Abstract

Background/Objectives

Older adults who undergo kidney transplantation (KT) are living longer with a functioning graft and are at risk for age-related adverse events including fractures. Understanding recipient, transplant, and donor factors and outcomes associated with fractures may help identify older KT recipients at increased risk. We determined incidence of hip, vertebral, and extremity fractures; assessed factors associated with incident fractures; and estimated associations between fractures and subsequent death-censored graft loss (DCGL) and mortality.

Design

This was a prospective cohort study of patients who underwent their first KT between 1/1/1999 and 12/31/2014.

Setting

We linked data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) to Medicare claims through the United States Renal Data System (USRDS).

Participants

The analytic population included 47,815 KT recipients aged ≥55 years.

Measurements

We assessed cumulative incidence of and factors associated with post-KT fractures (hip, vertebral, or extremity) using competing risks models. We estimated risk of DCGL and mortality after fracture using adjusted Cox proportional hazards models.

Results

The 5-year incidence of post-KT hip, vertebral, and extremity fracture for those aged 65-69 was 2.2%, 1.0%, and 1.7%, respectively. Increasing age was associated with higher hip (adjusted Hazard Ratio (aHR)=1.37 per 5-year increase, 95%CI:1.30-1.45) and vertebral (aHR=1.31, 95%CI:1.20-1.42) but not extremity (aHR=0.97, 95%CI:0.91-1.04) fracture risk. DCGL risk was higher after hip (aHR=1.34, 95%CI:1.12-1.60) and extremity (aHR=1.30, 95%CI:1.08-1.57) fracture. Mortality risk was higher after hip (aHR=2.31, 95%CI:2.11-2.52), vertebral (aHR=2.80, 95%CI:2.44-3.21), and extremity (aHR=1.85, 95%CI:1.64-2.10) fracture.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that older KT recipients are at higher risk for hip and vertebral fracture but not extremity fracture; and those with hip, vertebral, or extremity fracture are more likely to suffer subsequent graft loss or mortality. These findings underscore that different fracture types may have different underlying etiologies and risks and should be approached accordingly.

Keywords: fractures, kidney transplant, graft loss, mortality, older adults

INTRODUCTION

Access to kidney transplantation (KT) has improved among older adults with end-stage renal disease (ESRD), with the percent of KT recipients aged ≥65 increasing from 3.4% to 18.4% since 1990.1 Owing to improvements in transplantation during this same time frame, reduced risk of graft loss and increased survival have been observed among older KT recipients compared to those remaining on hemodialysis.1–3 With improved survival, however, older KT-recipients are at risk for age-related adverse events such as fractures.4,5

Increased fracture risk is well-established among adults of all ages with ESRD. Patients undergoing dialysis have a 4-fold risk of hip fracture compared to community-dwelling adults of the same age and sex.6 Like patients undergoing dialysis, KT recipients of all ages are at increased risk for fracture post-KT, though risk estimates have varied substantially.6–18 Similar to community-dwelling older adults, decreased bone mineral density plays an important role in the pathway to fractures among patients with renal disease.7,19 Specifically, decreased renal function in conjunction with post-KT glucocorticoid use impacts long-term bone health.19–23 Furthermore, among recipients of all ages, fractures are associated with hospitalization and mortality.7 These relationships between fracture and sequelae, nevertheless, were established in an era before KT was widely offered to older adults.7,12,16 Because older adults are more vulnerable to fractures, the incidence, risk factors, and sequelae likely differ from what has been reported among KT recipients of all ages. Therefore, we sought to determine the incidence of hip, vertebral, and extremity fracture; assess factors associated with incident fracture of each type; and estimate the associations between fractures and subsequent death-censored graft loss (DCGL) and mortality among KT recipients aged ≥55 years.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

This was a cohort study of 47,815 adult Medicare beneficiaries aged ≥55 years who underwent their first KT between 1/1/1999-12/31/2014. This study used data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) and the United States Renal Data System (USRDS). The SRTR data system is a national registry that includes data on all donors, wait-listed candidates, and transplant recipients in the United States, submitted by members of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services provides oversight to the activities of the OPTN and SRTR contractors. The USRDS data system is a national registry of all ESRD patients in the United States who are observed until death, which is ascertained via linkage to the Social Security Master Death File. USRDS also links data to Medicare claims, data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), and waitlist data.

Recipient, Transplant, and Donor Factors

Potential predictors were selected using prior studies investigating factors associated with fractures in older adults and KT recipients of all ages.8–18,24 They included recipient factors at KT (age, sex, race, BMI, hypertension, diabetes, ESRD cause, years on dialysis, peak panel reactive antibody, and pre-emptive KT); transplant factors (year of transplant, number of human leukocyte antigen mismatches, and cold ischemia time); and donor factors (age, sex, race, and donor type [living, deceased, deceased with cardiac death, or expanded criteria]) as suboptimal organs may lead to delayed graft function or long-term graft dysfunction, which in turn results in decreased bone density and increased fracture risk.12 Induction (short-term high dose immunosuppressive agents and antibodies directed against T-cell antigens) and maintenance (three immunosuppressive agents differing in mechanism of action) therapies are initiated at time of KT to prevent acute rejection and allograft loss.19 While some of these agents (glucocorticoids and calcineurin inhibitors) are associated with increased fracture risk owing to rapid bone loss or turnover, others (mTOR) are considered bone sparing.25,26 Therefore, induction agents (anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG), IL2 receptor antagonists, alemtuzumab, OKT3, and rituximab) and maintenance immunosuppression therapies (steroids, tacrolimus, cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil, mTOR, and azathioprine) were also considered as predictors.

Fracture Assessment

Incident fracture was defined as the first claim of fracture post-KT using the following International Classification of Diseases-9th Modification Diagnosis Codes (ICD-9): Hip fracture (820.xx), vertebral fracture (805.xx-806.xx), and extremity fracture (hand fracture [814.xx-817.xx], closed/open fracture of lower end of radius and ulna [813.4-813.5], and foot/ankle fracture [824.xx-826.xx]).

Prediction Model for Hip, Vertebral, or Extremity Fracture

Cumulative incidence of hip, vertebral, or extremity fracture by age at transplantation was estimated using the Fine and Gray subdistributional hazards model, accounting for competing risks of death and DCGL.27 Associations between recipient, transplant, and donor factors and post-KT fracture by fracture type (hip, vertebral, or extremity) were estimated using Cox proportional hazards models. Proportional hazards assumptions were assessed by visual inspection of complimentary log-log plots. KT recipients entered the study at date of KT and were censored at date of death, graft loss, Medicare coverage cessation, or end of SRTR follow-up (12/3½014). Covariates for inclusion in the model for each fracture type were based on a priori rationale and optimal parsimony by minimizing the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC).

Death-Censored Graft Loss and Mortality after Fracture

DCGL was defined as irreversible graft failure signified by return to long-term dialysis (ascertained from CMS), listing for KT (ascertained from SRTR), or re-transplantation (ascertained from SRTR).5 The hazard ratio (HR) for DCGL or mortality associated with each incident post-KT fracture type was estimated using Cox proportional hazard models with fracture treated as a time-varying covariate. Other covariates were the same as those included in the models for predictors of each respective fracture type. Effect modification of the association between fracture and DCGL or mortality by age, sex, race, BMI, and diabetes was assessed.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using STATA 14.2/SE (StataCorp. 2015. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP). The Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board approved this study and use of SRTR and USRDS data; this study was deemed exempt from consent.

RESULTS

Study Population

Of 47,815 older KT recipients followed for a median of 3.0 years (IQR: 1.0-5.4), the mean age at KT was 64 years (Standard Deviation (SD): 6), 37.4% were female, 28.0% were black, 37.9% had diabetes as cause of ESRD, 47.7% had diabetes, and 89.1% had hypertension (Table 1). The median time on dialysis was 3.3 years (Interquartile Range (IQR): 1.7-5.0), 3.4% received a pre-emptive transplant, and 18.6% received an organ from a live donor. During follow-up, some experienced multiple fracture types: 59 had incident hip and vertebral fracture, 39 had incident vertebral and extremity fracture, 81 had incident hip and extremity fracture, and 10 had incident hip, vertebral, and extremity fracture.

Table 1.

Kidney transplant (KT) recipient, transplant, and donor factors for recipients aged ≥55 years at time of KT by incident post-KT fracture type

| Incident Fracture Type | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None (n=45,825) |

Anya (n=1,990) |

Hipb (n=1,011) |

Vertebralb (n=403) |

Extremityb (n=745) |

|

| Recipient Factorsc | |||||

| Aged (years) | 63.6 (5.9) | 65.4 (6.2) | 66.5 (6.4) | 65.0 (6.1) | 63.7 (5.5) |

| Female | 36.9 | 48.2 | 43.3 | 49.1 | 57.9 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| Black | 28.6 | 14.7 | 11.3 | 12.2 | 19.9 |

| White | 49.8 | 66.4 | 71.6 | 66.5 | 60.0 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 14.1 | 12.1 | 11.0 | 13.2 | 13.4 |

| Other/multi-racial | 7.6 | 6.8 | 6.1 | 8.2 | 6.7 |

| Body mass indexd (kg/m2) | 28.2 (4.9) | 27.5 (4.9) | 26.7 (4.5) | 27.3 (5.0) | 28.7 (5.2) |

| Body weightd (kg) | 81.9 (17.2) | 79.0 (17.0) | 76.9 (15.6) | 78.3 (17.6) | 81.7 (18.0) |

| Hypertension | 89.1 | 87.3 | 86.1 | 88.1 | 87.7 |

| Diabetes | 47.3 | 56.1 | 54.5 | 47.6 | 62.0 |

| ESRD cause | |||||

| Glomerular | 13.0 | 10.5 | 10.9 | 13.2 | 7.4 |

| Diabetes | 37.5 | 47.0 | 45.4 | 41.4 | 51.4 |

| Hypertension | 24.0 | 18.6 | 18.8 | 20.4 | 17.2 |

| Other | 25.5 | 24.3 | 24.8 | 25.1 | 24.0 |

| Years on dialysise | 3.3 (1.7, 5.0) | 2.8 (1.4, 4.4) | 2.7 (1.3, 4.3) | 2.7 (1.4, 4.3) | 3.0 (1.8, 5.2) |

| Peak panel reactive antibodye | 0 (0, 15) | 1 (1, 15) | 0 (0, 12) | 0 (0, 12) | 3 (0, 22) |

| Transplant Factorsc | |||||

| Year of transplantation | |||||

| 1999-2003 | 22.3 | 38.6 | 39.9 | 42.2 | 36.1 |

| 2004-2007 | 25.8 | 32.1 | 32.7 | 30.8 | 32.8 |

| 2008-2011 | 28.8 | 22.6 | 21.7 | 19.4 | 24.2 |

| 2011-2014 | 23.2 | 6.7 | 5.7 | 7.7 | 7.0 |

| Number of HLA mismatches | |||||

| 0 | 7.8 | 11.0 | 12.6 | 10.9 | 11.1 |

| 1-2 | 9.5 | 13.6 | 13.4 | 13.9 | 13.8 |

| 3-4 | 40.9 | 40.7 | 41.2 | 42.9 | 39.3 |

| 5-6 | 41.8 | 33.8 | 32.9 | 32.3 | 35.7 |

| Pre-emptive KT | 3.4 | 3.1 | 3.6 | 2.7 | 2.7 |

| Cold ischemia timee- (hours) | 15.8 (9.5, 21) | 15.8 (9.3, 20.5) | 15.8 (9, 20) | 15.8 (9, 21) | 15.8 (9.5, 21) |

| Donor Factorsc | |||||

| Aged (years) | 42.7 (16.1) | 42.4 (16.1) | 42.6 (16.4) | 43.2 (15.6) | 41.8 (15.9) |

| Female | 45.9 | 46.1 | 47.7 | 47.9 | 42.8 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| Black | 13.7 | 8.9 | 7.5 | 8.2 | 11.0 |

| White | 69.8 | 75.5 | 77.4 | 73.7 | 74.4 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 12.9 | 12.2 | 11.3 | 13.9 | 12.4 |

| Other/multi-racial | 3.6 | 3.4 | 3.9 | 4.2 | 2.3 |

| Donor type | |||||

| Live | 18.5 | 21.1 | 20.7 | 25.8 | 20.0 |

| Standard deceased | 50.8 | 49.4 | 48.3 | 47.9 | 50.2 |

| Donation after cardiac death | 9.1 | 7.6 | 7.0 | 5.5 | 9.4 |

| Expanded criteria | 21.6 | 21.1 | 24.0 | 20.8 | 20.4 |

Abbreviations: ESRD = End-stage renal disease

Fracture type was determined using diagnosis based on ICD-9 codes. Recipient, transplant, and donor factors were at time of KT.

Any includes any hip, vertebral, or extremity fracture

Among KT recipients who experienced a fracture, 59 had incident hip and vertebral fracture, 39 had incident vertebral and extremity fracture, 81 had incident hip and extremity fracture, and 10 had incident hip, vertebral, and extremity fracture.

All values are given as percentages unless otherwise indicated

Mean (Standard Deviation)

Median (Interquartile Range)

Cumulative Incidence and Predictors of Hip Fracture

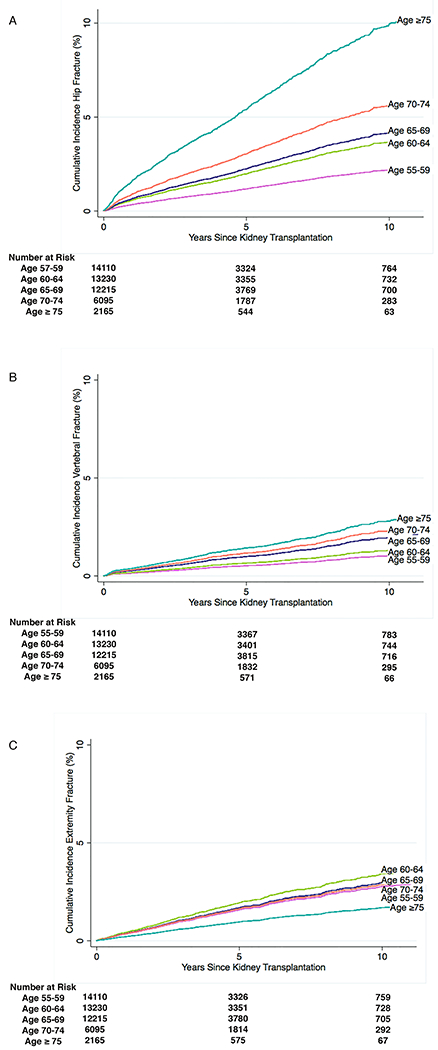

Older recipients with incident hip fracture post-KT were more likely to have higher mean age (66.5 versus 63.6 years, p<0.001), be female (43.3% versus 37.3%, p<0.001), be non-black (88.7% versus 71.6%, p<0.001), have BMI<30 kg/m2 (79.6% versus 66.5%, p<0.001), and have diabetes (54.5% versus 47.6%, p<0.001) (Table 1). After accounting for competing risks, the cumulative incidence at 1- and 5-years for those aged 55-59 years at KT was 0.3% and 1.2%, respectively; for those aged ≥75 years, it was 1.6% and 5.4%, respectively (Figure 1A, Table 2).

Figure 1. Cumulative Incidence of post-kidney transplantation (KT) fractures among KT recipients aged ≥55 years by recipient age at KT.

Estimated cumulative incidence (%) of hip (panel A), vertebral (panel B), or extremity (panel C) fracture by age at KT among older (aged ≥55 years) KT recipients. Curves were estimated using survival analysis accounting for competing risks of death and death-censored graft loss using the Fine and Gray approach. Entry (time zero) is the date of kidney transplantation. Participants were censored at time of fracture, death, death-censored graft loss, Medicare coverage cessation, or end of study. Fracture type was determined using diagnosis based on ICD-9 codes.

Table 2:

Cumulative incidence of post-kidney transplant (KT) fracture among KT recipients aged ≥55 years by fracture type and age at KT

| Cumulative Incidence of Fractures (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-year | 3-year | 5-year | 10-year | |

| Hip Fracture | ||||

| Age at KT (years) | ||||

| 55-59 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 2.2 |

| 60-64 | 0.6 | 1.3 | 2.0 | 3.7 |

| 65-69 | 0.7 | 1.5 | 2.2 | 4.2 |

| 70-74 | 0.9 | 2.0 | 3.1 | 5.7 |

| ≥75 | 1.6 | 3.6 | 5.4 | 10.0 |

| Vertebral Fracture | ||||

| Age at KT (years) | ||||

| 55-59 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 1.0 |

| 60-64 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 1.3 |

| 65-69 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 2.0 |

| 70-74 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 2.3 |

| ≥75 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 1.4 | 2.8 |

| Extremity Fracture | ||||

| Age at KT (years) | ||||

| 55-59 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 2.7 |

| 60-64 | 0.4 | 1.2 | 1.9 | 3.4 |

| 65-69 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 2.9 |

| 70-74 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 2.9 |

| ≥75 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 1.7 |

Estimated cumulative incidence (%) of fracture (hip, vertebral, or extremity) by age at KT among older (aged ≥55 years) KT recipients. Cumulative incidence was estimated using survival analysis accounting for competing risks of death and death-censored graft loss. Entry (time zero) is the date of KT. Participants were censored at time of death, death-censored graft loss, Medicare coverage cessation, or end of study. Fracture type was determined using diagnosis based on ICD-9 codes.

Each 5-year increase in age after age 55 years at time of KT was independently associated with a 1.37-fold (95% CI: 1.30-1.45, p<0.001) higher risk of hip fracture (Table 3). Females (adjusted Hazard Ratio [aHR]=1.44, 95% CI: 1.27-1.64, p<0.001), white recipients (aHR=3.11, 95% CI: 2.54-3.82, p<0.001), and those with diabetes (aHR=1.64, 95% CI: 1.31-2.06, p<0.001) were also at greater risk. Compared to recipients with BMI ≥30 kg/m2, those with a BMI of 25–29.9 kg/m2 had higher risk (aHR=1.63, 95% CI: 1.38-1.94, p<0.001). Each one-year increase in calendar year was associated with lower risk of hip fracture (aHR=0.94, 95% CI: 0.93-0.96, p<0.001).

Table 3.

Associations between kidney transplant (KT) recipient, transplant, and donor factors and incident post-KT fractures among KT recipients aged ≥55 years

| Hip HR (95% CI) |

Vertebral HR (95% CI) |

Extremity HR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Recipient Factors | |||

| Age (per 5 years) | 1.37 (1.30, 1.45) | 1.31 (1.20, 1.42) | 0.97 (0.91, 1.04) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Female | 1.44 (1.27, 1.64) | 1.72 (1.41, 2.11) | 2.44 (2.10, 2.82) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Black | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| White | 3.11 (2.54, 3.82) | 2.49 (1.80, 3.43) | 1.83 (1.50, 2.22) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 1.74 (1.34, 2.27) | 2.01 (1.35, 2.99) | 1.34 (1.03, 1.73) |

| Other/multi-racial | 1.64 (1.20, 2.25) | 2.23 (1.42, 3.50) | 1.30 (0.94, 1.81) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | |||

| ≥30 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| 25-29.9 | 1.63 (1.38, 1.94) | 1.13 (0.88, 1.44) | 0.91 (0.77, 1.08) |

| 18.5-24.9 | 2.24 (1.87, 2.67) | 1.15 (0.88, 1.51) | 0.80 (0.65, 0.97) |

| <18.5 | 2.74 (1.65, 4.52) | 2.73 (1.48, 5.04) | 0.86 (0.43, 1.73) |

| Diabetes | 1.64 (1.31, 2.06) | 0.88 (0.58, 1.34) | 1.76 (1.37, 2.27) |

| ESRD cause (%) | |||

| Glomerular | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Diabetes | 1.45 (1.09, 1.93) | 1.71 (1.07, 2.73) | 1.77 (1.25, 2.49) |

| Hypertension | 1.18 (0.93, 1.49) | 1.13 (0.79, 1.60) | 1.51 (1.10, 2.08) |

| Others | 1.04 (0.83, 1.30) | 0.90 (0.65, 1.26) | 1.51 (1.12, 2.04) |

| Years on dialysis (per 3 years) | 1.04 (0.97, 1.11) | 1.02 (0.92, 1.14) | 1.01 (0.93, 1.09) |

| Induction immunosuppression | |||

| No biological agent | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| ATG | 1.08 (0.91, 1.28) | 1.21 (0.92, 1.59) | 0.97 (0.80, 1.17) |

| IL2 receptor antagonist | 1.08 (0.92, 1.26) | 1.30 (1.01, 1.68) | 0.93 (0.77, 1.13) |

| Alemtuzumab | 0.82 (0.59, 1.13) | 1.44 (0.90, 2.30) | 1.02 (0.73, 1.43) |

| Other/Multiple agents | 0.93 (0.66, 1.30) | 1.16 (0.68, 1.97) | 0.69 (0.46, 1.06) |

| Maintenance immunosuppression | |||

| Steroids | |||

| No | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Yes | 1.13 (0.96, 1.34) | 1.98 (1.47, 2.66) | 1.43 (1.17, 1.74) |

| Calcineurin Inhibitors | |||

| Tacrolimus | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Cyclosporinb | 1.01 (0.86, 1.19) | 1.35 (1.07, 1.72) | 1.20 (1.00, 1.45) |

| None | 0.83 (0.62, 1.11) | 1.02 (0.66, 1.59) | 0.84 (0.60, 1.17) |

| Antimetabolites | |||

| MMF | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| mTOR | 1.18 (0.90, 1.54) | 1.52 (1.03, 2.24) | 0.75 (0.51, 1.10) |

| Azathioprine | 1.10 (0.70, 1.72) | 0.94 (0.45, 1.99) | 0.91 (0.50, 1.64) |

| Multiple antimetabolites | 1.44 (1.03, 2.02) | 1.09 (0.61, 1.95) | 1.51 (1.01, 2.25) |

| None | 0.81 (0.60, 1.09) | 1.07 (0.70, 1.64) | 0.86 (0.62, 1.19) |

| Transplant Factors | |||

| Year of transplant (per 1 year) | 0.94 (0.93, 0.96) | 0.98 (0.95, 1.01) | 0.98 (0.95, 1.00) |

| Donor Factors | |||

| Age (per 5 years) | 0.98 (0.96, 1.00) | 1.02 (0.98, 1.06) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.02) |

| Donor type | |||

| Living | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Standard deceased | 1.00 (0.84, 1.18) | 0.81 (0.63, 1.05) | 1.00 (0.82, 1.22) |

| Donation after cardiac death | 1.20 (0.91, 1.58) | 0.71 (0.45, 1.14) | 1.45 (1.08, 1.94) |

| Expanded criteria | 1.19 (0.97, 1.47) | 0.72 (0.52, 1.00) | 1.05 (0.81, 1.36) |

Abbreviations: HR = Hazard Ratio, CI = Confidence Interval, ESRD = End-stage renal disease, HLA = human leukocyte antigen, ATG = anti-thymocyte globulin, MMF = Mycophenolate Mofetil, mTOR = mammalian target of rapamycin.

All HRs for each fracture type are from a single adjusted Cox proportional hazards model accounting for competing risks of death and death-censored graft loss. Covariates included are based on a parsimonious model derived using Akaike Information Criteria and a priori rationale. Fracture types were determined using diagnosis based on ICD-9 codes. Recipient, transplant, and donor factors were at time of kidney transplantation.

Of those using cyclosporine for maintenance therapy, 2% were also using tacrolimus.

Cumulative Incidence and Predictors of Vertebral Fracture

Older recipients with incident vertebral fracture post-KT were more likely to have higher mean age (65.0 versus 63.6 years, p<0.001), be female (49.1% versus 37.3%, p<0.001), be non-black (87.8% vs. 71.9%, p<0.001), and have BMI<30 kg/m2 (72.7% versus 66.7%, p=0.01) (Table 1). After accounting for competing risks, the cumulative incidence at 1- and 5-years for those aged 55-59 years at KT was 0.1% and 0.5% respectively; for those aged ≥75 years, it was 0.4% and 2.8%, respectively (Figure 1B, Table 2).

Each 5-year increase in age after age 55 years at time of KT was independently associated with a 1.31-fold (95% CI: 1.20-1.42, p<0.001) higher risk of a verterbral fracture (Table 3). Females (aHR=1.72, 95% CI: 1.41-2.11, p<0.001) and white recipients (aHR=2.49, 95% CI: 1.80-3.43, p<0.001) were also at greater risk. IL-2 receptor antagonists (aHR 1.30, 95% CI: 1.02-1.68, p=0.04) and maintenance immunosuppression with steroids (aHR=1.98, 95% CI: 1.47-2.66, p<0.001), cyclosporine (aHR=1.35, 95% CI: 1.07-1.72, p=0.01), and mTOR (aHR=1.52, 95% CI: 1.03-2.24, p=0.04) were associated with higher risk of vertebral fracture.

Cumulative Incidence and Predictors of Extremity Fracture

Older recipients with incident extremity fracture post-KT were more likely to be female (57.9% versus 37.1%, p<0.001), be non-black (80.1% vs. 71.9%, p<0.001), have BMI≥30 kg/m2 (38.4% versus 33.2%, p<0.001), and have diabetes (62.0% versus 47.5%, p<0.001) (Table 1). After accounting for competing risks, the cumulative incidence at 1- and 5-years for those aged 55–59 years at KT was 0.3% and 1.6% respectively; for those aged≥75, it was 0.4% and 1.7%, respectively (Figure 1C, Table 2).

Females (aHR=2.44, 95% CI: 2.10-2.82, p<0.001), white recipients (aHR=1.83, 95% CI: 1.50-2.22, p<0.001), and those with diabetes (aHR=1.76, 95% CI: 1.37-2.27) were more likely to experience an extremity fracture (Table 3). Each one-year increase in calendar year was associated with lower risk of extremity fracture (aHR=0.98, 95% CI: 0.95-1.00, p=0.03). Maintenance immunosuppression with steroids (aHR=1.43, 95% CI: 1.17-1.74, p<0.001) and multiple antimetabolites (aHR=1.51, 95% CI: 1.01-2.25, p=0.04) were associated with higher risk of extremity fracture. Kidneys from a deceased donor with cardiac death was associated with 1.45-fold (95% CI: 1.08-1.94, p=0.01) higher risk.

Hip Fracture and Death-Censored Graft Loss or Mortality

Incident hip fracture was independently associated with a 1.34-fold (95% CI: 1.12-1.60, p=0.001) higher risk of DCGL and a 2.31-fold (95% CI: 2.11-2.52, p<0.001) higher risk of mortality (Table 4).

Table 4.

Associations between incident fractures and adverse post-kidney transplant (KT) outcomes (death-censored graft loss and mortality) among KT recipients aged ≥55 years, overall and stratified by age, sex, race, body mass index, and diabetes status

| Hip HR (95% CI) |

Vertebral HR (95% CI) |

Extremity HR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Death-censored Graft Loss | |||

| Overall risk | 1.34 (1.12, 1.60) | 1.32 (0.98, 1.78) | 1.30 (1.08, 1.57) |

| Age (years) | |||

| 55-65 | 1.38 (1.08, 1.77) | 1.64 (1.10, 2.45) | 1.46 (1.17, 1.83) |

| ≥65 | 1.26 (0.98, 1.62) | 1.06 (0.68, 1.64) | 1.05 (0.75, 1.47) |

| p for interaction | 0.62 | 0.15 | 0.11 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1.23 (0.97, 1.57) | 1.35 (0.90, 2.03) | 1.37 (1.04, 1.80) |

| Female | 1.48 (1.15, 1.91) | 1.30 (0.84, 1.99) | 1.25 (0.96, 1.61) |

| p for interaction | 0.30 | 0.90 | 0.62 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Black | 1.21 (0.78, 1.89) | 1.22 (0.55, 2.73) | 0.92 (0.62, 1.38) |

| Non-black | 1.38 (1.14, 1.67) | 1.34 (0.97, 1.85) | 1.47 (1.19, 1.82) |

| p for interaction | 0.61 | 0.83 | 0.04 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | |||

| <30 | 1.57 (1.13, 2.19) | 1.68 (1.03, 2.74) | 1.15 (0.85, 1.56) |

| ≥30 | 1.26 (1.02, 1.55) | 1.18 (0.81, 1.71) | 1.42 (1.11, 1.80) |

| p for interaction | 0.26 | 0.27 | 0.29 |

| Diabetes | |||

| No | 1.26 (0.96, 1.65) | 1.55 (1.04, 2.29) | 1.52 (1.11, 2.10) |

| Yes | 1.41 (1.12, 1.77) | 1.11 (0.71, 1.75) | 1.21 (0.96, 1.53) |

| p for interaction | 0.54 | 0.28 | 0.25 |

| Mortality | |||

| Overall risk | 2.31 (2.11, 2.52) | 2.80 (2.44, 3.21) | 1.85 (1.64, 2.10) |

| Age (years) | |||

| 55-65 | 2.18 (1.89, 2.51) | 2.38 (1.86, 3.03) | 1.75 (1.47, 2.07) |

| ≥65 | 2.53 (2.27, 2.83) | 3.17 (2.69, 3.74) | 1.91 (1.61, 2.28) |

| p for interaction | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.46 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 2.40 (2.14, 2.69) | 2.42 (1.99, 2.94) | 1.64 (1.37, 1.98) |

| Female | 2.18 (1.89, 2.50) | 3.30 (2.72, 3.99) | 2.05 (1.74, 2.41) |

| p for interaction | 0.28 | 0.03 | 0.08 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Black | 2.59 (2.00, 3.34) | 2.79 (1.88, 4.13) | 1.82 (1.39, 2.39) |

| Non-black | 2.34 (2.13, 2.57) | 2.80 (2.42, 3.23) | 1.86 (1.62, 2.13) |

| p for interaction | 0.46 | 0.98 | 0.90 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | |||

| <30 | 2.23 (1.83, 2.72) | 2.40 (1.82, 3.15) | 2.01 (1.65, 2.46) |

| ≥30 | 2.34 (2.12, 2.58) | 2.97 (2.54, 3.48) | 1.77 (1.52, 2.07) |

| p for interaction | 0.69 | 0.18 | 0.32 |

| Diabetes | |||

| No | 2.52 (2.21, 2.88) | 3.53 (2.93, 4.26) | 1.94 (1.59, 2.37) |

| Yes | 2.15 (1.91, 2.42) | 2.26 (1.86, 2.76) | 1.80 (1.55, 2.11) |

| p for interaction | 0.08 | 0.001 | 0.56 |

Abbreviations: HR = Hazard Ratio, CI = Confidence Interval

Each HR for the risk of death-censored graft loss as well as the risk of mortality for each fracture type is derived from a separate Cox model adjusted for the risk factors identified for each fracture type in Table 3. Fracture types were determined using diagnosis based on ICD-9 codes. Recipient, donor, and transplant factors were at time of KT.

Vertebral Fracture and Death-Censored Graft Loss or Mortality

Incident vertebral fracture was independently associated with a 2.80-fold (95% CI: 2.44-3.21, p<0.001) higher risk of mortality but showed no association with DCGL (Table 4). The association with mortality differed by sex (p for interaction=0.03) and diabetes status (p for interaction=0.001). For example, among females, vertebral fracture was associated with 3.30-fold (95% CI: 2.72-3.99) greater risk of mortality, while among males, it was associated with a 2.42-fold (95% CI: 1.99-2.94) greater risk.

Extremity Fracture and Death-Censored Graft Loss or Mortality

Incident extremity fracture was independently associated with a 1.30-fold (95% CI: 1.08-1.57, p=0.006) higher risk of DCGL and a 1.85-fold (95% CI: 1.64-2.10, p<0.001) higher risk of mortality (Table 4). The association between extremity fracture and DCGL differed by race (p for interaction=0.04). Among non-black KT recipients, extremity fracture was associated with a 1.47-fold (95% CI: 1.19-1.82) higher risk of DCGL, while among black recipients, it was not associated with DCGL.

DISCUSSION

In this national study of 47,815 older KT recipients, the 5-year incidence of post-KT hip fracture ranged from 1.2% for those aged 55-59 to 5.4% for those aged ≥75 years. The 5-year incidence of vertebral fracture slightly increased across age groups with an incidence of 0.5% for those aged 55-59 and 1.4% for those aged ≥75 years. The 5-year incidence of extremity fracture, however, was 1.6% for those aged 55-59 as well as for those aged 70-74 years. Although some factors, such as being female and white race, consistently were associated with an increased risk for hip, vertebral, or extremity fracture, other factors such as age, BMI, year of transplant, and donor type were not. Notably hip and extremity fracture among older recipients were associated with increased risk of DCGL and mortality. Those who experienced hip fracture were subsequently at 1.34-fold higher risk of graft loss and 2.31-fold higher risk of mortality with similar risks observed for extremity fracture. Likewise, those with vertebral fracture were at 2.80-fold higher risk of mortality.

In prior studies, wide-variability in fracture rates among KT recipients of all ages has been observed8-18 and likely is due to differences in study populations, fracture types, and statistical approaches.28,29 These studies used data prior to 2000 when KT in older adults was less common; therefore, inferences specific to older recipients have been limited. We built upon these prior studies by restricting our population to older recipients and modeled fracture types separately. Our result of a 10-year hip fracture incidence ranging from 2.2% for ages 55-59 years to 10.0% for ages ≥75 years supports that older KT recipients are at higher risk for fracture as defined in clinical guidelines for patients of all ages as a 10-year hip fracture risk ≥3%.30,31 For perspective, the lifetime risk of a hip fracture among community-dwelling adults is estimated at 6% and 17% after age 50 years for white males and females, respectively.32,33 Furthermore, we show that while the cumulative incidence of hip and vertebral fracture is higher in older age groups, the cumulative incidence of extremity fracture does not vary substantially by age group. These findings underscore that different fracture types may have different underlying etiology and risks, and should be approached accordingly.

Similar to studies of KT recipients of all ages, we found that among older KT recipients, females,8,9,12,14,15,17,24 those of white race,8,12,29 and those with diabetes12,16 were at higher risk for fracture. While higher BMI has been reported to reduce fracture risk in KT recipients of all ages,17 we found this was only true for hip fracture. Finally, we found that longer time on dialysis prior to KT was not associated with hip, vertebral, and extremity fracture. This result is consistent with recent findings in which longer time on dialysis was not associated with major fractures (hip, vertebral, proximal humerus, forearm) but inconsistent with an increased risk of non-major (lower leg, femoral shaft, rib/sternum, pelvis) fractures among KT recipients of all ages.24

As in our study of older KT recipients, declining rates of hip fracture over calendar year among KT recipients of all ages in the US has been reported previously.13 This declining rate is thought to result in part from decreased glucocorticoid use in recent years—a hypothesis supported by KT recipients with dual induction including methylprednisolone and antibody-based agents having 14% greater risk of fracture compared to no induction12 and KT recipients of all ages discharged with corticosteroids having higher fracture risk compared to those discharged without corticosteroids.34 In our study, although we found no association between steroid-based maintenance immunosuppression and hip fracture, steroid use was associated with extremity and vertebral fractures.

With respect to donor factors, although KT recipients who received a deceased donor organ have been reported to have 30% increased risk of fracture,12 we found this association to be more nuanced. While extremity fracture was associated with receiving an organ from a deceased donor with cardiac death, hip and vertebral fracture were not associated with donor type. In contrast to other studies showing greater fracture risk with older donor age,24 we found no association.

Similar to studies of KT recipients of all ages7,13,29 and community-dwelling older adults,35-42 we found that fractures were highly predictive of subsequent mortality. Within the first 3 months post-hip fracture, the risk of all-cause mortality among community-dwelling older adults has been estimated to increase 5-8-fold.43 The over 2-fold higher risk of mortality following hip fracture that we observed among older KT recipients is within previously reported ranges among KT recipients of all ages;7,29 thus, although older adults are at increased risk of hip fracture, once hip fracture occurs the risk of death may be similar for all ages. We add to these previous studies by documenting a higher risk of mortality following extremity and vertebral fracture as well. We also found that hip and extremity fractures are associated with DCGL, which previously has not been shown. This result is consistent with observations of worse graft function among patients with osteoporosis or osteopenia, and may reflect that good graft function is needed to maintain bone mineral metabolism.44

This study has several limitations. In order to identify incident fractures, our study was limited to KT recipients using Medicare, a criterion that could differentially affect those under age 65, and thus generalizability. However, use of Medicare coverage is often an inclusion criterion in studies of ESRD patients45,46 as all patients requiring dialysis are Medicare eligible. Because Medicare claims data was used to assess for fractures, however, fracture incidence may be underestimated as some fractures are not clinically present.47 Nevertheless, because the vast majority of hip fractures are managed in the hospital, the majority are captured using inpatient claims.48 Moreover, whether a fracture was fall-related was not ascertained. Additionally, this national registry does not capture bone mineral density or important geriatric metrics like frailty, which predisposes KT recipients to fracture.49 Strengths of this study include using a competing risks approach which prevents over-estimation of risk,28 as well as a large dataset from a mandatory national registry which enables greater generalizability.

In conclusion, older KT recipients are at risk for fracture post-KT. Recipient, transplant, and donor factors may be useful in predicting risk for different types of fractures among older KT recipients. Risk factors for fracture such as older age and BMI, however, are not consistent across all fracture types. Despite these differences in risk factors for fracture, older KT recipients who experience a fracture whether hip, vertebral, or extremity are at increased risk of subsequent DCGL or mortality. These results suggest that identifying fracture risks and minimizing fractures among older KT recipients may in turn improve KT outcomes. Furthermore, when fractures do occur, management for KT recipients should include assessment of graft function and immunosuppressive regimen.

ACKNOLWEDGEMENTS

Sponsor’s Role

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01DK120518 (Principal Investigator: M.A.M.-D), R01AG042504 (Principal Investigator: D.L.S.), and K24DK101828 (Principal Investigator: D.L.S.). M.A.M.-D. was supported by the National Institute on Aging (P30AG021334, K01AG043501, R01AG055781) and by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases R01DK120518.

The data reported here have been supplied by the Minneapolis Medical Research Foundation as the contractor for the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR). The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the author(s) and should in no way be seen as an official policy of or interpretation by the SRTR or the United States government.

Abbreviations

- aHR

adjusted hazard ratio

- AIC

Akaike Information Criteria

- ATG

anti-thymocyte globulin

- BMI

body mass index

- CI

confidence interval

- CMS

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

- DCGL

death-censored graft loss

- ESRD

end-stage renal disease

- HLA

human leukocyte antigen

- HR

hazard ratio

- ICD-9

International Classification of Diseases-9th Modification Diagnosis Codes

- IQR

interquartile range

- KT

kidney transplantation

- MMF

Mycophenolate Mofetil

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- OPTN

Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network

- SD

standard deviation

- SRTR

Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients

- USRDS

United States Renal Data System

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

D.L.S holds speaking honoraria from Sanofi, Novartis, and CSL Behring. The remaining authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.McAdams-DeMarco MA, James N, Salter ML, Walston J, Segev DL. Trends in kidney transplant outcomes in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014;62(12):2235–2242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knoll GA. Kidney transplantation in the older adult. Am J Kidney Dis 2013;61(5):790–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Molnar MZ, Streja E, Kovesdy CP, et al. Age and the associations of living donor and expanded criteria donor kidneys with kidney transplant outcomes. Am J Kidney Dis 2012;59(6):841–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haugen CE, Mountford A, Warsame F, et al. Incidence, Risk Factors, and Sequelae of Post-kidney Transplant Delirium. J Am Soc Nephrol 2018;29(6):1752–1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McAdams-DeMarco MA, Bae S, Chu N, et al. Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease among Older Kidney Transplant Recipients. J Am Soc Nephrol 2017;28(5):1575–1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alem AM, Sherrard DJ, Gillen DL, et al. Increased risk of hip fracture among patients with end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int 2000;58(1):396–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abbott KC, Oglesby RJ, Hypolite IO, et al. Hospitalizations for fractures after renal transplantation in the United States. Ann Epidemiol 2001;11(7):450–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ball AM, Gillen DL, Sherrard D, et al. Risk of hip fracture among dialysis and renal transplant recipients. JAMA 2002;288(23):3014–3018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naylor KL, Jamal SA, Zou G, et al. Fracture Incidence in Adult Kidney Transplant Recipients. Transplantation 2016;100(1):167–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naylor KL, Leslie WD, Hodsman AB, Rush DN, Garg AX. FRAX predicts fracture risk in kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation 2014;97(9):940–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naylor KL, Li AH, Lam NN, Hodsman AB, Jamal SA, Garg AX. Fracture risk in kidney transplant recipients: a systematic review. Transplantation 2013;95(12):1461–1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nikkel LE, Hollenbeak CS, Fox EJ, Uemura T, Ghahramani N. Risk of fractures after renal transplantation in the United States. Transplantation 2009;87(12):1846–1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nair SS, Lenihan CR, Montez-Rath ME, Lowenberg DW, Chertow GM, Winkelmayer WC. Temporal trends in the incidence, treatment and outcomes of hip fracture after first kidney transplantation in the United States. Am J Transplant 2014;14(4):943–951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Opelz G, Dohler B. Association of mismatches for HLA-DR with incidence of posttransplant hip fracture in kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation 2011;91(1):65–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramsey-Goldman R, Dunn JE, Dunlop DD, et al. Increased risk of fracture in patients receiving solid organ transplants. J Bone Miner Res 1999;14(3):456–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vautour LM, Melton LJ 3rd, Clarke BL, Achenbach SJ, Oberg AL, McCarthy JT. Long-term fracture risk following renal transplantation: a population-based study Osteoporos Int. 2004;15(2):160–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Shaughnessy EA, Dahl DC, Smith CL, Kasiske BL. Risk factors for fractures in kidney transplantation. Transplantation 2002;74(3):362–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arnold J, Mytton J, Evison F, et al. Fractures in Kidney Transplant Recipients: A Comparative Study Between England and New York State. Exp Clin Transplant 2017;16(4):410–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes CKDMB DWG. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of Chronic Kidney Disease-Mineral and Bone Disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney Int Suppl 2009(113):S1–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hodsman AB. Fragility fractures in dialysis and transplant patients. Is it osteoporosis, and how should it be treated? Perit Dial Int 2001;21 Suppl 3:S247–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Owda A, Elhwairis H, Narra S, Towery H, Osama S. Secondary hyperparathyroidism in chronic hemodialysis patients: prevalence and race. Ren Fail 2003;25(4):595–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taweesedt PT, Disthabanchong S. Mineral and bone disorder after kidney transplantation. World J Transplant 2015;5(4):231–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bouquegneau A, Salam S, Delanaye P, Eastell R, Khwaja A. Bone Disease after Kidney Transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2016;11(7):1282–1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naylor KL, Zou G, Leslie WD, et al. Risk factors for fracture in adult kidney transplant recipients. World J Transplant 2016;6(2):370–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Edwards BJ, Desai A, Tsai J, et al. Elevated incidence of fractures in solid-organ transplant recipients on glucocorticoid-sparing immunosuppressive regimens. J Osteoporos 2011;2011:591793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sprague SM, Josephson MA. Bone disease after kidney transplantation. Semin Nephrol 2004;24(1):82–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1999;94(446):496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berry SD, Ngo L, Samelson EJ, Kiel DP. Competing risk of death: an important consideration in studies of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58(4):783–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferro CJ, Arnold J, Bagnall D, Ray D, Sharif A. Fracture risk and mortality post-kidney transplantation. Clin Transplant 2015;29(11):1004–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grossman JM, Gordon R, Ranganath VK, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2010 recommendations for the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;62(11):1515–1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, et al. Clinicians Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. National Osteoporosis Int 2014;25:2359–2381.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cummings SR, Melton LJ. Epidemiology and outcomes of osteoporotic fractures. Lancet 2002;359(9319):1761–1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Melton LJ, 3rd. Who has osteoporosis? A conflict between clinical and public health perspectives. J Bone Miner Res 2000;15(12):2309–2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nikkel LE, Mohan S, Zhang A, et al. Reduced fracture risk with early corticosteroid withdrawal after kidney transplant. Am J Transplant 2012;12(3):649–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cooper Z, Mitchell SL, Lipsitz S, et al. Mortality and Readmission After Cervical Fracture from a Fall in Older Adults: Comparison with Hip Fracture Using National Medicare Data. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015;63(10):2036–2042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnell O, Kanis JA, Oden A, et al. Mortality after osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 2004;15(1):38–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keene GS, Parker MJ, Pryor GA. Mortality and morbidity after hip fractures. BMJ 1993;307(6914):1248–1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith T, Pelpola K, Ball M, Ong A, Myint PK. Pre-operative indicators for mortality following hip fracture surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing 2014;43(4):464–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Soderqvist A, Ekstrom W, Ponzer S, et al. Prediction of mortality in elderly patients with hip fractures: a two-year prospective study of 1,944 patients. Gerontology 2009;55(5):496–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Myeroff CM, Anderson JP, Sveom DS, Switzer JA. Predictors of Mortality in Elder Patients With Proximal Humeral Fracture. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil 2018;9:2151458517728155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Panula J, Pihlajamaki H, Mattila VM, et al. Mortality and cause of death in hip fracture patients aged 65 or older: a population-based study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2011;12:105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang MQ, Youssef T, Smerdely P. Incidence and outcomes of humeral fractures in the older person. Osteoporos Int 2018;29(7):1601–1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haentjens P, Magaziner J, Colon-Emeric CS, et al. Meta-analysis: excess mortality after hip fracture among older women and men. Ann Intern Med 2010;152(6):380–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marcen R, Caballero C, Uriol O, et al. Prevalence of osteoporosis, osteopenia, and vertebral fractures in long-term renal transplant recipients. Transplant Proc 2007;39(7):2256–2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grams ME, McAdams Demarco MA, Kucirka LM, Segev DL. Recipient age and time spent hospitalized in the year before and after kidney transplantation. Transplantation 2012;94(7):750–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McAdams-Demarco MA, Grams ME, King E, Desai NM, Segev DL. Sequelae of early hospital readmission after kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant 2014;14(2):397–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tamblyn R, Reid T, Mayo N, McLeod P, Churchill-Smith M. Using medical services claims to assess injuries in the elderly: sensitivity of diagnostic and procedure codes for injury ascertainment. J Clin Epidemiol 2000;53(2):183–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Berry SD, Zullo AR, McConeghy K, Lee Y, Daiello L, Kiel DP. Defining hip fracture with claims data: outpatient and provider claims matter. Osteoporos Int 2017;28(7):2233–2237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McAdams-DeMarco MA, Law A, King E, et al. Frailty and mortality in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 2015;15(1):149–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]