective well-being and affective stressor reactivity (i.e., the likelihood that an individual will show emotional or physical reactions to the stressors he or she encounters, operationally defined as the difference in negative affect between a stressor-free day and a day with a stressor (Almeida, 2010). Self-Determination Theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000), for example, considers control beliefs an enabling factor that promotes effective strategy use for coping with stressors, which in turn boosts feelings of competence and facilitates numerous adaptive outcomes, including reduced negative affect (for overview, see Lachman et al., 2012). Consistent with this theoretical perspective, numerous empirical studies have documented the importance of control beliefs as a resource that protects against negative affect and daily affective stressor reactivity (Bookwala & Fekete, 2009; DeNeve & Cooper, 1998; Neupert et al., 2007; Ong et al., 2005; Windsor & Anstey, 2010). These prior studies have, however, only considered the role of generalized control beliefs and have not considered the role or structure of domain-specific control beliefs (each uniquely or all together).

Figure 2.

Both general control beliefs and control diversity (the extent to which control is spread across domains) are associated with daily well-being (dashed arrows). Control diversity and daily control are expected to relate to daily well-being directly or via stressor reactivity, operationally defined as the difference in negative affect between a stressor-free day and a day with a stressor (displayed as the arrow between a daily stressor and daily well-being).

In the current study, we examine how control diversity is associated with negative affect and daily affective stressor reactivity over and above associations documented for general perceived control. As a consequence, when older adults perceive their control to be high in a few domains and low in other domains (i.e., focused control beliefs), they are expected to experience less negative affect because they selectively invest remaining resources into fewer domains and select those that they perceive as controllable and thus are better able to cope with these stressors (cf. Baltes, Lindenberger, & Staudinger, 2006; Heckhausen et al., 2010; for discussion, see Gerstorf & Ram, 2015). Contrary, when older adults perceive control across many domains to be equally low or high (i.e., diffused control beliefs), they are expected to experience more negative affect because they invest their limited resources into all domains. Borrowing from and deliberately interpreting the literature on fragmented vs. differentiated self-concepts (for overview, see Diehl, Hastings, & Stanton, 2001; Diehl & Hay, 2010), we argue that this diffusion might reflect control illusion: if control does not differ across many domains, it suggests either the unlikely event that circumstances and domains are the same across categorically different contexts or that the individual applies a rigid schema of control beliefs regardless of context. The associations between control diversity and negative affect might be moderated by individuals’ average level of control. People with overall lower levels of control beliefs over stressors might especially need to selectively invest the resources they have into particular domains.

Control Diversity across Adulthood and Old Age

Drawing from tenets of lifespan developmental theory, one would expect that control diversity will decrease with age (Baltes & Baltes, 1990; Heckhausen et al. 2010). Specifically, as a consequence of being faced with increasingly frequent and severe loss experiences, older adults might perceive reduced control over particular life domains such as physical health. Such loss experiences and declining resources would in turn make it more likely for older adults to focus their remaining resources on a few cherished domains and experience a lack of perceived control over other domains (Baltes, Lindenberger, & Staudinger, 1990; Heckhausen et al., 2010). Applying this idea to stressor domains, older adults are presumably less able to adapt to multiple stressors and thus compensate by avoiding some stressors (selection) and focusing their limited (control) resources toward those stressors they cannot avoid (optimization; Charles, 2010; Neupert et al., 2007; Koffer et al., 2016).

For control over stressor domains, control diversity should reflect the person-environment transactions between stressor events and a person’s ability to apply his or her coping resources to manage the stressors (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Following Selection, Optimization, and Compensation theory (Baltes & Baltes, 1990), adjustments to overall declining resources should lead older adults to have perceived control concentrated in fewer domains and would thus be characterized by lower control diversity. For example, an older adult with a home stressor, a network stressor, a non-argument interpersonal tension, and an actual argument, might sacrifice coping resources, and thus perceived control, in all but the social-tension situations, in which she maintains high control. In contrast, younger and middle-aged adults might exhibit more control diversity because they have to manage multiple competing roles and demands (e.g., work, family, relationship; Lachman & Firth, 2004; Lee et al., 2018; Scott et al., 2014). We would thus expect a young adult who also experienced a home stressor, a network stressor, a non-argument interpersonal tension, and an argument to have control beliefs that are more evenly distributed across stressors.

The Present Study

In this study, we consider individual and age-related differences in how a given person’s control beliefs in daily life vary across several domains of stressor experiences – control diversity. We make use of data obtained in the NSDE that provides for a comprehensive assessment of domain-specific control beliefs and negative affect gathered in people’s everyday lives. First, we quantify control diversity and examine how control diversity differs across age. We expect that older age is associated with lower control diversity due to increased need to selectively concentrate coping resources. Second, we examine how control diversity is uniquely linked to daily negative affect and affective stressor reactivity. Negative affect measures allow us to understand the baseline influence of control diversity on affective well-being. Stressor reactivity separately allows the examination of control diversity and negative affect in the face of stressors. Lower control diversity, reflecting selectively concentrating resources rather than control illusion, should be associated with lower negative affect and ameliorated stressor reactivity. Third, we test whether such associations are moderated by age, expecting a stronger association between control diversity and affective stressor reactivity at older ages due to the necessity of optimizing even more limited resources. Finally, we explore whether associations between control diversity and daily negative affect are moderated by average control beliefs and stressor exposure, in that with reduced control potential (i.e., low average control beliefs) and/or increased demands on resources, it may become increasingly adaptive to focus control exertion over fewer domains. Note that our hypotheses are derived from the broader theoretical framework described above, all aspects of which we cannot yet fully test with the data at hand.

Method

To examine our research questions, we used data from the second wave of the National Survey of Daily Experiences (NSDE). Detailed descriptions of participants, variables, and procedures can be found in Almeida, McGonagle, and King (2009). Select details relevant to this report are given below.

Participants and Procedure

The NSDE consisted of 2,022 adults recruited from the national sample of the Midlife in the United States (MIDUS) study (Brim, Ryff, & Kessler, 2004). Participants (57% women) were between ages 33 to 84 years (MAge = 56.24, SDAge = 12.20), were generally in good health (M = 2.39, SD = 0.99, on a 0–4 scale), largely Caucasian (92%), with 3% African American and 4% of other ethnicities, mostly had education past high school (n = 1,728; 85%), and could be considered middle-class (annual household income M = $70,603.61, Median = $57,500, SD = $57,971). The general population in the US is less educated, has lower median household income, and is more racially heterogeneous than the NSDE sample (U.S. Census Bureau, 2014).

Participants were contacted on 8 consecutive evenings for a 15-min semi-structured telephone interview during which they were asked to report on the stressor experiences they had that day, their perceptions of those stressor events (including perceived control over the stressor event), and their affect (Almeida et al., 2009). Participants were compensated $25 for completing the NSDE protocol. In total, participants provided between 1 and 8 days of data (M = 7.37, SD = 1.29), with 93% providing 6 or more daily reports and 69% providing all 8 daily reports. Separately, all MIDUS participants were mailed and asked to complete a survey about physical and mental health, socio-demographics, and lifestyle.

Measures

Daily Negative Affect.

Individuals’ daily negative affect was measured using 14-items adapted from the Non-Specific Psychological Distress Scale (Kessler et al., 2002). Each evening, participants were prompted by the question “How much of the time today did you feel _________?”: restless or fidgety, nervous, worthless, so sad that nothing could cheer you up, that everything takes effort, hopeless, lonely, afraid, jittery, irritable, ashamed, upset, angry, and frustrated. Responses on a 0–4 scale (0 = none of the time, 1 = a little of the time, 2 = some of the time, 3 = most of the time, and 4 = all of the time) were averaged to obtain a daily negative affect score. We calculated Generalizability Theory reliability coefficients, which can be used to overcome shortcomings of conventional reliability coefficients and also indicate if the measure of negative affect was sensitive to within-person change (Cranford et al., 2006). Our results indicate fairly reliable measurement of individual differences in negative affect variability over days (Rc = .76), and very reliable measurement of person-level negative affect averaged across days (Rkf = 0.98).

Daily Stressors.

Individuals’ daily stressor events were measured each evening via a semi-structured interview using the Daily Inventory of Stressor Events (DISE; Almeida, Wethington, & Kessler, 2002). Participants were asked whether they had experienced each of 7 stressor types: arguments, avoided arguments (non-argument interpersonal tension), discrimination, work/education stressors, home stressors, network stressors, and other stressors. Each day, participants indicated whether they had (1) or had not (0) experienced each of the seven types of events.

Following our previous work (Koffer et al., 2016), we computed three variables from these 7 binary indicators. First, stressorid is a time-varying binary variable indicating whether one or more stressors (of any type) had occurred on each study day (0=no items were endorsed, 1=any of the seven items were endorsed). When negative affect is regressed on this binary indicator, the slope is an indicator of affective stressor reactivity. Second, stressorcounti indicates the total number of stressors (across all seven types) reported across the study period, and was calculated as the sum of the seven binary items each day; participants can only report one event per stressor type per day. Third, stressortypei is a 7-category nominal variable indicating the type(s) of stressor that occurred across the study period. On average, participants reported experiencing one or more stressors on 39% of study days, with an average of 3.77 (SD = 3.19) stressors across the study period. The most common stressor type was non-argument interpersonal tensions (31% of total stressors), followed by arguments (17%), home (15%), work/education (15%), “other” (11%), network (10%), and discrimination stressors (1%).

Daily Control Beliefs.

Upon endorsing a stressor experience, participants were asked to indicate how much control they perceived, “How much control did you have over the situation?”, using a 4-point scale: 0=none at all to 3=a lot. From these responses, we computed three time-varying variables: dailyaveragecontrolid indicates the average perceived control across all the stressor situations the individual experienced each day. For later use in the computation of control diversity, we also calculated a daily controlcounti variable as the sum total perceived control across all reported stressor types across the study period, and controlstressortypei is a 7-category nominal variable indicating the type(s) of stressor over which participants reported a numeric value for perceived control. Reported control was highest for non-argument interpersonal tensions (M=1.78, SD=1.17) and arguments (M=1.76, SD=1.10), followed by work (M=1.51, SD=1.19), home (M=1.25, SD=1.22), “other” (M=1.23, SD=1.24), discrimination (M=1.1, SD=1.19), and network stressors (M=0.55, SD=1.01).

Age.

Age was calculated as the difference between the date of the first daily interview and a given participant’s date of birth and scaled in years.

Data Preprocessing

In preliminary analyses, we computed the main variables of interest.

Control diversity.

In line with previous studies of diversity in psychosocial domains (Allen et al., 1998; Benson et al., 2018; Budescu & Budescu, 2012; Koffer et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2018; Quoidbach et al., 2014; Ram et al., 2012), control diversity was calculated for each individual (i) as the control across all domains (j) and across all study days and was quantified using Shannon’s (1948) entropy index. Specifically,

| (1) |

where m is the number of available control domain categories (m=7), and pij is the proportion of individual i’s control in each domain category, j=1 to m, across all days d = 1 to T; in other words, . Note that because individuals rate their control from 0 to 3, these values are used when computing the proportions. For example, consider Person A from Figure 1, who reported one stressor in each of the following categories across the entire study period: argument, non-argument interpersonal tension, work, home, and network stressor (7 total stressors, one of each type). The person rated controli, home and controli, network as 3 (a lot), while controli,work, controli, interpersonal_tension, and controli, argument as 0 (none). So, pi,home = controli,home/(controli,home + controli,network + controli, work + controli, interpersonal_tension + controli, argument) = 3/(3+3+0+0+0+0+0)=.5; pi,network= .5, pi,work = pi,interpersonal_tension = pi,argument =0. These proportions are then used in Equation 1 to calculate control diversity, CDA = .36. Following the formula, entropy scores can range from 0 (no diversity, with all of a person’s daily perceived control being in a single domain) to 1 (equal spread of perceived control across domains). We note that a person who reports a 3 consistently for all seven domains and a person who reports a 2 consistently for all seven domains would both have control diversity = 1 (perfectly evenly spread across all types), but differ in their average general control.

Stressor Diversity.

Following our previous work (Koffer et al., 2016), stressor diversity is also computed using Shannon’s diversity index. Following Equation 1 above, m here is the number of stressor types (m=7), and pij is the proportion of individual i’s stressor experiences that consist of stressor type j=1 to m. Stressor diversity may range from 0 (no diversity; all stressors concentrated in one type) to 1 (complete diversity; stressors spread evenly across available types).

Average Control over Stressors.

Each individual’s average control beliefs over stressors was quantified as the person-mean of the dailyaveragecontrolid scores; average of all study days completed, d=1 to Ti.

Stressor exposure.

Total stressor exposure is measured by counting the proportion of periods (e.g., days) on which stressors occur (Almeida, 2005; Bolger & Schilling, 1991). Each individual’s stressor exposure was quantified as the person-mean of an individual’s stressorcountid scores; average of all study days completed, d=1 to Ti.

Data Analysis

Age associations with control diversity.

The distribution of control diversity values was non-normal, highly positively skewed, and contained a large number of individuals (n=790; 45%) with control diversity scores of 0. We thus tested for age associations in two ways. First, using logistic regression, we examined the relation between a binary measure of control diversity and age. Specifically, we examined the likelihood of having any control diversity (i.e. > 0) to having 0 control diversity,

| (2) |

Where pcontroldiversityi is the probability that individual i’s control diversity score is > 0. Agei was centered at the sample mean (MAge = 56.24) and scaled in decades.

Second, among those individuals with control diversity > 0, age associations were described using a standard regression model,

| (3) |

where the linear age-gradient is indicated by α1. To accommodate the non-normality in the distribution of control diversity scores that were > 0, the positive Control Diversityi scores were log transformed. Again, Agei was centered at the sample mean and scaled in decades. These models were fit using the glm and lm functions in R (Marschner, 2011, R Core Team, 2016), respectively, with incomplete data treated as missing completely at random (Little & Rubin, 1987).

Control diversity associations with daily negative affect and affective stressor reactivity.

Relations between control diversity and daily negative affect were examined in a multilevel modeling framework that accommodated the nested nature of the data (days nested within persons), and, because control beliefs were assessed contingent upon reported stressor experiences, placed associations between control diversity and negative affect in the context of affective stressor reactivity, stressor exposure, and stressor diversity. The final model was structured as

| (4) |

where NegativeAffectid is modeled as a function of person-specific intercepts, β0i, person-specific affective stressor reactivity coefficients, β1i, that indicate the extent to which an individual’s NA differs between stressor-free days and days with stressors, and residual errors, eid that are assumed to be normally distributed. To accommodate the way control beliefs were measured, Stressorti was coded so that the reference category was a day with at least one stressor, and thus the slope of negative affect regressed on this variable indicates affective stressor reactivity with the opposite sign as typically seen in daily affective stressor reactivity literature (for reference category non-stressor day, see online Supplemental Table S.1). The two person-specific intercepts and affective stressor reactivity coefficients are, in turn, modeled as a function of the stressor exposure, stressor diversity, average control, and control diversity variables derived above. That is,

| (5) |

| (6) |

where u0i and u1i are residual between-person differences that are assumed multivariate normally distributed, with variances, and correlation , and are uncorrelated with time-specific residuals eid. The level 2 (person-level) equations are fit into the level one equation so that γ00–011reflect the intercept and effects of person level variables, while γ10–19 reflect the stressor reactivity slope and all person level interactions with that slope. Note that random effects are specified for intercept and slope of stressor day, allowing individuals to vary in negative affect levels and stressor reactivity. All interactions were included, then pruned to only significant higher order significant interactions. This left the model with γ19 , (i.e., how stress reactivity is moderated by the interaction of control diversity, average control, and stressor exposure) as a four-way interaction. To test our research questions, we are specifically interested in (1) the extent to which individual differences in control diversity are related to individual differences in negative affect over and above both average control beliefs and stress exposure (γ01,); (2) the extent that the relation between control diversity and negative affect is moderated by average control (γ05); (3) the extent to which individual differences in affective stressor reactivity are related to individual differences in control diversity (γ11); and (4) the extent that the relation between control diversity and affective stressor reactivity is moderated by average control (γ15).

Age as Moderator.

The model was then expanded to examine whether and how associations between control diversity and negative affect were moderated by age. Specifically, Agei was added as a person-level predictor in Equations 5 and 6.

Multilevel models were fit using the nlme library in R (Pinheiro. Bates, DebRoy, Sarkar, & R Core Team, 2018), with incomplete data treated as missing at random. We also tested for quadratic relations between control diversity and negative affect. Because these were not reliably different from zero, these were pruned for parsimony as were non-significant higher-order interactions. Person-level predictors were grand-mean centered, so the parameter estimates depict effects for the average person in the study (as described in the participants’ sections above) on a day with one or more stressors. Statistical significance was evaluated at α = .05.

Results

We used multilevel modeling to (1) quantify and investigate age associations with control diversity, (2) examine how control diversity is uniquely linked to daily negative affect and affective stressor reactivity, and (3) test whether such associations are moderated by age.

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1. Control diversity ranged from 0 to .92, with n = 790 (45% of total N = 1,749) scores of 0. For the remaining 55% of the sample with control diversity > 0, scores ranged from .15 to .92 (median = .36). Several points about the pattern of covariation are of note. First, control diversity showed moderately sized correlations with average control over stressors (r = .26). Second, higher control diversity was associated with more negative affect (r = .23), younger age (r = −.17), more stressor diversity (r = .71), and more stressor exposure (r = .58). Importantly, because control beliefs are only measured when individuals experience a stressor, at low levels of stressor diversity, there is not much room for variation in control diversity (see Supplemental Figure S.1). Third, average control over stressors in contrast only showed modestly sized associations with negative affect (r = −.09) and was not associated with age (r = −.02), stressor diversity (r = −.07), and stressor exposure (r = −.06). Fourth, as one would expect, both greater stressor exposure (r = .48) and greater stressor diversity (r = .26) were associated with higher overall levels of negative affect. Likewise, older age was associated with lower negative affect (r = −.16), lower stressor diversity (r = −.18), and less stressor exposure (r = −.23). In summary, descriptive associations among stress processes, control beliefs, and negative affect – and particularly the relative divergence between average control over stressors and control diversity – provide some initial hints that control diversity adds to our understanding of affective and stress processes across adulthood and old age.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations of Daily Negative Affect, Control Diversity Stressor Exposure, Stressor Diversity, Average Control over Stressors, and Age

| M | SD | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) (6) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Control diversity (0 – .92) | 0.25 | 0.25 | -- | |||||

| (2) Average negative affect (0 – 3) | 0.21 | 0.28 | .23 | -- | ||||

| (3) Age (33 – 84) | 56.24 | 12.20 | −.17 | −.16 | -- | |||

| (4) Average control over stressors (0 – 3) | 1.49 | 0.93 | .26 | −.09 | −.02 | -- | ||

| (5) Stressor diversity (0 – 1) | 0.41 | 0.27 | .71 | .26 | −.18 | −.07 | -- | |

| (6) Stressor exposure (0 – 5) | 0.53 | 0.48 | .58 | .48 | −.23 | −.06 | .67 | -- |

Note: N = 1,749. Of the total 2,022 participants, there were 208 missing data points for stressor diversity because participants did not report any stressors and an additional 65 missing data points for control diversity because participants did not report their control beliefs. M = Mean; SD = Standard Deviation.

Control Diversity across Adulthood and old Age

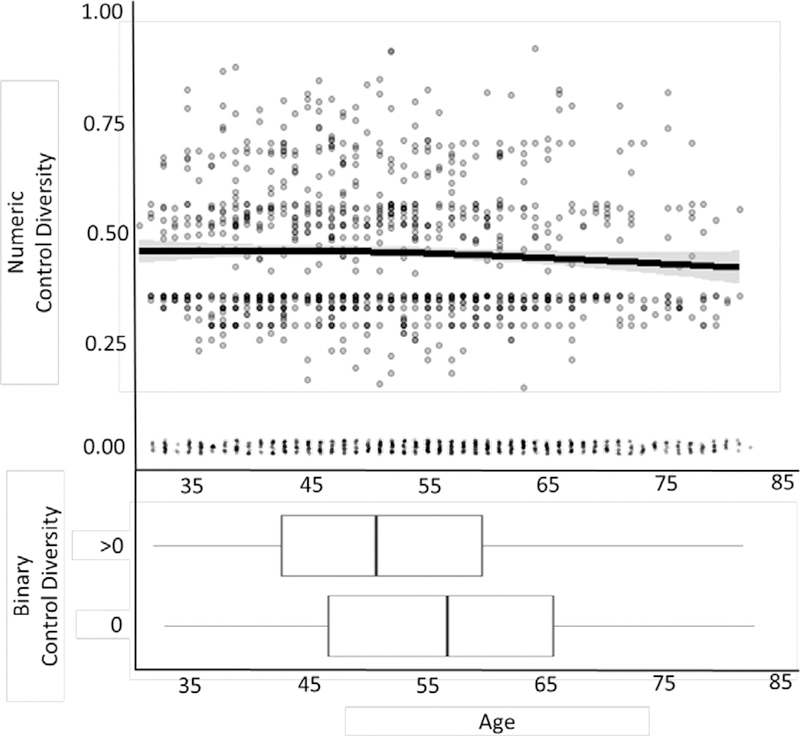

Table 2 presents results from logistic and linear regression analyses examining how age is associated with differences in control diversity (Research Question 1). Results from the logistic regression (column 1) indicated that older age was associated with lower likelihood (OR= 0.74, 95% CI = [0.68, 0.80])) of having control diversity > 0, compared to no (=0) control diversity. With each decade of age, adults have 1.35 greater odds of experiencing zero control diversity. Results from the linear regression model (column 2) indicated that age was not related to level of non-zero control diversity (α1 = −0.02, p = .07), with age accounting for only 0.3% of between-person differences among those with non-zero control diversity. These findings are shown in Figure 3. In the bottom portion of the figure, box plots indicate the age distribution of individuals who had 0 or > 0 control diversity. Mapping the logistic regression results, the 0 control diversity group has a higher mean age (M = 57.68, SD = 12.41) than the > 0 control diversity group (M = 53.44, SD = 11.35). The upper panel shows the lack of association between age and control diversity among those with > 0 control diversity (flat regression line). Together, the results indicate that older participants are more likely to experience 0 control diversity than younger adults, meaning that older adults are more likely to have their control beliefs concentrated in one domain. However, when experiencing some control diversity (i.e., control beliefs vary across more than one domain) older adults’ control diversity is similar to that of younger adults.

Table 2.

Age Differential Associations in Control Diversity: Likelihood of >0 Control Diversity and Age Trajectory of Log(>0 Control Diversity)

| Logistic Regression | Linear Regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | (SE) | Estimate | (SE) | |

| Intercept, α0 | 1.19* | (0.06) | −0.85* | (0.01) |

| Age (Decade) α1 | 0.74* | (0.03) | −0.02 | (0.01) |

| Model Fit | AIC = 2357.9 | R2 = .003 | ||

Note. N = 1,749, with 273 missing cases primarily (76% of missing) due to no reported stressors, Logistic regression reference group is positive control diversity, compared to 0 control diversity, non-zero control diversity scores were log transformed for linear regression, T≈8 days; SE=Standard Error.

= p < .05.

Figure 3.

Age associations in numeric and binary control diversity in the National Survey of Daily Experiences. In the top panel, older adults’ trend toward exhibiting lower numeric control diversity, with perceived control being more focused on fewer domains rather than spread widely across many different domains. Note the regression line is determined by exponentiating the natural log transformed control diversity results in Table 2. Note that darker circles represent more data points, and control diversity scores of 0 are jittered for ease of viewing. In the bottom panel, we display box plots of binary control diversity scores. Older adults are more likely to obtain control diversity scores of 0, with all perceived control concentrated in one domain, as compared to positive control diversity. Missing cases for control diversity are individuals who were missing control belief data across the entire reporting period, primarily (76% of missing) due to reporting no stressors across the entire study period.

Control Diversity Associations with Negative Affect and Affective Stressor Reactivity

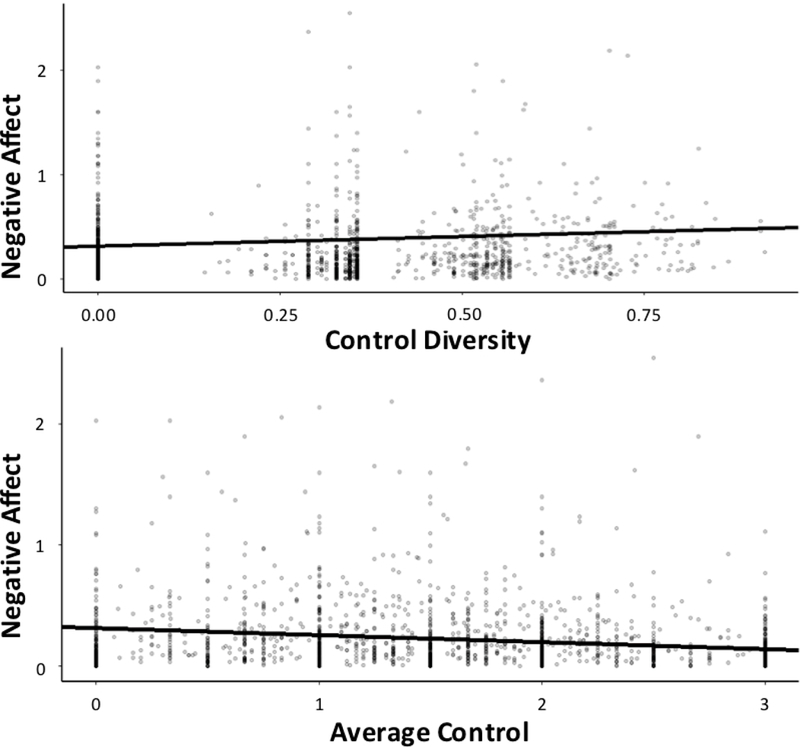

Results from the multilevel model examining associations between control diversity, stressor diversity and negative affect are shown in Table 3 (Research Question 2). The prototypical participant’s negative affect on a day with one or more stressors was estimated as γ00 = 0.314 (p < .001) on the 0 to 4 scale. In line with previous research (Koffer et al., 2017, Neupert et al., 2007; Ong et al., 2005), and as shown in the bottom panel of Figure 4, lower overall level of control beliefs over stressors was associated with higher negative affect on stressor days, γ02 = −0.059 (p < .001). As well, more stressor exposure, γ03 = 0.265 (p = .0001), less stressor diversity, γ04 = − 0.247 (p = .0001), and younger age, γ012 = − 0.002 (p = .0001), were each associated with higher negative affect on stressor days.

Table 3.

Results From Multilevel Model Assessing Associations of Control With Daily Negative Affect and Age as a Moderator of Those Associations

| Est. | (CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed Effects | ||

| Intercept, γ00 | 0.314* | [0.29, 0.34] |

| Control Diversity, γ01 | 0.189* | [0.06, 0.32] |

| Average Control over Stressors, γ02 | −0.059* | [−0.08, −0.03] |

| Stressor Exposure, γ03 | 0.265* | [0.20, 0.33] |

| Stressor Day (reference= stressor day; i.e., −m), γ10 | −0.174* | [−0.19, −0.16] |

| Stressor Diversity, γ04 | −0.247* | [−0.35, −0.14] |

| Control Diversity × Average Control over Stressors, γ05 | −0.085 | [−0.19, 0.02] |

| Control Diversity × Stressor Exposure, γ06 | 0.004 | [−0.21, 0.22] |

| Control Diversity × Stressor Diversity, γ07 | −0.095 | [−0.52, 0.33] |

| Average Control over Stressors × Stressor Exposure, γ08 | −0.036 | [−0.11, 0.03] |

| Average Control over Stressors × Stressor Diversity, γ09 | −0.009 | [−0.09, 0.07] |

| Stressor Exposure × Stressor Diversity, γ010 | −0.228* | [−0.41, −0.05] |

| Stressor Day × Average Control over Stressors, γ12 | 0.040* | [−0.02, 0.06] |

| Stressor Day × Stressor Exposure, γ13 | −0.063* | [−0.12, −0.01] |

| Stressor Day × Stressor Diversity, γ14 | 0.132* | [0.05, 0.21] |

| Stressor Day × Average Control over Stressors × Stressor Exposure, γ15 | 0.022 | [−0.03, 0.07] |

| Age, γ012 | −0.002* | [−0.003, −0.001] |

| Age × Average Control over Stressors, γ014 | 0.000 | [−0.001, 0.001] |

| Age × Stressor Day, γ110 | 0.002* | [0.001, 0.003] |

| Age × Stressor Exposure, γ015 | −0.002 | [−0.01, 0.001] |

| Age × Stressor Diversity, γ016 | −0.001 | [−01, 0.004] |

| Average Control over Stressors × Stressor Exposure × Control Diversity, γ011 | 0.129 | [−0.006, 0.004] |

| Stressor Day × Control Diversity, γ11 | −0.157* | [−0.25, −0.07] |

| Stressor Day × Average Control over Stressors × Control Diversity, γ16 | 0.030 | [−0.04, 0.10] |

| Stressor Day × Stressor Exposure × Control Diversity, γ17 | −0.046 | [−0.22, 0.13] |

| Stressor Day × Control Diversity × Stressor Diversity, γ18 | 0.293 | [−0.01, 0.60] |

| Stressor Day × Average Control over Stressors × Stressor Exposure × Control | ||

| Diversity, γ19 | −0.234* | [−0.39, −0.08] |

| Age × Control Diversity, γ013 | 0.000 | [−0.001, 0.001] |

| Random effects | ||

| Standard Deviation of Intercept () | 0.280 | [0.269, 0.292] |

| Correlation Intercept, Stressor Day () | −0.906 | [−.938, −.860] |

| Standard Deviation Stressor Day () | 0.133 | [0.120, 0.147] |

| Residual Standard Deviation (σe) | 0.216 | [0.213, 0.219] |

| Fit indices | ||

| AIC | 1340.616 | |

| −2LL | 1276.616 | |

Note. N=2220; CI = 95% Confidence Interval, AIC=Akaike information criterion; −2LL=−2(Log Likelihood)

= p < .05.

Figure 4.

Main effects of how control diversity (upper panel) and average control beliefs (lower panel) are associated with negative affect (defined here as an individual’s mean negative across all study days). The overlayed regression (derived from Table 3) shows more control diversity is associated with higher average negative affect (r = .23; γ01=0.19, p = .006), whereas higher average control beliefs are associated with lower negative affect (r = −.09; γ02= −0.06, p = .012).

As expected, stressor exposure moderated the association between stressor diversity and negative affect, γ010 = −0.228 (p = .013), such that higher stressor exposure combined with lower stressor diversity was associated with particularly high negative affect. Lower average control beliefs over stressors was associated with higher affective stressor reactivity, γ12 = 0.040 (p < .001). Higher affective stressor reactivity was also associated with higher stressor exposure (γ13 = −0.063, p = .03), lower stressor diversity (γ14 = 0.132, p < .001), and younger age (γ110 = 0.002, p < .001). Broadly summarized, and as expected, those who are younger, report lower levels of average control over stressors, experience more stressors, and experience less stressor diversity report more negative affect and affective stressor reactivity.

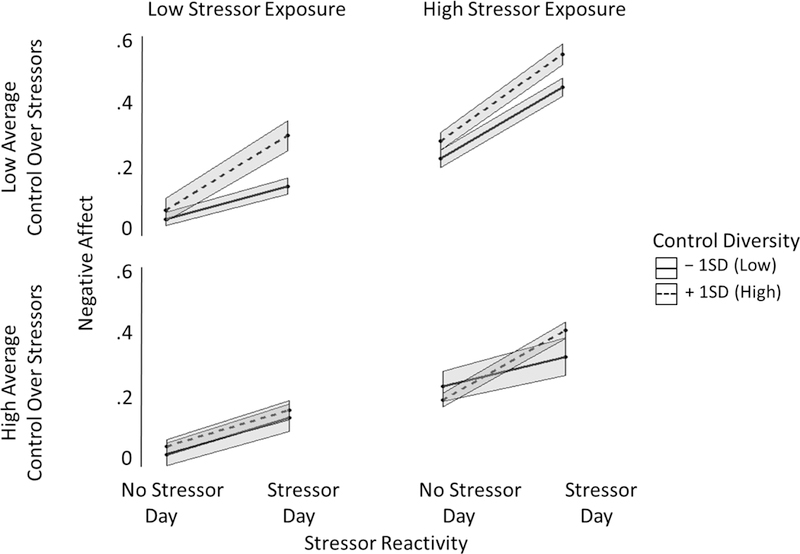

Of specific interest for our research questions, control diversity was, over and above all other stress and control belief covariates, uniquely associated with negative affect, γ01 = 0.189 (p = .006). As shown in the top panel of Figure 4, greater control diversity is associated with higher average negative affect. In addition, control diversity was related to affective stressor reactivity, γ11 = −0.157 (p = .0007), such that those with higher control diversity had particularly high affective stressor reactivity. We also found a four-way interaction among stressor day, stressor exposure, average control beliefs over stressors, and control diversity (γ19 = −0.234, p = .0033). The most striking feature of this interaction is graphically shown in Figure 5. Higher control diversity (dotted line) was associated with greater affective stressor reactivity (steeper sloped lines between no stressor day and stressor days). Those with lower average control over stressors and low stressor exposure (top left panel), had particularly pronounced differences in affective stressor reactivity between high and low control diversity. Simple slopes tests run separately on stressor and non-stressor day confirmed that on stressor days, low control diversity was related to lower negative affect in the presence of low control, and the effect of control beliefs is amplified in the presence of low exposure (stressor day simple slope test of control diversity effect: high control, low exposure differs from low control, high exposure, t-value = −2.36, p = 0.02; high control, low exposure marginally differs from low control, low exposure, t-value = −1.85, p = 0.07). On non-stressor days, low control diversity is related to higher negative affect only in the presence of high stressor exposure and low control beliefs over stressors (non-stressor day simple slope test of control diversity effect: high control, high exposure differs from low control, high exposure, t-value = −2.13, p = 0.03). Otherwise, average control beliefs and stressor exposure appear less relevant to the control diversity effect on non-stressor days (i.e., no simple slope differences, ps > .05). We are cautious in interpreting this exploratory four-way interaction, particularly as control beliefs were only measured when individuals’ reported a stressor, but it does corroborate lower-order interactions. The findings conjointly suggest that in the face of stressors, when an individual has low average control beliefs, it is better to have them concentrated in one or few domains (i.e. low control diversity) rather than spread these broadly across many domains.

Figure 5.

Illustrating the 4-way interaction effect of stressor reactivity × average control × stressor exposure × control diversity. High control diversity (dotted line) was associated with greater stressor reactivity (steeper sloped lines between no stressor day and stressor days). Those with low average control over stressors and low stressor exposure (top left panel), had particularly pronounced difference in stressor reactivity between high and low control diversity. On non-stressor days, control beliefs over stressors appear less relevant (i.e., standard error lines on no stressor days overlap across control diversity groups). These findings conjointly suggest that in the face of stressors, when one has low average control beliefs, it is better to have them concentrated in one or few domains, rather than spread thinly across many domains.

Importantly, we did not find any evidence that age moderated the association between control diversity and negative affect or affective stressor reactivity (Research Question 3).

Discussion

Using data from the National Study of Daily Experiences (NSDE), we (1) quantified individuals’ control diversity as a person-level summary of their across-domain control beliefs and investigated age differences in control diversity, (2) examined how control diversity is uniquely linked to daily negative affect and affective stressor reactivity, and (3) tested whether such associations are moderated by age. First, results indicate that older adults are more likely to have control beliefs concentrated in one domain. Second, higher control diversity was, over and above average control beliefs and stress exposure, associated with more negative affect and greater affective stressor reactivity. Third, age did not moderate the associations between control diversity and negative affect. We conclude from our national US sample that control diversity indeed matters for affective well-being in adults’ daily lives. Overall, our findings suggest that people who have control concentrated in fewer life domains (less control diversity) have lower negative affect and less affective stressor reactivity. We found no age differential effects in how control diversity related to negative affect and affective stressor reactivity. Effect sizes were in the small to moderate range.

We take our findings to highlight the importance of considering how individuals’ control beliefs vary across domains and contemplate in our discussion possible underlying mechanisms and practical implications.

Control Diversity across Adulthood and Old Age

A central aim of the present study was to examine whether control diversity differed with age. Our findings suggest that older adults are more likely to have control beliefs concentrated in one domain compared to younger adults, but that if they experience any control belief spread across domains, they do not differ from younger adults. These findings are consistent with theoretical notions that emphasize the adaptive capabilities of older adults when being confronted with increasingly frequent and severe loss experiences (Baltes & Smith, 2003; Heckhausen et al., 2010). For example, theories of developmental self-regulation suggest that individuals adjust to changing life conditions in older age by focusing on those domains that are still manageable (Heckhausen et al., 2010). Thus, they are able to maintain their sense of control in select domains of functioning. Our findings are in line with this reasoning, showing that in the context of normative changes in older age (e.g., poorer health), control beliefs might be concentrated in selected domains. However, when it seems necessary, control beliefs flexibly spread over diverse domains highlighting the potential for plasticity in older age development (Baltes & Smith, 2003).

We conducted a follow up analysis excluding domains one by one in order to test whether results were driven by one particular domains. Results indicated that this was not the case suggesting that control diversity in itself has predictive validity for affective well-being. The robustness of directional pattern of results highlights the predictive validity of control diversity.

Over and above corroborating and extending our initial evidence, it will be important for future research to examine possibly underlying mechanisms and pathways, including the role of compromised resources in the health and social domains.

Control Diversity Associations with Negative Affect and Affective Stressor Reactivity

Our results are also in line with previous research demonstrating that higher average control beliefs in daily life are linked to lower negative affect and operate as a buffer of affective stressor reactivity (Hay & Diehl, 2010; Koffer et al., 2017; Neupert et al., 2007; Ong et al., 2005). Over and above these well-known associations, we found that higher control diversity was linked to more negative affect, suggesting that the extent to which a given person’s control varies across stressor domains also plays an important role in how vulnerable that person is for compromised affective well-being. We found that for those with lower stressor exposure, low average control beliefs combined with high control diversity was associated with particularly high affective stressor reactivity. Our findings conjointly suggest that in the face of stressors, when one has low average control beliefs, it is better to have them concentrated in one or few domains (i.e., low control diversity) rather than spread broadly across many domains. These findings are in line with a developmental regulation perspective (Heckhausen, Wrosch, & Schulz, 2010) and suggest that with limited perceived resources available (i.e., overall less control), perceiving control in fewer domains is more adaptive for affective well-being. However, this seems to not be the case when overall control is higher when people are faced with a stressor, which indicates that a wider range of control opportunities might indeed matter for the adaptivity of control diversity.

For control diversity, it appears beneficial to be more selective, focusing one’s resources on a few domains, and letting go of other domains. It will be highly informative to target in future studies whether the control domains selected are also the ones that people rate as being important and meaningful to themselves (Baltes & Baltes, 1990; Krause, 2007). To illustrate, it is possible that perceiving control over those domains that are subjectively most meaningful to participants is more important for affective well-being than perceiving control over domains that do not matter to them (Shane & Heckhausen, 2016). Thus, future research needs to further examine whether the meaningfulness or importance of specific life domains might moderate associations of control diversity and affective well-being.

Limitations and Outlook

We note several limitations of our study. Beginning with limitations of our measures, we note that our selection of control domains was restricted to the seven stressor types measured in the NSDE. The specific domains assessed have implications for measurement of control diversity and its associations with negative affect. To illustrate, both conceptual notions and empirical research have highlighted the importance of control beliefs in the health domain for aging, and that the extent of importance changes with age (Lachman, 1986). Age differential effects in control diversity and its associations with negative affect may differ when health is or is not included in the assessment. Future work should examine additional domains of control to validate whether control diversity across other domains relates to affective well-being. For example, it could be that when including more age-sensitive (stressor) domains (e.g., health), age differential effects in control diversity become more salient. To ensure that our results were not driven by the non-argument interpersonal tension domain (the largest domain as well as a highly age-relevant one), we conducted a sensitivity check removing it from the control diversity computation. Although, we found the same pattern of associations here, replication of age-related differences in control diversity and its associations with negative affect may depend on the specifics of the measurement paradigm.

Out of the larger space of categorical intraindividual variability constructs (van Geert & van Dijk, 2015; Koffer et al., 2017), we have made use of a diversity measure in our initial step because this measure allows us to link our results directly with earlier reports using this measure in other construct domains (e.g., daily and social activities, emotions). A viable alternative approach would have been to make use of nominal categorical intraindividual variability measures that allow capturing the match of nominal categorical information of stressor and control domains.

Similarly, daily control beliefs in the NSDE are asked in relation to the daily stressors that had occurred. We thus cannot say whether our results generalize to general measures of domain-specific control beliefs. However, follow-up analyses controlling for gender- and education-related differences (e.g.., in exposure and reactivity to certain stressors) did not change the findings reported here. We also performed a selectivity analysis to examine the 65 individuals who provided stressor data but did not provide control beliefs data. These participants were found to report significantly fewer stressors (M(SD)missing = 0.23(0.19); M(SD)present = 0.61(0.47)), have lower stressor diversity (M(SD)missing = 0.09(0.16); M(SD)present = 0.42(0.27)), and have significantly lower negative affect (M(SD)missing = 0.08(0.18); M(SD)present = 0.23(0.29)) than the rest of the sample. Demographically, these participants were significantly older (M(SD)missing = 62.43(11.05); M(SD)present = 55.35(12.02)) and more likely to be male (Nmissing_male=40, p < .001), but they were not significantly different in earned income, physical health, or mental health (all p > .05). These findings suggest that NSDE participants with missing control belief data are likely not suffering from worse life conditions and missingness may thus be treated as random. However, if participants skipped end of day interviews when major challenges occurred, we may miss occasions when negative affect would presumably be highest.

Common method bias might have affected our results since measurement context effects existed (i.e., predictor and outcome variables measured at the same point in time, and using the same medium) (Podsakoff et al., 2003; 2012). By using self-reported data shared method variance might have inflated the relationships between variables of interest and might have affected our results. Domain specific control beliefs as rated by others based on situational characteristics might provide an opportunity to further disentangle subjective experience and objective situations (e.g., interviewer rated). Alternatively, experimentally manipulating domain-specific control might allow to reduce shared method variance. If such data becomes available, future research could benefit from using multiple-source reports (e.g., self and other report; subjective and objective rating).

We also note that multifaceted processes operate that might exacerbate or buffer negative affect in everyday life. Focusing solely on control and stressor (diversity) as buffers of daily negative affect within the chosen timeframe is extremely simplifying and it is important to understand how control beliefs at different timescales jointly associate with other components of well-being. Thus, it would be highly informative to examine how control diversity might operate alongside other psychosocial risk and resilience factors such as daily social support (Antonucci, 2001) and how control beliefs are associated with selecting particular coping strategies over others (e.g., active problem solving versus emotion-regulation strategies). To illustrate, control diversity might be especially relevant when other resources are limited, such as in low-social support situations compared to high-social support situations.

Similarly, the role of control diversity for stressor reactivity should further be examined over and above affective reactivity and also encompass physiological reactivity (e.g., cortisol). Relatedly, our analysis did not to account for objective control potential on relevant factors such as social network and work. Previous research has shown that the subjective perceptions individuals hold over the amount of control they have often differs from the objective control they have, and people vary in the amount of control they perceive over the same situation independent of their actual control (Lachman, Neupert, & Agrigoroaei, 2011). Thus, it is not possible to draw firm conclusions about differences in actual control in stressor domains examined (Skinner, 1996). It would be an interesting question for future research to systematically examine the role of discrepancies between objective control potential and subjective perceptions thereof.

As noted earlier, our findings need to further be replicated in future studies. Our results found in data from the National Study of Daily Experiences (NSDE) are based on a large, national US sample (Almeida, McGongle, & King, 2009), but these initial findings thus need to be corroborated, replicated, and extended. It is also necessary to test systematically whether and how these results generalize to less positively selected, more diverse population segments, such as people suffering from poor health and/or very old adults in their 80s and 90s. It stands to reason that mortality-related mechanisms or other progressive processes leading towards death (e.g., deteriorating health) overwhelm the regulatory or motivational capabilities that usually keep the system stable and thereby profoundly shape the associations between control diversity and affective well-being (Gerstorf & Ram, 2015). Having included only very few people older than age 80 leaves many questions open about how control diversity operates in very old age and the end of life. For example, drawing from previous research (Baltes & Smith, 2003) and empirical studies focusing on late life (Hueluer et al., 2013, 2015), one could expect that the general picture found across adulthood and old age may not necessarily generalize to the last phase of life because pervasive mortality-related processes might prompt regulatory capabilities to break down and so compromise and diminish control diversity. It would also be intriguing to test whether and how findings about historical changes in domain-generalized control beliefs (Drewelies, Agrigoroaei, Lachman, & Gerstorf, 2018; Drewelies, Deeg, Huisman, & Gerstorf, 2018) generalize to control diversity.

Finally, we acknowledge several measurement issues embedded in the study design have implications for conceptual interpretation of control diversity. NSDE assesses stressor events and control over stressors every 24 hours at the end of the day. Though the same type of event may occur on successive days—and may indicate carryover of a causal mechanism (e.g., poverty persists)— any single event may not be reported on multiple days. Further, control beliefs are only assessed upon experiencing a stressor. We thus note that a denser ecological momentary assessment (EMA) design, and measurement of control beliefs in the absence of stressor events, would allow us to investigate the potentially fine-grained dynamics of control diversity and affective stressor reactivity (Shiffman, Stone, & Hufford, 2008). To illustrate, it would be important to separate within-person and between-person portions of control diversity in future studies knowing that within-person associations of control and effective well-being do not necessary translate to between-person associations (Drewelies et al., 2018).

Relatedly, using an observational study design like ours, it is not possible to draw temporal, let alone causal, inferences about how control diversity and negative affect are associated with each other. Applying multilevel modeling, control diversity was used here as a predictor of negative affect, but it could also be that negative affect influences (subsequent) control diversity. Similarly, we cannot draw any conclusions about the intentionality of stressor-related control diversity. To illustrate, older individuals may actively and intentionally concentrate their control beliefs on specific stressors. In contrast, it would also be plausible to assume that control diversity develops intuitively out of experiences grounded on available resources and that control beliefs are not actively distributed across domains. To better understand the underlying mechanisms of how control diversity is linked to negative affect in the daily stress process, more mechanism-oriented research is needed that utilizes both more closely spaced and a larger number of measurement occasions. Additionally, one could also examine the intentionality of control diversity explicitly using self-report measures.

Conclusions

Taken together, our analyses of data from the NSDE indicate that higher control diversity is linked to higher negative affect, over and above general levels of perceived control. These analyses extend earlier reports that examined domain-specific control beliefs one by one, through articulation of the control diversity construct and use of a measure that quantifies how control beliefs vary across multiple domains. Results provide initial evidence from a nation-wide sample in the US that older adults spread their control beliefs over fewer stressor domains than middle-aged and younger adults, but we found no age differential effects in how control diversity was related to negative affect and affective stressor reactivity. We take our findings to suggest that control diversity provides additional and unique insights into the stability and change of control beliefs across adulthood and old age and how these contribute to affective well-being. We note that more mechanistic research is needed to better understand underlying pathways through which control diversity shapes adults’ negative affect.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the support provided by the National Institutes of Health. The National Study of Daily Experiences was supported by R01 AG19239. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Footnotes

Johanna Drewelies, Humboldt University Berlin, Department of Psychology, Berlin, Germany; Rachel E. Koffer, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh; Nilam Ram, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, Pennsylvania State University and German Institute for Economic Research; David M. Almeida, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, Pennsylvania State University; Denis Gerstorf, Humboldt University Berlin, Department of Psychology, Berlin, Germany.

References

- Allen PA, Kaufman M, Smith AF, & Propper RE (1998). A molar entropy model of age differences in spatial memory. Psychology and Aging, 13, 501–518. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.13.3.5011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM, McGonagle K, & King H (2009). Assessing daily stress processes in social surveys by combining stressor exposure and salivary cortisol. Biodemography and Social Biology, 55, 219–237. doi: 10.1080/19485560903382338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM, Wethington E, & Kessler RC (2002). The daily inventory of stressful events: An interview-based approach for measuring daily stressors. Assessment, 9, 41–55. doi: 10.1177/1073191102009001006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci TC (2001). Social relations: An examination of social networks, social support, and sense of control In Birren JE & Schaie KW (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of aging (5th ed, pp. 427–453). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baltes PB, & Baltes MM (1990). Psychological perspectives on successful aging: The model of selective optimization with compensation In Baltes PB & Baltes MM (Eds.), Successful aging: Perspectives from the behavioral sciences (pp. 1–34). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511665684.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baltes PB, Lindenberger U, & Staudinger UM (2006). Life span theory in developmental psychology In Damon W & Lerner RM (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol 1. Theoretical models of human development (6th ed, pp. 569–664). New York, NY: Wiley. doi: 10.1002/9780470147658.chpsy0111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baltes PB, & Smith J (2003). New frontiers in the future of aging: From successful aging of the young old to the dilemmas of the fourth age. Gerontology, 49, 123–135. doi: 10.1159/000067946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Benson L, Ram N, Almeida DM, Zautra AJ, & Ong AD (2017). Fusing biodiversity metrics into investigations of daily life: Illustrations and recommendations with emodiversity. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbx025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D, & R Core Team (2018). nlme: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models. R package version 31–137, <URL: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nlme>. [Google Scholar]

- Bookwala J, & Fekete E (2009). The role of psychological resources in the affective well-being of never-married adults. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 26, 411–428. doi: 10.1177/0265407509339995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brim OG, Ryff CD, & Kessler R How healthy are we? A national study of well-being at midlife. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Budescu DV, & Budescu M (2012). How to measure diversity when you must. Psychological Methods, 17, 215–227. doi: 10.1037/a0027129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranford JA, Shrout PE, Iida M, Rafaeli E, Yip T, & Bolger N (2006). A procedure for evaluating sensitivity to within-person change: Can mood measures in diary studies detect change reliably? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32, 917–929. doi: 10.1177/0146167206287721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeNeve KM, & Cooper H (1998). The happy personality: A meta-analysis of 137 personality traits and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 124, 197–229. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.124.2.197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl M, Hastings CT, & Stanton JM (2001). Self-concept differentiation across the adult life span. Psychology and Aging, 16, 643–654. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.16.4.643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl M, & Hay EL (2010). Risk and resilience factors in coping with daily stress in adulthood: The role of age, self-concept incoherence, and personal control. Developmental Psychology, 46, 1132–1146. doi: 10.1037/a0019937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewelies J, Agrigoroaei S, Lachman ME, & Gerstorf D (2018). Age variations in cohort differences in the United States: Older adults report fewer constraints nowadays than those 18 years ago, but mastery beliefs are diminished among younger adults. Developmental Psychology, 54, 1408–1425. doi: 10.1037/dev0000527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewelies J, Deeg DJH, Huisman M, & Gerstorf D (2018). Perceived constraints in late midlife: Cohort differences in the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam (LASA). Psychology and Aging, 33, 754–768. doi: 10.1037/pag0000276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewelies J, Schade H, Hulur G, Hoppmann CA, Ram N, & Gerstorf D (2018). The more we are in control, the merrier? Partner perceived control and negative affect in the daily lives of older couples. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gby009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eizenman DR, Nesselroade JR, Featherman DL, & Rowe JW (1997). Intraindividual variability in perceived control in a older sample: The MacArthur successful aging studies. Psychology and Aging, 12, 489–502. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.12.3.489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Geert P, & van Dijk M (2015). The intrinsic dynamics of development In Scott RA, Kosslyn SM, & Pinkerton N (Eds.), Emerging trends in the social and behavioral sciences (pp. 1–16). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. doi: 10.1002/9781118900772 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstorf D, & Ram N (2015). A framework for studying mechanisms underlying terminal decline in well-being. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 39, 210–220, doi: 10.1177/0165025414565408 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hay EL, & Diehl M (2010). Reactivity to daily stressors in adulthood: The importance of stressor type in characterizing risk factors. Psychology and Aging, 25, 118–131.doi: 10.1037/a0018747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckhausen J, Wrosch C, & Schulz R (2010). A motivational theory of life-span development. Psychological Review, 117, 32–60. doi: 10.1037/a0017668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hueluer G, Infurna FJ, Ram N, & Gerstorf D (2013). Cohorts based on decade of death: No evidence for secular trends favoring later cohorts in cognitive aging and terminal decline in the AHEAD study. Psychology and Aging, 28, 115–127. doi: 10.1037/a0029965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hueluer G, Ram N, & Gerstorf D (2015). Historical improvements in well-being do not hold in late life: Studies of birth-year and death-year cohorts in national samples in the US and Germany. Developmental Psychology, 51, 998–1012. doi: 10.1037/a0039349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand S-LT, …Zaslavsky AM(2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine, 32, 959–976. doi: 10.1017/S0033291702006074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliegel M, & Sliwinski M (2004). MMSE cross-domain variability predicts cognitive decline in centenarians. Gerontology, 50, 39–43. doi: 10.1159/000074388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koffer RE, Ram N, Conroy DE, Pincus AL, & Almeida DM (2016). Stressor diversity: Introduction and empirical integration into the daily stress model. Psychology and Aging, 31, 301–320. doi: 10.1037/pag0000095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koffer R, Drewelies J, Almeida D, Conroy D, Pincus A, Gerstorf D, & Ram N (2017). The role of general and daily control beliefs for affective stressor-reactivity across adulthood and old age. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbx055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N (2007). Age and decline in role-specific feelings of control. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 6, 28–35. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.1.S28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunz-Ebrecht SR, Kirschbaum C, Marmot M, & Steptoe A (2004). Differences in cortisol awakening response on work days and weekends in women and men from the Whitehall II cohort. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 29, 516–528. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(03)00072-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME (1986). Locus of control in aging research: A case for multidimensional and domain-specific assessment. Psychology and Aging, 1, 34–40. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.1.1.34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, Firth KM, (2004). The adaptive value of feeling in control during midlife In Brim OG, Ryff CD & Kessler R (Eds.), How healthy are we? A national study of well-being at midlife (pp. 320–349). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, Neupert SD, & Agrigoroaei S (2012). The relevance of a sense of control for health and aging In Schaie KW & Willis SL (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology and aging (7th edition, pp. 175–190). New York, NY: Elsevier. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-380882-0.00011-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman M, & Weaver SL (1998). Socio-demographic variations in the sense of control by domain: Findings from the MacArthur studies of midlife. Psychology and Aging, 13, 553–562. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.13.4.553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, & Folkman S (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Koffer RE, Sprague BN, Charles ST, Ram N, & Almeida DM (2018). Activity diversity and its associations with psychological well-being across adulthood. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 73, 985–995. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbw118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefcourt HM (1984). Research with the locus of control construct: Extensions and limitations (Vol. 3). Orlando, FL: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levenson H (1974). Activism and powerful others: Distinctions within the concept of internal-external control. Journal of Personality Assessment, 38, 377–383. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1974.10119988 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, & Rubin DB (1987). Statistical analysis with missing data. New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- McAvay GJ, Seeman TE, & Rodin J (1996). A longitudinal study of change in domain-specific self-efficacy among older adults. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 51, 243–253. doi: 10.1093/geronb/51b.5.p243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesselroade JR (2001). Intraindividual variability in development within and between individuals. European Psychologist, 6, 187–193. doi: 10.1027//1016-9040.6.3.187 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neupert SD, Almeida DM, & Charles ST (2007). Age differences in reactivity to daily stressors: The role of personal control. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 62, 216–225. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.4.p216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, Benson L, Zautra AJ, & Ram N (2018). Emodiversity and Biomarkers of Inflammation. Emotion, 18, 3–14. doi: 10.1037/emo0000343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, Bergeman CS, & Bisconti TL (2005). Unique effects of daily perceived control on anxiety symptomatology during conjugal bereavement. Personality and Individual Differences, 38, 1057–1067. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2004.07.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, & Podsakoff NP (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]